An ultrasensitive DNA-enhanced amplification method for detecting cfDNA drug-resistant mutations in non-small cell lung cancer with selective FEN-assisted degradation of dominant somatic fragments

Abstract

Objectives

Blood cell-free DNA (cfDNA) can be a new reliable tool for detecting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. However, the currently reported cfDNA assays have a limited role in detecting drug-resistant mutations due to their deficiencies in sensitivity, stability, or mutation detection rate.

Methods

We developed an Archaeoglobus fulgidus-derived flap endonuclease (Afu FEN)-based DNA-enhanced amplification system of mutated cfDNA by designing a pair of hairpin probes to anneal with wild-type cfDNA to form two 5′-flaps, allowing for the specific cleavage of wild-type cfDNA by Afu FEN. When the dominant wild-type somatic cfDNA fragments were cleaved by structure-recognition-specific Afu FEN, the proportion of mutated cfDNA in the reaction system was greatly enriched. As the amount of mutated cfDNA in the system was further increased by PCR amplification, the mutation status could be easily detected through first-generation sequencing.

Results

In a mixture of synthetic wild-type and T790M EGFR DNA fragments, our new assay still could detect T790M mutation at the fg level with remarkably high sensitivity. We also tested its performance in detecting low variant allele frequency (VAF) mutations in clinical samples from NSCLC patients. The plasma cfDNA samples with low VAF (0.1 and 0.5 %) could be easily detected by DNA-enhanced amplification.

Conclusions

This system with enhanced amplification of mutated cfDNA is an effective tool used for the early screening and individualized targeted therapy of NSCLC by providing a rapid, sensitive, and economical way for the detection of drug-resistant mutations in tumors.

Introduction

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations are proving to be an increasingly important molecular subtype in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [1]. Currently, targeted therapy is the preferred standard treatment for NSCLC patients [2, 3]. EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) are the first-line treatment that improves survival and life quality. However, drug resistance to these kinase inhibitors eventually emerges over a period of time after initial treatment [4, 5]. In patients with EGFR mutations, the most common pattern of acquired resistance is a point mutation in the active region of EGFR, where the amino acid at position 790 is converted from threonine to methionine (T790M mutation), which induces a conformational change in the ATP-binding pocket of the EGFR kinase domain and inhibits EGFR-TKI binding [6]. T790M mutations are reported to account for 50–60 % of resistance to first- and next-generation TKIs [7]. Therefore, NSCLC patients need to be tested for EGFR gene mutation status prior to targeted therapy, and the targeted drugs should be selected accordingly for individual treatment [8]. In addition, EGFR mutation testing should be performed periodically during the treatment process to allow for timely adjustment of the treatment regimen in patients who have developed TKI resistance.

So far, tissue-based testing remains the first choice for clinical detection of EGFR mutations, but it cannot overcome the spatial heterogeneity of genetics. In addition, most NSCLC patients are already in intermediate or advanced stages when they are diagnosed, and the opportunity to obtain tumor tissue by surgical resection is missed, which hinders the application of EGFR gene mutation detection in clinical practice [9]. Studies have shown that the mutational information contained in blood cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is highly consistent with that of tumor tissue [10], [11], [12]. Therefore, blood cfDNA has emerged as an alternative to address the above limitations in NSCLC patients [13, 14].

At present, there is no universally recognized “gold standard” technology for detecting mutated EGFR gene in cfDNA. Methods for detecting cfDNA gene mutation mainly include next-generation sequencing (NGS), droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), amplification refractory mutation system PCR (ARMS PCR), loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), high-resolution melting analysis (HRMA), and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI TOF-MS) [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. These detection methods are based on different principles and have their own strengths and weaknesses. Compared to the insensitivity of first-generation sequencing technology, NGS offers high detection throughput and comprehensive coverage of variant types but with complex experimental process, high detection cost, long reporting period, and relatively low sensitivity. Besides, the detection sensitivity of the existing PCR techniques mentioned above is still insufficient. These detecting methods are complex in operation, require accurate quantitative interpretation of fluorescence signals, and/or require special equipment with high detection cost, which make EGFR gene mutation detection become unavailable and/or unaffordable in areas with scarce medical resources. Therefore, there is an urgent need for accurate and cost-effective EGFR gene mutation detection methods so that more NSCLC patients can benefit from targeted therapy.

A major challenge in detecting blood cfDNA is the low mutational levels of tumor target genes, diffused in a large excess of wild-type somatic DNA sequences in blood that will interfere with mutation detection in cfDNA [21]. So, detecting the mutated cfDNA is considered key to EGFR mutation detection methods. In our present study, we developed an enhanced amplification assay for mutated cfDNA, focusing on the Archaeoglobus fulgidus-derived flap endonuclease (Afu FEN) [22, 23]. This new tool utilizes its structure-specific recognition and cleavage properties to selectively cleave the dominant somatic EGFR DNA fragments, thus increasing the proportion of mutated fragments to maximize the detection rate of EGFR mutations. As a member of the Rad2 family of nucleases, FEN is a multifunctional, structure-specific endonuclease that plays an important role in DNA replication and repair [24]. Herein, we designed a system to detect T790M (ACG → ATG) mutation in the EGFR gene. Specifically, a pair of oligonucleotide probes with hairpin structures was synthesized and annealed to the wild-type EGFR bases of the specified site (positive strand: C, negative strand: G) to form a DNA complex with two 5′-flaps, and then FEN was targeted to cleave the 3′-end of the corresponding bases of the wild-type EGFR double-stranded DNA. Subsequently, a DNA-enhanced PCR of mutated EGFR gene was performed, followed by PCR product purification for first-generation sequencing to analyze the mutation status of T790. This strategy could detect cfDNA at the picogram level by utilizing selective FEN-assisted degradation of dominant somatic DNA fragments. With high nuclease activity and strong signal amplification capacity, it is a promising tool for clinical laboratories to construct convenient and efficient amplification strategy for drug-resistant mutations detection.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

The flap endonuclease 1 gene from the genomic DNA of A. fulgidus was synthesized with the additional sequence encoding a hexahistidine tag at the 3′ end by BGI BioTech (China) (GenBank ID: 1483479). The synthetic DNA product flanked by NcoI and BamHI restriction sites was inserted into the NcoI/BamHI sites of the expression vector pRSFDuet-1 (Novagen, USA).

FEN overexpression and purification

The expression plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) for protein overexpression and purification. The cells were grown to an optical density of 0.6–0.8 at 600 nm in Luria-Bertani medium, and protein was induced by adding 0.1 mM of isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG). After incubation at 20 °C for 16 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and suspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 500 mM NaCl. The cells were lysed by sonication. After removal of cell debris by centrifugation (10,000×g, 30 min, 4 °C), the supernatant was heat-treated at 80 °C for 30 min and immediately cooled on ice, and then centrifuged (10,000×g, 30 min, 4 °C). Polyethylenimine was added slowly to the supernatant to a final concentration of 0.3 %. After stirring for 1 h, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000×g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was adjusted to 70 % saturation with (NH4)2SO4, stirring while adding for 1 h, letting it stand still for 1 h, and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 30 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in the above lysis buffer and dialyzed against the same buffer. The dialyzed material was then centrifuged (10,000×g, 30 min, 4 °C), the supernatant was loaded onto a Ni-Sepharose chelating column (1 mL; Qiagen) equilibrated with lysis buffer. The column was washed with lysis buffer, and bound proteins were eluted with an imidazole gradient (0–250 mM) in lysis buffer. Target protein fractions were pooled and subsequently loaded on a HiTrap desalting column (5 mL; GE Healthcare) equilibrated with desalting buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, and 20 % glycerol. All purification steps were carried out at 4 °C. The purified proteins were stored at −80 °C. Protein concentrations were determined by the BCA method with bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Beyotime Biotech, China) as the standard.

