Abstract

This article analyses a specific strategy designed to include generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools in students’ written assignments. While we recognise that GenAI tools represent a challenge for teachers in terms of their classroom use and the development of digital literacy among students, we believe that banning them is not a viable option. In our view, students need to develop a sustainable, critical approach to these tools, informed by the need to be transparent. With this in mind, we have thus developed, tested and evaluated a protocol for language learners in two Swiss universities. In our experiment, students were allowed to use any online tools available for their written assignments, but they were required to clearly highlight in their texts any output derived from text generators (ChatGPT), machine translation tools (DeepL), online corpora and online dictionaries in their texts. They also had to report on their writing process in an additional, meta-analytical paragraph. After submitting their assignments, students were asked to answer a questionnaire investigating their use of, and attitude to, GenAI tools as well as their transparency in completing the task. The data gathered allowed us to gauge students’ trustworthiness as to their self-reported tool use and to determine whether our protocol could help teachers preserve the take-home written assignment in the GenAI era. Finally, the analysis yielded interesting insights into students’ use of GenAI in L2 writing and highlighted different ways in which teachers can foster more transparency. This innovative action-research study brings much-needed data and offers practical guidance to language teachers interested in GenAI.

1 Introduction

This article presents an action-research study carried out at two Swiss universities which evaluated different aspects of the inclusion of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) in students’ writing tasks. GenAI is the label used to describe different types of tools powered by AI and large language models (LLMs) which generate content, e.g. image, music, code or text. In this article, we will mainly refer to two GenAI tools: neural machine translation (NMT) tools such as DeepL, which have been largely researched in the language classroom (see Klimova et al. 2022), and the somewhat new addition to GenAI, namely chatbots like ChatGPT, Gemini or Copilot. Previous research has shown that many language tutors are reluctant to integrate GenAI tools into their teaching,[1] as they feel this may lead to students cheating, overusing the tools and not developing sufficient autonomous language skills.[2] Many colleagues, for example, have been feeling that the take-home writing assignment is no longer possible, as students tend to overuse GenAI tools and do not write on their own anymore (Tan et al. 2025).[3] Nonetheless, we believe that banning GenAI is not a viable solution, as students will use it anyway[4] and, more importantly, because they need to develop a sustainable, informed and critical use of these tools. We argue that fostering GenAI literacy for L2 communication is part of the language teacher’s mission and the strategy outlined in this article will contribute towards developing this framework. Reporting on a specific experiment in two Swiss higher education institutions, this article explores the following research questions: can the colour-code protocol devised and tested help save the take-home writing assignment? How truthful are students when they report on their use of tools – including GenAI – in take-home writing assignments? The data gathered also allows us to address a question that has been at the forefront of many teachers’ preoccupations: how do students use GenAI and other language tools when producing written work at home? We believe that many teachers are eager to find sustainable ways to integrate GenAI into their teaching practices and we hope that the positive results of our action-research study will provide a good example.

2 GenAI literacy and L2 writing

2.1 From MT literacy to GenAI literacy

In the last few years, a number of researchers have advocated the need for language learners to develop machine translation (MT) literacy (Cotelli Kureth and Summers 2023; Hellmich 2021; O’Neill 2019). Bowker and Buitrago Ciro (2019) argue that although very easy to manipulate (a simple question of copy and paste), MT tools can still cause serious problems to users who are not trained as translators. Different skills are needed including the ability to understand how these systems work, how one can pre-edit a text and post-edit MT output. Alongside more ethical considerations (Moorkens 2022), this can help users decide when it is advisable to use MT and how to use it more accurately. This awareness is crucial as evidence suggests that many users do not employ the tool to its full potential, for example when they carry out single-word searches (see Cotelli Kureth et al. 2023).

Research on neural MT output has also highlighted other important points to cover in MT literacy training, including the presence of bias (Vanmassenhove et al. 2021), machine translationese (De Clercq et al. 2021), errors, etc. MT literacy training also focuses on post-editing practices and the weaknesses of human post-editors, among which phenomena like false fluency, that is the fact that we tend to trust well-written texts based on their fluency rather than their actual meaning (Martindale and Carpuat 2018), and priming (Resende and Way 2021). We believe that, with the advent of text generators, the concept of MT literacy must be rethought and broadened to encompass other GenAI tools. For now, not much is known about ChatGPT output and the human-machine interaction with text generators, but we can assume that a large part of what we know about NMT systems will also apply to text generators. For one, both GenAI tools rely on LLMs and other similar technology to create content (Benites et al. 2023). This exposes them equally to the risk of biases as the latter are inherent in these systems (Hovy and Prabhumoye 2021). In early experiments with ChatGPT, several students reported that the GenAI tool had influenced their thinking, leading them to use sentences that did not fully match the ideas they had initially wished to convey (Fyfe 2023). False fluency thus seems to be an issue not only with MT but with all GenAI tools.

Researchers have proposed several models for GenAI literacy that intersect with MT literacy. Among these, the four-part GenAI system for communication described by Cardon and colleagues (2023) appears to be the most suitable for language learners. In this model, GenAI literacy is based on four main principles: “application” (users have adequate knowledge of the tools and their uses for various types of task), “agency” (users retain their ability to make decisions), “authenticity” (the norm of communication is human-to-human) and “accountability” (users are responsible for the content they produce with AI tools) (Cardon et al. 2023: 277–279). Transparency, the key word in this article, stems from authenticity and accountability. In other words, users need to be transparent in their use of AI tools when communicating so that they are fully accountable for the content produced, and that readers and listeners can adjust their expectations from the norm of human-to-human communication.

With this model in mind, we undertook this action-research study to garner more information on how to foster GenAI literacy and transparency among L2 learners and to include these new tools in existing teaching tasks, namely in take-home written assignments.

2.2 Using GenAI for L2 writing

There is clear evidence that the use of GenAI tools can be beneficial to L2 learners when the latter are faced with a writing task. Use of MT has been the focus of many studies, where MT helped to translate parts of texts (Chung and Ahn 2021) or was used to review text written directly in the L2 (Lee 2020). The results showed that using MT helped improve lexical range and grammatical accuracy (Wang and Ke 2022) and learners were able to produce more words (Tsai 2019).

The same seems to be the case for text generators like ChatGPT (see Athanassopoulos et al. 2023; Li et al. 2023), with the difference that these can be used in many different ways. Fitria (2023), Barrot (2023) and Su and colleagues (2023) have shown that the use of GenAI tools is easy and advantageous for students at several stages of the writing process (pre-, during and post task) but that it comes with limitations. Han and colleagues (2023) have examined the use of ChatGPT to revise an L2 text. Other studies have offered additional insight into the human-machine writing process with GenAI tools. Yan (2023: 13943) published an “exploratory investigation” based on a one-week EFL writing practicum at a Chinese university. This experiment shows ChatGPT’s great versatility for L2 writing, especially as an “all-in-one tool”, enabling users to generate ideas and content, to rephrase, check grammar and spelling and give feedback across languages. When examining students’ concerns, however, Yan (2023: 13959) concluded that “ChatGPT’s threats outweigh its merits”. Based on their own experience using the tool, Sirisathitkul (2023) advocates adopting a “slow writing” approach with ChatGPT, working sentence by sentence and with many iterations. Although not evidence-based, this approach is interesting as it allows users to maintain command of the writing process and thus it probably lowers the danger of false fluency.

