Abstract

This paper emerged from an encounter with the Black Lives Matter placard I understand that I will never understand but I stand with you in Leipzig, Germany, and it centers white understanding as a constitutive practice of whiteness. This is mainly a theoretical contribution (learning towards the philosophical), although it includes some interview data and observations from protest participation. I contribute to raciolinguistics by reading the concept of the white listening subject through Barad’s new materialist notion of apparatuses, asking what exactly constitutes white understanding. This allows me to bring out the potentials and pitfalls (i.e. the counter/productivity) of white understanding as a reflective practice, which I put into conversation with my embodied practice of under-standing (i.e. standing under) the placard at a BLM protest in Berlin. I show how the white body is measured by a Black norm in the protest space, producing a productive discomfort filled with opportunities for becoming response-able towards the Black Other, but also towards whiteness. Considering the ethico-esthetic framing of this collection, I pursue an aesthethics of wor(l)ding that inter-rupts, dis/entangles, and walks around with and in words. It gestures towards what we usually leave out when pursuing one analytical avenue over another.

1 Introduction

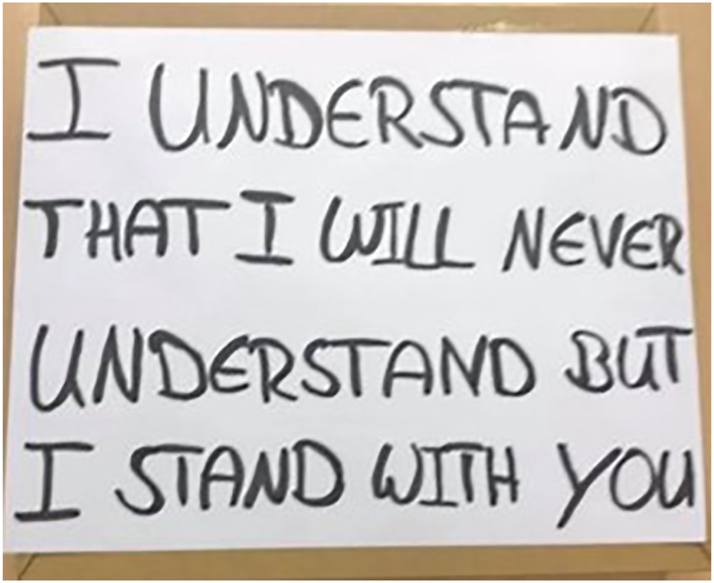

This paper emerged from an encounter with the Black Lives Matter protest placard I understand that I will never understand but I stand with you. I encountered it for the first time leaning against a shop window in Leipzig, Germany in 2020, a day after the BLM protest induced by the global outrage around the murder of George Floyd by a white police officer in the US. The placard is the pivot of this theoretical paper. I don’t provide a comprehensive interpretation of it. Rather, I treat the placard as a relational phenomenon that becomes differently in different encounters and intra-actions (Barad 2007). I therefore set out to generate “a force field of possible meanings and readings” (Bock and Stroud 2019: 24) and uptakes (‘uptakes’ also in the sense of actually taking up, i.e. picking up and carrying, the placard), centering one of the constitutive practices of whiteness that became particularly salient in my encounter with the placard: white understanding.

As this collection follows an ethico-esthetic framework it seems appropriate to share my own ethical qualms that accompanied me throughout the research and writing process. The placard is a co-constituent of BLM, a Black-centered and Black-centering movement. The way I attend to and write the placard centers whiteness. This is a familiar move where white people like myself in privileged positions use spaces created by and for Black people to center their own concerns, and even to advance their careers, taking time and attention away from the interests of the marginalized group (di Angelo 2018; Gramling 2022). Yet, what kept me writing this paper is a feeling that, in order to be good allies, white people need a philosophical and an embodied sense of their own whiteness, i.e. of the practices that co-constitute it, and of the consequences these practices might have in specific situations. In line with Toohey (2019: 943) I hope that this research output can add to “potentially useful assemblages for ongoing learning.”

Thematically, conceptually and philosophically this paper contributes to the interdisciplinary field of applied linguistics. Scholars are here increasingly calling for the inclusion, even the centering, of race as an important analytics (Makoni et al. 2023) – in the German context not often directly via the term ‘race’ (see however Oldani and Truan 2022) but for example via notions of ‘ethnische Zuschreibungen’ [ethnic ascriptions] (Wiese 2017). On the one hand, this is driven by concerns about the marginalization of, and systemic discrimination against, racialized student and teacher populations in education (Flores et al. 2021; Flores and Rosa 2015; Wiese et al. 2017). On the other hand, questions around whiteness are also increasingly discussed by bringing practices of the hegemonic white listening or perceiving subject, as conceptualized by Inoue (2003), Rosa and Flores (2017) and others, into focus (Cushing and Snell 2022; Flores and Rosa 2022; Gramling 2022; Kubota 2020). This paper contributes to this second effort of what I would summarize as de/centering whiteness in applied linguistics, i.e. decentering whiteness by centering some of the practices and mechanisms through which it asserts and maintains its power, such as white understanding.

In the first part of this paper, I use my encounter with the placard, together with the raciolinguistic concept of the white listening subject, to shed light on the continuous Othering[1] of Black people in Germany, and on how whiteness retains its invisibility for the majority population. The next section both critiques and contributes to studies in applied linguistics that draw on new materialism, specifically on the work of Barad (Canagarajah 2018; Pennycook 2018; Toohey 2019), to develop more material and embodied analytical orientations. These, in my view, are essential for attending to racialization as an embodied process, and to the ontological shifts, including the physical, material force, that this process exerts. Barad’s work, for example their concept of apparatuses, has drastic implications that can help bring out the ontological dimensions of the concept of the white listening subject not as ‘perceiving a world out there’ but as ontologically co-constituting the world. This then allows for making a stronger point about white responsibility in terms of learning to sense and mediate co-constitutive practices of whiteness there where they have negative consequences for the racialized Other. This responsibility extends into our writing practices as scholars, because, following Barad, we can no longer write about the world, we can only write the world. Contributing to the ethico-esthetic framing of this collection, I discuss these implications for our writing practices and suggest an aesthethics of wor(l)ding (Barad 2007, 2010, 2019; Barad and Gandorfer 2021). Gandorfer uses the modified term aesthethics to draw attention to the ethics involved in our perception and in our choice of analytical entry points (Barad and Gandorfer 2021: 50) and I use the (l) in wor(l)ding to unsettle conceptual and alleged ontological divisions between word and world, between language and materiality (see Cavanaugh and Shankar 2017 for discussion of language (and) materiality). This aesthethics of wor(l)ding helps to bring together the established focus on meaning making in applied linguistics with a sensitivity for the materiality and texture of written words, opening up possibilities to walk around in words and to thereby find new forms of expression and analysis that de/center – make visible and rethink – white ways of knowing and being in the study of language.

In the second part of the paper, I then focus on white understanding and how it co-constitute apparatuses of whiteness in Germany (and elsewhere). Specifically, I bring into dialog the philosophers Lévinas and Yancy, and Black German interview participants who commented on the placard. Guided by the notion of apparatuses, white understanding emerges from these philosophical and discourse analytic explorations as counter/productive, holding both the potential for solidarity across often drastically different life worlds, and the potential to get in the way of ethical encounters that require us “to risk ourselves” and “to become undone in relation to others.” (Butler 2005: 136) I then put these explorations into conversation with my embodied, material-discursive practice of under-standing (i.e. standing under; carrying) the placard at a BLM protest in Berlin. I contend that white under-standing is a moment of potentially productive trouble (Haraway 2016), filled with opportunities for learning to become response-able – i.e. able to respond ethically instead of reductively – towards the Black Other, but also towards whiteness, in Germany. I end with some reflections regarding the relevance that these explorations of white under(-)standing have for applied linguistics.