Oligonucleotides

The forward primer (EGFR FP) and reverse primer (EGFR RP) were employed to amplify a 174-base pair EGFR wild-type or T790M DNA fragments, respectively. Primers T790M forward primer 1, T790M forward primer 2, and EGFR RP were used to prepare T790M fragments. Probe 1 (5′-GGCAGCCGAAGGGCATGAGCTGCGGCCGCGCTGAGTGCCTTTTGGCACTCAGCGCGGCT-3′) (the sequence complementary paired with the positive-stranded template of the wild-type EGFR gene is underlined) and probe 2 (5′-CCTCCACCGTGCAGCTCATCACCGCCTGGACCTGGCGGTTTTCCGCCAGGTCCAGGCGT-3′) (the sequence complementary paired with the negative-stranded template of the wild-type EGFR gene is underlined) were annealed to the positive-strand and negative-strand of the wild-type EGFR gene to form two 5′-flap structures, respectively. The oligonucleotides were all synthesized at Sangon BioTech (Shanghai, China) (Supplemental Material, Table S1).

Reagents

Tris-base, sodium chloride, glycerol, magnesium chloride, potassium chloride, bovine serum albumin, ammonium sulphate and IPTG were purchased from Sangon BioTech. Polyethylenimine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company.β-Mercaptoethanol (β-Me) used for flap endonuclease assay were purchased from Merck. 2 × Phanta Flash Master Mix used in EGFR DNA fragment amplification reaction was purchased from Vazyme. 2 × Taq Polymerase Mix was gifted by Meilun.

Flap endonuclease assay

The flap endonuclease assay was carried out in a PCR instrument with a 10-μL reaction mixture consisting of hairpin probe 1 (10 pmol or indicated concentration), hairpin probe 2 (10 pmol or indicated concentration), wild-type EGFR DNA fragment (120 fg), EGFR T790M DNA fragment (12 fg), Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 (50 mM), MgCl2 (7.5 mM), KCl (30 mM),β-Me (0.5 mM), and BSA (50 μg/mL). Before FEN enzyme was added, the mixture was incubated at 95 °C for 5 min and annealed to 65 °C or indicated temperature. Then, FEN was added or not, and the reaction was incubated at 65 °C or indicated temperature for 20 min or longer. Under the indicated conditions, FEN was added directly into the reaction system to withstand the temperature of DNA template denaturation.

T790M DNA enhanced amplification

After the flap endonuclease assay, the reaction products were added to a 50-μL PCR amplification system in the presence of 1 × DNA Polymerase Mix, EGFR FP (20 pmol), and EGFR RP (20 pmol). The PCR reaction was subjected to a denaturation step (94 °C for 30 s), 30 cycles of a denaturation step (94 °C for 20 s), a hybridization step (55 °C for 20 s), and an extension step (72 °C for 20 s). At the end of PCR cycling, the reaction was extended for 5 min at 72 °C and lowered to 4 °C hold. Next, the samples were subjected to electrophoresis in 2 % agarose gel in 0.5 × TAE buffer. The gel was exposed to a gel imager (GE Healthcare) and recovered by DNA purification kit (Genfine BioTech). Then, the purified PCR products were confirmed by first-generation sequencing (Sangon BioTech).

T790M detection assay in clinical samples

Plasma cfDNA was prepared from sodium citrate-anticoagulated plasma samples using Apolstle Minimax High Effiency cfDNA Isolation Kit according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. First, diluted cfDNA was used as the template for amplification by the high-fidelity DNA polymerase, and the amplified product was purified by gel electrophoresis. Then, the purified cfDNA was gradient diluted to participate in flap endonuclease assay, in which cfDNA cleavage by FEN was performed as described above except that cfDNA was added to the reaction mixture to replace the wild-type EGFR DNA fragment and EGFR T790M DNA fragment. Finally, T790M DNA-enhanced amplification was conducted as described above, followed by first-generation sequencing (Sangon BioTech). Meanwhile, as a control, cfDNA samples collected were sequenced by NGS to identify the mutation status of the EGFR gene. All samples were sequenced using Illumina Miseq in a 150-bp paired-end pattern. Adapter sequence and low-quality region were removed with Trimmomatic (version 0.38), and the clean reads were aligned to the hg19 reference genomes using ‘bwa mem’ (version 0.7.17). BAM files were realigned and base quality score were conducted using GATK (version 4.1). Potential mutations were identified through analysis of data across targeted regions of interest using SAMtools mpileup. Mutations were annotated using ANNOVAR and true mutations were verified using IGV (version 2.3.34).

Results

Principle of the mutated DNA-enhanced amplification system

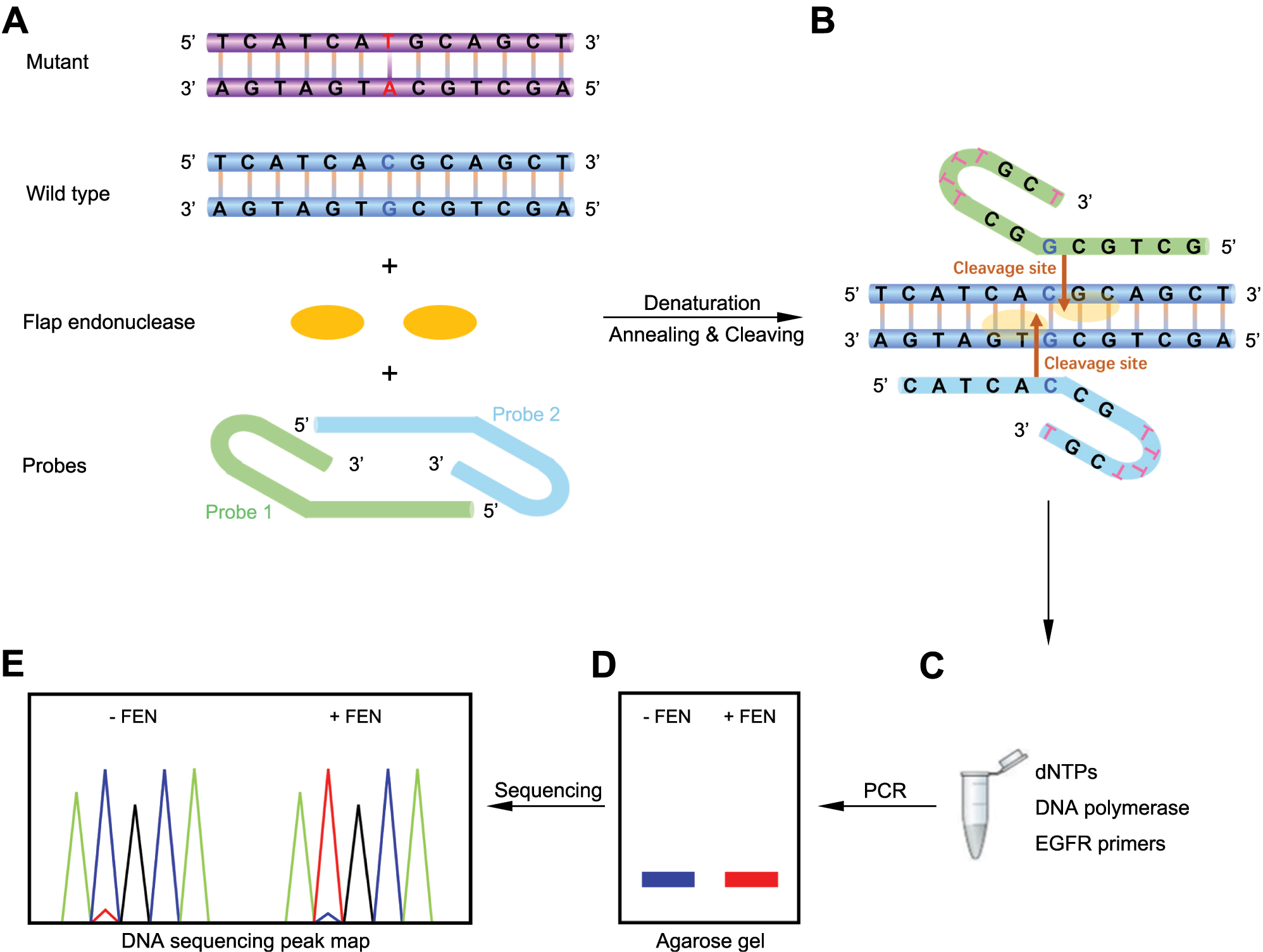

The overall experimental procedures of the EGFR T790M DNA-enhanced amplification detection assay are depicted in Figure 1. To selectively degrade the dominant wild-type DNA and increase the proportion of T790M DNA in the EGFR DNA mixture, we constructed a signal amplification system based on A. fulgidus flap endonuclease (Afu FEN). First, according to the DNA base sequence of wild-type T790, a pair of hairpin probes were designed to complement the base of a positive and negative strand of wild-type T790 duplex DNA, respectively, thus form the specific structure that FEN can cleavage. As a target DNA, wild-type T790 dsDNA fragment was denatured at 95 °C for 5 min to completely separate the double strand. Probe 1 (green) and probe 2 (blue) were hybridized to each of the two strands in the target DNA by annealing from 95 to 65 °C, so as to capture both strands of the separated target DNA (Figure 1A and B). The captured DNA complex produced two 5′-flap structures, which were specifically recognized and cleaved by Afu FEN at the specified sites (indicated by orange arrows). Next, FEN was added to the reaction system to cleave the 5′ flap downstream of the first base pair between the probe and the target DNA. Theoretically, FEN should be added to the reaction system after annealing the probe and target DNA, so that FEN would not be deprived of activity by denaturing at 95 °C; however, we also tried to add FEN to the reaction system at the beginning of the denaturation step and found that the activity of FEN was not significantly affected.

