Abstract

This paper integrates intercultural learning theory with Japanese historical methods to examine kibyōshi, comic picture books, as cultural texts that illuminate representations of women in Edo print culture during the transitional period from the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century. Rather than reconstructing daily life, it introduces the Intercultural Historical Competence (IHC) model, adapted for Japanese studies, to analyze how gender roles were imagined, negotiated, and circulated through mass publishing. IHC positions kibyōshi as interpretive lenses that open perspectives on Edo-period values while encouraging present-day global reflection on cultural and temporal difference. Through this approach, the study reassesses women’s visibility in Edo society and demonstrates how a short-lived popular genre can function as historical evidence and as a resource for teaching.

1 Introduction[1]

The late mid-Edo period (1770–1810) was a time of rapid cultural, economic, political, and social change in Japan. Among the many forms of popular publishing that thrived in this period, kibyōshi (comic satirical illustrated books with yellow covers) enjoyed a brief but remarkable boom. Combining witty prose with striking images, they captured shifting tastes in urban society and represented the everyday concerns of common readers.

This study uses these picture books as sources to explore how women were represented in Edo’s popular print culture. This paper, however, does not attempt to reconstruct the everyday lives of Edo-period women, which varied greatly depending on class, region, and circumstance. Instead, it focuses on how urban commoner women were depicted in kibyōshi and how such portrayals reflected broader cultural debates. Here, kibyōshi are treated as cultural texts that illuminate not daily life itself but how reality was perceived, caricatured, and communicated within Edo’s urban society.

Such an approach is both timely and necessary given the current state of research. Scholarship on Edo literature has often emphasized elite circles, particularly the samurai and aristocracy, while the intellectual non-elite groups’ cultural experiences remain unexplored. Richard Rubinger has shown that literacy in Tokugawa Japan must be understood as a spectrum of practices shaped by region, class, and gender.[2] Adam L. Kern’s foundational study demonstrated how kibyōshi combined entertainment with cultural critique and laid the groundwork for English translations.[3] Laura Moretti and Satō Yukiko’s edited volume situates kusazōshi within the broader world of early modern graphic narratives.[4] At the same time, Peter Kornicki and Gaye Rowley highlight the importance of women as readers in Edo’s print culture.[5]

Building on these perspectives, this paper introduces the Intercultural Historical Competence framework (IHC), hereafter referred to as IHC, as a method applied within Japanese studies to analyze how kibyōshi represented Edo urban commoner women. Rather than empathizing literally with past actors, IHC uses historical sources as prompts for reflection on cultural codes and representation. The strength of this approach lies in connecting research with education. By framing kibyōshi as depictions that reflect Edo-period perspectives rather than literary records, IHC provides a model accessible to non-specialists and allows readers with no or limited background in Japanese studies to engage with Edo texts as cultural windows.

What is original in this study is not simply the use of historical texts for teaching, which has long been done, but the reframing of kibyōshi as intercultural partners across time. This approach adapts intercultural learning tools to historical analysis, offering new ways to interpret Edo culture while also making it accessible to diverse modern audiences.

The historical context sharpens this inquiry. The Kansei Reforms (1787–1793), initiated under Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759–1829), imposed fiscal austerity, reinforced Neo-Confucian orthodoxy, and tightened censorship. At the same time, the moral philosophy of Shingaku (“Heart Learning”)[6] spread widely among merchants and townspeople, reaching both women and men. Within this regulation and ethical instruction environment, kibyōshi offered a playful yet pointed medium for representing commoner values, anxieties, and aspirations.

The following sections review scholarship on women’s education and print culture, outline the IHC methodology, situate kibyōshi within their broader historical setting, and analyze selected texts and images to demonstrate how women’s roles were represented in these debates.

2 Research History

The study of women’s education, literacy, and engagement with literature during the Edo period (1603–1868) has evolved significantly over the past few decades. Existing scholarship concentrated on elite, male-centered perspectives, particularly those of the samurai, while the experiences of women, children, and townspeople received little attention. Because sources on these groups are often fragmentary, researchers have had to devise innovative approaches to reconstruct their intellectual and social presence. Recent studies have begun to highlight women’s active roles in Edo’s cultural life, yet significant gaps remain, especially concerning their contributions and how they were perceived within society.

In earlier research, I analyzed primary sources, including kibyōshi, alongside official texts and decrees to uncover societal attitudes toward socio-political issues such as pregnancy and childbirth in late 18th-century Japan.[7] This study focused on the politician Matsudaira Sadanobu’s efforts to reduce mabiki (infanticide), revealing how the socio-political context of the Tokugawa shogunate influenced common people’s views on childbirth and the fetus. While this research provided valuable insights into public perceptions and literary reflections, it was limited by a traditional literary-historical approach, focusing on kibyōshi as humorous sides rather than as tools for understanding broader cultural narratives or the perspectives of non-elite readers.

As background to this paper, Kornicki highlights how women, particularly commoners, often acquired literacy informally at home due to limited formal education.[8] The emergence of books targeted at female readers further illustrates the commercial recognition of their reading habits. Likewise, Itasaka Noriko’s analysis of ukiyo-e art shows a shift in depictions of women readers, from idealized portrayals to more realistic images of urban life, underscoring their increasing intellectual presence.[9] Marcia Yonemoto’s work also illuminates women’s roles in literary genres, revealing their participation in intellectual discourse beyond mere entertainment.[10]

Recent English-language scholarship on Edo women has centered on biography. As Simon Partner observes, studies by Anne Walthall,[11] Laura Nenzi,[12] Bettina Gramlich-Oka,[13] and Amy Stanley[14] recover the lives of “mid-level” women through diaries, letters, and poetry, stressing their agency despite social constraints. By contrast, Japanese scholarship has compiled wider corpora, yet commoner women remain difficult to approach directly.[15] This study makes use of kibyōshi as mass cultural texts to get closer to these groups, showing how women’s presence was imagined, circulated, and negotiated within Edo print culture. Through IHC, kibyōshi become a bridge toward audiences whose lives rarely left autobiographical traces.

Women’s roles as educators also merit attention. Sugano Noriko shows that female teachers (onna shishō) in terakoya[16] were instrumental in spreading literacy and countering assumptions that women occupied only marginal educational positions,[17] a point examined further in Section IV.

The trajectory of kibyōshi scholarship itself is also essential to note. Meiji-era critics dismissed kibyōshi as trivial works, a judgment shaped by their satirical tone and by the censorship legacy of the Kansei Reforms.[18] In the 1980s, Nakamura Yoshihiko highlighted the complexity of gesaku literature and called attention to the undervaluation of kibyōshi.[19] At the same time, Inoue Takaaki urged a reconsideration of their literary techniques and cultural role.[20] Building on this momentum, Tanahashi Masahiro undertook the monumental task of cataloging and analyzing all extant kibyōshi, producing indispensable bibliographic and interpretive foundations.[21] More recent scholarship has further re-situated kibyōshi within their late Edo milieu, recognizing them as sophisticated cultural products that engaged with social and intellectual concerns. Among others, Kern has internationally emphasized the genre’s multifaceted character.[22]

Suzuki Toshiyuki notes that kibyōshi, sold alongside popular ukiyo-e prints, spread widely across Japan by the late eighteenth century because of their affordability.[23] By the early nineteenth century, the publishing industry had further diversified into genres such as sharebon,[24] kokkeibon,[25] and gōkan,[26] circling through the same networks.[27] As Chiyoji Nagatomo has shown, popular fiction in the late Edo period circulated not only through commercial lending libraries but also through networks of personal exchange, especially among women.[28] Taken together with visual sources showing women in relation to books and reading, these developments make it plausible to assume that women formed a larger part of the readership, even if direct evidence remains limited before the 19th century. At the same time, as Kern cautions, the proof of kibyōshi’s readership is fragmentary: catalogs, government documents, and textual clues allow only tentative inferences, and frequent references within the works to “women and children” readers were often rhetorical rather than literal.[29]

This paper builds on these perspectives and on the author’s earlier findings, which juxtaposed, among others, Yoshi no Sōshi (a Kansei-era historical record) with kibyōshi to reconsider how these texts were read and understood at the time.[30]

3 Methodology

In this paper, IHC functions as a practical interpretive method for analyzing kibyōshi as cultural representations and for translating that analysis into higher-education teaching. Previous research has demonstrated the richness of kibyōshi as humor, satire, and social commentary, yet these approaches are often difficult to translate into broader historical or pedagogical practice. IHC addresses this gap by drawing on intercultural learning theory, including Kenneth Nordgren and Maria Johansson’s framework of intercultural historical learning,[31] and by incorporating UNESCO’s model of dialogue across cultures alongside Japanese literary–historical methods.[32]

The initial inspiration for this model came from a 2023 workshop on Story Circles,[33] a method for developing intercultural competencies.[34] That experience prompted me to consider how dialogic listening might extend beyond contemporary settings to create encounters between past and present actors. From this starting point, I began shaping an approach that adapts intercultural methods into historical analysis.

In developing this approach, I later encountered Kenneth Nordgren and Maria Johansson’s framework of intercultural historical learning. Their model, structured as a nine-cell matrix for school history, differs from my own in scope and application.[35] While their model emphasizes curriculum design in general history education, I adapt a similar concept more narrowly within Japanese studies, using it to analyze kibyōshi (and related genres) and reflect on their reinterpretation in scholarship and higher-education teaching.