2 The white listening subject and the Black Other in Germany

I didn’t partake in the BLM protest in Leipzig in 2020, but walking through the city with my husband Ali (from Iraq, mostly racialized as Arab) a day later, we found a different version of the placard (include here fig1_understand.jpg) leaning against an empty shop window. I didn’t think to take a picture of it, and we didn’t like the placard at first. I was convinced of the centrality of white understanding for the Black struggle, and one of Ali’s first reactions was to say: “Just another excuse for white people to do nothing.” But wait, white people? In Germany? It was clear to both of us that the “I” on the placard was white (see also Krause-Alzaidi forthcoming). The next realization for me was that a white body in Germany is a surprise. But why? Because whiteness here is normally im/perceptible: perceptible for Others in its effects on them, but imperceptible for whites themselves (like me). The surprise at the white German body resonates with what Inoue (2003: 157) writes about the modes of perception of the listening subject: “A particular mode of hearing and seeing is, then, an effect of a regime of social power, occurring at a particular historical conjuncture, that enables, regulates, and proliferates sensory as well as other domains of experiences.”

This regime of social power in Germany normally constitutes white bodies as the listening subject (Inoue 2003; Rosa and Flores 2017) doing the seeing and hearing while not being seen or heard racially (at least not by those with political power). White listening subjects’ mode of perception is structured by raciolinguistic ideologies (Alim 2016; Alim et al. 2016, 2020) and is exercised from the hegemonic position of (usually invisible) whiteness (Alim and Smitherman 2012). It builds on an implicit notion of one-nation-one-language-one-race, constituted by “the continued rearticulation of colonial distinctions between Europeanness and non-Europeanness – and, by extension, whiteness and non-whiteness. These distinctions anchor the joint institutional (re)production of categories of race and language, as well as perceptions and experiences thereof.” (Rosa and Flores 2017: 622)

While the German state refuses to gather statistical data along ethnic or racial lines[2] (Ahyoud et al. 2018; CERD 2015), white Germans nevertheless see and hear Black Germans as the Other. Black people in Germany encounter questions and remarks like ‘Wo kommst du her?’ [Where are you from?], ‘Wo kommst du wirklich her?’ [Where are you really from?], ‘Du sprichst aber gut Deutsch!’ [But you speak German well!] (to name but a few) regularly (Hasters 2019; Ogette 2017; Oguntoye et al. 1986). The latter remark shows clearly how an indexical inversion (Inoue 2003) based on raciolinguistic ideologies happens in such encounters: The racialization of the body is the basis for how language is heard by the white hegemonic listening subject (not the other way around, as indexicality usually has it (Nakassis 2018)). As a result, Black Germans are doubly Othered as they “are consistently misrecognized as Africans, even after extensive conversation has established a German birthplace, parents, and education.” Thereby, they are produced as “both an Other-from-Within (a member of that country) and an Other-from-Without (misrecognized as an African).” (Wright 2003: 297) Such Othering leaves marks of continuous dis/placement – of being placed (often having been born and living in Germany all their lives) and displaced (always reminded that they do not fully belong) at the same time. These processes also have violent, sometimes deadly, outcomes, reaching from discrimination in flat or job hunting (if ones name is recognized is non-white), worrying about one’s children being discriminated against in schools, to fearing for one’s psychological and physical safety in certain spaces (Die Bundesregierung 2023). All the while, white Germans remain unracialized – the invisible, yet powerful norm on the other side of the Othering coin. This is why I was surprised to realize that the carrier of the placard must have been white, because whiteness does usually not emerge as an identity in my encounters in Germany. This, in turn, shows how my own perception is embedded in, and steered and sheltered by, hegemonic whiteness.

In the following section I show how Barad’s notion of apparatuses, which emerges from their transdisciplinary work in feminist theory, quantum physics and philosophy, can add conceptual nuance and a stronger focus on white responsibility to the concept of the listening subject. This is because notions of the listening subject are mostly conceptualized epistemologically, focusing on knowledge about, and perception of, the world while leaving the ‘world out there’ intact to be ‘seen’ and/or ‘heard’. Apparatuses, however, operate on the ontological level. This means that rather than perceiving a pre-existing Black body in a certain way, the listening subject co-produces said body in co-constitutive measuring intra-actions. This entangles the white listening subject in ethical questions of world-making (rather than world-perception) and therefore helps explore the question of ethical (white) subjectivity central to this special issue.

3 Intra-acting apparatuses of whiteness

3.1 Barad in applied linguistics

While Barad is beginning to be cited in applied linguistics (Canagarajah 2018; Pennycook 2018; Toohey 2019), and the critique that new materialism brings towards exclusionary, binary thinking is appreciated in the field, rarely are the full implications of Barad’s theoretical physics background considered. As welcome as interdisciplinarity is proclaimed to be in the ‘epistemic assemblage’ of applied linguistics (Pennycook 2018a), the quantum physics experiments with and through which Barad develops much of their philosophy are not explored in any detail in reviews of their work. In developing a posthumanist applied linguistics, Pennycook usefully questions the nature-culture divide drawing on Barad quite extensively. But in his book-length treatment of posthumanism the physics is completely circumvented. The focus is on Barad’s discussion of performativity and genealogy and doesn’t venture into the less familiar terrain of apparatuses, measurements and cutting together-apart. But I contend that it is exactly these unfamiliar ideas that can help us imagine new analytical avenues and new practices in applied linguistics, because they counteract a tendency to summarize and conclude our findings, helping us instead to tell more open, spacious, attentive and responsible research stories.

Canagarajah (2018) draws on Barad’s and other’s new materialist work when analyzing the communicative practices of international STEM scholars and building a theoretical paper that conceptualizes a more material and embodied idea of language competence. He outlines the differences between a sociocultural approach to language practices and the emergent material orientation. While in sociocultural analyses entities interact in complicated ways, they are ultimately assumed to exist as separate and individual – not so in the radically relational mode of material orientations where ontological primacy is granted to relationality (not individuality). He emphasizes that, in contrast to sociocultural theory, which operates within the representational paradigm, new materialist work adopts a non-representational, performative approach. Toohey’s (2019) study underlines these insights. She turns back to old data she had analyzed years ago with sociocultural theory. She shares how stepping back from sociocultural theory, which somewhat fixated her on the school identities of learners, and instead looking at the old data again with the help of new materialist scholars, especially Barad, opened up new insights and analytical avenues. Exploring the implications of new materialist onto-epistemologies for applied linguistics, Toohey brings in Barad’s notion of apparatuses. Yet, she doesn’t discuss the concept in relation to the quantum physics context from and through which it was developed. She uses the term mostly as a synonym for data gathering and analytical tools, which are entangled with the phenomena we seek to understand.

