A high throughput immuno-affinity mass spectrometry method for detection and quantitation of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein in human saliva and its comparison with RT-PCR, RT-LAMP, and lateral flow rapid antigen test

-

Dan Lane

, Rebecca Allsopp

, Leong Ng

Abstract

Objectives

Many reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) methods exist that can detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA in different matrices. RT-PCR is highly sensitive, although viral RNA may be detected long after active infection has taken place. SARS-CoV-2 proteins have shorter detection windows hence their detection might be more meaningful. Given salivary droplets represent a main source of transmission, we explored the detection of viral RNA and protein using four different detection platforms including SISCAPA peptide immunoaffinity liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (SISCAPA-LC-MS) using polyclonal capture antibodies.

Methods

The SISCAPA-LC MS method was compared to RT-PCR, RT-loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP), and a lateral flow rapid antigen test (RAT) for the detection of virus material in the drool saliva of 102 patients hospitalised after infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cycle thresholds (Ct) of RT-PCR (E gene) were compared to RT-LAMP time-to-positive (TTP) (NE and Orf1a genes), RAT optical densitometry measurements (test line/control line ratio) and to SISCAPA-LC-MS for measurements of viral protein.

Results

SISCAPA-LC-MS showed low sensitivity (37.7 %) but high specificity (89.8 %). RAT showed lower sensitivity (24.5 %) and high specificity (100 %). RT-LAMP had high sensitivity (83.0 %) and specificity (100.0 %). At high initial viral RNA loads (<20 Ct), results obtained using SISCAPA-LC-MS correlated with RT-PCR (R2 0.57, p-value 0.002).

Conclusions

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein in saliva was less frequent than the detection of viral RNA. The SISCAPA-LC-MS method allowed processing of multiple samples in <150 min and was scalable, enabling high throughput.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) will likely remain a global issue for many years [1]. As of July 2023, deaths of more than 6.9 million people due to COVID-19 have been recorded [2]. The most widely employed test used to determine exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). This detects the presence or absence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA (Figure 1). Due to its great sensitivity [3], ease of sample collection, and the wide availability of PCR instrumentation, nasopharyngeal swab RT-PCR has been employed globally for widescale screening of infection [4].

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (top) and reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (bottom) workflows for the amplification and detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid (ss-RNA). For RT-PCR, a sample is inactivated and RNA extracted followed by amplification through successive heating cycles with primers and polymerase. For RT-LAMP, a sample is inactivated, nucleic acid is extracted, and the ss-RNA is amplified by DNA polymerase in a single step with multiple primers, forming amplified products through mediated loop complexes. Both may be detected via fluorescence.

However, although useful for determining whether a person has been exposed to the virus, it is unclear whether RT-PCR allows any meaningful information to be derived regarding infection status [5]. Such tests, that involve amplification of nucleic acid sequences, do not necessarily determine that an active, productive infection has occurred or is underway. RT-PCR tests are extremely sensitive, requiring <100 copies of viral RNA to yield positive results [3]. The results are reported as cycle thresholds (Ct), which are the number of successive amplification cycles required before PCR products become detectable. Ct values are therefore inversely related to the load of viral RNA. Ct values can remain low (i.e. indicating high viral load) in infected individuals irrespective of symptom severity or duration of exposure [6]. One study found 79.2 % of those with initial Ct values of <25 tested positive by RT-PCR 15–30 days after initial testing [7]. A case report noted positive RT-PCR detection in one patient 63 days after symptom onset [8]. Thus, there is no clearly defined role of RT-PCR for disease monitoring or determination of prognosis. RT-PCR based assays are suited for large scale screening of populations to determine whether a person has been exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

RT-loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) shares a similar mechanism to RT-PCR (Figure 1) but can provide results more quickly (∼30 vs. ∼120 min) [9]. RT-LAMP operates with loop-mediators that can propagate amplification at a constant temperature (65 °C) – this reduces the cycling and thus time required for RT-PCR [9]. In addition, RT-LAMP detects larger genomic fragments, which may not persist in patients as long as the shorter RNA fragments used in RT-PCR [10], thus may better correlate to active disease.

Detection and quantitation of viral protein may better indicate the presence and course of active disease. Researchers have demonstrated a shorter detection window for viral proteins when compared to RNA detection [11], implying a shorter half-life for proteins. “Point of care” rapid antigen tests (RAT) were developed to provide fast, at-home diagnosis. These mostly target intact nucleocapsid (NCAP) proteins using a lateral flow immunocapture system (Figure 2; top). However, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) communicated a stop order over concerns of their performance in late 2021 [12]. These concerns were shared by the National Health Service (NHS) of Great Britain [13], since a recent systematic review found an average sensitivity of RATs was 68.9 % (61.8–75.1 %, 95 % CI) [14] which was 11.1 % below the World Health Organisation’s performance standards of >80 % sensitivity.

Rapid antigen test workflow for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 proteins is shown (top), where a sample is loaded onto the device and intact SARS-CoV-2 protein conjugates with antibodies, forming a complex which binds to the test strip. SISCAPA-LC-MS workflow for the capture and detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid proteotypic peptide surrogate (top). Viral proteins are subject to tryptic digestion and nucleocapsid (NCAP) peptides (AYNVTQAFGR, DGIIWVATEGALNTPK and ADETQALPQR) are captured by SISCAPA-high affinity anti-peptide antibodies before LC separation and analysis by mass spectrometry.

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) is a highly sensitive and selective [15] analytical platform amenable to high throughput analysis [16]. LC-MS platforms are available in most large clinical laboratories [17] and are widely used for measurement of a multitude of small molecules ranging from vitamin D [18] to therapeutic drugs [19]. In addition, LC-MS analysis of peptides (as surrogates for proteins) has increasingly been adopted for protein measurement in biological fluids [20, 21]. LC-MS was proposed as an alternative method to RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 detection in mid-2020 [22]. In this work, detection of multiple SARS-CoV-2 peptides derived from the NCAP and spike (S) proteins was achieved using material from nasopharyngeal swabs [22]. Developing from this, an arm of the UK Department of Health and Social Care initiative, Operation Moonshot, utilised stable isotope standards and capture by anti-peptide antibodies (SISCAPA [23]) for peptide enrichment and analysis by LC-MS in nasopharyngeal swabs, achieving 92.4 % sensitivity and 97.4 % specificity when compared to RT-PCR [24]. Other methods using SISCAPA-LC-MS for NCAP detection have also been published, where some have used monoclonal antibodies [25], [26], [27] and others have used polyclonal antibodies [25, 28, 29]. In the context of future pandemic preparation, a capture workflow using polyclonal antibodies may be useful as these can be produced faster and at less cost [30].

SISCAPA-LC-MS has primarily been used in nasopharyngeal swabs, though salivary droplets represent the main source of human-to-human transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 infection [31]. Furthermore, saliva can be collected by non-invasive means and is thus an ideal matrix for screening of virus presence.

