Abstract

In this study, we provide a replicable language-anchored framework for capturing expressions of sympathy in interaction, by contrasting Chinese and English sympathising behaviour. Our framework combines interaction ritual and speech acts, and it captures sympathising without associating it with one particular speech act from the outset. Methodologically, we follow a tripartite design: First we identify puzzlements which ritual sympathising can trigger for Chinese expatriates living in the US and American expatriates in China. We then conduct Discourse Completion Tests (DCTs) to identify conventions of sympathising in the two linguacultures. Finally, we interpret our expatriates’ puzzlement through the outcomes of the DCT analysis.

1 Introduction

In this paper, we present a replicable framework for capturing expressions of sympathy in situations of distress – a universally important phenomenon. Sympathising is of particular interest for two reasons: Firstly, from a methodological perspective, it is rewarding to explore realisations of sympathising in a language-based, non-psychological way. Secondly, social groups use many interaction rituals (Goffman 1967) for expressing sympathy, so it is important to contrast realisations of sympathising across different linguacultures, in particular typologically distant ones.

We examine how speakers of Chinese and English express sympathy in comparable situations of increasing gravity. Furthermore, we consider whether realisations of sympathising trigger intercultural puzzlement for expatriates in China and the US, and, if yes, whether such irritations can be explained from a pragmatic rather than psychological angle. Our study follows a tripartite and strictly linguistically-anchored design.

Section 2 is a review of literature, Section 3 presents our framework, Section 4 provides our analysis, and finally Section 5 concludes this paper.

2 Review of literature

Sympathy has been widely studied in psychology (e.g. Clark 1997; Wuthnow 2012), often together with empathy. Yet, psychological notions are notoriously difficult to capture with the inventory of pragmatics. This also applies to cross-cultural psychology. While scholars like Kitayama and Markus (2000), and Koopmann-Holm and Tsai (2014) have examined cross-cultural realisations of sympathy, their research builds on pre-fixed cultural values that determine people’s behaviour. This view is very different from cross-cultural pragmatic approaches (House and Kádár 2021a).

In pragmatics, sympathy has received significant attention following Leech’s (1983) seminal work. According to Leech’s Maxim of Sympathy, one should “(a) Minimize antipathy between self and other, (b) Maximize sympathy between self and other.” (Leech 1983: 81–82). This view influenced research on politeness rather than sympathise per se (e.g. Eisenchlas 2012). Sympathise also emerged in research on the speech act Apologise (see Blum-Kulka et al. 1989). However, it was in the 2000s that sympathising attracted the interest of pragmaticians who approached it primarily in a psychologically-motivated way. E.g. García (2010) examined ‘identity’ and ‘respectability face’ in acts of sympathising, which are psychological concepts, revealing little about the actual linguistic realisation of sympathy. The same applies to Jing-Schmidt and Jing (2011), Sheikhan (2017) and others. Our study is more closely aligned with recent language-based pragmatic studies on sympathising, including Alabi (2022) and Wang et al. (2023). However, we take one step further by proposing a pragmatic framework, bringing together ritual and speech acts through which sympathising can be captured in a replicable way. We revisit Leech’s thought (e.g. Leech 1983: 132–3) who argued that Maxims such as Sympathy are realised by different illocutions in different situations.

The linguacultural variation of sympathising has attracted the attention of cross-cultural pragmaticians, many of whom used Discourse Completion Tests (DCTs) for eliciting data. For example, Nakajima (2002) compared English and Japanese realisations of the speech act Sympathise, Nguyen (2016) examined English and Vietnamese sympathy expressions, and Peneva (2020) studied English and Bulgarian condolence expressions. Although we also use DCTs (see more below), we do not associate symphatising with one particular speech act.

In cross-cultural pragmatics, sympathising has often been associated exclusively with condolence. There is a large body of such research, including Elwood (2004), Pishghadam and Moghaddam (2012), Kongo and Gyasi (2015), and Meiners (2017). We believe that separating condoling from the broader ritual phenomenon of expressing sympathy is problematic because while expressing condolence represents the most formalised manifestation of sympathy rituals due to the gravity of death, it clearly belongs to a cluster of sympathise rituals. This is why we focus on both condolence and other less grave sympathising rituals.

Our research is also relevant for the study of sympathy in Chinese, including Wang et al. (2023), as well as Zhou (2016), Zhao and Zhang (2018) and Jing and Du (2020).

3 Methodology and data

3.1 Methodology

We approach expressing sympathy as an interaction ritual. Following Goffman (1967) and Kádár (2017), we define ritual as a phenomenon which operates with conventionalised pragmatic patterns, has a strong social meaning, triggers a frame and self-display, and correlates with – and reinforces – rights and obligations and the related interactional and moral order. This definition implies that ritual not only encompasses ceremonies but also other forms of interactional behaviour which may not be defined as ‘ritual’ in lay terms. This definition allows us to capture sympathising without focusing on only one of its realisation patterns. Since the expression of sympathy is a globally important phenomenon, we believe that it is problematic to associate it with a particular speech act because such an association precludes investigating data drawn from different linguacultures in a bottom-up way.

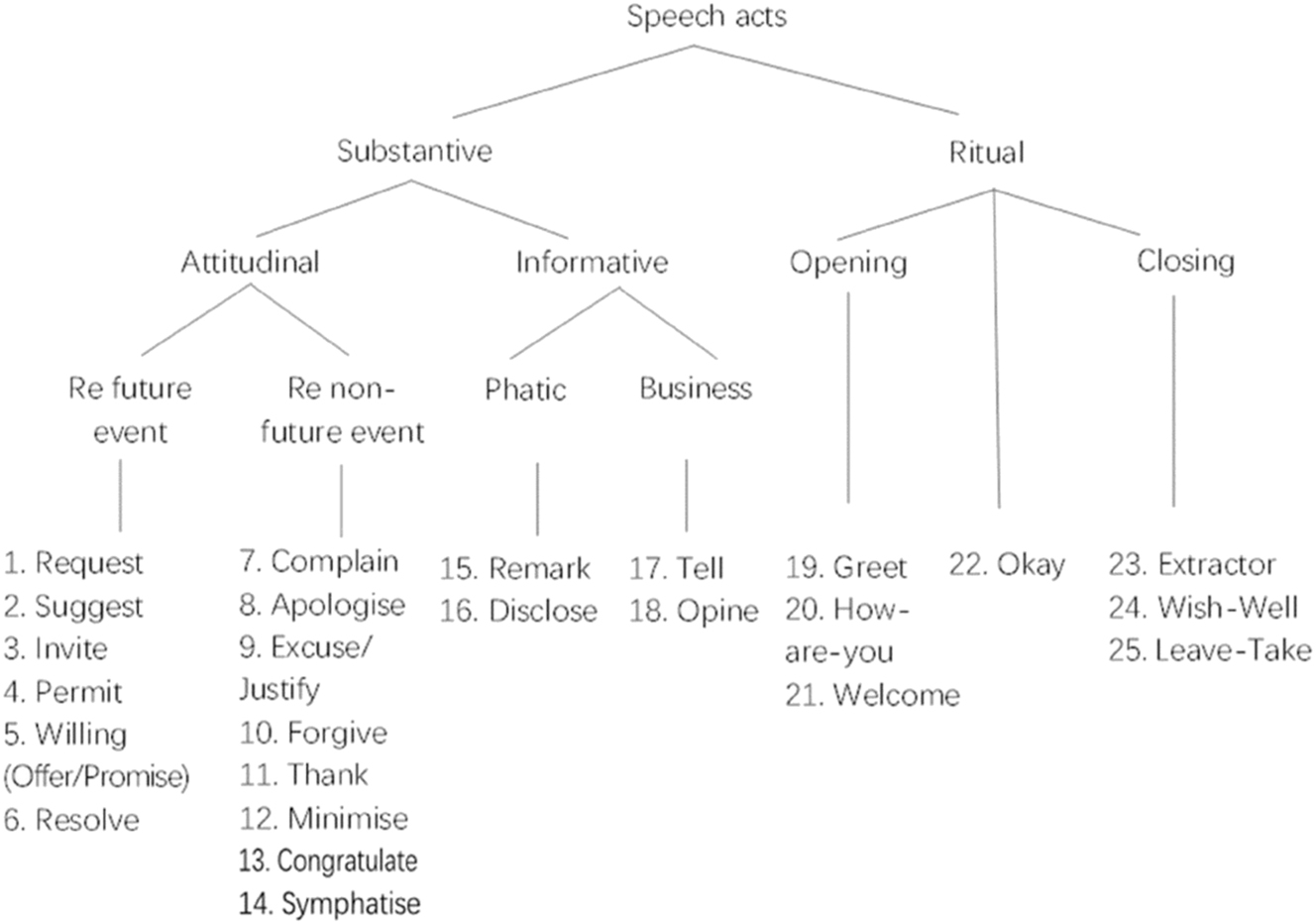

We break down realisations of sympathising into replicable speech act components, relying on a finite speech act typology (Edmondson and House 1981; Edmondson et al. 2023). Figure 1 below presents our speech act typology:

Our speech act typology (Edmondson and House 1981; Edmondson et al. 2023).

