Abstract

The requirement for sustainable and environmentally friendly materials has led to the exploration of lignin as a potential candidate for protective coatings in various industrial applications. Recent researches demonstrate the feasibility of lignin-based coatings for enhancing wear and corrosion resistance. The lignin improved the coating’s barrier properties and prevented corrosive electrolytes from contacting the metal. The lignin additives also functionalised wear resistance coating. This review points out the improvements in using lignin extraction to produce high-quality materials suitable for corrosion and wear resistance coating purposes. However, the application of lignin in coatings faces significant challenges, primarily due to its heterogeneous and complex nature, which complicates the attainment of uniform and reliable coating qualities. Moreover, it emphasises the need for further studies on lignin to harness lignin’s potential. Future research needs include the development of standardised methods for lignin characterisation and modification, the exploration of novel lignin-based composites and the evaluation of lignin coatings in real-world applications. This review probes into the burgeoning field of lignin-based coatings, evaluating their potential for wear and corrosion resistance, and discusses the current state of research, challenges and future directions in this promising area.

1 Introduction

Corrosion and wear are well-known issues impacting our daily lives and industrial operations. Corrosion, a chemical or electrochemical reaction between materials and corrosive environments, can compromise the structural integrity of components (Carlos de Haro et al. 2019; Dastpak et al. 2018; El-Sheshtawy et al. 2021). Similarly, wear, caused by the mechanical interaction between surfaces, leads to material loss and functional degradation (Wang et al. 2023a). These issues could cause the degradation of materials, particularly metals, resulting in substantial economic losses and potential safety hazards (Tao et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2023a). These challenges are prevalent in various industries, including construction, automotive and marine sectors, necessitating effective mitigation strategies (Rasool et al. 2020; Xie et al. 2020). The estimated global cost of corrosion and wear is approximately 5 % of the world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for each (Koch 2017; Tao et al. 2019).

Applying protective coatings is an effective way to prevent materials from corrosion and wear. Polymer coating, a major coatings category, has been widely used as corrosion protection for metal materials due to its low conductivity and barrier properties (Motlatle et al. 2022; Ulaeto et al. 2023; Yang et al. 2024a). Besides, the mechanical properties like hardness and strength of polymer coatings are also important since they affect their durability under wear conditions (Yang et al. 2024b). However, polymer coating has historically relied on synthetic polymers and heavy metal-based compounds (Kausar 2018; Sadat-Shojai and Ershad-Langroudi 2009; Verma et al. 2019). These conventional coatings are fossil-based and pose significant environmental and health concerns. Their production often involves toxic precursors and generates hazardous byproducts, while their disposal leads to environmental contamination (Faccini et al. 2021; Gu 2003; Mhd Haniffa et al. 2016). The importance of green coatings is emphasised, which explores the development of environmentally friendly coatings for corrosion and wear protection, inspiring a shift towards sustainable, eco-friendly alternatives (Montemor 2014; Tharanathan 2003; Tian et al. 2012). The trend towards sustainable materials reflects a broader societal movement towards environmental responsibility and health-conscious industrial practices.

Lignin emerges as a promising alternative material for sustainable coating, which is a natural polymer found abundantly in plant cell walls and a byproduct of the paper and biofuel industries (Bajwa et al. 2019; Calvo-Flores and Dobado 2010; Grabber 2005, Vanholme et al. 2008). Its eco-friendliness stems from its renewable origin and biodegradability (Calvo-Flores and Dobado 2010; Cao et al. 2018; Zakzeski et al. 2010). Recent studies have highlighted lignin’s potential as a sustainable coating material, owing to its inherent properties such as natural antioxidants, anti-corrosion, wear resistance and UV-blocking capabilities (Thakur 2013). Therefore, it is helpful to summarise recent reports on lignin corrosion and wear resistance coatings.

This review aims to probe into the applications of lignin-based coatings in providing anti-corrosion and wear resistance, exploring how this bio-based material can contribute to sustainable industrial practices while addressing the pressing challenges of material degradation. This review reviewed recent publications about lignin-based corrosion resistance coating according to the published year. The lignin type and coating synthesis method are briefly introduced. The base material and corrosion evaluation methods are crucial when discussing corrosion resistance performance. The mechanism of how adding lignin could improve coatings’ corrosion resistance is also summarised. Lignin mainly works as the functionalisation additive instead of the friction-resistant improver in lignin-involved wear resistance coating. Despite this, recent works involving lignin coating with abrasion characterisation are summarised in the review. The lignin type, substrate material and simplified coating synthesis method are introduced. Additionally, the limitations and challenges of current works are mentioned separately following each section. The potential research directions and future applications are suggested at the end of this review.

2 Lignin-based corrosion resistance coatings

In this section, recently published articles since 2020 about lignin corrosion-resistant coating are compared their performance. The coating preparation/synthesis methods and the mechanism for improving the performance are also categorised.

2.1 Recent studies about lignin anti-corrosion coatings

Representative studies from 2020 to 2024 about lignin anti-corrosion coatings are listed in Table 1. This review focuses on grafting lignin or adding it as an additive in organic coatings. Lignin extracted from various approaches is used as raw material for coating synthesis. The coatings are mainly applied on iron alloys and are also available on aluminium alloys. The typical method for evaluating corrosion resistance is electrochemical measurement, including electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and potentiodynamic polarisation tests with the Tafel curve. Lignin acts as a filter additive in coatings, increasing barrier properties, thereby improving coating corrosion resistance.

Recent studies about lignin corrosion-resistance coatings.

| Lignin | Substrate | References |

|---|---|---|

| Kraft lignin | Carbon steel | (Dastpak et al. 2020a; Diógenes et al. 2021; Diógenes et al. 2023; Gao et al. 2020, 2021; Komartin et al. 2021; Laxminarayan et al. 2023; Tan et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2022a; Wu et al. 2022b) |

| Plating steel | (Dastpak et al. 2020b, 2021) | |

| Aluminium alloy | (Cao et al. 2021; Moreno et al. 2021; da Cruz et al. 2022) | |

| Organosolv lignin | Plating steel | Dastpak et al. (2020b) |

| Enzymatic hydrolysis lignin | Carbon steel | (Cao et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2022b) |

| Sulfonated lignin | Carbon steel | (Abdelrahman et al. 2022; Qian et al. 2020; Liao et al. 2024) |

| Lignin nanocellulose | Carbon steel | Zhang et al. (2021) |

| Termite frass extracted lignin | Carbon steel | Kulkarni et al. (2021) |

| Reductive catalytic fractionated lignin | Carbon steel | Jedrzejczyk et al. (2022) |

2.1.1 Kraft lignin coatings on carbon steel

For example, Dastpak et al. (2020a) explored a two-layer protective coating, comprising plasticised lignin and anodised layers, on low-alloy steel (S355) for enhanced corrosion resistance. This study revealed a significantly improved kraft lignin solubility in a triethyl citrate mixture, as shown in Figure 1. The coating was sprayed on anodised steel and evaluated under linear sweep voltammetry. The combined lignin-anodised coating demonstrated substantially improved corrosion resistance; the corrosion current density decreased from 15 μA/cm2 to 0.5 μA/cm2 for anodised and lignin-coated steel. The surface oxide extended the diffusion pathways of the corrosive moieties, and the lignin covered the porous oxide, preventing the permeation of electrolyte through the porous towards the steel interface.

Lignin coating preparation and electrochemical performance of the two-layer coating on low-alloy steel. From Ref. (Dastpak et al. 2020a), used under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND license.

Similarly, Tan et al. (2020) innovated the lignin microspheres as the carrier for corrosion inhibitor benzotriazole, significantly enhancing the release efficiency of the inhibitor in response to changes in pH levels typical of corrosive environments. The microspheres were incorporated into waterborne epoxy resin coatings, demonstrating substantial self-healing properties and improving corrosion resistance. The EIS impedance of the enhanced coating on steel showed one order of magnitude higher than non-lignin coating after 35 days immersed in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, reaching 106 Ω cm2. Besides, the lignin microspheres incorporated coating shows excellent self-healing performance for artificial scratches.

In addition to Dastpak and Tan’s work, Gao et al. (2020) developed a lignin-(2,3-epoxypropyl)trimethyl ammonium chloride (EPTAC), which exhibits exceptional corrosion-resistant behaviour in hydrochloric acid solutions. The lignin-EPTAC molecules formed a robust protective film on the iron surface. This adsorption of lignin-EPTAC was a conjugated system dominated by the benzene ring of lignin-EPTAC. Besides, a positive interaction between the metal surface and the positively charged N ions in the head group of lignin-EPTAC also increased the film’s adsorption on steel. The surface roughness of steel samples was reduced, and the protected film on steel achieved an impressive inhibition efficiency of 97.80 % at a concentration of 100 mg/L.