Scheme for DNA-enhanced amplification-based detection of EGFR T790M mutation using selective FEN-assisted degradation of dominant somatic DNA fragments. (A) The main elements of the standard cleavage reaction mixture include EGFR wild-type T790 (blue) and mutated T790M (purple) DNA fragments, Archaeoglobus fulgidus flap endonuclease (Afu FEN) (orange), and a pair of 59 nt hairpin probes (green for probe 1 and light blue for probe 2). (B) Probe 1 and probe 2 form two 5′-flap structures by denaturation and annealing to EGFR wild-type T790 target DNA. Then, FEN specifically recognizes the structure and cleaves the T790 target DNA strands to release the flap fragments. The cleavage sites are indicated by orange arrows. (C) DNA-enhanced amplification reaction by PCR. Template: cleavage products by FEN; primers: EGFR FP and EGFR RP. (D) Agarose gel electrophoresis and purification of the amplified 174 bp DNA products. (E) First-generation sequencing chromatograms of the purified products.

After FEN cleavage of wild-type EGFR DNA, the mutated T790M DNA signal amplification reaction was performed by PCR, in which the product from the first reaction system was added as a template and then the amplification reaction was conducted with a pair of EGFR primers (Figure 1C). Here, since the amplification product is only 174 bp long, both high-fidelity and Taq DNA polymerases can be selected in the amplification system, which will not affect the DNA amplification. When PCR was completed, the amplification products were analyzed and purified on an agarose gel for first-generation sequencing (Figure 1D and E), which showed that, in the presence of FEN in the reaction system during the first step, the sequencing profile predominantly showed the ATG bases encoding methionine at position 790. In contrast, the negative control, which lacked FEN, showed the vast majority of the ACG bases encoding threonine. Thus, our method can easily detect the T base that may not be detected otherwise through first-generation sequencing. As a result, a highly sensitive strategy was achieved for the detection of EGFR T790M DNA.

Feasibility of the DNA-enhanced amplification system for detecting EGFR T790M

To investigate the applicability of the DNA-enhanced amplification system, the mutated EGFR T790M DNA fragments were spiked into wild-type EGFR DNA fragments at different ratios. Afu FEN protein was successfully expressed and purified (Supplementary Material, Figure S1). We first prepared short fragments of wild-type 790T and mutated 790M EGFR DNA by site-directed mutagenesis PCR (Supplementary Material, Figure S2), respectively. These fragments were 174 bp in length, and their sequences were shown in Figure 2A. According to the assay procedure, we mixed different ratios of the two DNA fragments, and then sequentially performed the cleavage reaction of FEN and the PCR-enhanced amplification reaction (Figure 2B). When the ratio of 790T to 790M was 10:1 (120 fg:12 fg), it was clearly seen on agarose gel electrophoresis that the amount of the reaction product was lower in the presence of FEN compared to its absence, indicating that FEN cleaved 790T, leading to a decrease in the amount of 790T template and consequently a reduction in the amount of product (Figure 2C). The products after electrophoresis were purified and subjected to first-generation sequencing. The sequencing results showed that the coding base of the amino acid at position 790 in the amplification product containing FEN was ATG, of which a small proportion of C base in the ACG was visible on the first-generation sequencing chromatogram. In contrast, the coding base of the amino acid at position 790 in the amplification product without FEN was ACG. However, the T base of ATG was not visible on the sequencing chromatogram (Figure 2D). This method can detect the mutant T base with initial frequency as low as 0.01 % (Supplementary Material, Figure S3). Therefore, the DNA-enhanced amplification assay involving the use of Afu FEN showed good performance in amplifying and detecting the signal of low-abundance EGFR T790M DNA.

Construction of an enhanced amplification assay for EGFR T790M DNA based on flap endonuclease (FEN) cleavage. (A) DNA sequences of human wild-type EGFR fragment (790T) and T790M mutated fragment (790M), both 174 bp in length. (B) Schematic representation of the Afu FEN-specific cleavage reaction of the EGFR WT DNA fragments. (C) Agarose gel electrophoresis of 174-bp PCR reaction products mediated by FEN cleavage. 790T (120 fg) and 790M DNA fragments (12 fg) were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min and cooled down to 65 °C with probe 1 and probe 2 in the standard flap endonuclease cleavage assay mixture. After the probes were annealed to 790T, FEN was added (lane 2) or not (lane 1) into the standard reaction mixture at 65 °C for 20 min. Later, the standard reaction mixture was subjected to enhanced amplification by PCR. Samples were then resolved by electrophoresis in 2 % agarose gel, exposed to a gel imager, and recovered. M, DNA markers, 5,000 bp, 3,000 bp, 2,000 bp, 1,000 bp, 750 bp, 500 bp, 250 bp and 100 bp in length (from top to bottom). (D) First-generation sequencing of the174-bp DNA purified from the gel was performed to detect the mutated base encoding T790M (C → T). 1, no FEN in the reaction system; 2, 20 ng of FEN per reaction system. The mutated DNA base site ‘X’ to be detected is indicated by red arrows. The chromatographic peaks in different colors represent different nucleotides (blue for C, red for T, black for G, and green for A). Each experiment was repeated three times.