Having a finite typology of speech acts allows us to rigorously analyse and compare speech acts through which ritual sympathising is realised in the linguacultures under investigation. Ever since Austin and Searle, the idea that speech act categories need to be finite has been present in pragmatics (Habermas 1979; Kissine 2013; Levinson 2017; Vanderveken 1990). The idea of finiteness precludes ‘discovering’ new and culturally-specific speech acts. The speech acts we propose are such simple and basic constituents of language use that they can easily be replicated in the study of interaction across languages and datatypes (see also House and Kádár 2023).

Following our bottom-up take, we do not assume that ritual sympathising only includes realisations of Sympathise in a particular linguacultural context. Rather, we investigate which speech act types – and formulae through which they are indicated – are frequented in different contexts of symphathising. In terms of our typology, ritual sympathising typically triggers Attitudinal and non-future-event-related speech acts. Yet, we do not assume that it only triggers such speech acts, i.e. we also consider other speech acts which ‘migrate’ into such an Attitudinal and non-future-event-related role in ritual sympathising (House and Kádár 2021b).

We are interested in how speakers of Chinese and English express sympathy in the following three situations of increasing gravity: (1) Suffering financial loss due to being scammed → (2) Suffering from a serious illness → (3) Losing a loved one. Our study follows a tripartite design:

Following our interest in realisations of sympathising in Chinese and English, we interviewed five US expatriates living in China and five Chinese expatriates in the US about how they judge expressions of this ritual act in the foreign country where they live. Our participants were professionals working in the target country for at least five years and they were advanced speakers of the target language. To understand their perceptions of symphatising in various situations in their target linguaculture, we asked our respondents to either report on their own experience or imagine what Chinese/American language users would say in the above three situations of increasing gravity. We then categorised our respondents’ metapragmatic accounts.

We then conducted DCTs with a group of 20 advanced Chinese learners of English and 20 English-speaking learners of Chinese, to obtain comparable realisations of sympathising. The DCT design also allowed us to systematically involve the conventional sociolinguistic variables of power [+/–P] and social distance [+/–SD].

Finally, we interpreted the views expressed in the initial interviews through the outcomes of our DCT analysis. This allowed us to capture what puzzled our interviewees through pragmatic evidence.

We are aware of the criticisms of eliciting data through a DCT. However, as House and Kádár (2021a) pointed out, the DCT approach remains a useful method for data collection. This is particularly the case if one’s goal is to study and compare realisations of phenomena such as ritual sympathising in different linguacultures, which a tightly controlled DCT methodology optimally facilitates. We are also aware of the fact that our data is somewhat limited in size. However, since it was already difficult to find advanced speakers of Chinese for our study, we decided to operate with a dataset of the current size.

3.2 Data

Our initial interviews were conducted in English, lasting 15 min on average. We duly anonymised our data. We presented the following DCTs to our participants who were all advanced university students:

Scenario 1: Scam incident

| Your friend has suffered serious financial loss through being scammed. What would you say to her? | [–P,–SD] |

| Your friend’s friend… | [–P,+SD] |

| Your MA/PhD supervisor… | [+P,–SD] |

| An academic whom your barely know… | [+P,+SD] |

Scenario 2: Serious illness

| You friend has been diagnosed with a serious illness. What would you say to her? | [–P,–SD] |

| Your friend’s friend… | [–P,+SD] |

| Your MA/PhD supervisor… | [+P,–SD] |

| An academic whom your barely know… | [+P,+SD] |

Scenario 3: Death

| Your friend lost a close relative. What would you say to her? | [–P,–SD] |

| Your friend’s friend… | [–P,+SD] |

| Your MA/PhD supervisor… | [+P,–SD] |

| An academic whom your barely know… | [+P,+SD] |

We capitalise speech acts, while broader interactional phenomena are indicated in non-capital. For example, we distinguish symphatising as an interactional ritual from the speech act Sympathise.

4 Analysis

4.1 Phase one: initial interviews

Table 1 overviews the outcomes of our interviews:

Perceptions of sympathising by Chinese and American expatriates.

| American expatriates | Chinese expatriates |

|---|---|

| Scenario 1: Scam | |

|

|

|

| – 4 out of 5: The Chinese do not express sympathy in a ‘Western’ sense because they put the onus on the victim. – 4 out of 5: The Chinese prefer to immediately give general ‘philosophical’ suggestions instead of consoling first. – 3 out of 5: At the same time, the Chinese are ready to offer help. |

– 5 out of 5: The Americans are ‘robotic and cold’. – 3 out of 5: The Americans do not offer advice as to how to overcome the problematic situation. – 4 out of 5: English language does not have ‘proper’ expressions for consoling the other. |

|

|

|

| Scenario 2: Illness | |

|

|

|

| – 5 out of 5: The Chinese do not express sympathy in a ‘Western’ sense but rather give ‘advice’. – 4 out of 5: The Chinese love vague expressions. |

– 4 out of 5: The Americans are ‘robotic and cold’. – 3 out of 5: The Americans rarely express a positive attitude for the other’s recovery. |

|

|

|

| Scenario 3: Death | |

|

|

|

| – 4 out of 5: The Chinese have no ‘real’ condolence expressions but rather use ‘archaic Asian’ wisdoms. – 3 out of 5: The Chinese love to provide redundant advice, such as ‘take care’, when the actual problem is more serious. |

– 5 out of 5: The Americans use ‘sorry for’ to express condolence; this is too ‘superficial’. – 3 out of 5: The Americans are nicely emotive, even though their manner of speech seems to be ‘alien’. |

Due to space limitation, we only provide representative extracts from our interviews, featuring one example of each situation.

| I was scammed in China a couple of times […] and when complaining to Chinese colleagues they seemed to blame me for being naïve. |

This excerpt illustrates the opinion that the Chinese do not sympathise in a ‘Western’ sense because they put the onus on the victim.

| Very strangely, they [i.e. the Chinese] do not say ‘sorry’ for your situation. … When I was ill in China, I don’t remember my Chinese friends saying ‘sorry’ for my situation. |

This excerpt illustrates the opinion that the Chinese do not express sympathy in a ‘Western’ sense when someone falls ill.

| Don’t expect the Chinese to say emotive things like “sorry for your loss”. Don’t get me wrong, the Chinese are very emotive, but they don’t really say things like we do in English, and surely you also say in [reference to Kádár’s native tongue]. |

This is a typical reflection of the American opinion that the Chinese do not have ‘real’ condolence expressions.

| The Americans seem to not be real in what they say … I would rather expect them to care about my feelings in such a case. |

This excerpt illustrates the Chinese perception that the Americans are ‘robotic and cold’.

| When I was in hospital, my American friend visited me and he was very nice, but I rather missed the kind words that Chinese friends would always tell you. The Americans are rather robotic, and you do not experience the genuine warmth you need. |

This reflection again illustrates the perception that the Americans are ‘robotic and cold’.

| I lost a close relative during Covid and got condolences from my American friend. To be honest, you always have to tune yourself to the American way of behaving. They say ‘sorry’ when they step on your foot and they also say ‘sorry’ when someone died, which is difficult to understand. |

Finally, this reflection points to the perception that the Americans use the expression ‘sorry for’ expressing condolence; this is often problematic for Chinese speakers who regard it as ‘shallow and ‘superficial’.

