Abstract

YOS 20, 87 is a scholarly cuneiform tablet from Hellenistic Uruk. The study of its unusual content shows that it is an Akkadian translation of a collection of Greek official documents issued by the Seleucid administration in the first quarter of the third century BC, concerning the rebuilding of the Bīt Rēš, the main sanctuary of Uruk at the time. These works, which had been recognized on the ground by archaeologists a long time ago, remained unattested until now in the textual records. YOS 20, 87 therefore significantly enhances our understanding of the temple’s history and provides a valuable addition to the dossier of Seleucid euergetic policy in Babylonia.

YOS 20, 87 is an Akkadian cuneiform clay tablet from the ancient city of Uruk, in Southern Babylonia. It was originally unearthed by illegal excavators around the beginning of the twentieth century, probably in the sector of the ancient religious complex of the Bīt Rēš, dedicated to the god Anu, which had been the main Urukean sanctuary in the second half of the first millennium BC. The tablet was then acquired from the antiquities market by the John Pierpont Morgan Library,[1] and subsequently housed in the Yale Babylonian Collection, where it remains today.[2] Although the left half of the document is missing, the presence of a colophon on the reverse leaves no doubt about its belonging to the corpus of scholarly documents.[3] No date formula has been preserved, but the occurrence of several dates in the main body of the text indisputably shows that it was composed during the Hellenistic period. Despite its publication as a hand copy in the Yale Oriental Series in 2012,[4] the importance of YOS 20, 87 for the history of Hellenistic Uruk and, more generally, for Seleucid studies has not yet been fully appreciated.[5]

YOS 20, 87 (MLC 2653)

Dimensions : 11.7 × 7.5 × 1.8 cm.

Landscape format. Left half of the tablet missing.[6]

Obverse

1. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-⸢su?⸣ ul-⸢te⸣-mi-da-a- ⸢an?⸣-[a?-šu₂?]

2. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-mešu₃ u₂-de-e ša₂ e₂ dingir-⸢meš⸣ [ša₂ unugki?]

3. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢x⸣ a-na unugki ⸢i⸣-[x x x]

4. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-⸢šu₂?⸣-nu i-pal-lah₃-uʾ a-na ṭe₃-e-⸢mu⸣ [a?-ga?-a?]

5. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢x⸣ u₃ ⸢li⸣-[x x x]

_________________________________________________________________

6. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] Iki-⸢din-d60⸣ u lu₂⸢unug⸣[ki-a-a]

7. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢šu?⸣ unugki [x] ⸢x⸣-mešmah-⸢ru⸣-[u₂ x x x]

8. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢kiuta⸣ at-ta-⸢ar⸣-ru-u₂ nu at-[x x x x]

9. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-⸢x⸣-ʾ la-pa-ni lu₂qi₂-pu-u₂-tu₂ ša₂ e₂.gala-⸢x⸣ [x x x]

10. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x a?-na?I]⸢ki⸣-din-d60 ⸢u₃⸣ lu₂unugki-a-a li-bu-ku-u₂ [x x x x]

11. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-⸢x⸣-ʾ a-na muh-hi ṭe₃-e-mua-ga-[a (x x x)]

12. [(x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x)] ⸢iti⸣sig₄ u₄ 28-kam2mu 22-kam₂ [(x x x x)]

_________________________________________________________________

13. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-⸢gu?-ra⸣-aʾ šu-⸢lum⸣ il-ta-pa-arlugalI⸢at⸣-[ti-ʾu-ku-su]

14. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x il/al]-⸢ta⸣-pa-ar a-na Ia-ga-na-ti-i-su u₃ [Ix x x x]

15. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x i?]-⸢de⸣-e-ku-uʾ ša₂ ina nap-har ne₂-pi-iš gab-bi ⸢x⸣ [x x x x]

16. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢ša₂?⸣ nin-da-ba-ne₂-e u₃ u₄ eš₃.eš₃-mešlib₃-bu-u₂ [x x x x x]

17. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-⸢x⸣-u₂ ṣa-lam-mešša₂ dingir-meša-naunugkiib-ba-ak-⸢uʾ⸣ [x x x x]

18. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢x x x⸣ gi-nu-u₂ ⸢it⸣-ti-ir la u2-⸢qa?⸣-[ar?-ra?-bu?]

19. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-⸢ʾ⸣ at-tu-un ⸢lib₃?⸣-[bu?]-⸢u₂?⸣ ša₂ ṭe₃-⸢e⸣-[mu a?-ga?-a?]

20. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-⸢x⸣-di ša₂ ⸢dingir⸣-meš ⸢a⸣-na unugkii-te-⸢er⸣(-)[x x x x]

21. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢x it?⸣-ti-ir la i-qar-ru-bu(-)[x x x x]

22. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢šu₂?-u₂⸣ mah-ru-u₂ lu-u₂ ka-⸢x⸣ [x x x x]

_________________________________________________________________

23. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢lu₂⸣ṭup-šar-ri diš u₄ d60 den.lil₂.la₂ ša₂ [x x x x]

24. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] šar-ratfa-pa-am a-na Iip-pu-[x x x x]

25. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-bi ana e-peš u₃ ik-ta-⸢šid(-)x⸣ [x x x x]

26. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢e⸣-peš lib₃-bu-u₂ ša₂ lugal ⸢x⸣-[x x x x x x]

Reverse

27. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-⸢x⸣-ku-nu-šu₂ lib₃-bu-u₂-šu₂ ep₂-ša₂-aʾmu 28-⸢kam₂⸣ [u₄ x-kam₂ (ša₂) itix]

_________________________________________________________________

28. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] a-gan-nu iq-ṭa-bu-u₂ ina pa-ni-ia e₂ re-eš [x x x x]

29. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢e₂⸣ dingir-mešša₂ unugkiin-ne₂-ep-pu-uš u₃ ⸢ul⸣ [x x x x]

{blank space of two lines}

_________________________________________________________________

30. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢a-na⸣ muh-hi Iki-din-d60 : : : a-⸢x⸣ [x x x]

_________________________________________________________________

31. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x d?]⸢60?⸣ lu₂ṭup-šar-ridiš u₄ d60 den.⸢lil₂.la₂ x⸣ [x x x x]

32. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x e₂] ⸢re⸣-eš e₂ dingir-mešša₂ unug⸢ki⸣ a-na ⸢x⸣ [x x x]

33. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x ṭe₃]-⸢e⸣-mu iš-kun-uʾ ša₂ e₂ re-eše₂ dingir-meš [ša₂ unugki]

34. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x a-na] ⸢muh-hi⸣ e-peš ša₂ e₂re-eš ka-lu-⸢u₂⸣ [x x x]

35. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x xe₂?] ⸢dingir?⸣-mešaʾin-ne₂-ep-pu-uš [x x x x]

36. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ṭe₃-e-muša₂-ki-in [(x x x)]

_________________________________________________________________

37. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x]-⸢u₂⸣-a ṭe₃-e-mu iš-kun ba-nu-u₂ ša₂ ⸢e₂⸣ [re-eš?]

38. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢ka⸣-lu-u₂ li-im-ma-na-a-šu₂ ul-tu ša₂ [x x x x]

39. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ⸢x⸣ sa dumu 37-kam₂ u₄ 10-kam₂ ša₂ itiganṭe₃-e-⸢mu⸣ [ša₂-ki-in?]

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

40. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x] ša₂ Iki-din-d60 lu₂maš.mašd60 u an-tu₄ [(x x x x)]

41. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x Ise-lu]-⸢ku⸣ u Iat-ti-ʾu-ku-sulugal-mešiš-⸢ṭur⸣-[u₂?]

{blank space of one line}

42. [imIPN dumuša₂ IPN lu₂maš.maš?d60 u an]-tu₄ lu₂umbisag diš u₄ d60 den.lil₂.la₂ {erasure}

43. [qat₃ IPN dumuša₂ IPN aId]⸢30⸣-ti-er₂ a-na a-ha-zi-šu₂gid₂.da u₄-meš-šu₂ din zi[ti₃-šu₂]

44. [kun-nu suhuš-meš-šu₂ la gal₂egig-šu₂ u mud enu₂-ti-šu₂] sar-ma u₂-kin mudd60 u an-tu₄ li-iṣ-ṣur-šu₂ li‑[ša₂-qi₂-ir]

45. [x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x la] ⸢tum₃⸣-šu₂ ina me-reš-<ti>-šu₂ la u₂-šam-kuš-šu₂ ina iti-šu₂ a-⸢na⸣ [maš-tak-ku]

46. [en-šu₂ he₂.gur-šu₂ (x x x x x x x x x x x)] (erasure)

Comments

1: ul-⸢te⸣-mi-da-a-⸢an?⸣-[a?-šu₂?]: lamādu D perfect 3cs, with a 1cp dative pronoun (cf. CAD L: 57–58, s.v. lamādu 7a). The same form can be found in CT 49, 144 (Babylon, ca. 118 BC), l. 13, ul-te-mi-i-da-na-a-šu₂ “he informed us that”. Cf. Hackl (in press).[7]

2: e₂ dingir-⸢meš?⸣ [ša₂ unug ki?]: Restitution based on the parallels with ll. 29 and 32.

4 and 19: ṭe₃-e-mu [a?-ga?-a?]: Hypothetical restitution based on the parallel with l. 11.

8: at-ta-⸢ar⸣-ru-u₂: arû Gtn preterite 1cs, with a subordination marker -u (cf. CAD A/2: 314, s.v. arû 2a). We understand it as a quote from the Seleucid king.

