Abstract

Background

While lower socioeconomic status increases individual’s risk for chronic conditions, little is known about how long-term social assistance recipients (LTRs) with multiple chronic health problems experience chronic pain and/or psychological distress. Social assistance is the last safety net in the Norwegian welfare system and individuals have a legal right to economic assistance if they are unable to support themselves or are entitled to other types of benefits. The purposes of this study were to determine the co-occurrence of both chronic pain and psychological distress and to evaluate for differences in demographic and social characteristics, as well as health-related quality of life, among LTRs.

Methods

This descriptive, cross-sectional study surveyed people receiving long-term social assistance in Norway about their health and social functioning from January-November 2005. The social welfare authority offices in each of 14 municipalities in Norway were responsible to locate the LTRs who met the study’s inclusion criteria. The selected municipalities provided geographic variability including both rural and urban municipalities in different parts of the country. LTRs were included in this study if they: had received social assistance as their main source of income for at least 6 of the last 12 months; were between 18 and 60 years of age; and were able to complete the study questionnaire. In this study, 405 LTRs were divided into four groups based on the presence or absence of chronic pain and/or psychological distress. (1) Neither chronic pain nor psychological distress (32%, n = 119), (2) only chronic pain (12%, n = 44), (3) only psychological distress and (24%, n = 87), (4) both chronic pain and psychological distress (32%, n =119).

Results

Except for age and marital status, no differences were found between groups in demographic characteristics. Significant differences were found among the four groups on all of the items related to childhood difficulties before the age of 16, except the item on sexual abuse. LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress were more likely to have experienced economic problems in their childhood home; other types of abuse than sexual abuse; long-term bullying; and had more often dropped out of school than LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress. LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress, reported more alcohol and substance use/illicit drug use, more feelings of loneliness and a lower mental score on SF-12 than LTRs with only chronic pain.

Conclusions and implications

Co-occurrence of chronic pain and psychological distress is common in LTRs and problems in early life are associated with the co-occurrence of chronic pain and psychological distress in adult life. Although this study cannot assign a clear direction or causality to the association between social and demographic characteristics and chronic pain and psychological distress, the findings when examining LTRs’ problems in childhood before the age of 16, indicated that incidents in early life create a probability of chronic pain and psychological distress in the adult life of the individuals. Further studies should use life course studies and longitudinal data in to investigate these important questions in LTRs.

1 Introduction

Social assistance is the last safety net in the Norwegian welfare system. Individuals have a legal right to economic assistance if they are unable to support themselves or are entitled to other types of benefits [1]. In 2011, approximately 3.1% of the adult population received social assistance [2], and 35% of these individuals were long-term social assistance recipients (LTRs) defined as having received social assistance at least 6 of the last 12 months [3].

Many LTRs have had a troubled childhood [4,5] and have experienced parents with substance abuse and mental health problems. Compared to the general population, LTRs have less education, little human capital, scarce financial and material resources [6,7], relatively poor physical and mental health (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, pain, anxiety, depression, drug abuse), and poorer quality of life [8, 9, 10]. In 2009, over 50% of LTRs had incomes at or below the poverty level [11]. LTRs have a higher mortality rate than the general population and higher rates of alcohol and illicit drug use. It is of note, violence contributes to half of the excess mortality in men, and one-third in women who are LTRs [12].

Findings from numerous studies suggest that chronic pain and psychological distress co-occur (e.g., patients with chronic pain report higher levels of depression, fear, and anxiety) [13, 14, 15, 16]. However, not every individual with psychological distress has chronic pain or vice versa. Also, no agreement exists on the causal relationships between these two conditions. In general, being female, older age, lower socioeconomic status, being unemployed; having a history of abuse or interpersonal violence, increase or are associated with chronic pain [17] and psychological distress [18, 19, 20]. Most of these associations however, were evaluated in individuals with either chronic pain or psychological distress. While lower socioeconomic status increases an individual’s risk for chronic conditions [21], little is known about how LTRs with multiple chronic health problems experience chronic pain and/or psychological distress.

In previous work, we have identified that 44% of LTRs reported chronic pain [22], and that 57% had psychological distress [23]. LTRs with chronic pain had a lower health-related quality of life than LTRs without chronic pain. The same goes for LTRs of younger age, presence of chronic pain, loneliness, and alcohol and drug abuse. These characteristics were also associated with lower health-related quality of life [24].

Given the paucity of research on the co-occurrence of chronic pain and psychological distress and its associations with salient demographic and social characteristics in the same individuals into all on long-term social assistance, in this paper we extend our findings from previous studies specifically. In a sample of LTRs (n = 405) the purpose of this study is to determine the occurrence of both chronic pain and psychological distress and evaluate for differences in demographic and social characteristics, as well as health related quality of life. LTRs are classified into one of four groups (i.e. neither chronic pain nor psychological distress, only chronic pain, only psychological distress, chronic pain and psychological distress).

2 Methods

2.1 Design and data collection procedures

A detailed description of the methods is reported elsewhere [22,25]. In brief, this study is part of a larger study, entitled: “The study of functional ability among long-term social assistance recipients”. The study was funded by the Directorate for Health and Social Affairs in Norway after an evaluation of “The National Activation Trial” from 2000 to 2004 [26], which was done to promote and support new ways to move LTRs away from benefit dependency into work. This descriptive, cross-sectional study surveyed people receiving long-term social assistance in Norway about their health and social functioning from January to November 2005.

The social welfare authority offices in each of 14 municipalities in Norway were responsible to locate the LTRs who met the study’s inclusion criteria. The respondents were sent the survey questionnaires, and they returned them directly using a postage paid envelope to Oslo University College. LTRs who did not reply received two mailed reminders. Some LTRs who did not respond to the mailed reminders were telephoned, while others were reminded to complete the questionnaires by case workers. These extensive data collection procedures were used because previous experience has demonstrated that LTRs can be difficult to reach. Some relocate and change their addresses frequently or live at an unknown residence; others stay temporarily in shelters, hospitals, institutions, or prison.

2.2 Sample

The selected municipalities provided geographic variability including both rural and urban municipalities in different parts of the country. LTRs were included in this study if they: had received social assistance as their main source of income for at least 6 of the last 12 months, were between 18 and 60 years of age, and were able to complete the study questionnaire.

