Abstract

This study explores how interlocutors from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds employ the five translingual negotiation strategies of envoicing, recontextualization, interactional activity, entextualization and transmodality to communicate in online marketplaces. Informed by conversation analysis and translingualism, three computer-mediated communication (CMC) data sets were analyzed. Findings are as follows: 1) Korean speaker’s envoicing strategy was used to reveal his non-native English speaker status, which softened the impression of discourtesy. It set the co-constructed conversation stage where English speaking counterparts would be implicitly requested to speak more intelligibly; 2) recontextualization strategy was presented through emojis, emoticons, transliteration and translation to turn a business transaction into a friendly conversation between translingual speakers from different cultures where non-verbal cues of hospitality can be delivered in written forms in online one-on-one chats; 3) interactional strategy was observed when speakers did not share a culturally-bounded speech act of “conversation closers.” Misalignment was partially solved by mutual efforts to close their online conversation; 4) entextualization strategy was shown from Korean speakers’ asynchronous communication to confer on appropriate English expression by seeking help from other online community members; and, 5) transmodal strategy refers to the practice of shuttling among different on/offline modes and platforms to encode and decode languages, emotions, and cultural perspectives by depending on a wide range of resources and multiple strategies to accomplish meaningful interaction in online marketplaces. This study shows the translingual characteristics of English-medium online communication, suggesting an extended model of translingual meaning negotiation strategies in CMC contexts.

1 Introduction

Advances in computer and mobile technology has not only blurred the boundaries of countries around the globe but also changed modes of communication as transnational and translingual communication using multimodal resources. This phenomenon has become a part of everyday interactions. In this new era, English is the most common medium of communication among speakers of different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Despite a critical view of the terms, (e. g. Phillipson 1992, Phillipson 2009), the phrases English as an international language (EIL) (McKay 2002, McKay 2018) and English as a lingua franca (ELF) (Cogo and Dewey 2012; Jenkins 2009; Seidlhofer 2009) are commonly used. These designations capture the phenomenon of communicative interactions among diverse English speakers, who strive to achieve alignment (Canagarajah 2013) among their varieties of the common language in order to engage in conversation that is mutually understandable.

Transnational and translingual English-medium conversations among speakers of different languages frequently occur as chat in an online marketplace. Such computer-mediated communication (CMC), a term coined by Hiltz and Turoff (1978), or computer-mediated discourse (CMD) (Herring and Androutsopoulos 2015), has characteristics of both spoken and written discourse (Paltridge 2012). Online chat can be regarded as a spoken discourse in that speakers communicate in real time and thus must continually monitor the effects of their messages, for example, be alert to acts that might be construed as face-threatening. Also, it can be considered a written discourse because interlocutors use written communication, which may allow them to take more time than in spoken discourse to think of what to say while providing access to resources that can compensate for the lack of spoken discourse cues such as intonation, gestures, and facial expressions. Thus, online chat as a form of CMC can be located somewhere between spoken and written discourse. Moreover, CMC not only embraces characteristics of both discourses but also has its own discourse features to engage people, including the use of emojis and emoticons (Babin 2016), hashtags (Mulyadi and Fitriana 2018), hyperlinks, and online translators. These resources are used in communicative strategies which are easily employed by today’s youth, who were born in the late 1990s to early 2000s and are often referred to as Digital Natives (Prensky 2001), iGen (Twenge 2017) or Generation Z (Geck 2007), of the digital literacy era.

Much research has investigated CMC among speakers of different L1s in both casual and academic contexts (e. g. Belz and Kinginger 2002, Belz and Kinginger 2003; Kim and Brown 2014). These studies have revealed characteristics of CMC patterns (Herring 1996; Herring and Androutsopoulos 2015) and linguistic behaviors that are unique to CMC (Davies 2011). Little research, however, has explored how multilingual speakers use English in the online marketplace and what strategies they employ to negotiate meaning and achieve successful communication. This is a noteworthy gap in that e-commerce today is now part of daily life, especially among the youth generation whatever their levels of English proficiency. Moreover, unlike academic settings, in which communication in English has constructed discipline-specific features that help bridge varieties of English, communications in the online marketplace are relatively spontaneous and free-styled with the help of such social skills as face-work (e. g. request and refusal etiquette, apologies, expressions of gratitude, etc.). In addition, communications in the online marketplace are often initiated by a consumer seeking the solution to a problem without the benefit of a face-to-face interaction. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that CMC in the online marketplace creates a different type of conversation from that occurring in other contexts.

In this vein, this study is an investigation of how Korean translingual speakers and their English speaking interlocutors used translingual strategies to co-construct meaningful communication in online marketplaces. The study was guided by the following questions:

How do Korean speakers and their English speaking interlocutors employ the five translingual negotiation strategies of envoicing, recontextualization, interactional activity, entextualization and transmodal strategy to communicate in online marketplaces?

How are the characteristics of online real-time chat understood from the perspective of translingualism?

In the following section, the characteristics of CMC are summarized, followed by Canagarajah’s (2013) views on translingual practices involving multilingual English speakers’ uses of available resources for communication (e. g. shuttling between languages).

2 Theoretical perspectives on English speakers and CMC context

Much academic discussion on the role of English and literacy practices and events in today’s era of globalization has urged a paradigm shift from English as a system to English as a social practice among individuals, communities, and discourses (Canagarajah 2013; Pennycook 2010; Saraceni 2015; Li 2018; Yano 2009), including CMC discourse, which is often mediated in English and in which participants show the ability to find and deploy various available resources as they “shuttle between” (Canagarajah 2013: 79) communication modes and discourses.

2.1 Previous studies on computer-mediated communication (CMC)

Having, as mentioned above, characteristics of both spoken and written discourse (Paltridge 2012; Paolillo and Zelenkauskaite 2013), CMCs in the online marketplace are construed in this study as contact zones in which translingual online chats are synchronously and asynchronously exchanged between sellers and buyers, creating meaning-negotiation situations with the potential of entailing conflicts instigated by linguistic and cultural differences (Pratt 1991). This approach differs from those used in previous studies on CMC, which have analyzed efforts of international companies to accommodate the needs of their transnational and transcultural customers (Martin 2011); the teaching and learning English for multilingual speakers using the online public space of social network services (SNSs) such as Blogs, Wikis, Facebook or Twitter (Flanagan et al. 2014; Reinhardt 2019); and one-on-one chat in online library reference services (Foley 2002; Shachaf 2008; Shachaf et al. 2008). Here, by focusing on real-time chat between customers and sellers to achieve potentially problematic negotiations such as returning goods and canceling orders, the authors investigated CMC in what Murray (2000) has referred to as “the continuum of orality and literacy of CMC” (p. 400) and Herring and Androutsopoulos (2015) as featuring synchronous speech-like discourse structure “at the utterance level” (p. 131). These speech-like features, which often violate the grammatical rules of written discourse, are combined with the speed-pacing of real time chat among multilingual interlocutors whose focus is less on correctness of expression than on solving problems expeditiously, thus bringing out the wide range of communication strategies available in the online chat medium.