9: lu₂qi₂-pu-u₂-tu₂ ša₂ e₂.gal: Contrarily to our previous assumption (Clancier/Monerie 2014: 191), qīpūtu must not be understood as an abstract noun, but as the plural of qīpu (cf. CAD Q: 264). To our knowledge, the office of qīpu ša ēkalli (or its Greek equivalent) is otherwise unattested.

10: li-bu-ku-u₂: abāku G precative 3 mp (CAD A/1: 6, s.v. abāku 3b2′). The same verb is found again on l. 17 about divine statues, as well as in the Uruk Prophecy, a Late Achaemenid or Early Hellenistic text from Uruk, again in connection with the transfer of divine statues (SpTU 1, 03 r. 4 and 13, cf. infra n. 72).

12: Official correspondence recorded in Greek epigraphy often ends with a line break, followed by a dating formula aligned to the right of the stele. See, e.g., the so-called Heliodorus stele from Maresha, in Idumea (cf. Cotton-Paltiel et al. 2017). There is a possibility that the scribe followed the same model here, in which case the beginning of the line may have been a vacat.

13: [...]-⸢gu?-ra⸣-aʾ šu-⸢lum⸣: This sequence could be part of a Greek personal name, possibly with an ending in ‑γόρας. Cf. Ipi-la-a-gu-ra-a used in reference to the Cypriot king Philagoras in Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions (e.g., RINAP 4, 01 v. 64). If this assumption is correct, this individual could be the recipient of document C. The fact that it is followed by šu-lum (for šulmu, “greetings”), which we understand as a translation of χαίρειν, i.e., the standard formula found at the beginning of Greek official letters, lends weight to this hypothesis. The form šu-lum (instead of šul-mu) occurring in YOS 20, 87 is attested in Neo-Assyrian letters (cf., e.g., SAA 10, 166, l. 3; SAA 13, 176, l. 3; SAA 17, 101, l. 2).

14: Ia-ga-na-ti-i-su u₃ [Ix x x x]: The most likely identification for this clearly Greek anthroponym is Ἁγνόθεος, as proposed by Doty/Wallenfels (2012: 42). The following break after the conjunction u probably contained another personal name. Both appear to have been the joint recipients of an official letter.

15: [i?]-⸢de⸣-e-ku-uʾ: dekû G durative 3mp. It is difficult, in the present state of the document, to determine if this verb concludes a sentence which is lost in the preceding break or if it must be interpreted as part of what follows. We therefore limit ourselves, with all due caution, to rendering the verb’s primary meaning (“to remove”, cf. CAD D: 124 s.v. dekû 1).

16: nin-da-ba-ne₂-e u₃ u₄ eš₃.eš₃-meš: To our knowledge, the plural form nindabānê instead of the expected nindabû or nindabê is otherwise unattested. There is no doubt, however, that it refers to food offerings (cf. Linssen 2004: 164), in connection with eššēšu-days (Linssen 2004: 45–51), as well as with regular offerings (ginû, cf. Linssen 2004: 162–163), which appear in l. 18.

18: ⸢it⸣-ti-ir la u ₂ -⸢qa?⸣-[ar?-ra?-bu?]: This hypothetical restoration of qerēbu D durative 3mp is based on the parallel of l. 21, which belongs to the same section, where this verb is found (though in a G durative form with a passive meaning, cf. CAD Q: 234 s.v. qerēbu 4) in connection with the same negative adverb lā and the same verbal hendiadys with ittir (watāru G durative 3cs).

24: Iip-pu-[x x x x]: This Greek personal name is clearly formed on the anthroponymic component Ἱππο-, but the following break prevents us from determining the exact name of this individual.

25: ana e-peš: Given the general content of the document, we understand epēšu in the sense of “to build” (CAD E: 197–199, s.v. epēšu 2b3′). Cf. Antiochus Cylinder i. 6–7: inūma ana epēš Esaggil u Ezida libbī ublamma, “When I decided to (re)build Esagil and Ezida.”

27: lib₃-bu-u₂-šu₂ ep ₂ -ša ₂ -aʾ: For libbūšu, see CAD L: 173, s.v. libbu 4a2′c′. Concerning ep₂-ša₂-aʾ (epēšu G imperative 2cp), the collation of the line does not support the reading egirʾa proposed on the HBTIN website.

28: iq-ṭa-bu-u₂: On the phonetic alteration of the -t- into an emphatic -ṭ- after -q-, which is attested in other sources from the Hellenistic period, see Jursa/Debourse (2017: 84).

30: The fact that this section (VI) only occupies a single line, combined with the presence of three successive separation marks in the form of two superimposed oblique signs, suggests that this section is a scribal heading rather than another official document. The exact meaning of this disjunction between the last two documents and the rest of the compendium remains difficult to grasp.

33: iš-kun-uʾ: The verbal form as it stands should be interpreted as a preterite 3mp, the use of an aleph being a common way to indicate the long final vowel of the plural form. However, we cannot exclude the hypothesis that the verb could be a preterite 3cs with an unusual form of the subordination marker -u-, rendered here with an aleph (cf. OECT 9, 12, l. 12, lu₂na-din-uʾ, where the aleph is used to render a short vowel).

34 and 38: e₂ re-eš ka-lu-⸢u₂⸣: The use of kalû instead of the expected kalûšu is consistent with the use of πᾶς after the substantive in Greek, which does not require an anaphoric pronoun (cf. Liddell/Scott: 1345, s.v. πᾶς B).[8]

36 and 39: ṭe₃-e-mu ša₂-ki-in: This sentence appearing in both cases at the very end of the section, after the date (at least in the case of section VIII), which usually concludes Hellenistic official documents, seems to find no clear parallel in Greek epigraphy. It could be an addition by the cuneiform scribe, stating that the order has been duly carried out. Note that the sentence occurs only in sections VII and VIII, both of which are apparently separated from the preceding documents by a scribal heading (section VI).

38: li-im-ma-na-a-šu₂: This verbal form can be understood either as limmannāšu (manû N precative 3cs with ventive and 3ms pronominal suffix) or as limmannâšu (manû N precative 3fp with 3ms pronominal suffix). We understand manû N in the sense of “to be assigned, delivered” (Cf. CAD M1: 227, s.v. manû 12c).

39: ...] ⸢x⸣ sa du: This sequence could be the end of a personal name. The line, however, is far too damaged to allow any certainty.

40–46: Our reconstruction and translation of this section follow M. Ossendrijver’s study of the tablet’s colophon (2020: 315–316).

Translation

(Section I)

1[...............................................................]os? informed [us (that)]

2[......................................................... the ......]s and paraphernalia of the sanctuary [of Uruk?]

3[...............................................................] ... to Uruk, ...[.........]

4[......................................................] their [......] they will obey [this?] order

5[...............................................................] ... and may [.........]

______________________________________________________

(Section II)

6[...................................................................] Kidin-Anu and the Uruk[eans]

7[..................................................................] ... Uruk, the [...]...s were receiv[ed .........]

8[............................................................] ... and since I rule, I have not [............]

9[.........................................................] ...... from the palace administrators ...... [.........]

10[............................................. to?] Kidin-Anu and the Urukeans, may they transfer [............]

11[......................................................] ...... concerning this order [.........]

12[(......................................................)] Month simānu, the 28th, year 22 (SEB)[(............)].

______________________________________________________

(Section III)

13[...................................................]goras?, greetings. King An[tiochos] has written

14[................................................ he has / I have] written to Hagnotheos and [PN]

15[...................................................] they will remove?. Concerning? all the ritual procedures ... [............]

16[................................................] of? the food offerings and the eššēšu-festivals, in accordance with? [...............]

17[................................................]... they will transfer the statues of the gods to Uruk [............]

18[................................................] ......... regular offerings in excess, they shall not pr[esent?]

19[............................................................] ..., you(pl.), in accordance with [this?] ord[er]

20[............................................................] ...... of the gods will retu[rn] to Uruk [.........]

21[..................................................................] in excess, they shall not be offered [............]

22[...............................................................] ...... will be received?. May ...... [............].

______________________________________________________

(Section IV)

23[................................................ Kidin-Anu?], scribe of Enūma Anu Enlil, of/who [............]

24[...............................................................] queen Apama to Hippo[............]

25[...............................................................] ... for the building works and he/they completed [...............]

26[............................................................] building works, in accordance with what the king ... [..................]

27[................................................] ... to/for you(pl.), act(pl.) accordingly! Year 28 (SEB), [the xth (of) month ...].

______________________________________________________

(Section V)

28[................................................] this, they declared in my presence. The Bīt Rēš [............]

29[.............................................] the sanctuary of Uruk is being (re)built and is not [............].

{blank space of two lines}

______________________________________________________

(Section VI)

30[...................................................] concerning Kidin-Anu : : : ...... [.........].

______________________________________________________

(Section VII)

31[............................................. Kidin]-Anu?, scribe of Enūma Anu Enlil, ... [............]

32[................................................... Bīt] Rēš, the sanctuary of Uruk, to ... [.........]

33[...................................................] they? issued an [or]der (stating) that the Bīt Rēš, the sanctuary [of Uruk,]

34[................................................... con]cerning the whole (re)building of the Bīt Rēš [.........]

35[......................................................] this [sanc]tuary? is being (re)built [............]

36[.........................................................] The order has been issued. [(.........)]

______________________________________________________

(Section VIII)

37[.........................................................]...... he issued an order, the (re)building of the Bīt [Rēš]

38[.......................................] Let the whole [(re)building? of] the [Bīt Rēš?] be assigned to him, from [......]