In this study, 1291 LTRs met the initial inclusion criteria. However, 225 of these individuals were pre-screened by case workers and were considered to be unable to complete the questionnaire due to severe substance abuse problems, insufficient mastery of the Norwegian language, extensive problems with reading and writing, or serious illness. Therefore, 1066 LTRs were included and, of that number, 562 responded (i.e., response rate of 52.7%). Administrative data (“FD-trygd”) were used to compare the 1291 recipients who met the inclusion criteria with those who responded to the questionnaire. No differences in age, gender, and previous receipt of social assistance or social security benefits were found between those LTRs who did and those who did not return the study questionnaires [27].

2.3 Ethics

When research is done with vulnerable groups, special attention needs to be given to research ethics. This study was planned and performed in a way that protected the LTRs from violations of their right to privacy. Completion of the questionnaires indicated informed consent. The study, including the number of reminders, was approved by the Data Inspectorate and the National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities.

2.4 Instruments

2.4.1 Sociodemographic characteristics

Data on age, gender, marital status, education, ethnic minority status, and work history were obtained from the LTRs.

2.4.2 Pain

Pain was assessed using a nine-item questionnaire that evaluated the presence of pain, and if present, its cause, location, duration, intensity, and treatments. In this study, LTRs were categorized into pain groups based on their responses to a screening question about whether or not they were generally in pain. In the present study, only the presence and duration of pain (i.e., being in chronic pain versus not being in chronic pain) is used in the analysis. The duration of pain is used as the sole instrument because it is the most relevant way of measuring chronic pain. Chronic pain was defined as pain of >3 months duration. For the LTR group who answered “yes” to the question “Do you generally have pain?” the response to the duration question was analyzed. Those LTRs whose pain duration was >3 months were classified as “chronic pain patients”. Those LTRs whose pain duration was ≤3 months were classified as “not being in chronic pain”.

2.4.3 Psychological distress

The 10-item Hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL-10) was used to evaluate psychological distress. HSCL is one of the most widely used questionnaires for evaluating psychiatric symptoms and deviant behaviour and has earlier been used in patients with chronic pain. A total HSCL-10 score is calculated as the mean of the 10 individual items. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). HSCL-10 has a cut point of 1.85 [28] which is recommended as a valid predictor of mental disorders as assessed independently by a clinical interview. Cronbach’s alpha for the HSCL-10 in LTRs was 0.92.

2.4.4 Childhood difficulties before the age of 16

The items that evaluated childhood’s difficulties before the age of 16 were used in a previous Norwegian study about living conditions among inmates in prisons [29]. In this study, 7 difficulties were evaluated using a, yes/no format. LTRs were asked “Did you experience any of the following problems before the age of 16?”: economic problems in childhood home, conflicted relationships between your parents, parents’ abuse of alcohol and drugs, sexual abuse, other types of abuse, long-term bullying, and dropped out of school.

2.5 Health

2.5.1 Alcohol and substance use/illicit drug use questionnaire

Two questions were asked about whether the LTRs now were or previously had been experiencing problems with alcohol and substance/illicit drug use (i.e., yes, “yes some”, collapsed to yes (1) “not now, but earlier”, and “no” collapsed to no (2). These items were developed and pilot tested for this study.

2.5.2 Feeling lonely

LTRs were asked “Does it happen that you often, sometimes, seldom, or never (seldom and never were collapsed) feel lonely?” This question was used in previous studies of the Norwegian general population by Statistics Norway [30].

2.6 Quality of life

2.6.1 Life Satisfaction

A single item (i.e., “How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your life overall”? assessed life satisfaction. The response ranged from “very satisfied” (1) to “very dissatisfied” (5) using a 5-point Likert scale [31]. In this study, “very satisfied” and “satisfied” were collapsed to “satisfied”, and “very dissatisfied” and “dissatisfied” were collapsed to “dissatisfied”.

2.6.2 Health-related quality of life

The Short-Form Health Survey (12 SF-12) was used to evaluate health-related quality of life. The SF-12 is a self-administered multi-dimensional instrument. The Norwegian version consists of 12 questions about physical and mental health [32,33]. In this study, participants were asked to respond to each of the 12 items in relationship to “the last four weeks”. The instrument is scored into two components that measure physical (i.e. physical component summary scale (PCS) and mental (i.e. mental component summary scale (MCS)). The scores on PCS and MCS are transformed into a0to100 scale. Higher scores indicate a better health-related quality of life. The scores are standardized based on United States general population norms so that a score of 50 corresponds to the mean score for this population [32].

2.7 Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows (version 22.0). Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were used to describe the characteristics of the sample. In order to create the four chronic pain and psychological distress groups, LTRs were categorized based on their chronic pain status (i.e., chronic pain or no chronic pain and their score on the HSCL-10 (i.e., <1.85 (no psychological distress) or >1.85 (psychological distress)). Only individuals who had complete data on all 10 items of the HSCL-10 or could be clearly placed in either the chronic pain or no chronic pain groups (n = 369) were included in this analysis. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) and Chi Square analyses were used to evaluate for differences in demographic, social, health, substance use/illicit drug use characteristics, and childhood difficulties among the four groups. If the overall ANOVA, or Chi Square tests indicated significant differences among the four groups (p-value of <0.05), pairwise contrasts were done to determine where the differences were. If the Bonferroni procedure was used across the six possible pairwise contrasts (i.e., 0.05/6), the p-value needed to be <0.008 to be considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Distribution of the chronic pain and psychological distress groups

As shown in Table 1, the LTRs were divided into four groups based on the presence or absence of chronic pain and/or psychological distress. One group had neither chronic pain nor psychological distress (32% n = 119). One group reported having only chronic pain (12% n = 44), one group reported having only psychological distress but not chronic pain (24% n = 87), and one group reported having both chronic pain and psychological distress (32% n = 119).

