Abstract

In 2013, a marine heatwave called the “Blob” caused northern California bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) populations to decrease significantly. The loss of this foundation species motivated recent investigations on kelp thermal tolerance to understand how warming events might impact their physiological performance. We tested the effect of acclimation temperature on bull kelp by measuring the protein abundance of a molecular chaperone, heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70). Blades were collected from two sites (Big River and Russian Gulch) and acclimated for 7-days at two temperatures (13 and 17 °C) before tissues were subjected to a 1-h heat shock (13, 17, 20, 23, and 26 °C). Results showed a significant difference between acclimation temperature with 20 % greater total Hsp70 protein abundance in bull kelp acclimated to the warm treatment, while site was only marginally different. Heat shock temperature had no effect on total Hsp70 protein abundance. This study is the first to report about the heat shock response of bull kelp and found that thermal history of an organism is an important factor in determining whether an organism can mount a heat shock response. This information can help understand bull kelp’s tolerance to future marine heatwaves.

1 Introduction

Climate change is affecting marine environments across the globe (Fujita 2013; Galland et al. 2012; Hoegh-Guldberg and Bruno 2010; Kortsch et al. 2015), specifically, global air temperatures have risen by 0.85 °C since 1800 and are projected to increase at least by another 1.5 °C by the end of the century (Boer and Yu 2003; Flato and Boer 2001; Helmuth et al. 2002; Makwana et al. 2024). This increase in air temperature has affected ocean warming indices and circulation patterns (Pacific Decadal Oscillation, El Niño-Southern Oscillation, and North Pacific Gyre Oscillation), which has contributed to an increase in the occurrence of marine heatwaves (Oliver et al. 2019, 2021). The combination of the local weather, oceanographic patterns, and longer-term climate shifts (Oliver et al. 2021) have increased the frequency of marine heatwaves per year by 50 % in the last two centuries (Smale et al. 2019). Recorded thus far, marine heatwaves can vary in area impacted from 200 to 5,000 km2, last from 5 to 500 days, and increase the local water temperature by 1–4.5 °C above average (Oliver et al. 2021). For marine organisms with narrow thermal limits and sensitive thermoregulatory systems, marine heatwaves can present a distinct threat to their survival (Reed et al. 2022; Smith et al. 2023).

Between 2013 and 2016, Sonoma and Mendocino Counties along the California coast experienced a sequential series of dramatic environmental changes. The most relevant change was the formation of an unprecedented marine heatwave known as “The Blob” (Di Lorenzo and Mantua 2016; Oliver et al. 2019; Reed et al. 2016; Rogers-Bennett and Catton 2019; Smale et al. 2019). The Blob formed in 2014 from a combination of a weak North Pacific High – a semi-permanent cyclone that sits above the Pacific Ocean north of Hawaii and west of California (Kenyon 1999) – and a weakened coastal upwelling season in the Northern California Current. Whereupon, it proceeded to raise the sea surface temperature in the area by 7 °C within an hour of its arrival (Leising et al. 2015; Peterson et al. 2017). Winds that would normally displace surface water in the upwelling process were too weak to move the buoyant warm water, so the water simply stayed in place and grew in mass over time (Bond et al. 2015), making it one of the longest-lasting and the largest marine heatwaves on record (Oliver et al. 2021). Coinciding with the formation of the Blob was an outbreak of sea star wasting disease and a boom in the purple sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) population (Di Lorenzo and Mantua 2016; Oliver et al. 2019; Reed et al. 2016; Rogers-Bennett and Catton 2019; Smale et al. 2019).

This series of events resulted in a massive loss of over 90 % of bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana Postels et Ruprecht 1840) coverage across its historic range in Sonoma and Mendocino Counties (Catton et al. 2016), more than 350 km of coastline (Rogers-Bennett and Catton 2019). Much of the area formerly inhabited by bull kelp transformed into sea urchin barrens; large areas of rock populated primarily by sea urchins and crustose coralline algae (Beisner et al. 2003; Ellison 2019). Without the kelp, there was a distinct lack of availability of food and shelter for less voracious organisms, such as fish, mollusks, and crustaceans (Catton et al. 2016), leading to a loss of biodiversity. This “perfect storm” of events (Catton et al. 2016) demonstrated the true importance of bull kelp as a foundation species to California’s coastal environments.

Northern bull kelp can be found within a ∼4,800 km range on North America’s west coast, stretching from Point Conception, California to Unimak Island, Alaska (Contolini et al. 2021) and tends to grow at depths of 3–20 m, inhabiting bedrock, rocky reefs, or boulder fields, which they use to recruit and develop holdfasts (Springer et al. 2007). Bull kelp is considered a foundation species by which a food web and/or dynamic ecosystem may be structured or built (Ellison 2019). Bull kelp consists of a microscopic haploid stage – known as the gametophyte – and a macroscopic diploid stage – known as the sporophyte (Dobkowski and Crofts 2021). It has been suggested that the upper thermal limit for bull kelp from central California is above 15 °C, as it will inhibit sporophyte growth (Wheeler et al. 1984), while more recent studies have found the optimal growth temperature can range between 2 and 17 °C (Contolini et al. 2021; Supratya et al. 2020). Like most kelp species, bull kelp has been affected by the increasing frequency of marine heatwaves, but the effects themselves have been different depending on location. For example, bull kelp populations in Alaska (USA) showed variable to stable responses during the Blob (Starko et al. 2025), but populations in the lower northern California range lost significant abundance (Catton et al. 2016; Smale 2020). So far, the only metrics used to measure the thermal response of bull kelp have been physical or ecological, such as reproductive success (Korabik et al. 2023; Muth et al. 2019), blade growth and structure (Supratya et al. 2020). If we can use molecular tools to measure the physiological response of bull kelp to environmental changes, we may be able detect how perturbations, like temperature, affect an organism’s ability to minimize mortality rather than only relying on physical assessment (Ryan and Hightower 1999).

Stress-inducible heat shock proteins are a specific group of molecular chaperones used for examining temperature, and are highly conserved across species (Camarena-Novelo et al. 2019). When most eukaryotic organisms are subjected to environmental stress, cells will undergo a process called the heat shock response (HSR; Krivoruchko and Storey 2010). This response serves the dual purpose of repairing cellular damage brought on by physiological stress and preparing for the next instance of stress, rather than only serving as a preventative measure (Verghese et al. 2012). It acts as a series of changes in gene expression to suppress normal protein biosynthesis, and induces cytoprotective genes, which code for heat shock proteins (Vierling 1991). Heat shock proteins (Hsps) are responsible for preventing other proteins from denaturing under stress (Adham et al. 1991). The most extensively studied family of heat shock proteins is Hsp70 (Vayda and Yuan 1994), which has been observed in almost all organisms and has both constitutive and inducible isoforms (Brown et al. 1993; Hu et al. 2022). The constitutive proteins are expressed and transcribed at the same rate as any protein, and are responsible for folding new cytoplasmic proteins and secretory proteins (Verghese et al. 2012), while the inducible forms aid in many physiological stress responses, such as protecting thermally damaged proteins from aggregation, unfolding aggregated proteins, either refolding damaged proteins or selecting them for degradation, and moving proteins to their needed locations in the event of physiological stress (Place et al. 2004). All Hsp70s require the hydrolysis of ATP, making the process energetically costly (Vierling 1991).

