Abstract

This study investigated the impact of different deformations on the corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel in an industrial environment simulation solution using various electrochemical, electron backscatter diffraction analysis, and surface analysis methods. Electrochemical results show that under small deformation conditions (10 %), the corrosion current of S32304 duplex stainless steel decreases due to the coupling effect of the austenite phase with increased potential and the ferrite phase with decreased potential. However, due to the increased potential difference between the austenite and ferrite phases, the pitting corrosion resistance of the material decreases. Under large deformation conditions, the corrosion current of S32304 duplex stainless steel continuously increases but still remains lower than the corrosion current under undeformed conditions. The pitting potential of duplex stainless steel first decreases and then increases. When the deformation reaches 70 %, high-angle grain boundaries are formed in the austenite phase, leading to a sharp decrease in potential. The potential of austenite begins to be lower than that of ferrite, and the preferentially corroded phase changes from ferrite to austenite. The experimental results found that deformation does not affect the semiconductor properties of the passivation film of S32304 duplex stainless steel. The main components of its passivation film include iron oxides (FeO and Fe2O3) and chromium oxides (Cr2O3 and Cr(OH)3).

1 Introduction

Duplex stainless steel (DSS) was discovered “accidentally” in 1927 and saw rapid development between 1929 and 1930 (Brandi and Schön 2017; Nilsson 1992). In 2000, super duplex stainless steel UNS S32707 and UNS S33207 were introduced (Sims 2013; Zhao et al. 2022a). Since then, DSS has continued to evolve. Economic duplex stainless steels consist of roughly equal proportions of austenitic and ferritic phases, providing high strength and excellent corrosion resistance (Chen et al. 2022; Leygraf et al. 2004; Li et al. 2022; Liu et al. 2023; Silva et al. 2022; Xu et al. 2021). They can partially replace AISI 300 series austenitic stainless steels and are widely used in industries such as petrochemicals, paper manufacturing, shipbuilding, and other corrosive environments (Liu et al. 2023; Zhou et al. 2024).

Cold deformation is crucial in manufacturing DSS components, especially in areas like corners and edges where various levels of cold deformation are tolerated (Abreu et al. 2004; Burstein et al. 2004; Gholami et al. 2015; Jia et al. 2021; Liang et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2024a; Zhang et al. 2021). DSS typically exhibits a dual-phase structure comprising hard and soft phases. In nitrogen-containing DSS, austenite is typically the hard phase, while other grades of DSS may have hard ferritic phases (Nilsson 1992; Sharafi 2009; Zhang et al. 2022). During plastic deformation, strain distribution among phases varies based on their relative plasticity. This process involves complex microstructural evolution and deformation mechanisms, such as grain rotation, dislocation slip, deformation twinning (DTs), and/or strain-induced martensite (SIM), all of which can contribute to localized corrosion of cold-rolled stainless steel (Jia et al. 2021; Luo et al. 2017; Martin et al. 2013). Moreover, this process can influence microstructural changes, transitioning from deformation twinning to slip and shear bands, and from strain-induced martensite to the development of dislocation substructures (Kim et al. 2019). Studies have demonstrated that austenitic stainless steels undergo mechanical twinning and martensitic transformation after cold deformation (Shakhova et al. 2012). Experimental observations on strain distribution and microstructural evolution in DSS have naturally garnered research interest. Low-alloy DSS grades such as SAF 2101 and S31803 are prone to severe cold deformation-induced pitting corrosion (Breda et al. 2015; Luo et al. 2017; Yin et al. 2019b). Lebedev et al. provided that SIM and residual stresses act as active anodic sites, degrading the passive film on cold-rolled surfaces, providing an explanation for this phenomenon (Lebedev and Kosarchuk 2000). Additionally, Alvarez et al. emphasized the selective anodic corrosion of martensite in UNS S30403 and S31603, which is contingent upon its content and distribution (Alvarez et al. 2013). Breda et al. suggested that high-alloy DSS like SAF 2205 and 2,507 maintain their corrosion resistance even after cold deformation, attributing this to the stability of the passive film and microstructure (Breda et al. 2015). Mudali et al. discovered that cold deformation up to 20 % can enhance resistance to pitting corrosion (Poonguzhali et al. 2013). However, beyond this threshold, detrimental effects emerge due to increased deformation bands and negative impacts on the shear SRO (stacking fault-rich austenite) region, aligning with findings by Hamdy et al. (Hamdy et al. 2006). Moreover, while stainless steel generally demonstrates superior passivation ability compared to carbon steel, cold deformation adversely affects its corrosion resistance (Luo et al. 2017). In lean and standard DSS, the corrosion performance tends to deteriorate as plastic strain increases. Conversely, higher grades of DSS, such as super duplex stainless steels, are generally considered less sensitive to applied plastic strain, although this sensitivity may vary depending on the specific environmental conditions (Shen et al. 2023; Yang et al. 2013; Yin et al. 2019a). The effect of cold deformation on the corrosion of DSS has sparked conflicting reports in the literature. While some studies suggest that cold deformation can exacerbate pitting in chloride solutions, others propose that mild levels of cold deformation could actually be beneficial for enhancing resistance to pitting (Shen et al. 2023; Yin et al. 2019a). However, there’s a notable gap in the research regarding the impact of cold deformation on the corrosion behavior of duplex stainless steels in simulated industrial environment solutions.

This study utilized S32304 duplex stainless steel subjected to cold deformation treatment and employed a range of analytical techniques, including electrochemical methods, electron backscatter diffraction analysis, and surface analysis, to probe the impact of deformation on the corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel. Electrochemical characterization was employed to assess both the general corrosion behavior and the localized corrosion tendencies of the individual phases within the material. The investigation delved into the interplay between the overall corrosion performance and the microstructural changes occurring within the constituent phases, shedding light on their varying corrosion resistance properties.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Specimens and surface preparation

The study employed S32304 duplex stainless steel with a 1 mm thickness as the base material. The mass fractions of the components in stainless steel are as follows: 23.36 % chromium (Cr), 3.64 % nickel (Ni), 1.52 % manganese (Mn), 0.57 % silicon (Si), 0.33 % copper (Cu), 0.157 % nitrogen (N), 0.15 % molybdenum (Mo), 0.026 % phosphorus (P), 0.017 % carbon (C), 0.001 % sulfur (S), with the remainder being iron (Fe). Before conducting the experiments, the stainless steel plates underwent an annealing process at 1,100 °C for 4 h, followed by quenching in water.

The duplex stainless steel plates underwent cold deformation in a single direction by passing them between working rolls to gradually reduce their thickness through successive passes. The plates were cold rolled to achieve reductions of 10 %, 30 %, 50 %, 70 %, and 90 % in thickness. Subsequently, the samples were cut into dimensions of 10 mm × 12 mm, ensuring that the surfaces were parallel to the rolling direction. Surface preparation involved sequential grinding using SiC paper with grit sizes ranging from 400 to 2000, followed by polishing with 0.1 μm diamond powders. Afterward, the samples were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water and alcohol, and finally dried before further analysis.

2.2 Material characterization

The electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) samples were prepared through a series of steps including mechanical grinding, polishing, and subsequent electropolishing. Electropolishing was carried out using an electrolyte mixture consisting of 15 % perchloric acid and 85 % ethanol by volume. This process helped to achieve a smooth and polished surface suitable for EBSD analysis. The raw EBSD data obtained from the samples were processed using Aztec Crystal software, enabling detailed analysis and interpretation of the crystallographic information contained within the microstructure of the material.

For X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis, the sample underwent electrochemical polishing to obtain the passive film. XPS analysis was conducted using the Thermo Escalab 250XI instrument, which features a beam diameter of 650 μm and operates at an operating voltage of 1.486 kV. Charge correction was achieved using the carbon contamination peak (C1s = 284.8 eV). High-resolution spectra were obtained for oxygen (O), iron (Fe), and chromium (Cr). The XPS data were analyzed using commercial XPSpeak software with Shirley background subtraction. The C1s peak from adventitious carbon at 284.8 eV was utilized as the calibration peak to correct for charging shifts, and all other peaks were calibrated using the C1s peak.

2.3 Electrochemical test

Electrochemical measurements were conducted using a VersaSTAT 3F with a conventional three-electrode cell system. A saturated calomel electrode (SCE) served as the reference electrode, while the sample and a platinum sheet were chosen as the working and counter electrodes, respectively. Initially, the specimens underwent a constant potential of −1.1 VSCE for 60 s to eliminate the oxide layer formed in air. Subsequently, the open circuit potential (OCP) was monitored for 60 min to ensure the stability of the test system. Finally, dynamic polarization curves were generated at a scanning rate of 0.5 mV/s, with the scanning range spanning from −0.8 to −1.3 VSCE. Corrosion current density values (i corr ) were determined using the Tafel region extrapolation method.

For capacitance measurements, Mott–Schottky plots were scanned at a frequency of 1,000 Hz within a potential range from −1,000 to 1,000 mV SCE, employing a perturbation voltage of 10 mV. The scan rate was set at 36 mV/steps to prevent any alterations in the passive film. The test solutions utilized throughout all experiments were simulated industrial environment solutions, consisting of 0.01 mol/L NaHSO3 with 3.5 wt% NaCl. Following the protocol outlined by Burstein et al. (Burstein and Ilevbare 1996; Burstein and Vines 2001), experiments were repeated at least three times to ensure the reproducibility of the obtained results. All the above experiments were carried out at room temperature.

2.4 Immersion test

The initiation sites of pitting corrosion were pinpointed through a combination of immersion testing and EBSD analysis, following the methodology outlined in previous studies (Fu et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2024b). Immersion experiments were carried out using a simulated industrial environment solution. The immersion temperature was room temperature. After immersion for 24 h, the sample underwent thorough cleaning. Specific areas were then selected for detailed analysis. Finally, EBSD was utilized to examine the corrosion behavior within various microstructural regions, providing insights into the localized corrosion mechanisms at play.

3 Results

3.1 Characterization of microstructure

Figure 1 illustrates the phase diagrams of S32304 stainless steel under various deformation conditions (0 %, 10 %, 30 %, and 50 %), revealing a relatively uniform distribution of phases in the samples. In duplex stainless steels, the austenite phase acts as the secondary phase in the microstructure, and its deformation is constrained by the surrounding ferrite phase. Under moderate deformation conditions, the ferrite phase can effectively accommodate the deformed austenite grains.