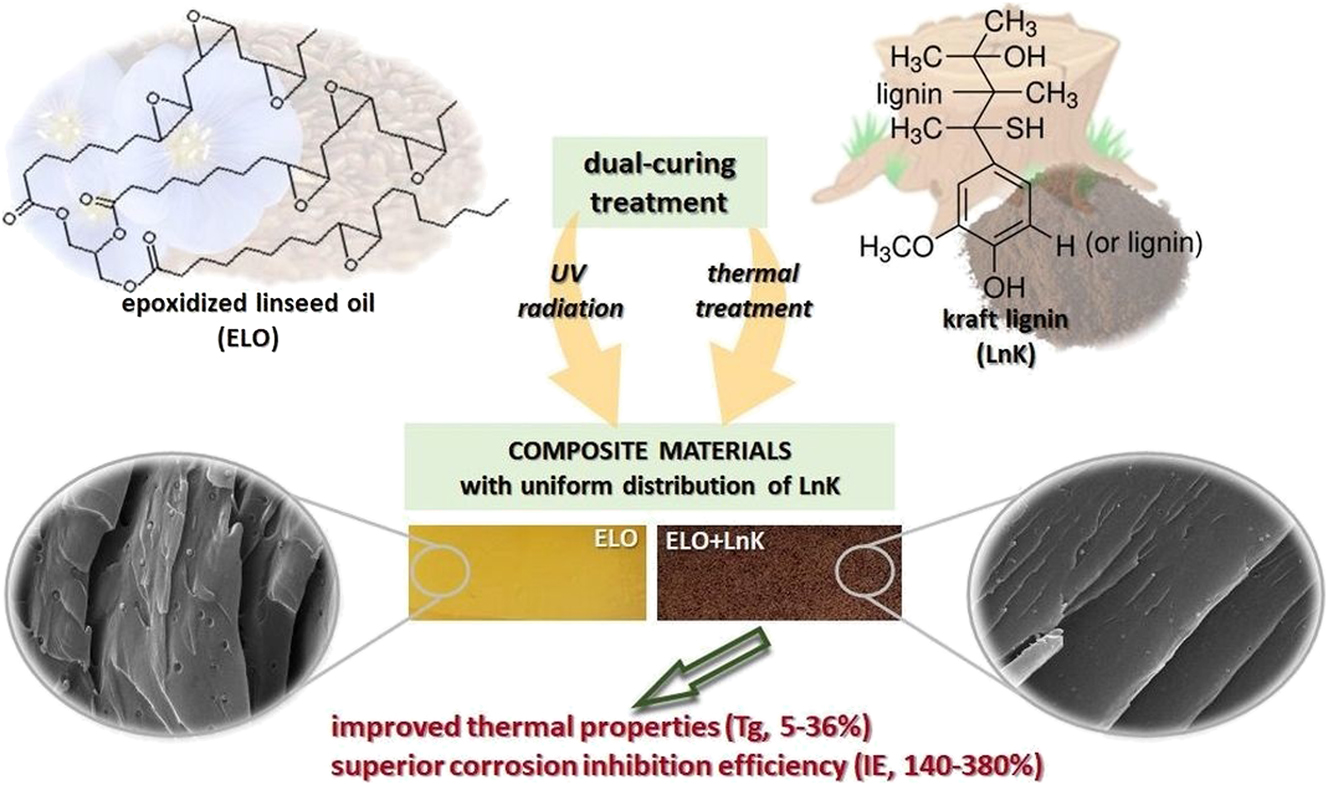

Likewise, Komartin et al. (2021) developed composite coating contented epoxidised linseed oil (ELO) and kraft lignin (LnK) utilising a double-curing procedure involving UV radiation and thermal treatment, as shown in Figure 2. The Tafel curves underscored the composites’ potential as efficient anti-corrosion coatings, particularly when coated on carbon steel. The composite with 5 % LnK exhibited the highest corrosion inhibition efficiency. The EIS showed that after 30 min immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, this optimal coating had an impedance over 2 × 107 Ω cm2. The corrosion rate decreased two orders of magnitude compared to uncoated steel, while the corrosion inhibition efficiency reached 99.9 %. After adding LnK, the coating maintained its hydrophobicity, which works as a barrier layer and is beneficial for corrosion resistance.

Schematic of curing treatment of ELO-LnK coating. From Ref. (Komartin et al. 2021), used under Creative Commons CC BY license.

Similarly, Diógenes et al. (2021) replaced coal tar with Kraft lignin and addressed the carcinogenic and mutagenic risks associated with conventional coal tar epoxy coatings. Acetylation of lignin was employed to enhance its compatibility with bisphenol A diglycidyl ether, forming epoxy-lignin resins in various concentrations. The coating barrier layer prevents the electrolyte from reaching the steel surface, and EIS results revealed that coatings with 7.5 % and 15 % lignin on steel maintained comparable impedance values to commercial coatings in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, which was above 1011 Ω cm2, ensuring adequate corrosion protection.

Following their previous work, Diógenes et al. (2023) employed acetylated lignin (AKL) as a bio-additive in epoxy coatings to enhance their anti-corrosive properties. The AKL was incorporated with diglycidyl ether of bisphenol-A resin, and the isophorone diamine acted as the curing agent. The salt spray test, in which samples were analysed every 7 days using EIS measurement, was used to evaluate the coating’s corrosion resistance. After 42 days of salt spray test, the EIS results showed that the impedance for coating on steel with 15 % AKL remained at 1011 Ω cm2, while the coating without AKL showed the impedance at 109 Ω cm2 on steel. The coatings with AKL exhibited enhanced performance in blocking Na+ and Cl− ion migration, thereby slowing the corrosion process.

In addition, Gao et al. (2021) explored the corrosion inhibition effectiveness of lignin-acrylic acid (AA) and lignin-acrylamide (AM) copolymers in the HCl solution. The lignin-AA copolymer demonstrated better corrosion inhibition efficiency than the lignin-AM copolymer, which was attributed to the higher adsorption capacity of lignin-AA on the carbon steel surface. The lignin-AA could modify the surface of carbon steel by creating a protective layer that reduces corrosion rates. Quantum chemical calculations suggested that the higher inhibition efficiency of lignin-AA was due to its lower energy gap and stronger adsorption activity. According to the Tafel curve, the current density of lignin-AA corrosion was 41.12 μA/cm2 in 1 mol/L HCl solution. The optimal lignin-AA inhibitor showed charge transfer resistance over 300 Ω cm2, which is one order of magnitude higher than blank steel.

Similarly, Wang et al. (2022a) obtained lignin-corrosion inhibitor (LCI) through the conjugation of nicotinic acid to lignin through hydrolytically cleavable ester linkage and then integrated LCI into lignin-based polyurethane (LPU) coatings. The LPU coating with LCI could release the corrosion inhibitor in response to the emergence of microcracks, thereby providing self-healing properties. The EIS results showed that the coating on steel electrodes with optimal LCI content had charge transfer resistance at 1.6 × 105 Ω cm2 after 8 h of immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, and the Tafel curve also showed a 6,700 times lower corrosion rate compared to bare steel. An increase in impedance with immersion was observed after the artificial scratch.

Likewise, Wu et al. (2022b) modified lignin with hexamethylene diisocyanate and then incorporated modified lignin into hydroxy acrylic resin to create lignin-based polyurethane (MLPU) composites. The water contact angle of MLPU was higher than non-modified LPU. After 90 min immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, the MLPU coating on the steel electrode had an impedance at 4 × 104 Ω cm2, higher than LPU. However, the micropores formed by ML particles caused the quick penetration of electrolyte solution to the coating/metal substrate interface, leading to a rapid impedance decrease after 7.5 h of immersion.

Besides, Laxminarayan et al. (2023) enhanced the performance of epoxy novolac coatings by incorporating size-fractionated technical Kraft lignin particles. Coatings with sieved lignin particles applied on mild steel exhibited about 31 % lower rust creep after extended salt spray exposure for 70 days than those with unsieved lignin, without any observed surface defects or chemical degradation. The strong interactions between the lignin particles and epoxy resin in the coating matrix were believed to impede the ingress of salt water, thereby enhancing the barrier property of the lignin-incorporated coating.

2.1.2 Kraft lignin coating on plating steel

Turning to a different substrate material for lignin’s application, Dastpak et al. (2020b) conducted a study focused on the solubility of kraft lignin and organosolv lignin in commonly used solvents in the paint industry. In addition, this study also applied lignin coating using the solvents on iron-phosphate steel panels and used EIS to assess the anti-corrosive properties. The kraft lignin coating demonstrated short-term anti-corrosive characteristics. The charge transfer resistance for kraft lignin-coated steel was 1.5 × 105 Ω cm2 after 1 h of immersion in 5 % NaCl solution, while the charge transfer resistance was 1.9 × 103 Ω cm2 for bare steel at the same immersion condition. The lignin coating worked as the barrier layer, which separated the corrosive medium from steel. However, a notable decrease in resistance over prolonged exposure was observed. The charge transfer resistance decreased to 1.1 × 104 Ω cm2 after 24 h immersed in 5 % NaCl solution, indicating limitations in long-term protection.

Subsequently, Dastpak et al. (2021) developed a biopolymeric anti-corrosion coating using colloidal lignin particles (CLP). The CLP was prepared using a solution of softwood kraft lignin and diethylene glycol monobutyl ether via solvent exchange. The CLP aqueous dispersion was mixed with oxidised cellulose nanofibers, and the electrophoretic deposition method was used to apply these biopolymers to hot-dip galvanised steel. The EIS results for the optimal CLP coating showed a higher charge transfer resistance than bare hot-dip galvanised steel, reaching 1.4 × 104 Ω cm2 after 15 days of immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. The SEM analysis showed that the coalescence of CLPs occurs during the drying of composite coatings, forming a barrier layer and reducing the penetration of the electrolyte to the metal.

2.1.3 Kraft lignin coating on aluminium alloy

While the above studies focused on steel substrate, Cao et al. (2021) constructed the ZnAl-layered double hydroxide modified with lignin as an eco-friendly anti-corrosive composite film on AA 7075 aluminium alloy surfaces. The lignin–metal complex is formed due to the phenolic groups of lignin and metal ions, which possess excellent metal complexing properties. After being immersed in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution for 7 days, the EIS results showed that the impedance for ZnAl-layered double hydroxide modified with lignin on aluminium alloy remained at 4.4 × 104 Ω cm2, which was one order of magnitude higher than for bare aluminium alloy and also ZnAl-layered double hydroxide modified without lignin. This research marks a significant advancement in corrosion protection strategies, particularly for aluminium alloys, widely used in aerospace and other industries.

Similarly, Moreno et al. (2021) overcame the instability of lignin nanoparticles (LNPs) in acidic and basic environments by developing lignin oleate nanoparticles. By controlling the degree of esterification, the stability of OLNPs in both acidic and basic aqueous dispersions could be enhanced. This stability was attributed to the alkyl chains in the OLNPs, which created a hydration barrier, delaying protonation/deprotonation of carboxylic acid and phenolic hydroxyl groups. The optimal OLNP coating had satisfactory barrier properties. The Tafel curve in Figure 3 showed that the coated aluminium specimens had significantly lower corrosion current density values (2.54 × 10−7 A/cm2) than non-coated aluminium substrates (1.35 × 10−4 A/cm2).

Application of OLNPs as an anti-corrosion coating for Al alloy and Tafel plots after exposure to a 5 % NaCl solution at 25 °C for 15 h. From Ref (Moreno et al. 2021), used under Creative Commons CC BY license.

Likewise, da Cruz et al. (2022) chose copper as the electrocatalyst to depolymerise lignin in biomass-based levulinic acid. Tafel and EIS measurements further evaluated the depolymerised lignin as an anti-corrosion coating on aluminium. The Tafel curve showed that the inhibition efficiency of lignin coating on Al could reach 74 % in 5 % NaCl solution. The impedance could reach 1.4 × 104 Ω cm2 during EIS measurement.

2.1.4 Enzymatic hydrolysis lignin coating on carbon steel

Differing from the above strategies using Kraft lignin, Cao et al. (2020) developed lignin-based polyurethane anti-corrosive coatings without catalysts. Though an allylation reaction, this study conversed phenolic hydroxyls in enzymatic hydrolysis lignin to primary aliphatic hydroxyls. Then, lignin-based polyols were produced through a thermally initiated thiol-ene reaction. These polyols were then polymerised with hexamethylene diisocyanate to form the LPU coatings. EIS evaluated the coatings’ corrosion resistance ability. The coating showed significant barrier properties, while the impedance on carbon steel remained at 3.9 × 1010 Ω cm2 after 40 days of immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution.