The mechanistic machinery of the HSR is widely studied in the field of ecophysiology, as it can influence – indirectly – physiological patterns from the cellular level up to the whole organism (Lindquist 1986). These patterns, in turn, affect how organisms are able to cope with living in a dynamic and ever-changing environment, such as the ocean (Hofmann 2005). Special attention has been paid to the gene expression and protein abundance components of the HSR in intertidal invertebrates (Brokordt et al. 2015; Giudice et al. 1999; Sorte and Hofmann 2004; Tomanek and Somero 1999, 2002–to name a few), and fish from different thermal niches (Lewis et al. 2016; Place et al. 2004). Pushing the stress response to its limit will define where an organism’s thermal homeostatic range lies, and how that may vary throughout an organism’s lifetime (Giudice et al. 1999). Sessile organisms, in particular, can be more vulnerable to thermal stress but have been shown to adjust their HSRs seasonally (or on a long-term scale), as they are unable to escape temperature fluctuation, and therefore must acclimatize to their surroundings on a regular basis (Hofmann 1999).

In marine algae, the gene expression of hsp70 has been studied more extensively (Hara et al. 2022; Hereward et al. 2020; Henkel and Hofmann 2008a, 2009; Jueterbock et al. 2014; King et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019) than protein abundance. However, the few studies with Hsp70 protein were conducted in a variety of green (Ulva prolifera; Fan et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2012), red (Gracilaria vermiculophylla; Hammann et al. 2016) and brown algae (Fucus serratus; Ireland et al. 2004), where it has been noted that Hsp70 protein concentration can rapidly increase within 1–2 h of exposure to thermal stress, and as late as 24 h. Given the likelihood of continued increase in the occurrence of marine heatwaves (Oliver et al. 2019), this suggests measuring Hsp70 protein abundance may be a useful indicator detecting cellular temperature stress in bull kelp. To the best of our knowledge, there has been little to no research on the thermal tolerance of bull kelp at the molecular level. In this current study, we examine the physiological response of N. luetkeana to thermal stress using individuals from two bull kelp populations on the northern California coast. By measuring Hsp70 protein abundance from blades acclimated to ambient seawater temperature (13 °C) compared to those acclimated under warmer seawater temperature (17 °C), we can assess whether bull kelp populations mount a HSR during short-term heating events, similar to that of marine heatwaves, and if thermal history and population play a role in determining thermal tolerance.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bull kelp sampling and blade preparation

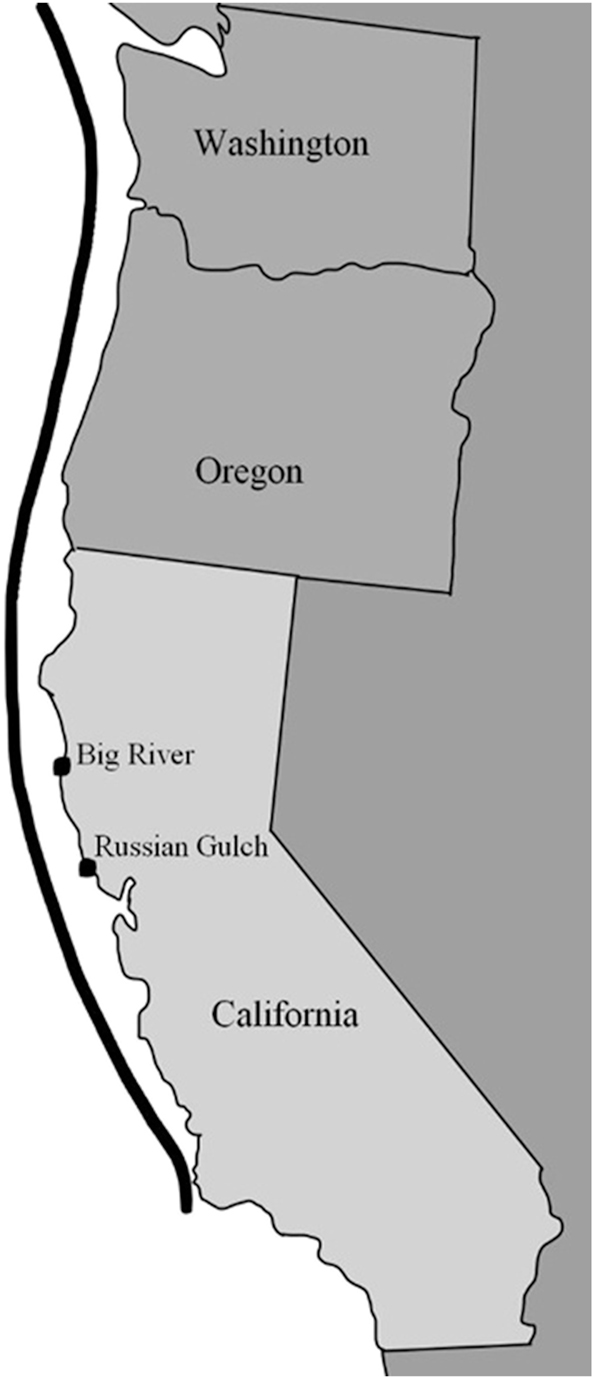

We collected vegetative sporophyte blades from Nereocystis luetkeana from two sites: Big River, Mendocino County, CA, USA (39° 18′ 5.292ʺ N123° 45′ 26.784ʺ W) and Russian Gulch, Sonoma County, CA, USA (39° 19′ 53.472ʺ N 123° 47′ 21.696ʺ W; Figure 1) in October 2022, with Big River designated as the northern site and Russian Gulch designated the southern site. The two sites are approximately 129 km from each other toward the southern range of distribution for bull kelp. The Big River site is located at the shallower northwest end of Mendocino Bay near the mouth of the Big River behind the Mendocino Headlands, while the Russian Gulch site is located at Russian Gulch State beach, a relatively isolated cove with a steep, sloping shore. No environmental conditions or metrics were measured; site descriptions were based on visual observation and field notes (personal observation, Brent Hughes).

Bull kelp field collection sites. Vegetative sporophyte blades (n = 5) were collected from two field sites: northern site = Big River Beach, Mendocino County, CA (USA) and southern site = Russian Gulch State Beach, Sonoma County, CA (USA), denoted by a black dot. The black line represents bull kelp distribution along the western Pacific coast extending up into the Aleutian Islands.

We collected vegetative blades from five randomly selected individual sporophytes per site, placed the blades in coolers between paper towels soaked with seawater, and transported them to the University of California, Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory (USA) for preparation. We cut the collected vegetative sporophyte into 25.4-cm strips from the middle of the blades to ensure blade development was consistent. If tissues were taken closer to the pneumatocyst, this would indicate the younger development and if tissues were collected near the end of the blade, then the tissues would be the oldest part and could contain reproductive tissues (spore-packets/sori). We briefly soaked the cut blades in an iodine-filtered seawater solution (1:9 iodine at 1-µm filtered and UV sterilized seawater) before the blades in 38.48 × 20.32-cm glass Pyrex dishes filled with filtered seawater (1-µm filtered and UV sterilized seawater).

