Abstract

German university degrees, at least in some countries, offer students only German literature courses in addition to language courses. Linguistics is often not a core component of German degree programmes. As a result, students who are not familiar with basic linguistic terminology do not kow how languanges work, including their mother tongue, or do not reflect on the differences and similarities between their L1 and L2. This can make learning German more challenging, especially in a university setting where language instruction is often quite explicit. This paper examines students’ perceptions of linguistic instruction and its impact on their language skills, German proficiency, and linguistic reflection. In order to assess these aspects, three groups of students, who attended linguistic modules with different content, completed a feedback questionnaire after their respective courses. The results indicate that most students, regardless of course content differences, viewed metalinguistic instruction positively, finding it beneficial for enhancing their language skills, learning German more effectively, and encouraging language reflection.

1 Introduction

Based on the experience as a lecturer in German as a foreign language, it is possible to assert that many students lack familiarity with basic linguistic terminology and struggle to analyse language structures critically. In many UK and Irish universities, for instance, this lack of (meta)linguistic education stems partly from the fact that German linguistics is not a core component of German degree programmes due to a strong focus on German literature, while at Italian universities linguistic courses are sometimes taught by literary scholars and reduced to pure translation courses.

While the relevance of the discipline of linguistics to modern language teaching has always been controversial, and many teachers and linguists (including Chomsky 1966 [1971]) approach the subject with scepticism (Widdowson 2020), empirical research has shown to varying degrees that explicit (mainly grammatical) knowledge correlates positively and sometimes significantly with learners’ language proficiency (e.g., Abu Radwan 2005; Alderson et al. 1997; Elder et al. 1999; Elder and Manwaring 2004; Roehr 2008b). Moreover, language reflexive processes, i.e. the speakers’ ability to distance themselves from their own social role, the speaker’s intention, the speech situation etc. (Ivo 1975: 47), have a positive effect on language acquisition (Budde 2012: 41). Thus, there is evidence of a link between learners’ language reflection, the use of metalinguistic knowledge and successful performance in the target language (Leow 1997; Nagata and Swisher 1995; Rosa and O’Neill 1999). Foreign language teaching is usually not completely unstructured and a higher degree of compatibility with linguistic knowledge usually leads to better learning outcomes (Lechner 2009: 107). This is particularly true for university students, as teaching time is very limited and explicit grammar teaching is still part of many courses (Roehr 2008b: 173). The university context also means that some students are studying German to become teachers, and for them it is particularly important to have language skills (e.g., Thurmair 2001; Cunningham 2015).

Therefore, in order to promote the teaching of linguistic content at university level and to gain insight into learners’ perceptions, three modules with different content were designed for German students at different language levels at two Italian universities. At the end of each course, students were given a questionnaire to assess their perception of the course content and the perceived impact on their language skills, acquisition and reflection.

2 (Meta)linguistic knowledge and modern foreign language learning

Metalinguistic knowledge is “an individual’s explicit knowledge about language” (Roehr 2008a: 70) and refers to learners’ ability to correct, describe and explain errors in a foreign language (cf. Green and Hecht 1992; Renou 2000). The role of metalinguistic knowledge and its impact on language learning and proficiency has been extensively debated in research (cf. Hu 2002, 2011; Serrano 2011), with conflicting results.

The positions range from the non-interface position via the weak interface position to the strong interface position (see Table 1 for a concise overview). The first position holds that implicit unconscious and explicit conscious metalinguistic knowledge involve different acquisition mechanisms (Hulstijn 2002; Krashen 1981, 1986), are stored in different parts of the brain (Paradis 1994), and therefore explicit knowledge cannot be transformed into implicit knowledge (Ellis 2005) but merely serves as a monitor for production (e.g., Krashen 1986, 2003; Paradis 1994). In contrast, the strong interface position assumes that explicit knowledge can not only be derived from implicit knowledge but can also be transformed into implicit knowledge through practice (cf. Sharwood Smith 1981; DeKeyser 1998). The weak interface position can be positioned between the two extremes and sees the possibility of explicit knowledge becoming implicit, but with some restrictions on when or how this can happen (Ellis 2005: 144).

Key ideas of theoretical positions regarding metalinguistic knowledge and its impact on language learning and proficiency.

| Theoretical position | Key idea | Scholars |

|---|---|---|

| Non-interface | Explicit and implicit knowledge are stored separately, meaning that explicit knowledge cannot be transformed into implicit knowledge. | Krashen (1981), Paradis (1994), Hulstijn (2002) |

| Weak interface | Explicit knowledge can influence implicit knowledge under certain conditions. | Ellis (2005) |

| Strong interface | Explicit knowledge can become implicit through practice. | DeKeyser (1998), Sharwood Smith (1981) |

Similar to these different positions, the empirical evidence is also contradictory. While grammatical knowledge has been shown to be beneficial in predicting learner outcomes such as reading, writing and speaking (Brecht et al. 1995; Golonka 2006), some correlation studies have found only a weak relationship between metalinguistic knowledge and language proficiency (Alderson et al. 1997; Elder et al. 1999), while others show a moderate to strong correlation (e.g. Alipour 2014; Elder and Manwaring 2004; Macrory and Stone 2000; Roehr 2008b). Some of the variation in findings can be explained by the fact that different studies have examined different skills and that the relative usefulness of metalinguistic knowledge depends on learner-internal and learner-external variables, “including task modalities, the learner’s level of L2 proficiency, language learning experience, cognitive abilities, and stylistic orientation” (Roehr 2008a: 84).

Despite the mixed results, many researchers agree that explicit grammatical explanations can positively accelerate and optimise the learning process (Ellis 2005), as they can support the trial-and-error process of hypothesising, testing and revising, and enable learners to form correct hypotheses and counteract the formation of false ones (cf. Storch 1999). Indeed, knowledge of metalinguistic rules often serves as a trigger for hypothesis formation (Thurmair 2001). Therefore, “instructed learners progress faster, they are likely to develop more elaborate language repertoires, and they typically become more accurate than uninstructed learners” (Ortega 2009: 139). This is particularly true for morpho-syntactically rich languages such as German (Thurmair 2001). Explicit grammatical knowledge and the resulting familiarity with basic terminology can also serve as a basic toolbox for lifelong language learning (Fandrych 2000), enabling learners to correct errors themselves and facilitating autonomous and independent (further) learning (Thurmair 2001).

