Abstract

According to Jeff McMahan, Israel had a right to defend itself against Hamas’s aggression, but the Palestinians too had a right to fight against Israel to undo the injustice of its occupation of Palestinian territories. Thus, both sides had a just cause for war. However, both sides failed to satisfy other ad bellum conditions, with Hamas failing only the necessity condition and Israel failing both the necessity and proportionality conditions. McMahan concludes that Israel’s war against Hamas was unjust, unlike Ukraine’s war against Russia, which he views as ‘paradigmatically just.’ I reject his view, arguing that: (a) The strategic goals of Hamas are the annihilation of Israel, the murder of many of its civilians, and the expulsion of others – goals that are manifestly immoral – thus it had no just cause for war. (b) Even on McMahan’s premises, it is absurd to imply a symmetry in the unjustness of Israel and Hamas. (c) McMahan’s understanding of ad bellum necessity and proportionality is untenable. (d) Israel did, in fact, satisfy the necessity condition. (e) If Ukraine’s war is proportionate, as McMahan assumes, then all the more so is Israel’s war in Gaza.

The subtitle of Walzer’s seminal book (1977) Just and Unjust Wars is “a moral argument with historical illustrations.” Indeed, the book is full with such illustrations which give the reader a good sense of just how complex, difficult and momentous are the ethical decisions about going to war and in war. Such philosophical attention to real-life wars has by and large disappeared in most of contemporary discussions of war, that prefer hypothetical cases to examples from real wars in the past or in the present. Against this background, Jeff McMahan, one of the leading philosophers of war today, is commendable for going beyond hypothetical thought experiments to a detailed analysis of Israel’s war in Gaza (2024a), an analysis which also yields a clear conclusion. More or less at the same time, he also wrote a paper on Ukraine’s war against Russia (2024b) which is similarly engaged in what one might call ‘applied ethics of war’. Though my focus will be on McMahan’s paper on Israel, I believe that reading it alongside the one on Ukraine is illuminating.

The skeleton of McMahan’s argument is as follows: Although Israel had a right to defend itself against Hamas’s aggression, and, in that sense, had a just cause for war, the war failed to satisfy two essential conditions, namely, the ad bellum necessity condition [ABN] and the proportionality one [ABP]. For McMahan, these conditions are separate, hence his conclusion that Israel’s war was unjust can rely on each of them independently of the other. Since, in his view, the ad bellum conditions are prospective,[1] he argues that when Israel decided to go to war against Hamas the belief that the war would be necessary and proportionate was implausible. Given these assumptions, the launching of the war was morally impermissible.[2]

I start with his argument about ABN (Section 2) and then, after demonstrating that it fails, turn to his argument about ABP (Section 3), which, in my view, fails as well. Section 4 compares McMahan’s position on Israel’s war to his position on Ukraine’s, concluding that if Ukraine’s war is justified, as McMahan assumes, all the more so regarding Israel’s war. Section 5 proposes a more plausible interpretation of ABN and ABP, which McMahan could also accept. Section 6 summarizes the main disagreements between McMahan and myself regarding ABN and ABP in general and regarding the relevant factual assumptions about Israel’s war.

Beforehand, however, let me present McMahan’s general perception of the war between Israel and Hamas, namely, what, in his view, each side was fighting for and, in what sense, both were in the wrong.

1 The Alleged Moral Symmetry Between Hamas and Israel

The most important condition that a war must satisfy in order to be permissible is that it has a just cause, or, as McMahan sometimes puts it, has “predominantly just aims” (2024b, 54). In his view, both sides in the Gaza war satisfied this condition. With regard to the Hamas side, he says that “the Palestinians have all along had just goals” (388); to be freed from Israeli occupation, to have the lands stolen from them returned and to establish an independent Palestinian state. As for Israel, it also had a just cause because “it has a right of defense against the murder, maiming, and kidnapping of its citizens by Hamas, and thus in principle has a just cause for war against Hamas” (389). (The ‘in principle’ clause is a bit puzzling because it gives the impression that in actuality Israel did not have a just cause, yet McMahan never argues for that.)

According to McMahan, although both sides had a just cause for war, they both failed other ad bellum conditions, hence were overall unjust. Both Hamas and Israel violated ABN, and Israel also violated ABP. The Gaza war, therefore, was “an unjust war on both sides” (387) and, in that sense, manifested a sort of moral symmetry between Hamas and Israel.

I believe that this picture is deeply flawed. It is based on an understanding of Hamas’s goals that is inconsistent with Hamas’s statements and actions over the years. Once these goals are clarified, the alleged symmetry between Hamas and Israel will prove to be incorrect.

Let me start by drawing attention to how McMahan shifts constantly in the paper between talk of ‘Hamas’ and talk of ‘Palestinians’, lending the impression that all Hamas aims at is the protection of the legitimate interests of the Palestinians. He starts by saying that Hamas’s war against Israel was unjust and then immediately goes on to mention the claims of justice that ‘Palestinians’ have against Israel. On the following page he talks about the acts of violence by Hamas, and again immediately shifts to talk about how the Palestinians having all along just goals (388). Moreover, when making the point that Palestinian terror has been counter-productive, he mentions Hamas and PLO together, arguing that because both organizations “have repeatedly engaged in acts of terrorism, Americans have tended to think of Palestinians as terrorists rather than victims of injustice” (388). Thus, in McMahan’s eyes, Hamas is a national liberation organization, just like the PLO, whose goals are predominantly just, but whose methods are by and large not. He probably does not even regard Hamas as worse than the PLO; when he mentions three paradigm terrorist groups, he puts PLO, not Hamas, on his list, in addition to Al-Qaeda and the IRA (2009a, 362).

But this is not how Hamas sees its goals, regarding which it has been very clear from the beginning. I cite below some extracts from the 1998 Hamas Charter which leave no doubt about its murderous anti-Semitism, its desire to wipe out Israel, and its fierce opposition to any arrangement that would allow Israel to exist. The Charter is also very clear about Hamas being first and foremost a Jihadist movement, like Al-Qaeda and ISIS, rather than a national liberation one:

Israel will exist and will continue to exist until Islam will obliterate it, just as it obliterated others before it. (Preamble) The Day of Judgment will not come about until Moslems fight Jews and kill them. Then, the Jews will hide behind rocks and trees, and the rocks and trees will cry out: ‘O Moslem, there is a Jew hiding behind me, come and kill him’. (Article 7) The land of Palestine is an Islamic Waqf [Holy Possession] consecrated for future Moslem generations until Judgment Day. No one can renounce it or any part, or abandon it or any part of it. (Article 11) [Peace] initiatives, and so-called peaceful solutions and international conferences are in contradiction to the principles of the Islamic Resistance Movement ... Those conferences are no more than a means to appoint the infidels as arbitrators in the lands of Islam … There is no solution for the Palestinian problem except by Jihad. Initiatives, proposals and international conferences are but a waste of time, an exercise in futility. (Article 13)[3]

Without revoking the original Hamas Charter, Hamas added to it in 2017 another document with somewhat softer phrasings which, in essence, conveys the same message. Here are a few extracts:

The Islamic Resistance Movement ‘Hamas’ is a Palestinian Islamic national liberation and resistance movement. Its goal is to liberate Palestine and confront the Zionist project. Its frame of reference is Islam, which determines its principles, objectives and means. Hamas believes that no part of the land of Palestine shall be compromised or conceded, irrespective of the causes, the circumstances and the pressures and no matter how long the occupation lasts. Hamas rejects any alternative to the full and complete liberation of Palestine, from the river to the sea. Resisting the occupation with all means and methods is a legitimate right guaranteed by divine laws and by international norms and laws.[4]

Of the various factual and normative claims I make in this paper, I think that those regarding Hamas’s strategic goals and its methods are simply undeniable.[5] How serious Hamas is in its talk about liberating the entire of Palestine is evident, inter alia, from a conference that it convened in 2021 to discuss preparations for the future administration of the state of Palestine following its liberation. Among other things, the conference recommended that rules be drawn up for dealing with the Jews, including defining which of them will be killed or subjected to legal prosecution and which will be allowed to leave. It also called for preventing a brain drain of Jewish professionals, and for the retention of “educated Jews and experts in the areas of medicine, engineering, technology, and civilian and military industry… [who] should not be allowed to leave.” In his statements for the conference, Hamas leader Al-Sinwar stressed that “we are sponsoring this conference because it is in line with our assessment that victory is nigh” and that “the full liberation of Palestine from the sea to the river” is “the heart of Hamas’s strategic vision.”[6]

It therefore seems fair to regard Hamas as a Nazi-like, or an ISIS-like organization.[7] Its goal is not to establish a Palestinian state alongside Israel, but to eliminate Israel, kill many of its Jewish residents, expel many others, curb the basic freedoms of those that remain, and establish a religious Islamic state in its place. The attacks of October 7 were a chilling demonstration of what Hamas aims at and of what many Israelis (in the first place Israeli Jews, but not only them) should expect if Hamas manages to realizes them.

