Abstract

Interest in Ulva cultivation grows worldwide, but associated bottlenecks exist, including ineffective seeding methods, spontaneous reproduction or biomass loss, and high cultivation costs. Spontaneous biomass degradation causes significant losses, and the underlying biological process is still poorly understood. During a spontaneous degradation event in Ulva lacinulata and a reproduction event in Ulva compressa, production of natural protoplasts was observed. U. lacinulata produced high protoplast yields and parts of the original biomass regenerated. In U. compressa, protoplasts were found in fertile thalli, but the original biomass was lost. Protoplast germination rates were low (2.01 ± 0.48 % in U. lacinulata, 4.14 ± 3.31 % in U. compressa), and resulted in three morphologies: unattached germlings, unattached discs, and cell masses. Discs and cell masses became fertile early and released gametes. Our results provide the first evidence of natural production of protoplasts in Ulva spp. We estimate that higher seeding yields can potentially be obtained by natural protoplast production (5.95 ± 4.50 × 1010 individuals g−1) than by gametogenesis (2.03 ± 1.15 × 109 individuals g−1), thus closing an important knowledge gap in the life cycle of Ulva species. These results provide important insights into the reproductive cycle of Ulva spp. relevant for large-scale cultivation.

1 Introduction

Interest in valorising Ulva biomass in industries such as medicine, agriculture, aquaculture, food, and others (Ganesan et al. 2018; Kaeffer et al. 1999; Li et al. 2018; Olasehinde et al. 2019) has existed for many decades due to its interesting bioactive profile (e.g. ulvan; Amin 2020; Gomaa et al. 2022), potentially high protein content (Juul et al. 2021; Rasyid 2017; Shuuluka et al. 2013; Stedt et al. 2022), and bioremediation properties (Bews et al. 2021; Nielsen et al. 2012). More recently, this genus of green macroalgae has been investigated as a candidate for packaging production (Bosse and Hofmann 2020; ERANOVA n.d.; Kajla et al. 2024; Minicante et al. 2022; Nesic et al. 2024), either for biodegradable plastics (ERANOVA n.d.) or food packaging (Bosse and Hofmann 2020). Cultivation of Ulva can provide high-quality biomass with optimized functionality or traits (e.g. high protein, improved antioxidant activity; Lüning and Pang 2003; Ridler et al. 2007; Titlyanov and Titlyanova 2010; Steinhagen et al. 2022a, 2024). Nevertheless, cultivation methods still face many challenges, including effective seeding methods, controlling the reproductive cycle, avoiding the spontaneous loss of biomass, and reducing the costs of production (Bolton et al. 2008; Carl et al. 2014; Gao 2016; Hiraoka and Oka 2008; Huguenin 1976; Steinhagen et al. 2022a).

Vegetative propagation of Ulva is a relatively simple technique for producing Ulva biomass with a low investment as it does not require direct control of the reproduction and life cycle (Ghaderiardakani 2019; Gupta et al. 2018). It depends on the use of vegetative fragments as clonal material, which, in theory, guarantees the constant production of biomass (if kept vegetative; Gupta et al. 2018; Obolski et al. 2022). However, finding the carrying capacity and optimal stocking density for each system is essential (Zertuche-González et al. 2021), as one-fourth of the entire biomass produced is required to stay in the system as the initial input material for the next production period (Radulovich et al. 2015). Additionally, clonal material tends to lose quality over time, requiring the occasional inoculation with new biomass (Hurtado et al. 2013). Moreover, entire biomass loss can occur during a disease outbreak or be caused by abrupt changes in the cultivation conditions (Gachon et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010).

On the other hand, seeding tanks or ropes with spores or gametes requires extensive knowledge and control of the reproduction of Ulva (Bolton et al. 2008; Carl et al. 2014; Hiraoka and Oka 2008; Steinhagen et al. 2022b). Controlling reproduction can be challenging, as molecules that regulate Ulva’s life cycle and reproduction are clade-specific (Alsufyani et al. 2014), and the triggers (environmental and chemical) to induce or inhibit reproduction can vary between species and strains (Balar and Mantri 2020; Brawley and Johnson 1992; Lüning et al. 2008). This can be a limiting factor for cultivation, because, during reproduction, the reproductive part of the Ulva thalli does not grow and loses biomass as the reproductive thalli disintegrate (Bolton et al. 2008; Ryther et al. 1984). Nevertheless, nursery/hatchery systems can be used to guarantee the spore and gamete formation and development before being placed in the main cultivation system or the field (ALGAplus 2023; Carl et al. 2014; Gupta et al. 2018; Praeger et al. 2019). When working with quadriflagellated spores or mated gametes, this method allows for more genetic variability and provides seeding material on demand, in controlled concentrations, therefore guaranteeing high quality and yields (Boderskov et al. 2023; Gupta et al. 2018; Praeger et al. 2019; Rößner et al. 2014). However, it increases the cost of the overall production and requires the use of a sporulating species (i.e., species that can become fertile through gametogenesis or sporogenesis) and a reliable method for inducing reproduction (e.g., variations in salinity, dehydration, segmentation, temperature shock, light colour, and intensity, or utilizing sporulation inhibitors; Nilsen and Nordby 1975; Carl et al. 2014; Gao et al. 2017b; Schwoerbel 2019; Mantri et al. 2011). It also requires several steps to scale the cultivation from nursery to large scale, representing the use of space and manpower. After each harvest, the tank would need to be inoculated with new Ulva (Radulovich et al. 2015) from the nursery, which requires carefully timing the induction of sporulation and the scaling-up process.

An alternative method proposed for the cultivation of Ulva spp., which avoids the bottlenecks of vegetative propagation and control over the life cycle, is the isolation of protoplasts. Our work understands a protoplast as a live plant (or macroalgal) cell that does not possess a cell wall but can regenerate it and regrow into an adult individual (Xing and Tian 2018). In other words, these are spherical plasmolized cells with their contents enclosed only by their cell membrane (Maheshwari et al. 1986). The method of protoplast isolation has been commonly applied to higher plants (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana; Dovzhenko et al. 2003; Davey et al. 2005; Sangra et al. 2019), but also to seaweeds, including Ulva spp. (Avila-Peltroche et al. 2022; Fujita and Saito 1990; Gupta et al. 2018; Reddy and Seth 2018). In theory, this method allows for each cell in a small piece of the thalli to regenerate as a new individual. This technique requires little initial biomass compared to the vegetative cultivation method (Gupta et al. 2018) and does not require a profound understanding of the life cycle. However, this technique is considered expensive for large-scale purposes, since it requires the use of costly laboratory equipment, facilities, and enzyme solutions (e.g., Onozuka R-10 and Macerozyme R-10; Gupta et al. 2018; Reddy and Seth 2018; Avila-Peltroche 2021).

Regardless of the cultivation method used (vegetative, seeding with gametes or spores, or protoplast isolation), spontaneous loss of biomass due to reproductive or degradation events is a common challenge for large-scale production (Bolton et al. 2008; Obolski et al. 2022; Ryther et al. 1984). While the loss of biomass after the release of gametes or spores during a reproductive event in Ulva spp. is a commonly observed and well-understood occurrence (Bolton et al. 2008; Bruhn et al. 2011; Gao et al. 2017c; Steinhagen et al. 2022a), the process of biomass degradation in the absence of reproduction or disease is poorly understood. Such degradation events are often not reported in the literature but are well-known among specialists in Ulva cultivation (Cardoso, personal observations) with some reporting degradation of their Ulva cultures, where in half of the cases the entire cultivation was lost despite controlled growing conditions (Cardoso 2024). To this day, and the best of our knowledge, the terms “degradation”, “disintegration”, “fragmentation” and “loss of biomass” during cultivation have been used in the literature only in the context of a reproduction event (i.e. the release of spores or gametes; Ryther et al. 1984; Bolton et al. 2008). Poor culture conditions and the age of the material have also been reported as causes of degradation and loss of biomass (Carl et al. 2014; Obolski et al. 2022), but most likely because they can both be triggers for sporulation, thereby causing the associated loss of biomass.

To date, only one dispersal method has been reported in Ulva, which is associated with the senescence of Ulva thalli and the appearance of germlings without release of gametes or spores. This observation was described only twice, by Provasoli (1958) and Bonneau (1978) when working with Ulva lactuca. Provasoli (1958) reported that bleached pieces of Ulva thalli would present “green islands” of cells and that those cells “can produce directly new germlings and are far more resistant to unfavourable conditions than the other cells of the thallus which can originate zoospores or gametes”. Bonneau (1978), based on the work from Provasoli (1958), reported the occurrence of similar “green islands” in pieces of bleached thalli and followed the development of these cells after being isolated. Furthermore, Bonneau (1978) concluded that “green island” cells achieved a “complete resumption of totipotency”. Both agreed that this observation was a new mode of asexual reproduction and is a dispersal method, at least, as effective as flagellated cells.

While most Ulva thalli eventually become fertile, some strains have been observed to grow exclusively through vegetative means, without any signs of reproduction (e.g., gametogenesis or sporogenesis). Examples include Ulva spp. cultivated in South African abalone farms (Bachoo et al. 2023; Bolton et al. 2008) and Portuguese Ulva lacinulata (Hofmann et al. 2024), both grown in land-based IMTA systems, where high concentrations of sporulation inhibitors (Obolski et al. 2022) may explain the absence of reproduction. However, other cases lacking a clear explanation have also been reported (Cardoso 2024; Cardoso et al. 2023; Ryther 1982; Ryther et al. 1984). Over two years of controlled and optimised cultivation (Cardoso et al. 2023, 2024b), we consistently observed semi-cyclical blade degradation, occurring at least twice annually, without any evidence of reproductive activity, despite multiple induction attempts. Nevertheless, new germlings regularly appeared in the cultures. Based on these observations and existing literature, we use the term ‘non-sporulating’ to describe Ulva strains that do not go through gametogenesis or sporogenesis but are instead capable of long-term vegetative growth (e.g., over a year), particularly those for which no successful reproduction induction method has been identified. We hypothesized that degradation of biomass, without maturation of thalli, may result in the production of germlings and new biomass, as suggested by Provasoli (1958) and Bonneau (1978). Thus, leading to a further hypothesis that we were dealing with a previously underestimated proliferation process (Bonneau 1978; Provasoli 1958).

Previous observations of protoplast-like cells in our U. lacinulata cultures (August and October 2022) led us to hypothesize that degradation events in this apparently non-sporulating species were associated with protoplast production. In addition, based on previous observations of a local Ulva compressa, we hypothesized that the production of protoplasts during degradation events was not unique to laboratory-grown cultures, but may also be observed in fertile and wild material.

Taking into account the processes that influence the loss of biomass and the degradation of Ulva, we designed an experiment to closely observe and describe thalli degradation in U. lacinulata (non-sporulating and laboratory-grown) and U. compressa (sporulating and collected from the wild) and detail the events that follow including thallus regeneration, natural protoplast formation and its regeneration capacity.

