Abstract

Graphene-based coating is an emerging field that focuses on developing advanced coatings by exploiting new generation materials with superior properties. Researchers are striving to develop coatings that are cost-effective, easy to prepare and highly effective by integrating graphene with a wide range of suitable materials for surface protection applications. In this critical review, different types of high performing graphene-based polymer composite coatings have been described for anticorrosion application. An in-depth survey on methods of preparation, coating application techniques and their influence on the corrosion behavior of coatings is presented briefly. Newly developed strategies to enhance the protection efficiency of graphene-polymer matrix coatings are also covered concisely. The authors hope that this review will assist prospective academicians and researchers in developing novel highly efficient graphene-based anticorrosion composite coatings for industrial applications.

1 Introduction

Corrosion is a serious practical problem, the effects of which can be observed as soon as a metal is put into service in an acidic or humid environment. To prevent premature metals degradation due to corrosion, researchers are finding new ways to tackle this menacing problem. With the considerable progress in anticorrosion technology, many modern corrosion preventive techniques are being developed to increase the lifespan of metals. Some of the latest improved methods used today to protect metals from corrosive environment include metal alloying with composite materials, application of corrosion inhibitors and protective coatings (Rezende et al., 2016). Protective coatings can be applied in the form of metal-based organic layers (Stratmann et al., 1994), oxide layers (Sieber et al., 2015), polymeric films (Lu et al., 1995), sacrificial metallic coatings (Gonçalves et al., 2011) and varnishes (Merkula et al., 1974). Diversified coatings have been developed with better anticorrosion properties by dispersing filler materials with special properties forming a composite such as hybrid coatings (Hammer et al., 2013), smart self-healing coatings (Abdullayev et al., 2013) and superhydrophobic coatings (El Dessouky et al., 2017). An interesting choice of researchers nowadays for enhancing the anticorrosion performance of anticorrosion coatings is to include carbon-based nanofillers such as carbon nanotubes and graphene.

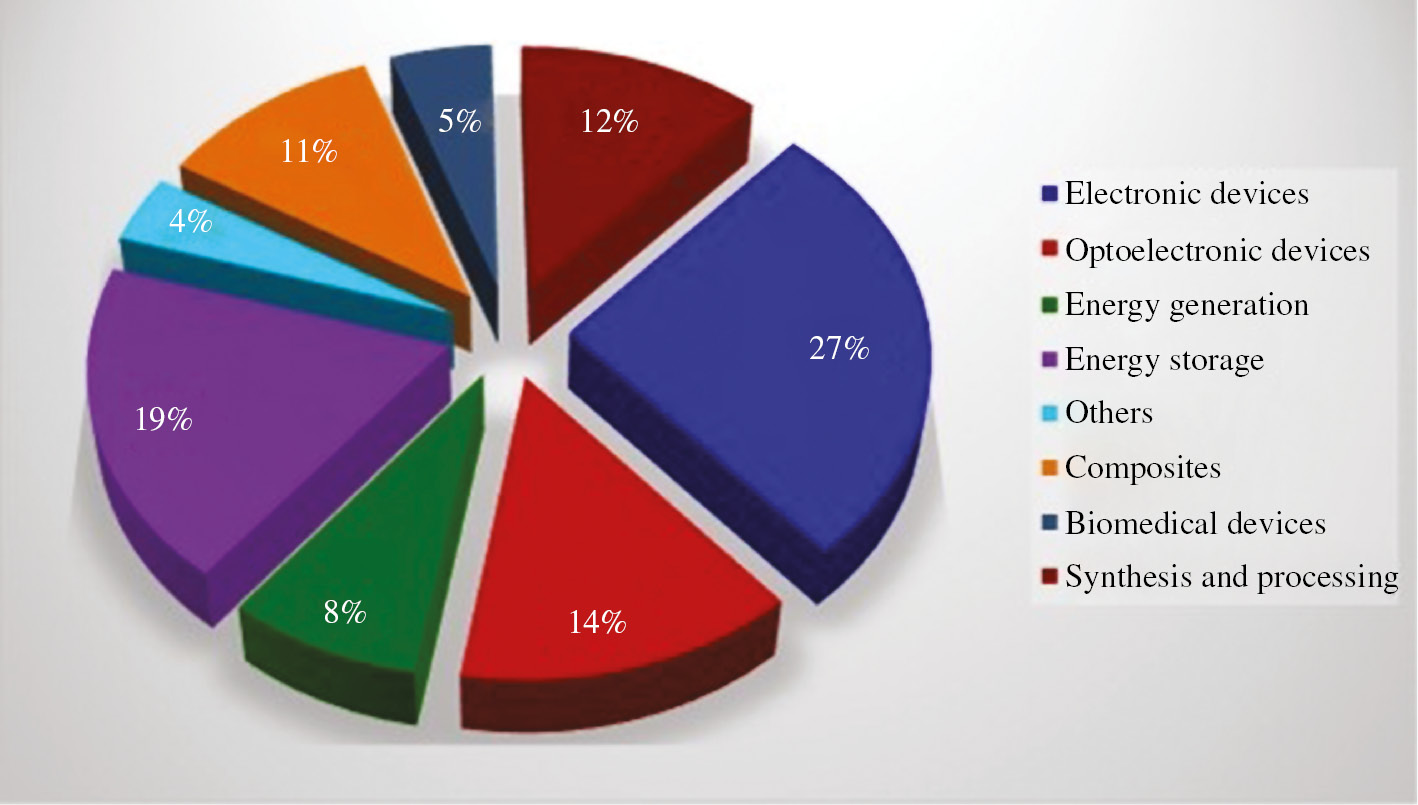

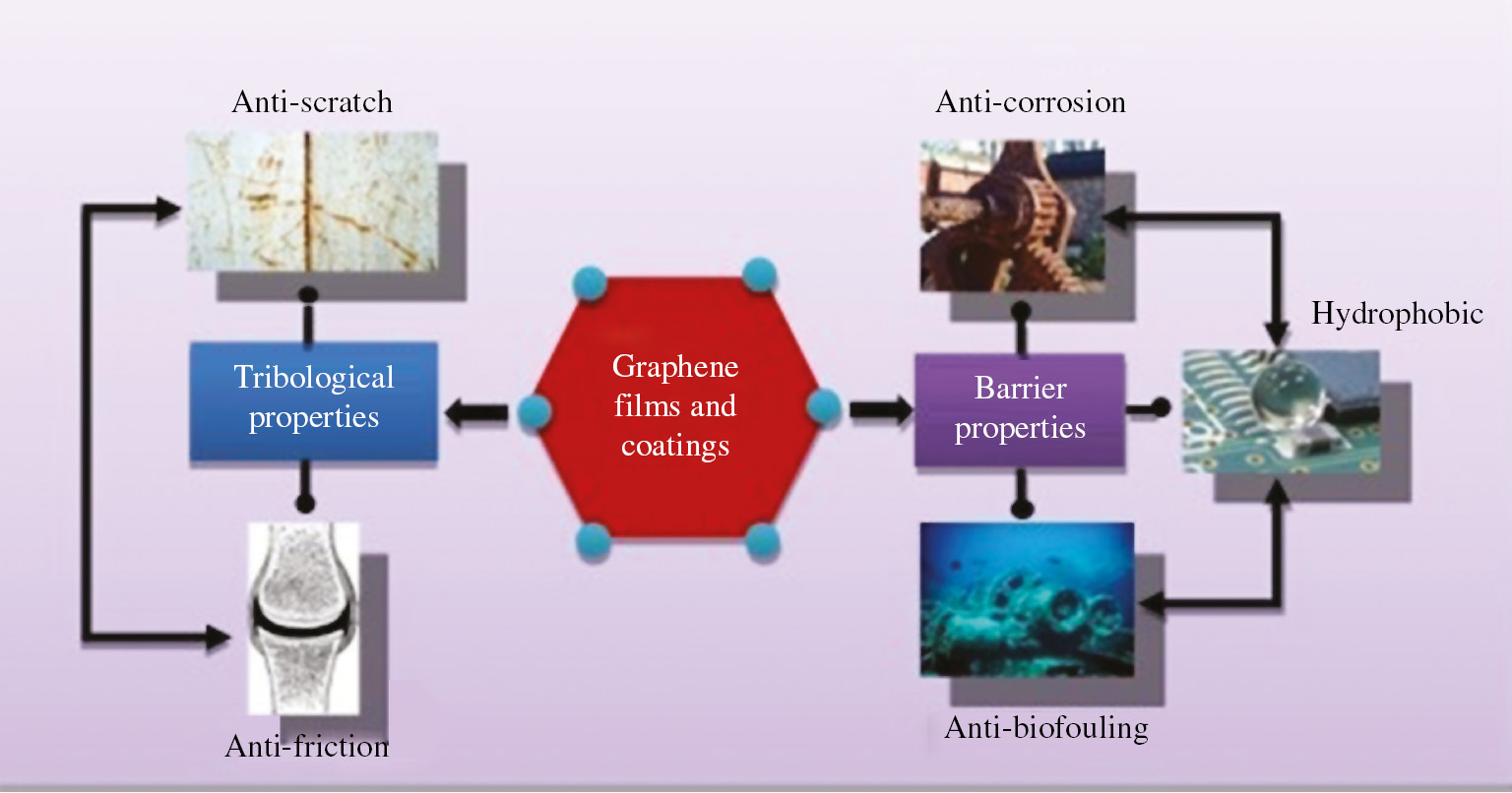

Graphene is a two-dimensional allotropic form of carbon consisting of a single layer of bonded carbon atoms with one atom thickness forming the hexagonal lattice structure. It is considered as a basic structural element of other allotropes of carbon structures, such as graphite, carbon nanotubes, fullerenes and charcoal with two-dimensional sp2 hybridized structure (Geim & Novoselov, 2007). Graphene is considered as a wonder material exhibiting extraordinary properties of highest strength over all materials ever tested (Shekhawat & Ritchie, 2016), enhanced thermal conductivity (Balandin et al., 2008), remarkable electronic properties (Neto et al., 2009), high optical transparency (Bonaccorso et al., 2010), large nonlinear diamagnetism (Yazyev, 2010) and impermeability (Berry, 2013). Figures 1 and 2 represent the percentage utilization of graphene in various sectors of engineering sciences and its applications in the field of films and coatings.

Graphical distribution on percentage utilization of graphene in different fields of engineering sciences.

Schematic diagram depicting properties and applications of graphene films and coatings.

Graphene also exhibits other unique properties, making it the most promising material for useful applications such as electrochemical energy storage (Raccichini et al., 2015), water purification (Han et al., 2013), supercapacitors (Tan & Lee, 2013), biomedical implants (Bitounis et al., 2013), gas sensing (Yuan & Shi, 2013) and protective thin films (Kirkland et al., 2012). Graphene can be synthesized in a variety of forms such as single layer/bilayer graphene films, graphene oxide (GO), graphene nanoplatelets and graphene nanoribbons by latest available techniques. Graphene nanoplatelets are increasingly used in preparation of composite materials by mixing with metals, ceramics and polymers to suit the properties for end applications. GNPs are made of small stacks of graphene that can be replaced with carbon nanotubes because it diffuses smoothly into the matrix material and less likely to twist and have high specific surface area, enhancing the final properties (Jang & Zhamu, 2008). The exceptional properties of graphene nanoribbons have wide variety of applications and are useful in novel nanocomposites, hi-tech batteries and supercapacitors, coatings and adhesives (Shen et al., 2015). Graphene nanoflakes have promising applications in the fields of electronics, optics and electrical engineering (Silva et al., 2010).

