Abstract

Background and purpose

Dealing with chronic pain is difficult and affects physiological as well as psychological well-being. Patients with chronic pain are often reporting concurrent emotional problems such as low mood and depressive symptoms. Considering this, treatments need to involve strategies for improving mood and promoting well-being in this group of patients. With the rise of the positive psychology movement, relatively simple intervention strategies to increase positive feelings, cognitions, and behaviours have become available. So far, the evidence for positive psychology techniques mainly comes from studies with healthy participants, and from studies with patients expressing emotional problems such as depression or anxiety as their main complaint. This study describes an initial attempt to explore the potential effects of a positive psychology intervention in a small sample of patients suffering from chronic pain.

Methods

A replicated single case design was employed with five participants. The participants started to fill out daily self-reports and weekly questionnaires two weeks before the intervention started, and continued throughout the intervention. In addition, they filled out a battery of questionnaires at pretest, posttest, and at a three months follow-up. The instruments for assessment were selected to cover areas and constructs which are important for pain problems in general (e.g. disability, life satisfaction, central psychological factors) as well as more specific constructs from positive psychology (e.g. compassion, savoring beliefs).

Results

The results on pre and post assessments showed an effect on some of the measures. However, according to a more objective measure of reliable change (Reliable Change Index, RCI), the effects were quite modest. On the weekly measures, there was a trend towards improvements for three of the participants, whereas the other two basically did not show any improvement. The daily ratings were rather difficult to interpret because of their large variability, both between and within individuals. For the group of participants as a whole, the largest improvements were on measures of disability and catastrophizing.

Conclusions

The results of this preliminary study indicate that a positive psychology intervention may have beneficial effects for some chronic pain patients. Although it is not to be expected that a limited positive psychology intervention on its own is sufficient to treat pain-related disability in chronic patients, our findings suggest that for some it may be an advantageous complement to enhance the effects of other interventions.

Implications

The results of this pilot study about the potential effects of a positive psychology intervention for chronic pain patients may be encouraging, warranting a larger randomized controlled study. Future studies may also concentrate on integrating positive psychology techniques into existing treatments, such as composite CBT-programs for chronic pain patients. Our advice is that positive psychology interventions are not to be regarded as stand-alone treatments for this group of patients, but may potentially enhance the effect of other interventions. However, when and for which patients these techniques may be recommended is to be explored in future research.

1 Introduction

Dealing with chronic pain affects physiological as well as psychological well-being. 15-30% of adults in Western countries suffer from persistent and disabling musculoskeletal pain [47], which makes it one of the most common reasons for work absence and general ill-health in Europe [48]. Patients with chronic pain are often reporting concurrent emotional problems such as low mood and depressive symptoms (for a review, see [49]). While around half of chronic pain patients fulfil the criteria for depression, even more suffer from depressed mood at a sub-clinical level [50]. This is problematic since concurrent pain and low mood seriously affect the patients’ level of functioning and well-being (e.g. [51,52]). Considering this, treatments need to involve strategies for improving mood and promoting well-being in this group of patients.

In the last decades, Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) has become the golden standard for addressing emotional problems in patients with chronic pain (for a review, see [53]). The emphasis in CBT for pain is generally on reducing negative affect and maladaptive coping responses such as catastrophic thinking and avoidance behaviours, to facilitate adjustment to chronic pain. There is growing evidence that instead of exclusively focusing on reducing these negative aspects, interventions designed to build and cultivate positive resources may also be of benefit to these patients [54]. Both positive emotions and optimism have been related to better adjustment to the adversity of living with chronic pain [55,56] and may therefore constitute important targets of intervention.

With the rise of the positive psychology movement, relatively simple intervention strategies to increase positive feelings, cognitions, and behaviours have become available (see e.g. [1,2]). These techniques have primarily been developed as complementary interventions for patients with mood disorders, and have shown to be effective for enhancing well-being and reducing depressive symptoms (for a review, see [3]). So far, the evidence for positive psychology techniques mainly comes from studies with healthy participants, and from studies with patients expressing emotional problems such as depression or anxiety as their main complaint. For chronic pain patients, there have been some promising attempts to develop interventions aiming at enhancing positive adjustment, e.g. by practicing loving-kindness meditation [57] and acceptance strategies [58]. Although these interventions endeavour to increase positive affect and well-being, they are often quite complex and have a broader scope than the relatively simple positive psychology techniques. To our knowledge, it has not been explored whether chronic pain patients could benefit from a rather brief program based on techniques from positive psychology.

Some preliminary evidence hints at the usefulness of positive psychology techniques for pain patients. In an experimental setting, a positive visualization exercise was shown to reduce pain sensitivity [4] and cognitive interference by pain [59]. Another study examined whether a package of different positive psychology techniques reduced pain intensity in participants with mild to moderate pain [60]. The results showed improvements in pain scores from baseline to six months follow-up. However, none of these previous studies included clinical samples.

This study describes an initial attempt to explore the potential effects of an intervention based on positive psychology techniques in a small sample of patients suffering from chronic pain using a replicated single case design.

2 Method

2.1 Design

A replicated single case design was employed with five participants. This design is recommended when new treatments are developed and evaluated [5,6]. Single case designs provide an intensive study of the individual, which includes systematic observation, manipulation of variables, repeated measurement before and during the intervention, and mainly visual data analysis. One advantage with single case designs is that it gives detailed information about how the intervention works for each participant.

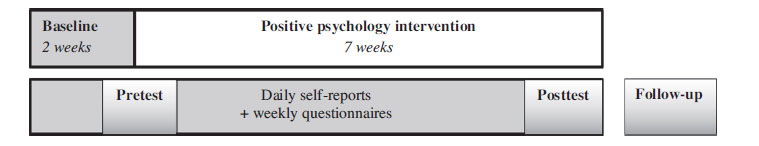

As shown in Fig. 1, the participants started to fill out daily self-reports and weekly questionnaires two weeks before the intervention started (Baseline), and continued throughout the intervention. In addition, they filled out a battery of questionnaires at pretest, posttest, and at a three months follow-up. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden.