However, for Barad, apparatuses are not restricted to laboratories or research scenarios. They are the practices – including language and knowledge-making practices – through which we are constituted, and through which we co-constitute entities of the world (Barad 2007). It seems to me that the problem with skipping the physics when adapting Baradian concepts is that their drastic ontological implications are lost. We can also observe this when Canagarajah writes that Barad “is not opposed to identifying “boundaries” (which she refers to as “cuts” elsewhere; see p. 217)” (Canagarajah 2018: 288). He here equates Barad’s concept of cuts with the notion of boundaries. However, apparatuses are material-discursive boundary-making practices that cut subject and object together-apart. This one move, which I explain more below and which contains separation and relation at once, forces us to completely rework our notions of ‘boundaries’. In applied linguistics this is especially pertinent regarding our often taken-for-granted boundaries between language and the material world, as well as between and within words.

3.2 Apparatuses and cutting together-apart

Rejecting the a priori separation between the natural and the social, the non-human and the human, and between word and world, Barad brings together social theorists like Butler and Foucault, but also philosophers like Lévinas, with ideas from quantum physics. By reading them through each other, Barad extends the idea of apparatuses beyond the realm of quantum physics. Apparatuses are dynamic sets of open-ended material-discursive boundary making practices that produce phenomena through measuring intra-actions. Intra-action expresses a relational ontology: While interaction presupposes an individualist ontology where separate entities (that are primordial) enter into relations, intra-action describes processes of momentary constitution of entities – bodies, concepts, materials, sets of practices, etc. – from within ontologically primordial relations. I argue that Whiteness in Germany is an intra-acting set of apparatuses that measures for racialized bodies by enacting agential cuts that momentarily produce boundaries that constitute the measuring subject (the white listening subject) and the measured object (racialized bodies) as distinct. I should emphasize that Barad insists that analytics like apparatus and measurement are not to be extended by analogy or metaphor. Instead they argue that there is no reason to believe that ‘the social’, or phenomena on a physically larger scale than the quantum level, works fundamentally differently from the quantum world. In fact, the notion of measurement is extremely apt in bringing out the violence of racialization historically grown through enslavement, colonialism and eugenics, all dependent in different ways on measuring Black bodies. So when I explain the workings of apparatuses I invite the reader not to metaphorize (‘the physics apparatus is like the applied linguistics researcher with her recording device’) but to actually think of the white listening subject and its practices as co-constituting material measuring agencies and processes that bring forth, and leave marks on, Black bodies.

In classical physics, electrons were usually described as very small particles (located and dot-like bits of matter). But in the two-slit experiment, where electrons are shot at a wall with two slits to subsequently hit a measuring screen behind that wall, results suggested that they went through both slits simultaneously. But particles can’t do that, only waves can. To understand this better, Niels Bohr and Albert Einstein produced a thought experiment creating a two-slit experiment with a which-slit detector to detect through which of the two slits a particle traveled before hitting the measuring screen. Because waves go through both slits simultaneously (but a particle only through one slit at a time) Einstein predicted that a which-slit-detector would catch the electron somehow behaving like a particle and a wave simultaneously. Bohr disagreed. He focused on the role of the measuring apparatus, and argued that if a which-slit detector were to be inserted, the apparatus would measure for particle-like behavior and therefore particle-like behavior would emerge. This prediction points to an entanglement of the measuring agencies (e.g. walls, slits, screens, which-slit detector, the researcher involved, …) with the very ontology of what is being measured (here: electrons). Bohr’s prediction later came to be empirically confirmed. If a small modification of the intra-acting agencies within the apparatus can produce a change in the ontology of electrons (Barad 2007: 265–269), then what’s on either side of the apparatus – (a) the measuring agencies and (b) the measured (and thereby produced) objects – are in/separable, connected and disconnected simultaneously, cut together-apart. “Cutting together-apart (one move) involves a very unusual knife or pair of scissors” that produces “an agential cut together with the entanglement of what’s on “either side” of the cut since these are produced in one move.” (Juelskjær and Schwennesen 2012: 19–20) Entanglement[3] here means that a change in the experimental set-up effects an instantaneous change in the ontology of the measured object. Apparatuses do not produce results that represent the world, intra-acting sets of apparatuses co-constitute the world’s becoming.

As mentioned earlier, apparatuses are sets of material-discursive boundary-making practices – including language and knowledge-making practices – that constitute us, and through which we co-constitute entities of the world. Therefore, also in the racializing apparatuses of whiteness, the white measuring agencies are cut together-apart with (in/separable from) the Black bodies they produce, and are therefore entangled with them in a relation of responsibility. Much that characterizes their relationship depends on the nature of the ontologically co-constitutive practices that make up the measuring intra-action, such as white understanding, on which I will focus later. For now, I turn to the implications that the above-explained insights have for ethics and for how we know and write the world from within and beyond applied linguistics (Barad 2007, 2010, 2019; Barad and Gandorfer 2021).

4 Ethical subjectivity and an aesthethics of wor(l)ding

If the apparatuses we are a part of bring forth entities and bodies that come to matter in the world, then we are responsible for the world we co-produce and for that which we help to exclude from mattering: “That which is excluded in the enactment of knowledge-discourse-power practices plays a constitutive role in the production of phenomena – exclusions matter both to bodies that come to matter and those excluded from mattering.” (Barad 2007: 57) Here Barad draws on Lévinas, for whom responsibility is “the essential, primary and fundamental mode of subjectivity.” (Lévinas 1985: 95) The self is cut together-apart with the Other in a relation of responsibility and therefore, ethics – the questioning of the self in encounters with the Other (Lévinas 1979) – must be first philosophy. We end up with a notion of ethico-onto-epistemology in which ethics, being and knowing co-constitute one another. This is then also how I grapple with subjectivity as an ethical construct. Subjectivity is co-constituted through particular agential cuts enacted by apparatuses that bring forth subject and object from situated relations. ‘I’ (standing for ‘subject’ here) don’t decide alone about the cuts that co-constitute my subjectivity and about whom or what I am cut together-apart with here and now, or there and then. The relations of responsibility that make my-self and the Other are shifting. Ethical subjectivity is, then, being attentive to cuts and apparatuses, and to what gets left out or is made invisible. It also entails acknowledging responsibility and becoming response-able in encounters with the Other who is cut together-apart with me, in/separable from me.

The way we have been trained to use language in and by Western thought, however, is neither good at expressing shifting rationalities and entanglements, nor at drawing attention to what gets left out. We tend to use words to pin things down rather than to open up possibilities. Prinsloo (2022: 92) explains Derrida’s notion of hauntology – which is also one of Barad’s central inspirations – as invoking “that which gets left out but ‘doesn’t quite go away’ when we delineate subjects and objects in material-discursive practices and by so doing exclude some of their features, thus including an essential unknowing which underlies and may undermine what we think we know.”