The EBSD phase maps of S32304 duplex stainless steel depict varying degrees of cold deformation: (a) without deformation, (b) 10 % deformation, (c) 30 % deformation, and (d) 50 % deformation.

Following a 24-h immersion of the raw materials in a simulated industrial environment, an EDS surface scan image was acquired. Figure 2 displays both the SEM image and the EDS surface scan image of unaltered S32304 following a 24-h immersion in a simulated industrial environment. In the SEM image, raised areas appear gray, showcasing a concentration of nickel elements, indicative of the austenite phase. Conversely, recessed areas exhibit a grayish-white hue, highlighting a concentration of chromium elements, representing the ferrite phase. The austenite phase is distributed in an elongated, blocky, and irregular dendritic shape within the ferrite matrix, aligning with findings from previous literature (Saha et al. 2020).

The EDS surface scan image of undeformed S32304 duplex stainless steel after immersion in a simulated industrial environment solution for 24 h.

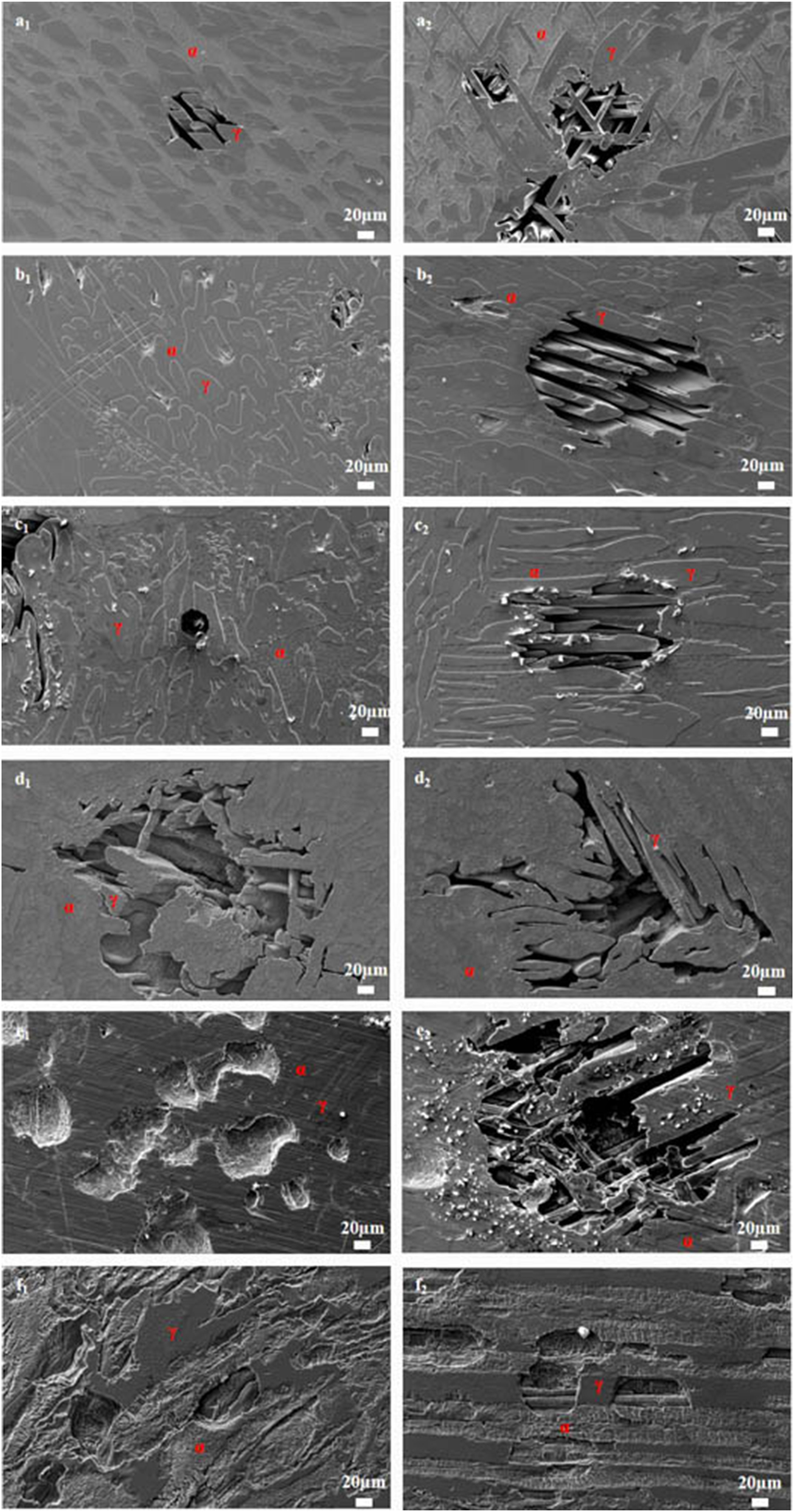

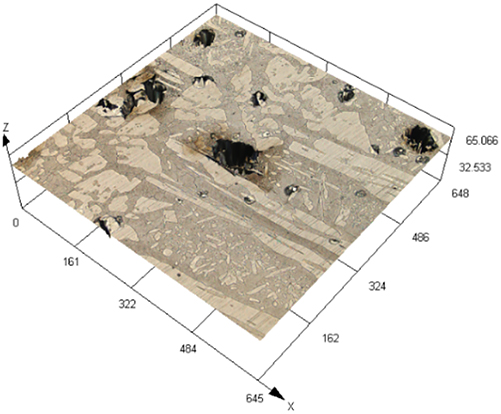

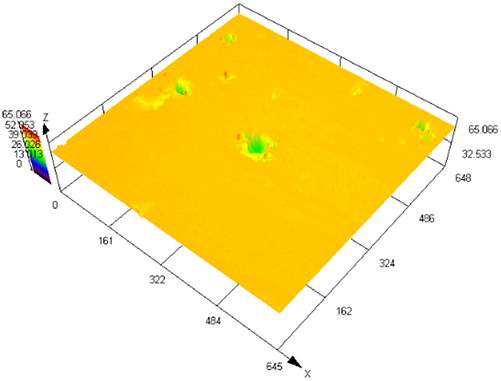

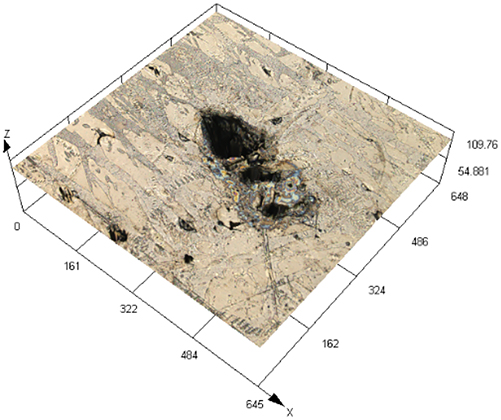

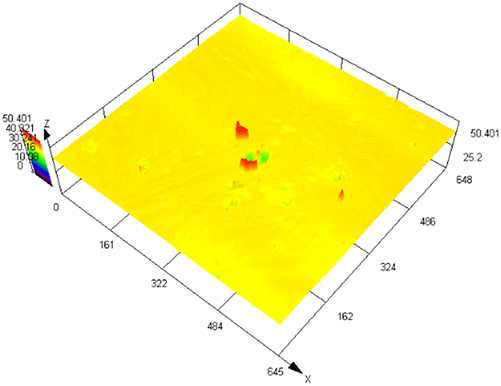

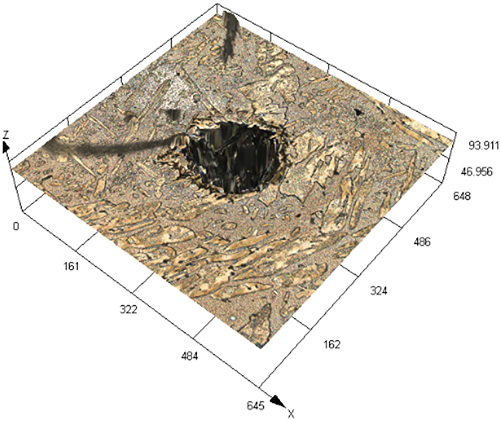

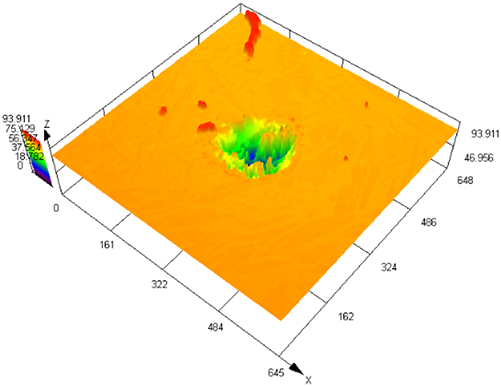

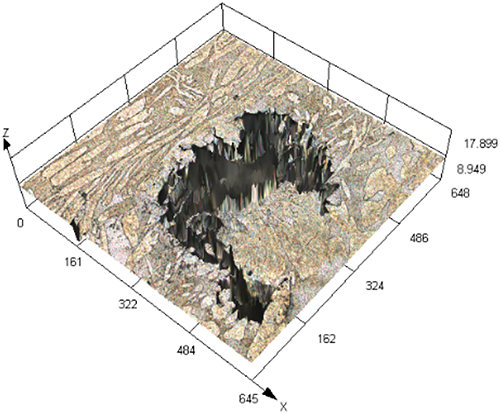

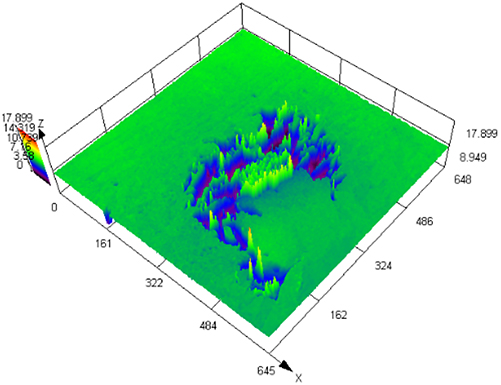

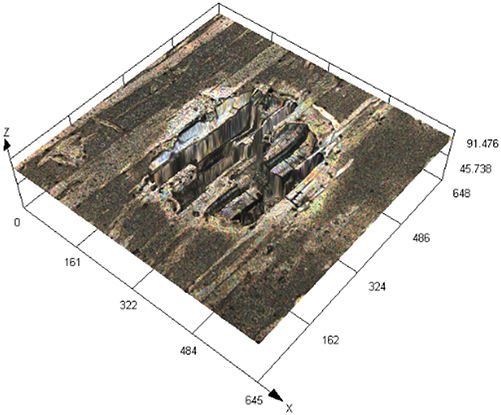

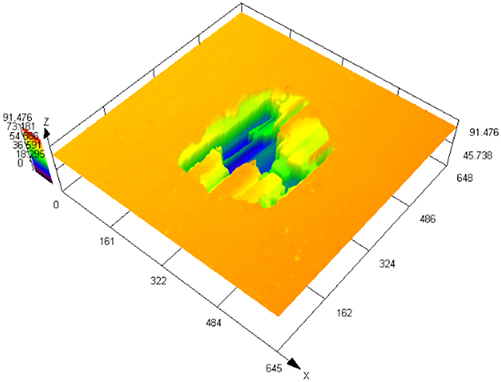

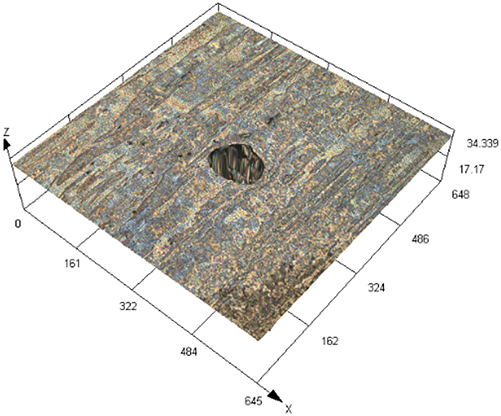

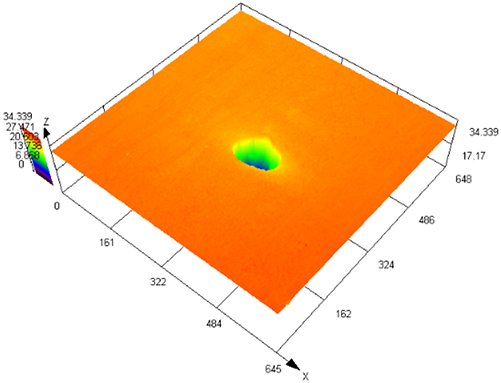

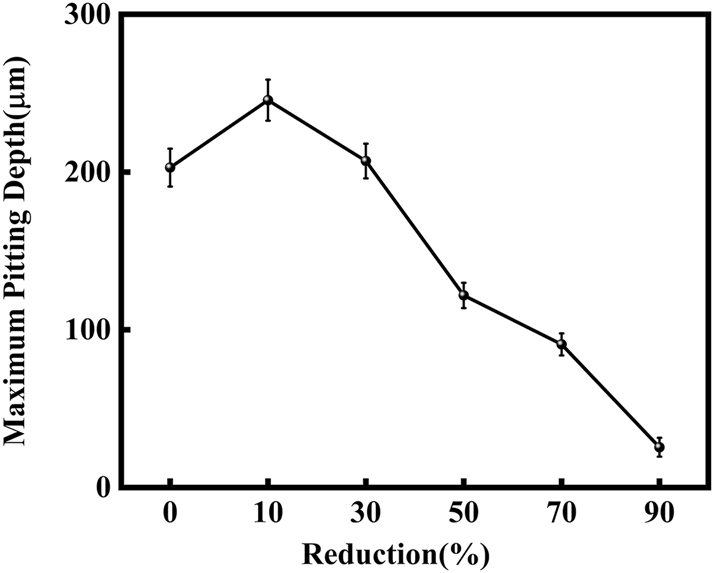

Figure 3 illustrates SEM images of S32304 duplex stainless steel subjected to various deformations after immersion in a simulated industrial environment solution for 24 h. Under the condition of 0 % deformation, as seen from Figure 3 (a1), austenite is regularly distributed in the ferrite matrix. In the middle corrosion area, it can be seen that ferrite is corroded while austenite shows a structure distributed in a pattern similar to a rhombus and is not corroded. In the lower right corner, slight pitting pits can also be observed in the austenite area. In Figure 3 (a2), the distribution of austenite is relatively disordered. In the middle corrosion area, it can also be observed that ferrite is preferentially corroded. And it is observed that the uncorroded austenite has a disordered orientation and intersects with each other. The orientations and morphologies of the two areas are different, but in both cases, the ferritic phase is preferentially corroded. At deformation rates of 10 %, 30 %, and 50 %, it can be seen that the corrosion morphologies of the same sample in different areas are different. This may be related to the orientation of the material. However, in the corrosion areas, it can be observed that ferrite is corroded away and austenite stands out. Some local phase boundary corrosion occurs, and the ferritic phase is also preferentially corroded. Of course, some slight pitting pits are observed to occur in the austenite area. Upon reaching a deformation of 70 %, significant corrosion pits emerge, with diameters ranging from 60 to 80 μm, spreading into the austenite region. Irregular prism-shaped pits also appear. This may be crystallographic pits, which have been reported in some papers (Shahryari et al. 2009; Tang and Aday 2024). The primary ferrite phase undergoes corrosion, with some observed on the austenite as well. When the deformation reaches 90 %, severe local corrosion appears on the surface. Austenite becomes the center of pit formation, indicating that the austenite phase is preferentially corroded. The surface morphology observed via laser confocal microscopy using OLYMPUS LEXT