Abstract

Pulmonary pneumatocele is a thin-walled, air-filled cyst originating spontaneously within the lungs’ parenchyma, generally after infections or prolonged mechanical respiratory support. The diagnosis of pneumatocele is usually made using both chest X-ray (CXR) and computed tomography (CT) scan. Lung ultrasonography (LUS) is a promising technique used to investigate neonatal pulmonary diseases. We hereby present two cases of pneumatocele in newborns with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) in which CXR and LUS were used to evaluate pulmonary parenchyma. LUS showed a multilobed cyst with a thin hyperechoic wall and a hypoechoic central area. Repeated LUS demonstrated a progressive reduction of the cyst’s size. After a few weeks, the small lesions were no longer detectable by ultrasound, therefore CXR was used, for follow-up, in the following months, until complete resolution. No data are available in the literature regarding ultrasonographic follow-up of neonatal pneumatocele. A larger number of patients are required to confirm our results and increase the use of LUS in the neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) to reduce neonatal radiations exposure.

Introduction

Neonatal pneumatoceles are air filled cysts, spontaneously developing in the lung parenchyma or more often, secondary to pulmonary infections or mechanical ventilation lung injury [1]. The incidence of neonatal pneumatoceles ranges from 1.8% to 3.2% [1]. Pneumatoceles are often asymptomatic and self-limited; a more invasive approach should be reserved in complicated cases (superinfection or pneoumothorax). Most pneumatoceles disappear completely within few weeks or months, with no clinical sequelae [1]. A serial follow-up of these lesions is now recommended, using chest X-ray (CXR) and computed tomography (CT) scans, until resolution [1], [2], [3]. CT scan is a highly sensitive technique requiring high dose of radiations. Furthermore, it is difficult to be performed in mechanically ventilated patients. To date, there are no available studies reporting the use of ultrasonography in the diagnosis and follow-up of neonatal pneumatocele. We report two cases of ultrasonographic early follow-up in late preterm newborns with a single pneumatocele.

Methods

Lung ultrasonography (LUS) was performed at bedside at admission, simultaneously with the CXR and daily repeated until resolution, by the same operator. A high-resolution linear probe of 10 MHz was used for lungs examination. Longitudinal and transversal sections of the anterior, lateral and posterior wall were obtained.