All in all, despite lingering concerns, research has confirmed the benefits of guiding students’ use of GenAI tools in written assignments. Given that, outside the classroom, students will have access to these tools, it is crucial that they develop GenAI literacy. This can best be done when such tools are included and discussed in the teaching. It is with this in mind that we conducted the present action-research study.

3 Experimental setting: institutional context

3.1 HEIG-Vaud

The present study was conducted in the Business Administration section of the School of Engineering and Management (HEIG-VD) in Yverdon, which has 500 full-time and part-time BA students. English and German courses are part of the curriculum of Business Administration. All language skills are trained, with a focus on business communication. The present project was carried out for one semester (15 weeks) in 5 different German classes (12–21 students per class), at B2 level in the business communication classes and B2/C1 in the general German classes, all taught by one of the authors. The latter introduced GenAI tools through open discussions with her classes, broaching ethical issues and emphasising best practices. Students on these courses were allowed to submit a maximum of six (ungraded) assignments as practice for their end-of-semester exam, which included a writing task. Unlike in the exam, students were permitted to use various tools for their assignments but had to colour-code any tool output in their work. This allowed the teacher to highlight problematic vocabulary and grammar issues for her students and to discuss the use of tools in class. In total, 44 HEIG-VD students took part in the action-research study.

3.2 The Language Centre of the University of Neuchâtel (UniNE)

The second institution taking part in the study was the UniNE Language Centre (LC). LC courses are elective except for History and Philosophy BA students, who can validate credits in English for Academic Purposes (EAP) or German. The study was conducted for one semester in two general English courses (target level B1+ and B2) and three EAP courses (target level C1), including two intensive courses (28 h of tuition in two weeks). Four of the courses were taught by two of the authors, and the fifth one by another LC teacher who followed the same guidelines. For the two general English courses and the C1 semester course, students were asked to produce an ungraded take-home written assignment as part of the course evaluation. For the intensive C1 courses, the written assignments were an integral part of the course evaluation, counting as one third of the final grade. Consequently, they were graded using a rubric that included “self-awareness and tool use”.

Preparatory work for the written assignment consisted in classroom discussion of the typical structure of a discursive essay and the examination of model essay topics. Prior to that, all students enrolled on courses run by the UniNE Language Centre had been given a short introduction to online resources including online dictionaries, corpora and GenAI tools (Cotelli Kureth and Summers 2023). The introduction was designed to cover the main features of existing tools and to outline the best practices for language learning, such as the use of dictionaries or corpora – rather than machine translation tools – for word searches. Students were also made aware of technical and ethical concerns raised by their use of technology, including some of the weaknesses of the machine and its human post-editors, as well as the concept of scientific integrity. In total, 35 UniNE students took part in our action-research study.

3.3 Guidelines and experiment in autumn 2023 and 2024

In the autumn semester 2023 and 2024, students in both institutions were asked to produce different types of texts. For their English courses, they had to hand in one compulsory written assignment, namely a short essay on a given topic. For their German courses, they had to hand it at least two compulsory written assignments and could also use tools when preparing for their oral exams. All students were encouraged to use online tools for their assignments but were asked to reference them according to a number of guidelines, including the use of the following colour scheme for the tools employed at any point in the writing process:

in yellow: online dictionaries and corpora (Leo, Linguee, etc.);

in green: machine translation tools (DeepL, etc.);

in blue: automatic text production tools (ChatGPT, etc.);

in pink: AI writing assistance (Grammarly, Antidote, DeepL write, etc.).

In addition to their written assignments, UniNE students were asked to provide feedback on their writing process in the form of one short, meta-analytical paragraph (self-report) to be written in their L1 or L2. In the latter, they had to specify how they tackled the assignment, what tools they used, why and how they used them as well as sharing any insights gained. After submitting their texts, all students were asked to answer a questionnaire.

3.4 Data and evaluation

The experiment was evaluated by analysing different types of data. Firstly, after submitting their assignments, students were asked to answer a questionnaire on Qualtrics[5] investigating their use of GenAI tools and their transparency in completing the task (see 4.1 and 4.2). They were also required to provide feedback on the experiment as a whole. We collected 44 responses for HEIG-Vaud and 30 responses for UniNE. All the answers were anonymous (the only information required was the target level of the course) as we wanted students to report as truthfully as possible on their actual use of tools and on their transparency in colour-coding their texts. Some of the questions were multiple choice, and allowed us to examine quantitative data through descriptive statistical analysis. Two questions were open-ended. Students had to answer follow-up questions twice. As we only had a small number of quotes, their comments were collated. Two of the authors read them and gathered similar quotes in clusters, which allowed us to provide qualitative data through a thematic analysis.

Furthermore, we gathered 35 colour-coded texts and 30 meta-analytical paragraphs (self-reports) written by UniNE students, which offer invaluable information on how they employed GenAI tools. The texts themselves were not analysed but they were marked by the respective course teacher and sent back to the students. For the purpose of our experiment, we counted the number of highlighted passages and the number of tools mentioned. The meta-analytical paragraphs were collated and carefully read by two of the authors. Again, the main themes were identified separately by each author and then discussed and used as a framework for describing the data.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Overall success of the task and protocol

Responses to the questionnaire show that students were generally satisfied with the experiment. Contrary to what teachers sometimes fear (Barrett and Pack 2023), the vast majority of students thought that the writing assignment had helped them progress in their L2 competence. Only 6 % of them reported no progress, while 83 % stated that thinking critically about language had been useful.[6] This highlights students’ willingness to become more GenAI literate, as critical thinking is key to GenAI literacy (Walter 2024). In language learning, it has been shown that critical thinking is linked to students’ autonomy (Nosratinia and Zaker 2015). This highlights the importance of equipping students with the mental (e.g. self-awareness about their language skills, awareness of biases, hallucinations, false fluency, etc.) and physical (e.g. dictionaries, corpora, etc.) tools to critically assess GenAI output.

Most students seemed to appreciate, or at least understand the importance of, introspective reflection on language: 71 % reported that they liked to think about how they communicate in the L2.[7] This was further reflected in the meta-analytical paragraphs. About a third were very succinct, giving minimal information. Two thirds were longer and reported in depth on the students’ writing process and their tool use. Based on this feedback, we believe that language teachers should put more emphasis on teaching students about the writing process, as suggested by Kim and Danilina (2025), too. We feel this would improve their GenAI literacy, while providing them with more motivation to think about their communication in the L2. Feedback from students who were enthusiastic about their metacognitive effort shows that the latter was perceived as both positive and intrinsic to the learning process. When we asked why they enjoyed it, students noted that “it was part of their learning” and that “it helps to progress”.[8] Several students mentioned that it helped them produce more “natural-sounding” texts.