Let me return now to the symmetry thesis. If I’m correct in my description of Hamas and its goals, then Hamas’s war against Israel was evidently unjust, on par with wars initiated by organizations like Al-Qaeda and ISIS, and by countries like Nazi Germany. Accordingly, Israel’s war, defending itself from Hamas, was paradigmatically just (at least regarding its cause). No symmetry, then, between the two parties.[8]

McMahan would still insist that Israel failed to satisfy ABN or ABP, but even if he was right on this, it would be a fundamental mistake – a moral mistake – to conceptualize the war as one between ‘two unjust sides.’[9] An analogy might help: Suppose a man sexually gropes a woman against her consent. She is armed, and the only way she can defend herself is by shooting the man. She does so, badly wounding him. Let’s also assume that the harm to the aggressor is disproportionate. Nonetheless, saying that ‘both of them were unjust’ would be outrageous, creating a false symmetry between aggressor and victim. Similarly with wars. Suppose, just for the sake of argument, that Britain’s war against Nazi Germany was disproportionate; that it caused, both intentionally and collaterally, too many casualties and too much harm relative to the harm that it prevented. Even if that were true, it would be morally infuriating to suggest that the war between Britain and Germany’s in the Second World War was ‘unjust on both sides,’ implying again some kind of moral symmetry.[10]

Be that as it may be, McMahan is right to assume that having a just cause is not enough to justify going to war because ABN and ABP also need to be satisfied. The next sections will examine his claim that Israel failed to do so.

2 Was Israel’s War Against Hamas Necessary?

According to ABN, a war must be avoided if there are non-violent ways that could achieve more or less the same goal. In McMahan’s view, such ways were available to Israel after October 7, hence its war against Hamas was unnecessary, and therefore unjust. I trust he doesn’t deny Israel’s right on that day and the following few days to fight against the thousands of militants and the ordinary Gazans who infiltrated Israel.[11] Rather, I take him as arguing that once Israel regained control over the areas within Israel in which Hamas carried out its atrocious attacks, Israel should have sought a cease-fire with Hamas and started negotiations for the release of the hostages.

But what about Israel’s need to defend itself from further October 7-style attacks, or worse? McMahan suggests many things that Israel could have done short of going to war, that, in his view, would have been no less – in fact more – effective in providing defense: Strengthen the barrier between Gaza and Israel, indefinitely deploy far more forces on the Israeli side of that barrier, improve the Iron Dome missile defense system, repair the intelligence systems that failed to provide adequate warning on October 7, work in closer cooperation with Egypt to prevent the smuggling of components of missiles into Gaza, station UN or other international peacekeeping forces in Gaza and the West Bank, dismantle the blockade of Gaza,[12] begin the withdrawal of Israeli settlers from Palestinian territories; and begin to act in good faith toward the establishment of a Palestinian state. In McMahan’s estimate, if Israel had implemented even some of these measures after October 7, Hamas would have been unable, either physically or politically, to kill or injure more than a very small number of Israelis (402–3). In the long run, these measures, especially the withdrawal from the Occupied Territories and the establishment of an independent Palestinian state would guarantee better defense for Israelis than going to war.

I will soon discuss these factual assumptions about Hamas and Israel, but beforehand, I wish to note their radical implications for the ethics of war in general. What McMahan’s approach implies is that a country has a right to go to war only for the sake of undoing ongoing unjust attacks, typically in the form of invasions into its territory, but also in the form of missile- or air attacks. Once the invading forces are removed or the firing stops, war will almost always be unnecessary because other defensive measures would be available: deploying more units along the border, erecting higher fences, improving air-defense systems, and so forth. On this view, an unjust aggression such as carrying out lethal attacks against your enemy – such as unexpectedly firing missiles at their towns or military facilities – is risk-free, as long as the firing ceases and you make it clear that you plan no further attacks for the time being. Those attacked by you would not be allowed to go to war in order to neutralize your military capabilities or deter you from further aggression, but would be expected instead only to improve its defense capabilities.

Let us look at two examples, starting with 9/11. Was the US allowed to go to war against Al-Qaeda (or against Afghanistan) in response to the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon? Although McMahan has much criticism concerning how the actual war in Afghanistan unfolded, he admits that at least “the initial strikes against al Qaeda bases in Afghanistan in 2001” were just (McMahan 2013 , 9). But, on his understanding of ABN, one wonders why. After all, there was no imminent threat to the US from the people placed in those bases. And as for defense from future attacks, that could have been achieved – like, supposedly, in the case of Israel – by improving the security arrangements in airports and in aircraft, building stronger fences along the American borders, improving America’s air-defense systems, upgrading its intelligence agencies, and so on. It is also noteworthy that in his discussions of the Afghanistan war, notably McMahan (2011), he talks a lot about the question of proportionality but not on that of necessity which again, would be natural on the basis of his approach in McMahan (2024a).

My second example is Ukraine’s war which, for McMahan, was a “paradigmatically just war against unjust aggression” (2024b, 55). I don’t think he uses this expression about any other war, so he must assume that this war satisfied all ad bellum conditions. But did it satisfy ABN? McMahan is correct in claiming that “when Russian tanks sought to encircle Kyiv, there was no alternative at all to armed resistance” (2024b). But the threat to Ukraine was not the very entrance of Russian forces to Kiev, but the loss of political independence. Could that have been prevented without war? In McMahan’s view, “it is conceivable that the Ukrainians could ultimately have maintained their political independence by engaging in mass nonviolent resistance,” which seems to imply that opting for war, which to date has led to approximately a million casualties,[13] was unnecessary. McMahan’s response is that the required nonviolent resistance “would have required years of preparation and training of the civilian population and thus was not an option when the tanks and ground forces arrived.” But supporters of nonviolent resistance as an alternative to war don’t assume that it can stop the enemy tanks from completing their mission. What such resistance is meant to do is to make it too costly for the conquering country to sustain its occupation. In the case of Ukraine, as in other cases, this could have taken a long time, but – again on revisionist grounds – the actual war with all its casualties still seems a much worse alternative.[14]

But suppose nonviolent resistance could not have regained Ukraine’s independence after Russian conquest. One might still ask whether the war did better, in terms of preserving Ukraine’s sovereignty and independence than the alternative of negotiations prior to the Russian invasion, coupled with a willingness to compromise. As I write these lines in March 2025, there are indications of the war coming to an end as a result of some compromise between the warring parties.[15] If this happens, the question that many will ask – and that McMahan in particular would have to ask – is whether the arrangement that Ukraine will have accepted in, say, mid-2025, could not have been reached at in 2022 or earlier, avoiding the war with all its disastrous consequences. At least post factum, the war might well seem unnecessary. Moreover, ex ante, President Zelensky might have had good reason to suspect all along that Ukraine’s odds of fully blocking Russian aggression were not high and, therefore, that going to war was not the least harmful option for protecting Ukrainian interests.

