Abstract

The Imperial Office of Poetry (Outadokoro 御歌所) was established in 1869 as a court ministry of the Imperial Household Office, and was part of a series of Meiji-era institutions designed to emulate the prestige of the Nara period Imperial Court in order to legitimise the political myth of the Meiji-era Imperial Restoration. Outadokoro’s longest lasting legacy was the reinvention and organisation of the New Year’s Imperial Poetry Reading, utakai hajime 歌会始. When it became a national event in 1874, Outadokoro members encouraged all Japanese people to compose poems on the imperial theme (odai 御題), a careful selection of which were then published in the major newspapers of the time. This paper examines how nature imagery was instrumentalized to construct the mythical topography of the nation through culturally significant toponyms drawing on Shintō myths and beliefs, to reinforce the idea of national unity, and to glorify the Imperial reign. As an isolated event that continued the courtly tradition of waka poetry gatherings and largely ignored the Meiji period’s poetry reforms, utakai hajime provides a vivid framework for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of ideological tropes in poetic vocabulary, which in turn reveal an ongoing discourse of poetic celebration of Imperial rule itself. This study further examines other genres of poetry such as parodic haiku and kyōka poems from Marumaru Chinbun 團團珍聞, written in response to the prescribed imperial themes of utakai hajime, highlighting the broad and varied reception of this invented tradition.

bakudan no [1]

tobu yo to miteshi

hatsuyume ha

chiyoda no matsu no

yukiore no oto

Seeing that it is a world

where it is bombs that fall,

my first dream of the year is

the sound of the pines of Chiyoda

breaking under the weight of the snow.[2]

In January 1910, anarchist and social activist Kōtoku Shūsui 幸徳秋水 (1871–1911) penned a waka 和歌 poem for that year’s Imperial Poetry Reading (utakai hajime 歌会始), responding to the assigned topic, “snow at New Year’s” 新年雪. However, Kōtoku’s poem did more than merely respond to the set poetic topic; it subverted it. When considering the traditional belief that the first dream of the year (hatsuyume 初夢) could manifest one’s deepest desires, the poem’s vision of a desired fiery upheaval becomes evident—an incendiary attack on the Imperial Palace in Chiyoda. Literary scholar Murai Osamu pointed out that, when police discovered this poem during a search of Kōtoku’s apartment, it became a piece of evidence in the 1911 Taigyaku jiken 大逆事件 (High Treason Incident),[3] which implicated Kōtoku and others in an alleged plot to assassinate the Emperor. The trial ultimately led to Kōtoku’s execution, along with that of several alleged co-conspirators. Beyond its explicitly seditious content, Kōtoku’s poem also challenged the imperial authority and the rigid social order underpinning the New Year’s Imperial Poetry Reading, which functioned as an invented tradition intended to foster loyalty to the Emperor in creating a “utopian discourse of ‘one sovereign and myriad people’” (ikkun banmin 一君万民).[4]

This paper examines three key questions about the cultural and political significance of the utakai hajime during the Meiji period (1868–1912): What were its nature, history, and evolution in terms of renown and accessibility? To what extent did the published poems serve as vehicles for the state ideology of the Emperor system (tennōsei 天皇制) through the use of panegyric banquet poetry,[5] nature imagery, ideological motifs, and geographically-biased toponyms constructing a literary topography of the expanding Japanese empire? Finally, was Kōtoku’s parody of the imperial theme a solitary act of defiance, or did it reflect a broader, more diverse response to the utakai hajime—one that, in significant ways, strayed from the intended spirit of national unity and alignment with the nation-building agenda promoted by the government bureaucrats and poet-courtiers who orchestrated the event? Before delving into the questions listed here, a small introduction regarding the Meiji period intersection of nature, waka poetry and ideology is called for.

1 Nature, Poetry and the Nation

This article explores the confluence of nature imagery, waka poetry, and the Meiji-era ideology of the emperor system (tennōsei). Why, one might ask, focus on the waka of the New Year’s Imperial Poetry Reading rather than the abundant patriotic shintaishi poems that permeated school curricula and national media in the late Meiji period? The answer lies in the utakai hajime’s complexity: it reflects both the continuity of classical waka practice and its transformation into an invented tradition within the performative rituals of the modern nation-state—a mirror of evolving political and ideological currents. This complexity necessitates a closer examination of the ideological structures underpinning the Meiji period.

Engaging with Meiji period ideology is at once rewarding and fraught. On one hand, it marked the emergence of a new cultural hegemony under the Meiji oligarchy; on the other, it gave rise to a plurality of competing political movements, particularly in its early, turbulent decades. To speak of a singular ideology risks oversimplification. Yet some form of definition remains necessary. For the purposes of this paper, I adopt on one hand Seliger’s definition of ideology as “a set of ideas by which men posit, explain and justify ends and means of organized social action, and specifically political action, irrespective of whether such action aims to preserve, amend, uproot or rebuild a given social order.”[6] On the other hand, more recent studies also point to the lack of consistency inherent in the nature of ideologies, as these are “not as organized, internally coherent or sharp as they appear in the diversity of various writings, practices, institutions, and symbols which come to be associated with any major ideological tradition over the course of time and in differing national environments. On the contrary, ideologies evolve, fill out, develop divergent traditions and often share common elements with one another”.[7] Freeden explains the evolution of ideology through the interplay of core, adjacent, and peripheral political concepts—some of which may shift into new domains over time. Most relevant here is the notion of peripheral concepts: typically detailed and historically contingent, they are more flexible and subject to change, though still anchored by the broader framework of core concepts. Ideologies are not only logically structured but also culturally constrained, meaning their development must be understood in relation to the socio-political contexts that shape both their origins and transformations.[8] If the ideology of the emperor system can be considered the dominant state ideology of the Meiji period, then nature, as a conceptual category, may be seen as a peripheral concept—one that evolved alongside the era’s political and cultural shifts.

The ideology of the emperor system (or the tennōsei ideology) constituted a state orthodoxy centered on the figure of the emperor and was a product of the modern emperor system established with the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution in 1890, which declared the emperor sacred and inviolable. This system endured until Japan’s defeat in the Second World War in 1945, which marked its collapse.[9] Referring to the late Meiji period, some scholars use alternative terms such as kokutai 国体 ideology (Antoni 2016a, 2016b) or the ideology of the “family state” (Ishida 1954). While terminology varies, these definitions converge in identifying several key components of the ideology: an ethical foundation rooted in Confucian-inspired familialism (kazoku-shugi 家族主義) with the emperor at its apex; the mobilization of Restauration-Shintō beliefs—especially the myth of the emperor’s unbroken line of descent from Amaterasu and Japan’s supposed nature as the land of the kami—which formed the spiritual core of the kokutai (national polity) and were inculcated through the newly developed school curriculum and the ritual practices of State Shintō, with the Imperial Rescript on Education at its center; and, at its political base, a German-influenced theory of state-sovereignty that envisioned the state as an organism.[10]

The ascent of nationalism in 19th century Europe brought with it the instrumentalization of nature as an entity characteristic or emblematic of the imagined nation. Thomas’s (2002) answer as to why this should be so is that

Nature necessarily functions as a powerful political and ideological concept. Whoever can define nature for a nation defines that nation’s polity on a fundamental level. In so doing, they also define the individual liberty commensurate (or incommensurate) with that polity. A nation’s sense of nature—whether as challenging frontier or Edenic garden; as boundless natural resource, picturesque landscape or imperiled environment; as permanent Confucian hierarchy, evolving Darwinian society, or organic family-state—bespeaks its sense of collective and individual possibilities.[11]

In her study, Thomas can be said to embark on a critique of the theoretical framework on nature and modernity advanced by Maruyama Masao, which “denounced the natural as a reflection of premodern thinking, while extolling the notion of a created (sakui) sociopolitical order as a full manifestation of modern political consciousness.”[12] Based on pertinent documents of the Meiji period, Thomas demonstrated that multiple conceptions of nature were aligned with diverse political positions, from the autocratic, democratic to the anarchic. Of interest here is Thomas’ suggestion that the Japanese understanding of nature underwent three radical shifts from Tokugawa times to 1950, which involved three successive paradigms of nature: (1) “the universal, hierarchical concept of the Tokugawa period,” wherein nature was imagined as the “place” of political authority; (2) “the social Darwinian ideas of competitive struggle and inevitable progress,” wherein Meiji thinkers variously understood nature temporally; and (3) the “celebration of a uniquely harmonious, natural nationhood,” wherein early twentieth-century thinkers envisioned nature as the nation.[13] The transition between the second stage, which characterizes the early Meiji-era, and the third stage which overlaps with the ‘long Meiji’ (1880–1920s) is particularly relevant for the understanding of the ideological context in the time when poems of the utakai hajime started being published in mainstream media. According to Thomas, because social Darwinist conceptions proved less compelling for a national political ideology such as the tennōsei, due to their implications that Japan lagged behind the ‘West’ and that social and political turmoil was a natural and necessary part of public life, the search in the 1890s for a reconfigured modernity led ideologues to a “nationalized conception of nature” in conformity with the requirements of national pride.[14] This new conception of nature was at the basis of another form of modernity that could supply the necessary ideological ballast for a nation in international competition and an elite striving to maintain domestic control. Given that political theory was long dominated by the idea of social evolution, there appeared a hiatus in nature’s overt political presence from the 1880s to the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). Therefore, nature’s reformulation occurred in the cultural realm, through changes in vocabulary, literature, and approaches to landscape that nationalized the concept of nature, destroying its universalist and progressive implications.[15] For this, nature had to be acculturated and sacramentalized, which occurred through diffuse and uncoordinated efforts[16] in two related transformations: the first was the reinterpretation of nature as immanent rather than as external; the second was stripping the concept of nature of its universal connotations and making it refer to Japan in particular. Overall, the acculturation of nature “eroded its polyvalence and universality and destroyed its capacity to refer to a moral and political code outside the particularities of Japan”[17] so much so that, by the end of the 1890s, “nature had begun to acquire the reflective surface that would make it a narcissistic mirror for the nation.”[18]