39[.........................................................]......... Year 37 (SEB), the 10th of month kislīmu. The order [has been issued?].

______________________________________________________

(Section IX)

40[......................................................] that/of Kidin-Anu, exorcist of Anu and Antu, [(............)]

41[.......................................... Seleu]cus and Antiochus, the kings, wrote.

{blank space of one line}

42[Tablet of PN son of PN, exorcist (or “lamentation priest”) of Anu and An]tu, scribe of Enūma Anu Enlil.

43[Hand of PN, son of PN, descendant of] Sîn-lēqe-unnīnī. For his learning, lengthening his days, sustaining his li[fe],

44[establishing his position, the absence of illness and revering his lordship,] he wrote it and placed it. He who reveres Anu and Antu shall take care of it and ap[preciate it].

45[.............................................] shall [not] carry it off, shall not intentionally make it disappear (and) in the same month, to [the living quarters]

46[of its owner, shall return it. (.................................)].

Date of the Document

As mentioned above, no date formula has been preserved in the colophon.[9] The latest date mentioned in the document (10thkislīmu 37 SEB, i.e., 25th December 275 BC, l. 39), provides a terminus post quem to its production, which obviously predated the destruction of the Bīt Rēš temple complex, around 100 BC.[10] This general time frame, however, is too large to be useful, and a closer examination of the document’s content allows us to refine this rough dating.

Firstly, M. Ossendrijver recently pointed out that the colophon of YOS 20, 87 contains an unusual formula (ll. 43–44, ana ahāzišu ... išṭur-ma ukīn, “for his learning, he wrote (it) and placed (it)”), which only appears in six other Urukean scholarly tablets, dated between 251 and 194 BC.[11]

Secondly, although the names of the document’s owner and scribe have not been fully preserved,[12] we know that the scribe belonged to the Sîn-lēqe-unnīnī clan, and that the owner was both a scribe of Enūma Anu Enlil and either an exorcist (mašmaššu) or lamentation-priest (kalû) of Anu and Antu (l. 42). Such a combination of titles is actually quite rare in Hellenistic Uruk, as it is currently attested for only four individuals[13] within a period of time spanning from 251 to 182 BC.[14] Interestingly, all these scholars were involved in some way in the production of the tablets bearing the aforementioned formula in their colophon,[15] which tends to confirm the dating of our tablet either to the second half of the third century BC or to the beginning of the following century.

Among these four scholars, however, only two are attested as owners of tablets written by scribes of the Sîn-lēqe-unnīnī clan, as is the case for our document: one is Šamaš-ēṭir / Ina-qibīt-Anu / Šibqat-Anu // Ekur-zākir, who was active in Uruk in the early second century BC and whose association with the lamentation priest Anu-ab-utēr / Anu-bēlšunu / Nidintu-Anu // Sîn-lēqe-unnīnī in the 190s BC is well-attested;[16] the other is Anu-ab-utēr himself, who worked with his nephew Anu-balāssu-iqbi, son of Nidintu-Anu, between 182 and 176 BC.[17] We will see that, among these two scholars, the former is the most likely to have been the owner of our text.

All of this allows us to date YOS 20, 87 with a reasonable degree of confidence to the turn of the third and second centuries BC. That is not to say, however, that the content of the text was composed during this period. The occurrence of a distinct feature in YOS 20, 87, namely the peculiar transcription of the name of Antiochus as Iat‑ti-ʾu-ku-su (ll. 13 and 41), actually advocates the contrary, since the assimilation of the nasal ‑n‑ to the dental ‑t‑, which frequently appears in Urukean sources under the reign of Antiochus I (294–261 BC), quickly fell into disuse after his death to disappear completely after 251 BC.[18] Consequently, if our proposed dating of YOS 20, 87 to the late third or early second century BC is accepted, we must conclude that its scribe either compiled earlier documents, or simply copied an older compilation.[19] The fact that the antiquated spelling Iat-ti-ʾu-ku-su occurs in what seems to be the document’s title (ll. 40–41) tends to support the second hypothesis, i.e., that YOS20, 87 was simply copied from an earlier manuscript, although the idea that the text could be an original compilation cannot be entirely ruled out.[20] Be it as it may, the (now lost) source material of our tablet can be tentatively dated to the first half of the third century BC, when the aforementioned phonetic assimilation in the transcriptions of Antiochus’ name was used by Urukean scribes.

Nature of the Document

As can be seen from the translation above, YOS 20, 87 is divided into nine sections, all clearly singled out by dividing lines on the tablet and apparently arranged in chronological order (cf. Fig. 2). Such an arrangement suggests that the author – be it the scribe of YOS 20, 87 or the scholar who produced the original manuscript from which our tablet was copied – drew on earlier sources to compose his text. The presence of various strange linguistic features, which can sometimes obscure the meaning of the document, also gives the impression that the Urukean scholar who composed the original manuscript did not work from a blank page: first, the basic Akkadian syntax requiring that the verb always appears at the end of the sentence does not seem to have been consistently applied, which is surprising for the work of a Sumero-Akkadian scholar.[21] Likewise, the royal title, which always appears after the king’s name in Akkadian cuneiform texts, precedes the name in the main body of our document.[22] Finally, two of the three dates preserved in the document are expressed by stating the year before the month and the day, while cuneiform scribes normally expressed dates in a month/day/year order.[23]

Such a combination of oddities, which are all very unusual in an Akkadian context, finds a fitting explanation if we assume that they were the result of a translation from Greek to Akkadian,[24] as: a) stating the year before the month and the day, which is almost never attested in Hellenistic cuneiform sources,[25] was the common way to express a date in Greek documents;[26] b) the unusual expressions šarru Attiʾukusu (l. 13) and šarrat Apam (l. 24) find exact parallels in the Greek titles basileus Antiochos and *basilissa Apamè;[27] and c) the peculiar Akkadian syntax can be accounted for by the fact that it derives from original(s) in Greek, which does not necessarily require the verb to be at the end of the sentence.[28]

Interpreting YOS 20, 87 as a collection of Greek documents translated to Akkadian also sheds light on other parts of the text (cf. Fig. 1).

Akkadian formulae in YOS 20, 87 and Greek parallels in Seleucid official correspondence.

| Akkadian formulae in YOS 20, 87 | Parallels in Seleucid official correspondence |

| ipallahū ana ṭēmu [agâ? (...)] u li[...] (“they will obey [this?] order [(...)] and may [...]”), ll. 4–5 | καλῶς ἂν οὖν ποιήσαις συντάξας ἐπακολουθήσαντας τοῖς ἐπισταλεῖσιν συντελεῖν ὥσπερ οἴεται δεῖν (“You would do well, therefore, by giving orders for your subordinates to obey the orders and carry out things as he thinks fit”), SEG 37, 1010 (= Ma 1999 No. 4), ll. 13–16. |

| šulmu (“greetings”), l. 13 | χαίρειν (“greetings”), passim. Cf., e.g., SEG 39, 1284 (= Ma 1999 No. 2), l. 8. |

| libbū ša ṭēmu [agâ?] (“in accordance with [this?] order”), l. 19 | κατὰ τὸ παρὰ Νικομάχου τοῦ οἰκονόμου πρόσταγμα (“in accordance with the order of Nikomachos the oikonomos”), OGIS 225, l. 38 (= RC 20, l. 6). |

| libbū ša šarru [...] (“according to what the king [...]”), l. 26 | καθάπερ ὁ βασιλεὺς γέγραφεν (“according to what the king wrote”) SEG 16, 710 (= RC 19), l. 16. |

| libbūšu epšā (“actpl. accordingly”), l. 27 | συντελείσθω πάντα τοῖς προγεγραμμένοις ἀκολούθως (“let everything be done in accordance to the instructions written above”), OGIS 224 (= Ma 1999 No. 37), ll. 32–33. |

Judging from the above, YOS 20, 87 can be best described as a compendium of seven official documents, which were translated from Greek to Akkadian in the first half of the third century BC and compiled in a single text. These documents will hereafter be referred to as documents A to G (cf. Fig. 2).

Content of the sections of YOS 20, 87.

| Section | Type | Content | Corresponding date |

|

Section I

(ll. 1–5) |

Document A: official document, possibly a covering letter between Seleucid officials. | Fragmentary: cultic paraphernalia are mentioned, possibly in the context of their return to Uruk. | No date (ca. 290 BC?) |

|

Section II

(ll. 6–12) |

Document B: letter from the king (Antiochus I?) sent to a Seleucid official (who might be the author of document A).[29] | The document mentions Kidin-Anu and the Urukeans, a reception of undetermined nature and a transfer order. Palace administrators are mentioned. | 6th July 290 BC |

| Section III (ll. 13–22) | Document C: letter between Seleucid officials (the addressee is presumed to be [...]goras?). | The document apparently follows a royal letter from Antiochus I (which could be document B). Mention of a letter to two Seleucid officials (one of whom is named Hagnotheos). The document itself concerns ritual offerings and the return of cult statues to Uruk. | No date (ca. 290–284 BC) |

|

Section IV

(ll. 23–27) |

Document D: letter or covering letter sent by a Seleucid official to a scribe of Enūma Anu Enlil (probably Kidin-Anu). | The document mentions building works (most likely on the Bīt Rēš). It follows an interaction (letter?) between queen Apama and a certain Hippo[...], as well as an order from the king (which could be document E). | 284/83 BC |

|

Section V

(ll. 28–29) |

Document E: official document (possibly from the king or from queen Apama). | Ongoing building works on the Bīt Rēš are mentioned. | No date (ca. 284–275 BC) |

|

Section VI

(l. 30) |

Scribal heading for the following sections? | “[...] concerning Kidin-Anu” | |

|

Section VII

(ll. 31–36) |

Document F: official letter sent to a scribe of Enūma Anu Enlil (probably Kidin-Anu). | Ongoing building works on the Bīt Rēš are mentioned, as well as an official order. The section ends with the (scribal?) indication that the order has been issued. | No date (ca. 284–275 BC) |

|

Section VIII

(ll. 37–39) |

Document G: letter, probably sent to a Seleucid official. | The document mentions an order, building works on the Bīt Rēš and an assignment. The section ends with the (scribal?) indication that the order has been issued. | 25th December 275 BC |

|

Section IX

(ll. 40–46) |

Compendium title (ll. 40–41) and colophon (ll. 42–46). | No date preserved |

Since the precise nature of these documents and the identity of their authors and addressees often elude us, it remains difficult to assess whether they should be combined in sets or read independently. It would be tempting, for instance, to interpret document A as the covering letter of document B, and document C, which begins with a reference to a previous letter from Antiochus I (l. 13), as part of the same set. Similarly, document D, which also seems to refer to a royal order of some sort (ll. 26–27), might have been linked to the seemingly laconic document E. Caution, however, must be exerted due to the fragmentary state of the tablet.