Basic design of the study.

2.2 Ecruitment

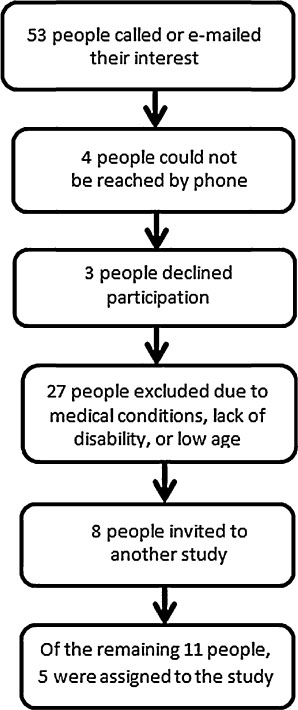

Participants were recruited through an advertisement in a local newspaper. The advertisement was formulated for recruitment of participants to a series of single case studies for people with chronic back pain. 53 people called or e-mailed their interest, and were called for a brief screening interview. The inclusion criteria was: (1) >18 years old, (2) low back pain as main complaint, (2) pain duration >three months, (3) self-reported perceived disability in daily activities (e.g. “The pain hinders me from spending time with friends”), (4) willingness to participate in a psychological intervention and research project (e.g. to fill out questionnaires), (5) medical examination had been performed, (6) no severe medical condition (e.g. cancer pain), and (7) no severe psychiatric condition (e.g. psychosis, substance abuse). Based on these criteria, 34 people were excluded, and eight were invited to participate in another SCED study [7]. Fig. 2 displays the recruitment process. Of the remaining 11 people, five were randomly assigned to the present study and were invited to participate.

Recruitment process.

2.3 Participants

Five individuals between 40 and 73 years old participated in the study, and all completed the intervention. Table 1 presents an overview of the participants, including age, sex, occupation, and their own pain description.

Description of participants.

| Participant number | Age | Sex | Work status | Pain description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 73 | Female | Retired | “Back pain since 20 years. In the last years also pain in a knee. Had a disc surgery five years ago. I cannot stay active for a longer time because of pain, which hinders me from travelling and visit museums as I would like to.” |

| 2 | 73 | Male | Retired | “Low back pain since 15 years, which has gradually increased. Also pain in my knees and I use sticks when walking. The pain hinders me to take walks with my wife and to travel as I used to.” |

| 3 | 63 | Male | Disability pension (>10 years) | “Low back pain since 20 years due to a traffic accident. Suffer from other aches as well, such as in the neck and in a foot. The pain causes me problem with sitting and doing household activities.” |

| 4 | 67 | Female | Retired | “Low back pain since more than 15 years, which has increased the last couple of years. Also pain in my knees. Had a knee operation two years ago. The pain leads to problem sleeping and staying active as I used to. I use a stick when walking.” |

| 5 | 40 | Female | Sick listed 50% | “Back pain since 15 years. Have other aches as well. Got the diagnosis fibromyalgia. The pain hinders me to do things that I like doing.” |

2.4 Procedure

The participants were invited to an individual information and kick-off meeting with one of the psychologists in the research team. At the meeting, they received verbal and written information about the purpose of the study and filled out informed consent. At the end of the meeting they filled out the pretest and the first weekly questionnaire in a separate room, and handed it in to the psychologist in a closed envelope. The participants were given a binder with forms for daily ratings and weekly questionnaires to be completed at home for two weeks of baseline assessment. They brought these ratings to the first intervention meeting with the psychologist. The psychologist collected the materials and put them in binders without looking at them or discussing with the participants. During the intervention, the participants filled out the weekly assessments in a separate room after each meeting. Moreover, the participants received forms for seven days of daily ratings to fill out at home and bring to the next intervention meeting. After the last meeting, the participants filled out the posttest and the last weekly questionnaire in a separate room, and handed them in in closed envelopes. At follow-up, questionnaires were sent to the participants and were returned in prepaid envelopes.

2.5 Positive psychology intervention

Two psychologists from the research team conducted the intervention which consisted of one-hour individual meetings once a week during seven weeks. Between the meetings, the participants were given home work assignments related to the topic of the week and were instructed to practice on a daily basis and to record their practicing in a work book. The exercises in the intervention were based on current findings from positive psychology research and consisted of techniques which had shown beneficial effects in experimental studies or in other groups of patients.

The initial intervention had a six weeks duration and consisted of the following exercises: Three Good Things [1,2], Savoring [8], Silver-lining [61] and Best Possible Self imagery [9,10]. The intervention had a gradual build-up, starting with a very simple exercise and gradually working towards more complex and cognitively effortful exercises. The first exercise was meant to shift the focus towards good and pleasant experiences in the participant’s life by having the participant write down three good things that had happened each day for one week. In the second week participants were taught savoring techniques, with the aim to increase the frequency and intensity of positive experiences in daily life. During week three, the participants practiced Silver Lining, i.e. to find something positive in a negative experience and to try to reframe the situation. Finally, the last two weeks were devoted to increasing optimism for the future by means of writing about and imagining the Best Possible Self. Two weeks of Best Possible Self imagery was previously found to increase satisfaction in life and optimism in healthy individuals [9]. In our study, the Best Possible Self exercise was slightly adapted such that participants were instructed to imagine a good life in the future despite their pain. The last session was devoted to evaluation of the intervention and developing a maintenance plan.