2.2 Laboratory acclimation setup

Following published methods (Hernández-Carmona et al. 2006; Karm 2023), the cut vegetative bull kelp blades were acclimated at two seawater temperatures by placing them in seawater tables already set to 13 °C-ambient (control) and 17 °C-elevated (warm). The elevated treatment was meant to mimic the warming effect caused by the Blob (Di Lorenzo and Mantua 2016), while the ambient temperature represented the average seawater temperature experienced by bull kelp at the collection sites during non-warming events. We used a temperature-controlled environmental room at the University of California, Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory (USA) for running the acclimation experiments. Four seawater tables (251 × 83 × 23 cm) were used for the acclimation treatment due to limited space in the environmental room: two were held at 13 °C and the other two at 17 °C. We maintained the two ambient seawater tables by setting the room air temperature to 13 °C, and put two heaters (TT-1000, JBJ, Tampa, FL, USA) into each of the warm (17 °C) seawater tables to elevate the water temperature (Karm 2023). To prevent localized warm spots, we circulated the seawater in all the seawater tables with small air pumps (1800 L/H Water Pump, Vivosun, Ontario, CA, USA). We affixed two wide-spectrum LED grow lights, covered with garden screens, above each seawater table to provide UV light for the kelp to photosynthesize. These lights were set on a 12-h timer to mimic the average day/night cycle the kelp would experience in the field during spring. We monitored irradinace from the UV lamps using photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) and maintained at a level of 18–20 μmol m−2 s−1 (Graham and Hamilton 2023; Karm 2023; Supratya and Martone 2024). We logged seawater temperature inside the seawater tables during the acclimation period using iButtons loggers (data not shown; Dallas Maxim, Dallas, Texas, USA) recording every 40 min. The average temperature for the elevated treatment seawater tables was recorded at 17.0 ± 0.71 °C (referred to as 17 °C) and the average temperature for the ambient treatment was 12.9 ± 0.80 °C (referred to as 13 °C). The minimum temperature recorded for the ambient treatment was 12.3 °C and 16.5 °C for the warm treatment; whereas the maximum temperature recorded for the ambient treatment was 13.5 °C and 17.5 °C for the warm treatment. We randomly placed the Pyrex dishes in the seawater tables in each acclimation treatment and rotated them randomly every other day to prevent a tank effect. The seawater in the Pyrex dishes with the sporophytes was filtered through two different micron filters – 10 µm filter (FP110, iSpring, Cumming, GA, USA) and 0.5 µm filter (CBC-10, Pentair Inc, Minneapolis, MN USA), then UV sterilized (JUVC-55, Jebao, Northport, NY, USA). Every other day, we changed the filtered seawater with the sporophytes and treated it with 20 µl of germanium dioxide (20 µl of germanium dioxide per liter of seawater) to help minimize diatom growth (Karm 2023; Shea and Chopin 2007). The sporophytes were acclimated for a total 7 days; any longer would have resulted in tissue degradation as bull kelp cannot continue to photosynthesize much past 7 days post-removal from the main stipe (personal observation, Brent Hughes).

2.3 Heat shock treatment

After 7 days of acclimation, we removed the sporophyte blades from the seawater tables and subjected them to an acute 1-h heat shock treatment. An aluminum heat block with a heater and chiller connected to each side was used to create a temperature gradient for the heat shock session. Each individual bull kelp blade was cut into ten 2.54-cm sections, each piece placed in a 5-ml microcentrifuge tube filled with filtered seawater (20-µm), and heat shocked for 1 h at the following temperatures: 13, 17, 20, 23, and 26 °C. We chose these temperatures as they reflect our ambient and elevated acclimation temperatures (13 and 17 °C), and three warmer temperatures that would be above the lethal limit for bull kelp (Luning and Freshwater 1988). After incubation, we removed the bull kelp blade pieces from the 5-ml microcentrifuge tubes and flash-froze them on dry ice until further analysis.

2.4 Protein extraction and quantification

We mechanically ground the frozen kelp tissue samples into a fine powder using a liquid nitrogen-cooled mini mortar (SP Bel-Art, Warminster, PA, USA) and a pestle. We suspended the powdered kelp in 1 ml of extraction buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 % glycerin, 1 % Triton X-100; 1 mM of 1 M dithiothreitol stock solution; Hammann et al. 2016) and incubated the samples in microcentrifuge tubes on a shaker at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, we centrifuged the samples (13,000g at 4 °C for 2 min) and collected the supernatant. We determined the total protein concentration (µg µl−1) of the extracted samples using a bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard and ran a Coomassie-based Bradford protein assay according to the manufacturer instructions (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.5 SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and chemiluminescence

We separated the bull kelp proteins from extracted samples by molecular weight (kDa) using SDS-PAGE mini protean gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). We loaded each kelp sample in equal amounts (30 µg) and ran the samples in duplicate. The samples loaded to each gel were arranged randomly. We also loaded a Hsp70 positive control sample (0.0375 pmol μl−1; Agrisera Antibodies, Sweden) on each gel for confirmation of appropriate protein size (image not shown). We ran each gel at 100 V in running buffer (25 mM Tris-base pH 8.4, Glycine 192 mM, 0.1 % SDS at room temperature) and then transferred them onto on nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Protran 0.45 µm NC, Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA, USA) for 1 h at 100 V in chilled transfer buffer (25 mM Tris-base pH 8.4, Glycine 192 mM, 10 % methanol). We washed the protein bound membranes in 1× TBS buffer (tris-buffered saline; 20 mM Tris-base, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl) for 5 min at room temperature on an orbital shaker (Belly Dancer, IBI Scientific, Dubuque, IA, USA), then heat-fixed the membranes at 37 °C and stored them in the dark at room temperature until further analysis.

We blocked each protein bound nitrocellulose membranes in 5 % nonfat dried milk block solution (with 1× TBS) for 1 h at room temperature on the orbital shaker, then washed the membranes three times in a mild detergent solution (1× TBS plus 0.1 % Tween-20) for 5 min at room temperature. We then incubated an Hsp70 primary antibody (AS08 371; Agrisera Antibodies- made from Arabidopsis thaliana, Sweden, 1:3,000 dilution) with the nitrocellulose membranes for 1 h at room temperature.

We then washed the membranes three times in 1× TBS plus 0.1 % Tween buffer for 5 min at room temperature, before adding the secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP conjugated; 1:2,500 dilution; Agrisera Antibodies, Sweden) to the membranes and incubated them for 1 h at room temperature. The last series of washes were completed once the secondary incubation was concluded: 1× TBS plus 0.1 % Tween – three times for 5 min, 1× TBS plus 0.3 % Tween-three times for 5 min, and 1× TBS-once for 5 min (at room temperature). We incubated the nitrocellulose paper membrane in SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Petaluma, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, then imaged the membranes using an Odyssey XF Imager (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

It is important to note that while this antibody has been designed to bind to the inducible Hsp70 protein isoform in a plant species, it has not been previously tested in bull kelp before this experiment. Thus, we cannot strictly say if the antibody is detecting only the inducible or constitutive form of Hsp70 in bull kelp. Therefore, out of an abundance of caution, we refer to Hsp70 protein as “total” Hsp70 protein from this point forward to include both the inducible and constitutive form.

2.6 Statistical analysis

We analyzed the total Hsp70 protein abundance for each bull kelp sample using ImageJ to determine relative light units (RLU) of the protein bands. These units are arbitrary and do not provide protein concentration, but rather a quantified analysis of protein density or abundance. The darker the band, the more total Hsp70 protein present and vice versa. We ran each sample in duplicate, subtracted the RLU from a blank well to account for any background correction, standardized the RLU using the positive control to compare across blots, and averaged together the RLU to provide one value per heat shock temperature for each sporophyte sample for each acclimation treatment.

We ran all statistical analysis using JMP® Pro 17 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) by testing both the total Hsp70 protein abundance raw data and residual data for normality and homoscedasticity. After visual confirmation and running both the Shapiro–Wilk (raw data: w = 0.98, p = 0.08; residual data: w = 0.99, p = 0.98) and the Anderson-Darling Goodness-of-Fit tests (raw data: a2 = 0.56, p = 0.16; residual data: a2 = 0.16, p = 0.95) the data passed normality; therefore, no transformation or normalization was needed. We used a full-factorial linear mixed model to analyze the data with individual kelp sporophyte as a random variable using restricted maximum likelihood (REML). Acclimation temperature, collection site, and heat shock temperature were fixed categorical factors, and total Hsp70 protein abundance was the numeric response variable in the model. The three-way and two-way interactions were assessed in the model (Table 1) with any significant differences (p-value <0.05) analyzed using post-hoc Student t-tests.