OLS 4100 yielded the following results, as summarized in Table 1. Under the condition of 0 % deformation, corrosion pits primarily formed in the ferrite phase, with a depth of 202.835 ± 12.122 μm. Under the deformation condition of 10 %, the observed maximum pitting pit further increases to 245.573 ± 13.222 μm. It may be that the ferrite is deformed and its Volta potential is increased, resulting in an increased potential difference between ferrite and austenite and enhanced galvanic corrosion. Under 30 % deformation, the maximum observed pit depth was 206.986 ± 11.114 μm, displaying a regular circular shape. Under the deformation condition of 50 %, the maximum pitting depth of 121.797 ± 8.154 μm is observed. Pitting develops into local corrosion, mainly developing along the ferrite area and presenting an irregular dendritic shape. With 70 % deformation, corrosion depth reduced to 90.754 ± 7.126 μm. Pitting pits can be seen to germinate from ferrite and spread in a circular shape. While ferrite is corroded, local austenite is also corroded. Under the deformation condition of 90 %, the maximum corrosion pit depth of 28.565 ± 6.142 μm can be observed. At the same time, it is observed that pitting has changed from germinating at ferrite to germinating at austenite, and austenite is preferentially corroded. The findings presented in Figure 4 demonstrate a notable trend in the variation of maximum pit depth concerning the deformation. Initially, there is an increase in the maximum pit depth, followed by a gradual decrease. This observation suggests a nuanced behavior in the pitting corrosion resistance of the material, characterized by an initial decrease followed by an increase. One potential explanation for this behavior lies in the distinct responses of the corrosion resistance exhibited by the two phases of the material in response to stress variation. Specifically, the corrosion resistance of ferrite exhibits a steady decrease with increasing stress, while the corrosion resistance of austenite shows an initial increase under low deformation conditions, followed by a sharp decline with higher degrees of deformation.

SEM image of S32304 with different cold deformation levels after immersion in a simulated industrial environment solution for 24 h: (a1–2) 0 %, (b1–2) 10 %, (c1–2) 30 %, (d1–2) 50 %, (e1–2) 70 %, and (f1–2) 90 % (α: ferrite phase, γ: austenite phase).

The laser confocal results of S32304 duplex stainless steel with different deformation levels after immersion in a simulated industrial environment solution for 24 h.

| Deformation | 3D topography | 3D height distribution map | Maximum pitting depth (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 % |

|

|

202.835 ± 12.122 |

| 10 % |

|

|

245.573 ± 13.222 |

| 30 % |

|

|

206.986 ± 11.114 |

| 50 % |

|

|

121.797 ± 8.154 |

| 70 % |

|

|

90.754 ± 7.126 |

| 90 % |

|

|

28.565 ± 6.142 |

Maximum pitting depth changes with different deformation after immersion in a simulated industrial environment solution for 24 h: (a) 10 %, (b) 30 %, (c) 50 %, (d) 70 %, and (e) 90 %.

The specific potential difference between the ferrite and austenite phases, typically ranging from 50–100 mV, plays a crucial role in this corrosion behavior (Mondal et al. 2019; Örnek and Engelberg 2015; Örnek et al. 2019). Electrochemical data indicate that in a 1 M H2SO4 environment, the dissolution potentials of austenite and ferrite are −281 mVSCE and −323 mVSCE, respectively (Mondal et al. 2019). This potential difference theoretically induces galvanic corrosion, accelerating the corrosion process in the ferritic phase (Tsai and Chen 2007). This dynamic interplay between stress, corrosion resistance, and potential difference contributes to the complex corrosion behavior observed.