Despite these uncertainties, we know from the title of the tablet (“[...] that/of Kidin-Anu, exorcist of Anu and Antu, [...] Seleucus and Antiochus, the kings, wrote.”, ll. 40–41) that at least some of these documents were prostagmata, i.e., official orders issued in the form of letters.[30] As a matter of fact, the Akkadian word ṭēmu (“command, order, instructions”), which appears six times in our document,[31] could be a translation of the Greek prostagma (“ordinance, command”). Cuneiform sources from Northern Babylonia such as the astronomical diaries and the chronicles regularly mention the reception of leather documents (kuššipištu) sent to local authorities by the royal chancery, but their content is rarely reproduced verbatim, and never quoted extensively.[32] In the case of YOS 20, 87, the letters received from the Seleucid administration were fully translated from Greek to Akkadian and compiled in a single document.

The question of the nature of the medium on which the original manuscript of this compendium was inscribed remains open. One would naturally think of a clay tablet, a writing board or a leather document, but the hypothesis that this editio princeps could have been inscribed on a (bilingual?) stone stele cannot be entirely ruled out, as it was customary for local communities of the Seleucid empire to have official correspondence engraved on stelae ‒ sometimes at the request of the Crown ‒ and to put them on display in their main sanctuaries.[33] Several examples of clay tablet bearing texts copied from such stelae are attested in Hellenistic Babylonia,[34] the most interesting case for our study being the so-called Lehmann text, which is currently known by two manuscripts on clay tablets (CTMMA 4, 148 A and B): it was copied from a (now lost) stone stele erected in 236 BC in the small courtyard of the Esagil, the main sanctuary of Babylon, and contains a speech by the temple administrator (šatammu) followed by a decision of the local assembly.[35]

Seleucid Administration in Babylonia

Despite the comparative wealth of the Babylonian documentation, surprisingly little is known of the satrapy’s administration during the first decades of the Seleucid era. The additional evidence found in YOS 20, 87 provides valuable insight into these matters. First of all, at least five officials appear in the document:[36] [...]os? (l. 1), who seems to have been a collaborator of document A’s author; [...]goras? (l. 13), to whom document C was addressed; Hagnotheos (l. 14), who appears with an individual whose name is lost in a break as co‑addressee of an official letter around 290–284 BC; and Hippo[...], who is mentioned in document D in connection with the queen (l. 24). Although the exact positions held by these individuals remain undetermined,[37] it is not unreasonable to assume that most of them were Seleucid officials operating at various levels of the satrapal administration. These individuals acted as intermediaries in the transmission of the royal orders and maybe, in some cases, as issuers of official prostagmata.[38]

Another interesting feature of YOS 20, 87 is the hitherto unattested reference to “palace administrators” (qīpūtu ša ēkalli, l. 9) found in document B (290 BC), although the Greek title behind this Akkadian periphrasis is difficult to identify. The office of qīpu is well-attested in the Neo-Babylonian and Early Achaemenid sources, where it refers to the so-called “royal resident”, a member of the temple’s high administration in charge of the sanctuary’s obligations towards the Crown,[39] but there is little chance that this office was intended here: firstly, because the Hellenistic counterpart of the sixth century BC qīpu is attested in the cuneiform sources as paqdu in Akkadian or episkopos in Greek;[40] secondly, because the title of qīpūtu ša ēkalli does not suggest that they were temple officials.

A more promising lead would be to understand them as officials of the local basilikon, the royal institution in charge of managing the Crown’s resources, which played a major part in the local implementation of royal euergetic actions.[41] This idea would fit the ‒ admittedly fragmentary ‒ context of their occurrence, since the document mentions something being apparently transferred “from the palace administrators” (lapāni qīpūtu ša ēkalli) in the context of the temple’s building works (l. 9). However, the fact that the basilikon is consistently rendered as bīt šarri in the cuneiform sources contradicts this hypothesis, as the cuneiform scribes usually made a clear distinction between the basilikon (bīt šarri) and the royal palace (ēkallu).

As a result, the most reasonable assumption is probably that these qīpūtu ša ēkalli were officials in charge of the management of a royal palace. Interestingly, a rab ēkalli (lit. “palace manager”) is also mentioned in a debt note from Babylon datable to ca. 261–257 BC (Hackl 2013, No. 124 = BM 41919, l. 3), but the potential relationship between these two offices cannot be determined in the present state of the documentation. Likewise, the identification of the palace where these qīpūtu ša ēkalli operated, be it the old palatial complex of Babylon, the newly built palace of Seleucia-on-the-Tigris, some secondary royal residence near Uruk, or another palace outside Babylonia (in Susa?), remains out of reach.

Kidin-Anu and the Urukeans

Let us now turn to the local authorities of Uruk. Similarly to the Seleucid letters addressed to the temple administrator (šatammu) of the Esagil and/or the “Babylonians” (i.e., the temple assembly representing the city) recorded in the astronomical diaries and chronicles from the third century BC,[42] the final recipients and/or main beneficiaries of the documents translated in YOS 20, 87 seem to have been a certain Kidin-Anu, along with the Urukean temple assembly. This can be deduced from the fact that “Kidin-Anu and the Urukeans” are mentioned twice in document B (ll. 6 and 10), that Kidin-Anu appears alone in the title of the compendium (“[...] that Kidin-Anu, exorcist of Anu and Antu, [...] Seleucus and Antiochus, the kings, wrote.”, ll. 40‒41) as well as in section VI, which seems to have been a subtitle of some sort (“[...] concerning Kidin-Anu [...]”, l. 30), and probably again in the first lines of documents D (l. 23) and F (l. 31), where the addressee’s name is expected. Taken together, these elements suggest that this Kidin-Anu was the head of the Urukean community in the first quarter of the third century BC, just like the šatammu of Esagil was the head of the Babylonians.

Although Kidin-Anu was a common personal name in Uruk at the time, the identity of this individual is quite clear: he is most certainly Kidin-Anu, son of Anu-ah-ušabši, descendant of Ekur-zākir, an important Urukean figure of the Early Hellenistic period, whose career is well-documented by the local sources (Fig. 3).[43]

Attestations of Kidin-Anu / Anu-ah-ušabši // Ekur-zākir in the cuneiform sources from Uruk.

| Document | Document Type | Role {and official titles} (w/ lines) | Date |

| OECT 9, 01 | Quitclaim for arable land | Witness (r. 8′) | ca. 315–311 BC |

| TCL 13, 234 | Sale of arable land | Witness (r. 13) | 312 BC |

| VS 15, 51 | Sale of real estate | Witness (r. 9) | ca. 305–294 BC |

| VDI 1955/4, 06 | Sale of prebend share | Witness (r. 4)[44] | 300 BC |

| TCL 6, 38 | Ritual prescriptions for daily offerings | Copyist of ritual texts {Urukean, exorcist of Anu and Antu, high priest of the Bīt Rēš} (r. 47–48) | ca. 294–281 BC |

| YOS 20, 87 | Compendium of official documents | Addressee of royal letters {exorcist of Anu and Antu, and possibly scribe of Enūma Anu Enlil} | ca. 290–275 BC |

| BRM 2, 04 | Sale of prebend share | (First) witness (r. 1) | 283 BC |

| YOS 20, 17 // Corò 2018 No. 09 |

Sale of prebend share | (Co-)owner of an ērib bīti prebend before Anu, Antu and other gods (o. 5‒6) | 276 BC |

| BRM 2, 10 | Sale of slave | (First) witness (r. 5) | 275 BC |

| YOS 20, 20 | Donatio mortis causa | (First) witness (r. 5) | 270 BC |

Kidin-Anu, son of Anu-ahu-ušabši, was probably born around the middle of the fourth century BC, at the end of the Achaemenid period. He was a member of one of the most prominent priestly families of Uruk, the Ekur-zākir clan, which was known to produce expert exorcists (mašmaššu or āšipu).[45] The earliest attestations of his activities, during the Diadochi period (ca. 315–300 BC), document him as a simple witness for legal transactions. However, Kidin-Anu seems to have gained prominence at the turn of the third century BC, when the sources describe him as an Urukean (i.e., a member of the assembly of Uruk), as an exorcist of Anu and Antu, and as an ērib bīti (lit. “temple enterer”) of the cella of Anu and Antu, the most prestigious categories of priests in the Bīt Rēš.[46] He may also have been an expert in celestial matters, if the title of “scribe of Enūma Anu Enlil” at the beginning of documents D (l. 23) and F (l. 31), which seems to state the addressee’s profession, can be interpreted as relating to Kidin-Anu.[47]

