Abstract

This paper reports on the influence of heat treatment on the corrosion properties of CuAlMn alloy in 0.1%, 0.9% and 1.5% NaCl solution (pH = 7.4). Heat treatment of alloy samples was performed by samples annealing at 900°C for 30 min. Electrochemical methods of investigations included measuring the open circuit potential (Eoc) and linear and potentiodynamic polarisation. Optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) were used to study the morphology and composition of the corroded surfaces, along with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and atomic force microscopy (AFM). Heat-treated samples have slightly more positive values of Eoc, slightly lower values of corrosion current density and higher values of polarisation resistance compared with the as-cast alloy. The microscopic analysis showed the rough surfaces due to corrosion processes. Increasing the electrolyte concentration leads to an increase in alloy surface damage. AFM and SEM examinations showed that the surface was covered with interlaced layers of corrosion products, as well as cracks and ducts formed by their dissolution. EDX and XPS analyses showed that corrosive products consist mainly of aluminium and manganese oxides and chlorides. Annealed CuAlMn alloy samples have significantly lower copper content compared with the as-cast CuAlMn alloy.

1 Introduction

Shape memory alloys belong to a group of metallic alloys with unique properties, changing from one crystallographic structure to another as a result of a change in temperature or applied stress (Gomez de Salazar et al., 2005; Lojen et al., 2005; Alaneme et al., 2017). Generally, these materials can be plastically deformed at some relatively low temperature and upon exposure to some higher temperature will return to their shape prior to the deformation. This phenomenon is enabled with the occurrence of a martensitic phase transformation, which is a shear-dominant diffusion-less solid-state phase transformation from a parent austenitic phase (Dasgupta, 2014; Sathish et al., 2014). Among all shape memory alloys, Ti-Ni shape memory alloys are used extensively in many engineering and biomedical applications because of its excellent shape memory effect, unique super elasticity, low elastic modulus and good corrosion resistance and biocompatibility (Bogue, 2009; Zheng et al., 2011; Pound, 2014; Kožuh et al., 2016). However, their high cost and low transformation temperatures prohibit their use in applications where biocompatibility is not a necessary feature and is often replaced by Cu-based shape memory alloys. Today, Cu-shape memory alloys are used extensively in actuator and sensor applications, electronics and computer, automotive and aircraft industries (Sreekumar et al., 2007; Lagoudas, 2008; Mikova et al., 2015; Jain et al., 2016). Shortcomings of these alloys such as brittleness and low mechanical strength are closely related to their microstructural characteristics such as coarse and large grain size, high elastic anisotropy and the segregation of secondary phases along the grain boundaries (Moghaddam et al., 2013; Saud et al., 2015b; Jain et al., 2016; Ivanić et al., 2017). As shape memory alloys have significant engineering applications, many researchers have conducted their investigations to overcome these problems, which results in two solutions: alloying with other elements such Ti, or Ag nanoparticles, or heat treatment (Adachi et al., 1989; Morris & Gunter, 1992; Lai et al., 1996; Sutou et al., 2005; Saud et al., 2015b). Mechanical properties of the alloy and internal friction can be notably improved by thermal treatments, according to Dagdelen et al. (2003). They revealed that quenching heat treatment performed on the Cu-Al-Ni alloy samples had significant influence on martensitic transformation behaviour, morphology and transition temperatures. Lai et al. (1996) found that step-quenched samples showed the best martensitic structure for high resistance shape memory degradation, while Ivanić et al. (2017) found that heat treatment influenced the fracture surface morphology of Cu-Al-Ni shape memory alloy. Results of the investigations of Al-Haidary et al. (2017) have shown the effect of heat treatment on the reduction of microhardness of the alloy Cu-13Al-0.54Be. The hardness and precipitates in the alloy also increase with increasing ageing duration.

Most of the researchers focused their investigation of heat treatment influence on the mechanical properties and microstructure of shape memory alloys, but for the practical application of these materials, corrosion behaviour is also very important. Therefore, in this paper the aim was to determine the influence of heat treatment on the corrosion properties of Cu-Al-Mn alloy in NaCl solution. For this purpose, investigations were performed on Cu-Al-Mn cylindrical samples without any heat treatment (as cast) and on annealed and annealed and aged samples, combining different electrochemical and surface analysis methods. Investigations were carried out in sodium chloride solution because chloride ions are one of the most common corrosive agents found in nature.

2 Materials and methods

A CuAlMn alloy with a composition of 82.3% Cu, 8.3% Al and 9.4% Mn in wt.% was prepared by melting of pure elements (w(Cu)=99.9%, w(Mn)=99.8% and w(Al)=99.5%) in a vacuum induction furnace (MaTeck Material Technologie & Kristalle GmbH, Juelich, Germany) under protective argon atmosphere. An alloy cylindrical bar (8 mm diameter) was obtained using the device for vertical continuous casting, which is connected to the vacuum induction furnace. During casting, the pressure of the argon protective atmosphere was set around 500 mbar, and the casting speed was 290 mm min−1. Heat treatment of alloy samples was performed by annealing of samples at 900°C for 30 min, followed by quenching in room-temperature water. After quenching, one alloy sample was subjected to the ageing procedure that was carried out at a temperature of 300°C for 60 min, followed by cooling in water. Investigations were carried out on a sample of CuAlMn alloy in as-cast state – without heat treatment (sample 1) – and on a heat-treated sample by annealing (sample 2) and annealing and ageing (sample 3). For electrochemical measurements, CuAlMn alloy rods were cut to obtain small rollers, 1 cm in height and 8 mm in diameter, from which the electrodes for electrochemical measurements were prepared. A total of nine alloy rollers were cut for electrodes preparation (three rollers in as-cast state sample, three rollers in annealed state sample and three rollers in annealed and aged state sample).

The preparation of the electrodes consisted of soldering CuAlMn alloy rollers to the insulated copper wire followed by their insulation with polyacrylate, leaving only one non-insulated roller base of 0.502 cm2, which was used as a working surface and in contact with the electrolyte. Before each experiment, the working electrode was ground with a Metkon Forcipol 1 V grinding/polishing machine, using successive grades of emery papers down to 2000 grit, polished with Al2O3 polishing suspension (particle size of 0.3 μm) and then ultrasonically washed in ethanol solution.

The differences in CuAlMn samples microstructure, which were generated by heat treatment, were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). For SEM analysis, samples were ground and polished followed by etching in a solution composed of 2.5 g FeCl3 (Iron (III) chloride anhydrous, Fisher Scientific UK, Loughborough, UK) and 48 ml methanol (CH3OH, Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in 10 ml HCl (hydrochloric acid 37% PA-ACS-ISO, Panreac Quimica Sau, Barcelona, Spain).

Electrochemical investigations were performed using Princeton Applied Research M 273A potentiostat/galvanostat (352/252 Corrosion Analysis Software 2.01, Princeton Applied Research, Princeton, NJ, USA) in a three-electrode glass cell in 0.1%, 0.9% and 1.5% NaCl solutions (pH=7.4, T=37°C) (Kemika Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia). The reference electrode was a saturated calomel electrode, and the counter-electrode was a Pt-sheet electrode. Open circuit potential was measured in a 60 min time period immediately after immersion of the electrode into the electrolyte. Linear polarisation measurement was performed in ±15 mV vs. EOC with a scanning rate of 0.2 mV s−1, whereas potentiodynamic polarisation was performed in a potential region of −200 mV vs. EOC to 1.5 V at the sweep rate 0.5 mV s−1 starting from the most negative potential. All electrochemical investigations were repeated three times to ensure good reproducibility of results.