4.2 Phase two: DCTs

4.2.1 Consoling the other for being scammed (Chinese)

Table 2 shows the different speech acts across various role relationships:

Speech act types in various role relationships when consoling the other for being scammed (Chinese).

| Opine | Suggest | Willing (Offer) | Symphatise | Request (for information) | |

| [–P,–SD] | 14 | 17 | 9 | 3 | 2 |

| [–P,+SD] | 19 | 15 | 1 | 2 | - |

| [+P,–SD] | 16 (9 formal) | 11 (7 formal) | 12 | - | 2 |

| [+P,+SD] | 18 (6 formal) | 6 (5 formal) | 1 | - | - |

| Total | 67 | 49 | 23 | 5 | 4 |

In this scenario, the most frequent speech act is Opine, through which information is communicated in a ‘subjective’ way. In all role relationships, our respondents realised ritualised Opines:

| 哎呀, 现在的诈骗案件非常多, 真是防不胜防, 你也别太上火, 会想到办法解决的。 | |||||||

| Oh, there are so many scam incidents these days, one really can’t defend oneself from them, don’t be too mad, there should be a way to resolve this. | |||||||

| Opine | / | Opine | / | Suggest | / | Opine | [–P,–SD] |

| 他们的话术确实厉害, 真是很难避免啊。 | |||

| Their [the scammers’] persuasive skills are impressive: it’s difficult to avoid this. | |||

| Opine | / | Opine | [–P,+SD] |

| 他们确实在这方面太专业了, 也许警方会把损失追回来。 | |||

| They [the scammers] are really good in this thing, maybe the police will help you get your money back. | |||

| Opine | / | Opine | [+P,–SD] |

| 连老师都被骗了, 可见现在的诈骗分子诡计多端, 太狡猾了, 还真是得时刻提高警惕啊。 | |||||

| Even teachers get scammed, clearly these fraudsters are devious and cunning. One really needs to be vigilant all the time. | |||||

| Opine | / | Opine | / | Opine | [+P,+SD] |

Such Opines are ritual because our participants only expressed social meanings by stating the obvious, often in a manner as if they were ‘congratulating’ the scammer. The function of this ritually realised speech act is to assure the recipient that the speaker is aware of the difficulty of the situation.

Idioms are also used to express sympathy, typically embedded in Opines in [+P] relationships:

| 老师, 您最近状况还好吧? 留得青山在, 不愁没柴烧, 钱丢了咱还能再挣, 您别太心急。 | |||||||

| Teacher, are you all right after this? While the green hills continue exist there’ll be wood to burn. If you lose money, you can earn it again. Don’t be too impatient. | |||||||

| Request (for information) | / | Opine | / | Opine | / | Suggest | [+P,–SD] |

| 请您保重身体, 不要太担心, 破财免灾。 | |||||

| Please take good care, don’t worry too much, a financial loss may prevent a larger disaster. | |||||

| Suggest | / | Suggest | / | Opine | [+P,–SD] |

In (11), our respondent used the idiomatic phrase liude-qingshan-zai, buchou-mei-chaishao 留得青山在, 不愁没柴烧 (‘while the green hills continue exist there’ll be wood to burn’),[1] while in (12) the idiom pocai-mianzai 破财免灾 (‘a financial loss may prevent a larger disaster’) is used. These expressions have a ritual role as they express something obvious and as such have a much stronger social rather than referential meaning.

The second most frequent speech act is Suggest, an illocution in which “a speaker communicates that he is in favour of H’s performing a future action as in H’s own interests” (Edmondson et al. 2023: 126). Suggest has two major realisation types in our dataset:

1. In [–P] settings, it encompasses illocutions through which the other is suggested to contact the police urgently:

| 咱们报警!如果有经济需要, 随时联系! | |||

| We should report it to the police! If you need any financial assistance, let me know anytime! | |||

| Suggest | / | Willing (Offer) | [–P,–SD] |

Considering that our DCT features a scenario where the participants are informed about the scam event after it occurred, such realisations of Suggest are clearly ritual, i.e. their role is mainly to express the speaker’s care for the other.

In [+P] settings, our participants also frequented Opines realised with formulae to ritually express sympathy. For instance, in (11) our respondent used the formula nin-bie-tai-xinji 您别太心急 (‘you [V pronoun] should not be too impatient’) as a ritual and deferential ‘advice’.

As Table 2 shows, the speech act Willing (Offer) is frequented in the [–P,–SD] and [+P,–SD] scenarios. This tendency indicates that this speech act is less conventionalised than Opine and Suggest which occur in all role relationships: our respondents only offered help to those whom they actually intended to help. Extract (13) has already illustrated a Willing (Offer) realisation in a [–P,–SD] response, while (14) features the [+P,–SD] setting:

| 老师, 您报警了吗? 有任何需要, 您随时联系我。 | |||

| Teacher, did you report it to the police? If I can help in anything, please contact me anytime. | |||

| Request (for information) | / | Willing (Offer) | [+P,–SD] |

(14) also includes a Request (for information), which – similar to Willing (Offer) – may not be part of the regular repertoire of the ritual: such inquiries about whether legal action has been taken – rather than providing symbolic suggestions – may reflect genuine interest.

The speech act Sympathise occurs in our Chinese dataset infrequently and only in [–P] settings:

| 真为你感到难过, 希望你吸取教训。 | |||

| I really feel sorry for you, I hope you will learn from this situation. | |||

| Symphatise | / | Suggest | [–P,–SD] |

4.2.2 Consoling the other for being scammed (English)

Table 3 shows the different speech acts across various role relationships:

Speech acts in various role relationships when consoling the other for being scammed (English).

| Sympathise | Opine | Willing (Offer) | Request (for information) | |

| [–P,–SD] | 22 (19 formal) | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| [–P,+SD] | 20 (20 formal) | 13 | 2 | 4 |

| [+P,–SD] | 24 (20 formal) | 5 | 12 | 8 |

| [+P,+SD] | 20 (20 formal) | 14 | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 86 | 42 | 27 | 25 |

In our English DCTs, by far the most frequent speech act is Sympathise, often realised with the expression ‘I’m/am sorry [for/to]’:

| The bastards! I’m really sorry for what you are going through now. | |||

| Opine | / | Sympathise | [–P,–SD] |

| Oh no! I’m so sorry. People are getting crazy these days. | |||

| Sympathise | / | Opine | [–P,+SD] |

| Dr. X, I am so very sorry to hear this. | |

| Sympathise | [+P,–SD] |

| I’m really sorry to hear this. This is really disturbing news. | |||

| Sympathise | / | Opine | [+P,+SD] |

In [–SD] scenarios, various respondents also used non-formulaic Sympathise expressions:

| I am very sorry, mate. This is genuinely bad. Can I help with anything? | |||||

| Sympathise | / | Sympathise | / | Willing (Offer) | [–P,–SD] |

| Ah, Prof. Doe, I am so sorry for you. This is just hideously unfair to you. | |||

| Sympathise | / | Sympathise | [+P,–SD] |

The frequency of Sympathise in our English DCT shows that this speech act is practically compulsory here and therefore is also ritualised.

Opine is also ritualised in our English dataset: it encompasses negative moralising opinions about the state of the world where scamming occurs, hence boosting sympathy. Opine is frequented particularly in [+SD] settings where Willing (Offer) rarely occurs, and so it is likely that it helps the speaker to express sympathy without committing herself to act.

Willing (Offer) occurs mostly in [–SD] relationships (see (20)), i.e. this speech act tends to be realised in situations where the speaker actually means that she is ready to help the recipient. Similarly, Request (for information) is also frequented in [–SD] relationships where the speaker is willing to get involved:

| Doctor, I’m very sorry, this is horrible. May I ask exactly what happened? Can I do anything for you? | |||||||

| Sympathise | / | Sympathise | / | Request (for information) | / | Willing (Offer) | [+P,–SD] |

