Abstract

Background and aims

Previous studies have shown that pelvic pain is common after hysterectomy. It is stated that only a minor part of that pain can be defined as persistent postsurgical pain. Our primary aim was to find out if the pelvic pain after hysterectomy may be classified as postsurgical. Secondary aims were to characterize the nature of the pain and its consequences on the health related quality of life.

Methods

We contacted the 56 women, who had reported having persistent pelvic pain six months after hysterectomy in a previously sent questionnaire. Sixteen women participated. Clinical examinations included gynaecological examination and clinical sensory testing. Patients also filled in quality of life (SF-36) and pain questionnaires.

Results

Ten out of sixteen patients still had pain at the time of examination. In nine patients, pain was regarded as persistent postsurgical pain and assessed probable neuropathic for five patients. There were declines in all scales of the SF-36 compared with the Finnish female population cohort.

Conclusions

In this study persistent pelvic pain after vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy could be defined as persistent postsurgical pain in most cases and it was neuropathic in five out of nine patients. Pain had consequences on the health related quality of life.

Implications

Because persistent postsurgical pain seems to be the main cause of pelvic pain after hysterectomy, the decision of surgery has to be considered carefully. The management of posthysterectomy pain should be based on the nature of pain and the possibility of neuropathic pain should be taken into account at an early postoperative stage.

1 Introduction

The prevalence of chronic pelvic pain is estimated to be 3.8% in primary health care female patients [1]. Hysterectomy is one of the most frequent surgical operations on women for benign causes [2] and previous studies have shown that persistent pain is common after hysterectomy. However, the prevalence varies significantly in these studies, ranging from 5% to 50% [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Persistent postsurgical pain (PPSP) is pain that is not a continuum of preoperative pain, continues for longer than two months and cannot be explained by any other aetiology except surgery [9]. Pain is one of the symptoms leading to the decision of hysterectomy. Due to the differences in pain assessment and lack of clinical examinations in previous studies it remains unclear how big a proportion of the pelvic pain can be defined as PPSP [5, 6, 10]. The aetiology of PPSP has traditionally been considered neuropathic [11,12]. However, it is known that nerve damage is not essential. Peripheral inflammation can affect the central nervous system and contribute to persistent pain [13]. It is also shown that postsurgical neuropathies can be solely inflammatory and there is no need for mechanical trauma [14].

There are clear inconsistencies in the definition of neuropathic pain, which makes the classification of pain difficult [15]. According the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) neuropathic pain is pain arising as a direct consequence of a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system [16]. A clinical examination is the only way to reliably assess the nature of persistent postsurgical pain and to exclude other causes of pain.

Health related quality of life (HRQoL) has recently been on the focus in comparing different methods of hysterectomy. The method of surgery does not have an impact on the HRQoL [17,18]. Lang et al. have studied the HRQoL in middle-aged women and found that the more conditions the women have, the lower the HRQoL is, with each condition lowering the score [19].

We designed a prospective, observational study with clinical analysis of pain. Our primary aim was to find out the proportion of PPSP in women who suffer from persistent pelvic pain after laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy. Our secondary aims were to clarify the characteristics of pain and to assess patients’ HRQoL.