A pilot study on the feasibility and acceptability of this intervention was conducted with six participants. On the basis of comments from participants and therapists several changes were made to the initial exercise package. First, the Silver Lining exercise was removed. Participants expressed experiencing a conflict between the exercises they were doing in the first two weeks that were focused on identifying and savoring positive experiences and the Silver Lining exercise where they had to identify and focus on (albeit to transform) negative situations. The Silver Lining technique was replaced by Self-compassion exercises, in which the participants learned to treat themselves with compassion [11]. Because a self- compassionate attitude enhances ones ability to meet suffering with kindness and creates more openness to thoughts and emotions [62], the Self-compassion exercises were placed at the very beginning of the intervention to create the proper conditions under which the subsequent exercises would fall on fertile ground. Moreover, except for the “Three Good Things”, all exercises in the adapted intervention package were expanded over two weeks to promote continuity. Table 2 displays a summary of the content of the intervention, and references for further descriptions of each technique.

Summary of the intervention.

| Week | Content | Example ofexercises | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Rational for positive psychology Self-compassion | Becoming aware of one’s suffering | |

| The self-compassion journal | |||

| Self-compassion mantra | Neff and Lamb [11], Smeets et al. [63] | ||

| Self-compassion | Self-compassion letter | ||

| Self-compassion journal | |||

| 3 | Three good things | Three good things daily | Seligman, Rashid, & Parks [2]; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson[1] |

| 4-5 | Savoring | Savoring techniques | |

| Replay happy days | Bryant [8], Seligman et al. [2] | ||

| 6-7 | Best Possible Self (BPS) | Selecting themes for practicing BPS | |

| BPS visualization | King [46], Peters, Flink, Boersma, & Linton[10] | ||

| Maintenance plan |

2.6 Measures

The instruments for assessment were selected to cover areas and constructs which are important for pain problems in general (e.g. disability, life satisfaction, central psychological factors) as well as more specific constructs from positive psychology (e.g. compassion, savoring beliefs). The measures aimed at capturing outcome variables (i.e. more stable constructs reflecting the effect of the intervention) as well as process variables (i.e. constructs directly targeted through different techniques). Table 3 displays a summary of outcome and process variables as well as the assessment points. Swedish versions of all questionnaires were used.

Scores on pre and post assessments for all participants.

| Pre assessment (participant number; score) | Post assessment (participant number; score) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (questionnaire; scale) | #1 | #2 | #3 | #4 | #5 | #1 | #2 | #3 | #4 | #5 |

| Outcome variables | ||||||||||

| Pain Disability Index (PDI; 0–70) | 40 | 32 | 38 | 18 | 35 | 18[a] | 19[a] | 32 | 18 | 32 |

| Life satisfaction (SWLS; 5–35) | 18 | 26 | 23 | 13 | 25 | 21 | 23 | 35[a] | 23[a] | 25 |

| Depressed mood (HADS-D; 0–21) | 7 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3[a] | 3 |

| Anxiety (HADS-A; 0–21) | 13 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 8 | 7[a] | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Process variables | ||||||||||

| Self-compassion (SCS; 12–60) | 34 | 41 | 34 | 30 | 27 | 39 | 45 | 56[a] | 29 | 36[a] |

| Savoring beliefs (SBI; 24–168) | 137 | 110 | 109 | 106 | 138 | 133 | 130[a] | 123 | 138[a] | 137 |

| Life Orientation Test (LOT-R; 0–24) | 15 | 13 | 21 | 18 | 15 | 11 | 14 | 21 | 18 | 15 |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS; 0–52) | 29 | 21 | 17 | 36 | 16 | 19 | 9[a] | 2[a] | 26 | 18 |

| Repetitive thinking (PTQ; 0–60) | 28 | 19 | 3 | 36 | 23 | 21 | 17 | 4 | 11[a] | 23 |

| Psychological flexibility (AAQ; 10–70) | 48 | 51 | 67 | 52 | 57 | 55 | 56 | 67 | 60 | 60 |

2.7 Pre, post and follow-up

2.7.1 Disability

The Pain Disability Index (PDI) [12] was used to assess disability. The PDI is a brief instrument, describing seven areas of everyday activities that may be difficult to perform for people with chronic pain (e.g. “Social activities”, “Sexual behavior”). Responders are asked to what degree each activity is hindered by pain at an eleven- point scale (0 = no interference; 10 = total interference).The PDI has shown good psychometrics [13,14].

2.7.2 Life satisfaction

The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) [15] was used to assess global life satisfaction. The SWLS consists of five statements (e.g. “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”, “I am satisfied with my life”). Answers are given on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). The SWLS has shown satisfactory psychometric properties [16,17,18].

2.7.3 Depressed mood and anxiety

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [19] was used to assess depressed mood and anxiety. The HADS is divided into two subscales with seven items each, aiming at capture common symptoms of depression (e.g. “I have lost interest in my appearance”) and anxiety (“I feel tense and wound up”). Responders rate to what extent they agree with each statement on a four-point scale (0 = not at all; 3 = very much indeed). The HADS has shown satisfactory validity and reliability [2021,22].

2.7.4 Self-compassion

The short form of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-SF) [23] was used to assess perceived ability of being kind and understanding towards oneself in moments of pain or difficulties. The SCS-SF consists of 12 statements (e.g. “I try to see my failings as part of the human condition”, “When I fail at something that’s important to me I tend to feel alone in my failure”). Answers are given on a five- point scale (1 = almost never; 5 = almost always).The SCS has shown sufficient reliability and validity [23].

2.7.5 Savoring beliefs

The Savoring Beliefs Inventory (SBI) [8] was used to assess beliefs about one’s own capacity to savor positive outcomes. The SBI contains 24 items divided into three subscales: anticipating upcoming positive events (e.g. “I can feel the joy of anticipation”), savoring the moment (e.g. “I know how to make the most of good time”), and reminiscing part positive experiences (e.g. “I enjoy looking back on happy times”). Respondents rate to what extent they agree with each statement on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree). The SBI has been found to have sufficient psychometric properties, including the three-factor structure [8].

2.7.6 Optimism

The Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) [24] was used as a global measure of optimism. The LOT-R consists of six items assessing optimistic thoughts (e.g. “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best”) and four filler items. Respondents are asked to what extent they agree with each statement on a five-point scale (0 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). The LOT-R has been recommended as a valid measure of optimism [25], and recent findings support using the measure as a unidimensional scale [26].