However, explicit metalinguistic knowledge in the discourse of language teaching and learning refers predominantly to aspects of grammar and is often tested by asking learners to verbalise specific grammatical rules (Ellis 2005).

However, explicit language knowledge is much more than just grammar, and the question of whether and to what extent learners benefit from metalinguistic knowledge beyond grammar, and whether there is a relationship between linguistics and its application in didactics, has not been systematically explored in neither linguistics nor didactics (Lechner 2009). While it has been postulated that successful L2 teaching requires collaboration between linguistics and didactics (Lechner 2009), there is a lack of data, also when it comes to the learners’ perspective. Therefore, this paper aims to address this research gap by shedding light on whether and how learners perceive that linguistic knowledge affects their language learning and reflection process.

3 Student perception of linguistic knowledge and its impact on learning German

In order to assess how German students perceive being taught different (meta)linguistic content and its impact on their language skills, three courses were designed for different cohorts. Since the cohorts were rather small, the findings should be interpreted with caution, as small sample sizes can affect the validity of the data. Future studies with larger sample groups could provide more robust insights (see Section 3.4).

The content of the three courses ranged from an introduction to theoretical linguistics to aspects of applied linguistics. The aim of the study was therefore not only to assess whether students find linguistic knowledge helpful for their language skills, acquisition and reflection, but also whether all contents are perceived as equally useful.

3.1 Course structures and contents

Students from three different linguistics courses at two different universities participated in the study. The modules differed not only in terms of content taught, but also regarding student numbers and the students’ language level (Table 2). In addition to the respective linguistics modules, all students had 5–6 h of German language class per week as well as a German literature module.

Course structure and contents of the respective courses at the University of Urbino and Macerata.

| Courses | Lingua tedesca II | Lingua e traduzione tedesca I | Lingua e traduzione tedesca II |

|---|---|---|---|

| University | Università degli Studi di Urbino Carlo Bo | Università degli Studi di Macerata | Università degli Studi di Macerata |

| Academic year | 2023/2024 | 2023/2024 | 2023/2024 |

| Number of students (attending) | 20–25 | 15–20 | 6 |

| Year | 2nd year | 1st year | 2nd year |

| Language level | From B1–C1 | A1–A2 | B1 |

| Attending students | German language students only | Open to students from all faculties | German language students only |

| Content | Neologisms | Introduction into (theoretical) linguistics | Introduction into different fields of applied linguistics |

| Exam | Mini research project and critical research review or oral exam | Tutorial video or oral exam | Tutorial video or oral exam |

| Teaching time | 30 h (5 h per week) | 45 h (3 h per week) | 45 h (3 h per week) |

The course Lingua Tedesca II at the Università degli Studi di Urbino Carlo Bo in Italy is aimed at second-year students of Modern Foreign Languages who are studying German and another foreign language. As students in Urbino can choose to start their studies at different language levels depending on their previous knowledge of German, the levels of the students in the Lingua Tedesca II course ranged from B1 toC1. The course was regularly attended by 20–25 students. As there is no obligation to attend, the number of students varies. The total teaching time for the course is 30 h over the period of one academic term.

The course focused on neologisms, combining a theoretical introduction with a practical mini-research project. During the first 15 h, the students were given an introduction to neologisms, followed by a module on morphology, lexicography and psycholinguistics, always in relation to neologisms. Most of the teaching was in Italian, but all the slides were bilingual and authentic German material, such as videos, was used. During the second part, the students worked in small groups to research the frequency and co-occurrence of ten selected Covid-related neologisms. Each group had to choose five Covid-related German neologisms that had been added to the online Duden – the German reference dictionary – and five that had not been added (yet). As sources the students used a word glossary from the DWDS[1] and the Covid neologism dictionary from the Leibniz-Institut für deutsche Sprache (Institute German Language).[2] The students’ task was to find out (a) whether more established words – i.e. words that have entered the online Duden – exhibit a higher frequency than less established words from 2020 to 2024, and (b) what the context of use can tell us about the meaning of the new word. To obtain these data, they conducted a corpus analysis using the online application COSMAS II of the German Reference Corpus (DeReKo) (Leibniz-Institut für deutsche Sprache 2024). Each group of students then had to present their data and write a critical review of another group’s data. Students who did not participate in the project had to take an oral exam on the various topics covered in the course.

The other two courses (Lingua e Traduzione Tedesca I and Lingua e Traduzione Tedesca II) were both taught at the Università degli Studi di Macerata in Italy and were aimed at first- and second-year students respectively (cf. Table 2). Both courses consisted of 45 teaching hours and the examination modality allowed students to either create a more in-depth explanatory video tutorial on a linguistic aspect covered in class or to take an oral exam. Both courses were mainly taught in Italian, but all slides were bilingual, German examples were used and, especially in the second-year course, some authentic materials such as newspaper articles and videos were integrated into the course.

The first-year course is open to students from all Faculties, so the 15–20 students who regularly attended the course were not all language students. Their language level varied from complete beginners to students with previous experience in German. The course served as an introduction to the main disciplines of theoretical linguistics, including phonology and phonetics, morphology, syntax, semantics and pragmatics. While the course was mainly theoretical, it also included many practical and interactive exercises to apply the theory. Further, the course also incorporated many contrastive elements, especially between German, Italian and English.

The second-year course is exclusively for language students. Only six students at B1 level regularly attended the course. After reviewing some basic linguistic terminology in the first few lessons, the course aimed to broaden the students’ linguistic knowledge by covering various aspects of German sociolinguistics, lexicology and lexicography, psycholinguistics, corpus linguistics, and gender-inclusive German. In addition to theory, the course offered students exercises to apply their newly acquired knowledge, such as translating various non-standard varieties of German into standard German or working with corpora.

Therefore, the content of the three courses covered different aspects of linguistics and was designed not only to provide a better understanding of theoretical aspects of the German language, but also to give an insight into current trends, changes, and language use.

3.2 Outline of questionnaire

The students completed a questionnaire, which was created by using Google Forms,[3] during the very last class of the course. The link to the questionnaire was posted on the moodle/teams page used for the courses and students who were not in class that day were encouraged by email to participate and fill in the questionnaire. Each questionnaire was tailored to the course content, with minor modifications ensuring relevance.