In this investigation of a type of interaction of commercial transactions becoming increasingly common in online contexts, the translingualism lens provided a theoretical framework through which to capture sophisticated implicit/explicit meaning negotiation strategies in detail as well as interlocutors’ ability to shuttle between modes/platforms.

2.2 Translingual meaning negotiation strategies

As the international status of English affects all actors in the global marketplace, meaning necessarily takes precedence over form (Canagarajah 2007). Moreover, as Canagarajah (2013) has also stressed, the globalization of English has blurred the boundaries between nativeness and non-nativeness, particularly in the marketplace, as long as competency is sufficient to avoid misunderstanding and hindrance of business goals. As an example of such practical communication between two English users in a business setting, Canagarajah (2013) reinterprets a transcribed telephone conversation, originally presented in Firth and Wagner (2007), between an Egyptian cheese importer and a Danish cheese exporter. The Egyptian buyer complained that the dairy product purchased from the Danish company was “blowing,” an utterance that necessitated a meaning-making negotiation process because the Egyptian buyer was not familiar with an English idiom, “gone off,” for spoiled food that was used by the Danish cheese seller. Postulating that in this context “blowing” was derived from an Egyptian expression for spoiled food, Canagarajah shed light on the interlocutors’ subsequent meaning-making negotiation strategies to achieve their goal in this business interaction and called attention to the implicit influence of the individual’s native linguistic background on his/her of ELF.

The data from the online marketplace used in this study demonstrate the dynamics of Canagarajah’s (2013) four key translingual negotiation strategies of envoicing, recontextualization, interaction, and entextualization, to which we added a fifth strategy, transmodality, to capture translingual practices in the CMC contexts. First, envoicing refers to the ways speakers encode their linguistic, cultural, and social identities into their language usage (Bakhtin 1986). Unlike other frameworks for intercultural communication, which have often focused on the practicality of meaning transfer from one language to another, translingualism approaches language-in-use as expression of voice, for which translingual speakers inevitably face complicated decision-making moments in online synchronous conversation. Second, recontextualization may occur once speakers have envoiced their identities. This strategy is a framing process through which speakers’ intentions achieve a better position for uptake. In the language contact zone of online marketplaces, meaning-negotiation processes avert misunderstandings that might be caused by interlocutors’ different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Third, Canagarajah (2013) defines interactional strategy as “a social activity of co-constructing meaning by adopting reciprocal and collaborative strategies” which will be realized when “interlocutors match the language resources they bring with people, situations, objects, and communicative ecologies for meaning-making” (82). Fourth, entextualization refers to “how speakers and writers monitor and manage their productive processes by exploiting the spatiotemporal dimensions of the text” (Canagarajah 2013: 84). What speakers say and writers write in CMC are not only enactments of their identities and positioning for uptake but indications of their discourse-specific knowledge. Changes made during interactions reflect the language monitoring strategy of accommodating responses from other members of an online community.