I refer to this approach as Intercultural Historical Competence (IHC). It is an applied method that reads kibyōshi as cultural representations and frames them as opportunities for reflection on the cultural difference between Edo-period commoners and modern readers, whether in research or in teaching contexts. In other words, IHC is not a general theory, but a practical framework that interprets Edo texts as intercultural encounters and makes them usable for both scholarship and pedagogy.

IHC can be applied in four stages, outlined below. In this paper, I focus on Stage 2 in Section IV and Stage 3 in Section V.

Stage 1. Humor in Context (Background, Already Established)

The humor of kibyōshi emerges from the interplay of text and image, where authors adopt a teasing, playful, and at times mocking stance that remains anchored in recognizable realities. It should not be reduced to kokkei in the later sense of absurd or farcical humor, nor equated with Western-style fūshi (satire) or straightforward critique. Instead, kibyōshi laughter occupies a distinctive register that blends comic exaggeration with realistic detail.[36] Reading these works within their historical setting preserves this layered quality while enabling modern audiences to approach them through translation and interpretation.[37]

Stage 2. Comparative Framing

Kibyōshi are examined alongside other sources, including government proclamations (machibure), terakoya records, ōraimono (letter-format textbooks), and ukiyo-e prints, so that they can be situated within a broader intellectual and social landscape. This comparative approach clarifies how kibyōshi participated in debates on education, morality, and popular culture, rather than being read as isolated literary texts.

Stage 3. Cultural Reflection

Drawing on contextualization and comparison, the study considers how depictions of women, as readers, educators, or cultural participants, might have been received by contemporaries. It emphasizes kibyōshi as sites of negotiation between social constraints and commoner creativity, balancing amusement with cultural critique.

Stage 4. Pedagogical Application (Beyond the Scope of This Paper)

Although this paper focuses on historical analysis, the IHC model has been piloted in classroom contexts outside Japanese literary or historical studies. In my English-medium classes at the University of Osaka, students from diverse backgrounds, differing in academic field, nationality, and cultural experience, create short video projects in English that connect Edo-period themes drawn from kibyōshi with contemporary issues. In these activities, the texts function as intercultural partners rather than historical evidence, prompting reflection across lines of discipline and culture. This shows that IHC is a method for interpreting Edo print culture and a transferable framework that links historical sources to modern global concerns and adapts across fields.[38]

By focusing on Stages 2 and 3, this paper shows how educators can make complex sources accessible for discussion and broader application, even for students and readers whose academic fields are not directly related to Edo-period history, literature, or kibyōshi. The aim is not to reconstruct Edo life in detail but to use these texts to reveal cultural perspectives and situate them within comparative contexts. Interpretations presented here should be read as cultural representations, not factual records.

IHC repositions kibyōshi from a cold literary corpus to a medium that was always playful and interactive. The researcher–educator mediates this encounter, guiding reflection on values, humor, and social roles. When modern audiences meet these texts, the dialogue unfolds much like an intercultural exchange, where surprise and difference provoke new insights. This approach complements philological traditions[39] by preserving the accessibility that once made kibyōshi legible to Edo citizens.

Why is IHC important? It reframes kibyōshi from niche literary curiosities into cultural partners that can still speak across time. This shift matters not only for teaching but also for research since making these sources accessible broadens the range of people who can engage with aspects of Edo culture, such as humor, gender, and commoner values.

In this framework, “intercultural” extends across time. IHC treats the Edo population as one cultural group and modern readers as another, using kibyōshi as a medium of encounter. Since today’s readers are diverse, Japanese and non-Japanese, specialists and non-specialists, interpretations inevitably differ just as Edo readings themselves always varied (see Section V for details). A clear example is the term fūshi, which in Edo meant witty humor, not “satire” as redefined through Meiji scholarship and global exchange. Recognizing such shifts and differences and analyzing them is part of the intercultural work of IHC.

For readers without access to Edo texts in the original, IHC offers a way to experience them not as inaccessible objects of the past or only through heavy translation, but as aids in reflection. In this way, the framework links research and teaching, bridging past and present, Japanese contexts and global perspectives.

4 Women’s Education and Literacy in Mid- and Late Edo Society

This section develops the IHC stage 2 of Comparative Framing by placing kibyōshi depictions of women alongside evidence from terakoya records, ōraimono, and visual sources, situating them within Edo’s wider intellectual and social landscape.

4.1 The Terakoya System and Women Teachers

The terakoya system, developed during the Edo period, was one of Japan’s most influential grassroots educational practices. Their numbers grew steadily from the late eighteenth century and, by the Meiji Restoration in 1868, are estimated to have exceeded 15,000,[40] though many were privately run and not systematically recorded.

Women played a significant role in this system as both learners and teachers. Nagata notes that as the shogunate stabilized in the late seventeenth century, women increasingly pursued personal interests through literacy, including practical texts on medicine, child-rearing, and household management. By the early nineteenth century, one in three terakoya teachers in Edo was a woman, often well-educated and sometimes recognized as poets.[41] Sugano further emphasizes that these instructors in early 19th-century Edo not only taught reading and writing but also offered practical skills such as household management and etiquette, shaping the knowledge of future generations.[42] Their presence marked a shift in Edo society’s perception of women’s literacy and its importance to everyday life.

In urban centers like Edo, female teachers played a crucial role in educating boys and girls alike. Figure 1, Bungaku Bandai no Takara (“The Timeless Treasures of Literature,” 1844–1848), depicts a female teacher (left), visually underscoring women’s central role in foundational education in the late Edo period.

Bungaku Bandai no Takara (1844–1848, ukiyo-e, Issunshi Hanasato). Source: Tokyo Metropolitan Library.

4.2 The Emergence of Female Readers in the Late 1700s and Early 1800s

As terakoya schools expanded, literacy rates among women, particularly in urban areas, began to rise. Nagata estimates that by the mid-19th century, approximately 40 percent of boys and 10 percent of girls attended terakoya, especially in urban centers.[43] This figure should not be read as universal, since opportunities varied significantly across regions and classes. Even limited literacy opened new possibilities: women read guides, moral treatises, and fiction, and publishers recognized them as part of the expanding reading public.

Among the foreign testimonies surveyed by Richard Rubinger, the most relevant to this era is that of the Russian captain Vasilii Golovnin (1776–1831), who spent over two years in captivity in Japan between 1811 and 1813. Even during his confinement, he praised Japan’s literacy, remarking that “in comparison with other nations, the Japanese are the most educated people in the world. In Japan, not a single person is unable to read and write.”[44]

Works such as Onna Daigaku (“Greater Learning for Women”) and Onna Shōbai Ōrai (“Women’s Trade Letters”), belonging to the genre of ōraimono, encouraged both literacy and moral cultivation. Beyond didactic instruction, these texts often functioned as practical handbooks, offering models for everyday correspondence and guidance on etiquette, commerce, and household management. As Amano has shown, women’s ōraimono developed into “comprehensive life textbooks,” blending moral lessons with the concrete skills needed in social and economic life.[45] Exhibitions of Edo-period materials further reveal how such manuals were used alongside illustrated sugoroku[46] and other playful media, demonstrating that children and women alike engaged with these texts in ways that blurred the boundaries between learning and entertainment.[47]

Visual sources also highlight women’s visibility in Edo’s literary world. Edo Meisho Zue (“Illustrated Guide to Famous Places in Edo” 1834–1836, Figure 2) depicts women browsing bookshops, suggesting that female literacy was increasingly recognized in urban society.

![Figure 2:

Edo Meisho Zue (Saitō Chōshū, [1834–1836]), Volume 7. Page 60 (verso), 61 (recto). Source: National Diet Library (NDL) Online.](/document/doi/10.1515/asia-2024-0026/asset/graphic/j_asia-2024-0026_fig_002.jpg)

Edo Meisho Zue (Saitō Chōshū, [1834–1836]), Volume 7. Page 60 (verso), 61 (recto). Source: National Diet Library (NDL) Online.