Case 1

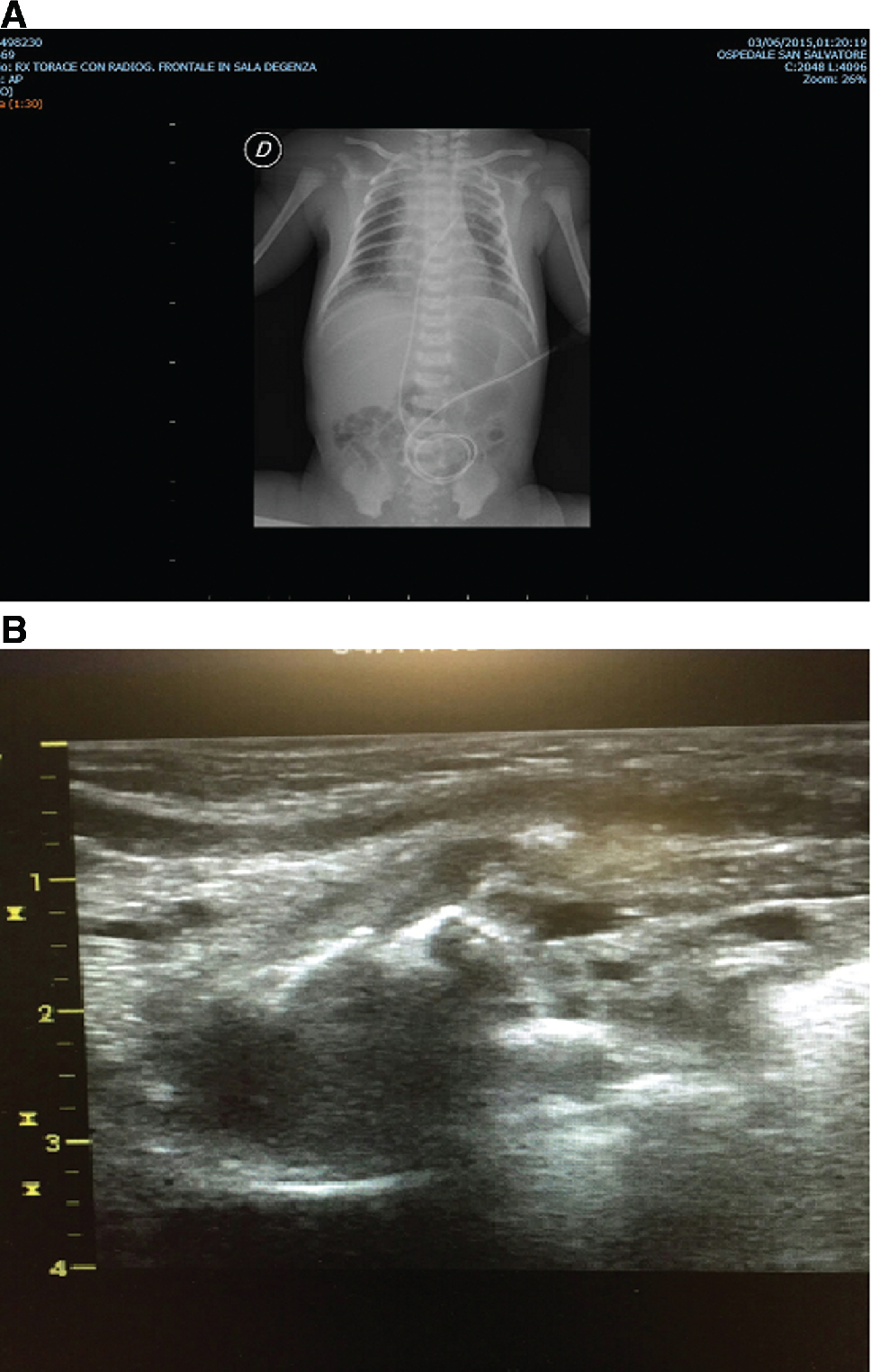

K.R., a male was born at 36 + 4 weeks of gestational age (GA), by an emergency cesarean section (CS) due to maternal pre-eclampsia (birth weight 3100 g, 50th percentile). He was admitted to our NICU soon after birth for respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), needing nCPAP support (CPAP 5.5 cm H2O, FiO2 0.25). CXR on admission revealed a pneumomediastinum and a radiolucent area, likely a pneumatocele in the middle-basal right lung (Figure 1A). The LUS revealed a characteristic picture of an intrapulmonary multilobed cyst, below the pleural line, with a thin hyperechoic external wall and a hypohecoic centrum (Figure 1B). Due to the clinical stability of the patient, sequential LUS were performed instead of CXR. nCPAP was discontinued on day 5 without the need for supplementary respiratory support. LUS revealed a progressive reduction in the cyst’s size, with a complete resolution on day 14. CXR performed at discharge, revealed a minimal residual lesion. The infant was discharged on day 16. Due to the clinical stability and no need of respiratory support, the CT scan was not performed. Monthly CXR was then performed, until complete resolution of the lesion at 3 months after birth. We performed a follow-up of the patients until 9 months after birth. The infant showed an adequate growth [weight at the last check: 8500 g (25–50th percentile), length (L 71 cm (25–50th percentile), chest circumference (CC) 45.5 cm (50th percentile)], good respiratory dynamics and no pulmonary infections.

(A) Chest X-ray at the beginning in case 1: radiolucent area susceptible for pneumatocele at medio-basal right lung. (B) LUS at the beginning in case 1: intrapulmonary multilobed cyst below the pleural line with a thin hyperechoic outside wall and a hypoechoic centrum.