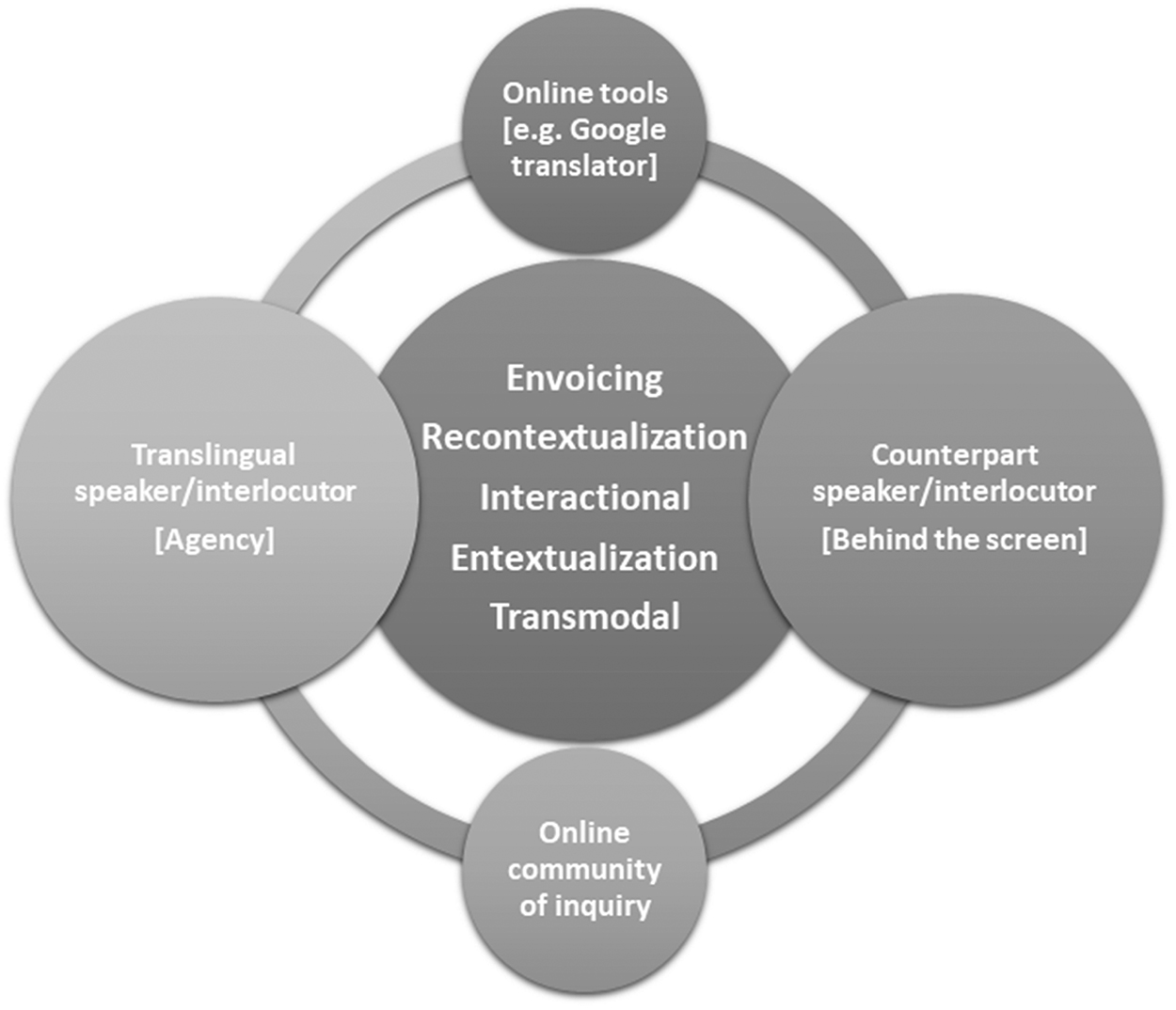

The fact that Canagarajah (2013) did not conceptualized the four translingual negotiation strategies to explore CMC discourse has left a space for this study to contribute to the field by proposing transmodal strategy in online marketplace transactions among translingual interlocutors (see Figure 1). The conceptual grounding of transmodality is not entirely new but is in line with previously suggested notions that seek to capture the creative ways in which meaning-makers exploit to visit diverse platforms that might have no obvious overlaps, to marshal multiple resources from disparate sources, and to actively code-mesh combinations of these resources to express themselves (Jewitt 2009; Kress 2000; Newfield 2009; Pennycook 2007; Wyatt-Smith and Kimber 2009). Following Li’s (2011, 2016, 2018) concepts of translanguaging space and translanguaging instinct, which emphasize enhanced contacts among various cultures and discourses to provide opportunities for new identities and creativity to emerge and merge, CMC is viewed as a translanguaging space wherein interlocutors’ translanguaging instinct regarding transmodality facilitates their moves across various online platforms as they pick up, combine, and re-form linguistic cues to represent their intended meanings efficiently. Today’s digital generation may well be equipped with this instinct in that they were exposed to new ways of being literate from a young age. Their familiarity with the use of digital devices for literacy practices provides the basis for naturally developing transmodality.

Translingual meaning negotiation strategies in CMC context.

3 Methods

3.1 Data sources and collection

Data consisted of postings shared among members of two online communities in Korea open for the public to read and make comments (see Table 1). These three sets of data of this study were derived from two large online communities in Naver.com in 2018 spring to fall. Table 1 provides an overview of the sources, interlocutors, situations, type of CMC systems and synchronicity of the communication data. Two data sets (no. 1 and no. 3) were selected from NikeMania (https://cafe.naver.com/sssw), an online community in which those interested in sports and street clothing brands such as Nike, Adidas, Supreme, and Palace exchange information, questions and answers about products, online purchases, returns and refunds, and many more issues involved in online transactions. Another data source (no. 2) was Mijunmo (https://cafe.naver.com/gototheusa), an online community of people preparing for study and work in the US, mostly married women who exchanged advice, often shopping tips, on living in the US.

An overview of the three data sets.

| Data Set No. | Data Source | Interlocutors | Situation | Type of CMC systems | Synchronicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NikeMania | Korean speaker & English speaking customer service staff | UPS customer service agent | Asking for tracking pants | 1:1 online chat | O |

| 2 | Mijunmo | Korean speaker & English speaking customer service staff | Winery customer service agent | Stopping a monthly wine subscription | 1:1 online chat | O |

| 3 | NikeMania | Among Korean online community users | Members of online communities through replies | Asking advice on writing an email about canceling an order | online posting and responses | X |

We manually assembled a corpus of postings that provided anecdotal illustrations of the challenges of communicating in English in online marketplaces. Postings were excluded if they were fragmentary or showed insufficient turn-takings. From this corpus, three cases were selected for the purpose of this study that presented the most visible meaning negotiations, two from customer service platforms and one from an online community bulletin board. These chats included questions about delivery tracking and canceling a wine subscription. One data set was drawn from NikeMania, a Korean online community in which members consulted with each other concerning the appropriateness of the wording of a communication with a customer service representative. These were selected to investigate the Korean English speakers’ understanding of communication in English as well as norms of communication emerging collaboratively among Korean speakers of English.

All names are pseudonyms, and no personal information is disclosed in discussions of or extracts from chats and postings. Therefore, use of the data can be considered ethically legitimate.

3.2 Data analysis

Following Lester and O’Reilly (2018) description of conversation analysis as examination of “the changing sequence of actions that occurs between individuals or groups of people” (p. 4), we used conversation analysis of CMC (González-Lloret 2013) to systematically explicate the sequences of interactions between Koreans and English speakers. When a candidate phenomenon, described by Lester and O’Reilly (2018) as “a tangible, viewable example of something within the data” (p. 160), was found, it was compared with phenomena within and between data sets to determine what the speakers intended to do and how their intentions were realized through negotiation strategies. Also we employed Herring and Androutsopoulos’s (2015) “seven-move schema for dyadic instant messaging conversations” (p. 133) as a lens to guide our focus during data analysis. As discussed above, along with methodological considerations, we drew theoretically upon Canagarajah’s (2013) model of translingual speakers’ meaning negotiation strategies (envoicing, recontextualization, interactional, and entextualization), which was extended to include our own suggestion, transmodal strategy.

In the analysis of online communications using the translingual meaning negotiation strategies framework, overlaps among translingual strategies were made visible, showing complementary relations. As Canagarajah (2013) pointed out, the strategies do not function independently; rather, they work together to accomplish meaning negotiation in translingual interactions. An utterance may play multiple strategic roles in a context in which previous and following turns also influence its function. Nevertheless, the findings are organized under Canagarajah’s four translingual meaning negotiation strategies and the one that emerged in this study as discrete categories in order to highlight the prominence of each strategy in relation to the others throughout the selected communications.

For identifying the meaning negotiation strategies used in the online marketplaces and understanding their contents, our positionality as researchers was also an important analytic tool within the linguistic and social context of this study. Our competencies in both Korean and English languages and cultures gave us insight into the unconventional and sometimes unintelligible English usages by Korean speakers and Korean usages by English-speaking customer service agents. Moreover, our theoretical orientation toward translingual practices led us to attend less to linguistic accuracy within a single turn; but more to the interactional strategies and socially and interactionally constructed messages conveyed and understood by the interlocutors. Thus, we used conversation analysis to focus on the range of translingual meaning negotiation strategies used in the communications between Korean speakers of English and English speaking interlocutors.

4 Findings

Translingual speakers of Korean and English actively participated in CMC, using Canagarajah’s (2013) translingual meaning negotiation strategies (envoicing, recontextualization, interactional and entextualization) to construct meaningful communications. In addition, a fifth strategy – transmodality – shows the dynamic nature of the translingual speakers’ literacy practices in online communications.

4.1 Envoicing

Speakers in online translingual contact zones employ envoicing strategies to communicate their personal and cultural identities to their interlocutors (Canagarajah 2013). For example, Lee, a Korean translingual speaker with relatively low English proficiency, used his non-native English speaker status as an envoicing strategy. In the excerpt below (Extract #1-1), Lee had just provided the tracking number of a purchase and asked Mark A about the shipping status of his order. When Mark A asked Lee about the contents of the order, Lee explicitly mentioned himself as a Korean speaker and thus non-native speaker of English.