How can we open up language to gesture towards that which gets left out? How can we, as Lugones (2006: 84) suggests, move from “liberal conversation [which] thrives on transparency and because of that it is monologized” towards “complex communication [which] thrives on recognition of opacity and on reading opacity, not through assimilating the text of others to our own.” She goes on to write that complex communication “is enacted through a change in one’s own vocabulary, one’s sense of self, one’s way of living, in the extension of one’s collective memory, through developing forms of communication that signal disruption of the reduction attempted by the oppressor.” As part of the ethico-esthetic framing of this special issue, I attempt this change in vocabulary and sense of self by pursuing an aesthethics of wor(l)ding (with aesthethics drawing attention to the ethics involved in our perception and in our choice of analytical entry points (Barad and Gandorfer 2021: 50)), which combines the established focus on meaning making in applied linguistics with a focus on the materiality and texture of written words themselves. By producing a different textu(r)al experience of the words in this paper I encourage readers to “walk around in a word or even a letter” because it is a wor(l)d that “entails stories, different stories” (Barad and Gandorfer 2021: 32) with disruptive potential. Drawing on my interpretation of Barad’s and Haraway’s writing practices, I use the slash (/) as in im/perceptible or un/comfortable expresses the above introduced ““cutting together-apart” between terms on either side of the slash.” (Barad 2019: 546, footnote 9) The ‘im/perceptibility of whiteness’ includes the perceptibility of whiteness through its effects, i.e. through the measuring marks it leaves on Black bodies. But the slash also nudges us into thinking of what gets left out: For example that the power to leave those marks derives exactly from the imperceptibility of whiteness as measuring agency that trains the spotlight away from itself onto the measured object: the racialized Black body.

The hyphen (-) makes us attend to the already existing material-discursive possibilities within a wor(l)d. In re-membering, the hyphen materially brings members or elements back together that had been dismembered. And, in Haraway’s (2016) response-ability, it slows us down[4] inside the wor(l)d and reorients us from a ‘taking of responsibility’, where responsibility seems to exist out there for us to pick up (or not), towards working on becoming response-able (able to respond ethically) in encounters with the Other. With apparatuses and the aesthethics of wor(l)ding introduced, I will now get in touch with the placard again – helped by Lévinas, Yancy, and courageous Black women in Germany, including my interviewees.

5 The counter/productivity of white understanding

I kept thinking about the encounter with the placard. How would other people relate to it? I began tracing versions of the placard through the German web, and I found it involved in Youtube videos and Instagram posts, which allowed me to contact the posting individuals or organizations. This way I found Black and white Germans willing to be interviewed. This was the beginning of a small research project centered around BLM protest placard in Germany (for more details see Krause-Alzaidi forthcoming). Most interviews took place between December 2020 and March 2021, some online, some face-to-face, always guided by pictures of BLM protest placards. Here I include comments related to I understand that I will never understand but I stand with you by Sarah and Noëmi, two Black German women with very positive attitudes towards the placard that contrasted strongly with my own at the time. The interviews were conducted in German, and this holds the methodological possibility of translingual walks between the English placard and the German interview comments that can enfold new meanings and agencies into the placard.

Understanding – or the German ‘Verstehen’ – is often invoked as a productive force in encountering the Other respectfully. In Farbe bekennen, Katharina Oguntoye, May Ayim, Dagmar Schultz and Audre Lorde made visible societal issues of race, racism and being Black in Germany through bringing together the courageous narratives of Afro-German women. Helga Emde, the daughter of a white German woman and a Black American GI, describes in her contribution the long journey of finding herself in a ‘weißes Bezugssystem’ [a white system of reference]. (Emde 1986: 111) She writes:

Bei meinem Mann habe ich etwas gesucht, was ich nie finden konnte, nämlich Solidarität. Er konnte vieles nicht verstehen, einfach weil er weiß war. Er hat diese vielen subtilen Verletzungen und Anfeindungen nicht erfahren, die seine und leider auch meine Gesellschaft mir zugefügt haben. Immer wieder bekam ich von ihm zu hören, ich sei zu empfindlich. (1986: 109)

[In my husband I was looking for something that I could never find, namely solidarity. He could not understand many things, simply because he was white. He did not experience the many subtle hurts and hostilities that his society, and unfortunately my society, inflicted on me. Again and again I heard from him that I was too sensitive (author’s translation).]

Emde finds the reason for her white husband calling her ‘too sensitive’ in his lack of understanding. Understanding appears here as the only gateway to white solidarity, exactly because the embodied experience of racial discrimination is inaccessible to a white body. However, the placard I understand that I will never understand but I stand with you puts into question the usefulness of white understanding (verstehen) in encounters with the Black Other. Sarah’s reaction when being shown the placard in our interview contrasts with Emde’s account:

… also das find ich tatsächlich gut, weil das ist so ne, so ne, das ist ne weiße Position aber das sone Selbst – son Surrendering. Also das ist so eins, weil ich glaube wir müssten viele Debatten nicht führ‘n, und nicht so schmerzvoll führ‘n, wenn es nicht immer wieder die weiße dominante Position immer wieder der Schwarzen Position sagen würde: „Naja sei mal nicht so, bildest de dir nur ein“, oder ne. (Sarah, Black, she/her, late 30s)

[… so I think that’s actually good because that’s such a, such a, that’s a white position but that’s such a self-surrendering. So that’s one, because I think we wouldn’t have to have a lot of debates and we wouldn’t have to have them so painfully if it wasn’t for the white dominant position always telling the Black position: “Well, don’t be like that, you’re just imagining things”, or something (author’s translation).]

Sarah connects white assertions of Black sensitivity (similar to those of Emde’s husband) to white understanding and not to the lack thereof. White understanding emerges here as an enactment of white dominance that produces ‘painful debates’. So while white understanding can be a central gateway to white solidarity and support, this view forgets that, in apparatuses of whiteness, depending on the exact measuring practices that constitute white understanding, its gateway function can easily turn into a gatekeeping function, getting in the way of true connection. I gesture towards this fine line when writing of white understanding as counter/productive, and Yancy gives us a philosophical starting point to explore the counter/productivity of white understanding:

It is only through the medium of “white understanding,” though, that the black voice will be heard. This “white understanding,” however, need not function as an insuperable barrier, but as an opportunity for the development of a porous horizon, one that responds positively to the Other in his or her difference, learns from the Other, and changes based upon an encounter with the Other. (Yancy 2004: 14)

So what constitutes white understanding as this ‘insuperable barrier’? To approach this question, let’s take a translingual walk in the space constituted by the English placard and two German interview comments by Sarah and Noëmi.

5.1 Ver-stehen and ein-ordnen: an insuperable barrier

… ich finde das [Plakat] ist wahnsinnig wichtig, da steckt schon ganz viel drin weil ähm Menschen die der Meinung waren die Themen zu gut zu verstehen sind auch nicht immer hilfreich. (Noëmi, Black, she/her, 31, my emphasis)

[… I think it [the placard] is incredibly important, there’s a lot in it, because people who think they understand the topics too well are also not always helpful (author’s translation)]

What is it about the wor(l)d verstehen that can make it unhelpful? Let’s begin with an etymology of verstehen:

Vor einem Gegenstand stehen, einen Gegenstand „vor Augen haben”, die unmittelbare Präsenz des Gegenstandes ist zweifelsohne eine prototypische Voraussetzung dafür, daß ein Gegenstand wahrgenommen oder intellektuell begriffen werden kann. ‘Vor etwas stehen’ und die Zielbedeutung ‘wahrnehmen, begreifen’ lassen sich somit sinnvoll aufeinander beziehen (Harm 2003: 111).

[Standing in front of an object, having an object “in front of one’s eyes”, the immediate presence of the object is undoubtedly a prototypical precondition for perceiving or intellectually grasping an object. ‘Standing in front of something’ and the target meaning ‘to perceive, to comprehend’ can thus be meaningfully related to each other (author’s translation).]