Corrosion surface morphology after electrochemical experiments was investigated using an optical microscope (MXFMS-BD, Dynamic Analysis System Pte. Ltd., China), the scanning electron microscope JEOL JSM 5610 (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with EDS system for compositional analysis. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on CuAlMn samples corroded in 1.5% NaCl solution with a PHI-TFA XPS spectrometer produced by Physical Electronics Inc. (Chanhanssen, MN, USA), and their surfaces were also analysed by an Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) Solver Pro 45, manufactured by NT-MDT Spectrum Instruments (Zelengrad, Moscow, Russia).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Electrochemical investigation

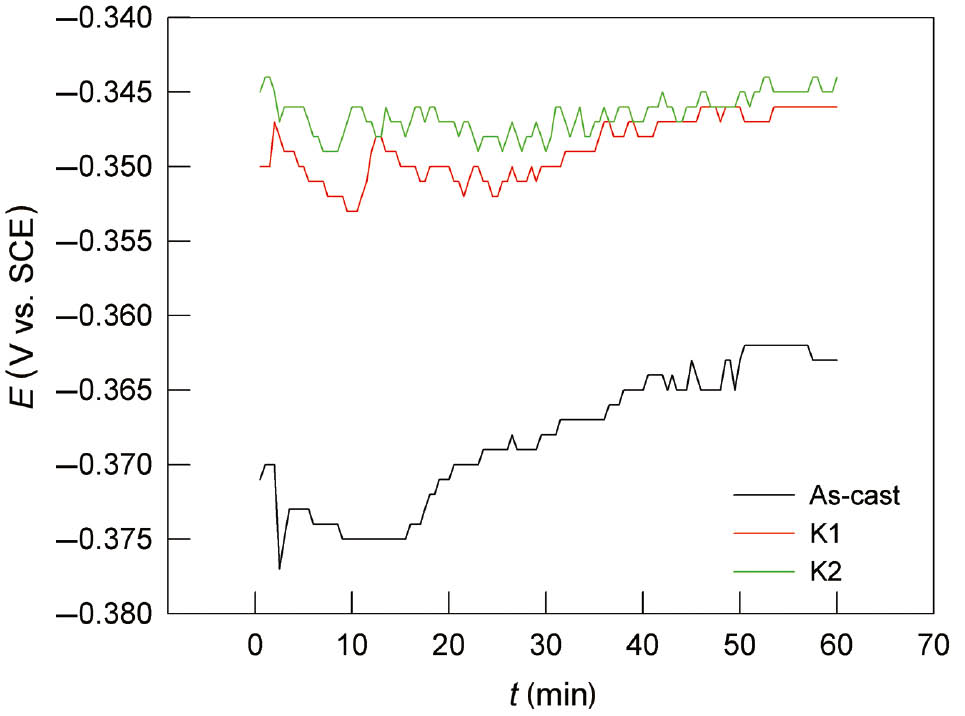

The open circuit potential of the materials under investigation was recorded over 60 min immersion in chloride solution deaerated by purging with Ar, and the results of these investigations in 0.9% NaCl solution are presented in Figure 1.

Variation of open circuit potential of the CuAlMn alloy in 0.9% NaCl solution, as-cast, annealed and annealed and aged state.

The EOC values of heat-treated CuAlMn alloy samples have positive values compared with EOC of as-cast samples. This trend is also visible in investigations in 0.1% and 1.5% NaCl solution. The steady state is reached within 60 min of electrode immersion. With increasing the NaCl concentration, stabilisation of EOC occurs at more negative potential values.

The linear polarisation technique is the DC nondestructive technique that is based on the theory that within 10–20 mV of the corrosion potential, small changes in the potential of a freely corroding electrode have a linear relationship with the current change and so is proportional to the corrosion current. Linear polarisation measurements were performed in order to determine the polarisation resistance (Rp) that represents the resistance of metal to corrosion and is defined by the slope of the polarisation curve near the corrosion potential, by equation (1):

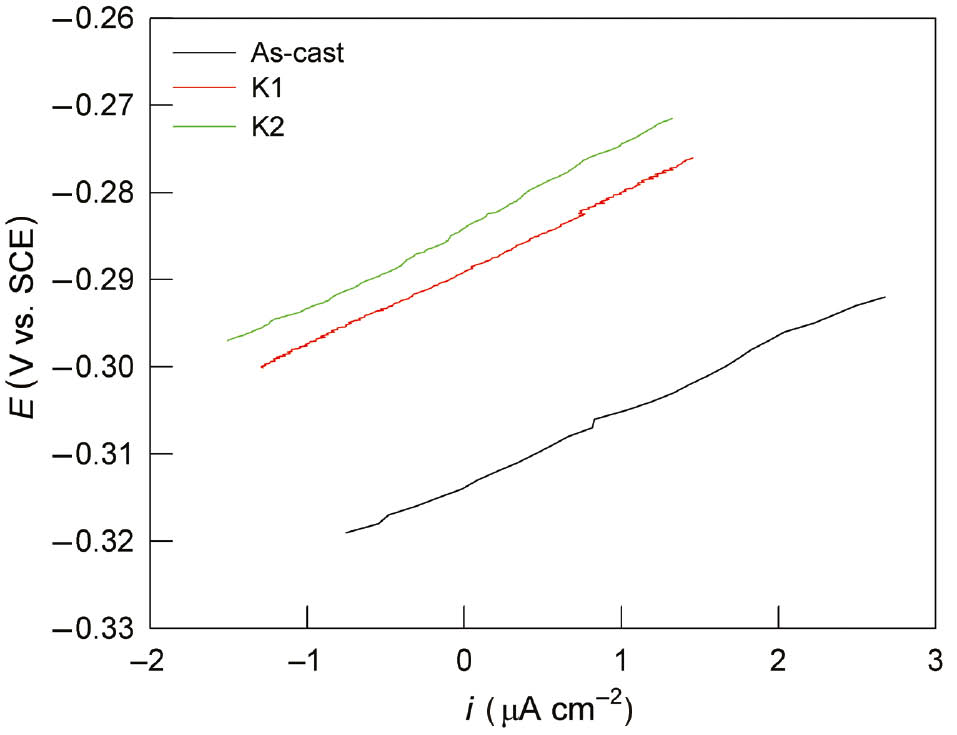

Results of linear polarisation investigations for CuAlMn alloy in 0.1% NaCl solution are presented in Figure 2, and the values of corrosion resistance for the CuAlNi samples are shown in Table 1.

Linear polarisation curves for CuAlMn alloy, as-cast, annealed and annealed and aged state, in 0.9% NaCl solution.

Values of the polarization resistance for the CuAlMn alloy in as-cast, annealed and annealed and aged state, in NaCl solution.

| CuAlMn alloy/NaCl solution | Polarization resistance (Rp, kΩ cm2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% | 0.9% | 1.5% | |

| As-cast | 8.223 | 5.188 | 4.326 |

| Annealed | 8.667 | 6.022 | 4.882 |

| Annealed and aged | 9.369 | 6.565 | 5.200 |

From Figure 2 and Table 1, it can be seen that the heat treatment alloy samples have higher slopes of the polarisation curves, resulting in higher values of Rp. It is also apparent that with the increase of the chloride ions concentration, the value of polarisation resistance decreases, which indicates a more intense corrosion of the alloy. Similar influence of heat treatment and chloride concentration on corrosion resistance was observed in previous investigations on CuAlNi shape memory alloy (Vrsalović et al., 2017, 2018).