As this article explores nature imagery in utakai hajime poems within the context of tennōsei ideology, a brief overview of nature‘s role in waka poetry and the terminology used to analyze it is necessary. Classical waka has long been entwined with natural imagery, displaying a persistent attachment to nature that has led scholars to debate whether it is fundamentally lyrical or descriptive. In the view of Toyo Isuzu, waka could even be defined as self-expression through description of nature, as “the things and events of Nature, coordinated with various means and techniques of semantic association, are here made to function as a powerful instrument of evocation, enriching aesthetically the poetic ‘field’ of waka, amplifying its connotative capacity and providing with an empirical basis the multidimensional intricacy of the semantic association.”[19] Ōnishi called the totality of associations present in waka an “invisible aesthetic ‘resonator’ hidden under even a tiny piece of nature, forming by an age-long accumulation of the cultural experience of the nation.”[20] Furthermore, as Toyo points out, the units of semantic association achieve an evocative significance against the background of the vast totality of associative networks of nature interlinked with human affairs. In Toyo’s view, this leads to the scarcity of waka poems “devoid of a feeling of the cosmic amplitude of nature,” regardless of their main subject.[21]

However, as waka scholars as early as Kamo no Chōmei 鴨長明 (1153–1216) have shown, the semantic associations engendered by well-established waka tropes are fixed in their nature. To name just one example, the first snowfall should be accompanied by feelings of anticipation of the poet, while the same cannot be said of an autumnal shower or hail. The ossified poetic practice of waka until the eve of the Meiji period could thus be considered a stereotypical portrayal of nature from a stylistic point of view, as natural elements are conventionally idealized, backed as they are by a “conventionally established associative network of the peculiar images and ideas which they evoke”.[22]

In the poems analysed below, I focus on ‘nature imagery’ as a means of naming stylistic tropes which depict nature. As Pauline Yu has shown in her 1987 study on imagery in the Chinese poetic tradition, the notion of ‘imagery’ enjoys a rich tradition in Western literary thought, culminating in its present-day doubleness of meaning as both sensuous content and figurative language.[23] With regard to the appropriateness of employing Western literary concepts in analyzing Japanese poetry, Smits also favors the term imagery to that of metaphor, as a useful critical term because he deems it to adequately substitute the Japanese mitate and to be “the most inclusive in suggesting a relationship between an object named and an implied meaning, encompassing both the verbal depiction of sensuously apprehensible objects and figurative language which usually involves some process of comparison and/or substitution.”[24] While the Western understanding of metaphor relies on a comparison meant to illustrate a certain aspect of the entities compared, the use of imagery implies a wider range of associations. Smits discusses the similarity of the Chinese poetic principle lei to Japanese poetic devices such as the idea of a hon’i of a waka topic, with both principles demarcating the areas of imagery available to the poet given a specific scene (for example, the portrayal of the moon as a suitable autumn motif). Other Japanese terms of renga and haiku poetry also bring to mind similar processes of association, such as kigo 季語 (“season words”) and yoriai 寄合 (“conventional association”). In this respect, there are no purely ‘innocent’ images in traditional waka poetry.[25] For the purposes of this paper, nature imagery encompasses both conventional natural motifs—long associated with auspicious imperial rule, such as the “cloudless sky” or “tranquil sea,” as seen in imperial anthologies beginning with the Shinkokinshū and in Nō theatre—and instances in which such imagery departs from established symbolic frameworks to take on newly articulated meanings in Meiji period waka poetry, particularly those composed for the utakai hajime.

2 Old Customs in New Attire: utakai hajime on the National Stage

Utakai hajime[26] started out as a waka poetry gathering sponsored by the Emperor, restricted to favoured members of the aristocracy. Its exact historical origins are unknown. However, from a description of January 13, 1202, in Meigetsuki 明月記, the diary of the famous poet Fujiwara no Teika 藤原定家 (1162–1241), we know that it was regularly taking place in the second half of the 12th century.[27] Sakai Nobuhiko (1998) noted the continuity of the utakai hajime into the present, with near-annual occurrences during the Edo period (1600–1868). He observed that in the early modern period, it was a public event attended by regents and ministers, but in 1872, early in the Meiji era, it was revised to allow junior officials (hanninkan 判任官) of the new government to submit poems.[28]

A truly radical shift in the nature of the utakai hajime occurred in 1874, when Kokugaku scholar and Shintō priest Shimozawa Yasumi 下澤保射 (1838–1896) successfully petitioned the Imperial Household Agency (Kunaishō 宮内省) to open the event to all Japanese subjects, regardless of class or gender. From 1880 onward, between 24 and 31 poems were published annually in major newspapers and the government gazette. These poems fell into three distinct groups: first, those printed in larger characters, including the Emperor’s (gyosei 御製), the Empress’s (miuta 御歌), and later, poems by the crown prince and princess; second, poems by prominent figures—nobles, statesmen, members of the Outadokoro, military personnel, and occasionally Shintō clergy; and third, the “selected poems” (senka 撰歌), a group of 5–7 poems chosen from public submissions to the Imperial Household Agency. As we shall see, only toward the end of the Meiji period did these selections begin to include more “commoners” unconnected to the imperial court, whose waka increasingly diverged in content and style from classical aesthetics.

For the purposes of this analysis, and as I am looking at utakai hajime from the perspective of nation-building efforts, I considered the utakai hajime poems from 1880 to 1912, as they were first published in newspapers (746 poems). Although the total number of poems published each year varied in the Meiji period between 24 and 31, the number of selected poems stayed between 5 and 7. The latter, which were supposed to include poems from all over the country and be truly inclusive, were in fact strongly biased toward the participation of politicians, nobles and people with ties to the government.

By means of the increasingly wide media exposure and the ongoing promotion of general participation, the ceremony took on a modern, national-symbolic significance, presenting a powerful image of people and Emperor alike joined together in the composition of waka poetry. In literary scholar Murai Osamu’s view, utakai hajime was part of the key process in the “nationalization” (kokuminka 国民化) of waka, which led to the very act of writing waka entailing a kind of “subject formation” (shutaika 主体化).[29]

In some ways, the transformation of utakai hajime from a private court event to a national event can be seen as a creation of what Hobsbawm termed to be an ‘invented tradition’.[30] The now well-established concept was defined by Hobsbawm as a “set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behaviour by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past”.[31] Hobsbawm also drew attention to the fact that such an invention of traditions is more likely to take place at a time when “a rapid transformation of society weakens or destroys the social patterns for which ‘old’ traditions had been designed, producing new ones to which they were not applicable” and that such invented traditions can readily be grafted on old ones, by borrowing from the “well-supplied warehouses of official ritual, symbolism and moral exhortation—religion and princely pomp”.[32] The utakai hajime, as reconfigured in the Meiji period, can thus be said to reflect in part elements of all three (overlapping) types of invented traditions as outlined by Hobsbawm. Firstly, through its function as a tool to symbolize and legitimize imperial authority, in the case of the Meiji period a ‘new’ political institution and, by association, the Meiji state as well; secondly, it could inculcate beliefs and value systems—in this case the poems praising the imperial reign would inculcate a feeling of imperial loyalty and, after 1890, the often occurring nationalistic fervour a feeling of cultural superiority; furthermore, the organisation of the event itself reinforced the notion of Japanese culture as a culture of long-standing traditions and of the imperial house as both a safeguard and a metaphysical core of Japanese culture, with the emperor at the apex of the literary hierarchy of the land; lastly, the Meiji period utakai hajime can also be seen as establishing and symbolizing social cohesion and the feeling of belonging to a national community.[33]

Through its appeal to antique traditions, centring on the Emperor, the utakai hajime also mirrored the transformation and creation of numerous Shintō rituals centring on the Emperor.[34] These rituals, such as the enthronement ceremony, Daijōsai 大嘗祭, and Niinamesai 新嘗祭, were no longer confined to the seclusion of the Imperial palace, but were instead imbued with national significance. This shift underscores the Imperial family’s increasing prominence within the emerging national identity of the Meiji-era. Such ceremonies exemplify what anthropologist Clifford Geertz might describe as the “theatre of power,” in which the imperial institution was instrumentalized to embody and reinforce state ideology,[35] a fitting description for the Meiji-era government’s directive of integrating politics and ritual under the principle known as saisei itchi 祭政一致.

While emblematic of the era, such grand rituals also prompt inquiry into the individuals and mechanisms behind their orchestration. In the case of utakai hajime, the selection of topics, curation of poems (senka 撰歌), and supervision of the recitation ceremony (utakai hajime no gi 歌会始の儀) fell to the newly established Imperial Bureau of Poetry (Outadokoro 御歌所). Operating within the Imperial Household Agency from 1888 to 1945, this institution deliberately echoed the homophonous Ōutadokoro 大歌所 of the Nara period. Its creation exemplifies the Meiji state’s broader effort to emulate ancient imperial prestige, reinforcing the political myth of an ‘imperial restoration’ (ōsei fukko 王政復古). Through rituals like utakai hajime, the Outadokoro also exemplifies the phenomenon of invented tradition.

The bureau’s activities included critiquing poetry by court nobles, advising and teaching Emperor Meiji (an active poet), composing and compiling poetry and scholarly works, and organizing monthly gatherings (tsukinami utakai 月並歌会). Yet its most enduring legacy lies in the modern reinvention of utakai hajime, still held today and broadcast via mass media. Alongside the wartime dissemination of Emperor Meiji’s poetry—especially from the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905)—the Outadokoro successfully linked waka composition to national identity. Poetically, the bureau was often seen as a modern continuation of the Keien school 桂園派, founded by Kagawa Kageki 香川景樹 (1768–1843), whose disciples formed its early membership. Within Meiji literary circles, members of the Outadokoro occupied a unique and often contested position. While institutionally powerful and closely aligned with the imperial court, their poetic style—rooted in classical precedent and courtly decorum—stood apart from the emerging literary movements that emphasized realism, individual expression, and vernacular language. Outadokoro poets composed waka poetry following conservative ideals of literary aesthetics and highly valuing the Kokin wakashū poetry anthology.