Let us turn now to McMahan’s arguments for the claim that Israel violated ABN in going to war against Hamas. One main argument is that if Israel had improved its defensive measures that would have been enough to take care of future attacks by Hamas, hence war was unnecessary. But installing such improvements was precisely what Israel did after the previous rounds of violence in Gaza, which did not prevent the horrors of October 7. Among other things, Israel built an advanced sensor-equipped underground wall on its side of the Gaza border, in addition to an above-ground fence more than 6-m-high, and other devices.[16] These measures cost approximately 1.1 billion dollars.[17] What the attacks of October 7 demonstrated is that when some state or non-state actor is determined enough to attack some country or some group, it will almost always find creative ways of doing so, either by high-tech measures, such as sophisticated Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, or by low-tech ones like tractors. McMahan’s implicit assumption that there is almost always a physical or a technological way of dealing with threats from one’s enemies, is groundless. To date, for instance, there is no way to block mortar shells, and while Iron Dome can take care of most missiles (alas it guarantees only 90 % success[18]), it is much less effective in blocking UAVs.[19] Defense technology may improve, but so can attack technology. Thus, even if Israel had followed McMahan’s advice instead of going to war, it would have been vulnerable to mortar and other artillery fire and especially to the use of UAVs and explosive kites launched simultaneously at many targets across Israel. These are some of the threats that we already know of; there are many others that would be invented by creative Gazans or by their more capable sponsors like Iran – just as occurred on October 7.[20] Military history if full with examples of defense lines that were considered excellent, but time and again failed: the Sigfried Line, Maginot line, Bar Lev Line, and more.

Another central reason to suspect that refraining from war would have led to less security to Israel has to do with the effects of such refrainment on deterrence. Not going to war against Hamas would have sent a dangerous message both to Hamas and other Palestinian organizations, as well as to Hezbollah and Iran, that one can carry out horrific massacres against Israelis and get away with it. An anecdotal illustration of the war’s success in promoting the required deterrence can be found in an interview with Mousa Abu Marzouk, the head of Hamas’s foreign relations office, in February 2025, who said that he would not have supported the attack on Israel had he known of the devastation it would wreak on Gaza (Rasgon 2025). It seems plausible to assume that Abu Marzouk is not the only member of Hamas who will think twice before attacking Israel again, a result that would not have been achieved by Israel simply improving its defense measures. Also relevant is Nasrallah’s famous admission after the 2006 war with Israel that, had he known kidnapping two Israeli soldiers would trigger such a devastating war for Hezbollah, he wouldn’t have ordered the abduction.[21] Indeed, Israel’s response in 2006 kept Hezbollah quiet for many years and was probably one of the reasons that Hezbollah’s attacks against Israel following October 7 were relatively cautious and restrained – certainly compared to what it could have done. (For more on the war’s effectiveness in promoting deterrence, see below towards the end of Section 4.)

McMahan would probably respond by saying that such improvement is just one part of the story, the other being the withdrawal from the West Bank and the establishment of an independent Palestinian state. But given Hamas’s unequivocal denial of Israel’s right to exist in any of its borders and its consistent opposition to the two-state solution, how could the advancement of this solution have pacified Hamas? Precisely the opposite follows, namely, that so long as Hamas maintains its military and political power, it will jeopardize any attempt to normalize the relations between Israel and the Palestinians in the form of two states living peacefully alongside each other.

Almost everybody agrees today that the attempts to contain and appease the Nazis in the years leading to WWII were a mistake. Given the aspirations of the Third Reich and its utter disrespect for ethical or legal norms, the only way to stop Hitler was by force. I assume McMahan shares this assessment. But if Hamas is a Nazi-like organization – if its actions are worse than those of Hamas itself, McMahan himself says[22] – why does he think that the threat it poses can be averted by diplomacy or by improving Israel’s defense system? To answer this question, McMahan distinguishes between the actions of the few and the beliefs of the many; “not all Palestinians are Hamas – the majority of Palestinians don’t support Hamas” (Seifert 2023). To see why this answer is unsatisfactory, imagine that the majority of ordinary Germans opposed Nazism. Would that have meant that Chamberlain was right in his appeasing policy? Obviously not, because the threat posed to Europe and the entire world was not by the German people but by the Nazi regime which oppressed mercilessly any sign of opposition. So the discovery that most Germans were unhappy with Hitler would have provided no reason to change one’s view about the necessity of going to war against Hitler in 1939.

The same applies to the Ukraine war, which, as you recall, McMahan strongly supports. Unlike the case with Nazi Germany, here we have reliable polls that indicate lack of majority support for the war[23] – but that doesn’t bring McMahan to infer that going to war was unnecessary. The war is against a ruthless regime led by a despotic leader, hence those threatened by it can’t rely on the attitudes of the general Russian public to stop or to moderate Putin’s aggression. And the same, finally, with Hamas: Given its reign of terror, not only against Israel but against any opposition to the regime within Gaza, even if it were the case that the majority of Palestinians didn’t support Hamas, that would be insufficient to show that the war against Hamas was unnecessary.

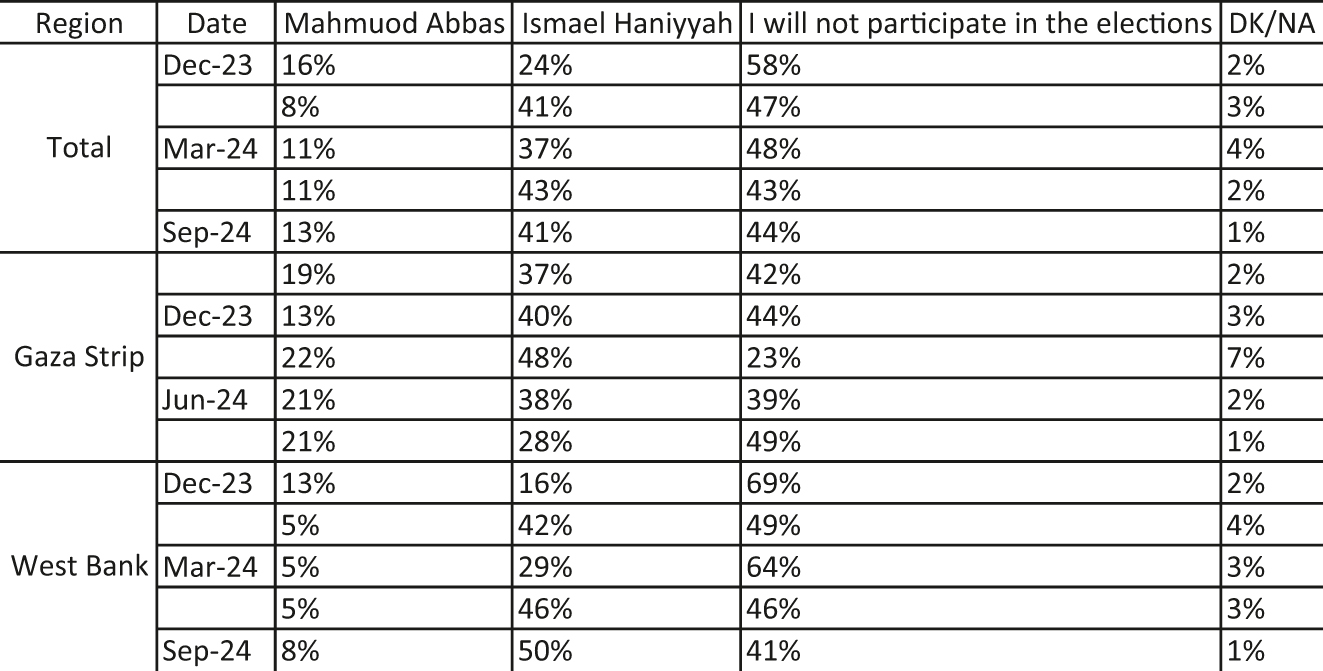

But this is actually not the case. One can rely on polls which I immediately do, but one can also rely on elections which are of course a better indication. In the last Palestinian elections, carried out in 2006, a majority of Palestinians preferred Hamas, granting it 74 out of the 132 seats in the Legislative Counsel, with Fatah getting only 43 seats![24] There were elections scheduled for May 2022, but President Abbas postponed them, most probably because, on the basis of public polls, he feared another Hamas victory (Abu Amer 2021). Indeed, polls reveal consistent support for Haniyyah of Hamas over Abbas of Fatah even before October 7 and more so following the war, as shown in the following table (Figure 1):[25]

If new presidential elections are to take place today, and Mahmud Abbas was nominated by Fateh and Ismail Haniyeh was nominated by Hamas, whom would you vote for?