Extract #1-1

| 35 | Mark A.: | May I know the contents please? |

| 36 | Lee: | What? What do you want me to tell you? |

| 37 | Lee: | I am not an American. I am a South Korean person. |

| 38 | Mark A.: | The contents of the package with the tracking number |

| 1Z****************. | ||

| 39 | Lee: | One pants. |

| 40 | Lee: | Are you asking for the contents? |

| 41 | Mark A.: | Thank you. I will send the investigation now. Please keep in touch with the shipper. They will be notified of the results as soon as the investigation is finalized. Claim results will only be discussed with the shipper. Again I’m sorry for the inconvenience. |

| 42 | Lee: | The set includes 1 pants |

When Lee did not understand what Mark A asked for, he directly asked “What?” followed immediately with “What do you want me to tell you?” (#36). This kind of blunt response, often made by low proficiency English speakers (Takahashi and Beebe 1987), might sound rude because native or more proficient English speakers would be likely to embed their uncertainty in polite phrasing such as apologies and modal verbs as hedges. However, the Korean speaker’s envoicing strategy of explaining he was not an American, confirmed by his odd phrasing, “I am a South Korean person” (#37), softened the impression of discourtesy in his initial response. Mark A’s next turn, in which he elaborated that he needed “the contents of the package with the tracking number” (#38), suggested that the envoicing strategy worked. And, Lee provided the answer, “One pants” (#39), and then checked to make sure if he was responding accurately by asking Mark A if he is looking for the contents (#40). After Mark A’s lengthy explanation (#41), Lee repeated in a full sentence, “The set includes 1 pants” (#42). Lee’s text contained phrasing, such as “1 pants,” that native or proficient speakers of English would be unlikely to use, but Mark A’s “let-it-pass” attitude, evident in his tolerance of linguistic mistakes as long as they did not interfere with intelligibility and his alertness to cues in the message (Firth 1996), allowed the interaction to succeed. It may reasonably be inferred that Lee’s envoicing strategy encoding his non-native speaker of English status and clarifying the relationship between the two speakers would set the stage for their co-constructed intelligibility.

4.2 Recontextualization

In a negotiation between parties from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, speakers need not only to make their intentions clear but also to frame their conversation to be easily understood. In the following online chat (Extract #2), this strategy was realized in three ways: the use of emojis and emoticons; the English speaker’s use of transliteration into the customer’s L1 (i. e. Korean); and the English speaker’s use of the customer’s L1.

The example below shows a situation in which Sunny, a Korean customer, wanted to cancel her wine delivery subscription, and Ashton, an English speaking customer service agent, tried to persuade her to keep it and skip a delivery whenever she wanted. However, when Sunny still wanted to cancel, Ashton complied, following which they bantered about his use of her language and used emojis and emoticons to express congeniality.

Extract #2

| 8 | Sunny: | My account is *********@naver.com |

| 9 | Ashton: | Gee, kamsa! I mean thank you! Just give me a moment here while I pull-up your account :) |

| (Turns not presented) | ||

| 15 | Sunny: | Yes. I want to get some wine randomly, not a regularly. That’s too many to me.TT |

| 16 | Ashton: | Omo! I understand, but you know, skipping can be done consecutively and unlimitedly, how about I skip your next month’s order? We also send notification and reminder e-mails to *********@naver.com, are you getting them by any chance? :3 |

| (Turns not presented) | ||

| 20 | Ashton: | Just give me a sec while I process your account’s cancellation :) |

| 21 | Sunny: | No problems. Thank you:D |

| 22 | Ashton: | munjega anida ;) |

| 23 | Ashton: | Not a problem Sunny ;) |

| 24 | Ashton: | I already canceled the account today, just check your e-mail |

| ********@naver.com within 24 hours for the cancellation e-mail. | ||

| 25 | Sunny: | Thank you! |

| 26 | Ashton: | 다른게 있니? |

| 27 | Ashton: | Is there anything else? ;) |

| 28 | Sunny: | I really appreciate:) |

| 29 | Sunny: | No. You can korean. Ha ha! Thank you:) |

| 30 | Ashton: | You’re welcome! By the way, if you want to reactivate the account, just place an order using the same e-mail and it will be reactivated. :) Have an awesome and cool day Sunny chinggu! Fighting!! |

| 31 | Sunny: |

Have a great time,too! |

| 32 | Ashton: | 너도 좋은 하루 되셨다! You have a nice day too ^^, |

| 33 | *** Ashton left the chat *** | |

The conversation between these two speakers contained various emoticons to express pleasant and regretful feelings such as :), :3. :D, ^^ and TT, and emojis such as  and

and  . As laughter and other sentiments can be a sign of uptake in face-to-face communication (Canagarajah 2013), online communication embodies emojis and emoticons for expressing feelings in CMC literacy practices (Davies 2006). These resources for expressing feelings were used at the end of almost every turn. When Ashton used the emoticon :) to signal a smile or friendliness in line #9, Sunny replied with the emoji TT to indicate tears or regret (line #10). Ashton used another smile emoticon, :3 (line #16) and Sunny responded with one suggesting a large grin, :D (line #21). Of particular interest, Ashton used “Fighting” (line #30), which is the Korean way of saying “go for it” or “good luck,” and bolstered its meaning by adding an emoji of biceps,

. As laughter and other sentiments can be a sign of uptake in face-to-face communication (Canagarajah 2013), online communication embodies emojis and emoticons for expressing feelings in CMC literacy practices (Davies 2006). These resources for expressing feelings were used at the end of almost every turn. When Ashton used the emoticon :) to signal a smile or friendliness in line #9, Sunny replied with the emoji TT to indicate tears or regret (line #10). Ashton used another smile emoticon, :3 (line #16) and Sunny responded with one suggesting a large grin, :D (line #21). Of particular interest, Ashton used “Fighting” (line #30), which is the Korean way of saying “go for it” or “good luck,” and bolstered its meaning by adding an emoji of biceps,  , to which Sunny responded with an emoji of a smile

, to which Sunny responded with an emoji of a smile  (#31). This use of image-based semiotics allowed the two speakers to create an amicable atmosphere to relieve possible tension in exchanging speech acts in a situation with negative aspects. This communication shows how a customer service agent and a customer recontextualized a potentially contentious situation by using language and symbols to turn a business transaction into a friendly conversation, leaving the door open, perhaps, for future business.

(#31). This use of image-based semiotics allowed the two speakers to create an amicable atmosphere to relieve possible tension in exchanging speech acts in a situation with negative aspects. This communication shows how a customer service agent and a customer recontextualized a potentially contentious situation by using language and symbols to turn a business transaction into a friendly conversation, leaving the door open, perhaps, for future business.