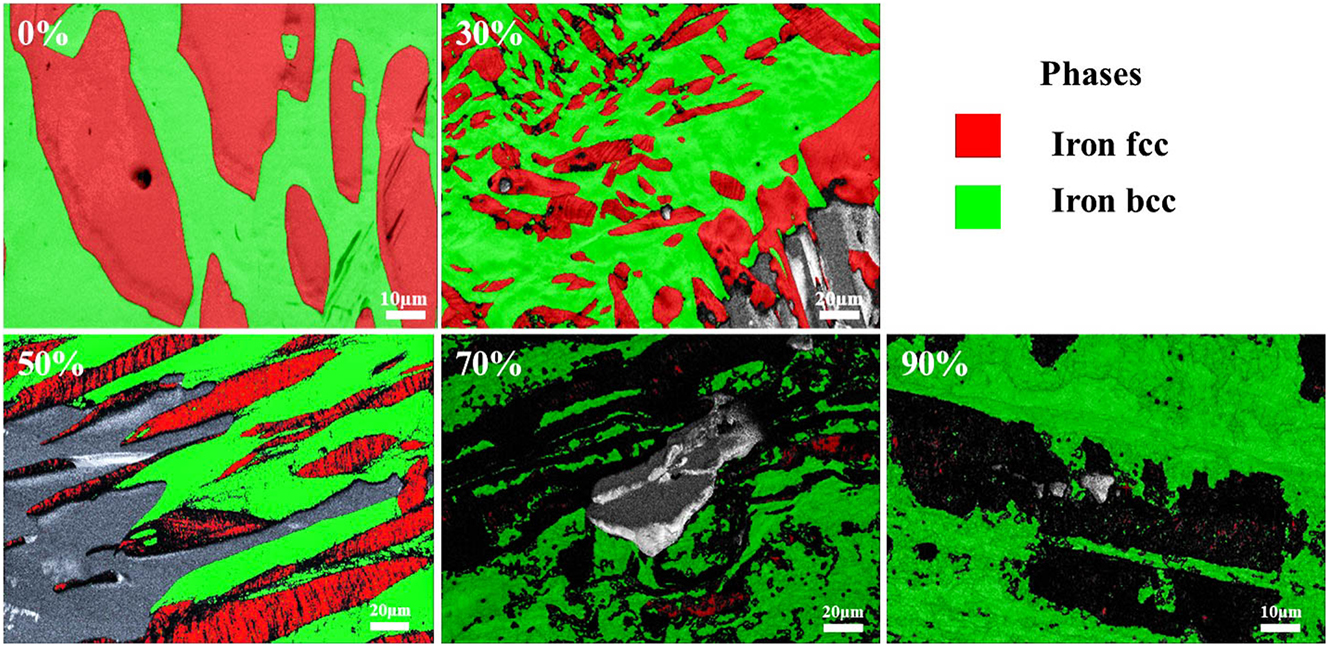

Figure 5 illustrates the EBSD results of S32304 following immersion in a simulated industrial environment solution for 24 h. Table 2 provides the proportion of low-angle grain boundaries under varying deformations. In the phase diagram, green denotes ferrite, while red signifies austenite. At 10 % deformation, 97.2 % of grain boundaries are low angle. As deformation increases to 30 %, ferrite exhibits preferential corrosion, reducing the proportion of low-angle grain boundaries to 87.0 %. At 50 % deformation, though ferrite remains preferentially corroded, austenite shows increased corrosion severity, with low-angle grain boundaries declining to 60.3 %. At 70 % deformation, minimal austenite is observed, with the majority being ferrite, and low-angle grain boundaries decrease to 56.6 %. At 90 % deformation, austenite is scarcely visible, indicating a corrosion transition from ferrite to austenite. Further deformation beyond 70 % doesn’t significantly alter the proportion of low-angle grain boundaries. This highlights a corrosion preference reversal from ferrite to austenite around 70 % deformation.

EBSD of S32304 with various deformation levels after immersion in a simulated industrial environment solution for 24 h.

Grain boundary ratio change with deformation degree.

| Grain boundaries | 10 % | 30 % | 50 % | 70 % | 90 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–10° | 97.2 % | 87.0 % | 60.3 % | 56.6 % | 57.5 % |

| >10° | 2.78 % | 13.0 % | 39.7 % | 43.4 % | 42.5 % |

3.2 Electrochemical behavior analysis

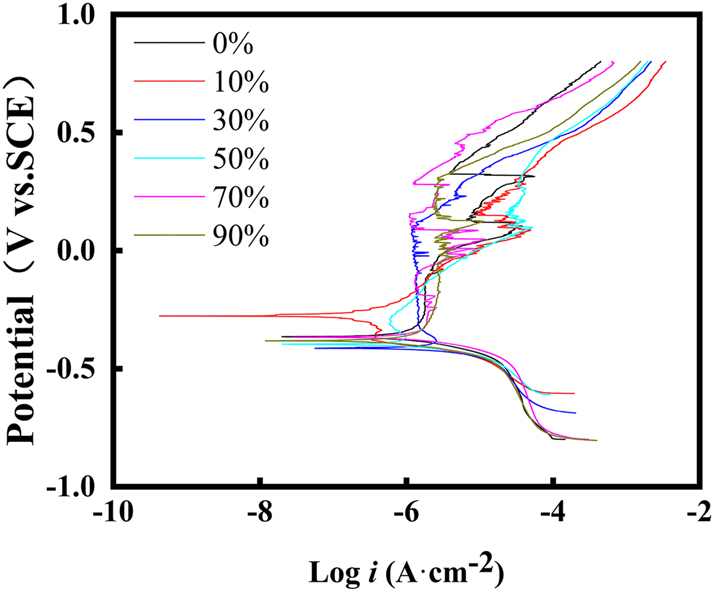

In Figure 6, potentiodynamic polarization results of S32304 duplex stainless steel in a solution of 0.01 mol/L NaHSO3 containing 3.5 wt% NaCl at room temperature are depicted. Deformation appears to influence the corrosion process reactions concurrently. The calculated values of corrosion potential (E corr), corrosion current density (i p), and critical pitting potential (E pit) are presented in Table 3. Notably, The E pit represents the potential at which the current density reaches 100 μA cm−2. The Epit is chosen as the point on the anodic polarization curve where the current density rises sharply and remains elevated without passivating again, which reflects the corrosion tendency of the material and the ease of destruction of the surface passivation film. As deformation increases to 10 %, the E corr shifts in a positive direction, while i p and E pit decrease. At this deformation level, general corrosion resistance improves, but pitting corrosion resistance is reduced. The deformation causes a rise in potential difference between the two phases, reducing the material’s resistance to pitting corrosion.

Potentiodynamic polarization curves of S32304 duplex stainless steel with different deformation level in 0.01 mol/L NaHSO3 solution containing 3.5 wt% NaCl at room temperature.

Electrochemical parameters and their standard deviations for S32304 duplex stainless steel with different cold deformation level in 0.01 mol/L NaHSO3 solution containing 3.5 wt% NaCl at room temperature.

| Deformation (%) | E corr (mVSCE) | i p (μAcm−2) | E pit (mVSCE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −365.475 ± 10.231 | 1.628 ± 0.120 | 329.402 ± 10.965 |

| 10 | −274.893 ± 8.120 | 0.660 ± 0.061 | 149.672 ± 6.104 |

| 30 | −397.255 ± 9.145 | 1.091 ± 0.079 | 108.574 ± 7.124 |

| 50 | −396.816 ± 8.102 | 1.425 ± 0.111 | 138.937 ± 8.234 |

| 70 | −366.947 ± 10.869 | 2.165 ± 0.151 | 280.636 ± 9.100 |

| 90 | −383.005 ± 6.125 | 2.255 ± 0.159 | 295.051 ± 9.986 |

-

E corr, corrosion potential, i p, passive current density, E pit, critical pitting potential.

As deformation increases to 30 %, the E corr shifts toward the negative direction. At the same time, the i p increases, while the E pit still shows a downward trend. This observation may stem from the enhanced resistance of austenite to general corrosion, as documented in previous literature (Luo et al. 2017). However, the decrease in ferrite’s corrosion resistance exacerbates the corrosion current. Despite this, the potential difference between the two phases continues.

With a further increase in deformation to 50 %, i p continues to rise, and the corrosion resistance of austenite begins to decline. Consequently, there is an increase in E pit, accompanied by an increase in the potential difference between the two phases. At a deformation level of 70 %, the i p rapidly escalates to 2.165 ± 0.15 μA/cm2. Surprisingly, the E pit increases to 280.636 ± 9 mVSCE, indicating that although the corrosion intensity increases, the resistance to pitting corrosion is improved. This increase in pitting potential corresponds to a reduction in the potential difference between the two phases.

Upon further deformation to 90 %, the i p continues to climb to 2.255 ± 0.16 μA/cm2, resulting in further deterioration in resistance to general corrosion. However, the E pit also experiences a further increase to 295.051 ± 10 mVSCE. This suggests that despite the heightened general corrosion, the material’s resistance to pitting corrosion improves.

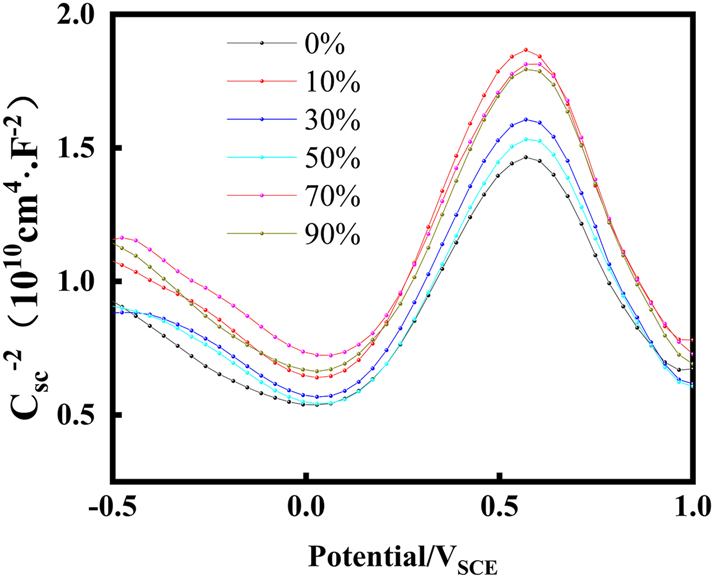

The Mott–Schottky approach was utilized to analyze the semiconducting properties of the material in a 0.01 mol/L NaHSO3 solution containing 3.5 wt% NaCl under various levels of cold deformation. In Figure 7, the Mott–Schottky plots illustrate the relationship between the semiconductor’s capacitance and the applied potential. Each curve on the plot demonstrates two distinct regions with positive and negative slopes, separated by a narrow potential plateau region. In this plateau region lies the flat band potential (E FB), which is a crucial parameter indicating the absence of charge accumulation or depletion. The flat band potential (E FB) was observed to be approximately 0 mVSCE, indicating that the material was neither accumulating nor depleting charges at this potential. This suggests that the material’s surface was in a stable, nonpolarized state in the tested electrolyte solution. As shown in Figure 7, the passive film of S32304 duplex stainless steel presents a p-n heterojunction, independently of cold deformation. The positive slope (E > 0 VSCE) suggests the electronic behavior of an n-type semiconductor, indicating that oxygen vacancies and/or cation interstitials are the major defect. The negative slope (E < 0 VSCE) suggests the electronic behavior of a p-type semiconductor, indicating that cation vacancies are the major defect in the passive film (Taveira et al. 2010).