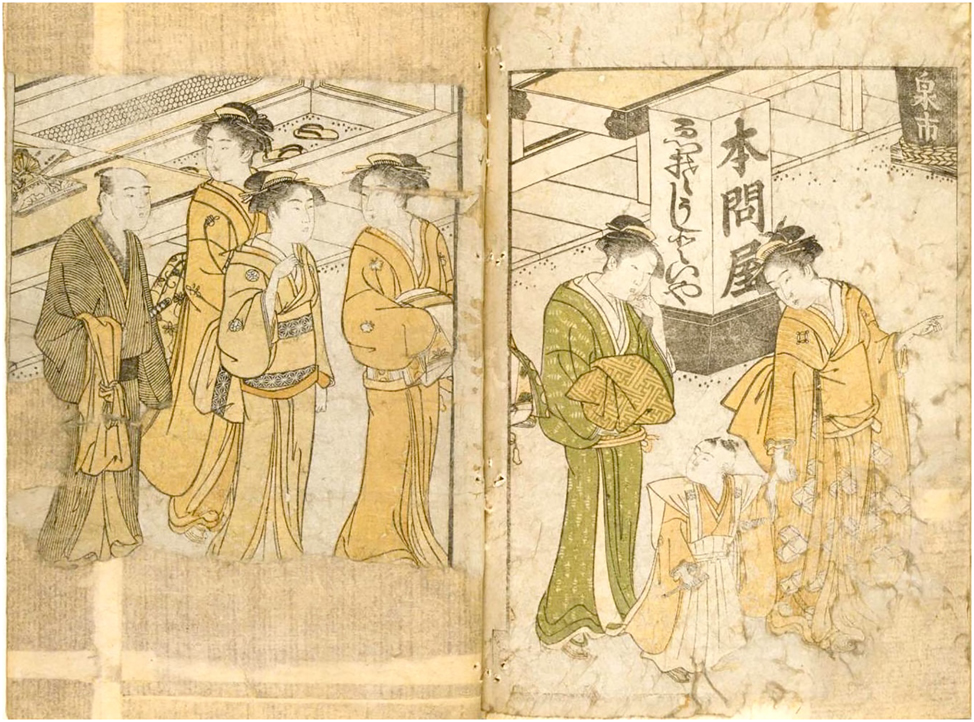

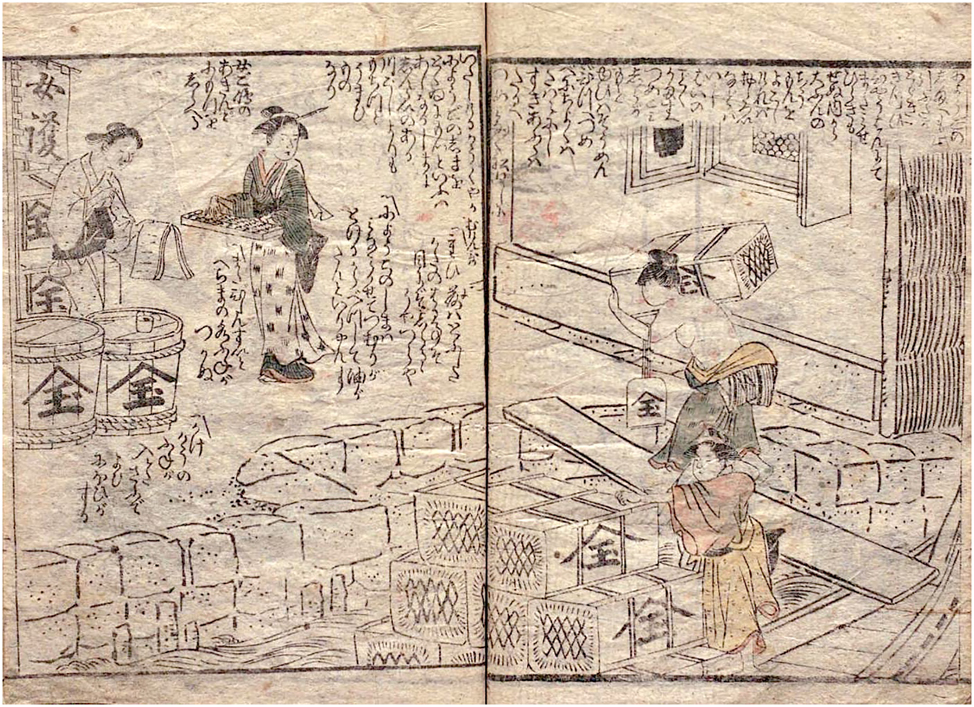

Ehon Sakae Gusa (“Picture Book: Prosperity of the Family”, 1790, Figure 3) offers a related image of women outside a book wholesaler (jihon ton’ya). This scene should be read less as documentation of practice than as evidence of how publishers represented women within the expanding world of print commerce.

Ehon Sakae Gusa (1790, Katsukawa Shunchō), Volume 1, Page 3 (verso), 3 (recto).Source: National Diet Library (NDL) Online.

Another scene from the same work (Figure 4) shifts the focus to education, showing a female teacher instructing children in a terakoya while carrying her child on her back. This depiction underscores the role of women as educators during the Kansei Reforms and illustrates how literacy was imagined as integral to household and community life.

Ehon Sakae Gusa (1790, Katsukawa Shunchō), Volume 2, Page 8 (verso), 8 (recto). Source: National Diet Library (NDL) Online.

These sources suggest that women’s literacy was recognized and, at times, promoted in Edo society. They reflect not only reading and teaching practices but also the cultural imagination of women as participants in urban print culture.

An illuminating case, and perhaps the closest real-life example to the female readers of the period, is Michi (1797–1835), Kyokutei Bakin’s[48] daughter-in-law, who completed Nansō Satomi Hakkenden (“The Eight Dog Chronicles”) after he lost his sight. In the postscript, Bakin admitted that “as a woman, she scarcely knew even common characters, had no knowledge of literary Chinese or classical Japanese, and did not understand kana usage or particles, nor even the radicals of Chinese characters.”[49] This passage indicates that Bakin did not suggest Michi was illiterate; rather, he emphasized that her level of training was inadequate for the demands of extended literary composition. As Itasaka Noriko shows from analyzing her diary, Michi later developed into a competent writer whose square hand, rich in Chinese characters, recalled classical prose.[50] Her story highlights both the constraints and the unexpected possibilities of female literacy in late Edo society.

5 Women’s Intellectual Engagement through Kibyōshi

Building on this broader literacy environment, kibyōshi experimented with women’s imagery in satirical and commercial contexts. These texts portrayed women as courtesans, bookbinders, or shopkeepers, extending beyond recognition to active cultural participation in print. Here, the analysis moves into the IHC stage 3 of Cultural Reflection, considering how depictions of women in kibyōshi might have been received by contemporaries and what cultural negotiations they reveal.

5.1 The Intersection of the Kansei Reforms, Shingaku Philosophy, and Kibyōshi Readership

The rise in female readership coincided with the Kansei Reforms, which sought to regulate public morals and expand education. While rooted in Confucian ideals designed to reinforce social hierarchy, these reforms also drew on Shingaku, a merchant philosophy stressing frugality and discipline. Takenaka Yasukazu notes that Shingaku extended its reach beyond commoners to the daimyō class under Matsudaira Sadanobu, who actively supported its principles.[51]

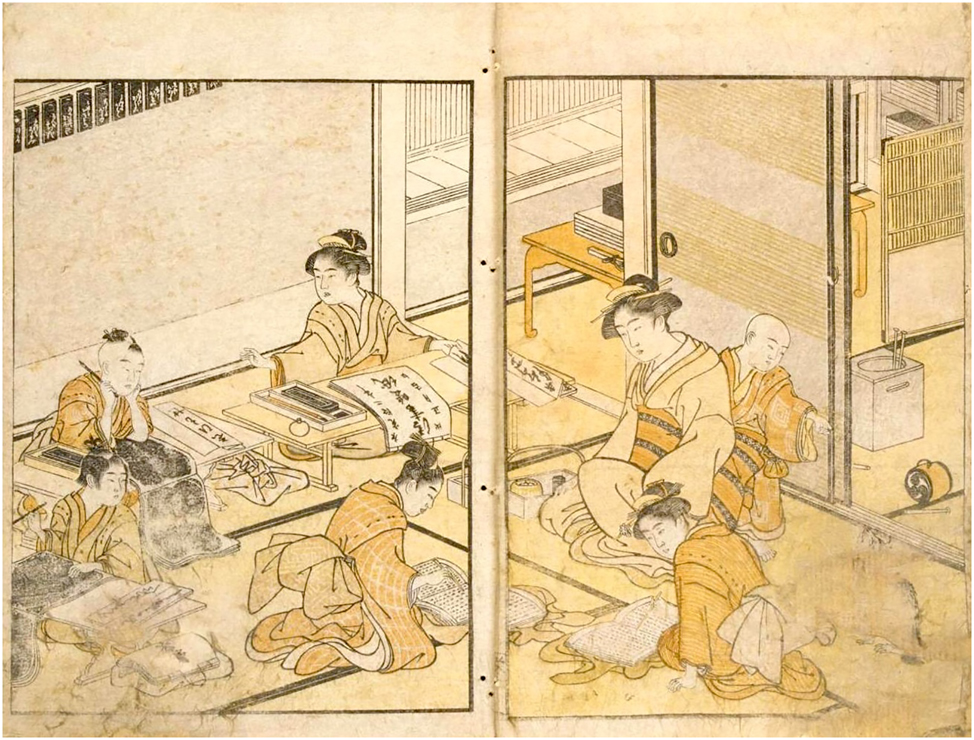

Shingaku lectures were depicted as attracting broad audiences, including men, women, and children, as seen in illustrations such as Zenkun Chōmon no Zu (“Illustration of an Audience for Zenkun”, Tejima Toan, 1778, Figure 5). These sessions often featured simplified teachings, moral songs, and relatable stories, suggesting that the philosophy was presented in a way that could be accessible beyond male circles. While these depictions do not reflect actual patterns of attendance, they illustrate how Shingaku was imagined as a more inclusive and accessible platform. This representational openness offers insight into the cultural environment in which kibyōshi were produced and circulated.

Zenkun Chōmon no Zu (“Illustration of an Audience for Zenkun”), from Zenkun (2 vols. , Tejima Doan 1778). Source: National Diet Library (NDL) Online.

However, official education remained primarily for men. Law edicts from 1791 illustrate how the shogunate aligned its policies with the Confucian ideals of the Kansei Reforms, focusing on training male officials and their dependents.[52] Regulations emphasized structured academic examinations, martial and artistic training, and meticulous recordkeeping of students, instructors, and their lineages.

