Preservation of urine specimens for metabolic evaluation of recurrent urinary stone formers

-

Tomáš Šálek

, Pavel Musil

, Rachel Marrington

, Timo T. Kouri

, Janne Cadamuro

und on behalf of the Working Group Preanalytical Phase (WG-PRE) and Task and Finish Group Urinalysis (TFG-U), European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM)

Abstract

Objectives

Stability of concentrations of urinary stone-related metabolites was analyzed from samples of recurrent urinary stone formers to assess necessity and effectiveness of urine acidification during collection and storage.

Methods

First-morning urine was collected from 20 adult calcium-stone forming patients at Tomas Bata Hospital in the Czech Republic. Urine samples were analyzed for calcium, magnesium, inorganic phosphate, uric acid, sodium, potassium, chloride, citrate, oxalate, and urine particles. The single-voided specimens were collected without acidification, after which they were divided into three groups for storage: samples without acidification (“NON”), acidification before storage (“PRE”), or acidification after storage (“POST”). The analyses were conducted on the day of arrival (day 0, “baseline”), or after storage for 2 or 7 days at room temperature. The maximum permissible difference (MPD) was defined as ±20 % from the baseline.

Results

The urine concentrations of all stone-related metabolites remained within the 20 % MPD limits in NON and POST samples after 2 days, except for calcium in NON sample of one patient, and oxalate of three patients and citrate of one patient in POST samples. In PRE samples, stability failed in urine samples for oxalate of three patients, and for uric acid of four patients after 2 days. Failures in stability often correlated with high baseline concentrations of those metabolites in urine.

Conclusions

Detailed procedures are needed to collect urine specimens for analysis of urinary stone-related metabolites, considering both patient safety and stability of those metabolites. We recommend specific preservation steps.

Introduction

Urinary stone formation has a prevalence of 7–13 % in North America, 5–9 % in Europe, and 1–5 % in Asia [1]. About 10 % of patients with urolithiasis have a high probability of recurrence, needing detailed assessment of their metabolic traits [2]. Children with urolithiasis belong to the high-risk stone formers, with a 50 % recurrence rate within three years [3]. Chemically, recurrent urinary stone formation is associated with increased concentrations of calcium, oxalate, phosphate, or uric acid that crystallize in urine, and/or with decreased concentrations of stone-inhibiting compounds, most commonly magnesium and citrate [4]. Some drugs and rare genetic defects may also create urolithiasis, e.g., due to abnormal excretion of cystine, 2,8-dihydroxyadenine, or xanthine [2].

General advice to all patients with urolithiasis is to increase their water intake up to 2.5–3 L/day to reach a low-density diuresis of 2.0–2.5 L/day. Stone-specific pharmacological treatments are additionally required for high-risk stone formers, e.g., alkalinization of urine if calcium oxalate stones are related to hypocitraturia and/or hypercalciuria [2, 5].

The metabolites associated with a high-risk for urinary stones are generally measured from standard 24 h (24 h) collections [2]. Stability of analytes in 24 h urine collections has traditionally been supported by acidification of urine with hydrochloric acid. Alternatively, single-voided specimens are used in patients not capable of 24 h collection or for simplified follow-up practice, calculating excretion rates with measurand-to-creatinine ratios.

Traditional preservation of urine with strong acids poses a safety risk to patients in home collections. It also requires aliquoting of one 24 h collection, since all measurands do not remain soluble at the same pH. Therefore, recent studies ultimately question the need of urine acidification in patient care [6], [7], [8], [9].

Results of urine preservation obtained from specimens of non-selected patients or healthy volunteers may not be applicable to preservation of urine specimens from high-risk stone formers since concentrations of stone-forming metabolites tend to be higher in urinary stone patients than those in non-selected individuals. Therefore, we investigated the need of acidification for stability of stone-related measurands in urine from patients with recurrent calcium-containing stones. This investigation was carried out on behalf of the Working Group Preanalytical Phase and Task and Finish Group Urinalysis of the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM).

Materials and methods

Twenty patients with recurrent urinary calcium stones were prospectively recruited from the Outpatient Metabolic Clinic of the Tomas Bata Hospital in Zlín, Czech Republic from June to October 2022. The local Ethics Committee approved the study (code No 2022-51), and all patients signed informed consent. Metabolic composition of the stones from these patients was assessed by infrared spectroscopy during their initial urolithiasis treatments. Ten of the 20 patients had 100 % whewellite stones (calcium oxalate monohydrate), four patients mixed whewellite–weddellite (calcium oxalate dihydrate) stones, and six patients mixed calcium oxalate – calcium apatite stones or unknown calcium stones. No patients with uric acid stones were among the studied population.