It was largely assumed in academic scholarship that the Outadokoro group dominated[36] the poetics of the Meiji period until the 1880s when they fell into decline, but this has been disproven by recent studies, which showed that publications by Outadokoro poets in leading literary magazines did not abate.[37] Much was made of the rivalry between Outadokoro and Ochiai Naobumi’s 落合 直文 (1861–1903) Man’yōshū-revering school of poetry, Asakasha 浅香社, at the beginning of the period, with critics such as Okazaki noting however that this conflict did not lead to a wider reform of waka poetry, but amounted merely to a ‘tempest in a teacup’.[38] It was a second, much larger conflict resulting from Masaoka Shiki 正岡子規, (1867–1902) and Yosano Tekkan’s 与謝野鉄幹 (1873–1935) attack on Outadokoro poets[39] that led to the scholarly reframing of poetic traditions as belonging either to the ‘old school’ kyūha 旧派 or the new school shinpa 新派, and to what has been considered the birth of the modern tanka poetry, as directed by Masaoka Shiki’s principles of realism and individuality. However, beyond specific poetic schools the Outadokoro coexisted in competition with, one could imagine the Outadokoro as an island of traditionalism—for the most part as conservative in their literary endeavors as in their political inclinations—in a sea of literary novelty that unfolded in the Meiji period. To borrow Schamoni’s expression, the latter half of the 19th century in Japan amounted to a geography of changing literary genres, with the apparition of shintaishi genre and the modern tanka, the birth of the Meiji I-novel and new forms of theatre, to name a few. Schamoni traced two essential tendencies of the literature of this age: firstly, the rise of the “enveloping genre” literature, understood as the idea of a purified “literature” guiding the discussion of individual genres, whereby smaller genres with separate traditions were united under more systematic headings. Secondly, literature came to be viewed as an autonomous art, divorced from its previously stated moral or political purpose. The positioning of literature became even more radical in the 1890s, when, amidst the first signs of disintegration” in the new society (when early reports on shocking working and living conditions among “lower society” were published between 1888 and 1889), “literature came to claim a special position—no longer an equal position with politics, science, religion, etc., but elevated above all as the only place of ‘unmutilated humanity.’”[40] One of the most defining developments in Meiji period literature was the creation of a standardized literary language through the genbun itchi 言文一致 movement. This shift influenced both established and emerging literary genres—with the notable exception of waka, which continued to resist linguistic reform even after the 1946 legal adoption of the spoken vernacular.

If so far I have outlined several contrasts between Outadokoro’s continued tradition of classical waka poetry and the appearance of new literary genres or schools of poetry, it is important to note two facets in which Outadokoro could be seen as emblematic of wider literary phenomena of the Meiji period. On one hand, beyond waka poetry itself, other poetic genres also played a vital role in the Meiji nation-building project. As Joshua Mostow notes, both waka and haiku were deeply entwined with the formation of the modern imperial Japanese state. Michael Bourdaghs similarly emphasizes poetry’s centrality to the national imagination, observing that nationalist critics in the 1890s called for a new national poetry to give voice to the people—among them Masaoka Shiki, whom Bourdaghs describes as “explicitly nationalistic.”[41] On the other hand, Tuck (2018) demonstrated that poetry, as practiced in Meiji Japan, was active, dialogic and above all social—in what amounts to a ‘poetic sociality’—, with poetic genres being just as common as serialized prose fiction in Meiji Japan’s print media, with submissions by readers being greatly encouraged. Therefore, “where only a tiny handful of people in Meiji Japan might ever manage to have a novel set before the reading public in serialization or book form, literally millions could (and did) publish poetry.”[42] Utakai hajime, with its emphasis on public participation, shared themes, and collective reception, should also be understood within this broader context of poetic sociality.

In this light, the Keien school particularly encouraged the composition of poetry on traditional topics (daiei 題詠). This adherence to traditional poetry mores to the detriment of Meiji-era poetic reforms often stands out in the proposed poetry topics[43] as well as the poems selected for publication within the utakai hajime itself.

Starting with 1877, Takasaki Masakaze (高崎正風, leader of Outadokoro between 1888 and 1912),[44] was entrusted with proposing the imperial poetry theme (chokudai 勅題) and he often served as a judge (tenja 点者) of submitted poems (eishinka 詠進歌). After 1897, in addition to its leader, the bureau consisted of 8–11 permanent members with different functions. The two most prominent among them also had a definitive role in organising the utakai hajime: the yoriudo 寄人 (or fellows[45]) were also involved in the poems selection process,[46] while the sankō 参候 (consultants[47]) were responsible for coordinating and carrying out the recitation ceremony of utakai hajime.[48] In 1909, presumably in response to critique on Outadokoro’s poems selection process, Ōguchi Taiji 大口鲷二 (1864–1920) elaborated on the selection criteria imposed on yoriudo members such as himself by the bureau leader Takasaki Masakaze:

The original purpose of composing poems has long been misunderstood, and there is a harmful tendency to think that composition of poems amounts just to a competition of poetic techniques. In the world of poetry composition, people forget to express their own individual feelings, and instead just look for material to use from old poems. Many poems are composed to show off one’s erudition, so the more famous the composer, the more artificial the poem becomes, and the further it is removed from human emotion. Therefore, the policy regarding the selection of poems by Takasaki, the director of the poetry bureau, is that […] we should first look at the emotion (kanjō 感情), then the style (kakuchō 格調), and finally the skill (kōsetsu巧拙) [manifested in the poems]. Now, rather than so-called professional poets, it is, on the contrary, amateur poets whose works more frequently convey emotions. Of course, one should study poetry to such a [great] extent,[49] but we must distance ourselves from the stench (shūmi 臭味) that belongs to the exclusive domain of the poets’ school. I wish that nobody should forget that the spirit [of utakai hajime] is so that these are not [meant to be] poems of poets, but poems of the people.[50]

To summarize this quote, it is important to note that, if Ōguchi is to be believed, the authenticity or abundance of emotion of a waka poem was given precedence in its evaluation to the detriment of poetic skill. The emphasis on emotion stems from Outadokoro’s connection to Kagawa Kageki’s[51] Keien school, which revered the Kokinwakashū 古今和歌集 and built upon its preface’s assertion that vernacular poetry was a natural outburst of human emotion in response to external stimuli.[52] This view of poetry was also stated by Outadokoro’s leader, Takasaki, in the first congratulatory issue of Sasaki Nobutsuna’s 佐佐木信綱 (1872–1963) literary magazine Kokoro no hana こころの華 [53] in 1898. Furthermore, the political nature of utakai hajime and the Confucian ideal of poetry as an aid to governance is seen in the stance of Outadokoro as portrayed here by Ōguchi,[54] particularly in his view that the poems collected stemmed from the people, not the poets.

Due to its relevance with regard to the organisation of utakai hajime and the poem selection, a few words are needed here on the development of the idea of poetry as a tool for good governance. The concept attributed poetry the role of fostering harmony between social classes (e.g. the ruler and his officials) and enabling the rulers to understand the feelings of the ruled. It surfaced in the history of Japanese poetic discourse now and again. From the time of Emperor Saga’s 嵯峨天皇 (786–842) reign, when the state-literature theory (monjō keikoku ron 文章経国論)[55] laid out by Emperor Wen 文帝 (202–157 BCE) became a guiding principle for Saga’s court. As far as early modern waka poetry is concerned, the theory of poetry as a tool for governance resurfaced in Kamo no Mabuchi’s contribution to the famous debate surrounding the role of poetry, in Kada no Arimaro’s work (1706–1751) Kokka hachiron 国家八論 (Eight Essays on Japanese Poetry, 1742).[56] In response to Kada no Arimaro’s controversal claim that poetry has no ethical or political function at all, Tayasu Munetake (1715–1771) invoked the kanzen chōaku principle and advocated for a genuine poetry as the only poetry able to fulfill a moral purpose, while Kamo no Mabuchi argued that poetry which authentically conveys emotions as they are can present “aspects of human experience that fall outside the narrow confines of the morally defined principle of Song Confucianism.”[57] For Takasaki, as for Mabuchi before him, poetry aided in the formation of community, on an emotional level, such as by moderating the unruly emotions that give rise to social chaos, and by allowing rulers to understand the emotions of the ruled. In other words, like the utaawase 歌合 at the imperial court in premodern times, the Meiji-era utakai hajime was not a purely literary competition, but was endowed with a wider political agenda.

Outadokoro members such as Chiba Taneaki 千葉胤明 (1864–1953) or Ban Masaomi 阪正臣 (1855–1931) also promoted utakai hajime extensively in literary magazines such as Kokoro no hana or Outadokoro’s own literary magazine, Wakatake わか竹,[58] by providing guidance on how to compose waka poems and how to submit them to the Outadokoro.[59] Starting with 1880, the selected poems were published in all major newspapers of the day, as well as in the government’s gazette, Kanpō 官報. In addition, a selection of the poems was often published in literary magazines, and sometimes even in smaller publications such as The lady´s magazine (Fujin kyōkai zasshi 婦人教會雜誌[60]). Over time, the media’s reception of utakai hajime started to include further information, such as the numbers of submitted poems from each prefecture, descriptions of the ceremony, announcements of the jury or the performers during the recitation ceremony, as well as controversies such as the submission of too similar poems, or the favouritism of one prefecture (Aichi) over all others in the ‘selected poems’ category (senka 撰歌) mentioned above.