At the same time, urban proclamations regulated the production of shomotsu[53] and kusazōshi,[54] banning erotic works and criticizing the rising costs of illustrated books. In particular, they targeted works that posed as children’s picture books, such as kibyōshi, denouncing them as frivolous diversions.[55]

Likewise, archival material from the Edo magistrates’ office (Edo machibugyō) and the booksellers’ guild (hon’ya nakama) records restrictions against “immoral heterodox teachings, ephemeral gossip, and works harmful to the morals of men and women.” [56] Such edicts were posted or circulated publicly, forming part of the textual environment that women, along with men and children, would likely have encountered. The absence of women from formal schooling regulations yet simultaneous presence in the everyday textual landscape is mirrored in kibyōshi illustrations, such as Ōmu Gaeshi Bunbu no Futamichi (“Parroting Back: The Two Paths of Literary and Military Arts,” 1789, 13 verso, 13 recto), which depicts a lecture at the Yushima Seidō[57] without including women as participants, even as they appear elsewhere in the same work, subjected to hostile remarks from “overeducated” samurai who misapplied the reforms.[58]

5.2 Women’s Engagement with Kibyōshi and Its Broader Impact

Specific examples and marginalia reveal traces of the reader’s engagement with kibyōshi. In earlier work, I analyzed close to one hundred original prints linked to the Kansei Reforms, showing children’s drawings and personal annotations that suggest not only men were among the reader.[59] Additionally, kibyōshi often included advertisements for medicines, cosmetics, and illustrations of fashion trends, subjects that likely resonated with female readers.[60] Written primarily with kana, the texts were accessible to readers with basic literacy skills, which may have included many women and children, though literacy levels varied widely.

Not all readers necessarily grasped the full nuances of kibyōshi; they were nonetheless captivated by its engaging stories and humorous illustrations. These texts often encouraged readers to decode visual and textual clues, fostering shared interpretations and discussions among audiences. For instance, in the concluding scene of Tama Migaku Aoto ga Zeni (“Aoto’s Polished Coin”, 1790, Santō Kyōden[61]), a samurai is ridiculed for his poor fashion sense during a kabuki performance. Both men and women among the townsfolk mock him as a “bat,” referencing his awkward attire, which mimics the haori (a short kimono jacket) style used in military exercises. Such moments encouraged readers to enjoy the joke individually and share interpretations aloud in the company of others. In this way, kibyōshi functioned as a medium of communal engagement, turning reading into a social event.

The Kansei Reforms and the spread of Shingaku shaped the moral and social climate in which these texts circulated. Works such as Shingaku Hayasome Gusa (“Quick-Start Guide to Shingaku,” 1789, Santō Kyōden) integrated Shingaku’s principles into accessible and humorous formats, conveying lessons on self-discipline and thrift in ways that aligned with reformist ideals. While the reforms did not target women’s education, their emphasis on moral cultivation created a cultural atmosphere that publishers could draw upon to broaden their readership.

5.3 Book Sewing Women in Atariyashita Jihon Don’ya

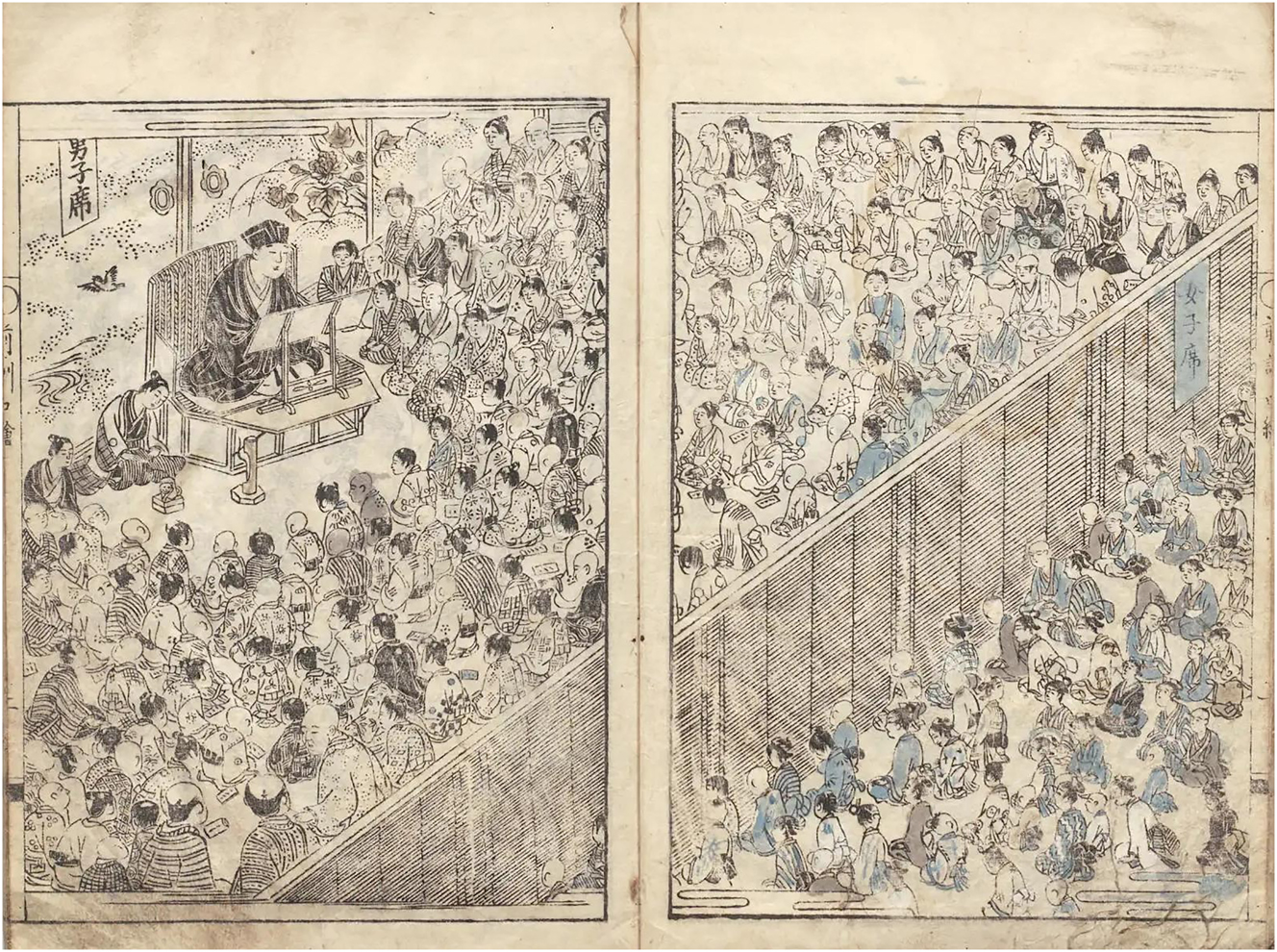

Jippensha Ikku’s[62] Atariyashita Jihon Don’ya (“It’s a Hit! The Local Book Wholesaler”, 1802) humorously depicts the entire book production process in Edo society, from concept to printing and sales. The author and his publisher are featured in a satirical portrayal of the pressures of the literary market and the commercialization of these books.

In Figure 6, women (left) are shown engaged in book sewing while men (right) also work on the books. The narrator jokes about the difficulty of binding, noting that this task was considered women’s work in book production. The scene ends comically when the publisher abandons an impractical idea for solving the problem and instead relies on his daughter, wife, and mother, whose fingers are described as moving “as quickly as their tongues.”

Atariyashita Jihon Donya (Jippensha Ikku, 1802, kibyōshi), Page 8 (recto). Source: National Diet Library (NDL) Online.

At the same time, short lines placed near the women’s figures read as if they were speaking themselves:

Binder Woman 1: “They say it’s fine as it is, nothing more to write or draw here.”

Binder Woman 2: “Oh, come on! This book is just so ‘fascinating’!” (If you don’t mind guessing what’s missing!)[63]

This interplay between the narrator’s commentary and the apparent voices of the characters illustrates how kibyōshi blurred narration and dialogue, prompting readers to interpret text and image together. It also shows how women were imagined as active participants in the world of books, both as laborers and as figures who might remark on content. As seen here, kibyōshi functioned as a playful medium of etoki storytelling, where readers were expected to combine words and pictures and uncover hidden meanings through laughter. Since there were no fixed rules for assigning lines to figures, Edo readers could interpret dialogue differently. Modern annotated editions often assign speech for clarity, but the original prints invited this flexibility. Such interpretive freedom recalls what Kern has described as the “pictorial storytelling” effect, where the narrator seems to improvise commentary around images, creating mismatches that sharp-eyed readers noticed and enjoyed as part of the humor.[64]

The first challenge of using kibyōshi as historical sources is that we will never know exactly how Edo readers interpreted a given page, since no direct evidence survives. We can only sketch a range of possible readings based on existing knowledge, while recognizing the playfulness and ambiguity that gave these texts their force.

The second difficulty lies in their format: not only interpretive ambiguity, but also the complex layout of images and text. As Takasuka Moe and colleagues note, even with recent digital encoding standards such as TEI,[65] questions remain about how best to present these materials to specialists and general users.[66] Digital tools will undoubtedly improve accessibility, but technology alone cannot explain the cultural contexts or the humor and values embedded in these works. Addressing these difficulties is where IHC becomes important: it complements technical access by presenting kibyōshi as intercultural mediators, intelligible not simply as texts to decode but as cultural expressions that reveal the values of their time while inviting dialogue with the present.