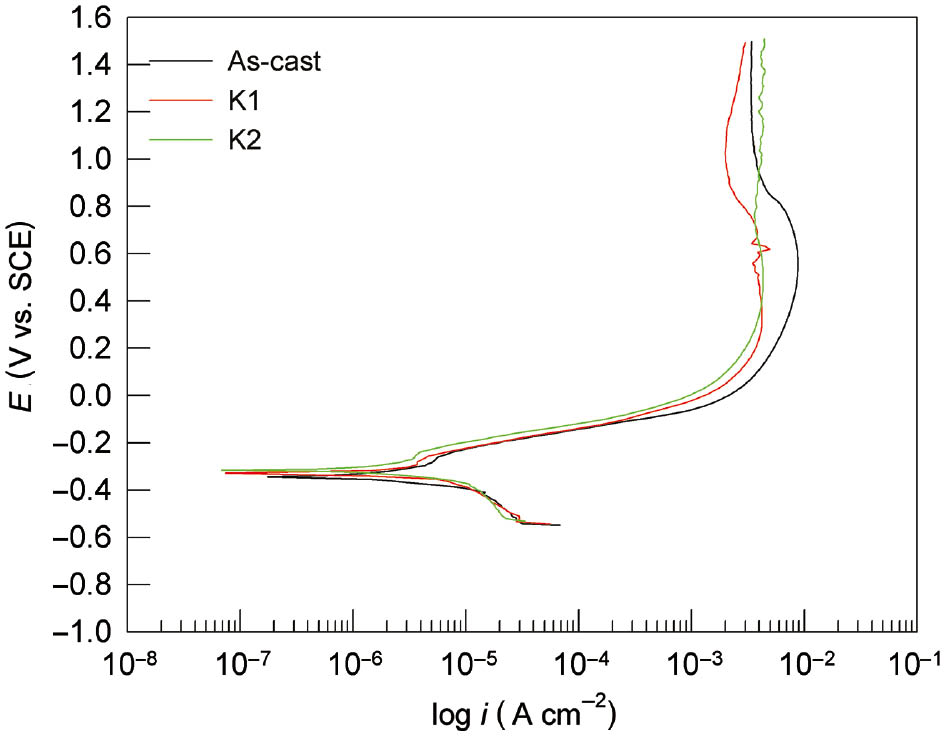

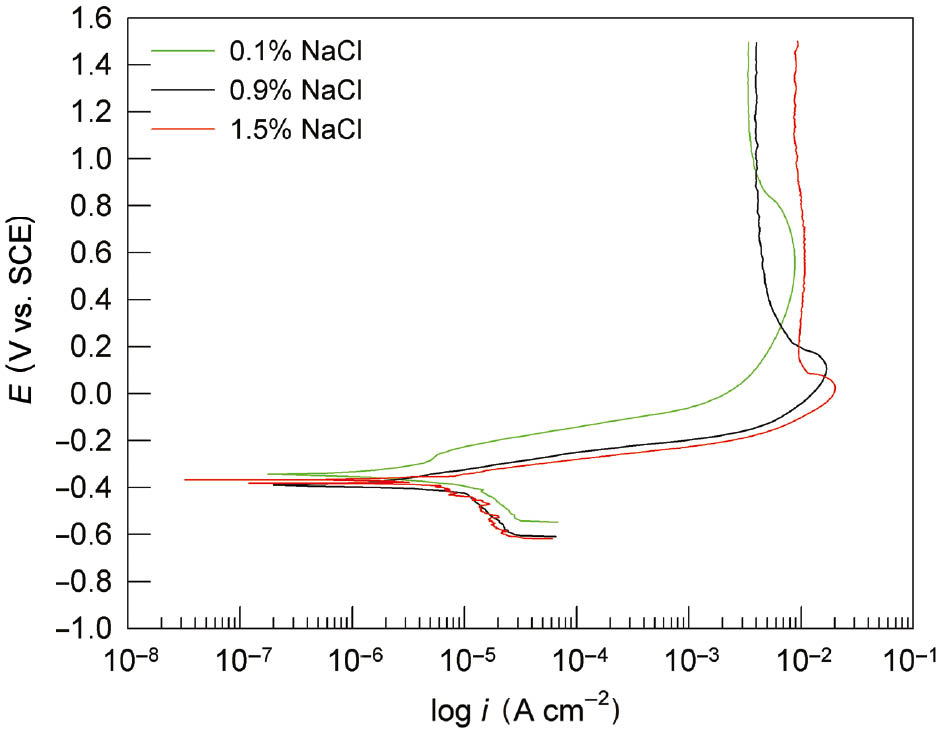

The last applied electrochemical method was a potentiodynamic polarisation method that was carried out in a wide range of potentials to gain insight into the anodic behaviour of CuAlMn subjected to different heat treatment. Figure 3 shows the potentiodynamic polarisation curves for CuAlMn alloy in 0.1% NaCl solution, while Figure 4 shows the influence of chloride concentration on the polarisation curves for the investigated alloy in as-cast state.

Potentiodynamic polarisation curves for CuAlMn alloy, as-cast, annealed and annealed and aged state, in 0.9% NaCl solution.

Effect of chloride ion concentration on potentiodynamic polarisation curves for CuAlMn alloy, as-cast state.

The potentiodynamic polarisation curve is usually presented in a semi-logarithm plot, composed of cathodic and anodic branches, which are the result of the electrochemical reactions in the system. The most common cathodic reaction is the reaction of hydrogen evolution (for acidic or deaerated solutions) or oxygen reduction, while the most common anodic reaction is oxidation reaction or alloy corrosion. From Figure 3, very small differences can be seen between the polarisation curves of as-cast CuAlMn alloy and heat-treated CuAlMn alloy, which indicate a very similar corrosion behaviour. The main differences can be seen in smaller values of anodic current densities for heat treatment alloy samples. In the area of high anodic potentials, anodic current densities have almost identical values, which indicate the same corrosion behaviour. Increase in chloride concentration leads to increase in the values of anodic current densities, which are clearly seen in Figure 4. From Figure 4, it can be seen that all three anodic branches of polarisation curves consist of the apparent Tafel region followed by a pseudo passive region in which the anodic current densities have been reduced to a certain extent because of the formation of a layer of low soluble corrosion products on the surface of the alloy. Similar anodic behaviour has been found in corrosion investigations of Cu, CuAl, CuAlAg, CuAlNi and CuZnNi alloys (Benedetti et al., 1995; Kear et al., 2004; Gojić et al., 2011; Satish et al., 2014; Vrsalović et al., 2018). In the mentioned investigations, an increase in anodic current density can be observed above a certain anodic potential due to the dissolution of corrosion products from the surface, which represent the third region. In the anodic polarisation curves presented in Figures 3 and 4, this third region is missing probably because of the more compact and protective surface film. This could be attributed to the presence of Mn as an alloying element in the investigated alloy. According to the literature, the addition of Mn in small amounts affects the microstructure of the alloy; i.e. it reduces the size of the crystal grain. Namely, Mn diffuses easily and rapidly disperses through the mass of alloy, accumulates on grain boundaries and prevents further grain growth (Sampath, 2005; Saud et al., 2015a). Studies have shown that such refining of microstructures, with the enhancement of mechanical properties, also increases the corrosion resistance of the alloy (Saud et al., 2015a). Namely, the fine microstructure positively affects the compactness and stability of the passive film formed on the alloy. Because of the high affinity of Mn for oxygen, the surface passive film on Cu-Al-Mn alloy contains Mn oxide, which is proven by EDS and XPS surface analyses. The shape of the anodic branch of the curve differs depending on the concentration of chloride ions (Figure 4). It seems that with the increase of chloride ions, a pseudo passive area starts to form at lower anodic potential (around 0.1 V for 1.5% NaCl solution, around 0.2 V for 0.9% NaCl solution and around 0.8 V for 0.1% NaCl solution). Corrosion parameters obtained from potentiodynamic polarisation measurements were presented in Table 2.

Corrosion parameters for the CuAlMn alloy in NaCl solution.

| CuAlMn alloy | NaCl solution (%) | E corr (V) | i corr (μA cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| As-cast | 0.1 | −0.332 | 5.1 |

| Annealed | 0.1 | −0.328 | 4.6 |

| Annealed and aged | 0.1 | −0.320 | 4.1 |

| As-cast | 0.9 | −0.373 | 7.0 |

| Annealed | 0.9 | −0.368 | 6.5 |

| Annealed and aged | 0.9 | −0.362 | 6.1 |

| As-cast | 1.5 | −0.367 | 8.2 |

| Annealed | 1.5 | −0.372 | 7.7 |

| Annealed and aged | 1.5 | −0.365 | 7.3 |

It is evident from Table 2 that the corrosion current value increases with increasing chloride ion concentration, which indicates more intense corrosion of the alloy. Also with the increase of the concentration of chloride ions, the corrosion potential is shifted toward more negative values. The lowest values of corrosion current density and the most positive values of corrosion potential were obtained by heat-treated CuAlMn alloy samples for all NaCl concentrations, but differences in the corrosion current and corrosion potential values for as-cast CuAlMn alloy are small.