4.2 Self-report of students’ trustworthiness

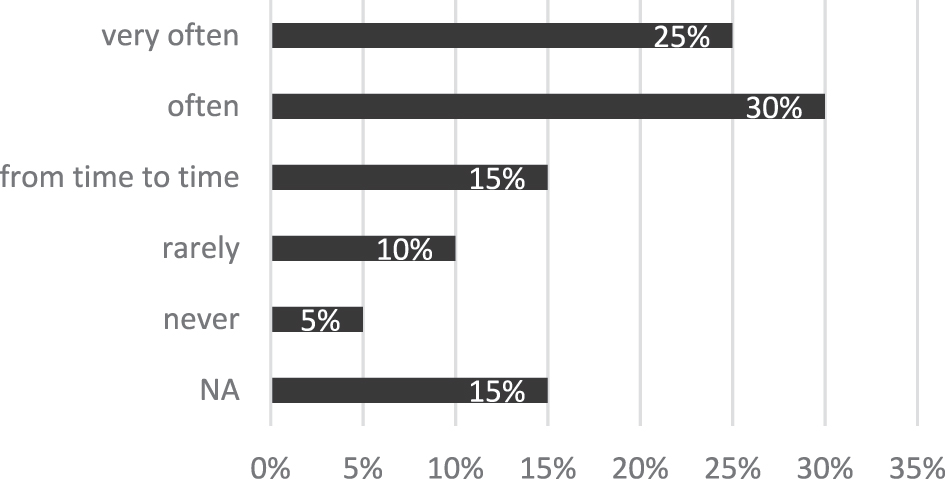

The main point of our questionnaire was to check whether students had been trustworthy when colour-coding their assignments as required, in other words, whether the latter reflected their actual use of tools. In a few cases, teachers were somewhat sceptical but on the whole, students seemed to be quite transparent, at least according to their self-reports (see Figure 1).

Answers to the question: ‘In the assignment you had to hand in, we asked you to indicate the tools that you used. Were you always transparent?’ (n = 70).

To get more precise data, we also asked students to report on how often they had been transparent. Among those who said they had not been transparent, only one admitted to never reporting their tool use and two others stated that they were rarely transparent (see Figure 2). Thus, most students, even when not 100 % transparent, still acknowledged some tool use in their assignments.

Answers from the 27 students who had reported not being transparent in the earlier question (see Figure 1).

The data in Figures 1 and 2 is consistent with the feelings the teachers had when reading their students’ work. The number of students who reported to be transparent (two thirds of the respondents) seems a good start but we would like to find ways to encourage even more transparency. Looking at students’ reasons for not reporting the truth can be very helpful. Some mentioned that they didn’t know (“vraiment je ne savais pas” (UniNE), “Je n’étais pas au courant” (HEIG-VD)),[9] others did not find the task important enough (“ce n’est pas necessaire” (UniNE), “J’oublie” (HEIG-VD), “J’ai la flemme” (HEIG-VD), “Je n’y pense pas” (HEIG-VD)).[10] An obvious way to avoid such attitudes is to make GenAI literacy and awareness of the writing process an inherent part of the evaluation. We implemented this in the C1 intensive course, where a newly designed rubric was used to grade the assignments and 100 % of students said that they had been transparent. Finally, a few other students mentioned experiencing a form of fear linked to attitudes towards the tools: “peur du jugement” (UniNE), “Car je me demande toujours si nous avons le droit d’utiliser ce genre de sources pour nos cours” (HEIG-VD).[11] This could probably be offset by a more thorough discussion of tools and the inclusion of a few guided writing tasks with GenAI tools in the language classroom.

We also wanted to know if lack of self-reported tool use was indicative of apprehension about the teacher’s assessment of the output and we asked students about this. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, “fear of judgement” seemed to be one of the students’ reasons for not being totally transparent. A recent study has shown that this fear is justified, as educators seem to assess a text more harshly when the author acknowledges they have produced it with the help of GenAI (Tan et al. 2025). In our experiment, teachers clearly communicated to the students that, as long as they used tools sustainably, their tool use would not have a negative impact on their assessment. Nonetheless, students seem to have somehow misunderstood this message. As shown in Figure 3, they were quite ambivalent about this: a little over a third had no opinion, a small quarter thought tool use would not interfere with the teacher’s assessment while a little over a third believed that teachers would view their work differently if they acknowledged their tool use.

Answers to the question ‘Do you think that the fact of mentioning the sources changes the way your teacher corrects your text?’ (n = 70).

We also asked students to explain why they thought their teacher would have a different attitude towards their assignments if they mentioned the tools used. Some answers were very useful and helped us devise ways to enhance transparency. Here are some of the most interesting comments (in the original French and in English translation):

Plusieurs enseignants ne veulent pas que nous utilisons les outils comme chat gpt parce qu’ils pensent que c’est de la tricherie, mais dans le monde professionnel beaucoup de personne utilise cette aide. Donc je pense que c’est un plus pour avoir des idées (bien évidemment il existait avant chat gpt d’autres outils utiles pour tout et n’importe quoi), et je suis pour que les élèves s’aident avec ces différents outils. [Several teachers don’t want us to use tools like ChatGPT because they think it is cheating, but in a professional environment a lot of people use this help. So, I think that it is a plus to have ideas (of course before ChatGPT there were other useful tools for one purpose or another), and I am in favour of students getting help from these different tools.] (HEIG-VD)

Je pense que nous devons apprendre comment bien utiliser ces outils car ils peuvent nous être utiles dans le domaine académique et au-delà. [I think that we need to learn how to use these tools as they can be useful in an academic context and beyond.] (UniNE)

Elle est plus sévère. [She is more strict.] (HEIG-VD)

Si nous utilisons l’IA, l’enseignant se dit sûrement que ce n’est pas nous qui a écrit le texte, mais une intelligence artificielle. Elles risquent donc d’être beaucoup plus indulgente avec notre travail. [If we use AI, the teacher will most likely think that AI wrote the text and not us. They might be much more lenient with our work as a result.] (HEIG-VD)

Parce qu’elle peut voir où sont nos difficultés et ainsi elle peut mieux nous aider. [Because she can see where our difficulties lie and thus she can provide better help.] (HEIG-VD)

Parce que corriger une machine semble être une perte de temps peut-être. [Because correcting a machine may seem like a waste of time.] (UniNE)

Parce que c’est considéré comme moins de travail. [Because it is seen as less work.] (UniNE)