Thus, the fear that free elections in the territories would end up with a Hamas victory which would enable it to advance its strategic goals was clearly warranted. And of course, there was the danger of Hamas taking control over the West Bank by force, regardless of elections, following the enormous rise in its popularity after the October 7 attacks and its success in releasing Palestinian prisoners in exchange to the Israeli hostages. So long as Hamas retains its power, no real progress can be made towards a reliable peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians.[26]

Finally, on this point, the responses by Fatah and the PA to the October 7 events undermine the distinction – so crucial for supporters of the Two-State Solution – between Hamas (the bad, ‘extreme’ guys), with whom peace is indeed impossible, and the PA (the good, ‘moderate’ guys), with whom it is. The PA could have taken this opportunity to clearly distance itself from Hamas by unambiguously condemning the massacre and by calling for the immediate and unconditional release of all Israeli hostages. But it did not. Criticism of Hamas was reported by the PA official news agency to have been raised by Mahmud Abbas during a phone call with Venezuelan President, but the criticism was then removed from the agency’s website.[27] Later the PA denied the involvement of Hamas in the Massacre of more than 360 young Israeli civilians in the music festival and in the other atrocities carried out there.[28] And when Hamas leader and planner of the October 7 attack was killed, the PA expressed its condolences on the ‘martyrdom’ of Sinwar, calling him a ‘great national leader.’[29]

McMahan might concede the risks that Israel faced on October 8, but argue that they were worth taking because the costs of war were higher and, moreover, were certain. Hence, if one takes probabilities into account, avoiding war ought to have prospectively be seen as less harmful and therefore morally obligatory. But this response underestimates both the odds of the above risks materializing and their enormity. If Hamas had retained its military and political power after October 7, the threat to Israel from all directions would have been momentous, especially so if Hamas later won the Palestinian elections thanks to its success in humiliating Israel on October 7. Elsewhere, McMahan argues that “because decisions about the resort to war are typically made by those whose only risks in the war would be political in character, these people are often disposed to underestimate the likely costs of the war for others” (2015, 719). A similar point could be made, mutatis mutandis, about critics calling to refrain from war in the face of enemies with genocidal aims like Hamas.

Finally, even if – just for the sake of argument – we assume that Israel could have defended itself effectively by a host of military and political measures short of war, these would surely have taken quite a while to implement; to improve the Iron Dome, to build an even stronger fence, to find a solution to UAVs etc. – and of course to reach a stable peace agreement. The question is what would have happened in the meanwhile. In the week or so following October 7, more than 200,000 Israelis had to evacuate their homes along the Gaza border in the south and along the Lebanese border in the north.[30] Some were put in hotels, others moved in with family elsewhere and others found other solutions. Now imagine that Israel had not gone to war against Hamas (or, for that matter, Hezbollah). Surely no sane Israeli living near the border would have gone back to where their neighbors, and sometimes family members, were murdered, mutilated, raped, and kidnapped, until they could be assured that what used to be home was safe. But, as just said, even on McMahan’s best scenario, this would have taken years. Thus, war was certainly necessary to enable the evacuees to return to their homes and rebuild their communities – and to enable Israelis living in Tel Aviv and in other Israeli cities to lead a normal life without constant fear of missiles being fired at them. (Note also that Israel is a very small country, with only one major international airport. Flying in and out of Ben Gurion International airport can be and was in fact stopped repeatedly by missiles fired from Gaza.)

3 Proportionality and the War Against Hamas

As noted above, ABP is a separate constraint on the launching of war, independent of ABN. What ABP requires is a comparison between the harm brought about by war and the harm prevented. (More accurately, since the test is prospective, it requires comparing the harm that can be reasonably expected to result from going to war with the harm that can be reasonably expected to be prevented.) The harm caused by war is roughly that which is caused to people on the other side, whether combatants or noncombatants. The harm prevented is usually a violation of territorial integrity and of sovereignty. Sometimes, however, the harm that is prevented is much worse: mass murder, enslavement, or other egregious violations of human rights.

Let me start with some general comments on ABP which draw on a more thorough analysis of the concept that I offer elsewhere (Statman Forthcoming). Note, first, how demanding it is. Suppose country A is unjustly attacked by country B with the aim of annexing its territory into country B. All non-pacifists would agree that country A has a just cause for going to war in defense of its borders. Suppose further that country B’s attack can only be blocked by means of war, thus ABN is also satisfied. But now suppose that country A cannot win the war without causing disproportionate harm to civilians in country B. The ABP constraint demands that country A refrains from going to war – in effect surrenders to the bad guys.

The first point I’d like to make is that no country in the world would follow such moral advice. It might do so if the threat was very minor, for example, the loss of a tiny piece of territory which is not important to the invaded country either materially or symbolically. But with non-minor threats, I can’t imagine any country surrendering just because of the expected disproportionate harm to its enemy. Thus, the demand seems wholly unrealistic.

McMahan concedes that it is unreasonable to impose a legal prohibition on going to wars that violate ABP, but contends that a moral prohibition nonetheless exists. He offers two reasons why a legal prohibition would be a bad idea: First, “it is necessary for the deterrence of unjust war that victims of unjust aggression fight defensively rather than submit.” Second, “such a requirement would be pointless because it would not be taken seriously” (2017, 143). Yet the same arguments that tell against the imposition of a legal constraint on fighting disproportionate wars tell as strongly against the imposition of a moral constraint on doing so. Hence, the distinction between the legal and moral prohibition McMahan presents here is untenable. The deterrence argument would apply to morality as well because obeying the supposed moral prohibition on fighting wars that violated ABP would have disastrous consequences for deterrence. And since morality is supposed to be action-guiding, there is not much point in formulating moral rules that will certainly be ignored.

All the more so if the threats posed are not just to territorial integrity or sovereignty but to the most fundamental human rights, safety, and simply the lives, of those of the attacked country, like in the case of the threats by Hamas. It is beyond imagination that a country or, for that matter, some ethnic or religious group, would be threatened with mass murder, expulsion and the like, would believe that it could defend itself, saw no other way of doing so except going to war – and nonetheless refrained from going to war just because of the estimated disproportionate harm to their enemies. For ABP to be action-guiding in the actual world, it must, then, be limited to minor threats only.

Second, the expectation that countries refrain from going to war when ABP is not satisfied seems unfair. Both Norman (1995) and Rodin (2002) have argued that ABP cannot be satisfied in most wars of national defense because the harm caused by war – the dead, the wounded, the destruction – is usually much worse than the harm prevented (loss of territory or sovereignty). This entails that such wars simply ought not to be fought; that surrender is the only possible moral option. But this conclusion is “morally unacceptable” (Rodin 2002, 198) or “morally unthinkable” (Norman 1995, 219). To take a real-life illustration of such a state of affairs, suppose that China seeks to take Taiwan by force. Suppose further that Taiwan, with help from the West, can defend itself, although the war will be long and bring about disproportionate harm to Chinese civilians because, let’s assume, many of China’s military facilities are located in proximity to residential areas. To say that, because of this expected harm to the Chinese, Taiwan would be morally required to surrender is unfair. All the more so if the Chinese sought not only to annex Taiwan but to murder many of its residents, expel many others, and so forth.