Given the usefulness of a test that may differentiate active infections, we sought to explore how common RNA tests compare to protein tests for SARS-CoV-2 detection in saliva.

We report the adaption of the SISCAPA-LC-MS workflow using polyclonal antibodies for drool saliva (Figure 2; bottom) and its comparison with RT-PCR, RT-LAMP and RAT from a cohort of 102 patients hospitalised with COVID-19. Different Ct and time-to-positive (TTP) cut-offs were tested against SISCAPA-LC-MS to examine how RNA tests correlate with protein tests.

Materials and methods

Sample collection, ethics, and demographics

Neat saliva samples were obtained from 102 in-patients with suspected COVID-19. The participants gave informed consent as part of a prior study performed between January and July 2021 in the University Hospitals of Leicester, UK (SARS-CoV-2 RT-LAMP saliva study; REC approval number 20/EE/0212). Saliva sampling was performed at least 30 min after ingestion of meals or drug prescriptions or after teeth brushing. Participants rinsed their mouths with water 10 min before collection, then were asked to drool (without contaminating this with sputum) between 2 and 5 mL of saliva into a plain, sterile 30 mL universal container (Elkay Laboratory Products [UK] Ltd, Basingstoke, UK). The saliva samples were aliquoted and separated for RT-PCR, RT-LAMP, RAT, and SISCAPA-LC-MS experiments. These samples were stored at 4 °C for less than 3 days before RNA extraction and parallel analysis by RT-PCR and RT-LAMP. The saliva samples for RAT and SISCAPA-LC-MS analysis were stored at −80 °C prior to use.

Materials, reagents, and method development

SISCAPA-LC-MS and RAT

The methods are summarised in Figure 2 and described below. Full details of buffers and reagents are provided in the Supplementary data.

Sample preparation

The generic SISCAPA protocol [28] was modified to accommodate 100 µL of neat saliva samples. Briefly, neat saliva samples were initially treated with 500 µL ethanol to inactivate any viruses, thus allowing use in a biosafety level 2 laboratory. Proteins in the ethanol treated saliva (500 µL) were precipitated by addition of 1,000 µL of ice-cold acetone followed by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The precipitated pellets were reconstituted in 100 µL of 200 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer and split for use in SISCAPA-LC-MS (80 µL) and RAT (20 µL).

RAT

Part of the reconstituted pellet (20 µL) was transferred to extraction tubes along with 180 µL of extraction buffer provided in the Innova SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Rapid Qualitative Test kit (Innova Medical Group; Pasadena, CA, USA). The tubes were mixed and 100 µL were loaded onto the RAT test strip. NCAP was allowed to bind to the bound antibodies over 30 min. Photos were taken and uploaded into ImageJ (version 1.51o) where optical densitometry values were calculated over the entire test strip. Values were then normalised using the control strip lines to create a ratio.

SISCAPA surrogate peptide enrichment for LC-MS analysis

An “addition only” protocol was employed for analysis of viral NCAP by SISCAPA-LC-MS [28]. Reconstituted salivary protein pellets (80 µL) were transferred to a 96-deepwell plate and the proteins were denatured by addition of 73 µL denaturant solution [28]. Tryptic digestion of proteins was performed by addition of 10 µL of digestion solution followed by mixing and incubation for 30 min at 37 °C. Digestion was terminated with 5 µL stop solution [28]. Stable isotope labelled forms of the SARS-CoV-2 NCAP peptides (AYNVTQAFGR [AYN], DGIIWVATEGALNTPK [DGI], and ADETQALPQR [ADE]) were added as standards for quantitation. 30 µL of a suspension of protein G magnetic beads cross-linked with polyclonal, affinity-purified SISCAPA anti-peptide antibodies specific for each of the three proteotypic, surrogate target peptides from the SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein were added to the mixture and the plate was incubated for 1 h at room temperature on a microplate shaker (Stuart SSM5) at 180 RPM. The microplate was loaded onto a custom-made magnetic plate for sample preparation (SISCAPA Assay Technologies Inc.) designed to immobilize the magnetic beads and allow the unbound digest fraction to be removed before washing the beads thrice with 150 µL wash buffer [28]. Bead-bound peptides were acid-eluted from their specific antibody with 45 µL elution buffer before analysis by LC-MS [28]. In this study the SISCAPA protocol was performed by manual pipetting.

Targeted LC-MS analysis

Immuno-enriched proteotypic, surrogate peptides were resolved, separated and analysed using an ACQUITY ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) I-Class PLUS system coupled to a Xevo TQ-XS Tandem Quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, Manchester, UK), equipped with a Z-spray electrospray ionisation (ESI) source set to positive mode. An ACQUITY UPLC Peptide BEH C18 1.7 µm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm column was fitted to the LC system.

Peptide eluates were analysed as 10 µL injections and chromatographic separation was performed at a constant flow rate of 0.6 mL/min with water/0.1 % formic acid (A) and acetonitrile/0.1 % formic acid (B) mobile phases. A 3.5 min gradient was used: 95 % mobile phase A initial to 0.25 min, to 60 % A at 2.2 min, to 5 % A at 2.3 min until 2.8 min and to 95 % A at 3.15 min. Column temperature was set to 40 °C. For the source parameters; capillary voltage (0.6 kV), desolvation temperature (650 °C), desolvation flow (1000 L/h) and cone flow (150 L/h) were set accordingly. Simultaneous multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) of SARS-CoV-2 peptides AYN, DGI, and ADE and their stable isotope labelled analogues, was performed (Supplementary Table I).

LC-MS data processing, calibration, and interpretation

Data were imported into TargetLynx v4.2 (Waters Corporation, Manchester, UK) for transition review and into RStudio (version 1.4.1106) for calibration modelling and quantitative analysis. Peaks were integrated using Savitzky–Golay smoothing, and each integration was reviewed. Peaks were included for analysis only if >2 transitions were present for qualification of the signal. Calibration models were determined through triplicate analysis of saliva fortified with the NCAP peptides (AYN, DGI, ADE) over the range 0.01–25 fmol/μL. Models with the highest R2 values were selected and applied to all data for quantitative analysis (Supplementary Figure 2).

A positive sample was defined as the presence of AYN or the presence of both ADE and DGI peptides. The AYN peptide sequence has so far not been significantly affected by SARS-CoV-2 virus mutations [28] and its signal characteristics (noise, peak shape) were the most consistent of the peptides examined (data not shown). AYN and DGI have not mutated in known variants, although the Delta variant contains a D377Y mutation so that the ADE peptide becomes AYE [32]. All concentrations reported used the maximum value obtained for each peptide, where positive.

RT-PCR and RT-LAMP

RNA extraction

RNA was extracted from 200 µL of neat saliva as previously described [33]. Briefly, saliva was mixed with a binding solution (265 µL) using the MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit on a KingFisher Flex Purification system (Thermofisher, Loughborough, UK). The nucleic acid eluates were stored at −20 °C prior to RT-PCR analysis.