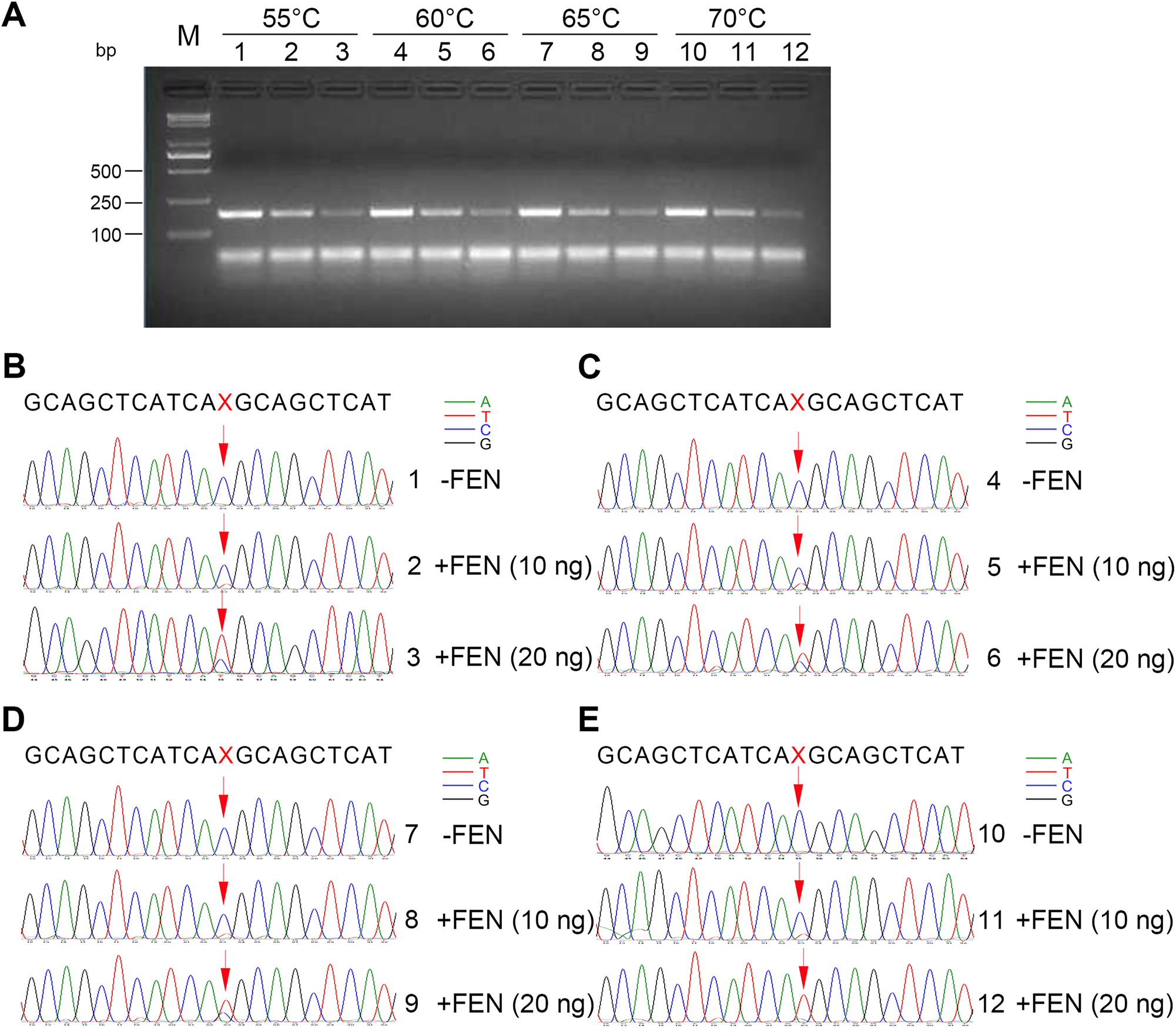

Optimization of the DNA-enhanced amplification assay for EGFR T790M DNA based on FEN cleavage

The cleavage efficiency of FEN in the flap endonuclease assay is important for the degradation of the dominant somatic DNA fragments. Therefore, the flap endonuclease assay was performed at 55 °C, 60 °C, 65 °C, and 70 °C, and the enhanced amplification results are shown in Figure 3A. At these four temperatures, the amount of all the final 174-bp DNA amplification products gradually decreased as the working concentration of FEN increased, suggesting that FEN degraded the wild-type dominant DNA templates. The amplification products were subsequently sequenced and the results showed that the addition of FEN enabled the detection of T bases encoding methionine. A significant increase in the proportion of distinct T base (red) sequencing chromatogram was observed when the working concentration of FEN reached 20 ng per reaction, far exceeding the proportion of C base (blue) (Figure 4B–E). The FEN enzyme was active at 55–70 °C, suggesting that FEN-assisted dominant somatic DNA fragments degradation system had a wide range of reaction temperatures, which provided a more relaxing environment for probe design and selection. To achieve faster FEN-mediated degradation of wild-type DNA, the flap endonuclease assay was performed at 60 and 65 °C, respectively, for 10 min. T bases were observed in the final first-generation sequencing results, but not at a higher percentage than that of C bases. This may be due to insufficient cleavage of the FEN within 10 min. When FEN cleavage reaction was conducted at 65 °C, the proportion of T bases in the final sequencing results was still slightly higher than that at 60 °C (Supplementary Material, Figure S4). Considering the specificity of the flap endonuclease reaction and the annealing efficiency of the probes to the templates, we performed the FEN cleavage reaction at 65 °C.

Effects of temperature on the cleavage of dominant wild-type EGFR DNA fragments. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of the 174-bp PCR reaction products mediated by FEN cleavage at 55 °C, 60 °C, 65 °C, and 70 °C, respectively. 790T (120 fg) and 790M DNA fragments (12 fg) were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min and cooled down to indicated temperatures with probe 1 and probe 2 in the standard flap endonuclease cleavage assay mixture. After the probes were annealed to 790T, FEN was added or not into the standard reaction mixture at indicated temperatures for 20 min. Later, the standard reaction mixture was subjected to enhanced amplification by PCR. Samples were then resolved by electrophoresis in 2 % agarose gel, exposed to a gel imager, and purified. Lanes 1, 2, and 3: FEN cleavage reactions were incubated at 55 °C for 20 min. Lanes 4, 5, and 6: FEN cleavage reactions were incubated at 60 °C for 20 min. Lanes 7, 8, and 9: FEN cleavage reactions were incubated at 65 °C for 20 min. Lanes 10, 11, and 12: FEN cleavage reactions were incubated at 70 °C for 20 min. Lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10: no FEN. Lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11: 10 ng FEN per reaction system. Lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12: 20 ng FEN per reaction system. M: DNA markers, 5,000 bp, 3,000 bp, 2,000 bp, 1,000 bp, 750 bp, 500 bp, 250 bp, and 100 bp in length (from top to bottom). (B–E) First-generation sequencing was performed on 174-bp DNA purified from the gel to detect mutated bases (C → T) encoding T790M mediated by FEN cleavage at 55 °C (B), 60 °C (C), 65 °C (D), and 70 °C (E), respectively. The mutated DNA base site ‘X’ to be detected is indicated by red arrows. The chromatographic peaks in different colors represent different nucleotides (blue for C, red for T, black for G, and green for A). Each experiment was repeated three times.