2.7.7 Repetitive thinking

The Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ) [27] was used to assess generic repetitive thinking. The PTQ consists of 15 statements (e.g. “Thoughts intrude into my mind”, “I can’t stop dwelling on them”), and responders rate to what extent each statement is true for them on a five-point scale (0 = never; 4 = almost always). The PTQhas shown sufficient psychometric properties [27,28].

2.7.8 Psychological flexibility

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) [29] was used to assess generic psychological flexibility. The AAQ-II consists of 10 statements (e.g. “It is OK if I remember something unpleasant”; “My thoughts and feelings do not get in the way of how I want to live my life”). The responders are asked to what degree each statement is true for them on a seven-point scale (1 = never true; 7 = always true). The AAQ-II has shown satisfactory psychometric properties [29], including in a chronic pain population [30].

2.8 Weekly measures

In the weekly assessments, the participants were asked to think about the past week when responding to the questions.

2.8.1 Positive and negative affect

The 20-items version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [31] was used to assess positive and negative affect. This version of the PANAS consists of 10 descriptors of positive mood (e.g. “interested”, “alert”) and 10 descriptors of negative mood (e.g. “hostile”, “irritable”). The respondents rate to what extent they experience each descriptor a five-point scale (1 = very slightly or not at all; 5 = extremely). The PANAS is a widely used measure, and has shown good validity and measurement properties [32].

2.8.2 Pain catastrophizing

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale [33] was used to assess pain- related catastrophizing. The PCS describes 13 thoughts and feelings that people may have when experiencing pain, and is divided into three subscales: magnification (e.g. “I keep thinking of other painful events”), rumination (e.g. “I can’t seem to keep it out of my mind”), and helplessness (e.g. “I feel I can’t go on”). Respondents are asked to what extent they experience each thought and feeling on a five- point scale (0 = not at all; 4 = all the time). The PCS is a widely used measure and has shown satisfactory psychometric properties [33].

2.9 Daily ratings

The participants were asked to think about their present day when filling out the daily ratings. For these questions, answers were given on eleven-point scales with 0 and 10 as endpoints (labels depending on questions). These results are available as supplementary material (Figs. 8-12).

2.9.1 Pain

One question was used for assessing pain intensity (“Today my pain was...”).

2.9.2 Function

Five questions from the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire (OMPSQ) [34] were used to assess function (e.g. “I can do ordinary household chores”, “I can do light work for an hour”). The respondents rate to what degree they are able to perform each activity. The OMPSQ has shown to be a reliable and valid instrument for assessing psychosocial factors in people with musculoskeletal pain [35,36].

2.9.3 Catastrophizing

One question from each subscale in the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS; magnification, rumination, helplessness) [33] was used to create a daily measure of catastrophizing (“When I’m in pain I wonder whether something serious may happen”, “When I’m in pain I keep thinking about how badly I want the pain to stop”, “When I’m in pain I feel I can’t go on”).

2.9.4 Well-being

Four questions from the 12-item Well-Being Questionnaire (W-BQ12) [37] were used to assess general well-being. The W-BQ12 contains statements aiming at capturing general psychological well-being (e.g. “I live the kind of life I want to”, “I am happy, satisfied or pleased with my personal life”). The W-BQ12 has been recommended as a reliable and valid measure of psychological well-being [37].

2.10 Analyses

The weekly ratings are presented in graphs to enable visual inspection. The effects are evaluated mainly by inspecting changes between phases: baseline vs. intervention. Specifically, changes in mean, level and trend are important [5]. Descriptive data is presented for pretest and posttest. To facilitate evaluation of changes from pretest to posttest, Reliable Change Index (RCI) was calculated as an indicator of whether the changes in scores were beyond change that could be due to measurement error. The RCI equals the difference between a participant’s pretest and posttest scores, divided by the standard error of the difference [38]. To create the RCI, we used data from earlier studies using the same measures in chronic pain samples when accessible, and when not, studies using the measures in samples with mood disorders.

3 Results

The results will be organized around individual participants first, separating between outcome and process variables. Table 3 presents the scores on pre and post assessments for all participants. The results will then be considered for the group as a whole, summarizing the main findings from the study.

In the graphs presenting weekly ratings for each participant, the area to the left presents scorings during baseline, and the area to the right presents scorings during the intervention. There is a small area at the right side representing scorings at follow-up.

Daily ratings are presented as supplementary material. In the graphs, regression slopes are plotted within each area separately, as an aid in evaluating possible changes in trend between the baseline and the intervention phases.

3.1 Participant 1

3.1.1 Pre and post assessments

As can be seen in Table 3, participant 1 improved from pretest to posttest on all outcome measures. The improvements on measures of disability and anxiety were reliable changes according to the Reliable Change Index (RCI). Considering process variables, this participant improved on all measures, except for optimism and savoring. On catastrophizing this participant scored 10 points lower at posttest. None of the improvements on the process variables was reliable change according to the RCI.

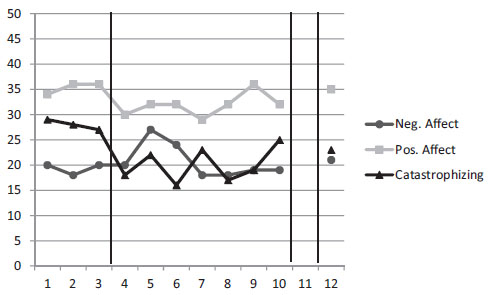

3.1.2 Weekly measures

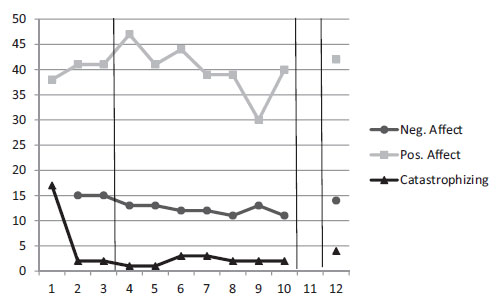

Fig. 3 displays scores on weekly measures of central process variables for participant 1. As can be seen, catastrophizing decreased at the beginning of the intervention and increased at the end, but at follow-up the scores were notably lower than at baseline. Positive and negative affect remained fairly stable.