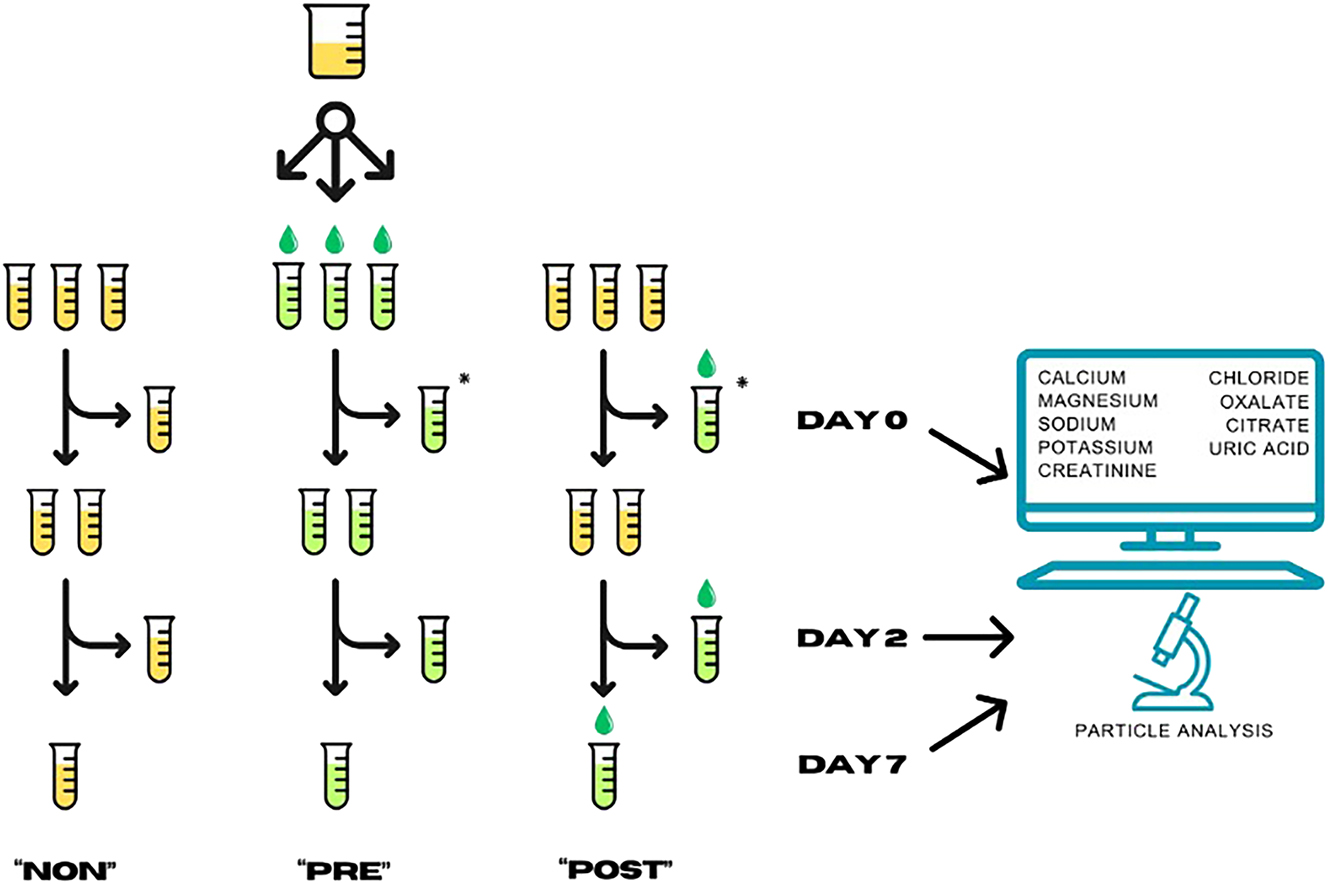

Before a routine follow-up visit to the Metabolic Clinic, single-voided urine specimens were collected at home. Each patient provided 100–200 mL of first-morning urine in a 400 mL polypropylene screw cap container without any preservatives (Dürrmann GmbH & Co. KG, Hohenlinden, Germany), and transported the specimen to the local laboratory within 2 h after voiding (The samples were delivered by patients at 7.00 a.m.). In the laboratory, the container was mixed properly, and the specimen of each patient was divided into 21 aliquots of 1 or 2.5 mL (8×1 mL for biochemistry analyses, 8×2.5 mL for automated particle analysis, and 5×1 mL for capillary electrophoresis) using 10 mL polypropylene urine tubes without additives (FL Medical, Padua, Italy). To compare different ways of preservation, the aliquoted samples were either stored and analyzed without acidification (referred to as “NON”, non-acidified), acidified before storage (referred to as “PRE”), or acidified after storage, immediately prior to analysis (referred to as “POST”) (Figure 1), like in our previous study [9]. Samples were acidified by adding 5 µL 6 M hydrochloric acid to 1 mL of urine sample to decrease their pH [10]. All aliquots were stored at room temperature (RT; 20–25 °C) only. For all oxalate and citrate measurements, the aliquots were acidified by adding 35 µL of 7 M phosphoric acid into the 1 mL aliquot as a mandatory pretreatment for capillary electrophoresis [11]. Before other measurements than particle analysis, aliquots were heated in a water bath at 56 °C for 30 min to solubilize possible crystals [12].

The system of aliquoting. The aliquots marked with an asterisk “*” were treated identically (PRE Day 0; and POST Day 0), resulting in a total of eight aliquots for biochemistry and another eight for particle analyses. Due to mandatory acidification for capillary zone electrophoresis, five aliquots were prepared for citrate and oxalate analyses only. A total of 21 aliquots were prepared from urine specimens of each patient. NON, no acidification; PRE, acidified before storage; POST, acidified after storage before analysis.

Each aliquot was measured in duplicate at three time points: (1) on the day of aliquoting (Day 0), (2) after two days of storage (Day 2), and (3) after seven days of storage (Day 7). Results from the NON aliquots measured on Day 0 served as reference concentrations (baseline) for most parameters. For oxalate and citrate measurements, the values from POST/Day 0 samples were used as reference concentrations because of the obligatory acidification for capillary electrophoresis. Concentrations in Day 0/PRE aliquots differing from those in Day 0/NON aliquots indicated changes caused solely by the acidification. Results from Day 2 aliquots modeled 24 h collections with an extra day for transportation as usual in ambulatory urine collections, with the following options: sample acidification by the patient at home (PRE), acidification of the sample in the laboratory upon arrival (POST), or no acidification (NON). Results from Day 7 were used to simulate extended storage of samples prior to batch analysis of rare analytics in the laboratory. Additionally, Day 7 aliquots confirmed changes observed in Day 2 samples if concordant.

The following measurement procedures were applied for the given urine analytes [2, 11]: calcium (uCa), magnesium (uMg), phosphate (inorganic; uPi), uric acid (uUA), sodium (uNa), potassium (uK), chloride (uCl), and creatinine (uCrea) were measured in duplicate on the Abbott Architect™ ci16200 platform (Abbott Laboratories, IL, USA). Duplicate measurements of oxalate (uOx) and citrate (uCit) were carried out by capillary electrophoresis on the CE Lumex CAPEL-205 analyzer (Lumex-Marketing LLC, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation). Details of these procedures and their analytical performance are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Additionally, a combined urinalysis was performed with iQ200 analyzer (Iris Diagnostics, Chatsworth, USA), with quantitative counts of leukocytes, erythrocytes, bacteria, and urine crystals (Supplementary Figure 1), as well as an ordinal scale test strip results including detection of ascorbic acid. Quantitation of calcium oxalate dihydrate and calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals by iQ200 was verified against visual microscopy (data not shown).

The study protocol was checked against the items provided in the EFLM Checklist for Reporting Stability Studies (CRESS) [13]. The relative deviations from baseline concentrations were calculated as percent differences, PD(%). Criteria of preservation were obtained from the limits recommended in the EFLM European Urinalysis Guideline 2023 for preservation of quantitative chemical measurands in urine, suggesting a desirable PD within 10 %, or a maximum permissible difference, MPD(%), within 20 % from the original concentration, based on biological variation of the analyzed metabolites [14]. Changes in metabolite concentrations in urine do not necessarily follow linear functions over time because of variable rate of precipitation in a complex matrix at room temperature. Instead of a general instability equation recommended by the CRESS [13], we chose two practically important preservation times (Day 2 and Day 7), and statistical assessment of analytical imprecision that would allow for sensitive detection of PD from baseline concentrations at these time points.

Statistically significant relative difference detectable between two measurements was modeled by using Gaussian distribution, also used to calculate reference change values (RCV) [15]:

where PD(%)=percent difference, z=Gaussian statistic, and CV=coefficient of variation in the measurements.

In duplicate measurements, the observed analytical variation, CVA, is reduced by √2:

Using Gaussian statistic z=1.96, probability α (unidirectional specificity) of false detection of difference is 2.5 %, with a sensitivity of detection (1 − β) 50 %. To reach a sensitivity of 85 %, a value of z=3 must be used [16]. The PD that is detectable with the shown imprecision follows then the equation:

Microsoft Excel Office 2016 (Microsoft, Washington, USA) was used for data collection and PD% calculations [13]. GraphPad Prism 9 (Boston, MA, USA) was used for graph generation.

Results

Analytical performance of measurements

Intermediate reproducibility, expressed as mean of analytical variation, CVA, of two measured control levels daily, was less than 3 % in all Abbott Architect™ procedures, and less than 4 % in CE Lumex capillary electrophoresis of uCit and uOx (Supplementary Table 1). The obtained intermediate reproducibility allowed detection of a PD of 10 % by the used Abbott™ automated procedures, and a PD of 12 % with capillary electrophoresis by CE Lumex CAPEL–205 between two sequential measurements, using Eq. (3), satisfying the imprecision of both instruments to detect a MPD of 20 %.