The etymology of verstehen is oriented towards a ‘target meaning’ that includes both perceiving and grasping some-thing (or some-body). Verstehen appears here as a project of rational sense-making by the listening subject. The Other, who has some-body ver-stehen them (i.e. standing in front of them), is forgotten. The physical barrier emerging through standing in front of some-body is etymologically erased through a reduction to visual perception. Verstehen is dis/embodied, located it in the eyes but removed from the rest of the body. But what is ver-stehen’s Other story? What might it feel like to be ver-standen? To be stood-in-front-of, looked at, measured, made sense of? Sarah and Noëmi, reacting to the placard in separate interviews, give us another wor(l)d to walk in while approaching these questions:

… es wird immer wieder die weiße Position erzählt und die weiße Position ordnet eigentlich das Schwarz-sein irgendwie auch noch ein und das war‘s dann schon (Sarah, Black, she/her, late 30s, my emphasis).

[… the white position is narrated over and over again and the white position actually somehow also categorizes/classifies being Black (Blackness) and then that’s it already (author’s translation).]

Also ich hab‘ ja auch schon wahnsinnig viele Leute erlebt in meinem Leben, die mir erklären wollten ob und inwieweit, also weiße Menschen, die mir erklären wollten ob und inwieweit ich jetzt Schwarz oder nicht bin und wie ich Dinge einzuordnen habe, wie ich die zu empfinden habe als Schwarze Person, etc. (Noëmi, Black, she/her, 31, my emphasis)

[I’ve already experienced a lot of people in my life who wanted to explain to me whether and to what extent, i.e. white people, who wanted to explain to me whether and to what extent I’m Black or not and how I have to understand things, how I have to feel about them as a Black person, etc. (author’s translation)]

Both Sarah and Noëmi use the split phrasal verb ‘einordnen’, which includes the practices of ‘ordering’, ‘categorizing’ and ‘classifying’. But all these could imply the creation of new categories as well. Ein-ordnen is an even more hegemonic practice. The ‘ein-’ (from ‘hinein’ (into), but also reminiscent of the number one (eins) – and here I don’t mean etymological or grammatical reminiscence, but an aesthethic one, based on my perception of the letter combination ‘ein’ and an ethical concern with the kind of hegemonic power that can be expressed through this verb – in ein-ordnen paves the way only into one already existing Ordnung (order) of things. When the white position ordnet Blackness ein, then, in that encounter, the white person already knew everything that there was to know about Blackness.

When translating Noëmi’s comment, my rendering of einordnen as ‘understand’ struck me. I had anticipated a relationship between the two practices but not such a close connection. Walking from ver-stehen through ein-ordnen via understand back to ver-stehen we get in touch with some of the barriers potentially produced by white understanding. Ver-stehen and ein-ordnen are practices of the white listening subject that measure only for their kn-own attributes and experiences, thereby ver-stehen (standing in the way of) the possibility to sense and respond to difference. The Other is eins (one) with the white listening subject, eingeordnet into whiteness. In these (often well-meaning) measuring intra-actions that which cannot be kn-own(ed), the ‘apart’ in cutting together-apart, the Other side of the slash, is not sensed as productive but forgotten. So what needs to shift in this apparatus so that white understanding can become a porous horizon where the white person “learns from the Other, and changes based upon an encounter with the Other”? (Yancy 2004: 14)

5.2 Towards white understanding as a porous horizon

… the black, within the social space of whiteness, does not constitute a radical Otherness, but an always already preinterpreted thing. The black is held captive by the totalizing tendencies of whiteness. As such, the black falls short of the Lévinasian notion of the infinite Otherness of the other; rather, the black constitutes a familiar and mundane sameness. (Yancy 2004: 13)

Yancy makes only this one explicit reference to Lévinas in Fragments of a social ontology of whiteness, but these ‘totalizing tendencies’ are constitutive of his social ontology of whiteness. He argues that in this ontology there is no slippage between knowing and being, between epistemology and ontology. White knowledge is conflated with ‘what there is’ and therefore becomes ontology. I read Yancy’s notion of ontology here in the Lévinasian sense of ‘theory as comprehension’:

To theory as comprehension of beings the general title ontology is appropriate. Ontology, which reduces the other to the same, promotes freedom – the freedom that is the identification of the same, not allowing itself to be alienated by the other. Here theory enters upon a course that renounces metaphysical Desire, renounces the marvel of exteriority from which that Desire lives. (Lévinas 1979: 42)

Ethics, for Lévinas, is exactly the questioning of ‘the same’, the questioning of ontology, induced by the presence of the Other (Lévinas 1979). Ethical encounters with the Other are those that manage not to recognize the Other by assimilation (Spivak 1994), i.e. not to bring the Other into a totalizing relation of sameness with one-self in which everything about the Other is already com-prehended, completely seized. Ethical encounters are driven by ‘the marvel of exteriority’; what Lévinas calls the metaphysical Desire induced by the infinite Otherness of the Other. Ethical encounters reign in Lévinas’ idea of freedom as the ability to move in the world with ontological certainty, with categorizing power fueled by ein-ordnen the Other, making them eins with one-self. Ethical encounters, then, have to be guided by a sense of ignorance, as we remain in/separate from the Other: Barad insists on the ‘in/’ in in/separate more than Lévinas would: ““others” are never very far from “us”; “they” and “we” are co-constituted and entangled through the very cuts “we” help to enact.” (Barad 2007: 179). And yet, some ignorance is essential for the ‘apart’ part: “This possibility of ignorance does not denote an inferior degree of consciousness, but is the very price of separation” (Lévinas 1979: 180), of not encountering the Other reductively. Yancy argues that exactly this possibility of ignorance is missing when encountering the Black Other:

Within the framework of whiteness, the black is not that Other whose being calls out for recognition, whose being awaits to explode and disrupt the self-identical sameness of whiteness. For whiteness admits of no ignorance vis-à-vis the black. Hence, there is no need for white silence, a moment of quietude that encourages listening to the black. There is no need for white self-erasure (or at least a form of selfbracketing) in the presence of blackness. (Yancy 2004: 12)

The ‘framework of whiteness’ is akin to the apparatuses of whiteness explored above: It measures and maps Blackness onto whiteness-sameness, producing unethical encounters because it ver-steht (stands in the way of) ‘the marvel of exteriority’, of that which must remain un-kn-ow-(n)-able to produce the positive alienation needed for ethically encountering the Other.

So how do we, as white people, become response-able in the face of our tendency to reduce the Other to the same? Lévinas might well argue that this tendency is present in human encounters generally. However, white understanding happens from a hegemonic position of sociopolitical, economic and racial dominance (from the position of the measuring subject in the apparatus), which we are implicated in and profit from. It is therefore pertinent to become response-able to the counter/productivity of white understanding specifically. In suggesting a response I am inspired by Matsuda (1991) and her method called ‘ask the other question’ that helps her attend to the intersectionality of oppression.[5] I turn Matsuda’s ‘asking the other question’ into ‘asking the Other questions’, questions that re-member the Other’s in/finity. When I hear something that I can relate to, where is the separation? When I think I have experienced or felt the same thing, where are the differences? When I think I understand something, where are the bits that I can never understand? Asking the Other questions may indeed be the way to follow one of the calls of the placard to understand that I will never understand; to un/understand. And, as Sarah summarizes: „Das ist so’n Ausgang um auch mal zuzuhören“ [That is a starting point to listen for a change].