Scores on weekly measures of central process variables for participant 1.

3.2 Participant 2

3.2.1 Pre and post assessments

As can be seen in Table 3, participant 2 improved on all outcome measures except for life satisfaction. However, depressed mood and anxiety were low already at pretest. The improvement on disability was reliable change according to the RCI. Considering process variables, participant 2 improved on all measures. The improvements on savoring beliefs and catastrophizing were reliable changes, according to the RCI.

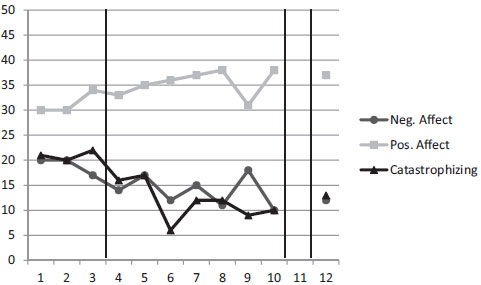

3.2.2 Weekly measures

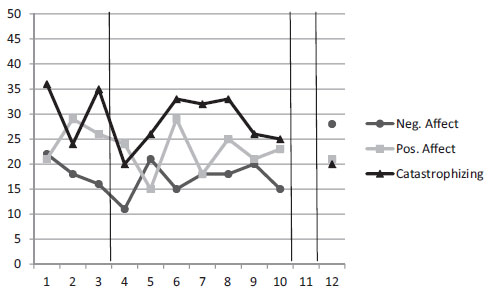

Fig. 4 displays scores on weekly measures of central process variables for participant 2. As can be seen, both catastrophizing and negative affect decreased notably during the intervention, and positive affect increased. Some improvements may be noted already during baseline. Improvements remained at follow-up.

Scores on weekly measures of central process variables for participant 2.

3.3 Participant 3

3.3.1 Pre and post assessments

As can be seen in Table 3, regarding outcome variables, participant 3 improved on measures of disability and life satisfaction, and the change on life satisfaction was reliable change according to the RCI. Depressed mood and anxiety were low already at pretest. On the process variables, participant 3 improved on three measures. The improvements on catastrophizing and self-compassion were reliable changes according to the RCI.

3.3.2 Weekly measures

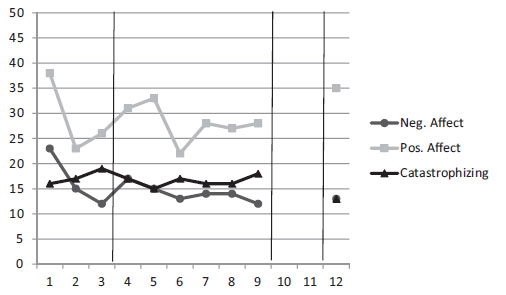

Fig. 5 displays scores on weekly measures of central process variables for participant 3. As shown in the figure, already at baseline this participant scored low on catastrophizing and negative affect and high on positive affect, and this pattern of scorings remained stable during the intervention.

Scores on weekly measures of central process variables for participant 3.

3.4 Participant 4

3.4.1 Pre and post assessments

As can be seen in Table 3, participant 4 improved on all outcome variables except for disability which was low already at pretest and remained stable. The improvements on depressed mood and life satisfaction were reliable changes according to the RCI. This participant improved on all process variables except for optimism which remained stable. The improvements on repetitive thinking and savoring were reliable changes according to the RCI.

3.4.2 Weekly measures

Fig. 6 displays scores on weekly measures of central process variables for participant 4. As shown in the figure, this participant increased in catastrophizing and negative affect during the intervention, but this trend changed during the last weeks of the intervention and at the end there was a reduction on both variables. At follow-up catastrophizing decreased further whereas negative affect increased. Positive affect varied during the intervention but ended up at a similar level as at baseline. It should be noted that this participant got a severe infection with pneumonia right after the intervention started, which lasted for several weeks. This affected her functioning and well-being negatively.

Scores on weekly measures of central process variables for participant 4.

3.5 Participant 5

3.5.1 Pre and post assessments

As can be seen in Table 3, this participant scored similar at pretest and posttest on all outcome variables except for anxiety, which improved somewhat. The process variables also remained similar, except for self-compassion, which increased with a reliable change according to the RCI.

3.5.2 Weekly measures

Fig. 7 displays scores on weekly measures of central process variables for participant 5. This participant displayed no clear trend during the intervention. Especially catastrophizing remained stable.

Scores on weekly measures of central process variables for participant 5.

3.6 Summary of the main findings

Taken together, most improvements were on measures used for the pretest and posttest. Changes remained stable to the follow-up assessment, which is displayed in Table 4 (supplementary material). Considering outcome variables, participants 1, 2, 3, and 4 improved on most measures from pretest to posttest, but only some of these changes (6 out of 14) were reliable changes according to the Reliable Change Index (RCI). Depressed mood and anxiety improved for participants 1, 4, and 5 but were fairly low already at baseline for the remaining two participants. Participants 1, 2, 3, and 4 improved on most process variables. However, optimism remained stable from pretest to posttest for all participants. The most consistent improvements were on catastrophizing (10–15 points), although only two of these improvements were reliable changes according to the RCI. Participant 5 basically did not change at all from pretest to posttest.

The weekly scores on central process variables follows the same trend with improvements on catastrophizing for participants 1, 2, and 4, whereas the scorings on this variable remained stable for participants 3 and 5. Only participant 2 improved on positive and negative affect.

