Abstract

This paper provides the first causal evidence of the effect of a change in divorce laws on noncognitive skills in adulthood. We exploit state-cohort variation in the adoption of unilateral divorce laws in the U.S. to assess whether children exposed to this law have different noncognitive skills in adulthood compared to those never exposed or exposed as adults. Using data from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the U.S. (MIDUS) and employing the staggered difference-in-differences identification strategy developed by Callaway and Sant’Anna, we show that divorce reform had a detrimental long-term effect on the conscientiousness of those who were exposed as children whether their parents divorced or not. Changes in parental inputs can explain most of the effect, which is greatest for men whose parents divorced.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Pedro Sant’Anna and Fernando Rios-Avila for helping us implement their estimator, and to Daniel Hamermesh, Justin Wolfers, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. This study uses the restricted data available from the Institute on Aging at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Timeline of unilateral divorce laws in the United States.

| State | Date | State | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 1971 | Montana | 1973 |

| Alaska | 1935 | Nebraska | 1972 |

| Arizona | 1973 | Nevada | 1967 |

| Arkansas | New Hampshire | 1971 | |

| California | 1970 | New Jersey | |

| Colorado | 1972 | New Mexico | 1933 |

| Connecticut | 1973 | New York | |

| Delaware | 1968 | North Carolina | |

| Florida | 1971 | North Dakota | 1971 |

| Georgia | 1973 | Ohio | |

| Hawaii | 1972 | Oklahoma | 1953 |

| Idaho | 1971 | Oregon | 1971 |

| Illinois | Pennsylvania | ||

| Indiana | 1973 | Rhode Island | 1975 |

| Iowa | 1970 | South Carolina | |

| Kansas | 1969 | South Dakota | 1985 |

| Kentucky | 1972 | Tennessee | |

| Louisiana | Texas | 1970 | |

| Maine | 1973 | Utah | 1987 |

| Maryland | Vermont | ||

| Massachusetts | 1975 | Virginia | |

| Michigan | 1972 | Washington | 1973 |

| Minnesota | 1974 | West Virginia | |

| Mississippi | Wisconsin | 1978 | |

| Missouri | Wyoming | 1977 |

-

Source: Gruber (2004).

Factor loadings for conscientiousness.

| Factor 1 | |

|---|---|

| Organized | 0.5223 |

| Responsible | 0.6238 |

| Hardworking | 0.5107 |

| Careless (reverse-coded) | 0.3617 |

-

We retain factor 1 because this factor has an eigenvalue over one. We chose the personality traits organized, responsible, hardworking, and careless following the survey methodology. As shown in the table, being responsible has the highest weight, followed by being organized and being hardworking. Because noncognitive skills evolve in adulthood, we use an age-adjusted measure derived by regressing conscientiousness on the second-order age polynomial and its interactions with gender for the control group before our study period, 1938–1960, and then using the predicted residuals to detrend, standardize, and center this measure. The resulting variable has a mean of zero and a variance of one.

Factor loadings for parental inputs.

| Factor 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Affection | ||

| Paternal affection | Maternal affection | |

| How would you rate your relationship with your father/mother during the years you were growing up? | 0.8540 | 0.7895 |

| How much did he/she understand your problems and worries? | 0.8566 | 0.8225 |

| How much could you confide in him/her about things that were bothering you? | 0.8129 | 0.7828 |

| How much love and affection did he/she give you? | 0.8427 | 0.8155 |

| How much time and attention did he/she give you when you needed it? | 0.8962 | 0.8464 |

| How much effort did he/she put into watching over you and making sure you had a good upbringing? | 0.7622 | 0.6743 |

| How much did he/she teach you about life? | 0.7625 | 0.6634 |

(continued)

| Factor 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Panel B: Discipline | ||

| Paternal discipline | Maternal discipline | |

| How strict was he/she with his rules for you? | 0.9590 | 0.9290 |

| How consistent was he/she about the rules? | 0.7532 | 0.6904 |

| How harsh was he/she when he punished you? | 0.6589 | 0.5455 |

| How much did he/she stop you from doing things that other kids your age were allowed to do? | 0.5838 | 0.5269 |

-

We retain factor 1 for each variable because this factor has an eigenvalue over one. To construct these variables, we follow the survey methodology, according to which paternal/maternal affection combines seven variables listed in Panel A and paternal/maternal discipline combines four measures listed in Panel B. As shown in the table, parental love and affection as well as a parental understanding of child’s problems have the highest weights in both paternal and maternal affection; and parental strictness with the rules is most likely to define parental discipline.