Ashton’s use of Korean contains such mistakes as incorrect word spacing and grammar errors. His “munjega anida” in line #22 seemed to be an attempt to say “Not a problem” in Korean, but this was not how native speakers of Korean would say it, suggesting he had put the English phrase into Google translator and obtained this result. Similarly, Ashton’s sentence “너도 좋은 하루 되셨다!” for “you too have a good day” shows the wrong use of the deferential ending, which would sound awkward to Korean speakers, again suggesting he received a verbatim translation for the English expression from an electronic translator.

Although Ashton’s and Sunny’s attempts to speak each other’s language include many errors, they did not hinder the smooth flow of the conversation between two interlocutors or evoke corrections from either side. Rather, Ashton’s use of recontextualization strategies, for instance, surprised and pleased Sunny, who responded delightedly in similarly flawed English, “You can Korean. Ha ha!” as seen in line #29. They were creating exchanges in which they were collaborators in a mutual effort to communicate emotional as well as semantic meanings across languages. In this effort, Ashton seemed to recognize that his Korean might be unclear by repeating the meaning of his Korean sentences in English as seen in lines #9, from #23 to #24, from #26 to #27, and #32.

This online chat in English between a Korean speaker and an English speaker demonstrates the recontexualization strategy. By sensitively and playfully responding to each other’s turns with the use of emoticons and emojis and translations, the two speakers bridged their different linguistic and cultural backgrounds by recontextualizing their communication to be conducive to friendly uptake and comprehension. This successful exchange was facilitated by the multimodal nature of an online translanguaging space (Li 2018), in which translingually-oriented speakers could draw upon a range of resources to construct communication that served both commercial and personal purposes.

4.3 Interactional

In the process of turn-taking, interlocutors put mutual effort into maintaining communication without breakdowns and to achieve alignment, for which, Canagarajah (2013) states, they “match the language resources they bring with people, situations, objects, and communicative ecologies for meaning-making” (82). The complexity of this interactional strategy may make it more vulnerable to problems, as shown Extract #1-2 below from a live chat between a Korean customer and an English speaking customer service agent. It demonstrates how different perceptions of a culturally-bounded speech act may create awkwardness between two speakers from different cultures. This extract captures the moment when two different “conversation closers” appear to unravel at the end of what had seemed to that point to be a successful conversation.

Extract #1-2

| 54 | Mark A | Is there anything else I can help you with aside from this? | |

| 55 | Lee | Next time I come toSouth Korea, I will buy delicious bulgogi ^ ^ Suwon is famous for ribs | |

| 56 | Mark A | Good for you can eat those. It’s my first time to hear those dishes | |

| 57 | Lee | Famous food in South Korea Bulgogi, Kimchi, Bibimbap | |

| 58 | Mark A | I know kimchi. But I don’t like the taste | |

| 59 | Lee | Bulgogi is very delicious | |

| 60 | Lee | Kimchi is also poetry | |

| 61 | Mark A | Really? I should try that some time | |

| 62 | Mark A | By the way I’m done sending the investigation request | |

| 63 | Lee | Yes, come to South Korea ^^ Call at Incheon International Airport 010-****-**** | |

| 64 | Lee | Thank you ^^ | |

| 65 | Mark A | No problem. I wish I could but I’m stuck here. HAHAA! | |

| 66 | Mark A | I guess we’re done. Is there anything else I can help you with today? | |

| 67 | Lee | If you do not know, if you have something to do in South Korea after you’ve saved it | |

| 68 | Lee | No you can quit now | |

| 69 | Lee | bye | |

| 70 | Lee | ^^ | |

| 71 | Mark A | Thank you for contacting us. Bye now |

While this conversation would seem to be successful in that it ended without problems, not only the Korean speaker’s unintelligible English sentences but also the speakers’ culturally different understanding of the way to finish a communication brought it to a rough finish. Mark A’s question in line #54 had two functions, to literally ask if he could offer further help, and to signal that their conversation was finished if there was no other request, a typical closing sentence in the English-speaking discourse of customer service. Lee’s answer (line #55) seems to have nothing to do with Mark A’s question because he started giving unrelated information about Korean dishes and a city (lines #57 to #60), interrupting Mark A’s move to finish their conversation. Moreover, Lee’s utterance in line #55 was confusing because he used “I” is an agent of the action “come to South Korea,” as if he were not already there, when he probably meant “you.” In addition, some of Lee’s comments, such as line #60, “Kimchi is also poetry,” would not be intelligible even if spoken in Korean to native speakers of Korean, which may be the result of a machine translation of a Korean sentence to English.

Lee’s unexpected deviant behavior above might be understood as an Asian speaker’s way of expressing politeness (e. g. House 2003) or as an expression of gratitude and reciprocity in that right after talking about Korean dishes, Lee even gave Mark A his phone number (line #63). Such a disclosure of personal information to a stranger would be considered inappropriate in many cultures. Moreover, it is not clear whether Lee’s sentence “Call at Incheon Airport 010-****-****” meant that Mark A should use the number to call the airport or to call Lee when he arrived at the airport. Nevertheless, no matter how perplexing this communication might have been to him, Mark A seems to have understood Lee’s intent of expressing thanks, because he answered casually, indicating a smile by writing “HAHAA” with an exclamation mark (line #65).

When Mark A’s intention to finish their conversation did not work, he explicitly stated it was over if there were no more questions (line #66), to which Lee responded directly saying “No you can quit now” and “bye” (lines #68 and #69), which again may sound very abrupt to a native speaker of English but could be understood as a literal transfer of meaning from Korean to English with the intention of meaning something like “no, I’m good.” Lee signaled, again, his amicable attitude towards their conversation by adding the Korean emoticon of a smile, ^^, in line #70.

When speakers of different L1s communicate in English-medium online conversations, the second/foreign/additional language speaker utilizes not only linguistic but also cultural and pragmatic knowledge of his/her own (Lee 2006). To participate in interactions that may require complex speech acts, non-native speakers are culturally aware that they need to take extra measures to show their politeness and avoid face threatening acts; however, their lack of linguistic as well as pragmatic knowledge sometimes leads them to “use erroneous language forms and produce speech acts that sound deviant or even create communication failure” (Olshtain and Cohen 1989: 62). In this communication, Lee may have been seeking ways to say goodbye and express his gratitude to Mark A for doing his best to solve the problem. In responding to Mark A’s intended closing statement by talking about meals or hosting Mark A in a hypothetical future visit to Korea, Lee was reflecting greeting and farewell expressions common in many Asian cultures, including Korea and China, which often include talking about food (Lee 2018). But whereas Koreans’ fond farewell is usually expressed by saying “let’s have a meal some time” (Chung 2018), Lee’s conversation closer here was much longer and detailed than usual, which from the Korean perspective could be interpreted as his desire to show how grateful he was to Mark A.