Chatgpt n’ai pas une belle image, ça parait comme étant la facilité et pas d’effort fourni. [ChatGPT does not have a good image, it looks like it is too easy and there was no effort involved.] (HEIG-VD)

Although contradictory at times (examples 3 and 4), these comments offer interesting insights into how to speak to students about tool use (including GenAI) in their L2 writing. Examples 1 and 2 show that students recognise the value of GenAI literacy, especially when entering the job market. Emphasising this point at the onset of a discussion on GenAI tools may thus be worthwhile. “Severity” or “lack of severity” should also be explained, especially with regard to what is expected from students. Teachers can rely on the concept of “authenticity” (Cardon et al. 2023) and discuss the underlying expectations of genuine communication in different contexts, including the language classroom. In particular, teachers could do more to dispel some students’ belief about the need to submit error-free work and illustrate this by means of a revised rubric for written assignments and examples of successful written production which may still contain spelling and minor grammatical mistakes. This could contribute to changing students’ attitudes towards the possibility of using GenAI tools in their L2 writing. An excellent argument supporting the pedagogical benefits of the colour-coding scheme tested can be found in example 5. As illustrated by the HEIG-VD teacher’s experience, students taking part in the experiment recognised both the value of making mistakes (subsequently corrected by the teacher) and that of highlighting passages where they needed help (as a way to alert the teacher to areas requiring further practice). Finally, the last three comments (6–8) point to the importance of discussing sustainable uses of GenAI tools with our students.

These results have given us a better understanding of ways to develop our students’ GenAI literacy. Thus, we believe that integrating tool use and awareness of the writing process into the evaluation of assignments (whether graded or not) would help foster more transparency. In addition to stressing the importance of acknowledging individual use of GenAI tools, a class discussion on GenAI literacy should emphasise its relevance for students’ future careers and the pedagogical benefits of being transparent, and include pointers on how to develop a sustainable use of tools. The concept of “slow writing with ChatGPT” (Sirisathitkul 2023) could provide an interesting framework. However, more research is needed to provide students with evidence-based “best practices” for using GenAI in their writing tasks.

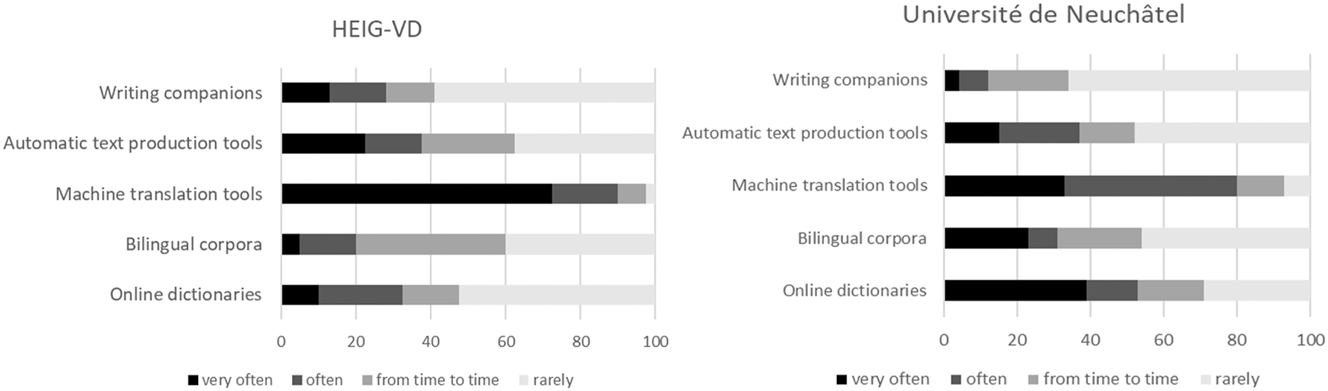

Responses (in percentages) to the question: “How often do you use the following tools” from the surveys in the two universities (HEIG-VD = 40 responses; UniNE = 30 responses).

4.3 Student use of AI

In our study, we surveyed students on the tools used in their writing and we were somewhat surprised to see that, in autumn/winter 2023, text generators like ChatGPT had not taken the lead. For both universities, MT tools were the most used: 80 % of the UniNE students and 90 % of the HEIG-VD students surveyed used them (very) often (see Figure 4).

Interestingly, nearly 40 % of UniNE students reported using online dictionaries very often, significantly more than HEIG-VD students. Bilingual corpora, like Linguee, were also cited more frequently by UniNE students. This is not entirely surprising as all UniNE students had received repeated guidance on the use of bilingual corpora rather than MT for single-word searches, as a result of research showing this misinformed use of MT to be prevalent among Swiss students (Cotelli Kureth et al. 2023). In contrast, writing companions such as DeepL Write and text generators like ChatGPT seemed to be better known to HEIG-VD students. As some HEIG-VD part-time students are already working, they are more likely to use GenAI tools in the workplace, which could explain their greater knowledge of these tools.

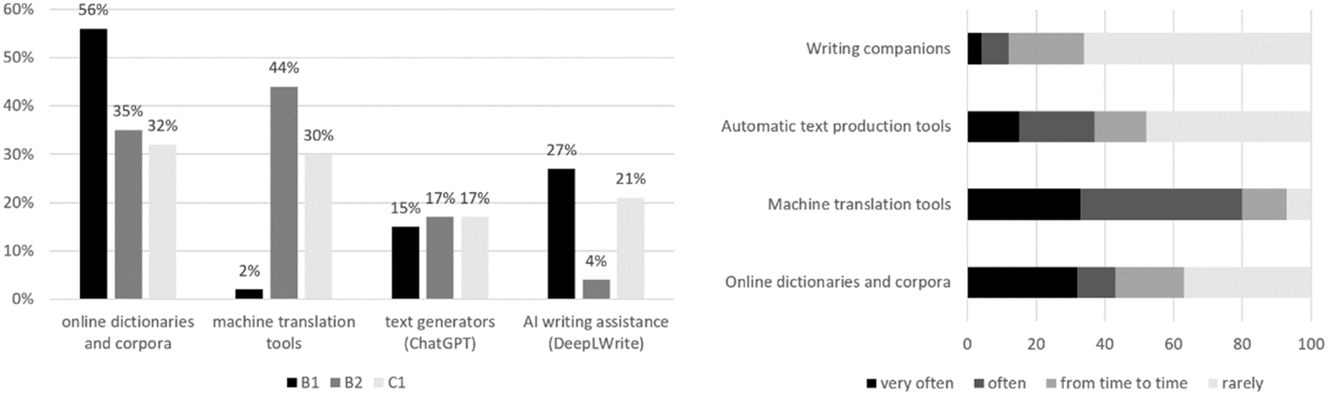

It is interesting to compare the questionnaire feedback with students’ actual use of the tools as illustrated by their assignments. For the 34 UniNE students, we recorded each mention of tool use according to the colour scheme employed in their assignments (see Figure 5).