Summary of measurements

The median age of the eight female and 12 male patients was 47 years (range 18–77 years). A summary of the baseline concentrations of both non-acidified (NON) and immediately acidified (PRE) aliquots on Day 0 is shown in Table 1. Acidification (PRE) changed the Day 0 concentrations of uCl only, due to the addition of HCl. Measurand-to-creatinine ratios (mmol/mmol) allowed comparisons to health-related reference limits and gave arbitrary comparisons to clinical attention limits (mmol/day). The median uCrea concentration was 8.7 mmol/L in NON-acidified morning specimens. Densities of the first-morning specimens improved detection of stone-forming tendency of the patients as compared to dilute specimens after enhanced diuresis during the day. In four patients, uCrea was 15 mmol/L or higher. The highest measurand-to-creatinine ratios (mmol/mmol) of the stone-forming metabolites calcium, phosphate, uric acid, and oxalate exceeded the health-related upper limits of those metabolites in PRE/Day 0 aliquots of urine samples (Table 1).

Concentrations of urine measurands and their ratios to creatinine in the initial samples (Day 0).

| Aliquot | NONa, Day 0 | PREa, Day 0 | PRE, Day 0 | Diagnostic limits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | Measurand concentrations, mmol/L | Measurand-to-creatinine ratios, mmol/mmol | Health-related reference limitse, mmol/mmol |

Clinical decision limitsf, mmol/day |

||||

| Measurand | Median | Rangeb | Median | Rangeb | Median | Rangeb | Reference interval | Limit of attention |

| Sodium | 95 | 20–193 | 95 | 20–192 | ||||

| Potassium | 21 | 3.2–49 | 20 | 3.1–49 | ||||

| Chloridea | 90 | 20–160 | 117 | 45–188 | ||||

| Creatinine | 8.7 | 2.8–18.5 | 8.6 | 2.7–18.0 | n/ad | n/ad | 7–13 (F), 13–18 (M)d | |

| Magnesium | 3.3 | 1.0–9.2 | 3.4 | 1.1–9.2 | 0.38 | 0.14–0.71 | 0.2–0.5 | <3 |

| Calcium | 3.8 | 0.8–13.5 | 3.7 | 0.8–13.5 | 0.54 | 0.18–1.50 | 0.00–0.60 | >5 or >8 |

| Phosphate | 25 | 5.6–63 | 25.2 | 5.6–63 | 2.77 | 1.44–6.35 | 0–2.8 | >35 |

| Uric acid | 2.1 | 0.7–4.3 | 2.0 | 0.7–4.3 | 0.23 | 0.14–0.45 | 0.10–0.30 | >4 (F), >5 (M) |

| Oxalate | n/a | 0.19 | <0.09c–0.44 | 0.024 | 0.010–0.067 | 0.000–0.040 | >0.5 or >1.0 | |

| Citrate | n/a | 1.6 | <0.2c–4.4 | 0.20 | <0.03c–0.65 | >.0.15 | <1.9 (F), <1.7 (M) | |

-

aConcentrations of chloride in pre-acidified samples (PRE) against those in non-acidified samples (NON) show the impact of added HCl. bRanges indicate minimum and maximum concentrations. cLowest concentrations were below the shown limits of quantitation. dMeasured urine creatinine concentrations are given in mmol/day units only, as this is the reference analyte; n/a, not applicable. eHealth-related upper reference limits were taken from Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics [17]. fClinical decision limits for medical attention are from the EAU Guideline on Urolithiasis 2023 [2].

Creatinine concentrations (uCrea) in NON/Day 0 urine samples correlated with NON/Day 0 concentrations of uMg (rS=0.729), uPi (rS=0.839) and uUA (rS=0.868), and with PRE/Day 0 concentrations of uOx (rS=0.770) and uCit (rS=0.613) (two-tailed p <0.01 for these regressions; rS=Spearman’s rank coefficient of correlation), reflecting importance of diuresis in urine concentrations of these metabolites. On the contrary, correlation of NON/Day 0 uCrea with that of uCa was less significant (rS=0.408; p=0.075). Percent reduction of uCa from the NON/Day 0 to Day 7 samples, correlated both with baseline concentrations of uCa (rS=−0.677; p<0.01) and uCrea (rS=−0.635; p<0.01) in NON/Day 0 samples, suggesting a role for both baseline uCa and urine density in calcium precipitation.

Stability failures of measurands in individual samples

The number of samples (out of 20) that failed to preserve their baseline concentrations (NON/Day 0) of the tested measurands at different storage conditions (NON, PRE and POST) are shown in Table 2. The figures show the number of samples exceeding both the PD 10 % and the MPD 20 % limit (by either decreases or increases in concentrations). The clinically most important failures exceeded MPD 20 % already on Day 2: the urine of one patient failed in uCa stability in NON-acidified samples, and those of three patients failed in uOx stability in PRE-acidified samples (shown in red; Table 2). Among the POST-acidification samples, preservation of uOx failed in three cases and uCit in one case on Day 2 (also in red; Table 2). Stability of uMg, uCa, uPi, and uCit was observed up to 7 days in the PRE-acidified samples only (Table 2). A storage up to 7 days at room temperature changed the concentrations of uNa, uK, uCl or uCrea <PD 10 % (data not shown).

Number of samples with failures of preservation over different conditionsa.

| Condition, Day of analysis | Failure size, % | Magnesium | Calcium | Phosphate | Uric acid | Oxalate | Citrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NON b, Day 2 | PDb>10 % | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | n/ad | n/a |

| >MPDb 20 % | 0 | 1c | 0 | 0 | n/a | n/a | |

| NON, Day 7 | PD>10 % | 3 | 6 | 4 | 2 | n/a | n/a |

| >MPD 20 % | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | n/a | n/a | |

| PRE, Day 0 | PD>10 % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

| >MPD 20 % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a | n/a | |

| PRE, Day 2 | PD>10 % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 2 |

| >MPD 20 % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3c | 0 | |

| PRE, Day 7 | PD>10 % | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 16 | 6 |

| >MPD 20 % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 0 | |

| POST, Day 2 | PD>10 % | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 5 |

| MPD>20 % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3c | 1c | |

| POST, Day 7 | PD>10 % | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 14 | 9 |

| >MPD 20 % | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 7 |

-

aThe failures of preservation in urine aliquots of the 20 patients against concentrations in NON/Day 0 urine samples in the conditions explained in Figure 1. Differences of concentrations in PRE/Day 0 samples against those in NON/Day 0 samples are shown as a control (brownish shading). bMPD, maximum permissible difference (%), PD, percent difference (%) from the non-acidified (NON), or for oxalate and citrate, from the pre-acidified (PRE) concentration on Day 0; PRE, acidified before the storage period; POST, acidified after the storage period. cThe critical failures in sample preservation after 2 days of storage (MPD>20 %) are shown red. The frequencies exceeding MPD 20 % are shaded grey. dn/a, not applicable. Since addition of phosphoric acid was needed for measuring oxalate and citrate, comparisons to NON/Day 0 specimens were not possible.