2 Methods

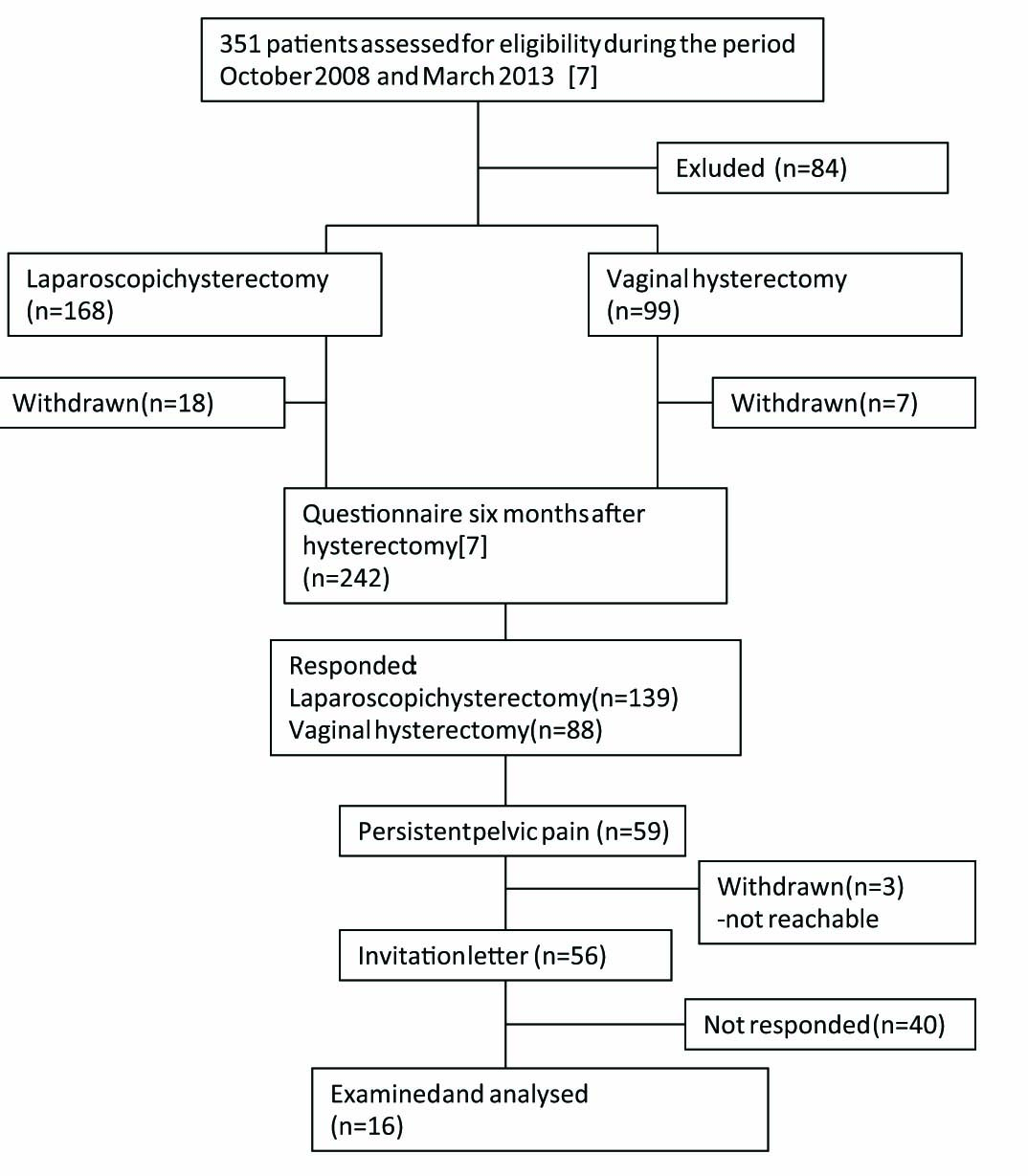

The study was carried out during the period of May 2012 and November 2013. An invitation letter was sent to patients (n = 56) who previously had reported presence of persistent pelvic pain six months after surgery. All 56 patients had participated to the follow-up study of persistent pelvic pain after vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy aiming to find out prevalence and predictors of persistent pain [7]. In that study the prevalence of persistent pelvic was 26%. Patients willing to participate in the study were asked to book an appointment. Written informed consent was obtained from 16 Finnish speaking women, who had undergone laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy for non-malignant conditions at Tampere University Hospital or Valkeakoski Regional Hospital carried out between October 2008 and March 2013 (Fig. 1). The study design was approved by the local Ethics Committee, Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Tampere, Finland, number R11190, approval date 21 February 2012 and registered with Clinical Trials (NCT01706549).

Flowchart of the patients.

2.1 Examination

Clinical examinations included gynaecological examination by a gynaecologist (author K.N) and clinical sensory testing by an anaesthesiologist specialized in pain medicine (author M-L.K) and were performed in a lithotomy position. The examinations were performed during the same appointment and in the same order.

Gynaecological examination: Vulvar area was inspected and palpated. Vagina was examined first with a Sim’s speculum and palpation in rest and then inspected and palpated during Valsalva manoeuvre. Pelvic area was palpated bimanually to detect scarring and mobility of the vaginal vault, adhesions or painful areas. All patients underwent transvaginal ultrasound.

Sensory examination: Patients were asked to keep eyes closed or look at the ceiling, following their preference. The examination started with Abeta-fibre sensory testing with a cotton stick. A light touch with the cotton stick was applied to the skin from above the umbilicus towards the groin, starting laterally and proceeding medially with 3 cm light swipes sequentially. In the thigh region similar sequential swipes were performed from upper lateral to lower medial part of the thigh. Then the examination proceeded to the vulvar and perineal region. In a similar manner, C-fibres and Adelta fibres were tested with warm (±40 °C) and cold (±25 °C) metallic strollers, rolling with the force of the weight of the stroller, slowly on the skin (Somedic, Hörnby, Sweden) and cocktail sticks (pin prick) with 2–3 cm intervals with the forefinger of the examiner on the other end of the cocktail stick in order to have some control on the force of the pressure applied. The patients were asked to compare sides, or when both altered, to another nearby skin area, and rate the change on the numerical rating scale (NRS) (0–10). Presence of allodynia and/or temporal and/or spatial summation was asked verbally. The results were drawn and written on a separate chart.

2.2 Questionnaires

The participants filled in the pain and SF-36 questionnaires after the appointment and they were asked to drop the filled questionnaire into an indicated box before leaving the hospital. The pain questionnaire was the same, which they had completed also at time point six months after hysterectomy [7]. Patients were asked if they still had persistent pelvic pain. Those patients who had persistent pelvic pain were asked to answer the questions concerning frequency, location, character and intensity of pain, the interference of pain with sleeping and daily activities, and management of pain. All patients were asked about other pain problems than pelvic pain and their working status. They were also asked to fill in SF-36 which is a 36-item generic health status measure [20]. The SF-36 assesses eight scales concerning physical functioning, role physical, role emotional, vitality, mental health, social functioning, bodily pain and general health.

2.3 Neuropathic pain probability

Because neuropathic pain is not a single disease but a syndrome with specific symptoms and signs, the probability of neuropathic pain is assessed by a neurological history and an examination. The examination includes sensory testing, definition of neural area as in Apte et al. [21]. In this study we used a grading system published previously by European Federation of Neurological Societies [15,22].This grading system is based on the history of pain, the clinical sensory examination (touch/vibration, cold, warmth and pain sensibility) and the diagnostic tests e.g. skin biopsy. In the current study pain was classified as possible neuropathic pain, if pain was located in the surgical or corresponding area and character of pain fulfilled neuropathic criteria (history of pain). Pain was classified as probable neuropathic pain if the clinical sensory testing showed the presence of sensory disturbances in addition to the positive history of pain. Because we used no specific diagnostic test, no definite neuropathic pain was categorized.

2.4 Statistics

Results are shown as median or mean with SD. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSSTM, Windows version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3 Results

Sixteen women participated in the study and underwent both gynaecological and sensory examination. The participation rate was 29%. The time from surgery to examination ranged from 10 to 44 months (median 30). The mean age was 51 (SD 6.6), range 41-69 years. Characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1.