3.2 Surface investigation

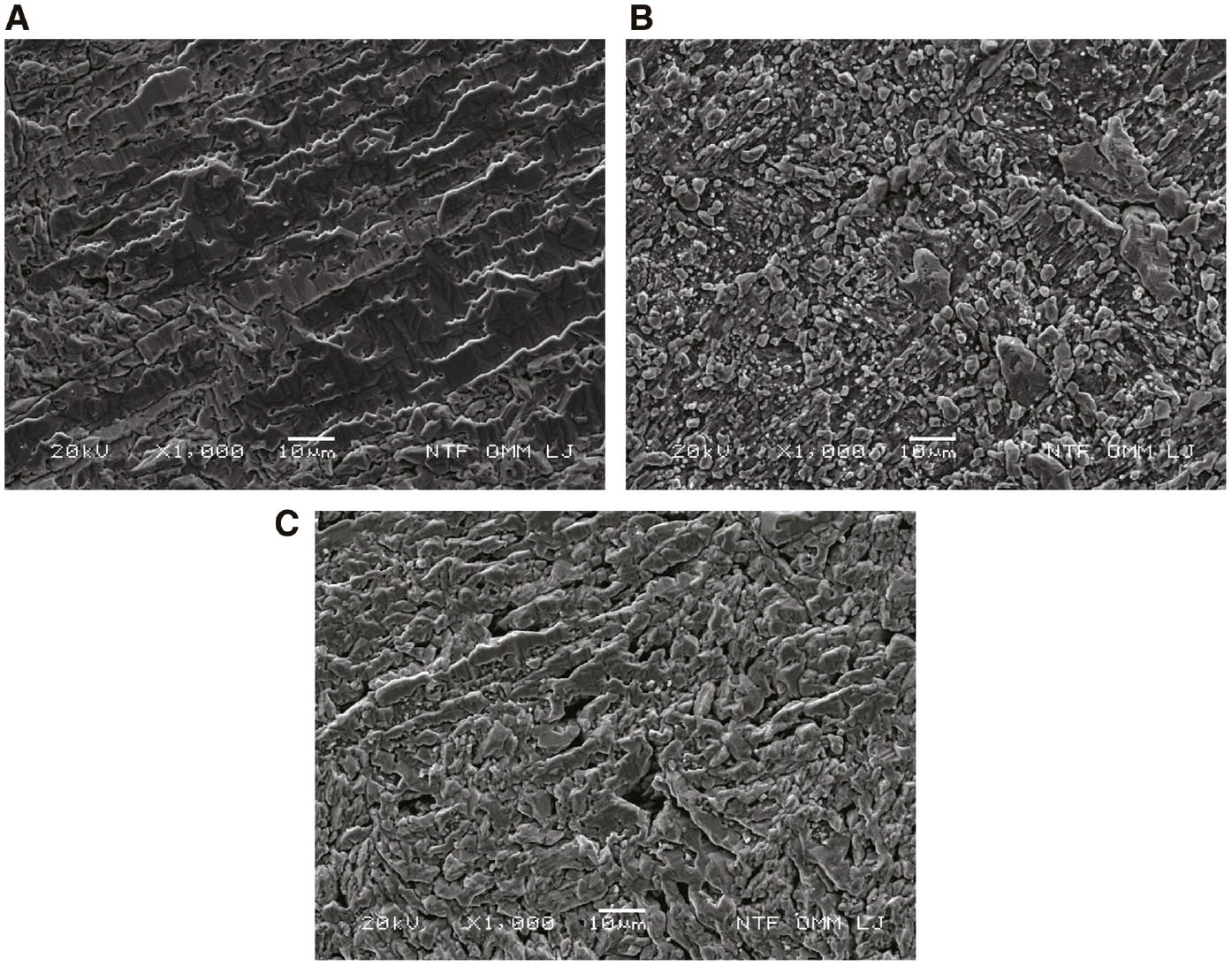

Figure 5 shows SEM micrographs of the Cu-Al-Mn alloy after continuous casting and applied heat treatment procedure. The microstructure in as-cast state (Figure 5A) is significantly different in regard to the microstructure after annealing and ageing (Figure 5B, C). It can be noticed that a two-phase microstructure (probably residual β phase along with martensite phase) appears in Cu-Al-Mn alloy after casting.

SEM micrographs of Cu-Al-Mn shape memory alloy in as-cast condition (A), after annealing at 900°C/30′ (B) and after aging at 300°C/60′ (C).

After heat treatment, the samples contain only the martensite microstructure (Figure 5B, C). By rapid cooling, the alloy undergoes ordering transitions β(A2)→β2(B2)→β1(L21), followed by martensite transformation β1(L21)→β1′ (Jiao et al., 2010). The martensite microstructure after aging (Figure 5C) forms as the completely needle-like shape martensite, whereas after annealing in some fields, the V-shape martensite was noticed. Self-accommodating zigzag martensite morphology is characteristic for the β1′ martensite in shape memory alloys.

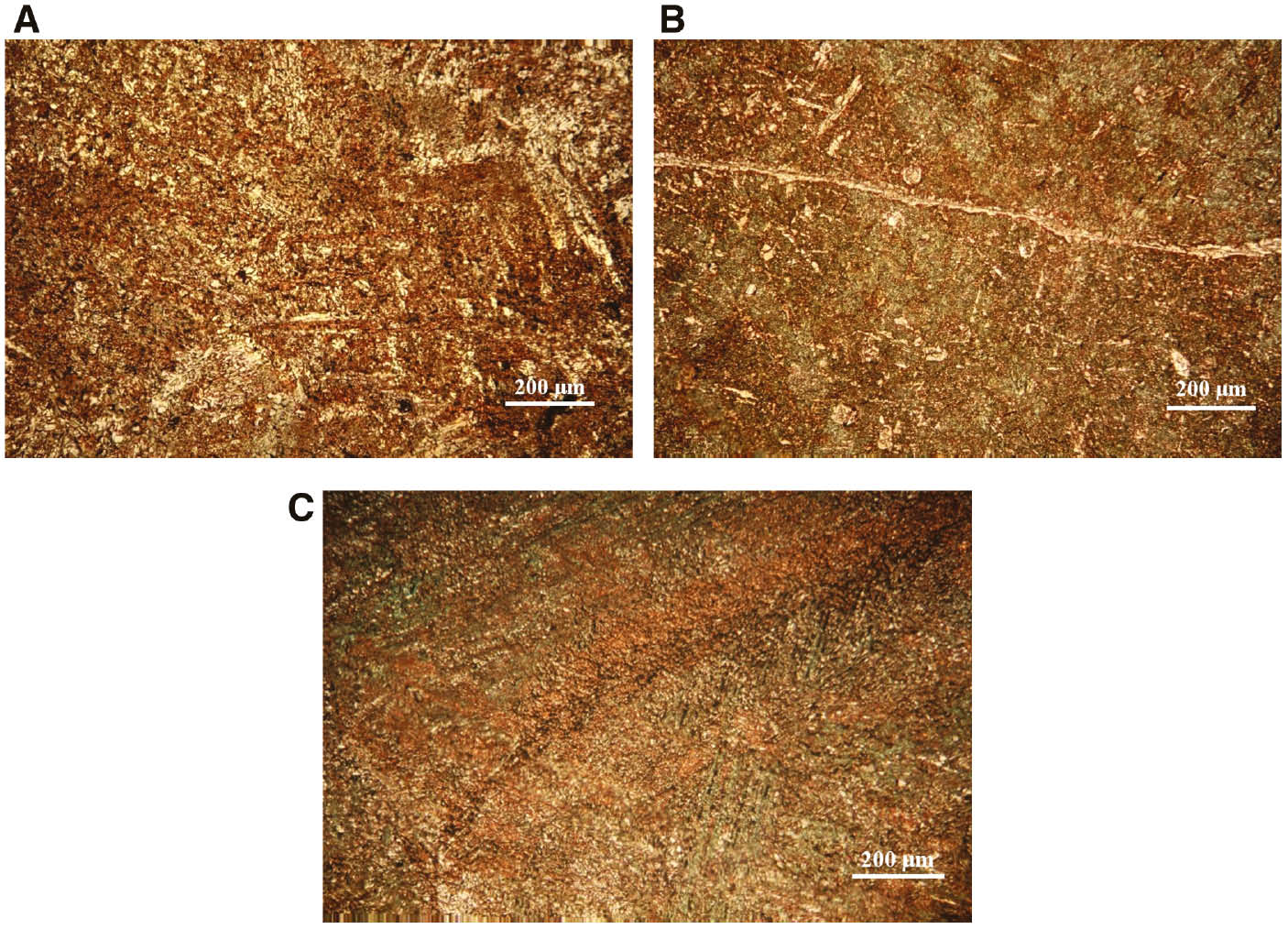

After the polarisation measurements, the CuAlMn electrode surface were ultrasonically treated in deionised water, dried in a desiccator and examined by optical microscopy at a magnification of 100 to determine the surface condition (Figure 6).

Microscopic surface images of CuAlMn alloy after potentiodynamic polarisation measurement in 0.1% NaCl solution: (A) as-cast, (B) annealed and (C) annealed and aged state, with magnification of 200 times.

The rough surface of the CuAlMn alloy can be seen in microscopic images that are due to corrosion processes, and heat-treated samples of CuAlMn alloys do not show significant differences in the appearance of corroded surfaces. The appearance of a corroded alloy surface does not indicate the existence of pitting corrosion, which was a characteristic corrosion phenomena for CuAlNi alloy in similar corrosion investigations (Kear et al., 2004; Vrsalović et al., 2018). Instead of that, general corrosion seems to be a dominant corrosion type for the investigated CuAlMn alloy.