4.2.3 Contrastive analysis and discussion of the findings

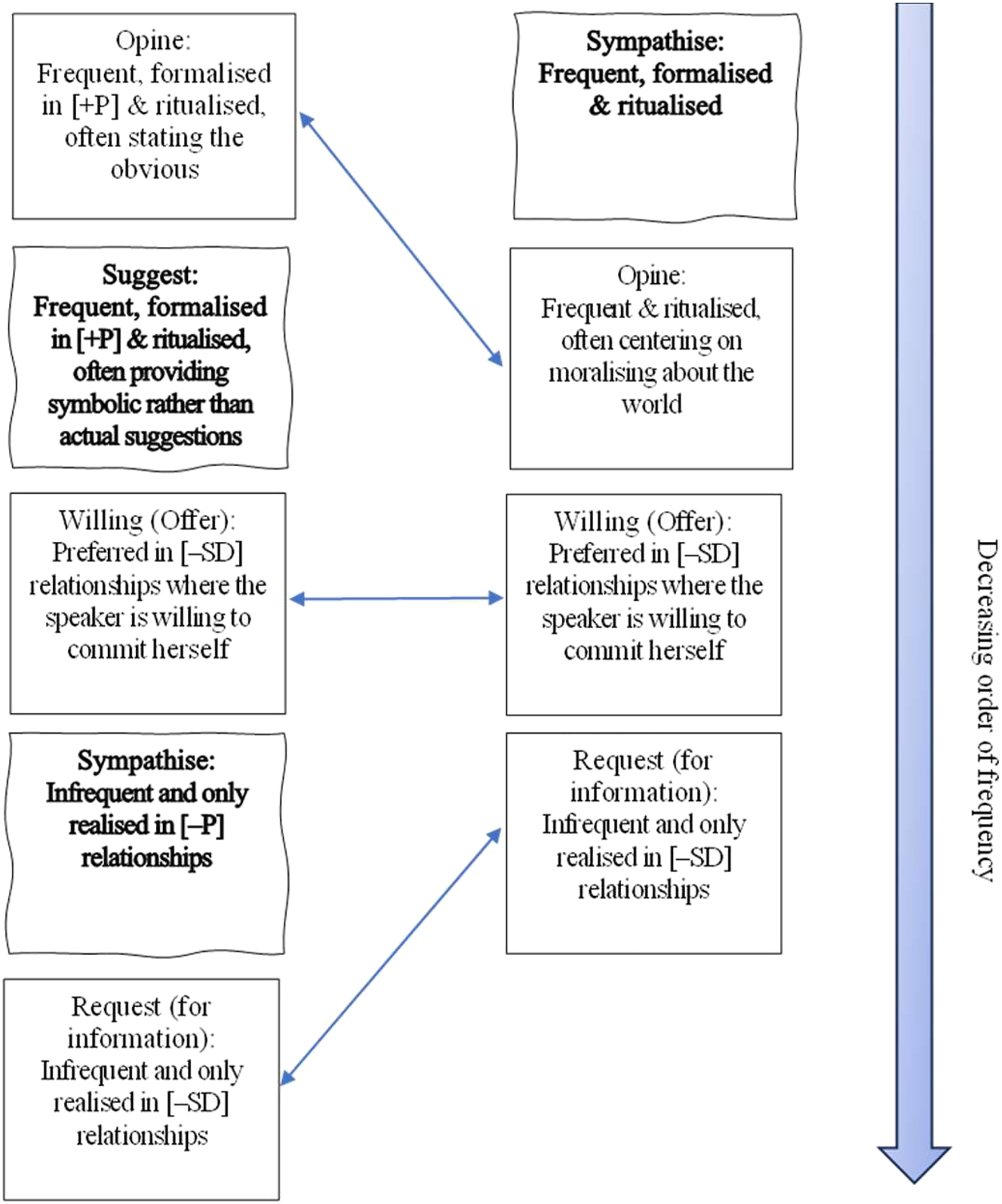

Figure 2 summarises the similarities and differences between our Chinese and English DCT datasets:

Contrastive analysis of speech acts frequented in consoling the other for being scammed in Chinese and English.

As the double-headed arrows show, Chinese and English realisations of consoling the other for being scammed have various pragmatic similarities: in both linguacultures, Opine, Willing (Offer) and Request (for information) are frequented, and their realisation patterns show resemblances. However, such similarities are eclipsed if one considers the pragmatic differences illustrated with highlighted boxes:

The frequency and ritualised nature of Suggest in Chinese, in particularly in [+P] scenarios, which is totally absent in the English data; and

The frequency and ritualised nature of Sympathise in English, which is infrequent in Chinese.

4.2.4 Consoling the other for falling seriously ill (Chinese)

Table 4 shows the different speech acts across various role relationships:

Speech acts in various role relationships when consoling the other for falling seriously ill (Chinese).

| Wish-Well | Suggest | Willing (Offer) | Request (for information) | Symphatise | Tell | |

| [–P,–SD] | 10 (10 formal) | 9 (9 formal) | 11 | − | − | − |

| [–P,+SD] | 12 (12 formal) | 5 (5 formal) | − | − | 4 | − |

| [+P,–SD] | 13 (13 formal) | 12 (12 formal) | 14 | 4 | − | 2 |

| [+P,+SD] | 12 (12 formal) | 10 (14 formal) | − | 4 | 1 | − |

| Total | 47 | 36 | 25 | 8 | 5 | 2 |

As Table 4 illustrates, the most frequent speech act here is Wish-Well, through which “a speaker expresses his positive attitude towards his hearer by ‘wishing him well’ for the future” (Edmondson et al. 2023: 185). In cases of illness, Wish-Well involves a positive attitude towards the other’s recovering. In our Chinese data, Wish-Well tends to be realised with formulae in all relationships:

| 祝你战胜病魔, 早日康复!多多保重。 | |||||

| Wish you will defeat the evil of illness and get back to normal! Take good care of yourself. | |||||

| Wish-Well | / | Wish-Well | / | Suggest | [–P,–SD] |

| 希望你早日康复, 保重! | |||

| I hope you will become healthy soon, take care of yourself! | |||

| Wish-Well | / | Suggest | [–P,+SD] |

| 老师, 您最近身体还好吗? 我想去探望您一下, 希望您能早日康复。 | |||||

| Teacher, are you feeling well, lately? I would like to visit you, I really hope you will be healthy again soon. | |||||

| Request (for information) | / | Tell | / | Wish-well | [+P,–SD] |

| 老师, 惊悉您最近身体不适, 希望您早日康复。 | |||

| Teacher, I’m devastated that you do not feel lately, I hope you return to be healthy soon. | |||

| Symphatise | / | Wish-well | [+P,–SD] |

The most typical Wish-Well is zaori-kangfu 早日康复 (lit. ‘turn healthy early’), although various participants also used other pragmatic solutions like zhu-ni zhansheng-binggui 祝你战胜病魔 (lit. ‘I hope you defeat the devil of illness’).

Suggest is another speech act used ritually, with the formula baozhong 保重 (lit. ‘guard your dear health’) and its variants, often in combination with Wish-Well, as extracts (23) and (24) illustrated. In [–P] relationships, two of our participants provided less conventionalised formulaic Suggests:

| 太可惜了, 不过现在治疗方法都很成熟, 不要太担心, 一定要乐观。 | |||||||

| This is really regretful, but medicine has developed a lot, don’t be worried, definitely be positive. | |||||||

| Symphatise | / | Opine | / | Suggest | / | Suggest | [–P,+SD] |

Here the response includes buyao-tai-danxin 不要太担心 (‘you shouldn’t be too worried’) and yiding-yao-le’guan 一定要乐观 (‘definitely be positive’). While these formulae may be less conventionalised, our respondent used them in a literary ‘parallel’ five-characters form, i.e. they are formalised.

As with our previous DCT featuring consoling the victim of a scam, Willing (Offer) tends to be realised here only in [–SD] relationships where our respondents were apparently willing to help:

| 您好好休息, 需要我做什么您尽管吩咐。 | |||

| Rest a lot, please let me know if there is anything I can do for you. | |||

| Suggest | / | Willing (Offer) | [+P,–SD] |

Requests (for information) mostly include ritualised inquiries about the other’s wellbeing. In (25) above the Request Laoshi, nin zuijin shenti hai hao ma? 老师, 您最近身体还好吗? (‘Teacher, are you [V form] feeling well, lately?’) is clearly a ritual query, since the raison ê’tre of consoling the other is that the other does not feel well. This sense of social meaning is also reflected in other Request realisations:

| 老师, 您最近身体怎么样了, 要注意休息啊。 | |||

| Teacher, how do you feel lately? Make sure you have rest! | |||

| Request (for information) | / | Suggest | [+P,+SD] |

The fact that this Request (for information) is followed by a Suggest shows that it has a strong social load.

Similar to the scamming situation, Symphatise here is infrequent and is only used in the [–P,+SD] relationship. In (27), our respondent used the expression tai-kexi-le 太可惜了 (‘very regretful’), which is not used in any other relationships, i.e. it seems to be ‘reserved’ for distant contacts with no power.