RT-PCR analysis

cDNA was produced by reverse transcribing the purified viral RNA using a RealStar® SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR kit (Altona Diagnostics, Hamburg, Germany). The SARS-CoV-2 E gene sequence region was targeted, using 10 µL of nucleic acid eluate. All Ct values were reported below Ct 40.

RT-LAMP analysis

Orf1a and NE-gene sequences were targeted using a fluorescence-based assay with reagents from New England Biolabs (Hitchin, UK) as described previously [10]. Reagents included WarmStart® RT-LAMP Master Mix (1×), fluorescent dye (1×), thermolabile UDG (0.02 U/µL), thermolabile dUTP (700 µM), RT-LAMP primers (1×, standard concentration) and 5 µL of nucleic acid eluate. The final reaction solution (25 µL in nuclease free water) was incubated at constant 65 °C using a thermocycler (StepOnePlus; Thermo Fisher, Loughborough, UK) with signal acquisition every 60 s. Time to positive (TTP) was measured in minutes.

Statistical analysis

Specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy analysis were performed for each of the methods against RT-PCR. Ct thresholds defined by the 95th and 75th percentiles were also tested. Peptide concentration (SISCAPA-LC-MS), Ct (RT-PCR), TTP (LAMP), and normalised optical densitometry data (RAT), results were imported into GraphPad Prism (version 4.07) for regression analysis and for F-tests comparing each method. Slopes that were below a p-value of 0.05 were deemed significantly different from zero. Regression analysis was performed only on positive samples.

Results

SISCAPA enrichment of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein peptides in trypsin-digested saliva from hospitalised patients

Representative LC-MS measurements of enriched, surrogate NCAP peptides in saliva samples from a COVID positive patient, a COVID negative patient and a matrix free (blank) sample are shown in Figure 3. The left-hand, middle, and right-hand panels display the MRM chromatograms for peptides DGI (retention time [T R ] 2.0 min), AYN (T R 1.5 min), and ADE (T R 1.0 min). Each peptide contains multiple fragment ion transitions in the COVID-19 positive patient (top panels). These transitions were absent in samples from both the COVID-19 negative patient (middle panels) and matrix free (blank) samples (bottom panels). The top panels in Figure 3 demonstrate that signals for each peptide fragment were strong enough to confidently identify the peptides. Unequivocal interpretation of the peptide peaks was facilitated by the SISCAPA immuno-affinity enrichment of the peptide targets, which effectively selectively, and specifically bound the target surrogate peptide while eliminating the non-specific peptides comprising the matrix background, thus significantly improving the signal to noise ratio. For quantitation, calibration models were fitted (Supplementary Figure 2). ADE, AYN, and DGI ADE peptides were all fit using a quadratic model (R2 0.99, 0.98, and 0.99, respectively).

LC-MS chromatogram of the three SISCAPA-enriched, targeted NCAP peptides from COVID positive saliva, COVID negative saliva and a blank sample (to show baseline noise).

Virus protein and nucleic acid detection in saliva using SISCAPA-LC-MS, RAT, RT-PCR, and RT-LAMP

Analysis of 102 saliva samples was performed using each of the protein detection or nucleic acid detection platforms. Virus peptides were detected in 25 patients (SISCAPA-LC-MS; median concentration 2.03 fmol/μL; S.D. 2.93). RAT showed a positive result in 13 patients (median optical density ratio 0.11; S.D. 0.42). Whereas a higher number of positives was seen using nucleic acid amplification methods. Virus RNA was detected by nucleic acid amplification in 44 patients (LAMP NE gene; median TTP 11.8 min; S.D. 2.9), 44 patients (LAMP Orf1a gene; median TTP 9.2 min; S.D. 2.5), and 53 patients (RT-PCR; median Ct 23.2; S.D. 6.0). A comparison of the results is shown in Figure 4. Of the cohort, 22.4 % were analytically positive across SISCAPA-LC-MS, RAT, RT-LAMP, and RT-PCR methods; 8.6 % of cases were positive only by SISCAPA-LC-MS; 15.5 % of cases were positive only by RT-PCR. No unique cases were identified by RAT. All samples positive by RT-LAMP were also positive when tested by RT-PCR.

Venn diagram showing the overlap of COVID-19 positive patients diagnosed using saliva by SISCAPA-LC-MS, RAT, RT-LAMP and RT-PCR.

Given that the stoichiometry of a proteotypic, surrogate peptide to its protein is 1:1, the median NCAP protein concentration in saliva was determined by the SISCAPA-LC-MS method to be 2.03 fmol/μL.

Specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy

Detection of the virus nucleoprotein in patients’ saliva by SISCAPA-LC-MS showed sensitivity of 37.7 %, specificity of 89.8 %, and accuracy of 62.7 % based on comparisons with RT-PCR (Table 1). RAT had lower sensitivity and accuracy across all samples (24.5 and 60.8 %, respectively), and higher specificity (100 %). Setting Ct thresholds by the 95th (Ct<27.5) and 75th (Ct<20.0) percentiles increased the sensitivity and accuracy between SISCAPA-LC-MS and RT-PCR. At <20 Ct, the SISCAPA-LC-MS sensitivity was 78.9 % when compared with RT-PCR. In addition, RT-LAMP sensitivity and specificity increased to 100 % at Ct values <27.5 the 75th percentile. Virus protein was only detected in five samples (SISCAPA-LC-MS) and one sample (RAT) when the RT-PCR Ct values were above 20. One case was detected by SISCAPA-LC-MS when the Ct was above 27.5. Over a quarter (26.6 %) of RT-PCR cases showed Ct values above 27.5.

Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy analysis of saliva RT-PCR compared to SISCAPA-LC-MS, RAT, and RT-LAMP. Ct cut-offs at 27.5 and 20 represent the 95th and 75th percentiles of the RT-PCR saliva data, respectively.

| Platform | RT-PCR (E) all | RT-PCR (E)<Ct 27.5 | RT-PCR (E)<Ct 20 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Accuracy, % | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Accuracy, % | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Accuracy, % | |

| LC-MS | 37.7 | 89.8 | 62.7 | 46.3 | 89.8 | 70.0 | 78.9 | 89.8 | 86.8 |

| RAT | 24.5 | 100.0 | 60.8 | 31.7 | 100.0 | 68.9 | 63.2 | 100.0 | 89.7 |

| LAMP (Orf1a) | 83.0 | 100.0 | 91.1 | 97.6 | 100.0 | 98.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| LAMP (N/E) | 81.1 | 98.0 | 89.2 | 97.6 | 98.0 | 97.8 | 100.0 | 98.0 | 98.5 |