Similarly, Wang et al. (2022b) extracted low molecular weight fractions from enzymatic hydrolysis lignin (EHL) via a bioethanol fractionation process and then directly epoxidised bioethanol fractionated lignin (BFL) to create BFL-based epoxy resin. The lignin-based anti-corrosive epoxy coatings with 100 % BFL-based epoxy contained around 15 % lignin. The EIS spectra showed that lignin epoxy coating applied on steel could reach the impedance at 1010 Ω cm2 when immersed in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution for 1 h. The impedance after 7 days could remain at 109 Ω cm2. This lignin epoxy coating’s excellent corrosion resistance was contributed by its high impermeability and dense structure, which can delay corrosive media penetration into the coating.

2.1.5 Sulfonated lignin coating on carbon steel

Furthermore, Qian et al. (2020) developed a self-healing corrosion protection coating through the microcapsules fabricated by employing sodium lignosulfonate to load with an isophorone diisocyanate. Tafel curve showed that the self-healing coating on steel substrate had the corrosion current at 10−7 A after rupture and healed in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, which is two orders of magnitude lower than bare steel. Moreover, the microcapsule integrated coating showed superior resistance to UV-induced ageing, slowing the ageing process and preserving the coating’s mechanical integrity under prolonged UV exposure.

In addition, Abdelrahman et al. (2022) extracted sodium lignosulfonate (SLS) as a renewable corrosion inhibitor from lignocellulosic waste using sulfomethylation to the lignin. The sulfomethylation could increase the lignin’s aqueous solubility and enhance its functionality as a corrosion inhibitor. Potentiodynamic anodic polarisation measurements were used to evaluate the corrosion resistance for SLS applied on steel. The introduction of more SLS reduced the corrosion rate due to the sulfonated groups’ improved protection of steel against corrosion. The corrosion inhibition efficiency could reach 90.23 % in 0.1 mol/L HCL solution.

Likewise, Liao et al. (2024) investigated the anti-corrosion performance of sodium lignosulfonate (SLS) for carbon steel, highlighting protection against corrosion in acidic environments. Only 20 mg/L SLS could result in a maximum corrosion inhibition efficiency of 98 % in 1 mol/L HCl solution. Besides, the EIS results showed an increasing impedance with the extending immersion time when the SLS concentration reached 20 mg/L. The adsorption of SLS on a carbon steel surface formed a protective film, which was the main mechanism for its high inhibition efficiency. In addition, the benzene ring structure in lignin could create a complex solution with Cl− and H+ ions, which inhibited further corrosion.

2.1.6 Lignin nanocellulose coating on carbon steel

Turing to lignin nanocellulose, Zhang et al. (2021) overcame the drawbacks of PVA coatings by incorporating lignin nanocellulose (LNC) and heating treatment. Due to the abundance of hydroxyl groups, PVA coating had high water absorption and poor corrosion resistance. Adding LNC led to lower porosity, which decreased the permeation and absorption of free and bound water. The well-dispersed LNC in PVA extended the permeation path of corrosive media. Besides, the heat treatment eliminated hydroxyl groups, reduced water penetration channels and improved barrier properties. The EIS results showed that LNC PVA coating after heat treatment remained at 2.7 × 106 Ω cm2 after 72 h of immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution.

2.1.7 Termite frass extracted lignin coating on carbon steel

Shifting to termite frass-extracted lignin, Kulkarni et al. (2021) used lignin extracted from termite frass by Klason’s method. The extracted lignin was mixed with water and metal binder to form the slurry. The coating was applied to carbon steel, and the corrosion resistance was evaluated using the Tafel curve and EIS measurements in 0.1 M and 0.5 M NaOH solutions. The Tafel curve showed that lignin at 600 ppm concentration in 0.5 M NaOH had an inhibition efficiency of 70 %. The polarisation resistance for the lignin coating was four times higher than that of blank steel in 0.5 M NaOH solution. The protective layer formation by adding lignin safeguarded the metal against corrosion.

2.1.8 Reductive catalytic fractionated lignin coating on carbon steel

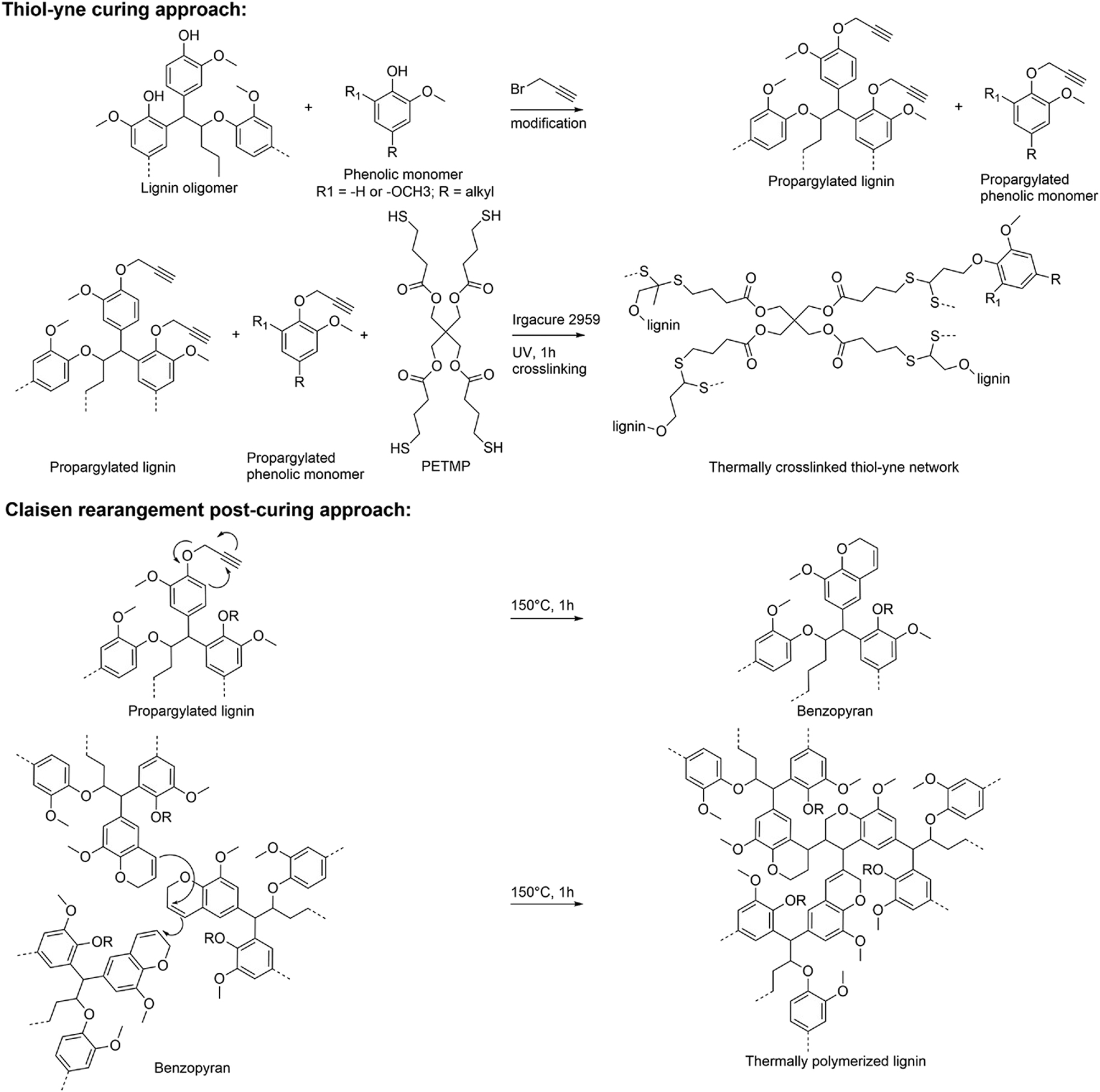

In addition, Jedrzejczyk et al. (2022) designed the film with high lignin content (46–61 %) through a tandem UV-initiated thiol-yne ‘click’ synthesis and Claisen rearrangement strategy as shown in Figure 4. The lignin originated from a nickel-catalysed birch wood reductive catalytic fractionation (RCF) process. The films exhibited superior barrier properties and high corrosion protection, suggesting that unfractionated lignin without energy-intensive fractionation of depolymerised lignin into monomers and oligomers could be a viable component in thermoset polymeric films. These films displayed remarkable adhesion to steel surfaces, and the EIS measurements proved that after 21 days of immersion in 0.05 M NaCl solution, the steel electrode with lignin coating remained impedance at 1010 Ω cm2.

Synthetic approach for lignin-based protective films via tandem UV-initiated thiol-yne chemistry and Claisen rearrangement. From Ref. (Jedrzejczyk et al. 2022), used under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND license.

2.2 Other corrosion-related lignin applications

Besides the direct electrochemical measurement, corrosion resistance may also related to hydrophobicity, chemical resistance, rust conversion, etc.

Hydrophobicity indicates the coatings’ ability to prevent water and moisture from adhering to the surface. Wu et al. (2022a) obtained lignin nanoparticles (LNPs) from the byproduct of the wheat straw pulping process through a nanoprecipitation method. The LNPs were incorporated into polyurethane coating, reaching the water contact angle of 114°. The inherent properties of lignin increased the hydrophobicity of PU coating. Wang et al. (2023b) incorporated in-situ polymerised polyaniline/lignin (PL) composites into waterborne polyurethane (WPU) to increase the impermeability to water. The PL-WPU decreased by 25.59 % in rapid chloride ion migration, improving the coating’s barrier properties against moisture and chloride ion penetration.

Chemical resistance indicates coatings’ properties of protecting underlying material from harsh chemicals that can accelerate degradation and corrosion. Patil et al. (2023b) added diazotised salt to lignin by coupling reaction to form pigments, and the pigments were incorporated into an epoxy-polyamine matrix to create composite coatings. The coatings were applied to mild steel surfaces for a chemical resistance test. The composite coatings showed moderate resistivity towards the chemicals (5 % NaOH, 3.5 % HCl and 5 % NaCl) while exposed for 7 days. Patil et al. (2023a) synthesised lignosulphonate (LS) functionalised azo pigments and the epoxy-polyamine composite coatings were applied on steel surfaces for chemical resistance evaluation. The aniline-azo-LS coatings showed improved stability immersed in 1 % HCl, 5 % NaOH and 5 % NaCl solution.

Rust conversion may be vital for corrosion resistance as it transforms existing rust into a stable compound and acts as a protective shield, preventing further oxidation and deterioration of the metal. Osman et al. (2023) extracted oil palm frond (OPF) lignin through soda and organosolv pulping methods and used OPF lignin as a rust converter for archaeological cannonballs. The treated rust showed a transformation into an amorphous form. Ferric irons chelate and coordinate with hydroxyl groups in lignin and form stable complexes of Fe–O–C structure, retarding iron ions combining with oxygen. Nasrun et al. (2023) used soda pulping to extract lignin from coconut husk. Its high phenolic-OH content facilitated the transformation of rust into a less harmful and more adherent form. The conversion rate reached 85 %, preserving archaeological iron artefacts from corrosion.