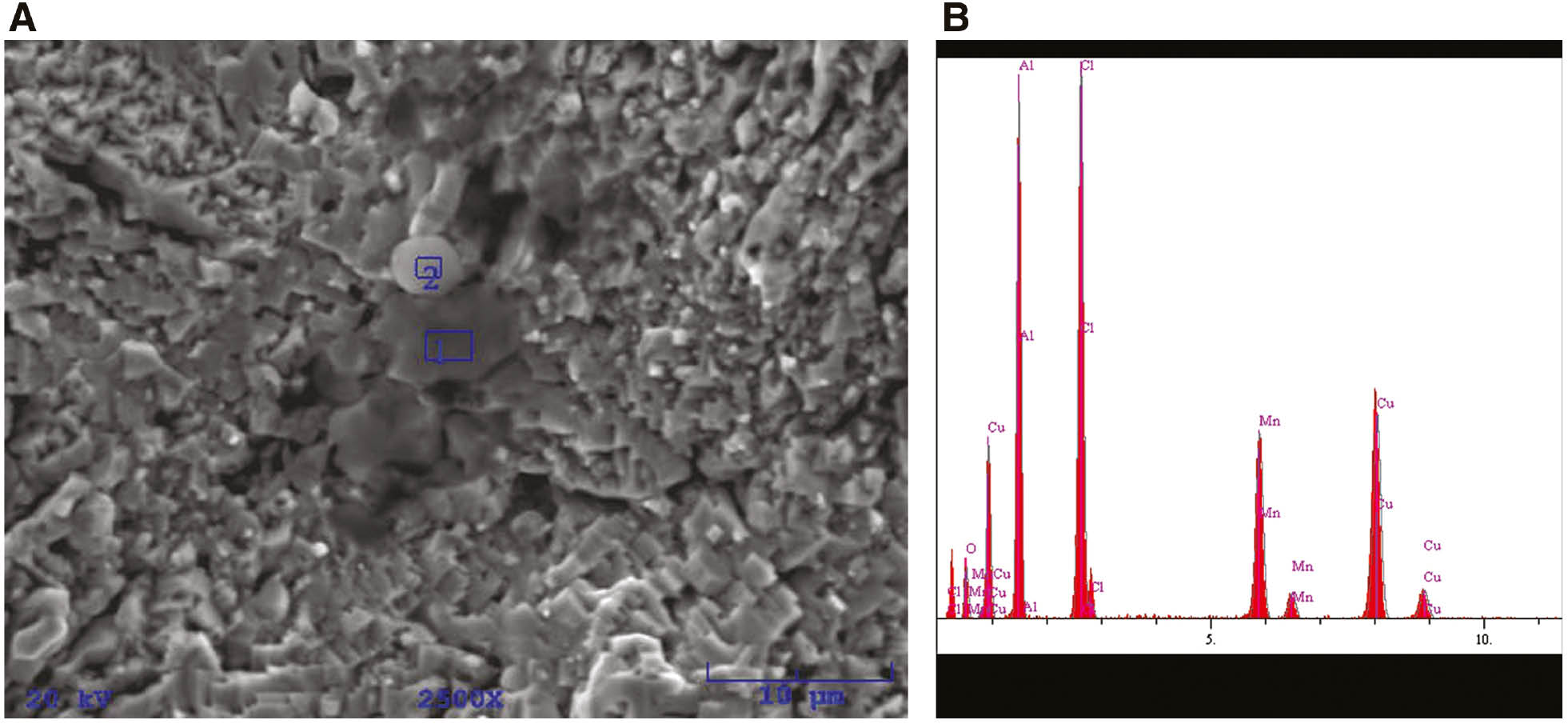

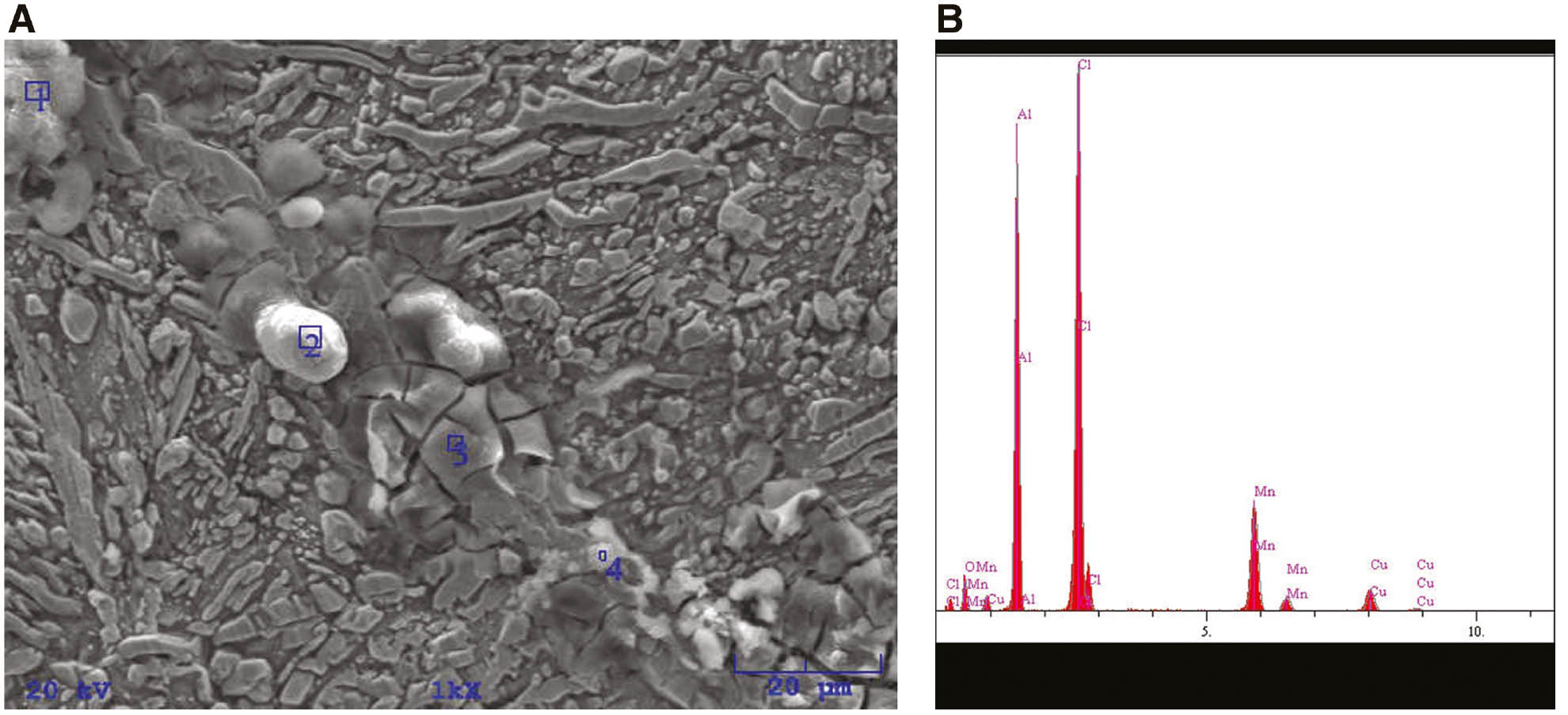

Detailed investigations of the alloy surface morphology after corrosion measurements were performed with SEM/EDS analysis, and the results were presented in Figures 7–9 and Tables 3 and 4.

SEM surface images of CuAlMn alloy after potentiodynamic polarisation measurement in 0.1% NaCl solution: (A) as-cast, (B) annealed and (C) annealed and aged state.

(A) SEM images of as-cast CuAlMn alloy after potentiodynamic polarisation measurements in 0.9% NaCl solution (pH=7.4, T=37°C) and (B) EDS analysis for position 2.

(A) SEM images of annealed CuAlMn alloy after potentiodynamic polarisation measurements in 0.9% NaCl solution (pH=7.4, T=37°C) and (B) EDS analysis for position 1.

EDS analysis of the chemical composition of the corrosion surface layers on the CuAlMn alloy as-cast state, wt.%.

| Element | Position 1 |

Position 2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | at.% | wt.% | at.% | |

| O | 1.62 | 4.96 | 5.00 | 12.38 |

| Al | 11.23 | 20.43 | 20.76 | 30.45 |

| Cl | 9.44 | 13.06 | 19.10 | 21.33 |

| Mn | 12.55 | 11.201 | 15.28 | 11.01 |

| Cu | 65.17 | 50.33 | 39.86 | 24.83 |

EDS analysis of the chemical composition of the corrosion surface layers on the annealed CuAlMn alloy, wt.%.

| Element | Position 1 |

Position 2 |

Position 3 |

Position 4 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | at.% | wt.% | at.% | wt.% | at.% | wt.% | at.% | |

| O | 8.39 | 17.17 | 10.84 | 21.41 | 2.87 | 6.92 | 3.88 | 9.41 |

| Al | 27.10 | 32.86 | 26.98 | 31.58 | 17.18 | 24.57 | 15.92 | 22.89 |

| Cl | 37.26 | 34.39 | 37.09 | 33.04 | 36.53 | 39.75 | 33.33 | 36.48 |

| Mn | 19.10 | 11.38 | 19.31 | 11.10 | 25.29 | 17.76 | 27.09 | 19.14 |

| Cu | 8.15 | 4.20 | 5.78 | 2.87 | 18.12 | 11.00 | 19.77 | 12.07 |

From Figures 7–9, it is apparent that high anodic polarisation (up to 1.5 V) results in significant damage to the electrode surface. The cracked layers of corrosion products with heterogeneous structures are clearly visible on the surface of the electrode, as well as cracks and ruptures formed by their dissolution. The appearance of corrosion products varies depending on the heat treatment, which indicates its different chemical composition. Elemental analysis at specific points on the surface by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy has showed that the corrosion products consist mainly of aluminium and manganese oxides and chlorides, the percentage of which differs depending on the site where the analysis was performed. Significantly lower copper content on the surface was found on the surface of the heat-treated CuAlMn alloy sample compared with the surface of the as-cast CuAlMn alloy (Tables 3 and 4), which suggests the formation of a thicker layer of Al and Mn oxides on the heat-treated alloy.