The effects of unilateral divorce laws on conscientiousness, using conventional difference-in-differences methodology.

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Unilateral divorce law | −0.121*** | −0.112*** |

| (0.033) | (0.020) | |

| Observations | 8238 | 8658 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.133 | −0.127 |

-

The estimated coefficients on the policy variable unilateral divorce law are obtained using the standard difference-in-differences methodology and interpreted as a standard-deviation change in conscientiousness. The models include year and group fixed effects as well as age dummies and an indicator for having same-sex siblings. Standard errors clustered at the state level are shown in parentheses. ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1.

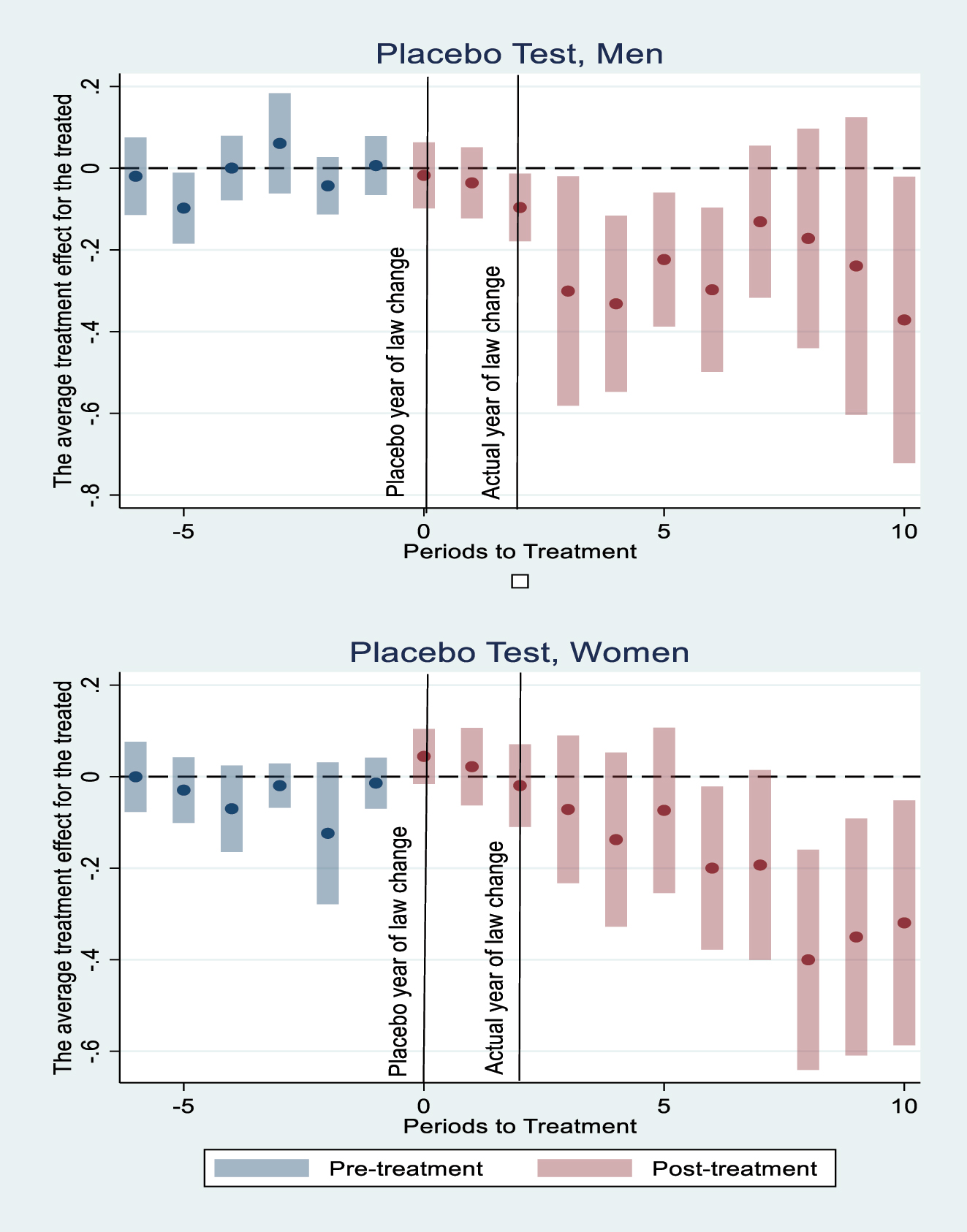

Placebo tests reassigning t −2 as treatment time. See Figure 1 for the specification.

References

Akee, R., W. Copeland, E. J. Costello, and E. Simeonova. 2018. “How Does Household Income Affect Child Personality Traits and Behaviors?” The American Economic Review 108 (3): 775–827. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20160133.Search in Google Scholar

Amato, P. R. 2005. “The Impact of Family Formation Change on the Cognitive, Social, and Emotional Well-Being of the Next Generation.” The Future of Children 15 (2): 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2005.0012.Search in Google Scholar

Angelini, V., M. Bertoni, L. Stella, and C. T. Weiss. 2019. “The Ant or the Grasshopper? the Long-Term Consequences of Unilateral Divorce Laws on Savings of European Households.” European Economic Review 119: 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2019.07.002.Search in Google Scholar

Bertrand, M., and R. Pan. 2013. “The Trouble with Boys: Social Influences and the Gender Gap in Disruptive Behavior.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5 (1): 32–64. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.5.1.32.Search in Google Scholar