2.3 Mechanisms for lignin corrosion resistance coating

Lignin, as a complex aromatic polymer found in the cell walls of plants, has garnered significant interest due to its potential applications in corrosion-resistant coatings due to its unique chemical properties and structure. The functional groups within lignin provide multiple pathways for enhancing its corrosion resistance capabilities.

Lignin’s polyphenolic structure contributes to its excellent barrier properties. When applied to metal surfaces, the dense, cross-linked lignin network forms a highly impermeable layer. This network effectively prevents water and oxygen penetration, which are primary agents of corrosion. Studies have shown that the high density of the lignin layer significantly reduces the rate of oxidative degradation, thereby extending the lifespan of the coated materials.

Various functional groups in lignin, such as hydroxyl, methoxy and carboxyl, facilitate strong adhesion to metal substrates. This strong adhesion is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the protective layer over time under mechanical stress. Enhanced adhesion improves the coating’s durability and resistance to mechanical damage, which keeps the integrity of the protective layer over time.

Lignin’s natural antioxidant properties, primarily due to its phenolic compounds, play a crucial role in corrosion inhibition. The phenolic hydroxyl groups in lignin can effectively reduce free radicals and reactive oxygen species, mitigating the electrochemical reactions that lead to corrosion. Lignin’s antioxidative capability is further enhanced when chemically modified or combined with other additives, improving its protective performance.

The protective performance of lignin can be further enhanced through chemical modifications or by combining it with other additives. Chemical modifications of lignin, for example, grafting with other polymers or introducing additional functional groups, can improve the compatibility of lignin with various substrates and enhance its barrier properties. Additionally, incorporating nanomaterials like graphene into lignin-based coatings can create synergistic effects, further improving their mechanical strength, thermal stability and corrosion resistance.

Several research studies have demonstrated the efficacy of lignin-based coatings in various industrial applications. For example, lignin-coated steel structures in marine environments have improved saltwater corrosion resistance, where long-term durability and environmental resistance are critical.

2.4 Challenges and limitations

The investigation into lignin-based corrosion-resistant coatings has emerged. Lignin is expected to be a sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative to protective materials. However, despite the benefits, the development and application of lignin-based coatings encounter several challenges and limitations that must be addressed.

One concern is the inherent variability in lignin’s chemical structure, which results from different extraction methods. The variability in lignin’s chemical structure obtained through different extraction strategies can lead to inconsistent performance in coating applications, making it difficult to standardise and predict the behaviour of lignin-based coatings.

Furthermore, achieving an optimal, uniform dispersion of lignin particles within the coating matrix is challenging. Uniform dispersion is crucial for ensuring good adhesion to the substrate and uniform protection, which affects the coating’s overall durability and effectiveness.

Moreover, integrating lignin into traditional coating systems without compromising mechanical properties and corrosion resistance is still complex. The complexity of this integration process requires simplification to reduce the cost while maintaining or enhancing the performance of coatings.

Additionally, there is a need for more comprehensive studies on the long-term stability and degradation behaviour of lignin-based coatings in various environmental conditions to understand and mitigate potential limitations.

3 Lignin-based wear resistance coatings

This section summarises recently published reports about improving the wear resistance of lignin coatings through various preparation and synthesis methods and the corresponding mechanisms.

3.1 Recent studies about lignin wear resistance coatings and mechanism

Recent studies about lignin wear resistance coatings are listed in Table 2. Various extraction methods are used to obtain lignin, which can be used as a raw material for synthesising coatings that can be applied to various surfaces such as wood, steel, foam and textiles. In addition to standard and tribology tests, researchers use other methods to evaluate the resistance of coatings to corrosion. These methods include weight and sandpaper tests. It is important to note that few reports suggest that lignin significantly enhances the wear or abrasion resistance of coatings. On the other hand, additives such as SiO2 and cellulose nanocrystals help improve the resistance of coatings.

Recent studies about lignin wear-resistant coatings.

| Lignin | Substrate | Application of lignin | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kraft lignin | Steel | Hardener, hydrophobic particulate, lubricant, antioxidant | Henn et al. (2021) |

| Wood | Coating stabiliser, hydrophobic particulate | Bang et al. (2022) | |

| Fabric | Antibacterial, abrasion resistance, UV resistance | Baysal (2024) | |

| Sulfonated lignin | Steel | Lubricant | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| Nanoscale lignin | Steel | Refine grains | Chen et al. (2023b) |

| Organosolv lignin | Wood | Coating strengthener and toughener | Song et al. (2022) |

| Enzymatic hydrolysis lignin | Wood | UV resistance, wear resistance, reinforcer, flame retardant | (Huang et al. 2023; Ma et al. 2024; Ren et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2023b) |

| Lignin–cellulose | Bio-resin | Strengthener, wear resistance | (Shan et al. 2023a, 2023b) |

| Poplar wood powder | Bio-resin | Strengthener, wear resistance | Shan et al. (2023c) |

| Hydrothermal extraction lignin | Foam | Hydrophobic particulate | Jiang et al. (2022) |

3.1.1 Kraft lignin coating on steel

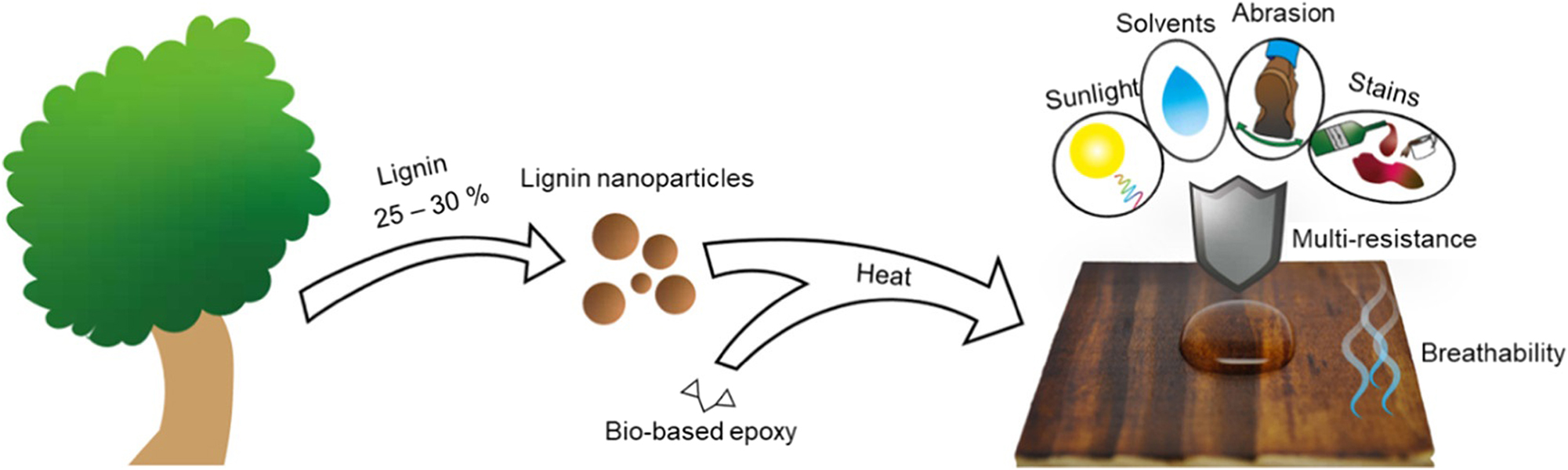

For instance, Henn et al. (2021) created a bio-based, durable and multi-resistant nanostructured epoxy compound coating combining colloidal lignin particles (CLPs) and glycerol diglycidyl ether (GDE), as shown in Figure 5. The coating could be applied on both stainless steel and pinewood substrates. The coating’s abrasion resistance was evaluated using a Taber Abrader following the ASTM D4060 method. The optimal GDE/CLP coating showed mass loss similar to commercial epoxy coatings since the optimal GDE/CLP ratio did not have excess monomer, leading to a suitable structure network.

The concept schematic of CLP–GDE films for multi-resistance. From Ref. (Henn et al. 2021), used under Creative Commons CC BY license.

3.1.2 Kraft lignin coating on wood

Turning from steel substrate to wood substrate, Bang et al. (2022) mixed kraft lignin with carnauba wax and created a hydrophobic coating that demonstrated promising friction and wear resistance stability. The physically mixed lignin/carnauba wax blend was sprayed on plywood or slide glass, and the friction resistance was evaluated by comparing contact angle change after peeling and attaching the test using scotch tape. With the addition of lignin, the coating’s contact angle remained over 135° after five times detachment tests. Lignin accelerated the atomisation of wax and achieved micro-roughness. The hydrogen bonding formed with the wood surface due to lignin also improved the coating’s stability under attachment and detachment tests.

3.1.3 Kraft lignin coating on fabric

Moving to the fabric substrate, Baysal (2024) used lignin, zinc oxide and water-based polyurethane to create composite coatings on polylactic acid spunlace nonwoven fabrics to increase wear resistance. The abrasion resistance for the fabric was evaluated according to the TS EN ISO 12947-2:2017 standard. The optimal coated fabric showed abrasion resistance at 5,000 cycles, mainly attributed to the synergistic effect of lignin and ZnO2, which increased the coating’s hardness.

3.1.4 Sulfonated lignin coating on steel

In addition, Zhang et al. (2022) doped N and B element-rich groups on lignin by microwave amination. The amine group acted as a nucleophile, which attacked the C–C bond and formed amide bonds with the lignin. This modification increased the lignin’s viscosity and enhanced its lubrication performance as an additive. A ball-on-plate setup with reciprocating motion evaluated the tribology performance of the lignin additive. Adding lignin significantly reduced the friction coefficient under 3 GPa by 40 % compared to non-lignin-added lubricants. The wear volume also decreased by 74 % after adding lignin. The mechanism was that adding lignin increased lubricant viscosity, thus increasing film thickness and reducing the contact between metal surfaces. And the lignin could adsorb to metal surfaces and improve the anti-wear properties.

3.1.5 Nanoscale lignin coating on steel

Likewise, Chen et al. (2023b) doped silicon nitride ceramics with nanoscale lignin to enhance its tribology properties. The pin-on-disk tribotest was applied to measure the ceramics’ friction coefficient and wear rate under 0.4 MPa pressure. 2 wt% doping of nanoscale lignin significantly reduces the friction coefficient to 0.22 with the lowest wear rate at 1.74 × 10−5 mm3/(Nm). The wear resistance enhancement was attributed to the forming of a surface layer containing graphene quantum dots derived from the lignin, which polished, repaired and cooled the interface, providing a barrier during friction.