While the conversation between the two parties ended with a successful resolution to a problem that might have involved miscommunication, it demonstrated misalignment, particularly Lee’s seemingly irrelevant deviations into talk of food and travel at the end, elements of the chat that Mark A deflected while focusing on the issue at hand. Thus, there were failed interactional strategies within the exchange that were probably attributable to the parties’ lack of shared cultural understanding.

4.4 Entextualization

Entextualization, which includes the inscription of speech into writing, is a strategy by which online communicators encode their speaking voices into a text. Canagarajah (2013) referred to this relatively macro-strategy as showing “how speakers and writers monitor and manage their productive processes by exploiting the spatio-temporal dimensions of the text” (84).

Email is a commonly used medium in which people encode their spoken language into written forms, which can be a difficult task for English learners. For example, determining the best approach to communicating a speech act of request (Biesenbach-Lucas 2007), not to mention writing an appropriately worded email message, can be challenging, especially for those with low levels of English proficiency. Unable to use complicated structures or nuanced language, these speakers are likely to use direct expressions (Takahashi and Beebe 1987), which may seem rude to native speakers. As shown below, aware of this possibility, a Korean customer posted a query on an online community board asking whether it was okay to say “I’m sorry but I will cancel. If you do not refund $ 10 shipping” (line #1), explaining that he was not good at English and thus had used a Google translator. In response, people in the community pointed out the connotations of his sentences and suggested better ways to express what he intended to say.

In the following Extract 3, the Korean data are presented in their original form followed by translation into English in square brackets. Numbers indicate turns and small alphabet letters identify different speakers.

Extract 3

| 1 | a | I’m sorry but I will cancel. If you do not refund $ 10 shipping |

| 2 | 라고 보내면 취소 되나요? 영알못이라… 구글번역돌린건뎅 | |

| [will it be canceled if I say like this? I am not good at English… I used a Google translator] | ||

| 3 | b | 너무 직역으로 돌리신거 같은데 [it seems like you translated too literally] |

| 4 | 상대 입장에선 좀 협박성으로 들릴 여지도 있을거 같네요 | |

| [To a listener, it might sound threatening] | ||

| 5 | 취소하실거면 굳이 특별한 이유 안들어도 그냥 취소하겠다고만 하면 해줄거에요… [if you want a cancellation, they might do it if you say you just want to cancel it without mentioning specific reasons] | |

| 6 | a | Hi SNS |

| I’m sorry, I will cancel. | ||

| Do not speak English well | ||

| Google translation use | ||

| 7 | 이렇게 보냈는데 괜찮을까영;; [If I sent it like this would it be okay] (the function of semicolon ; is to describe sweating which is often used by Koreans to show their embarrassment) | |

| 8 | c | Hi, Could you cancel my order please? My order # is xxxxx |

| 9 | 라고만 보내시면 될것같으세요 [just saying the aformentioned sentence will be okay] | |

| 10 | d | 그냥 캔슬해달라고 하세요. if부터 뒤에는 빼시고.. |

| [You’d better just ask to cancel the order and do not include the content from “If…”] | ||

| 11 | e | 저거는 글쓴분이 부탁하는 입장인데 상대방 기분나쁘게 협박하는겁니다 |

| [Although the writer is making a request, that sentence is threatening the other party offensively] | ||

| 12 | h | 그냥 심플하고 공손하게 취소해 달라고 하세요 |

| [Just simply and politely ask to cancel] |

This communication, in which Korean speakers conferred on appropriate ways to write an email request for an order cancellation in English, illustrates the nature of entextualization strategies in online translanguaging space. Unlike synchronous online live chat between English speaking customer service agents and Korean speakers, in which adjustments can be made during communications, they had to consider the effects of putting the words in writing and dealing with Korean to English translation issues. By commenting that writer a’s original sentence might sound intimidating if not threatening (lines #3-4, #10, #11, and #12) and suggesting polite ways to make the request (line #8) or simply asking for cancellation (line #10), the respondents highlighted the face-threatening possibilities in non-face-to-face communications. The writer’s use of Google translator (line #2) is a common strategy of non-native speakers of English, but what is interesting from a translingual perspective was his dependence on other online community members to monitor his entextualization process by checking whether his message conveyed his intended disposition as well as meaning. This example shows how translingual speakers behave differently in asynchronous and synchronous communication discourse, as the former provides time and space for acts of monitoring and gathering collective intelligence to make a better product and so can be expected to meet a higher standard of appropriateness.

4.5 Transmodality

Transmodality is a CMC-specific strategy that is drawn from our own data sets. Transmodality, which may also partly encompass other strategies, refers to the practice of shuttling among different on/offline modes and platforms to encode and decode languages, emotions, and cultural perspectives. This strategy is particular to CMC in that the CMC discourse not only combines characteristics of spoken expression and written discourse but also because online communication offers a wide range of resources and multiple strategies for accomplishing meaningful interaction.

As seen from the data presented above, in CMC speakers encode their spoken into written language while referring to such aids as online translators (Extract 1–2). Moreover, expressing emotions in CMC as shown in Extract 2 also requires speakers to convert their physical features and behaviors (e. g. smiling, laughing, crying) into non-verbal, written representations (i. e. emoticons and emojis). In cross-cultural and language situations, such conversions require interlocutors to consider the cultural differences among the parties. In addition, as shown in an asynchronous communication on the online bulletin board of a Korean street clothing brands community (Extract 3), a request for collective knowledge to answer a question can promote intellectual convergence (Harasim 2012) by changing an information exchange space to a site for online collaborative learning (OCL). Transmodality, in the extract above, not only allowed the person who posted the question to monitor his language by referring to his own knowledge and an online translator, but also rendered his communication and call for feedback from other members into a collaborative learning space.

Transmodality, therefore, expands Canagarajah’s (2013) translingual meaning negotiation strategies by capturing translingual speakers’ online communication strategies that involve shuttling among languages, cultures, and multiple modes/platforms. By these means, interlocutors can combine and transform multimodal resources to achieve a level of clarity that, in instantaneous spoken or written online interactions, would be difficult to reach if they depend only on their own linguistic competence.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we explored how translingual speakers with different cultural and linguistic backgrounds engaged in meaning negotiation processes in online marketplaces and how their translingual communicative strategies were employed to meet their goals in various situations. Korean speakers tried to achieve their communication goals through the use of five translingual negotiation strategies, for example, employing envoicing strategies such as positioning themselves as non-native speaker of English or using Google translator. Also, their English-speaking interlocutors managed their communications with Koreans using their own meaning negotiation strategies, such as recontextualization, including code-switching to the other party’s language or the use of emoticons and emojis, which can be understood without linguistic knowledge. While translingual speakers confront failures of communication, often due to cultural differences, in cases where the central issue is not at stake, these breakdowns can be appropriately addressed with interactional strategies such as a “let-it-pass” (Firth 1996) strategy on the listener’s part and repeated expressions of friendly reciprocity by the speaker. Moreover, Korean speakers of English may use their collective knowledge of English to suggest entextualization strategies, for example, to help a compatriot appropriately compose a sensitive message, such as an asynchronous request to cancel an order. In addition, as found in this study, transmodal strategies, which take advantage of the wide range of resources available in online contexts, enable speakers to exploit diverse affordances for effective communication.