4 Discussion

The aim of this pilot study was to explore the effects of a positive psychology intervention for a small sample of patients with chronic pain, using a replicated single case design. Overall, the results on pre and post assessments indicate some improvements for most participants. Four out of five participants (#1,2, 3, and 4) seemed to improve from pre to post on most outcome and process variables, and the ratings remained stable to follow-up. However, when employing a more objective measure of change, the effects were quite modest; only a few (13 out of 50 possible) of the improvements were reliable changes according to the Reliable Change Index (RCI). On the weekly measures, there was a trend towards improvements for three of the participants (#1,2, and 4), whereas the other two (# 3 and 5) basically did not show any improvements. The daily ratings were rather difficult to interpret because of their large variability, both between and within individuals. Taken together, the results of this preliminary study indicate that a positive psychology intervention may have beneficial effects for some chronic pain patients, but there are several methodological and clinical aspects that need to be considered.

For the group of participants as a whole, the largest improvements were on measures of disability and catastrophizing. It is noteworthy that a fairly simple intervention like the one in the current study may assist in decreasing disability in some patients with a long history of pain-related problems. In four of the participants (#1,2,3, and 5), the initial levels of disability were comparable with patients seeking care at pain clinics [13,39]. Although it is not to be expected that a limited positive psychology intervention on its own is sufficient to treat pain-related disability in chronic patients, our findings indicate that for some it may be an advantageous complement to enhance the effect of other interventions.

The effect of the intervention seemed to be most apparent on pain catastrophizing. All patients displayed baseline levels that were similar to those of clinical samples [40]. After the intervention, four out of five (# 1, 2, 3, and 4) had improved 10 points or more on this measure. This is valuable information, since earlier studies have pointed out that there is a need for additional strategies for high catastrophizing patients [41], and especially for the ones with concurrent depressive symptoms as treatments often fail to help these patients [41]. Moreover, catastrophizing has been identified as a mediator of treatment effect in CBT [42]. There is also data that reductions in catastrophizing may mediate the link between increased optimism and lower levels of pain [4]. Possibly, positive psychology techniques may be offered as one strategy among others, for counteracting catastrophizing.

Even though one of the exercises of the intervention (i.e. the Best Possible Self exercise) specifically focused on optimism, none of the patients actually showed an increase in the level of optimism. One plausible explanation is that global optimism is a too stable construct to be affected by a brief intervention like the current one (for a review, see [43]). Nevertheless, a similar Best Possible Self intervention in a student sample did increase levels of optimism [9]. It may be speculated that in middle aged pain patients optimism is less modifiable because of a longer history of adverse experiences and a more ingrained habitual pattern of thinking. In a recent review of positive psychology interventions, the authors put forward increased well-being as one main outcome of positive psychology activities [44]. This is in line with our findings, where the trend was that the participants improved on measures of well-being in terms of mood and life satisfaction.

In the current study, the RCI was used as an indicator of improvements that were beyond changes that could be due to measurement errors. The advantage of calculating the RCI is to provide a more objective measure of change, which may signal the possible reliability of occurred improvements [38]. The drawback is that it is based on rather stringent criteria, and it is evident in our study that in some cases fairly large improvements in terms of absolute scores failed to reach the level of significance according to the RCI.

It is possible that clearer effects may have been obtained if we had selected the participants on basis of other criteria than the ones employed. Participants were selected on the basis of a considerable level of self-reported perceived disability, but they did not necessarily suffer from low mood. Since positive psychology techniques were primarily developed for patients with emotional distress [3], it is uncertain whether those who already display moderate levels of positive mood would actually benefit from the intervention. In our study, three of the participants (# 1, 4, and 5) had clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms or anxiety at baseline (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS, score >7; [20]), and these participants improved significantly according to cut-off levels. The other two participants displayed low levels already at baseline, and their scorings remained stable. It might be considered a weakness of this study that low mood was not used as an inclusion criteria, since it implies difficulties to draw conclusions because of variability between individuals. Preferably, future studies on this topic would focus primarily on chronic pain patients with markedly elevated levels of emotional distress.

The daily measure for assessing change in key domains is critical in experimental designs like the one employed here. In the current study, there was large variability between individuals and the data was difficult to interpret. There are a couple of potential explanations for that. First and foremost, the items used for daily ratings were derived from existing questionnaires, but it may be that the few selected questions did not entirely capture the concepts. Second, the fact that the participants answered the same questions on a daily basis may have influenced their responses. Indeed, repeated measurements have been identified as a challenging issue in this type of design [45]. On basis of this preliminary study, we would like to underscore the importance of piloting and refining the daily measures in future studies using this design.

It should be noted that the results cannot be compared to those obtained from larger studies, using randomized controlled designs. This is a small study with only five participants and the conclusions that can be drawn are limited. Nevertheless, single case design is well suited for testing new treatments, and has been recommended as first choice when developing and refining the methods (Ibid.). However, it should be noted that we cannot tell the effect of each exercise, since this study involved a composite package of techniques. This design allows careful investigation of the effects at an individual level, which generally elicit hypotheses about what patients may benefit from the methods and under what circumstances. Moreover, the greatest threats to internal validity are ruled out, since the participants serve as their own control. Consequently, a replicated single case design appeared as a sound design for this study, which is the first one exploring positive psychology for patients with chronic pain. Unfortunately, we did not have the possibility to randomize individuals to different lengths of baseline, which would have further strengthened the design. Still, this study is to be viewed as an initial explorative attempt, but larger randomized controlled trials are needed to further investigate the effects.

Future studies may also concentrate on integrating positive psychology techniques into existing treatments, such as composite CBT-programs for chronic pain patients. Our advice is that positive psychology interventions are not to be regarded as stand-alone treatments for this group of patients, but may potentially enhance the effect of other interventions. However, when and for which patients these techniques may be recommended is to be explored in future research. Taken together, although the effects appear to be small, they may be encouraging, warranting a larger randomized controlled study. Moreover, it should be considered whether it is more beneficial to incorporate positive psychology techniques into composite CBT programs to optimize the profits for patients suffering from chronic pain problems.