Case 2

M.A, a female was born at 33 + 6 weeks of GA by CS due to preterm labor (birth weight 2040 g, 25–50th percentile). The infant required positive pressure ventilation after birth and was admitted to our NICU on nCPAP support (CPAP 6 cm H2O, FiO2 0.30). On admission, the newborn presented a progressive worsening RDS requiring endotracheal surfactant instillation, followed by mechanical ventilation [volume guarantee combined with assisted controlled ventilation (Vt 5 mL/kg and PIPmax 26 cm H2O, FiO2 0.23)]. The CXR confirmed the presence of diffuse ground-glass lungs compatible with hyaline membrane disease, together with an intrapulmonary air-filled lesion in the upper part of right lung. A pneumatocele was suspected (Figure 2A). LUS confirmed the presence of a hypoechoic area with irregular margins, as a multilobed cyst below the pleural line (Figure 2B). The clinical conditions quickly improved, and the infant was then extubated on day 2. Daily LUS were performed and they confirmed a slow reduction in the cyst’s size, which was no longer detectable on day 21, despite a persistence on the CXR. The infant was discharged on day 15 and a monthly CXR was performed. The CT scan was not performed, as it was considered not needed due to the clinical stability of the patient. A complete pneumatocele resolution was detected 4 months after birth. A follow-up visit was performed at 6 months after birth showing an adequate growth [weight at check: 6800 g (25th percentile), L 64 cm (50th percentile), CC 43 cm (50th percentile)], regular respiratory dynamics and oxygen saturation. Furthermore, no pulmonary infections were registered.

(A) Chest X-ray at the beginning in case 2: ground-glass lungs together with an intrapulmonary air-filled lesion on the apical right lung. (B) LUS at the beginning in case 2: intrapulmonary area with hypoechoic centrum and irregular margin below the pleural line, as pneumatocele.

Discussion

The use of LUS is an innovative and reliable tool in neonatology. The LUS is a feasible and accurate technique, allowing bedside diagnosis of different pulmonary diseases. However, the routine use of LUS in the NICUs in the past is limited by the presence of many confounding signs in neonates with lungs diseases, such as the absence of A-lines, the presence of pleural-line abnormalities, the interstitial syndrome, the occurrence of lung consolidation and air bronchogram, the pulmonary edema and the lung pulse [4]. Compared to CXR and CT scan, LUS has better accuracy, lower-cost and repeatability, without exposure to radiations. Till now, LUS has been used to study many neonatal pulmonary diseases such as RDS, transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN), pneumothorax and pneumonia [5], [6]. The increased use of LUS led to the diagnosis of many lung diseases in both children and adults. LUS is more sensitive than traditional CXR in detecting lung lesions [4]. The CXR failed to distinguish different forms and grade of severity of lung diseases. Indeed, RDS and TTN in the 1st h have similar clinical presentation and radiographic findings, as white lung imaging [4], LUS permits to distinguish between the two diseases, as the pulmonary edema, seen in both diseases, is combined with lung consolidation only in the RDS, but not in the TTN [4], [5], [6]. Moreover, LUS increases the accuracy in the differential diagnosis between the RDS and pneumonia. In fact, both cases showed echographic signs of lung consolidation but the irregular shape and the dendritic image of air bronchograms is considered the most sensitive and specific sign in neonatal pneumonia [7]. Sometimes, in difficult cases, the typical echographic appearance together with the specific clinical symptoms improve the accuracy of LUS [7]. No data are reported about the ultrasonographic appearance of neonatal pneumatoceles. In our patients, LUS was a very useful tool in the acute phase as it was able to detect the pneumatocele’s site, size and composition. In fact, the detection of the specific and well-defined echographic lesions, allowed us to make a diagnosis despite the presence of confounding parenchymal alterations, due to the simultaneous presence of RDS. However, in the subacute phase, LUS lost its sensibility, as the progressive reduction of the cyst’s size did not allow its recognition in the lung parenchyma.

To our knowledge, this is the first report about two cases of early ultrasonographic diagnosis and follow-up of neonatal pneumatoceles. Further studies are needed to confirm and validate our preliminary results. Repeated LUS could become a sensible tool for bedside diagnosis and follow-up of neonatal pulmonary cysts. The routine use of LUS in the NICUs would be desirable in order to improve the expertise of clinicians and the accuracy of LUS, to reduce the use of X-rays and thus, the neonatal exposure to radiations.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Hussain N, Noce T, Sharma P, Jagjivan B, Hedge P, Pappagallo M, et al. Pneumatoceles in preterm infants- incidence and outcome in the post-surfactant era. J Perinatol. 2010;30:330–6.10.1038/jp.2009.162Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Maranella E, Conte E, Di Natale C, Coclite E, Di Fabio S. Disseminated, large-sized neonatal pneumatoceles: the wait-and-see strategy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49:E69–71.10.1002/ppul.22831Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] De Bie HMA, Van Toledo-Eppinga L, Verbene JIML, Van Elburg RM. Neonatal pneumatocele as a complication of nasal continuos positive airway pressure. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;86:F202–3.10.1136/fn.86.3.F202Search in Google Scholar