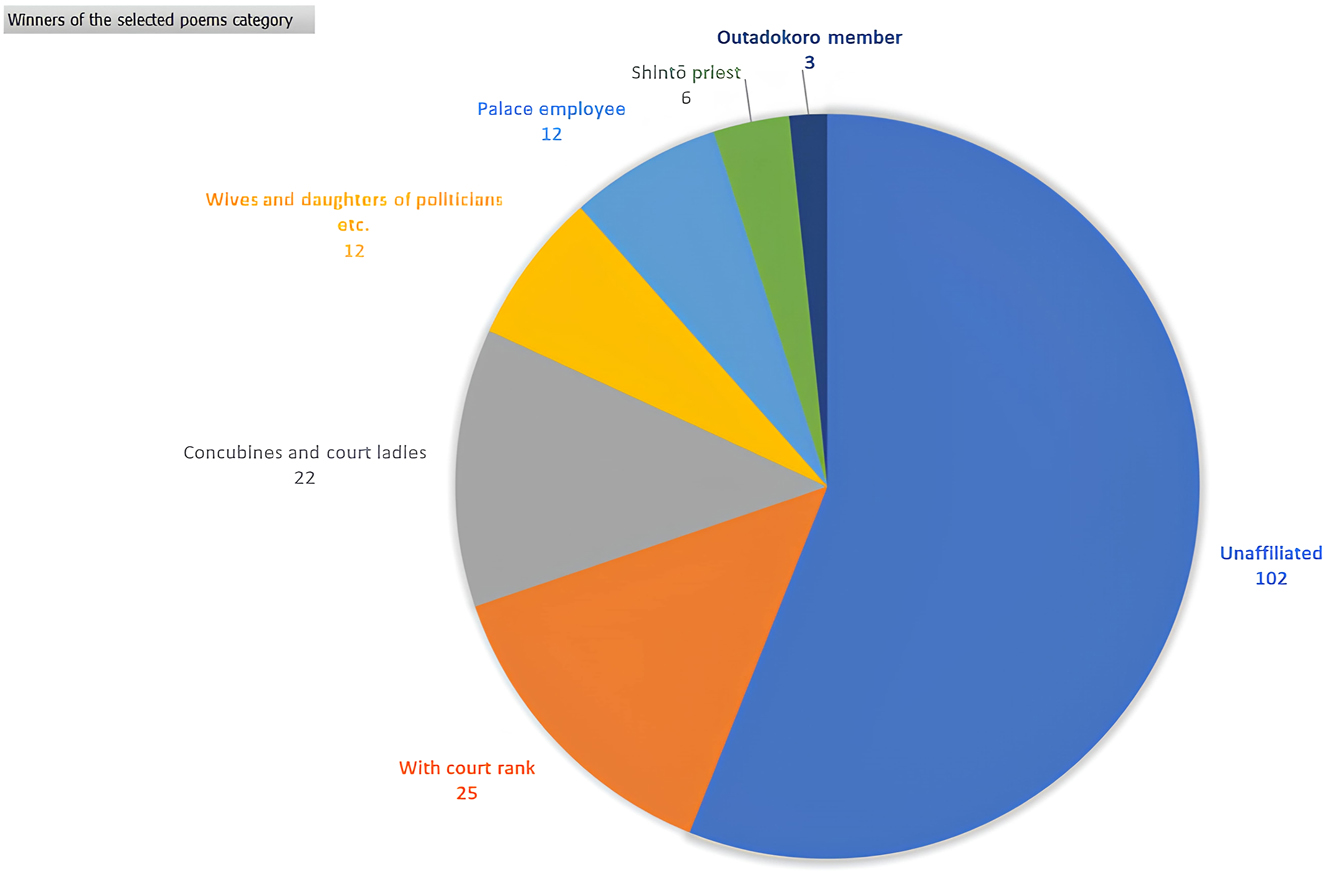

Initially, the number of participants was small, and those whose poems were selected were not invited to the palace to hear their poems recited.[61] However, given the magnitude of utakai hajime’s presence in national media, and presumably due to the 50 % increase in Japan’s population, the number of submitted poems grew from about 3,000 in 1885 to almost 30,000 by 1912. Given its growing visibility, one might be inclined to believe that utakai hajime was at least partially achieving its aim of embodying national unity by presenting an image of ruler and subjects joined in the composition of waka poetry. This projection of unity, however, was not without its contradictions. Political and intellectual elites affiliated with the Meiji government were disproportionately represented among the selected poems (senka 撰歌). As demonstrated below, even as the number of submitted poems (eishinka 詠進歌) rose dramatically, only slightly more than half of the 182 selected poems between 1880 and 1912 were authored by commoners without a connection to the imperial court or the Meiji administration (Figure 1).

Social rank or occupation of the authors of the selected poems category of utakai hajime, 1880–1912.

Of the 182 selected poems (senka) between 1880 and 1912, 102 were from commoners without obvious links to the Meiji political apparatus, that is without official declaration of their social rank in the paratext. The authors of 25 poems are addressed with a court rank, 12 designated as palace employees and three were members of Outadokoro. In addition, more than half of the 50 selected poems (senka) by female poets were either written by concubines and court ladies (22 poems), or by wives or daughters of prominent politicians, bureaucrats or soldiers (12). There are also a number of poems by Shintō priests or officials, as well as by Buddhist clergy.

With regards to the poems by members of the imperial family, aristocracy, politicians and government bureaucrats, there are three persons whose poems are featured every year between 1880 and 1912: Emperor Meiji, Empress Shōken and the leader of Outadokoro, Takasaki Masakaze, with 30 poems each.[62] They are followed closely by Grand Chamberlain Tokudaiji Sanetsune 徳大寺實則 (1840–1919)[63] with 27 poems, politician Ōhara Shigetomo 大原重朝 (1848–1918) with 25 poems, Outadokoro member Ayanokōji Arikazu 綾小路有良 (1849–1907)[64] with 21 poems and Maeda Toshika 前田利鬯 (1841–1920)[65] with 18 poems. Poems by various princes and princesses were published between 10 and 14 times, with a similar number reached by Nishiitsutsuji Ayanaka 西五辻文仲 (1859–1935)[66] with 14 poems and Nabeshima Naohiro 鍋島直大 (1846–1921)[67] with 13 poems. A closer look at the frequency with which certain poets were selected shows that for some prominent politicians there exists a period of up to ten years in which they were chosen each year (for example, Nabeshima Naohiro, Maeda Toshika, or Sanjō Sanetomi 三条実美 (1837–1891)), while other less prominent politicians, with fewer contributions, seem to rotate and published regularly every three to five years, e.g. Matsura Akira 松浦詮, Nagatani Nobunari 長谷信成, Sugi Magoshichirō 杉孫七郎.

3 Utakai hajime Poems and Ideology Dissemination

As we have seen so far, utakai hajime was a highly politicized court event that purportedly served as a bridge between the Emperor and the people and reaffirmed a close connection between waka, national identity on one hand and waka and the imperial house on the other hand. Until 1904, utakai hajime publications were also the only occasion in which people could read poems of Emperor Meiji.[68] As mentioned above, one can regard utakai hajime as an invented tradition in the sense used by Eric Hobsbawm, and furthermore as a political ritual which reinforced political symbols and political myths of the Meiji-era state ideology. However, the impact of utakai hajime in Meiji society and its role in the cementing of national identity cannot be accurately examined without taking into account the epochal change brought about by the emergence of national newspapers in Japan, and their portrayal of the event.

In this regard, the phenomenon of utakai hajime, with its choice of waka poetry as a quintessential Japanese literary genre (with a long history and strong ties to the imperial family, in itself emblematic of the new Meiji nation), fits the framework of Anderson’s concept of how the nation came to embody an imagined community in two crucial ways. Firstly, due to the idea of a common language and literature (in this case waka poetry) and secondly due to the role of newspapers in which the common language and the simultaneity of news played a central role in a group’s conceiving of itself as a unified national people.[69]

With regards to the content of the 764 published poems between 1880 and 1912, in my estimation, at least a half of them are evocative of the typical characteristics of waka banquet poetry, being celebratory in nature, whether wishing a long life to the emperor or his reign (as befitting banquet poems), or containing encomiastic statements regarding the emperor, Japan and the Imperial Reign. Circa 13 % of poems explicitly reference the Imperial reign, while 10 % reference the Imperial palace or its surroundings (e.g. the hills or the pond on the premises).[70] Thus, with the exception of allusions to current political and military events, or expressions evocative of the emperor-system ideology as it emerged in the Meiji period, such characteristics of the utakai hajime poems are by no means a new development of the Meiji period, as they pertain to characteristics of banquet poetry. Furthermore, they illustrate the social and political dimensions of waka as a poetry genre in what Earl Miner termed “the institutionalized adulation found in the presenting of poems and in the ceremonies accompanying poetry matches”.[71]

As a characteristic of premodern court poetry genres, such as waka, certain topics had to be explored from more or less given angles, or as Steven Carter put it, one had to know one’s ‘poetic geography.’[72] Thus, another typical feature of Meiji utakai hajime is a certain redundancy in the poems’ vocabulary and content, especially in the early 1880s, when most of the published poems reference the imperial palace in some way or another. There are many adverbs denoting tranquillity like nodoka ni 長閑に and shizuka ni 静かに or serenity kumori naki 曇なき (‘cloudless’), together with expressions like ugokanu うごかぬ or kawaranu かわらぬ emphasizing the stability of the imperial reign or dynasty or its unchanged—by implication, unperturbed—character since the “divine age of the kami”. Another characteristic shared by utakai hajime poems with banquet poems in general is the frequent appearance of compounds with the word for ‘one thousand’ (chi 千), such as chitose 千歳 ‘one thousand years’ or chiyo 千代 ‘one thousand generations’, which were conventionally used in poetry as wishes for the long life of a superior.[73] The most well-known among such poems is without question the poem that became the national hymn of Japan, kimi ga yo.