In all three questionnaires, participants, upon accessing the survey, were presented with a short introductory text, followed by routine demographic questions, including questions about the participants’ mother tongue and their degree programme. This was followed by the main body of questions, which included both open and closed questions. The closed question responses were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) to quantify student perceptions. During the data evaluation, students’ responses on the Likert scale were coded as follows: 5 and 4 indicate agreement, 3 is neutral, and 2 and 1 indicate disagreement.

The questionnaire for the students in Urbino was divided into two parts, with questions about the theoretical part of the course, followed by questions about the practical part of the course. Students were asked in closed questions whether the theoretical and practical parts were helpful for improving their language skills. In addition to these closed questions, the students were asked in open questions about how the theoretical and practical parts helped or did not help them to improve their language skills. It should be noted that the intention of the questionnaires was not to measure the students’ actual language improvement but their perceived improvement. Consequently, the questionnaires did not contain any items that specifically tested their practical German skills.

As the modules were also designed to encourage reflection on language, all three questionnaires included an open and closed question on whether the course had encouraged students to reflect on language. It should be noted that the questionnaires also contained additional questions that are not relevant to this study and will therefore not be elaborated on but were intended to provide the lecturer with feedback on other aspects of the course.

The two questionnaires for the courses in Macerata consisted of one part only, as the courses were not split in two parts. The closed questions asked whether the metalinguistic knowledge acquired in the course helped the students to improve their language skills and to learn German more effectively, and whether they thought it was generally good and useful to have some theoretical language knowledge in order to learn a foreign language. The last two questions were unfortunately not included in the questionnaire in Urbino since the course in Urbino was the first to finish and the design of the questionnaire was revised, and more questions were added for the courses in Macerata.

The open questions were follow-up questions to the closed Likert-scale questions, asking participants to what extent the theoretical knowledge did or did not help to improve/expand their language skills, and to what extent the theoretical knowledge acquired during the course did or did not help them to learn German more effectively. They were also asked which part of the course they found particularly interesting/not so interesting, which part was useful/not useful for learning German.

The first-year students (Lingua e Traduzione Tedesca I) were further asked whether the theoretical knowledge acquired in the course helped them with their German pronunciation. The second-year students (Lingua e Traduzione Tedesca II) were asked whether the knowledge acquired during the course would help them to better find their way around in German-speaking countries and if so in what way.

3.3 Results

A total of 15 students took part in the questionnaire for the course Lingua Tedesca II in Urbino, 4 male, 10 female and one person who did not specify their gender. Their ages ranged from 19 to 31 years and all students were native speakers of Italian, with two students being bilingual with Italian and French and Italian and Romanian. All 15 students were studying German as part of their foreign language degree.

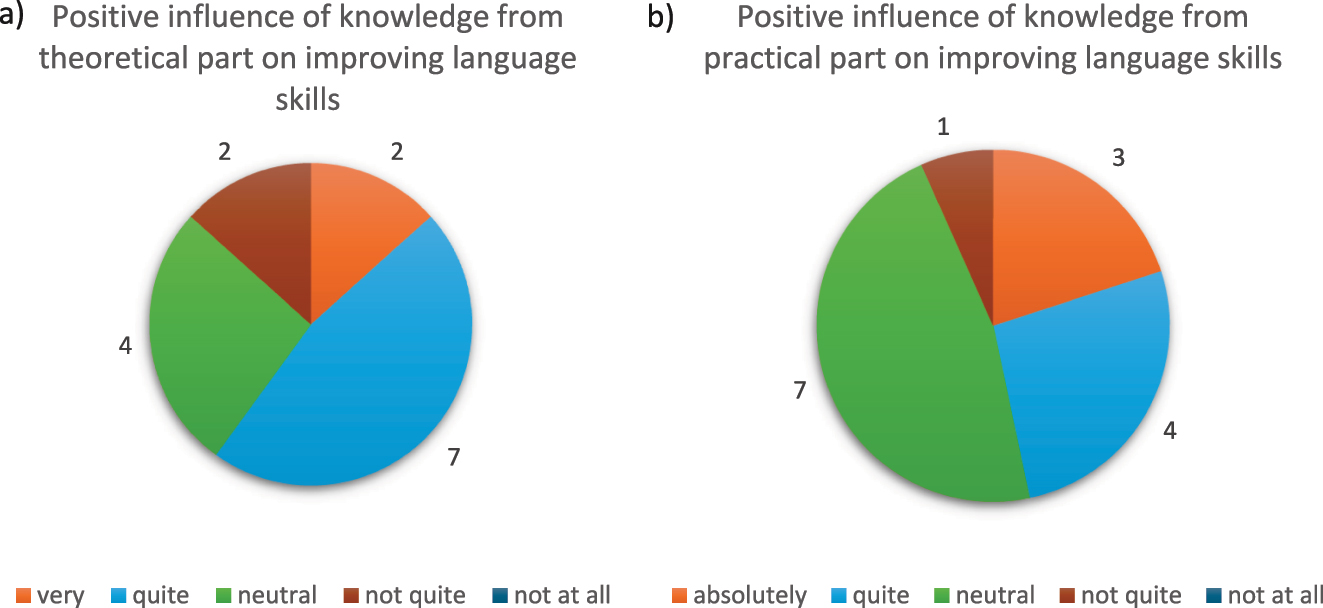

The majority of students (9 out of 15) agreed that the theoretical part of the course helped them to improve their language skills. Four students neither agreed nor disagreed, two students did not feel that the theoretical content helped them to improve their German (cf. Graph 1a).

a and b Feedback from students taking the course Lingua Tedesca II at the University of Urbino regarding the positive influence of knowledge from the theoretical (a) and practical (b) course part on improving their German language skills.

The practical part was perceived to be a bit less helpful in improving the students’ language skills. Seven out of 15 students agreed that it helped them improve their German, while seven neither agreed nor disagreed and one student disagreed (Graph 1b). When asked to elaborate on how each part helped them improve their German, for both parts the students mainly referred to the fact that they learned new words (responses 1–3) and got a better understanding of word formation in German (response 4). For the practical part, some students also felt that the course enabled them to work with ‘real’ German (response 5).

I have learnt new words both in theory and group work.

It helped me with the meaning and context of many words.