3.1.6 Organosolv lignin coating on wood

Similarly, Song et al. (2022) valorised organosolv lignin to colloidal lignin micro-nanospheres (LMNS) and applied as a bio-based filler for waterborne wood coating (WBC) to improve the coating’s wear resistance. The abrasion weight loss was measured following the ASTM D4060 standard, and the addition of LMNS significantly influenced the coating’s abrasion resistance. The volume ratio of WBC to LMNS at 3:4 led to the lowest mass loss after the abrasion test. Adding LMNS improved the crosslink of the waterborne polymer matrix, thus increasing the coating’s hardness and adhesion to the wood surface.

3.1.7 Enzymatic hydrolysis lignin coating on wood

In addition to kraft and organosolv lignin, Ren et al. (2022) developed a superhydrophobic coating with significant abrasion resistance using hydrothermal-treated lignin nanoparticles (HLNPs). The HLNPs were prepared by enzymatic hydrolysis lignin, spraying the coating on the wood surface. The abrasion resistance for the coating was evaluated using a sandpaper abrasion test. The water contact angle for the optimal HLNP coating remained above 150° after 24 reciprocating cycles under 1 kPa with 800-mesh sandpaper. Introducing PDMS could tightly fix the HLNPs on the wood surface to form a rough structure and strong adhesion between the coating and the wood substrate. PDMS promoted the aggregation among HLNPs and the connection between HLNPs and reinforcer nanocellulose crystals, enhancing the abrasion resistance.

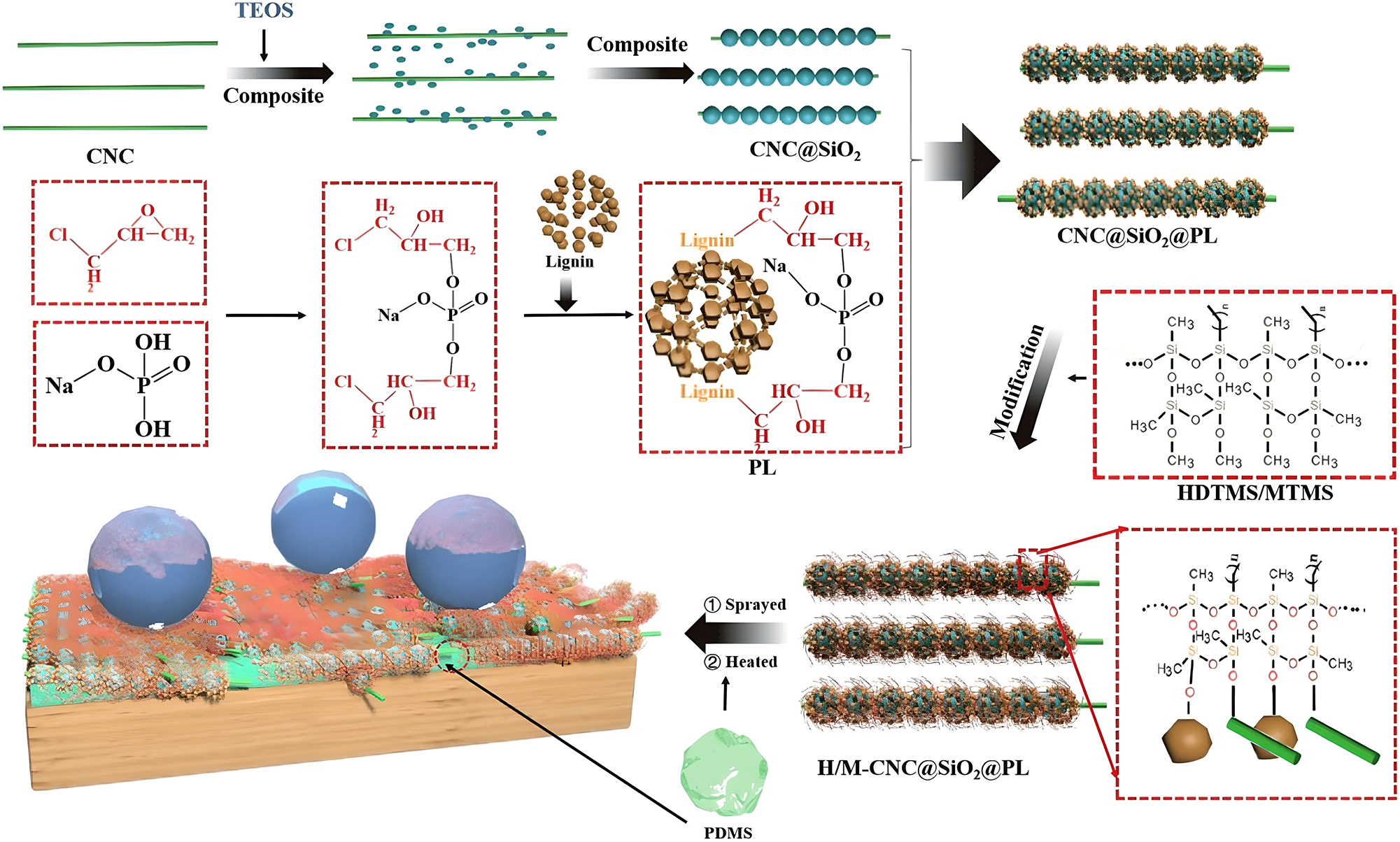

Likewise, Zhang et al. (2023b) developed a superhydrophobic coating using cellulose nanocrystals (CNC), silica (SiO2) and phosphorylated lignin (PL), as shown in Figure 6. This coating was applied to wood surfaces, and its abrasion resistance was evaluated using a sandpaper abrasion test. About 50 g weight was loaded on 300-mesh sandpaper under reciprocating motion until the water contact angle decreased to 150°. The addition of CNC improved the coating’s abrasion resistance, and the abrasion cycles reached to 37 times. The high crystallinity of CNC played an essential role in connecting the SiO2 particles. The CNC made SiO2 particles challenging to erase in the abrasion process and thus improved the coating’s wear resistance.

Preparation process demonstration of CNC@SiO2@PL-based superhydrophobic wood. From Ref. (Zhang et al. 2023b), used under Creative Commons CC BY license.

Similarly, Huang et al. (2023) developed a superhydrophobic coating using hydrothermal treated lignin nanoparticles (HLNPs) and Fe3O4. The lignin molecules aggregated into pellets through π-π bonds of aromatic rings, van der Waals forces and assembled LNPs. The coating was applied on wood and PU sponge surfaces, and its abrasion resistance was evaluated under an 800-mesh sandpaper reciprocating test. The abrasion cycles reached up to 87 times when TiO2 and nanocellulose crystals were added into the coating, which dispersed in the coating matrix and enhanced the abrasion resistance of the coating.

Furthermore, Ma et al. (2024) used dual-size lignin micro-nanospheres embedded in epoxy resin, forming a superhydrophobic coating with excellent abrasion resistance. A sandpaper abrasion test was used to evaluate the coatings’ abrasion resistance with reciprocating motion. The nanospheres (n-LMNSs) improved the coating’s water repellency, while the micro-nanospheres (m-LMNSs) worked as sacrificial filters to protect the micro-nano superhydrophobic structure. The m-LMNS additive increased the thickness of the coating’s abrasion resistance almost linearly.

3.1.8 Lignin–cellulose coating on bio-resin

Shifting the substrate to bio-resin, Shan et al. (2023b) investigated a lignin-based paper material and its friction properties. They obtained a recyclable wood-based lignin–cellulose film (LCF) from poplar powder using a solvent encapsulation strategy involving wood dissolution in deep eutectic solvent and lignin–cellulose structural reorganisation. The ball-on-disk test method evaluated the film’s tribology performance under various loads and environments. The LCFs displayed high wear resistance, low wear rate and long-lasting friction coefficient stability. The lignin matrix was the load transfer. The friction coefficient was around 0.2 at dry friction, which was attributed to the dense structure and self-reinforcement of LCF.

Shan et al. (2023a) also developed a highly wear-resistant and recyclable paper-based self-lubricating material with a layered interwoven structure using lignin, cellulose and graphene. Lignin acted as a natural binder and matrix, which adhered to a graphene cellulose network. The friction test was established by a ball-on-disk tribometer. Graphene became fragmented under the shear force of friction. The graphene fragment formed lubricant transfer film on the film surface, leading to the stability of friction coefficient at 0.15 and reduction of wear rate (3.9 × 10−3 mm3/(N m)).

3.1.9 Poplar wood powder coating on bio-resin

Shan et al. (2023c) developed a polydopamine (PDA) coating on the surface of polytetrafluoro-wax (PFW) by mixing PFW@PDA into lignin–cellulose bio-resin slurry. The tribology performance was evaluated by a ball-on-disk tribometer. The friction coefficient for the lignin–cellulose sample was 0.28, and the PFW@PDA added sample reduced the friction coefficient to 0.14. The PFW@PDA played the roles of friction reduction and anti-wear lubricant.

3.1.10 Hydrothermal extraction lignin coating on foam

In addition to fabric, Jiang et al. (2022) developed a superhydrophobic surface by synergistically assembling micro-islands using hydrothermal extracted lignin and dopamine. The coating applied on melamine foam maintained a water contact angle at around 150° after 20 times 2000-mesh sandpaper abrasion test.

3.2 Mechanisms for lignin wear resistance coating

The mechanisms through which lignin enhances wear resistance are multifaceted, involving chemical and physical interactions.

As a friction reducer, lignin additives can effectively separate two contact layers during wear and friction. This separation minimises the mechanical interlocking and adhesion, leading to a significant reduction in wear and friction. By forming a lubricating layer, lignin helps maintain the surfaces, significantly mitigating wear problems common in industrial applications.

Lignin also enhances the adhesion of coatings to substrates. When applied as a coating, lignin could form a robust adhesive layer that bonds well with the underlying material. This increased adhesion is crucial as it ensures the coating remains intact under mechanical stress and environmental factors, providing a continuous protective barrier. The adhesion properties of lignin are attributed to its complex structure, which allows for strong interactions with various substrates, including metals, polymers and ceramics.

The inherent rigidity and high molecular weight of lignin contribute to the strength of the coating film, making it more resistant to mechanical damage. Lignin’s polymeric nature imparts stiffness and toughness to the coating, which helps resist abrasion and impact forces. The cross-linked network structure of lignin molecules provides a stable matrix that can withstand mechanical stresses without significant deformation or degradation.

Lignin’s thermal stability is another critical factor in its effectiveness as a wear-resistant coating. Lignin can endure high temperatures without significant thermal degradation, essential for applications where coatings are exposed to elevated temperatures. This thermal stability ensures that the coating retains its protective properties even under harsh thermal conditions, extending the lifespan of the coated surfaces.

Lignin-based coatings also exhibit excellent resistance to environmental and chemical factors. The chemical composition of lignin includes phenolic and aromatic groups that provide resistance to oxidation and chemical attack. This resistance is particularly valuable in industrial environments where coatings are exposed to corrosive substances and harsh weather conditions. The ability of lignin to withstand such challenges without losing integrity ensures long-term protection of the underlying material.