5.4 Shifting Literary and Social Roles with Visual Representations of Women’s Literacy

In Edo’s red-light district, high-ranking courtesans (oiran) were expected to be literate and trained in the arts, combining beauty with wit and education. In kibyōshi, their portrayal as readers reinforced their status as cultural icons and broadened the imagined readership to include women.

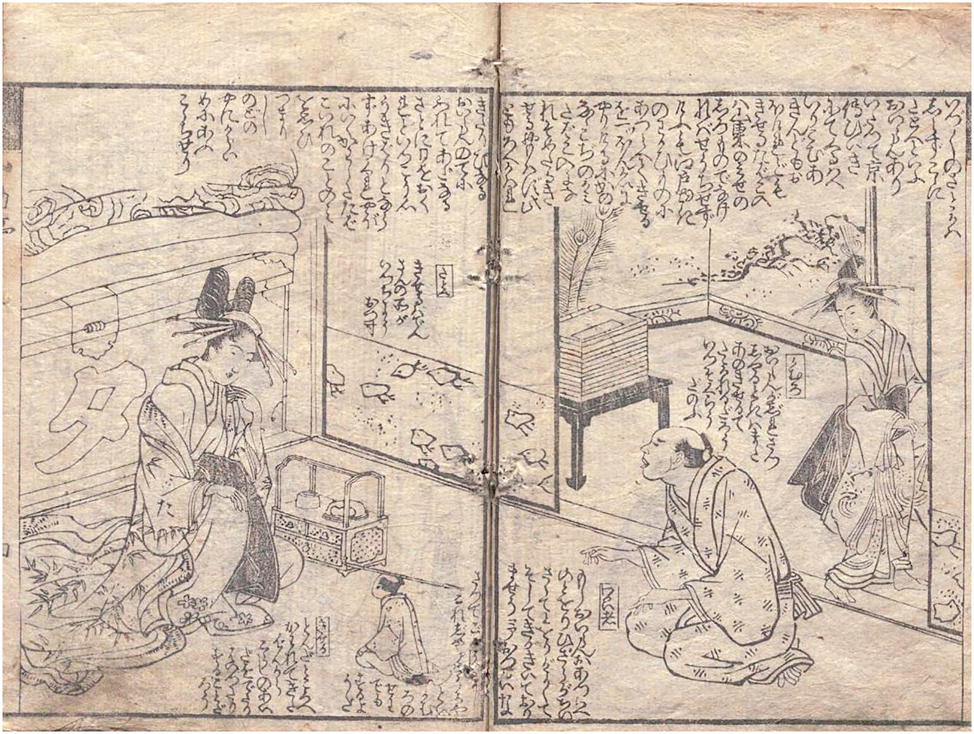

In Figure 7, Kyokutei Ippu Kyōdenchō (“Record of Kyōden by Kyokutei,” 1801) depicts a courtesan in an elegant interior surrounded by stacks of books, presenting her not merely as a fashion icon but as a figure of cultural literacy. Notably, she is drawn much larger than the men in the scene, which is undoubtedly an exaggeration. However, it’s noteworthy that oiran courtesans held a higher social rank than many men in the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters. As cultural trendsetters, courtesans embodied a refinement that extended far beyond clothing and hairstyles to encompass wit, taste, and intellectual sophistication.

Kyokutei Ippu Kyōdenchō (Kyokutei Bakin, 1801, kibyōshi). Page 3 (recto), 4 (verso). Source: National Diet Library (NDL) Online.

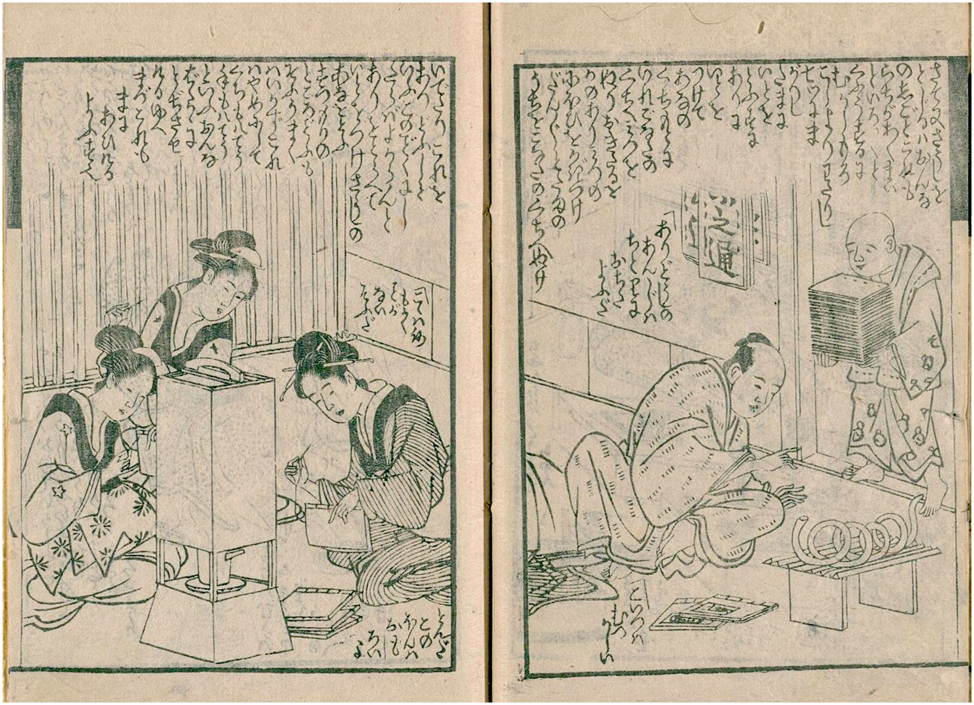

Related genres from the same era also depicted women as icons of cultural refinement. Utagawa Toyokuni’s Ehon’imayō Sugata (“Picture Book of Fashion of the Times,” 1802), an illustrated fashion book, presents idealized urban women reading and writing in elegant domestic settings (Figure 8). Later in the same work, a scene shows a young girl carrying a book beside her mother, while the second volume depicts courtesans engaged in reading. Although not a kibyōshi, this fashion picture book reinforces how female literacy was imagined as part of cultural sophistication and fashionable identity in early nineteenth-century Edo society.

Ehon’imayō Sugata (Picture Book of Fashion of the Times, 1802), Volume 1, Page 5 (recto), 6 (verso). Source: National Diet Library (NDL) Online.