Differences in socio-demographic characteristics between long-term social assistance recipients (LTRs) with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress, LTRs with only chronic pain, LTRs with only psychological distress and LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress.

| Characteristics | LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress (0) N = 119 (32%) | LTR with only chronic pain (1) N = 44 (12%) | LTR with only psychological distress (2) N =87 (24%) | LTR with chronic pain and psychological distress (3) N =119 (32%) | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.1 (10.3) | 38.8 (11.3) | 32.1 (10.2) | 36.1 (10.4) | F (3,355) = 8.23; p <.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 0<1,3; 1 >2 | ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 69 (58.0) | 24 (54.5) | 57 (65.5) | 67 (56.3) | X2 = 2.29; p = 515 |

| Female | 50 (42.0) | 20 (45.5) | 30 (34.5) | 52 (43.7) | |

| Education | |||||

| Primary school | 46 (39.3) | 21 (48.8) | 46 (55.4) | 59 (51.3) | X2 = 8.24; p = .221 |

| Secondary school | 58 (49.6) | 17 (39.6) | 32 (38.6) | 50 (43.5) | |

| College/University | 13 (11.1) | 5 (11.6) | 5 (6.0) | 6 (5.2) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/cohabitant | 29 (24.4) | 13 (29.6) | 10 (11.5) | 28 (23.7) | X2 = 19.17; p = .004 |

| Never married | 67 (56.3) | 17 (38.6) | 64 (73.6) | 59 (50.0) | Never married |

| Divorced/separated | 23 (19.3) | 14 (31.8) | 13 (14.9) | 31 (26.3) | 1 <2; 2>3 |

| Lives alone | |||||

| Yes | 55 (46.2) | 20 (45.5) | 48 (57.1) | 61 (52.1) | X 2 =2.93; p = .403 |

| No | 64 (53.8) | 24 (54.5) | 36 (42.9) | 56 (47.9) | |

| Ethnic minority | |||||

| Yes | 18 (19.8) | 9 (28.1) | 8 (11.3) | 20 (23.0) | X 2 = 5.25; p = .155 |

| No | 73 (80.2) | 23 (71.9) | 63 (88.7) | 67 (77.0) | |

| Never employed at least 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 81 (68.6) | 33 (75.0) | 59 (70.2) | 81 (68.6) | X 2 y = 0.72; p = .868 |

| No | 37 (31.4) | 11 (25.0) | 25 (29.8) | 37 (31.4) |

3.2 Differences in demographic characteristics among the four groups

Except for age and marital status, no significant differences were found in any demographic characteristics among the four groups (see Table 1). LTRs who reported neither chronic pain nor psychological distress were younger than the LTRs with only chronic pain and younger than the LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress. LTRs with only chronic pain were significantly older than LTRs with only psychological distress. LTRs with only psychological distress were more often never married than LTRs with only chronic pain. In addition, LTRs with psychological distress were more likely to be never married than LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress.

3.3 Differences in childhood difficulties before the age of 16 among the four groups

As shown in Table 2, significant differences were found among the four groups on all of the items related to childhood difficulties before the age of 16, except the item on sexual abuse. LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress were more likely to have experienced economic problems in their childhood home; other types of abuse than sexual abuse; long-term bullying; and had more often dropped out of school than had LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress. LTRs with only psychological distress had more often experienced conflicted relationship between their parents than LTRs without both chronic pain and psychological distress. Finally, LTRs with psychological distress with or without chronic pain, had, before the age of 16, more often experienced having parents who abused alcohol and drugs, than LTRs with only chronic pain.

Differences in childhood difficulties before the age of 16 between long-term social assistance recipients (LTRs) with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress, LTRs with only chronic pain, LTRs with only psychological distress and LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress.

| Childhood difficulties before 16 years of age | LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress (0) N =119 (32%) | LTR with only chronic pain (1) N =44 (12%) | LTR with only psychological distress (2) N = 87 (24%) | LTR with chronic pain and psychological distress (3) N =119 (32%) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Economic problems in childhood home | ||||||

| Yes | 40 (35.1) | 17 (40.5) | 38 (46.3) | 102 (86.4) | X 2 = 8.23; p = .042 | |

| No | 74 (64.9) | 25 (59.5) | 44 (53.7) | 16 (13.6) | 0<3 | |

| Conflicted relationships between your parents | ||||||

| Yes | 55 (47.0) | 19 (46.3) | 58 (69.0) | 72 (64.3) | X 2 = 14.06; p = .003 | |

| No | 62 (53.0) | 22 (53.7) | 26 (31.0) | 40 (35.7) | 0<2 | |

| Parents alcohol and drug abuse | ||||||

| Yes | 33 (29.2) | 5 (12.2) | 30 (37.0) | 44 (39.6) | X 2 = 11.63; p = .009 | |

| No | 80 (70.8) | 36 (87.2) | 51 (63.0) | 67 (60.4) | 1 < 2,3 | |

| Sexual abuse | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (12.1) | 1 (2.4) | 16 (19.8) | 16 (14.4) | X 2 = 7.21; p = .065 | |