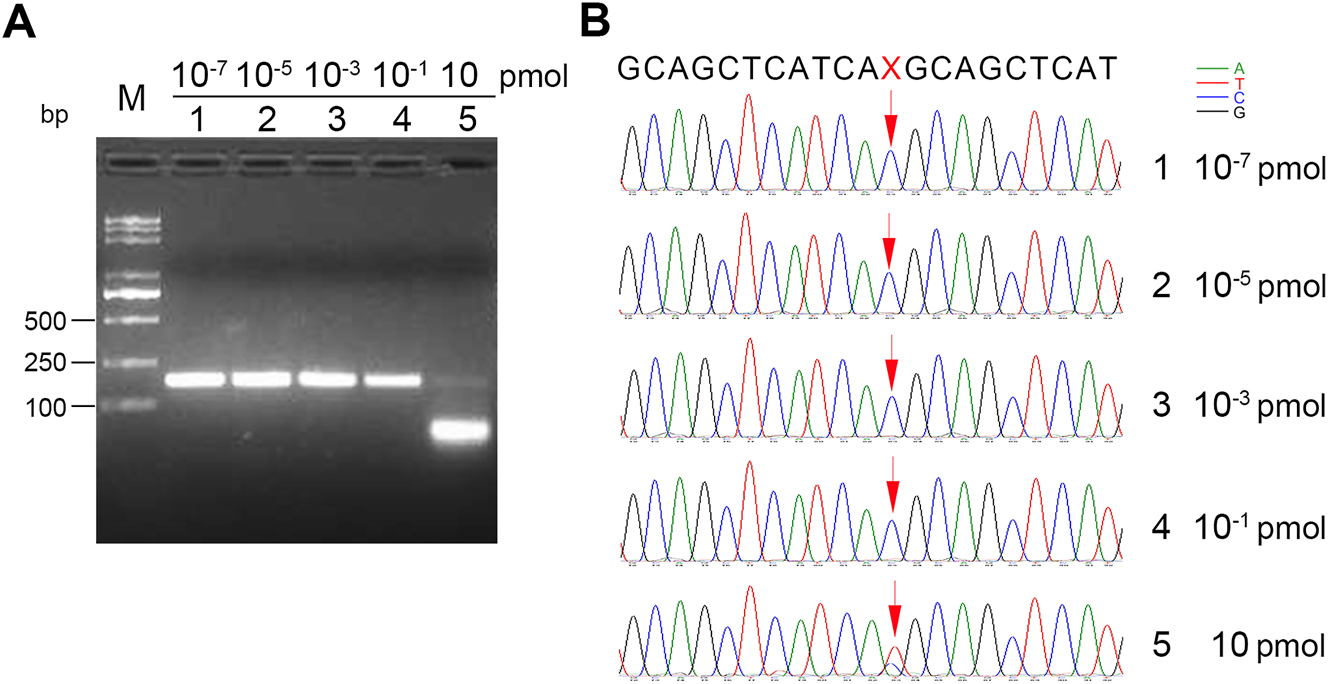

Effects of probe/template ratio on the cleavage of dominant wild-type EGFR DNA fragments. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of 174-bp PCR reaction products mediated by FEN cleavage at 65 °C for 20 min. 790T (10−6 pmol) and 790M DNA fragments (10−7 pmol) were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min and cooled down to 65 °C with indicated concentrations of probe 1 and probe 2 in the standard flap endonuclease cleavage assay mixture. After annealing, FEN (20 ng) was added into the standard reaction mixture at 65 °C for 20 min. Later, the reaction mixture was subjected to enhanced amplification by PCR. Samples were then resolved by electrophoresis in 2 % agarose gel, exposed to a gel imager, and purified. The working concentrations of probe1 and probe 2 were 10−7 pmol (lane 1), 10−5 pmol (lane 2), 10−3 pmol (lane 3), 10−1 pmol (lane 4), and 10 pmol (lane 5). M: DNA markers, 5,000 bp, 3,000 bp, 2,000 bp, 1,000 bp, 750 bp, 500 bp, 250 bp, and 100 bp in length (from top to bottom). (B) First-generation sequencing was performed on 174-bp DNA purified from the gel to detect mutated bases (C → T) encoding T790M mediated by FEN cleavage. 1–5 correspond to the sequencing results of lanes 1–5 in (A). The mutated DNA base site ‘X’ to be detected is indicated by red arrows. The chromatographic peaks in different colors represent different nucleotides (blue for C, red for T, black for G, and green for A). Each experiment was repeated three times.

In the above reaction system, the molar concentration of wild-type 790T was 10−6 pmol. To explore the impact of probe/template molar ratio on the degradation reaction of wild-type dominant EGFR DNA fragments, a series of probes (probe 1 and probe 2) with molar concentration gradients were added to the reaction system. The working concentrations of the probes were 10−7 pmol, 10−5 pmol, 10−3 pmol, 10−1 pmol, and 10 pmol. Accordingly, the mole ratios of the probe to the template were 0.1, 10, 103, 105, and 107. The sequencing results showed that at a probe concentration of 10−1 pmol, a small proportion of T base became detectable; however, when the probe concentration reached 10 pmol, T base became the dominant base (Figure 4). Therefore, an excess probe/template molar ratio ensures the formation of stable 5′-flap structures, which facilitates efficient degradation of the template DNA.

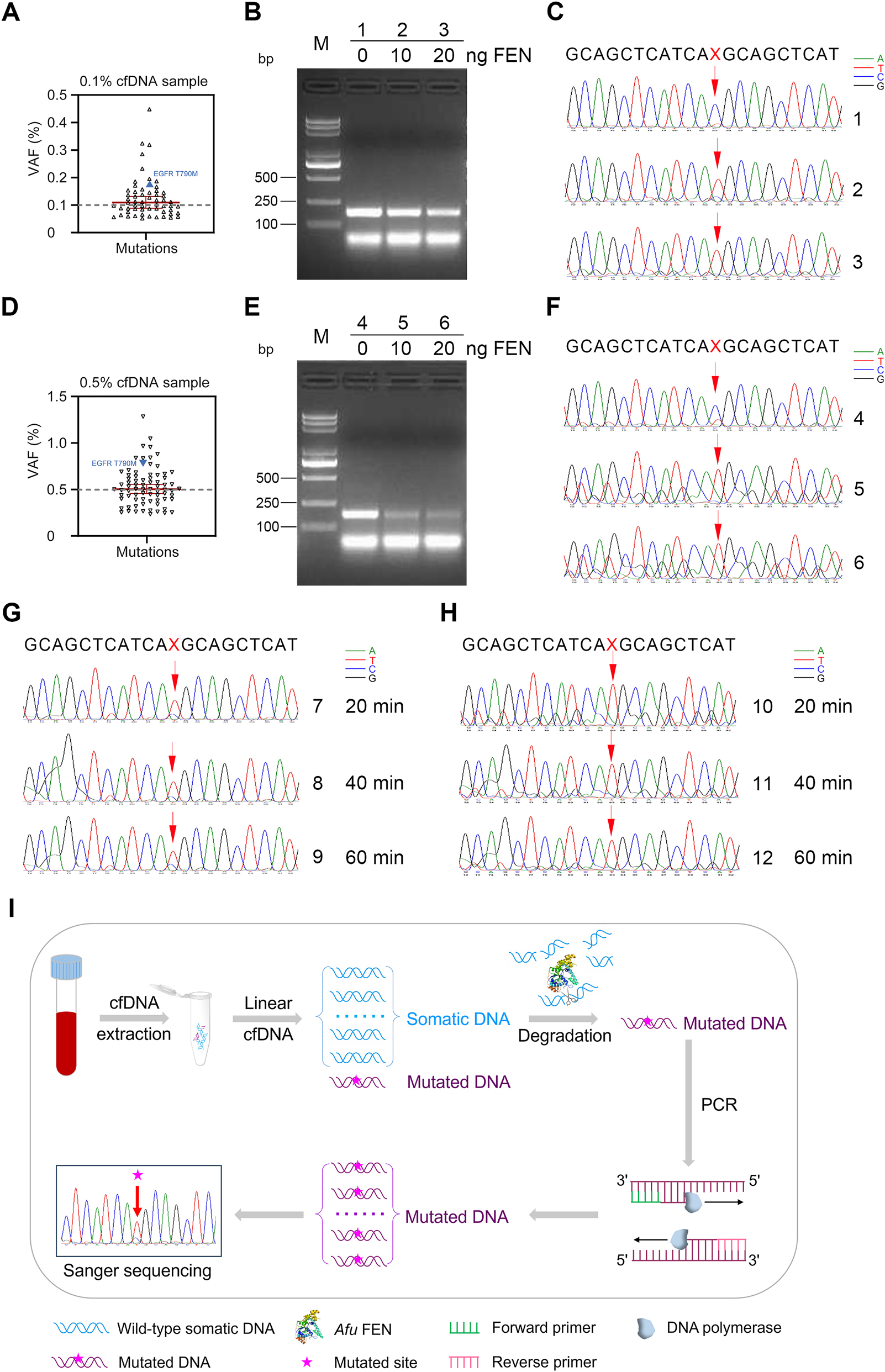

Performance of the DNA-enhanced amplification system in detecting T790M mutation in clinical samples

To further investigate the potential clinical value of our newly-developed assay, 50 plasma cfDNA samples from NSCLC patients were validated using the enhanced amplification system. Further, we selected two typical cfDNA reference materials for detailed analysis. The two cfDNAs are hereinafter referred to as specimen #1 and specimen #2, respectively, at a concentration of 5 ng/μL, in which the variant allele fraction (VAF) of specimen #1 was 0.1 % and VAF of specimen #2 was 0.5 %. The VAFs of EGFR T790M mutations were both marked in Figure 5A and D, respectively. Next, we used our method presented here to enrich the mutated T790M DNA for each of the two cfDNAs. First, we amplified and purified these two cfDNAs by simple PCR with EGFR FP and EGFR RP primers, respectively, to obtain the amplified cfDNAs of specimen #1 and specimen #2 at a concentration of 18 ng/μL for the convenience of subsequent operations. Then, 100-, 1,000-, and 10,000-fold dilutions of the concentrations of these two amplified cfDNAs for specimen #1 and specimen #2 were performed to participate in the FEN cleavage reaction as well as the subsequent enhancement amplification reaction.