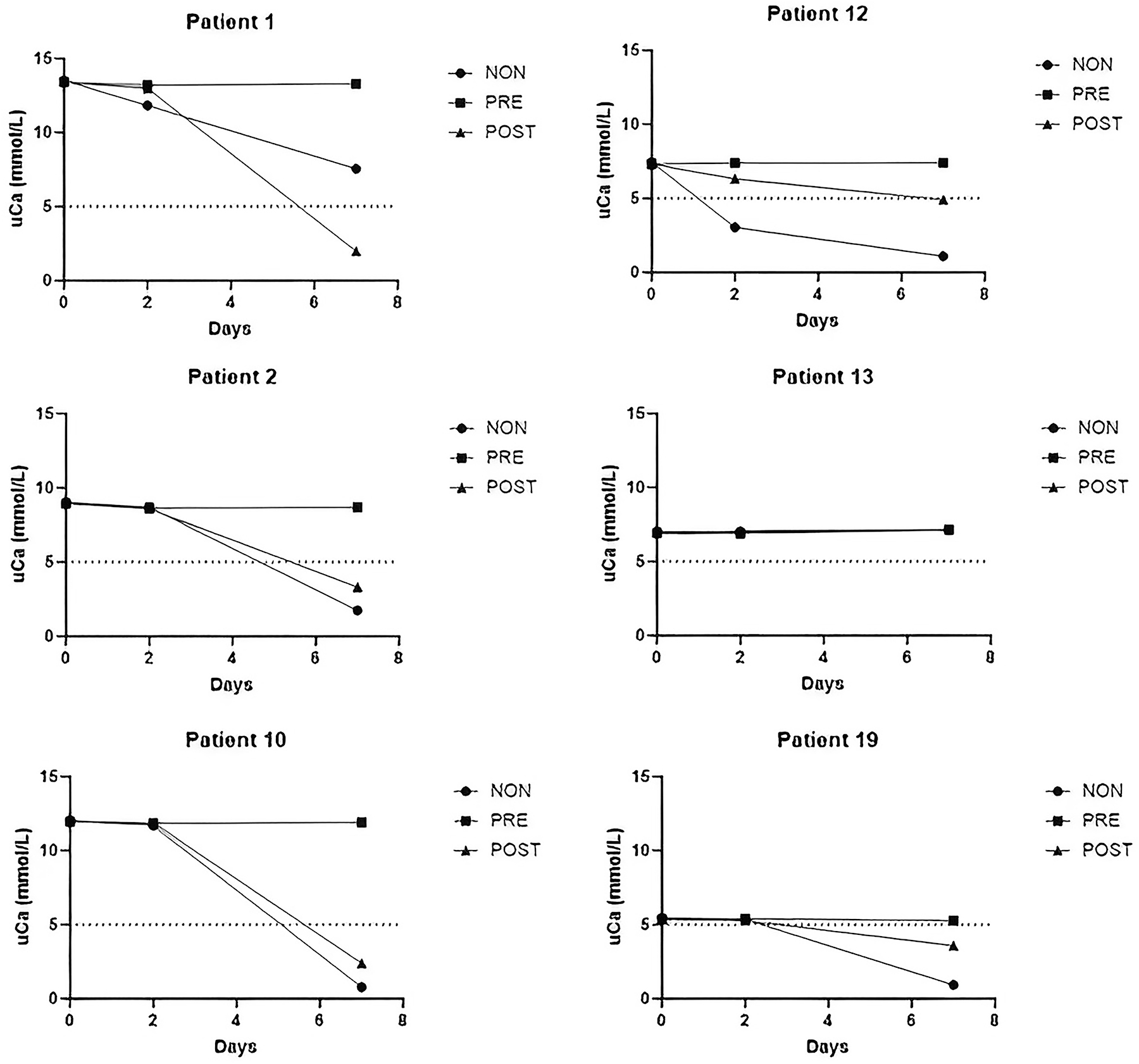

The median excretion of calcium into urine was 0.54 mmol/mmol Crea (Table 1). Calculated from the average creatinine excretion of 10–15 mmol/day, the daily calcium output of the patients had a median of 5–8 mmol/day, corresponding to the clinical limit of medical attention, compatible with this patient group (Table 1). After a 2-day storage, uCa concentrations of two NON-acidified samples decreased significantly: the highest PD of −59 % from the original uCa of 7.5 mmol/L was seen in the NON sample of Patient 12, and another smaller PD of −13 % in the NON sample of Patient 1 (Figure 2). Patient 12 had a clear hematuria (104 RBC*106/L in urine at uCrea=10.0 mmol/L). Patient 1 had the highest baseline uCa of 13.5 mmol/L among the patients, in parallel with a uPi of 63.2 mmol/L and uUA of 3.4 mmol/L at uCrea=15 mmol/L. It is probable that co-morbidities such as hematuria, or a high baseline uCa concentration reflected the risk for calcium precipitation in these two patients. Increased amounts of calcium oxalate (CaOx) crystals were seen in five NON samples on Day 2, and in seven NON samples on Day 7, correlating only vaguely with decreased uCa concentrations (rS=−0.416; p=0.068) or increased uOx concentrations in PRE Day 7 samples (rS=0.464; p<0.039).

Changes in urine calcium concentration (uCa) in samples from six patients with a baseline concentration of 5 mmol/L or more, stored with variable acidification for 2 and 7 days. NON, no acidification; PRE, acidified before storage; POST, acidified after storage before analysis.

Acidification after two days of storage at RT (POST/Day 2) provided reasonable preservation for uMg, uCa, and uPi, but a single patient (Patient 12 with hematuria) had PD −15 % of uCa, suggesting that POST-acidification of urine often improves stability of uCa, but not always. A prolonged storage before acidification (POST/Day 7) was not capable of retrieving the baseline uCa in the same five cases that failed in NON/Day 7 samples (Table 2).

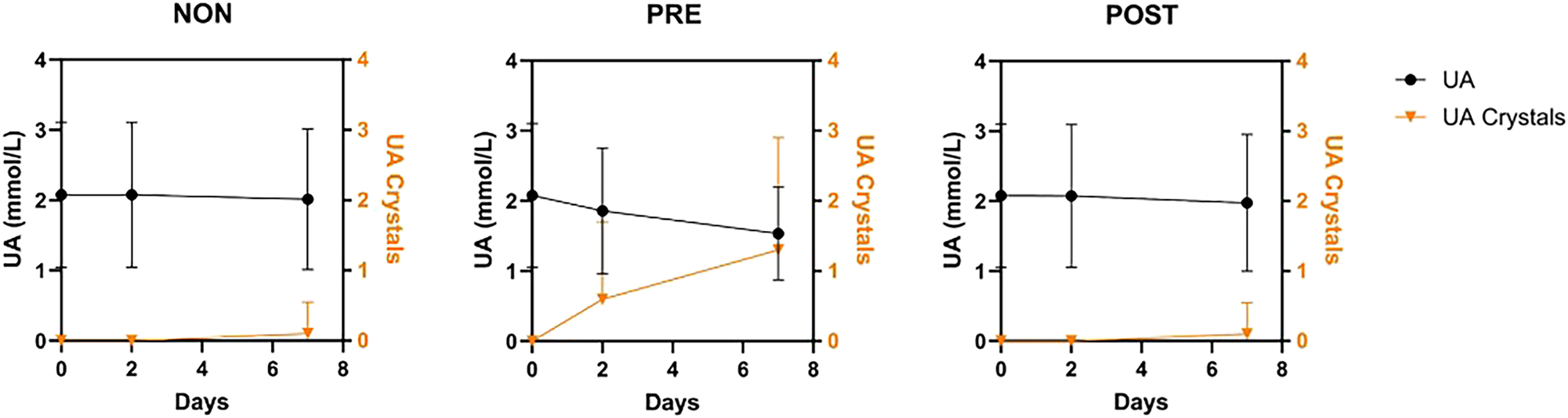

Excretion of uric acid had a maximum of 0.45 mmol/mmol Crea in PRE/Day 0 samples (Table 1). Only the highest excretions reached the clinical attention limit of 4–5 mmol/day since the patients did not have uric acid stones. Concentrations of urinary uric acid (uUA) were well preserved in the NON/Day 2 and POST/Day 2 samples. Among the PRE-acidified samples, changes in uUA on Day 2 exceeded the MPD 20 % in 4/20 samples (Patients 1, 2, 13, and 16), with a PD range from −24 % to −44 %, and on Day 7 in 6/20 samples (Patients 1, 2, 4, 11, 13, and 16), with PDs from −41 % to −74 % (Table 2). The decrease of mean uUA concentration parallelled with increased precipitation of uric acid crystals in PRE samples (Figure 3). Five of the six failing patients had the highest baseline uUA of the group.