The Mott–Schottky curve of passive films of S32304 duplex stainless steel with different deformation level in 0.01 mol/L NaHSO3 solution containing 3.5 wt% NaCl at room temperature.

The values of donor density (N D), acceptor density (N A), and E FB were determined from the Mott–Schottky curves. In Table 4, the N D, N A, and E FB values of the passive film formed in 0.01 mol/L NaHSO3 solution containing 3.5 wt% NaCl under various cold deformation levels are presented. It’s noted that there were no significant differences observed in EFB with changes in the cold deformation level. The N D and N A values ranged from 1020 to 1021 cm−3, indicating a consistent order of magnitude compared to previous reports on stainless steel in different environments (Hakiki et al. 2000; Luo et al. 2012; Taveira et al. 2010).

Effect of deformation level on the N D, N A, and E FB of the passive film of S32304 duplex stainless steel with different deformation level in 0.01 mol/L NaHSO3 solution containing 3.5 wt% NaCl at room temperature.

| Deformation (%) | N D/1020cm−3 | N A/1020cm−3 | E FB (mVSCE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3.71 ± 0.11 | 2.86 ± 0.03 | 73.27 ± 5.56 |

| 10 | 3.12 ± 0.09 | 2.78 ± 0.05 | 50.99 ± 4.32 |

| 30 | 3.47 ± 0.05 | 2.90 ± 0.07 | 61.48 ± 4.89 |

| 50 | 3.50 ± 0.04 | 3.14 ± 0.10 | 54.33 ± 4.46 |

| 70 | 3.23 ± 0.06 | 2.23 ± 0.06 | 91.85 ± 6.89 |

| 90 | 3.42 ± 0.08 | 2.63 ± 0.07 | 72.81 ± 6.57 |

The trend observed in the results indicates that N D initially decreases, then slightly increases, and eventually stabilizes. This trend is mirrored in the changes observed for N A. The presence of a high donor density is found to be unfavorable for the stability of the passivation film, aligning with findings from electrochemistry studies.

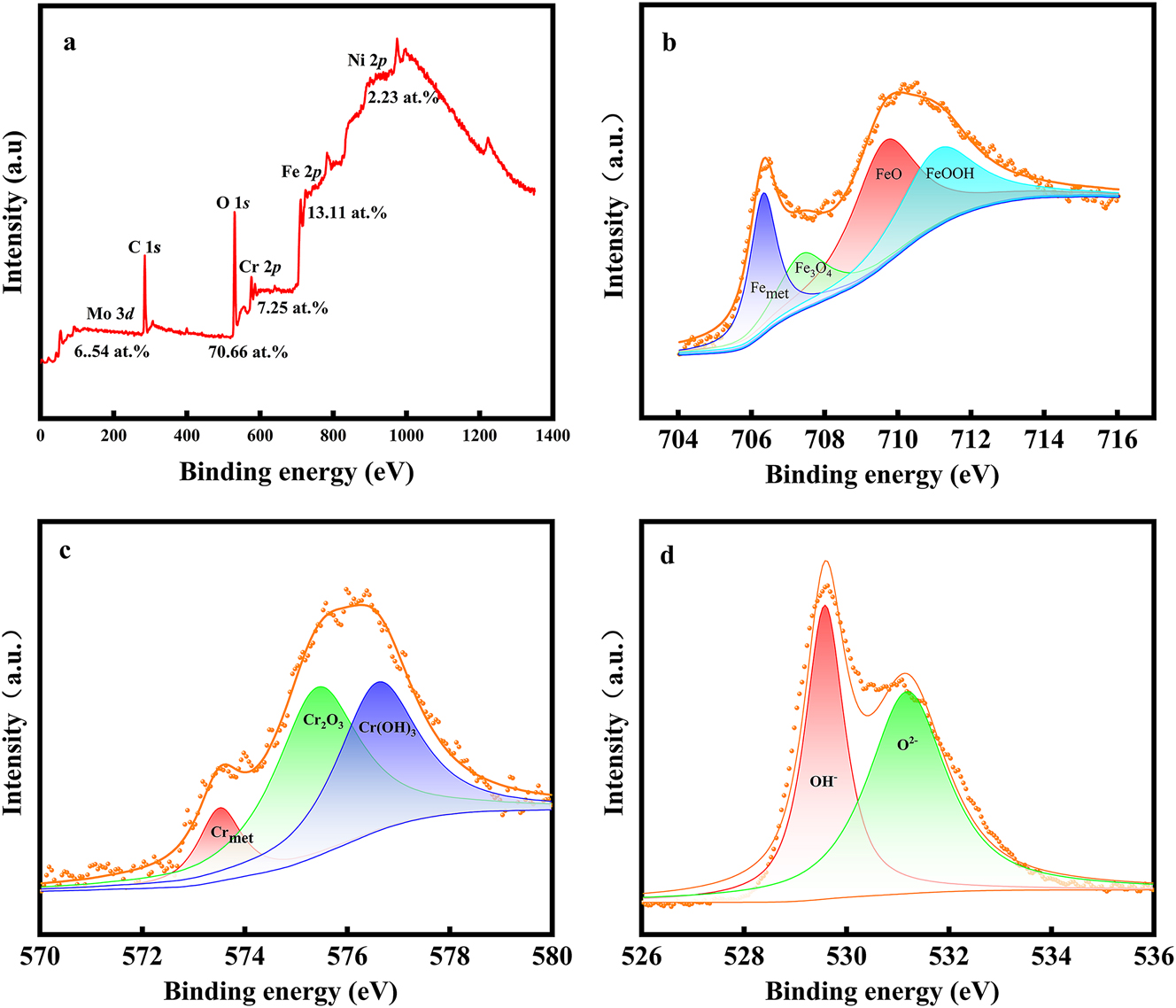

3.3 Characterization of surface passive film

The stability, protective character, and semiconducting properties of S32304 duplex stainless steel are associated with the composition of the passive film. The full spectrum result of XPS, as depicted in Figure 8, reveals the predominant elements in the passive film. These include Mo, O, Cr, Fe, and Ni, with respective atomic percentages of 6.54 %, 70.66 %, 7.25 %, 13.11 %, and 2.23 %.

Spectra of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS): (a) full spectrum of XPS. The percentage is atomic concentration (b) Fe 2p, (c) Cr 2p, and (d) O 1s.

The XPS spectra depicted in Figure 8 provide detailed insight into the chemical states of individual element within the passive film. The fine spectrum of Fe 2p reveals iron existing in four distinct chemical states: metallic iron (Femet), iron (II) oxide (FeO), iron (III) oxide (Fe2O3), and iron oxyhydroxide (FeOOH), with FeO and Fe2O3 representing the most prominent peaks [43]. The Cr 2p spectrum demonstrates chromium present in three different forms within the passive film: metallic chromium (Crmet), chromium (III) oxide (Cr2O3), and chromium hydroxide (Cr(OH)3), with Cr2O3 and Cr(OH)3 being the predominant constituents(Wei et al. 2022). The fine spectrum of O 1s primarily manifests two significant chemical states: hydroxide (OH−) and superoxide (O2 −) (Zhao et al. 2022b).

From the XPS analysis, it is evident that the passive film is primarily composed of iron oxides (FeO and Fe2O3) and chromium oxides (Cr2O3 and Cr(OH)3). These chemical states contribute to the stability and protective properties of the passive film on UNS S32304 duplex stainless steel.

4 Discussion

Under conditions where the passivation film is not stably present (such as in a reductive acid environment), according to the potential-pH diagrams of various elements, it can be known that the passivation film is difficult to form. Without the protection of the passivation film, austenite and ferrite are directly exposed to the corrosive medium. The dissolution process is mainly the continuous dissolution process of the alloy elements Fe and Cr in the matrix (Yao et al. 2015).

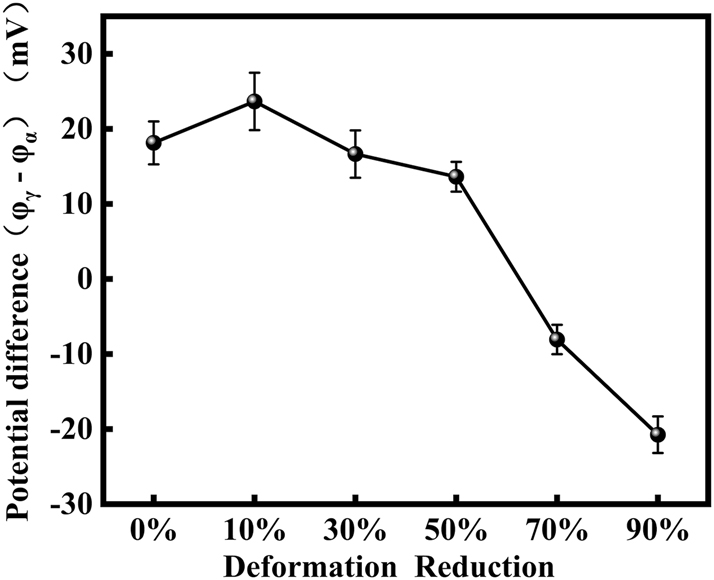

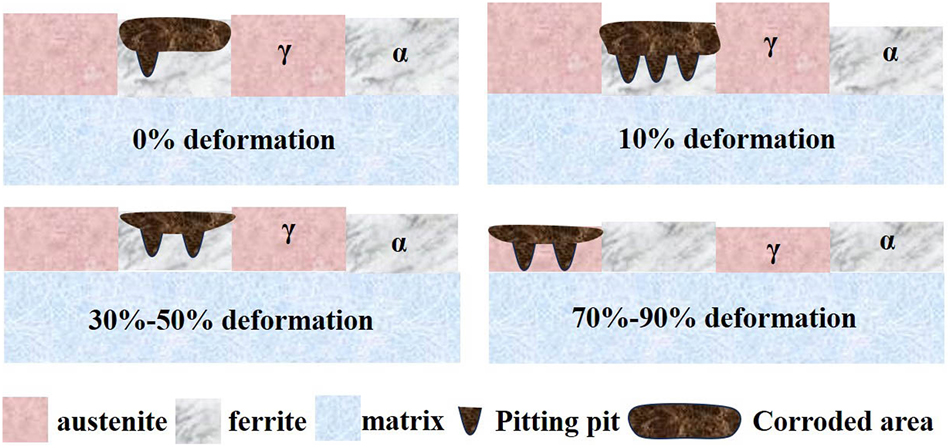

There is a potential difference of approximately 50–100 mV between the austenite and ferrite phases (Örnek and Engelberg 2015; Örnek et al. 2019). Theoretically, this potential difference should cause microgalvanic corrosion and accelerate the corrosion of ferrite. Mondal et al. proposed that the corrosion resistance of ferrite decreases monotonically with strain, but it does not decrease in the austenite phase (Mondal et al. 2019). Austenite forms slip bands and subgrains under small deformations, which almost does not reduce pitting corrosion resistance. However, austenite forms large-angle grain boundaries under large deformations, reducing the resistance to pitting. Therefore, the relative pitting corrosion resistance between ferrite and austenite reverses with increasing cold deformation (Fréchard et al. 2006).