Beyond the characteristics outlined above, the poetic language of utakai hajime compositions often reflects the state ideology promoted by the Meiji government. As mentioned above, central to this ideology underpinning the emperor system (tennōsei) was the political myth of Japan’s exceptionalism, rooted in its supposedly uninterrupted imperial lineage, with Japanese emperors believed to be direct descendants of Amaterasu Ōmikami, who serve as intermediaries between the people and the kami.[74] This notion is articulated in certain utakai hajime poems, which convey ideas such as the nation being a sacred inheritance from the imperial ancestors of the divine age (kami no yo). They also evoke the belief in the continuity of the current state—whether of nature, or the nation—as an unaltered (ugokanu or kawaranu) and implicitly prosperous legacy since the age of the gods. This is exemplified in a poem by Kitakōji Yorimitsu 北小路随光 (1832–1912) from 1890, the year the Meiji Imperial Constitution was promulgated.

kami no yo ni [75]

sadameshi mama ni

tsutae kite

ima mo kaharanu

ōyashima kuni

Oh, Great Japan,

this even now unchanging land,

handed down to us,

as it was decided

in the age of the gods![76]

In a few instances, there are even specific references to Amaterasu, as in this poem by Emperor Meiji, submitted in 1891, which clearly illustrates his projected role as a medium to the kami:

tokoshie ni [77]

tami yasukaredo

inoru naru

waga yo o mamore

Ise no okami

I pray that the people

can live peacefully,

for all ages to come —

protect our world,

Oh Great Goddess of Ise [Amaterasu]!

Or in the poem by the Emperor’s tutor in Confucianism, Motoda Eifu 元田永孚 (1818–1891), submitted in 1890:

Amaterasu [78]

kami no miyo yori

kimo mo omi mo

hitotsu kokoro no

kuni ha kono kuni

Since the time

of Amaterasu’s reign,

it is this land in which

Your heart and the people’s hearts

are united.

Indirect references to Amaterasu are also made, such as this 1890 poem by Ayanokōji Arikazu, which employs the language of Nihon Shoki in the expression teritoori 照りとほり, in the episode of Amaterasu being described by Izanami and Izanagi as illuminating the whole world with her light,[79] thus implicitly comparing the ‘glory of Japan’ with her divine light:

taguinaki [80]

sumeramikuni no

hikari koso

yorozuyo made mo

teritoorikere

It is the light

of this Imperial Land

without compare

which shines all over the world,

for ten thousand generations to come!

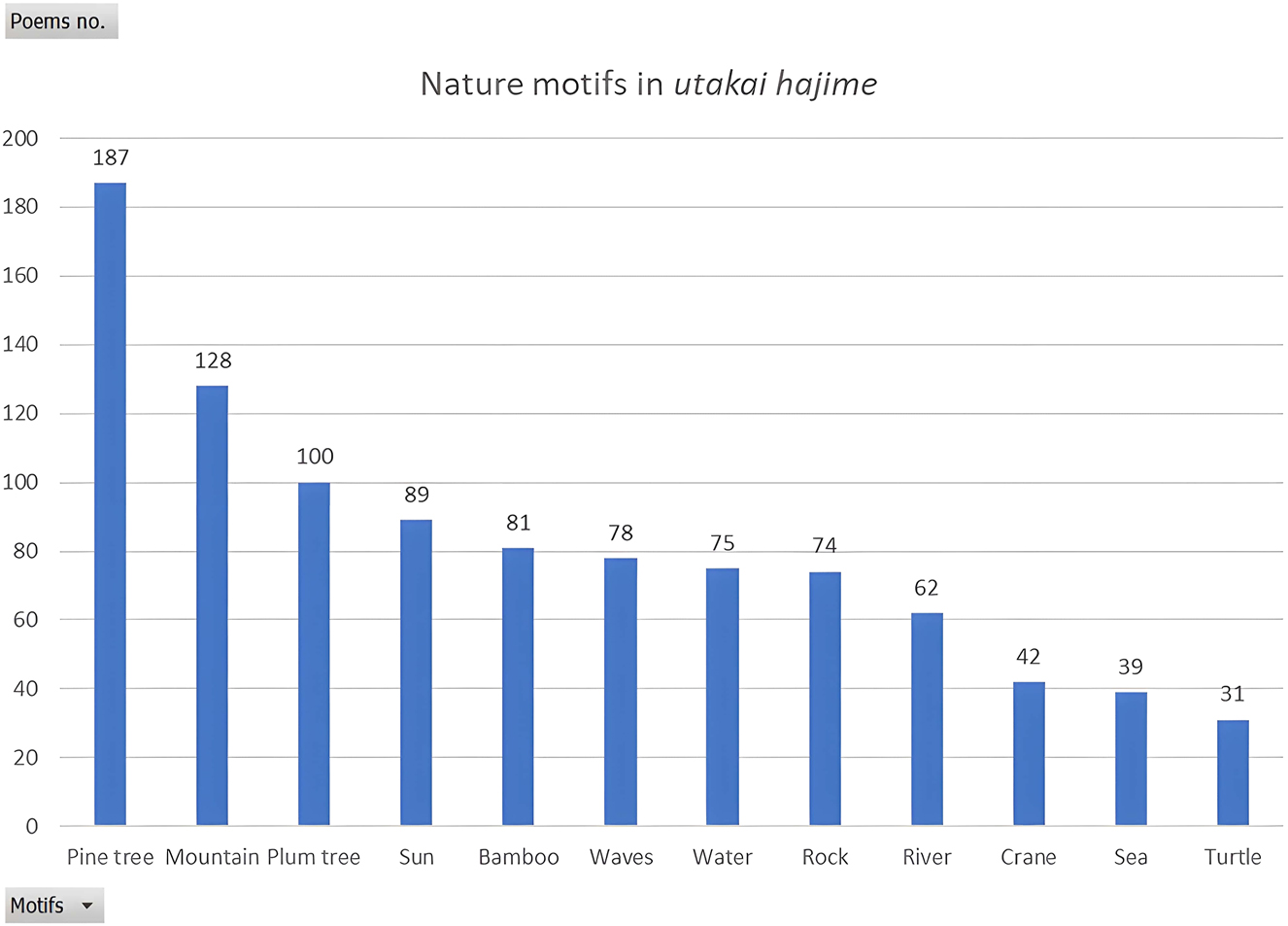

Beyond explicit references to the propagated state ideology, the poems also often bring the imperial house into focus by means of the scenery and nature elements employed in fashioning poems on the prescribed imperial poetry topic. One striking feature is the high occurrence with about 20 % of the pine motif in the imperial poetry themes, especially after 1900. Much like cranes or turtles, the pine is a well-known symbol for longevity and a common theme in banquet poetry. However, one could legitimately wonder if its heightened use in this context is due to its association with the imperial house. The pine as a motif also occupies the highest rank in the following ranking of the appearance of nature elements in utakai hajime poems (Figure 2).

Number of appearances of nature motifs in poems of the utakai hajime, 1880–1912.

It is followed by mountains, and plum trees, which can be explained by the utakai hajime taking place in winter and such motifs being seasonal words associated with winter, in concordance to the traditional practice of waka poetry. Often more than one of the listed motifs makes an appearance in a poem.

In the following section, I will highlight other means through which utakai hajime poems disseminated and reinforced the state ideology surrounding the emperor system with the use of toponyms in what becomes an interplay of spatial construction, mythic narrative, and the fostering of national unity in waka poems of the utakai hajime.

4 Nature Symbolism in Service of the State

To begin with, I would like to introduce two theoretical models for the shaping of literary spaces.[81] Firstly, Andreas Mahler (1999) describes three methods for shaping literary spaces: geographical localization, chorographic configuration, through which the topological space manifests itself as a visible and “physically accessible space”, and atmospheric specification (atmosphärische Spezifikation)—in which qualitative predicates are assigned to the individual spatial components.[82] Secondly, Gerhard Hoffman distinguishes between three spatial types or spatial designs: (1) the space of action: first and foremost the setting for an ‘acting subject’/the plot, (2) the “tuned space” (gestimmter Raum): places and objects function primarily as atmospheric, symbolic, emotionally charged ‘carriers of expression’ and (3) a “visual space” (Anschauungsraum): a distant space that primarily offers a ‘panoramic overview’, predominantly static in conception, not a limited location for action.[83]

As a general characteristic, depictions of space in the framework of utakai hajime can be seen on both a paratextual as well as a textual level. As scholars have noted elsewhere,[84] the place of provenience of the poems of the selected category grew to include poems from newly acquired territories, be they Okinawa, Taiwan or Korea, thus signalising that thus signalising that colonial subjects could also be culturally assimilated through their composition of waka poetry.

At the textual level, the literary depictions of space in utakai hajime poems encompass a range of representations. These include geographical localization, as per Mahler’s model, occasional references to spaces of action, and visual space, as seen in the kunimi (land-viewing) poems by Emperor Meiji, aligning with Hoffman’s framework. Unsurprisingly, a frequently represented type is the “tuned space” (gestimmter Raum). This is achieved primarily through the use of toponyms—whether traditional meisho, or locations newly introduced to the waka poetic tradition—that evoke emotionally charged associations. These places are imbued with cultural and political significance, serving as collective memory sites[85] and symbols. Conversely, within the concise structure of a waka poem, substantial emphasis is placed on its atmospheric quality. In the context of utakai hajime, this atmosphere often evokes unity and celebration, which are frequently projected onto and expressed through natural elements.

In the analysis of utakai hajime poems below, I will first consider depictions of natural landscape with the use of toponyms, and then those without.