The multi-functionality of lignin, acting as both a friction reducer and an adhesion promoter, makes it an excellent candidate for anti-wear coatings.

3.3 Challenges and limitations

Lignin-based coatings are increasingly recognised as sustainable alternatives to conventional wear and abrasion-resistant coatings, offering eco-friendly benefits due to their natural abundance and biodegradability. However, several challenges and limitations hinder their widespread application in extreme wear conditions.

One of the primary disadvantages of lignin-based coating is its relatively lower mechanical strength compared with traditional additives such as SiO2 or cellulose nanocrystals. This inherent weakness restricts its performance under extreme wear and abrasion scenarios, making it less favourable for highly durable applications.

Furthermore, the complex nature of lignin causes challenges in achieving consistent production quality. Depending on the source and extraction method, its variability complicates the standardisation of lignin-based products, impacting the reproducibility and reliability of the final coating properties.

Additionally, the natural dark colour of lignin is a considerable limitation for applications where transparency is required. This characteristic limits its application in coatings that demand specific visual properties.

4 Lignin-based wear and corrosion resistance coating

In addition to lignin-based coating focusing on one aspect of wear or corrosion resistance performance, a few articles that reported lignin-based coatings with both wear and corrosion resistance functions are discussed in this section.

For example, Wang et al. (2024) chemically grafted organosolv lignin to polyurethane and improved the corrosion resistance of lignin PU on carbon steel. The lignin PU coating showed improved barrier properties compared to non-lignin grafted PU coating, hindering the electrolyte penetration into the coating. After 7 days of immersion in 1 mol/L NaCl solution, the EIS spectra showed that the coating with 15 wt% remained at 106 Ω cm2 and still had satisfactory corrosion resistance. In addition, the wear resistance of Wang et al.’s coating was evaluated by reciprocating tribology test, nanoindentation and nano scratch test. Incorporating lignin at optimal concentration significantly improved the coating’s wear resistance, and the friction coefficient for the coating was 0.15. This was attributed to forming a more compact and crosslinked coating structure, effectively reducing the scratch depth and enhancing the coating’s durability.

Similarly, Chen et al. (2023a) formulated a lignin-based polyurethane coating by integrating a small quantity of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as a dewetting agent with biomass-derived lignin. The coating showed substantial resistance to various liquids, ensuring liquids slid off without residues. The abrasion resistance of the polyurethane coating was evaluated using a weight cotton fabric abrasion experiment. The coating was applied to diverse substrates like steel and plank. After 2,000 abrasion cycles, the anti-ink ability of the coating was still satisfactory.

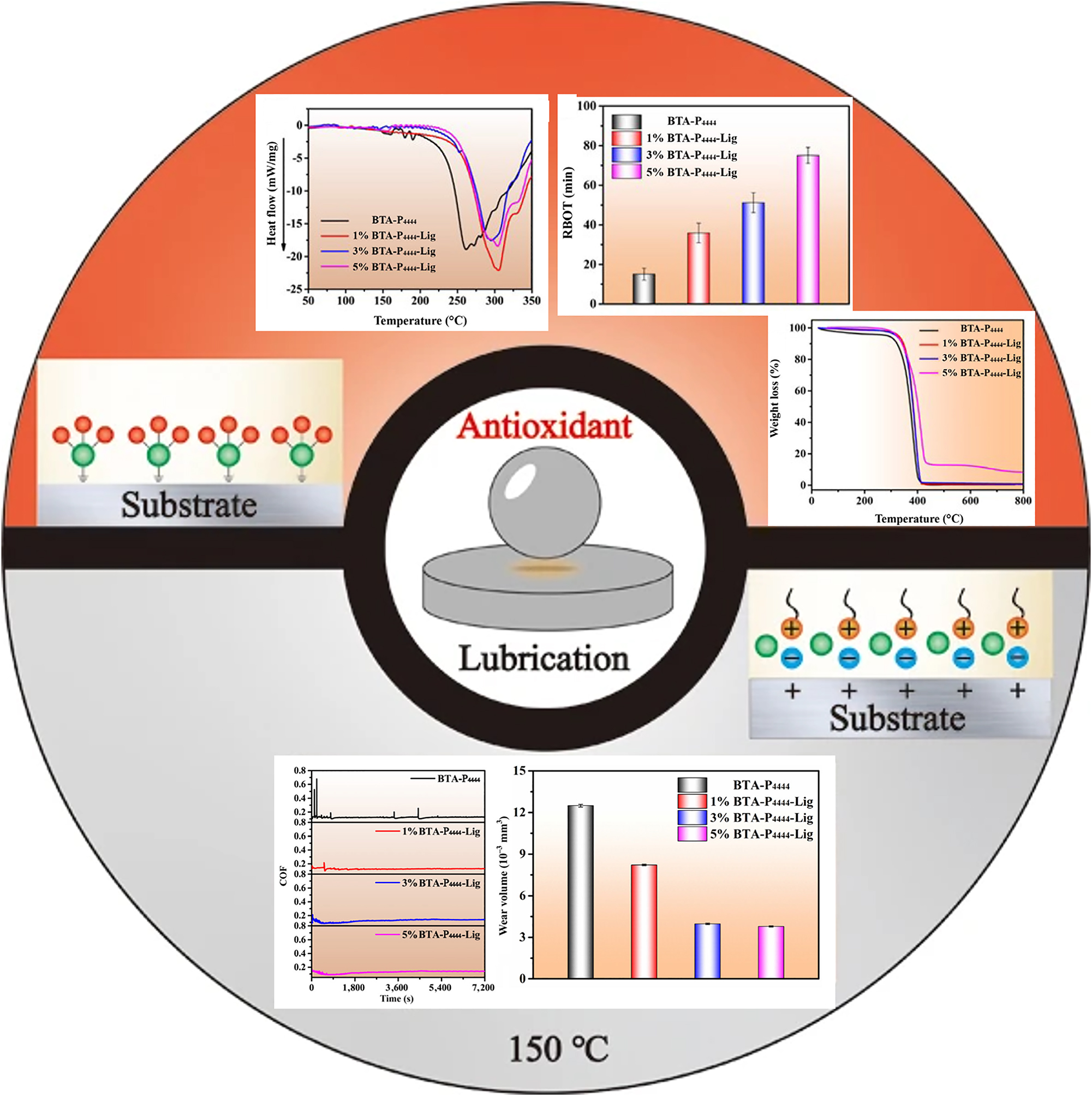

Differing from polymer coating, Zhang et al. (2023a) used kraft lignin, tetrabutylphosphorus hydroxide and benzotriazole to synthesise an ionic liquid (BTA-P4444-Lig IL) and utilised it as a water-based lubricating additive. The active elements N and P in the lubricating material formed a reaction film and reacted with the metal substrate. The reaction film blocked direct contact between the friction pairs and reduced friction and wear. Yu et al. (2022) also detailedly analysed the interactions between BTA-P4444-Lig ionic liquid and steel. The tribology performance for the lignin ionic liquid added water was evaluated on a reciprocating tester optimal SRV-Ⅳ, and both contact parts were AISI 52100 steel. After adding lignin, the friction coefficient for BTA-P4444-Lig was reduced to 0.146, and the wear volume was reduced by 4.6 times compared to the BTA-P4444 lubricant. It was speculated that large lignin biomacromolecules break into small molecules during the friction process, and the small lignin molecules could fill the grooves on the surface of the friction pair, thus effectively decreasing wear. In addition, the IL-added water lubricant showed good corrosion resistance, and the corrosion current decreased by one order of magnitude compared to water (Figure 7).

The tribological properties, corrosion resistance and anti-oxidation properties of BTA-P4444-Lig lubricant. From Ref (Zhang et al. 2023a), used under Creative Commons CC BY license.

The mechanisms by which lignin improves wear and corrosion resistance in coatings can be summarised as follows: the compact and crosslinked structure caused by lignin, which could improve the hardness and barrier properties of the coating; the formation of surface protection films by lignin fills surface grooves, which reduce the wear volume and corrosion current.

The current research focusing on developing coatings that simultaneously offer wear and corrosion resistance remains relatively limited. This scarcity may stem from the inherently interdisciplinary nature of the research topic. However, researchers have started to explore the use of lignin to enhance the sustainability of wear and corrosion-resistant coatings. This indicates a growing interest in integrating environmentally friendly materials into protective coatings. Further interdisciplinary collaboration and comprehensive studies are essential to advance the development of coatings that can robustly withstand wear and corrosion, extending the functional lifespan of materials in various industrial applications.

5 Potential research directions and future applications

Considering lignin’s complexity and compatibility, it is essential to develop straightforward and standardised methodologies for its synthesis into polymers. To fully harness lignin’s inherent potential as a sustainable and versatile material in producing corrosion and wear-resistant coatings, research may focus on several key areas that could advance and open up new applications.

Firstly, enhancing the adhesion and uniformity of lignin-based coatings on target substrates is crucial. This involves improving lignin coatings’ application processes that enhance the interaction between the lignin polymer and substrate. Techniques such as surface pre-treatment and coupling agents could be explored to achieve coatings with superior interface mechanical properties. Spraying, dipping and brush-on techniques, coupled with controlled curing processes synergy with optimal material design, could help achieve coatings with consistent quality and performance across different substrates.

Secondly, modifying lignin to improve its compatibility with other monomers is another promising research direction. By introducing tailored functional groups into the lignin, it can interact more effectively with different matrices, thereby enhancing the overall performance of the composite coating. Such modifications could improve the coating’s hardness, adhesive ability, durability, barrier properties and wear resistance, possibly introducing self-healing capabilities.

The application of lignin as the functional additive in combination with other hardeners and resins is also worth investigating. The synergy between lignin and other additives and matrix materials could result in coatings with enhanced protective qualities, such as increased resistance to chemical attacks, UV radiation and thermal degradation. Meanwhile, the development of bio-based hardeners that work compatibly with lignin could also contribute to the sustainability of the coatings.

Moreover, the potential applications of lignin-based corrosion and wear-resistant coatings could be vast and varied. For example, in the marine industry, lignin-based coatings could protect ships and offshore facilities from harsh corrosive conditions and biofouling. In the automotive sector, lignin-based coatings could enhance the durability and lifespan of vehicles by providing resistance against corrosion and wear. The construction industry could also benefit from lignin-based coatings by using them to protect buildings and infrastructure from environmental degradation.

6 Conclusions

In this review, we have explored the advancements in research about lignin-based coatings with a focus on corrosion and wear resistance since 2020. Various studies have thoroughly confirmed the potential of lignin as a viable corrosion inhibitor and an additive of anti-corrosion coatings. Lignin in wear resistance coating also brings functionality. Furthermore, incorporating lignin into wear resistance coatings imbues them with additional functional properties without reducing their durability, showcasing lignin’s versatility as a bio-based material.