Tool use as indicated in students’ assignments (left) and self-reported use in the questionnaire (right).

The bar chart on the left shows the number of mentions (in percentages) of each type of tool in the students’ assignments (325 mentions in 34 texts). The bar chart on the right is the same as that shown in Figure 4, but with online dictionaries and bilingual corpora presented together to enhance comparability.

The first striking finding is the significant difference between the levels surveyed, especially concerning students’ use of dictionaries and MT tools, which cannot be attributed to different teaching styles, as the presentation on online tools was done by the same person in all the classes. Also, the sample suggests that more advanced learners use tools much more than lower-intermediate ones: there were about 6,7 mentions of tool per text for the B1+ students, 9 for B2 students and 11 for C1 students. Looking at the two charts, it is obvious that in both, the most commonly used tools were online dictionaries, corpora and MT tools. AI writing assistants were somewhat underrepresented in students’ self-reports. The data shows that ChatGPT was regularly used by students in their texts (16/37 students), which is consistent with what they reported in the questionnaire (slightly more than half used it rarely). The chart, however, does not take into account the length of the passages highlighted. While those derived from online dictionaries and corpora were almost always very short (one or two words), those produced with the help of ChatGPT were much longer, usually at least a sentence and a few times, a whole paragraph, or in one case, the whole text. These passages were also longer than MT output (usually a phrase or a sentence). Our sample is small but we can draw the conclusion that a more thorough quantitative and qualitative analysis of colour-coded essays would provide interesting insights into students’ actual use of tools and evidence-based ideas for better GenAI literacy training.

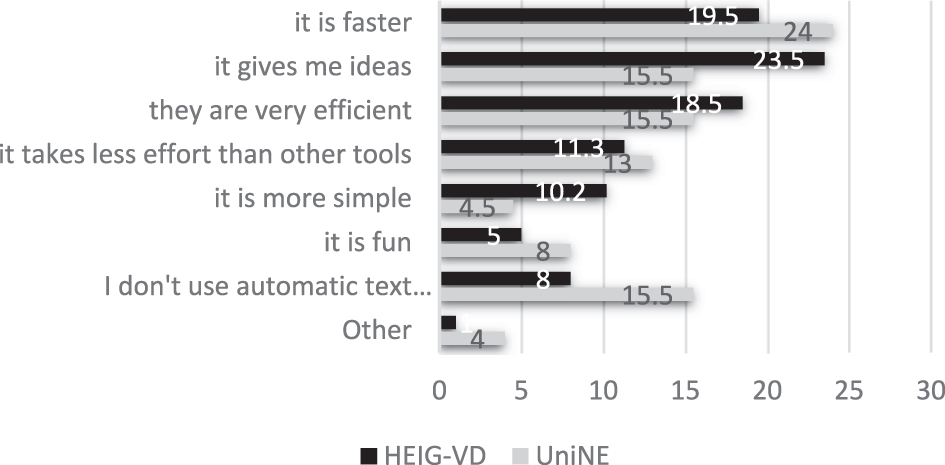

Feedback on how students employed text generators like ChatGPT shows that they used them at most stages of the writing process (see Figure 6). While a small percentage of students ticked all the options, most respondents only selected one or two uses of the tool: mainly to generate ideas or create an outline for HEIG-VD students, and to generate ideas, create an outline and revise text for UniNE learners. It is worth noting that only a minority of students (30 % for UniNE and 15 % for HEIG-VD) used ChatGPT to produce the text for them. Other studies on student use of GenAI show similar results. For example, Finnish Business students in a university of applied sciences used ChatGPT primarily to clarify issues and challenging topics, to generate ideas and to edit their own writing (Suonpää et al. 2024). In our own setting, this is understandable as students know that written assignments are designed as writing practice, with no pressure to produce perfect output. We believe that emphasizing this point even more could help frame the use of GenAI tools in such assignments.

Students’ answers (in percentages) to the question: ‘For which part of the writing process do you use automatic text production tools (like ChatGPT, etc.)?’. Students were allowed to select several options (HEIG-VD = 53 responses; UniNE = 52 responses; 12 students did not answer the question).

Several UniNE and HEIG-VD students mentioned other uses of text generators. These included translation, asking for information about language learning (e.g. about grammar), and verifying lexical accuracy.

Feedback on why students used text generators like ChatGPT (see Figure 7) shows little consensus, as answers are quite evenly distributed, with slightly more answers (about one fourth of the answers) for the first two options. Overall, however, students seemed to appreciate the fact that text generators allowed them to do things more quickly. They also appeared to enjoy the creative side of the tool, a finding supported by other studies on university students (Xiao and Zhi 2023).

Answers (in percentages) to the question: ‘Why do you use automatic text production tools?’. Students were allowed to select several options (HEIG-VD = 95 responses; UniNE = 64 responses; 4 students did not answer the question).

All in all, these results show a mitigated use of text generators for language learning purposes by Swiss students. For each subsequent question, a substantial number of students (especially UniNE students) mentioned they did not employ these tools. We predict that this may change in the coming years and we will keep monitoring our learners’ use of tools.

Based on the evidence gathered so far, when it comes to GenAI use, our students seem to match different profiles ranging from more receptive to more resistive students (Yan et al. 2024). Yan and colleagues (2024) who propose four different student profiles regarding use of GenAI, show that “early-adopters” (those who have a pragmatic attitude towards the technology) have sometimes developed an expert critical use of GenAI tools. We believe that teachers should rely more on these early-adopters and enlist their help to bridge the technological gap between students. Moreover, teachers themselves could learn from students’ best practices.

4.4 Students’ self-reports on their writing process (UniNE)

Students’ responses to the task varied broadly, both in terms of the quality of their output (written assignments) and that of their self-reports (meta-analytical paragraphs). Generally speaking, their use of online tools to enhance their writing led to overall better assignments and less need for teacher feedback on the mechanics of writing compared to assignments on past language courses. In some cases, based on their overall knowledge of their students’ skills, teachers could detect clear discrepancies between the students’ levels of English in classroom interactions and that of their written English, as displayed by their written assignments. In a few of these cases, a comparison of the written assignment and the student’s self-report suggests that they may not have been fully transparent as to their use of GenAI tools. In a different example, there is a clear correlation between the student’s limited use of tools and the level of their written output, as indicated by the presence of repeated grammar, vocabulary and spelling errors.

Students’ self-reports display a wide range of responses to the task of referencing tool use and discussing their writing process. In some cases, students chose to write about their writing process solely in terms of structuring their ideas for the assignment, without including any information about the tools used and how they wrote the text. Other students did the opposite, listing the tools used with little or no feedback on their actual writing process. In a couple of cases, the self-reports suggest that the students in question may have misunderstood the guidelines altogether. Nonetheless, the majority of self-reports (written either in English or in French) offer valuable insights into the students’ use of, and attitudes towards, the online tools available, in particular GenAI.