Patients characteristics and paindata

| Number | Age (years) | Time to examination (months) | Type of surgery | Indication of surgery | Complication | Smoking | Preoperative pain R/M (NRS) | Pain at the appointment | PPSP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 47 | 12 | LH + SO | Menstrual disorders | No | No | 8/8 | Yes | No |

| 2 | 45 | 32 | VH | Uterine leiomyoma | No | Yes | 2/0 | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | 55 | 32 | VH | Cervical dysplasia | No | Yes | 0/0 | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | 5G | 33 | VH | Uterine leiomyoma | No | No | N/A | No | No |

| 5 | 55 | 25 | LH + SO | Uterine leiomyoma | Ureter injury | No | 0/0 | Yes | Yes |

| G | 50 | 10 | LH + SO | Uterine leiomyoma | No | No | 0/0 | Yes | Yes |

| l | 49 | 11 | LH + SO | Uterine leiomyoma | Urinary bladder injury | Yes | 4/G | Yes | Yes |

| S | 50 | 22 | LH + SO | Cervical dysplasia | No | No | 0/0 | No | No |

| 9 | 4l | 30 | LH | Uterine leiomyoma | No | No | 3/S | No | No |

| 10 | 4S | 23 | LH | Menstrual disorders | No | Yes | G/G | No | No |

| 11 | 5l | 2G | LH | Cervical dysplasia | No | Yes | 0/0 | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | 5S | 30 | LH + SO | Uterine leiomyoma | No | No | 2/2 | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | G9 | 35 | LH | Endometrial hyperplasia | Hematoma, infection | No | 0/0 | No | No |

| 14 | 41 | 39 | LH | Endometrial hyperplasia | No | No | 0/0 | No | No |

| 15 | 51 | 39 | LH + SO | Uterine leiomyoma | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| 1G | 4l | 44 | LH | Uterine leiomyoma | No | No | N/A | Yes | Yes |

VH, vaginal hysterectomy; LH, laparoscopic hysterectomy; SO, salpingo-oophorectomy; R/M, atrest/on moving; NRS, numerical ratingscale O-lO; PPSP, persistent postsurgical pain; N/A, not available

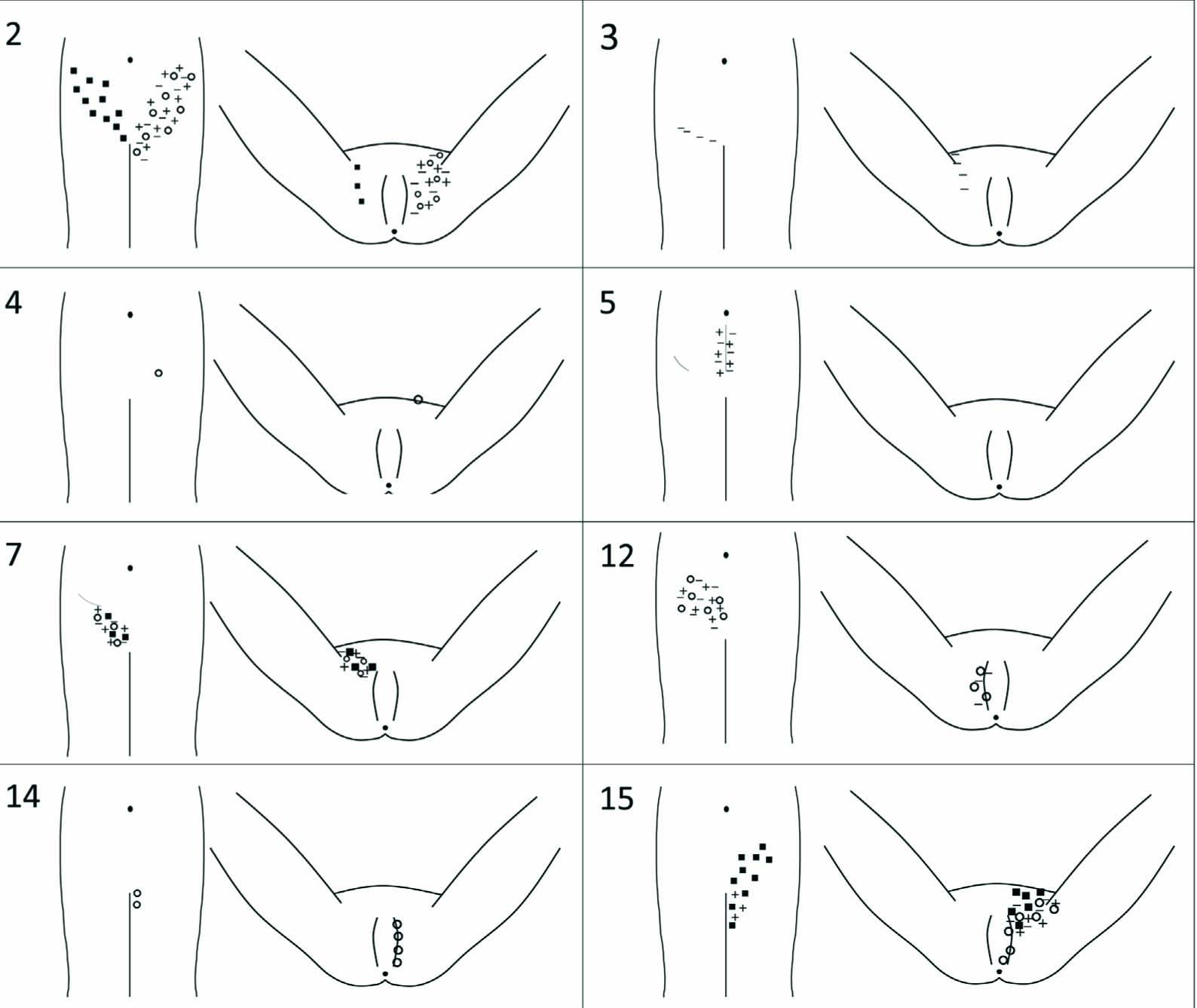

3.1 Pain

Ten patients out of sixteen still had persistent pelvic pain. One of those ten patients had pain in the vagina only occasionally. This was regarded as pelvic pain but not PPSP. Pain for nine out of ten patients was regarded as PPSP, hence we did not find any other reason for persistent pelvic pain than the postoperative state. The only findings of gynaecological examination were an atrophic, dry vagina in two patients but that was not regarded as a cause of pelvic pain. Eight out of sixteen patients had sensory signs, and two of them without persistent pelvic pain. The sensory dysfunction was most often hyperesthesia located in the sensory area of iliohypogastric nerve (five out of eight) but also in the sensory area of genitofemoral (four out of eight), ilioinguinal (three out of eight), genital branch and scar. Fig. 2 illustrates the findings of the sensory examination and the results are specified according to affected nerve and NRS rating of the sensory dysfunction in Table 3.