The findings of this study help make visible the ways in which speakers of different languages interact in online e-commerce chat, particularly how interlocutors collaborate to understand each other and to keep their conversation going smoothly by using online resources and their personal knowledge of their counterparts’ linguistic and cultural information. The online chat utterances of non-native speakers shown above had errors and unconventional expressions that, while they might be problematic from a normative grammar perspective, were sufficiently communicative in real-time online chat, revealing the effectiveness of the speakers’ meaning negotiation strategies. From the perspective of translingualism, what is important is the performative nature of the interlocutors’ interactions as they endeavor to actively participate in the conversation. That is, the essence of translingual literacy practices does not lie in whether utterances are linguistically correct or appropriate in terms of standard written or spoken English norms, but in how speakers participate in mutually constructed real-time discourse, in which the norms of language usage emerge from their interactions.

Funding statement: This study was unfunded.

-

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest to be declared.

References

Babin, J. J. 2016. A picture is worth a thousand words: Computer-mediated communication, emojis and trust. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2883578 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2883578.Suche in Google Scholar

Bakhtin, M. M. 1986. Speech genres and other late essays. Trans. V. W. McGee. Austin: University of Texas Press.10.3138/cmlr.59.2.189Suche in Google Scholar

Belz, J. & C. Kinginger. 2002. The cross-linguistic development of address form use in telecollaborative language learning: Two case studies. Canadian Modern Language Review 59(2). 189–214. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.59.2.189.Suche in Google Scholar

Belz, J. A. & C. Kinginger. 2003. Discourse options and the development of pragmatic competence by classroom learners of German: The case of address forms. Language Learning 53(4). 591–647. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-9922.2003.00238.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Biesenbach-Lucas, S. 2007. Students writing emails to faculty: An examination of e-politeness among native and non-native speakers of English. Language Learning & Technology 11(2). 59–81. http://llt.msu.edu/vol11num2/biesenbachlucas/.10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00678.xSuche in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, A. S. 2007. Lingua franca English, multilingual communities, and language acquisition. The Modern Language Journal 91(1). 923–939. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00678.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, A. S. 2013. Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203073889.10.4324/9780203073889Suche in Google Scholar

Chung, Y. [정연]. 2018. How to react to Korean’s invitation to a meal. [한국인의 뻔한 거짓말, "언제 밥 한번 먹자!" 들은 미국인 반응]. Retrieved from https://news.sbs.co.kr/news/endPage.do?news_id=N1005064518 (accessed 21 March 2019).Suche in Google Scholar

Cogo, A. & M. Dewey. 2012. Analysing English as a lingua franca: A corpus-driven investigation. London-New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Davies, J. 2006. Hello newbie!** Big welcome hugs** hope u like it here as much as i do!": An exploration of teenagers’ informal online learning. In B. David & W. Rebekah (eds.), Digital generations: Children, young people and new media, 211–228. London-New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Davies, J. 2011. Discourse and computer-mediated communication. In H. Ken & P. Brian (eds.), The Bloomsbury companion to discourse analysis, 228–243. London: Bloomsbury Academic.Suche in Google Scholar

Firth, A. 1996. The discursive accomplishment of normality: On "lingua franca’ English and conversation analysis. Journal of Pragmatics 26(2). 237–259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(96)00014-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Firth, A. & J. Wagner. 2007. Second/foreign language learning as a social accomplishment: Elaborations on a reconceptualized SLA. Modern Language Journal 91. 798–817.10.1111/j.0026-7902.2007.00670.xSuche in Google Scholar

Flanagan, B., C. Yin, T. Suzuki & S. Hirokawa. 2014. Classification of English language learner writing errors using a parallel corpus with SVM. International Journal of Knowledge and Web Intelligence 5(1). 21–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJKWI.2014.065063.Suche in Google Scholar

Foley, M. 2002. Instant messaging reference in an academic library: A case study. College & Research Libraries 63(1). 36–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.63.1.36.Suche in Google Scholar

Geck, C. 2007. The generation Z connection: Teaching information literacy to the newest net generation. In E. Rosenfeld & D. V. Loertscher (eds.), Towards a twenty-first-century school literary media program, 235–241. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press.Suche in Google Scholar

González-Lloret, M. 2013. Conversation analysis of computer-mediated communication. CALICO Journal 28(2). 308–325. http://dx.doi.org/10.11139/cj.28.2.308-325.Suche in Google Scholar

Harasim, L. 2012. Learning theory and online technologies. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.10.4324/9780203846933Suche in Google Scholar

Herring, S. C. 1996. Computer-mediated communication: Linguistic, social, and cross-cultural perspectives. Amsterdam-Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.10.11139/cj.28.2.308-325Suche in Google Scholar

Herring, S. C. & J. Androutsopoulos. 2015. Computer-mediated discourse 2.0. In D. Tannen, H. Hamilton & D. Schiffrin (eds.), Handbook of discourse analysis, 2nd edn, 127–151. Malden, MA: Blackwell. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118584194.10.1002/9781118584194.ch6Suche in Google Scholar

Hiltz, S. R. & M. Turoff. 1978. The networked nation: Human communication via computer. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.10.4324/9780203846933Suche in Google Scholar

House, J. 2003. English as a lingua franca: A threat to multilingualism? Journal of Sociolinguistics 7(4). 556–578.10.1075/pbns.39Suche in Google Scholar

Jenkins, J. 2009. English as a lingua franca: Interpretations and attitudes. World Englishes 28(2). 200–207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2003.00242.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Jewitt, C. 2009. The routledge handbook of multimodal analysis. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Kim, E. Y. A. & L. Brown. 2014. Negotiating pragmatic competence in computer mediated communication: The case of Korean address terms. CALICO Journal 31(3). 264–284. http://dx.doi.org/10.11139/cj.31.3.264-284.Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, G. 2000. Multimodality. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures, 162–202. London and New York: Routledge.10.1111/j.1467-971X.2009.01582.xSuche in Google Scholar