At B1+ level, only four of the seven students on the course chose to provide feedback in the form of a meta-analytical paragraph as requested, which suggests that the class may have found the task of critical self-reflection more intimidating at this level, despite having the option to write in French. Two of these (students B1.1 and B1.4) mentioned using translation (Google Translate and Reverso) but relying mainly on their own English vocabulary. In student B1.1’s words: “When I write a short text like this, I try to write it with the words I know”. Student B1.2, on the other hand, reported using a more complex strategy, which consisted in listing the arguments in French first, writing the first draft in English with the aid of tools, then using automatic correction and a friend’s help to produce the final version.

At B2 level, all nine students on the course provided feedback on their writing process, listing DeepL, ChatGPT, Google Translate, Linguee, Leo and WordReference as the tools used. Reported use of DeepL to perform individual word/phrase searches shows that some students still misuse the technology, despite the sustained effort by the UniNE LC to raise awareness of GenAI tools and their uses (see Cotelli Kureth and Summers 2023). ChatGPT was mentioned by four out of the nine students taking the course, with three of them citing it as an error correction tool used to “correct grammatical mistakes”, “reformulate”[12] or proofread sentences. Two students also reported using it to “generate”[13] ideas, either in English or French. Despite the increasing variety and level of sophistication of the language tools made available in recent years, Google Translate seems to have remained a go-to resource for some learners, as illustrated by student B2.3’s self-report: “I often write first in English, and I like to enter what I wrote in English into Google translate to see if it means something in French and then enter what I got to see if Google translate puts things differently in English”. Helmich (2021) reports similar uses of Google Translate. Google Translate was also mentioned by students B1.4 and B2.7 as a word search tool and listed by student B2.8 with no explanation for how or why the tool was used. The remaining tools cited appear to have been used in similar ways, mainly as translation tools.

At C1 level, ten out of the eleven students on the course wrote an accompanying meta-analytical paragraph, the eleventh student providing it on resubmitting the assignment at the teacher’s request. Despite their more advanced level, half of the students chose to write their feedback in French, a number similar to the B2 level class. Like their B2-level peers, C1 students reported using DeepL (or, in one case, DeepL Write), ChatGPT or simply Google but also monolingual resources such as Grammarly and the online Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary.[14] Again, the feedback shows some remaining confusion as to the best ways of using DeepL, with one student citing it as a word search tool instead of a dictionary. Six students mentioned employing ChatGPT, for reasons ranging from using it “to counter my arguments” (student C1.7) to getting “help […] in creating better sentences” (student C1.9) and having it “count the number of words or address potential mistakes in my ideas (not in my content)” (student C1.11). Another student reported using Google and ChatGPT in much vaguer terms, in order to “search for information”[15] (student C1.10). Yet another student, a first-time user of the tool, misunderstood – at least from the class teacher’s perspective – the point of the exercise by having ChatGPT write the entire assignment. The student’s self-report (in French) contains a candid retelling of the experience, showing how ChatGPT was asked to produce a continuous text featuring an adequate thesis statement and examples and how “it struggled to produce an interesting thesis” despite repeated prompting. Nevertheless, the student’s assessment of the tool was ultimately positive: “Very effective nonetheless”[16] (student C1.6). Requested by the class teacher to resubmit a new essay “of their own”[17] using the resources available as additional aid only, the student was happy to comply and accompanied his second submission by apologies and the comment that “I did tell myself that this wasn’t quite right”.[18] This is a telling example of the unease which teachers and students alike may experience when using GenAI in the absence of clear guidelines.

Some students’ self-reports display what may be seen as a healthy critical attitude towards the tools used, in particular ChatGPT. One C1 student made a case for their use of DeepL Write and ChatGPT as a means of learning and “improving my writing in English” and not just of “transforming my writing or the content” (student C1.9). On a parallel, intensive C1 course, where six out of the seven students provided feedback, one learner expressed similar caution, noting that: “instead of immediately turning to ChatGPT for assistance, I generate my own ideas” and that ChatGPT “often provides the same arguments I had already considered, leading me to reflect on the capabilities of technology” (student Int.C1.1). Another student on this course made a similar analysis of the merits of AI tools in their self-report, observing that use of technology may lead to loss of agency if learners practising writing allow technology to do the work in their stead (student Int.C1.6). Unlike the other language learners surveyed, two of the students who reported using ChatGPT on this course also provided the full transcripts of their ChatGPT prompts (students Int.C1.2 and Int.C1.3). In student Int.C1.2’s words, “I […] wanted to be fully transparent with my writing process for this assignment”. Students on this course also mention using DeepL Write (three mentions), WordReference, Reverso and Skell[19] for translation and proofreading purposes as well as to search for collocations.

Generally speaking, most learners surveyed showed increasing awareness of a wide range of online learning tools, from the more traditional online dictionaries and corpora to MT tools and the latest GenAI developments. This is probably both a consequence of these tools becoming better known to the general public and acquiring a growing number of users in academia as elsewhere and, in this specific context, the result of our efforts in both universities to increase digital (in particular GenAI) literacy among our language learners over the last few years. Nevertheless, students’ self-reports suggest that more needs to be done in terms of helping learners to gain a better understanding of L2 writing in general and develop a clearer sense of how to make the most of the language tools available.

5 Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that with the right guidelines and adequate discussion of GenAI tools, the take-home written assignment can still be beneficial to students. In response to fears voiced by European colleagues, our experiment also shows that written assignments can continue to be used as one area of course assessment on condition that the evaluation of students’ language proficiency takes into account additional parameters derived from GenAI literacy. We believe that making GenAI skills and awareness of the writing process an inherent part of the standard rubric employed for the assessment of written assignments would help foster more transparency and, thus, a more sustainable use of GenAI tools.

Based on the questionnaire feedback, we predict that classroom discussion of language tools including GenAI will be well received by most students and can contribute to improving their GenAI literacy as well as their L2 skills, in this particular case, their L2 writing. In this respect, our research findings suggest that learners need both guidance and reassurance. More specifically, based on our analysis, students need to be reminded that:

they need not provide error-free texts;

assignments are exercises designed to test their L2 writing proficiency;

their L2 writing proficiency includes sustainable and critical use of GenAI tools as well as awareness of the writing process;

sustainable use of GenAI tools will be crucial in professional settings.

Although the work described here can be viewed as only one component of what should be a broader framework for the integration of new technologies into the language classroom, we believe that a transparent use of GenAI tools in written assignments is an important first step towards developing practices that are effective, ethical and respectful of academic values.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our students for agreeing to take part in the experiment presented here and for granting us permission to cite their views. We also wish to be as transparent as possible as to our use of GenAI tools in writing this article. We used DeepL to help translate a few paragraphs into English, which were then thoroughly post-edited by the authors. The AI-powered application https://app.ludwig.guru/, online dictionaries (in particular Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary) and corpora (https://skell.sketchengine.eu/) were occasionally employed to check collocations. The whole text was thoroughly proofread by the three authors.