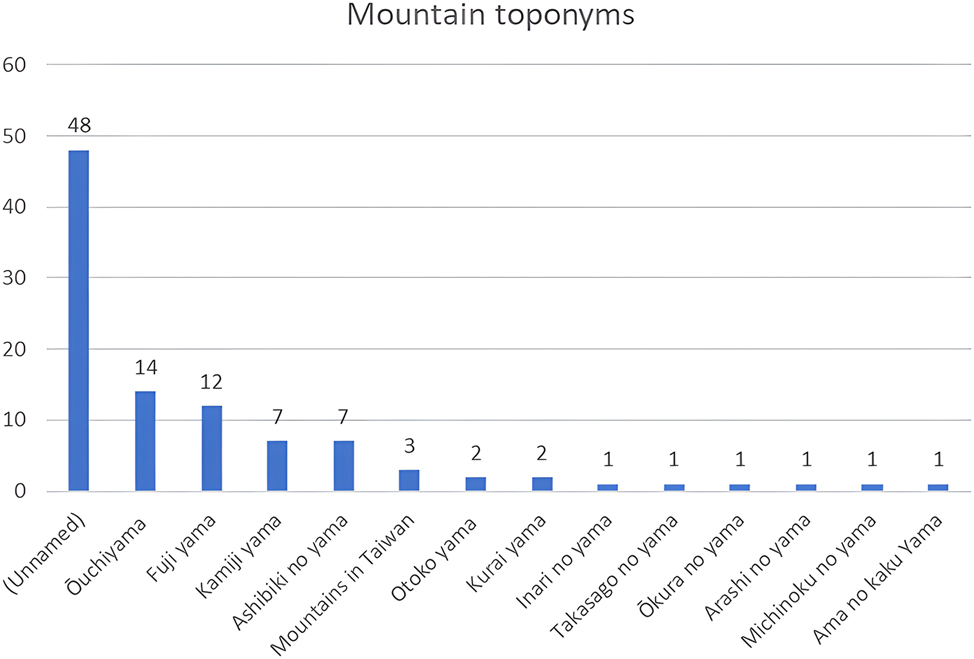

5 Literary Topography of an Ascending Empire

If one wishes to ascertain which role toponyms play in the literary cartography drawn by utakai hajime, it suffices to closely examine the frequency of appearance of different toponyms of mountains and rivers. For the former, about half of the 106 poems between 1880 and 1912 mentioning mountains do not contain any toponyms. However, among those that do, the most prominent place is occupied by ōuchiyama 大内山, the hills of the imperial palace, followed closely by Mt. Fuji 富士山 and Mt. Kamiji 神路山 (“of the path of gods”), near the Ise shrine. With the exception of three cases of allusions to mountains in newly incorporated Taiwan, the rest of the names seem to consist of classical topoi of waka poetic tradition, such as ashibiki no yama, otokoyama, michinoku no yama and so on (Figure 3).

Number of occurrences of mountain toponyms in utakai hajime poems, 1880–1912.

Let us consider some examples of poems referring to the hills of the imperial palace. In 1892, Kitanokōji Yorimitsu wrote the following waka to the imperial poetry theme of “sunrise over the mountain” 日出山:

sashinoboru [86]

ōuchiyama no

asahi kage

aogite mo shire

kuni no hikari o

The light of the morning sun

rising above the imperial palace hills —

as you look up to it,

you should bear witness

to the radiance of this land!

The poem represents one of the more chauvinistic examples of waka in the utakai hajime, as it implies that the splendour of the landscape imperial palace hills—and by extension, the imperial family—at sunrise is emblematic of the glory of Japan as a whole. Following Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), Princess Yasuko of Arisugawa 威仁親王妃慰子 (1864–1923) expanded this praise to imply that the imperial palace hills stir even people outside Japan to feelings of admiration, in a poem composed on the topic of “celebration with a mountain motif” 寄山祝:

haruka naru [87]

totsukuni hito mo

aoguramu

ōuchiyama no

takaki miitsu o

Even people

in far-distant lands

must be admiring

the great augustness

of the imperial palace hills!

The significance of the toponym Mt. Kamiji within the motif complex surrounding the tennōsei ideology becomes evident when one considers its status as an utamakura of the Ise region. Mt. Kamiji refers to a hilly area situated in the Isuzu River basin, just south of the Inner Shrine of Ise. As a poetic topos, it sometimes designates the Inner shrine of Ise and throughout waka history it appears in the deity poems (jingiuta 神祇歌) and celebratory poems (gaka 賀歌). Utakai hajime poems on Mt. Kamiji also contain congratulatory wishes in regards to the imperial reign, thus reinforcing the symbolic connection between the Inner Ise Shrine[88] and the imperial house. Consider this 1891 poem by Ōgimachi Saneatsu 正親町実徳 (1814–1896), on the topic of “praying for the Reign at the shrine” 社頭祈世:

kage takaki [89]

sakaki ni kakete

kamijiyama

kimi ga yachiyo o

inoru kyō kana

This is the day!

In front of the sakaki trees

on Mt. Kamiji,

we are praying that Your life

may last eight myriad years!

In the same year, the topos of Mt. Kamiji was also used in one of the selected poems, by Morikawa Yoritsugu 森川賴次 (n.d.), emphasizing a projected and harmonious national unity in celebration of the imperial reign, regardless of social class.

kimi ga yo o [90]

inoru kokoro ha

kamijiyama

takaki iyashiki

kawarazarikeri

The hearts praying

for your Life to last a thousand years

at the great Mt. Kamiji

are all the same,

be they of people high or low

In utakai hajime publications, poems referencing Mt. Fuji are few and far between, but their content is highly ideological, centring on the long-lasting, unalterable reign or on Japan as “the land of the rising sun.” Such a poem was even composed by Emperor Meiji in 1906, with the often occurring sunrise motif, which can also be taken for a symbol of Japan as “the land of the rising sun”.

fuji no ne ni [91]

niou asahi mo

kasumu made

toshi tatsu sora no

nodokanaru kana

The sky at the start of the New Year

is so calm

that the morning sun

glowing over Mount Fuji

seems hazy.[92]

In the year the Meiji Imperial Constitution was issued (1890), Kagawa Keizō 香川 敬三 (1839–1915) composed the following poem on the topic of “celebration with a country motif” 寄國祝. This is a good example of a poem praising the stability of the imperial dynasty through expressions such as ugokanu (literally ‘unmoved’, but in this context ‘unchanging’). This sense of stability is mirrored in the enduring permanence of natural geographical forms and further elevated by the implied majesty of the towering Mt. Fuji.

suruga naru [93]

fuji no takane ha

yorozuyo mo

ugokanu kuni no

shirushi naruramu

The high peak

of Mount Fuji

in Suruga

augurs a country unchanging

for ten thousand years.

The following poem by Wakana わかな (n.d.), daughter of Inoue Yoshiyuki 井上義行, composed in 1896 on the theme of “celebration with a mountain motif” 寄山祝, bears traces of the ideological lens of Meiji-period nationalism. Written in the aftermath of Japan’s victory in the First Sino-Japanese War, the poem extols Japan as a nation unparalleled in the world, exemplifying the heightened patriotic sentiment of the era. The poet‘s noteworthy admission that mountains taller than Mount Fuji do exist—a statement that imparts a distinctly modern tone, contrasting with the conventional sensibilities of waka poetics—stands in symmetry to her assertion of Japan’s global superiority. Thus, the poem may be taken to imply that both statements are equally true, in perpetuity.

hi no moto no [94]

ue ni tatsu beki

kuni zo naki

Fuji yori takaki

yama aredomo

There is no country

that can stand above

the [Land of the Rising] Sun,

even be there mountains

taller than Mount Fuji

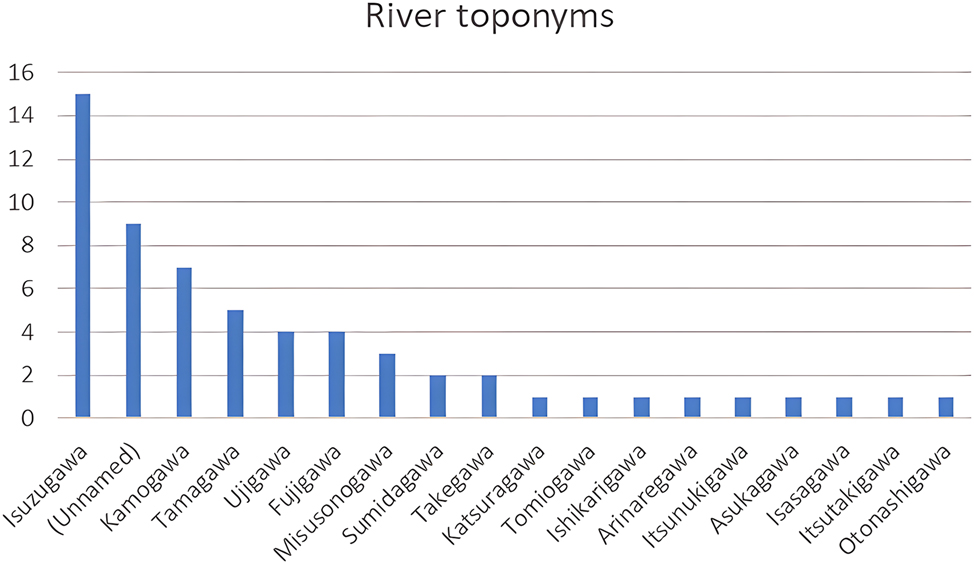

As mentioned above, the concept of “tuned space” (gestimmter Raum) applies when places and objects function primarily as atmospheric, symbolic, emotionally charged ‘carriers of expression.’ One such atmospheric and ideologically charged place is the Isuzu River 五十鈴川, which runs through the precincts of the Ise shrine associated with the imperial family. In two instances, the themes of utakai hajime referred to a river (1882: 河水久澄, 1906: 新年河). Among the sixty poems mentioning rivers, 15 reference the Isuzu River, and an additional three poems reference it by an alternative name, the Mimosuso River 御裳裾川, also an utamakura of the Ise province, together with the Take River 竹川 (Figure 4).[95]

Number of occurrences of river toponyms in utakai hajime poems, 1880–1912.