Highlights

Patients with chronic pain are often reporting concurrent emotional problems.

Treatments need to involve strategies for improving mood and well-being.

This study explores the effects of positive psychology techniques for pain patients.

A replicated single case design was employed with five participants.

The results indicated that these techniques may work for some pain patients.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2015.02.004.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2015.01.005.

References

[1] Seligman MEP, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am Psychol 2005;60:410.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol 2006;61:774.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 2013;13:119.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Hanssen MM, Vancleef LMG, Vlaeyen JWS, Peters ML. More optimism, less pain! The influence of generalized and pain-specific expectations on experienced cold-pressor pain.J Behav Med 2014;37:47–58.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Kazdin AE. Research design in clinical psychology. 4th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Tate R Mcdonald S, Perdices M, Togher L, Schultz R, Savage S. Rating the methodological quality of single-subject designs and n-of-1 trials: introducing the Single-Case Experimental Design (SCED) Scale. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2008;18:385–401.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Linton SJ, Fruzzetti AE. A hybrid emotion-focused exposure treatment for chronic pain: a feasibility study. Scand J Pain 2014;5:151–8.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Bryant F. Savoring Beliefs Inventory (SBI): a scale for measuring beliefs about savouring. J Mental Health 2003;12:175–96.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Meevissen Y, Peters ML, Alberts HJEM. Become more optimistic by imagining a best possible self: effects of a two week intervention. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2011;42:371–8.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Peters ML, Flink IK, Boersma K, Linton SJ. Manipulating optimism: can imagining a best possible self be used to increase positive future expectancies? J Posit Psychol 2010;5:204–11.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Neff KD, Lamb LM. Self-compassion. In: Handbook of individual differences in social behavior; 2009. p. 561–73.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Tait RC, Pollard CA, Margolis RB, Duckro PN, Krause SJ. The Pain Disability Index: psychometric and validity data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1987;68:438–41.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Krause S. The pain disability index: psychometric properties. Pain 1990;40:171–82.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Grönblad M, Hupli M, Wennerstrand P, Järvinen E, Lukinmaa A, Kouri J-P, Kara-harju EO. Intel-correlation and test-retest reliability of the Pain Disability Index (PDI) and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODQ) and their correlation with pain intensity in low back pain patients. Clin J Pain 1993;9:189–95.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess 1985;49:71–5.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Arrindell WA, Meeuwesen L, Huyse FJ. The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS): psychometric properties in a non-psychiatric medical outpatients sample. Pers Individ Diff 1991;12:117–23.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychol Assess 1993;5:164.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Pavot W, Diener E, Colvin CR, Sandvik E. Further validation of the Satisfaction With Life Scale: evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. J Pers Assess 1991;57:149–61.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psyc-hiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Herrmann C. Internal experiences with the Hospital Anxiet and Depression Scale - a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res 1997;42:17–41.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Lisspers J, Nygren A, Söderman E. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD): some psychometric data for a Swedish sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997;96:281–6.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clin Psychol Psychother 2011;18:250–5.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1994;67:1063.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Burke KL, Joyner AB, Czech DR, Wilson MJ. An investigation of concurrent validitybetweentwo optimism/pessimism questionnaires: the life orientation test-revised and the optimism/pessimism scale. Curr Psychol 2000;19:129–36.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Segerstrom SC, Evans DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA. Optimism and pessimism dimensions in the Life Orientation Test-Revised: method and meaning. J Res Pers 2011;45:126–9.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Ehring T, Zetsche U, Weidacker K, Wahl K, Schonfeld S, Ehlers A. The Perse-verative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ): validation of a content-independent measure of repetitive negative thinking. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2011;42:225–32.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Ehring T, Raes F, Weidacker K, Emmelkamp PMG. Validation of the Dutch version of the PerseverativeThinkingQuestionnaire (PTQ-NL). Eur J PsycholAssess 2012;28:102.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KC, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, Zettle RD. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire - II: a revised measure of psychological flexibility and acceptance. Behav Ther 2011:1–38.Search in Google Scholar

[30] McCracken LM, Zhao-O’Brien J. General psychological acceptance and chronic pain: there is more to accept than the pain itself. Eur J Pain 2010;14: 170–5.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Crawford JR, Henry JD. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2004;43:245–65.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess 1995;7:524–32.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Linton SJ, Halldén K. Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain. Clin J Pain 1998;14:209.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Linton SJ, Boersma K. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: the predictive validity of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Clin J Pain 2003;19:80–6.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Westman A, Linton SJ, Öhrvik J, Wahlen P, Leppert J. Do psychosocial factors predict disability and health at a 3-year follow-up for patients with nonacute musculoskeletal pain? A validation of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Eur J Pain 2008;12:641–9.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Pouwer F, van der Ploeg HM, Adèr HJ, Heine RJ, Snoek FJ. The 12-item Well-Being Questionnaire. An evaluation of its validity and reliability in Dutch people with diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999;22:2004–10.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:12.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Denison E, Åsenlöf P, Lindberg P. Self-efficacy fear avoidance, and pain intensity as predictors of disability in subacute and chronic musculoskeletal pain patients in primary health care. Pain 2004;111:245–52.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Sullivan MJL. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale user manual. Montreal: McGill University; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Flink IKL, Boersma K, Linton SJ. Pain catastrophizing as repetitive negative thinking: a development of the conceptualization. Cogn Behav Ther 2013;42:215–23.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Smeets RJEM, Vlaeyen JWS, Kester ADM, Knottnerus JA. Reduction of pain catas-trophizing mediates the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. J Pain 2006;7:261–71.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: theoretical overview and empirical update. Cogn Ther Res 1992;16:201–28.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Lyubomirsky S, Layous K. How do simple positive activities increase wellbeing? Curr Direct Psychol Sci 2013;22:57–62.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Kazdin AE. Single-case research designs: methods for clinical and applied settings. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[46] King LA. The health benefits of writing about life goals. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2001;27:798–807.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Nachemson AL, Jonsson E, editors. Neck and back pain. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Eurostat. Health and safety at work in Europe (1999–2007). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Linton SJ, Bergbom S. Understanding the link between depression and pain. Scandinavian Journal of Pain 2011;2:47–54.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Clyde Z, Williams AC. Depression and mood. In: Linton SJ, editor. New avenues for the prevention ofchronic musculoskeletal pain and disability. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2002. p. 105–21.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity. Archives of Internal Medicine 2003;163:2433–45.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Pincus T, Vogel S, Burton AK, Santos R, Field AP. Fear avoidance and prognosis in back pain: A systematic review and synthesis of current evidence. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2006;54:3999–4010.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Individuals With Chronic Pain: Efficacy, Innovations, and Directions for Research. American Psychologist 2014;69:153–66.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Keefe FJ, Wren AA. Optimism and pain: A positive move forward. Pain 2013;154:7–8.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Goodin BR, Bulls HW. Optimism and the Experience of Pain: Benefits of Seeing the Glass as Half Full. Current Pain and Headache Reports 2013;17 (329), http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11916-013-0329-8.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ. Resilience: a new paradigm for adaptation to chronic pain. Current pain and headache reports 2010;14:105–12.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Carson JW, Keefe FJ, Lynch TR, Carson KM, Goli V, Fras AM, Thorp SR. Lovingkindness meditation for chronic low back pain results from a pilot trial. Journal of Holistic Nursing 2005;23:287–304.Search in Google Scholar