Regression analysis

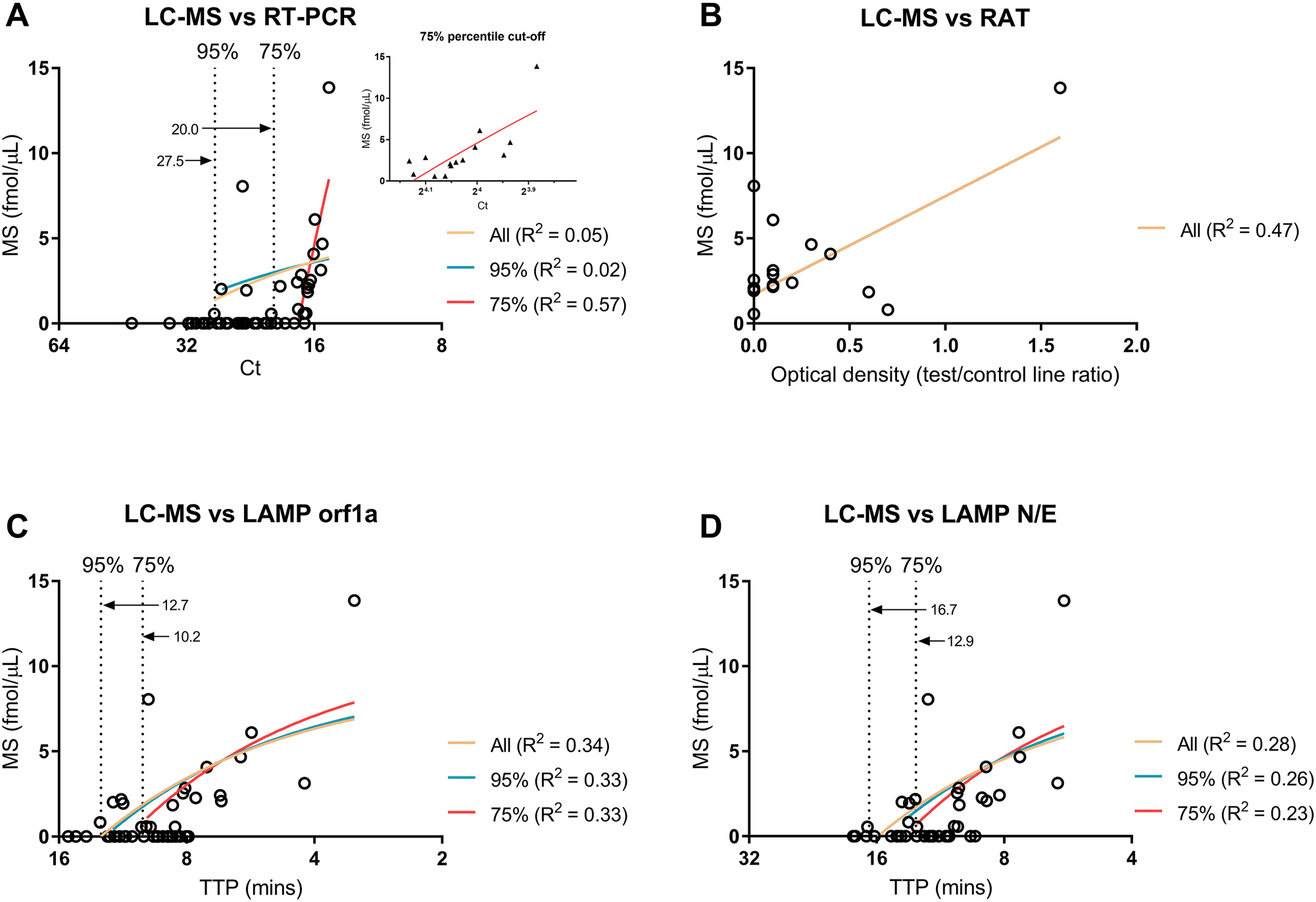

Results obtained with RT-PCR did not show significant correlation with SISCAPA-LC-MS using all data. The positive correlation between SISCAPA-LC-MS and RT-LAMP data (Orf1a: R2 0.34, p-value 0.007; NE: R2 0.28, p-value 0.018) was stronger than SISCAPA-LC-MS and RT-PCR (R2 0.05, p-value 0.32; Figure 5). On exploration of Ct cut-offs, regression on 75th percentile (Ct<20.0) demonstrated significant correlation between SISCAPA-LC-MS and RT-PCR (R2 0.57, p-value 0.002; Figure 5A). Setting cut-offs for RT-LAMP did not significantly improve correlation to SISCAPA-LC-MS: R2 was similar across each threshold (Figure 5C and D). On regression analysis, SISCAPA-LC-MS and RAT positively correlated (R2 0.47; Figure 5B). RT-LAMP and RT-PCR were linearly predictive of each other across most of the dataset, except Ct<18 where RT-LAMP followed a similar saturation effect as seen in the SISCAPA-LC-MS and RT-PCR regression analyses (Supplementary Figure 3).

Regression analysis of SISCAPA-LC-MS against different percentile cut-offs (95th and 75th) for RT-PCR (A) and RT-LAMP (C, D) in saliva samples from COVID-19 positive patients. The value at each cut off (Ct or TTP) is annotated within each graph. Linear regression was performed only for samples positive in both comparators. An insert of the 75th percentile is shown in A. Ct and TTP axes are scaled by log2. Regression analysis of SISCAPA-LC-MS against RAT is also shown (B). Photos of RAT were uploaded into densitometry software to calculate optical density across the test and control strips, using the control strips to normalise the data.

Discussion

This study describes 1) a high throughput and scalable, SISCAPA immuno-affinity LC-MS method capable of detecting and measuring SARS-CoV-2 proteins in saliva samples 2) a comparison of the SISCAPA-LC-MS protein (peptide) detection method with widely used virus RNA detection methods 3) a discussion of the suitability of saliva testing using RT-PCR, RT-LAMP, SISCAPA-LC-MS, and RAT for diagnosis of COVID-19 4) a description of discrepant results between RNA and protein detection methods 5) an indication that at different Ct thresholds nucleic acid tests may confer with protein tests.

It has been widely demonstrated by RT-PCR [33], [34], [35], [36] and RT-LAMP [10, 37], [38], [39], [40] that saliva is an appropriate sample for detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Since there is evidence that virus nucleic acid can persist in patients [7, 11], it is questionable whether methods such as RT-PCR can be used to determine infection or treatment status. The use of Ct as a surrogate for infectious status has drawn major criticism given the lack of standardisation between RT-PCR methods and differences seen between laboratories [5]. Detection of virus protein may be more indicative of active infection given their shorter detection window [11], although more research is required on this subject. We therefore sought to compare viral protein detection against RNA detection.