Another avenue into response-ability is paved by the last building block of the placard: …but I stand with you that shifts white response-ability from reflective practices of listening and un/understanding to the material-discursive practice of under-standing: standing under the placard, carrying it to support the Other’s cause. This is what I decided to do a year after first encountering the placard in Leipzig.

6 The BLM protest apparatus and under-standing whiteness

Eventually, I created my own version of the placard (Figure 1) and went to the BLM protest in Berlin 2021 as both a researcher and a protestor. Therefore, my participation was pre-informed my experiences and observations might have little to do with those of other white protestors. However, I hope that my way of getting in touch with the BLM protest apparatus can help co-constitute, new learning assemblages (Toohey 2019) to help us grapple with how to encounter each other ethically within and beyond the protest space.

Placard created by the author, not identical to the one encountered in Leipzig but using the same wording.

A BLM protest is a racializing apparatus that contrasts with the apparatuses of whiteness dominant in Germany. Now Blackness emerges on the side of the measuring agencies, Black organizers set the terms for who moves where, speaks when and how, and Black speakers and artists take the stage, while the normally im/perceptible whiteness of members of the majority population who join cannot hide. Whiteness has to stop denying “its own potential to be Other (to be “the not-same”)” (Yancy 2004: 13) and to encounter the Other as Other from a position of ethico-onto-epistemological un/certainty. Here whiteness cannot be sure not to stand out, cannot be sure not to be judged on racial grounds. Here, whiteness is in un/comfortable trouble.

White people are not in a position to speak publicly at a BLM protest: “…the only voices that should be heard are Black voices.” (BLMB 2020) But like every-body, they can join the chants initiated by Black voices and they can show up with placards. Most placards I have seen could be, and are, carried by any-body. In White Silence is Violence; Black Lives Matter; Say Their Names and many more, there is no clear indexical relation between the subject positions Black and white and the carrying body. Instead, Black and white index addressee groups that could both in- or exclude the carrier of the placard. I understand that I will never understand but I stand with you is different. It only works with a white body – like mine. Carrying the placard as a participant in the protest apparatus that produces me as the measured object, as the white Other, I felt the ‘I’ to have an indexical and an affective dimension. It indexes the carrier of the placard: The ‘I’ does not index a group but me. It implicates me. When I was carrying the placard, the ‘I’ was the heaviest part. I became increasingly uncomfortable with the ‘I’, with my ‘I’. The measuring agencies in the BLM apparatus – the speakers and their speeches; the route through the city with its street signs and buildings that re-member violence against Black bodies; the placards; the banners; in short: the spatial repertoire of the BLM protest (Baynham and Lee 2019; Canagarajah 2018a; Pennycook and Otsuji 2015) – produce my I as an un/allied I. My I adds strength to the protest by showing up, and yet it also co-constitutes the white ‘we’ that perpetrates racism and makes the protests necessary in the first place. The subject position of perpetrator and ally is held together by the kind of whiteness BLM measures for: un/allied whiteness, un/comfortable whiteness. My ‘I’ was the part of the placard that I wished to delete or re-place. At least I wanted to stop under-standing it, to stop standing under it.

We leave the protest briefly to get a coke and something to snack on and I then leave my placard behind for people to find like I found it in Leipzig, but also because I felt I needed to get rid of it and be ‘only’ my body – or be a different body. (reflective field notes, 2.7.2021)

Of course this is the story I told myself at the time. But I think I was just tired of the trouble, tired of white under-standing, or rather: of under-standing whiteness. I need a break. I have to practice. And I get to practice. I also get to remove my-self from the few spaces in which I under-stand whiteness. The Black Other in Germany doesn’t get breaks. And what that’s like is what I will never understand.

7 In/conclusive trouble

Commenting on the hegemony of white scholars in applied linguistics, Pennycook asks why white scholars so at ease in the field (Pennycook 2021: 8). Considering what I have discussed in this paper I would say that one reason is the ontological certainty that white understanding, as a practice of the white listening (or: measuring) subject, comes with. Rarely are white ways of knowing and being challenged there where the study of language is at stake, which has historically been steeped in methodological whiteness, built as it is on representationalism, structuralism, expansionism and colonialism, separating language from everything embodied and worldly (Pennycook 2021). White understanding, that measures according to the parameters of Western science, ordnet the world and its languaging ein, also in applied linguistics, marginalizing the knowledge of (especially women) scholars of color (Kubota 2020). I have admittedly not centered such knowledges here. As a white scholar, Barad’s attempts to unsettle the Western canon from within have picked me up where I was and helped me to become un/settled – I remain settled in my comfortable faculty position inextricably entangled with whiteness, but hopefully unsettled enough to open up to different ways of knowing, being and writing. Most importantly, it has been helping me to find different ways of intra-acting with students, colleagues, friends and family who embody histories of racism which I, inevitably, have been co-producing through the cuts I help to enact. I hope there might be some inspiration in this for my white colleagues as well.

The encounter with the placard has pushed me to engage with various conversation partners in this paper, who have, in turn, made me attentive to the counter/productivity of white understanding in Germany. In the process, through measuring intra-actions that whiteness didn’t always control, I was briefly and fleetingly produced as an under-standing white person, a white person who stood under the weight of un/allied whiteness. Under-standing is an expression of being measured (instead of measuring) in which the white listening subject doesn’t usually find itself. Under-standing feels risky for me, the white subject, because I lose control over the measuring agencies and therefore I don’t know who I might become in a given measuring intra-action. This is the risk that comes with ethical encounters: the risk of being produced as some-body who one might not want to be. It is from this troubled position, from this un/kn-ow-n-(ed) subjectivity, that we have to become response-able to the call of the Other.

In apparatuses controlled by white measuring agencies a response could be to consciously ver-stehen (understand, but also stand in the way of) our kn-own, established measuring parameters, attempting to shift them for example by asking the Other questions. However, there where we under-stand, where we are measured and produced through the Other’s measuring intra-actions, the response is harder to imagine, exactly because the position of the (racially) measured object is so unusual for white people. How can we learn to respond as the white Other without re-instating a white understanding that shifts the measuring agencies and reliefs us of the weight of our own Otherness? One of the ways is to practice being in spaces where our racial hegemony is unsettled – whether these are protest spaces or the scholarship of colleagues of color from various fields, who have been fighting to unsettle the hegemony of whiteness in science production – where we are being measured, and where we can learn to just stay with the trouble (Haraway 2016) that entails, including our troubling privilege of being able to choose when to enter such spaces.

I also suggested that when we get in touch with, inter-rupt, sense, dis/entangle or pick up and carry words, we co-constitute ‘complex communication’ (Lugones 2006) through different stories, different analyses, different in/conclusive worlds. We must handle these wor(l)ds as our ethical responsibility. Every dash, every slash reminds us of the tendency of our scholarly writing to make things absolute, to argue for or against, to summarize rather than disperse, to conclude rather than to open up. By treating words like einordnen, verstehen and understand the way I did in this paper, my aim was to open up critical conversations in applied linguistics around how we approach words and language and how this might limit the imaginations for new futures that our work can inspire.