More importantly, Kidin-Anu also acted as “Elder Brother” (ahu rabû) of the Bīt Rēš, the temple’s most prominent sacerdotal position at the time, which probably explains why he was both the head of the city’s assembly and the main local interlocutor of the Seleucid administration, just like the high administrator (šatammu) of the Esagil temple in Babylon.[48] This prominence is indirectly confirmed by the fact that Kidin-Anu consistently appears as first witness, a position of honour, in the legal deeds mentioning him between 283 and 270 BC (cf. Fig. 3).[49] Since YOS 20, 87 (l. 6) already mentions him as a prominent figure in 290 BC, it can be inferred that Kidin-Anu held this office of ahu rabû between the 290s BC and ca. 270 BC, after which he disappears from the sources.[50]

Kidin-Anu, however, is chiefly known for his appearance in the colophon of TCL 6, 38, the only document mentioning explicitly his title of ahu rabû. This text is a composite set of instructions for the preparation of the ritual meals presented to the divine statues in the Bīt Rēš. Although the tablet itself was probably inscribed in the early second century BC, its famous colophon states that it was originally copied by Kidin-Anu, three generations earlier:[51]

Hand of Šamaš-ēṭir, son of Ina-qibīt-Anu, son of Šibqat-Anu. Writing board of the cultic ordinances of Anu (paraṣ anūtu), of the holy purification rites (and) the ritual regulations of kingship, together with the purification rites of the gods of the Bīt Rēš, the Irigal, the Eanna and the (other) temples of Uruk, the ritual activities of the exorcists, the lamentation priests, the singers and all the experts, (so) that, later on, everything which the apprentice holds will be available to an expert. (Written) in accordance with the tablets that Nabû-apla-uṣur, king of the Sealand, carried off from Uruk and then, Kidin-Anu, Urukean, exorcist of Anu and Antu, descendant of Ekur-zākir, Elder Brother (ahu rabû) of the Bīt Rēš, saw those tablets in Elam, copied them in the reign of kings Seleucus (I) and Antiochus (I) and brought them to Uruk.[52]

Several aspects of this text require clarification. First, we have seen that the scribe of TCL 6, 38, Šamaš‑ēṭir / Ina‑qibīt‑Anu / Šibqat-Anu // Ekur-zākir, was a strong candidate for being the owner of YOS 20, 87. The fact that both texts allude to a refoundation of the Bīt Rēš’s cultic activities under Seleucus I and Antiochus I on the one hand, and that Kidin-Anu is central to the history of both documents on the other, lends weight to this hypothesis.[53] If this assumption is correct, the scribe of YOS 20, 87 would then most likely be Anu-ab-utēr / Anu-bēlšunu / Nidintu-Anu // Sin-lēqe-unnīnī, and the tablet could be dated more securely to the first decade of the second century BC, when these two scholars are known to have worked together.[54]

Secondly, many commentators have stressed that the contents of the colophon could not be taken at face value, since the Bīt Rēš and Irigal did not exist as such under Nabu-apla-uṣur (i.e., Nabopolassar, 626–605 BC), who allegedly carried off these temples’ ritual tablets to Elam.[55] As a matter of fact, most historians agree that the colophon’s account, which states that Kidin-Anu found these ancient tablets there, copied them and brought them back to Uruk, is probably a pia fraus fabricated by the local priests to assert the antiquity of their temple and its cult.[56] This does not necessarily imply, however, that Kidin-Anu never travelled to Susa or that he did not copy Neo-Babylonian ritual texts there.[57] Be it as it may, TCL 6, 38 perfectly fits into the context of the restoration of the Bīt Rēš temple and its cult in the early third century BC documented by YOS 20, 87, to which we shall now turn our attention.

The Building Works on the Temple Complex

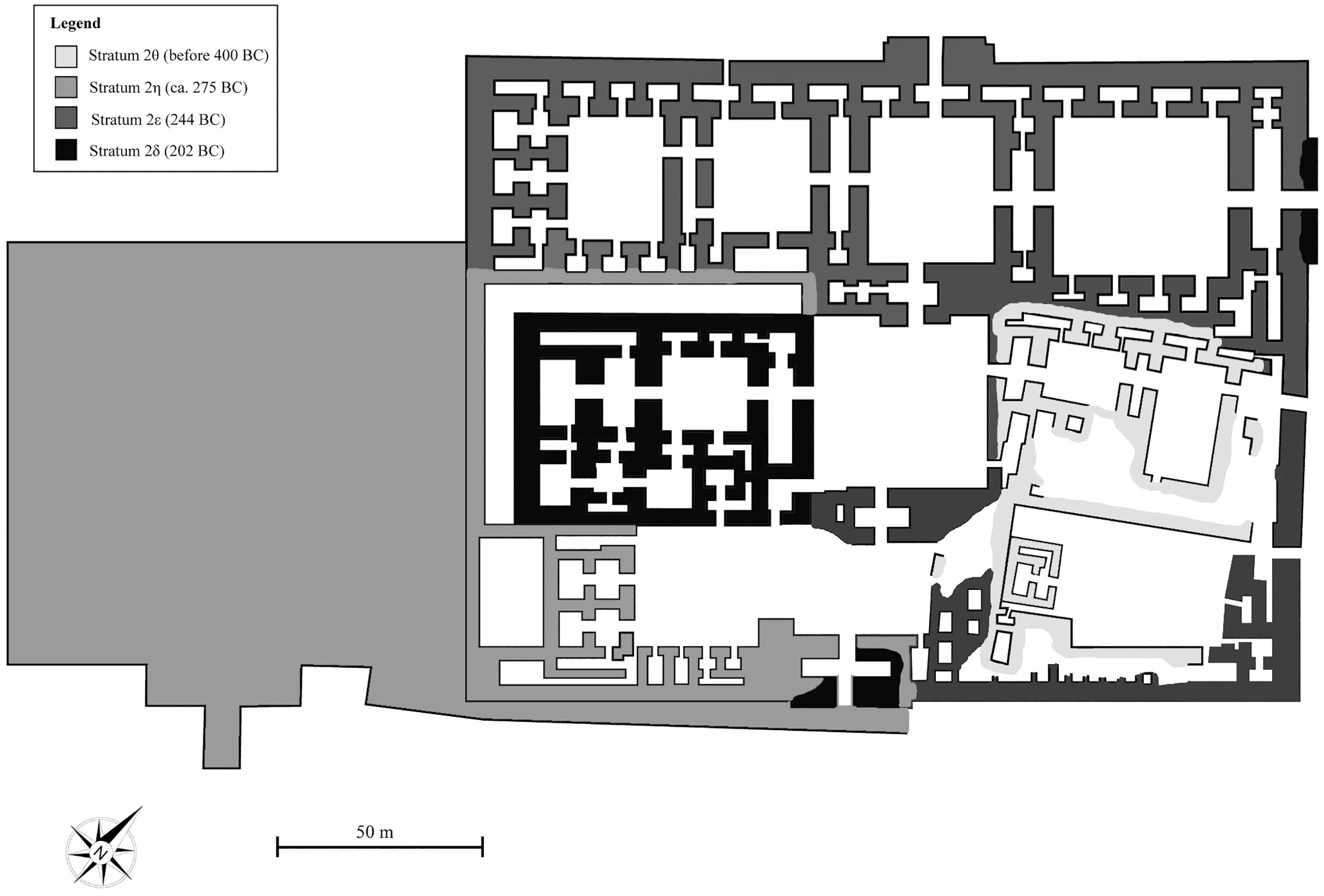

Despite their fragmentary state, the translated documents collected in YOS 20, 87 obviously focus on building works performed on the Bīt Rēš during the first quarter of the third century BC. Little is known of the temple’s early days: indirect evidence suggests that the first version of the cultic complex was probably built at some point between the seventh and the fifth century BC,[58] but by and large, the shrine remains poorly documented before the Macedonian conquest, due to the dearth of explicit written sources and to the fact that most of the archaeological remains of this initial state (stratum 2θ) have been destroyed by later renovations. It is commonly thought, however, that the so-called Schiefer Trakt excavated in the eastern part of the temple complex belongs to this initial stage (cf. Fig. 4).[59]

Schematic rendering of the four building phases of the Bīt Rēš, based on Kose (2013: 334).

The temple’s next building phase (stratum 2η) has long been identified on the ground: like its earlier counterpart, it was largely destroyed by later renovations, but the southwestern part of the complex still shows significant remains of this period. As a matter of fact, this phase seems to have been less a renovation than an extension of the temple complex: new buildings and courts were created next to the Schiefer Trakt including, presumably, a first version of the temple’s main cella, which has been completely destroyed by later renovations. Moreover, a new ziggurat dedicated to the god Anu – the largest monument of this kind ever built in Mesopotamia, in terms of ground surface – was erected to the southwest of the complex, over an earlier temple tower from the seventh century BC.[60]

Until now, however, this second phase could only be dated relatively to other archaeological strata, i.e., between the end of the fifth (stratum 2θ) and the middle of the third century BC (stratum 2ε)[61], as the written sources remained much more elusive on this phase than on the subsequent ones, initiated by the šaknu Anu-uballiṭ~Nikarchos (third phase, stratum 2ε) and the rab ša rēš āli Anu‑uballiṭ~Kephalon (fourth phase, stratum 2δ), which were completed in 244 and 202 BC respectively.[62] The new insight provided by YOS 20, 87, documenting building works on the Bīt Rēš complex, now allows us to securely date the archaeological stratum 2η to the first quarter of the third century BC.