Drawings showing the sensory changes in eight patients. + corresponds forwarm, – for cold, both examined with the thermal roller. Black square □ stands fortouch (cotton stick) and open circle ⵔ for pin prick (wooden stick). The numbers in the left corner correspond to the patient id of this study.

Fifteen patients filled in the pain questionnaire. One out of these fifteen did not fill in the questionnaire properly and the rating of the intensity of pain was lacking. One patient did not fill in the pain questionnaire although she reported persistent pelvic pain in the clinical examination. According to the questionnaires the intensity of pain was mild for one patient, moderate for five patients and severe for one patient during the past week before the clinical examination. One patient reported that her pain occurs less than once a week and had no pain during the past week. Six patients had no more pain.

According to the pain questionnaire and the clinical examination we considered that nine patients had PPSP and determined the neuropathic pain as possible for three patients, probable for five patients and unlikely for one patient. The characteristics of pain are shown in Table 2 and the findings of sensory testing in Fig. 2 and Table 3.

Characteristics of persistent pelvic pain.

| Patient number | Location of pain | Description | When | Current pain (NRS) | Pain during the past week (NRS) | Pain at its worst during the past week (NRS) | Interfere with sleep | Interfere with daily activities (NRS) | Neuropathic pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ≠ | In the vagina | Ache, burning sensation | Occurs less than once a week | 2 | 7 | 7 | No | 5 | Possible |

| 2 | In the middle ofthe lower abdomen | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Probable |

| 3 | In the middle ofthe lower abdomen | Burning sensation | Occurs less than once a week | 0 | 5 | 5 | No | 0 | Probable |

| 5 | Pain when urinating | Tenderness | Daily bouts of pain | 4 | 4 | 6 | No | 1 | Possible |

| 6 | On the right side of the lower abdomen | Tenderness | Occurs less than once a week | 5 | 5 | 5 | No | 2 | Possible |

| 7 | In the middle ofthe lower abdomen | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Probable |

| 11 | In the middle ofthe lower abdomen | Ache | Occurs less than once a week | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | 0 | Unlikely |

| 12 | In the groin, in the lower back, on the right side of the lower abdomen | Tenderness, dull | Incessant, constant | 4 | 4 | 5 | No | 4 | Probable |

| 15[*] | In the lower back, around the scar, on the right side of the lower abdomen | Ache, twinge | Daily bouts of pain | 5[*] | 5[*] | 7 | Yes[*] | 9[*] | Probable |

| 1G | On the right side of the lower abdomen | Tenderness | Weekly bouts of pain, but not daily | 2 | 2 | 1 | Yes | 0 | Possible |

NRS (numerical rating scale 0–10), ≠ Patient numberl: no PPSP

Sensory findings by anatomical distribution [21] and magnitude of sensory dysfunction by modulation on a NRS. + for hyperesthesia and - for hypoesthesia.

| Patient id | Area or nerve (s) | Warm | Cold | Touch | Pin prick | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Ilioinguinal | +4 l.sin | +4 l.sin | +5 l.dx | +3 l.sin | |

| Iliohypogastric | +4 l.sin | +4 l.sin | +5 l.dx | +3 l.sin | ||

| Genitofemoral | +4 l.sin | +4 l.sin | - | +3 l.sin | ||

| 3 | Ilioinguinal | - | -8 l.dx | - | - | |

| 4 | Iliohypogastric | - | - | - | +3 l.sin | AllodyniaTemporal and spatial summation |

| 5 | Scar | -5 l.a | - | +5 | ||

| l | Iliohypogastric | +3 l.dx | +3 l.dx | +3 l.dx | +3 l.dx | Temporal summation |

| 12 | Iliohypogastric | -2 l.dx | +l l.dx | - | +3 l.dx | |

| GenitofemoralGenital branch | - | +5 l.dx | - | +1 l.dx | ||

| 14 | GenitofemoralGenital branch | - | - | - | +S l.sin | Allodynia |

| 15 | Ilioinguinal | -S l.sin | +S l.sin | -S l.sin | +S l.sin | |

| Iliohypogastric | - | - | +3 l.sin | - | ||

| Genitofemoral | - | +G l.sin | +3 l.sin | +G l.sin |

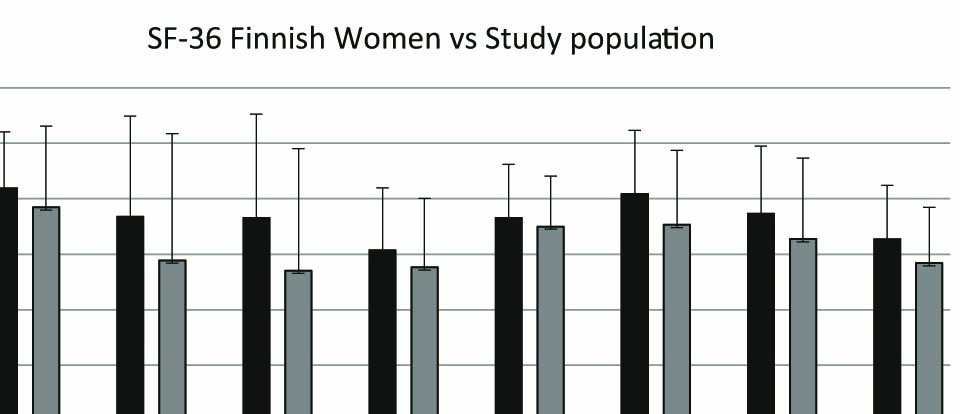

3.2 Health related quality of life

All sixteen patients filled in the SF-36. The mean scores of the patients involved in this study were compared with the mean scores of Finnish female cohort (n = 1133) [23]. There were lower scores in all scales. Because of the small number of study patients, we did not regard a statistical analysis relevant (Fig. 3).