Third, a prohibition on launching disproportionate wars – mainly on the basis of the excessive (collateral) harm to civilians – would provide a powerful incentive to rogue states or non-state actors to locate as many of their military facilities and troops as possible under or in residential areas so that their enemies will not be able to hit them without causing disproportionate harm to civilians – which is precisely Hamas’s strategy. In other words, such a prohibition would enable rogue states or non-state actors to morally coerce their enemies to refrain from fighting, in effect to surrender.[31]

Fourth, epistemically imperfect subjects as humans are simply unable to make reliable ABP calculations. According to McMahan, they would need to assess, inter alia, whether the people they kill on the unjust side are liable to defensive killing, but that is rather challenging because, as McMahan himself argues –

The degree to which a person is liable to defensive action, and thus how much harm it can be proportionate to inflict on him, depends on various factors, such as the magnitude of the threat he poses, the degree to which he is morally responsible for that threat, whether the threat can be eliminated or diminished (and if so, by how much) by harming him, and so on. (2011, 152)

The problem, of course, is that before going to war nobody can reliably predict how many casualties the enemy will suffer, what the causal contribution of each of them will be, how responsible they will be for the unjust threat posed by their side, how much will be gained by killing them, and so forth. And then there is the need to compare the harm to the enemy with the harm prevented. Unless it is the harm of mass-murder, we’d be required to compare incommensurable values – harm to life, limb and property, on the one hand, loss of political sovereignty or of territory, on the other. McMahan indeed concedes that “our best efforts to predict the consequences of going to war are highly fallible” (2015, 701) and that, due to the problem of incommensurability, “it is obviously extremely difficult to get the various goods and evils of these different types onto the same scale for aggregation” (1993, 521). It is surprising, then, that he nonetheless believes that ABP can serve as a significant constraint on launching wars.

David Rodin, another prominent revisionist, also points to such difficulties in applying ABP:

Not only are these costs and benefits likely to be variable over time, but forward-looking assessments can only ever be estimates and therefore subject to a risk of error. This has always been a problem for forward-looking ad bellum judgments since the task of estimating the likely effects of a large-scale, highly complex, and adversarial process like war is fiendishly difficult. (2023, 135, italics added)

To this we should add the influence of a long list of psychological biases that make it hard to adequately assess the cost and the duration of big projects, like constructing a new train line. Of these, Altman notes that false optimism has long been thought to rank “among the most important causes of war” (Altman 2015, 284).[32]

These insurmountable difficulties in making reliable prospective assessments about the proportionality of wars ‘as a whole’ increase the odds of falling prey to hindsight bias (Flyvbjerg 2021, 538–40) and assuming that if a war ultimately caused very harmful results relative to the harm prevented, the relevant agents could have plausibly predicted them at the time of their decision to go to war.

It would have been helpful if McMahan had provided examples of wars that had a just cause but were nonetheless unjust (or unjustified) on account of being disproportionate, in order to help the reader to understand how such calculations should be made. Consider WWII. In McMahan’s view, Britain’s war against Nazi Germany was just in the sense of having a just cause. But given the disastrous results of the war, including the killing of so many German civilians, was it also proportionate? And does it make sense to talk about Britain’s war as distinct from the American – and other allies’ – war against the Nazis? If it doesn’t, one wonders how the attacks on Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki affect the proportionality of the war (that is, the Allies’ war) against Germany as a whole.

What is the practical implication of the recognition that ABP is almost always beyond our epistemic capabilities? Given the strong moral presumption against killing people, Rodin’s conclusion seems natural, namely, “that the burden of proof for proportionality should be structured to not permit military action unless the consequences can unambiguously be shown to be proportionate” (2023, 137). The problem is that this burden can hardly ever be lifted, i.e. showing unambiguously, prior to going to war, that the harm the war will cause will be less severe than the harm it seeks to prevent. The only respectable conclusion seems to be some form of pacifism, but neither Rodin nor McMahan take this route.[33]

Fifth, McMahan attempts to get around the above epistemic difficulties by relying on what he regards as robust intuitions about the trolley problem, particularly those supporting the diversion of the trolley in order to save the lives of five workers who would otherwise be killed at the expense of killing one person on the side track. I don’t have the space to go into the details of this move so will limit myself to some brief comments:

As mentioned earlier, most just wars are not fought for the sake of defending the actual lives of the attacked country’s civilians; their lives would be much better protected by simply avoiding the war and negotiating some compromise on sovereignty or territorial integrity.

People’s intuitions about the trolley case are far less robust than McMahan seems to assume. It has been demonstrated, for instance, that the strong opposition to throwing somebody on the tracks in order to save the five weakens if doing so does not necessitate physical pushing (Greene 2016). My own guess is that there is nothing sacred in the ratio of one to five; had Philippa Foot designed the trolley case with a different ratio of, say, one to three or one to six, this is the ratio that would have stuck in our minds.

Given the wide permissiveness for using lethal force at war (Miller 2016, 208), why assume that intuitions regarding the use of such force in non-war contexts would be a good guide for killing at war? Thus, to the extent that McMahan’s argument is grounded in the robustness of intuitions on the trolley dilemma, there is no reason to assume that they are a good indicator for intuitions about killing in war.

If widely held intuitions can inform us about making proportionality judgements in war, we should, therefore, rely on intuitions about the collateral killing of civilians at war, instead of on train tracks. Yet an empirical study conducted several years ago (Statman et al. 2020) has shown that even experts – law and philosophy professors who specialize in the ethics of war – can’t reach reasonable convergence on questions concerning the proportionality of harm to civilians relative to military value. The fact that many experts reach radically different conclusions about whether an attack on an enemy headquarters is proportionate should prompt caution, maybe even abstaining from judgment in this area (de Wijze, Statman, and Sulitzeanu-Kenan 2022). And although the study focused on in bello rather than ad bellum proportionality, achieving convergence on the latter seems even harder. In bello assessments of proportionality involve comparing the military value of a single attack with its side effects on civilians. Ad bellum assessments require much more: comparing the cumulative harm caused by all military actions to the harm prevented (which also comes in different shapes and forms). It would, therefore, be astonishing if these professors managed to achieve reasonable convergence in their judgments regarding ABP.

Finally, since McMahan focuses on the war ‘as a whole,’ the subsection in his paper on in bello proportionality (Section 7.1) is somewhat out of place. Most wars – probably all – include some violations of in bello proportionality, but this alone does not render them ad bellum disproportionate. It is, therefore, unclear what we are supposed to infer about the morality of the war ‘as a whole’ from the single incident described in this section, namely, the hundreds of Palestinians killed during the rescue of four Israeli hostages. Moreover, as just noted, for McMahan, the relevant proportionality test is prospective rather than retrospective. This implies that, to establish in bello disproportionality in this incident, one would have to demonstrate that Israel had good reason to anticipate such a high toll of casualties in the rescue operation. McMahan does not attempt to do this and instead bases his judgment on the actual number of casualties. But in fact, if the Israeli plan had gone as intended, there would likely have been few, if any, Palestinian casualties. What happened was that one of the cars intended to evacuate the hostages failed to start. As a result, Palestinian militants armed with machine-guns and grenades opened fire on the rescuers, who had to call for help and cover, resulting in many deaths and casualties (Jahjouh, Jeffery, and Chehayeb 2024).

4 McMahan on Proportionality in Gaza and in Ukraine

As we saw above, in McMahan’s assessment, Ukraine’s war was a ‘paradigmatically just war.’ I raised earlier some reservations regarding its necessity within the revisionist framework. When we turn to proportionality, the reservations are even more troubling. I already mentioned above the ‘staggering toll’ (NYT, August 18, 2023) of the dead and the wounded in the war, which naturally raises the question of whether the harm prevented by the war was important enough to justify it. Norman (1995) and Rodin (2002) would almost certainly answer in the negative. As indicated above, a Russian victory would not have led to anything remotely close to a genocide of the Ukrainians or to other large-scale crimes. Rather, it would have weakened or – in the worst-case scenario – put an end to Ukrainian political self-determination. But Ukrainian national identity would have most probably survived this crisis, just as it did under decades of soviet rule.

To address this challenge, McMahan removes from the proportionality equation in this context two considerations that he accepts elsewhere. The first is harm to (unjust) enemy combatants. Against what he regards as “the dominant view in just war theory,” he argues that “both war and individual acts of war can be disproportionate in the narrow sense – that is, objectionable solely because of their effects on unjust combatants” (2011, 152). However, when discussing Ukraine’s war, McMahan takes a different stance, asserting that the war “cannot be disproportionate because of the number of casualties among Russian soldiers.” He links this view to the observation that “each Russian soldier fighting in Ukraine is morally liable to be killed by Ukrainian forces” (152). Yet this reasoning would apply to almost all unjust soldiers, whose deaths McMahan explicitly claims should factor into proportionality assessments.