It helped me because we saw how and how often words are used, the various meanings and related meanings, and words that belong or do not belong to today’s language.

It helped me because I learned about what neologisms are about and how a word is formed and structured.

It brought me closer to the real spoken language than the German studied in class.

However, as shown in Graph 1a and b, not all students found the course beneficial to their language skills and the fact that the course was mainly taught in Italian was criticised (response 6).

Certainly, my theoretical and practical skills have improved because we have done work as linguists, but I do not feel that my language skills have improved because I have not applied the German language as much as the Italian language.

Interestingly, while some students provided critical responses on the Likert scale, their open-ended feedback was overwhelmingly positive. This suggests that numerical ratings alone may not fully capture student perspectives.

Almost all students (14 out of 15) stated that the course had encouraged them to think about the German language, especially since topics were discussed that are often not covered in language classes (responses 7–8) and the course stimulated reflection (response 9).

We analysed more practical aspects of the language and focused on topics that are often not covered in normal grammar lessons.

The idea of learning the contemporary language, and not the classical one, is more stimulating and helps to reflect on language today.

I reflected on the meaning of words in relation to the context in which they are used. i discovered that for many words there can be more than one meaning, which must be interpreted according to the context.

In total, 16 students from the Lingua e Traduzione Tedesca I course in Macerata completed the questionnaire, eleven females and five males. All were native speakers of Italian, 14 were students of German, one was a politics, and one was a cultural studies student. The age of the participants ranged from 19 to 29 years.

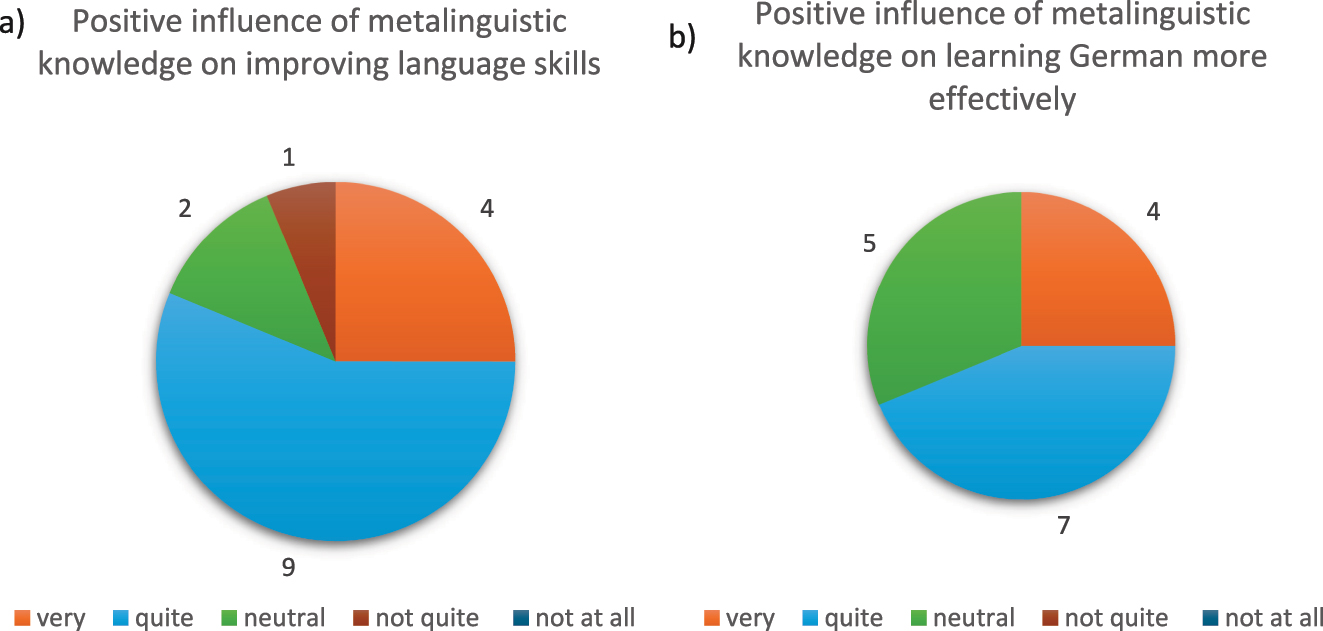

The majority of the students (13 out of 16) agreed that the metalinguistic knowledge acquired during the course helped them to improve their language skills (cf. Graph 2a). Two students neither agreed nor disagreed and one student disagreed. 11 out of 16 students also agreed that the metalinguistic knowledge had a positive impact on their ability to learn German more effectively (Graph 2b), five students neither agreed nor disagreed.

a and b Feedback from students taking the course Lingua e Traduzione Tedesca I at the University of Macerata regarding the positive influence of metalinguistic knowledge on improving their language skills (a) and learning German more effectively (b).

In the open-ended responses about the relationship between metalinguistic knowledge and language skills, it was pointed out that the theoretical basis is also useful for other languages (response 10), that it makes learning a new language easier (response 11) and that it creates an understanding of rules (response 12).

The theoretical knowledge has also helped me in all the other languages I study.

They made learning a new language more accessible.

To better understand the language from the perspective of rules.

In terms of learning German more effectively, students found the course particularly helpful in understanding syntactic and phonological features of the German language (responses 13–15).

It helped me understand sentence construction and the various phonetic rules that characterise German.

I understood how to formulate sentences better and how to pronounce words best.

They have helped me learn German more effectively because they allow me to understand the meaning of a sentence even if I do not know all the words in it, identifying in constituents.