| No | 100 (87.7) | 40 (97.6) | 65 (80.2) | 95 (85.6) | ||

| Other types of abuse | ||||||

| Yes | 10 (8.8) | 5 (12.5) | 16 (19.8) | 37 (33.9) | X 2 = 23.59; p <.001 | |

| No | 103 (91.2) | 35 (87.5) | 65 (80.2) | 72 (66.1) | 0<3 | |

| Long term bullying | ||||||

| Yes | 24 (21.2) | 7 (17.1) | 26 (32.1) | 52 (45.6) | X 2 = 20.09; p<.001 | |

| No | 89 (78.8) | 34 (82.9) | 55 (67.9) | 62 (54.4) | 0<3; 1 <3 | |

| Dropped out of school | ||||||

| Yes | 27 (23.9) | 11 (26.8) | 36 (45.0) | 58 (51.3) | X 2 = 21.89; p<.001 | |

| No | 86 (76.1) | 30 (73.2) | 44 (55.0) | 55 (48.7) | 0< 2,3 | |

3.4 Differences in health and social characteristics among the four groups

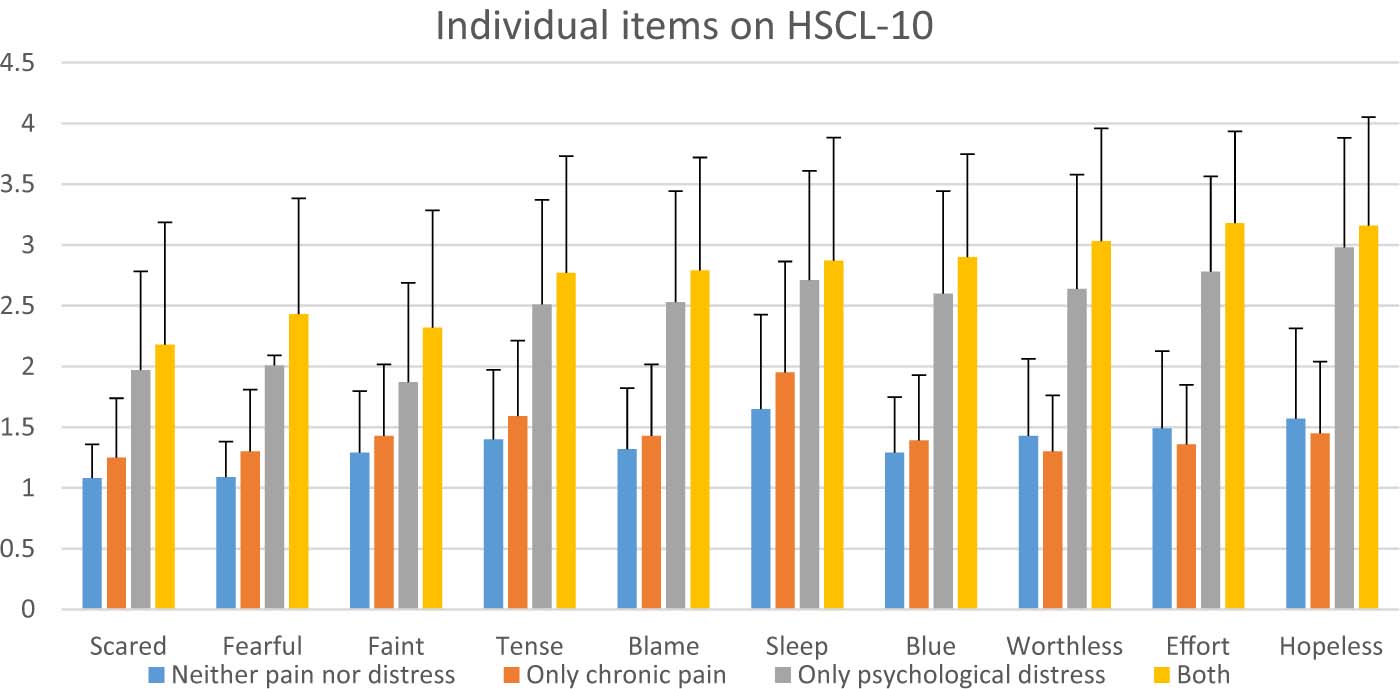

As shown in Table 3, significant differences were found in the occurrence of alcohol and substance use/illicit drug use when comparing LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress to LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress. LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress more often have problems with alcohol and substance/illicit drug use than do LTRs with only chronic pain. In addition, LTRs with psychological distress and LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress reported more feelings of loneliness than did LTRs with only chronic pain. Differences among the four groups on individual items on HSCL-10 are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Differences in health and social characteristics between long-term social assistance recipients (LTRs) with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress, LTRs with only chronic pain, LTRs with only psychological distress and LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress.

| Characteristics | LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress (0) N =119 (32%) | LTR with only chronic pain (1) N = 44 (12%) | LTR with only psychological distress (2) N = 87 (24%) | LTR with chronic pain and psychological (3) N =119 (32%) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Alcohol | ||||||

| Yes | 9 (7.7) | 3 (6.8) | 16 (18.4) | 30 (25.2) | X 2 =16.81; p = .001 | |

| No | 108 (92.3) | 41 (93.2) | 71 (81.6) | 89 (74.8) | 0<3; 1 <3 | |

| Substance/Illicit drug use | ||||||

| Yes | 10 (8.5) | 4 (9.1) | 40 (46.0) | 41 (34.5) | X 2 = 47.66; p <.001 | |

| No | 107 (91.5) | 40 (90.9) | 47 (54.0) | 78 (65.5) | 0< 2,3; 1 < 2,3 | |

| Life satisfaction | ||||||

| Satisfied | 60 (50.4) | 12 (27.3) | 7 (8.0) | 7 (6.0) | X 2 = 123.0; p <.001 | |

| Neither/nor | 52 (43.7) | 26 (59.1) | 39 (44.8) | 42 (36.2) | Satisfied; 0>2,3;1>3 | |

| Dissatisfied | 7 (5.9) | 6 (13.6) | 41 (47.1) | 67 (57.8) | Dissatisfied; 0<2,3; 1 <2,3 | |

| Feeling lonely | ||||||

| Often | 10 (8.5) | 8 (18.2) | 49 (57.6) | 64 (54.2) | X 2 = 90, 49; p<.001 | |

| Sometimes | 57 (48.3) | 17 (38.6) | 28 (32.9) | 38 (32.2) | Often; 0<2,3; 1<2,3 | |

| Seldom/never | 51 (43.2) | 19 (43.2) | 8 (9.4) | 16 (13.6) | Seldom/never; 0>2,3; 1 >2,3 | |

Differences in single it em and mean scores on the Hopkins Symptom Checklist between long-term social assistance recipients (LTRs, n = 369) with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress (n = 119), LTRs with only chronic pain (n = 44), LTRs with only psychological distress (n = 87) and LTR swith both chronicpa in and psychological distress (n = 119).All values are plotted as means ± standard deviation

3.5 Differences in life satisfaction and health-related quality of life among the four groups

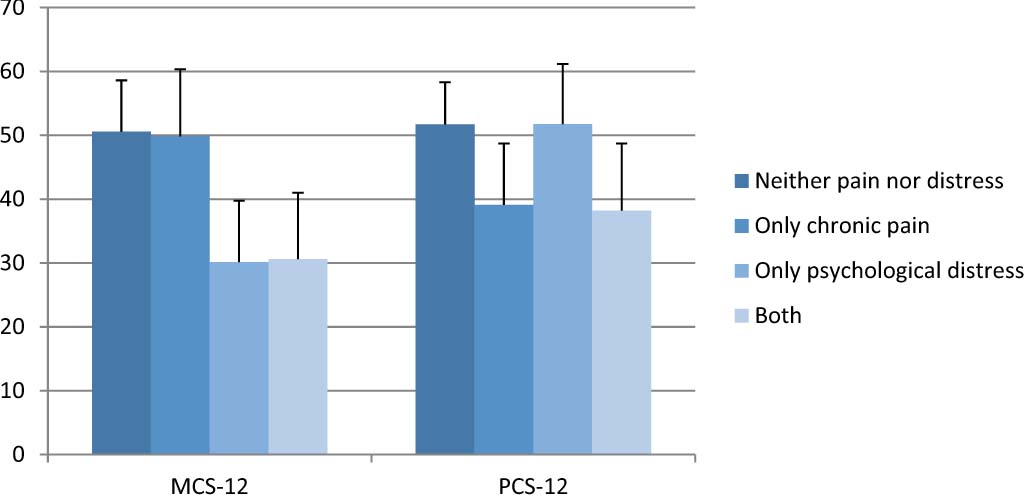

As shown in Table 3, LTRs with neither psychological distress nor chronic pain were more satisfied with their life than both the LTRs group with psychological distress only and the LTRs group with both chronic pain and psychological distress. LTRs in the chronic pain only group were less dissatisfied with their life than LTRs with psychological distress and LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress. As shown in 2, significant differences in PCS scores were found among the four groups. LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress reported significantly higher physical component summary scale (PCS) scores than LTRs with only chronic pain and LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress. LTRs with only chronic pain had a significantly higher mental component summary scale (MCS) scores than LTRs with only psychological distress and LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress.