The second consideration that McMahan removes from the equation in the proportionality calculation about Ukraine’s war is harm to people on the just side. Elsewhere, he explicitly says that “expected harms that [Just Combatants] would suffer in a just war count, along with harms that civilians on the just side would suffer, in determining whether the resort to war by their leaders would be proportionate in the wide sense and therefore permissible” (2015, 698). He uses this rationale in his discussion of war in Gaza as well, arguing that “the war has resulted in the deaths of more Israelis – none of whom would have been combatants had the invasion not occurred – than would have been killed by Hamas had those defensive measures been implemented without the invasion” (405). But, surprisingly, with regard to Ukraine, he submits that “it is the Ukrainians’ right to decide whether they would rather endure the risks of continued war or accept the certainty of subjugation to Russia” (McMahan 2024b, 58) and supposedly it is also the right of Ukraine’s leader to continue the war in spite of the increasing number of casualties and the decreasing odds of victory.[34]

There is a third move that McMahan makes to substantiate his view about the justness of Ukraine’s war but not other wars – in particular, its success in satisfying ABP – which has to do with deterrence. McMahan acknowledges the vital importance of deterrence in international relations and accepts that a war’s success in strengthening deterrence can sometimes balance the otherwise excessive harm to the unjust side.[35] Indeed, regarding the Ukrainian war, McMahan believes it is having a significant effect in deterring other potential aggressors. He cites, in agreement, Paul Krugman, who notes that “Russia’s failures in Ukraine have surely reduced the chances that China will invade Taiwan,” and then adds that “the sacrifices by the Ukrainians have been of great service to all peoples at risk of unjust attack” (2024b, 60). But McMahan provides no evidence for this supposed effect of Ukraine’s war on Russia, China, or other potential or actual aggressors, and I am rather skeptical about it. I should add that, as things look in March 2025, there is a non-negligible chance that Ukraine’s war will have the opposite effect to that predicted by McMahan. This is because deterrence works only if potential aggressors realize either that they can’t get what they desire by force or that the price is too high. But if the war ends with an agreement that grants Russia control over the ‘Russian’ territories in Ukraine, mainly Crimea and the Donbas, it will have shown that aggression actually pays, a message that will be anything but deterring.

The point of this detour into McMahan’s analysis of Ukraine’s war is not so much to criticize it, but to suggest that if, on his view, that war was proportionate, all the more so with regard to Israel’s war against Hamas. The threat that Israel faced – mass murder, wide disruption of ordinary life, personal safety and basic human rights, mass expulsion and undermining of sovereignty – was much worse than that faced by Ukraine, and most probably irreversible if materialized. Hence, if Ukraine had a right to go to a war that has already led to so many casualties,[36] suffering, and wide destruction, just to defend its territorial integrity, then Israel clearly had a right to do so too, with so much more at stake in the Israeli case.

To the threat posed by Hamas in the south of Israel, it is crucial to add the threats posed by Hamas cells in the West Bank[37] and in Lebanon,[38] and those posed by Hezbollah[39] and Iran. Iran has long regarded Israel as an illegitimate state and although, until 2024,[40] it refrained from attacking her directly, it supported Hamas and Hezbollah financially, militarily, and politically in doing so (Alavi 2019). The Lebanese side of the northern border was full of well-equipped tunnels constructed by Hezbollah that were supposed to serve its ‘Radwan force' in executing the plan of invading Israel and carrying out Hamas-like attacks on its towns and villages.[41] In addition, Hezbollah had an arsenal of tens of thousands of missiles, many of them very precise and powerful ones, which could reach almost any point in Israel. If Hamas’s plan had worked out, Hezbollah would have joined with all these measures against Israel,[42] Hamas in the West Bank would have carried out its own attacks, and maybe some Israeli Arabs would have also contributed their share.

Relatedly, it is misleading to describe the threat posed by Hamas and its allies to Israel merely in terms of the number of civilian casualties. The October 7 attacks and the joining of Hezbollah’s attacks on the next day, revealed how vulnerable Israel was and how its civilians were nowhere safe from missiles shot from south or north, or from horrific crimes committed by forces infiltrating the country. The sense of vulnerability and helplessness has been strong among Israelis even after Israel decided to go to war. If Israel had decided not to do so, per McMahan’s advice, the sense would have been much worse, in accordance with Hobbes’s famous description of the state of war: “No place for Industry… no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation… no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and, which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death” (Leviathan, ch. 13, italics added).

Moreover, while there is no evidence for the deterring effect of Ukraine’s war, there is such evidence in the Gaza case. First, I cited earlier a confession by a senior Hamas official saying that he would not have supported the attack on Israel had he known of the devastation it would wreak on Gaza (Rasgon 2025). Second, polls reveal a consistent gap between the support of Palestinians in Gaza for the October 7 attack and that of Palestinians in the West Bank.[43] Except for March 2024, in which there was no difference between the two populations, at all other points at which the poll was conducted, Gazans were less supportive of the attack, often much less, than the West Bankers. The best explanation for this difference is that the Gazans were those who had to bear the actual consequences of the war – the losses, the destruction, the total disruption of normal life, and so on.

Note again that deterrence was required not only vis-à-vis Hamas but also vis-à-vis its strategic allies and supporters, Hezbollah and Iran. The unprovoked attacks by Hezbollah on Israel that started on October 7 had to be met with a clear message to Hezbollah and to the Lebanese who supported or allowed these attacks, that this aggression would not be tolerated. The importance of conveying this message has also to do with the Hezbollah leader Nasrallah’s famous ‘spider web theory,’ according to which Israeli society is as fragile as a spider’s web and lacks the internal resilience and resolve to withstand sustained conflict.[44] This theory became a significant part of the narrative and propaganda of both Hezbollah and Hamas[45] against Israel. It underpinned the expectation that when Israel faces lethal attacks from the south, north, and east – on the ground and in the air – it will crumble and lose its nerve. To disprove this perception, Israel had to make it unambiguously clear that once attacked it is more like a fierce lion rather than a spider, and that nobody should mess with it.

5 Towards a Rule-Based Understanding of ABP and ABN

McMahan has done excellent work analyzing the various factors that determine whether people are liable to defensive killing: the extent of their moral responsibility for the unjust threat, their causal involvement in creating it, the expected consequences of killing them, and so on. Since, for McMahan, killing in war can be justified only by the same principles that govern individual self-defense, all these factors transfer to war as well. Yet considering all these factors as a condition for attacking one’s enemy in the course of war is impossible for epistemically imperfect creatures like us. In the face of this problem, McMahan could opt for pacifism, but he doesn’t. Instead, he opts for a rule-based morality.[46] He submits that soldiers are subject to a rule that categorically forbids the intentional targeting of civilians – even those who bear significant responsibility for the unjust war and whose killing might contribute to victory[47] – as well as to a rule that grants combatants on both sides a blanket permission to attack enemy combatants, even though many of them are not morally liable to defensive killing.

Whether McMahan has the resources to justify this shift from an individualist ethics of war to a rule-based ethics is a question I will leave for another discussion. My point here is just that once he is willing to make this move, he should be open to the possibility of applying it to the ad bellum level as well. Let me very briefly indicate what I mean by that, focusing primarily on proportionality.

As shown in Section 3, in the real world, no one could obtain, even post factum, the knowledge that McMahan requires to determine whether a war was justified as a whole, let alone do so prospectively. The best alternative is to opt for a rule saying that when countries face significant threats, they are released from the obligation to ensure, as a condition for going to war, that the harm the war is estimated to prevent is significant enough to outweigh the harm it is estimated to cause. Undertaking such a rule would make an essential contribution to deterrence; potential aggressors would be better deterred if they knew that their victims would respond immediately with force in the face of aggression than if they believed that their victims would respond militarily only after ensuring that such a response was overall proportionate.