Parallel reduction in mean of uric acid concentration (UA, mmol/L) and precipitation of uric acid crystals in PRE-acidified samples during storage. Means (instead of medians) of ordinal quantities from 0 to 4 were used to express precipitation of UA because less than half of the specimens demonstrated the UA crystals.

The highest concentration of oxalate in urine, uOx, was 0.44 mmol/L in PRE/Day 0 and Day 2 samples. Estimating from the average daily excretion of 10–15 mmol creatinine, the highest excretions reached clinical attention limits of 0.5–1 mmol/day for hyperoxaluria (Table 1). The MPD 20 % was reached or exceeded in 3/20 of PRE/Day2 uOx samples with PD +20 %, +24 %, and −26 % from Patients 5, 1 and 4, respectively (Table 2). On Day 7, five PRE samples exceeded the MPD 20 % in uOx (PD up to +121 %; Patients 12, 19, 5, 2, and 1). In POST/Day2 and Day 7 aliquots, three (PD −25 %, +22 %, and +23 %) and eight (one PD −29 %, seven +21 % to +63 %) samples exceeded the MPD 20 % in uOx, respectively (Table 2). These failures showed the incapability of HCl to stabilize uOx. Ascorbic acid was detected with a test strip in one sample only, without a concomitant change in uOx concentration.

Concentrations of citrate in urine (uCit) ranged from <0.2 mmol/L (one patient) to 4.4 mmol/L, with a median of 1.6 mmol/L or 0.20 mmol/mmol Crea. Calculating from 10–15 mmol of creatinine excretion, the median citrate excretion was 2–3 mmol/day (Table 1). In PRE samples, none of the cases exceeded the MPD 20 % limit on Day 2 or 7. The PDs in uCit were larger in POST acidification samples on Day 2 and Day 7 (Table 2).

Patient 17 had leukocytes in the urine sample with 265 WBC×106/L and a uCrea of 9.4 mmol/L on Day 0. This pyuria was not associated with increased concentrations of uCa or uUA in that sample.

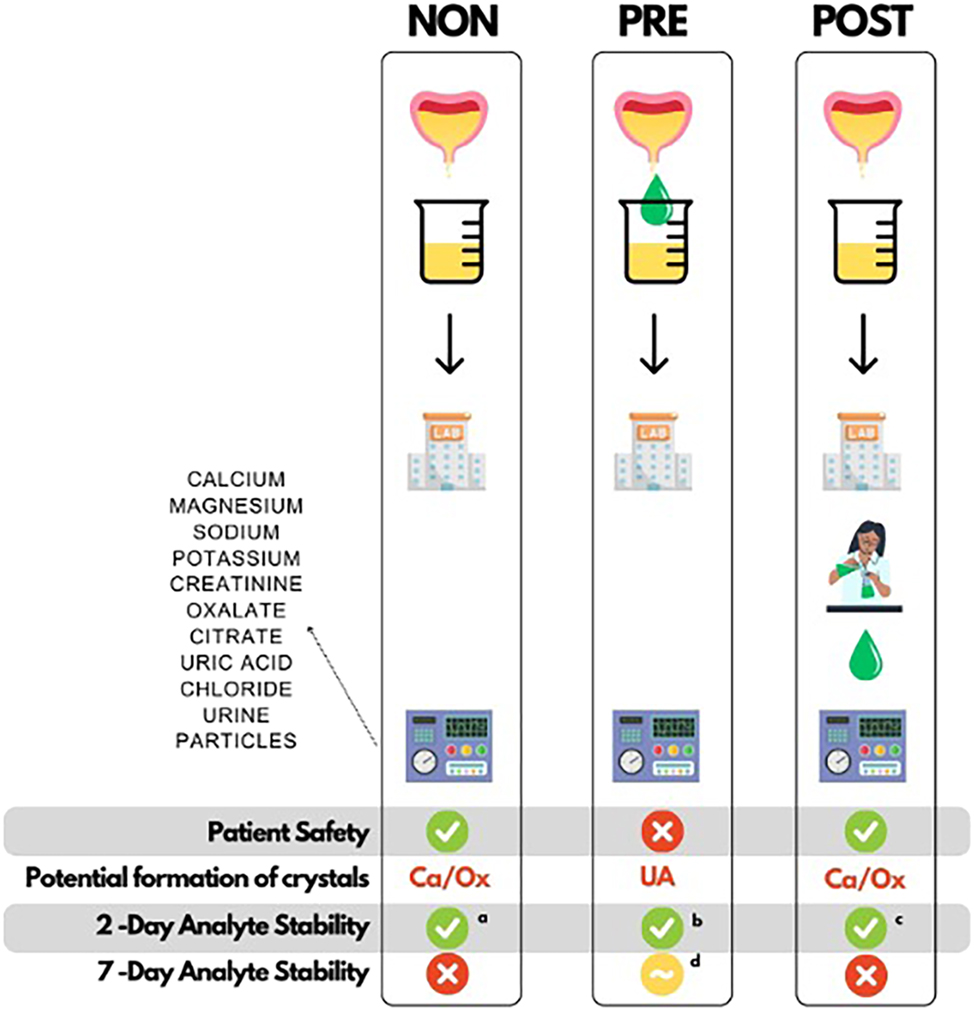

Discussion

This stability study evaluated the need and effectiveness of acidification to preserve stone-forming metabolites in urine collections from patients with a high risk of recurrent urinary stones. After two days of storage at RT, concentrations of stone-related metabolites uMg, uCa, uPi, uUa, uOx, and uCit were within the acceptability limits in most samples either within PD <10 % (optimum) or PD <MPD 20 % (maximum permissible) level, regardless of the type of acidification (Table 2). However, occasional failures were found already after 2 days, and frequently after 7 days, confirming the doubt of reduced stability of metabolites in patient specimens, often associated with high baseline concentrations (Figure 4).

Advantages and disadvantages of the different acidification approaches in the preservation of urine metabolites from calcium stone-forming patients. NON, no acidification; PRE, acidified before storage; POST, acidified after storage before analysis; Ca/Ox, calcium oxalate crystals; UA, uric acid crystals; uCa, calcium concentration in urine; uOx, oxalate concentration in urine; uCit, citrate concentration in urine; uUA, uric acid concentration in urine. PD, percent difference from baseline concentration; MPD, maximum permissible difference. Explanations to superscripts: a–cnumber of failed cases (PD% >MPD 20 %) out of the 20 samples (and patients) after 2 days of storage: aone uCa; bfour uUA and three uOx; cthree uOx and one uCit. dStability of several PRE samples failed in uOx and uUA analyses after 7 days of storage.