Borusyak, K., X. Jaravel, and J. Spiess. 2023. Revisiting Event Study Designs: Robust and Efficient Estimation. Working Paper.10.1093/restud/rdae007Search in Google Scholar

Callaway, B., and P. H. C. Sant’Anna. 2021. “Difference-in-differences with Multiple Time Periods.” Journal of Econometrics 225: 200–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001.Search in Google Scholar

Cheadle, J. E., P. A. Amato, and V. King. 2010. “Patterns of Nonresident Father Contact.” Demography 47 (1): 205–25. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0084.Search in Google Scholar

Cunha, F., and J. Heckman. 2007. “The Technology of Skill Formation.” AER Papers and Proceedings 97 (2): 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.2.31.Search in Google Scholar

Del Boca, D., C. Flinn, and M. Wiswall. 2014. “Household Choices and Child Development.” The Review of Economic Studies 81 (1): 137–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdt026.Search in Google Scholar

Eisenberg, N., A. L. Duckworth, T. L. Spinrad, and C. Valiente. 2014. “Conscientiousness: Origins in Childhood?” Developmental Psychology 50 (5): 1331–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030977.Search in Google Scholar

Elkins, R., and S. Schurer. 2020. “Exploring the Role of Parental Engagement in Non-cognitive Skill Development over the Lifecourse.” Journal of Population Economics 33: 957–1004. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00767-5.Search in Google Scholar

Fletcher, J. M., and S. Schurer. 2017. “Origins of Adulthood Personality: The Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences.” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 17 (2): 20150212, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2911476.Search in Google Scholar

Gendek, K. R., W. A. Stock, and C. Stoddard. 2007. “No-Fault Divorce Laws and the Labor Supply of Women with and Without Children.” Journal of Human Resources 42 (1): 247–74.10.3368/jhr.XLII.1.247Search in Google Scholar