References

Alm, Antonie & Louise Ohashi. 2024. A worldwide study on language educators’ initial response to ChatGPT. Technology in Language Teaching & Learning 6(1). 1–23. https://doi.org/10.29140/tltl.v6n1.1141.Suche in Google Scholar

Athanassopoulos, Stavros, Polyxeni Manoli, Gouvi Maria, Lavidas Konstantinos & Vassils Komis. 2023. The use of ChatGPT as a learning tool to improve foreign language writing in a multilingual and multicultural classroom. Advances in Mobile Learning Educational Research 3(2). 818–824. https://doi.org/10.25082/AMLER.2023.02.009.Suche in Google Scholar

Barrett, Alex & Austin Pack. 2023. Not quite eye to A.I.: Student and teacher perspectives on the use of generative artificial intelligence in the writing process. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 20. Art no. 59 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00427-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Barrot, Jessie S. 2023. Using ChatGPT for second language writing: Pitfalls and potentials. Assessing Writing 57. 100745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2023.100745.Suche in Google Scholar

Benites, Fernando, Alice Delorme Benites & Chris M. Anson. 2023. Automated text generation and summarization for academic writing. In Otto Kruse, Christian Rapp, Chris M. Anson, Kalliopi Benetos, Elena Cotos, Ann Devitt & Antonette Shibani (eds.), Digital writing technologies in higher education. Theory, research, and practice, 279–301. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-3-031-36033-6_18Suche in Google Scholar

Bowker, Lynne & Jairo Buitrago Ciro. 2019. Machine translation and global research: Towards improved machine translation literacy in the scholarly community. Leeds: Emerald Publishing.10.1108/9781787567214Suche in Google Scholar

Cardon, Peter, Carolin Fleischmann, Jolanta Aritz, Minna Logemann & Jeanette Heidewald. 2023. The challenges and opportunities of AI-assisted writing: Developing AI literacy for the AI age. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly 86(3). 235–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/23294906231176517.Suche in Google Scholar

Chung, Eun Seon & Soojin Ahn. 2021. The effect of using machine translation on linguistic features in L2 writing across proficiency levels and text genres. Computer Assisted Language Learning 35(9). 2239–2264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1871029.Suche in Google Scholar

Cotelli Kureth, Sara, Alice Delorme Benites, Mara Haller, Hasti Noghrechi & Elizabeth Steele. 2023. “I looked it up in DeepL”: Machine translation and digital tools in the language classroom. In Nicolas Froeliger, Claire Larsonneur & Giuseppe Sofo (eds.), Traduction humaine et traitement automatique des langues: Vers un nouveau consensus ?/Human translation and natural language processing : Towards a new consensus? 81–96. Venice: Edizioni Ca’Foscari.10.30687/978-88-6969-762-3/006Suche in Google Scholar

Cotelli Kureth, Sara, Alice Delorme Benites, Caroline Lehr, Hasti Noghrechi, Elizabeth Steele & Elana Summers. 2025. Comment développer la littéracie digitale des enseignant-es et des apprenant-es? Conclusions du projet ‘Digital Literacy in University Contexts’. Babylonia 1. 54–57. https://doi.org/10.55393/babylonia.v1i.510.Suche in Google Scholar

Cotelli Kureth, Sara & Elana Summers. 2023. Tackling the elephant in the language classroom: Introducing machine translation literacy in a Swiss language centre. Language Learning in Higher Education 13(1). 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1515/cercles-2023-2015.Suche in Google Scholar

De Clercq, Orphée, Gert de Sutter, Rudy Loock, Bert Cappelle & Koen Plevoets. 2021. Uncovering machine translationese using corpus analysis techniques to distinguish between original and machine-translated French. Translation Quarterly 101. 21–45.Suche in Google Scholar

Delorme Benites, Alice, Sara Cotelli Kureth, Caroline Lehr & Elizabeth Steele. 2021. Machine translation literacy: A panorama of practices at Swiss universities and implications for language teaching. In Naouel Zoghlami, Cédric Brudermann, Cedric Sarré, Muriel Grosbois, Linda Bradley & Sylvie Thouësny (eds.), CALL and professionalisation: Short papers form EUROCALL 2021, 80–87. Paris: Research-Publishing.net.10.14705/rpnet.2021.54.1313Suche in Google Scholar

Fitria, Tira Nur. 2023. Artificial intelligence (AI) technology in OpenAI ChatGPT application: A review of ChatGPT in writing English essay. Journal of English Language and Teaching 12(1). 44–58. https://doi.org/10.15294/elt.v12i1.64069.Suche in Google Scholar

Fyfe, Paul. 2023. How to cheat on your final paper: Assigning AI for student writing. AI & Society 38. 1395–1405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01397-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Groves, Mike & Klaus Mundt. 2021. A ghostwriter in the machine? Attitudes of academic staff towards machine translation use in internationalised higher education. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 50. 1475–1585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2021.100957.Suche in Google Scholar

Hamza, Anissa, Nicolas Molle & Guillaume Nassau. 2024. Les Outils de Traduction Automatiques dans la classe de langue : « rien n’est parfait mais ça ne veut pas dire qu’ils sont inutiles». Presented at the conference ‘Perspectives didactiques pour la traduction automatique dans l’apprentissage des langues’, on April 5, 2024, at the Université de Lorraine, Nancy.Suche in Google Scholar

Han, Jieun, Haneul Yoo, Yoonsu Kim, Junho Myung, Minsun Kim, Hyseung Lim, Juho Kim, Tak Yeon Lee, Hwajung Hong, So-Yeon Ahn & Alice Oh. 2023. RECIPE: How to integrate ChatGPT into EFL writing education. In Proceedings of the Tenth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale (L@S ’23), July 20–22, 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark. ACM, New York, NY, USA. 8 pages.Suche in Google Scholar

Hellmich, Emily A. 2021. Machine translation in foreign language writing: Student use to guide pedagogical practice. Apprentissage des Langues et Systèmes d’Information et de Communication (Alsic) 24(1).10.4000/alsic.5705Suche in Google Scholar

Hovy, Dirk & Shrimai Prabhumoye. 2021. Five sources of bias in natural language processing. Language and Linguistics Compass 15(8). e12432. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12432.Suche in Google Scholar

Kim, Jade & Elena Danilina. 2025. Towards inclusive and equitable assessment practices in the age of GenAI: Revisiting academic literacies for multilingual students in academic writing. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2025.2456223.Suche in Google Scholar