Graphene is a hydrophobic material (Singh et al., 2013c), whereas GO possesses hydrophilic property. This water-repellent property of graphene makes it suitable for preparation of water resistant films and advanced hybrid coatings (Romero Aburto et al., 2015). With the discovery of graphene, investigators are focusing their attention on developing pristine graphene-based ultrathin coatings that are impermeable to liquids and gas molecules without changing the properties of the base metal. Pure graphene coatings can be utilized as conductive coating for touch panel applications, cathode material in Li-ion batteries, energy storage applications and dye-sensitized solar cells for energy conversion applications (Tong et al., 2013). Generally, graphene is treated as a chemically inert material with dense lattice structure and have the ability to form single and multilayer coatings that act as natural diffusion barriers (Bunch et al., 2008). Prior to the isolation of graphene in 2004, excoriated or intercalated clays (Yeh et al., 2002) and fullerene (Jayatissa et al., 2005) materials were applied as coatings for anticorrosion applications. Because of their insulating and hydrophilic properties, these materials are not suitable for impeding corrosion. These fully insulated coatings promote accelerated corrosion by moisture that enters through the defects and suppresses the anticorrosion behavior on metals (Advincula, 2015). Large surface area and high electrical conductivity of graphene imparts favorable effects on barrier performance of the coatings composed. Anticorrosion mechanism of pristine graphene coatings can be exemplified as the combination of three actions: (1) by preventing electrons generated at anodic sites from reaching cathodic sites by providing alternative paths, (2) by forming an impermeable passive layer of graphene on the surface of metal, (3). By making the path of corrosive elements more tortuous to reach the graphene-metal interface (Böhm, 2014).

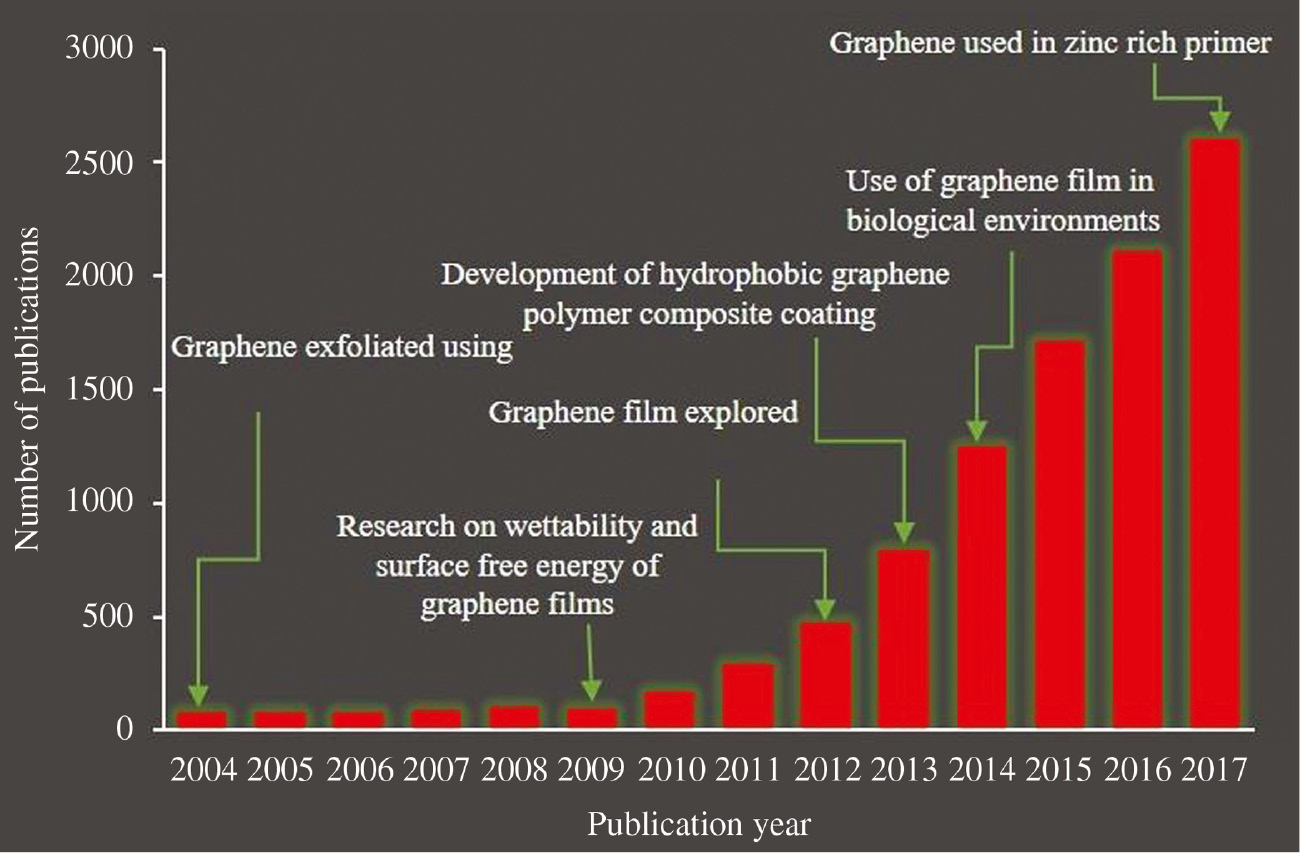

Many pioneering investigations have proved that graphene and graphene derivatives such as functionalized graphene, graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide in the form of coatings can effectively decouple the metal surface from the surrounding environment, thus protecting it from corrosion, oxidation (Kang et al., 2012b) and hydrogen embrittlement (Nam et al., 2014). Defectless graphene nanosheets are highly inert in nature and flocculates when mixed with other matrix materials because of strong vander Waals forces, thus affecting the final properties of the coatings. To eliminate this phenomenon, graphene is often functionalized with chemicals or metallic nanoparticles that increase that dispersibility and interfacial bonding with matrix materials (Kumar et al., 2012). Since the discovery of graphene, the research conducted on graphene coatings has gone up exponentially. According to the Web of Science 2017 database, there were approximately 8902 papers published alone on graphene coatings related topics. Figure 3 shows the timeline of publications related to graphene coatings since 2004.

Record of graphene coatings depicting number of research papers published since year 2004 (source: Web of Science, accessed on 09/02/2019).

While most of the reports published in the literature confirm that graphene is a promising anticorrosion material, most of the corrosion testing was carried in corrosive conditions at room temperature but for a short period of time. In real operating conditions, the graphene coatings actually promotes corrosion in the presence of defects in a long-term. The reason for this enhancement of corrosion is associated with the conductive nature of graphene that consequently enhances the localized galvanic corrosion. In the presence of graphene coating, the free electrons migrates from the metal substrate to the graphene/air interface, resulting in galvanic corrosion (Zhou et al., 2013). Furthermore, under the influence of low electrochemical potential, graphene films can also fail, leading to enhanced local galvanic corrosion at an accelerated rate at the graphene-metal interface (Ambrosi & Pumera, 2015). To mitigate these problems, graphene coatings must be made crack free and durable enough to resist scratches.

Although several review articles have been published on functional and smart composite coatings for different applications such as semiconductor device fabrication, wear resistance, gas sensing and antifouling (Nine et al., 2015a,b), only a few of them are designated comprehensively to corrosion-related issue particularly on coatings composed of graphene- or GO-based composite coatings. The objective of this review paper is to present extensive research advances and latest trends in the field of corrosion prevention by utilizing graphene as the reinforcement material in polymer coatings. The main highlights of this paper include the synthesis methods for graphene polymer composite coatings and their influence on the corrosion behavior of different metallic substrates. Detail discussions have been carried out on graphene-polymer matrix composites coatings and their protection mechanisms under different environmental conditions. Additionally, the latest strategies used to improve the performance of graphene-polymer matrix coatings are elaborated in a separate section. Comparison of electrochemical test results for different coating types is also presented along with the microstructure morphology for a better understanding of corrosion mechanisms.

2 Coatings for anticorrosion application

The role of the anticorrosion coating is to serve as a barrier between the corrosive electrolyte and the metal surface by inhibiting chemical compounds formed on the surface that promote corrosion. Because of disparities in the structural properties of metal and the coating layer characteristics, failure of coatings may occur, compromising its corrosion combating affect. Anticorrosion coatings prevent corrosion usually by one of the following mechanisms: (i) barrier protection, (ii) inhibition effect and (iii) sacrificial protection (Montemor, 2014). Barrier protection involves the prevention of corrosion by isolating the substrate from the corrosive environment by forming a thick layer. The efficiency of the barrier is largely affected by the thickness of the film, its composition and the presence of defects (Ates, 2016). In sacrificial protection, a metallic coating covers the substrate and safeguards it by depleting itself in an electrochemical cell. The ability of the metallic coating to sacrifice depends on the electronegativity or the electropositivity of the metal (Shreepathi et al., 2010). Corrosion inhibitors are metallic or nonmetallic materials added to the coating system that act as an additional corrosion protection above the barrier protection of the oxide layer.

Anticorrosion coatings can be synthesized from organic, inorganic, metallic or hybrid materials. Paints and other organic coatings such as lacquers, varnishes and polymer coatings are often employed to prevent metals from the deterioration in the presence of a corrosive environment by forming a barrier between the metal surface and its surrounding atmosphere. Common types of organic and inorganic coatings include epoxy coatings, acrylic coatings, urethane coatings and water-soluble coatings (Sørensen et al., 2009). Metallic coatings are commonly applied by vapor deposition (Hampden-Smith & Kodas, 1995), electrodeposition (Gomes & da Silva Pereira, 2006), hot dipping (Shibli et al., 2015) and metal cladding (Alfred, 1955) processes, but inorganic coatings are formed by chemical conversion (Zhao et al., 2001), thermal spraying (Katayama & Kuroda, 2013) or diffusion process (Vourlias et al., 2006). Porosity, flaking, cracks or any other defects on the coatings may result in accelerated localized galvanic corrosion on the base metal. Metallic and ceramic coatings although offer several advantages, some of them are extremely expensive and some are banned because of key environmental issues and health concerns. Furthermore, ceramic materials used in coatings are highly brittle and can ultimately fail, leading to a catastrophe (Priyantha et al., 2003). Most of the traditionally deployed protective coatings result in substantial increase in thickness and modification in electrical, mechanical and optical properties of the base metal.

The issues mentioned above necessitated the researchers to develop protective coatings with ultrafine thickness and minimal defects. During the last decade, remarkable advancement in the field of nanotechnology research led the investigators to fabricate novel hybrid nanocomposite coatings with superior anticorrosion properties. Newly fabricated hybrid coatings consisted of carbon nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes, carbon nanofibers and graphene with metals, ceramics or polymer as matrix material (Daneshvar-Fatah & Nasirpouri, 2014). These hybrid coatings have been proved to be more effective than coatings with a single material by combining all the three corrosion protection mechanisms, giving extra protection to the base against metal corrosion.

3 Graphene polymer matrix composite coatings (GPMCCs)

Economical sources of graphene and its outstanding properties have led the investigators to explore novel, high-performance and cost-effective graphene-polymer nanocomposite coatings with improved anticorrosion efficiency. Graphene nanosheets incorporated in polymer matrix give extra corrosion protection to metals by making it difficult for electrolyte molecules to penetrate through the defects of graphene due to the surrounding polymer phase. In addition to breaking the galvanic couple by preventing flow of electrons from the metal to graphene, mixing of nonconducting polymer (CP) with graphene also improves the mechanical and thermal properties of the metal substrate (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2014). Graphene-reinforced polymer nanocomposite system gives enhanced anticorrosion ability to coatings primarily because of the following protection mechanisms: (i) homogeneous distribution of polymer phase on the substrate’s surface resulting in the formation of smooth and uniform passive layer, (ii) limiting the penetration and providing tortuous diffusion path to the corrosive agents along the coating thickness and (iii) reformed mechanical strength to resist cracks and improved adhesion ability to the metal surface (Wang, 2018).

The resulting properties of the composite coatings depend on the composition and properties of the polymer matrix, coating deposition technique and how readily the graphene sheets are dispersed into the matrix to create a good network structure (Cui et al., 2016). Uniformly distributed graphene nanosheets suppress the corrosion process by restricting the flow of electrons to and from coating interface and preventing chain mobility in the matrix. Significant amount of research has been carried in the fabrication of graphene-reinforced polymer nanocomposite coatings by adding graphene in different synthetic polymer systems with electroactive or non-electroactive nature to generate unique mechanical and chemical properties for a variety of applications.