4.2.5 Consoling the other for falling ill (English)

Table 5 shows the different speech acts across various role relationships:

Speech acts in various role relationships when consoling the other for falling seriously ill (English).

| Sympathise | Opine | Request (for information) | Willing (Offer) | |

| [–P,–SD] | 25 (17 formal) | 14 | 17 | 3 |

| [–P,+SD] | 20 (20 formal) | 6 | − | − |

| [+P,–SD] | 23 (20 formal) | 8 | 6 | 3 |

| [+P,+SD] | 20 (20 formal) | 8 | − | − |

| Total | 88 | 36 | 23 | 6 |

As Table 5 shows, Sympathise is as frequent in our second English DCT as in the scam situation. Further, this speech act is also most frequently realised with the ritual expression ‘I’m/am sorry [for/to]’:

| I’m sorry to hear this, Jane. This is horrible. Is there anything in which I can help? | |||||

| Sympathise | / | Opine | / | Willing (Offer) | [–P,–SD] |

| I am so sorry. Getting so seriously infected is really bad. | |||

| Sympathise | / | Opine | [–P,+SD] |

| I am very sorry, Professor Smith. This is horrible. Can I help in any way? | |||||

| Sympathise | / | Opine | / | Willing (Offer) | [+P,–SD] |

| I am very sorry, doctor. | |

| Sympathise | [+P,+SD] |

The Sympathise realisations above are clearly ritualised. As (30)–(32) show, Sympathise often co-occurs with Opines. Also, there are various Willing (Offer)-s, frequented in [–SD] situations as shown by (30) and (32).

In [–SD] relationships, another frequent speech act is Request (for information). In some [–P,–SD] utterances, the recipient is ‘bombarded’ with such Requests:

| Oh no, I’m so sorry. What happened? Can I help at all? | |||||

| Sympathise | / | Request (for information) | / | Request (for information) | [–P,–SD] |

Unlike in the scamming situation, Request (for information) is here preferred over Willing (Offer) because our respondents were not medical experts, i.e. there was very little they could actually offer to the recipient.

4.2.6 Contrastive analysis and discussion of the findings

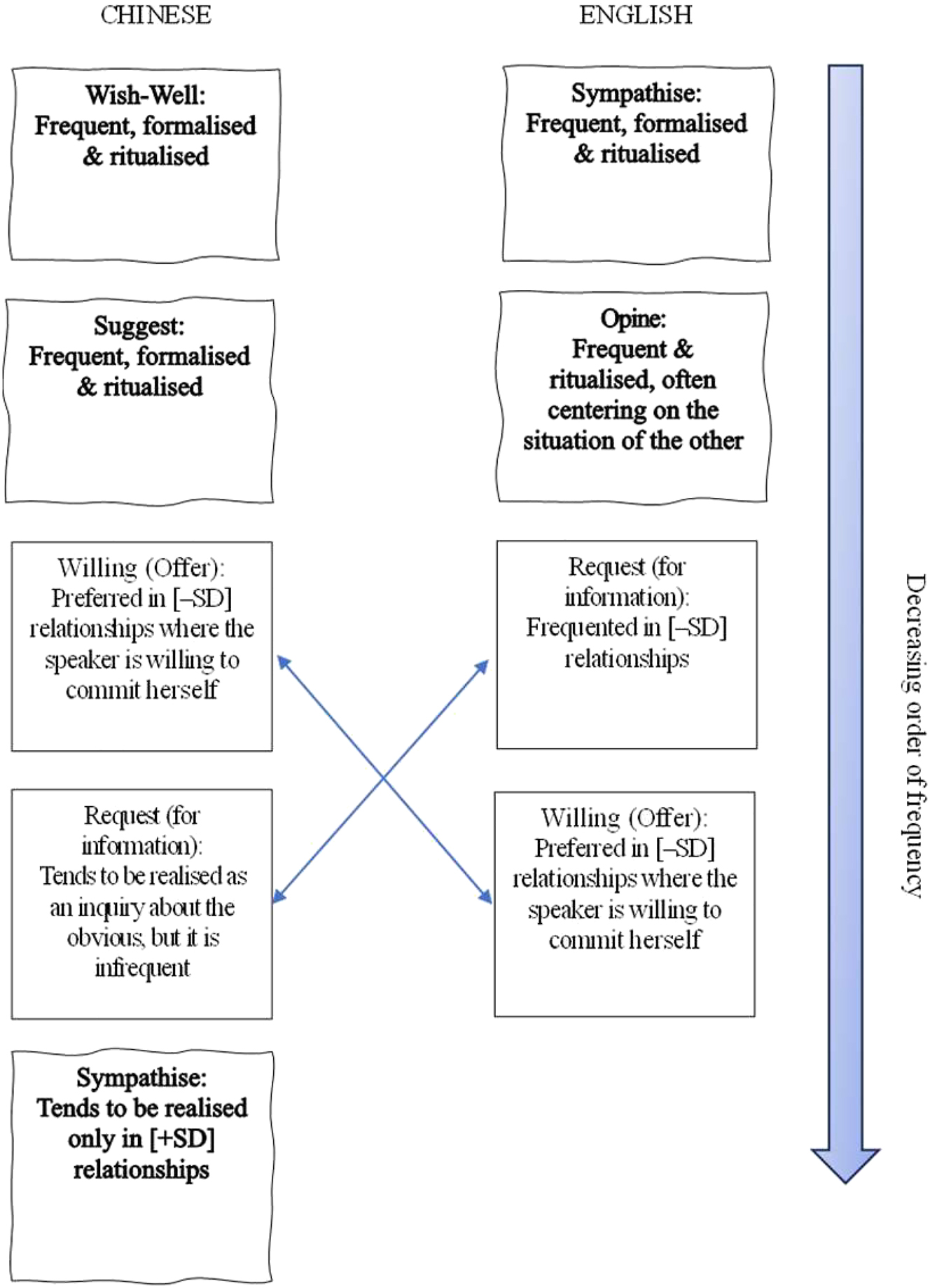

Figure 3 summarises the similarities and differences between our Chinese and English DCTs:

Contrastive analysis of speech acts frequented in consoling the falling seriously ill in Chinese and English.

As Figure 3 shows, our Chinese and English DCTs show significant similarities when it comes to Willing (Offer) and Request (for information). However, our Chinese and English datasets also show noteworthy differences:

Unlike the English speakers, our Chinese respondents preferred Wish-Well and Suggest. The lack of Wish-Well in our English data is easy to explain: in English, Wish-Well tends to be realised in closing phases (see Edmondson et al. 2023), and our DCT scenario presented a situation where one’s interactant describes her difficult situation before the closing phase. However, as our Chinese DCT data shows, Wish-Well is a conventionalised part of the ritual of expressing sympathy in the event of illness. When it comes to Suggest, we interpreted the preference for this speech act by reflecting on the outcome of our scamming incident DCTs: it seems that this speech act is generally important in Chinese ritual sympathising.

Our English-speaking respondents preferred Sympathise and Opine. Similar to Suggest in our Chinese data, Sympathise in English seems to be an integral part of ritual sympathising, used in all role relationships unlike Sympathise in Chinese. Opines in our English DCT included the expression of negative views about the illness through which the effect of sympathy was boosted.

A noteworthy similarity between the scamming and illness DCTs concerns realisation patterns of Sympathise: in both Chinese datasets Sympathise is infrequent and non-ritualised, whereas in both English datasets it is frequent and ritualised.

4.2.7 Condoling (Chinese)

Table 6 shows the different speech acts across various role relationships:

Speech acts in various role relationships in the ritual act of condolence (Chinese).

| Suggest | Opine | Willing (Offer) | Sympathise | |

| [–P,–SD] | 27 (18 formal) | 16 (9 formal) | 4 | 3 |

| [–P,+SD] | 19 (19 formal) | 8 (5 formal) | − | 6 |

| [+P,–SD] | 24 (23 formal) | 3 (3 formal) | 6 | − |

| [+P,+SD] | 23 (22 formal) | 3 (3 formal) | − | − |

| Total | 93 | 30 | 10 | 9 |

Similar to our other Chinese DCTs, Suggest is by far the most frequent speech act in the ritual of condolence. Suggest is most often realised with the formula jie’ai 节哀 (lit. ‘suppress your distress’) and its full form jie’ai-shunbian 节哀顺变 (lit. ‘suppress your distress and adapt to the change’), an archaic expression, which can be dated back to the Confucian Classic Book of Rites (ca. 1st century BC) where the following is mentioned:

喪禮哀戚之至也。節哀順變也。

The rites of funeral concern the ultimate of grief: they regulate grief and enable it to adapt to the change.