Detection of EGFR T790M DNA from clinical cfDNA reference materials with different variant allele fractions (VAFs). The mutation VAFs (measured by NGS) of cfDNAs from specimen #1 and specimen #2 are shown in (A) and (D), respectively. VAFs of T790M are labeled as blue triangles. (B–C, E–F) detecting mutated T790M of cfDNAs from specimen #1 and specimen #2 by the DNA-enhanced amplification method. cfDNA (3.6 pg) was incubated at 95 °C for 5 min and annealed to 65 °C with probe 1 and probe 2 in the standard flap endonuclease cleavage assay mixture. After annealing, FEN was added or not into the standard reaction mixture at 65 °C for 20 min, 40 min, 60 min, and 2 h, respectively. Later, the standard reaction mixture was subjected to enhanced amplification by PCR. Samples were then resolved by electrophoresis in 2 % agarose gel, exposed to a gel imager, and purified. First-generation sequencing was performed on the purified DNA. (B–C) DNA enhanced amplification electrophoresis after 2 h of FEN degradation of dominant somatic DNA (left) and first-generation sequencing chromatogram (right) of cfDNA at VAF of 0.1 % from specimen #1. (E–F) DNA enhanced amplification electrophoresis after 2 h of FEN degradation of dominant somatic DNA (left) and first-generation sequencing chromatogram (right) of cfDNA at VAF of 0.5 % from specimen #2. 1 and 4: no FEN in the detection system. 2 and 5: 10 ng of FEN per reaction system. 3 and 6: 20 ng of FEN per reaction system. M, DNA markers, 5,000 bp, 3,000 bp, 2,000 bp, 1,000 bp, 750 bp, 500 bp, 250 bp, and 100 bp in length (from top to bottom). The mutated DNA base site ‘X’ to be detected is indicated by red arrows. The chromatographic peaks in different colors represent different nucleotides (blue for C, red for T, black for G, and green for A). The degradation of dominant somatic DNA by FEN (20 ng) in specimen #1 (G) and specimen #2 (H) were performed at 65 °C for 20 min (7 and 10), 40 min (8 and 11), and 60 min (9 and 12), respectively. (I) Schematic illustration of degradation of clinically dominant wild-type somatic DNA by Afu FEN and amplification reaction of mutated DNA. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Figure 5B and C represent the cfDNA results of specimen #1, where ‘1’ is the result without FEN, and ‘2’ and ‘3’ are the results with different amounts of FEN. The first-generation sequencing chromatogram showed that the original C base was flipped to T base in ‘2’ and ‘3’ after the addition of FEN. Similarly, Figure 5E and F represent the cfDNA results of specimen #2, where ‘4’ is the result without FEN and ‘5’ and ‘6’ are the results with different amounts of FEN. The first-generation sequencing chromatogram showed that the original C base was converted to a T base in the presence of FEN (Figure 5C and F). The FEN cleavage reaction was carried out at 65 °C for 20 min to 2 h. The effective cleavage of somatic DNA fragments was achieved after 20 min when FEN was added to the reaction system (Figure 5G and H). This allows for the easy detection of a small proportion of EGFR T790M mutation in both specimens with high sensitivity, even at levels as low as pg (10,000-fold dilution). Thus, our novel mutated cfDNA enhanced amplification method is indeed a proposed strategy to detect EGFR mutation sites for selective degradation of dominant somatic fragments in NSCLC patients (Figure 5I).

Discussion

cfDNA monitoring can provide valuable information for early cancer diagnosis and prognosis. However, the use of cfDNA for early cancer diagnosis is challenging, in part because cfDNA is released in low amounts in the circulation and can be diluted by DNA from non-tumor cells. The development of new technologies, such as ddPCR or NGS technologies, has greatly improved the sensitivity, specificity, and precision of rare sequence detection [25, 26]. Nevertheless, despite the availability of several EGFR mutation detection methods, monitoring and evaluation of NSCLC treatment remain challenging, especially for EGFR mutation monitoring. Therefore, we developed a novel DNA-enhanced amplification-based assay, which amplifies the signals of low-abundance mutated cfDNAs, in conjunction with the use of Afu FEN. We found that our method was able to detect the mutated base (T) encoded by the EGFR T790M gene, both in pre-prepared samples of wild-type and mutated DNA mixtures and in cfDNAs from plasma of NSCLC patients, even though the reaction system contained mutated cfDNAs at fg to pg levels. Our results showed that direct first-generation sequencing of cfDNA could not accurately detect mutated bases due to interference from the dominant wild-type somatic DNA. In contrast, the mutated base could be easily detected with the assistance of FEN prior to first-generation sequencing, which greatly raises the detection rate of low-abundance mutated cfDNA (down to 0.01 %).

The ingenuity of our method lies mainly in the selection of FEN. We chose Afu FEN from the thermophilic archaea that can tolerate high denaturation and annealing temperatures, with the advantages of high activity and specificity of the cleavage reaction at high temperatures [22, 27, 28]. In addition, our design of DNA probes is also innovative. First, according to previous reports, the sequence at the 3′-terminal of the hairpin probes was determined as T base to achieve the maximum cleavage rate of Afu FEN [22]. Previously, we designed four non-hairpin probes and found that they could also form typical 5′-flap structures. To ensure full annealing at high temperatures and convenience of subsequent experiments, we selected the double hairpin DNA probes. Considering that the probe-target DNA annealing complex still need to undergo flap endonuclease reaction at a high temperature up to 65 °C, we finally selected the 59-nt hairpin probes as the reaction substrates. Compared with ddPCR techniques, our newly established assay has the advantage of detecting early low-abundance NSCLC mutations without requiring specialized PCR instruments and fluorescence reading software and therefore is more applicable in clinical laboratories. In recent years, several new assays have been developed for the detection of mutated cfDNA (Table 1). One of them is the One-PrimER Amplification (OPERA) system, which is designed to detect short and rare cfDNA [29]. Its main principle is to design a primer with a blocker at its 3′-end. The blocking function is removed only when the primer is paired with the template DNA. Then, the primer will be extended and amplified by the introduction of APO-enchant polymerase. The amplified primer is ligated to a single-strand DNA connector, which is then amplified into double-stranded DNA for subsequent NGS. OPERA has been shown to be effective in detecting mutations in rare and highly fragmented DNA with low error rate. NGS technique, although capable of obtaining all the genetic sequence information, is not an ideal tool for individuals with financial constraints or patients requiring long-term real-time monitoring of mutations at known loci due to the high cost and extensive experimentation required. A recent alternative method, based on deoxyribonuclease I (DNase) guided by single-stranded phosphorothioated DNA (sgDNase), has been developed for the excision of wild-type DNA strands. Its main principle is as follows: two single strands of inert DNA are designed to bind to DNases, respectively. When the sequences of wild-type dsDNA and inert DNA are complementary respectively, they will be recognized, bound, and cleaved by DNase, thus enriching the variation abundance of mutated cfDNA in clinical samples [30]. This is consistent with our idea of enriching mutated cfDNA, but with a different enzyme and the principle of degradation of wild-type DNA. Compared to the sgDNase system, our FEN-assisted system has several advantages: first, the wild-type DNA degradation reaction can be carried out in much shorter time (20 min vs. 90 min); second, our system is capable of detecting full-abundance sequencing chromatograms of the mutations (e.g. the abundance of T bases is significantly higher than that of C bases in T790M mutation); third, the FEN-assisted swing arm DNA walker has been constructed to achieve the signal amplification detection of cfDNA [31]. As reported recently, a capture probe was designed using a long swing-arm DNA, while a track was created using MB-labeled hairpin DNA. cfDNA was introduced to unlock a hairpin track to form the DNA duplex walker with the capture probe, allowing it to open up the hairpin track to form a three-base overlapping DNA structure that was recognized and cleaved by FEN. Driven by FEN and high temperatures, the DNA walker began to hybridize with other track DNA and released multiple flaps for electrochemical signal amplification. This detection strategy can detect 0.33 fM cfDNA in 80 min, making it a viable option in liquid biopsy [32]. Compared with DNA walker, our established method utilizes FEN but does not require a gold nanoparticle or electrochemical detection. Instead, it only requires a pair of unlabeled probes. Therefore, it is more practical and simpler to operate in clinical testing.