Let us examine poems containing river motifs in 1882. Of the five poems composed on the Isuzu River, the symbolic association with the imperial house varies from subtle to very explicit. While a common thread is given by the emphasis on continuity from an imagined age of the gods to the present, some poems also imply an equivalence between the river’s projected purity (its clear waters) and permanence with the same qualities belonging to the imperial reign. For instance, Emperor Meiji’s contributions to utakai hajime typically avoid overt nationalistic themes, focusing instead on aspirations for the future:

mukashi yori [96]

nagare taesenu

isuzugawa

nao yorozuyo mo

sumamu[97] to zo omou

I wish

that the Isuzu River,

which ceaselessly flows since ancient times,

would flow clearly

even ten thousand years more!

Chigusa Aritō’s 千種有任 (1836–1892) poem expresses the idea of temporal continuity mentioned above. It elevates the Isuzu River above all others by tracing its source back to the age of the kami, thus again underlining an implied sense of stability of the world:

Isuzugawa [98]

kiyoki nagare no

mizukami o

omoeba tooki

kamiyo narikeri

If you think

of the water source

of the clear-flowing Isuzu River,

it was in the distant

Age of the Gods.

The most explicit association of the river with the imperial house, however, with an innovative comparison between the purity of the river and that of the imperial line, appears in some of the selected poems, such as this poem by Isakawa Taketsuyo 砂川雄健 (n.d.) from Hyōgo Prefecture. The poem employs the figurative scheme of ‘elegant confusion’, a widely used rhetorical device in poetry of praise:[99]

chihayaburu [100]

kamiyo nagara ni

isuzugawa

sumeru ya miyo no

sugata naruramu

As it has been since the Age

of the mighty Gods,

is it the pure-flowing Isuzu River

which reflects

the purity of the imperial reign?[101]

The parallelism between the imperial reign and an endlessly flowing river is also apparent in poems on the Mimosuso River. In the 1882 poem by Empress Shōken, the radiance of the heavenly sun can be seen as a symbol for Emperor Meiji and a prosperous imperial reign that presumably keeps the river from becoming polluted. In this poem several classical tropes of waka poetry are present, such as kamikaze (‘divine wind’), a pillow word used to modify the place name Ise and things associated with it, such as the Mimosuso Stream, and associated words (engo) such as sue (‘ending’) and kawa (‘river’).

amatsuhi no [102]

terasan kagiri

kamikaze ya

mimosusogawa no

sue ha nigoraji

As long as the heavenly sun

is shining over it,

the downstream of the Mimosuso River,

of the Divine Wind,

will not grow polluted

6 Utakai hajime and the Expanding Empire

As mentioned above, toponyms can also be used to illustrate the expansion of the Japanese empire in the Meiji period. The following three examples include toponyms such as fortress names (given by the Japanese army in the Russo-Japanese War), allusions to mountains in Taiwan, or toponyms in Korea during the Russo-Japanese War or in the year following the annexation. For the first example, consider the following poem by Ōguchi Taiji, a member of Outadokoro. The poem was composed for the 1896 utakai hajime, on the topic of celebration with a mountain motif 寄山祝. While there is no toponym mentioned, the allusion to newly incorporated territories in Taiwan, which were ceded to Japan by China along with indemnities and reparations after the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), is very clear.

haruka naru [103]

minami no yama no

yorozuyo mo

waga ōkimi no

mite ni iriniki

The faraway southern mountains —

ten thousand years old,

have now passed

into Our Great Lord´s

August Hand

In this case, as with many waka poems because of their brevity, the meaning of the poem can only be derived by knowing the context in which it was written. The year 1896 provides an important clue, as it reveals that the utakai hajime took place shortly after Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War. Therefore, the ‘faraway southern mountains’ can be taken to be the mountains of Taiwan, now in the possession of the Emperor, ceded by China.

A type of shaping of the literary space that relies on geographic localization can also take place through the use of toponyms deviating from well-known topoi of the waka poetry tradition. Two poems refer to the Ishikari River in Hokkaidō and the Yalu River (Arinare River) on the border between Korean and Chinese territory in 1905, i.e. at the time of the Russo-Japanese War. In both cases, the rivers metonymically designate territories Japan acquired or absorbed in its sphere of influence throughout the Meiji period. As with other poems of the utakai hajime up to the end of the Shōwa period, the use of such toponyms serves to draw—in a literary plane—a new topography of the ascending empire. Consider the following poem by Takasaki Masakaze, 1906, on the topic of the “river at New Year’s” 新年河, which seems to imply that, as a result of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), the Yalu River on the border between Korea and China was purified by coming under the control of the Japanese Empire and thus the Imperial Family:

kotoshi yori [104]

amatsu manai o

kumiirete

arinaregawa mo

sumiwataruramu

From this year,

scooping water

from the heavenly (imperial) fountain

even the Yalu River

is likely flowing clear again.

This poem by Tanaka Mitsuaki 田中光顕 (1843–1939), composed in 1905 on the theme of “Mountains at New Year’s” 新年山, conveys a straightforward yet exuberant celebration of Japan’s victories in the war. It highlights the practice of renaming hills in Korean territory targeted during military campaigns, often referred to as kogane yama (Golden Mountain) or shirogane yama (Silver Mountain) by the Japanese army.[105]

yama no na no [106]

kogane shirogane

ōkimi no

mite ni irikeri

toshi no hajime ni

The mountains’

of gold and silver named

have passed into your grasp,

Your Majesty,

on this New Year’s beginning.

Finally, consider the following poem in 1911, by Xu Yan (?) 許焱 (n.d.) on the topic of “plum blossoms in the cold light of the wintry moon” 寒月照梅花. The poem draws attention to Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910 by both its paratextual information, which indicates that it was composed by a person with a Korean name, in Korean territory, and its content matter. The latter seems to imply that there is a unity already formed between Japan and Korea as the moon shines indistinguishably above both.[107]

yuki fukaki [108]

kudara no nobe ni

saku ume mo

hedatezu terasu

fuyu no yo no tsuki

in the deep-snow

plains of Kudara[109]

on the blossoming plum trees

the wintry night’s moon

is shining indistinguishably

Osamu Murai considers the text to be a ceremonial poem composed to fit the pretext of Japan’s annexation of Korea in response to a request from the Korean king. In his interpretation, the poem conveys a sense of celebration of Emperor Meiji´s rule by the residents of the colony. The toponym Kudara may have been deliberately chosen, as in the past, the Kudara region (or Jeolla-namdo) had a history of being strikingly anti-Japanese and anti-imperialist, as seen in the Donghak Peasant Revolution of 1894–1895. In Murai’s words, “the political effect of such a message is undeniable.”[110]

Up to this point, I have emphasized various aspects of nature’s depiction, including the solar symbolism linked to the intricate myths surrounding the imperial lineage. We have observed that nature scenery in utakai hajime poems often provides seemingly innocuous opportunities to foreground particular mythical and cultural toponyms. These toponyms are then ingrained in the collective cultural memory as symbols of special significance for the nation. For instance, while Ise evokes the Emperor’s descent from Amaterasu, Mt. Fuji had, by the Edo and Meiji periods, become a national symbol. Additionally, utakai hajime poems introduced new toponyms linked to the territorial conquests of the Meiji-era, either explicitly (Ishikari River, Yalu River) or through indirect allusions, such as mezurashiki yama referring to the mountains of Taiwan. Thus, while imperial poetry themes never directly reference contemporary political events, they nonetheless provide the opportunity for the composition of poems that subtly reflect the political and military agenda of the Meiji state. In the next section, I will examine the role of nature imagery tropes in the absence of toponyms.

7 Nature, Unity and the Imperial Reign

If one were to attempt a grouping of possible nature imagery in waka poems, there would be four categories resulting from this: firstly, nature as an expression of the poet’s personal feelings; secondly, nature presented in a neutral, aesthetically pleasing, descriptive manner. A striking function of nature imagery in utakai hajime poems is the third, its use to reference an imperial reign, either through comparison—between serene nature scenes and the imperial reign’s prosperity, for example—or by projecting a vision of harmonious unity in which nature itself celebrates the august rule. Such examples are no innovation of utakai hajime poets, but can sporadically be found already in the early history of waka poetry, such as in the Kokinshū’s book 7, “Felicitations”, as well as Book 7 of the Shinkokinshū with the same title. Finally, the fourth function consists of employing the depiction of natural landscapes as a pretext for introducing mythical or cultural topoi imbued with ideological significance. It is in this latter function, illustrated at length above, that utakai hajime reveals its most distinctive qualities, as we shall see below.

Let us examine several examples of the functions outlined above in the case of utakai hajime poems. Firstly, consider the following three poems, which use nature depiction as an expression of personal feelings. Koike Michiko 小池道子 (1845–1929),[111] a lady-in-waiting (naishinojō 掌侍) to Empress Shōken, 1909, on the topic of “pine tree in the snow” 雪中松:

furitsumoru [112]

yuki ni tawamanu

matsu o mite

oi mo samusa o

wasurekerukana

Seeing the pine tree,

unbending

while laden with snow,

I have forgotten

both the cold and my old age

Itō Eijirō 伊藤栄次郎 (n.d.), 1912, on the topic of “the crane atop the pine” 松上鶴: (a selected poem with no apparent connection to the imperial house or the Meiji government.)

ashitazu mo [113]

moto o wasurenu

kokoro yori

suedachishi matsu wa

taezu tōramu

The reed-dwelling crane,

never forgetting its roots,

finds his way back

to the pine where its nest once lay,

time and again

Ōya Hisako 大屋久子 (n.d.),[114] poetess of the Kyoto-based Keien school, 1911, on the topic of “plum blossoms in the cold light of the wintry moon” 寒月照梅花 (selected poem):

fuyugomoru [115]

hito no kokoro o

ugokashite

shimoyo no tsuki ni

niou ume kana

Is it the fragrant

plum blossoms,

in the night frost’s moon

which so move peoples’ hearts,

sequestered in winter?