Lee, G. Y. [이가영]. 2018. Why do Koreans invite you for a meal as a conversation closer? [한국인이“밥 한번 먹자”고 인사치레만 하는 이유]. Retrieved from https://news.joins.com/article/22305983 (accessed 21 March 2019).Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Y.-A. 2006. Towards respecification of communicative competence: Condition of L2 instruction or its objective? Applied Linguistics 27. 349–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/aml011.Suche in Google Scholar

Lester, J. N. & M. O’Reilly. 2018. Applied conversation analysis: Social interaction in institutional settings. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.10.4135/9781071802663Suche in Google Scholar

Li, W. 2011. Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics 43. 1222–1235.10.11139/cj.31.3.264-284Suche in Google Scholar

Li, W. 2016. Multi-competence and the translanguaging instinct. In V. Cook & W. Li (eds.), The Cambridge handbook of linguistic multi-competence, 533–543. Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781107425965.026Suche in Google Scholar

Li, W. 2018. Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics 39(1). 9–30.10.1093/applin/amx039Suche in Google Scholar

Martin, E. 2011. Multilingualism and Web advertising: Addressing French-speaking consumers. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 32(3). 265–284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2011.560671.Suche in Google Scholar

McKay, S. L. 2002. Teaching English as an international language: Rethinking goals and perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

McKay, S. L. 2018. English as an International language: What it is and what it means for pedagogy. RELC Journal 49(1). 9–23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0033688217738817.Suche in Google Scholar

Mulyadi, U. & L. Fitriana. 2018. Hashtag (#) as message identity in virtual community. Jurnal The Messenger 10(1). 44–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.26623/themessenger.v10i1.671.Suche in Google Scholar

Murray, D. E. 2000. Protean communication: The language of computer-mediated communication. TESOL Quarterly 34(3). 397–421. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3587737.Suche in Google Scholar

Newfield, D. 2009. Transmodal semiosis in classrooms: case studies from South Africa. Institute of Education, University of London Unpublished PhD thesis.10.1017/CBO9781107425965.026Suche in Google Scholar

Olshtain, E. & A. D. Cohen. 1989. Speech act behavior across languages. In H. Dechert & M. Raupach (eds.), Transfer in language production, 53–67. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.10.1093/applin/amx039Suche in Google Scholar

Paltridge, B. 2012. Discourse analysis: An introduction. London-New Delhi-New York-Sydney: Bloomsbury Publishing.10.5040/9781350934290Suche in Google Scholar

Paolillo, J. C. & A. Zelenkauskaite. 2013. Real-time chat. In S. Herring, D. Stein & T. Virtanen (eds.), Pragmatics of computer-mediated communication, 109–133. Berlín: Mouton de Gruyter. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110214468.10.1080/01434632.2011.560671Suche in Google Scholar

Pennycook, A. 2007. Global Englishes and transcultural flows. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203088807Suche in Google Scholar

Pennycook, A. 2010. Rethinking origins and localizations in global Englishes. In M. Saxena & T. Omoniyi (eds.), Contending with globalization in World Englishes, 196–210. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. http://dx.doi.org/10.21832/9781847692764.10.1177/0033688217738817Suche in Google Scholar

Phillipson, R. 1992. Linguistic imperialism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Phillipson, R. 2009. Linguistic imperialism continued. New York, NY: Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203857175.10.26623/themessenger.v10i1.671Suche in Google Scholar

Pratt, M. L. 1991. Arts of the contact zone. Profession 91. 33–40.10.2307/3587737Suche in Google Scholar

Prensky, M. 2001. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. On the Horizon 9(5). 1–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816.Suche in Google Scholar

Reinhardt, J. 2019. Social media in second and foreign language teaching and learning: Blogs, wikis, and social networking. Language Teaching 52(1). 1–39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261444818000356.Suche in Google Scholar

Saraceni, M. 2015. World Englishes: A critical analysis. London-New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Seidlhofer, B. 2009. Common ground and different realities: world Englishes and English as a lingua franca. World Englishes 28(2). 236–245.10.1111/j.1467-971X.2009.01592.xSuche in Google Scholar

Shachaf, P. 2008. Cultural diversity and information and communication technology impacts on global virtual teams: An exploratory study. Information & Management 45(2). 131–142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2007.12.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Shachaf, P., S. M. Oltmann & S. M. Horowitz. 2008. Service equality in virtual reference. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 59(4). 535–550. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.20757.Suche in Google Scholar

Takahashi, T. & L. M. Beebe. 1987. The development of pragmatic competence by Japanese learners of English. JALT Journal 8(2). 131–155.Suche in Google Scholar

Twenge, J. M. 2017. iGen: Why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy–and completely unprepared for adulthood–and what that means for the rest of us. New York-Londong: Simon and Schuster.10.1515/9783110214468.109Suche in Google Scholar

Wyatt-Smith, C. & K. Kimber. 2009. Working multimodally: Challenges for assessment. English Teaching: Practice and Critique 8(3). 70–80.10.4324/9780203088807Suche in Google Scholar

Yano, Y. 2009. The future of English: beyond the Kachruvian three Concentric Model? In K. Murata & J. Jenkins (eds.), Global Englishes in Asian contexts: Current and future debates, 208–225. Basingstoke: Palgrave. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/9780230239531.10.21832/9781847692764-013Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Training student writers in conducting peer feedback in L2 writing: A meaning-making perspective

- Assessing the use of multiple-choice translation items in English proficiency tests: The case of the national English proficiency test in Turkey

- Translingual negotiation strategies in CMC contexts: English-medium communication in online marketplaces

- Alignment effect in the continuation task of Chinese low-intermediate English learners

- Racializing the problem of and solution to foreign accent in business

- Migrant women, work, and investment in language learning: Two success stories

- Student motivation in Dutch secondary school EFL literature lessons

- Developing 21st century skills for the first language classroom: Investigating the relationship between Chinese primary students’ oral interaction strategy use and their group discussion performance

- How memories of study abroad experience are contextualized in the language classroom

- Spanish L1 EFL learners’ recognition knowledge of English academic vocabulary: The role of cognateness, word frequency and length

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Training student writers in conducting peer feedback in L2 writing: A meaning-making perspective

- Assessing the use of multiple-choice translation items in English proficiency tests: The case of the national English proficiency test in Turkey

- Translingual negotiation strategies in CMC contexts: English-medium communication in online marketplaces

- Alignment effect in the continuation task of Chinese low-intermediate English learners

- Racializing the problem of and solution to foreign accent in business

- Migrant women, work, and investment in language learning: Two success stories

- Student motivation in Dutch secondary school EFL literature lessons

- Developing 21st century skills for the first language classroom: Investigating the relationship between Chinese primary students’ oral interaction strategy use and their group discussion performance

- How memories of study abroad experience are contextualized in the language classroom

- Spanish L1 EFL learners’ recognition knowledge of English academic vocabulary: The role of cognateness, word frequency and length