References

Ahyoud, Nasiha, Joshua K. Aikins, Samera Bartsch, Naomi Bechert, Daniel Gyamerah & Lucienne Wagner. 2018. Wer nicht gezählt wird, zählt nicht: Antidiskriminierungs-und Gleichstellungsdaten in der Einwanderungsgesellschaft – eine anwendungsorientierte Einführung. Berlin: Citizens For Europe.Search in Google Scholar

Alim, H. Samy. 2016. Introducing raciolinguistics: Racing language and languaging race in hyperracial times. In H. Samy Alim, John R. Rickford & Arnetha F. Ball (eds.), Raciolinguistics: How language shapes our ideas about race, 33–50. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190625696.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

Alim, H. Samy, Angela Reyes & Paul V. Kroskrity. 2020. The field of language and race: A linguistic anthropological approach to race, racism, and racialization. In H. Samy Alim, Angela Reyes & Paul V. Kroskrity (eds.), The Oxford handbook of language and race, 1–23. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190845995.013.1Search in Google Scholar

Alim, H. Samy, John R. Rickford & Arnetha F. Ball (eds.). 2016. Raciolinguistics: How language shapes our ideas about race. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190625696.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Alim, H. Samy & Geneva Smitherman. 2012. Articulate while Black: Barack Obama, language, and race in the U.S. New York: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Barad, Karen M. 2007. Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.10.2307/j.ctv12101zqSearch in Google Scholar

Barad, Karen. M. 2010. Quantum entanglements and hauntological relations of inheritance: Dis/continuities, SpaceTime enfoldings, and justice-to-come. Derrida Today 3(2). 240–268. https://doi.org/10.3366/drt.2010.0206.Search in Google Scholar

Barad, Karen M. 2019. After the end of the world: Entangled nuclear colonialisms, matters of force, and the material force of justice. Theory & Event 22(3). 524–550.Search in Google Scholar

Barad, Karen M. & Daniela Gandorfer. 2021. Political desirings: Yearnings for mattering (,) differently. Theory & Event 24(1). 14–66. https://doi.org/10.1353/tae.2021.0002.Search in Google Scholar

Baynham, Mike & Tong K. Lee. 2019. Translation and translanguaging. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315158877Search in Google Scholar

BLMB. 2020. Things to consider if you are joining A demo as A non-black person. https://www.blacklivesmatterberlin.de/things-to-consider-if-you-are-joining-a-demo-as-a-non-black-person/ (accessed May 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Bock, Zannie & Christopher Stroud. 2019. Zombie landscapes: Apartheid traces in the discourses of young South Africans. In Amiena Peck, Christopher Stroud & Quentin Williams (eds.), Making sense of people and place in linguistic landscapes, 11–28. London: Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Butler, Judith. 2005. Giving an account of oneself. New York: Fordham University Press.10.5422/fso/9780823225033.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, Suresh. 2018. Materializing ‘competence’: Perspectives from international STEM scholars. The Modern Language Journal 102(2). 268–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12464.Search in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, Suresh. 2018a. Translingual practice as spatial repertoires: Expanding the paradigm beyond structuralist orientations. Applied Linguistics 39(1). 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx041.Search in Google Scholar

Cavanaugh, Jillian R. & Shalini Shankar (eds.). 2017. Language and materiality: Ethnographic and theoretical explorations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316848418Search in Google Scholar

CERD. 2015. CERD/C/DEU/CO/19–22: Concluding observations on the combined nineteenth to twenty-second periodic reports of Germany. Geneva: United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner.10.18356/3665860c-enSearch in Google Scholar

Cushing, Ian & Julia Snell. 2022. The (white) ears of Ofsted: A raciolinguistic perspective on the listening practices of the schools inspectorate. Language in Society 52(3). 363–386. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404522000094.Search in Google Scholar

DiAngelo, Robin. 2018. White fragility: Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism. Boston: Beacon Press.Search in Google Scholar

Die Bundesregierung: Die Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Migration, Flüchtlinge und Integration. 2023. Lagebericht: Rassismus in Deutschland. https://www.integrationsbeauftragte.de/resource/blob/1864320/2157012/77c8d1dddeea760bc13dbd87ee9a415f/lagebericht-rassismus-komplett-data.pdf?download=1 (accessed March 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Emde, Helga. 1986. Als Besatzungskind im Nachriegsdeutschland. In Katharina Oguntoye, May Ayim, Dagmar Schultz & Audre Lorde (eds.), Farbe bekennen: Afro-deutsche Frauen auf den Spuren ihrer Geschichte, 103–114. Berlin: Orlanda Frauenverlag.Search in Google Scholar

Flores, Nelson & Jonathan Rosa. 2015. Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review 85(2). 149–171. https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149.Search in Google Scholar

Flores, Nelson & Jonathan Rosa. 2022. Undoing competence: Coloniality, homogeneity, and the overrepresentation of whiteness in applied linguistics. Language and Learning 73(S2). 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12528.Search in Google Scholar

Flores, Nelson, Amelia Tseng & Nicholas Subtirelu. 2021. Bilingualism for all or just for the rich and white? Introducing a raciolinguistic perspective to dual-language education. In Nelson Flores, Amelia Tseng & Nicholas Subtirelu (eds.), Bilingualism for all: Raciolinguistic perspective to dual-language education in the United States, 1–18. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.22730640.4Search in Google Scholar

Gramling, David. 2022. On reelecting monolingualism: Fortification, fragility, and stamina. Applied Linguistics Review 13(1). 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2019-0039.Search in Google Scholar

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.10.2307/j.ctv11cw25qSearch in Google Scholar

Harm, Volker. 2003. Zur semantischen Vorgeschichte von dt. verstehen, e. understand und agr. έπίστααι. Historische Sprachforschung/Historical Linguistics 116(1). 108–127.Search in Google Scholar

Hasters, Alice. 2019. Was weiße Menschen nicht über Rassismus hören wollen aber wissen sollten. München: Carl Hanser Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Inoue, Miyako. 2003. The listening subject of Japanese modernity and his auditory double: Citing, sighting, and siting the modern Japanese woman. Cultural Anthropology 18(2). 156–193. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.2003.18.2.156.Search in Google Scholar

Juelskjær, Malou & Nete Schwennesen. 2012. Intra-active entanglements – an interview with Karen Barad. Kvinder, Køn & Forskning 1–2. 10–23. https://doi.org/10.7146/kkf.v0i1-2.28068.Search in Google Scholar

Kubota, Ryuko. 2020. Confronting epistemological racism, decolonizing scholarly knowledge: Race and gender in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics 41(5). 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz033.Search in Google Scholar

Krause-Alzaidi, Lara-Stephanie. forthcoming. Encounters with Black Lives Matter protest placards in Germany: Towards productive racialization? In Ashraf Abdelhay, Christine G. Severo & Sinfree Makoni (eds.), Sociolinguistics of protesting. Boston: De Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Lévinas, Emmanuel. 1979. Totality and infinity: An essay on exteriority. Martinus Nijhoff philosophy texts. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Lévinas, Emmanuel. 1985. Ethics and infinity: Conversations with Philippe Nemo. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lugones, María. 2006. On complex communication. Hypatia 21(3). 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1353/hyp.2006.0030.Search in Google Scholar

Makoni, Sinfree, Unyierie Angela Idem & Stephanie Rudwick. 2023. Decolonizing applied linguistics in Africa and its diasporas: Disrupting the center. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2023.2255324.Search in Google Scholar

Matsuda, Mari J. 1991. Beside my sister, facing the enemy: Legal theory out of coalition. Stanford Law Review 43. 1183–1192. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229035.Search in Google Scholar