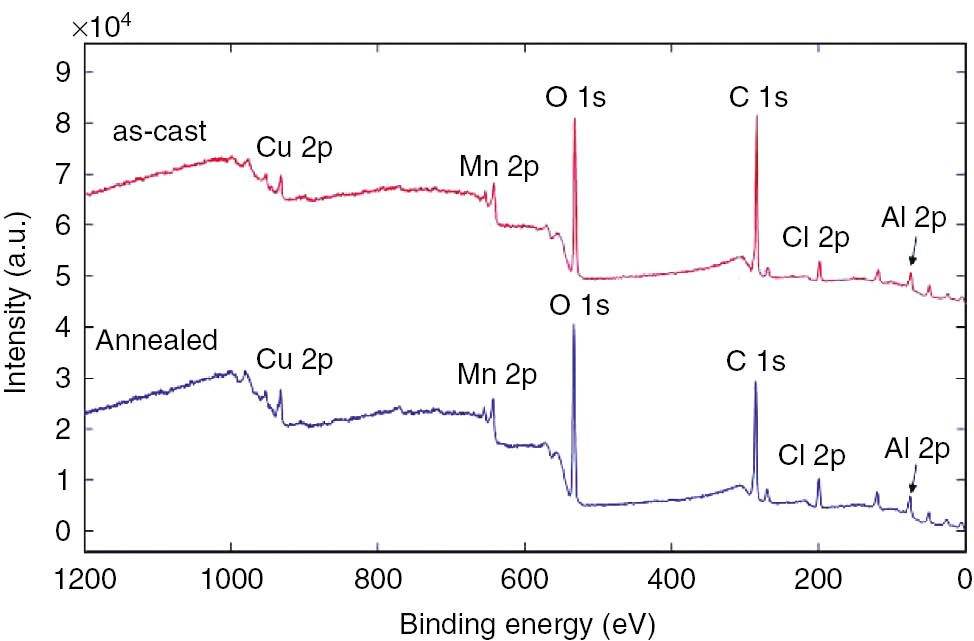

In order to get more precise insight into the surface chemistry, we performed XPS analyses on surfaces of the as-cast and annealed samples. The XPS method is very surface sensitive as the information about chemical composition and oxidation states originates from the 3–5 nm thick surface layer. This is much less than by the EDS method where the analyses depth is about 1 μm. Figure 10 shows the wide energy XPS spectra obtained from the as-cast and annealed samples after corrosion test.

XPS survey spectra from the as-cast and annealed samples.

Both samples are similar and contain O 1s, C 1s, Cl 2p, Cu 2p, Mn 2p and Al 2p peaks. From the intensities of these peaks, the chemical composition was calculated, and it is given in Table 5. We did not take into account carbon as it usually originates from the surface contamination. From the data given in Table 5, it can be seen that the surface of corrosion products is enriched in Al and Mn with respect to Cu, which confirms similar EDS results. XPS results show that the most abundant metallic element on the surface is Al.

Chemical composition in at.% obtained by the XPS method from the 3–5 nm thick surface layer on as-cast and annealed samples.

| Element | As-cast | Annealed |

|---|---|---|

| O | 56.9 | 53.5 |

| Al | 26.6 | 28.7 |

| Cl | 6.6 | 8.1 |

| Mn | 7.3 | 6.4 |

| Cu | 2.5 | 3.2 |

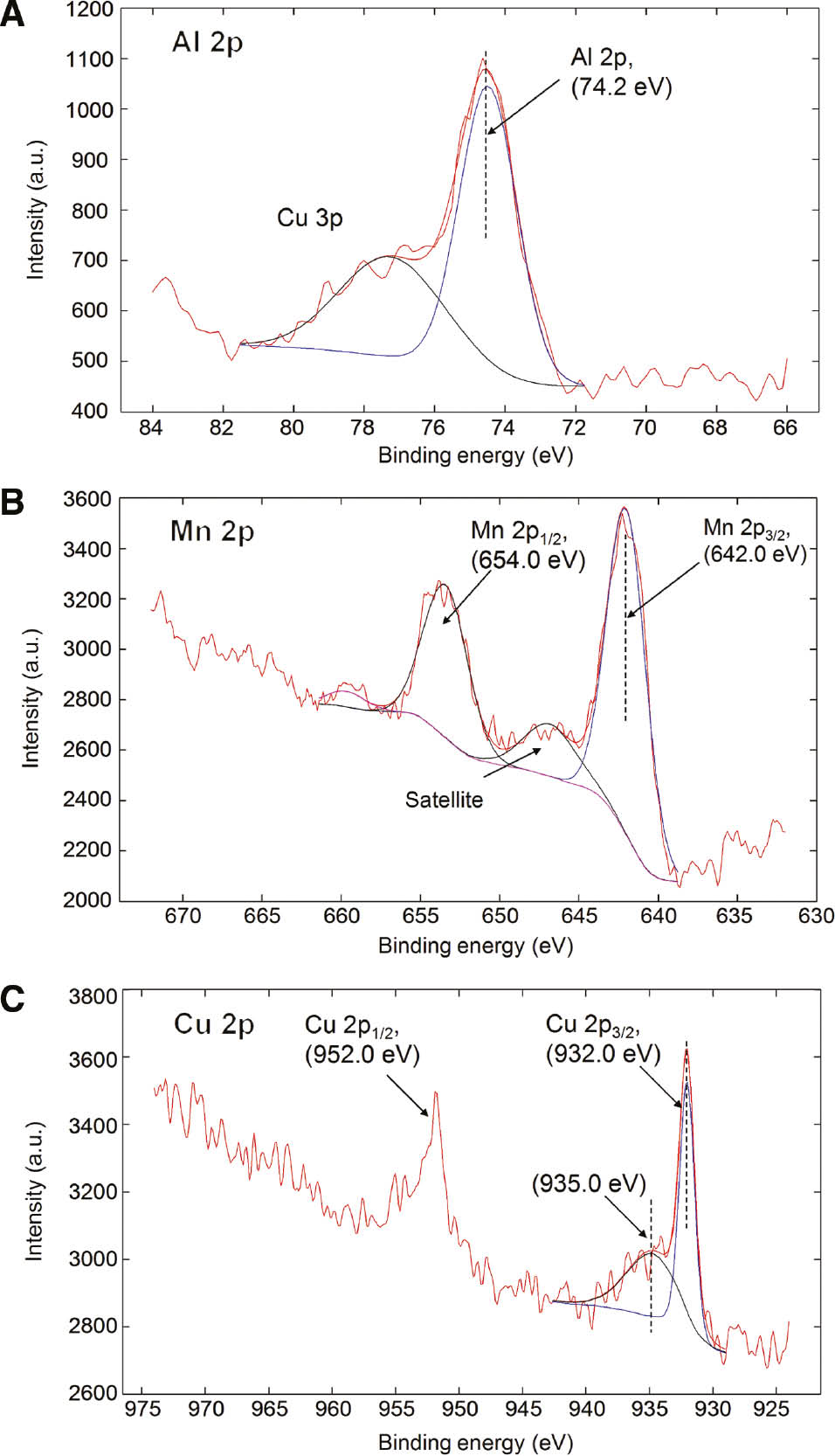

To reveal the oxidation states of elements on the surface, high-energy resolution XPS spectra were measured on the as-cast and annealed samples. Spectra from both samples were very similar. Therefore, the XPS spectra Al 2p, Mn 2p and Cu 2p from the as-cast sample are only given in Figure 11.

XPS high-energy resolution spectra Al 2p (A), Mn 2p (B) and Cu 2p (C) from the as-cast sample.

They were interpreted by help of reference Moulder et al. (1995). From Figure 10A, we can see that the Al 2p peak is at 74.2 eV, which can be assigned to the Al(3+) oxidation state in the surface of Al oxide. The Mn 2p peak (Figure 10B) is composed of a double peak. The main one Mn 2p3/2 is at 642.0 eV, and this may be assigned to MnO2 or MnCl2, which cannot be clearly distinguished by XPS method. The Cu 2p spectrum (Figure 10C) consists of Cu 2p3/2 peak and Cu 2p1/2 peak separated by 19.9 eV. A closer look at the Cu 2p3/2 peak of the as-cast sample reveals that it may be decomposed into two peaks at binding energy of 932.0 assigned to Cu2O and at 935 eV assigned to CuCl. In both cases, Cu atoms are in the Cu(1+) oxidation state. The absence of satellite peak at 945 eV in the Cu 2p spectrum means that no or very little amount of Cu(2+) oxidation state is present.