Results of linear mixed model statistical analysis.

| Independent variable | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site | 1 | 4.85 | 0.058a |

| Acclimation temp | 1 | 7.32 | 0.009b |

| Heat shock temp | 4 | 0.74 | 0.565 |

| Site × acclimation temp | 1 | 1.88 | 0.173 |

| Site × heat shock temp | 4 | 0.46 | 0.761 |

| Acclimation temp × heat shock temp | 4 | 0.55 | 0.698 |

| Site × acclimation temp × heat shock temp | 4 | 1.36 | 0.254 |

-

aDenotes marginal significance. bDenotes statistical significance.

3 Results

There was a significant difference in total Hsp70 protein abundance between sporophytes acclimated to the ambient seawater temperature compared to those acclimated to the warmer seawater temperature (F1,72 = 7.32, p = 0.009; Figure 2A). Specifically, sporophytes acclimated to 17 °C exhibited 20.2 % greater protein abundance than those acclimated to 13 °C, with 14 % of the variability due to the random effect of individual bull kelp sporophytes (Wald p-value = 0.19). These results suggest that the bull kelp acclimated to the warmer temperature mounted a stronger response to the short-term temperature change, while sporophytes acclimated to the ambient temperature had a lower response.

Bull kelp sporophyte Hsp70 total protein abundance. Hsp70 protein abundance is represented as relative light units (RLU) on the y-axis with (A) acclimation temperature (°C) and (B) collection site on the x-axis. The asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference (p = 0.009) while the dagger (†) denotes a marginal significance (p = 0.058). Box plot values represent the means ± SEM of Hsp70 protein abundance from the sporophytes (n = 10) for each collection site and acclimation temperature, with the middle line representing the median protein abundance and the dots indicating outliers in the dataset.

Collection site had a marginal difference in total Hsp70 protein abundance between sporophytes collected from Big River and those collected from Russian Gulch (Figure 2B). Specifically, sporophytes from Russian Gulch exhibited approximately 22 % more Hsp70 protein abundance than those from Big River (F1,8 = 4.85, p = 0.058), with 6.6 % of the variability due to the random effect of individual bull kelp sporophytes (Wald p-value = 0.41). These results would suggest that the sporophytes from the southern site of Russian Gulch mounted a greater heat shock response than those sporophytes from the northern site of Big River.

Total Hsp70 protein abundance did not differ between any of the heat shock temperatures (F4,72 = 0.74, p = 0.565; Figure 3), and none of the interactions between collection site, acclimation treatment, and heat shock temperature were significant (Table 1).

Bull kelp Hsp70 total protein abundance compared across different heat shock temperatures, sites, and acclimation treatments: sporophytes from two collection sites (Big River = BR, Russian Gulch = RG) were acclimated to 13 °C (AC13) and 17 °C (AC17) for 7 days. Hsp70 protein abundance is represented as relative light units (RLU) on the y-axis with heat shock temperature (°C) on the x-axis. Box plot values represent the means ± SEM of Hsp70 protein abundance for the sporophytes (n = 5) at each heat shock temperature, with the middle line representing the median protein abundance. No significant interactions were detected in any of the interactions.

4 Discussion and conclusion

This study demonstrates that temperature is one factor that can drive the heat shock response in N. luetkeana, but we recognize that organisms such as bull kelp living in a dynamic and changing environments are likely impacted by other stressors that could play a role in an organism’s physiological response to thermal stress that were not tested in our study. For example, the microbiome community associated with specific kelp species ((golden kelp- Ecklonia radiata; Vadillo Gonzalez et al. 2024; Veenhof et al. 2025) and (giant kelp- Macrocystis pyrifera; Minich et al. 2018)) have shown to impact thermal tolerance at specific stages. However, our study suggests acclimation temperature and/or thermal history (Collins et al. 2020; Tomanek 2010) are important factors that can influence the heat shock response of bull kelp.

The warmer-acclimated bull kelp had 20 % more total Hsp70 protein abundance compared to the ambient-acclimated kelp (Figure 2A) irrespective of collection site. It has been well documented that a strong HSR can occur when marine organisms are acclimated to warmer water (Tomanek and Somero 1999, 2002 – marine snails; Lewis et al. 2016 – salmonids; Hereward et al. 2020; King et al. 2019 – oarweed), which could be because growth temperature, or the temperature of the environment the organism germinated or developed in, has been known to affect the plasticity of the HSR in most organisms, especially sessile ones (Barua et al. 2003). An organism that inhabits warmer temperatures or faces frequent heatwaves is likely to experience repeated triggering of the HSR over the course of its life, resulting in an increase in the base level of the inducible isoform within the cytosol (Maloyan et al. 1999). The buildup of heat shock proteins in the cytosol provides greater support for protein folding, leading to a delay in the HSR being triggered (King et al. 2019). As a result, the higher the acclimation temperature, the greater the available pool of heat shock proteins (Craig and Gross 1991; Henkel and Hofmann 2009) and thus the need to trigger the HSR to deal with any misfolded proteins is lessened. The warmer acclimation temperature (of 17 °C) was meant to mimic the marine heatwave conditions of the Blob (Di Lorenzo and Mantua 2016), thus, to capture the physiological response of bull kelp during an artificial warming event. Warmer temperatures are known to increase the half-life of inducible Hsp70 proteins from 2 to 7 h, therefore increasing the likelihood of the inducible form being present in the cytosol at a given time, especially during the heat shock session (Duncan and Hershey 1989). Though we were not able to distinguish between the two isoforms of Hsp70, it is conceivable that the warm-acclimated kelp might have a greater abundance of the inducible isoform because the sporophytes were being subjected to conditions similar to a week-long heatwave, and at a temperature that has shown to be the thermal limit for bull kelp (Contolini et al. 2021; Coppin et al. 2020; Supratya et al. 2020; Wheeler et al. 1984), therefore adding to the increase in total Hsp70 protein abundance (Tomanek and Somero 2002). The difference we see in protein abundance between the two acclimation temperatures suggests that the acclimation period of seven days appears to have been enough time to build a sufficient “pool” of heat shock proteins in the cytosol for sporophytes acclimated at 17 °C, and that the warmer acclimated kelp had built up a stock of Hsp70 protein to deal with these heatwave-like conditions (Henkel and Hofmann 2008b). This could represent a snapshot of the state of the cells at the time of the event (Mahmood and Yang 2012). The differences we saw between collection sites is further evidence for the effect of thermal history on the HSR for Nereocystis (Buckley et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2024), however we are aware other factors could be impacting bull kelp’s physiological response not tested in this study.

We were surprised to find that there was no significant difference in Hsp70 protein abundance when bull kelp was subjected to the 1-h heat shock (Figure 3), considering studies have defined a ‘typical’ HSR as a bell-curve (Kellermann et al. 2019; Schulte et al. 2011) when exposed to acute thermal stress. It is common for Hsp70 protein abundance to start low when temperatures are close to ambient, and not stressful for the organism, then rise as temperature increases to a critical threshold, after which protein abundance decreases as temperature continues to warm (Tomanek and Somero 1999). Previous studies on other species of marine algae displayed a HSR during acute heat shock sessions after anywhere from 4 h to 2 weeks of acclimation (Henkel and Hofmann 2008a; Ireland et al. 2004; King et al. 2019). A possibility for the lack of a ‘typical’ HSR in our study could be due to the specificity of the primary antibody used in the study, such that it could not distinguish the difference between the constitutive and inducible isoforms in bull kelp. To the best of our knowledge, and with multiple troubleshooting, we were not able to find an inducible (only) antibody that would work on bull kelp tissues. Therefore, our results are more conservative by taking the sum of constitutive and inducible isoforms together (calling it total Hsp70 protein) since we cannot definitively determine whether the antibody is binding to the inducible form only. Fortunately, data supports that the combination of both constitutive and inducible Hsp70 isoforms is still an effective way to measure stress for an organism (Giudice et al. 1999; Ireland et al. 2004; Lindquist 1986; Mayer and Bukau 2005), but we understand that our results may be underestimating the true response of bull kelp in our study.