Histogram showing quality of life in Study population (Sp) in comparison to Finnish Women (FW). PhFu = Physical Functioning, RoPh = Role Physical, RoEm = Role Emotional, Vit = Vitality, MeHe = Mental Health, SoFu = Social Functioning, BoP = Bodily Pain, and GeHe = General Health.

4 Discussion

The results of this descriptive study showed that the major part of chronic pelvic pain after vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy can be regarded as persistent postsurgical pain. Yet, the characteristics of PPSP varied. Our study also indicated that the persistent pelvic pain has an impact on patients’ HRQoL.

It has been suggested that the surgery itself would have only minor impact on the persistent pelvic pain after hysterectomy. A study of ninety women who underwent hysterectomy reported that out of the fifteen patients who suffered from persistent pelvic pain four months after surgery, only four had PPSP. Persistent post- surgical pain was defined as a pain that affected daily living and was classified as newly acquired pain [10]. The study of persistent pain after elective gynaecologic surgery of 433 women found 14% incidence of PPSP. In that study PPSP was defined as a pain that the patient believed to be related to the previous surgery. The overall prevalence of pain was 35% six months after surgery [6]. The recent prospective multicentre study of different kind of surgeries reported 11.8% incidence of PPSP after vaginal and 25.1% after abdominal hysterectomy. The definition ofPPSP based on BriefPain Inventory and clinical sensory testing four months after surgery [8]. In our cohort nine out of ten women with pain were assessed to have PPSP despite that three of them had reported preoperative pelvic pain. Their preoperative pain was linked with menstrual bleeding and uterine leiomyomas and the persistent pain after surgery was not regarded as a continuum of this preoperative pain. The method of determining the PPSP after hysterectomy may account for the discrepancy between results. Our study confirms the significance of the clinical analysis of pain.

In the current study, the prevalence of probable neuropathic pain was five out of nine patients (56%) among patients with PPSP assessed according to the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) guidelines. This is within the limits of the results of a multicentre questionnaire survey with a six months prospective follow-up using the Douleur Neuropathique 4 Questions (DN4) [24]. According to that study 43.3% of the patients who reported PSPP had neuropathic pain, although the percentage ranged widely after various types of surgery. Among the patients who had undergone laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair the esti-mate for a neuropathic PSPP was 6%, open inguinal hernia repair 43% and caesarean section 61%. In a recently published systematic literature review the results were similar. The assessed prevalence of neuropathic pain among patients with PPSP was 52-66% after thoracic surgery, 68-74% after breast surgery, 31-45% after hernia surgery and 6-9% after total hip and knee arthroplasty [15]. The large multicentre study including vaginal and abdominal hysterectomies found that only 24% of patients with PPSP had neuropathic pain after vaginal hysterectomy and 44% after abdominal hysterectomy assessed by DN4 [8]. In our study two women of nine PPSP patients had undergone vaginal hysterectomy while in seven cases laparoscopic hysterectomies were performed. Sensory changes were seen equally after vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy. It is proposed that different combinations of mechanisms may cause the persistent pain after laparoscopic groin hernia repair [25]. Although patients frequently have sensory disturbances after inguinal herniotomy [26,27] these are not necessarily due to intraoperative nerve damage. Central sensitization due to peripheral inflammation may also account for the sensory dysfunction [15,28]. It is conceivable that this kind of mixed pathogenic mechanism is also involved in the development of persistent pain after hysterectomy.

It is known from earlier studies that the persistent postsurgical pain attenuates in time [24, 29, 30]. In our study, six patients out of sixteen were painless although they had reported having pain six months after hysterectomy. The time from surgery to examination ranged from 12 to 39 months (median 26.5) for these six patients.

Two patients with persistent pain had surgical complications, one ureter injury and one urinary bladder injury. These severe complications are rare, incidence 0.3–1.2% after laparoscopic hysterectomy [31,32]. For these two patients the complication may explain persistent pain. Another patient had severe pelvic pain and this pain was not regarded as PPSP; i.e. ache and burning sensation in the vagina.The cohort study of 2397 patients by Duale et al. found that intensity of pain was severe if the pain was neuropathic [24]. We did not find any association between probability of neuropathic pain and severity of pain but this can be explained by a small sample size. One patient who rated her pain moderate informed that her worst pain problem was back pain. It is shown earlier that comorbid chronic pain is associated with the intensity of PPSP [33]. Our results of SF-36 are consistent with the previous studies of PPSP and quality of life [34,35]. We found lower scores in all assessed scales compared with the Finnish female cohort although not all of the women examined had pelvic pain anymore. However, all sixteen women had reported to suffer persistent pelvic pain six months after hysterectomy.