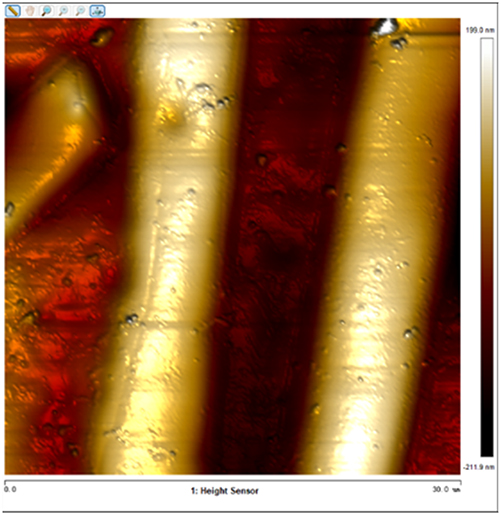

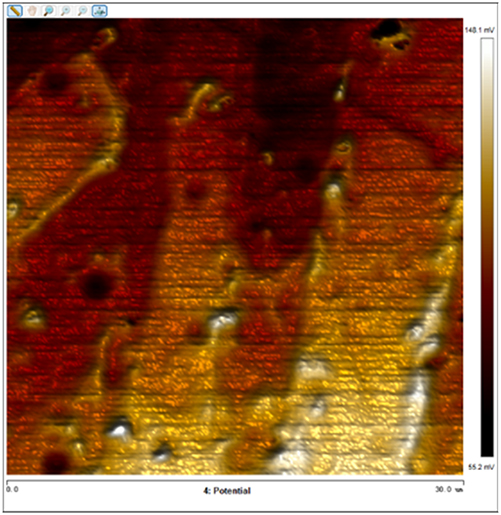

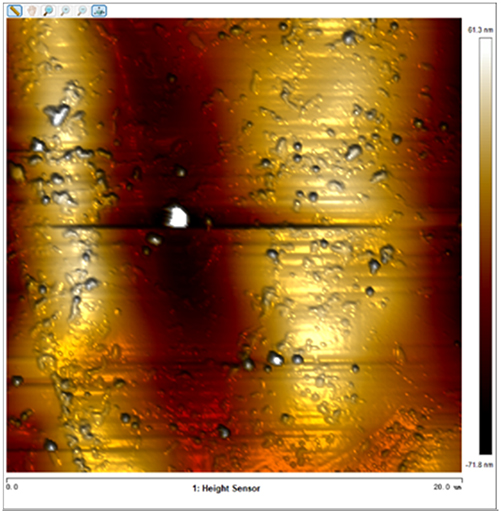

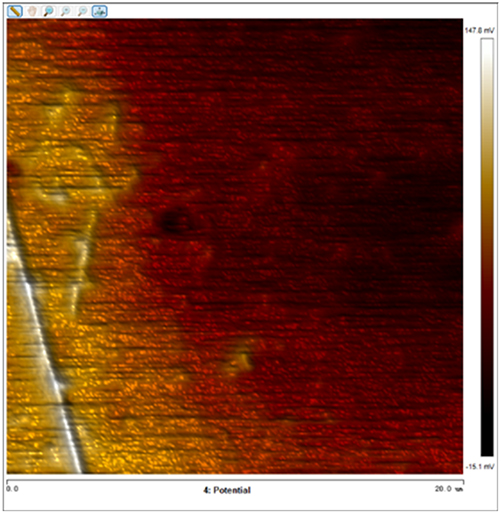

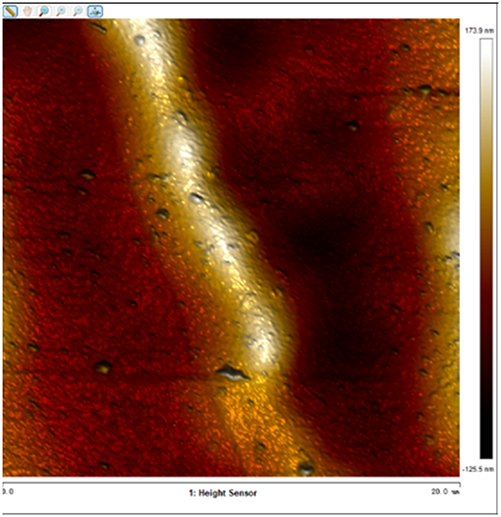

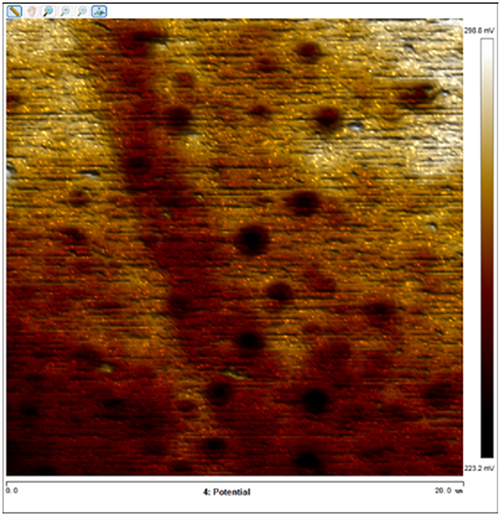

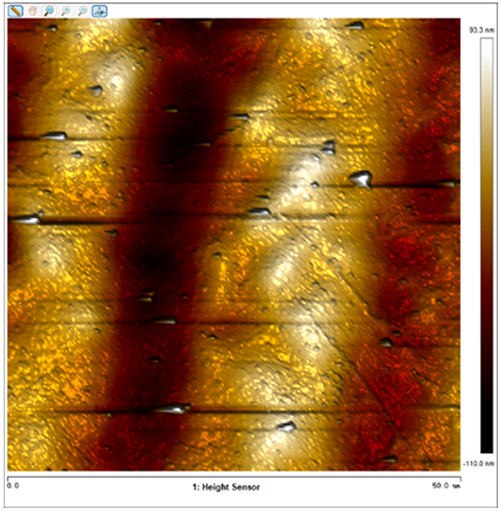

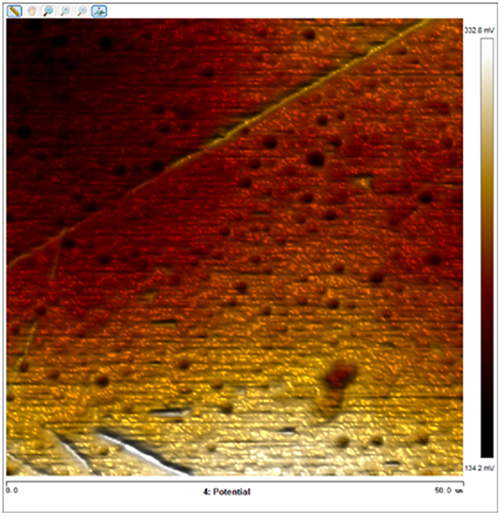

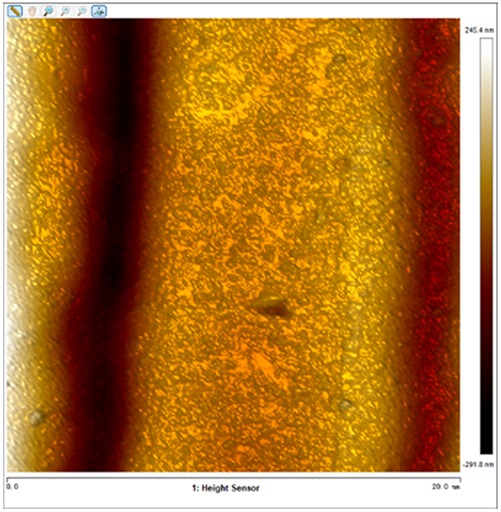

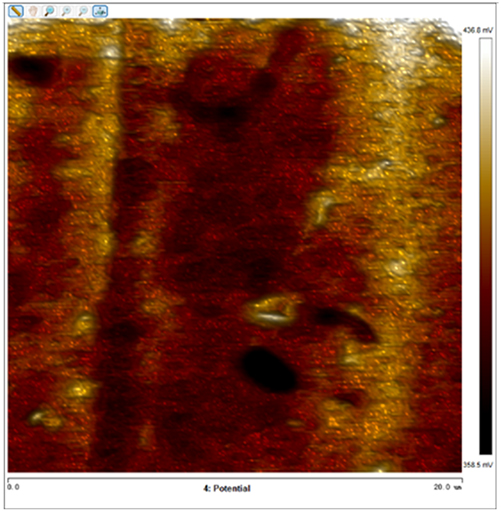

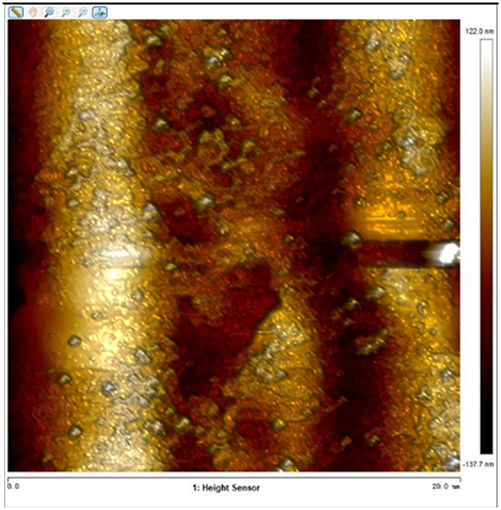

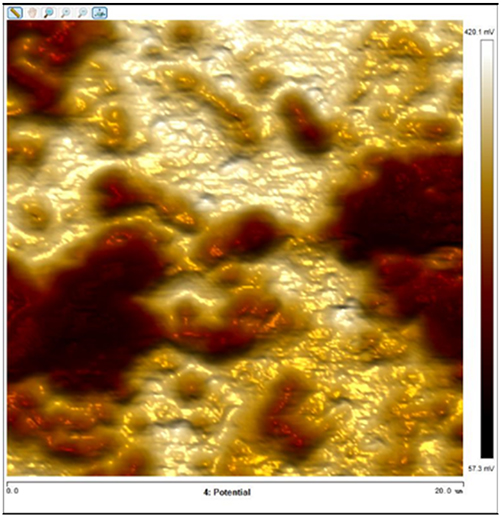

After soaking the sample in an artificial simulated industrial environment for 24 h and breaking the passivation film, the relative difference in surface Volta potential and topography between various phases was measured using atomic force microscopy (AFM). This measurement was conducted with scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy (SKPFM) in frequency modulation mode. The potential difference between austenite and ferrite was calculated through this process, providing valuable insights into the electrochemical behavior and corrosion resistance of the different phases within the sample. This experimental approach allows for a detailed understanding of how the passivation film breakdown affects the surface characteristics and electrochemical properties of the material under investigation.