There is also the question of whether the acclimation period itself influenced the lack of difference we saw in HSR during the heat shock session. We saw a difference after a 7-day acclimation, wherein the kelp acclimated at 17 °C had greater protein abundance than kelp acclimated at 13 °C. But we did not see a difference between either the acclimation groups or the different heat shock temperatures (within or between acclimation groups) during an hour in the face of an acute heat shock event. A possible explanation for this could lie in the nature of the HSR itself as it is an energetically costly process that operates on a negative feedback loop (Angilletta 2009; Brown et al. 1993; Feder and Hofmann 1999; Krebs and Loeschcke 1994); therefore, it has a threshold of activation, maintenance, and deactivation (Currie et al. 2014; Krakowiak et al. 2018). It could be that the sporophytes acclimated to 17 °C were stressed enough over the course of the week to mount a HSR, while those acclimated to 13 °C were not; hence the general difference we saw between the two groups. The warm-acclimated sporophytes could have been too stressed at the end of the week to mount any greater of a HSR when subjected to an additional heat shock session. However, we were surprised to find that there was a lack of significant difference in Hsp70 protein abundance between heat shock temperatures. Previous studies have shown the HSR can be both immediate and delayed depending on factors such as length of exposure, depth, or location (Henkel and Hofmann 2008a; Ireland et al. 2004; King et al. 2019). Sometimes different subspecies within a shared genus (Clusella-Trullas et al. 2014; Serafini et al. 2011; Tomanek and Somero 1999) can produce a different heat shock response. Unfortunately, the lack of a heat shock response cannot be explained as this time. But it is possible producing more Hsp70 proteins could have been too energetically expensive by the end of a week at 17 °C or conversely, the ambient-acclimated sporophytes might also not have been stressed enough by the acute heat shock to produce more Hsp70 proteins.

Since this is the first time such an experiment has been attempted with this species, further investigation would benefit to help understand the lack of conclusive results with heat shock. One suggestion might be to collect bull kelp from more southern and northern sites along its range as this could provide more insight into the HSR of Hsp70 due to specific geographical variations (Helmuth et al. 2002), while also identifying the effects of increased warming events (Smale 2020). This could illustrate a more complete picture in the HSR by suggesting if some southern populations of bull kelp are more thermally tolerant than others by acclimatizing better (Harley et al. 2006) or if further northern populations of bull kelp (e.g., Washington or Alaska) are more thermally sensitive and delay the activation of their HSR until temperatures are warmer (King et al. 2019).

Overall, these data suggest that an organism’s thermal history can affect the HSR to short-term temperature changes, which means it is the specific temperatures the organism and those within its community and population experience during their lives that may determine how they respond to a short heating event. For example, a recent study found that different bull kelp populations within California showed a differential effect on abundance, length, and development when reared at warmer temperatures (Fattori 2024). This emphasizes the importance of an organisms’ ability to locally acclimatize, especially as marine heatwave occurrences become more frequent, and how these perturbations could affect not only the same species across a wide range of habitats but also their impacts on local community-level biodiversity (Oliver et al. 2019, 2021). Conducting future acclimation studies, especially those at the molecular level, has the potential to build a comprehensive prediction on which organisms in what populations could tolerate and survive future heatwave events, and which may not (Somero 2010).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the faculty and staff at UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab (Dr. Brian Gaylord, Albert Carranza, and Phillip Smith) for use of their facility and assistance with this project. We appreciate the endless hours and effort Zachary Spade assisted with in maintaining the bull kelp acclimation tanks. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Daniel Crocker for his assistance with the statistical analysis, Dr. Joseph Lin for helping to preserve some of the SDS-PAGE gels, and Dr. Lisa Bentley for her assistance in providing comments for this manuscript. Also, we appreciate all the help from former undergraduate students, Maxim Kulinich, Jasmine Richardson, and Francisco Elias, for their assistance on tank husbandry and protein extractions. We also would like to thank Hughes lab members Abbey Dias, Julieta Gómez, Vini Souza, and María Velázquez for their part in collecting sporophyte blades and setup of the acclimation experiment over the course of this study. Preparation of this manuscript was partially supported by Sonoma State University through the Koret Foundation awarded to S.J.H., and the Anthropocene Institute, and California Sea Grant awarded to M.L.Z and B.B.H.

-

Research ethics: Bull kelp collection and cultivation was permitted under the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (permit S-190060001-20113-001).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained by all individuals/authors for this publication.

-

Author contributions: SJH: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, validation, drafted original writing, edited and reviewed writing, accountability for aspects of work is accurate. RHK: methodology, review and editing of writing. BBH: funding acquisition, conceptualization, methodology, review and editing of writing. MLZ: funding acquisition, conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, resources, writing- editing and reviewing of writing, accountability for aspects of work is accurate, supervisor, approval for publication. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors do not have any competing interests for the publication of this article.

-

Research funding: Preparation of this manuscript was partially supported by Sonoma State University through the Koret Foundation awarded to S.J.H., the Anthropocene Institute and California Sea Grant awarded to M.L.Z and B.B.H.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Adham, K.G., Wilkinson, M.C., Smith, C.J., and Laidman, D.L. (1991). An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for heat-shock protein 70 in plants. Food Agric. Immunol. 3: 29–36, https://doi.org/10.1080/09540109109354727.Search in Google Scholar

Angilletta, M.J.Jr. (2009). Thermal adaptation: a theoretical and empirical synthesis, online ed. Oxford: Oxford Academic.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198570875.001.1Search in Google Scholar

Barua, D., Downs, C.A., and Heckathorn, S.A. (2003). Variation in chloroplast small heat-shock protein function is a major determinant of variation in thermotolerance of photosynthetic electron transport among ecotypes of Chenopodium album. Funct. Plant Biol. 30: 1071–1079, https://doi.org/10.1071/FP03106.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Beisner, B.E., Haydon, D.T., and Cuddington, K. (2003). Alternative stable states in ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 1: 376–382, https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2003)001[0376:assie]2.0.co;2.10.1890/1540-9295(2003)001[0376:ASSIE]2.0.CO;2Search in Google Scholar

Boer, G. and Yu, B. (2003). Climate sensitivity and response. Clim. Dyn. 20: 415–429, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-002-0283-3.Search in Google Scholar

Bond, N.A., Cronin, M.F., Freeland, H., and Mantua, N. (2015). Causes and impacts of the 2014 warm anomaly in the NE Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42: 3414–3420, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015gl063306.Search in Google Scholar

Brokordt, K.B., González, R.C., Farías, W.J., and Winkler, F.M. (2015). Potential response to selection of HSP70 as a component of innate immunity in the abalone Haliotis rufescens. PLoS One 10, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141959.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, C.R., Martin, R.L., Hansen, W.J., Beckmann, R.P., and Welch, W.J. (1993). The constitutive and stress inducible forms of hsp70 exhibit functional similarities and interact with one another in an ATP-dependent fashion. J. Cell Biol. 120: 1101–1112, https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.120.5.1101.Search in Google Scholar

Buckley, B.A., Owen, M.E., and Hofmann, G.E. (2001). Adjusting the thermostat: the threshold induction temperature for the heat-shock response in intertidal mussels (genus Mytilus) changes as a function of thermal history. J. Exp. Biol. 204: 3571–3579, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.204.20.3571.Search in Google Scholar