The consoling use of jie’ai-shunbian derives from this Classic: through the words jie’ai-shunbian the addressee is literally advised to follow the ritual of mourning and then adapt to the change in life caused by the loss. The following extracts illustrate uses of the jie’ai forms, along with other Suggest formulae such as baoyang-ziji 保养自己 (‘take care of yourself’):

| 节哀顺变, 好好保养自己。 | |||

| Restrain your grief and adapt to the change, take good care of yourself. | |||

| Suggest | / | Suggest | [–P,–SD] |

| 请节哀珍重。 | |

| Qing restrain your grief and take good care of yourself. | |

| Suggest | [–P,+SD] |

| 老师请您节哀, 保重自己。 | |||

| Teacher, restrain your grief, take care of yourself. | |||

| Suggest | / | Suggest | [+P,–SD] |

| 节哀顺变, 请老师保重身体! | |||

| Please restrain your grief and adapt to the change, please, teacher, take good care of your health. | |||

| Suggest | / | Suggest | [+P,+SD] |

Another formulaic Suggest expression, which some of our respondents used in [–P,–SD] and [–P,+SD] relationships, is shunji-ziran 顺其自然. While its English translation – ‘let nature take its course’ – may sound ‘cold and tactless’ for foreigners, for speakers of Chinese this expression, which originates in a historical Taoist work,[2] refers to the philosophical principle of accepting changes brought about by nature. Along with such formulae, various respondents realised Suggest in non-formulaic ways:

| 你以后要照顾好自己, 开开心心的, 过成她期望的样子, 她肯定会知道的。 | |||||

| From now on you should take good care of yourself and live happily, live the life she [i.e. the passed away parent] hoped, the deceased surely knows that. | |||||

| Suggest | / | Suggest | / | Opine | [–P,–SD] |

While most Suggest realisations in our Chinese dataset are formulaic, we also observed several non-formalised uses, particularly in the [–SD] setting. Such uses always co-occur with formulaic Suggests:

| 老师请节哀!如果有什么需要帮忙的老师可以找我。老师您先忙家里的事儿。 | |||||

| Teacher, please restrain your grief! If you need any help, please feel free to contact me. Teacher, you [V pronoun] may wish to focus on your matters at home. | |||||

| Suggest | / | Willing (Offer) | / | Suggest | [+P,–SD] |

Opine is another commonly used speech act, although it is much less frequent than Suggest. In all role relationships, participants provided various formulaic Opine realisations:

| 请节哀!死者安息, 生者坚强, 日子还要过, 他在天堂也会希望你活得好的。 | |||||||||

| Please restrain your grief! The dead should rest in peace, the living should be strong, you still have your life to live, and I am sure he wishes in heaven that you live a happy life. | |||||||||

| Suggest | / | Opine | / | Opine | / | Suggest | / | Opine | [–P,+SD] |

| 请节哀珍重, 世事无常, 总是有人会再也见不到了。 | |||||

| Qing restrain your grief and take good care of yourself, The matters of life are unpredictable, there is always one who we will never see again. | |||||

| Suggest | / | Opine | / | Opine | [+P,–SD] |

| 节哀顺变啊, 所有的同学说他总听你说他是很好的人, 天妒英才, 别太难过了。 | |||||

| Restrain your grief and adapt to the change. All students say that they always heard you saying that deceased was a very good person. Heaven is jealous of talents, so don’t be overwhelmed by grief. | |||||

| Suggest | / | Opine | / | Suggest | [+P,+SD] |

In extract (41) our respondent used the four-character condolence expressions sizhe-anxi 死者安息 (‘the dead should rest in peace’) and shengzhe-jianqiang 生者坚强 (‘the living should be strong’), in (42) the respondent provided the condolence formula shishi-wuchang 世事无常 (‘the matters of life are unpredictable’), and in (43) the condolence expression tiandu-yingcai 天妒英才 (‘heaven is jealous of talents’) is used. The frequency of such formulae shows that they are ritualised. We could also find a small number of non-formulaic Opines:

| 人都会死的, 死不一定是坏事, 别太难过, 要向前看。 | |||||||

| Everyone will die, and death is not necessarily a bad thing. Don’t be too sad, you should look ahead. | |||||||

| Opine | / | Opine | / | Suggest | / | Suggest | [–P,–SD] |

Similar to our other Chinese datasets, Willing (Offer) only occurs in [–SD] relationships. Extract (40) already illustrated a Willing (Offer) realisation in a [+P,–SD] case, and the following extract features a [–P,–SD] realisation:

| 亲爱的 [抱抱], 我能为你做什么? | |||

| My dear [hugging her], what can I do for you? | |||

| Symphatise | / | Willing (Offer) | [–P,–SD] |

Sympathise is infrequent in our data, only occurring in [–P] relationships in non-formulaic ways. (45) above already illustrated such a use.

4.2.8 Condoling (English)

Table 7 shows the different speech acts across various role relationships:

Speech acts in various role relationships in the ritual act of condolence (English).

| Sympathise | Willing (Offer) | Opine | Suggest | |

| [–P,–SD] | 26 (17 formal) | 19 | 13 | 3 |

| [–P,+SD] | 22 (22 formal) | 6 | 10 | 4 |

| [+P,–SD] | 24 (21 formal) | 19 | 7 | - |

| [+P,+SD] | 23 (23 formal) | 2 | 5 | - |

| Total | 95 | 46 | 35 | 7 |

Similar to our other English DCT datasets, all our respondents frequented Sympathise in the ritual act of condoling. As elsewhere, they preferred the expression ‘I’m/am sorry [for/to]’:

| I’m so sorry for you loss. Please know that I’m here for you if you need someone to talk to. | |||

| Sympathise | / | Willing (Offer) | [–P,–SD] |

| I am extremely sorry to hear this. This must be extremely difficult for you. | |||

| Sympathise | / | Opine | [–P,+SD] |

| I am so sorry for your loss, Professor X. Is there anything in which I can help? | |||

| Sympathise | / | Willing (Offer) | [+P,–SD] |

| I am extremely sorry for your loss, Doctor. Such devastating news. | |||

| Sympathise | / | Opine | [+P,+SD] |

Along with ‘sorry [for/to]’ expressions, various of our participants used formulae involving the word ‘condolence’:

| Doctor Smith, please accept my heartfelt condolences. | |

| Sympathise | [+P,–SD] |

The frequency and formulaic nature of such Sympathise realisations show that they are ritualised. In some cases, they co-occurred with non-formulaic Sympathise realisations:

| I’m sorry for your loss. I know how difficult it is for you. Let’s pray that she will be at peace where she is now. | |||||

| Sympathise | / | Sympathise | / | Suggest | [–P,–SD] |

Willing (Offer) occurred frequently, as (46) and (48) illustrate. Yet, many such realisations occurred in [–SD] settings, indicating that Willing (Offer) has at least as strong referential as symbolic meaning.

Opine either involved negative opinions about the difficulty of the situation, or positive opinions about the whereabouts and potential wellbeing of the deceased person:

| Deepest condolences to you and your family. I am sure your relative is now in a better place. | |||

| Sympathise | / | Opine | [–P,–SD] |

Along with such Opines, Suggest also occurs in the form of religious utterances, as in (51) above.