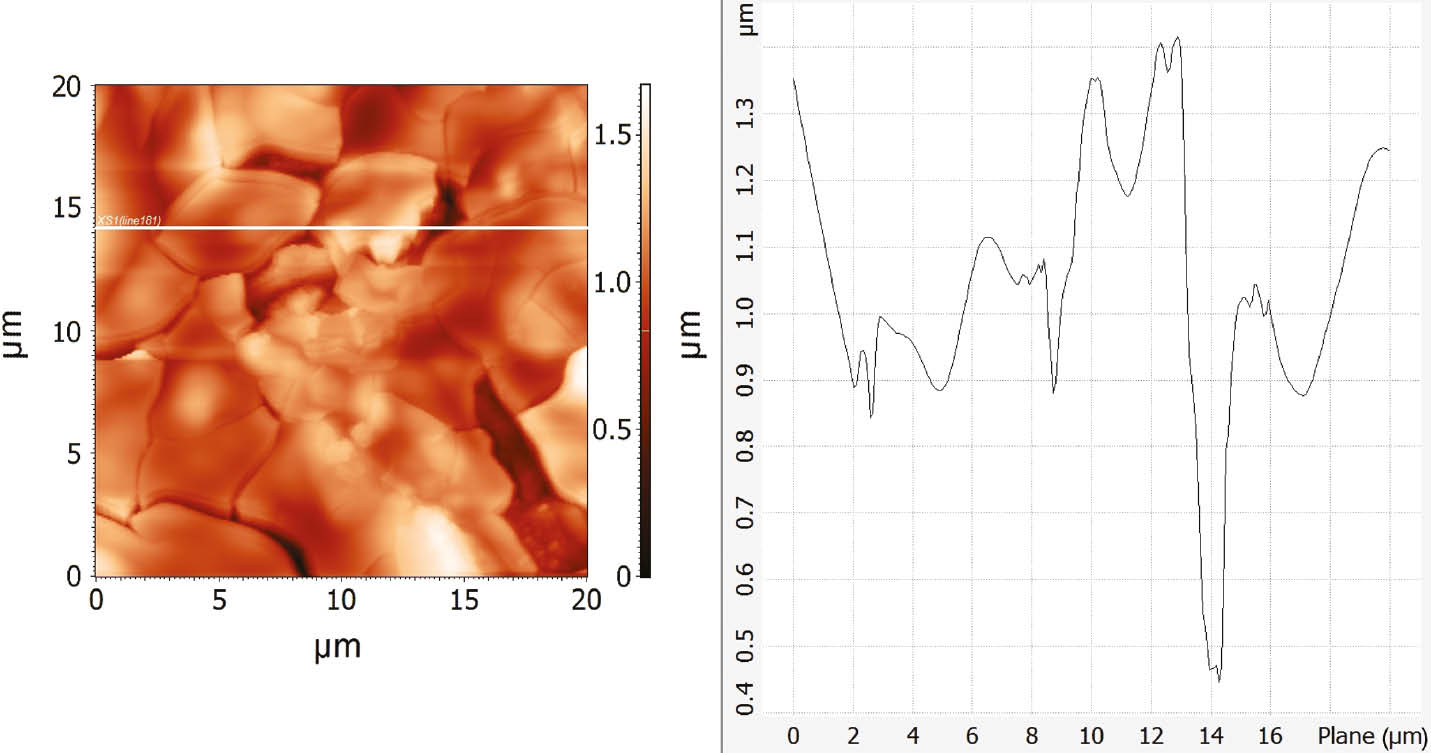

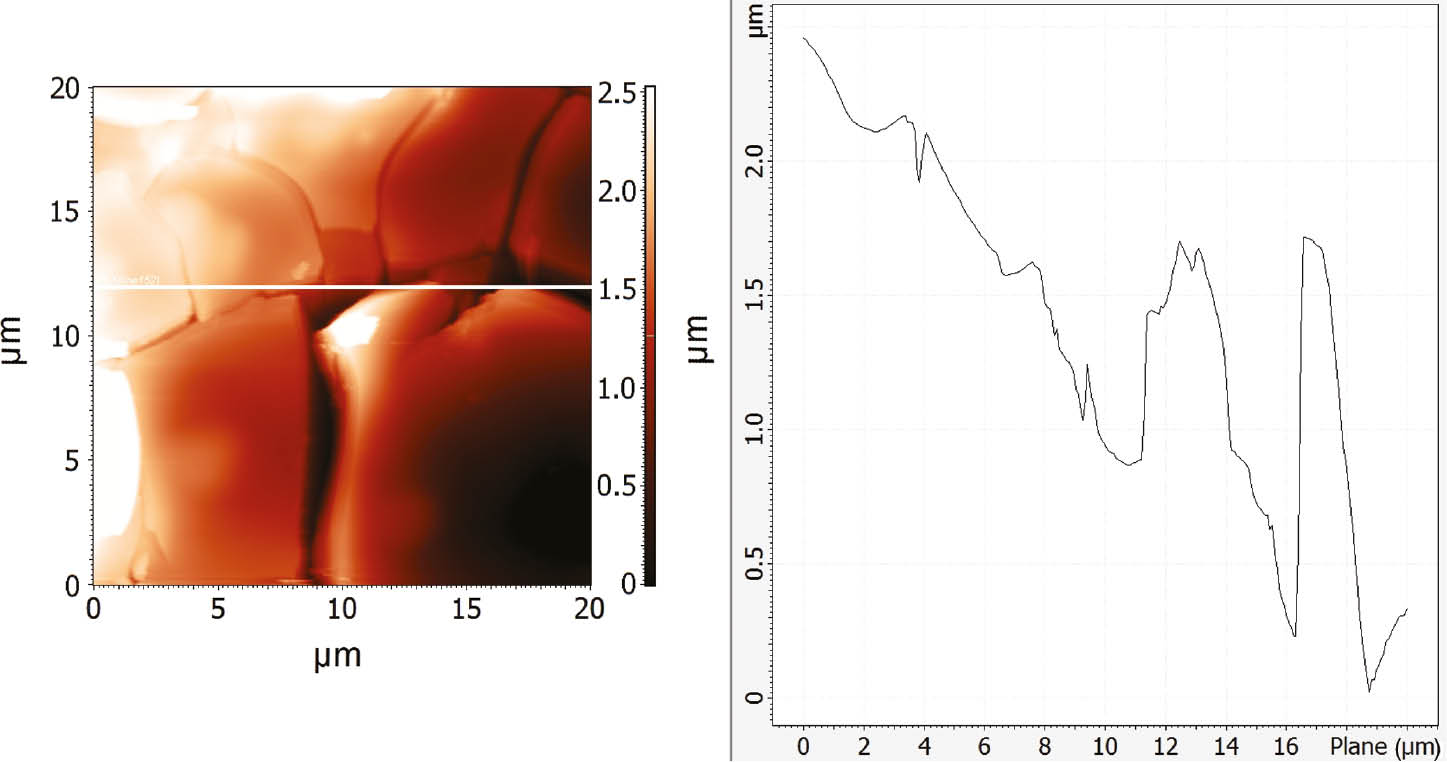

AFM surface analysis was performed on CuAlMn alloy samples (as-cast and annealed state) after potentiodynamic polarisation measurements in 1.5 mol dm−3 NaCl solution. Before analysis, alloy samples were ultrasonically treated in deionised water and dried in a desiccator identical to the samples for the SEM/EDS analysis. The results of the investigations were presented in Figures 12 and 13.

AFM images of as-cast CuAlMn alloy surface after polarisation measurements in 1.5 mol dm−3 NaCl solution and its roughness determined by line profile across the surface.

AFM images of annealed CuAlMn alloy surface after polarisation measurements in 1.5 mol dm−3 NaCl solution and its roughness determined by line profile across the surface.

AFM analysis revealed significant roughness and cracks on the alloy surfaces due to intensive corrosion processes. The cracks between the flat regions are about 1 μm deep. Deeper cracks were observed on the annealed samples, which can be attributed to a somewhat thicker layer of aluminium and manganese oxide on the surface, which is cracked and partially dissolved because of intensive corrosion process in higher chloride concentration.

4 Conclusions

From the observed difference in the microstructure, showing residual β phase in the as-cast state sample along with martensite matrix, and different types of martensite plates in annealed and aged sample, it can be concluded that the formation of the martensite in the samples after heat treatment improves alloy corrosion properties.

Heat-treated CuAlMn alloy samples exhibit slightly more positive values of open circuit potential, higher values of polarisation resistance and lower values of corrosion current density, which indicates positive effects of heat treatment on the corrosion resistance of the CuAlMn alloy. Increasing chloride ion concentration leads to polarisation resistance values decrease and corrosion current density increase, while open circuit potential takes more negative values, because of higher corrosion attack on the alloy surface.

On the microscopic images of the surface, after the polarisation measurements, the rough surface of the electrode can be seen that is due to corrosion processes. Increasing the electrolyte concentration leads to an increase in electrode surface damage.

The cracked layers of corrosion products are clearly visible on the SEM and AFM surface images, as well as cracks and ruptures formed by alloy dissolution. Elemental analysis at specific points on the surface by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy has showed that the corrosion products consist mainly of aluminium and manganese oxides and chlorides, the percentage of which differs depending on the site where the analysis was performed.

Funding

This work has been fully supported by the Croatian Science Foundation under the project IP-2014-09-3405.