Listing of recent cfDNA mutation detection methods.

| Detection method | Feature | Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| AFEN-assisted DNA enhanced amplification | Cleavage of wild-type DNA, followed by Sanger sequencing, no fluorescence detection | Requiring PCR and agarose gel purification |

| OPERA system | Favoring the detection of short and rare cfDNA | Unprecise fragment lengths due to the restriction of sonication-shearing techniques |

| NGS | High throughput, comprehensive coverage of mutation types | Long reporting cycles, high costs, high template abundance |

| sgDNase-assisted DNA detection | Cleavage of wild-type DNA, followed by Sanger sequencing, NGS, or fluorescence detection | 90 min-long of wild-type DNA cleavage |

| FEN-assisted swing arm DNA walker | Electrochemical detection of cfDNA by target recycling cascade amplification | Requiring gold nanoparticle devices |

There are limitations in our study, that is, the steps after Afu FEN processing are slightly complicated and time-consuming, such as PCR, agarose gel electrophoresis and purification, and first-generation sequencing. We need to further optimize the type of liquid biopsy for clinical cfDNA assay and strive to omit the steps of agarose gel electrophoresis and purification. At present, for the majority of NSCLC patients with known targeted drug resistance genes in the treatment, this newly-established method can be used to detect early low-abundance mutations to guide drug adjustments. Furthermore, this method can be used to detect mutations at other sites in the EGFR gene, such as L858R in exon 21 [33]. By comprehensively detecting EGFR-mutant status in patients with NSCLC, it is possible to predict the prognosis of advanced-stage patients with EGFR mutations treated with EGFR-TKIs. Thus, this Afu FEN-based DNA-enhanced amplification system of mutated cfDNA demonstrates a non-invasive method for predicting EGFR status, survival prognosis, and associated biological pathways in patients with NSCLC. In addition, it can also be used to detect mutations in other drug-sensitive related genes or gene polymorphisms in a specific, sensitive, rapid and economical way, with broad promising applications. The establishment of this detection system is of great significance for developing evaluation techniques of early tumor diagnosis and treatment. In the future, this method may also be used in urine or other biological fluids as well as in specimens with seriously damaged DNA. Its combination with microfluidic chip technology will further enable realize the high-throughput detection of clinical samples.

Funding source: Beijing Hospital Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: BJ-2020-134

Funding source: National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding

Award Identifier / Grant number: BJ-2022-151

Funding source: Beijing Hospital Nova Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: BJ-2020-083

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 22274108

Funding source: Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities

Award Identifier / Grant number: 3332019120

Acknowledgments

We thank Fei Xiao for his valuable suggestions.

-

Research ethics: This study was performed following the principles of good clinical practice and according to the guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: JZ and MT conceived and designed research. JZ, WH and GS conducted experiments. JZ, YL and HR collected and analyzed data. JZ and MT wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interests.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Grant BJ-2022-151), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 22274108), Beijing Hospital Project (Grant BJ-2020-134), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant 3332019120), and Beijing Hospital Nova Project (No.BJ-2020-083).

-

Data availability: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in this article (and its supplementary information file). Any additional data, if needed, will be made on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

1. Castellanos, E, Feld, E, Horn, L. Driven by mutations: the predictive value of mutation subtype in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:612–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2016.12.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Noor, ZS, Cummings, AL, Johnson, MM, Spiegel, ML, Goldman, JW. Targeted therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2020;41:409–34. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1700994.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Imyanitov, EN, Iyevleva, AG, Levchenko, EV. Molecular testing and targeted therapy for non-small cell lung cancer: current status and perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2021;157:103194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103194.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. He, J, Huang, Z, Han, L, Gong, Y, Xie, C. Mechanisms and management of 3rd-generation EGFR-TKI resistance in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (Review). Int J Oncol 2021;59. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2021.5270.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Wu, SG, Shih, JY. Management of acquired resistance to EGFR TKI-targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer 2018;17:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-018-0777-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Park, J, McDonald, JJ, Petter, RC, Houk, KN. Molecular dynamics analysis of binding of kinase inhibitors to WT EGFR and the T790M mutant. J Chem Theory Comput 2016;12:2066–78. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.5b01221.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Attili, I, Karachaliou, N, Conte, P, Bonanno, L, Rosell, R. Therapeutic approaches for T790M mutation positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2018;18:1021–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737140.2018.1508347.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Johnson, M, Garassino, MC, Mok, T, Mitsudomi, T. Treatment strategies and outcomes for patients with EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer resistant to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors: focus on novel therapies. Lung Cancer 2022;170:41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2022.05.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Rolfo, C, Mack, P, Scagliotti, GV, Aggarwal, C, Arcila, ME, Barlesi, F, et al.. Liquid biopsy for advanced NSCLC: a consensus statement from the international association for the study of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:1647–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2021.06.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. He, G, Chen, Y, Zhu, C, Zhou, J, Xie, X, Fei, R, et al.. Application of plasma circulating cell-free DNA detection to the molecular diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Transl Res 2019;11:1428–45.Search in Google Scholar

11. Yin, JX, Hu, WW, Gu, H, Fang, JM. Combined assay of circulating tumor DNA and protein biomarkers for early noninvasive detection and prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer 2021;12:1258–69. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.49647.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Oellerich, M, Schütz, E, Beck, J, Kanzow, P, Plowman, PN, Weiss, GJ, et al.. Using circulating cell-free DNA to monitor personalized cancer therapy. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2017;54:205–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2017.1299683.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Krug, AK, Enderle, D, Karlovich, C, Priewasser, T, Bentink, S, Spiel, A, et al.. Improved EGFR mutation detection using combined exosomal RNA and circulating tumor DNA in NSCLC patient plasma. Ann Oncol 2018;29:700–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx765.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Liu, HE, Vuppalapaty, M, Wilkerson, C, Renier, C, Chiu, M, Lemaire, C, et al.. Detection of EGFR mutations in cfDNA and CTCs, and comparison to tumor tissue in non-small-cell-lung-cancer (NSCLC) patients. Front Oncol 2020;10:572895. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.572895.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Postel, M, Roosen, A, Laurent-Puig, P, Taly, V, Wang-Renault, SF. Droplet-based digital PCR and next generation sequencing for monitoring circulating tumor DNA: a cancer diagnostic perspective. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2018;18:7–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737159.2018.1400384.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Guo, QM, Wang, L, Yu, WJ, Qiao, LH, Zhao, MN, Hu, XM, et al.. Detection of plasma EGFR mutations in NSCLC patients with a validated ddPCR lung cfDNA assay. J Cancer 2019;10:4341–9. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.31326.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Li, C, He, Q, Liang, H, Cheng, B, Li, J, Xiong, S, et al.. Diagnostic accuracy of droplet digital PCR and amplification refractory mutation system PCR for detecting EGFR mutation in cell-free DNA of lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2020;10:290. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00290.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Horiuchi, S, Saito, Y, Matsui, A, Takahashi, N, Ikeya, T, Hoshi, E, et al.. A novel loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for efficient and robust detection of EGFR mutations. Int J Oncol 2020;56:743–9. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2020.4961.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Fukui, T, Ohe, Y, Tsuta, K, Furuta, K, Sakamoto, H, Takano, T, et al.. Prospective study of the accuracy of EGFR mutational analysis by high-resolution melting analysis in small samples obtained from patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:4751–7. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-07-5207.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Su, KY, Kao, JT, Ho, BC, Chen, HY, Chang, GC, Ho, CC, et al.. Implementation and quality control of lung cancer EGFR genetic testing by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in Taiwan clinical practice. Sci Rep 2016;6:30944. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30944.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Martignano, F. Cell-free DNA: an overview of sample types and isolation procedures. Methods Mol Biol 2019;1909:13–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8973-7_2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Kaiser, MW, Lyamicheva, N, Ma, W, Miller, C, Neri, B, Fors, L, et al.. A comparison of eubacterial and archaeal structure-specific 5′-exonucleases. J Biol Chem 1999;274:21387–94. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.274.30.21387.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Sheng, N, Ma, Y, Wang, J, Zou, B, Zhou, G. Expression and activity assay of recombinant flap endonuclease 1. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2016;32:1433–42. https://doi.org/10.13345/j.cjb.160076.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Wu, Z, Lin, Y, Xu, H, Dai, H, Zhou, M, Tsao, S, et al.. High risk of benzo[α]pyrene-induced lung cancer in E160D FEN1 mutant mice. Mutat Res 2012;731:85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.11.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Olmedillas-López, S, Olivera-Salazar, R, García-Arranz, M, García-Olmo, D. Current and emerging applications of droplet digital PCR in oncology: an updated review. Mol Diagn Ther 2022;26:61–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40291-021-00562-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Chen, M, Zhao, H. Next-generation sequencing in liquid biopsy: cancer screening and early detection. Hum Genomics 2019;13:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-019-0220-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Hosfield, DJ, Frank, G, Weng, Y, Tainer, JA, Shen, B. Newly discovered archaebacterial flap endonucleases show a structure-specific mechanism for DNA substrate binding and catalysis resembling human flap endonuclease-1. J Biol Chem 1998;273:27154–61. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.273.42.27154.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Tian, K, Guo, Y, Zou, B, Wang, L, Zhang, Y, Qi, Z, et al.. DNA and RNA editing without sequence limitation using the flap endonuclease 1 guided by hairpin DNA probes. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;48:e117. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa843.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Wang, L, Zhuang, Y, Yu, Y, Guo, Z, Guo, Q, Qiao, L, et al.. An ultrasensitive method for detecting mutations from short and rare cell-free DNA. Biosens Bioelectron 2023;238:115548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2023.115548.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Chen, W, Xu, H, Dai, S, Wang, J, Yang, Z, Jin, Y, et al.. Detection of low-frequency mutations in clinical samples by increasing mutation abundance via the excision of wild-type sequences. Nat Biomed Eng 2023;7:1602–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-023-01072-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Cheng, X, Bao, Y, Liang, S, Li, B, Liu, Y, Wu, H, et al.. Flap endonuclease 1-assisted DNA walkers for sensitively and specifically sensing ctDNAs. Anal Chem 2021;93:9593–601. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.1c01765.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Wang, D, Zhou, H, Shi, Y, Sun, W. A FEN 1-assisted swing arm DNA walker for electrochemical detection of ctDNA by target recycling cascade amplification. Anal Methods 2022;14:1922–7. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ay00364c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Harrison, PT, Vyse, S, Huang, PH. Rare epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2020;61:167–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.09.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2024-0614).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Blood self-sampling: friend or foe?