Gill, A., and K. J. Kleinjans. 2020. “The Effect of the Fall of the Berlin Wall on Children’s Noncognitive Skills.” Applied Economics 52 (51): 5595–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2020.1770189.Search in Google Scholar

Goldin, C. 2006. “The Quiet Revolution that Transformed Women’s Employment, Education, and Family.” AEA Papers and Proceedings 96 (2): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282806777212350.Search in Google Scholar

Gruber, J. 2004. “Is Making Divorce Easier Bad for Children? the Long Run Implications of Unilateral Divorce.” Journal of Labor Economics 22 (4): 799–833. https://doi.org/10.1086/423155.Search in Google Scholar

Hamermesh, D. S. 2022. “Mom’s Time – Married or Not.” In Mothers in the Labor Market, edited by J. A. Molina, 1–27. Springer. (Chapter 1).10.1007/978-3-030-99780-9_1Search in Google Scholar

Hayduk, I., and M. Toussaint-Comeau. 2022. “Determinants of Noncognitive Skills: Mediating Effects of Siblings’ Interaction and Parenting Quality.” Contemporary Economic Policy 40 (4): 677–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12572.Search in Google Scholar

Hoehn-Velasco, L., and A. Silveria-Murillo. 2020. “Do Spouses Negotiate in the Shadow of the Law? Evidence from Unilateral Divorce, Suicides, and Homicides in Mexico.” Economics Letters 187: 1–4.10.1016/j.econlet.2019.108891Search in Google Scholar

Judge, T. A., C. J. Thoresen, and M. R. Barrick. 1999. “The Big Five Personality Traits, General Mental Ability, and Career Success across the Life Span.” Personnel Psychology 52 (3): 621–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00174.x.Search in Google Scholar

Kneip, T., G. Bauer, and S. Reinhold. 2014. “The Direct and Indirect Effects of Unilateral Divorce Law on Marital Stability.” Demography 15: 2103–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0337-2.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, J. Y., and G. Solon. 2011. “The Fragility of Estimated Effects of Unilateral Laws on Divorce Rates.” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 11 (1): 1.10.2202/1935-1682.2994Search in Google Scholar

Lei, Z., and S. Lundberg. 2020. “Vulnerable Boys: Short-Term and Long-Term Gender Differences in the Impacts of Adolescent Disadvantage.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 178: 424–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2020.07.020.Search in Google Scholar

Lindqvist, E., and R. Vestman. 2011. “The Labor Market Returns to Cognitive and Noncognitive Ability: Evidence from the Swedish Enlistment.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3 (1): 101–28. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.3.1.101.Search in Google Scholar

McLanahan, S., L. Tach, and D. Schneider. 2013. “The Causal Effects of Father Absence.” Annual Review of Sociology 39: 399–427. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145704.Search in Google Scholar

Mike, A., K. Harris, B. W. Roberts, and J. J. Jackson. 2015. Conscientiousness. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed., Vol. 4, 658–65. Elsevier.10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.25047-2Search in Google Scholar

Peter, F. H., and C. K. Spiess. 2016. “Family Instability and Locus of Control in Adolescence.” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 16 (3): 1439–71. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2015-0175.Search in Google Scholar

Reinhold, S., T. Kneip, and G. Bauer. 2013. “The Long Run Consequences of Unilateral Divorce Laws on Children – Evidence from SHARELIFE.” Journal of Population Economics 26: 1035–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0435-7.Search in Google Scholar

Rios-Avila, F., P. Sant’Anna, and B. Callaway. 2022. CSDID: Stata Module for the Estimation of Difference-In-Difference Models with Multiple Periods. Boston College Department of Economics Working Paper 2022/4/16.Search in Google Scholar

Roberts, B., J. J. Jackson, A. L. Duckworth, and K. Von Culin. 2011. “Personality Measurement and Assessment in Large Panel Surveys.” Forum for Health Economics & Policy 14 (2): 0000102202155895441268, https://doi.org/10.2202/1558-9544.1268.Search in Google Scholar