A few studies have used mass spectrometry platform for detection of SARS-CoV-2 proteins in saliva. Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) MS has been used for protein detection [27, 41], [42], [43], and nucleic acid detection [44]. A targeted metabolomics approach for identification of COVID-19 biomarkers demonstrated difficulty regarding sampling variability [45]. Reports have described methods for SARS-CoV-2 virus protein detection in triple point throat/nasopharynx/saliva swabs [28] and spiked saliva [25], although to the best of our knowledge, no study exists that uses SISCAPA-LC-MS in saliva samples within a clinical cohort. An LC-MS method that detects NCAP peptides in saliva and gargle fluid showed similar limits of detection (LOD) (0.5 fmol/μL) to that shown in this study (0.01 fmol/µL for AYN) and led us to believe that the protein detection assay may be suitable for the clinical samples used herein (median viral load was 2.03 fmol/μL) [42]. Interestingly, Kollhoff et al. has recently demonstrated a similar NCAP concentration in clinical nasopharyngeal swabs with SISCAPA-LC-MS [27].

We have recently shown 95 % sensitivity and specificity in a cohort of nasopharyngeal swabs when comparing RT-LAMP against RT-PCR [10]. In saliva, Amaral et al. demonstrated RT-LAMP sensitivity of 67.2 % compared to RT-PCR using nasopharyngeal swabs over the Ct range of 0–40, increasing to 85 % sensitivity below 28 Ct [37]. One study that used saliva found the sensitivity of RT-LAMP to be slightly worse than that of RT-PCR (70.9 vs. 81.6 %) in comparison to a nasopharyngeal RT-PCR test [40]. Our results align with those elsewhere, indicating that saliva RT-LAMP may be a suitable alternative to RT-PCR given the quicker turnaround and equivalent cost. In addition, detection of larger genomic fragments may better reflect active infection in comparison with RT-PCR.

We did not compare our methods against highly sensitive, automated antigen detection methods such as the LIAISON® SARS-CoV-2 Antigen chemiluminescent immunoassay assay [46]. Such tests are capable of processing reasonable numbers of samples (136 per hour) and are less expensive when compared to both RT-PCR and SISCAPA-LC-MS (approx. £3 vs. £20) [47]. However, it is not clear how antibodies to viral proteins would interfere with such immunoassays. Antibodies produced by patients upon infection or by immunization could be problematic in this regard, yielding lower or false-negative values. SISCAPA technology avoids this problem since antibodies are inactivated by trypsin digestion as part of the standard protocol.

We demonstrated that SISCAPA-LC-MS may detect NCAP in saliva of almost twice the number of people when compared to RAT, with the caveat that the RAT was used outside of its stipulated remit i.e. the manufacturer validated their tests using nasopharyngeal samples. Also, less neat saliva (10 µL, final equivalent) was loaded onto the RAT test strips vs. SISCAPA-LC-MS (approx. 17.8 µL injected), though one SISCAPA-LC-MS positive at 0.7 fmol/μL was also detected by RAT, demonstrating comparable absolute sensitivities. Again, interference with the point-of care immunoassays by anti-virus antibodies may be problematic.

SISCAPA-LC-MS detected viral protein (peptide) in only a fraction of the samples that were deemed positive based on the saliva RT-PCR test. This observation may be explained by the great sensitivity achieved by PCR-amplification assays whereas protein detection by the non-amplifying SISCAPA-LC-MS was less sensitive. Thus, PCR methods present excellent population screening assays for determination of virus RNA. Indeed, specificity was high against RT-PCR (89.8 %). In only a few instances was viral protein detected in the absence of viral RNA, which could be explained by differential clearance.

In contrast to virus nucleic acid, viral proteins are cleared rapidly [11, 48] in correlation with the viral load and thus may represent a more current picture of infection status and likelihood of transmission. It may be possible to use Ct cut-off values from PCR data to act as a surrogate for virus protein detection, but this will require studies comparing to viral cultures [5]. Our investigation of saliva Ct thresholds seen in RT-PCR showed that Ct 20 appears to be a possible cut-off level where SISCAPA-LC-MS and RT-PCR results become more congruous. The R2 between the measures was still low at this point (R2 0.57), however the use of more selective monoclonal capture antibodies rather than the polyclonal antibodies may have seen greater correlation. Van Puyvelde et al. compared the two antibodies in spiked universal transport media and found enhanced performance with monoclonal antibodies at lower concentrations [25].

Hällqvist et al. recently used SISCAPA-LC-MS with monoclonal antibodies on nasopharyngeal swabs, demonstrating 92.4 % sensitivity and 97.4 % specificity when compared to RT-PCR [24]. This indicated that the protein detection platforms were congruous with genetic material detection platforms. The salivary method we used for the work herein was less comparable to RT-PCR. However, as our study was done before the availability of the monoclonal antibodies (circa early 2021), polyclonal antibodies were used. Mangalaparthi et al. similarly used polyclonal antibodies and compared to RT-PCR with nasopharyngeal swabs and established an R2 of 0.63 for the DGI peptide with 100 % specificity and 93 % sensitivity [29], implying nasopharyngeal swabs are more suitable than saliva when comparing SISCAPA-LC-MS to RNA tests.

The manual implementation of the SISCAPA-LC-MS protocol described here currently can provide results in less than 2.5 h of sampling (2.25 h for sample processing, 3.5 min LC-MS run time). Using four 96-well plates, approximately 400 samples can be manually processed per day using a single, at capacity, LC-MS system. Full automation of the SISCAPA workflow has been shown to drastically increase the throughput capabilities of this approach by a) increasing the number of samples that can be processed in a day [21] and b) reducing the need for chromatography by eliminating the nonspecific peptide background [40]. Given the state of automation of this workflow (versions available for most laboratory robotic platforms) and the fact that the LC format used here (UPLC) is also utilised in routine clinical laboratories, we foresee few challenges for large scale implementation of this method. It is also possible that dried blood spot sampling of patients can be used for longitudinal COVID-19 monitoring [49]. Currently, the cost per SISCAPA-LC-MS test is approximately equivalent to that of RT-PCR, depending on location.

Limitations of the study

Saliva was stored for up to 3 days prior to analysis at 4 °C prior to RT-PCR and RT-LAMP analysis, although others have demonstrated non-significant change in Ct after 26 days at 4 °C [50]. No study was done on the preanalytical differences and reproducibility of drool saliva, where issues have been discussed in previous studies [45]. Data on patient demographics were not sought, neither were data on initial onset, symptom severity and disease outcomes. Such data would have enabled assessment of viral load vs. disease status determined by protein and RNA assays. Future work on the comparison of the protein and genomic material would benefit by contextual information at the time of sample collection (i.e. which measurement had a better diagnostic/prognostic value). The comparison to viral culture methods would have also been beneficial in order to establish a transmission/infectiousness cut-off against the tests presented herein. Furthermore, the use of monoclonal SISCAPA antibodies may have increased assay sensitivity, although these were not available at the time of the study. The validity of the SISCAPA-LC-MS method could be supported with future studies exploring these types of experimental and clinical data.

RAT was used on a matrix that the tests were not explicitly produced for, although saliva was investigated across all detection platforms and may therefore be compared.