A cursory reading of the tablet provides a chronological outline of these works: the first explicit reference to building activities appears in document D (l. 25), dated to 284/83 BC; documents E and F, which are datable to ca. 283–275 BC, both mention the fact that the works are still under way (ll. 29, 34, 35), while document G, in December 275 BC, refers to an official order concerning an assignment to rebuild the temple (l. 37 and perhaps l. 38). This last order may have enabled the completion of the temple’s extension, as the tablet does not record any later document. These milestones suggest that the Bīt Rēš’s second building phase probably lasted around a decade, between the mid-280s and the mid-270s BC, a time span which is broadly consistent with the estimated duration of the subsequent renovations (ca. 260–244 BC for the building works of the third phase, and ca. 215–202 BC for the fourth).[63]

It is also worth noting that unlike documents D-G, the preserved parts of documents A–C do not refer to building activities, but focus instead on cultic matters: cultic paraphernalia (l. 2) are mentioned in document A (ca. 290 BC), while document C (ca. 290–284 BC) refers to rituals and festivals (ll. 15–16), food offerings (ll. 16, 18, 21) and, most interestingly, to the transfer (abāku) of divine statues to Uruk (l. 17),[64] as well as the return (târu) of something related to the gods towards the city (l. 20). The use of these verbs, which contrasts with the mere “entry” (erēbu) of the divinity into the renovated sanctuary after a temporary sojourn in a nearby temple usually recorded in the cuneiform sources,[65] suggests that the cult statues installed in the cella of the Bīt Rēš after the temple’s second building phase were not in Uruk in the first half of the 280s BC.[66] In this regard, the building phase documented by YOS 20, 87 appears as a genuine refoundation of the local cult, in a much more fundamental way than the following works undertaken by Anu‑uballiṭ~Nikarchos and Anu‑uballiṭ~Kephalon.[67]

But if these cult statues were not located in the temple in the beginning of the third century BC, where were they? Although the answer to this question shall remain hypothetical in the present state of the documentation, the much-discussed colophon of TCL 6, 38 (cf. supra) provides an obvious parallel to the situation recorded in our tablet, since it refers to the plunder of ritual tablets containing, among other things, the “cultic ordinances of Anu” (r. 44–46) which were “carried off from Uruk” (r. 47) and later copied “in the land of Elam” by Kidin-Anu, who brought them back to the city (r. 47–50) at the time of Seleucus I and Antiochus I’s coregency (ca. 296–281 BC),[68] i.e., when YOS20, 87’s documents A–C record a refoundation of the temple’s cultic activities under the supervision of the same Kidin-Anu, assisted by the temple assembly of the “Urukeans”. This could suggest that the cult statues which were brought back to Uruk in the 280s BC were also formerly located in “the land of Elam,” i.e., Susiana, and that Kidin-Anu managed to transfer them back to Uruk, with the active support of the Seleucid Crown.

This parallel with TCL 6, 38, however, does not allow us to answer all the questions raised by the analysis of YOS 20, 87: How was the cult organised before this refoundation? And who was responsible for this situation? The former question lies entirely beyond the scope of the available documentation, be it textual or archaeological. As for the latter, many commentators have pointed out that, despite the assertions found in TCL 6, 38 (r. 47), the Neo-Babylonian king Nabu-apla-uṣur (626–605 BC) probably had nothing to do with this event, since the Bīt Rēš did not exist as such at the time.[69] In this regard, a Late Achaemenid king[70] or Antigonus Monophtalmus[71] would probably make more likely suspects for this cultic disruption. What is certain, in any case, is that the Seleucid involvement towards the Bīt Rēš went far beyond the mere funding of local building works: YOS 20, 87 indisputably shows an active support from the Crown, which enabled the Urukean authorities to organize a cultic refoundation in the Bīt Rēš, as well as a considerable extension of the city’s religious complex.[72]

Seleucid Euergetism in Babylonia

Being built in sun-dried and kiln-fired clay bricks, Mesopotamian temples had to be rebuilt from the foundations on a regular basis. As caretaker of the kingdom’s ritual activities, the king was traditionally expected to ensure that the sanctuaries did not fall into decay, and initiate renovation works when needed.[73] However, by the time of Alexander’s conquest, this tradition had been ignored by the rulers of Babylonia for two hundred years: the last king to comply was Cyrus II (539–530 BC), who had carried out building works in the Ekišnugal temple in Ur, and possibly in the Eanna in Uruk.[74] The available sources do not indicate that any of his successors performed this traditional duty until the Macedonian conquest in 331 BC, when Alexander decided to rebuild the Esagil complex in Babylon.[75] In doing so, the Macedonian king dissociated himself from Achaemenid practices, and revived the old Sumero-Akkadian custom of royal patronage over the temples, which in this respect echoed the Greek practice of euergetism.

Although the conqueror’s untimely death prevented him from completing this task, the first Seleucids decided to follow his path after the crisis of the Diadochi wars. This is especially true of Antiochus I, who spent some years in Babylonia in the early third century BC: it was then that he completed, with the help of his war elephants, the clearing of ruins of the Esagil complex, which had been initiated forty years earlier by Alexander;[76] moreover, we now know that he actively supported the extension of the Bīt Rēš complex in Uruk (completed around 275 BC), and the famous Antiochus Cylinder (5R66) shows that he also rebuilt the Esagil temple in Babylon (ca. 270 BC)[77] as well as the Ezida temple in Borsippa (ca. 268 BC).[78]

The considerable extension of the Bīt Rēš religious complex, resulting in the doubling of the size of the temple and the erection of the largest ziggurat ever built in Mesopotamia, was thus part of an active policy of religious euergetism conducted by the first Seleucids in Babylonia.[79] In this regard, YOS 20, 87’s mention of queen Apama, who was Seleucus’ spouse and Antiochus’ mother, in 284/83 BC (l. 24), is particularly interesting,[80] as her interaction with two Seleucid officials in the context of the Bīt Rēš’s building works is highly reminiscent of her agency in the renovation of the oracular sanctuary at Didyma, fifteen years earlier.[81] Both interventions accord with the documented support by Hellenistic queens for religious institutions and festivals as one of the key avenues for female royal benefaction.[82]

Similarly, the many references to official orders (ṭēmu, ll. 4, 11, 19, 36, 37 and 39) and/or royal letters (l. 13) recorded over more than fifteen years for the sole refoundation of the Bīt Rēš, show an actual involvement from the first Seleucids in this kind of euergetism, in accordance with the long-known testimony of the Antiochus Cylinder – although the cylinder’s assertion that the king made a personal trip from the Levant to Borsippa to attend the ceremonial laying of Ezida’s new foundations in 268 BC should probably be taken with a pinch of salt.[83]

Antiochus I, however, was one of the very last heirs to the multimillennial Sumero-Akkadian tradition of royal support to temple building. After his death in 261 BC, Seleucid support in favour of Babylonian temples gradually evolved towards new – and cheaper – forms of euergesia, such as land grants and tax exemptions for Babylonian cities.[84] Although the temple assemblies indirectly benefitted from these donations through their role as managing institutions of these cities during the third century BC, the transformation of several of these cities into poleis in the early second century BC inverted this situation, by gradually subordinating the management of temple affairs to the control of the new polis institutions.[85] By that time, the age-old tradition of royal support for lavish temple renovations, which had been revived a century earlier by the first Seleucids, was long gone.

Concluding Remarks

Despite its poor state of conservation, which leaves many questions unanswered, YOS 20, 87 provides extremely valuable insights into an otherwise poorly documented period of Uruk’s history, as well as a significant addition to the corpus of Seleucid official correspondence. One last point, however, remains to be addressed, which concerns the purpose of the document. It appears methodologically unsound to attempt to link its proposed dating (probably the early second century BC for the tablet, and possibly the middle of the third century BC for the text itself) to any contemporaneous event or any kind of revendication: the text was written in cuneiform Akkadian, a language and script only understood by temple scholars at the time. Having no external audience and no proper legal value, YOS 20, 87 was therefore relevant only to the priestly community itself. Why these official documents were originally translated, compiled and later copied by local scribes is a complex question, which cannot be clarified in detail, but probably involved considerations on the historical and institutional memory of the Bīt Rēš.

In this regard, our tablet finds an interesting biblical parallel in Ezra 1–6, which can be dated to the late fourth century BC:[86] the text gives an account of the building of the Second Temple two centuries earlier, and extensively quotes royal letters sent by the Persian kings – one of which is translated to Hebrew –, in order to account for delays in the building works in Jerusalem, and to keep a record of the goodwill shown by the Persian kings towards the temple community.[87] Although this piece of priestly scholarship later became an integral part of the Biblical Canon, there is reason to believe that it was originally a local account of the refoundation of the Yahwistic cult in Jerusalem.[88] Likewise, YOS 20, 87, which also records translated royal letters concerning building works and cult refoundation, was probably meaningful to a small number of local priests only, beginning with the owner of the tablet, Šamaš-ēṭir, who may have been Kidin-Anu’s own great grandson.[89]

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Yale Babylonian Collection for their kind assistance in our study of the tablet, as well as to Paul-Alain Beaulieu, Boris Chrubasik, Francis Joannès, Mathieu Ossendrijver, Anne-Emmanuelle Veïsse, Marie Widmer and Marie Young for their help in the elaboration of this article. Any remaining error would naturally be our own.