- Reviews

- Blood self-sampling devices: innovation, interpretation and implementation in total lab automation

- Salivary fatty acids in humans: a comprehensive literature review

- Opinion Papers

- EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) recommendations for reinforcing cyber-security and managing cyber-attacks in medical laboratories

- Point-of-care testing: state-of-the art and perspectives

- A standard to report biological variation data studies – based on an expert opinion

- Ethical Checklists for Clinical Research Projects and Laboratory Medicine: two tools to evaluate compliance with bioethical principles in different settings

- Guidelines and Recommendations

- Assessment of cardiovascular risk and physical activity: the role of cardiac-specific biomarkers in the general population and athletes

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- Clinical utility of regions of homozygosity (ROH) identified in exome sequencing: when to pursue confirmatory uniparental disomy testing for imprinting disorders?

- An ultrasensitive DNA-enhanced amplification method for detecting cfDNA drug-resistant mutations in non-small cell lung cancer with selective FEN-assisted degradation of dominant somatic fragments

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- The biological variation of insulin resistance markers: data from the European Biological Variation Study (EuBIVAS)

- The surveys on quality indicators for the total testing process in clinical laboratories of Fujian Province in China from 2018 to 2023

- Preservation of urine specimens for metabolic evaluation of recurrent urinary stone formers

- Performance evaluation of a smartphone-based home test for fecal calprotection

- Implications of monoclonal gammopathy and isoelectric focusing pattern 5 on the free light chain kappa diagnostics in cerebrospinal fluid

- Development and validation of a novel 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (C4) liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method and its utility to assess pre-analytical stability

- Establishment of ELISA-comparable moderate and high thresholds for anticardiolipin and anti-β2 glycoprotein I chemiluminescent immunoassays according to the 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria and evaluation of their diagnostic performance

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Capillary blood parameters are gestational age, birthweight, delivery mode and gender dependent in healthy preterm and term infants

- Reference intervals and percentiles for soluble transferrin receptor and sTfR/log ferritin index in healthy children and adolescents

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Detection of serum CC16 by a rapid and ultrasensitive magnetic chemiluminescence immunoassay for lung disease diagnosis

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- The role of functional vitamin D deficiency and low vitamin D reservoirs in relation to cardiovascular health and mortality

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Letters to the Editor

- EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) survey on cybersecurity

- Comment on Lippi et al.: EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) recommendations for reinforcing cyber-security and managing cyber-attacks in medical laboratories

- Six Sigma in laboratory medicine: the unfinished symphony

- Navigating complexities in vitamin D and cardiovascular health: a call for comprehensive analysis

- Simplified preanalytical laboratory procedures for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in patients treated with high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) and glucarpidase

- New generation of Abbott enzyme assays: imprecision, methods comparison, and impact on patients’ results

- Correction of negative-interference from calcium dobesilate in the Roche sarcosine oxidase creatinine assay using CuO

- Two cases of MTHFR C677T polymorphism typing failure by Taqman system due to MTHFR 679 GA heterozygous mutation

- A falsely elevated blood alcohol concentration (BAC) related to an intravenous administration of phenytoin sodium

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Blood self-sampling: friend or foe?

- Reviews

- Blood self-sampling devices: innovation, interpretation and implementation in total lab automation

- Salivary fatty acids in humans: a comprehensive literature review

- Opinion Papers

- EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) recommendations for reinforcing cyber-security and managing cyber-attacks in medical laboratories

- Point-of-care testing: state-of-the art and perspectives

- A standard to report biological variation data studies – based on an expert opinion

- Ethical Checklists for Clinical Research Projects and Laboratory Medicine: two tools to evaluate compliance with bioethical principles in different settings

- Guidelines and Recommendations

- Assessment of cardiovascular risk and physical activity: the role of cardiac-specific biomarkers in the general population and athletes

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- Clinical utility of regions of homozygosity (ROH) identified in exome sequencing: when to pursue confirmatory uniparental disomy testing for imprinting disorders?

- An ultrasensitive DNA-enhanced amplification method for detecting cfDNA drug-resistant mutations in non-small cell lung cancer with selective FEN-assisted degradation of dominant somatic fragments

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- The biological variation of insulin resistance markers: data from the European Biological Variation Study (EuBIVAS)

- The surveys on quality indicators for the total testing process in clinical laboratories of Fujian Province in China from 2018 to 2023

- Preservation of urine specimens for metabolic evaluation of recurrent urinary stone formers

- Performance evaluation of a smartphone-based home test for fecal calprotection

- Implications of monoclonal gammopathy and isoelectric focusing pattern 5 on the free light chain kappa diagnostics in cerebrospinal fluid

- Development and validation of a novel 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (C4) liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method and its utility to assess pre-analytical stability

- Establishment of ELISA-comparable moderate and high thresholds for anticardiolipin and anti-β2 glycoprotein I chemiluminescent immunoassays according to the 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria and evaluation of their diagnostic performance

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Capillary blood parameters are gestational age, birthweight, delivery mode and gender dependent in healthy preterm and term infants

- Reference intervals and percentiles for soluble transferrin receptor and sTfR/log ferritin index in healthy children and adolescents

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Detection of serum CC16 by a rapid and ultrasensitive magnetic chemiluminescence immunoassay for lung disease diagnosis

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- The role of functional vitamin D deficiency and low vitamin D reservoirs in relation to cardiovascular health and mortality

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Letters to the Editor

- EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) survey on cybersecurity

- Comment on Lippi et al.: EFLM Task Force Preparation of Labs for Emergencies (TF-PLE) recommendations for reinforcing cyber-security and managing cyber-attacks in medical laboratories

- Six Sigma in laboratory medicine: the unfinished symphony

- Navigating complexities in vitamin D and cardiovascular health: a call for comprehensive analysis

- Simplified preanalytical laboratory procedures for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in patients treated with high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) and glucarpidase

- New generation of Abbott enzyme assays: imprecision, methods comparison, and impact on patients’ results

- Correction of negative-interference from calcium dobesilate in the Roche sarcosine oxidase creatinine assay using CuO

- Two cases of MTHFR C677T polymorphism typing failure by Taqman system due to MTHFR 679 GA heterozygous mutation

- A falsely elevated blood alcohol concentration (BAC) related to an intravenous administration of phenytoin sodium