In the work reported here, a saliva based RT-PCR kit was used outside its intended remit i.e. use in nasopharyngeal swabs. Furthermore, the SISCAPA-LC-MS test and the PCR-based tests compared dissimilar viral components (genetic material vs. proteins). Their direct comparison may not be meaningful without context of what each component is a marker for i.e. exposure, active infection etc.

Conclusions

We report a high throughput and scalable SISCAPA immuno-affinity LC-MS method that can detect and measure SARS-CoV-2 protein in saliva samples using polyclonal antibodies. We also report detection of viral nucleic acid by RT-LAMP and RT-PCR. A RAT was also tested for the detection of viral protein. The relationship between RT-PCR Ct values and protein load as determined by the SISCAPA-LC-MS method requires further study. SISCAPA-LC-MS can be a useful tool for studying viral peptides, although we detected SARS-CoV-2 protein less frequently than viral RNA in saliva.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the UK Medical Research Council Confidence in Concept (MRC CiC) Funding (Grant Number: MC_PC_18054). We acknowledge the support of the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre and the John and Lucille van Geest Foundation.

-

Research ethics: SARS-CoV-2 RT-LAMP saliva study; REC approval number 20/EE/0212.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: DJ was supported the Department of Health and Social Care funding and a Medical Research Council mid-range equipment grant. KK is the Chair of the Ethnicity Subgroup of the UK Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE). MP, MR, RY, LA, and TP are members of SISCAPA Assay Technologies Inc. PG was supported by Hologic Ltd.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Kissler, SM, Tedijanto, C, Goldstein, E, Grad, YH, Lipsitch, M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science 2020;368:860–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb5793.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard; Updated June 2023. https://covid19.who.int/ [Accessed 23 Jun 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

3. Arnaout, R, Lee, RA, Lee, GR, Callahan, C, Cheng, A, Yen, CF, et al.. The limit of detection matters: the case for benchmarking severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 testing. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e3042–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1382.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Böger, B, Fachi, MM, Vilhena, RO, Cobre, AF, Tonin, FS, Pontarolo, R. Systematic review with meta-analysis of the accuracy of diagnostic tests for COVID-19. Am J Infect Control 2021;49:21–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.07.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Favresse, J, Douxfils, J, Henry, B, Lippi, G, Plebani, M. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine celebrates 60 years – narrative review devoted to the contribution of the journal to the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023;61:811–21. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2022-1166.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Singanayagam, A, Patel, M, Charlett, A, Bernal, JL, Saliba, V, Ellis, J, et al.. Duration of infectiousness and correlation with RT-PCR cycle threshold values in cases of COVID-19, England, January to May 2020. Euro Surveill 2020;25:2001483. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2020.25.32.2001483.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Aranha, C, Patel, V, Bhor, V, Gogoi, D. Cycle threshold values in RT-PCR to determine dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 viral load: an approach to reduce the isolation period for COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol 2021;93:6794–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27206.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Liu, W-D, Chang, S-Y, Wang, J-T, Tsai, M-J, Hung, C-C, Hsu, C-L, et al.. Prolonged virus shedding even after seroconversion in a patient with COVID-19. J Infect 2020;81:318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.063.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Augustine, R, Hasan, A, Das, S, Ahmed, R, Mori, Y, Notomi, T, et al.. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): a rapid, sensitive, specific, and cost-effective point-of-care test for coronaviruses in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Biology 2020;9:182. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9080182.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Allsopp, R, Cowley, C, Barber, R, Jones, C, Holmes, C, Bird, P, et al.. A rapid RT-LAMP SARS-CoV-2 screening assay for collapsing asymptomatic COVID-19 transmission. PLoS One 2022;17:e0273912. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273912.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Mencacci, A, Gili, A, Gidari, A, Schiaroli, E, Russo, C, Cenci, E, et al.. Role of nucleocapsid protein antigen detection for safe end of isolation of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients with long persistence of viral RNA in respiratory samples. J Clin Med 2021;10:4037. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184037.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. FDA. Stop using Innova Medical Group SARS-CoV-2 antigen rapid qualitative test: FDA safety communication; Updated 2021. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/stop-using-innova-medical-group-sars-cov-2-antigen-rapid-qualitative-test-fda-safety-communication [Accessed 21 Oct 2021].Suche in Google Scholar

13. Mahase, E. Covid-19: Innova lateral flow test is not fit for “test and release” strategy, say experts. BMJ 2020;371:m4469. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4469.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Dinnes, J, Deeks, JJ, Berhane, S, Taylor, M, Adriano, A, Davenport, C, et al.. Rapid, point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;8:CD013705. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013705.pub2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Mbasu, RJ, Heaney, LM, Molloy, BJ, Hughes, CJ, Ng, LL, Vissers, JP, et al.. Advances in quadrupole and time-of-flight mass spectrometry for peptide MRM based translational research analysis. Proteomics 2016;16:2206–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.201500500.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Couchman, L, Fisher, DS, Subramaniam, K, Handley, SA, Boughtflower, RJ, Benton, CM, et al.. Ultra-fast LC-MS/MS in therapeutic drug monitoring: quantification of clozapine and norclozapine in human plasma. Drug Test Anal 2018;10:323–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.2223.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Seger, C, Salzmann, L. After another decade: LC-MS/MS became routine in clinical diagnostics. Clin Biochem 2020;82:2–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2020.03.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Ng, LL, Sandhu, JK, Squire, IB, Davies, JE, Jones, DJ. Vitamin D and prognosis in acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:2341–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.030.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Lane, D, Lawson, A, Burns, A, Azizi, M, Burnier, M, Jones, DJ, et al.. Nonadherence in hypertension: how to develop and implement chemical adherence testing. Hypertension 2022;79:12–23. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.121.17596.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Razavi, M, Anderson, NL, Pope, ME, Yip, R, Pearson, TW, Bassini-Cameron, A, et al.. Precision multiparameter tracking of inflammation on timescales of hours to years using serial dried blood spots. Bioanalysis 2020;12:937–55. https://doi.org/10.4155/bio-2019-0278.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Hoofnagle, AN, Becker, JO, Wener, MH, Heinecke, JW. Quantification of thyroglobulin, a low-abundance serum protein, by immunoaffinity peptide enrichment and tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem 2008;54:1796–804. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2008.109652.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Van Puyvelde, B, Van Uytfanghe, K, Tytgat, O, Van Oudenhove, L, Gabriels, R, Bouwmeester, R, et al.. Cov-MS: a community-based template assay for mass-spectrometry-based protein detection in SARS-CoV-2 patients. JACS Au 2021;1:750–65. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.1c00048.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Razavi, M, Anderson, NL, Pope, ME, Yip, R, Pearson, TW. High precision quantification of human plasma proteins using the automated SISCAPA immuno-MS workflow. New Biotechnol 2016;33:494–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbt.2015.12.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Hällqvist, J, Lane, D, Shapanis, A, Davis, K, Heywood, WE, Doykov, I, et al.. Operation Moonshot: rapid translation of a SARS-CoV-2 targeted peptide immunoaffinity liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry test from research into routine clinical use. Clin Chem Lab Med 2022;61:302–10. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2022-1000.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Van Puyvelde, B, Van Uytfanghe, K, Van Oudenhove, L, Gabriels, R, Van Royen, T, Matthys, A, et al.. Cov2MS: an automated and quantitative matrix-independent assay for mass spectrometric measurement of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Anal Chem 2022;94:17379–87. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.2c01610.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Waters Corporation. Comprehending COVID-19: distinct identification of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant using the SARS-CoV-2 LC-MS kit (RUO); Updated 2021. https://www.waters.com/nextgen/gb/en/library/application-notes/2021/comprehending-covid-19-distinct-identification-of-the-sars-cov-2-delta-variant-using-the-sars-cov-2-lc-ms-kit-ruo.html [Accessed 25 Sept 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