Drawing on the inherent characteristics of lignin, including its natural abundance, biodegradability and unique chemical structure, which make it an attractive candidate for sustainable coating applications, we outline potential research objectives that could further utilise lignin’s inherent properties. These directions include improving lignin coating’s adhesion with substrate materials, optimising lignin’s integration into coatings to enhance performance and exploring bio-based solvents for lignin dispersion.

This review underscores the significance of lignin as a multifunctional material in developing eco-friendly, efficient and durable coatings, setting the stage for future innovations in this field.

Funding source: Vetenskapsrådet

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2019–04941

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2023–04962

Funding source: Svenska Forskningsrådet Formas

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2019–00904

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2022–01047

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2022–01988

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The authors thank the Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (Formas, Project nos. 2019–00904, 2022–01988 and 2022–01047), the Swedish Research Council (Project nos. 2019–04941 and 2023–04962).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Abdelrahman, N.S., Galiwango, E., Al-Marzouqi, A.H., and Mahmoud, E. (2022). Sodium lignosulfonate: a renewable corrosion inhibitor extracted from lignocellulosic waste. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14: 7531–7541, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-022-02902-6.Search in Google Scholar

Bajwa, D.S., Pourhashem, G., Ullah, A.H., and Bajwa, S.G. (2019). A concise review of current lignin production, applications, products and their environmental impact. Ind. Crops Prod. 139: 111526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111526.Search in Google Scholar

Bang, J., Kim, J., Kim, Y., Oh, J.K., Yeo, H., and Kwak, H.W. (2022). Preparation and characterization of hydrophobic coatings from carnauba wax/lignin blends. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 50: 149–158, https://doi.org/10.5658/wood.2022.50.3.149.Search in Google Scholar

Baysal, G. (2024). Sustainable polylactic acid spunlace nonwoven fabrics with lignin/zinc oxide/water-based polyurethane composite coatings. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 254: 127678, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127678.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Calvo-Flores, F.G. and Dobado, J.A. (2010). Lignin as renewable raw material. ChemSusChem 3: 1227–1235, https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201000157.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Cao, L., Yu, I.K.M., Liu, Y., Ruan, X., Tsang, D.C.W., Hunt, A.J., Ok, Y.S., Song, H., and Zhang, S. (2018). Lignin valorization for the production of renewable chemicals: state-of-the-art review and future prospects. Bioresour. Technol. 269: 465–475, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2018.08.065.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Cao, Y., Liu, Z., Zheng, B., Ou, R., Fan, Q., Li, L., Guo, C., Liu, T., and Wang, Q. (2020). Synthesis of lignin-based polyols via thiol-ene chemistry for high-performance polyurethane anticorrosive coating. Composites, Part B: Eng. 200: 108295, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108295.Search in Google Scholar

Cao, Y., Zheng, D., and Lin, C. (2021). Construction of ecofriendly anticorrosive composite film ZnAl-LDH by modification of lignin on AA 7075 surface. Mater. Corros. 72: 1595–1606, https://doi.org/10.1002/maco.202112402.Search in Google Scholar

Carlos de Haro, J., Magagnin, L., Turri, S., and Griffini, G. (2019). Lignin-based anticorrosion coatings for the protection of aluminum surfaces. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7: 6213–6222, https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b06568.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, J., Yang, H., Qian, Y., Ouyang, X., Yang, D., Pang, Y., Lei, L., and Qiu, X. (2023a). Translucent lignin-based omniphobic polyurethane coating with antismudge and UV-blocking dual functionalities. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11: 2613–2622, https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c06907.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, W., Xu, E., Zhao, Z., Wu, C., Zhai, Y., Liu, X., Jia, J., Lou, R., Li, X., Yang, W., et al.. (2023b). Study on mechanical and tribological behaviors of GQDs @ Si3N4 composite ceramics. Tribol. Int. 179: 108095, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2022.108095.Search in Google Scholar

da Cruz, M.G.A., Gueret, R., Chen, J., Piątek, J., Beele, B., Sipponen, M.H., Frauscher, M., Budnyk, S., Rodrigues, B.V.M., and Slabon, A. (2022). Electrochemical depolymerization of lignin in a biomass-based solvent. ChemSusChem 15: e202200718, https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.202201246.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Dastpak, A., Yliniemi, K., De Oliveira Monteiro, M.C., Höhn, S., Virtanen, S., Lundström, M., and Wilson, B.P. (2018). From waste to valuable resource: lignin as a sustainable anti-corrosion coating. Coatings 8: 454, https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8120454.Search in Google Scholar

Dastpak, A., Hannula, P.M., Lundström, M., and Wilson, B.P. (2020a). A sustainable two-layer lignin-anodized composite coating for the corrosion protection of high-strength low-alloy steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 148: 105866, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2020.105866.Search in Google Scholar

Dastpak, A., Lourenҫon, T.V., Balakshin, M., Farhan Hashmi, S., Lundström, M., and Wilson, B.P. (2020b). Solubility study of lignin in industrial organic solvents and investigation of electrochemical properties of spray-coated solutions. Ind. Crops Prod. 148: 112310, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112310.Search in Google Scholar

Dastpak, A., Ansell, P., Searle, J.R., Lundström, M., and Wilson, B.P. (2021). Biopolymeric anticorrosion coatings from cellulose nanofibrils and colloidal lignin particles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13: 41034–41045, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c08274.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Diógenes, O.B.F., De Oliveira, D.R., da Silva, L.R.R., Pereira, Í.G., Mazzetto, S.E., Araujo, W.S., and Lomonaco, D. (2021). Development of coal tar-free coatings: acetylated lignin as a bio-additive for anticorrosive and UV-blocking epoxy resins. Prog. Org. Coat. 161: 106533, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2021.106533.Search in Google Scholar

Diógenes, O.B.F., de Oliveira, D.R., da Silva, L.R.R., Linhares, B.G., Mazzetto, S.E., Lomonaco, D., and Araujo, W.S. (2023). Acetylated lignin as a biocomponent for epoxy coating. Anticorrosive performance analysis by accelerated corrosion tests. Surf. Coat. Technol. 474: 130116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2023.130116.Search in Google Scholar

El-Sheshtawy, H.S., Sofy, M.R., Ghareeb, D.A., Yacout, G.A., Eldemellawy, M.A., and Ibrahim, B.M. (2021). Eco-friendly polyurethane acrylate (PUA)/natural filler-based composite as an antifouling product for marine coating. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 105: 7023–7034, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-021-11501-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Faccini, M., Bautista, L., Soldi, L., Escobar, A.M., Altavilla, M., Calvet, M., Domènech, A., and Domínguez, E. (2021). Environmentally friendly anticorrosive polymeric coatings. Appl. Sci. 11: 3446, https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083446.Search in Google Scholar

Gao, C., Zhao, X., Liu, K., Dong, X., Wang, S., and Kong, F. (2020). Construction of eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor lignin derivative with excellent corrosion-resistant behavior in hydrochloric acid solution. Mater. Corros. 71: 1903–1912, https://doi.org/10.1002/maco.202011799.Search in Google Scholar

Gao, C., Zhao, X., Fatehi, P., Dong, X., Liu, K., Chen, S., Wang, S., and Kong, F. (2021). Lignin copolymers as corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel. Ind. Crops Prod. 168: 113585, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113585.Search in Google Scholar

Grabber, J.H. (2005). How do lignin composition, structure, and cross-linking affect degradability? A review of cell wall model studies. Crop Sci. 45: 820–831, https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2004.0191.Search in Google Scholar

Gu, J.D. (2003). Microbiological deterioration and degradation of synthetic polymeric materials: recent research advances. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 52: 69–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0964-8305(02)00177-4.Search in Google Scholar

Henn, K.A., Forsman, N., Zou, T., and Österberg, M. (2021). Colloidal lignin particles and epoxies for bio-based, durable, and multiresistant nanostructured coatings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13: 34793–34806, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c06087.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Huang, J., Li, M., Ren, C., Huang, W., Miao, Y., Wu, Q., and Wang, S. (2023). Construction of HLNPs/Fe3O4 based superhydrophobic coating with excellent abrasion resistance, UV resistance, flame retardation and oil absorbency. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11: 109046, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2022.109046.Search in Google Scholar

Jedrzejczyk, M.A., Madelat, N., Wouters, B., Smeets, H., Wolters, M., Stepanova, S.A., Vangeel, T., Van Aelst, K., Van den Bosch, S., Van Aelst, J., et al.. (2022). Preparation of renewable thiol-yne “click” networks based on fractionated lignin for anticorrosive protective film applications. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 223: 2100461, https://doi.org/10.1002/macp.202100461.Search in Google Scholar

Jiang, Y.H., Zhang, Y.Q., Wang, Z.H., An, Q.D., Xiao, Z.Y., Xiao, L.P., and Zhai, S.R. (2022). Synergistic assembly of micro-islands by lignin and dopamine for superhydrophobic surface: preparative chemistry and oil/water separation performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10: 107777, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2022.107777.Search in Google Scholar

Kausar, A. (2018). Polymer coating technology for high performance applications: fundamentals and advances. J. Macromol. Sci., Part A 55: 440–448, https://doi.org/10.1080/10601325.2018.1453266.Search in Google Scholar

Koch, G. (2017) 1 – cost of corrosion. In: El-Sherik, A.M. (Ed.). Trends in oil and gas corrosion research and technologies. Woodhead Publishing, Boston.10.1016/B978-0-08-101105-8.00001-2Search in Google Scholar

Komartin, R.S., Balanuca, B., Necolau, M.I., Cojocaru, A., and Stan, R. (2021). Composite materials from renewable resources as sustainable corrosion protection coatings. Polymers 13: 3792, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13213792.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kulkarni, P., Ponnappa, C.B., Doshi, P., Rao, P., and Balaji, S. (2021). Lignin from termite frass: a sustainable source for anticorrosive applications. J. Appl. Electrochem. 51: 1491–1500, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10800-021-01592-8.Search in Google Scholar

Laxminarayan, T., Truncali, A., Rajagopalan, N., Weinell, C.E., Johansson, M., and Kiil, S. (2023). Chemically-resistant epoxy novolac coatings: effects of size-fractionated technical kraft lignin particles as a structure-reinforcing component. Prog. Org. Coat. 183: 107793, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2023.107793.Search in Google Scholar

Liao, B.K., Quan, R.X., Feng, P.X., Wang, H., Wang, W., and Niu, L. (2024). Carbon steel anticorrosion performance and mechanism of sodium lignosulfonate. Rare Met. 43: 356–365, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12598-023-02404-y.Search in Google Scholar

Ma, B., Xiong, F., Wang, H., Wen, M., Yang, J., Qing, Y., Chu, F., and Wu, Y. (2024). A gravity–inspired design for robust and photothermal superhydrophobic coating with dual–size lignin micro–nanospheres. J. Cleaner Prod. 435: 140506, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140506.Search in Google Scholar