Differences in physical component (PCS 12) and mental component (MCS 12) scores from the SF-12 between long-term social assistance recipients (LTRs, n = 320) with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress (n = 107), LTRs with only chronic pain (n = 41), LTRs with only psychological distress (n = 76) and LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress (n = 96). All values are plotted as means ± standard deviation.

4 Discussion

To my knowledge, this study is the first to determine the co-occurrence of chronic pain and psychological distress and to evaluate differences in demographic and social characteristics among LTRs, as well as health-related quality of life. In the present study, the overall occurrence of chronic pain alone, psychological distress alone, and both chronic pain and psychological distress in this sample of LTRs was 68%. This finding is consistent with previous reports that noted that a high percentage of LTRs struggle with relatively poor physical and mental health [8,34]. Previous research has also noted that health problems tend to be unequally distributed within populations, with the greatest burden being carried by the socially disadvantaged [35]. LTRs and welfare recipients have a higher rate of chronic pain and psychological distress than the general population and have more depressive symptoms, decreased psychological well-being, and are more likely to have mental problems than non-recipients [10, 36, 37]. A recent longitudinal study found that economic hardship, unemployment and living on social welfare were strong determinants of common mental disorders [6].

No significant differences were found among the four groups, in the majority of demographics characteristics. However, consistent with previous reports, the occurrence of chronic pain was associated with increased age [17,37, 38,39], and LTRs with only psychological distress more often had never been married than LTRs with only chronic pain, and LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress. This finding is consistent with previous research on marital status and mental health, which consistently shows that married people report better mental health than do those who are not married [40]. However, a potential reason for more often never having married, is perhaps being of a younger age.

Consistent with previous studies [4,41,42], LTRs in Norway have experienced numerous childhood difficulties. While a relatively high percentage of LTRs in all four groups reported that they had “experienced economic problems in childhood homes”, the highest occurrence rate was found among LTRs who reported having both chronic pain and psychological distress. This finding is consistent with a US study which found that poverty, low socioeconomic status, and parents receiving welfare assistance, were important early life course circumstances that increased the risk of experiencing depression, chronic pain, or both of these conditions in adulthood [43].Additional support for the relationship between increased childhood difficulties and poorer mental health as adults was found in a previous study on depressive symptoms over the life course. They have found that low household income, low economic status in early age, and having parents with low education are associated with higher occurrences of depression and anxiety in adulthood [44].

It is interesting to note that compared to LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress, a significantly higher percentage of LTRs in the only psychological distress group reported that they “experienced conflicted relationships between their parents”. This finding is consistent with previous work which found that an individual’s childhood conditions (e.g., low social support, small degree of control and coping in everyday life), and their relationships with family and friends (e.g. attachment insecurity) [45]. Previous studies have also shown that a variety of life events in young age (e.g., serious economic problems, chronic pain, hazardous alcohol use, gambling addiction, living below the poverty line), were all risk factors for mental health problems [45].

Another finding is that, compared to LTRs in the chronic pain only group, LTRs in both the psychological distress only group and the group with both chronic pain and psychological distress grew up with parents who abused alcohol and illicit drugs. In addition, significantly more LTRs in these two groups had dropped out of school before the age of 16. These findings suggest that both socio-economic background and critical life events increase the likelihood that an individual will receive social assistance [5]. In addition, previous research has found that exposure to parental addiction in childhood was associated with psychological distress into adulthood [46].

An important finding from our study is that significantly more LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress reported experiences of “long term bullying” and reported “other types of abuse”. This finding is consistent with a growing body of research that focuses on the association between childhood difficulties (e.g., bullying, psychical abuse, sexual abuse) and pain [47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52]. A recent meta-analysis confirms the association between having been bullied and having psychosomatic problems [53]. In addition, a review assessed evidence from longitudinal studies for childhood determinants of adult mental illness, found evidence that child abuse, especially child sexual abuse has powerful consequences (e.g., major psychiatric disorders, high risk life-styles, self-destructive and violent behaviors, problems with relationships) [54]. However, it is interesting to note that no significant differences were found regarding sexual abuse between the four groups in the present study. In this present study, LTRs, compared to the general population in Norway, reported lower prevalence rates for sexual abuse [55].

This study shows that LTRs with psychological distress only and LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress are more often feeling lonely than LTRs within the other two groups. However, these findings support the suggestion that loneliness affects an individual’s physical health and mortality, as well as that individual’s mental health and cognitive functioning [56].

LTRs in the psychological distress only group and in the group with both chronic pain and psychological distress were more dissatisfied with their lives than were LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress and LTRs with chronic pain only. This is consistent with a previous study, which had found depression to be a robust predictor of low health-related quality of life [57]. Both groups reported a very low mental component score (MCS) (MCS = 30.16 and 30.63, respectively). LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress have the same mean MCS score (MCS = 50.60) as is indicated by the normative data for the general population in Norway. Individuals in that same group (LTRs with neither chronic pain nor psychological distress) have a higher physical component summary score (PCS) than indicated by the normative data (PCS score = 50.3) [32]. The LTRs who reported chronic pain only and both chronic pain and psychological distress have a lower psychical score, (PCS = 39.11 and 38.22, respectively), which is lower than the normative data for patients with low back pain [33]. This finding confirms findings from earlier research, that chronic pain and mental health problems such as anxiety and depression are closely linked [58] to poor quality of life.