In NON-acidified samples, the stability of uCa failed (PD>MPD 20 %) in the sample of Patient 12, having hematuria (Figure 2). Thus, other urine tests than those of stone-related measurands are also required to identify possible particles or substances interfering with the preservation. Patient 1 (PD −13 %) had a baseline uCa concentration of 13.5 mmol/L and a calcium-to-creatinine ratio of 0.88 mmol/mmol, exceeding the health-related excretion rate of 0.60 mmol/mmol (Table 1). Decreases in uCa occurred in five out of six specimens with uCA >5 mmol/L on Day 7 (Figure 2), confirming the role of high baseline uCa in calcium precipitation [8].

The PRE-acidified samples modeled acidification by the patient at home. Stability of uCa, uMg, uPi, and uCit concentrations was improved with PRE-acidification for up to 7 days. However, stability of uOx failed (PD>MPD 20 %) in three PRE samples already after 2 days with variable changes in uOx (Table 2). Mean uUA decreased after acidification with a parallel development of uric acid crystals in PRE samples (Figure 3). Baseline uUA correlated closely with uCrea (density of specimens) (rS=0.868; p<0.01), supporting the role of diuresis in the development of uric acid stones [2]. Since neither uOx nor uUA were stabilized with PRE-acidification, alternate procedures are needed for their preservation [14] (Figure 4).

The POST samples modeled acidification of the urine specimen at reception in the laboratory to avoid safety risks to patients. We could demonstrate the stability of uCa except for one hematuria patient, while uMg, uPi, and uUA were acceptable when stored at RT for 2 days before acidification. However, three uOx and one uCit exceeded the MPD 20 % in POST/Day 2 samples. None of the measurands was properly stabilized in POST samples for 7 days (Table 2; Figure 4). The variability of uOx during storage in vitro depends on baseline ascorbic acid concentration and is increased in alkaline pH, partially from unknown sources [18, 19]. CaOx crystallization in POST Day 2 and Day 7 samples, like that in NON samples, was not related to baseline uOx or uCa concentrations, as reported earlier [20].

Recommendations

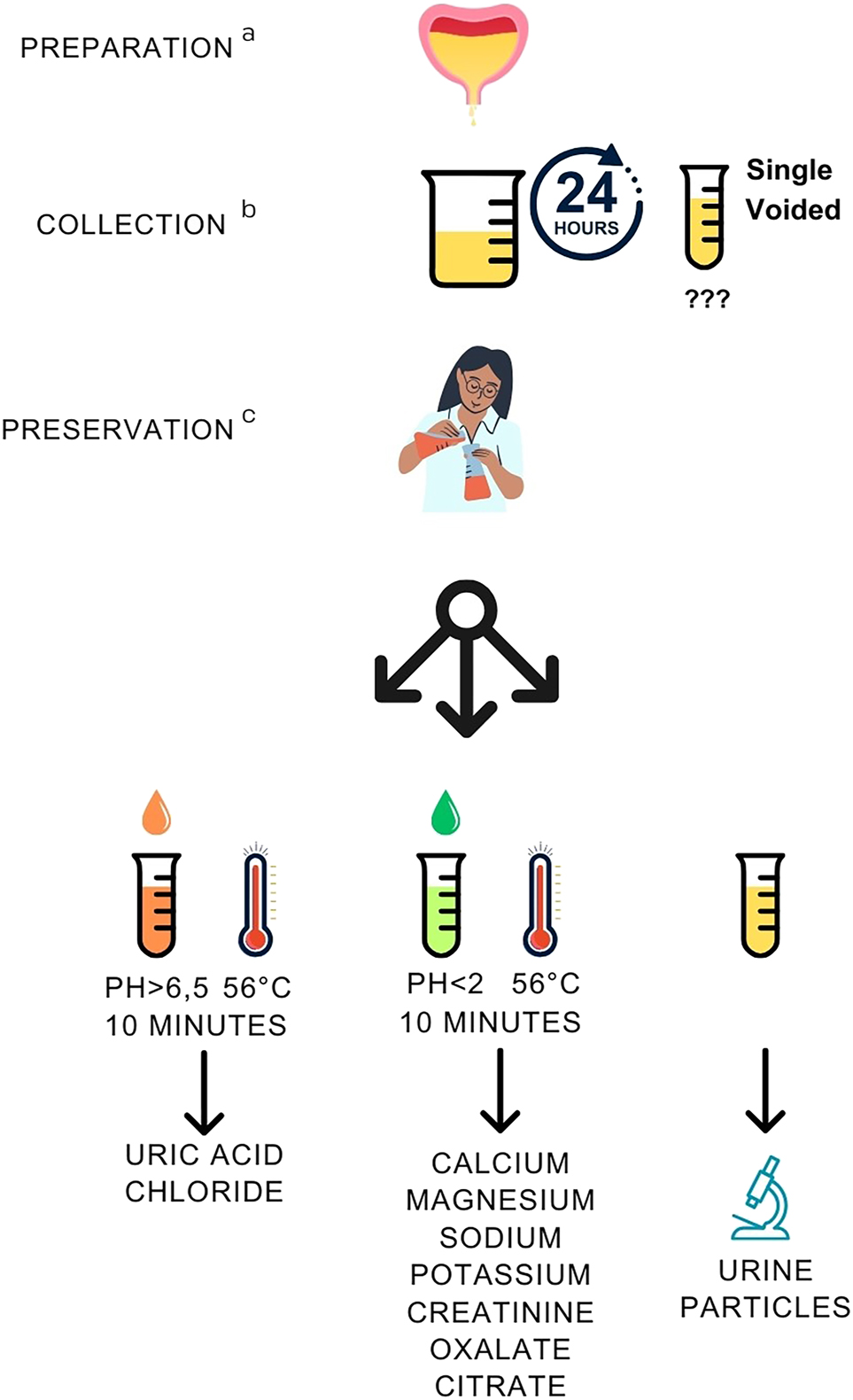

The following practical recommendations can be concluded for collection of urine for measurements of stone-forming metabolites (Figure 5):

Recommendations for patient preparation, collection, and preservation of urine specimens for measuring metabolites associated with urinary stones. aPreparation: collection with increased diuresis up to 2.5 L/day; no vitamin C intake. Preparation applies to follow-up measurements only; regular diuresis and diet are recommended for primary diagnostics to document the stone-forming tendency. bCollection: 24 h collection (reference); single-voided urine (follow-up, selected cases). cPreservation: after measuring pH, divide the sample into 1–3 aliquots for different metabolites and preservatives, guided by the type of urinary stone. Measurement at pH >6.5 is needed for uric acid (precipitates in acidic pH) and chloride (HCl used for acidification interferes with original concentration).

Patient preparation

An increased urine output of 2.0–2.5 L/day is recommended by drinking enough water (2.5–3.0 L/day), in the follow-up of patients [2]. In primary diagnostic evaluation, regular diuresis enables detection of stone-forming tendency of the patient. Vitamin C supplementation with non-physiological doses is to be avoided since it is metabolized to oxalate [21].