To prevent agglomeration, the graphene nanosheets are often dispersed in waterborne polymer matrices such as waterborne epoxy resin or sodium polyacrylate in aqueous solution (Liu et al., 2016). Epoxy coatings are used extensively for corrosion resistance applications due to their exemplary superior intrinsic toughness, stability at low and high temperatures, high adhesive ability onto various substrates and high chemical resistivity (Kang et al., 2012a). Nonetheless, the corrosion resistance ability of pristine epoxy coatings is compromised after exposure to water and oxygen molecules because of hydrolytic deterioration. Published reports prove that the inclusion of graphene nanosheets and its derivatives into epoxy coatings enhances its corrosion protection property. Graphene and GO nanosheets have been reported to be incorporated in an epoxy matrix by in situ polymerization method to form novel anticorrosion coatings. The addition of graphene and its derivative (GO) as filler material showed enhancement in corrosion resistance of the epoxy coatings, which was confirmed by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) spectrum results. These affirmative results were attributed to the fact that graphene/GO nanoplatelets possess large specific surface area and high aspect ratio, which makes diffusive path tortuous and difficult to permeate for corrosive agents. However, increased percentage of GO in epoxy reduced the anticorrosion performance because of agglomeration of GO nanosheets (Rajabi et al., 2015; Alhumade et al., 2016). Recently, Chang et al. (2014b) copied the properties of Xanthosoma sagittifolium leaves and synthesized graphene/epoxy composite coatings with hydrophobic surfaces as corrosion inhibitors on cold rolled steel substrates. The as-prepared hydrophobic surfaces exhibited increased water contact angle from 82° to 127° and provided excellent corrosion protection by forming a physical barrier and repelling moisture, which was predicted by the increase in impedance value of the coatings. However, this method of coating preparation is costly and complicated and difficult to be applied in practical applications.

Waterborne epoxy coatings are increasingly used for anticorrosion application because of its advantages of easy cleaning and strong adhesion to different types of metallic substrates. Monetta et al. (2017) examined exclusively the anticorrosion behavior of graphene waterborne epoxy composite coatings applied to aluminum samples. Hydrophobic and adhesion test results revealed that the addition of graphene nanosheets slightly enhanced the hydrophobic property of the coatings, whereas the adhesion ability was not affected much. Moreover, EIS measurements indicated that graphene loading had a positive impact on coatings and exhibited good corrosion protection of the metallic substrates. The superior anticorrosion performance of the coatings was correlated to the formation of a passive barrier and reduced water adsorption and transport through the filled epoxy coatings, which was confirmed by the high impedance modulus and capacitance values.

Embedding graphene into the polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) polymer gives corrosion-resistant coating by lessening the pin hole defects and forming strong bonds with the oxygen functional groups of graphene (Amini et al., 2016). Hikku et al. (2017) infused graphene nanoplatelets, whereas Zhang et al. (2017) used reduced graphene oxide (rGO) into the PVA matrix and formulated composite coatings with better corrosion-resistant properties. rGO-PVA coatings were synthesized by using a novel in situ reduction process in which GO-PVA mixture was thermally treated at a low temperature. Corrosion resistance of G/PVA and rGO/PVA as-prepared samples was evaluated using Tafel and Nyquist curves. EIS measurements showed that G/PVA nanocomposite coatings exhibited high and stable impedance value when exposed to a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, indicating high corrosion resistance. G/PVA-coated samples displayed better corrosion protection efficiency than rGO/PVA-coated samples because of the introduction of defects during the reduction process. However, this technique adopted to prepare rGO/PVA coatings is simple and feasible as compared with conventional rGO reduction techniques that require inert atmosphere and high temperatures.

Previous studies have shown that combining graphene with polyurethane (PU) may yield a novel coating with renewed anticorrosion properties. Huang et al. (2016) and Nuraje et al. (2013) formulated graphene/PU nanocomposite coatings by infusing graphene particles in PU matrix for improved weathering, corrosion and sound absorbing performances. The composed coatings exhibited relatively high impedance values, steep acoustic adsorption coefficient and sharp resistance against ultraviolet degradation, suggesting an improvement in anticorrosion and acoustic properties of the coating for underwater materials. However, the average final coating thickness for all samples was relatively high at approximately 100±20 μm. Similarly, (Singh et al., 2013a,b) improvised thin, sturdy and crack-free GO/isocyanate hybrid coatings with exceptional oxidation and corrosion resistance by electrophoretic deposition process. Preliminary corrosion test results confirmed the reduction of electrochemical degradation by three orders (25 Ω/cm2) of magnitudes compared with the uncoated substrate (8 Ω/cm2) with outstanding adhesion capability. To further improve the hydrophobic property, the coating was treated with silicone fluids to form a protective organic layer after the electrophoretic deposition process. The credible mechanism explained by the author for such a high corrosion resistance of GO/isocyanate-coated samples was connected to the enhanced wetting and formation of metal hydroxide during the electrodeposition process.

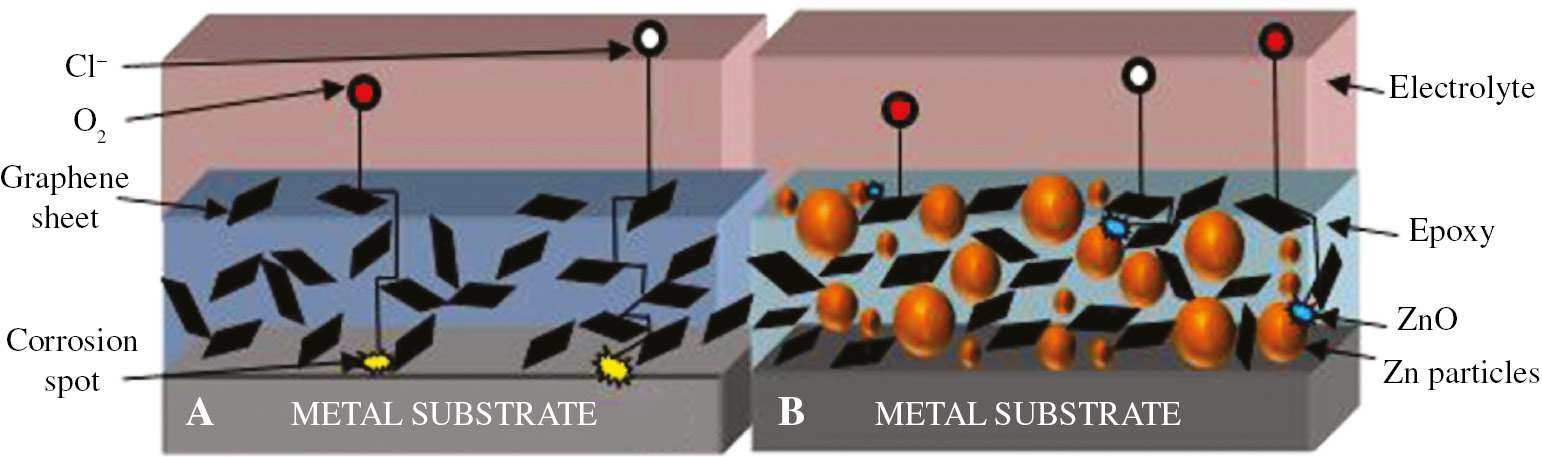

Nowadays, zinc-rich epoxy coatings (ZREC) are a widely studied topic among coating researchers because of its superior corrosion protection ability for a long period of time in harsh corrosive conditions and even after severe damage to coating layers. The corrosion protection mechanism involved in zinc-rich coatings is sacrificial cathodic protection, but with the passing time, protection efficiency decreases due to the decrease in coating porosity (Shreepathi et al., 2010). Several efforts have been made in the past to augment the efficiency of zinc-rich coatings by means of incorporation of different kinds of additives and nanofiller materials. Liu et al. (2018) reported the use of single-layer graphene nanosheets in ZREC to improve its barrier and cathodic protection efficiency. Only 0.4 wt% of the single-layer graphene was added to the zinc-rich epoxy resulting in the enhancement of anticorrosion properties, which were validated by open circuit potential and EIS measurements in terms of high polarization resistance values. Moreover, the coated samples were characterized by localized electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to prove the cathodic protection property. Figure 4A and B illustrate the corrosion protection mechanisms in graphene-reinforced epoxy and ZREC, respectively. The mechanism of zinc dissolution in the presence of NaCl solution can be explained as follows (Sørensen et al., 2009):

Schematic representation illustrating protection mechanism of (A) graphene-epoxy coating and (B) graphene-zinc rich epoxy coating exposed to electrolytic solution.

Zinc hydroxide after absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere converts into Zn5(CO3)2(OH)6 and zinc oxide according to the following reaction:

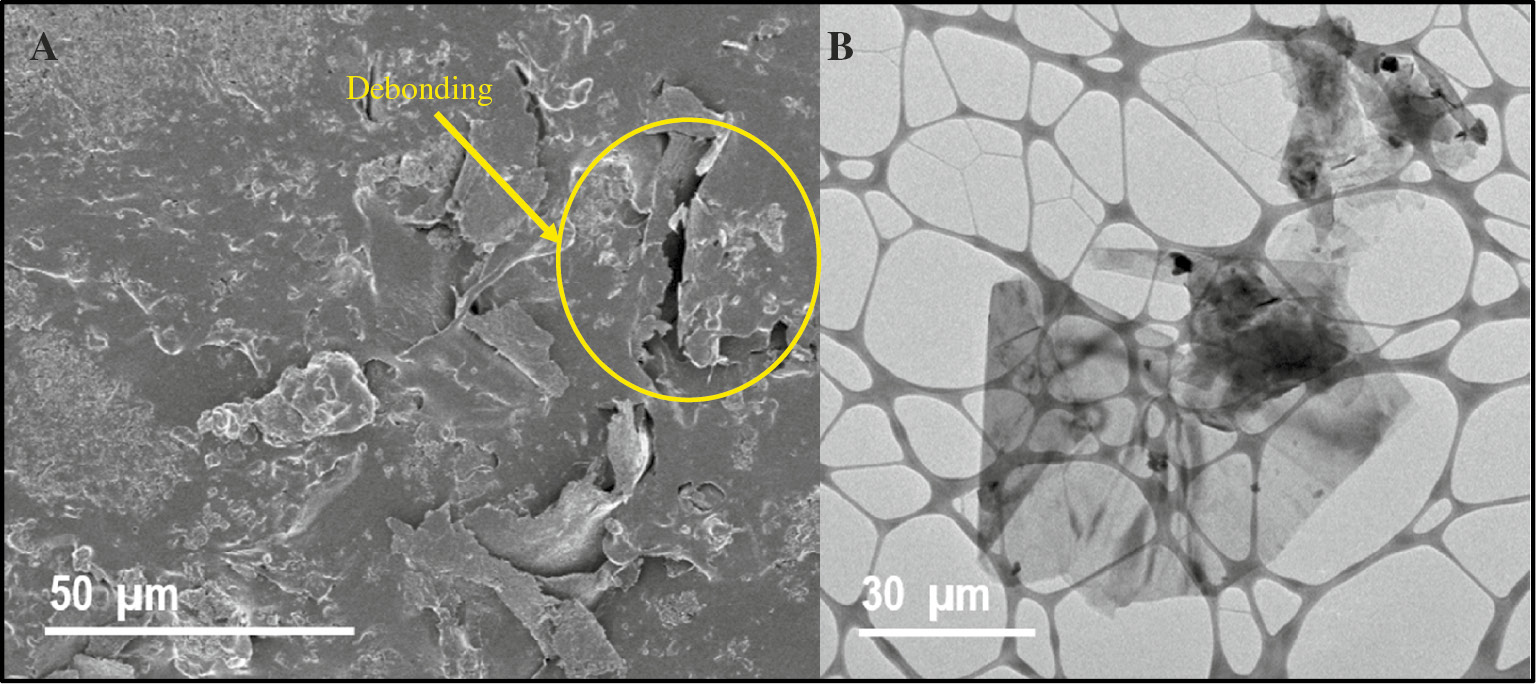

In a similar research work, Hayatdavoudi and Rahsepar (2017) lately reported a mechanistic study on the impact of a few-layered graphene nanosheets on the anticorrosion performance of a ZREC. Corrosion test results revealed that the introduction of just 0.4 wt% of graphene resulted in superior anticorrosion performance as compared with pristine ZREC. The enhanced corrosion protection mechanism was linked with uniform anodic protection of zinc particles and excellent infiltration activity of graphene nanosheets. Moreover, a facile and accurate equivalent circuit model was presented to show the influence of graphene nanosheets in terms of galvanic reactions and seepage effects. Higher cathodic protection efficiency was proved by the lower percolation resistance of the coatings and reduced charge transfer resistance due to sacrificial zinc particles. The primary issue in graphene-based polymer coatings is the severe agglomeration of graphene nanosheets in polymer matrix due to their high aspect ratio, strong Vander Waals interactions and formation of vacuum during vacuum filtration process. Figure 5A and B represent field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showing debonding of graphene nanosheets and agglomeration, respectively, dispersed in polymer resin. Besides agglomeration, the presence of porosity formed during evaporation process, surface roughness and adhesion ability also strongly governs the protection efficiency of the coatings (Galpaya et al., 2012). Thus, to enhance the overall anticorrosion properties of the coating, it is necessary to prevent graphene segregation and generation of porosity to obtain a homogeneous distribution of graphene in polymer matrix.