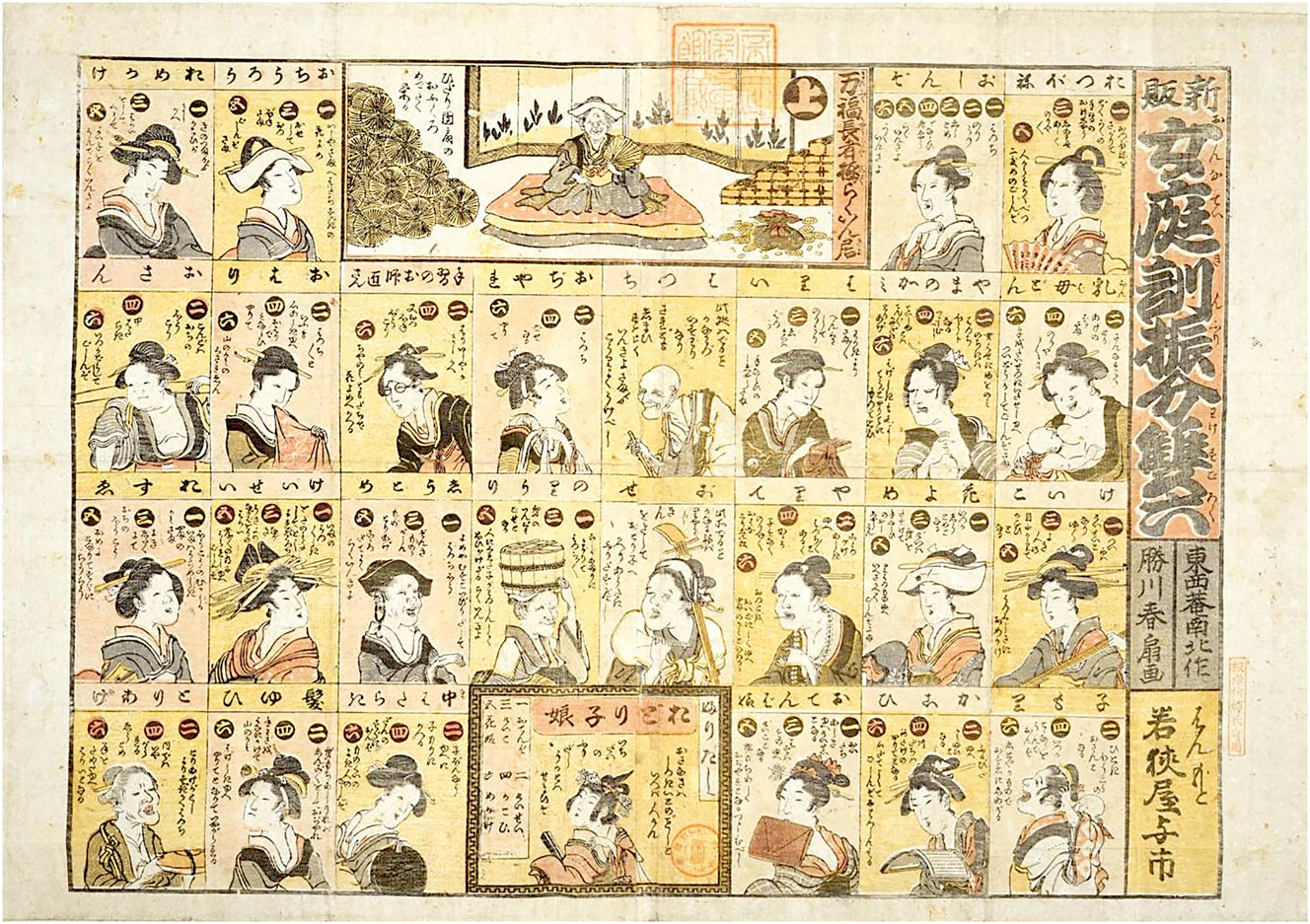

In Onna Masakado Shichinin Keshō (Figure 9, “The Seven Transformations of Woman Masakado,” 1792), women are humorously cast in accounting and trade, while Kyōden’s introduction stages them as voices in the bustle of urban markets. Read against the background of merchant household practices, where women often assumed central roles in management and succession,[67] these depictions can be understood not simply as a parody of men but as a satirical reflection on women who occupied spaces of authority in family economies. In this sense, the humor underscores tensions around gendered expectations, acknowledging women’s active presence while exaggerating it for comic effect.

Onna Masakado Shichinin Keshō (The Seven Transformations of Women Masakado, Santō Kyōden, 1792, kibyōshi), Page 6 (recto), 7 (verso). Source: National Diet Library (NDL) Online.

By contrast, Shinpan Onna Teikin Furiwake Sugoroku (Figure 10, “Newly Published Women’s Moral Education Sugoroku,” early 19th century) presents a more programmatic vision. This illustrated board game charts women’s life paths from youth to retirement, explicitly highlighting reading and commerce, including the abacus, as valued skills. Regarding the use of board games in the late Edo period, Kuroishi notes that “at least until the prewar years in Japan, sugoroku were an intimate part of children’s play, closely tied to their daily lives, and through these games they absorbed a broad range of knowledge and cultural literacy.”[68] Parallels with historical records strengthen this picture: archival sources show women’s active participation in family economies, where wives and daughters routinely contributed to bookkeeping, inventory management, and property oversight. In Edo-period merchant households, it was common to adopt a muko yōshi even when male heirs existed, a striking contrast to the patrilineal succession of warrior families.[69] From this perspective, depictions of women engaged in commerce within kibyōshi are not unusual inventions but reflections of everyday social practices, refracted through humor and cultural imagination.

Shinpan Onna Teikin Furiwake Sugoroku (Newly Published Women’s Moral Education Sugoroku), Katsukawa Shunsen (1805–1821). Source: National Diet Library (NDL) Online.

The presence of women in kibyōshi, whether as characters or as implied readers, reflects how Edo print culture linked women’s literacy to broader societal change. By the late eighteenth century, the genre was already tending toward transformation, and after 1806 it evolved into gōkan, which more directly targeted female audiences. This shift paralleled a broader social phenomenon in which the cultural emphasis on women’s education deepened, especially in urban centers like Edo, where literacy enabled women to participate more actively in intellectual and cultural life.

The examples discussed in IHC Stages 2 and 3 illustrate how kibyōshi can be read in ways that are both historically grounded and broadly accessible. By setting them in comparative context and reflecting on their cultural implications, these stages provide a framework that non-specialist readers can follow, connecting Edo commoners’ perspectives with their own across time and space. This groundwork prepares the way for Stage 4, where the same interpretive process can be extended into pedagogy. Since many students encounter kibyōshi without any prior Japanese history or literature background, the framework is key to providing accessible entry points. In classroom settings, students are then encouraged to apply what they have learned by linking Edo themes with their own contemporary experiences, turning historical analysis into a meaningful intercultural encounter.

6 Conclusions

Humor, satire, and depictions of women in dialogue with contextual sources show how kibyōshi functioned as entertainment and cultural critique. They capture the interplay of commoner values, Shingaku ethics, and the moral climate of the Kansei Reforms. These texts illuminate the symbolic codes through which women’s intellectual presence was imagined, negotiated, and commercialized in Edo’s publishing world.

The four stages of Intercultural Historical Competence (IHC) form a cycle: situating humor within its historical milieu, placing sources in comparative perspective, identifying cultural implications, and extending the method into pedagogy. Although this study has centered on Stages 2 and 3, the framework provides a flexible interpretive approach that links research with instruction and bridges the past with the present, one that can be extended to other groups, genres, and cultural contexts.

What emerges is not simply a new way of reading kibyōshi, but a redefinition of their role: rather than treating the genre as a curiosity or as an illustration of Edo society, we can approach these works as intercultural texts that continue to invite dialogue across time. This method does not replace philological rigor but complements it, ensuring that the interpretive value of kibyōshi can circulate to broader audiences. Acknowledging that interpretation is always subjective, IHC makes this indeterminacy a strength, transforming openness into a resource for reflection across cultures and eras.

Two contributions follow. First, kibyōshi can be mobilized in the classroom even among students with no prior background in Japanese history, serving as a medium through which early modern texts address contemporary concerns. In forthcoming research, this pedagogical direction will extend into AI-based animation, making kibyōshi new and vivid for younger generations and ensuring their humor continues to resonate. The fourth step of IHC, dialogue, becomes central at this stage, building directly on the research background and analysis presented here.

Second, the framework helps recover traces of commoner women in Edo popular print culture, a group often obscured in historical records yet essential for understanding the fabric of urban society. This line of inquiry inevitably raises questions of subjectivity, but it is precisely here that future scholarship must press forward. While the difficulty of decoding and contextualizing kibyōshi will never disappear, with digital tools on one side and intercultural reflection on the other, we can move closer to a mode of scholarship that is at once rigorous, accessible, and culturally reflective.

Funding source: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

Award Identifier / Grant number: Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows

Appendix: Summary of Primary Materials Analyzed

| Material Type | Example | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Kibyōshi | Shingaku Hayasome Gusa (Santō Kyōden, 1789) 心学早染草 | Shingaku’s teachings illustrate the inner conflict between the good self (Zendama) and bad selves (Akudama). Depicts courtesans as educated women capable of writing letters. |

| Kibyōshi | Ōmu Gaeshi Bunbu no Futamichi (Koikawa Harumachi, 1789) 鸚鵡返文武二道 |

It depicts misunderstandings of Kansei-era reforms through Sugawara no Michizane’s promotion of martial and academic values while portraying women being insulted by overtrained men. |

| Kibyōshi | Taiheiki Azumakagami: Tama Migaku Aoto ga Zeni (Santō Kyōden, 1790) 太平記吾妻鑑玉磨青砥銭 | Uses the historical figure Aoto Fujitsuna as a metaphor for Matsudaira Sadanobu, offering a positive political evaluation and tying it to moral teachings.a Depicts commoner men and women mocking a samurai for his fashion sense. |

| Kibyōshi | Onna Masakado Shichinin Keshō (Santō Kyōden, 1792) 女将門七人化粧 | Humorously depicts the bustling activities of an Edo-period shop, highlighting the roles of its workers, women, young assistants, and others, and showcasing women mastering practical skills like using an abacus, reflecting their significant contributions to society. |

| Kibyōshi | Kyokutei Ippu Kyōdenchō (Kyokutei Bakin, 1801) 曲亭一風京伝張 | While also serving as an advertisement for Santō Kyōden’s tobacco shop, it highlights women’s cultural and intellectual aspirations in Edo society. |

| Kibyōshi | Atariyashita Jihon Don’ya (Jippensha Ikku, 1802) 的中地本問屋 | While depicting the entire book production process in Edo society, it highlights women’s contributions to book production and their intellectual engagement. |

| Picture Book | Ehon Sakae Gusa (Katsukawa Shunchō, 1790) 絵本栄家種 | Portrays women’s life stages through colored woodblock prints, depicting their interactions with booksellers and emphasizing their active role in Edo’s literary economy. |

| Picture Book | Ehon’imayō Sugata (Utagawa Toyokuni, 1802) 繪本時世粧 | Illustrates Kansei-era women’s fashions through 24 colored woodblock prints and emphasizes the cultural focus on women’s literacy by portraying them as readers. |

| Yomihon (epic novel) | Nansō Satomi Hakkenden (Kyokutei Bakin, 1814–1842) 南総里見八犬伝 | In the postscript, Bakin admitted that Michi (his daughter-in-law) “scarcely knew even common characters, had no knowledge of literary Chinese or classical Japanese, and did not understand kana usage or particles, nor even the radicals of Chinese characters.” |

| Illustration | Zenkun Chōmon no Zu (前訓聴聞の図, “Illustration of an Audience for Zenkun”), from Zenkun (前訓), by Tejima Toan, 1778. | Depicts a Shingaku lecture setting where male and female children (7–15 years old) are seated in separate areas, emphasizing the lecture’s focus on child education. |