Whereas Koike Michiko’s poem openly celebrates the speaker’s admiration for the pine tree—its unyielding dignity under the weight of snow, seemingly providing an inspiration for the poetess to similarly cast aside the burdens of her advanced age—the subsequent two poems employ nature imagery to evoke emotions ostensibly belonging to others, yet subtly reflective of the poet’s own inner experience. At first glance, the poems chosen here seem to exemplify motifs that are not as common as those seen in the above graphs, such as the moon. However, as the purpose here was to showcase poems that express personal feelings or musings, the overall intent of the poem was given precedence over the literary motifs.

Regarding the second function of descriptive portrayals of nature scenes, utakai hajime poems tend to emphasize nature imagery suggestive of plenitude and tranquility. The following three poems are good examples of such scenery, be they of cranes enjoying a peaceful sleep basked in the light of the sunrise (here, again, one could surmise an association between the sunrise and Japan as a prosperous country), or pines lush with greenery covering the earth beneath. Lastly, some poems use the trope of plants not waiting for spring to bloom, suggesting a feeling of prosperity.

Princess Yasuko, 1912, on the topic of “the crane atop the pine” 松上鶴:

sashinoboru [116]

asahi o ukete

yamamatsu no

kozue shizuka ni

tazu zo nebureru

In the mountains

basked in the light

of the rising sun

on the tops of pine trees

the cranes sleep peacefully

Chiba Taneaki, permanent Outadokoro member, 1904, on the topic of “pines atop the rock” 巖上松:

uruwashiku [117]

matsu koso shigere

arakane[118] no

tsuchi ha aridomo

mienu iwao ni

Because there are

so many pines

beautifully in full leaf,

though there is earth beneath them,

the rock cannot be seen.

Nagatani Nobunari 長谷信成 (1841–1921),[119] Outadokoro member who served in a variety of roles within the imperial household, 1902, on the topic of “plum blossoms at New Year’s” 新年梅:

haru matade [120]

nodokanaru yo ha

aratama no [121]

toshi no hajime ni

ume mo sakikeri

Not even waiting for spring,

In this tranquil world,

at the New Year’s begin

even the plum trees

have blossomed!

8 Nature Imagery and the Imperial Reign

This section examines the third function of nature imagery in utakai hajime poems: referencing the imperial reign through comparison and by projecting an idealized vision of harmonious unity, wherein nature is depicted celebrating the emperor’s rule. As noted earlier, many descriptive waka poems composed for the utakai hajime portray nature scenes imbued with prosperity, tranquility, or serenity. Moreover, as shown below, numerous poems explicitly attribute these favourable qualities to the well-governed imperial reign. In this context, the reign (miyo) is often portrayed as a pacifying force, bringing harmony to both nature and, by extension, the nation. The following two poems serve as striking examples of how the direct influence of the reign on nature can be depicted within the constraints of waka poetry.

Usami Suketsugu 宇佐美祐次 (1862–1947), politician, 1894, on the topic of “plum blossoms ahead of spring” 梅花先春:

ōmiyo no [122]

megumi o ukete

saku ume ha

haru no hikari mo

tanomazarikeri

Receiving the blessings

of this Great Imperial Reign,

the blossoming plum trees

did not even require

the light of spring.

Nabeshima Naohiro, distinguished aristocrat with close ties to the imperial family, 1893, on the topic of “turtles on the rock” 巖上龜:

ugokinaki [123]

iwao no ue ni

uchimurete

kame mo nodoka ni

asobu miyo kana

Atop

the immovable rock,

the turtles gathering

also play tranquilly –

such an Imperial Reign it is!

In some cases, such as in the year 1883, when the poetry topic was “the clear four seas” 四海清—where shikai 四海 can also mean ‘world’ or ‘everything under heaven,’ the supposedly beneficial effects of the imperial reign are portrayed as extending even beyond Japan, such as in the following poem by Nabeshima Naohiro:

yomo no umi [124]

yashima no soto mo

ōkimi no

fukaki megumi o

aogu miyo kana

Even [in the world] outside Japan,

across the seas in all four directions,

the Imperial Reign

imparts rich blessings

of Our Great Lord!

The same year, Tokudaiji Sanetsune, Grand Chamberlain to Emperor Meiji and later Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, wrote a similar poem:

azusayumi [125]

yashima no soto mo

namikaze no

osamaru miyo ni

ahinikeru kana

Even outside Japan,

the Imperial Reign

which pacifies waves and winds

is encountered

In this poem, the lexeme azusayumi—which is often translated as “catalpa bow’’—is a makura kotoba for the first syllable ya (which also means ‘‘arrow”), from Yashima, an old, lyrical name for Japan. The verb osamaru can be taken to mean both to pacify and to rule, and the lexeme namikaze—“waves and winds’’—is known to also symbolize strife in the world, as in Emperor Meiji’s famous yomo no umi poem of 1904. Considering this additional layer of meaning, the poem seems to imply that the Imperial rule serves to uphold peace not just in Japan, but even in the world beyond.

In addition to the supposedly beneficial effects of Imperial rule on nature, the panegyric poems of the utakai hajime as a whole portray the relationship between the Imperial rule and nature as symbiotic and reciprocal, with elements of nature often depicted as celebrating Imperial rule. The following poems provide a glimpse of this projected reciprocal affection, whether in heightened political times such as the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), or in the more mundane context of peaceful times. For example, in this poem by Outadokoro member and viscount Takeya Mitsuaki 光昭竹屋 (1837–1901) from 1905, on the topic of “mountain at New Year’s” 新年山, the mountains are shown to celebrate the Imperial reign together with the people:

kimi ga yo o [126]

yachiyo to utau

kunitami ni

yama mo kotaete

toshi tachinikeri

To the country’s people singing,

“may Your Reign

last eight myriads!”

the mountains, too, reply.

New Year has come!

This poem by Empress Shōken, in 1912, on the topic of “the crane atop the pines” 松上鶴, shows that the customary wishes of long life are not only found in the poems of courtiers, but are also attributed to the cries of young cranes.

sugomori no [127]

hina no chiyo o mo

sasagu to ya

mikaki no matsu ni

tazu no nakuramu

Does the crane in the pines,

beside the sacred fence,

call out,

that its nestlings are raising their voices

in the wish for Your Reign to endure forever?

In the politician Ōhara Shigetomo’s poem of 1900, on the same topic of “the crane atop the pines”, the cranes’ supposed wish for the Imperial reign to continue to prosper trickles down to the realm of their dreams.

ōniwa no [128]

matsu ni nebureru

ashitazu ha

sakayuku miyo no

yume ya miruramu

Sleeping in the pines

of the great courtyard,

are the cranes

dreaming of the Imperial Reign

flourishing more and more?

In numerous poems that incorporate nature in the context of Imperial reign, nature imagery serves to symbolize the reign’s (miyo) revered qualities: its enduring permanence, virtuousness, stability, and tranquillity. Such comparisons are emphasized by means of expressions such as kagami (2 times), sugata (7 times), shirushi (12 times). Consider the poem by Isakawa Taketsuyo on the Isuzu River above, as well as the following poems:

Court lady Uematsu Chikako 植松務子 (n.d.), 1881, on the topic of the “bamboo’s splendid color” 竹有佳色:

monono u no [129]

ya ni hakinareshi

kuretake mo

chiyo no irosou

kimi ga miyo kana

Like the dark bamboo,

well accustomed to being worn

as the warrior’s arrow,

grows deeper in colour over thousands of generations,

so does My Lord’s Reign [grow profounder]!

Princess Toshiko Sadanaru 貞愛親王妃利 (1858–1927), 1884, on the topic of “cranes in a sunny sky” 晴天鶴:

yutakanaru [130]

miyo no sakae mo

miyuru kana

haretaru sora ni

asobu tazumura

The glory

of this bountiful reign

is seen in the flocks of cranes

frolicking

in the clear sky!

Prince Yamashina Akira 山階宮晃親王 (1816–1898), 1887, on the topic of “the tranquil waves in the pond” 池水波静:

akirakeki [131]

miyo no kagami to

ikemizu no

nami mo ugokanu

kaze no nodekesa

The gentleness of this breeze

which does not even stir

ripples in the pond water

seems like a mirror

of the brilliant Imperial Reign!

While Uematsu Michiko’s poem employs a metaphor of growth—bamboo darkening to symbolize the deepening of an intrinsic quality—Princess Toshiko and Prince Akira’s verses evoke natural imagery to highlight the Imperial Reign’s supposed joyfulness and tranquillity.

In sum, the utakai hajime poems examined here reveal a seemingly intertwined relationship between nature and imperial rule, in which natural imagery serves as a medium for extolling the virtues of rule. Through depictions of prosperity, harmony and tranquillity, these poems construct an idealised vision of a well-governed empire, occasionally even extending the supposed influence of the ‘benevolent’ Imperial rule beyond Japan’s borders. Furthermore, the Imperial rule is presented as both a pacifying force and the subject of nature’s celebratory response. Through the use of specific poetic devices, ranging from meisho and the introduction of new toponyms to comparisons and classical tropes such as makura kotoba and engo, the utakai hajime poems reinforce this portrayal in a mixture of classical Japanese aesthetics of the banquet poetry with modern panegyrical techniques that seem to have been conceived through the ideological lens of the Meiji period. The following concluding section follows up on the initial question of this article with regards to the wider reception of utakai hajime as a national event.

9 Reception of utakai hajime Imperial Poetry Themes in Meiji-era Media