The main limitation of the study is the low participation rate. The reason for the unwillingness to be involved in the study remains unknown. One explanation can be that the patients’ persistent pain had disappeared and they thus found an option for another medical examination unnecessary. Attenuation of PPSP has been shown in a cohort of inguinal hernia patients [36]. The second limitation is that two of ten patients who suffered persistent pelvic pain did not fill in the pain questionnaire and these patients’ data of the characteristic of pain were collected only from clinical examination records. Third, the time for clinical examination ranged being 10ȁ44 months after surgery. The same time frame would have given us more reliable data to compare patients. It would be of relevance to plan a prospective study of persistent postsurgical pain with an objective on the time course of such a pain. Furthermore we did not ask the patients to fill in the SF-36 questionnaire pre- operatively; therefore we were unable to compare the pre- and postoperative scores of SF-36 which would have been more informative. It is also noteworthy that clinical examination always has limitations in terms of the estimation of the origin of pain; e.g. is it whether musculoskeletal or gynaecological. Using a Vaginal Pressure-Pain Threshold-measurement by a specifically designed device [37] might have brought some additional value to our sensory testing. However, we did not regard this as a necessary part of this rather a pragmatic approach. The vaginal algometer has thus far been used in only one study [4], where researchers could in fact show a moderate correlation of persistent postoperative pelvic pain and pressure detection threshold. Further studies with such a device are warranted before it will be included as a part of clinical gynaecological examination. All and all, the sensory examination used in this study relies on subjective measures, as the measure of pain is always subjective and may be influenced by the state of mind, environment, and interaction between the examiner and the subject. In our study, the clinical gynaecological examination and the sensory testing were always performed by the same authors (KN and MLK, respectively), which is a strength and during the same session, when both of the examiners were present. We thus sought to alleviate the possible unintentional negative chemistry occurring between only two individuals.

5 Conclusions

In this study persistent pelvic pain after vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy could be defined as PPSP in most cases. The nature of persistent post-hysterectomy pain followed the characteristics of other types of PPSP being probable neuropathic for five out of nine patients. Pain had an impact on the patients’ health related quality of life.

Highlights

Persistent pelvic pain after hysterectomy can be defined as persistent postsurgical pain – PPSP – in most cases.

The nature of PPSP is probable neuropathic on more than half of these patients.

Pain has an impact on the patients’ health related quality of life.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.01.006.

-

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank doctors Sanna Hoppu and Antti Aho for their constructive comments on the text during the preparation of the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship: Dr. Maija-Liisa Kalliomaki has received an 8 month research working grant from The Finnish Medical Foundation (from February 2014).

References

[1] Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999:106: 1149-552.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, Morrow B, Podgornik MN, Brett KM, Marchbanks PA. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008:198,34.e1,34.e7.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Brandsborg B, Nikolajsen L, Kehlet H, Jensen TS. Chronic pain after hysterectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008:52:327-31.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Brandsborg B, Dueholm M, Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Nikolajsen L. Mechanosensi- tivity before and after hysterectomy: a prospective study on the prediction of acute and chronic postoperative pain. BrJ Anaesth 2011:107:940-7.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Pinto PR, McIntyre T, Noqueira-Silva C, Almeida A, Araujo-Soares V. Risk factors for persistent postsurgical pain in women undergoing hysterectomy due to benign causes: a prospective predictive study. J Pain 2012:13:1045-57.Search in Google Scholar