| Ukiyo-e Print | Bungaku Bandai no Takara (Issunshi Hanasato, 1844–1848) 文学ばんだいの宝 | This nishiki-e diptych depicts a terakoya classroom scene, with a male teacher in the first print and a female teacher in the second. While children engage in various antics, playing, fighting, or drawing, some order is maintained, with lessons covering reading, writing, and arts like flower arranging and tea ceremony, highlighting the important role of women as educators in the terakoya system. |

| Game Board | Shinpan Onna Teikin Furiwake Sugoroku (Tōzaian Nanboku, 1805–1821) 新販女庭訓振分双六 | Illustrates women’s societal advancement, with each space representing different occupations or roles of women at the time. The instructions detail the reasons for progressing, highlighting women’s life stages, intellectual engagement, and skills like reading and financial literacy. |

| Travel Guide | Edo Meisho Zue (Saitō Chōshū, 1834–1836) 江戸名所図会 | A geographic guidebook to the city’s festivals, culture, daily life, and customs, it highlights women browsing bookshops, showcasing the prevalence of female literacy and intellectual engagement. |

| Government Records | Ofuregaki Tenpō Shūsei (1941). (Edited compilation of Tokugawa shogunate laws from 1788 to 1837) 御触書天保集 | These records provide essential insight into policies shaping public morals, education, and cultural reforms during the Kansei era and beyond. |

| Educational Texts | Onna Daigaku (Kaibara Ekiken, 1729) 女大学 | A widely circulated instructional book for women from the mid-Edo period onward, written in kana script, detailing self-cultivation and household management guidelines. It illustrates how Confucian principles influenced women’s moral education and societal roles. |

| Educational Texts | Onna Shōbai Ōrai (1806) 女商売往来 | Promoted literacy and practical skills in commerce and household management by teaching topics such as account keeping, currency, goods, and essential knowledge for a merchant’s life, thereby empowering women. |

-

Note: For further exploration of Intercultural Historical Competence and their application in Edo-period studies, visit the author’s YouTube channel, Andrea Edo Research, available at https://www.youtube.com/@andreaedoresearch. aCsendom 2014.

Sources

Bungaku Bandai no Takara 文学ばんだいの宝 (“The Timeless Treasures of Literature ”) first volume, end volume, Issunshi Hanasato 一寸子花里. Source: Tokyo Metropolitan Library. Available at https://www.library.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/portals/0/edo/tokyo_library/english/modal/index.html?d=5375 (accessed 2024-11-14).Suche in Google Scholar

Jippensha Ikku 十返舎一九 (1802): Atariyashita Jihon Don’ya 的中地本問屋. National Diet Library. Available at: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/2537597/1/10 (accessed 2024-11-14)Suche in Google Scholar

Katsukawa Shunchō 勝川春潮 (1790): Ehon Sakae Gusa 絵本栄家種. National Diet Library. Available at: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/1286829 (accessed 2024-11-14).Suche in Google Scholar

Ofuregaki Tenpō shūsei vol. 2. 御触書天保集下巻. Takayanagi Shinzō 高柳眞三, Ishii Ryōsuke 石井良助 (eds.) (1941). Tokyo: Iwanami ShotenSuche in Google Scholar

Saitō Chōshū 松濤軒斎藤長秋 (1834–1836): Illustrated Guide to Famous Places in Edo (Edo Meisho Zue) 江戸名所図会 (7 volumes). Suharaya Mohei 須原屋茂兵衛 [and others]. National Diet Library Digital Collections. Available at: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/2563380 (accessed 2024-11-14).Suche in Google Scholar

Santō Kyōden 山東京伝 (1792): Onna Masakado Shichinin Keshō 女将門七人化粧. National Diet Library. Available at: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/9892663 (accessed 2024-11-14).Suche in Google Scholar

Kyokutei Bakin 曲亭馬琴 (1801): Kyokutei Ippu Kyōdenchō 曲亭一風京伝張. National Diet Library. Available at: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/8929976/1/6 (accessed 2024-11-14).Suche in Google Scholar

Kyokutei Bakin 曲亭馬琴 (1839): Nansō Satomi Hakkenden 南総里見八犬伝, vol. 9, fasc. 53-2, 14 recto.Suche in Google Scholar

Tejima Toan 手島堵庵 (1778): Zenkun 前訓, 2 vols. Edo: Sumiya Bunzō [炭屋文蔵] and others. National Diet Library. Available at: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/12865377 (accessed 2025-09-07).Suche in Google Scholar

Tōzaian Nanboku 東西庵南北 (author) (1805–1821): Shinpan Onna Teikin Furiwake Sugoroku 新販女庭訓振分双六. Wakasa-ya Yoichi. National Diet Library Digital Collections. Available at: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/1310637 (accessed 2024-11-14).Suche in Google Scholar

Utagawa Toyokuni 歌川豊国 (illustrator) (1802): Ehon’imayō Sugata 繪本時世粧 (2 volumes). Kansen-dō Izumiya Ichibee 甘泉堂和泉屋市兵衞. National Diet Library Digital Collections. Available at: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/2551580 (accessed 2024-11-14).Suche in Google Scholar

References

Amano, Haruko 天野晴子 (1989): “Onna bunshō-kei ōrai no henshū keishiki, naiyō to sono kyoikushi-teki igi 女文章系往来の編集形式・内容とその教育史的意義.” Nihon Kyoikushigaku Kaishi 日本教育史学会紀要 32: 4–15. https://doi.org/10.15062/kyouikushigaku.32.0_4.Suche in Google Scholar

Csendom, Andrea (2014): “Kibyōshi no Hihansei no Saikō: Aoto Fujitsuna-zō o Shiyō suru Kansei Nenkan no Kibyōshi no Tokuchō o Megutte” (黄表紙の批判性の再考 ―青砥藤綱像を使用する寛政年間の黄表紙の特徴をめぐって―). Kokusai Nihon Bungaku Kenkyū Shūkai Kaigiroku (国際日本文学研究集会会議録), 38, 47–60. Tachikawa: Ningen Bunka Kenkyū Kikō Kokubungaku Kenkyū Shiryōkan (立川: 人間文化研究機構国文学研究資料館).Suche in Google Scholar

Csendom, Andrea (2015): “Aoto Saemonzō no Jūnana Seiki ni Tenkai Keisei Sareru Aoto Fujitsunazō: ‘Taiheiki Hyōban Hiden Rijinshō’ to ‘Hōjō Kyūdaiki’ o Chūshin ni” (青砥左衛門像の一七世紀に展開形成される青砥藤綱像―『太平記評判秘伝理尽鈔』と『北条九代記』の解釈を中心に―). Shomotsu, Shuppan to Shakaihen’yō (書物・出版と社会変容) 19: 43–72.Suche in Google Scholar

Csendom, Andrea (2016):「寛政改革を肯定する黄表紙? : 『太平権現鎮座の始』の翻刻と解釈への試み」 (A Kibyōshi Affirming the Kansei Reforms? An Attempt at Transcription and Interpretation of Taihei Gongen Chinza no Hajime). Shomotsu, Shuppan to Shakaihen’yō (書物・出版と社会変容) 20: 279–315.Suche in Google Scholar

Csendom, Andrea (2019): “A terhesség és magzatkép az Edo-kor második felében” (Pregnancy and Fetal Imagery in the Late Edo Period). Távol-keleti Tanulmányok 10(2018/1): 119–147. https://doi.org/10.38144/TKT.2018.1.5.Suche in Google Scholar

Csendom, Andrea (2020): A Kansei-kori kibyōshi eszmetörténeti elhelyezése és fordítási lehetőségeinek vizsgálata: Forráselemzés a kutatástörténet kiegészítéséhez (The Kibyōshi of Reform-period in the Context of History of Thought, and Exploring its Translation Method: Source Analysis to Complement Research History). Doctoral Dissertation, Eötvös Loránd University. https://doi.org/10.15476/ELTE.2020.052.Suche in Google Scholar

Csendom, Andrea (2021): Kinkin szenszei álmától a jó és rossz lelkek küzdelméig – Három edói kibjósi a XVIII. századi Japánból (From the Dream of Kinkin Sensei to the Fight between Good and Bad Souls: Hungarian Translation of Three Kibyōshi from the End of the 18th Century). Budapest: Ráció Kiadó.Suche in Google Scholar

Csendom, Andrea (2023): “Yoshi no Sōshi kara miru Edo no Dokusha to Kibyōshi: Bushi Gesakusha no Intai no haikei wo Saguru” (『よしの冊子』からみる江戸の読者と黄表紙 ― 武士戯作者の引退の背景を探る.) Bunron 10: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.11588/br.2023.10.23265.Suche in Google Scholar

Deardorff, Darla K. (2020): Manual for Developing Intercultural Competencies: Story Circles. UNESCO, Routledge Focus on Environment and Sustainability.10.4324/9780429244612Suche in Google Scholar

Gomi, Fumihiko 五味文彦 (2020): Bungaku de yomu Nihon no rekishi: Kindai-teki sekai hen 文学で読む日本の歴史近代的世界篇. Tokyo: Yamakawa Shuppansha 山川出版社.Suche in Google Scholar

Gramlich-Oka, Bettina (2006): Thinking Like a Man: Tadano Makuzu (1763–1825). Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789047410003Suche in Google Scholar

Higuchi, Kunio 樋口州男, et al.. (2014): Rekishi to Bungaku: Bungaku Sakuhin wa Doko made Shiryō Tariuruka (歴史と文学―文学作品はどこまで史料たりうるか). Shōkeisha.Suche in Google Scholar