4.2.9 Contrastive analysis and discussion of the findings

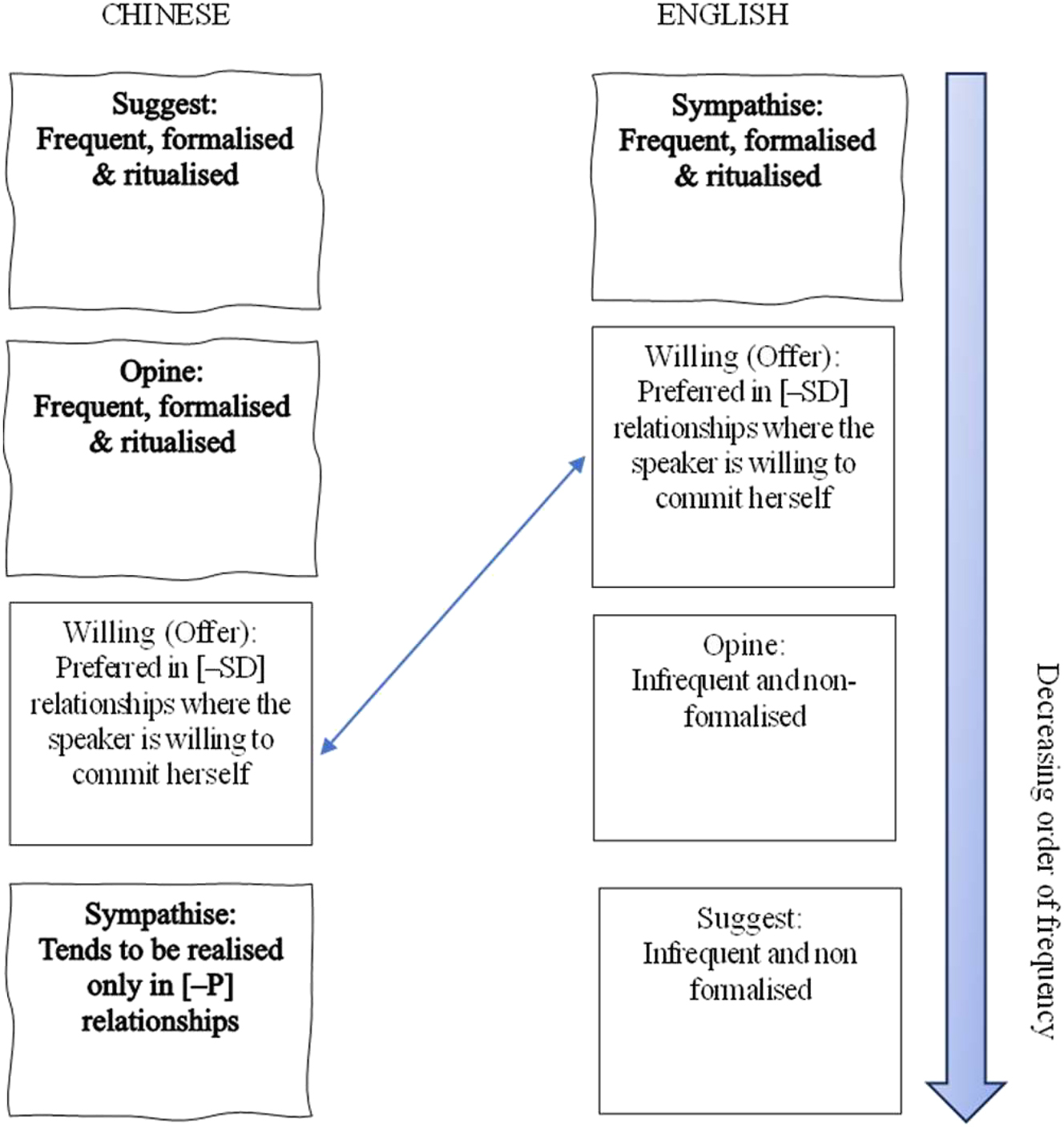

Figure 4 summarises the similarities and differences between our Chinese and English DCT datasets:

Contrastive analysis of speech acts frequented in realising condolence in Chinese and English.

Figure 4 shows that what we found in the scamming and illness DCTs also applies to condolence: while in English expressing condolence is realised by default with the speech act Sympathise in all role relationships, in Chinese the default speech acts are Suggest and Opine, while Sympathise is rare and occurs only in [–P] relationships.

4.3 Phase three: interpreting our initial interviews in light of the DCTs

Let us revisit the outcomes of our interviews conducted with Chinese and American expatriates through the outcomes of our DCT study. Our US expatriates had voiced the following opinions:

The Chinese do not express sympathy in a ‘Western’ sense and do not have ‘real’ condolence expressions.

The Chinese prefer giving general philosophical suggestions instead of consoling in the context of being scammed. They tend to give redundant ‘advice’ for the sick, and in the context of condolence they provide obvious phrases such as ‘take care’ when the actual problem is more serious.

Our American respondents also often attributed expressions ‘full of Asian wisdom’ to the Chinese.

Our Chinese expatriates made the following observations:

The Americans are ‘robotic and cold’ in the scamming and illness scenarios, and ‘shallow and superficial’ in the context of condoling the other.

The Americans neither provide advice for a person who is in trouble with a scam, nor do they express a positive attitude towards a sick person.

Let us relate these evaluations to the analysis of our DCT data.

The first American perception can be explained by the infrequency of Sympathise in Chinese sympathising rituals.

The second perception relates to the frequency of Opine in Chinese sympathising rituals. Such Opines, unlike comparable Opines in English, often do not evaluate the situation itself. The high frequency of Suggest in Chinese is responsible for the perception that the Chinese give redundant ‘advice’ for the sick instead of commiserating.

The third perception that in all situations the Chinese frequent expressions ‘full of redundant Asian wisdom’ relates to the variation of Chinese symphathising formulae across role relationships. This variation is in stark contrast to the ubiquitous English ‘sorry’ expressions used in every role relationship.

The first Chinese perception that the Americans are ‘robotic and cold’ can be explained by the frequency of Sympathise in English: notwithstanding the gravity of a situation triggering sympathy, speakers of English prefer Sympathise. This finding confirms House’s (2006) observation that speakers of English, as opposed to German speakers, rely on a minimal set of routine formulae in many situations.

The second observation of our Chinese participants – i.e. the lack of advice and/or positive attitude in times of need – can be explained by the lack of Suggest and Opine in English realisations of sympathising.

5 Conclusions

In this paper, we have presented a replicable framework, which enabled us to capture similarities and differences of expressing sympathy in Chinese and English in three different situations where somebody experienced distress of increasing gravity. A key feature of our framework is that it approaches sympathising as an interaction ritual, and in so doing it does not associate sympathising with a particular ceremony such as condoling. Further, the framework proposed combines the interaction ritual view with a finite typology of speech acts, with the aid of which it becomes possible to examine realisation patterns of sympathising in a rigorous and replicable way and tease out which speech acts are ritualised in sympathising. To illustrate the use of this framework, we have conducted a tripartite contrastive analysis.

The outcomes of our analysis allow the following deeper interpretation regarding the ritual act of sympathising in Chinese and English:

Speakers of English focus on situations in the here-and-now. Chinese speakers go beyond this here-and-now situation, lifting it up to a more general philosophical level that transports someone out of the situation.

The Americans use passe partout formulae, and the Chinese apply more diverse, situationally appropriate, and as such ad hoc formulae.

With these two general findings, we do not intend to reinforce the problematic ‘East–West’ divide. Rather, we aim to draw attention to the power of contrastively examining ritual behaviour in typologically different linguacultures.

In future, it would be fruitful to pursue the line of research we proposed, by contrasting similarities and differences between sympathising in various East Asian linguacultures, and ‘Western’ linguacultures other than English. While in this study we contrasted English and Chinese realisations of sympathising, it would be insightful to compare e.g. Chinese and Japanese expressions of sympathising, by considering whether Japanese nationals living in China experience the same issues as the Westerners reported in our study.

Funding source: Nemzeti Kutatási Fejlesztési és Innovációs Hivatal

Award Identifier / Grant number: Tématerületi Kiválósági Pályázat (Research)

References

Alabi, Victor. 2022. Discursive constructions of selected Yorùbá speech acts. PhD dissertation, Indiana University.Suche in Google Scholar

Blum-Kulka, Shoshana, Juliane House & Gabriele Kasper (eds.). 1989. Cross-cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.Suche in Google Scholar

Clark, Candance. 1997. Misery and company: Sympathy in everyday life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226107585.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Edmondson, Willis & Juliane House. 1981. Let’s talk and talk about it: A pedagogic interactional grammar of English. München: Urban & Schwarzenberg.Suche in Google Scholar

Edmondson, Willis, Juliane House & Dániel Z. Kádár. 2023. Expressions, speech acts and discourse: A pedagogic interactional grammar of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108954662Suche in Google Scholar

Eisenchlas, Susana. 2012. Gendered discursive practices on-line. Journal of Pragmatics 44(4). 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.02.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Elwood, Kate. 2004. “I’m so sorry”: A cross-cultural analysis of expressions of condolence. Waseda Papers in Economics and Culture 24. 101–126.Suche in Google Scholar

García, Carmen. 2010. ‘Cuente conmigo’: The expression of sympathy by Peruvian Spanish speakers. Journal of Pragmatics 42(2). 408–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.05.024.Suche in Google Scholar

Goffman, Erving. 1967. Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face behavior. New York: Pantheon.Suche in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1979. Communication and the evolution of society. T. McCarthy (trans.). New York: Beacon.Suche in Google Scholar

House, Juliane. 2006. Communicative styles in English and German. European Journal of English Studies 10(3). 249–267.10.1080/13825570600967721Suche in Google Scholar

House, Juliane & Dániel Z. Kádár. 2021a. Cross-cultural pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108954587Suche in Google Scholar

House, Juliane & Dániel Z. Kádár. 2021b. Altered speech act indication: A contrastive pragmatic study of English and Chinese thank and greet expressions. Lingua 264. 103162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2021.103162.Suche in Google Scholar