(A) Typical FESEM image demonstrating incomplete bonding of graphene sheets with the polymer and (B) HRTEM image representing flocculation of graphene sheets in polymer matrix.

3.1 Strategies to enhance anticorrosion properties of GPMCCs

Several new approaches have been reported in the literature to increase dispersion stability, prevent agglomeration and promote compatibility of multilayered graphene nanosheets with the polymer matrix. These remedies include selection of appropriate synthesis method, usage of hybrid nanofillers, usage of suitable organic solvents and functionalization of graphene sheets (Atif & Inam, 2016). Some of the newly developed strategies to improve the barrier and corrosion performance of GPMCCs have been discussed in detail in the following sections.

3.1.1 Using conductive polymer matrix systems

CPs are widely used as anticorrosion materials because of their superior environmental stability and exceptional redox properties linked with the chain of nitrogen (Yao et al., 2008). CPs can be readily deposited in the form of an electroactive film directly on the metal surface by electropolymerization technique. These CP conductive films when formed along with suitable dopants/anions create exceptional redox reactions with the base metal. Electroactive polymers when reacted with graphene nanoplatelets form nanocomposite coating that provides double layer protection against metal corrosion. In the first stage of the protection mechanism, the conductive polymer forms a passive oxide layer on the metal surface through redox reactions. In the second stage, the freely dispersed graphene nanosheets in the polymer matrix decreases O2 and H2O molecules penetration by increasing the tortuosity of the diffusion pathways (Jafari et al., 2016). The commonly used conductive polymers for coating applications are polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (ppy), poly-3,4-ethylenedioxythiphene (PEDOT) and polyimide (PI).

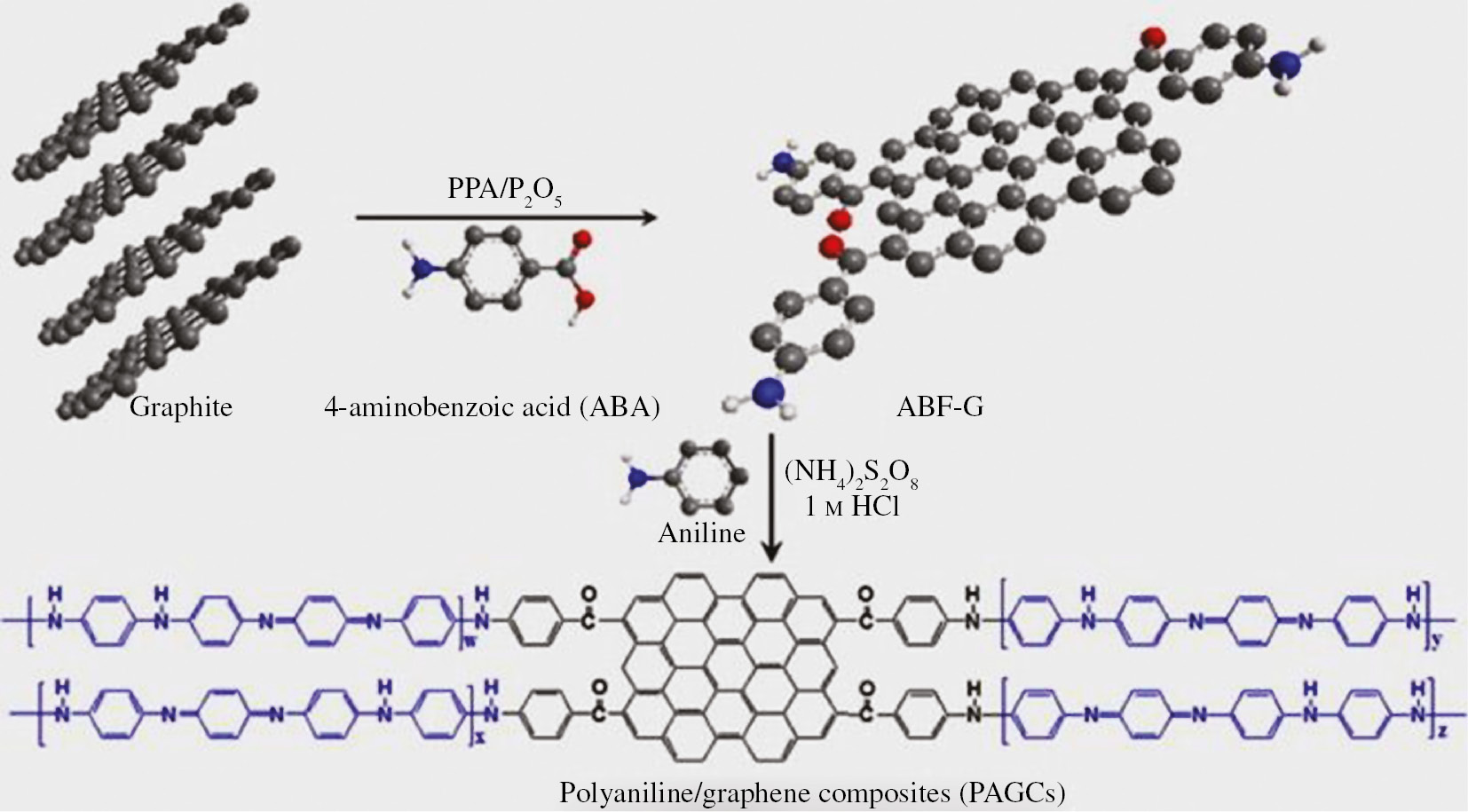

PANI composite coatings prevent gases/moisture particles from reaching the substrate surface and isolate it from the external environment by the following mechanisms (i) by controlling of the electrical conductivity of nanocomposite system (ii) by controlling redox activity of PANI (iii) by serving PANI as a sacrificial reservoir of inhibitor dopants/anions (Kraljić et al., 2003). Adherent graphene/PANI hybrid polymer coatings have been reported to be deposited on copper substrates by electropolymerization technique using cyclic voltammetry as shown in Figure 6. The resulted coatings showed outstanding barrier properties preventing water and oxygen molecules reaching coating-metal interface due to its high surface area and better dispersion of graphene in PANI matrix. Tafel curves indicated that in the presence of graphene nanosheets in PANI matrix causes corrosion potential shifting toward anodic regions with drastic improvement in the polarization resistance. The corrosion current density (Icorr) values derived from the Tafel curves were used to calculate protection efficiency with output of 98% (Jafari et al., 2016). Moreover, iterations of equivalent circuit model revealed that the coated samples possess high charge transfer resistance (Rct) and low double layer capacitance (Cdl) at coating-metal interface indicating superior corrosion performance.

Schematic diagram depicting the synthesis process of PANI/graphene composites coatings. Reproduced from Chang et al. (2012) with permission from Elsevier.

An identical synthesis technique was employed by Catt et al. (2017) to prepare a composite coating consisting of GO and an electroactive polymer (PEDOT) as matrix material and applied as a corrosion control layer on magnesium substrate. As-prepared coatings showed lower hydrogen evolution and corrosion rates of samples which were validated by hydrogen evolution test and Tafel extrapolation measurements. Moreover, the large radii of Nyquist curve obtained by impedance testing showed increased Rct value indicating higher corrosion resistance of sample coated with GO/PEDOT. After the analysis of various test results, the author concluded that the increased corrosion protection and low hydrogen generation of coated samples were attributed to the following three factors; accumulation of negative ions in the coating layer, formation of passive layer hindering ions diffusion and formation of Mg-phosphate film by redox reactions. Besides being corrosion resistant, the coated samples also exhibited reduced toxicity when exposed to cultured neurons indicating strong resistance to in vitro corrosion.

A recent study on electrodeposited polypyrrole films proved that dopant mobility in the films can be minimized significantly by employing organic anions leading to escalated properties (Raudsepp et al., 2008). Li et al. (2017) fabricated successfully a novel rGO/polypyrrole composite by voltammetry reduction method as an effective protective coating for corrosion prevention of mild steel substrates. Analysis of potentiodynamic polarization, open circuit potential and EIS measurements revealed that the rGO/ppy coated samples have large polarization resistance (54.1 kΩ cm2) and exhibited approximately 7 times higher corrosion protection ability compared to bare samples. Moreover, the coating protection efficiency of this nanocomposite was turn out to be 95.9% with good hydrophobic property. The corrosion protection mechanism in this type of coating was explained as the combination of formation of passive layer of rGO/ppy hybrid and formation of oxide film that retards the electron transportation through the coating. The author also explained corrosion and rust formation phenomenon on mild steel substrate which consisted of the following reactions

A novel three-fold protection mechanism was proposed by Chang et al. (2014a) in which PI formed two thin passive oxide layers i.e. Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 (due to the presence of active redox catalyst) while graphene nanosheets provided barrier effect. This graphene/PI composite coating was prepared by thermal imidization process on cold rolled steel samples. The coated samples were inspected for corrosion resistance by cyclic voltammetry studies and characterized by FTIR and TEM techniques. This drastic reduction in corrosion current densities and increase in polarization resistance (165.29 KΩ·cm2) with corresponding increment in Rct values derived from Nyquist plot proved that the as-prepared composite coatings have superior corrosion resistance. Furthermore, gas permeability test results disclosed that gas barrier properties were also increased due to uniform distribution of graphene in PI matrix obstructing penetration of oxygen and water molecules.

Although many conductive polymer matrix based graphene composite coatings have been developed with superior corrosion protection efficiency, most of them have not fully emerged in practical industrial applications. The pre-eminent reason for this issue is that the conductive polymer coatings do not adhere firmly to the metal surface, hence cannot provide protection against large defects for a long period of time specifically formed during localized corrosion (Deshpande et al., 2014). In addition, most of the conductive polymers are overpriced which makes it impractical to employ it as main matrix materials for the synthesis of large-scale graphene coatings.