References

Adachi K, Shoji K, Hamada Y. Formation of (X) phases and origin of grain refinement effect in Cu-Al-Ni shape memory alloys added with titanium. ISIJ Int 1989; 29: 378–387.10.2355/isijinternational.29.378Search in Google Scholar

Alaneme KK, Okotete EA, Bodunrin MO. Microstructural analysis and corrosion behaviour of Fe, B, and Fe-B-modified Cu-Zn-Al shape memory alloys. Corros Rev 2017; 35: 3–11.10.1515/corrrev-2016-0053Search in Google Scholar

Al-Haidary JT, Mustafa AM, Hamza AA. Effect of heat treatment of Cu-Al-Be shape memory alloy on microstructure, shape memory effect and hardness. J Mater Sci Eng 2017; 6: 398.10.4172/2169-0022.1000398Search in Google Scholar

Benedetti AV, Sumodjo PTA, Nobe K, Cabot PL, Proud WG. Electrochemical studies of copper, copper-aluminium and copper-aluminium-silver alloys: impedance results in 0.5 M NaCl. Electrochim Acta 1995; 40: 2657–2668.10.1016/0013-4686(95)00108-QSearch in Google Scholar

Bogue R. Shape memory materials: a review of technology and applications. Assembly Autom 2009; 29: 214–219.10.1108/01445150910972895Search in Google Scholar

Dagdelen F, Gokhan T, Aydogdu A, Aydogdu Y, Adiguzel O. Effects on thermal treatments on transformation behaviour in shape memory alloys. Mater Lett 2003; 57: 1079–1085.10.1016/S0167-577X(02)00934-5Search in Google Scholar

Dasgupta R. A look into Cu-based shape memory alloys: present scenario and future prospects. J Mater Res 2014; 29: 1681–1698.10.1557/jmr.2014.189Search in Google Scholar

Gojić M, Vrsalović L, Kožuh S, Kneissl A, Anžel I, Gudić S, Kosec B, Kliškić M. Electrochemical and microstructural study of the Cu-Al-Ni shape memory alloy. J Alloys Compd 2011; 509: 9782–9790.10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.07.107Search in Google Scholar

Gomez de Salazar JM, Soria A, Barrena MI. Corrosion behavior of Cu-based shape memory alloys, diffusion bonded. J Alloys Compd 2005; 387: 109–114.10.1016/j.jallcom.2004.06.028Search in Google Scholar

Ivanić I, Kožuh S, Kosel F, Kosec B, Anžel I, Bizjak M, Gojić M. The influence of heat treatment on fracture morphology of the CuAlNi shape memory alloy. Eng Fail Anal 2017; 77: 85–92.10.1016/j.engfailanal.2017.02.020Search in Google Scholar

Jain AK, Hussain S, Kumar P, Pandey A, Dasgupta R. Effect of varying Al/Mn ratio on phase transformation in Cu-Al-Mn shape memory alloys. Trans Indian Inst Met 2016; 69: 1289–1295.10.1007/s12666-015-0689-3Search in Google Scholar

Jiao YQ, Wen YH, Li N, He JQ, Teng J. Effect of solution treatment on damping capacity and shape memory effect of a CuAlMn alloy. J Alloys Comp 2010; 491: 627–630.10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.11.026Search in Google Scholar

Kear G, Barker BD, Walsh FC. Electrochemical corrosion of unalloyed copper in chloride media – a critical review. Corros Sci 2004; 46: 109–135.10.1016/S0010-938X(02)00257-3Search in Google Scholar

Kožuh S, Vrsalović L, Gojić M, Gudić S, Kosec B. Comparison of the corrosion behavior and surface morphology of NiTi alloy and stainless steels in sodium chloride solution. J Min Metall Sect B-Metall 2016; 52B: 53–61.10.2298/JMMB150129003KSearch in Google Scholar

Lagoudas DC. Shape memory alloys, modeling and engineering applications, New York: Springer, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

Lai MO, Lu L, Lee WH. Influence of heat treatment on properties of copper-based shape memory alloy. J Mater Sci 1996; 31: 1537–1543.10.1007/BF00357862Search in Google Scholar

Lojen G, Anžel I, Knissl A, Križman A, Unterweger E, Kosec B, Bizjak M. Microstructure of rapidly solidified Cu-Al-Ni shape memory alloy ribbons. J Mater Process Technol 2005; 162–163: 220–229.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2005.02.196Search in Google Scholar

Mikova L, Medvecka-Benova S, Kelemen M, Trebuna F, Virgala I. Application of shape memory alloy (SMA) as actuator. METABK 2015; 54: 169–172.Search in Google Scholar

Moghaddam AO, Ketabchi M, Bahrami R. Kinetic grain growth, shape memory and corrosion behavior of two Cu-based shape memory alloys after thermomechanical treatment. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China 2013; 23: 2896–2904.10.1016/S1003-6326(13)62812-5Search in Google Scholar

Morris MA, Gunter S. Effect of heat treatment and thermal cycling on transformation temperatures of ductile Cu-Al-Ni-Mn-B alloys. Scripta Metall Mater 1992; 26: 1663–1668.10.1016/0956-716X(92)90530-RSearch in Google Scholar

Moulder JF, Stickle WF, Sobol PE, Bomben KD. Handbook of X-Ray photoelectron apectroscopy, Eden Prairie, MN: Physical Electronics Inc., 1995.Search in Google Scholar

Pound BG. Corrosion behavior of metallic materials in biomedical applications. I. Ti and its alloys. Corros Rev 2014; 32: 1–20.10.1515/corrrev-2014-0007Search in Google Scholar

Sampath V. Studies on the effect of grain refinement and thermal processing on shape memory characteristics of Cu-Al-Ni alloys. Smart Mater Struct 2005; 14: S253–S260.10.1088/0964-1726/14/5/013Search in Google Scholar

Sathish S, Mallik US, Raju TN. Microstructure and shape memory effect of Cu-Zn-Ni shape memory alloys. JMMCE 2014; 2: 71–77.10.4236/jmmce.2014.22011Search in Google Scholar

Saud SN, Hamzah E, Abubakar T, Bakhsheshi-Rad HR. Correlation of microstructural and corrosion characteristics of quaternary shape memory alloys Cu-Al-Ni-X (X=Mn or Ti). Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China 2015a; 25: 1158–1170.10.1016/S1003-6326(15)63711-6Search in Google Scholar

Saud SN, Hamzah E, Abubakar T, Bakhsheshi-Rad HR. Microstructure and corrosion properties of Cu-Al-Ni shape memory alloys with Ag nanoparticles. Mater Corros 2015b; 66: 527–534.10.1002/maco.201407658Search in Google Scholar

Sreekumar M, Nagarajan T, Singaperumal M. Critical review of current trends in shape memory alloy actuators for intelligent robots. Ind Robot 2007; 34: 285–294.10.1108/01439910710749609Search in Google Scholar

Sutou Y, Omori T, Yamauchi K, Ono N, Kainuma R, Ishida K. Effect of grain size and texture on pseudoelasticity in Cu-Al-Mn based shape memory alloy. Acta Mater 2005; 53: 4121–4133.10.1016/j.actamat.2005.05.013Search in Google Scholar

Vrsalović L, Ivanić I, Čudina D, Lokas L, Kožuh S, Gojić M. The influence of chloride ion concentration on the corrosion behavior of CuAlNi alloy. Teh Glas 2017; 11: 67–72.Search in Google Scholar

Vrsalović L, Ivanić I, Kožuh S, Gudić S, Kosec B, Gojić M. Effect of heat treatment on corrosion properties of CuAlNi shape memory alloy. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China 2018; 28: 1149–1156.10.1016/S1003-6326(18)64752-1Search in Google Scholar

Zheng YF, Zhang BB, Wang BL, Wang YB, Li L, Yang QB, Cui LS. Introduction of antibacterial function into biomedical TiNi shape memory alloy by addition of element Ag. Acta Biomater 2011; 7: 2758–2767.10.1016/j.actbio.2011.02.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Reviews

- An updated review on TiNi alloy for biomedical applications

- Severity of corrosion under insulation (CUI) to structures and strategies to detect it

- Original articles

- Corrosion protection performance of nano-TiO2-containing phosphate coatings obtained by anodic electrochemical treatment

- Influence of heat treatment on the corrosion properties of CuAlMn shape memory alloys

- Annual reviewer acknowledgement

- Reviewer acknowledgement Corrosion Reviews volume 37 (2019)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Reviews

- An updated review on TiNi alloy for biomedical applications

- Severity of corrosion under insulation (CUI) to structures and strategies to detect it

- Original articles

- Corrosion protection performance of nano-TiO2-containing phosphate coatings obtained by anodic electrochemical treatment

- Influence of heat treatment on the corrosion properties of CuAlMn shape memory alloys

- Annual reviewer acknowledgement

- Reviewer acknowledgement Corrosion Reviews volume 37 (2019)