Camarena-Novelo, I., Salazar-Campos, Z., Botello, A.V., Villanueva-Fragoso, S., Jiménez-Morales, I., Fierro, R., and González-Márquez, H. (2019). Potential of the HSP70 protein family as biomarker of Crassostrea virginica under natural conditions (Ostreoida: Ostreidae). Rev. Biol. Trop. 67: 572–584, https://doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v67i3.33048.Search in Google Scholar

Catton, C., Rogers-Bennett, L., and Amrhein, A. (2016). “Perfect Storm” decimates northern California kelp forests. California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Available at: https://cdfwmarine.wordpress.com/2016/03/30/perfect-storm (Accessed 16 July 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Clusella-Trullas, S., Boardman, L., Faulkner, K.T., Peck, L.S., and Chown, S.L. (2014). Effects of temperature on heat-shock responses and survival of two species of marine invertebrates from sub-Antarctic Marion Island. Antarct. Sci. 26: 145–152, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954102013000473.Search in Google Scholar

Collins, C.L., Burnett, N.P., Ramsey, M.J., Wagner, K., and Zippay, M.L. (2020). Physiological responses to heat stress in an invasive mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis depend on tidal habitat. Mar. Environ. Res. 154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2019.104849.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Contolini, G., Flores-Miller, R., and Ray, J. (2021). Giant kelp and bull kelp, Macrocystis pyrifera and Nereocystis luetkeana, Enhanced status report. California Department of Fish and Wildlife.Search in Google Scholar

Coppin, R., Rautenbach, C., Ponton, T.J., and Smit, A.J. (2020). Investigating waves and temperature as drivers of kelp morphology. Front. Mar. Sci. 7: 567, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00567.Search in Google Scholar

Craig, E.A. and Gross, C.A. (1991). Is hsp70 the cellular thermometer? Trends Biochem. Sci. 16: 135–140, https://doi.org/10.1016/0968-0004(91)90055-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Currie, S., Schulte, P.M., and Evans, D.H. (2014). Thermal stress. In: Evans, D.H., Claiborne, J.B., and Currie, S. (Eds.). The physiology of fishes, 4th ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp. 257–279.Search in Google Scholar

Di Lorenzo, E. and Mantua, N. (2016). Multi-year persistence of the 2014/15 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat. Clim. Change 6: 1042–1047, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3082.Search in Google Scholar

Dobkowski, K.A. and Crofts, S.B. (2021). Scaling and structural properties of juvenile bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana). Integr. Org. Biol. 3, https://doi.org/10.1093/iob/obab022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Duncan, R.F. and Hershey, J.W. (1989). Protein synthesis and protein phosphorylation during heat stress, recovery, and adaptation. J. Cell Biol. 109: 1467–1481, https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.109.4.1467.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ellison, A.M. (2019). Foundation species, non-trophic interactions, and the value of being common. iScience 13: 254–268, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.02.020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Fan, X., Xu, D., Wang, D., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., and Ye, N. (2020). Nutrient uptake and transporter gene expression of ammonium, nitrate, and phosphorus in Ulva linza: adaption to variable concentrations and temperatures. J. Appl. Phycol. 32: 1311–1322, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-020-02050-2.Search in Google Scholar

Fattori, M. (2024). Temperature driven variability in bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) early life stages: a comparative study of California populations, Master’s thesis. Humboldt, California State Polytechnic University.Search in Google Scholar

Feder, M.E. and Hofmann, G.E. (1999). Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: evolutionary and ecological physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 61: 243–282, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Flato, G.M. and Boer, G.J. (2001). Warming asymmetry in climate change simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28: 195–198, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000gl012121.Search in Google Scholar

Fujita, R. (2013). 5 ways climate change affecting our oceans. Environmental Defense Fund, Available at: www.edf.org/blog/2013/10/08/5-ways-climate-change-affecting-our-oceans (Accessed 16 July 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Galland, G., Harrould-Kolieb, E., and Herr, D. (2012). The ocean and climate change policy. Clim. Policy 12: 764–771, https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2012.692207.Search in Google Scholar

Giudice, G., Sconzo, G., and Roccheri, M.C. (1999). Studies on heat shock proteins in sea urchin development. Dev. Growth Differ. 41: 375–380, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-169x.1999.00450.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Graham, M. and Hamilton, S. (2023). Assessment of practical methods for re-establishment of northern California bull kelp populations at an ecologically relevant scale. California Sea Grant.Search in Google Scholar

Hammann, M., Wang, G., Boo, S.M., Aguilar-Rosas, L.E., and Weinberger, F. (2016). Selection of heat-shock resistance traits during the invasion of the seaweed Gracilaria vermiculophylla. Mar. Biol. 163: 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-016-2881-3.Search in Google Scholar

Hara, Y., Otake, Y., Akita, S., Yamazaki, T., Takahashi, F., Yoshikawa, S., and Shimada, S. (2022). Gene expression of a canopy-forming kelp, Eisenia bicyclis (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae), under high temperature stress. Phycol. Res. 70: 203–211, https://doi.org/10.1111/pre.12497.Search in Google Scholar

Harley, C.D., Randall-Hughes, A., Hultgren, K.M., Miner, B.G., Sorte, C.J., Thornber, C.S., Williams, S.L., and Tomanek, L. (2006). The impacts of climate change in coastal marine systems. Ecol. Lett. 9: 228–241, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00871.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Helmuth, B., Harley, C.D., Halpin, P.M., O’Donnell, M., Hofmann, G.E., and Blanchette, C.A. (2002). Climate change and latitudinal patterns of intertidal thermal stress. Science 298: 1015–1017, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1076814.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Henkel, S.K. and Hofmann, G.E. (2008a). Differing patterns of hsp70 gene expression in invasive and native kelp species: evidence for acclimation-induced variation. J. Appl. Phycol. 20: 915–924, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-007-9275-3.Search in Google Scholar

Henkel, S.K. and Hofmann, G.E. (2008b). Thermal ecophysiology of gametophytes cultured from invasive Undaria pinnatifida (Harvey) Suringar in coastal California harbors. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 367: 164–173, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2008.09.010.Search in Google Scholar

Henkel, S. and Hofmann, G. (2009). Interspecific and interhabitat variation in hsp70 gene expression in native and invasive kelp populations. Mar. Ecol.: Prog. Ser. 386: 1–13, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08047.Search in Google Scholar

Hereward, H.F., King, N.G., and Smale, D.A. (2020). Intra-annual variability in responses of a canopy forming kelp to cumulative low tide heat stress: implications for populations at the trailing range edge. J. Phycol. 56: 146–158, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.12927.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hernández-Carmona, G., Hughes, B., and Graham, M.H. (2006). Reproductive longevity of drifting kelp Macrocystis pyrifera (Phaeophyceae) in Monterey Bay, USA 1. J. Phycol. 42: 1199–1207, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00290.x.Search in Google Scholar

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. and Bruno, J.F. (2010). The impact of climate change on the world’s marine ecosystems. Science 328: 1523–1528, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1189930.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hofmann, G.E. (1999). Ecologically relevant variation in induction and function of heat shock proteins in marine organisms. Am. Zool. 39: 889–900, https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/39.6.889.Search in Google Scholar