27. Kollhoff, L, Kipping, M, Rauh, M, Ceglarek, U, Barka, G, Barka, F, et al.. Development of a rapid and specific MALDI-TOF mass spectrometric assay for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Clin Proteomics 2023;20:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-023-09415-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Hober, A, Tran-Minh, KH, Foley, D, McDonald, T, Vissers, JP, Pattison, R, et al.. Rapid and sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection using quantitative peptide enrichment LC-MS analysis. eLife 2021;10:e70843. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.70843.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Mangalaparthi, KK, Chavan, S, Madugundu, AK, Renuse, S, Vanderboom, PM, Maus, AD, et al.. A SISCAPA-based approach for detection of SARS-CoV-2 viral antigens from clinical samples. Clin Proteomics 2021;18:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-021-09331-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Ascoli, CA, Aggeler, B. Overlooked benefits of using polyclonal antibodies. BioTechniques 2018;65:127–36. https://doi.org/10.2144/btn-2018-0065.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Huang, N, Pérez, P, Kato, T, Mikami, Y, Okuda, K, Gilmore, RC, et al.. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the oral cavity and saliva. Nat Med 2021;27:892–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01296-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Hulo, C, De Castro, E, Masson, P, Bougueleret, L, Bairoch, A, Xenarios, I, et al.. ViralZone: a knowledge resource to understand virus diversity. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:D576–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq901.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Azzi, L, Carcano, G, Gianfagna, F, Grossi, P, Dalla Gasperina, D, Genoni, A, et al.. Saliva is a reliable tool to detect SARS-CoV-2. J Infect 2020;81:e45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. To, KK-W, Tsang, OT-Y, Leung, W-S, Tam, AR, Wu, T-C, Lung, DC, et al.. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:565–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30196-1.Suche in Google Scholar

35. To, KK-W, Tsang, OT-Y, Yip, CC-Y, Chan, K-H, Wu, T-C, Chan, JM-C, et al.. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:841–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa149.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Wyllie, AL, Fournier, J, Casanovas-Massana, A, Campbell, M, Tokuyama, M, Vijayakumar, P, et al.. Saliva or nasopharyngeal swab specimens for detection of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1283–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2016359.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Amaral, C, Antunes, W, Moe, E, Duarte, AG, Lima, LM, Santos, C, et al.. A molecular test based on RT-LAMP for rapid, sensitive and inexpensive colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Sci Rep 2021;11:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95799-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Dudley, DM, Newman, CM, Weiler, AM, Ramuta, MD, Shortreed, CG, Heffron, AS, et al.. Optimizing direct RT-LAMP to detect transmissible SARS-CoV-2 from primary nasopharyngeal swab samples. PLoS One 2020;15:e0244882. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244882.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Lalli, MA, Langmade, JS, Chen, X, Fronick, CC, Sawyer, CS, Burcea, LC, et al.. Rapid and extraction-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 from saliva by colorimetric reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Clin Chem 2021;67:415–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvaa267.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Nagura-Ikeda, M, Imai, K, Tabata, S, Miyoshi, K, Murahara, N, Mizuno, T, et al.. Clinical evaluation of self-collected saliva by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR), direct RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification, and a rapid antigen test to diagnose COVID-19. J Clin Microbiol 2020;58:1438. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01438-20.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Iles, RK, Zmuidinaite, R, Iles, JK, Carnell, G, Sampson, A, Heeney, JL. Development of a clinical MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry assay for SARS-CoV-2: rational design and multi-disciplinary team work. Diagnostics 2020;10:746. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10100746.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Kipping, M, Tänzler, D, Sinz, A. A rapid and reliable liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry method for SARS-CoV-2 analysis from gargle solutions and saliva. Anal Bioanal Chem 2021;413:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-021-03614-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Costa, MM, Martin, H, Estellon, B, Dupé, F-X, Saby, F, Benoit, N, et al.. Exploratory study on application of MALDI-TOF-MS to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection in human saliva. J Clin Med 2022;11:295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11020295.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Hernandez, MM, Banu, R, Shrestha, P, Patel, A, Chen, F, Cao, L, et al.. RT-PCR/MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry-based detection of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva specimens. J Med Virol 2021;93:5481–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27069.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Spick, M, Lewis, H-M, Frampas, CF, Longman, K, Costa, C, Stewart, A, et al.. An integrated analysis and comparison of serum, saliva and sebum for COVID-19 metabolomics. Sci Rep 2022;12:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16123-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. DiaSorin S.p.A. LIAISON® SARS-CoV-2 antigen: a quantitative antigen assay to achieve maximum impact in testing COVID-19 symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. https://www.diasorin.com/sites/default/files/allegati_prodotti/liaisonr_sars-cov-2_ag_assay_m0870004373_c_lr.pdf [Accessed 03 Jul 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

47. Pighi, L, Henry, BM, Mattiuzzi, C, De Nitto, S, Salvagno, GL, Lippi, G. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different COVID-19 screening strategies based on rapid or laboratory-based SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023;61:e168–71. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-0164.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Ogata, AF, Maley, AM, Wu, C, Gilboa, T, Norman, M, Lazarovits, R, et al.. Ultra-sensitive serial profiling of SARS-CoV-2 antigens and antibodies in plasma to understand disease progression in COVID-19 patients with severe disease. Clin Chem 2020;66:1562–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvaa213.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Razavi, M, Anderson, NL, Yip, R, Pope, ME, Pearson, TW. Multiplexed longitudinal measurement of protein biomarkers in DBS using an automated SISCAPA workflow. Bioanalysis 2016;8:1597–609. https://doi.org/10.4155/bio-2016-0059.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Alfaro-Núñez, A, Crone, S, Mortensen, S, Rosenstierne, MW, Fomsgaard, A, Marving, E, et al.. SARS-CoV-2 RNA stability in dry swabs for longer storage and transport at different temperatures. Transboundary Emerging Dis 2022;69:189–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14339.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-0243).