Note: I am not proposing this rule about ABP as an alternative to revisionism, but as a friendly amendment to it. Given McMahan’s shift to a rule-based ethics at the in bello level, I see no reason why he should not make a similar move at the ad bellum level. If soldiers are permitted to set aside first-order considerations about liability, causality, necessity, and related factors when planning their attacks,[48] then politicians could similarly be relieved of the over-demanding task of determining the proportionality of their war as a precondition of going to war against their enemies.

A rule-based reading of ABP is also necessary to prevent rogue states and non-state actors from morally forcing their enemies to surrender by embedding their headquarters, launching sites, and troops in residential areas – a tactic masterfully employed by Hamas. Under the individualistic interpretation of ABP, if this strategy makes it impossible to wage war without causing disproportionate harm to civilians, then war should be avoided, effectively guaranteeing a swift and full victory to the side exploiting this tactic. Such an outcome is deeply unjust.[49] Therefore, countries must be exempted from the requirement to consider the harm to enemy civilians that results from their enemies’ cynical use of human shields. (Note that I’m talking about collateral harm to enemy civilians, not intentional harm, which remains categorically out of question, except in cases of ‘supreme emergency’ which I cannot discuss here.[50] Nowhere in his paper does McMahan accuse Israel of deliberately targeting civilians.)

A rule-based understanding is appropriate for ABN as well. When your enemy is merely preparing for war, or bragging about it, you are almost never permitted to wage war in response, and are obligated to seek other resolutions. However, once your enemy has mobilized its army and invaded your territory, or has started to fire missiles at your towns, expecting you to refrain from responding until you explore a range of other possibilities is unrealistic and renders just war theory irrelevant in the real world. No country would abide by such a requirement, and, given its impact on deterrence, it would be detrimental to world order if countries did. Aggressors should realize that if they initiate war in violation of Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, the countries they attack will have a right to respond by force immediately (as outlined in Article 51), rather than hold off on military action until all non-violent options are thoroughly explored.

I’m not sure McMahan would accept this amendment to his theory. Be that as it may, I suggest that this is the correct way to understand necessity and proportionality at the ad bellum level. If countries face a threat of a significant unjust harm, they have the right to disregard first-order considerations regarding the overall proportionality of the war and to respond immediately with their military might to avert the threat. Similarly, when confronted with such threats, they are required to explore non-violent solutions only before the threat materializes. Once the enemy attacks, they have a right to respond by force. In the immortal lines from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, ‘When you have to shoot, shoot. Don’t talk.’

This understanding of ABP and ABN clarifies why Ukraine’s war – and, a fortiori, Israel’s war – were morally justified. Both countries faced significant unjust attacks and, therefore, had a right to defend themselves. Once attacked, they were exempt from the obligation to assess the overall harms and benefits of the war, as well as from the duty to delay their military response until all non-violent options were exhausted.

6 Summary

The purpose of this paper was to criticize McMahan’s position about Israel’s war in Gaza. Our disagreements are both philosophical and factual, which if often the cases in debates in applied ethics. It might be helpful to briefly summarize them:

According to McMahan, in most cases, ABN would forbid going to war in response to, for instance, a series of deadly missile attacks by one’s enemy, because, in his view, it is almost always possible for a country to improve its military technology and to develop better defensive strategies in order to prevent further attacks. Even in response to a deadly ground invasion, war would be unjustified because once the invaders are pushed out, defensive measures should be opted for rather than offensive.

In my view, defensive measures alone will not suffice against an enemy that is determined enough to attack you. Hence, countries are often allowed go to war in response to such attacks, all the more so when the attacks are explicitly tied to a desire to destroy these countries and carry out acts of genocide.

According to McMahan, although legally a country would not be in the wrong if it launched a war that could be expected to be disproportionate, morally it would. In my view, this requirement would be unworkable, unjust, and detrimental to deterrence. Hence, in line with the contractarian framework developed elsewhere (Benbaji and Statman 2019), the players on the international plain exempt each other from trying to estimate how many casualties the war will bring about, how culpable they are, how necessary it is to harm them, and so on. They particularly exempt each other from considering the harm to enemy civilians which is a result from their enemy’s deliberate strategy of using civilians as human shields by intentionally placing its military facilities and troops in residential areas.

I now turn to our main factual disagreements:

In McMahan’s view, if Israel had refrained from going to war, instead focusing on improving its defensive systems and taking steps to advance the two-state solution, this would have been a more effective way of ensuring its security. In my view, the opposite would have occurred. Hamas’s prestige would have skyrocketed among Palestinians after humiliating Israel and securing the release of most Palestinian prisoners. Most Israelis living near the Gaza border would not have returned to their homes, while Israelis elsewhere would have lived in constant fear of missiles and terror attacks – which would only have increased. Normal life in Israel – its economy, industry, culture, and tourism – would have been severely disrupted.

McMahan contends that, despite Hamas’s long-standing refusal to recognize Israel’s right to exist and the significant support it enjoys among Palestinians, the best way to advance the two-state solution would have been to leave Hamas with its political and military power – its missiles, rockets, tunnels, and so forth – allowing it to reap the full fruits of its October 7 success. In my view, a peaceful solution to the Palestinian problem can only happen if Hamas is removed from the equation.

McMahan also seems to underestimate the threat posed to Israel by Hezbollah and Iran. In his view, refraining from war would not have increased the danger Israel faces from the north. Contrary to that, in my view, Hamas not facing severe consequences with its October 7 attack would have incentivized Hezbollah to become more aggressive and to pursue its role in the shared goal of destroying Israel.

McMahan seems to believe that if Israel had taken the required defensive steps after October 7, the threat from Hamas wouldn’t have been that bad. But the scale and savagery of the October 7 attacks made it clear that Hamas was serious in its threats to annihilate Israel and commit genocidal acts against its residents. Further evidence of Hamas’s intent came from documents captured in Gaza during the war, which deserve close reading (Rosset 2025). Hence, with all probability, Hamas, with the aid of Hezbollah, the Iranians and the Huthies, would have made life in Israel unbearable had Israel avoided going to war.

Finally, the threat to Israel by Hamas and its allies was much more severe than that posed to Ukraine by Russia, which was mainly to its territorial integrity, not to the very lives of Ukrainians and to their basic human rights. The casualties in Ukraine’s war have also been much higher than those in the Gaza war. Hence, to conclude, if McMahan supports the former war, I can’t see how he can object to the latter.

Acknowledgments

For helpful comments on earlier drafts I’m indebted to Steve de-Wijze, Azar Gat, Iddo Landau, and Saul Smilansky. Thanks also for Rotem Cohen for his excellent research assistance. I completed this paper during my stay at the Center for Ethics in Zurich in March 2025, and I am deeply grateful for its generous hospitality.

References

Abu Amer, Adnan. 2021. “Postponed Palestinian Elections: Causes and Repercussions.” Sada. May 11.Suche in Google Scholar

Alavi, Seyed. 2019. Iran and Palestine: Past, Present, Future. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.10.4324/9780429277078Suche in Google Scholar

Altman, D. 2015. “The Strategist’s Curse: A Theory of False Optimism as a Cause of War.” Security Studies 24: 284–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2015.1038186.Suche in Google Scholar

Bateman, Tom, and Jaroslav Lukiv. 2025. “US Expects ‘Substantial Progress’ in Peace Talks with Ukraine.” BBC News. March 10.Suche in Google Scholar

Bazargan, Saba. 2022. “War Ethics and Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine.” Daily Nous. March 2, 2022.Suche in Google Scholar

Bellamy, Daniel. 2024. “Russia’s New War Tactic: Hiding Deadly Drones in Swarms of Decoys.” Euronews. November 16.Suche in Google Scholar

Benbaji, Yitzhak, and Daniel Statman. 2019. War by Agreement: A Contractarian Ethics of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199577194.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Chenoweth, Erica, and Maria J. Stephan. 2014. “Drop Your Weapons: When and Why Civil Resistance Works.” Foreign Affairs 93: 94–106.Suche in Google Scholar