Hofmann, G.E. (2005). Patterns of Hsp gene expression in ectothermic marine organisms on small to large biogeographic scales. Integr. Comp. Biol. 45: 247–255, https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/45.2.247.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hu, C., Yang, J., Qi, Z., Wu, H., Wang, B., Zou, F., Liu, Q., and Liu, J. (2022). Heat shock proteins: biological functions, pathological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. MedComm 3, https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.161.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ireland, H.E., Harding, S.J., Bonwick, G.A., Jones, M., Smith, C.J., and Williams, J.H. (2004). Evaluation of heat shock protein 70 as a biomarker of environmental stress in Fucus serratus and Lemna minor. Biomarkers 9: 139–155, https://doi.org/10.1080/13547500410001732610.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Jueterbock, A., Kollias, S., Smolina, I., Fernandes, J.M., Coyer, J.A., Olsen, J.L., and Hoarau, G. (2014). Thermal stress resistance of the brown alga Fucus serratus along the North-Atlantic coast: acclimatization potential to climate change. Mar. Genomics 13: 27–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margen.2013.12.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Karm, R. (2023). Warming resistance of bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) at its southern range limit, Master’s thesis, Sonoma State University.Search in Google Scholar

Kellermann, V., Chown, S.L., Schou, M.F., Aitkenhead, I., Janion-Scheepers, C., Clemson, A., Sgrò, C.M., and Sgrò, C.M. (2019). Comparing thermal performance curves across traits: how consistent are they? J. Exp. Biol. 222, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.193433.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kenyon, K.E. (1999). North Pacific high: a hypothesis. Atmos. Res. 51: 15–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-8095(98)00110-0.Search in Google Scholar

King, N.G., McKeown, N.J., Smale, D.A., Wilcockson, D.C., Hoelters, L., Groves, E.A., and Moore, P.J. (2019). Evidence for different thermal ecotypes in range centre and trailing edge kelp populations. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 514: 10–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2019.03.004.Search in Google Scholar

Korabik, A.R., Winquist, T., Grosholz, E.D., and Hollarsmith, J.A. (2023). Examining the reproductive success of bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana, Phaeophyceae, Laminariales) in climate change conditions. J. Phycol. 59: 989–1004, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.13368.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kortsch, S., Primicerio, R., Fossheim, M., Dolgov, A.V., and Aschan, M. (2015). Climate change alters the structure of arctic marine food webs due to poleward shifts of boreal generalists. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 282, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.1546.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Krakowiak, J., Zheng, X., Patel, N., Feder, Z.A., Anandhakumar, J., Valerius, K., Gross, D.S., Khalil, A., and Pincus, D. (2018). Hsf1 and Hsp70 constitute a two-component feedback loop that regulates the yeast heat shock response. eLife 7, https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.31668.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Krebs, R.A. and Loeschcke, V. (1994). Costs and benefits of activation of the heat-shock response in Drosophila melanogaster. Funct. Ecol. 8: 730–737, https://doi.org/10.2307/2390232.Search in Google Scholar

Krivoruchko, A. and Storey, K.B. (2010). Forever young: mechanisms of natural anoxia tolerance and potential links to longevity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 3: 186–198, https://doi.org/10.4161/oxim.3.3.12356.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Leising, A.W., Schroeder, I.D., Bograd, S.J., Abell, J., Durazo, R., Gaxiola-Castro, G., Bjorkstedt, E.P., Field, J., Sakuma, K., Roberston, R.R., et al.. (2015). State of the California Current 2014–15: impacts of the warm-water “Blob”. Calif. Coop. Ocean. Fish. Investig. Rep. 56: 31–68.Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, M., Götting, M., Anttila, K., Kanerva, M., Prokkola, J.M., Seppänen, E., and Nikinmaa, M. (2016). Different relationship between hsp70 mRNA and hsp70 levels in the heat shock response of two salmonids with dissimilar temperature preference. Front. Physiol. 7: 511, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00511.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lindquist, S. (1986). The heat-shock response. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 55: 1151–1191, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.55.1.1151.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, F., Zhang, P., Liang, Z., Wang, W., Sun, X., and Wang, F. (2019). Dynamic profile of proteome revealed multiple levels of regulation under heat stress in Saccharina japonica. J. Appl. Phycol. 31: 3077–3089, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-019-01813-w.Search in Google Scholar

Luning, K. and Freshwater, W. (1988). Temperature tolerance of northeast pacific marine algae. J. Phycol. 24: 310–515, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8817.1988.tb00178.x.Search in Google Scholar

Mahmood, T. and Yang, P.C. (2012). Western blot: technique, theory, and trouble shooting. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 4: 429–434, https://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.100998.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Makwana, K., Parmar, H.L., Sikotariya, H., Biswas, S., and Bhadarka, M.A. (2024). Review on climate change impacts on marine ecosystems: from ocean dynamics to biodiversity loss. Agrigate 4: 160–166.Search in Google Scholar

Maloyan, A., Palmon, A., and Horowitz, M. (1999). Heat acclimation increases the basal HSP72 level and alters its production dynamics during heat stress.Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 276, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.r1506.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mayer, M.P. and Bukau, B. (2005). Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62: 670–684, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-004-4464-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Minich, J.J., Morris, M.M., Brown, M., Doane, M., Edwards, M.S., Michael, T.P., and Dinsdale, E.A. (2018). Elevated temperature drives kelp microbiome dysbiosis, while elevated carbon dioxide induces water microbiome disruption. PLoS One 13, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192772.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Muth, A.F., Graham, M.H., Lane, C.E., and Harley, C.D.G. (2019). Recruitment tolerance to increased temperature present across multiple kelp clades. Ecology 100, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2594.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Oliver, E.C., Burrows, M.T., Donat, M.G., Sen Gupta, A., Alexander, L.V., Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.E., Smale, D.A., Hobday, A.J., Holbrook, N.J., Moore, P.J., et al.. (2019). Projected marine heatwaves in the 21st century and the potential for ecological impact. Front. Mar. Sci. 6: 734, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00734.Search in Google Scholar

Oliver, E.C., Benthuysen, J.A., Darmaraki, S., Donat, M.G., Hobday, A.J., Holbrook, N.J., and Sen Gupta, A. (2021). Marine heatwaves. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 13: 313–342, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-032720-095144.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Peterson, W.T., Fisher, J.L., Strub, P.T., Du, X., Risien, C., Peterson, J., and Shaw, C.T. (2017). The pelagic ecosystem in the Northern California Current off Oregon during the 2014–2016 warm anomalies within the context of the past 20 years. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122: 7267–7290, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017jc012952.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Place, S.P., Zippay, M.L., and Hofmann, G.E. (2004). Constitutive roles for inducible genes: evidence for the alteration in expression of the inducible hsp70 gene in Antarctic notothenioid fishes. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 287, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00223.2004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Reed, D., Washburn, L., Rassweiler, A., Miller, R., Bell, T., and Harrer, S. (2016). Extreme warming challenges sentinel status of kelp forests as indicators of climate change. Nat. Commun. 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13757.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Reed, D.C., Schmitt, R.J., Burd, A.B., Burkepile, D.E., Kominoski, J.S., McGlathery, K.J., Zinnert, J.C., and Morris, J.T. (2022). Responses of coastal ecosystems to climate change: insights from long-term ecological research. BioScience 72: 871–888, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biac006.Search in Google Scholar

Rogers-Bennett, L. and Catton, C.A. (2019). Marine heat wave and multiple stressors tip bull kelp forest to sea urchin barrens. Sci. Rep. 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51114-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ryan, J.A. and Hightower, L.E. (1999). Heat shock proteins: molecular biomarkers of effects. In: Paga, A. and Wallace, K.N. (Eds.). Molecular biology of the toxic response. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia, pp. 449–466.Search in Google Scholar