Bibliography

Ambos, C. (2007): Ricostruire un tempio per nuocere al re: rituali mesopotamici di fondazione, il loro posto nel culto et il loro impiego come arma politica, Kaskal 4, 297–314.Suche in Google Scholar

Beaulieu, P.-A. (1993): The Historical Background of the Uruk Prophecy. In: M. Cohen et al. (ed.), The Tablet and the Scroll. Near Eastern Studies in Honour of William W. Hallo, Bethesda, 41–52.Suche in Google Scholar

Beaulieu, P.-A. (1994): Late Babylonian Texts in the Nies Babylonian Collection (CBCY 1), Bethesda.Suche in Google Scholar

Beaulieu, P.-A. (2003): The Pantheon of Uruk during the Neo-Babylonian Period (CunMon. 23), Leiden ‒ Boston.10.1163/9789004496804Suche in Google Scholar

Beaulieu, P.-A. (2018): Uruk Before and After Xerxes: The Onomastic and Institutional Rise of the God Anu. In: C. Waerzeggers/M. Seire (ed.), Xerxes and Babylonia: The Cuneiform Evidence (OLA 277), Leuven ‒ Paris ‒ Bristol, 189–206.10.2307/j.ctv1q26v46.12Suche in Google Scholar

Beaulieu, P.-A. (2021): Remarks on Word Order and the Syntax of ša-Clauses in Late Hellenistic Babylonian. In: R. Hasselbach-Andee/N. Pat-El (ed.), Bēl Lišāni: Current Research in Akkadian Linguistics (Explorations in Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations 8), University Park (PA), 9–40.10.1515/9781646021598-003Suche in Google Scholar

Bencivenni, A. (2011): Massima Considerazione: forma dell’ordine e immagini del potere nella corrispondenza di Seleuco IV, ZPE 176, 139–153. Suche in Google Scholar

Bielman Sánchez, A. (2003): Régner au féminin: réflexions sur les reines attalides et séleucides. In: F. Prost (ed.), L’Orient méditerranéen, de la mort d’Alexandre aux campagnes de Pompée, Rennes ‒ Toulouse, 41–61.10.4000/books.pur.19439Suche in Google Scholar

Bikerman, E. (1938): Institutions des Séleucides, Paris.10.4000/books.ifpo.5413Suche in Google Scholar

Boiy, T. (2010): TU 38, Its Scribe and His Family, RA 104, 169–178. 10.3917/assy.104.0169Suche in Google Scholar

Bertrand, J.-M. (1985): Formes de discours politiques: décrets des cités grecques et correspondance des rois hellénistiques, Revue historique de droit français et étranger 63, 469–482.Suche in Google Scholar

Capdetrey, L. (2007): Le pouvoir séleucide: territoire, administration, finances d’un royaume hellénistique (312–129 avant J.-C.), Rennes.10.4000/books.pur.6126Suche in Google Scholar

Cavigneaux, A. (2005): Shulgi, Nabonide et les Grecs. In: Y. Sefati et al. (ed.), An Experienced Scribe who Neglects Nothing. Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Jacob Klein, Bethesda, 63–72.Suche in Google Scholar

Ceccarelli P. (2013). Ancient Greek Letter Writing: A Cultural History (600–150 BC), Oxford.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199675593.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Charpin, D. (2008): Lire et écrire à Babylone, Paris.10.3917/puf.char.2008.01Suche in Google Scholar

Clancier, Ph. (2009): Les bibliothèques en Babylonie dans la deuxième moitié du Ier millénaire av. J.-C. (AOAT 363), Münster.Suche in Google Scholar

Clancier Ph. (2014): Teaching and Learning Medicine and Exorcism at Uruk during the Hellenistic Period. In: A. Bernard/C. Proust (ed.), Scientific Sources and Teaching Contexts Throughout History: Problems and Perspectives (Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science 301), Dordrecht ‒ London, 41–66.10.1007/978-94-007-5122-4_3Suche in Google Scholar

Clancier, Ph. (2017): The Polis of Babylon: A Historiographical Approach. In: B. Chrubasik/D. King (ed.), Hellenism and the Local Communities of the Eastern Mediterranean, Oxford, 53–81.Suche in Google Scholar

Clancier Ph./J. Monerie (2014): Les sanctuaires babyloniens à l’époque hellénistique: évolution d’un relais de pouvoir, Topoi 19, 181–237. 10.3406/topoi.2014.2535Suche in Google Scholar

Cohen, G. (2006), The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin and North Africa, Berkeley – Los Angeles – London.10.1525/california/9780520241480.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Corò, P. (2005): Esorcisti e prebende dell’esorcista nella Babilonia di I millennio: il caso di Uruk, StCl.Or. 51, 11–24.Suche in Google Scholar

Corò, P. (2018): Seleucid Tablets from Uruk in the British Museum: Text Editions and Commentary (Antichistica 16), Venice.10.30687/978-88-6969-246-8/010Suche in Google Scholar

Cotton-Paltiel, H. et al. (2017): Juxtaposing Literary and Documentary Evidence: A New Copy of the So-called Heliodoros Stele and the Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae (CIIP), Bulletin of the Institut of Classical Studies 60, 1–15.10.1111/2041-5370.12044Suche in Google Scholar

Debourse, C. (2022): Of Priests and Kings: The Babylonian New Year Festival in the Last Age of Cuneiform Culture, (CHANE 127), Leiden – Boston.10.1163/9789004513037Suche in Google Scholar

Doty, L.T./R. Wallenfels (2012): Cuneiform Documents from Hellenistic Uruk (YOS 20), New Haven – London.Suche in Google Scholar

Engels, D./K. Erickson (2016): Apama and Stratonike: Marriage and Legitimacy. In: A. Coşkun/A. McAuley (ed.), Seleukid Royal Women: Creation, Representation and Distortion of Hellenistic Queenship in the Seleukid Empire (Historia Einzelschriften 240), Stuttgart, 39–65.Suche in Google Scholar

Erickson, K. (2011), Apollo-Nabû: The Babylonian Policy of Antiochus I. In: K. Erickson/G. Ramsay (ed.), Seleucid Dissolution: The Sinking of the Anchor (Philippika 50), Wiesbaden, 51–66. Suche in Google Scholar

Escobar E./L. Pearce (2018): Bricoleurs in Babylonia: The Scribes of Enūma Anu Enlil. In: J. Crisostomo et al. (ed.), The Scaffolding of our Thoughts. Essays on Assyriology and the History of Science in Honour of Francesca Rochberg (AMD 13), Leiden ‒ Boston, 264–286. 10.1163/9789004363380_014Suche in Google Scholar

Frahm, E. (2005). On Some Recently Published Late Babylonian Copies of Royal Letters, NABU 2005/43. Suche in Google Scholar

Fried, L. (2003): The Land Lay Desolate: Conquest and Restoration in the Ancient Near East. In: O. Lipschits/J. Blenkinsopp (ed.), Judah and the Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period, Winona Lake, 21–54.10.1515/9781575065403-003Suche in Google Scholar

Fried, L. (2012): Ezra’s Use of Documents in the Context of Hellenistic Rules of Rhetoric. In: I. Kalimi (ed.), New Perspectives on Ezra-Nehemiah: History and Historiography, Text, Literature, and Interpretation, Winona Lake, 11–26.Suche in Google Scholar

Grabbe, L. (2006): The Persian Documents in the Book of Ezra: Are They Authentic? In: O. Lipschits/M. Oeming (ed.), Judah and the Judeans in the Persian Period, Winona Lake, 531–570.10.5325/j.ctv1bxgzgk.25Suche in Google Scholar

Hackl, J. (2013): Materialen zur Urkundenlehre und Archivkunde der spätzeitlichen Texte aus Nordbabylonien, Vol. 2, PhD Universität Wien. Suche in Google Scholar

Hackl, J. (2018): The Esangila Temple during the Late Achaemenid Period and the Impact of Xerxes’ Reprisals on the Northern Babylonian Temple Households. In: C. Waerzeggers/M. Seire(ed.), Xerxes and Babylonia: The Cuneiform Evidence (OLA 277), Leuven – Paris – Bristol, 165–187.10.2307/j.ctv1q26v46.11Suche in Google Scholar

Hackl, J. (2020): Bemerkungen zur Chronologie der Seleukidenzeit: Die Koregentschaft von Seleukos I. Nikator und Antiochos (I. Soter), Klio 102, 560–578. 10.1515/klio-2019-1006Suche in Google Scholar

Hackl, J. (in press): Language Death and Dying Reconsidered: The Rôle of Late Babylonian as a Vernacular Language. In: L. Cogan (ed.), The Neo-Babylonian Workshop of the 53rd Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale (Moskau & St. Petersburg), Dresden. Suche in Google Scholar

Harders, A.-C. (2016): The Making of a Queen – Seleukos Nikator and his Wives. In: A. Coşkun/A. McAuley (ed.), Seleukid Royal Women: Creation, Representation and Distortion of Hellenistic Queenship in the Seleukid Empire (Historia Einzelschriften 240), Stuttgart, 25–38.Suche in Google Scholar

Holleaux, M. (1933): Une inscription de Séleucie-de-Piérie, BCH 57, 6–67. 10.3406/bch.1933.2815Suche in Google Scholar