[6] VanDenKerkhof EG, Hopman WM, Goldstein DH, Wilson RA, Towheed TE, Lam M, Harrison MB, Reitsma ML, Johnston SL, Medd JD, Gilron I. Impact of perioperative pain intensity, pain qualities, and opioid use on chronic pain after surgery: a prospective cohort study. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012:37:19-27.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Pokkinen SM, Nieminen K, Yli-Hankala A, Kalliomäki ML. Persistent post-hysterectomy pain. A prospective, observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2015:32:718-24.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Montes A, Roca G, Sabate S, Lao JI, Navarro A, Cantillo J, Canet J. Genetic and clinical factors associated with chronic postsurgical pain after hernia repair, hysterectomy, and thoracotomy: a two-year multicenter cohort study. Anes- thesiology2015:122:1123-41.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Macrae WA. Chronic pain after surgery. BrJ Anaesth 2001:87:88-98.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Brandsborg B, Dueholm M, Nikolajsen L, Kehlet H, Jensen TS. A prospective study of risk factors for pain persisting 4 months after hysterectomy. Clin J Pain 2009:25, 263-8.A.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006:367:1618-25.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Guastella V, Mick G, Soriano C, Vallet L, Escande G, Dubray C, Eschalier A. A prospective study of neuropathic pain induced by thoracotomy: incidence, clinical description, and diagnosis. Pain 2011:152:74-81.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Deumens R, Steyaert A, Forget P, Schubert M, Lavand’homme P, Hermans E, De Kock M. Prevention of chronic postoperative pain: cellular, molecular, and clinical insights for mechanism-based treatment approaches. Prog Neurobiol 2013:104:1-37.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Staff NP, Engelstad J, Klein CJ, Amrami KK, Spinner RJ, Dyck PJ, Warner MA, Warner ME, Dyck PJB. Post-surgical inflammatory neuropathy. Brain 2010:133:2866-80.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Haroutiunian S, Nikolajsen L, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. The neuropathic component in persistent postsurgical pain: a systematic literature review. Pain 2013:154:95-102.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, Hansson P, Hughes R, Nurmikko T, Serra J. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology 2008:70:1630-5.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Berner E, Qvigstad E, Myrvold A, Lieng M. Pain reduction aftertotal laparoscopic hysterectomy and laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy among women with dysmenorrhoea: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2015:122:1102-11.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Uccella S, Cromi A, Casarin I, Bogani GSM, Gisone B, Pinelli C, Fasola M, Ghezzi F. Minilaparoscopic versus standard laparoscopic hysterectomy for uteri > 16 weeks ofgestation: surgical outcomes, postoperative quality of life, and cosmesis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 2015:25:386-91.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Lang K, Alexander IM, Simon J, Sussman M, Lin I, Menzin J, Friedman M, Dutwin D, Bushmakin AG, Thrift-Perry M, Altomare C, Hsu MA. The impact of multimorbidity on quality of life among midlife women: findings from a U.S. nationally representative survey. J Women’s Health 2015:24:374-83.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Ware JEJ, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-ltem short-form health survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992:30:473-83.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Apte G, Nelson P, Brismée J, Dedrick G, Justiz R, Sizer PS. Chronic female pelvic pain? Part 1: clinical pathoanatomy and examination of the pelvic region. Pain Pract 2012:12:88-110.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Cruccu G, Sommer C, Anand P, Attal N, Baron R, Garcia-Larrea L, Haanpaa M, Jensen TS, Serra J, Treede RD. EFNS guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment: revised 2009. EurJ Neurol 2010:17:1010-8.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Aalto A, Aro AR, Teperi J. RAND-36 as a measure of Health-Related Quality of Life. Reliability, construct validity and reference values in the Finnish general population. Finland: National Institute for Health and Welfare: 1999. p. 101.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Duale C, Ouchchane L, Schoeffler P, Dubray C. Neuropathic aspects of persistent postsurgical pain: a French multicenter survey with a 6-month prospective follow-up. J Pain 2014;15, 24.e1, 24.e20.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Linderoth G, Kehlet H, Aasvang EK, Werner MU. Neurophysiological characterization of persistent pain after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 2011;15:521-9.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Aasvang EK, Brandsborg B, Jensen TS, Kehlet H. Heterogeneous sensory processing in persistent postherniotomy pain. Pain 2010;150:237-42.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Aasvang EK, Kehlet H. Persistent sensorydysfunction in pain-free herniotomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2010;54:291-8.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Kehlet H, Roumen RM, Reinpold W. Invited commentary: persistent pain after inguinal hernia repair: what do we know and what do we need to know. Hernia 2013;17:293-7.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Lahtinen P, Kokki H, Hynynen M. Pain after cardiac surgery: a prospective cohort study of 1-year incidence and intensity. Anesthesiology 2006;105:794-800.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Liu TT, Raju A, Boesel T, Cyna AM, Tan SGM. Chronic pain after caesarean delivery: anAustralian cohort. Anaesth Intensive Care 2013;41:496-500.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Garry R, Fountain J, Mason S, Napp V, Brown J, Hawe J, Clayton R, Abbott J, Phillips G, Whittaker M, Lilford R, Bridgman S. The eVALuate study: two parallel randomised trials, one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy, the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy. BMJ 2004;328:129-36.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Brummer THI, Jalkanen J, Fraser J, Heikkinen AM, Kauko M, Mákinen J, Sep- pálá T, Sjoberg J, Tomás E, Harkki P. FINHYST, a prospective study of 5279 hysterectomies: complications and their risk factors. Hum Reprod 2011;26: 1741-51.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Johansen A, Schirmer H, Stubhaug A, Nielsen CS. Persistent post-surgical pain and experimental pain sensitivity inthe Tromsø study: comorbid pain matters. Pain 2014;155:341-8.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Kalliomáki M, Sandblom G, Gunnarsson U, GordhT. Persistent pain after groin hernia surgery: a qualitative analysis of pain and its consequences for quality oflife. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:236-46.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Kinney MAO, Hooten WM, Cassivi SD, Allen MS, Passe MA, Hanson AC, Schroeder DR, Mantilla CB. Chronic postthoracotomy pain and health-related quality of life. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:1242-7.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Sandblom G, Kalliomáki M, Gunnarsson U, Gordh T. Natural course of longterm postherniorrhaphy pain in a population-based cohort. Scand J Pain 2010;1:55-9.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Tu FF, Fitzgerald CM, Kuiken T, Farrell T, Harden RN. Vaginal pressure-pain thresholds: initial validation and reliability assessment in healthy women. Clin J Pain 2008;24:45-50.Search in Google Scholar

© 2015 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- Psychophysiological effects of threatening a rubber hand that is perceptually embodied in healthy human subjects

- Original experimental

- A preliminary investigation into psychophysiological effects of threatening a perceptually embodied rubber hand in healthy human participants

- Editorial comment

- Analysis of C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in pain patients – Can biomarker studies lead to better understanding of the pathophysiology of pain?

- Clinical pain research

- Serum C-reactive protein levels predict regional brain responses to noxious cold stimulation of the hand in chronic whiplash associated disorders

- Editorial comment

- Importance of early diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS-1 and CRPS-2): Delayed diagnosis of CRPS is a major problem

- Clinical pain research

- Delayed diagnosis and worsening of pain following orthopedic surgery in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Editorial comment

- Associative learning mechanisms may trigger increased burden of chronic pain; unlearning and extinguishing learned maladaptive responses should help chronic pain patients

- Original experimental

- When touch predicts pain: predictive tactile cues modulate perceived intensity of painful stimulation independent of expectancy

- Editorial comment

- Low back pain among nurses: Common cause of lost days at work and contributing to the worldwide shortage of nurses

- Observational study

- Pain-related factors associated with lost work days in nurses with low back pain: A cross-sectional study

- Editorial comment

- Assessment of persistent pelvic pain after hysterectomy: Neuropathic or nociceptive?

- Clinical pain research

- Characterization of persistent pain after hysterectomy based on gynaecological and sensory examination

- Editorial comment

- Transmucosal fentanyl for severe cancer pain: Nasal mucosa superior to oral mucosa?