The results presented in Table 5 are processed using NanoScope Analysis software. To calculate the potential difference, five parallel lines are selected on each frame for statistical analysis. The potential difference is determined by subtracting the potential of ferrite from the potential of austenite (φ γ–φ α). This approach allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the electrochemical characteristics and potential variations between the different phases of the sample.

The topographic maps and Volta potential of S32304 duplex stainless steel with different deformation level after immersion in a simulated industrial environment solution for 24 h at room temperature.

| Deformation (%) | Topography | Volta potential | Potential difference (φ γ–φ α) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 |

|

|

18.138 ± 3.124 |

| 10 |

|

|

23.664 ± 5.142 |

| 30 |

|

|

16.646 ± 4.112 |

| 50 |

|

|

13.616 ± 2.124 |

| 70 |

|

|

−8.064 ± 1.124 |

| 90 |

|

|

−20.747 ± 3.104 |

-

The potential difference is the potential of austenite minus the potential of ferrite (φ γ–φ α).

It can be observed that the variation in potential between the two phases initially increases and then decreases from Figure 9. From the observations provided, it’s evident that the electrochemical behavior and corrosion resistance of S32304 duplex stainless steel are significantly influenced by deformation conditions. Here is a breakdown of the mechanisms described:

Diagram of potential difference of S32304 duplex stainless steel with different deformation level after immersion in a simulated industrial environment solution for 24 h.

Initial deformation effect: initially, as the specimen undergoes slight deformation, the potential of ferrite decreases and the corrosion resistance declines. The potential change of austenite may increase to some extent, which leads to an increase in the potential difference between the austenite and ferrite phases and a decrease in the pitting potential. However, due to the contribution of the austenite phase, the overall corrosion current decreases. Increased deformation: as the deformation level increases, the corrosion resistance of both phases experiences a decline. The corrosion resistance of the ferrite phase continuously decreases, while the corrosion resistance of the austenite phase significantly decreases due to the appearance of large-angle grain boundaries and martensitic dislocations. At deformation levels of 70 % and 90 %, the potential difference between the two phases becomes negative, indicating that the austenite phase is corroded first. This finding is consistent with earlier electrochemical observations and further confirms the corrosion behavior under different deformation conditions. The mechanism of these effects on the corrosion of S32304 duplex stainless steel is illustrated in Figure 10, providing a visual representation of the observed phenomena. These insights are crucial for understanding the material’s corrosion behavior and for developing strategies to improve its corrosion resistance under various deformation scenarios.

A comprehensive mechanism diagram to describe effect of different deformation on corrosion mechanism of S32304 duplex stainless steel.

5 Conclusions

This study explored the effects of different levels of deformation on the corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel in simulated industrial environments using electrochemical analysis, electron backscatter diffraction, and surface analysis techniques. The key findings of the study are as follows:

Under small deformation conditions, electrochemical results show that the corrosion current of S32304 duplex stainless steel decreases. This is speculated to be because the contribution of the improved corrosion resistance of austenite is greater than the impact of the decreased corrosion resistance of ferrite. The coupling of the two leads to a reduction in the corrosion current of stainless steel. However, due to the increased potential difference between austenite and ferrite phases, the pitting corrosion resistance of the material declines.

Under severe deformation conditions, the corrosion current of S32304 duplex stainless steel continues to increase. The E pit decreases at first and then increases, but it still remains lower than under undeformed conditions. When deformation reaches 70 %, a large number of high-angle grain boundaries form in the austenitic phase, leading to a significant decrease in potential, eventually falling below the potential of the ferritic phase. As a result, the potential difference between the austenitic and ferritic phases reverses, with the austenitic phase now more prone to corrosion.

Deformation seems to have no effect on the semiconductor properties of the passivation film of S32304 duplex stainless steel. The main components of the passivation film of duplex stainless steel are iron oxides (FeO and Fe2O3) and chromium oxides (Cr2O3 and Cr(OH)3).

Funding source: Central Government Guided Local Science and Technology Development Funds

Award Identifier / Grant number: 246Z1020G

Funding source: National Key Research and Development Program of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2023YFB3712400

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 52027805

Award Identifier / Grant number: U1806220

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 52204381

Award Identifier / Grant number: U1806220

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Huihua Guo: conducting experiments, formal analysis, and writing original draft; Jingyuan Li: conceptualization, supervision, and funding acquisition; Qingdi Gong: supervision, review & editing; Li Wang: review & editing. The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Research funding: This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant no. 2023YFB3712400); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 52027805); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 52204381); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. U1806220); Central Government Guided Local Science and Technology Development Funds (246Z1020G).

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

Abreu, C.M., Cristóbal, M.J., Losada, R., Nóvoa, X.R., Pena, G., and Pérez, M.C. (2004). Comparative study of passive films of different stainless steels developed on alkaline medium. Electrochim. Acta 49: 3049–3056, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-4686(04)00277-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Alvarez, S.M., Bautista, A., and Velasco, F. (2013). Influence of strain-induced martensite in the anodic dissolution of austenitic stainless steels in acid medium. Corros. Sci. 69: 130–138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2012.11.033.Suche in Google Scholar

Brandi, S.D. and Schön, C. (2017). A thermodynamic study of a constitutional diagram for duplex stainless steels. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 38: 268–275, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11669-017-0537-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Breda, M., Pezzato, L., Pizzo, M., and Calliari, I. (2015). Effect of cold rolling on pitting resistance in duplex stainless steels. Metallurgia Ital. 106: 15–19.Suche in Google Scholar

Burstein, G.T. and Ilevbare, G.O. (1996). The effect of specimen size on the measured pitting potential of stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 38: 2257–2265, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-938x(97)83146-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Burstein, G.T. and Vines, S.P. (2001). Repetitive nucleation of corrosion pits on stainless steel and the effects of surface roughness. J. Electrochem. Soc. 148: B504, https://doi.org/10.1149/1.1416503.Suche in Google Scholar

Burstein, G.T., Liu, C., Souto, R.M., and Vines, S.P. (2004). Origins of pitting corrosion. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 39: 25–30, https://doi.org/10.1179/147842204225016859.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, M., He, J., Li, J., Liu, H., Xing, S., and Wang, G. (2022). Excellent cryogenic strength-ductility synergy in duplex stainless steel with heterogeneous lamella structure. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 831: 142335, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2021.142335.Suche in Google Scholar

Fréchard, S., Martin, F., Clément, C., and Cousty, J. (2006). AFM and EBSD combined studies of plastic deformation in a duplex stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 418: 312–319, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2005.11.047.Suche in Google Scholar

Fu, X., Ji, Y., Cheng, X., Dong, C., Fan, Y., and Li, X. (2020). Effect of grain size and its uniformity on corrosion resistance of rolled 316L stainless steel by EBSD and TEM. Mater. Today Commun. 25: 101429, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101429.Suche in Google Scholar

Gholami, M., Hoseinpoor, M., and Moayed, M.H. (2015). A statistical study on the effect of annealing temperature on pitting corrosion resistance of 2205 duplex stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 94: 156–164, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2015.01.054.Suche in Google Scholar

Hakiki, N.E., Montemor, M.F., Ferreira, M.G.S., and Da Cunha Belo, M. (2000). Semiconducting properties of thermally grown oxide films on AISI 304 stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 42: 687–702, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-938x(99)00082-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Hamdy, A.S., El-Shenawy, E., and El-Bitar, T. (2006). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy study of the corrosion behavior of some niobium bearing stainless steels in 3.5% NaCl. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 1: 171–180, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1452-3981(23)17147-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Jia, Q., Wang, Y., Mei, R., Chen, L., Hao, S., Zhang, H., Ma, X., Zou, Z., and Jin, M. (2021). The dependences of deformation temperature on the strain-hardening characteristics and fracture behavior of Mn–N bearing lean duplex stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 819: 141440, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2021.141440.Suche in Google Scholar

Kim, K., Park, Y.-G., Hyun, B.G., Choi, M., and Park, J.-U. (2019). Recent advances in transparent electronics with stretchable forms. Adv. Mater. 31: 1804690, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201804690.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Lebedev, A.A. and Kosarchuk, V.V. (2000). Influence of phase transformations on the mechanical properties of austenitic stainless steels. Int. J. Plast. 16: 749–767, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-6419(99)00085-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Leygraf, C., Pan, J., and Femenia, M. (2004). Microscopic corrosion studies of duplex stainless steels. Acta Metall. Sin. (English Letters) 17: 625–631.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, W., Gu, J., Deng, Y., and Li, J. (2022). Comprehending the coupled effect of multiple microstructure defects on the passive film features and pitting behavior of UNS S32101 in simulated seawater. Electrochim. Acta 411: 140055, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2022.140055.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, M., Du, C., Liu, Z., Wang, L., Zhong, R., Cheng, X., Ao, J., Duan, T., Zhu, Y., and Li, X. (2023). A review on pitting corrosion and environmentally assisted cracking on duplex stainless steel. Microstructures 3: 2023020, https://doi.org/10.20517/microstructures.2023.02.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, M., Huang, S., Liu, Z., and Du, C. (2024a). Investigations on the passive and pitting behaviors of the multiphase stainless steel in chlorine atmosphere. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 28: 3365–3375, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.12.243.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Z., Wu, Z., Han, Y., Song, X., Zu, G., Zhu, W., and Ran, X. (2024b). Combination of high yield strength and improved ductility of 21Cr lean duplex stainless steel by tailoring cold deformation and low-temperature short-term aging. Acta Metall. Sin. (English Letters) 37: 695–702, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40195-023-01626-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Luo, H., Dong, C.F., Li, X.G., and Xiao, K. (2012). The electrochemical behaviour of 2205 duplex stainless steel in alkaline solutions with different pH in the presence of chloride. Electrochim. Acta 64: 211–220, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2012.01.025.Suche in Google Scholar