Inoue, Takaaki 井上隆明 (1986): Edo gesaku no kenkyū: Kibyōshi o shu to shite 江戸戯作の研究―黄表紙を主として. Tokyo: Shintensha.Suche in Google Scholar

Itasaka, Noriko. (2016): “The Woman Reader as Symbol: Changes in Images of the Woman reader in ukiyo-e.” In The Female as Subject: Reading and Writing in Early Modern Japan. Edited by G. Rowley, Mara Patessio, and Peter Francis Kornicki. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 61–82.Suche in Google Scholar

Itasaka, Noriko (2020): “Shaku Michi and the Takizawa Household.” In Women and Networks in Nineteenth-Century Japan. Edited by Bettina Gramlich-Oka, Anne Walthall, and Fumiko Miyazaki, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 109–124.Suche in Google Scholar

Kern, Adam L. (2006). Manga from the Floating World: Comicbook Culture and the Kibyōshi of Edo Japan. University of Hawaii Press.10.2307/j.ctt1tg5pwhSuche in Google Scholar

Kornicki, Peter. (2016): “Women, Education, and Literacy.” In The Female as Subject: Reading and Writing in Early Modern Japan. G. Rowley, Mara Patessio, and Peter Francis Kornicki. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 17–40.Suche in Google Scholar

Kuroishi, Yōko 黒石陽子 (2004): Kōen: “Esugoroku no sekai” 講演: 「絵双六の世界」 [Lecture: “The World of Picture Sugoroku”]. Tokyo Gakugei University Library, November 1, 2004. https://lib.u-gakugei.ac.jp/about/exhibitions/252/kouen.Suche in Google Scholar

Marceau, Lawrence E. (2009): “Behind the Scenes: Narrative and Self-Referentiality in Edo Illustrated Popular Fiction.” Japan Forum 21.3: 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555801003773661.Suche in Google Scholar

Miyatake, Gaikotsu 宮武外骨 (1911): Hikkashi 筆禍史. Ōsaka: Gazoku bunko.Suche in Google Scholar

Moretti, Laura and Satō Yukiko, eds (2024): Graphic Narratives from Early Modern Japan: The World of Kusazōshi. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789004691209Suche in Google Scholar

Nagata, Yoshiyuki. (1995): “Terakoya: Japan’s Endogenous Learning Institution and Its Implications for Our Developing World.” Educational Studies 37: 187–210.Suche in Google Scholar

Nagatomo, Chiyoji 長友千代治 (2017): Edo shomin no dokusho to manabi 江戸庶民の読書と学び. Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan 勉誠出版.Suche in Google Scholar

Nakamura, Yoshihiko 中村幸彦 (1982): Gesakuron 戯作論. In Nakamura Yoshihiko chojutsushū 中村幸彦著述集, Vol. 8. Tokyo: Chūōkōronsha.Suche in Google Scholar

Nenzi, Laura (2014): The Chaos and Cosmos of Kurosawa Tokiko: One Woman’s Transit from Tokugawa to Meiji Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.10.21313/hawaii/9780824839574.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Kenneth Nordgren and Maria Johansson (2014): “Intercultural Historical Learning: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 47.1: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2014.956795.Suche in Google Scholar

Partner, Simon. “Edo-Era Women’s History (2020): A Review of Recent Work in English.” Japanese Studies Around the World: 85–98.Suche in Google Scholar

Rubinger, Richard リチャード・ルビンジャー, trans. Kawamura Hajime 川村肇 (2008): Nihonjin no riterashii: 1600–1900 nen 日本人のリテラシー : 1600–1900年. Tokyo: Heibonsha 平凡社.Suche in Google Scholar

Rowley, G., Rowley, G., Patessio, M., & Kornicki, P. (2016): The Female as Subject: Reading and Writing in Early Modern Japan. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Sugano, Noriko 菅野則子 (1994): “Terakoya to Onna Shishō Edo kara Meiji e” (寺子屋と女師匠 江戸から明治へ). Hitotsubashi ronsō 111.2: 240–256. Nihon Hyōronsha. DOI https://doi.org/10.15057/10853.Suche in Google Scholar

Suzuki, Toshiyuki 鈴木俊幸 (2012): Shoseki Ryūtsū Shiryōron Josetsu (書籍流通史料論序説). Tokyo: Bensei shuppan.Suche in Google Scholar

Suzuki, Toshiyuki 鈴木俊幸 (ed.) (2015): Shoseki no Uchū: Hirogari to Taikei (書籍の宇宙 ―広がりと体系). Tokyo: Heibonsha.Suche in Google Scholar

Stanley, Amy (2020): Stranger in the Shogun’s City: A Japanese Woman and Her World. New York: Scribner.Suche in Google Scholar

Takasuka, Moe 高須賀萌, Homma Jun 本間淳, Nagasaki Kiyonori 永崎研宣, and Kigoshi Shunsuke 木越俊介 (2025): “Kibyōshi no aratana dokkai kankyō ni mukete: TEI gaidorain ni junpyo shita kōzōka no kanōsei 黄表紙の新たな読解環境に向けて―TEIガイドラインに準拠した構造化の可能性―.” Kenkyū hōkoku Jinbun Kagaku to Konpyūta (CH) 研究報告人文科学とコンピュータ(CH), 2025-CH-138.17: 1–10.Suche in Google Scholar

Takenaka, Yasukazu 竹中靖 (1962): Sekimon Shingaku no Keizai Shisō 石門心学の経済思想. Kyoto: Mineruva Shobō.Suche in Google Scholar

Tanahashi, Masahiro 棚橋正博 (1986–1989): Kibyōshi sōran 黄表紙総覧, 3 vols. Nihon shoshigaku taikei 日本書誌学大系 48.1–3. Tokyo: Aomo Dōshoten.Suche in Google Scholar

Tanahashi, Masahiro 棚橋正博 (1997): Kibyōshi no kenkyū 黄表紙の研究. Tokyo: Wakakusa Shobō.Suche in Google Scholar

Tokyo Gakugei University Library 東京学芸大学附属図書館 (2012): “Kinsei ni okeru manabi to asobi: Ōraimono to esugoroku o chūshin ni 近世における学びと遊び―往来物と絵双六を中心に.” Special Collections of the Tokyo Gakugei University Library. https://lib.u-gakugei.ac.jp/about/exhibitions/236.Suche in Google Scholar

Tomori, Maiko 戸森麻衣子 (2023): Shigoto to Edo jidai: Bushi chōnin hyakushō wa dō hataraita ka 仕事と江戸時代―武士町人百姓はどう働いたか. Tokyo: Chikuma Shinsho.Suche in Google Scholar

Yayoshi, Mitsunaga (1988): “Edo machibugyō to honya nakama” 江戸町奉行と本屋仲間, in Mikan shiryō ni yoru Nihon shuppan bunka 未刊史料による日本出版文化, vol. 3 Tokyo: Yumani Shobō.Suche in Google Scholar

Yonemoto, Marcia (2012): “Women, Words, and Images in Early Modern and Modern Japan.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 22.4/5: 802–816.10.1163/15685209-12341259Suche in Google Scholar

Wakao, Masaki 若尾政希(1999): “Taiheiki Yomi” no Jidai: Kinsei Seiji Shisōshi no Kōsō (「太平記読み」の時代: 近世政治思想史の構想). Tokyo: Heibonsha Sensho.Suche in Google Scholar

Walthall, Anne (1998): The Weak Body of a Useless Woman: Matsuo Taseko and the Meiji Restoration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Special Issue: Japanese Theoretical Approaches in the Humanities and Social Sciences

- Reading Edo through Kibyōshi: Intercultural Historical Competence and Reflections on Women’s Roles

- Der sanfte Individualismus in den Theorien von Yamazaki Masakazu und Jürgen Habermas

- Au-delà de la vision dualiste de l’être et du néant

- Epistemic (Dis)Obedience: ‘Japanese’ Theory, Structural Inequality, and Kokusai Nihongaku

- Between Law and Policy: Rethinking Judicialization through Japanese Socio-Legal Thought

- Weitere Artikel – Autres Articles – Further Articles

- Landscapes of Power: Nature Imagery and the tennōsei Ideology in Meiji-era utakai hajime

- Emotions Conducive to Awakening

- Zwischen Desinteresse und innenpolitischem Signaling – Die „Friedensstatue“ in Berlin in der japanischen Presse

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Special Issue: Japanese Theoretical Approaches in the Humanities and Social Sciences

- Reading Edo through Kibyōshi: Intercultural Historical Competence and Reflections on Women’s Roles

- Der sanfte Individualismus in den Theorien von Yamazaki Masakazu und Jürgen Habermas

- Au-delà de la vision dualiste de l’être et du néant

- Epistemic (Dis)Obedience: ‘Japanese’ Theory, Structural Inequality, and Kokusai Nihongaku

- Between Law and Policy: Rethinking Judicialization through Japanese Socio-Legal Thought

- Weitere Artikel – Autres Articles – Further Articles

- Landscapes of Power: Nature Imagery and the tennōsei Ideology in Meiji-era utakai hajime

- Emotions Conducive to Awakening

- Zwischen Desinteresse und innenpolitischem Signaling – Die „Friedensstatue“ in Berlin in der japanischen Presse