Schulte, P.M., Healy, T.M., and Fangue, N.A. (2011). Thermal performance curves, phenotypic plasticity, and the time scales of temperature exposure. Integr. Comp. Biol. 51: 691–702, https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icr097.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Serafini, L., Hann, J.B., Kültz, D., and Tomanek, L. (2011). The proteomic response of sea squirts (genus Ciona) to acute heat stress: a global perspective on the thermal stability of proteins. Comp. Biochem. Physiol., Part D: Genomics Proteomics 6: 322–334, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbd.2011.07.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Shea, R. and Chopin, T. (2007). Effects of Germanium dioxide, an inhibitor of diatom growth, on the microscopic laboratory cultivation stage of the kelp, Laminaria saccharina. J. Appl. Phycol. 19: 27–32, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-006-9107-x.Search in Google Scholar

Smale, D.A. (2020). Impacts of ocean warming on kelp forest ecosystems. New Phytol. 225: 1447–1454, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16107.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Smale, D.A., Wernberg, T., Oliver, E.C., Thomsen, M., Harvey, B.P., Straub, S.C., Moore, P.J., Alexander, L.V., Benthuysen, J.A., Donat, M.G., et al.. (2019). Marine heatwaves threaten global biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services. Nat. Clim. Change 9: 306–312, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0412-1.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, K.E., Burrows, M.T., Hobday, A.J., King, N.G., Moore, P.J., Sen Gupta, A., Smale, D.A., and Wernberg, T. (2023). Biological impacts of marine heatwaves. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15: 119–145, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-032122-121437.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Smith, J.G., Malone, D., and Carr, M.H. (2024). Consequences of kelp forest ecosystem shifts and predictors of persistence through multiple stressors. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 291, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2023.2749.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Somero, G.N. (2010). The physiology of climate change: how potentials for acclimatization and genetic adaptation will determine ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. J. Exp. Biol. 213: 912–920, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.037473.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Sorte, C.J. and Hofmann, G.E. (2004). Changes in latitudes, changes in aptitudes: Nucella canaliculata (Mollusca: Gastropoda) is more stressed at its range edge. Mar. Ecol.: Prog. Ser. 274: 263–268, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps274263.Search in Google Scholar

Springer, Y., Hays, C., Carr, M., Mackey, M., and Bloeser, J. (2007). Ecology and management of the bull kelp, Nereocystis luetkeana: a synthesis with recommendations for future research. Lenfest Ocean Program.Search in Google Scholar

Starko, S., Epstein, G., Chalifour, L., Bruce, K., Buzzoni, D., Csordas, M., Dimoff, S., Hansen, R., Maucieri, D., McHenry, J., et al.. (2025). Ecological responses to extreme climatic events: a systematic review of the 2014–2016 Northeast Pacific marine heatwave. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 63, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003589600-2.Search in Google Scholar

Supratya, V.P. and Martone, P.T. (2024). Kelps on demand: closed-system protocols for culturing large bull kelp sporophytes for research and restoration. J. Phycol. 60: 73–82, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.13413.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supratya, V.P., Coleman, L.J., and Martone, P.T. (2020). Elevated temperature affects phenotypic plasticity in the bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana, Phaeophyceae). J. Phycol. 56: 1534–1541, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.13049.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Tomanek, L. (2010). Variation in the heat shock response and its implication for predicting the effect of global climate change on species’ biogeographical distribution ranges and metabolic costs. J. Exp. Biol. 213: 971–979, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.038034.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Tomanek, L. and Somero, G.N. (1999). Evolutionary and acclimation-induced variation in the heat-shock responses of congeneric marine snails (genus Tegula) from different thermal habitats: implications for limits of thermotolerance and biogeography. J. Exp. Biol. 202: 2925–2936, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.202.21.2925.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Tomanek, L. and Somero, G.N. (2002). Interspecific-and acclimation-induced variation in levels of heat-shock proteins 70 (hsp70) and 90 (hsp90) and heat-shock transcription factor-1 (HSF1) in congeneric marine snails (genus Tegula): implications for regulation of hsp gene expression. J. Exp. Biol. 205: 677–685, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.205.5.677.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Vadillo Gonzalez, S., Hurd, C.L., Britton, D., Bennett, E., Steinberg, P.D., and Marzinelli, E.M. (2024). Effects of temperature and microbial disruption on juvenile kelp Ecklonia radiata and its associated bacterial community. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1332501.Search in Google Scholar

Vayda, M.E. and Yuan, M.L. (1994). The heat shock response of an Antarctic alga is evident at 5 C. Plant Mol. Biol. 24: 229–233, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00040590.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Veenhof, R.J., Mcgrath, A.H., Champion, C., Dworjanyn, S.A., Marzinelli, E.M., and Coleman, M.A. (2025). The role of microbiota in kelp gametophyte development and resilience to thermal stress. J. Phycol. 61: 633–649, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.70018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Verghese, J., Abrams, J., Wang, Y., and Morano, K.A. (2012). Biology of the heat shock response and protein chaperones: budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) as a model system. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76: 115–158, https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.05018-11.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Vierling, E. (1991). The roles of heat shock proteins in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 42: 579–620, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.42.1.579.Search in Google Scholar

Wheeler, W.N., Smith, R.G., and Srivastava, L.M. (1984). Seasonal photosynthetic performance of Nereocystis luetkeana. Can. J. Bot. 62: 664–670, https://doi.org/10.1139/b84-099.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, H., Li, W., Li, J., Fu, W., Yao, J., and Duan, D. (2012). Characterization and expression analysis of hsp70 gene from Ulva prolifera J. Agardh (Chlorophycophyta, Chlorophyceae). Mar. Genomics 5: 53–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margen.2011.10.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Physiology and Ecology

- Labelling kelps with 13C and 15N for isotope tracing or enrichment experiments

- Effects of thermal history on the heat shock response of bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana)

- Naturally occurring protoplasts in two Ulva spp. reveal a previously underestimated proliferation process

- Taxonomy/Phylogeny and Biogeography

- Unveiling Cladophora (Cladophorales, Chlorophyta) diversity in Turkey through DNA barcoding

- A new crustose brown alga, Endoplura geojensis sp. nov. (Ralfsiales, Phaeophyceae) from Korea based on molecular and morphological analyses

- Diversity of turf-forming Gelidium species growing on subtidal crustose coralline algae in the East Sea of Korea with a description of G. cristatum sp. nov.

- First record of the diatom pathogen Diatomophthora perforans cf. subsp. pleurosigmae (Oomycota) from the Mediterranean microphytobenthos

- Staminate flowers of the non-native seagrass, Halophila stipulacea, observed for the first time in Biscayne Bay, Florida, USA

- Chemistry and Applications

- Chemical and biological potential of fungi from deep-sea hydrothermal vents and an oxygen minimum zone

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Physiology and Ecology

- Labelling kelps with 13C and 15N for isotope tracing or enrichment experiments

- Effects of thermal history on the heat shock response of bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana)

- Naturally occurring protoplasts in two Ulva spp. reveal a previously underestimated proliferation process

- Taxonomy/Phylogeny and Biogeography

- Unveiling Cladophora (Cladophorales, Chlorophyta) diversity in Turkey through DNA barcoding

- A new crustose brown alga, Endoplura geojensis sp. nov. (Ralfsiales, Phaeophyceae) from Korea based on molecular and morphological analyses

- Diversity of turf-forming Gelidium species growing on subtidal crustose coralline algae in the East Sea of Korea with a description of G. cristatum sp. nov.

- First record of the diatom pathogen Diatomophthora perforans cf. subsp. pleurosigmae (Oomycota) from the Mediterranean microphytobenthos

- Staminate flowers of the non-native seagrass, Halophila stipulacea, observed for the first time in Biscayne Bay, Florida, USA

- Chemistry and Applications

- Chemical and biological potential of fungi from deep-sea hydrothermal vents and an oxygen minimum zone