Collection

A timed 24 h collection of urine is recommended as a reference procedure, with duplicate collections at initial diagnostics because of large intra-individual biological variation, CVI [2, 14]. The CVI of creatinine concentration in urine is 24 % while that of stone-associated metabolites ranges from 24 to 45 % [22]. Single-voided urine specimen is collected from non-toilet trained children, and adults with limited control of micturition. Then, metabolite excretion is reported as metabolite-to-creatinine ratio (Table 1) to balance the effect of diuresis, which reduces CVI of excretion. Single-voided specimens were worth assessments, since they support compliance in the follow-up of patients [20, 23]. They are anyway often requested for analysis of urine particles and bacterial culture. Spot specimens delivered at the laboratory may be directly given to healthcare personnel, reducing the delays and safety risks in preservative additions [24]. Despite these benefits, excretion rates calculated from measurand-to-creatinine ratios should be evaluated against timed 24 h collections to confirm the diagnostic performance and clinically relevant decision limits.

Preservation

After arrival, pH of the specimen should be measured [25], and the aliquots preserved (1) by alkalinization for measurements of uUA and uCl (pH>6.5), (2) by acidification for measurements of uCa, uMg, uNa, uK, uCrea, uOx and uCit (pH<2) [12, 25], or (3) by additional freezing at −20 °C of the acidified uOx and uCit samples (Figure 5).

Specific preservatives are used for urine particles and bacterial culture if needed for transportation [14]. During 24 h urine collection, thymol (1 g/L urine, diluted from a stock of 10 % thymol w/v in isopropanol) prevents microbial growth if refrigeration is not possible [26]. To preserve ascorbic acid, disodium EDTA has been recommended to inhibit its conversion to oxalate [19].

Acknowledgments

This study was performed on behalf of the Working Group Preanalytical Phase (WG-PRE) and Task and Finish Group Urinalysis (TFG-U) of the EFLM. The data and recommendations were endorsed by the EFLM WG-PRE and TFG-U, and finally approved by the Chair of WG-PRE (Janne Cadamuro) and the Chair of TFG-U (Timo Kouri), the shared senior authors of this document. According to the EFLM type 2 publication procedure, the manuscript was reviewed and approved by the Chair of the EFLM Science Committee (Michel Langlois), and the EFLM Executive Board was notified prior to submission to the journal.

-

Research ethics: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Sorokin, I, Mamoulakis, C, Miyazawa, K, Rodgers, A, Talati, J, Lotan, Y. Epidemiology of stone disease across the world. World J Urol 2017;35:1301–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-017-2008-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Skolarikos, A, Jung, H, Neisius, A, Petřík, A, Somani, B, Tailly, T, et al.. European Association of Urology (EAU) Guidelines on urolithiasis. Arnhem, The Netherlands: EAU Guidelines Office; 2024. https://uroweb.org/guideline/urolithiasis/ [Accessed 24 May 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

3. Tasian, GE, Kabarriti, AE, Kalmus, A, Furth, SL. Kidney stone recurrence among children and adolescents. J Urol 2017;197:246–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2016.07.090.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Wang, K, Ge, J, Han, W, Wang, D, Zhao, Y, Shen, Y, et al.. Risk factors for kidney stone disease recurrence: a comprehensive meta-analysis. BMC Urol 2022;22:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-022-01017-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Tiselius, HG. Metabolic risk-evaluation and prevention of recurrence in stone disease: does it make sense? Urolithiasis 2016;44:91–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-015-0840-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Pratumvinit, B, Reesukumal, K, Wongkrajang, P, Khejonnit, V, Klinbua, C, Dangneawnoi, W. Should acidification of urine be performed before the analysis of calcium, phosphate, and magnesium in the presence of crystals? Clin Chim Acta 2013;426:46–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2013.08.025.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Petit, M, Beaudeux, JL, Majoux, S, Hennequin, C. Is a pre-analytical process for urinalysis required? Ann Biol Clin 2017;75:519–24. https://doi.org/10.1684/abc.2017.1271.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Chenevier-Gobeaux, C, Rogier, M, Dridi-Brahimi, I, Koumakis, E, Cormier, C, Borderie, D. Pre-post- or no acidification of urine samples for calcium analysis: does it matter? Clin Chem Lab Med 2020;58:33–9. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2019-0606.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Cadamuro, J, Decho, C, Frans, G, Auer, S, von Meyer, A, Kniewallner, KM, et al.. Acidification of 24-hour urine in urolithiasis risk testing: an obsolete relic? Clin Chim Acta 2022;532:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2022.05.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Feres, MC, Bini, R, De Martino, MC, Biagini, SP, de Sousa, AL, Campana, PG, et al.. Implications for the use of acid preservatives in 24-hour urine for measurements of high demand biochemical analytes in clinical laboratories. Clin Chim Acta 2011;412:2322–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2011.08.033.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Holmes, RP. Measurement of urinary oxalate and citrate by capillary electrophoresis and indirect ultraviolet absorbance. Clin Chem 1995;41:1297–301. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/41.9.1297.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Ng, RH, Menon, M, Ladenson, JH. Collection and handling of 24-hour urine specimens for measurement of analytes related to renal calculi. Clin Chem 1984;30:467–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/30.3.467.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Cornes, M, Simundic, AM, Cadamuro, J, Costelloe, SJ, Baird, G, Kristensen, GBB, et al.. The CRESS checklist for reporting stability studies: on behalf of the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM) Working Group for the Preanalytical Phase (WG-PRE). Clin Chem Lab Med 2021;59:59–69. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2020-0061.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Kouri, T, Hofmann, W, Falbo, R, Oyaert, M, Pestel-Caron, M, Schubert, S, et al.; On behalf of the Task and Finish Group Urinalysis (TFG-U), European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM). The EFLM European Urinalysis Guideline 2023. Clin Chem Lab Med 2024;62:10.10.1515/cclm-2024-0070Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Fraser, CG. Reference change values. Clin Chem Lab Med 2012;50:807–12. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2011.733.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Iglesias, CN, Hyltoft Petersen, P, Jensen, E, Ricos, C, Jorgensen, PE. Reference change values and power functions. Clin Chem Lab Med 2004;42:415–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2004.073.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Roberts, WE, McMillin, GA, Burtis, CA, Burns, DE. Chapter 56 – reference information for the clinical laboratory. In: Burtis, CA, Ashwood, ER, Burns, DE, editors. Tietz textbook of clinical chemistry and molecular diagnostics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 2006.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Mazzachi, BC, Teubner, JK, Ryall, RL. Factors affecting measurement of urinary oxalate. Clin Chem 1984;30:1339–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/30.8.1339.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Chalmers, AH, Cowley, DM, McWhinney, BC. Stability of ascorbate in urine: relevance to analyses for ascorbate and oxalate. Clin Chem 1985;31:1703–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/31.10.1703.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Tiselius, HG, Daudon, M, Thomas, K, Seitz, C. Metabolic work-up of patients with urolithiasis: indications and diagnostic algorithm. Eur Urol Focus 2017;3:62–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2017.03.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Baxmann, AC, Mendonça, C, de, OG, Heilberg, IP. Effect of vitamin C supplements on urinary oxalate and pH in calcium stone-forming patients. Kidney Int 2003;63:1066–71. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00815.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Ricós, C, Alvarez, V, Cava, F, García-Lario, JV, Hernández, A, Jiménez, CV, et al.. Current databases on biological variation: pros, cons and progress. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1999;59:491–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365519950185229.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Parks, JH, Asplin, JR, Coe, FL. Patient adherence to long-term medical treatment of kidney stones. J Urol 2001;166:2057–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005392-200112000-00011.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Ferraz, RR, Baxmann, AC, Ferreira, LG, Nishiura, JL, Siliano, PR, Gomes, SA, et al.. Preservation of urine samples for metabolic evaluation of stone-forming patients. Urol Res 2006;34:329–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-006-0064-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Williams, JCJ, Gambaro, G, Rodgers, A, Asplin, J, Bonny, O, Costa-Bauzá, A, et al.. Urine and stone analysis for the investigation of the renal stone former: a consensus conference. Urolithiasis 2021;49:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-020-01217-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Wang, X, Gu, H, Palma-Duran, SA, Fierro, A, Jasbi, P, Shi, X, et al.. Influence of storage conditions and preservatives on metabolite fingerprints in urine. Metabolites 2019;9:203. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9100203.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2024-0773).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Blood self-sampling: friend or foe?