[4] Chen SW, Fu W, Liu J, Wang Y. Routine application of lung ultrasonography in the neonatal intensive care unit. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e5826.10.1097/MD.0000000000005826Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Liu J. Lung ultrasonography for the diagnosis of neonatal lung disease. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014 27:856–61.10.3109/14767058.2013.844125Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Vergine M, Copetti R, Brusa G, Cattarossi L. Lung ultrasound accuracy in respiratory distress syndrome and transient tachypnea of the newborn. Neonatology. 2014;106:87–93.10.1159/000358227Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Liu J, Liu F, Liu Y, Wang HW, Feng ZC. Lung ultrasonography for the diagnosis of severe neonatal pneumonia. Chest. 2014;146:383–8.10.1378/chest.13-2852Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Case Reports – Obstetrics

- Trisomy 9 presenting in the first trimester as a fetal lateral neck cyst and increased nuchal translucency

- A case of intrauterine closure of the ductus arteriosus and non-immune hydrops

- Pregnancy luteoma: a rare presentation and expectant management

- A pregnant woman with an operated bladder extrophy and a pregnancy complicated by placenta previa and preterm labor

- Consecutive successful pregnancies of a patient with nail-patella syndrome

- A multidisciplinary management approach for patients with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and multifetal gestation with successful outcomes

- A uterus didelphys with a spontaneous labor at term of pregnancy: a rare case and a review of the literature

- Case Reports – Fetus

- Prenatal diagnosis of ring chromosome 13: a rare chromosomal aberration

- Case Reports – Newborn

- Late-onset pubic-phallic idiopathic edema in premature recovering infants

- An unusual cause of neonatal shock: a case report

- Early ultrasonographic follow up in neonatal pneumatocele. Two case reports

- Nonsyndromic extremely premature eruption of teeth in preterm neonates – a report of three cases and a review of the literature

- Successful outcome of a preterm infant with severe oligohydramnios and suspected pulmonary hypoplasia following premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) at 18 weeks’ gestation

- Onset of Kawasaki disease immediately after birth

- Short rib-polydactyly syndrome (Saldino-Noonan type) undetected by standard prenatal genetic testing

- Severe congenital autoimmune neutropenia in preterm monozygotic twins: case series and literature review

- Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae sepsis in an extremely premature infant

Articles in the same Issue

- Case Reports – Obstetrics

- Trisomy 9 presenting in the first trimester as a fetal lateral neck cyst and increased nuchal translucency

- A case of intrauterine closure of the ductus arteriosus and non-immune hydrops

- Pregnancy luteoma: a rare presentation and expectant management

- A pregnant woman with an operated bladder extrophy and a pregnancy complicated by placenta previa and preterm labor

- Consecutive successful pregnancies of a patient with nail-patella syndrome

- A multidisciplinary management approach for patients with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and multifetal gestation with successful outcomes

- A uterus didelphys with a spontaneous labor at term of pregnancy: a rare case and a review of the literature

- Case Reports – Fetus

- Prenatal diagnosis of ring chromosome 13: a rare chromosomal aberration

- Case Reports – Newborn

- Late-onset pubic-phallic idiopathic edema in premature recovering infants

- An unusual cause of neonatal shock: a case report

- Early ultrasonographic follow up in neonatal pneumatocele. Two case reports

- Nonsyndromic extremely premature eruption of teeth in preterm neonates – a report of three cases and a review of the literature

- Successful outcome of a preterm infant with severe oligohydramnios and suspected pulmonary hypoplasia following premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) at 18 weeks’ gestation

- Onset of Kawasaki disease immediately after birth

- Short rib-polydactyly syndrome (Saldino-Noonan type) undetected by standard prenatal genetic testing

- Severe congenital autoimmune neutropenia in preterm monozygotic twins: case series and literature review

- Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae sepsis in an extremely premature infant