Luo, H., Wang, X., Dong, C., Xiao, K., and Li, X. (2017). Effect of cold deformation on the corrosion behaviour of UNS S31803 duplex stainless steel in simulated concrete pore solution. Corros. Sci. 124: 178–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2017.05.021.Suche in Google Scholar

Martin, G., Caldemaison, D., Bornert, M., Pinna, C., Bréchet, Y., Véron, M., Mithieux, J.D., and Pardoen, T. (2013). Characterization of the high temperature strain partitioning in duplex steels. Exper. Mech. 53: 205–215, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11340-012-9628-y.Suche in Google Scholar

Mondal, R., Bonagani, S.K., Lodh, A., Sharma, T., Sivaprasad, P.V., Chai, G., Kain, V., and Samajdar, I. (2019). Relating general and phase specific corrosion in a super duplex stainless steel with phase specific microstructure evolution. Corrosion 75: 1315–1326, https://doi.org/10.5006/3091.Suche in Google Scholar

Nilsson, J.O. (1992). Super duplex stainless steels. Mater. Sci. Technol. 8: 685–700, https://doi.org/10.1179/mst.1992.8.8.685.Suche in Google Scholar

Örnek, C. and Engelberg, D.L. (2015). SKPFM measured Volta potential correlated with strain localisation in microstructure to understand corrosion susceptibility of cold-rolled grade 2205 duplex stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 99: 164–171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2015.06.035.Suche in Google Scholar

Örnek, C., Långberg, M., Evertsson, J., Harlow, G., Linpé, W., Rullik, L., Carlà, F., Felici, R., Kivisäkk, U., Lundgren, E., et al.. (2019). Influence of surface strain on passive film formation of duplex stainless steel and its degradation in corrosive environment. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166: C3071, https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0101911jes.Suche in Google Scholar

Poonguzhali, A., Pujar, M.G., and Kamachi Mudali, U. (2013). Effect of nitrogen and sensitization on the microstructure and pitting corrosion behavior of AISI type 316LN stainless steels. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 22: 1170–1178, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-012-0356-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Saha, D.C., Biro, E., Gerlich, A.P., and Zhou, Y. (2020). Influences of blocky retained austenite on the heat-affected zone softening of dual-phase steels. Mater. Lett. 264: 127368, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2020.127368.Suche in Google Scholar

Shahryari, A., Szpunar, J.A., and Omanovic, S. (2009). The influence of crystallographic orientation distribution on 316LVM stainless steel pitting behavior. Corros. Sci. 51: 677–682, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2008.12.019.Suche in Google Scholar

Shakhova, I., Dudko, V., Belyakov, A., Tsuzaki, K., and Kaibyshev, R. (2012). Effect of large strain cold rolling and subsequent annealing on microstructure and mechanical properties of an austenitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 545: 176–186, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2012.02.101.Suche in Google Scholar

Sharafi, S. (2009). Microstructure of super-duplex stainless steels. Apollo: University of Cambridge Repository, Cambridge.Suche in Google Scholar

Shen, K., Jiang, W., Sun, C., Wan, Y., Zhao, W., and Sun, J. (2023). Insight into microstructure, microhardness and corrosion performance of 2205 duplex stainless steel: effect of plastic pre-strain. Corros. Sci. 210: 110847, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2022.110847.Suche in Google Scholar

Silva, R., Vacchi, G.S., Kugelmeier, C.L., Santos, I.G.R., Filho, A.M., Magalhães, D.C.C., Afonso, C.R.M., Sordi, V.L., and Rovere, C.D. (2022). New insights into the hardening and pitting corrosion mechanisms of thermally aged duplex stainless steel at 475 °C: a comparative study between 2205 and 2101 steels. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 98: 123–135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2021.04.046.Suche in Google Scholar

Sims, I. (2013). Book review: the history of stainless steel. In: Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers Construction Materials, ICE Publishing, London, Vol. 166, p. 57.10.1680/coma.11.00066Suche in Google Scholar

Tang, Z. and Aday, X. (2024). Three-dimensional modeling of pitting corrosion considering the crystallographic orientation of the microstructure. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 19: 100526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoes.2024.100526.Suche in Google Scholar

Taveira, L.V., Montemor, M.F., Da Cunha Belo, M., Ferreira, M.G., and Dick, L.F.P. (2010). Influence of incorporated Mo and Nb on the Mott–Schottky behaviour of anodic films formed on AISI 304L. Corros. Sci. 52: 2813–2818, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2010.04.021.Suche in Google Scholar

Liang, T., Hu, X., Kang, X., and Li, D. (2013). Microstructure evolution of a cold-rolled 25Cr-7Ni-3Mo-0.2N duplex stainless steel during two-step aging treatments. Acta Metall. Sin. (English Letters) 26: 517–522, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40195-013-0210-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Tsai, W.-T. and Chen, J.-R. (2007). Galvanic corrosion between the constituent phases in duplex stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 49: 3659–3668, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2007.03.035.Suche in Google Scholar

Wei, Y., Pan, Z., Fu, Y., Yu, W., He, S., Yuan, Q., Luo, H., and Li, X. (2022). Effect of annealing temperatures on microstructural evolution and corrosion behavior of Ti-Mo titanium alloy in hydrochloric acid. Corros. Sci. 197: 110079, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2021.110079.Suche in Google Scholar

Xu, H., Hu, W., Kang, C., Li, W., and Sha, X. (2021). Microstructure evolution during annealing at different temperatures and hot deformation behavior of lean duplex stainless steel 2101. Steel Res. Int. 92: 2000264, https://doi.org/10.1002/srin.202000264.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, J., Wang, Q., and Guan, K. (2013). Effect of stress and strain on corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel. Int. J. Pres. Ves. Pip. 110: 72–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpvp.2013.04.025.Suche in Google Scholar

Yao, J., Dong, C., Man, C., Xiao, K., and Li, X. (2015). The electrochemical behavior and characteristics of passive film on 2205 duplex stainless steel under various hydrogen charging conditions. Corrosion 72: 42–50.10.5006/1811Suche in Google Scholar

Yin, L., Liu, Y., Qian, S., Jiang, Y., and Li, J. (2019a). Synergistic effect of cold work and hydrogen charging on the pitting susceptibility of 2205 duplex stainless steel. Electrochim. Acta 328: 135081, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135081.Suche in Google Scholar

Yin, L., Liu, Y., Qian, S., Jiang, Y., and Li, J. (2019b). Synergistic effect of cold work and hydrogen charging on the pitting susceptibility of 2205 duplex stainless steel. Electrochim. Acta 328: 135081, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135081.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, Q., Li, J., Chen, Y., Li, W., and Gao, Z. (2021). Effect of solution temperature on cold rolling properties of lean duplex stainless steel. Steel Res. Int. 92: 2000612, https://doi.org/10.1002/srin.202000612.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, Y., Wang, C., Reddy, K.M., Li, W., and Wang, X. (2022). Study on the deformation mechanism of a high-nitrogen duplex stainless steel with excellent mechanical properties originated from bimodal grain design. Acta Mater. 226: 117670, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2022.117670.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhao, K., Li, X.-Q., Wang, L.-W., Yang, Q.-R., Cheng, L.-J., and Cui, Z.-Y. (2022a). Passivation behavior of 2507 super duplex stainless steel in hot concentrated seawater: influence of temperature and seawater concentration. Acta Metall. Sin. (English Letters) 35: 326–340, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40195-021-01272-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhao, Q., Pan, Z., Wang, X., Luo, H., Liu, Y., and Li, X. (2022b). Corrosion and passive behavior of AlxCrFeNi3−x (x = 0.6, 0.8, 1.0) eutectic high entropy alloys in chloride environment. Corros. Sci. 208: 110666, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2022.110666.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhou, Y., Kong, D., Li, R., He, X., and Dong, C. (2024). Corrosion of duplex stainless steel manufactured by laser powder bed fusion: a critical review. Acta Metall. Sin. (English Letters) 37: 587–606, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40195-024-01679-z.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Recent findings on lignin-based wear and corrosion resistance coatings

- Progress in the study of micro-arc oxidation film layers on biomedical metal surfaces

- A review on internal corrosion of pipelines in the oil and gas industry due to hydrogen sulfide and the role of coatings as a solution

- Cathodic protection and sulphate-reducing bacteria: a complex interaction in offshore steel structures

- Original Articles

- Correlation between synthesis conditions and corrosion behavior of nickel–aluminum layered double hydroxide (LDH)-sealed anodized aluminum

- Impact of plastic deformation on the corrosion behavior of S32304 duplex steel in a simulated industrial solution

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Corrosion of stainless steels and corrosion protection strategies in the semiconductor manufacturing industry: a review

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Recent findings on lignin-based wear and corrosion resistance coatings

- Progress in the study of micro-arc oxidation film layers on biomedical metal surfaces

- A review on internal corrosion of pipelines in the oil and gas industry due to hydrogen sulfide and the role of coatings as a solution

- Cathodic protection and sulphate-reducing bacteria: a complex interaction in offshore steel structures

- Original Articles

- Correlation between synthesis conditions and corrosion behavior of nickel–aluminum layered double hydroxide (LDH)-sealed anodized aluminum

- Impact of plastic deformation on the corrosion behavior of S32304 duplex steel in a simulated industrial solution

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Corrosion of stainless steels and corrosion protection strategies in the semiconductor manufacturing industry: a review