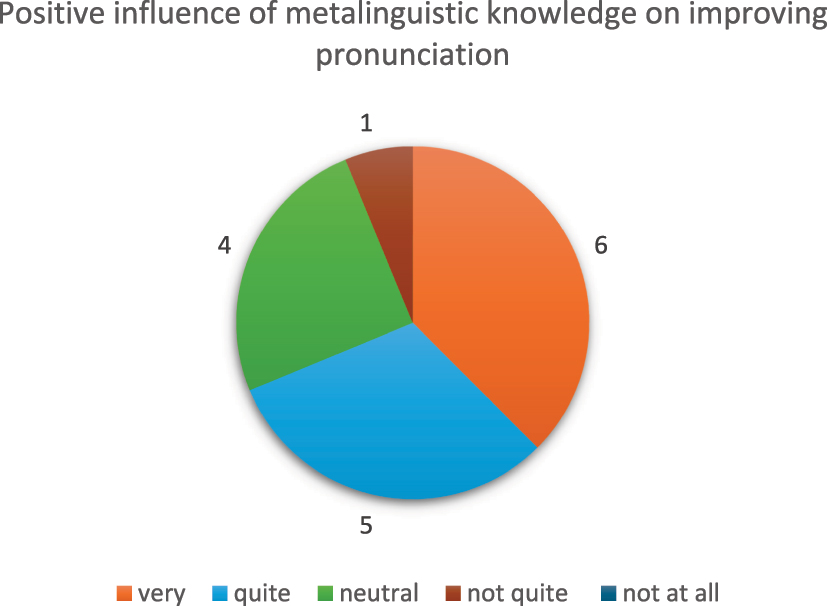

Students’ responses 13–15 already indicate the usefulness of phonetics and phonology. Similarly, the majority of students agreed that metalinguistic knowledge of phonetics and phonology helped them to improve their pronunciation (11 out of 16). Four students neither agreed nor disagreed and one student disagreed, as shown in Graph 3.

Feedback from students taking the course Lingua e Traduzione Tedesca I at the University of Macerata regarding the positive influence of metalinguistic knowledge on improving their German pronunciation.

All 16 students agreed that it was helpful and useful to have theoretical language knowledge in order to learn a foreign language. Furthermore, they were all encouraged to reflect on the language during the course as it made them aware of concepts and ideas they had not been exposed to before (responses 16–17). The two topics found most interesting were syntax (by six out of 16 students) and semantics (by four out of 16 students). The topics considered most useful were phonology and syntax (by five students each).

It encouraged me to reflect because of the topics covered which open our eyes to the structure, use and teaching of a language. Because they enable us to understand the reasons why we position, pronounce or not pronounce words in a certain way.

It made me think about many aspects of language that I had never thought about before.

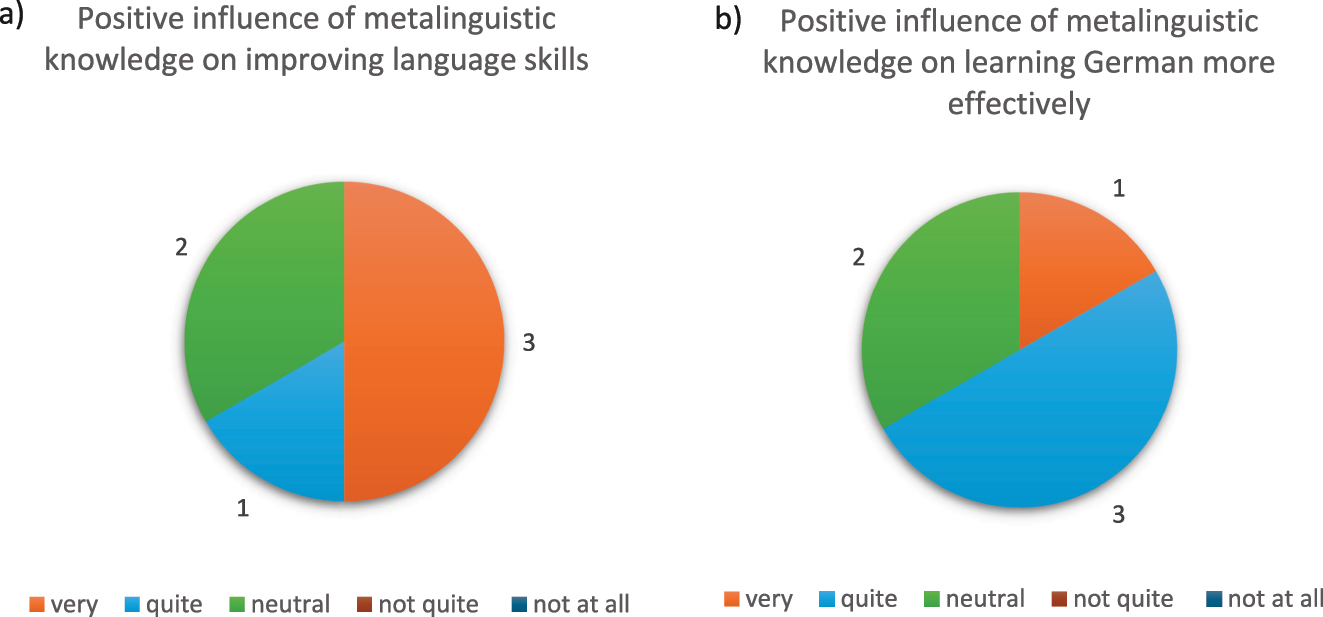

Only six students attended Lingua e Traduzione Tedesca II in Macerata. All of them filled in the questionnaire, five female and one male. Five of them were Italian native speakers, one Russian. They were all students of German and aged between 20 and 25.

The majority of students (four out of six) agreed that the metalinguistic knowledge acquired during the course helped them to improve their language skills (cf. Graph 4a). Two students neither agreed nor disagreed. Four out of six students also agreed that the metalinguistic knowledge can help them to learn German more effectively (Graph 4b).

a and b Feedback from students taking the course Lingua e Traduzione Tedesca II at the University of Macerata regarding the positive influence of metalinguistic knowledge on improving their language skills (a) and learning German more effectively (b).

Students explained that the metalinguistic knowledge acquired had a positive impact on their language skills, as the course provided them with tools (response 18) and broadened their linguistic horizons (responses 19–20).

The theoretical knowledge helped me to broaden my language skills as it provided me with tools to navigate the language system with more awareness

The theoretical knowledge helped me to broaden my horizons on German linguistics and its forms

I have definitely improved my pronunciation and better understood the workings of the language

When it comes to learning German more effectively, students found knowledge about varieties (response 21) and an increased awareness (responses 22–23) helpful.

I can understand dialectal differences and how to apply a more inclusive language.

It certainly helped me to have a greater awareness of the German language and its use.

It helped me to pay attention to certain things in writing words (being more gender inclusive, for example).