Some limitations of this present study need to be acknowledged. First, with the cross-sectional design we cannot assign a direction or causality to the association between socio-demographic factors, chronic pain and psychological distress in LTRs. We need to know more about causality and effects of various factors and how these factors impact individuals’ life courses. Another limitation is the use of retrospective self-report questions about childhood difficulties before the age of 16. It may be difficult to remember events from many years ago, and memory changing as the years pass. [59]. A third limitation of the present study is that, although the overall sample size of LTRs was relatively large, the distribution of the four groups resulted in there being relatively small sample sizes in the pain only group, and in the psychological distress only group. A fourth limitation may be that the prevalence rates of sexual abuse are underreported. This may occur because this study is based on self-reported data where some might suppress incidents of sexual abuse.

5 Conclusion and implications

Despite these limitations, findings from the present study suggest that the co-occurrence of chronic pain and psychological distress is common among LTRs. Although this study cannot assign a clear direction or causality to the association between social and demographic characteristics, and chronic pain and psychological distress, the findings when examining LTRs’ problems in childhood before the age of 16, indicated that incidents in early life create a probability of chronic pain and psychological distress in the adult life of the individuals. Findings from the present study may also indicate a close relationship between objective living conditions and subjective well-being, pain and health among LTRs.

Implications of this study are that future research should use life course studies and address whether having chronic pain and psychological distresses is a major or minor contributor to disability in LTRs.

Highlights

Long-term social assistance recipients (LTRs) and pain.

Chronic pain and psychological distress are associated with childhood difficulties.

Childhood difficulties increased pain and psychological distress in adult lives.

There is a relationship between pain, health and life satisfaction among LTRs.

LTRs with both chronic pain and psychological distress are often feeling lonely.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.02.005.

-

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Data Inspectorate and the National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities in Norway.

-

Sources of support: The research was funded by Oslo University College and by the Directorate for Health and Social Affairs Norway.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Professor Christina Miaskowski, University of California, San Francisco, Professor Tone Rust0en, University of Oslo, and Professor Espen Dahl, Oslo and Akershus University College for providing a lot of support when preparing this manuscript.

References

[1] NAV. LOV 2009-12-18 nr 131. Lov om sosiale tjenester i arbeids-og velferds-for valtningen. Oslo: Arbeids depertement et; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Herud E, Naper SO. Poverty and Living Conditions in Norway: Status 2012. Oslo: NAV; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Kann IK, Naper SO. Utviklingen i økonomisk sosialhjelp 2005-2011. Arbeid og velferd 2012;3:83–99.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Hyggen C. Livslop i velferdsstaten. Oslo: Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Lorentzen T, Dahl E, Harsløf I. Welfare risks in early adulthood: a longitudinal analysis of social assistance transitions in Norway. Int J Soc Welfare 2012;21:408–21.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Linander I, Hammarstrom A, Johansson K. Which socio-economic measures are associated with psychological distress for men and women? A cohort analysis. EurJ Public Health 2015;25:231–6.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Grebstad UB. Social assistance and living conditions in Norway. Oslo: Statistics Norway; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Vozoris N, Tarasuk VS. The health of Canadians on welfare. Can J Public Health 2004;95:115–20.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Marttila A, Johansson E, Whitehead M, Burstrom B. Living on social assistance with chronic illness: buffering and undermining features to well-being. BMC Public Health 2010;10:754.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Baigi A, Lindgren E, Starrin B, Bergh H. In the shadow of the welfare society ill-health and symptoms, psychological exposure and lifestyle habits among social security recipients: a national survey study. Biopsychosoc Med 2008;22: 1–7.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Enes AK. økonomiog levekar for ulike lavinntektsgrupper 2009. Oslo: Statistics Norway; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Naper SO. All-cause and cause-specific mortality of social assistance recipients in Norway: a register-based follow-up study. Scan J Public Health 2009;37:820–5.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Edmond S, Werneke MW, Hart DL. Association between centralization, depression, somatization, and disability among patients with nonspecific low back pain.J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010;40:801–10.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ramage-Morin PL, Gilmour H. Chronic pain at ages 12 to 44. Health Rep 2010;21:53–61.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Gerrits MM, Vogelzangs N, van Oppen P, van Marwijk HW, van der Horst H, Penninx BW. Impact of pain on the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Pain 2012;153:429–36.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Gerrits MM, van Oppen P, van Marwijk HW, Penninx BW, van der Horst HE. Pain and the onset of depressive and anxiety disorders. Pain 2014;155:53–9.Search in Google Scholar

[17] van Hecke O, Torrance N, Smith BH. Chronic pain epidemiology and its clinical relevance. BrJ Anaesth 2013;111:13–8.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Khlat M, Legleye S, Sermet C. Influencing report of common mental health problems among psychologically distressed adults. Community Ment Health J 2014;50:597–603.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Bonevski B, Regan T, Paul C, Baker AL, Bisquera A. Associations between alcohol, smoking, socioeconomic status and comorbidities: evidence from the 45 and up study. Drug Alcohol Rev 2014;33:169–76.Search in Google Scholar

[20] WHO. Mental health action plan 2013–2020. Retrieved Sept. 15 from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/action_plan/en/Search in Google Scholar

[21] Marmot M. Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. The Lancet 2007;370:1153–63.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Løyland B, Miaskowski C, Wahl AK, Rust0en T. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among long-term social assistance recipients compared to the general population in Norway. Clin J Pain 2010;26:624–30.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Løyland B, Miaskowski C, Dahl E, Paul SM, Rustøen T. Psychological distress and quality of life in long-term social assistance recipients compared to the Norwegian population. ScanJ Public Health 2011;39:303–11.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Løyland B, Miaskowski C, Paul S, Dahl E, Rustøen T. The relationship between chronic pain and health-related quality of life in long-term social assistance recipients in Norway. Qual Life Res 2010;19:1457–65.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Løyland B. Chronic pain, psychological distress, and health-related quality of life among long-term social assistance recipients in Norway. Oslo: Unipub; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Johannessen A, Lødemel I. Tiltaksforsøket: Mot en inkluderende arbeidslinje? Oslo: H0gskolen i Oslo; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Dahl E, van der Wel KA. A forske pa marginaliserte grupper. Fontene forskning 2009;1:54–64.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Strand BH, Dalgard OS, Tambs K, Rognerud M. Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: a comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36). Nord J Psychiatry 2003;57:113–8.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Friestad C, Skog Hansen IL. Levekarblant innsatte. Oslo: FAFO; 2004.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Thorsen K, Clausen S. Hvem erde ensomme? Oslo: Statistics Norway; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Ferrans C. Development of a quality of life index for cancer patients. Oncol Nurs Forum 1990;17:15–9.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, Bullinger M, Kaasa S, Leplege A, Prieto L, Sullivan M. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 health survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA project. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1171–8.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. Howto Score Version 2 of the SF-12® Health Survey. Lincoln: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Kaplan GA, Siefert K, Ranjit N, Raghunathan TE, Young EA, Tran D, Danziger S, Hudson S, Lynch JW, Tolman R. The health of poor women under welfare reform. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1252–8.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Blyth FM. The demography of chronic pain: an overview. In: Croft P, Blyth FM, van derWindt D, editors. Chronic Pain Epidemiology. From Aetiology to Public Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Caron J, Latimer E, Tousinant M. Predictors of psychological distress in low- income populations of Montreal. CanJ Public Health 2007;98:35–44.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Taylor MJ, Barusch AS. Personal, family, and multiple barriers of long-term welfare recipients. Soc Work 2004;49:175–83.Search in Google Scholar