Sant’Anna, P., and J. Zhao. 2020. “Doubly Robust Difference-In-Differences Estimators.” Journal of Econometrics 219 (1): 101–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.06.003.Search in Google Scholar

Stevenson, B. 2007. “The Impact of Divorce Laws on Marriage-specific Capital.” Journal of Labor Economics 25 (1): 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1086/508732.Search in Google Scholar

Stevenson, B., and J. Wolfers. 2006. “Bargaining in the Shadow of the Law: Divorce Laws and Family Distress.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 121 (1): 267–88. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2006.121.1.267.Search in Google Scholar

Stevenson, B., and J. Wolfers. 2007. “Marriage and Divorce: Changes and the Driving Forces.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 21 (2): 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.21.2.27.Search in Google Scholar

Sun, L., and S. Abraham. 2021. “Estimating Dynamic Treatment Effects in Event Studies with Heterogenous Treatment Effects.” Journal of Econometrics 225 (2): 175–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.09.006.Search in Google Scholar

Tackman, A. M., S. Srivastava, J. H. Pfeifer, and M. Dapretto. 2017. “Development of Conscientiousness in Childhood and Adolescence: Typical Trajectories and Associations with Academic, Health, and Relationship Changes.” Journal of Research in Personality 67: 85–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.05.002.Search in Google Scholar

Voena, A. 2015. “Yours, Mine, and Ours: Do Divorce Laws Affect the Intertemporal Behavior of Married Couples?” The American Economic Review 105 (8): 2295–332. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20120234.Search in Google Scholar

Wolfers, J. 2006. “Did Unilateral Divorce Laws Raise Divorce Rates? A Reconciliation and New Results.” The American Economic Review 96 (5): 1802–20. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.96.5.1802.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Strategic Analysis of Petty Corruption with an Entrepreneur and Multiple Bureaucrats

- Environmental Policy in Vertical Markets with Downstream Pollution: Taxes Versus Standards

- The Impact of the CARES Stimulus Payments on COVID-19 Transmission and Mortality

- Reverses in Gender Salary Gaps Among STEM Faculty: Evidence from Mean and Quantile Decompositions

- Downstream Profit Effects of Horizontal Mergers: Horn & Wolinsky and von Ungern-Sternberg Revisited

- The Moderating Role of Decisiveness in the Attraction Effect

- Pension Reform and Improved Employment Protection: Effects on Older Men’s Employment Outcomes

- Relational Voluntary Environmental Agreements with Unverifiable Emissions

- Letters

- Labor Demand Responses to Changing Gas Prices

- Early Childhood Education Attendance and Students’ Later Outcomes in Europe

- The Long-Term Effects of Unilateral Divorce Laws on the Noncognitive Skill of Conscientiousness

- Lab versus Online Experiments: Gender Differences

- Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and HIV Incidence

- Variants of Gender Bias and Sexual-Orientation Discrimination in Career Development

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Strategic Analysis of Petty Corruption with an Entrepreneur and Multiple Bureaucrats

- Environmental Policy in Vertical Markets with Downstream Pollution: Taxes Versus Standards

- The Impact of the CARES Stimulus Payments on COVID-19 Transmission and Mortality

- Reverses in Gender Salary Gaps Among STEM Faculty: Evidence from Mean and Quantile Decompositions

- Downstream Profit Effects of Horizontal Mergers: Horn & Wolinsky and von Ungern-Sternberg Revisited

- The Moderating Role of Decisiveness in the Attraction Effect

- Pension Reform and Improved Employment Protection: Effects on Older Men’s Employment Outcomes

- Relational Voluntary Environmental Agreements with Unverifiable Emissions

- Letters

- Labor Demand Responses to Changing Gas Prices

- Early Childhood Education Attendance and Students’ Later Outcomes in Europe

- The Long-Term Effects of Unilateral Divorce Laws on the Noncognitive Skill of Conscientiousness

- Lab versus Online Experiments: Gender Differences

- Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and HIV Incidence

- Variants of Gender Bias and Sexual-Orientation Discrimination in Career Development