House, Juliane & Dániel Z. Kádár. 2023. Speech acts and interaction in second language pragmatics: A position paper. Language Teaching. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444822000477.Suche in Google Scholar

Jing-Schmidt, Zhuo & Ting Jing. 2011. Embodied semantics and pragmatics: Empathy, sympathy and two passive constructions in Chinese media discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 43(11). 2826–2844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2011.04.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Jing, Xiaoping & Hui Du. 2020. 突发公共卫生背景下老年人在微博新闻中的身份建构研究 (A study of identity construction of the elderly in Weibo News on public health emergency). Sinología Hispánica 10(1). 27–50.10.18002/sin.v10i1.6314Suche in Google Scholar

Kádár, Dániel Z. 2017. Politeness, impoliteness and ritual: Maintaining the moral order in interpersonal interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781107280465Suche in Google Scholar

Kissine, Mikhail. 2013. From utterances to speech acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511842191Suche in Google Scholar

Kitayama, Shinobu & Hazel Markus. 2000. The pursuit of happiness and the realization of sympathy: Cultural patterns of self, social relations, and well-being. In Eunkook Suh & Shigehiro Oishi (eds.), Subjective well-being across cultures, 113–161. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/2242.003.0010Suche in Google Scholar

Kongo, A. & K. Gyasi. 2015. Expressing grief through messages of condolence: A genre analysis. African Journal of Applied Research 2(2). 61–71.Suche in Google Scholar

Koopmann-Holm, Birgit & Jeanne Tsai. 2014. Focusing on the negative: Cultural differences in expressions of sympathy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 107(6). 1092–1115. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037684.Suche in Google Scholar

Leech, Geoffrey. 1983. Principles of pragmatics. London: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Levinson, Stephen. 2017. Speech acts. In Yan Huang (ed.), Oxford handbook of pragmatics, 199–216. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199697960.013.22Suche in Google Scholar

Meiners, Jocelly. 2017. Cross-cultural and interlanguage perspectives on the emotional and pragmatic expression of sympathy in Spanish and English. In Vahid Parvaresh & Alessandro Capone (eds.), The pragmeme of accommodation: The case of interaction around the event of death. London: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-55759-5_17Suche in Google Scholar

Nakajima, Keiko. 2002. The key to intercultural communication: A comparative study of speech act realization of sympathy/empathy. PhD Thesis, U. of Mississippi.Suche in Google Scholar

Nguyen Thi Lap. 2016. Major similarities and differences between English and Vietnamese sympathy expressions. Số 8(86). 67–76.Suche in Google Scholar

Peneva, Deyana. 2020. The communicative acts of sympathy and condolence in English and Bulgarian – pragmalinguistic aspects. Studies in Linguistics, Culture, and FLT 8(3). 23–35. https://doi.org/10.46687/silc.2020.v08i03.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Pishghadam, Reza & Mostafa Morady Moghaddam. 2012. Investigating condolence responses in English and Persian. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning 2(1). 39–47. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2012.102.Suche in Google Scholar

Sheikhan, Sayyed Amir. 2017. Rapport management toward expressing sympathy in Persian. Linguistik Online 83. 4–17. https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.83.3787.Suche in Google Scholar

Vanderveken, Daniel. 1990. Meaning and speech acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Zepeng, Yansheng Mao & Fangfang Long. 2023. Where there is suffering, there is sympathy: The speech act Sympathize in learning Chinese as a foreign language. International Journal of Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12490.Suche in Google Scholar

Wuthnow, Robert. 2012. Acts of compassion: Caring for others and helping ourselves. Princeton: Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400820573Suche in Google Scholar

Zhao, Dan 赵丹 & Zhang, Yan 张 焱. 2018. 礼貌原则在口语教学中的身份建构功能阐释 (An elaboration of the identity-establishing function of Politeness Principle in oral English teaching). Modern Linguistics 6(2). 225–232. https://doi.org/10.12677/ML.2018.62028.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhou, Shujiang 周树江. 2016. 论同情话语的和谐关系建构机制——以《红楼梦》同情话语为例 (‘On rapport-constructing mechanism of sympathy discourses: Evidence from Dream of the Red Chamber’). Journal of Beijing International Studies University 38(6). 15–24.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Special Issue 1 : Applied Linguistics, Ethics and Aesthetics of Encountering the Other; Guest Editors: Maggie Kubanyiova and Angela Creese

- Introduction

- Introduction: applied linguistics, ethics and aesthetics of encountering the Other

- Research Articles

- “When we use that kind of language… someone is going to jail”: relationality and aesthetic interpretation in initial research encounters

- The humanism of the other in sociolinguistic ethnography

- Towards a sociolinguistics of in difference: stancetaking on others

- Becoming response-able with a protest placard: white under(-)standing in encounters with the Black German Other

- (Im)possibility of ethical encounters in places of separation: aesthetics as a quiet applied linguistics praxis

- Unsettled hearing, responsible listening: encounters with voice after forced migration

- Special Issue 2: AI for intercultural communication; Guest Editors: David Wei Dai and Zhu Hua

- Introduction

- When AI meets intercultural communication: new frontiers, new agendas

- Research Articles

- Culture machines

- Generative AI for professional communication training in intercultural contexts: where are we now and where are we heading?

- Towards interculturally adaptive conversational AI

- Communicating the cultural other: trust and bias in generative AI and large language models

- Artificial intelligence and depth ontology: implications for intercultural ethics

- Exploring AI for intercultural communication: open conversation

- Review Article

- Ideologies of teachers and students towards meso-level English-medium instruction policy and translanguaging in the STEM classroom at a Malaysian university

- Regular articles

- Analysing sympathy from a contrastive pragmatic angle: a Chinese–English case study

- L2 repair fluency through the lenses of L1 repair fluency, cognitive fluency, and language anxiety

- “If you don’t know English, it is like there is something wrong with you.” Students’ views of language(s) in a plurilingual setting

- Investments, identities, and Chinese learning experience of an Irish adult: the role of context, capital, and agency

- Mobility-in-place: how to keep privilege by being mobile at work

- Shanghai hukou, English and politics of mobility in China’s globalising economy

- Sketching the ecology of humor in English language classes: disclosing the determinant factors

- Decolonizing Cameroon’s language policies: a critical assessment

- To copy verbatim, paraphrase or summarize – listeners’ methods of discourse representation while recalling academic lectures

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Special Issue 1 : Applied Linguistics, Ethics and Aesthetics of Encountering the Other; Guest Editors: Maggie Kubanyiova and Angela Creese

- Introduction

- Introduction: applied linguistics, ethics and aesthetics of encountering the Other

- Research Articles

- “When we use that kind of language… someone is going to jail”: relationality and aesthetic interpretation in initial research encounters

- The humanism of the other in sociolinguistic ethnography

- Towards a sociolinguistics of in difference: stancetaking on others

- Becoming response-able with a protest placard: white under(-)standing in encounters with the Black German Other

- (Im)possibility of ethical encounters in places of separation: aesthetics as a quiet applied linguistics praxis

- Unsettled hearing, responsible listening: encounters with voice after forced migration

- Special Issue 2: AI for intercultural communication; Guest Editors: David Wei Dai and Zhu Hua

- Introduction

- When AI meets intercultural communication: new frontiers, new agendas

- Research Articles

- Culture machines

- Generative AI for professional communication training in intercultural contexts: where are we now and where are we heading?

- Towards interculturally adaptive conversational AI

- Communicating the cultural other: trust and bias in generative AI and large language models

- Artificial intelligence and depth ontology: implications for intercultural ethics

- Exploring AI for intercultural communication: open conversation

- Review Article

- Ideologies of teachers and students towards meso-level English-medium instruction policy and translanguaging in the STEM classroom at a Malaysian university

- Regular articles

- Analysing sympathy from a contrastive pragmatic angle: a Chinese–English case study

- L2 repair fluency through the lenses of L1 repair fluency, cognitive fluency, and language anxiety

- “If you don’t know English, it is like there is something wrong with you.” Students’ views of language(s) in a plurilingual setting

- Investments, identities, and Chinese learning experience of an Irish adult: the role of context, capital, and agency

- Mobility-in-place: how to keep privilege by being mobile at work

- Shanghai hukou, English and politics of mobility in China’s globalising economy

- Sketching the ecology of humor in English language classes: disclosing the determinant factors

- Decolonizing Cameroon’s language policies: a critical assessment

- To copy verbatim, paraphrase or summarize – listeners’ methods of discourse representation while recalling academic lectures