Our findings close an important knowledge gap in the understanding of the life cycle of non-sporulating U. lacinulata, their implications for overcoming some of the currently existing bottlenecks in large-scale production of Ulva species, and their ecological implications.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Biomass collection

Adult Ulva lacinulata (Kützing) Wittrock from the NE-Atlantic was collected in January 2021, in Lagoa de Óbidos, Portugal (39°23′41.5″N 9°12′48.9″W). Adult Ulva compressa Linnaeus from the North Sea was collected in June 2023 in Dorum (Wurster North Sea coast, Lower Saxony), Germany (53°44′30.8″N 8°30′52.4″E). The environmental conditions in which each species was growing in the wild are reported in Cardoso (2024). The temperature in Lagoa de Óbidos ranges between 6 and 24 °C and salinity ranges between 25 and 35 (Cavaco et al. 2016; Mendes et al. 2021). In Dorum temperature ranges from 5 to 18 °C and salinity from 29 to 34 (Scheurle et al. 2005; Sea Temperature n.d.; Weatherspark 2024). Both species were cleaned by rinsing the seaweed with running natural seawater several times to eliminate epiphytes and small organisms on the surface of the blades.

2.2 Molecular analysis

Due to the considerable phenotypic variability observed in various species of the genus Ulva, accurate identification of the utilized biomass often requires the application of molecular identification methods, such as DNA barcoding. The molecular identification of the applied strains followed the description in Steinhagen et al. (2023).

Ulva lacinulata had been previously identified (GenBank accession number: OP778143) by using the plastic-encoded marker tufa (Cardoso et al. 2023). Following the same method, U. compressa was identified for this work (GenBank accession number: PQ274678). Additionally, molecular identification was performed on the F1 generation of individuals developed from U. lacinulata protoplasts obtained at the end of the regeneration experiment described in this work, confirming its origin and molecular similarity with the parental generation.

2.3 Pre-cultivation

The strain of U. lacinulata used in this work was cultivated under similar laboratory conditions since 2021. It was grown for 25 months over many subsequent generations (without ever showing signs of fertility) before the start of the experiment. The cultivation of U. lacinulata took place in one 5-L bottle, in pasteurized artificial seawater (ASW; Seequasal-Salz, Seequasal Salz Production and Trade GmbH, Germany), at a salinity of 30 ± 2 (Refractometer, Atago, Japan), following Cardoso et al. (2023, 2024b ). U. compressa was collected a month before the start of the experiment and grown in one 5-L glass bottle filled with pasteurized natural seawater (NSW) at a salinity of 30 ± 2 (Refractometer, Atago, Japan). Both species were cultivated under the same conditions (15 °C, 70 μmol photons m−2 s−1 white light (Lamps: Aquarius 90 LED, Aqua Medic, Germany; Lamps regulated by Spot Control, Aqua Medic, Germany), 16:8 h light:dark daylength, half-strength Provasoli enriched seawater, PES; Provasoli 1968) as reported in Cardoso (2024), except for the water source (i.e., natural or artificial seawater). The medium in each bottle was changed weekly and all bottles were aerated with compressed air. In both cases, each 5-L bottle contained a mixture of several Ulva individuals. Because the experiments reported in this work started once degradation/reproduction was observed, and because Ulva blades break easily when handled or in tumble conditions, each replicate used in the experiments was treated as a heterogeneous mix of genetic material from different Ulva individuals.

2.4 Characterisation of degradation (Experiment 1)

Definition of a ‘degradation event’ (Figure 1A and B): For the purpose of this work, we defined a degradation event as the period in which Ulva thalli became fragile, changed colour (from green to white), and broke into fragments. The small fragments, tumbling in the water column, created turbidity and accumulated in a foamy layer at the rim of the glass bottle. The end of a degradation event was defined as the moment when the water became clear again and regrowth became visible. For a qualitative observation of the initial stage of the degradation process, pieces of intact and green (i.e., non-bleaching) U. lacinulata and later the bleaching material were photographed (Olympus CKX41, Olympus, Japan) to document the different degradation stages. Classification of Ulva thalli, its cells, and their cell structure and organisation followed Maggs (2007).

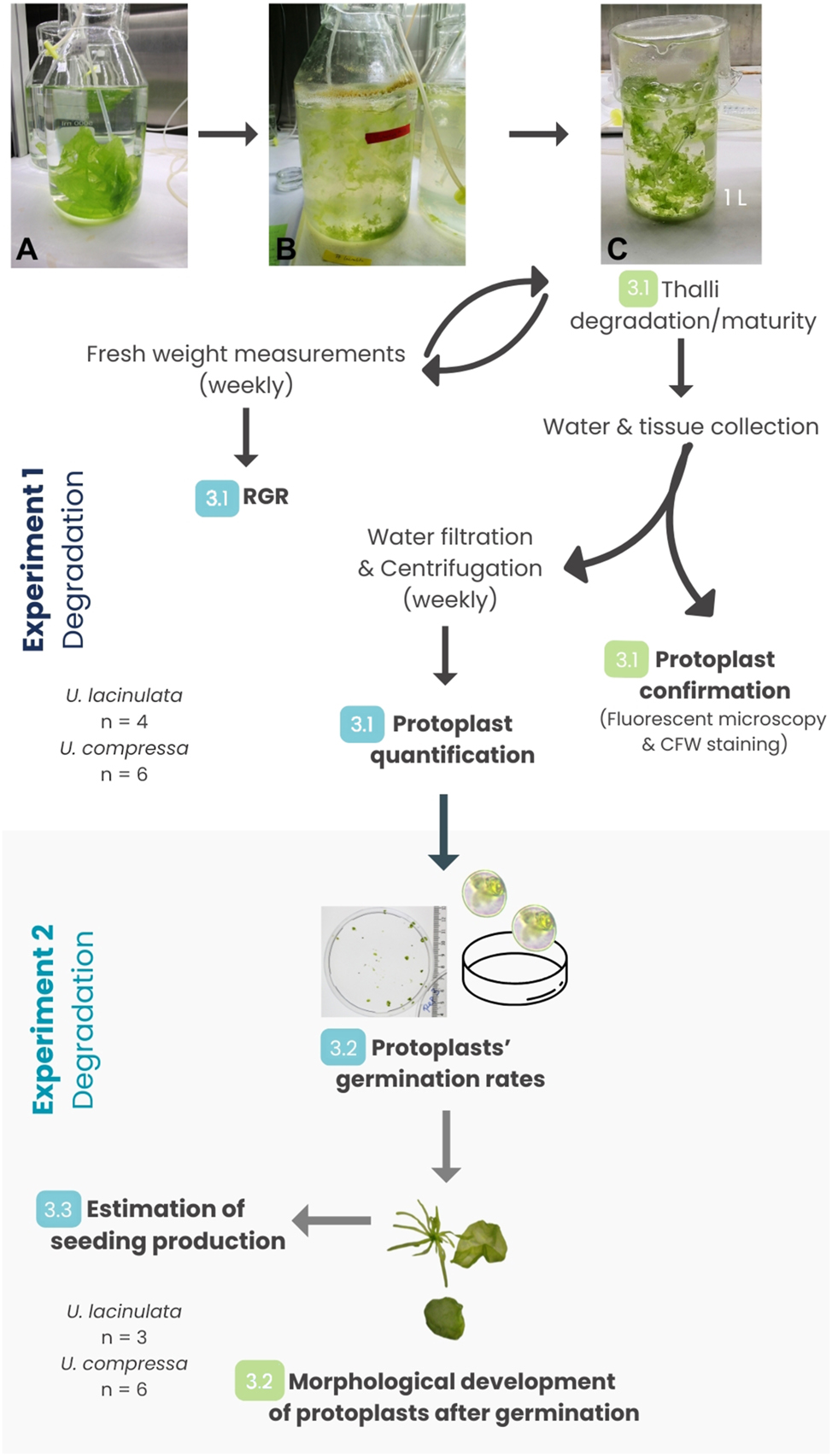

Workflow of Experiments 1 (degradation of thalli) and 2 (germination of protoplasts) and associated measurements (numbers 3.2–3.5 refer to sections in Results). Degradation experiments with Ulva lacinulata (4 weeks) and Ulva compressa (3 weeks) and subsequent germination experiments with both species over 4 and 3 weeks, respectively. (A) Healthy material before the onset of degradation (U. lacinulata); (B) degradation process (same strain). Pale and green fragments of Ulva are visible floating together in the turbid water along with debris and foam accumulated at the rim of the cultivation vessel; (C) start of Experiment 1: Ulva pieces still intact and green (from condition B) were separated into replicate beakers at the beginning of the degradation experiment. The type of data collected from each experiment is highlighted in bold. In Experiment 1, each week, the entire biomass was placed back into the same beaker after being weighed. In Experiment 2, the germination rates were evaluated at the end of the experiment, but the morphological development was followed weekly (3.4). Estimation of seeding production (3.5) was calculated after the end of Experiment 2. Numbers in green represent the steps in which qualitative data were collected. Numbers in blue represent the steps in which quantitative data were collected. *n = 4 (U. lacinulata), n = 6 (U. compressa).

2.4.1 Relative growth rate in a degradation and a reproduction event

Experiment 1a, U. lacinulata: The onset of degradation was not controllable. Thus, Experiment 1 started when a degradation event was visible (T0) and lasted 4 weeks. At T0, 0.18 ± 0.01 g of fresh weight (FW) biomass of healthy green Ulva pieces were inoculated into each of four 1-L beakers (n = 4). These pieces of thalli will be referred to throughout this work as “inoculated biomass”. Before weighing, the excess water was removed by absorbent paper and gently squeezed three times. Each beaker was filled with pasteurized artificial seawater enriched with ½ PES (Provasoli 1968), as described during the pre-cultivation period. All the remaining cultivation conditions were kept as described during pre-cultivation. The relative growth rate (RGR) of the Ulva pieces placed in each beaker was calculated based on the total fresh weight (FW) in each beaker on days 9, 16, 23, and 30 (n = 4). We calculated the relative growth rate (RGR) via Equation (1):

where W f is the fresh weight at the end of the experiment, W0 is the fresh weight at the beginning of the experiment, and t f and t0 are the time, in days (Cardoso et al. 2023).

Experiment 1b, U. compressa: A similar experiment was designed for non-degrading U. compressa. We distributed 0.18 ± 0.01 g FW of healthy and non-fertile thalli to six separate 1-L beakers (n = 6) without cutting the material to avoid inducing fertility (Stratmann et al. 1996; Vesty et al. 2015; Balar and Mantri 2020). Pasteurized natural seawater was used instead of artificial seawater. The experiment was conducted for three weeks, and the FW measurements and water samples were taken on days 0, 5, 12, and 19. Between days 0 and 5 the inoculated pieces of U. compressa placed in the beakers became fertile (phototaxis analysis showed the presence of a mixed culture of sporophyte and gametophyte individuals). In the beakers, an abundance of germlings was visible within two weeks. The fragments of the inoculated blades were separated from the new germlings before weighing to guarantee the correct weighing of the inoculated biomass each week. At the end of the experiment, RGRs were calculated based on the weekly FW measurements.

In both experiments, during the weekly FW measurements, random water and thalli samples were collected for the qualitative observation of protoplasts, and the entire volume of seawater (1 L) in each beaker was collected from each replicate for the collection and future quantification of protoplasts. Weekly, each beaker was filled with new medium, and all thallus pieces (>30 µm) were placed back into the beakers.

2.4.2 Protoplast confirmation and yield quantification

Qualitative observation of protoplasts: Water and pieces of the degraded thalli were collected from the beakers (Experiment 1a, b) to qualitatively confirm the occurrence of protoplasts and observe the degradation process of the thalli. The water samples and degraded thalli were stained with 0.01 % calcofluor white (single, absorbance peak = 347 nm), following Reddy and Seth (2018) The stock solution of calcofluor white (CFW) was prepared by sequentially diluting 1 ml of 100 % CFW into two consecutive batches of 9 ml of ASW, resulting in a 1 % CFW solution. For staining, 55.6 µl of this stock solution was diluted into 0.5 ml of ASW, and 55.6 µl of the resulting solution was then added to 0.5 ml of each sample of water and degraded thalli, yielding a final concentration of 0.01 % CFW. The presence or absence of a cell wall was confirmed under a fluorescent microscope (Filter set 02, Axioplan 2 imaging, Zeiss, Germany).

Quantification of protoplasts: For the quantification of protoplasts (experiment 1a, b), the water from each replicate beaker (1 L) was collected and filtered weekly into approx. twenty 50-ml Falcon tubes. The water was stirred before filtration to guarantee the suspension of protoplasts and was filtered through a 30-µm mesh (30 mm; PluriStrainer®, Pluriselect, Germany), closely following the protocol described for protoplast isolation (Gupta et al. 2018; Reddy and Seth 2018). At the end of filtration, each beaker was rinsed three times with the ASW, also filtered and collected in an additional Falcon tube. Half of the Falcon tubes were centrifuged at 124g for 5 min (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5810-R, Germany), the supernatant was discarded and the content of the remaining uncentrifuged samples was added to the pellets of the centrifuged Falcon tubes. After resuspension, the samples were centrifuged again, and this cycle of centrifugation and resuspension was repeated until all protoplasts from each replicate were concentrated into one single 50-ml Falcon tube. The supernatant was discarded after each step. Finally, the pellets were resuspended in fresh pasteurized ASW enriched with half-strength PES to a final volume of 12.5 ml. 10-µl subsamples of the resuspended pellet from each sample were placed in disposable haemocytometers (Neubauer Improved, C-Chip, NanoEnTek Inc., Korea) to count the number of Ulva protoplast-like cells. For each replicate, the protoplast concentration was calculated as the average of 10 counts (U. lacinulata; n = 4) or 14 counts (U. compressa; n = 6). The 4 larger squares (top right, top left, bottom right, and bottom left) in the haemocytometer were used for cell counting. Protoplast concentration (in cell ml−1) was calculated by the product of the known number of cells counted in the haemocytometer and the multiplication factor (104), divided by the number of squares counted (four squares). Protoplast yields (in cells g−1 of thalli) were calculated in two ways: 1) by dividing the concentration of protoplasts by the FW of the thalli measured the week before; 2) by dividing the concentration of protoplasts by the FW of the thalli measured at the beginning of the experiment (i.e., assuming that the degradation of the inoculated biomass thalli was responsible for all the protoplasts collected).

2.5 Protoplast regeneration and germination (Experiment 2)

Known volumes from the concentrated protoplast solutions obtained per replicate during Experiment 1 (Supplementary Table S1) were resuspended and seeded into Petri dishes with 50 ml (U. lacinulata; n = 4) or 15 ml (U. compressa; n = 6) of pasteurized seawater enriched with ½ strength PES and cultivated under the same conditions as the parental material (15 °C, 70 μmol photons m−2 s−1, 16:8 h LD) but without aeration or a shaker, following Gupta et al. (2018).

Experiment 2a, U. lacinulata: 10 Petri dishes (90 mm diameter) per replicate (n = 4) were filled with 50 ml of pasteurized artificial seawater with inoculated with 1.44 × 103 ± 5.78 protoplasts of U. lacinulata (Supplementary Table S1). Due to contamination observed in one of the four replicates, only three replicates were analysed (n = 3).

Experiment 2b, U. compressa: Because the protoplast yields from U. compressa were lower than in Experiment 2a, an identical volume of protoplast solution was added to each Petri dish instead of inoculating the Petri dishes with the same protoplast density (as in the experiment with U. lacinulata). Per replicate (n = 6), 10 smaller Petri dishes (60 mm diameter) were filled with 15 ml of pasteurized natural seawater enriched with ½ strength PES and inoculated with 300 µl of protoplast solution. The number of protoplasts in each replicate Petri dish was calculated based on the protoplast density, the volume of protoplast solution added and the volume of water in each Petri dish (Supplementary Table S1).

For Experiments 2a and 2b, the regeneration of the protoplasts and further germination were followed weekly in all replicates by repeated microscope and binocular (Olympus CKX41 and Olympus SZX10, Olympus, Japan, respectively) observations over five (U. lacinulata) and four (U. compressa) weeks. At the end of the experiments, visible germinated Ulva individuals were counted under the binocular and germination rate was calculated from the initial inoculation density. The different morphologies resulting from protoplast germination were categorized as: unattached discs (UD), unattached germlings (UG), or attached germlings (AG), based on their morphology and the presence or absence of rhizoids. UDs were further classified based on their colours at the end of the experiment (green, olive-green or white). Olive-green and white UDs were observed under the microscope to confirm their maturity (olive-green UDs) or occurrence of empty cells due to the release of swarmers (white UDs). Swarmers were collected into Pasteur pipettes half-covered with aluminium foil to evaluate their phototactic response to light (Kuwano et al. 2012; Mantri et al. 2011). Figure 1 shows the connections between Experiments 1 and 2 and summarizes the data collected in the process.

2.6 Estimating the reproductive efficiency of gametogenesis versus protoplast production

Using the data collected during Experiments 1 and 2, the reproductive success during degradation (as an asexual strategy) was evaluated by estimating the expected number of U. lacinulata plantlets produced via this process (Supplementary Equations S2–S7). These estimations were later compared to the estimated number of plantlets produced during gametogenesis. Due to a lack of data in the literature specific for U. lacinulata or other distromatic Ulva species, our calculations are based on gamete production data from Ulva prolifera O.F.Müller (gametes produced per cm2 and per g of U. prolifera) reported by Zhang et al. (2013) and the data collected during Experiments 1a and 2a.

The number of gametes produced per g of U. prolifera (2.03 ± 1.15 × 109 cells g−1) indicated by Zhang et al. (2013) was assumed to be the number of gametes possibly produced by U. lacinulata during gametogenesis. The number of gametes produced per cm2 of U. prolifera (1.90 ± 1.07 × 107 cells cm−2) reported by Zhang et al. (2013) was considered in two scenarios used for the estimation of the reproductive output during degradation: (1) One scenario was based solely on the quantitative data from our experiments. This included the protoplast concentration, percentage of protoplast germination, morphology ratios, and percentage of UDs (developed from protoplasts) that became fertile during the experiment (olive-green and white discs). (2) The other scenario was based on the same quantitative data, except for the percentage of UDs that become fertile. In this case, UDs were considered as an intermediate stage which would all become fertile (100 %) and would not develop into adults. This assumption was based on later observations after the end of Experiment 2 (Cardoso 2024). Ultimately, a comparison was made between the plantlets that could potentially be produced via gametogenesis (i.e., if U. lacinulata was a sporulating species) versus the observed degradation involving protoplast formation plus subsequent gametogenesis (i.e., fertile UDs). The estimations of the number of plantlets produced by degradation were calculated by adding the average number of plantlets produced by germinated protoplasts either directly (via unattached germlings and non-fertile unattached discs) or indirectly (via unattached discs that became fertile), based on the protoplast yields and the percent of protoplasts that regenerated into each morphology (Eq. S2–S7).

2.7 Statistical analysis

In each experiment, each replicate was treated as an independent biological replicate. While individual blades could not be tracked due to fragmentation, each replicate contained a randomly assigned, independently prepared biomass sample. All the quantitative data in this work is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), except when stated otherwise.

Repeated measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA) and post-hoc tests were used to analyse the differences in RGRs over time for both Ulva species. Sphericity of the data was analysed and corrected, if necessary, prior to performing the RM-ANOVA test.

As the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were not met, protoplast yields were evaluated with non-parametric Welch’s ANOVAs followed by the Games Howell post-hoc test (with p-value adjusted by the Bonferroni method for multiple testing) to detect significant differences between groups. The results of the post-hoc test are given in Supplementary Table S3. For statistical analysis between two groups (i.e., comparison between protoplast yields from the two Ulva species), the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used. Regression analyses were performed to evaluate the RGR as a function of time (in weeks) for both species, and the variation of protoplast yields from U. lacinulata as a function of time (in weeks). For each regression analysis, different degrees of polynomial equations (second, third, fourth and fifth degree) were tested using the function “lm()” to determine the best fit based on the adjusted R2 and p values. This resulted in the application of two-degree polynomial functions (y = ax2 + bx + c). The statistical data from the regression analysis is summarized in Supplementary Table S2.

All the statistics were performed with the R studio software (R Core Team 2024) with the packages “rstatix”, “RVAideMemoire”, “DescTools”, “car”. All the figures on regression analyses were created by the “geom_smooth” function (package “Ggplot2”) in the R studio software (R Core Team 2024). A column graph was created by R studio software (R Core Team 2024) using the function “geom_col” (package “Ggplot2”).

3 Results

3.1 Characterisation of degradation (Experiment 1)

Ulva lacinulata’s degradation event was characterized based on the RGRs of the degrading inoculated biomass, the microscopic observations of the thalli, and the presence and yields of collected protoplasts (Experiment 1a). These results were compared with those from Experiment 1b, with fertile U. compressa. The RGRs showed a clear difference between the behaviour of degrading biomass versus fertile biomass, while the microscopic observations revealed similarities between the two, with both species producing protoplasts (although, significantly different yields) and showing distinct cellular behaviours within their thalli (i.e., heterogeneity of the thalli).

3.1.1 Relative growth rates of degrading or fertile Ulva thalli

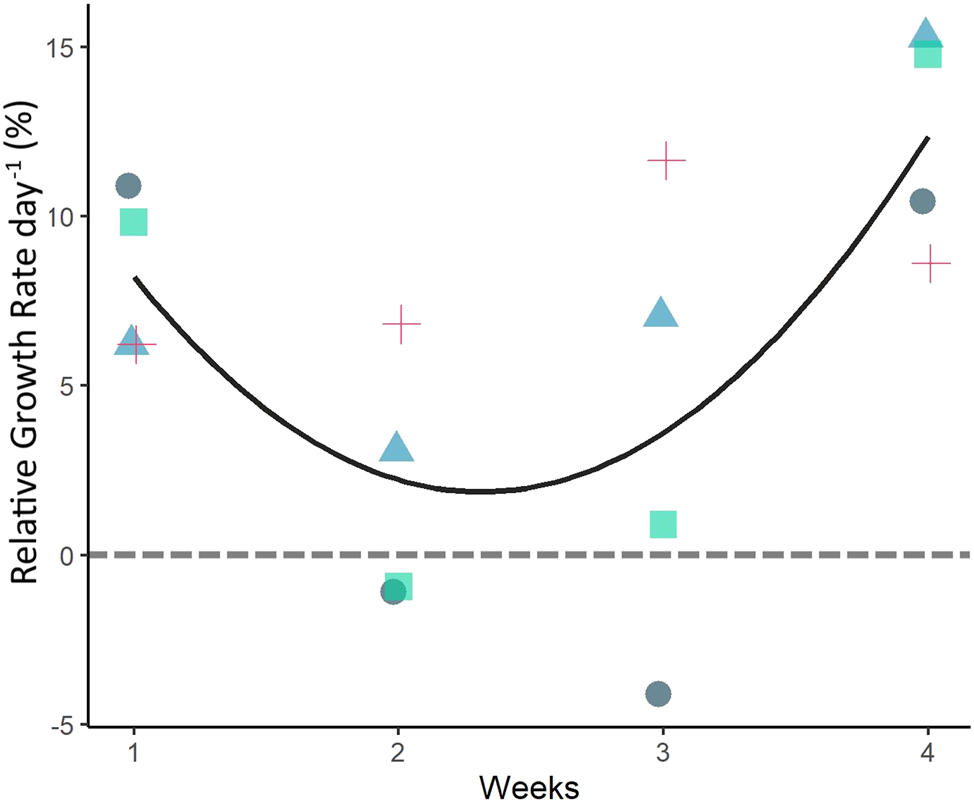

Experiment 1a, U. lacinulata: The relative growth rate of U. lacinulata thalli over time in the degradation experiment is given in Figure 2. Despite degradation, the biomass increased their fresh weight 8-fold during the 4 weeks, from 0.179 ± 0.006 g FW at day 0 to 1.45 ± 0.6 g FW at day 30. The average growth rate was 6.6 ± 4.6 % day−1 calculated over the 4 weeks. Growth rates significantly differed over time (p < 0.05, repeated measures ANOVA), but post-hoc tests did not detect differences between weeks. There was a decrease in RGR between week 1 and 2 (RGR week 1 = 8.29 ± 2.44 % day−1, RGR week 2 = 1.96 ± 3.76 % day−1) and an increase in RGR between week 3 and week 4 (RGR week 3 = 3.87 ± 6.9 % day−1, RGR week 4 = 12.28 ± 3.28 % day−1).

Relative growth rate (RGR) of Ulva lacinulata thalli in Experiment 1a followed over 4 weeks. RGR based on weekly FW. The black line represents the best fit non-linear correlation of growth over time (weeks; adjusted R2 = 0.99, p-value = 0.048). Each replicate is represented by a different colour and symbol to highlight the variations in RGR between replicates. The grey dashed line highlights zero RGR.

Despite the average RGR being positive throughout the weeks, and the increase in RGR observed by the end of the experiment, one replicate had a negative RGR of −4.1 % day−1 between weeks 2 and 3 which amounted to a 25 % biomass loss. Nevertheless, in all replicates, the thalli recovered, and growth resumed (Supplementary Figure S1; Supplementary Table S2).

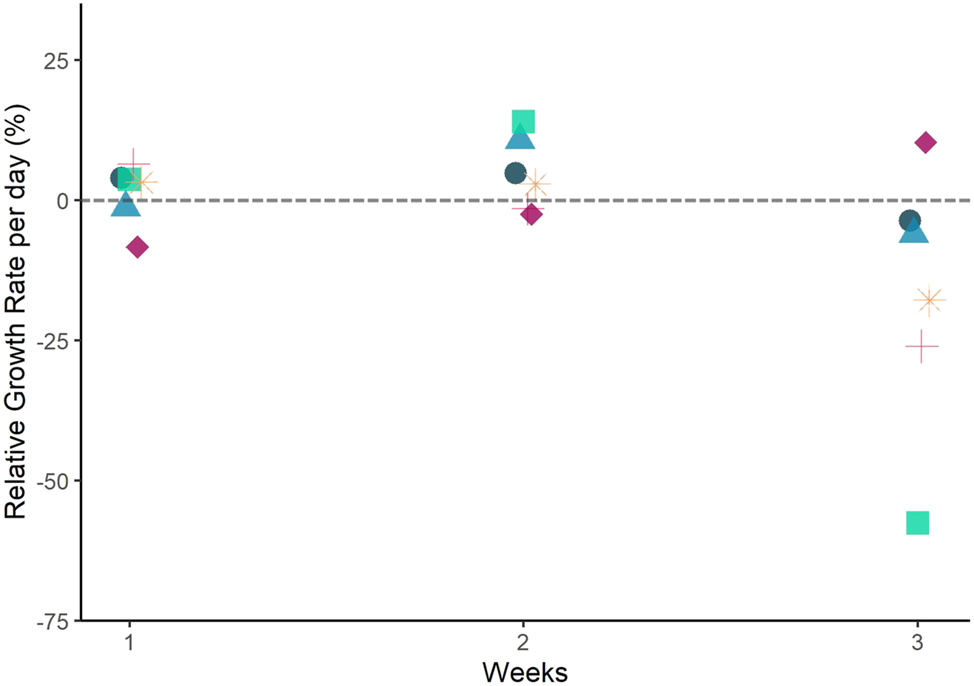

Experiment 1b, U. compressa: This species showed an overall tendency for biomass loss over time, starting with 0.179 ± 0.003 g FW at day 0 and ending the experiment with 0.131 ± 0.1 g FW at day 19. RGRs were close to zero or negative (Figure 3). After three weeks, 34.2 ± 74.32 % of the thalli had been lost. At the end of the experiment, all initial thalli were completely lost. Positive RGRs were observed after week 1 and week 2 (1.2 ± 5.34 and 4.70 ± 6.56 % day−1, respectively; n = 6). In the last week, the average RGR was −16.8 ± 23.54 % day−1 (n = 6; Figure 3). However, during the experiment, one replicate behaved differently and showed a continuous increase in RGR despite showing signs of fertility as the other replicates.

Relative growth rate (RGR) of Ulva compressa thalli over time in Experiment 1b. RGR based on weekly FW. Each replicate is represented by a different colour and symbol to highlight the variations in RGR observed between replicates. The grey dashed line highlights zero RGR. Note: the material was fertile during the whole experiment. There was no correlation between RGR over time (weeks).

3.1.2 Microscopic observations

Experiment 1a, U. lacinulata: During the degradation event in U. lacinulata (Figure 1B), the surface view of the thallus showed heterogenous cell organization that differed from the typical vegetative cell organization (Figure 4A and B). The thallus was divided into small pale cells and larger green cells (Figure 4B). The small pale cells maintained their polygonal/square shape and were filled with granules, similar to starch granules reported in Ulva ohnoi (Prabhu et al. 2019). In these cells, the lack of green colour hindered the identification of cell structures such as pyrenoids or chloroplasts. The larger green cells were spherical, with a clear parietal plastid in a cup-shape form with a visible bright green chloroplast (Figure 4C). In some cases, pyrenoids were easily observed in these larger, spherical cells, but starch granules were seldomly found. These protoplast-resembling cells, with an average diameter of 40.3 ± 1.92 µm (n = 4) were later detached (Figure 4D and E) and released from the thalli. In the degrading pieces of thalli that produced these cells, no sign of sporogenesis or gametogenesis was ever observed.

![Figure 4:

Microscopic observations of thalli of Ulva lacinulata going through the degradation process [(A and B) show different pieces of Ulva]. (A) Surface view and typical cellular structure of a healthy vegetative NE-Atlantic U. lacinulata thallus. (B) Cell type heterogeneity during degradation (pale cells mixed with green cells). (C) Heterogeneity of cell types within the thalli. Large spherical green cells with one parietal chloroplast and single pyrenoids are visible between much smaller pale green cells containing a dense accumulation of grana. (D) Spherical cell detaching from the thallus (arrow). (E) Protoplast-like cells with parietal chloroplast detaching from the main Ulva thallus.](/document/doi/10.1515/bot-2025-0017/asset/graphic/j_bot-2025-0017_fig_004.jpg)

Microscopic observations of thalli of Ulva lacinulata going through the degradation process [(A and B) show different pieces of Ulva]. (A) Surface view and typical cellular structure of a healthy vegetative NE-Atlantic U. lacinulata thallus. (B) Cell type heterogeneity during degradation (pale cells mixed with green cells). (C) Heterogeneity of cell types within the thalli. Large spherical green cells with one parietal chloroplast and single pyrenoids are visible between much smaller pale green cells containing a dense accumulation of grana. (D) Spherical cell detaching from the thallus (arrow). (E) Protoplast-like cells with parietal chloroplast detaching from the main Ulva thallus.

Experiment 1b, U. compressa: Cell heterogeneity was also observed in pieces of thalli of U. compressa, but during blade maturity and swarmer release (Figure 5B). Enlarged, spherical, bright green cells, similar to those in U. lacinulata (Figure 4E) were also present in U. compressa (Figure 5C and D), with these cells showing no signs of maturity or swarmer formation. These bright green cells, with a parietal chloroplast and a single pyrenoid, had an average diameter of 19.04 ± 1.43 µm (n = 5) and were present at the thallus margin, already detached (Figure 5C and D). At the same time, we also observed Ulva swarmers (with eyespots) in the same thalli swimming inside the cells (Figure 5B) and being released from the thalli. Between fertile cells, bright green spherical cells were found (Figure 5C).

Microscopic observations of Ulva compressa simultaneously producing swarmers and protoplasts. (A) Surface view of non-fertile, vegetative part of U. compressa; (B) mature area from the same blade with three types of cells: cells full with swarmers (zoidangia; long arrow), empty cells, and larger rounder cells (protoplasts-like cells; arrow heads); (C) edge of the same blade piece as (B), where cell wall structure is not visible. Protoplast-like cells (arrowheads) mixed with zoidangia (long arrow) released by the same blade; (D) the edge of the same blade with detached round Ulva cells with parietal plastids (protoplast-like cells).

3.1.3 Protoplast confirmation and yields

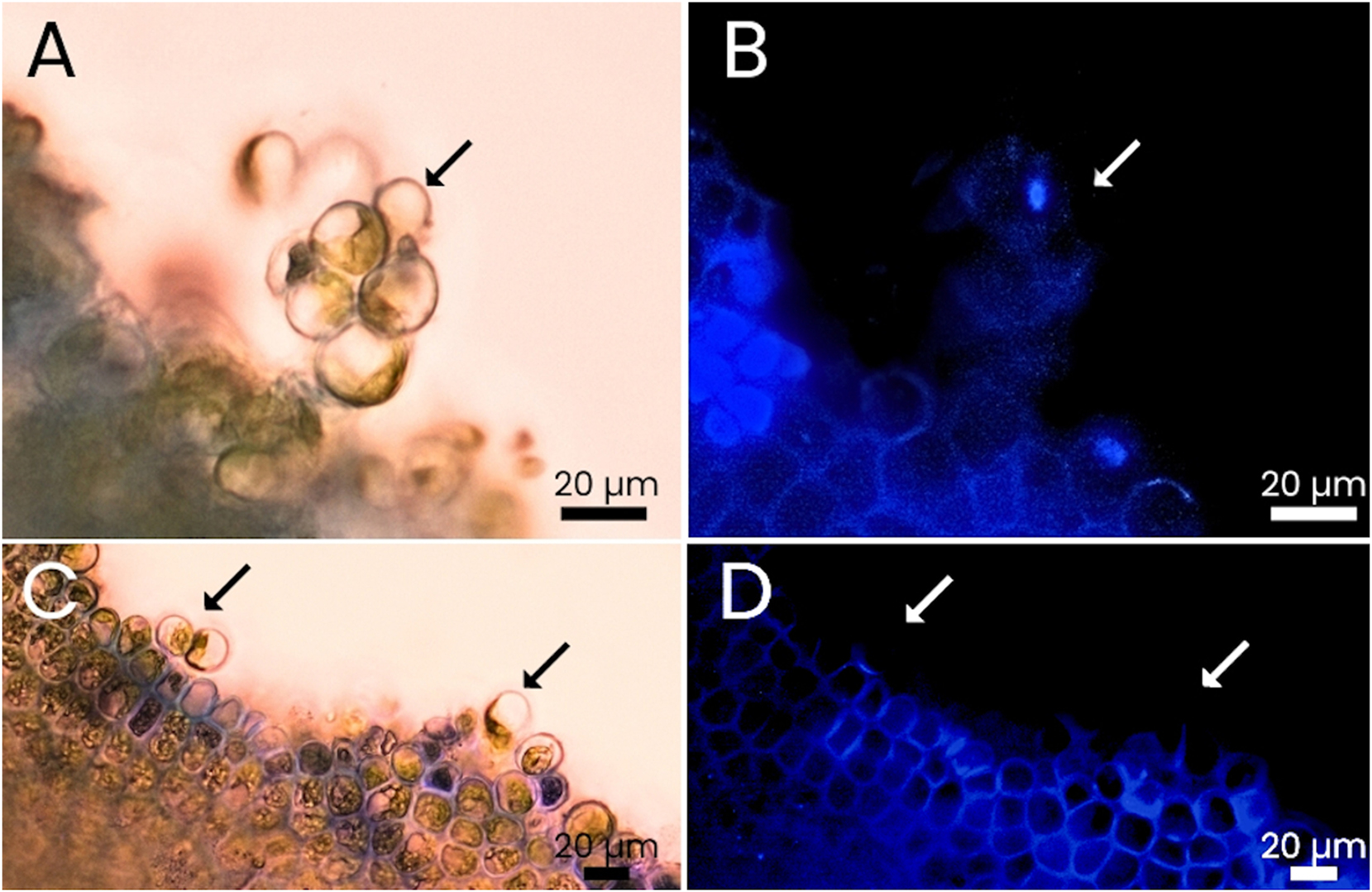

Experiment 1a, U. lacinulata: Microscopic fluorescent analysis with CFW dye showed the total or partial absence of cell walls in individual Ulva cells or degraded thallus pieces of degrading U. lacinulata thalli confirming the degradation of the cell wall and the presence of protoplasts (Figure 6).

![Figure 6:

Fluorescent microscopy of Ulva lacinulata cells dyed with calcofluor white in white light and fluorescent light. Many marginal cells show partial or no fluorescence, indicating the absence of cell walls. (A and B) show the same picture with different fluorescence levels for comparison [(A) has a mixture of white and fluorescent light, (B) was only illuminated with fluorescence light]. Black arrows (in A) and white arrows (in B) point to areas with no fluorescence (i.e. indicating absence of cell wall).](/document/doi/10.1515/bot-2025-0017/asset/graphic/j_bot-2025-0017_fig_006.jpg)

Fluorescent microscopy of Ulva lacinulata cells dyed with calcofluor white in white light and fluorescent light. Many marginal cells show partial or no fluorescence, indicating the absence of cell walls. (A and B) show the same picture with different fluorescence levels for comparison [(A) has a mixture of white and fluorescent light, (B) was only illuminated with fluorescence light]. Black arrows (in A) and white arrows (in B) point to areas with no fluorescence (i.e. indicating absence of cell wall).

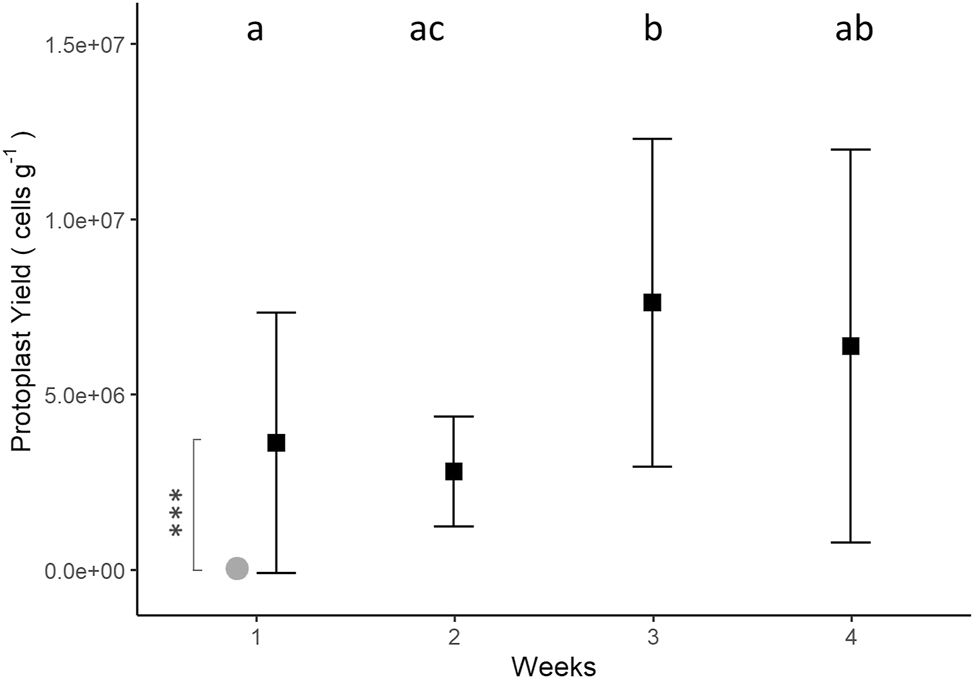

Overall, a total of 3.05 ± 0.04 × 107 protoplasts were collected by the end of the experiment resulting from degradation of 0.179 ± 0.006 g FW of Ulva. Assuming the fresh thalli, weighed the week prior, were responsible for the production of the protoplasts counted in the following week, the average production of protoplasts collected from U. lacinulata after 4 weeks was 5.11 ± 2.26 × 106 cells g−1 (n = 4). The highest protoplast yield observed was during the third week of the experiment with an average of 7.62 ± 4.94 × 106 cells g−1 (n = 4), and the lowest yield was in the second week with an average of 2.81 ± 1.48 × 106 cells g−1 (n = 4). Protoplast yields varied significantly between weeks (p < 0.001). They were higher in week 1 (3.63 ± 3.74 × 106 cells g−1) and week 2 (2.81 ± 1.48 × 106 cells g−1) than in week 3 (7.62 ± 4.94 × 106 cells g−1; wk 1 = wk 2 < wk 3; p < 0.05; Figure 7, Supplementary Table S3). Moreover, an increase in protoplast yield over time was observed in two replicates (Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Table S2). These were the same replicates that lost biomass (no net growth) during the second and third weeks (Supplementary Figure S3; Supplementary Table S2).

Protoplast yield (cells g−1) of Ulva lacinulata over time, based on the FW measured in each replicate beaker the week before protoplast collection (black squares) (mean ± SD; n = 4). Small letters indicate significant differences between weeks (Welch’s ANOVA and Games Howell post-hoc test, with p-value adjusted by the Bonferroni method). ***Indicate the significant difference (p < 0.001) between protoplast yields from U. lacinulata and Ulva compressa (grey circle) in week 1 (Mann-Whitney U test; Protoplast yields, U. compressa: 3.96 ± 3.48 × 104 cell g−1).

There was no correlation between protoplast yield and thalli weight, RGR, or time.

Experiment 1b, U. compressa: Fluorescent microscopic analysis with CFW showed the total or partial absence of cell walls in individual cells and thalli of U. compressa, confirming the degradation of the cell wall and the presence of protoplasts (Figure 8). However, protoplast yields were very low during the experiment with this species. Protoplasts were present over time but the yields registered in weeks 2 and 3 were considered too low to be reliable. The biomass fertility led to the low RGRs reported during those weeks, and the germination of new germlings inside the replicate beakers interfered with accurate FW measurements, necessary for the proper calculation of the protoplast yields per gram of FW. For these reasons, only the protoplast yield from the first week was used to compare between the two species. At the end of the first week, an average of 3.96 ± 3.48 × 104 cells g−1 (n = 6) were produced by 0.18 ± 0.01 g FW, a result significantly lower than the one reported in U. lacinulata (Figure 7).

Comparison of Ulva compressa thalli dyed with calcofluor white under white light and fluorescent light. Cells show no or only little fluorescence as they detach from the thalli. (A and B) Protoplasts detached from a thallus are seemingly attached to each other; same picture with different conjugations of white (A) and fluorescence light (B). (C and D) Protoplasts in the process of detachment from the thallus; same picture with different conjugations of white (C) and fluorescence light (D). Arrows point to areas where fluorescence is missing (i.e. indicating absence of cell wall).

3.2 Protoplast germination, resulting morphologies and consecutive fertility (Experiment 2)

Experiment 2 aimed to evaluate the success of natural protoplast regeneration, germination and growth after being collected during a degradation (U. lacinulata) and a reproduction event (U. compressa). This was done by quantifying the number of new macroscopic individuals that germinated at the end of Experiment 2. This experiment revealed variations in cell division following cell wall regeneration, the co-occurrence of distinct morphologies, and unexpected early-stage fertility in some regenerated forms. For this reason, the complex developmental, morphological and reproductive pattern after protoplast germination is summarized in Figures 9 and 10 for U. lacinulata. We differentiate two major processes: (1) germination of protoplasts with subsequent formation of different thallus morphologies, and (2) fertility of part of these morphologies and the resulting shape of germlings produced from gametes, also in comparison to U. compressa. The results at the end of Experiment 2 were similar between species.

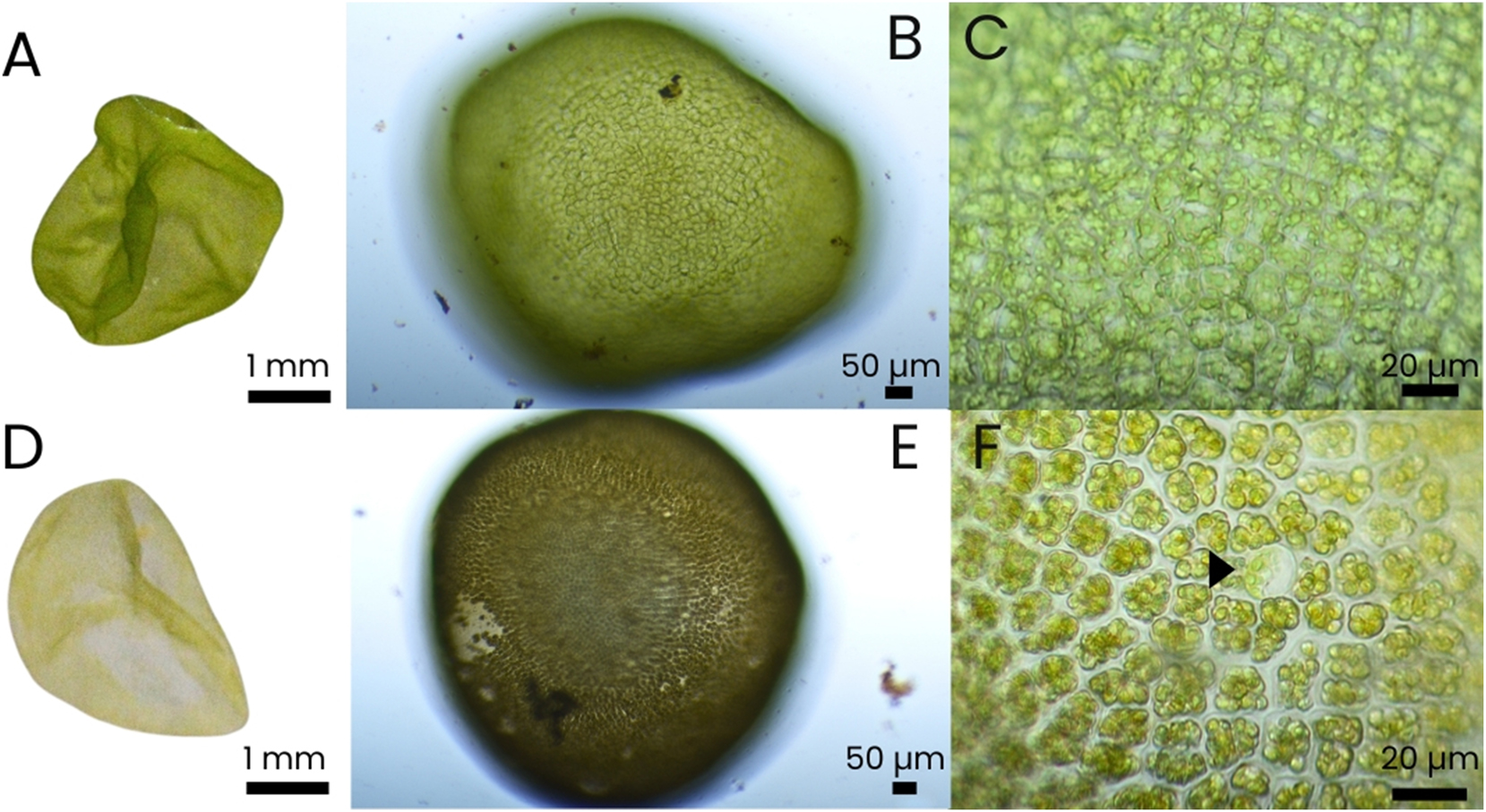

Scheme of protoplast development from Ulva lacinulata (each picture belongs to different individuals). (A) Single protoplast (week 1); (B) protoplast dividing (week 1); (C) germinating protoplasts with regenerated cell walls – the upper cell has divided into two cells (week 1); (D) cell mass after multiple cell divisions (week 1); (E) protoplast development into a cell mass (as in D) with potential to grow into an unattached disc (UD) and as a branched, unattached germling (UG) without a visible rhizoid (week 2); (F) unattached disc (UD) and branched germling without rhizoids (UG) developed from U. lacinulata protoplasts (week 5).

Unattached discs that developed from protoplasts (Boderskov et al. 2023) of Ulva lacinulata and their maturation 5 weeks after protoplast release. (A) Vegetative green unattached disc (UD) developed from protoplast (week 5); (B and C) close-up of the same; (D) UD becoming fertile (week 5 after protoplast release); (E and F) close-up of the same showing olive-green (fertile) UD and gametes inside the cells. In the centre (arrowhead), one single large spherical cell is visible, similar to the protoplasts that were produced by the inoculated biomass.

Germination (Experiments 2a and 2b): Ulva protoplasts from both species regenerated and showed the capacity to germinate into new individuals. In both species, after protoplast release from the inoculated biomass, often aggregated groups of protoplasts became visible in the beakers (during Experiment 1) and the Petri dishes (at the beginning of Experiment 2; Figure 8A and B and Supplementary Figure S4A). However, each protoplast developed independently into a separate individual (Supplementary Figure S4B). The average germination rate of protoplasts from U. lacinulata was 2.01 ± 0.48 % (n = 3). The average germination rate of protoplasts from U. compressa was 4.14 ± 3.31 % (n = 6).

Resulting morphologies (Experiments 2a and 2b): During germination, the protoplasts of the two species developed into three distinct morphologies: (1) microscopic spherical cell masses, (2) unattached discs (UD), and (3) unattached germlings (UG; Figure 9). In U. lacinulata, UD and UG were visible within 2–4 weeks after protoplast release. Both morphologies remained unattached to any substratum (i.e., no visible rhizoid) and UGs developed several branches (Figure 9E and F). In U. compressa, the UD and UG morphologies were observed during the 4th week. Both species developed into UD and UG in a ratio close to 1:1 (Table 1). Cell masses were visible one week after protoplast release but were not considered in the ratio as only macroscopic individuals were counted at the end of the germination experiment.

Average number of germinated protoplasts per replicate, from Ulva lacinulata and Ulva compressa separated by their morphology (mean ± SD), morphotype ratios and colour (indicating fertility).

| Species | UD | UG | Ratio UD:UG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U. lacinulata (n = 3) | 15.3 ± 3.1 | 13.5 ± 3.8 | 1.13:1 | |

| Green | 12.5 ± 3.5 | |||

| Olive-green | 1.6 ± 0.9 | |||

| White | 1.2 ± 0.7 | |||

| U. compressa (n = 6) | 2.3 ± 1.96 | 2.7 ± 4.85 | 0.85:1 | |

| Green | 2.3 ± 1.96 | |||

| Olive-green | NA | |||

| White | NA | |||

-

UD, unattached discs; UG, unattached germlings; NA, not counted; green, non-fertile; olive-green, fertile; white, previously fertile, gametes were released to the medium.

Fertility of regenerated protoplast morphologies (Experiments 2a and 2b): The spherical cell masses (from the 1st week onwards; Supplementary Figure S3) and some of the UDs (18.34 ± 8.05 %; from the 4th week onwards) produced by U. lacinulata became fertile (Figure 10D–F) and did not develop further. Once the swarmers from U. lacinulata were released, positive phototaxis confirmed the presence of gametes. After gamete release, the cells were empty, and the discs and cell masses lost their colour. While all UDs from U. lacinulata became fertile during or shortly after the last week (5th week) of the experiment, the same was not visible in the UDs from U. compressa, in which case the experiment lasted only four weeks due to high germling density in the Petri dishes.

Morphology of germinated swarmers (Experiments 2a and 2b): Both the released gametes from regenerated protoplasts of U. lacinulata, and the swarmers directly produced by the sporulating species, U. compressa, germinated (Experiment 2) and produced attached germlings (AG). AGs were mostly visible in the experiment with U. lacinulata in weeks 4 and 5, while in the experiment with U. compressa the AG morphology was visible after only two weeks. In both cases, the visible high density of AGs exceeded the protoplasts. While the experiment with U. compressa was shorter and phototaxis was not performed in its UDs and cell masses, the same technique was employed after one week once blades showed signs of fertility. However, the test was inconclusive, suggesting the presence of a mixed culture producing both spores and gametes. These spores and gametes were then grown in the Petri dishes together with the products of protoplast germination (i.e., UGs, UDs, cell masses) and their offspring.

Difference between UG and AG morphology per species (Experiments 2a and 2b): Once settled in the Petri dishes, all U. lacinulata gametes released by the UDs and cell masses (formed after protoplast germination; Figure 10 and Supplementary Figure S4) presented a central chloroplast (Supplementary Figure S6A; instead of the parietal chloroplast in the protoplasts) and developed into single-branched germlings attached to the Petri dish with a rhizoid, denominated AG (Supplementary Figure S6C-D) or as a germling cluster (Supplementary Figure S6E). The main differences between the AG and UG morphologies in U. lacinulata are threefold: 1) origin (i.e., originated by gametes or protoplasts); 2) presence of a rhizoid, thus being attached (AG) or unattached (UG) to the Petri dishes; 3) number of branches (i.e., single-branched or multi-branched). However, this distinction was only possible between AGs and UGs from U. lacinulata. In the experiment with U. compressa attached and unattached germlings were also present, but the origin of the different morphologies and the number of branches between germling morphologies was unclear. Contrary to what was observed in U. lacinulata, some attached germlings presented several branches.

3.3 The reproductive efficiency of gametogenesis versus protoplast production in Ulva lacinulata (Experiments 1a and 2a)

To evaluate whether natural protoplast production during degradation represents an overlooked and effective mode of asexual reproduction, or a viable, low-cost method for protoplast isolation, we compared our experimental results with estimations based on relevant literature. Specifically, we estimated potential seedling (gamete) yields from gametogenesis (assuming U. lacinulata could be induced to reproduce) and compared them with the number of new Ulva individuals potentially produced through degradation, as observed at the end of Experiment 2. This latter estimation was based on measured protoplast yields, observed regeneration rates, and the diversity of morphologies, including instances of early-stage reproduction. The comparison suggests that degradation-induced protoplast formation may exceed gametogenesis in its capacity to generate new Ulva individuals.

Based on the work by Zhang et al. (2013) and the quantitative and qualitative data collected during Experiments 1 and 2, we estimate that 5.95 ± 4.50 × 1010 cells g−1 were produced by the inoculated biomass degrading over the course of Experiment 1 (Scenario 1 in Table 2). This scenario assumed the UD morphology as an intermediate stage between protoplast germination and gamete release (100 % UD become fertile). This was considered the most realistic scenario due to observations after the end of the experiment. After the germination experiment (Experiment 2) was terminated, UDs that were green at week 5, became fertile within 2–4 weeks (Cardoso 2024). Furthermore, the material collected during this experiment was placed back in 5-L vessels for further cultivation. In these vessels the germling morphology was prevalent and after 2 weeks the UD morphology could not be found.

Estimation of seeding production through degradation (Supplementary Equations S2-S7) versus seeding output through a potential gametogenesis (under the assumption that Ulva lacinulata became fertile and based on Zhang et al. 2013).

| * | Data collected in our work | Estimations | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | GA | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | Area | Fert. area | H | I | Plantlets g−1 FW of Ulva | |

| (cell cm−2) | (cell g−1) | (%) | (cm2) | (cm2) | (Individuals g−1) | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.90 ± 1.07 × 107 | 5.11 ± 2.26 × 106 | 2 ± 0.48 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 6.07 ± 0.1 × 10−2 | 3.13 ± 1.58 × 103 | 5.15 ± 2.59 × 104 | 5.95 ± 4.50 × 1010 | 5.95 ± 4.50 × 1010 | |

| 2 | 82 ± 38.1 | 18 ± 8.66 | 5.6 ± 3.92 × 102 | 9.27 ± 6.45 × 103 | 1.07 ± 0.96 × 1010 | 1.07 ± 0.96 × 1010 | ||||||||

| * Gametogenesis (cell g−1) |

2.03 ± 1.15 × 109 | |||||||||||||

-

Estimations are divided into two possible scenarios: 1) scenario based on quantitative and qualitative data (considers UD as an intermediate stage with 100 % reproduction); 2) only quantitative data from our work. The estimations were calculated following Equations 2–7. *Legend: average data calculated based on the work by Zhang et al. (2013); GA, gametes produced per cm2; A, average protoplast yield obtained during experiment 1; B, percentage of protoplast regeneration; C, percentage of protoplasts that germinated as UGs; D, percentage of protoplasts that germinated as UDs; E, percentage of UGs that did not become fertile (non-fertile); F, percentage of UDs that did not become fertile; G, percentage of UDs that became fertile; Area, average area of one UD in cm2; Fert. area, estimated fertile area based on the percentage of fertile UDs; H (plantlets directly produced by degradation), sum of the estimated UDs and UGs which grew into adult Ulva; I (plantlets indirectly produced by degradation), estimated gametes produced by the fertile area from UD individuals, based on the average fertile UDs produced by 1 g of U. lacinulata.

By only using the quantitative data of our work (i.e., the average protoplast yields, the 2.01 ± 0.48 % germination, the 1:1 ratio between UD and UG morphologies, the 2.78 ± 0.1 mm diameter of the discs, 0.0607 ± 0.001 cm2 area of each disc, and the 18 ± 8.7 % of fertile UD’s), we estimate that 1.07 ± 0.96 × 1010 cells g−1 were produced by the inoculated biomass in Experiment 1 (Scenario 2 in Table 2). This scenario assumed that only a portion of the individuals with the UD morphology became fertile and released gametes (18 ± 8.1 %, based on the results from Experiment 2) while the remainding UDs grew into adult Ulva.

By using the estimation by Zhang et al. (2013) we estimate that direct gametogenesis of the inoculated U. lacinulata would produce 2.03 ± 1.15 × 109 cells g−1 (Gametogenesis in Table 2). In comparison, both Scenarios 1 and 2 suggest that higher seeding yields are obtained by the pathway of the degradation event with subsequent release of protoplasts and their development into UGs, UDs, and cell masses with the added early-stage fertility of cell masses and UDs than by potential gametogenesis by 1–3 orders of magnitude.

4 Discussion

4.1 Demonstration of natural protoplast production in two Ulva spp.

Our work demonstrates that protoplasts can occur naturally (i.e., without induction and addition of external factors) in both a non-sporulating species (i.e., U. lacinulata) and a sporulating species (i.e., U. compressa) and can play an important role in their life cycle and morphological development. With these findings, our work makes a clear distinction between Ulva degradation and Ulva reproduction (e.g., gametogenesis and sporogenesis) and describes degradation as an asexual reproductive method overlooked since earlier reports by Provasoli (1958) and Bonneau (1978). This is the first work in which the yield and germination rates of naturally occurring protoplasts are reported. These observations in two Ulva species that are often studied for their potential in aquaculture close an important knowledge gap in our understanding of Ulva cultivation and reproduction.

Furthermore, the origin of the material used in this work shows that our observations are not limited to cultivated material (i.e., U. lacinulata cultivated for a long period under laboratory conditions with artificial seawater) and can be found in wild material as well (i.e., U. compressa recently collected from the field and cultivated in natural seawater). Thus, suggesting that the production of protoplasts in the wild may be a common occurrence (Bonneau 1978) and widespread throughout the genus.

Finally, our work shows that germinated protoplasts with specific morphologies (UDs and cell masses) can become fertile, even if the original biomass was considered non-sporulating, such as in the case of U. lacinulata.

During degradation, U. lacinulata produced high protoplast yields, after which the inoculated biomass continued to regrow. In contrast, protoplast production in U. compressa was a by-product of reproduction that resulted in the complete loss of the inoculated biomass. While gametogenesis and sporogenesis are known as the main pathways of reproduction in Ulva spp., the connection between natural protoplast production and thalli degradation has not yet been observed or considered by the scientific community as an important step in the reproductive life cycle of Ulva spp. Adult U. lacinulata never became fertile during the two years of cultivation in this study, despite several attempts to induce reproduction (Cardoso et al. 2023). Interestingly, only the discs and cell masses that developed from protoplasts produced gametes. While the trigger causing thalli degradation and the formation of protoplasts remains unclear, pinpointing the cause and possible methods of inducing or inhibiting degradation will be an important next step for Ulva aquaculture research. On one hand, these findings will provide important information for the development of optimized and accessible protoplast isolation methods without the need for expensive enzyme solutions (Gupta et al. 2018). On the other hand, further research is needed to understand how to possibly inhibit the degradation of the thalli during its cultivation.

Contrary to our expectations that the entire biomass is lost during a degradation event, U. lacinulata thalli regenerated with high relative growth rates after degradation. At the same time, protoplasts were continually released into the water over four weeks. Because of the high variation in protoplast yields and the simultaneous growth of thalli, the relationship between protoplast production and biomass was not linear. The high variability may be related to the timing of protoplast production, which differed for each thallus piece, thus creating variation in protoplast yields. Alternatively, the high variability may be natural and dependent on the size of each piece of thalli. However, in our work, we cannot confirm this hypothesis as only the weight of the thalli was considered.

Concepts of degradation or decomposition are usually associated with the fertility of Ulva and the release of swarmers and, as a result, the complete loss of biomass (Bolton et al. 2008; Ryther 1982, 1984). However, Ryther et al. (1984) reported the fragmentation of an Ulva clone in the absence of reproduction. Considering this and our results, a distinction must be made between a reproduction event that causes total biomass loss and a degradation event.

The natural occurrence of protoplast-like cells was observed in coenocytic green macroalgae species such as Bryopsis sp., which can repair partial ruptures of the cell membrane and the wounded cell wall (La Claire 1991) after thallus fragmentation. Furthermore, this process was considered a method of propagation in Bryopsis sp. since it can spontaneously generate high yields of viable new cells (Kim et al. 2001). In Ulva, the natural regeneration of protoplast-like cells has been reported by Provasoli (1958) and Bonneau (1978) who worked with U. lactuca cultures. They reported “green island” cells or sloughed Ulva cells with the capacity to produce new germlings without previous swarmer formation (i.e., asexually), but the term “protoplast” was not used. These findings agree with our observations and our hypothesis that the natural occurrence of protoplasts is not limited to non-sporulating species grown in laboratory conditions (i.e. U. lacinulata) and can be observed in wild and fertile material (i.e. U. compressa). However, the number of cells showing this germination capacity was not calculated by Provasoli (1958) or Bonneau (1978). Hitherto, only artificial protoplast isolation methods report yields and regeneration/germination rates (Gupta et al. 2018; Reddy and Seth 2018). By following established methods for protoplast isolation (Gupta et al. 2018; Reddy and Seth 2018), we were able to document and quantify the natural production of protoplasts in two Ulva spp. without inducing cell wall degradation using enzyme solutions.

4.2 Protoplast germination and morphological development

The germination rates of the protoplasts reported in our study are low compared to previous reports using artificially induced protoplasts (Gupta and Reddy 2018; Gupta et al. 2018; Reddy et al. 2006). The regeneration of cell walls and subsequent development of isolated protoplasts in Ulva spp. is well documented and follows a pattern similar to that observed in our study (Gupta et al. 2018; Reddy and Seth 2018). However, the purpose of comparing our results with existing literature is not to evaluate the efficiency of long-established, enzyme-based methods, but to highlight the relevance of naturally occurring protoplasts as a viable source of seeding material. This comparison must be contextualized, as our study was conducted under entirely different conditions, without inducing protoplast formation or manipulating environmental parameters to optimize seeding yields. Isolation of protoplasts usually requires incubation of Ulva thalli in darkness (or low light) at high temperature (e.g., 25 °C) for two to 3 h with an enzymatic mixture and the isolated protoplasts are kept under the same conditions for 24 h (Gupta and Reddy 2018; Gupta et al. 2018; Salvador and Serrano 2005; Reddy et al. 2006). Instead, in our work protoplasts were released into the water gradually and germinated under standard cultivation settings (15 °C, 70 μmol photons m−2 s−1), and we deliberately avoided medium exchange to minimize stress. Despite this passive approach, germling (AGs) development confirmed the suitability of our conditions. Moreover, while previous studies often assess success based on cell survival or cell wall regeneration rates, we focused solely on the emergence of macroscopic individuals, offering a practical measure of seeding potential in natural settings.

Our comparison with previous studies highlights important questions about how protoplast regeneration success is measured. To our knowledge, our study is the only one that tracks protoplast development continuously over a five-week period, from initial isolation to the formation of macroscopic individuals (germlings or discs). This extended observation allowed us to detect fertility in discs and cell masses (Figure 11), an aspect overlooked in studies that assess success primarily through short-term indicators like survival or cell wall regeneration, typically within three days. As a result, key developmental behaviours, including sporulation and morphological differences, may have been missed. Consequently, reported germination rates in the literature (e.g., Gupta et al. 2018; Gupta and Reddy 2018) may be overestimated, as it’s unclear whether co-occurring reproduction was accounted for, or at what developmental stage germlings were evaluated. The moment at which regeneration/germination rates are quantified is important, as the occurrence of fertile cell masses (in our work and reported by Gupta et al. 2018) can cause miscalculations of the germination rates. Reddy and Seth (2018), Gupta et al. (2018), and Gupta and Reddy (2018) assume that all germlings or microscopic groups of cells came from protoplasts and regeneration rates were > 87 %. However, our findings suggest that cell masses and small discs became fertile and released gametes at a very early stage (between the second and third week) in our experiments (Figure 11). Thus, it is possible that the resulting germlings counted in protoplast isolation studies, which give results higher than 87 %, originated both from regenerating protoplasts and subsequent gametogenesis/sporogenesis.

![Figure 11:

Visual representation of our observations of morphological development after natural protoplast release. For the representation, pictures from the experiment with Ulva lacinulata were used. Ulva compressa followed the same process. W1-5 represent the weeks when the different development stages were observed. [Graphical design created in Canva (Canva n.d.)].](/document/doi/10.1515/bot-2025-0017/asset/graphic/j_bot-2025-0017_fig_011.jpg)

Visual representation of our observations of morphological development after natural protoplast release. For the representation, pictures from the experiment with Ulva lacinulata were used. Ulva compressa followed the same process. W1-5 represent the weeks when the different development stages were observed. [Graphical design created in Canva (Canva n.d.)].

Following the main regeneration experiment, a supplementary assay was conducted to confirm gametogenesis in unattached discs (UDs) and to observe the morphology of the individuals developed from gametes. Brown (fertile) and green (non-fertile) UDs were placed in Petri dishes with fresh medium. Microscopic observations confirmed gametogenesis, and positive phototaxis confirmed the presence of gametes. All gametes released from the UDs attached to the Petri dish and developed into single-branched germlings with a distinct rhizoid. The observations in this supplementary experiment, detailed in Cardoso (2024), together with the main findings of our work, suggest that rhizoid formation in germlings depends on their origin, either from protoplast or gametes. Specifically, germlings derived from protoplasts were branched but lacked rhizoids, while those from gametes were unbranched and possessed rhizoids (Cardoso 2024). The literature is ambiguous regarding the morphology presented by germinated protoplasts. Some report germinated Ulva protoplasts with no visible rhizoids (Gupta et al. 2012, 2018; Wu et al. 2018) while others report the presence of rhizoids (Rusig and Cosson 2001; Reddy and Seth 2018). This, again, suggests that some of the reported germinated protoplasts might have originated from gametogenesis instead. Figure 11 summarizes the timeframe of degradation and development of new individuals and details at which moment each of the different morphologies was observed. It should be noted that during this work and in separate observations, floating clusters of germlings were seen growing on top of former fertile UDs (Supplementary Figure S5E; Cardoso 2024). These clusters were counted as one single fertile disc during the experiment.

Morphologies such as UDs and UGs are known to co-occur after protoplast isolation and germination (Gupta et al. 2018; Reddy and Seth 2018). However, the reason behind the co-occurrence of these morphologies is not clear. The main suggestions in the literature are twofold: 1) level of methylation associated with temperature. Gupta et al. (2012) reported that the ratio between the two morphologies varied depending on temperature and the level of methylation. To our knowledge, our work is the first to report a 1:1 ratio between discs (UD) and germlings (UG). 2) totipotency of the cells in the vegetative thalli. It has been suggested that the different morphologies observed after protoplast isolation or production might be caused by the different potency of the cells and their differentiation when still attached to the thalli (Bonneau 1978; Provasoli 1958; Reddy et al. 1989). This agrees with our findings, that during degradation (in the case of U. lacinulata) or reproduction (in the case of U. compressa), the thalli become heterogeneous and two different cell types are found: those that either die or form swarmers, and the spherical green cells that become protoplasts. Later, the same occurred in the fertile UDs which had developed from protoplasts (U. lacinulata), where a small portion of cells again became protoplasts. This suggests that protoplast production is not limited to degradation and protoplasts are also produced by fertile thalli thereby also agreeing with our observations in U. compressa.

4.3 The reproductive efficiency of gametogenesis versus protoplast production

Following the considerations in 4.2., if we consider the average production of protoplasts collected from U. lacinulata after 4 weeks our results represent 6.86 ± 3.04 % and 6.42 ± 2.84 % of the protoplast yields reported by Gupta and Reddy (2018) in U. lactuca (wild) and Ulva rigida, respectively. Moreover, the highest protoplast yields reported (third week of the experiment) represent only 10.23 ± 6.64 and 9.57 ± 6.22 % of the yields reported by Gupta and Reddy (2018), respectively. However, if we consider the average number of new Ulva individuals estimated to be obtained after degradation (5.95 ± 4.50 × 1010 cells g−1; Scenario 1 in Table 2; Figure 12), our results are higher than the yields reported by Gupta and Reddy (2018) by factors of 7.99 ± 7.60 × 102 (U. lactuca) and 7.48 ± 7.12 × 102 (U. rigida). Thus suggesting that degradation with protoplast formation can produce higher seeding yields than well-established protoplast-isolation methods. Furthermore, the resulting estimations (both scenarios) between the number of individuals produced by degradation and by gametogenesis suggests that Ulva degradation can be a more efficient reproductive strategy than gametogenesis of parental thalli alone.

![Figure 12:

Life cycle of NE-Atlantic Ulva lacinulata based on asexual reproduction via protoplast production and estimation of the number of individuals (in cells g−1) that would be produced during a degradation event (Scenario 1 in Table 2). This estimation was compared with the number of individuals produced if U. lacinulata became fertile and released gametes (2.03 ± 1.15 × 109 cells g−1). Grey lines in the opposite direction indicate the partial regrowth of the biomass (amounting to 8 times the original weight of the thalli) and the release of protoplasts by the fertile discs. Legend: n.c.: “not counted”, cell masses, protoplasts produced by the fertile discs, and gametes released by the cell masses were not considered for this estimation. [Graphical design created in Canva (Canva n.d.)].](/document/doi/10.1515/bot-2025-0017/asset/graphic/j_bot-2025-0017_fig_012.jpg)

Life cycle of NE-Atlantic Ulva lacinulata based on asexual reproduction via protoplast production and estimation of the number of individuals (in cells g−1) that would be produced during a degradation event (Scenario 1 in Table 2). This estimation was compared with the number of individuals produced if U. lacinulata became fertile and released gametes (2.03 ± 1.15 × 109 cells g−1). Grey lines in the opposite direction indicate the partial regrowth of the biomass (amounting to 8 times the original weight of the thalli) and the release of protoplasts by the fertile discs. Legend: n.c.: “not counted”, cell masses, protoplasts produced by the fertile discs, and gametes released by the cell masses were not considered for this estimation. [Graphical design created in Canva (Canva n.d.)].

Even though our estimations for seeding production were calculated based on work done with a different Ulva species, the data presented by Zhang et al. (2013) are in the same range as with other Ulva species (U. compressa and Ulva linza; Hoxmark and Nordby 1974; Fjeld and Løvlie 1976; Vesty et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2022). However, it should be considered that cell shape and size vary between Ulva species. U. prolifera has been reported to present a cell diameter between 6.46 µm (long axis) and 3.03 µm (short axis; Zhao et al. 2023). In our work, cells of U. lacinulata varied in diameter between their vegetative state at the beginning of degradation, the pre-protoplast formation (round cells still attached to the thalli), and as single protoplasts, with the pre-protoplasts and protoplasts being larger than the vegetative cells, as shown in Figure 4C and D. Additionally, it should be considered that the number of cell masses developing from protoplasts and the subsequent production of gametes were not considered in our estimations. Therefore, our calculations are still an underestimation of the real seeding yield obtained at the end of the experiment. Figure 12 summarizes our observations and reports the estimated number of individuals that would be produced, per gram, during a degradation event (Scenario 1 in Table 2).

4.4 Ulva–bacteria interactions as a plausible underlying factor

Bacterial communities can impact the structural integrity of the algal thallus (Tanaka et al. 2022; Waite and Mitchell 1976) and its correct development through the secretion of algal growth and morphogenesis-promoting-factors (AGMPFs) by specific bacteria (e.g., thallusin, associated with callus differentiation and rhizoid development; Spoerner et al. 2012; Wichard et al. 2015; Alsufyani et al. 2017; Wichard 2023). These well-established interactions are a possible justification for the cell wall degradation and regeneration reported in our work (Reddy and Seth 2018; Tanaka et al. 2022), which are a starting point for a broader discussion on the co-occurrence of distinct morphologies and the simultaneous presence of fertile and non-fertile individuals. It is unlikely that the co-occurrence of different morphologies and reproduction patterns stems from differences in the bacterial community between individuals, as they were growing in the same culture medium under the same conditions. Still, these outcomes may depend on the relative abundance, spatial distribution, or functional activity of the present bacteria. In the work of Bonneau (1978), the co-occurrence of the same morphologies in both wild and axenic cultures was reported. These findings contrast with recent literature, where axenic Ulva consistently fails to develop differentiated structures (Ghaderiardakani et al. 2020; Spoerner et al. 2012; Wichard 2015). These disparities likely stem from differences in the methodologies employed to achieve and verify the axenic conditions. It is plausible that the axenic status of Bonneau’s cultures was incomplete, and that the microbial community, though reduced, was still functionally present. If so, his observations may reflect a microbial imbalance rather than the complete absence of microbial partners. In this context, our observations of similar structures in laboratory-cultured U. lacinulata and wild U. compressa may likewise result from subtle disruptions to the holobiont equilibrium. Therefore, future work should consider studying the impact of holobiont disruptions (quantity and quality) and variations in production of associated AGMPFs during degradation and protoplast isolation methods.

Within the scope of our work, we were able to associate the presence and absence of rhizoids with the origin of the attached and unattached germlings (gametes and protoplasts, respectively). This suggests that thallusin and the correct bacteria were present in the medium and that other factors indirectly related to bacteria could have influenced the co-occurrence of different morphologies and early-stage reproduction. This includes cell wall quality (Gupta et al. 2012) or cell wall permeability. The latter can also negatively influence the secretion of sporulation inhibitors by the Ulva into the surrounding medium or their retention between the two cell layers (Alsufyani et al. 2017; Stratmann et al. 1996; Vesty et al. 2015; Wichard et al. 2015). Future work should consider the importance of cell wall quality on Ulva-bacteria interactions and its effect on reproduction in different types of Ulva cells (i.e., protoplasts, gametes, and spores).

4.5 Ecological relevance of natural protoplast production