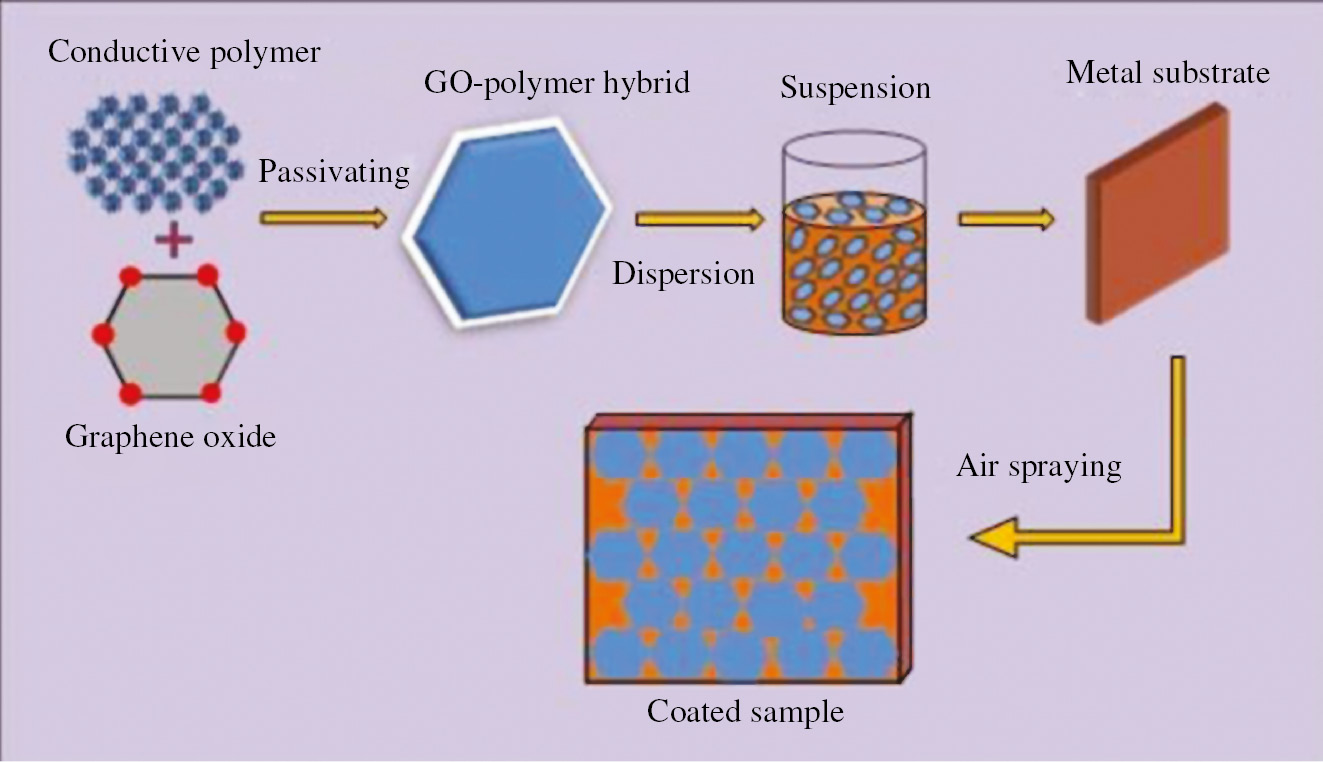

3.1.2 Passivating graphene sheets with polymeric resins

Graphene reinforced composite coatings (GRCCs) promotes galvanic corrosion similar to pristine graphene films when graphene particles are added above electrical percolation threshold in the composite due to abrupt increase in the magnitude of bulk conductivity (Potts et al., 2011). To phase out this corrosion furtherance effect in GRCCs, passivation is applied to graphene nanosheets. In graphene passivation process, each graphene nanosheet is enclosed by functionalizing with an insulated or conductive polymer to reduce graphene-graphene interactions in the matrix. Passivation by conductive polymer not only prevents restacking of graphene nanosheets but also their degradation by inhibiting corrosion by forming an oxide layer on the surface. Figure 7 shows the synthesis process of passivating polymer resin onto the surface of graphene nanosheets by using mechanical mixing method.

Schematic diagram illustrating passivation of graphene nanosheets by conductive polymer and subsequent coating process.

To reduce the effect of galvanic corrosion, Sun et al. (2014) synthesized low electrical conductive pernigraniline (PG) capped rGO composite and embedded it in polyvinyl-butyral (PVB) polymer matrix to modify the coating properties. Potentiodynamic polarization and EIS analysis indicated that the rGO/PG adapted PVB coating served as an excellent corrosion resistant barrier compared to pristine rGO or PG based PVB with reduced corrosion rate of 6.99×10−7 mm/year and enhanced protection efficiency of 97.3%. This amended corrosion property can be correlated to a high surface resistance of the coating due to less interaction between graphene-graphene/metal interface and by prolonging diffusion channels for corrosive species in the coating matrix. Several reports have been published that shows PANI as a promising conductive polymer to passivate GO and rGO nanosheets to avoid direct contact between them. Similarly, Cai et al. (2016) explicitly demonstrated the preparation of conductive rGO/PANI composite as anticorrosive filler in waterborne PU matrix forming a novel coating with superior anticorrosive performance. Tafel plots and EIS spectra obtained for coated samples immersed in 3.5% NaCl solution revealed improved corrosion resistance in terms of lower Icorr values and lower corrosion rates. Moreover, there was a drastic improvement polarization resistance (3057.52 Ω·cm2) and protection efficiency of the coatings. The coatings also exhibited good adhesion ability and high impact resistance. With an intention to attain uniform dispersion of graphene particles and escalate adhesion capability, Zhao et al. (2017) used waterborne epoxy resin as matrix material instead of PU polymer keeping the same rGO/PANI composite as an additive. Moreover, the author employed a novel one-pot emulsion polymerization technique resulting in escalation in electrochemical properties from 1 to 3 orders of magnitude.

In a separate investigation, Ramezanzadeh et al. (2017) reported the passivation strategy for the first time to improve the corrosion protection efficiency of ZREC. Covering GO nanosheets with PANI nanofibers not only prevented GO-GO contact but also resulted in the increase in electrical connections between zinc particles and base metal. Moreover, PANI nanofibers noticeably enhanced the sacrificial behaviour and barrier properties of zinc rich paint. Corrosion test results revealed improved corrosion performance with the addition of just 0.1 wt% GO/PANI composite to ZREC. In another report by the same author, Ramezanzadeh et al. (2015) successfully grafted polyisocyanate resin on graphene oxide nanosheets to enhance its compatibility in PU resin matrix. Polyisocyanate resin chains were adhered on GO surface because of the formation of amide and carbamate ester bonds. Salt spray tests results and EIS spectra analysis affirmed that the PU coatings with just 0.1 wt% GO/polyisocyanate hybrid nanosheets resulted in significant improvement in barrier and anticorrosion properties. Moreover, pull off adhesion test confirmed low adhesion loss in coatings even after a long period in corrosive conditions.

Deducing the advantage of a high rate of dispersibility and excellent compatibility of urea formaldehyde (UF) resin with epoxy polymer, Zheng et al. (2017) grafted UF resin on GO nanosheets via in-situ polycondensation process. These modified GO/UF hybrid nanosheets were dispersed into epoxy matrix and composed a novel GO/UF-epoxy composite coating. Sedimentation test confirmed the homogenous distribution of GO/UF nanosheets throughout the epoxy resin. Furthermore, EIS measurements revealed that corrosion protection efficiency and barrier performance of modified GO/UF-epoxy coatings were evidently distinctive compared with pristine epoxy coatings. The authors suggested that a plausible mechanism for enhanced corrosion performance is connected to freely dispersed GO hybrid nanosheets that blocked the penetration of electrolyte through diffusion pathways on the substrate, thus preventing the base metal from corrosion.

Several selective electroactive polymers have been exploited to refine anticorrosion properties of composite coatings. However, because of the intense intermolecular attraction between polymer chains, agglomeration problem persists, causing high porosity and weak solubility that cripple its anticorrosion performance (Mišković-Stanković et al., 2014). Nevertheless, this issue can be dealt with using conductive polymer pigments as fillers in neat organic resins such as acrylic resin or epoxy resin. Sheet templating method for conductive polymers is relatively a new technique in which conductive polymer pigments when mixed with graphene transforms into sheet-like structures because of the hybridization of graphene particles. To extend the free distribution of graphene nanosheets in polymer, Jiang et al. (2016) applied an innovative sheet templating approach to synthesize graphene/polypyrrole epoxy composite coatings. In this experiment, the author used inexpensive ppy pigments with graphene to form graphene/ppy hybrids. Composed hybrid graphene/ppy epoxy coatings revealed high electric conduction and improved corrosion protection efficiency by 50–100 order higher compared with neat epoxy coatings. Considerable enhancement of corrosion properties was ascribed to their hybridized graphene nanosheets, which causes sheet templating effect on ppy pigments. These hybrid sheets such as graphene/ppy pigments formed a large barrier in a parallel direction extending the pathways of corrosion agents to reach the coating/substrate interface. Moreover, the author pointed out that the mass percentage of graphene used in coatings was only about 0.05–0.15, which scales down the total cost of graphene/ppy epoxy coatings.

From the above literature reports, it can be concluded that passivation of graphene sheets by polymer resins can protect the metal against corrosion attack for a longer period as compared to pristine graphene films. However, the structural strength of these coatings is not sufficient to withstand external damage and becomes susceptible to the corrosion effect. Besides strength, another factor that limits the use of the conductive polymer to passivate graphene nanosheets is its high cost. Certain conductive polymers such as PANI, ppy and PEDOT are very expensive, eventually increasing the final price of the coatings when prepared in large scale for industrial applications.

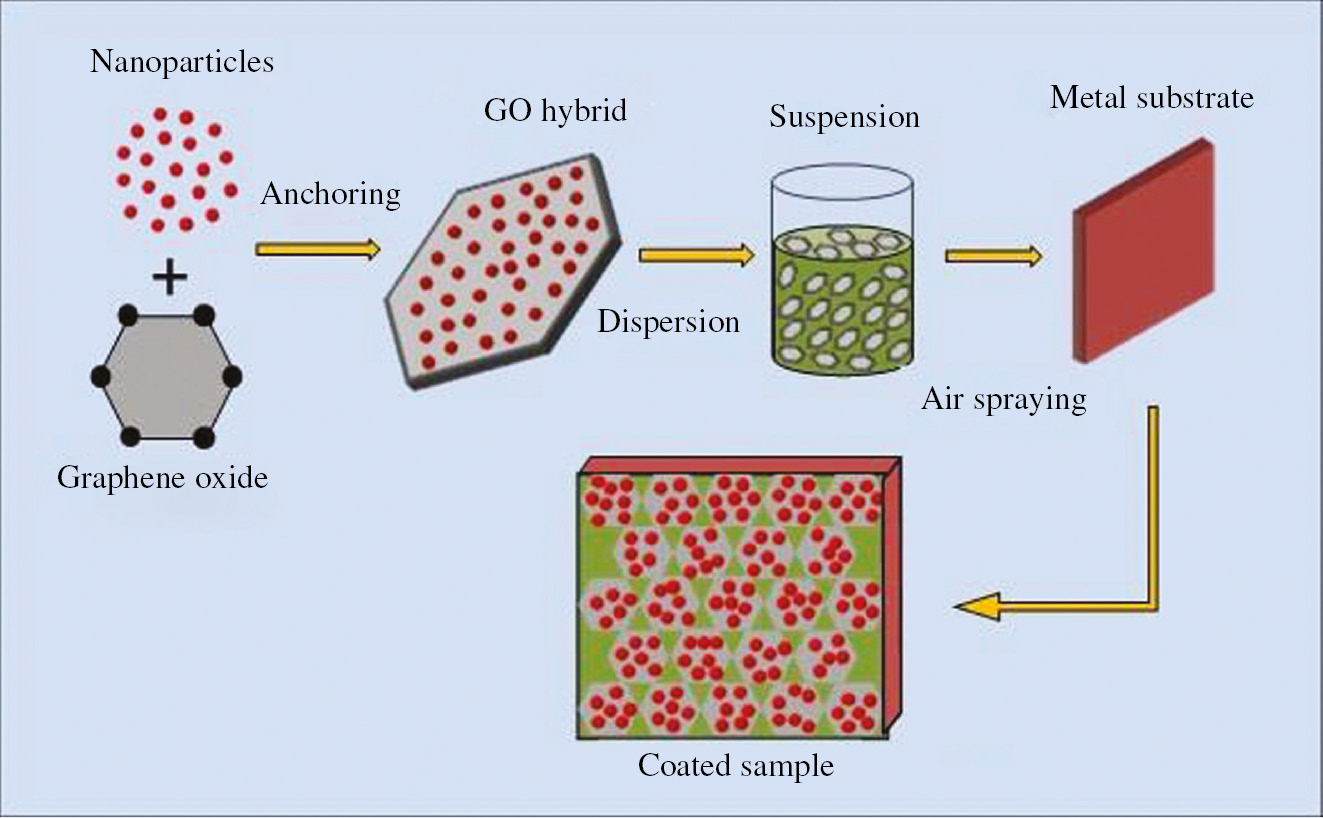

3.1.3 Anchoring nanoparticles on graphene nanosheets

Numerous research articles have been reported on problems concerning to compatibility and dispersion of graphene sheets in the polymer matrix. As discussed in the earlier section, graphene nanosheets have a tendency to agglomerate when mixed with the polymer matrix, and to avert this difficulty, a new strategy of tethering graphene nanosheets with metal oxide nanoparticles is adopted by several researchers (Zhang et al., 2014; Archana et al., 2018). Recently, some investigators reported that the introduction of inorganic nanoparticles between graphene layers also prevents re-agglomeration. These anchored nanoparticles increase the surface area and interplanar spacing of graphene sheets and promote bonding with the polymer matrix on both sides (Wang et al., 2010). Apart from increasing the dispersibility of graphene sheets, in some cases, metallic nanoparticles also behave like corrosion inhibitors forming an oxide layer and provide extra protection against corrosion. Figure 8 represents the synthesis process of attaching nanoparticles onto the surface of graphene nanosheets by using simple mechanical mixing method. Furthermore, when these spherical shaped nanoparticles are grafted on the surface of graphene oxide, micropores generated in hybrid polymer coatings during the solvent evaporation process are covered inherently preventing electrolyte permeation (Ma et al., 2016). Among various available metal oxide nanoparticles, magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles are considered as ecofriendly materials with remarkable corrosion protection and adhesion properties when doped in a composite matrix (El-Mahdy et al., 2014).