- Reviews

- Blood self-sampling devices: innovation, interpretation and implementation in total lab automation

- Salivary fatty acids in humans: a comprehensive literature review

- Opinion Papers

- EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) recommendations for reinforcing cyber-security and managing cyber-attacks in medical laboratories

- Point-of-care testing: state-of-the art and perspectives

- A standard to report biological variation data studies – based on an expert opinion

- Ethical Checklists for Clinical Research Projects and Laboratory Medicine: two tools to evaluate compliance with bioethical principles in different settings

- Guidelines and Recommendations

- Assessment of cardiovascular risk and physical activity: the role of cardiac-specific biomarkers in the general population and athletes

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- Clinical utility of regions of homozygosity (ROH) identified in exome sequencing: when to pursue confirmatory uniparental disomy testing for imprinting disorders?

- An ultrasensitive DNA-enhanced amplification method for detecting cfDNA drug-resistant mutations in non-small cell lung cancer with selective FEN-assisted degradation of dominant somatic fragments

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- The biological variation of insulin resistance markers: data from the European Biological Variation Study (EuBIVAS)

- The surveys on quality indicators for the total testing process in clinical laboratories of Fujian Province in China from 2018 to 2023

- Preservation of urine specimens for metabolic evaluation of recurrent urinary stone formers

- Performance evaluation of a smartphone-based home test for fecal calprotection

- Implications of monoclonal gammopathy and isoelectric focusing pattern 5 on the free light chain kappa diagnostics in cerebrospinal fluid

- Development and validation of a novel 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (C4) liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method and its utility to assess pre-analytical stability

- Establishment of ELISA-comparable moderate and high thresholds for anticardiolipin and anti-β2 glycoprotein I chemiluminescent immunoassays according to the 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria and evaluation of their diagnostic performance

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Capillary blood parameters are gestational age, birthweight, delivery mode and gender dependent in healthy preterm and term infants

- Reference intervals and percentiles for soluble transferrin receptor and sTfR/log ferritin index in healthy children and adolescents

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Detection of serum CC16 by a rapid and ultrasensitive magnetic chemiluminescence immunoassay for lung disease diagnosis

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- The role of functional vitamin D deficiency and low vitamin D reservoirs in relation to cardiovascular health and mortality

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Letters to the Editor

- EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) survey on cybersecurity

- Comment on Lippi et al.: EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) recommendations for reinforcing cyber-security and managing cyber-attacks in medical laboratories

- Six Sigma in laboratory medicine: the unfinished symphony

- Navigating complexities in vitamin D and cardiovascular health: a call for comprehensive analysis

- Simplified preanalytical laboratory procedures for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in patients treated with high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) and glucarpidase

- New generation of Abbott enzyme assays: imprecision, methods comparison, and impact on patients’ results

- Correction of negative-interference from calcium dobesilate in the Roche sarcosine oxidase creatinine assay using CuO

- Two cases of MTHFR C677T polymorphism typing failure by Taqman system due to MTHFR 679 GA heterozygous mutation

- A falsely elevated blood alcohol concentration (BAC) related to an intravenous administration of phenytoin sodium

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Blood self-sampling: friend or foe?

- Reviews

- Blood self-sampling devices: innovation, interpretation and implementation in total lab automation

- Salivary fatty acids in humans: a comprehensive literature review

- Opinion Papers

- EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) recommendations for reinforcing cyber-security and managing cyber-attacks in medical laboratories

- Point-of-care testing: state-of-the art and perspectives

- A standard to report biological variation data studies – based on an expert opinion

- Ethical Checklists for Clinical Research Projects and Laboratory Medicine: two tools to evaluate compliance with bioethical principles in different settings

- Guidelines and Recommendations

- Assessment of cardiovascular risk and physical activity: the role of cardiac-specific biomarkers in the general population and athletes

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- Clinical utility of regions of homozygosity (ROH) identified in exome sequencing: when to pursue confirmatory uniparental disomy testing for imprinting disorders?

- An ultrasensitive DNA-enhanced amplification method for detecting cfDNA drug-resistant mutations in non-small cell lung cancer with selective FEN-assisted degradation of dominant somatic fragments

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- The biological variation of insulin resistance markers: data from the European Biological Variation Study (EuBIVAS)

- The surveys on quality indicators for the total testing process in clinical laboratories of Fujian Province in China from 2018 to 2023

- Preservation of urine specimens for metabolic evaluation of recurrent urinary stone formers

- Performance evaluation of a smartphone-based home test for fecal calprotection

- Implications of monoclonal gammopathy and isoelectric focusing pattern 5 on the free light chain kappa diagnostics in cerebrospinal fluid

- Development and validation of a novel 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (C4) liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method and its utility to assess pre-analytical stability

- Establishment of ELISA-comparable moderate and high thresholds for anticardiolipin and anti-β2 glycoprotein I chemiluminescent immunoassays according to the 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria and evaluation of their diagnostic performance

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Capillary blood parameters are gestational age, birthweight, delivery mode and gender dependent in healthy preterm and term infants

- Reference intervals and percentiles for soluble transferrin receptor and sTfR/log ferritin index in healthy children and adolescents

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Detection of serum CC16 by a rapid and ultrasensitive magnetic chemiluminescence immunoassay for lung disease diagnosis

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- The role of functional vitamin D deficiency and low vitamin D reservoirs in relation to cardiovascular health and mortality

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Letters to the Editor

- EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) survey on cybersecurity

- Comment on Lippi et al.: EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) recommendations for reinforcing cyber-security and managing cyber-attacks in medical laboratories

- Six Sigma in laboratory medicine: the unfinished symphony

- Navigating complexities in vitamin D and cardiovascular health: a call for comprehensive analysis

- Simplified preanalytical laboratory procedures for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in patients treated with high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) and glucarpidase

- New generation of Abbott enzyme assays: imprecision, methods comparison, and impact on patients’ results

- Correction of negative-interference from calcium dobesilate in the Roche sarcosine oxidase creatinine assay using CuO

- Two cases of MTHFR C677T polymorphism typing failure by Taqman system due to MTHFR 679 GA heterozygous mutation

- A falsely elevated blood alcohol concentration (BAC) related to an intravenous administration of phenytoin sodium