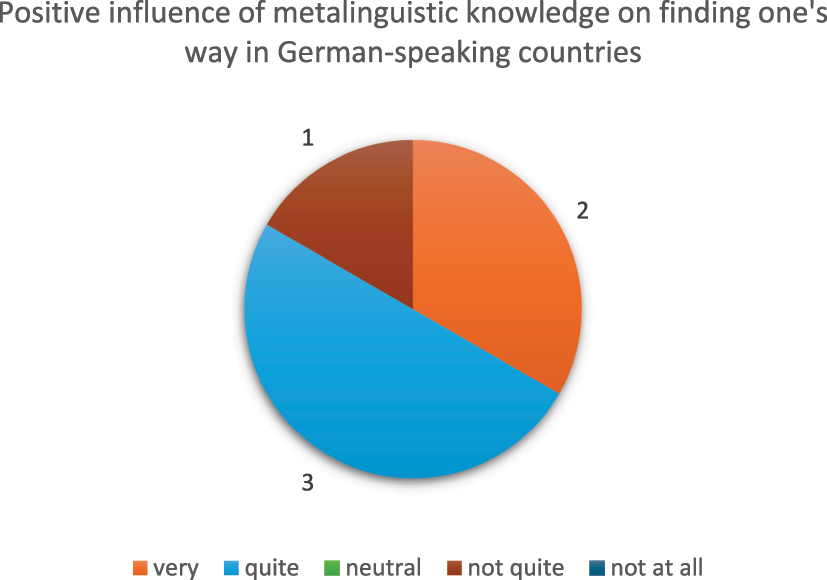

Most students (five out of six) agreed that the metalinguistic knowledge helped them to better find their way around in German-speaking countries (Graph 5). The increased understanding of German variations such as dialects was seen as particularly helpful (responses 24–25). However, it was also stated that the knowledge acquired was too theoretical to be applied in a more practical context (response 26).

It helped me to distinguish dialect variations.

For example, the recognition of certain dialects.

Being very theoretical knowledge, I do not believe that this can be applied to the practicality of the language in the spoken word in a German-speaking country.

Feedback from students taking the course Lingua e Traduzione Tedesca II at the University of Macerata regarding the positive influence of metalinguistic knowledge on finding their way around German-speaking countries.

Similarly to the first-year students, all second-year students agreed that it was helpful and useful to have theoretical language knowledge in order to learn a foreign language and all were encouraged to think about language because of new topics discussed in class (responses 27–28). The students regarded sociolinguistics (by four out of six students) as the most interesting topic but gender-inclusive German as the most useful one (by four out of six students).

The course encouraged me to reflect on language as it confronted me with areas that I had not analysed before and, consequently, gave me the opportunity to ask myself questions about language that I had not had the opportunity to reflect on before.

Through the debates that were created in class. That was the most formative part of the course: the exchange and interaction with the opinions of others and of the teacher.

3.4 Discussion

The study has shown that, regardless of course content, the majority of students in all three groups found learning about different areas of linguistics helpful in improving their language skills and learning German more effectively. While these findings strongly support the idea of integrating more linguistics into German degree programmes, some of the study’s limitations need to be addressed in the future. Despite the fact that students from three different cohorts agreed on the positive impact of the course content on their language skills and reflection, the groups of students were relatively small and therefore larger groups would be needed in order to make more generalised assumptions. This is particularly true for the second-year course in Macerata with only six students. The small number of students could also have an impact on the results of the questionnaire, since although the study was completely anonymous, students in such a small group might fear that their results could be traced back to them.

Furthermore, it would be useful to apply a mixed-method approach and supplement questionnaires with interviews or classroom observations. This could be particularly valuable, as the results reveal a discrepancy between responses on the Likert scale and the open questions (cf. Section 3.3), with responses to the closed questions sometimes being more critical than the ones to the open questions. However, this implies that the questionnaires are no longer anonymous and, given that the courses are graded, could influence students’ responses.

The purpose of the study was not to measure the impact of linguistic knowledge on language proficiency, but to shed light on the learners’ perspective. Therefore, the study cannot make any assumptions about the actual improvement of the learners’ German, which should be the subject of future studies. However, the fact that the learners found the content useful and helpful, and that they felt they could understand and thus learn the language more effectively, could increase their confidence. A learner’s confidence “corresponds to a general belief in being able to communicate […] in an adaptive and efficient manner” (MacIntyre et al. 1998: 551). Language confidence is not only a key element in determining communicative competence (Clément 1980, 1986; Clément and Kruidenier 1985), but also “the best predictor of language proficiency” (Clément 1986: 286).

The first-year students found that learning more about phonology and syntax was helpful. In fact, when it comes to phonetics and phonology, learners often have to learn to hear certain relevant discriminative criteria first, so it is necessary to make them aware and conscious of them (Thurmair 2001), so that they can then understand as well as produce the sounds correctly. Especially when it comes to sounds that do not exist in the mother tongue or do not indicate a difference in meaning, there are certain limitations of the learning apparatus (Lechner 2009). Given that the skills needed to learn fine motor tasks such as phonetic articulation decline with age (Lechner 2009), awareness of differences or similarities is even more important for adult learners.

While sociolinguistics is a field that seems to have had little influence on foreign language teaching (Schmid 2007), the second-year students in Macerata found it very helpful to acquire metalinguistic knowledge about regional and social variations as it helps them to find their way around German-speaking countries. The second-year students in Urbino liked working as linguists as corpus linguistics offers the opportunity to confront students with authentic, real examples actually produced by native speakers (Widdowson 2020), and they appreciated working with what they described as ‘real’ German spoken outside the classroom. These results align with Ellis (2005) and Hulstijn (2002), who found that explicit linguistic instruction positively influences learners’ analytical skills in language learning.

All three course modules succeeded in stimulating language reflection. Indeed, language reflection enhances learners’ linguistic competence, deepens understanding of language variation, and fosters responsible language use (Ossner 2006) and therefore has a favourable effect on the acquisition of a foreign language (Budde 2012). The fact that learners in Macerata did not classify the same content areas as useful and interesting shows that, by the end of the course, they were able to differentiate between linguistic topics that are helpful for them to improve their language skills and topics that they like because of the content. To integrate these findings into practice, educators might consider incorporating short metalinguistic reflection tasks within traditional grammar instruction to reinforce theoretical concepts with practical application.