Horowitz, W. (1991): Antiochus I, Esagil, and a Celebration of the Ritual for Renovation of Temples, RA 85, 75–77. Suche in Google Scholar

Joannès, F. (2001): Les débuts de l’époque hellénistique à Larsa. In: C. Breniquet/C. Kepinski (ed.), Études mésopotamiennes. Recueil de textes offerts à Jean-Louis Huot, Paris, 249–264. Suche in Google Scholar

Jursa M./C. Debourse(2017): A Babylonian Priestly Martyr, a King-Like Priest, and the Nature of the Late Babylonian Priestly Literature, WZKM 107, 77–98. Suche in Google Scholar

Kose, A. (1998): Uruk: Architektur IV (AUWE 17), Mainz.Suche in Google Scholar

Kose, A. (2013): Das seleukidische Resch-Heiligtum. In: N. Crüsemann (ed.), Uruk: 5000 Jahre Megacity, Petersberg, 333–339.Suche in Google Scholar

Kosmin, P. (2014): Seeing Double in Babylonia: Rereading the Borsippa Cylinder of Antiochus I. In: A. Moreno/R. Thomas (ed.), Patterns of the Past: Epitēdeumata in the Greek Tradition, Oxford, 173–198.10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199668885.003.0009Suche in Google Scholar

Krul, J. (2018): The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk (CHANE 95), Leiden – Boston.10.1163/9789004364943Suche in Google Scholar

Kuhrt, A. (2007): The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period, London – New York.Suche in Google Scholar

Levavi, Y. (2018): Administrative Epistolography in the Formative Phase of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (dubsar 3), Münster.10.2307/jj.18654693Suche in Google Scholar

Linssen, M. (2004): The Cults of Babylon and Uruk. The Temple Ritual Texts as Evidence for Hellenistic Cult Practices (CunMon. 25), Leiden – Boston.Suche in Google Scholar

Ma, J. (1999): Antiochos III and the Cities of Western Asia Minor, Oxford.10.1093/oso/9780198152194.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Marcellesi, M.-C. (2004): Milet et les Séleucides: aspects économiques de l’évergétisme royal, Topoi Suppl. 6, 165–188. Suche in Google Scholar

McEwan, G. (1986): A Seleucid Tablet in the Redpath Museum, ARRIM 4, 35–36.Suche in Google Scholar

Monerie, J. (2014): D’Alexandre à Zôilos: dictionnaire prosopographique des porteurs de nom grec dans les sources cunéiformes (Oriens et Occidens 23), Stuttgart.Suche in Google Scholar

Monerie, J. (2015): More than a Workman? The Case of the ēpeš dulli ṭīdi ša bīt ilāni from Hellenistic Uruk, Kaskal 12, 411–448. Suche in Google Scholar

Monerie, J. (2018): L’économie de la Babylonie à l’époque hellénistique (SANER 14), Boston – Berlin.10.1515/9781501502200Suche in Google Scholar

Müller, S. (2013): The Female Element of the Politic Self-Fashioning of the Diadochi: Ptolemy, Seleucus, Lysimachus, and their Iranian Wives. In: V. Alonso Troncoso/E. Anson (ed.), After Alexander: The Time of the Diadochi (323–281 BC), Oxford, 199–214. Suche in Google Scholar

Olszewski M./H. Saad (2018): Pella-Apamée sur l’Oronte et ses héros fondateurs à la lumière d’une source historique inconnue: une mosaïque d’Apamée. In: M.P. Castiglioni et al. (ed.), Héros fondateurs et identités communautaires dans l’Antiquité entre mythe, rite et politique (Quaderni di Otium 3), Perugia, 365–408. Suche in Google Scholar

Ossendrijver, M. (2011a): Exzellente Netzwerke: Die Astronomen von Uruk. In: G. Seltz/K. Wagensonner (ed.), The Empirical Dimension of Ancient Near Eastern Studies (WOO 6), Vienna, 631–644. Suche in Google Scholar

Ossendrijver, M. (2011b): Science in Action: Networks in Babylonian Astronomy. In: E. Cancik-Kirschbaum et al. (ed.), Babylon: Wissenskultur in Orient und Okzident (Topoi – Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 1), Boston – Berlin, 213–221. 10.1515/9783110222128.213Suche in Google Scholar

Ossendrijver, M. (2020): Scholars in the Footsteps of Kidin-Anu: On a group of Colophons from Seleucid Uruk. In: J. Baldwin/J. Matuszak (ed.), mu-zu an-za3-še3 kur-ur2-še3 ḫe2-gal2. Altorientalische Studien zu Ehren von Konrad Volk (dubsar 17), Münster, 313–336. 10.2307/jj.18654682.18Suche in Google Scholar

Ramsay, G. (2016): The Diplomacy of Seleukid Women: Apama and Stratonike. In: A. Coşkun/A. McAuley (ed.), Seleukid Royal Women: Creation, Representation and Distortion of Hellenistic Queenship in the Seleukid Empire (Historia Einzelschriften 240), Stuttgart, 87–104.Suche in Google Scholar

Robson, E. (2007): Secrets de famille: prêtre et astronome à Uruk. In: C. Jacob (ed.), Les lieux de savoir. Vol. 1 : Lieux et communautés, Paris, 440–461. Suche in Google Scholar

Robson, E. (2008): Mathematics in Ancient Iraq: A Social History, Princeton. 10.1515/9780691201405Suche in Google Scholar

Rutz, M. (2006): Textual Transmission between Babylonia and Susa: A New Solar Omen Compendium, JCS 58, 63–96. 10.1086/JCS40025224Suche in Google Scholar

Safaee, Y. (2017): A Local Revolt in Babylonia during the Reign of Darius III, Dabir 4, 50–56. 10.1163/29497833-00401007Suche in Google Scholar

Sciandra, R. (2012): The Babylonian Correspondence of the Seleucid and Arsacid Dynasties: New Insights into the Relations between Court and City during the Late Babylonian Period. In: G. Wilhelm (ed.), Organization, Representation and Symbols of Power in the Ancient Near East (CRRAI 54), Winona Lake, 225–248. 10.1515/9781575066752-023Suche in Google Scholar

Schaudig, H. (2010): The Restoration of Temples in the Neo- and Late Babylonian Periods. In: M. Boda/J. Novotny (ed.), From the Foundations to the Crenellations: Essays on Temple Building in the Ancient Near East and Hebrew Bible (AOAT 366), Münster, 141–164. Suche in Google Scholar

Stevens, K. (2013): Secrets in the Library: Protected Knowledge and Professional Identity in Late Babylonian Uruk, Iraq 75, 211–253. 10.1017/S0021088900000474Suche in Google Scholar

Stevens, K. (2014): The Antiochus Cylinder, Babylonian Scholarship and Seleucid Imperial Ideology, JHS 134, 66–88. 10.1017/S0075426914000068Suche in Google Scholar

van der Spek, R. (2001): The Theatre of Babylon in Cuneiform. In: W. van Soldt et al. (ed.), Veenhof Anniversary Volume. Studies Presented to Klaas R. Veenhof on the Occasion of his Sixty-fifth Birthday (PIHANS 89), Leiden, 445–456. Suche in Google Scholar

Virgilio, B. (2011): Le roi écrit: la correspondance du souverain hellénistique, suivie de deux lettres d’Antiochos III à partir de Louis Robert et d’Adolf Wilhelm (Studi Ellenistici 25), Pisa.Suche in Google Scholar

Waerzeggers, C. (2010): The Ezida Temple of Borsippa: Priesthood, Cult, Archives (Achaemenid History 15), Leiden. Suche in Google Scholar

Waerzeggers, C. (2011): The Pious King: Royal Patronage of Temples. In:E. Robson/K. Radner (ed.), Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, Oxford, 725–751.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199557301.013.0034Suche in Google Scholar

Welles, C.B. (1934). Royal Correspondence in the Hellenistic Period: A Study in Greek Epigraphy, Chicago. Suche in Google Scholar

Widmer M. (2016): Apamè: une reine au cœur de la construction d’un royaume. In: A. Bielman Sánchez et al. (ed.), Femmes influentes dans le monde hellénistique et à Rome, Grenoble, 17–33.10.4000/books.ugaeditions.3281Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Dieses Werk ist lizensiert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Vorwort der Herausgeberinnen und Herausgeber

- Notes on Two Amulets (Tyszkiewicz and de Serres) Inscribed with Sumerian Incantations

- The Eponyms of the Babylonian War of Tukultī-Ninurta I

- Some Reflections on the Use and the Meaning of the Sign lugal in Urartian Inscriptions

- On the Periphery of the Clerical Community of Old Babylonian Ur

- Murder in Anatolia

- A Compendium of Official Correspondence from Seleucid Uruk

- Annäherungen an die Bedeutung und Funktion von šaḫūrū in altmesopotamischen Bauwerken

- Resizing Phrygia: Migration, State and Kingdom

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Vorwort der Herausgeberinnen und Herausgeber

- Notes on Two Amulets (Tyszkiewicz and de Serres) Inscribed with Sumerian Incantations

- The Eponyms of the Babylonian War of Tukultī-Ninurta I

- Some Reflections on the Use and the Meaning of the Sign lugal in Urartian Inscriptions

- On the Periphery of the Clerical Community of Old Babylonian Ur

- Murder in Anatolia

- A Compendium of Official Correspondence from Seleucid Uruk

- Annäherungen an die Bedeutung und Funktion von šaḫūrū in altmesopotamischen Bauwerken

- Resizing Phrygia: Migration, State and Kingdom