[38] King MT, Stockler MR, Cella DF, Osoba D, Eton DT, Thompson J, Eisenstein AR. Meta-analysis provides evidence-based effect sizes for a cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire, the FACT-G.JClin Epidemiol 2010;63:270–81.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Rustoen T, Wahl AK, Hanestad BR, Lerdal A, Paul S, Miaskowski C. Age and the experience of chronic pain: differences in health and quality of life among younger, middle-aged, and older adults. Clin J Pain 2005;21:513–23.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Bulloch AG, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Patten SB. The relationship between major depression and marital disruption is bidirectional. Depress Anxiety 2009;26:1172–7.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Lorentzen T. Social Assistance Dynamics in Norway: A Sibling Study of Inter-generational Mobility. Bergen: Rokkansenteret; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[42] vanderWel KA, Dahl E, Lodemel I, Loyland B, NaperSO, Slagsvold M. Funksjon-sevne hos langtidsmottakere av sosialhjelp. Oslo: Høgskolen i Oslo; 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Goosby BJ. Early life course pathways of adult depression and chronic pain. J Health Soc Behav 2013;54:75–91.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Quesnel-Vallee A, Taylor M. Socioeconomic pathways to depressive symptoms in adulthood: evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:734–43.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Nes RB, Clech-Aas J. Psykisk helse i Norge. Oslo: Nasjonalt folkehelseinstitutt; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Langlois KA, Garner R. Trajectories of psychological distress among Canadian adults who experienced parental addiction in childhood. Health Rep 2013;24:14–21.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Al-Modallal H, Peden A, Anderson D. Impact of physical abuse on adulthood depressive symptoms among women. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2008;29:299–314.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Saastamoinen P, Laaksonen M, Leino-Arjas P, Lahelma E. Psychosocial risk factors of pain among employees. EurJ Pain 2009;13:102–8.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Sigurdardottir S, Halldorsdottir S, Bender SS. Consequences of childhood sexual abuse for health and well-being: gender similarities and differences. Scand J Public Health 2014;42:278–86.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Kaaria S, Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E, Leino-Arjas P. Risk factors of chronic neck pain: a prospective study among middle-aged employees. EurJ Pain 2012;16:911–20.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Kempke S, Luyten P, Claes S, Van Wambeke P, Bekaert P, Goossens L, Van Houdenhove B.The prevalence and impact of early childhood trauma in chronic fatigue syndrome.J Psychiatr Res 2013;47:664–9.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Voerman JS, Vogel I, de Waart F, Westendorp T, Timman R, Busschbach JJ, van de Looij-Jansen P, de Klerk C. Bullying, abuse and family conflict as risk factors forchronic pain among Dutch adolescents. EurJ Pain 2015. Epub ahead of print.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Gini G, Pozzoli T. Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: a metaanalysis. Pediatrics 2013;132:720–9.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Fryers T, Brugha T. Childhood determinants of adults psychiatric disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2013;9:1–50.Search in Google Scholar

[55] ThoresenS, Hjemdal OK. Voldog voldtekt i Norge. En nasjonal forekomststudie av vold i et livsløpsperspektiv. Oslo: Nasjonalt kunnskapsenter om vold og traumatiskstress; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: atheoretical andempirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 2010;40:218–27.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Joffe H, Chang Y, Dhaliwal S, Hess R, Thurston R, Gold E, Matthews KA, BrombergerJT. Lifetime history of depression and anxiety disorders as a predictor of quality of life in midlife women in the absence ofcurrent illness episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:484–92.Search in Google Scholar

[58] WahlAK, Rustøen T, Rokne B, LerdalA, Knudsenø, MiaskowskiC, MoumT.The complexity of the relationship between chronic pain and quality of life: a study of the general Norwegian population. Qual Life Res 2009;18:971–80.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Mowbray CT, Yoshihama M. The Handbook of Social Work Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2001.Search in Google Scholar

© 2015 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- Psychophysiological effects of threatening a rubber hand that is perceptually embodied in healthy human subjects

- Original experimental

- A preliminary investigation into psychophysiological effects of threatening a perceptually embodied rubber hand in healthy human participants

- Editorial comment

- Analysis of C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in pain patients – Can biomarker studies lead to better understanding of the pathophysiology of pain?

- Clinical pain research

- Serum C-reactive protein levels predict regional brain responses to noxious cold stimulation of the hand in chronic whiplash associated disorders

- Editorial comment

- Importance of early diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS-1 and CRPS-2): Delayed diagnosis of CRPS is a major problem

- Clinical pain research

- Delayed diagnosis and worsening of pain following orthopedic surgery in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Editorial comment

- Associative learning mechanisms may trigger increased burden of chronic pain; unlearning and extinguishing learned maladaptive responses should help chronic pain patients

- Original experimental

- When touch predicts pain: predictive tactile cues modulate perceived intensity of painful stimulation independent of expectancy

- Editorial comment

- Low back pain among nurses: Common cause of lost days at work and contributing to the worldwide shortage of nurses

- Observational study

- Pain-related factors associated with lost work days in nurses with low back pain: A cross-sectional study

- Editorial comment

- Assessment of persistent pelvic pain after hysterectomy: Neuropathic or nociceptive?