While the overall feedback was positive, the students also brought forward some criticism. The fact that the second-year courses were mainly taught in Italian did not enable all students to improve their German skills. Unfortunately, the institutional framework does not allow these courses to be taught in German. Furthermore, some students found the knowledge acquired too theoretical, which could be due to the fact that students benefit differently from various approaches and thus (meta)linguistic knowledge is not equally useful for different learners.

Nevertheless, the feedback shows that the courses have been beneficial for the majority of students and have succeeded in making them more aware of different linguistic aspects and providing them with tools to better navigate the language system.

4 Conclusions

The aim of this study was to address the research gap regarding the benefit of linguistic knowledge on language learning and reflection. While many previous studies have indicated, to varying degrees, a correlation between explicit grammar knowledge and language proficiency, linguistic disciplines that go beyond grammatical explanations have been neglected. The results of the questionnaire study have shown that students across courses and contents appreciate learning about linguistic content and find it helpful to improve their language skills and learn German more effectively.

However, the actual improvement of the students was not measured. Nevertheless, the linguistic understanding can foster the students’ confidence and thus create a certain “placebo” effect in language learning – implying that if they feel that the knowledge helps them learn German better, it will indeed be useful for them. These findings support integrating linguistics into German degree programmes through structured modules on theoretical and applied linguistics. While it would be desirable to have German linguistics becoming a core element across German degree programmes, the available resources might not always allow this. However, we strongly believe that the integration of short but intensive structured modules about linguistic disciplines such as phonology, syntax, or sociolinguistics, can be a step into the right direction and enhance students’ metalinguistic awareness and language proficiency.

References

Alderson, J. Charles., Caroline Clapham & David Steel. 1997. Metalinguistic knowledge, language aptitude and language proficiency. Language Teaching Research 1. 93–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/136216889700100202.Search in Google Scholar

Alipour, Sepideh. 2014. Metalinguistic and linguistic knowledge in foreign language learners. Theory and Practice in Language Study 4(12). 2640–2645. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.4.12.2640-2645.Search in Google Scholar

Abu Radwan, Adel. 2005. The effectiveness of explicit attention to form in language learning. System 33. 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2004.06.007.Search in Google Scholar

Brecht, Richard, Dan Davidson & Ralph Ginsberg. 1995. Predictors of foreign language gain during study abroad. In Barbara Freed (ed.), Second language acquisition in a study abroad context, 38–65. Philadelphia: PA: John Benjamins.10.1075/sibil.9.05breSearch in Google Scholar

Budde, Monika. 2012. Über Sprache reflektieren. Unterricht in sprachheterogenen Lerngruppen. Kassel: University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noah. 1966. Linguistic theory. In Robert G. Mead (ed.), Language teaching: Broader contexts. Northeast conference on the teaching of modern languages: reports of the working committees. New York: MLA Materials Center. Reprinted 1971 in J.P.B. Allen & Paul van Buren (eds.), Chomsky: Selected readings, 152–159. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Clément, Richard. 1980. Ethnicity, contact and communicative competence in a second language. In Howard Giles, W. Peter Robinson & Philip M. Smith (eds.), Language: Social psychological perspectives, 147–154. Oxford: Pergamon.10.1016/B978-0-08-024696-3.50027-2Search in Google Scholar

Clément, Richard. 1986. Second language proficiency and acculturation: An investigation of the effect of language status and individual characteristics. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 5. 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x8600500403.Search in Google Scholar

Clément, Richard & Bastian Kruidenier. 1985. Aptitude, attitude and motivation in second language proficiency: A test of Clément’s model. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 4. 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x8500400102.Search in Google Scholar

Cunningham, Una. 2015. Language teachers’ need for linguistics. Te Reo (58). 77–94.Search in Google Scholar

DeKeyser, Robert. 1998. Beyond focus on form: Cognitive perspectives on learning and practicing second language grammar. In Catherine Doughty & Jessica Williams (eds.), Focus on form in second language acquisition, 42–63. New York: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Elder, Cathie & Diane Manwaring. 2004. The relationship between metalinguistic knowledge and learning outcomes among undergraduate students of Chinese. Language Awareness 13(3). 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410408667092.Search in Google Scholar

Elder, Cathie, Jane Warren, John Hajek, Diane Manwaring & Alan Davies. 1999. Metalinguistic knowledge: How important is it in studying a language at university? Australian Review of Applied Linguistics 22(1). 81–95.10.1075/aral.22.1.04eldSearch in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. 2005. At the interface: Dynamic interactions of explicit and implicit language knowledge. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 27(2). 305–352. https://doi.org/10.1017/s027226310505014x.Search in Google Scholar

Fandrych, Christian. 2000. Ist der Kommunikative Ansatz im Fremdsprachenunterricht an seine Grenzen gekommen? German Studies at Aston 1. 2–12.Search in Google Scholar

Golonka, Ewan. 2006. Predictors revised: Linguistic knowledge and metalinguistic awareness in second language gain in Russian. The Modern Language Journal 90(iv). 496–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00428.x.Search in Google Scholar

Green, Peter & Karlheinz Hecht. 1992. Implicit and explicit grammar: An empirical study. Applied Linguistics 13. 168–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/13.2.168.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, Guangwei. 2002. Metalinguistic knowledge at work: The case of written production by Chinese learners of English. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching 12. 5–44.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, Guangwei. 2011. Metalinguistic knowledge, metalanguage, and their relationship in L2 learners. System 39. 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.01.011.Search in Google Scholar

Hulstijn, Jan H. 2002. Towards a unified account of the representation, processing and acquisition of second language knowledge. Second Language Research 18. 193–223. https://doi.org/10.1191/0267658302sr207oa.Search in Google Scholar

Ivo, Hubert. 1975. Handlungsfeld Deutschunterricht: Argumente und Fragen einer praxisorientierten Wissenschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer.Search in Google Scholar

Krashen, Stephen. 1981. Second language acquisition and second language learning. London: Pergamon.Search in Google Scholar

Krashen, Stephen. 1986. Principles and Practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon.Search in Google Scholar

Krashen, Stephen. 2003. Explorations in language use. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.Search in Google Scholar

Lechner, Winfried. 2009. Linguistische Theorie im Unterricht. Schnittstellen von Linguistik und Sprachdidaktik in der Auslandsgermanistik. Tagungsband zur Tagung am 09-10 April 2009. Athens: Universität Athen.Search in Google Scholar

Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache. 2024. Deutsches Referenzkorpus/Archiv der Korpora geschriebener Gegenwartssprache 2024-I-RC3 (RC vom 13.03.2024). Mannheim: Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache. Available at: www.ids-mannheim.de/dereko.Search in Google Scholar

Leow, Ronald P. 1997. Attention, awareness, and foreign language behavior. Language Learning 47. 467–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00017.Search in Google Scholar

MacIntyre, Peter D., Richard Clément, Zoltan Dörnyei & Kimberley A. Noels. 1998. Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in an L2: A situated model of confidence and affiliation. Modern Language Journal 82. 545–562.10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.xSearch in Google Scholar

Macrory, Gee & Valerie Stone. 2000. Pupil progress in the acquisition of the perfect tense in French: The relationship between knowledge and use. Language Teaching Research 4. 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1191/136216800669518189.Search in Google Scholar

Nagata, Noriko & M. Virginia Swisher. 1995. A study of consciousness-raising by computer: The effect of metalinguistic feedback on second language learning. Foreign Language Annals 28(3). 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1995.tb00803.x.Search in Google Scholar

Ortega, Lourdes. 2009. Understanding second language acquisition. London: Hodder Education.Search in Google Scholar

Ossner, Jakob. 2006. Sprachdidaktik Deutsch. Eine Einführung. Paderborn, München: Schöningh.10.36198/9783838528076Search in Google Scholar

Paradis, Michel. 1994. Neurolinguistic aspects of implicit and explicit memory: Implications for bilingualism and SLA. In Nick C. Ellis (ed.), Implicit and explicit learning of languages, 393–419. San Diego: Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Renou, Janet M. 2000. Learner accuracy and learner performance: The quest for a link. Foreign Language Annals 33(2). 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2000.tb00909.x.Search in Google Scholar

Roehr, Karen. 2008b. Metalinguistic knowledge and language ability in university-level L2 learners. Applied Linguistics 29(2). 173–199. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm037.Search in Google Scholar

Roehr, Karen. 2008a. Linguistic and metalinguistic categories in second language learning. Cognitive Linguistic 19(1). 67–106. https://doi.org/10.1515/COG.2008.005.Search in Google Scholar

Rosa, Elena & Michael D. O’Neill. 1999. Explicitness, intake, and the issue of awareness. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 21. 511–556. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263199004015.Search in Google Scholar

Schmid, Stephan. 2007. Spannungsfeld zwischen Linguistik, Didaktik und Politik: Streiflichter zur Entwicklung des Fremdsprachenunterrichts. Beiträge zur Lehrerbildung 25(2). 223–230. https://doi.org/10.36950/bzl.25.2.2007.9922.Search in Google Scholar

Serrano, Raquel. 2011. From metalinguistic instruction to metalinguistic knowledge, and from metalinguistic knowledge to performance in error correction and oral production tasks. Language Awareness 20(1). 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2010.529911.Search in Google Scholar

Sharwood Smith, Michael. 1981. Consciousness-raising and the second language learner. Applied Linguistics 2. 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/2.2.159.Search in Google Scholar

Storch, Günther. 1999. Deutsch als Fremdsprache – Eine Didaktik. München: UTB.Search in Google Scholar

Thurmair, Maria. 2001. Die Rolle der Linguistik im Studium Deutsch als Fremdsprache. German as a Foreign Language 2. 41–59.Search in Google Scholar

Widowson, Henry. 2020. Linguistics, language teaching objectives and the language learning process. Pedagogical Linguistics 1(1). 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1075/pl.19014.wid.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Integration, collaboration, friendship as core messages for younger generations

- Research Articles

- Research practice and culture in European universities’ Language Centres. Results of a survey in CercleS member institutions

- Language practices in the work communities of Finnish Language Centres

- Fostering transparency: a critical introduction of generative AI in students’ assignments

- Expert versus novice academic writing: a Multi-Dimensional analysis of professional and learner texts in different disciplines

- Raising language awareness to foster self-efficacy in pre-professional writers of English as a Foreign Language: a case study of Czech students of Electrical Engineering and Informatics

- Does an autonomising scheme contribute to changing university students’ representations of language learning?

- Investigating the relationship between self-regulated learning and language proficiency among EFL students in Vietnam

- Students’ perspectives on Facebook and Instagram ELT opportunities: a comparative study

- Designing a scenario-based learning framework for a university-level Arabic language course

- Washback effects of the Portuguese CAPLE exams from Chinese university students and teachers’ perspectives: a mixed-methods study

- Students’ perception of the impact of (meta)linguistic knowledge on learning German

- Language policy in Higher Education of Georgia

- Activity Reports

- Intercomprehension and collaborative learning to interact in a plurilingual academic environment

- Teaching presentation skills through popular science: an opportunity for a collaborative and transversal approach to ESP teaching

- Japanese kana alphabet retention through handwritten reflection cards

- Decolonising the curriculum in Japanese language education in the UK and Europe

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Integration, collaboration, friendship as core messages for younger generations

- Research Articles

- Research practice and culture in European universities’ Language Centres. Results of a survey in CercleS member institutions

- Language practices in the work communities of Finnish Language Centres

- Fostering transparency: a critical introduction of generative AI in students’ assignments

- Expert versus novice academic writing: a Multi-Dimensional analysis of professional and learner texts in different disciplines

- Raising language awareness to foster self-efficacy in pre-professional writers of English as a Foreign Language: a case study of Czech students of Electrical Engineering and Informatics

- Does an autonomising scheme contribute to changing university students’ representations of language learning?

- Investigating the relationship between self-regulated learning and language proficiency among EFL students in Vietnam

- Students’ perspectives on Facebook and Instagram ELT opportunities: a comparative study

- Designing a scenario-based learning framework for a university-level Arabic language course

- Washback effects of the Portuguese CAPLE exams from Chinese university students and teachers’ perspectives: a mixed-methods study

- Students’ perception of the impact of (meta)linguistic knowledge on learning German

- Language policy in Higher Education of Georgia

- Activity Reports

- Intercomprehension and collaborative learning to interact in a plurilingual academic environment

- Teaching presentation skills through popular science: an opportunity for a collaborative and transversal approach to ESP teaching

- Japanese kana alphabet retention through handwritten reflection cards

- Decolonising the curriculum in Japanese language education in the UK and Europe