Klimova, Blanka, Marcel Pickhart, Alice Delorme Benites, Caroline Lehr & Christina Sanchez-Stockhammer. 2022. Neural machine translation in foreign language teaching and learning: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies 28(1). 663–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11194-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Sangmin-Michelle. 2020. The impact of using machine translation on EFL students’ writing. Computer Assisted Language Learning 33(3). 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1553186.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Xiaying, Belle Li & Su-Je Cho. 2023. Empowering Chinese language learners from low-income families to improve their Chinese writing with ChatGPT’s assistance afterschool. Languages 8. 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040238.Suche in Google Scholar

Martindale, Marianna & Marine Carpuat. 2018. Fluency over adequacy: A pilot study in measuring user trust in imperfect MT. Proceedings of AMTA 2018 1. 13–25.Suche in Google Scholar

Moorkens, Joss. 2022. Ethics and machine translation. In Dorothy Kenny (ed.), Machine translation for everyone. Empowering users in the age of artificial intelligence, 121–140. Geneva: Language science press.Suche in Google Scholar

Nosratinia, Mania & Alireza Zaker. 2015. Boosting autonomous foreign language learning: Scrutinizing the role of creativity, critical thinking, and vocabulary learning strategies. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature 4(4). 86–97. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.n.4p.86.Suche in Google Scholar

O’Neill, Errol M. 2019. Online translator, dictionary, and search engine use among L2 students. CALL-EJ 20(1). 154–177.Suche in Google Scholar

Resende, Natália & Andy Way. 2021. Can Google translate rewire your L2 English processing? Digital 1(1). 66–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital1010006.Suche in Google Scholar

Sirisathitkul, Chitnarong. 2023. Slow writing with ChatGPT: Turning the hype into a right way forward. Postdigital Science and Education 6. 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-023-00441-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Su, Yanfang, Yun Lin & Chun Lai. 2023. Collaborating with ChatGPT in argumentative writing classrooms. Assessing Writing 57. 100752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2023.100752.Suche in Google Scholar

Suonpää, Maija, Jutta Heikkilä & Ana Dimkar. 2024. Students’ perceptions of generative AI usage and risks in a Finnish higher education institution. In INTED2024 Proceedings. pp. 3071–3077. alencia: International Academy of Technology, Education and Development. https://library.iated.org/publications/INTED2024.10.21125/inted.2024.0825Suche in Google Scholar

Tan, Xiao, Chaoran Wang & Wei Xu. 2025. To disclose or not to disclose: Exploring the risk of being transparent about GenAI use in second language writing. Applied Linguistics XX. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amae092.Suche in Google Scholar

Tsai, Shu-Chia. 2019. Using google translate in EFL drafts: A preliminary investigation. Computer Assisted Language Learning 32(5–6). 510–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1527361.Suche in Google Scholar

Vanmassenhove, Eva, Dimitar Shterionov & Matthew Gwilliam. 2021. Machine translationese: Effects of algorithmic bias on linguistic complexity in machine translation. Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume, 2203–2213. Kerrville, TX: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2021.eacl-main.188Suche in Google Scholar

Vinall, Kimberley & Emily A. Hellmich. 2021. Down the rabbit hole: Machine translation, metaphor, and instructor identity and agency. Second Language Research & Practice 2(1). 99–118.Suche in Google Scholar

Walter, Yoshija. 2024. Embracing the future of artificial intelligence in the classroom: The relevance of AI literacy, prompt engineering, and critical thinking in modern education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 21. 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00448-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Jian & Xinli Ke. 2022. Integrating machine translation into EFL writing instruction: Process, product and perception. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 13(1). 125–137. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1301.15.Suche in Google Scholar

Xiao, Yangyu & Yuying Zhi. 2023. An exploratory study of EFL learners’ use of ChatGPT for language learning tasks: Experience and perceptions. Languages 8(3). 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030212.Suche in Google Scholar

Yan, Da. 2023. Impact of ChatGPT on learners in a L2 writing practicum: An exploratory investigation. Education and Information Technologies 28. 13943–13967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11742-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Yan, Yunying, Jinwen Luo, Miaoyan Yang, Runde Yang & Jiayin Chen. 2024. From surface to deep learning approaches with generative AI in higher education: An analytical framework of student agency. Studies in Higher Education 49(5). 817–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2327003.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Integration, collaboration, friendship as core messages for younger generations

- Research Articles

- Research practice and culture in European universities’ Language Centres. Results of a survey in CercleS member institutions

- Language practices in the work communities of Finnish Language Centres

- Fostering transparency: a critical introduction of generative AI in students’ assignments

- Expert versus novice academic writing: a Multi-Dimensional analysis of professional and learner texts in different disciplines

- Raising language awareness to foster self-efficacy in pre-professional writers of English as a Foreign Language: a case study of Czech students of Electrical Engineering and Informatics

- Does an autonomising scheme contribute to changing university students’ representations of language learning?

- Investigating the relationship between self-regulated learning and language proficiency among EFL students in Vietnam

- Students’ perspectives on Facebook and Instagram ELT opportunities: a comparative study

- Designing a scenario-based learning framework for a university-level Arabic language course

- Washback effects of the Portuguese CAPLE exams from Chinese university students and teachers’ perspectives: a mixed-methods study

- Students’ perception of the impact of (meta)linguistic knowledge on learning German

- Language policy in Higher Education of Georgia

- Activity Reports

- Intercomprehension and collaborative learning to interact in a plurilingual academic environment

- Teaching presentation skills through popular science: an opportunity for a collaborative and transversal approach to ESP teaching

- Japanese kana alphabet retention through handwritten reflection cards

- Decolonising the curriculum in Japanese language education in the UK and Europe

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Integration, collaboration, friendship as core messages for younger generations

- Research Articles

- Research practice and culture in European universities’ Language Centres. Results of a survey in CercleS member institutions

- Language practices in the work communities of Finnish Language Centres

- Fostering transparency: a critical introduction of generative AI in students’ assignments

- Expert versus novice academic writing: a Multi-Dimensional analysis of professional and learner texts in different disciplines

- Raising language awareness to foster self-efficacy in pre-professional writers of English as a Foreign Language: a case study of Czech students of Electrical Engineering and Informatics

- Does an autonomising scheme contribute to changing university students’ representations of language learning?

- Investigating the relationship between self-regulated learning and language proficiency among EFL students in Vietnam

- Students’ perspectives on Facebook and Instagram ELT opportunities: a comparative study

- Designing a scenario-based learning framework for a university-level Arabic language course

- Washback effects of the Portuguese CAPLE exams from Chinese university students and teachers’ perspectives: a mixed-methods study

- Students’ perception of the impact of (meta)linguistic knowledge on learning German

- Language policy in Higher Education of Georgia

- Activity Reports

- Intercomprehension and collaborative learning to interact in a plurilingual academic environment

- Teaching presentation skills through popular science: an opportunity for a collaborative and transversal approach to ESP teaching

- Japanese kana alphabet retention through handwritten reflection cards

- Decolonising the curriculum in Japanese language education in the UK and Europe