Schematic diagram illustrating anchoring of nanoparticles on graphene sheets and subsequent coating process.

Di et al. (2016a,b,c) synthesized a novel hybrid GO/Fe3O4 epoxy coatings by a hydrolytic polycondensation process in which Fe3O4 nanoparticles were decorated on GO nanosheets. Fe3O4 nanoparticles were prepared by coprecipitation approach and tethered onto the GO nanosheets with the assistance of silane coupling additives. EIS spectra indicated an enhancement in anticorrosion efficacy with large impedance modulus due to excellent dispersion of GO/Fe3O4 hybrid sheets blocking the micropores to prevent the electrolytic diffusion into the epoxy matrix. Also, the long-term protection efficiency of the coatings was not up to the mark because of the generation of surface defects upon exposure to electrolyte for 20 days. This hybrid coating developed was compact in nature and cannot be deposited on elastic substrate surfaces such as flexible metal pipes and plates. For stretchable surfaces, Wang et al. (2017) pioneered a soft flexible GO/Fe3O4-natural rubber composite coatings using latex compounding technique. Interestingly, the composite coatings showed up exceptional corrosion resistance in terms of reduced corrosion current densities and reduced corrosion rate (5.2×10−4 mm/year). The proposed mechanism for improved anticorrosion performance was due to the aligned structure of Fe3O4-modified GO nanosheets that assisted to deter the diffusion pathways for corrosion agents. Furthermore, Fe3O4 nanoparticles attached on GO nanosheets also avoided the GO-metal interaction, therefore raising the polarization resistance of the coatings, which was validated by EIS calculations.

Similarly, silica nanoparticles can also be employed as GO modifier because of its good corrosion resistance, excellent chemical stability and high dispersion rate (Chen et al., 2012). Ramezanzadeh et al. (2016a,b) developed a novel two-step sol-gel method of preparing silica nanoparticles decorated GO nanohybrid and employed it in epoxy resin to make a hybrid coating with excellent corrosion resistance. On the contrary, Pourhashem et al. (2017a,b) used tetraethyl orthosilicate as organosilane to diffuse SiO2 nanoparticles on the surface of GO nanosheets. Introduction of SiO2 nanoparticles considerably improved dispersion and corrosion inhibition efficiency. Also, the cathodic delamination of coating notably decreased because of the existence of GO/SiO2 hybrid nanosheets in the coatings. SiO2 nanoparticles functioned as a barrier between the GO nanosheets and improved its degree of exfoliation and dispersion in the epoxy matrix, causing a decrease in moisture adsorption and penetration of corrosive media through the nanocomposite coatings.

Recently, lanthanide nanoparticles were used as a suitable substitute for SiO2 and Fe3O4 nanoparticles because of their low toxicity and good corrosion inhibition effect. Lanthanide-based compounds can restrain corrosion reaction and preserve the metal surface against degradation even under strident circumstances. Lanthanide-based coatings have been proven as excellent corrosion inhibitors and protector against high-temperature oxidation (Bethencourt et al., 1998). Rahman et al. (2017) attempted to synthesize hybrid nanocomposite coating by incorporating graphene and ceria nanoparticles composite in water-borne PU matrix for corrosion protection. Polarization curves of coated mild steel samples after 15 day exposure to 3.5% NaCl showed higher corrosion potentials for G/CeO2-PU coatings, indicating better corrosion performance compared with pristine PU coatings. The synthesized coatings exhibited remarkable anticorrosion properties by barrier and passivation effects, resisting cracks formation and maintained their integrity when exposed to extreme environment.

Titanium oxide (TiO2) nanopowder has been reported to be successfully integrated into the neat epoxy coating to improve its barrier and corrosion performance (Radoman et al., 2014). Similar to graphene nanosheets, TiO2 nanopowder also tends to segregate when mixed with other materials because of its high polarity and large specific surface area. To remove this limitation and enhance the anticorrosion performance of neat epoxy coatings, Yu et al. (2015a,b) anchored TiO2 nanoparticles on GO nanosheets, and this hybrid was reinforced in epoxy coatings via solvent evaporation method. As prepared GO/TiO2-epoxy coatings exhibited remarkable corrosion protection behavior with maximum corrosion protection efficiency surging up to 99.96%. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs revealed that GO/TiO2 hybrid sheets distributed homogenously in the epoxy matrix and formed sheet-like structures blocking the micropores in coatings to limit the penetration of electrolytic molecules. Experimental results also demonstrated that the anticorrosion performance of GO/TiO2-epoxy nanocomposite coatings largely depends on the extent of dispersion and exfoliation of graphene particles.

Similar to titania nanoparticles, aluminum oxide (Al2O3) and zirconium oxide (ZrO2) nanoparticles were also anchored on GO nanosheets by Yu et al. (2015a,b) and Di et al. (2016a,b,c) and dispersed in epoxy resin matrix via solvent evaporation and ultrasonic mixing process using silane coupling agents to form highly corrosion resistant GO/Al2O3-epoxy and GO/ZrO2-epoxy coatings, respectively. Introduction of GO/Al2O3 and GO/ZrO2 nanohybrids in epoxy resin exhibited excellent dispersion and exfoliation property, thereby enhancing the corrosion performance of the coatings. However, the low weight percentage of nanoparticles in epoxy was not able to enhance notably the anticorrosion properties to a higher extent. Moreover, both the composite coatings showed similar corrosion protection mechanism. Exceptional anticorrosion behavior of both the hybrid nanocoatings was associated to its active double barrier property and free dispersion of GO hybrid sheets in epoxy coatings.

Considering the above literature reports, it can be noticed that the nanoparticles selected for anchoring on GO nanosheets are metal oxide-based nanoparticles that are expensive to synthesize. Hence, to reduce the overall cost of graphene-epoxy coatings, low-cost calcium carbonate (CaCO3) nanoparticles were exploited for the first time to modify the surface of graphene nanosheets. Di et al. (2016a,b,c) fabricated GO nanosheets anchored with CaCO3 nanoparticles by means of 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTES) additive. These modified GO/CaCO3 hybrid nanosheets were diffused in the epoxy matrix and cured to form highly anticorrosive composite coatings. SEM and TEM micrographs revealed homogeneous dispersion of CaCO3-anchored GO nanosheets in the epoxy matrix, which in turn enhanced the anticorrosion performance of the coatings by providing tortuous passage to the electrolyte.

The foremost limitation of using inorganic nanoparticles in polymer hybrid coatings is its compatibility with graphene nanosheets and the polymer matrix (Kim et al., 2010). Moreover, expensive coupling agents such as APTES are needed to covalently attach nanoparticles onto the surface of graphene sheets. Also, the thickness of the final coated layer on the metal surface increases with the type of polymer matrix used ranging from 40 nm to 100 μm, which can strongly influence the structural properties of the metal (Watcharotone et al., 2007). Thus, the implementation of this strategy of anchoring expensive inorganic nanoparticles on graphene oxide nanosheets makes GPMCCs inappropriate for large surface area substrates.

3.1.4 Chemical functionalization of graphene nanosheets

Functionalization of graphene sheets by chemical modification is one of the convenient approaches to counter flocculation and stabilize graphene suspension within the polymer matrix. Chemical functionalization is an effective way to amend the defects in graphene by altering the electronic and crystal structure to induce specific electronic and magnetic properties (Boukhvalov & Katsnelson, 2008). The promising chemical methods to modify a graphene surface are covalent functionalization and noncovalent functionalization, which increase the interlayer distance between graphene layers and promote steady interfacial interactions between graphene nanosheets and the polymer matrix (Boukhvalov & Katsnelson, 2009). In covalent functionalization, covalent bonds are formed between the epoxide groups and carboxylic groups of GO and the chemical coupling agent. However, covalent grafting of GO sheets involves lengthy chemical processes that can induce irregularities changing the inherent corrosion properties, whereas in noncovalent functionalization, strong π-π bonds are established between GO nanosheets and stabilizer conserving its properties (Kuila et al., 2012).

One of the most widely used chemicals for functionalization of graphene is APTES, which is a type of silane coupling agent and promotes strong interfacial bonding between graphene sheets and the polymer matrix. Pourhashem et al. (2017a,b) evaluated the influence of amino silane on GO nanosheets as nanofillers in epoxy matrix coatings to increase dispersion quality. Functionalization of GO nanosheets with APTES showed a good interfacial interaction of GO with polymer and superior anticorrosion performance as confirmed by FESEM and EIS analysis. However, the addition of modified GO of more than 0.1 wt% resulted in the agglomeration of nanosheets in the matrix reducing the barrier properties. Another study (Mo et al., 2015) was carried out to investigate the impact of modified graphene oxide by APTES in PU composite coatings. The team fabricated PU composite coatings by reinforcing functionalized graphene oxide (FGO) and functionalized graphene with exceptional corrosion and tribological properties. The graphene nanosheets were chemically treated with APTES to enhance the dispersion and compatibility with PU matrix. However, corrosion testing results of FGO/PU coatings exhibited lower corrosion protection when compared with functionalized graphene/PU coatings vowing to the presence of plentiful oxygenated groups. These oxygenated groups of FGO promoted stronger interfacial interaction but induce imperfections in graphene lattice structure. Although salinization is a popular method to functionalize graphene, it suffers from the limitation of hydrolytic degradation. When a salinized composite is subjected to the aqueous atmosphere, the salinized interfaces absorbs moisture and gets hydrolyzed, thereby opening additional passages for water molecules to diffuse (Matinlinna et al., 2004).

Apart from silane, there are other types of coupling agents that can be employed to functionalize graphene such as titanate and zirconate coupling agents. Table 1 shows various chemicals used to modify graphene nanosheets to increase dispersion and bonding with the polymer matrix. Li et al. (2014) employed titanate coupling agent for the first time in rGO/PU composite coatings and found that the titanate not only improves the homogeneous distribution of rGO nanosheets in PU matrix but also aligns itself parallel to the substrate surface. This auto-alignment property of graphene nanosheets was directed by the decrease in total excluded volume. Nevertheless, this unique in-plane alignment property guides in utilizing the full surface area of rGO layers to confront the electrolyte and provide tortuous path to limit its permeation through the coatings. High anticorrosion performance of the composite coatings was confirmed by Nyquist plots even after 96 h of exposure to electrolyte. However, the titanate-treated graphene did not display a self-alignment behavior when added up to 0.2 wt% in the matrix and was scattered in random three-dimensional directions. In another research, Diouf and Asmatulu (2014) carried out a study to determine the effect of organofunctional alkoxysilane modified graphene on corrosion and weathering resistance of fiber-reinforced composite substrates. The graphene nanoplatelets were salinized and mixed in different proportions in PU primer matrix via mechanical mixing sonication process. Experimental results indicated that with the addition of 2 wt% salinized graphene sheets produced drastic improvement against corrosion and UV degradation.