© 2023 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- SARS-CoV-2 is here to stay: do not lower our guard

- Reviews

- SARS-CoV-2 subgenomic RNA: formation process and rapid molecular diagnostic methods

- Prognostic value of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: a systematic review

- Presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in COVID-19 survivors with post-COVID symptoms: a systematic review of the literature

- Opinion Papers

- Harmonizing the post-analytical phase: focus on the laboratory report

- Blood-based biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease – moving towards a new era of diagnostics

- A comprehensive review on PFAS including survey results from the EFLM Member Societies

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Report from the HarmoSter study: different LC-MS/MS androstenedione, DHEAS and testosterone methods compare well; however, unifying calibration is a double-edged sword

- An LC–MS/MS method for serum cystatin C quantification and its comparison with two commercial immunoassays

- CX3CL1/Fractalkine as a biomarker for early pregnancy prediction of preterm premature rupture of membranes

- Elevated S100B urine levels predict seizures in infants complicated by perinatal asphyxia and undergoing therapeutic hypothermia

- The correlation of urea and creatinine concentrations in sweat and saliva with plasma during hemodialysis: an observational cohort study

- Tubular phosphate transport: a comparison between different methods of urine sample collection in FGF23-dependent hypophosphatemic syndromes

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Monocyte distribution width (MDW): study of reference values in blood donors

- Data mining of reference intervals for serum creatinine: an improvement in glomerular filtration rate estimating equations based on Q-values

- Hematology and Coagulation

- MALDI-MS in first-line screening of newborns for sickle cell disease: results from a prospective study in comparison to HPLC

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- To rule-in, or not to falsely rule-out, that is the question: evaluation of hs-cTnT EQA performance in light of the ESC-2020 guideline

- Temporal biomarker concentration patterns during the early course of acute coronary syndrome

- Diabetes

- Proteomic analysis of diabetic retinopathy identifies potential plasma-protein biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis

- Infectious Diseases

- Serum biomarkers of inflammation and vascular damage upon SARS-Cov-2 mRNA vaccine in patients with thymic epithelial tumors

- A high throughput immuno-affinity mass spectrometry method for detection and quantitation of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein in human saliva and its comparison with RT-PCR, RT-LAMP, and lateral flow rapid antigen test

- Evaluation of inflammatory biomarkers and vitamins in hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and post-COVID syndrome

- The CoLab score is associated with SARS-CoV-2 viral load during admission in individuals admitted to the intensive care unit: the CoLaIC cohort study

- Development and evaluation of a CRISPR-Cas13a system-based diagnostic for hepatitis E virus

- Letters to the Editor

- Crioplast® is a reliable device to ensure pre-analytical stability of adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH)

- Falsely decreased Abbott Alinity-c gamma-glutamyl transferase-2 result from paraprotein and heparin interference: case report and subsequent laboratory experiments

- Impact of hemolysis on uracilemia in the context of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency testing

- Value of plasma neurofilament light chain for monitoring efficacy in children with later-onset spinal muscular atrophy under nusinersen treatment

- Analytical evaluation of the Snibe β-isomerized C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (β-CTX-I) automated method

- Acute myeloid leukemia with blue-green neutrophilic inclusions have different outcomes: two cases and review of the literature

- Congress Abstracts

- The 10+1 Santorini Conference

- 14th National Congress of the Portuguese Society of Clinical Chemistry, Genetics and Laboratory Medicine

- 15th National Congress of the Portuguese Society of Clinical Chemistry, Genetics and Laboratory Medicine

- ISMD2024 Thirteenth International Symposium on Molecular Diagnostics

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- SARS-CoV-2 is here to stay: do not lower our guard

- Reviews

- SARS-CoV-2 subgenomic RNA: formation process and rapid molecular diagnostic methods

- Prognostic value of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: a systematic review

- Presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in COVID-19 survivors with post-COVID symptoms: a systematic review of the literature

- Opinion Papers

- Harmonizing the post-analytical phase: focus on the laboratory report

- Blood-based biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease – moving towards a new era of diagnostics

- A comprehensive review on PFAS including survey results from the EFLM Member Societies

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Report from the HarmoSter study: different LC-MS/MS androstenedione, DHEAS and testosterone methods compare well; however, unifying calibration is a double-edged sword

- An LC–MS/MS method for serum cystatin C quantification and its comparison with two commercial immunoassays

- CX3CL1/Fractalkine as a biomarker for early pregnancy prediction of preterm premature rupture of membranes

- Elevated S100B urine levels predict seizures in infants complicated by perinatal asphyxia and undergoing therapeutic hypothermia

- The correlation of urea and creatinine concentrations in sweat and saliva with plasma during hemodialysis: an observational cohort study

- Tubular phosphate transport: a comparison between different methods of urine sample collection in FGF23-dependent hypophosphatemic syndromes

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Monocyte distribution width (MDW): study of reference values in blood donors

- Data mining of reference intervals for serum creatinine: an improvement in glomerular filtration rate estimating equations based on Q-values

- Hematology and Coagulation

- MALDI-MS in first-line screening of newborns for sickle cell disease: results from a prospective study in comparison to HPLC

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- To rule-in, or not to falsely rule-out, that is the question: evaluation of hs-cTnT EQA performance in light of the ESC-2020 guideline

- Temporal biomarker concentration patterns during the early course of acute coronary syndrome

- Diabetes

- Proteomic analysis of diabetic retinopathy identifies potential plasma-protein biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis

- Infectious Diseases

- Serum biomarkers of inflammation and vascular damage upon SARS-Cov-2 mRNA vaccine in patients with thymic epithelial tumors

- A high throughput immuno-affinity mass spectrometry method for detection and quantitation of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein in human saliva and its comparison with RT-PCR, RT-LAMP, and lateral flow rapid antigen test

- Evaluation of inflammatory biomarkers and vitamins in hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and post-COVID syndrome

- The CoLab score is associated with SARS-CoV-2 viral load during admission in individuals admitted to the intensive care unit: the CoLaIC cohort study

- Development and evaluation of a CRISPR-Cas13a system-based diagnostic for hepatitis E virus

- Letters to the Editor

- Crioplast® is a reliable device to ensure pre-analytical stability of adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH)

- Falsely decreased Abbott Alinity-c gamma-glutamyl transferase-2 result from paraprotein and heparin interference: case report and subsequent laboratory experiments

- Impact of hemolysis on uracilemia in the context of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency testing

- Value of plasma neurofilament light chain for monitoring efficacy in children with later-onset spinal muscular atrophy under nusinersen treatment

- Analytical evaluation of the Snibe β-isomerized C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (β-CTX-I) automated method

- Acute myeloid leukemia with blue-green neutrophilic inclusions have different outcomes: two cases and review of the literature

- Congress Abstracts

- The 10+1 Santorini Conference

- 14th National Congress of the Portuguese Society of Clinical Chemistry, Genetics and Laboratory Medicine

- 15th National Congress of the Portuguese Society of Clinical Chemistry, Genetics and Laboratory Medicine

- ISMD2024 Thirteenth International Symposium on Molecular Diagnostics