Fabian, Emanuel. 2025. “Terrorists Took Kfar Aza in an Hour, Recapturing it Took the IDF Days, Probe Finds.” The Times of Israel. March 3.Suche in Google Scholar

Flyvbjerg, Bent. 2021. “Top Ten Behavioral Biases in Project Management: An Overview.” Project Management Journal 52 (6): 531–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/87569728211049046.Suche in Google Scholar

Greene, Joshua D. 2016. “Solving the Trolley Problem.” In A Companion to Experimental Philosophy, edited by Wesley Buckwalter, and Justin Sytsma, 173–89. Chichester: Blackwell.10.1002/9781118661666.ch11Suche in Google Scholar

Hroub, Khaled. 2017. “A Newer Hamas? the Revised Charter.” Journal of Palestine Studies 46: 100–11. https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2017.46.4.100.Suche in Google Scholar

Hurka, Thomas. 2007. “Liability and Just Cause.” Ethics and International Affairs 21: 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7093.2007.00070.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Hurka, Thomas. 2010. “The Consequences of War.” In Ethics and Humanity: Themes from the Philosophy of Jonathan Glover, edited by A. Davis, R. Keshem, and J. McMahan, 23–43. Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195325195.003.0002Suche in Google Scholar

Jahjouh, Mohammad, Jack Jeffery, and Kareem Chehayeb. 2024. “How an Israeli Raid Freed 4 Hostages and Killed at Least 274 Palestinians in Gaza.” AP News. June 10, 2024.Suche in Google Scholar

Kottasová, Ivana. 2024. “Deadly Drone Attack by Hezbollah Exposes Israel’s Weaknesses.” CNN. October 10.Suche in Google Scholar

Lazar, Seth. 2010. “The Responsibility Dilemma for Killing in War: A Review Essay.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 38: 180–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1088-4963.2010.01182.x.Suche in Google Scholar

McMahan, Jeff. 2006. “Morality, Law, and the Relation between Jus Ad Bellum and Jus in Bello.” Proceedings of the ASIL Annual Meeting 100: 112–4. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272503700023995.Suche in Google Scholar

McMahan, Jeff. 2009a. “Intention, Permissibility, Terrorism, and War.” Philosophical Perspectives 23: 345–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1520-8583.2009.00175.x.Suche in Google Scholar

McMahan, Jeff. 2009b. “The Morality of Military Occupation.” The Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review 31: 101–23.Suche in Google Scholar

McMahan, Jeff. 2011. “Proportionality in the Afghanistan War.” Ethics and International Affairs 25: 143–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0892679411000153.Suche in Google Scholar

McMahan, Jeff. 2013. “The Moral Responsibility of Volunteer Soldiers.” Boston Globe. October 28, 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

McMahan, Jeff. 2015. “Proportionality and Time.” Ethics 125: 696–719. https://doi.org/10.1086/679557.Suche in Google Scholar

McMahan, Jeff. 2017. “Proportionate Defense.” In Weighing Lives in War, edited by J. Ohlin, L. May, and C. Finkelstein, 131–54. Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

McMahan, Jeff. 2024a. “Proportionality and Necessity in Israel’s Invasion of Gaza, 2023–2024.” Analyse & Kritik 46: 387–407. https://doi.org/10.1515/auk-2024-2024.Suche in Google Scholar

McMahan, Jeff. 2024b. “Just War Theory and the Russia-Ukraine War.” Studia Philosophica Estonica: 54–67. https://doi.org/10.12697/spe.2024.17.06.Suche in Google Scholar

Miller, Seumas. 2016. “Social Ontology and War.” In A Companion to Applied Philosophy, edited by Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen, Kimberley Brownlee, and David Coady, 196–210. John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Norman, Richard. 1995. Ethics, Killing and War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511554568Suche in Google Scholar

Pancevski, Bojan. 2024. “One Million Are Now Dead or Injured in the Russia-Ukraine War.” The Wall Street Journal.Suche in Google Scholar

Rasgon, Adam. 2025. “Hamas Official Expresses Reservations about Oct. 7 Attack on Israel.” New York Times. Feb 24.Suche in Google Scholar

Rigdon, Renee, and Amy O’Kruk. 2023. “Maps Show the Extreme Population Density in Gaza.” CNN. October 11.Suche in Google Scholar

Rodin, David. 2002. War and Self-Defense. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/0199257744.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Rosset, Uri. 2025. “Hamas’ Strategy to Destroy Israel: From Theory into Practice as Seen in Captured Documents.” The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center. March 13.Suche in Google Scholar

Seifert, Lukas. 2023. “Conversation with Jeff McMahan.” Oxford Student. November 11.Suche in Google Scholar

Smilansky, Saul. 2013. “Why Moral Paradoxes Matter? ‘Teflon Immorality’ and the Perversity of Life.” Philosophical Studies 165: 229–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-012-9952-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Statman, Daniel. 2006a. “Moral Tragedies, Supreme Emergencies and National-Defense.” Journal of Applied Philosophy 23: 311–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5930.2006.00337.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Statman, Daniel. 2006b. “Supreme Emergencies Revisited.” Ethics 117: 58–79.10.1086/508037Suche in Google Scholar

Statman, Daniel. 2011. “Can Wars Be Fought Justly? the Necessity Condition Put to the Test.” Journal of Moral Philosophy 8: 435–51. https://doi.org/10.1163/174552411x591357.Suche in Google Scholar

Statman, Daniel. Forthcoming. “The Limited Reach of Ad Bellum Proportionality.” Journal of Military Ethics.Suche in Google Scholar

Statman, Daniel, Raanan Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Micha Mandel, Michael Skerker, and Stephen de Wijze. 2020. “Unreliable Protection: An Experimental Study of Experts’ in Bello Proportionality Decisions.” EJIL 31: 429–53.10.1093/ejil/chaa039Suche in Google Scholar

van Brugen, Isabel. 2023. “Russian Public Approval of Ukraine War Dropping Rapidly: Survey.” Newsweek. July 22.Suche in Google Scholar

de Wijze, Stephen, Daniel Statman, and Raanan Sulitzeanu-Kenan. 2022. “In Bello Proportionality: Philosophical Reflections on a Disturbing Empirical Study.” Journal of Military Ethics 21 (2): 116–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15027570.2022.2131104.Suche in Google Scholar

Zinman, Truman. 2023. “Hamas Is ISIS.” Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. October 31.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial: Work and Democracy in Conflict

- Focus:Work and Democracy in Conflict

- Political Spillovers of Worker Representation: With or Without Workplace Democracy?

- Workplaces as Schools of Democratic Resilience? Conceptual Considerations About the Spillover Effect

- Challenging Democratic Deficit at Work Through Humoristic Criticism: Perspectives from Turkey’s Highly Qualified Employees

- Workplace Democracy Democratized: The Case for Participative and Elected Management

- Mondragon Cooperatives and the Utopian Legacy: Economic Democracy in Global Capitalism

- Plural Cooperativism. The Material Basis of Democratic Corporate Governance

- General Part

- Between Hermeneutics and Systematicity: The Habermasian Method of Theorizing

- Discussion

- McMahan on the War Against Hamas

- A Reply to Statman’s Defense of Israel’s War in Gaza

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial: Work and Democracy in Conflict

- Focus:Work and Democracy in Conflict

- Political Spillovers of Worker Representation: With or Without Workplace Democracy?

- Workplaces as Schools of Democratic Resilience? Conceptual Considerations About the Spillover Effect

- Challenging Democratic Deficit at Work Through Humoristic Criticism: Perspectives from Turkey’s Highly Qualified Employees

- Workplace Democracy Democratized: The Case for Participative and Elected Management

- Mondragon Cooperatives and the Utopian Legacy: Economic Democracy in Global Capitalism

- Plural Cooperativism. The Material Basis of Democratic Corporate Governance

- General Part

- Between Hermeneutics and Systematicity: The Habermasian Method of Theorizing

- Discussion

- McMahan on the War Against Hamas

- A Reply to Statman’s Defense of Israel’s War in Gaza