- Clinical pain research

- Characterization of persistent pain after hysterectomy based on gynaecological and sensory examination

- Editorial comment

- Transmucosal fentanyl for severe cancer pain: Nasal mucosa superior to oral mucosa?

- Original experimental

- Facilitation of accurate and effective radiation therapy using fentanyl pectin nasal spray (FPNS) to reduce incidental breakthrough pain due to procedure positioning

- Editorial comment

- Why do we have opioid-receptors in peripheral tissues? Not for relief of pain by opioids

- Clinical pain research

- Peripheral morphine reduces acute pain in inflamed tissue after third molar extraction: A double-blind, randomized, active-controlled clinical trial

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain and psychological distress among long-term social assistance recipients – An intolerable burden on those on the lowest steps of the socioeconomic ladder

- Clinical pain research

- The co-occurrence of chronic pain and psychological distress and its associations with salient socio-demographic characteristics among long-term social assistance recipients in Norway

- Editorial comment

- Fifty years on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain-intensity is still good for acute pain. But multidimensional assessment is needed for chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Patient reported outcome measures of pain intensity: Do they tell us what we need to know?

- Editorial comment

- Postoperative pain documentation 30 years after

- Topical review

- Postoperative pain documentation in a hospital setting: A topical review

- Editorial comment

- Aspects of pain attitudes and pain beliefs in children: Clinical importance and validity

- Observational study

- The Survey of Pain Attitudes: A revised version of its pediatric form

- Editorial comment

- The role of social anxiety in chronic pain and the return-to-work process

- Clinical pain research

- Social Anxiety, Pain Catastrophizing and Return-To-Work Self-Efficacy in chronic pain: a cross-sectional study

- Editorial comment

- Advances in understanding and treatment of opioid-induced-bowel-dysfunction, opioid-induced-constipation in particular Nordic recommendations based on multi-specialist input

- Topical review

- Definition, diagnosis and treatment strategies for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction–Recommendations of the Nordic Working Group

- Observational study

- Opioid-induced constipation, use of laxatives, and health-related quality of life

- Editorial comment

- Migraine headache and bipolar disorders: Common comorbidities

- Systematic review

- Migraine headache and bipolar disorder comorbidity: A systematic review of the literature and clinical implications

- Editorial comment

- The role of catastrophizing in the pain–depression relationship

- Clinical pain research

- The mediating role of catastrophizing in the relationship between pain intensity and depressed mood in older adults with persistent pain: A longitudinal analysis

- Announcement

- May 26-27, 2016 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain, Reykjavik, Iceland May 25, 2016 PhD course

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- Psychophysiological effects of threatening a rubber hand that is perceptually embodied in healthy human subjects

- Original experimental

- A preliminary investigation into psychophysiological effects of threatening a perceptually embodied rubber hand in healthy human participants

- Editorial comment

- Analysis of C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in pain patients – Can biomarker studies lead to better understanding of the pathophysiology of pain?

- Clinical pain research

- Serum C-reactive protein levels predict regional brain responses to noxious cold stimulation of the hand in chronic whiplash associated disorders

- Editorial comment

- Importance of early diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS-1 and CRPS-2): Delayed diagnosis of CRPS is a major problem

- Clinical pain research

- Delayed diagnosis and worsening of pain following orthopedic surgery in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Editorial comment

- Associative learning mechanisms may trigger increased burden of chronic pain; unlearning and extinguishing learned maladaptive responses should help chronic pain patients

- Original experimental

- When touch predicts pain: predictive tactile cues modulate perceived intensity of painful stimulation independent of expectancy

- Editorial comment

- Low back pain among nurses: Common cause of lost days at work and contributing to the worldwide shortage of nurses

- Observational study

- Pain-related factors associated with lost work days in nurses with low back pain: A cross-sectional study

- Editorial comment

- Assessment of persistent pelvic pain after hysterectomy: Neuropathic or nociceptive?

- Clinical pain research

- Characterization of persistent pain after hysterectomy based on gynaecological and sensory examination

- Editorial comment

- Transmucosal fentanyl for severe cancer pain: Nasal mucosa superior to oral mucosa?

- Original experimental

- Facilitation of accurate and effective radiation therapy using fentanyl pectin nasal spray (FPNS) to reduce incidental breakthrough pain due to procedure positioning

- Editorial comment

- Why do we have opioid-receptors in peripheral tissues? Not for relief of pain by opioids

- Clinical pain research

- Peripheral morphine reduces acute pain in inflamed tissue after third molar extraction: A double-blind, randomized, active-controlled clinical trial

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain and psychological distress among long-term social assistance recipients – An intolerable burden on those on the lowest steps of the socioeconomic ladder

- Clinical pain research

- The co-occurrence of chronic pain and psychological distress and its associations with salient socio-demographic characteristics among long-term social assistance recipients in Norway

- Editorial comment

- Fifty years on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain-intensity is still good for acute pain. But multidimensional assessment is needed for chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Patient reported outcome measures of pain intensity: Do they tell us what we need to know?

- Editorial comment

- Postoperative pain documentation 30 years after

- Topical review

- Postoperative pain documentation in a hospital setting: A topical review

- Editorial comment

- Aspects of pain attitudes and pain beliefs in children: Clinical importance and validity

- Observational study

- The Survey of Pain Attitudes: A revised version of its pediatric form

- Editorial comment

- The role of social anxiety in chronic pain and the return-to-work process

- Clinical pain research

- Social Anxiety, Pain Catastrophizing and Return-To-Work Self-Efficacy in chronic pain: a cross-sectional study

- Editorial comment

- Advances in understanding and treatment of opioid-induced-bowel-dysfunction, opioid-induced-constipation in particular Nordic recommendations based on multi-specialist input

- Topical review

- Definition, diagnosis and treatment strategies for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction–Recommendations of the Nordic Working Group

- Observational study

- Opioid-induced constipation, use of laxatives, and health-related quality of life

- Editorial comment

- Migraine headache and bipolar disorders: Common comorbidities

- Systematic review

- Migraine headache and bipolar disorder comorbidity: A systematic review of the literature and clinical implications

- Editorial comment

- The role of catastrophizing in the pain–depression relationship

- Clinical pain research

- The mediating role of catastrophizing in the relationship between pain intensity and depressed mood in older adults with persistent pain: A longitudinal analysis

- Announcement

- May 26-27, 2016 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain, Reykjavik, Iceland May 25, 2016 PhD course