Nakassis, Constantine V. 2018. Indexicality’s ambivalent ground. Signs and Society 6(1). 281–304. https://doi.org/10.1086/694753.Search in Google Scholar

Ogette, Tupoka. 2017. exit RACISM: Rassismuskritisch denken lernen. Münster: Unrast.Search in Google Scholar

Oguntoye, Katharina, May Ayim, Dagmar Schultz & Audre Lorde (eds.). 1986. Farbe bekennen: Afro-deutsche Frauen auf den Spuren ihrer Geschichte. Berlin: Orlanda Frauenverlag.Search in Google Scholar

Oldani, Martina & Naomi Truan. 2022. Navigating the German school system when being perceived as a student ‘with migration background’: Students’ perspectives on linguistic racism. Linguistics and Education 71. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2022.101049.Search in Google Scholar

Pennycook, Alastair. 2018. Posthumanist applied linguistics. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315457574Search in Google Scholar

Pennycook, Alastair. 2018a. Applied linguistics as epistemic assemblage. AILA Review 31(1). 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1075/aila.00015.pen.Search in Google Scholar

Pennycook, Alastair. 2021. Critical applied linguistics: A critical re-introduction. New York, London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003090571Search in Google Scholar

Pennycook, Alastair & Emi Otsuji. 2015. Metrolingualism: Language in the city. London, New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315724225Search in Google Scholar

Prinsloo, Mastin. 2022. Moving dirt: Relationality and complementarity of domestic work/ers. Journal of Postcolonial Linguistics 7. 89–107.Search in Google Scholar

Rosa, Jonathan & Nelson Flores. 2017. Unsettling race and language: Toward a raciolinguistic perspective. Language in Society 46(5). 621–647. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404517000562.Search in Google Scholar

Spivak, Gayatri C. 1994. Can the subaltern speak? In Patrick Williams & Laura Chrisman (eds.), Colonial discourse and post-colonial theory: A reader, 66–111. New York: Columbia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Toohey, Kelleen. 2019. The onto-epistemologies of new materialism: Implications for applied linguistics pedagogies and research. Applied Linguistics 40(6). 937–956. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amy046.Search in Google Scholar

Wiese, Heike. 2017. Die Konstruktion sozialer Gruppen: Fallbeispiel Kiezdeutsch. In Eva Neuland & Peter Schlobinsky (eds.), Handbuch Sprache in sozialen Gruppen, 331–351. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110296136-017Search in Google Scholar

Wiese, Heike, Katharina Mayr, Phillipp Krämer, Patrick Seeger, Hans-Georg Müller & Verena Mezger. 2017. Changing teachers’ attitudes towards linguistic diversity: Effects of an anti-bias programme. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 27(1). 198–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12121.Search in Google Scholar

Wright, Michelle M. 2003. Others-from-within from without: Afro-German subject formation and the challenge of a counter-discourse. Callaloo 26. 269–305.10.1353/cal.2003.0065Search in Google Scholar

Yancy, George. 2004. Fragments of a social ontology of whiteness. In George Yancy (ed.), What white looks like: African-American Philosophers on the whiteness question, 1–24. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203499719Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Special Issue 1 : Applied Linguistics, Ethics and Aesthetics of Encountering the Other; Guest Editors: Maggie Kubanyiova and Angela Creese

- Introduction

- Introduction: applied linguistics, ethics and aesthetics of encountering the Other

- Research Articles

- “When we use that kind of language… someone is going to jail”: relationality and aesthetic interpretation in initial research encounters

- The humanism of the other in sociolinguistic ethnography

- Towards a sociolinguistics of in difference: stancetaking on others

- Becoming response-able with a protest placard: white under(-)standing in encounters with the Black German Other

- (Im)possibility of ethical encounters in places of separation: aesthetics as a quiet applied linguistics praxis

- Unsettled hearing, responsible listening: encounters with voice after forced migration

- Special Issue 2: AI for intercultural communication; Guest Editors: David Wei Dai and Zhu Hua

- Introduction

- When AI meets intercultural communication: new frontiers, new agendas

- Research Articles

- Culture machines

- Generative AI for professional communication training in intercultural contexts: where are we now and where are we heading?

- Towards interculturally adaptive conversational AI

- Communicating the cultural other: trust and bias in generative AI and large language models

- Artificial intelligence and depth ontology: implications for intercultural ethics

- Exploring AI for intercultural communication: open conversation

- Review Article

- Ideologies of teachers and students towards meso-level English-medium instruction policy and translanguaging in the STEM classroom at a Malaysian university

- Regular articles

- Analysing sympathy from a contrastive pragmatic angle: a Chinese–English case study

- L2 repair fluency through the lenses of L1 repair fluency, cognitive fluency, and language anxiety

- “If you don’t know English, it is like there is something wrong with you.” Students’ views of language(s) in a plurilingual setting

- Investments, identities, and Chinese learning experience of an Irish adult: the role of context, capital, and agency

- Mobility-in-place: how to keep privilege by being mobile at work

- Shanghai hukou, English and politics of mobility in China’s globalising economy

- Sketching the ecology of humor in English language classes: disclosing the determinant factors

- Decolonizing Cameroon’s language policies: a critical assessment

- To copy verbatim, paraphrase or summarize – listeners’ methods of discourse representation while recalling academic lectures

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Special Issue 1 : Applied Linguistics, Ethics and Aesthetics of Encountering the Other; Guest Editors: Maggie Kubanyiova and Angela Creese

- Introduction

- Introduction: applied linguistics, ethics and aesthetics of encountering the Other

- Research Articles

- “When we use that kind of language… someone is going to jail”: relationality and aesthetic interpretation in initial research encounters

- The humanism of the other in sociolinguistic ethnography

- Towards a sociolinguistics of in difference: stancetaking on others

- Becoming response-able with a protest placard: white under(-)standing in encounters with the Black German Other

- (Im)possibility of ethical encounters in places of separation: aesthetics as a quiet applied linguistics praxis

- Unsettled hearing, responsible listening: encounters with voice after forced migration

- Special Issue 2: AI for intercultural communication; Guest Editors: David Wei Dai and Zhu Hua

- Introduction

- When AI meets intercultural communication: new frontiers, new agendas

- Research Articles

- Culture machines

- Generative AI for professional communication training in intercultural contexts: where are we now and where are we heading?

- Towards interculturally adaptive conversational AI

- Communicating the cultural other: trust and bias in generative AI and large language models

- Artificial intelligence and depth ontology: implications for intercultural ethics

- Exploring AI for intercultural communication: open conversation

- Review Article

- Ideologies of teachers and students towards meso-level English-medium instruction policy and translanguaging in the STEM classroom at a Malaysian university

- Regular articles

- Analysing sympathy from a contrastive pragmatic angle: a Chinese–English case study

- L2 repair fluency through the lenses of L1 repair fluency, cognitive fluency, and language anxiety

- “If you don’t know English, it is like there is something wrong with you.” Students’ views of language(s) in a plurilingual setting

- Investments, identities, and Chinese learning experience of an Irish adult: the role of context, capital, and agency

- Mobility-in-place: how to keep privilege by being mobile at work

- Shanghai hukou, English and politics of mobility in China’s globalising economy

- Sketching the ecology of humor in English language classes: disclosing the determinant factors

- Decolonizing Cameroon’s language policies: a critical assessment

- To copy verbatim, paraphrase or summarize – listeners’ methods of discourse representation while recalling academic lectures