Mhd Haniffa, M.A.C., Ching, Y.C., Abdullah, L.C., Poh, S.C., and Chuah, C.H. (2016). Review of bionanocomposite coating films and their applications. Polymers 8: 246, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym8070246.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Montemor, M.F. (2014). Functional and smart coatings for corrosion protection: a review of recent advances. Surf. Coat. Technol. 258: 17–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2014.06.031.Search in Google Scholar

Moreno, A., Liu, J., Gueret, R., Hadi, S.E., Bergström, L., Slabon, A., and Sipponen, M.H. (2021). Unravelling the hydration barrier of lignin oleate nanoparticles for acid- and base-catalyzed functionalization in dispersion state. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 60: 20897–20905, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202106743.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Motlatle, A.M., Ray, S.S., Ojijo, V., and Scriba, M.R. (2022). Polyester-based coatings for corrosion protection. Polymers 14: 3413, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14163413.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Nasrun, Z., Osman, L.S., Latif, N.H.A., Elias, N.H.H., Saidin, M., Shahidan, S., Abdullah, S.H.A., Ali, N.A., Rusli, S.S.M., Ibrahim, M.N.M., et al.. (2023). Conversion of archeological iron rust employing coconut husk lignin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 253: 126786, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126786.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Osman, L.S., Hamidon, T.S., Latif, N.H.A., Elias, N.H.H., Saidin, M., Shahidan, S., Abdullah, S.H.A., Ali, N.A., Rusli, S.S.M., Ibrahim, M.N.M., et al.. (2023). Rust conversion of archeological cannonball from Fort Cornwallis using oil palm frond lignin. Ind. Crops Prod. 192: 116107, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.116107.Search in Google Scholar

Patil, R., Jadhav, L., Borane, N., Mishra, S., Patil, S.V., and Patil, V. (2023a). Industrial waste lignosulphonate to functionalized azo pigments: an application to epoxy-polyamine composite coating. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14: 21069–21083, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04226-5.Search in Google Scholar

Patil, R., Jadhav, L., Borane, N., Mishra, S., and Patil, V. (2023b). Nano-dispersible azo pigments from lignin: a new synthetic approach and epoxy-polyamine composite coating. Pigm. Resin Technol. 52: 400–412, https://doi.org/10.1108/prt-09-2021-0109.Search in Google Scholar

Qian, Y., Zhou, Y., Li, L., Liu, W., Yang, D., and Qiu, X. (2020). Facile preparation of active lignin capsules for developing self-healing and UV-blocking polyurea coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 138: 105354, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.105354.Search in Google Scholar

Rasool, G., Pelaez Larios, M., and Stack, M. (2020). Impact angle and exposure time effects on raindrop erosion of fibre reinforced polymer composites: application to offshore wind turbine conditions. Tribol. Trans. 16.Search in Google Scholar

Ren, C., Li, M., Huang, W., Zhang, Y., and Huang, J. (2022). Superhydrophobic coating with excellent robustness and UV resistance fabricated using hydrothermal treated lignin nanoparticles by one-step spray. J. Mater. Sci. 57: 18356–18369, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-022-07787-4.Search in Google Scholar

Sadat-Shojai, M. and Ershad-Langroudi, A. (2009). Polymeric coatings for protection of historic monuments: opportunities and challenges. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 112: 2535–2551, https://doi.org/10.1002/app.29801.Search in Google Scholar

Shan, Z., Jia, X., Bai, Y., Yang, J., Su, Y., and Song, H. (2023a). Highly wear-resistant and recyclable paper-based self-lubricating material based on lignin-cellulose-graphene layered interwoven structure. J. Cleaner Prod. 418: 138117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138117.Search in Google Scholar

Shan, Z., Jia, X., Tian, R., Yang, J., Wang, S., Li, Y., Shao, D., Feng, L., and Song, H. (2023b). Sustainable, recyclable, and highly wear-resistant wood matrix as a new paper-based friction material. Cellulose 30: 6601–6619, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-023-05292-8.Search in Google Scholar

Shan, Z., Jia, X., Yang, J., Su, Y., and Song, H. (2023c). Polydopamine coating grown on the surface of fluorinated polymer to enhance the self-lubricating properties of lignin-cellulose based composites. Prog. Org. Coat. 183: 107778, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2023.107778.Search in Google Scholar

Song, X., Tang, S., Chi, X., Han, G., Bai, L., Shi, S.Q., Zhu, Z., and Cheng, W. (2022). Valorization of lignin from biorefinery: colloidal lignin micro-nanospheres as multifunctional bio-based fillers for waterborne wood coating enhancement. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10: 11655–11665, https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c03590.Search in Google Scholar

Tan, Z., Wang, S., Hu, Z., Chen, W., Qu, Z., Xu, C., Zhang, Q., Wu, K., Shi, J., and Lu, M. (2020). pH-responsive self-healing anticorrosion coating based on a lignin microsphere encapsulating inhibitor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59: 2657–2666, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.9b05743.Search in Google Scholar

Tao, Y., Ma, F., Teng, M., Jia, Z., and Zeng, Z. (2019). Designed fabrication of super high hardness Ni-B-Sc nanocomposite coating for anti-wear application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 492: 426–434, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.06.233.Search in Google Scholar

Thakur, V.K. (Ed.) (2013). Green composites from natural resources. CRC Press, Boca Raton.10.1201/b16076Search in Google Scholar

Tharanathan, R.N. (2003). Biodegradable films and composite coatings: past, present and future. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 14: 71–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-2244(02)00280-7.Search in Google Scholar

Tian, H., Tang, Z., Zhuang, X., Chen, X., and Jing, X. (2012). Biodegradable synthetic polymers: preparation, functionalization and biomedical application. Prog. Polym. Sci. 37: 237–280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.06.004.Search in Google Scholar

Ulaeto, S.B., Ravi, R.P., Udoh, I.I., Mathew, G.M., and Rajan, T.P.D. (2023). Polymer-based coating for steel protection, highlighting metal-organic framework as functional actives: a review. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 4: 284–316, https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd4020015.Search in Google Scholar

Vanholme, R., Morreel, K., Ralph, J., and Boerjan, W. (2008). Lignin engineering. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11: 278–285, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Verma, S., Mohanty, S., and Nayak, S.K. (2019). A review on protective polymeric coatings for marine applications. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 16: 307–338, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11998-018-00174-2.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, J., Seidi, F., Huang, Y., and Xiao, H. (2022a). Smart lignin-based polyurethane conjugated with corrosion inhibitor as bio-based anticorrosive sublayer coating. Ind. Crops Prod. 188: 115719, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115719.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, X., Leng, W., Nayanathara, R.M.O., Caldona, E.B., Liu, L., Chen, L., Advincula, R.C., Zhang, Z., and Zhang, X. (2022b). Anticorrosive epoxy coatings from direct epoxidation of bioethanol fractionated lignin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 221: 268–277, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.08.177.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Wang, D., Zhao, J., Zhang, F., Claesson, P., Pan, J., and Shi, Y. (2023a). In-situ coating wear condition monitoring based on solid-liquid triboelectric nanogenerator and its mechanism study. Nano Energy 112: 108479, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2023.108479.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, L., Zhang, J., Wang, F., Liu, Z., Su, W., Chen, Z., and Jiang, J. (2023b). Investigation on the effects of polyaniline/lignin composites on the performance of waterborne polyurethane coating for protecting cement-based materials. J. Build. Eng. 64: 105665, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105665.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, D., Zhao, J., Claesson, P., Christakopoulos, P., Rova, U., Matsakas, L., Ytreberg, E., Granhag, L., Zhang, F., Pan, J., et al.. (2024). A strong enhancement of corrosion and wear resistance of polyurethane-based coating by chemically grafting of organosolv lignin. Mater. Today Chem. 35: 101833, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtchem.2023.101833.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, L., Liu, S., Wang, Q., Wang, Y., Ji, X., Yang, G., Chen, J., Li, C., and Fatehi, P. (2022a). High strength and multifunctional polyurethane film incorporated with lignin nanoparticles. Ind. Crops Prod. 177: 114526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.114526.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, T., Li, X., Ma, X., Ye, J., Shen, L., and Tan, W. (2022b). Modification of lignin by hexamethylene diisocyanate to synthesize lignin-based polyurethane as an organic polymer for marine polyurethane anticorrosive coatings. Mater. Res. Express 9: 105302, https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ac95fc.Search in Google Scholar

Xie, C., Guo, H., Zhao, W., and Zhang, L. (2020). Environmentally friendly marine antifouling coating based on a synergistic strategy. Langmuir 36: 2396–2402, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b03764.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Yang, C., Zhu, Y., Wang, T., Wang, X., and Wang, Y. (2024a). Research progress of metal organic framework materials in anti-corrosion coating. J. Polym. Eng. 44: 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1515/polyeng-2023-0144.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, K., Niu, Y., Wang, X., Du, S., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., and Cai, J. (2024b). Self-lubricating epoxy composite coating with linseed oil microcapsule self-healing functionality. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 141: e54927, https://doi.org/10.1002/app.54927.Search in Google Scholar

Yu, Q., Yang, Z., Huang, Q., Lv, H., Zhou, K., Yan, X., Wang, X., Yang, W., Zhou, C., Yu, B., et al.. (2022). Lignin composite ionic liquid lubricating material as a water-based lubricating fluid additive with excellent lubricating, anti-wear and anti-corrosion properties. Tribol. Int. 174: 107742, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2022.107742.Search in Google Scholar

Zakzeski, J., Bruijnincx, P.C.A., Jongerius, A.L., and Weckhuysen, B.M. (2010). The catalytic valorization of lignin for the production of renewable chemicals. Chem. Rev. 110: 3552–3599, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr900354u.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Zhang, J., Huang, Y., Wu, H., Geng, S., and Wang, F. (2021). Corrosion protection properties of an environmentally friendly polyvinyl alcohol coating reinforced by a heating treatment and lignin nanocellulose. Prog. Org. Coat. 155: 106224, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2021.106224.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, J., Cao, D., Wang, S., Feng, X., Zhu, J., Lu, X., and Mu, L. (2022). Valorization of industrial lignin as lubricating additives by C–C bond cleavage and doping heteroelement-rich groups. Biomass Bioenergy 161: 106470, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2022.106470.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, C., Yang, Z., Huang, Q., Wang, X., Yang, W., Zhou, C., Yu, B., Yu, Q., Cai, M., and Zhou, F. (2023a). Lignin composite ionic liquid lubricants with excellent anti-corrosion, anti-oxidation, and tribological properties. Friction 11: 1239–1252, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40544-022-0657-y.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Z., Ren, C., Sun, Y., Miao, Y., Deng, L., Wang, Z., Cao, Y., Zhang, W., and Huang, J. (2023b). Construction of CNC@SiO2@PL based superhydrophobic wood with excellent abrasion resistance based on nanoindentation analysis and good UV resistance. Polymers 15: 933, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15040933.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston