Abstract

This paper extends a standard New Keynesian model by introducing anticipated shocks to inflation, output, and interest rates, and by incorporating forward-looking, forecast-targeting Taylor rules. The latter aspect is parsimoniously modeled through the presence of an expected future interest rate term in the Taylor rule that recent literature has found to be economically and statistically important in a variety of settings without anticipated shocks. Using Bayesian econometric methods, we find that the presence of anticipated shocks improves the model’s fit to the US data but substantially decreases the weight on future macroeconomic variables in the forward-looking Taylor rule. Our results suggest that, although communicating its intentions regarding future monetary policy conduct, as modeled by anticipated monetary shocks, plays an important role for the Fed, responding to its expectations of future macroeconomic conditions does not. Furthermore, we conduct extensive robustness checks with respect to modeling the forward-looking specification of the Taylor rule that confirm our baseline results.

1 Introduction

Over the last couple of decades, the primary focus of the New Keynesian literature has been to study how monetary policy can stabilize a macroeconomy in response to stochastic shocks that generate social welfare losses due to nominal or real frictions. A popular device for modeling monetary policy conduct has been the so-called Taylor rule, initially proposed by Taylor (1993) as a descriptor of the Federal Reserve interest setting behavior in response to output gap and inflation that is typically augmented with at least one lag of the nominal interest rate to address strong persistence in the evolution of the federal funds rate (FFR). In its original formulation that has carried over into much of the New Keynesian DSGE literature, the Taylor rule posits that every time period the central bank sets the nominal interest rate in responses to the concurrent measures of inflation and real activity. While there is some empirical evidence that investigates the possibility that the Fed may set the FFR rate target in a forward-looking fashion by responding to forecasts of inflation and output gap, as in, for instance, early contributions of Clarida, Galí, and Gertler (2000) and Batini and Haldane (1999), such forecast-based, forward-looking rules have generally been less exploited in the DSGE literature, possibly due to their well documented propensity to generate indeterminacy relative to the case where the nominal interest rate is set in response to concurrent inflation and output gap.[1]

Levine, McAdam, and Pearlman (2007) propose a Calvo-type approach to forecast-based rules that parsimoniously incorporates forward-looking central bank behavior. They augment the standard Taylor rule (STR) with a term reflecting the current expectations of the the future nominal interest rate that will be set in response to future inflation rates and, possibly, output gaps, thus adding to the discussion of the sources of observed inertia in interest rate setting.[2] They also document that this Calvo-type approach to motivating a forward-looking Taylor rule (FTR) has desirable determinacy properties and its presence appears to be significant in the US data using Bayesian estimation of a New Keynesian DSGE model similar to the one employed in this paper. Gabriel, Levine, and Spencer (2009) find that the presence of the forward-looking interest rate term is robust to alternative assumptions regarding the relative importance of forecasts of inflation and output gap using single-equation generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation. Bache, Roisland, and Torsten (2011) reinterpret the presence of this term as motivated by the central bank’s desire to smooth the evolution of the nominal interest rate relative to the target rate and also find economically and statistically significant effects of that term using multi-equation maximum likelihood methods. This forward-looking behavior should amplify the effect of information regarding the future state of the macroeconomy on present outcomes. However, this paper’s main finding is the much diminished role for the forward-looking interest rate term once the news shocks to monetary policy are introduced into a standard New Keynesian model. Therefore, news about the future macroeconomic conditions affect present outcomes through channels other than the Taylor rule, such as aggregate demand and aggregate supply.

The literature on news or anticipated shocks to macroeconomic variables began with researchers’ interest in the effect of anticipated shocks to technology.[3] Subsequently, the literature on the non-technological sources of news shocks has rapidly developed.[4] The empirical approach pursued in the present paper is closely related to the work of Milani and Treadwell (2012) in terms of the sources of news shocks and Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2012) in terms of their identification. Milani and Treadwell (2012) focus on anticipated monetary shocks and show that the response of macroeconomic variables to monetary “news” about the future conduct of policy is much stronger than to contemporaneous “surprises.” Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2012) provide a rule of thumb for setting the priors for the standard deviations of news shocks relative to contemporaneous surprises that ensures that their magnitude is not excessive.

Our main finding regarding the Taylor rule description of interest-setting behavior provides a stark answer to a horse race between two modes of thinking about the forward-looking nature of monetary policy conduct. One, parsimoniously summarized through the Calvo-type Taylor rule by Levine, McAdam, and Pearlman (2007), posits that the central bank sets nominal interest rates in response to its expectation of the future macroeconomic conditions.[5] The other, introduced by Milani and Treadwell (2012), highlights the role of monetary news, which can be viewed as announcements regarding the future conduct of policy.[6] We find that the forward-looking components in the Taylor rule become empirically unimportant, once one accounts for the presence of anticipated monetary shocks. Importantly, models featuring these monetary news shocks have the best fit with the data. This finding suggests that the Federal Reserve’s exploiting private agents’ expectations of the future with monetary policy announcements is more quantitatively important than its setting interest rates in response to forecasts of future macroeconomic conditions.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a description of our small-scale theoretical model of the US economy. Section 3 describes our dataset and outlines our estimation strategy. Section 4 describes our baseline empirical results. Section 5 conducts various robustness checks that confirm our baseline findings. Finally, Section 6 concludes.

2 Model summary

Our theoretical setting is a variant of the standard New Keynesian model that, over the last two decades, has become the workhorse for the analysis of monetary policy. We follow Milani and Treadwell (2012) among others and use structural equations as derived from explicit microfoundations while, for simplicity and parsimony, treating exogenous shocks as disturbances to the endogenous variable whose evolution a particular equation describes. These shocks may be convolutions of several preference or technological shocks in a more explicitly microfounded setting.

The model has three sectors whose behavior is characterized by corresponding structural equations that describe the evolution of endogenous variables’ departures from the steady state. First, households maximize a discounted stream of utility from leisure and quasi-growth in consumption and are able to store wealth through bonds in the complete-markets setting. The first-order conditions for their optimization problem yield the so-called IS schedule:

where b is the degree of habit formation in consumption, which is used to reflect the observed persistence in real macroeconomic activity, σ is the inverse coefficient of relative risk aversion to changes in quasi-growth of consumption, yt is output gap whose difference from consumption is swept into the exogenous demand shock

As is standard in this strand of the literature, we assume monopolistically competitive firms whose decision to set optimal prices is subject to the Calvo (1983) pricing friction. The evolution of inflation that can be derived in this setting is described by the so-called Phillips curve:

where β is the exogenous discount factor, ωp reflects the share of firms who index prices to last period’s inflation when they are not able to set them optimally,

Finally, the central bank is assumed to set the nominal interest using the following forward-looking version of the Taylor rule:

We use the parsimonious specification derived by Gabriel, Levine, and Spencer (2009) for the Calvo-type forecast-based Taylor rules introduced by Levine, McAdam, and Pearlman (2007). The specification assumes that the central bank uses the same forecast horizons for both output gap and inflation. Gabriel, Levine, and Spencer’s (2009) interpretation of the Calvo-type of rule, is a feedback rule responding to expected inflation and output gap forecasts, with an attached probability of continuing of ξ, and a probability of (1–ξ) of switching off. Therefore, the mean forecast horizon is ξ/(1–ξ), whose first derivative with respect to ξ is positive. Bache, Roisland, and Torsten (2011) derive a Taylor rule that is almost identical to (3) in its functional form while providing an alternative motivation by assuming that the central bank smoothes the evolution of the nominal interest rate around the target level.

Intuitively, the impact of forward-looking behavior on the evolution of endogenous variables should be magnified in the presence of information about the future macroeconomic conditions. To model that latter aspect, we assume that innovations in our three structural equations evolve according to the following processes:

and

where

3 Data, Bayesian estimation strategy, and theoretical impulse responses

We estimate the set of structural parameters, autocorrelation coefficients, and standard deviations of anticipated and unanticipated innovations using likelihood-based Bayesian techniques; see An and Schorfheide (2007) for a comprehensive methodological overview. For our baseline specification, structural parameters represent a 22×1 vector Θ defined as:

As is common in the literature, some parameters were fixed during the estimation strategy. Following Milani and Treadwell (2012) and Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2012), we set the household’s discount factor β, to 0.99, the Frisch labor supply elasticity η to 2, and the intertemporal elasticity of substitution σ to 1. The vector of observed variables consists of the output gap, the inflation rate, and the federal funds rate Yt=[yt, πt, rt]. A prior distribution is assigned to the parameters of the model and is represented by p(Θ). The Kalman filter is used to evaluate the likelihood function given by p(YT|Θ), where YT=[Y1, …, YT]. Lastly, the posterior distribution is obtained by updating prior beliefs through Bayes’ rule, taking into consideration the data reflected in the likelihood.

The model’s state space representation including news shocks follows Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2012) and Milani and Treadwell (2012); it can be written in the following form:

where

We generate draws from the posterior distribution through the random-walk Metropolis-Hastings algorithm.[7] For each model specification, we ran 500,000 iterations, discarding the initial 20% as burn-in. In addition, we ran several other chains with different initial values obtaining similar results.

3.1 Data

Estimation was performed using quarterly data on output gap, inflation, and nominal interest rates. Inflation is measured as the quarterly change in the GDP Implicit Price Deflator. The output gap is the log difference of the GDP and potential GDP estimated by the Congressional Budget Office. Lastly, the nominal interest rate is represented by quarterly levels of the federal funds rate. All data used were taken from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Data website (FRED2 database) and cover the time period from 1954Q2 to 2011Q2. In the next section, we also conduct a robustness check that excludes the earliest data in the sample, as well as the latest one associated with the Great Recession, and only covers 1960Q1–2007Q4, which is a time sample frequently used by other authors.

3.2 Priors

Priors for the estimated parameters are summarized in Table 1. Their values for the degree of price inflation indexation, interest smoothing parameter, and Calvo price stickiness follow a beta distribution with means of 0.7, 0.7, and 0.5, respectively, and standard deviation of 0.2 following Milani and Treadwell (2012). The prior for the degree of habit persistence has a mean of 0.5 and a standard deviation of 0.16. Although slightly lower than the value used in other studies, this prior mean is consistent with previously estimated posterior means for this parameter, as in, among others, Smets and Wouters (2007). Importantly, this shape of the prior distribution prevents posterior peaks from being trapped at the upper corner of the respective estimation intervals set between 0 and 1. The autoregressive coefficients in consumption Euler equation, the NKPC, and the Taylor rule take Normal distributions centered at 0.5 and with standard deviations of 0.15. The magnitude for the response to inflation and the output gap in the Taylor rule also take Normal distributions centered at 1.5, and 0.5, with the latter value slightly higher than in Milani and Treadwell (2012).

Parameter description and priors – gamma for errors and medium exogenous persistence.

| Parameters | Description | Dist. | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | Degree of habit persistence | B | 0.50 | 0.16 |

| θp | Calvo probability of price stickiness | B | 0.50 | 0.16 |

| ωp | Degree of price indexation | B | 0.70 | 0.17 |

| ρ | Interest-smoothing parameter | B | 0.70 | 0.17 |

| γp | Magnitude of response to inflation target | N | 1.50 | 0.25 |

| γy | Magnitude of response to output gap target | N | 0.50 | 0.12 |

| ρy | Exogenous persistence of demand shock | N | 0.50 | 0.23 |

| ρr | Exogenous persistence of monetary shock | N | 0.50 | 0.15 |

| ρp | Exogenous persistence of supply shock | N | 0.50 | 0.15 |

| ξ | Degree of forward-looking monetary policy (if present) | B | 0.60 | 0.12 |

| σy | Standard deviation of demand shock, concurrent only | Γ | 0.34 | 0.30 |

| σr | Standard deviation of monetary shock, concurrent only | Γ | 0.34 | 0.30 |

| σp | Standard deviation of supply shock, concurrent only | Γ | 0.34 | 0.30 |

| σy | Standard deviation of demand shock, concurrent, with news | Γ | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| σr | Standard deviation of monetary shock, concurrent, with news | Γ | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| σp | Standard deviation of supply shock, concurrent, with news | Γ | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| σy,n | Standard deviation of demand shock, news onlya | Γ | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| σr,n | Standard deviation of monetary shock, news onlya | Γ | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| σp,n | Standard deviation of supply shock, news onlya | Γ | 0.10 | 0.15 |

aStructure of news shocks with h=4, 8, and 12. The symbols for the prior distributions stand for B=beta, N=normal, and Γ=gamma distributions.

Our approach to modeling the forward-looking component of the Taylor rule conduct follows Gabriel, Levine, and Spencer (2009) and is very close to Bache, Roisland, and Torsten (2011). Using single-equation GMM estimates of the forward-looking Taylor rule, Gabriel, Levine, and Spencer (2009) find that the value of ξ is in the 0.60–0.98 range (depending on the measure of real activity and the estimation technique being used) in the post-war data. Bache, Roisland, and Torsten (2011) report estimates of about 0.4–0.5 using maximum likelihood methods and more recent data. To capture these possibilities, we assign a fairly diffuse prior for this parameter that follows the beta distribution with a mean of 0.6 and a standard deviation of 0.12, yielding a prior probability interval consistent with the range of values previously estimated in the literature.

We follow Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2012) and Milani and Rajbhandari (2012) in our treatment of the priors for the standard deviations of anticipated and unanticipated shocks in two important directions. First, we assign the priors for the standard deviations of the unanticipated and anticipated innovations to follow the gamma distribution. Although the inverse gamma distributions are commonly used as priors for standard deviations, as is well known, their use may push the estimates of shocks’ standard deviations away from zero. Our use of the gamma distribution, on the other hand, assigns a positive probability that the standard deviations of anticipated innovations could take a value of zero, thus capturing the possibility that news shocks play an insignificant role in the dynamics of the model. Second, we assume that 75% of the variance of observed disturbances is driven by the unanticipated component. More specifically, if σq is the standard deviation of the observed shock εq where q=[y, p, r], the variance of its concurrent component σc,q is given by:

and its news components by:

where the weight of the unanticipated component is set to w=0.75. Variances of individual news shocks at different horizons h can be constructed using:

where N is the number of news shocks at different horizons. These assumptions on the priors give limited scope to the anticipated shocks. Hence our priors need to be overwhelmed by the data to find a significant role for them.

3.3 Theoretical impulse responses

In this subsection, we investigate whether the addition of the forward-looking interest rate term has a significant impact on the transmission of exogenous shocks. We begin our analysis by studying theoretical impulse responses with all parameter values set at their prior means in Table 1 except for ξ. We set that parameter to 0, 0.3, 0.6, or 0.69, keeping these values below the prior for ρ of 0.7, since Levine, McAdam, and Pearlman (2007) show that determinacy requires that ξ<ρ. We perform this exercise in the specification with all three types of long-run news shocks, as it provides the most comprehensive insight into the effect of different one-standard-deviation shocks under the alternative values for ξ.[8]

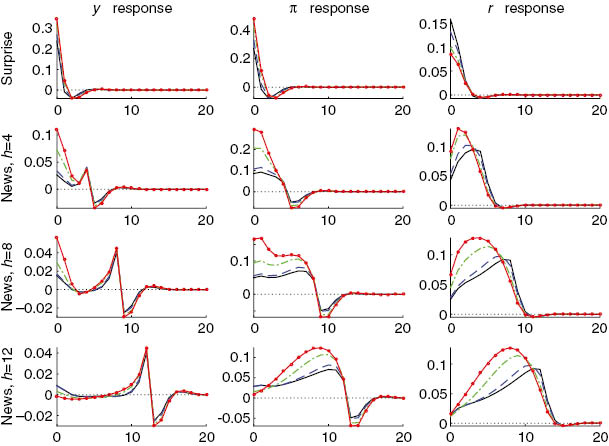

Figure 1 demonstrates the theoretical impulse responses of endogenous variables to surprise and anticipated demand shocks. The key intuition about the effect of higher values of ξ may be gleaned from comparing the effects of surprise and news shocks at shorter horizons versus those of the news shocks at longer horizons. The immediate effect of ξ increases is that the central bank tempers its interest rate response to current output gap and inflation, allowing their equilibrium values to increase. Given the persistence in inflation and output gap, that means somewhat higher values of these variables in the future, which, through the forward-looking interest rate terms has a positive effect on the interest rate. This explains why both output gap and inflation are more sensitive to surprise and news shocks with h=4 under higher values of ξ. For the interest rate, the immediate effect dominates the forward-looking one for surprise shocks and the converse is true for news shocks. As the news shock horizon increases, the effect of the forward-looking term becomes more and more dominant, so much so that for h=12 output gap and inflation decrease in response to a positive anticipated demand shock as soon as it becomes known. In general, all three variables become more sensitive to demand shocks and hence more volatile, as the value of ξ and the the news shock horizon increase.[9]

Theoretical impulse responses to demand shocks: solid black line – ξ=0; dashed blue line – ξ=0.3; punctuated green line – ξ=0.6; solid red line with circles – ξ=0.69.

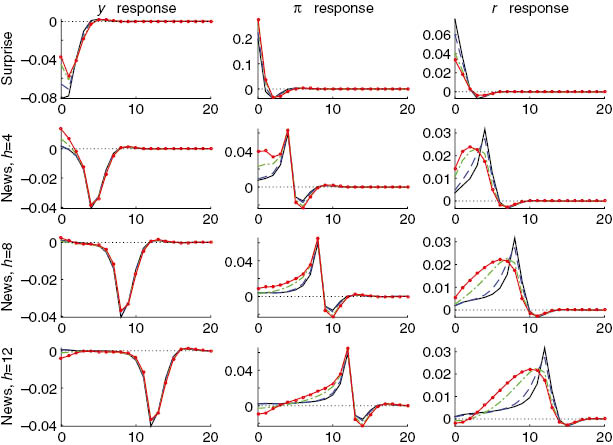

Figure 2 provides similar analysis for the endogenous variable responses to supply shocks. The intuition is similar to the one conveyed by Figure 1 for demand shocks with the main difference being that output gap dynamics due to the different supply shocks remain largely unaffected by changes in the value of ξ. Again, the immediate response of the interest rate rate to inflationary pressure decreases as ξ increases, which allows the pressures to build up going forward and brings about a stronger secondary response due to the forward-looking interest rate term in the monetary policy rule. As a result, the volatility of inflation and interest rate increase markedly at higher levels of ξ.

Theoretical impulse responses to supply shocks: solid black line – ξ=0; dashed blue line – ξ=0.3; punctuated green line – ξ=0.6; solid red line with circles – ξ=0.69.

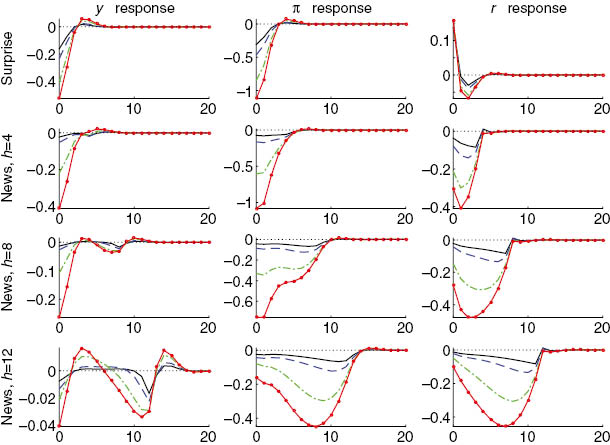

Finally, Figure 3 describes the effect of different types of monetary shocks. A contractionary monetary surprise shock generates decreases in inflation and output gap that, given their inertial behavior, persist into the future. Anticipation of the future recession through the forward-looking interest rate term makes then central bank reduce the interest rates by larger amounts for higher values of ξ, eventually making output gap and inflation overshoot into the positive territory on the way to their adjustment to the steady state. Similar intuition holds for news shocks except that anticipation of a future recession driven by a contractionary monetary shock is so strong that the equilibrium interest rate actually falls and briefly ventures into the positive territory when the anticipated shock materializes h time period ahead. The strength of these dynamics increases with anticipation horizon h and the central bank’s forecast horizon ξ.

Theoretical impulse responses to monetary shocks: solid black line – ξ=0; dashed blue line – ξ=0.3; punctuated green line – ξ=0.6; solid red line with circles – ξ=0.69.

In sum, the presence of news shocks in the empirical model clearly has far-reaching implications for identifying our main parameter of interest, ξ. As ξ increases, endogenous variable responses generally become stronger, although this effect is more pronounced for demand and monetary shocks and less so for supply shocks. This volatility increases with the news anticipation horizon, h, and may imply that variables move in the opposite direction of the one given by the shock, due to the model’s endogenous mechanism, as is the case for the equilibrium interest rate in response to monetary news shocks. These results are likely to set up a horse race between the forward-looking term in the Taylor rule and anticipated shocks, especially monetary news, since the strong presence of both is likely to generate implausible dynamics.

4 Results

In this section, we evaluate the contributions of the forward-looking interest rate term and news shocks to the baseline New Keynesian model discussed above. We find that the models with anticipated shocks to the Taylor rule fit data the best. It turns out to be the case that those models also imply low estimates of parameter ξ. Impulse responses of inflation and output gap implied by the estimated parameters are much larger in response to news shocks than to surprises while the presence of the forward-looking interest term does not affect them much. The evidence presented in this section, therefore, points to the quantitative insignificance of this term.

4.1 Parameter estimates

Table 2 reports the posterior mean estimates along with the 95% posterior probability intervals (PPI) of the more parsimonious specifications with respect to the structure of news shocks that provide the closest functional form fit with available parameter estimates in models that do not feature anticipated shocks. We refer to the preferred specification with the forward-looking interest term in the Taylor rule and the long-run identification of the monetary news shocks as “FTR+MN”. For all of the specifications that we have estimated, we have calculated the Bayes factor, taking “FTR+MN” as the baseline model.[10] Panel A of Table 2 focuses on the parameter estimates of ξ and the standard deviations of the monetary news shocks.

Parameter estimate posteriors.

| Parameter | FTR+MN | FTR+NoN | STR+NoN | FTR+SRN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | PPI | Mean | PPI | Mean | PPI | Mean | PPI | |

| Panel A: “Forward-looking” parameter (ξ) and news shocks | ||||||||

| ξ | 0.251 | [0.112, 0.396] | 0.641 | [0.436, 0.821] | 0.257 | [0.065, 0.514] | ||

| σy1 | 0.042 | [0.001, 0.118] | ||||||

| σp1 | 0.017 | [0.001, 0.049] | ||||||

| σr1 | 0.063 | [0.003, 0.130] | ||||||

| σy2 | 0.093 | [0.003, 0.236] | ||||||

| σp2 | 0.020 | [0.001, 0.058] | ||||||

| σr2 | 0.118 | [0.026, 0.176] | ||||||

| σy3 | 0.083 | [0.004, 0.239] | ||||||

| σp3 | 0.022 | [0.001, 0.061] | ||||||

| σr3 | 0.030 | [0.001, 0.082] | ||||||

| σy4 | 0.186 | [0.010, 0.392] | ||||||

| σp4 | 0.136 | [0.089, 0.179] | ||||||

| σr4 | 0.027 | [0.000, 0.098] | 0.087 | [0.005, 0.162] | ||||

| σr8 | 0.172 | [0.129, 0.205] | ||||||

| σr12 | 0.026 | [0.000, 0.110] | ||||||

| Marg. L | –344.62 | –356.19 | –351.69 | –400.61 | ||||

| BF | 1 | 9*10−6 | 9*10−6 | 2*10−12 | ||||

| Panel B: Other parameters | ||||||||

| b | 0.538 | [0.429, 0.653] | 0.843 | [0.748, 0.917] | 0.883 | [0.817, 0.930] | 0.492 | [0.262, 0.762] |

| θp | 0.952 | [0.938, 0.964] | 0.962 | [0.947, 0.976] | 0.961 | [0.945, 0.975] | 0.935 | [0.918, 0.952] |

| ωp | 0.896 | [0.789, 0.982] | 0.865 | [0.768, 0.960] | 0.887 | [0.796, 0.973] | 0.135 | [0.037, 0.279] |

| ρ | 0.870 | [0.829, 0.905] | 0.842 | [0.785, 0.891] | 0.836 | [0.784, 0.886] | 0.849 | [0.796, 0.893] |

| γp | 1.991 | [1.658, 2.333] | 1.730 | [1.435, 2.010] | 1.309 | [1.022, 1.613] | 1.640 | [1.234, 2.078] |

| γy | 0.321 | [0.200, 0.486] | 0.327 | [0.182, 0.539] | 0.227 | [0.127, 0.361] | 0.455 | [0.306, 0.633] |

| ρr | 0.095 | [0.013, 0.217] | 0.254 | [0.123, 0.405] | 0.287 | [0.164, 0.407] | 0.199 | [0.033, 0.436] |

| ρy | 0.880 | [0.804, 0.938] | 0.607 | [0.434, 0.740] | 0.516 | [0.368, 0.652] | 0.658 | [0.164, 0.867] |

| ρp | 0.063 | [0.022, 0.127] | 0.064 | [0.030, 0.103] | 0.049 | [0.023, 0.089] | 0.259 | [0.086, 0.503] |

| σr | 0.030 | [0.001, 0.077] | 0.124 | [0.101, 0.152] | 0.222 | [0.202, 0.244] | 0.070 | [0.007, 0.113] |

| σy | 0.140 | [0.105, 0.182] | 0.236 | [0.183, 0.300] | 0.269 | [0.213, 0.335] | 0.186 | [0.059, 0.304] |

| σp | 0.174 | [0.157, 0.194] | 0.169 | [0.153, 0.189] | 0.171 | [0.154, 0.190] | 0.144 | [0.109, 0.176] |

The first two columns feature estimation results from specifications where only the monetary shock has a news component under the forward-looking (“FTR+MN”) or standard (“STR+MN”) Taylor rule. While the introduction of the forward-looking term yields a dramatic increase in the marginal likelihood, the estimated value of ξ in the latter specification is quite low at only 0.251 with a posterior probability interval that contains a value close to zero: [0.112, 0.396]. This suggests that the forecast targeting is only one month, which is barely frequent enough to bridge the gap between at most half of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings. Importantly, the standard deviations of the monetary news shocks are quite large, especially at the 8-quarter anticipation horizon when they are larger than the standard deviations of monetary surprises. This suggests an economically significant role for the anticipated shocks to interest rates.

We next report the results for the more traditional specifications that do not feature news shocks at all. The model with the forward-looking term (“FTR+NoN”) has a posterior mean value for ξ of 0.641, which is in line with the previously reported results. This estimate suggests a forecast horizon of close to two quarters, with a confidence interval of 1–4.5 quarters, which is economically significant and matches the forecast horizons used in non-Calvo forward-looking rules by Clarida, Gali, and Gertler (2000), Orphanides and Wieland (2008), and Mavroeidis (2010) among others. However, the likelihood associated with this model is lower than that of “FTR+MN”. It is also lower that the likelihood of the model without news shocks and the standard Taylor rule (“STR+NoN”). Collectively, these results suggest that the forward-looking interest rate term is at best economically unimportant.

Panel B of Table 2 reports the remainder of the structural parameters in these four specifications. We find that the estimated parameters take values consistent with previous estimations of similar models, such as Dennis (2009) and Milani and Treadwell (2012). One possible exception is the high estimate of θp, which exceeds the values reported in Smets and Wouters (2007), among a large number of others.[11] However, depending on the specific sample, model, or estimation technique, similar results have been obtained earlier as well; see Rabanal and Rubio-Ramirez (2005), Cho and Moreno (2006), or Boivin and Giannoni (2006). While the elevated estimate of θp is in line with these studies, there are two potential reasons for its being towards the high end of all available estimates in the literature. First, our sample includes the Great Recession, which is likely to increase the estimated degree of price stickiness; see Hirose and Inoue (2015) for an illustration. Second, the introduction of news shocks typically leads to a substantial increase in the value of this parameter, as documented by Milani and Treadwell (2012), Milani and Rajbhandari (2012), or Hirose and Kurozumi (2012). Therefore, this parameter is expected to be considerably higher than in DSGE models that do not feature news shocks or whose samples do not include the zero-interest-rate environment.

Table 3 imposes alternative news shock structures on the model, with each specification having a positive value of ξ. The column labeled “FTR+SRN” imposes the short-run identification on the structure of news shocks allowing their anticipation horizons to vary between 1 and 4 quarters. The standard deviations of demand and supply news shocks at the 4-quarter horizon are particularly large and are about the same in magnitude as their surprise counterparts. The standard deviation of the anticipated monetary shock at the 2-quarter horizon is larger than its surprise counterpart, while the estimated value of ξ plummets to 0.257. The column labeled “FTR+LRN” reports the results for the specification with the long-run identification of all three types of news shocks. Monetary and demand news shocks at the 4-quarter anticipation horizon and supply news shock at the 12-quarter anticipation horizon are almost as large or larger than their surprise counterparts. The estimated value of ξ falls further to 0.185. We note, however, the marginal likelihoods of the specifications that feature all three types of news shocks remain below the baseline “FTR+MN” specification. The last two columns in Table 3 summarize estimation results from specifications where the news component features only in the demand shock (“FTR+DN”) or the supply shock (“FTR+SN”). These specifications produce relatively high estimates of ξ that are well in line with the previous literature. However, their marginal likelihoods are much lower than in the FTR+MN specification, the mean estimates of the news components’ standard deviations are smaller than their surprise counterparts, and the lower bounds of the posterior probability intervals are close to zero. Therefore, these checks confirm our main finding that the model with monetary news and low, economically insignificant ξ best fits the data.

Parameter estimate posteriors: long-run news.

| Parameters | STR+MN | FTR+LRN | FTR+DN | FTR+SN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | PPI | Mean | PPI | Mean | PPI | Mean | PPI | |

| b | 0.568 | [0.434, 0.746] | 0.794 | [0.726, 0.858] | 0.789 | [0.705, 0.859] | 0.743 | [0.640, 0.833] |

| θp | 0.950 | [0.936, 0.964] | 0.946 | [0.931, 0.960] | 0.930 | [0.911, 0.947] | 0.939 | [0.924, 0.952] |

| ωp | 0.916 | [0.805, 0.988] | 0.037 | [0.011, 0.075] | 0.062 | [0.018, 0.130] | 0.213 | [0.081, 0.398] |

| ρ | 0.855 | [0.834, 0.874] | 0.900 | [0.863, 0.928] | 0.857 | [0.803, 0.902] | 0.803 | [0.674, 0.875] |

| γp | 1.890 | [1.536, 2.248] | 1.582 | [1.206, 1.934] | 1.766 | [1.388, 2.194] | 1.701 | [1.281, 2.131] |

| γy | 0.342 | [0.232, 0.471] | 0.512 | [0.355, 0.707] | 0.443 | [0.273, 0.685] | 0.455 | [0.284, 0.652] |

| ρr | 0.317 | [0.298, 0.344] | 0.163 | [0.034, 0.321] | 0.260 | [0.136, 0.405] | 0.360 | [0.184, 0.585] |

| ρy | 0.822 | [0.680, 0.911] | 0.138 | [0.018, 0.265] | 0.265 | [0.054, 0.520] | 0.656 | [0.525, 0.771] |

| ρp | 0.076 | [0.025, 0.153] | 0.930 | [0.871, 0.961] | 0.829 | [0.747, 0.899] | 0.068 | [0.008, 0.183] |

| ξ | 0.185 | [0.066, 0.321] | 0.601 | [0.400, 0.770] | 0.724 | [0.453, 0.853] | ||

| σr | 0.155 | [0.115, 0.206] | 0.038 | [0.001, 0.084] | 0.126 | [0.104, 0.154] | 0.107 | [0.081, 0.141] |

| σy | 0.178 | [0.131, 0.241] | 0.352 | [0.302, 0.413] | 0.336 | [0.274, 0.398] | 0.237 | [0.183, 0.297] |

| σp | 0.178 | [0.160, 0.198] | 0.007 | [0.004, 0.009] | 0.061 | [0.041, 0.087] | 0.187 | [0.162, 0.213] |

| σy4 | 0.275 | [0.233, 0.334] | 0.124 | [0.001, 0.324] | ||||

| σp4 | 0.024 | [0.023, 0.026] | 0.015 | [0.000, 0.060] | ||||

| σr4 | 0.028 | [0.000, 0.091] | 0.087 | [0.001, 0.180] | ||||

| σy8 | 0.025 | [0.002, 0.034] | 0.090 | [0.000, 0.245] | ||||

| σp8 | 0.003 | [0.000, 0.016] | 0.024 | [0.000, 0.088] | ||||

| σr8 | 0.172 | [0.094, 0.219] | 0.014 | [0.000, 0.052] | ||||

| σy12 | 0.000 | [0.000, 0.001] | 0.125 | [0.001, 0.257] | ||||

| σp12 | 0.015 | [0.000, 0.050] | 0.088 | [0.054, 0.128] | ||||

| σr12 | 0.031 | [0.000, 0.117] | 0.008 | [0.000, 0.024] | ||||

| Marginal L | –400.61 | –390.22 | –381.15 | –354.56 | ||||

4.2 Empirical impulse responses

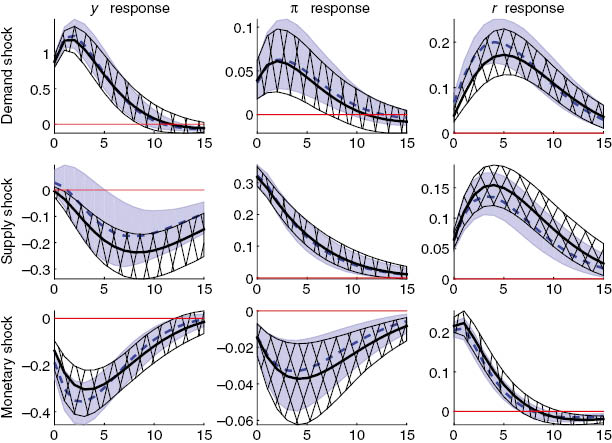

We next compare impulse response functions (IRFs) in models where ξ≥0 (dashed mean IRF, filled 95% confidence interval) and models where it is set to zero (solid mean IRF, cross-hatched 95% confidence interval). Figure 4 compares models designated “FTR+NoN” and “STR+NoN” for the parameter values presented in Table 2 to assess the impact of this term in models without news shocks. Sets of IRF confidence intervals from both models overlap closely for all shocks and response variables, as mean responses from one model are well within the confidence intervals from the other model. One possible exception is the output gap response to the supply shock where the mean response from “FTR+NoN” follows the upper branch of the confidence interval for “STR+NoN.” But this seems to be primarily driven by the fact that the confidence interval for the former model is considerably wider than for the latter.

Impulse responses for models without news shocks: blue dashed line with shaded 95% confidence interval – model with ξ>0; solid black line with cross-hatched 95% confidence intervals – model with ξ=0.

We repeat this exercise in the models that feature monetary news shocks, “FTR+MN” and “STR+MN”, with parameter values again taken from Table 2. Figure 5 reveals a large overlap between the two sets of confidence intervals. Again, in one case, the output gap response to the demand surprise shock, the mean response from the “FTR+MN” model appears to closely match the upper branch of the confidence interval from the “STR+MN” model, but in all other cases, mean IRFs are very close to each other. To economize on space, we show the IRFs to the monetary news shock only at horizon h=8.[12] Recall that Table 2 suggests that monetary news has the largest economic significance at this horizon. Again, confidence intervals from models with and without the forward-looking interest rate term overlap quite closely, although in this case, the former specification delivers wider confidence intervals. We, therefore, conclude that the presence of the forward-looking interest rate term in the Taylor rule does not have important implications for the dynamic transmission of stochastic shocks in the class of models employed in this paper.

Impulse responses for models with news shocks: blue dashed line with shaded 95% confidence interval – model with ξ>0; solid black line with cross-hatched 95% confidence intervals – model with ξ=0.

5 Robustness checks

We next explore several possibilities, accounting for which, in principle, may affect our results. These concern our choice of the sample that includes the zero-interest-rate environment during the most recent recession and the specific modeling choice with respect to the Fed’s forward-looking behavior. The choice of the sample is simply driven by including the most recent data; we show that excluding the Great Recession from our sample does not qualitatively affect our results. The modeling choice is driven by parsimony; alternative strategies for modeling the Fed’s forward-looking behavior also do not change our conclusions.

5.1 Zero lower bound on the nominal interest rate

Since our sample includes the Great Recession, it is important to address the possible impact of the zero lower bound (ZLB) on the nominal interest rate on the structural parameter estimates. On one had, Fernandez-Villaverde et al. (2012), Gali (2011), and Gali, Smets, and Wouters (2011) argue that the presence of the ZLB may introduce bias into the estimation procedure of a DSGE model. On the other, Hirose and Inoue (2015) provide evidence from a simulation experiment in the context of a model very similar to ours that shows that it is unlikely that the ZLB will bias estimated parameters or affect the shape of impulse response functions. Without taking a stance in this important debate, we re-estimate the specifications in Tables 2 and 3 using the data from the 1960Q1–2007Q4 subsample. We find that our results hold without major changes to our conclusions and, if anything, bolster the case against the economic significance of the forward-looking term in the Taylor rule specification. To economize on space, Table 4 reports the estimated value of ξ and the marginal likelihoods for all eight specifications. All other parameter estimates are very close to the values reported in Tables 2 and 3. The majority of the estimated values of ξ are slightly lower than in their full-sample counterparts and, of all eight specifications, the marginal likelihood is the highest in cases where ξ is set to 0. Models where the estimates of ξ are the highest and in line with previously reported results (“FTR+SN” and “FTR+DN”) continue to have the lowest marginal likelihoods.

Marginal Likelihood and ξ Estimate Posteriors: 1960Q1–2007Q4.

| STR+NoN | FTR+NoN | FTR+SRN | FTR+LN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ξ (Mean, [PPI]) | 0.55 | [0.28, 0.76] | 0.35 | [0.17, 0.54] | 0.27 | [0.09, 0.529] | |

| Marginal L | –281.4 | –285.0 | –292.9 | –287.5 | |||

| STR+MN | FTR+MN | FTR+DN | FTR+SN | ||||

| ξ (Mean, [PPI]) | 0.23 | [0.08, 0.43] | 0.44 | [0.17, 0.70] | 0.66 | [0.49, 0.80] | |

| Marginal L | –276.4 | –287.5 | –300.95 | –296.3 | |||

5.2 Alternative specifications of the Fed’s forward-looking behavior

While the Calvo-type Taylor rule (3) provides a parsimonious summary of the central bank’s responding to forecasts of the future macroeconomic activity, that parsimony comes at a cost in terms of imposing assumptions on the nature of forecast horizons, the weights on which decline geometrically. It may be possible that in practice, the Fed uses a specification closer to the one where the nominal interest rate responds to the future values of output gap and inflation at a particular horizon, as in the specification of Clarida, Galí, and Gertler (2000).

The general specification takes the following form:

This equation nests several special cases:

ξ=0, α=0: standard Taylor rule (STR);

ξ>0, α=0: Calvo-type forward-looking rule (FTR);

ξ=0, α>0: non-Calvo-type forward-looking rule of Orphanides and Wieland (2008);[13]

ξ>0, α>0: generalized forward-looking rule (GFR).

To understand the effect of introducing monetary news shocks on the estimated Taylor rule, we first estimate the most general specification, treating ξ and α as estimated parameters. Our prior for α is quite diffuse, given by the beta distribution with a mean of 0.7 and the standard deviation of 0.2. We conduct our estimation exercise using two values for the leads of output gap and inflation targets: k=1, 4. While the setting with k=1 is standard benchmark, e.g. Clarida, Galí, and Gertler (2000) or Mavroeidis (2010), many authors have argued that the Fed’s target horizon stretches farther out, at about one year; Orphanides (2003) and Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy (2011) provide such evidence for the Fed’s policy conduct in the United States. The presence of a weight on current and future inflation is also similar to the averaging of future target values at different horizons, as in Campbell et al. (2012), without imposing equal weights due to averaging.

Panel A of Table 5 presents estimates of (9) with “NoN” designating models with no news shocks, “LRMN” designating the long-run structure of monetary news shocks, and k describing the leads for inflation and output gap targets in the rule. Our main result holds: the introduction of monetary news shocks leads to a fall in the estimated value of ξ in half towards the values from the baseline specification. Similarly, the estimated value of α that describes the weight placed on the future values of inflation and output gap falls with the introduction of monetary news and is indistinguishable from 0 in the “LRMN, k=4” case.

Summary of the estimates of the generalized forward-looking rule, (9).

| NoN, k=1 | NoN, k=4 | LRMN, k=1 | LRMN, k=4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: GFR | ||||||||

| α (Mean, [PPI]) | 0.65 | [0.07, 0.99] | 0.43 | [0.03, 0.91] | 0.39 | [0.01, 0.96] | 0.07 | [0.00, 0.27] |

| ξ (Mean, [PPI]) | 0.53 | [0.22, 0.77] | 0.47 | [0.14, 0.74] | 0.25 | [0.09, 0.55] | 0.25 | [0.10, 0.41] |

| Marginal L | –356.2 | –356.1 | –345.4 | –348.2 | ||||

| Panel B: GFR, α=1 | ||||||||

| ξ (Mean,[PPI]) | 0.49 | [0.22, 0.73] | 0.34 | [0.10, 0.62] | 0.23 | [0.09, 0.39] | 0.20 | [0.07, 0.34] |

| Marginal L | –355.4 | –359.3 | –349.7 | –342.0 | ||||

Since our baseline results correspond to the case of α=0 and its value is not well identified in most specifications, we also explore the possibility of restricting the value of α to 1. Panel B of Table 5 has the corresponding set of estimates. Again, the introduction of monetary news shocks leads to a pronounced decline in the estimated values of ξ to levels consistent with our baseline results. We, therefore, conclude that our robustness checks confirm the quantitative unimportance of the forward-looking interest rate term in the Calvo-type Taylor rule.

6 Conclusion

This paper makes a contribution towards understanding the interplay between anticipated future shocks and the design of Taylor rules. We have employed Bayesian estimation methods to investigate whether the interest rate response to future macroeconomic fluctuations, as modeled by a forward-looking interest rate term in the Taylor rule, is economically important, as the recent literature on this subject has claimed. We find that once news shocks are introduced into the standard small-scale model of the US economy, this term loses its economic importance and the model fit with the data improves. This finding is robust across a large number of model modifications that we have explored above. We, therefore, conclude that announcements about the future conduct of policy described by monetary news shocks are an important feature of the conduct of monetary policy in the US, whereas forecast-targeting, as modeled by the Calvo-type Taylor rule, is not.

References

An, Sungbae, and Frank Schorfheide. 2007. “Bayesian Analysis of DSGE Models.” Econometric Reviews 26: 113–172.10.21799/frbp.wp.2006.05Search in Google Scholar

Bache, Ida, Oistein Roisland, and Kjersti Torsten. 2011. “Interest Rate Smoothing and ‘Calvo-type’ Interest Rate Rules: A Comment on Levine, McAdam, and Pearlman (2007).” International Journal of Central Banking 7: 79–90.Search in Google Scholar

Barsky, Robert, and Eric Sims. 2011. “News Shocks and Business Cycles.” Journal of Monetary Economics 58: 273–289.10.1016/j.jmoneco.2011.03.001Search in Google Scholar

Batini, Nicoletta, and Andrew Haldane. 1999. “Forward-looking Rules for Monetary Policy.” In Monetary Policy Rules, edited by John Taylor, 157–202. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press.10.2139/ssrn.147549Search in Google Scholar

Batini, Nicoletta, Alejandro Justiniano, Paul Levine, and Joseph Pearlman. 2006. “Robust Inflation-forecast-based Rules to Shield against Indeterminacy.” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 30: 1491–1526.10.1016/j.jedc.2005.08.010Search in Google Scholar

Beaudry, Paul, and Franck Portier. 2006. “Stock Prices, News, and Economic Fluctuations.” American Economic Review 96: 1293–1307.10.3386/w10548Search in Google Scholar

Boivin, Jean, and Marc Giannoni. 2006. “Has Monetary Policy Become More Effective?” Review of Economics and Statistics 88: 445–462.10.3386/w9459Search in Google Scholar

Calvo, Guillermo. 1983. “Staggered Prices in a Utility Maximizing Framework.” Journal of Monetary Economics 52: 383–398.10.7551/mitpress/4758.003.0007Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Jeffrey, Charles Evans, Jonas Fisher, and Alejandro Justiniano. 2012. “Macroeconomic Effects of FOMC Forward Guidance.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring.10.1353/eca.2012.0004Search in Google Scholar

Chib, Siddhartha, and Edward Greenberg. 1995. “Understanding the Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm.” The American Statistician 49: 327–335.Search in Google Scholar

Cho, Seonghoon, and Antonio Moreno. 2006. “A Small-Sample Study of the New-Keynesian Macro Model.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 38: 1461–1481.10.1353/mcb.2006.0078Search in Google Scholar

Clarida, Richard, Jordi Galí, and Mark Gertler. 2000. “Monetary Policy Rules and Macroeconomic Stability: Evidence and Some Theory.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 115: 147–179.10.3386/w6442Search in Google Scholar

Del Negro, Marco, Marc Giannoni, and Christina Patterson. 2013. “The Forward Guidance Puzzle.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report No. 574.10.2139/ssrn.2163750Search in Google Scholar

Dennis, Richard. 2009. “Consumption-Habits in a New Keynesian Business Cycle Model.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 41: 1015–1030.10.1111/j.1538-4616.2009.00242.xSearch in Google Scholar

Eggertsson, Gauti, and Michael Woodford. 2003. “The Zero Bound on Interest Rates and Optimal Monetary Policy.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 34: 139–211.10.1353/eca.2003.0010Search in Google Scholar

English, William, William Nelson, and Brian Sack. 2003. “Interpreting the Significance of the Lagged Interest Rate in Estimated Monetary Policy Rules.” Contributions to Macroeconomics 3, article 5.10.2202/1534-6005.1073Search in Google Scholar

Fernandez-Villaverde, Jesus, Grey Gordon, Pablo A. Guerron-Quintana, and Juan Rubio-Ramrez. 2012. “Nonlinear Adventures at the Zero Lower Bound.” NBER Working Paper No. 18058.10.21799/frbp.wp.2012.10Search in Google Scholar

Francis, Neville, Michael Owyang, Jennifer Roush, and Riccardo DiCecio. 2005. “A Flexible Finite-horizon Alternative to Long-run Restrictions with an Application to Technology Shock.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper.Search in Google Scholar

Gabriel, Vasco, Paul Levine, and Christopher Spencer. 2009. “How Forward-looking is the Fed? Direct Estimates from a ‘Calvo-type’ Rule.” Economics Letters 104: 92–95.10.1016/j.econlet.2009.04.018Search in Google Scholar

Gali, Jordi. 2011. “The Return of the Wage Phillips Curve.” Journal of the European Economic Association 9: 436–461.10.3386/w15758Search in Google Scholar

Gali, Jordi, Frank Smets, and Raf Wouters. 2011. “Unemployment in an Estimated New Keynesian Model.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 329–360. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press.10.1086/663994Search in Google Scholar

Gavin, William, Benjamin Keen, Alexander Richter, and Nathaniel Throckmorton. 2014. “The Limitations of Forward Guidance.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2013-038C.Search in Google Scholar

Gerlach-Kristen, Petra. 2004. “Interest-Rate Smoothing: Monetary Policy Inertia or Unobserved Variables?” The B. E. Journal of Macroeconomics (Contributions) 4: article 3.10.2202/1534-6005.1169Search in Google Scholar

Gilchrist, Simon, and John Leahy. 2002. “Monetary Policy and Asset Prices.” Journal of Monetary Economics 49: 75–97.10.1016/S0304-3932(01)00093-9Search in Google Scholar

Gurkaynak, Refet, Brian Sack, and Eric Swanson. 2005. “Do Actions Speak Louder Than Words? The Response of Asset Prices to Monetary Policy Actions and Statements.” International Journal of Central Banking 1: 55–93.Search in Google Scholar

Hirose, Yasuo, and Atsushi Inoue. 2015. “Zero Lower Bound and Parameter Bias in an Estimated DSGE Model.” Journal of Applied Econometrics, forthcoming.10.1002/jae.2447Search in Google Scholar

Hirose, Yasuo, and Takushi Kurozumi. 2012. “Do Investment-specific Technological Changes Matter for Business Fluctuations? Evidence from Japan.” Pacific Economic Review 17: 208–230.10.1111/j.1468-0106.2012.00580.xSearch in Google Scholar

Jeffreys, Harold. 1961. The Theory of Probability. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kapinos, Pavel. 2011. “Forward-looking Monetary Policy and Anticipated Shocks to Inflation.” Journal of Macroeconomics 33: 620–633.10.1016/j.jmacro.2011.05.002Search in Google Scholar

Khan, Hashmat, and John Tsoukalas. 2012. “The Quantitative Importance of News Shocks in Estimated DSGE Models.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 44: 1535–1561.10.1111/j.1538-4616.2012.00543.xSearch in Google Scholar

Kuttner, Kenneth. 2001. “Monetary Policy Surprises and Interest Rates: Evidence from the Fed Funds Futures Market.” Journal of Monetary Economics 47: 523–544.10.1016/S0304-3932(01)00055-1Search in Google Scholar

Levin, Anrew, David Lopez-Salido, Edward Nelson, Tack Yun. 2010. “Limitations on the Effectiveness of Forward Guidance at the Zero Lower Bound.” International Journal of Central Banking 6: 143–189.Search in Google Scholar

Levine, Paul, Peter McAdam, and Joseph Pearlman. 2007. “Inflation-Forecast-Based Rules and Indeterminacy: A Puzzle and a Resolution.” International Journal of Central Banking 3: 77–110.10.2139/ssrn.907311Search in Google Scholar

Mavroeidis, Sophocles. 2010. “Monetary Policy Rules and Macroeconomic Stability: Some New Evidence.” American Economic Review 100 (1): 491–503.10.1257/aer.100.1.491Search in Google Scholar

Milani, Fabio, and John Treadwell. 2012. “The Effects of Monetary Policy ‘News’ and ‘Surprises.”’ Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 44: 1667–1692.10.1111/j.1538-4616.2012.00549.xSearch in Google Scholar

Milani, Fabio, and Ashish Rajbhandari. 2012. “Expectation Formation and Monetary DSGE Models: Beyond the Rational Expectations Paradigm.” Advances in Econometrics 28: 253–288.10.1108/S0731-9053(2012)0000028009Search in Google Scholar

Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy, Alex. 2011. “Monetary Policy Estimation in Real Time: Forward-Looking Taylor Rule without Foward-Looking Data.” Journal of Money, Banking, and Credit 43: 871–897.10.1111/j.1538-4616.2011.00400.xSearch in Google Scholar

Orphanides, Athanasios. 2003. “Historical Monetary Policy Ananlysis and the Taylor Rule.” Journal of Monetary Economics 50: 983–1022.10.1016/S0304-3932(03)00065-5Search in Google Scholar

Orphanides, Athanasios, and Volker Wieland. 2008. “Economic Projections and Rules of Thumb for Monetary Policy.” Federal Reserve Bank of St’ Louis Review 90 (4): 307–324.10.20955/r.90.307-324Search in Google Scholar

Rabanal, Pau, and Juan Rubio-Ramírez. 2005. “Comparing New Keynesian Models of the Business Cycle: A Bayesian Approach.” Journal of Monetary Economics 52: 1151–1166.10.1016/j.jmoneco.2005.08.008Search in Google Scholar

Rudebusch, Glenn. 2002. “Term Structure Evidence on Interest Rate Smoothing and Monetary Policy Inertia.” Journal of Monetary Economics 49: 1161–1187.10.1016/S0304-3932(02)00149-6Search in Google Scholar

Rudebusch, Glenn. 2006. “Monetary Policy Inertia: Fact or Fiction?” International Journal of Central Banking 2: 85–135.10.2139/ssrn.864484Search in Google Scholar

Schmitt-Grohe, Stephanie, and Martin Uribe. 2012. “What’s News in Business Cycles.” Econometrica 80: 2733–2764.10.3386/w14215Search in Google Scholar

Schorfheide, Frank. 2008. “DSGE Model-based Estimation of the New Keynesian Phillips Curve.” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly 94: 397–433.Search in Google Scholar

Sims, Christopher. 2002. “Solving Linear Rational Expectations Models.” Computational Economics 20: 1–20.10.1023/A:1020517101123Search in Google Scholar

Smets, Frank, and Rafael Wouters. 2007. “Shocks and Frictions in US Business Cycles: A Bayesian DSGE Approach.” American Economic Review 97: 586–606.10.1257/aer.97.3.586Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, John. 1993. “Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 39: 195–214.10.1016/0167-2231(93)90009-LSearch in Google Scholar

©2016 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Advances

- Sustainable monetary policy and inflation expectations

- Contributions

- Monetary policy and news shocks: are Taylor rules forward-looking?

- How do firms adjust production factors to the cycle?

- Does fiscal policy affect interest rates? Evidence from a factor-augmented panel

- Advances

- Public provision of health insurance and welfare

- Contributions

- Reallocation effects of recessions and financial crises: an industry-level analysis

- Growth and non-regular employment

- Knowledge licensing in a model of R&D-driven endogenous growth

- The Taylor principle is valid under wage stickiness

- Testing monetary policy optimality using volatility outcomes: a novel approach

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Advances

- Sustainable monetary policy and inflation expectations

- Contributions

- Monetary policy and news shocks: are Taylor rules forward-looking?

- How do firms adjust production factors to the cycle?

- Does fiscal policy affect interest rates? Evidence from a factor-augmented panel

- Advances

- Public provision of health insurance and welfare

- Contributions

- Reallocation effects of recessions and financial crises: an industry-level analysis

- Growth and non-regular employment

- Knowledge licensing in a model of R&D-driven endogenous growth

- The Taylor principle is valid under wage stickiness

- Testing monetary policy optimality using volatility outcomes: a novel approach