Functions and synergistic effects of functionalizing agents on graphene nanosheets.

| Filler+matrix | Functionalizing agent | Substrates | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene+epoxy | Poly-2-butylaniline (P2BA) | Mild steel | Works as dispersing agent and helps in stabilizing the dispersion of graphene nanosheets in organic solvents; imparts synergistic redox catalytic effect in epoxy coatings | Chen et al. (2017) |

| GO+epoxy | 3-Aminopropyl triethoxysilane (APTES) | Mild steel | Promotes the bonding between graphene oxide layers and epoxy matrix | Pourhashem et al. (2017a,b) |

| GO+polystyrene | p-Phenylenediamine+4-vinylbenzoic acid | Mild steel | Augments the GO particles dispersion and improves the interaction of modified GO flakes with polystyrene matrix; improves storage modulus and mechanical strength of the coated sample | Yu et al. (2014) |

| GO+epoxy | p-Phenylenediamine (PPD) | Mild steel | Enhances interfacial interactions enhancement between polymer and GO sheets; increases tensile strength and fracture toughness of the coated sample | Ramezanzadeh et al. (2016a,b, 2018) |

| rGO+polyurethane | Titanate coupling agent (TCA) | Galvanized steel | Functions as adhesion promoter and prevents agglomeration of rGO sheets; causes self-alignment of graphene layers parallel to the substrates surface | Li et al. (2014) |

Ramezanzadeh et al. (2016a,b, 2018) and his team conducted two separate experiments with p-phenylenediamine (PPDA) as a functionalizing agent. In the first experiment, they covalently grafted PPDA aromatic diamine on GO nanosheets to enhance dispersion and interfacial bonding of GO nanosheets with epoxy matrix. In the second experiment, they synthesized PPDA functionalized GO nanosheets with three different lateral sizes, i.e. small area GO nanosheets with 0.85 μm size, medium area GO nanosheets with 8.2 μm size and large area GO nanosheets with 38 μm size. The covalent functionalization of GO surface was achieved through wet transfer method and resulted in successful intercalation leading to increased corrosion inhibition efficiency. Addition of FGO into the epoxy enhanced ionic resistance and hydrophobicity of the coating while hindered the penetration of Cl− ions due to creation of covalent bonds between amine groups of PPDA and epoxide groups of GO. Furthermore, the GO nanosheets with medium lateral size delivered highest barrier performance and anticorrosion properties. A similar investigation was reported by Gu et al. (2015) in which carboxylated aniline trimer stabilizer was used as dispersing agent with graphene nanosheets and synthesized water-soluble graphene/epoxy hybrid coatings. After functionalization, stable high concentration of graphene nanosheets (>1 mg/mL) was able to disperse in epoxy system by forming strong π-π bonds between graphene and carboxylated aniline trimer stabilizer. A series of electrochemical measurements revealed that the increased dispersion of graphene nanosheets into waterborne epoxy drastically enhanced corrosion resistance properties and minimized the coating delamination.

Zhu et al. (2017) very recently developed a novel 3-(1-(2-aminopropoxy)propan-2-ylamino)propane-1-sulfonate sodium functionalized water-dispersible graphene via nucleophilic ring opening reaction. These chemically modified graphene nanosheets were dispersed in acrylic modified alkyd resin matrix to enhance the corrosion protection performance. SEM images showed the homogeneous distribution of graphene sheets in alkyd resin nano-emulsion forming compact and uniform coatings that can improve barrier properties against moisture and oxygen. Corrosion tests indicated that 3-(1-(2-aminopropoxy)propan-2-ylamino)propane-1-sulfonate sodium functionalized coatings has superior corrosion-resistant properties compared with pristine alkyd resin coatings. EIS measurements further revealed that the formed coatings exhibit dual corrosion protection mechanisms, i.e. barrier effect and anodic protection mechanism. Yu et al. (2014) demonstrated successfully for the first time the application of vinyl-polystyrene/GO (V-PS/GO) hybrid coatings in anticorrosion system. The nanocomposite composite coating was prepared by in situ miniemulsion polymerization process and tested for anticorrosion properties. The as-prepared hybrid coatings exhibited high corrosion resistance properties with inhibition efficiency of 99.53% by introduction of 2 wt% of functionalized GO in the polystyrene matrix. Apart from corrosion properties, the GO-modified coatings showed an improvement in mechanical properties, thermal stability, storage modulus and thermal decomposition temperature. The author explained the reason for this enhanced performance by V-PS/GO nanocomposite coatings as the increased dispersion of GO nanosheets in nonconjugated polystyrene matrix due to strong π-π interactions between polystyrene and modified GO.

Undoubtedly, chemical modification of graphene sheets is a beneficial approach to counter the agglomeration, but there are certain demerits associated with it. First, the use of chemicals could alter graphene properties that can subsequently affect the corrosion properties of the coatings. Second, chemical functionalization of graphene is a time-consuming and tedious process. Third, most of the chemicals used for functionalization are expensive and toxic in nature (Hirsch et al., 2012).

Graphene-embedded composite coatings containing well-dispersed graphene sheets in the matrix material not only improves barrier properties but also improves structural durability and thermal and electrical properties (Hu et al., 2014). However, the graphene sheets used in these coatings are synthesized employing presently available methods generating various types of structural defects that can affect the protection efficiency. The direct impact of these local defects in graphene can cause accumulation of oxygen molecules that can degrade its performance (Rohini et al., 2015). All the demerits described above restrict the free usage of graphene-based coatings for anticorrosion application in a large scale. More advanced processes and methods with regard to the enhancements in exfoliation, dispersion and adhesion property of graphene sheets are needed so that it can be utilized effectively in the preparation of anticorrosion coatings. Apart from requiring costly equipment and tedious preparation methods, most of the strategies described in the above section to improve corrosion performance of GPMCCs need expensive chemicals and materials that can harm the surrounding environment.

Recent research reports on corrosion performance of graphene-based composite coatings and related electrochemical parameters are summarized in Table 2. From the table, it can be observed that the corrosion inhibition efficiency of prepared coatings depends upon several factors such as synthesis method, type of deposition method and substrate material. Furthermore, the corrosive environment to which the coatings are subjected and the adhesion ability between the polymer and the substrate surface could also affect the performance of the coatings. Over the past 5 years, there is a drastic increase in research conducted on graphene coatings with polymer as matrix material compared with pristine graphene coatings (Bonavolontà et al., 2017). Future research could be focused on experimenting with coatings containing low-cost inorganic fillers combined with graphene with superior properties. Only a few innovative synthesis techniques are reported in the recent years to improve the performance of the coatings. Even though magnesium and titanium are being used widely nowadays for a variety of applications, most of the research is directed toward the deposition of coatings on mild steel and copper substrates only.

Summary and comparison of the electrochemical parameters of graphene-reinforced polymer composite coatings deposited on different substrate materials.

| Composite coating | Coating method | Substrate material | Coating with graphene |

Coating without graphene |

References | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E corr (mV) | I corr (μA/cm2) | R corr (mm/year) | R p (KΩ cm2) | E corr (mV) | I corr (μA/cm2) | R corr (mm/year) | R p (KΩ cm2) | ||||

| rGO/ppy | Electrodeposition | Mild steel | −544 | 0.85 | 0.0099 | 66.9 | −691 | 9.34 | 10.85×10−2 | 6.33 | Li et al. (2017) |

| rGO+Fe3O4/natural rubber | Cold spraying | Mild steel | −274 | 1.40 | 0.016 | 0.0252 | −862 | 110.6 | 1.28 | 271×10−3 | Wang et al. (2017) |

| GO+SiO2/epoxy | Cold spraying | Mild steel | −439 | 0.09 | 0.0012 | 0.0417 | −543 | 14.6 | 0.1705 | 0.00186 | Pourhashem et al. (2017a,b) |

| rGO/ZnAl+LDH+epoxy | Cold spraying | Mild steel | −0.635 | 0.0733 | 0.0007 | 3.49 | −629 | 0.49 | 0.00576 | 3.49 | Yu et al. (2017) |

| rGO+lanthanide ions+DBSA/ppy | Solvent evaporation method | Mild steel | −0.162 | 0.013 | 0.006 | 4.77×103 | −442 | 3.26 | 1.45 | 2.19×104 | Alam et al. (2016) |

| GO/chitosan | Dip coating | Mild steel | −374 | 3.9 | 0.0017 | 1.44 | −457 | 7.7 | 0.00256 | 0.00387 | Fayyad et al. (2016) |

| GO/epoxy | Film applicator | Mild steel | −250 | 0.2015 | 0.0031 | 1.669 | −0.85 | 0.501 | 5.884×10−3 | 0.756 | Rajabi et al. (2015) |

| G/polyurethane | Film applicator | Mild steel | −27.2 | 2.45×10−5 | 2.88×10−7 | – | −125 | 0.178×10−6 | 2.09×10−9 | – | Huang et al. (2016) |

| G/epoxy | Film applicator | Q235 steel | −566 | 0.0551 | 0.0007 | 369.4 | −637 | 0.121 | 0.00142 | 169.2 | Liu et al. (2016) |

| G/polyimide | Spin coating | Cold rolled steel | −432 | 0.15 | 0.00176 | 165.29 | −573 | 2.75 | 0.256 | 11.1 | Chang et al. (2014a) |

| G/epoxy | Nano-casting | Cold rolled steel | −411 | 0.10 | 0.00009 | 442 | −633 | 0.35 | 0.00033 | 37.87 | Chang et al. (2014b) |

| G/PANI | Electropolymerization | Copper | −234 | 0.1 | 0.00005 | 1.5×102 | −0.3 | 1.8 | 4×10−3 | 1×104 | Jafari et al. (2016) |

| GO/PMMA | Drop casting | Copper | −108 | 0.83×10−3 | 9.35×10−6 | – | −237 | 0.157 | 0.001822 | – | Qi et al. (2015) |

| rGO+DE+PDMS | Cold spray | Copper | −0.112 | 0.159 | 0.00158 | – | −108.7 | 0.95 | 0.011 | – | Nine et al. (2015a,b) |

| GO/pernigraniline | Dip coating | Copper | −23 | 5.98×10−5 | 6.99×10−7 | 9.86×105 | −61 | 4.11×10−4 | 4.8×10−6 | 1.9×108 | Sun et al. (2014) |

| rGO/isocyanate | Electrodeposition | Copper | −211 | 4 | 0.04663 | – | −164 | 38.25 | 0.55 | – | Singh et al. (2013a,b) |

| GO/isocyanate | Electrodeposition | Copper | −211 | 3.49 | 0.04068 | 0.025 | −164 | 38.28 | 0.58 | 0.008 | Singh et al. (2013a,b) |

| rGO/epoxy | Spin coating | Zinc | −957 | 0.18 | 0.00272 | – | −900 | 0.75 | 1.3 | – | Zhang et al. (2015) |

| rGO/silicon-acrylate resin | Spin coating | Zinc | −585 | 0.45 | 0.00682 | – | −327 | 13.8 | 28.7 | – | Cao et al. (2015) |

| GO/PEDOT | Electropolymerization | Magnesium | −155 | 12.3 | 0.28233 | – | −1705 | 49.6 | 1.1385 | – | Catt et al. (2017) |

| rGO/PANI | Brush painting | Glass | −112 | 0.74 | 0.0081 | – | −0.153 | 12.5 | 0.078 | – | Zhao et al. (2017) |

| G/PANI | Nano-casting | Glass | −537 | 0.38 | 0.00044 | 135.22 | −647 | 3.7 | 0.0043 | 14.43 | Chang et al. (2012) |

4 Summary and future trends

In this review article, a comprehensive survey of various synthesis techniques and strategic approaches to prevent flocculation of graphene sheets in the different polymer matrix has been presented. Despite impressive results, most of the coatings described in the above sections are not fabricated in mass quantity for large surface area application due to cost limitations. Moreover, there are still many obscure factors influencing the corrosion properties that are needed to be investigated in graphene-embedded composite coatings. The primary challenge in fabricating effective coatings to protect the metal surface from corrosion is to utilize economical filler materials and develop more facile and viable ecofriendly synthesis techniques. Prospective future studies will be directed on reducing the overall cost of coatings and enhancing the dispersibility and compatibility of graphene sheets in various polymer matrix materials by developing innovative strategies. Further advancement in this specific area could lead to the fabrication of ultramodern nanostructure-tailored coatings with exceptional corrosion inhibition capabilities. While this review paper has been written with definite corrosion application in mind, the original significance of comprehending graphene-based coating systems will give far-reaching impact on a wide range of advanced emerging applications.