- Original experimental

- Facilitation of accurate and effective radiation therapy using fentanyl pectin nasal spray (FPNS) to reduce incidental breakthrough pain due to procedure positioning

- Editorial comment

- Why do we have opioid-receptors in peripheral tissues? Not for relief of pain by opioids

- Clinical pain research

- Peripheral morphine reduces acute pain in inflamed tissue after third molar extraction: A double-blind, randomized, active-controlled clinical trial

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain and psychological distress among long-term social assistance recipients – An intolerable burden on those on the lowest steps of the socioeconomic ladder

- Clinical pain research

- The co-occurrence of chronic pain and psychological distress and its associations with salient socio-demographic characteristics among long-term social assistance recipients in Norway

- Editorial comment

- Fifty years on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain-intensity is still good for acute pain. But multidimensional assessment is needed for chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Patient reported outcome measures of pain intensity: Do they tell us what we need to know?

- Editorial comment

- Postoperative pain documentation 30 years after

- Topical review

- Postoperative pain documentation in a hospital setting: A topical review

- Editorial comment

- Aspects of pain attitudes and pain beliefs in children: Clinical importance and validity

- Observational study

- The Survey of Pain Attitudes: A revised version of its pediatric form

- Editorial comment

- The role of social anxiety in chronic pain and the return-to-work process

- Clinical pain research

- Social Anxiety, Pain Catastrophizing and Return-To-Work Self-Efficacy in chronic pain: a cross-sectional study

- Editorial comment

- Advances in understanding and treatment of opioid-induced-bowel-dysfunction, opioid-induced-constipation in particular Nordic recommendations based on multi-specialist input

- Topical review

- Definition, diagnosis and treatment strategies for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction–Recommendations of the Nordic Working Group

- Observational study

- Opioid-induced constipation, use of laxatives, and health-related quality of life

- Editorial comment

- Migraine headache and bipolar disorders: Common comorbidities

- Systematic review

- Migraine headache and bipolar disorder comorbidity: A systematic review of the literature and clinical implications

- Editorial comment

- The role of catastrophizing in the pain–depression relationship

- Clinical pain research

- The mediating role of catastrophizing in the relationship between pain intensity and depressed mood in older adults with persistent pain: A longitudinal analysis

- Announcement

- May 26-27, 2016 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain, Reykjavik, Iceland May 25, 2016 PhD course

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- Psychophysiological effects of threatening a rubber hand that is perceptually embodied in healthy human subjects

- Original experimental

- A preliminary investigation into psychophysiological effects of threatening a perceptually embodied rubber hand in healthy human participants

- Editorial comment

- Analysis of C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in pain patients – Can biomarker studies lead to better understanding of the pathophysiology of pain?

- Clinical pain research

- Serum C-reactive protein levels predict regional brain responses to noxious cold stimulation of the hand in chronic whiplash associated disorders

- Editorial comment

- Importance of early diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS-1 and CRPS-2): Delayed diagnosis of CRPS is a major problem

- Clinical pain research

- Delayed diagnosis and worsening of pain following orthopedic surgery in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Editorial comment

- Associative learning mechanisms may trigger increased burden of chronic pain; unlearning and extinguishing learned maladaptive responses should help chronic pain patients

- Original experimental

- When touch predicts pain: predictive tactile cues modulate perceived intensity of painful stimulation independent of expectancy

- Editorial comment

- Low back pain among nurses: Common cause of lost days at work and contributing to the worldwide shortage of nurses

- Observational study

- Pain-related factors associated with lost work days in nurses with low back pain: A cross-sectional study

- Editorial comment

- Assessment of persistent pelvic pain after hysterectomy: Neuropathic or nociceptive?

- Clinical pain research

- Characterization of persistent pain after hysterectomy based on gynaecological and sensory examination

- Editorial comment

- Transmucosal fentanyl for severe cancer pain: Nasal mucosa superior to oral mucosa?

- Original experimental

- Facilitation of accurate and effective radiation therapy using fentanyl pectin nasal spray (FPNS) to reduce incidental breakthrough pain due to procedure positioning

- Editorial comment

- Why do we have opioid-receptors in peripheral tissues? Not for relief of pain by opioids

- Clinical pain research

- Peripheral morphine reduces acute pain in inflamed tissue after third molar extraction: A double-blind, randomized, active-controlled clinical trial

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain and psychological distress among long-term social assistance recipients – An intolerable burden on those on the lowest steps of the socioeconomic ladder

- Clinical pain research

- The co-occurrence of chronic pain and psychological distress and its associations with salient socio-demographic characteristics among long-term social assistance recipients in Norway

- Editorial comment

- Fifty years on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain-intensity is still good for acute pain. But multidimensional assessment is needed for chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Patient reported outcome measures of pain intensity: Do they tell us what we need to know?

- Editorial comment

- Postoperative pain documentation 30 years after

- Topical review

- Postoperative pain documentation in a hospital setting: A topical review

- Editorial comment

- Aspects of pain attitudes and pain beliefs in children: Clinical importance and validity

- Observational study

- The Survey of Pain Attitudes: A revised version of its pediatric form

- Editorial comment

- The role of social anxiety in chronic pain and the return-to-work process

- Clinical pain research

- Social Anxiety, Pain Catastrophizing and Return-To-Work Self-Efficacy in chronic pain: a cross-sectional study

- Editorial comment

- Advances in understanding and treatment of opioid-induced-bowel-dysfunction, opioid-induced-constipation in particular Nordic recommendations based on multi-specialist input

- Topical review

- Definition, diagnosis and treatment strategies for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction–Recommendations of the Nordic Working Group

- Observational study

- Opioid-induced constipation, use of laxatives, and health-related quality of life

- Editorial comment

- Migraine headache and bipolar disorders: Common comorbidities

- Systematic review

- Migraine headache and bipolar disorder comorbidity: A systematic review of the literature and clinical implications

- Editorial comment

- The role of catastrophizing in the pain–depression relationship

- Clinical pain research

- The mediating role of catastrophizing in the relationship between pain intensity and depressed mood in older adults with persistent pain: A longitudinal analysis

- Announcement

- May 26-27, 2016 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain, Reykjavik, Iceland May 25, 2016 PhD course