References

Abdullayev E, Abbasov V, Tursunbayeva A, Portnov V, Ibrahimov H, Mukhtarova G, Lvov Y. Self-healing coatings based on halloysite clay polymer composites for protection of copper alloys. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2013; 5: 4464–4471.10.1021/am400936mSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

Advincula RC. Conducting polymers with superhydrophobic effects as anticorrosion coating. In Intelligent coatings for corrosion control, Elsevier 2015: 409–430.10.1016/B978-0-12-411467-8.00011-8Suche in Google Scholar

Alam R, Mobin M, Aslam J. Polypyrrole/graphene nanosheets/rare earth ions/dodecyl benzene sulfonic acid nanocomposite as a highly effective anticorrosive coating. Surf Coat Tech 2016; 307: 382–391.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2016.09.010Suche in Google Scholar

Alfred CF. Metal-clad aluminum alloys. US Patent no.: 2726436. In: Google patents 1995. Available at: https://patents.google.com/patent/US2726436A/en.Suche in Google Scholar

Alhumade H, Yu A, Elkamel A, Simon L. Optimizing corrosion protection of Stainless Steel 304 by epoxy-graphene composite using factorial experimental design. In: Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Detroit, Michigan, USA, September 23–25, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

Ambrosi A, Pumera M. The structural stability of graphene anticorrosion coating materials is compromised at low potentials. Chem: Eur J 2015; 21: 7896–7901.10.1002/chem.201406238Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Amini R, Vakili H, Ramezanzadeh B. Studying the effects of poly(vinyl) alcohol on the morphology and anti-corrosion performance of phosphate coating applied on steel surface. J Taiwan Inst Chem E 2016; 58: 542–551.10.1016/j.jtice.2015.06.024Suche in Google Scholar

Archana S, Kumar KY, Jayanna B, Olivera S, Anand A, Prashanth M, Muralidhara H. Versatile Graphene oxide decorated by star shaped Zinc oxide nanocomposites with superior adsorption capacity and antimicrobial activity. J Sci: Adv Mater Dev 2018; 3: 167–174.10.1016/j.jsamd.2018.02.002Suche in Google Scholar

Ates M. A review on conducting polymer coatings for corrosion protection. J Adhes Sci Technol 2016; 30: 1510–1536.10.1080/01694243.2016.1150662Suche in Google Scholar

Atif R, Inam F. Reasons and remedies for the agglomeration of multilayered graphene and carbon nanotubes in polymers. Beilstein J Nanotech 2016; 7: 1174.10.3762/bjnano.7.109Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Balandin AA, Ghosh S, Bao W, Calizo I, Teweldebrhan D, Miao F, Lau CN. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett 2008; 8: 902–907.10.1021/nl0731872Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Berry V. Impermeability of graphene and its applications. Carbon 2013; 62: 1–10.10.1016/j.carbon.2013.05.052Suche in Google Scholar

Bethencourt M, Botana F, Calvino J, Marcos M, Rodriguez-Chacon M. Lanthanide compounds as environmentally-friendly corrosion inhibitors of aluminium alloys: a review. Corros Sci 1998; 40: 1803–1819.10.1016/S0010-938X(98)00077-8Suche in Google Scholar

Bitounis D, Ali-Boucetta H, Hong BH, Min DH, Kostarelos K. Prospects and challenges of graphene in biomedical applications. Adv Mater 2013; 25: 2258–2268.10.1002/adma.201203700Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Böhm S. Graphene against corrosion. Nat Nanotechnol 2014; 9: 741–742.10.1038/nnano.2014.220Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Bonaccorso F, Sun Z, Hasan T, Ferrari A. Graphene photonics and optoelectronics. Nat Photonics 2010; 4: 611–622.10.1038/nphoton.2010.186Suche in Google Scholar

Bonavolontà C, Aramo C, Valentino M, Pepe G, De Nicola S, Carotenuto G, Longo A, Palomba M, Boccardi M, Meola C. Graphene-polymer coating for the realization of strain sensors. Beilstein J Nanotechnol 2017; 8: 21–27.10.3762/bjnano.8.3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Boukhvalov D, Katsnelson M. Chemical functionalization of graphene with defects. Nano Lett 2008; 8: 4373–4379.10.1021/nl802234nSuche in Google Scholar

Boukhvalov D, Katsnelson M. Chemical functionalization of graphene. J Phys Condens Matter 2009; 21: 344205.10.1088/0953-8984/21/34/344205Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Bunch JS, Verbridge SS, Alden JS, Van Der Zande AM, Parpia JM, Craighead HG, McEuen PL. Impermeable atomic membranes from graphene sheets. Nano Lett 2008; 8: 2458–2462.10.1021/nl801457bSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

Cai K, Zuo S, Luo S, Yao C, Liu W, Ma J, Mao H, Li Z. Preparation of polyaniline/graphene composites with excellent anti-corrosion properties and their application in waterborne polyurethane anticorrosive coatings. RSC Adv 2016; 6: 95965–95972.10.1039/C6RA19618GSuche in Google Scholar

Cao Y, Tian X, Wang Y, Sun Y, Yu H, Li D-S, Liu Y. In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide-reinforced silicone-acrylate resin composite films applied in erosion resistance. J Nanomater 2015; 2015: 2.10.1155/2015/405087Suche in Google Scholar

Catt K, Li H, Cui XT. Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) graphene oxide composite coatings for controlling magnesium implant corrosion. Acta Biomater 2017; 48: 530–540.10.1016/j.actbio.2016.11.039Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Chang C-H, Huang T-C, Peng C-W, Yeh T-C, Lu H-I, Hung W-I, Weng C-J, Yang T-I, Yeh J-M. Novel anticorrosion coatings prepared from polyaniline/graphene composites. Carbon 2012; 50: 5044–5051.10.1016/j.carbon.2012.06.043Suche in Google Scholar

Chang K, Hsu C, Lu H, Ji W, Chang C, Li W, Chuang TL, Yeh JM, Liu WR, Tsai M. Advanced anticorrosive coatings prepared from electroactive polyimide/graphene nanocomposites with synergistic effects of redox catalytic capability and gas barrier properties. Express Polym Lett 2014a; 8: 2075–2083.10.3144/expresspolymlett.2014.28Suche in Google Scholar

Chang K-C, Hsu M-H, Lu H-I, Lai M-C, Liu P-J, Hsu C-H, Ji W-F, Chuang T-L, Wei Y, Yeh J-M, Liu W-R. Room-temperature cured hydrophobic epoxy/graphene composites as corrosion inhibitor for cold-rolled steel. Carbon 2014b; 66: 144–153.10.1016/j.carbon.2013.08.052Suche in Google Scholar

Chen L, Chai S, Liu K, Ning N, Gao J, Liu Q, Chen F, Fu Q. Enhanced epoxy/silica composites mechanical properties by introducing graphene oxide to the interface. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2012; 4: 4398–4404.10.1021/am3010576Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Chen C, Qiu S, Cui M, Qin S, Yan G, Zhao H, Wang L, Xue Q. Achieving high performance corrosion and wear resistant epoxy coatings via incorporation of noncovalent functionalized graphene. Carbon 2017; 114: 356–366.10.1016/j.carbon.2016.12.044Suche in Google Scholar

Cui Y, Kundalwal S, Kumar S. Gas barrier performance of graphene/polymer nanocomposites. Carbon 2016; 98: 313–333.10.1016/j.carbon.2015.11.018Suche in Google Scholar

Daneshvar-Fatah F, Nasirpouri F. A study on electrodeposition of Ni-noncovalnetly treated carbon nanotubes nanocomposite coatings with desirable mechanical and anti-corrosion properties. Surf Coat Technol 2014; 248: 63–73.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2014.03.023Suche in Google Scholar

Deshpande PP, Jadhav NG, Gelling VJ, Sazou D. Conducting polymers for corrosion protection: a review. J Coat Technol Res 2014; 11: 473–494.10.1007/s11998-014-9586-7Suche in Google Scholar

Di H, Yu Z, Ma Y, Li F, Lv L, Pan Y, Lin Y, Liu Y, He Y. Graphene oxide decorated with Fe3O4 nanoparticles with advanced anticorrosive properties of epoxy coatings. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2016a; 64: 244–251.10.1016/j.jtice.2016.04.002Suche in Google Scholar

Di H, Yu Z, Ma Y, Pan Y, Shi H, Lv L, Li F, Wang C, Lont T, He Y. Anchoring calcium carbonate on graphene oxide reinforced with anticorrosive properties of composite epoxy coatings. Polym Adv Technol 2016b; 27: 915–921.10.1002/pat.3748Suche in Google Scholar

Di H, Yu Z, Ma Y, Zhang C, Li F, Lv L, Pan Y, Shi H, He Y. Corrosion-resistant hybrid coatings based on graphene oxide–zirconia dioxide/epoxy system. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2016c; 67: 511–1520.10.1016/j.jtice.2016.08.008Suche in Google Scholar

Diouf D, Asmatulu R. Silanized graphene-based nanocomposite coatings on fiber reinforced composites against the environmental degradations. Paper presented at the ASME 2014 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, ASME Proceedings, Advances in Aerospace Technology, Paper No. IMECE2014-39818, pp. V001T01A031, 6 pages, Quebec, Canada, November 14–20, 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

El-Mahdy GA, Atta AM, Al-Lohedan HA. Synthesis and evaluation of poly (sodium 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropane sulfonate-co-styrene)/magnetite nanoparticle composites as corrosion inhibitors for steel. Molecules 2014; 19: 1713–1731.10.3390/molecules19021713Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

El Dessouky WI, Abbas R, Sadik WA, El Demerdash AGM, Hefnawy A. Improved adhesion of superhydrophobic layer on metal surfaces via one step spraying method. Arab J Chem 2017; 10: 368–377.10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.12.011Suche in Google Scholar

Fayyad EM, Sadasivuni KK, Ponnamma D, Al-Maadeed MAA. Oleic acid-grafted chitosan/graphene oxide composite coating for corrosion protection of carbon steel. Carbohydr Polym 2016; 151: 871–878.10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.06.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Galpaya D, Wang M, Liu M, Motta N, Waclawik ER, Yan C. Recent advances in fabrication and characterization of graphene-polymer nanocomposites. Graphene 2012; 1: 30–49.10.4236/graphene.2012.12005Suche in Google Scholar

Geim AK, Novoselov KS. The rise of graphene. Nat Mater 2007; 6: 183.10.1038/nmat1849Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Gomes A, da Silva Pereira M. Pulsed electrodeposition of Zn in the presence of surfactants. Electrochim Acta 2006; 51: 1342–1350.10.1016/j.electacta.2005.06.023Suche in Google Scholar

Gonçalves G, Baldissera A, Rodrigues Jr L, Martini E, Ferreira C. Alkyd coatings containing polyanilines for corrosion protection of mild steel. Synth Met 2011; 161: 313–323.10.1016/j.synthmet.2010.11.043Suche in Google Scholar

Gu L, Liu S, Zhao H, Yu H. Facile preparation of water-dispersible graphene sheets stabilized by carboxylated oligoanilines and their anticorrosion coatings. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015; 7: 17641–17648.10.1021/acsami.5b05531Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Hammer P, Dos Santos F, Cerrutti B, Pulcinelli SH, Santilli CV. Carbon nanotube-reinforced siloxane-PMMA hybrid coatings with high corrosion resistance. Prog Org Coat 2013; 76: 601–608.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2012.11.015Suche in Google Scholar

Hampden-Smith MJ, Kodas TT. Chemical vapor deposition of metals: Part 1. An overview of CVD processes. Chem Vapor Depos 1995; 1: 8–23.10.1002/cvde.19950010103Suche in Google Scholar

Han Y, Xu Z, Gao C. Ultrathin graphene nanofiltration membrane for water purification. Adv Funct Mater 2013; 23: 3693–3700.10.1002/adfm.201202601Suche in Google Scholar

Hayatdavoudi H, Rahsepar M. A mechanistic study of the enhanced cathodic protection performance of graphene-reinforced zinc rich nanocomposite coating for corrosion protection of carbon steel substrate. J Alloys Compd 2017; 727: 1148–1156.10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.08.250Suche in Google Scholar

Hikku G, Jeyasubramanian K, Venugopal A, Ghosh R. Corrosion resistance behaviour of graphene/polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposite coating for aluminium-2219 alloy. J Alloys Compd 2017; 716: 259–269.10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.04.324Suche in Google Scholar

Hirsch A, Englert JM, Hauke F. Wet chemical functionalization of graphene. A Chem Res 2012; 46: 87–96.10.1021/ar300116qSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

Hu J, Ji Y, Shi Y, Hui F, Duan H, Lanza M. A review on the use of graphene as a protective coating against corrosion. Ann J Mater Sci Eng 2014; 1: 16.Suche in Google Scholar

Huang C-Y, Tsai P-Y, Gu B, Hu W, Jhao J, Jhuang G-S, Lee Y-L. The development of novel sound-absorbing and anti-corrosion nanocomposite coating. ECS Trans 2016; 72: 171–183.10.1149/07217.0171ecstSuche in Google Scholar

Jafari Y, Ghoreishi S, Shabani-Nooshabadi M. Polyaniline/graphene nanocomposite coatings on copper: electropolymerization, characterization, and evaluation of corrosion protection performance. Synth Met 2016; 217: 220–230.10.1016/j.synthmet.2016.04.001Suche in Google Scholar