[58] McCracken LM, Eccleston C. A prospective study of acceptance of pain and patient functioningwithchronic pain. Pain 2005;118:164–9.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Boselie JJ, Vancleef LM, Smeets T, Peters ML. Increasing optimism abolishes pain-induced impairments in executive task performance. Pain 2014;155 (2):334–40.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Hausmann LR, Parks A, Youk AO, Kwoh CK. Reduction of Bodily Pain in Response to an Online Positive Activities Intervention. The Journal of Pain 2014;15:560–7.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Riskind JH, Sarampote CS, Mercier MA. For every malady a sovereign cure: Optimism training. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy 1996;10:105–17.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Neff KD, Kirkpatrick KL, Rude SS. Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of research in personality 2007;41:139–54.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Smeets E, Neff K, Alberts H, Peters M. Meeting Suffering With Kindness: Effects of a Brief Self-Compassion Intervention for Female College Students. Journal of clinical psychology 2014;70:794–807.Search in Google Scholar

© 2015 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- The importance of studying personality traits and pain in the oldest adults

- Clinical pain research

- The influence of personality traits on perception of pain in older adults – Findings from the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care – Blekinge study

- Editorial comment

- Sinomenine is a promising analgesic and antihyperalgesic for pain and hypersensitivity in rheumatoid arthritis

- Original experimental

- Sinomenine alleviates mechanical hypersensitivity in mice with experimentally induced rheumatoid arthritis

- Editorial comment

- Oral immediate and prolonged release oxycodone for safe and effective patient controlled analgesia after surgery Can opioid for acute postoperative pain be improved by adding a peripheral opioid antagonist?

- Clinical pain research

- Oral oxycodone for pain after caesarean section: A randomized comparison with nurse-administered IV morphine in a pragmatic study

- Editorial comment

- Nitrous oxide in oxygen (50:50) is analgesic that requires optimal inhalation procedure

- Clinical pain research

- Nitrous oxide analgesia for bone marrow aspiration and biopsy – A randomized, controlled and patient blinded study

- Editorial comment

- Ketamine has anti-hyperalgesic effects and relieves acute pain, but does not prevent persistent postoperative pain (PPP)

- Systematic review

- Intra- and postoperative intravenous ketamine does not prevent chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Editorial comment

- Raising the standards of preclinical pain studies

- Topical review

- Experimental design and reporting standards for improving the internal validity of pre-clinical studies in the field of pain: Consensus of the IMI-Europain consortium

- Editorial Comment

- Single cases are complex Illustrated by Flink et al. ‘Happy despite pain: A pilot study of a positive psychology intervention for patients with chronic pain’

- Clinical pain research

- Happy despite pain: Pilot study of a positive psychology intervention for patients with chronic pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- The importance of studying personality traits and pain in the oldest adults

- Clinical pain research

- The influence of personality traits on perception of pain in older adults – Findings from the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care – Blekinge study

- Editorial comment

- Sinomenine is a promising analgesic and antihyperalgesic for pain and hypersensitivity in rheumatoid arthritis

- Original experimental

- Sinomenine alleviates mechanical hypersensitivity in mice with experimentally induced rheumatoid arthritis

- Editorial comment

- Oral immediate and prolonged release oxycodone for safe and effective patient controlled analgesia after surgery Can opioid for acute postoperative pain be improved by adding a peripheral opioid antagonist?

- Clinical pain research

- Oral oxycodone for pain after caesarean section: A randomized comparison with nurse-administered IV morphine in a pragmatic study

- Editorial comment

- Nitrous oxide in oxygen (50:50) is analgesic that requires optimal inhalation procedure

- Clinical pain research

- Nitrous oxide analgesia for bone marrow aspiration and biopsy – A randomized, controlled and patient blinded study

- Editorial comment

- Ketamine has anti-hyperalgesic effects and relieves acute pain, but does not prevent persistent postoperative pain (PPP)

- Systematic review

- Intra- and postoperative intravenous ketamine does not prevent chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Editorial comment

- Raising the standards of preclinical pain studies

- Topical review

- Experimental design and reporting standards for improving the internal validity of pre-clinical studies in the field of pain: Consensus of the IMI-Europain consortium

- Editorial Comment

- Single cases are complex Illustrated by Flink et al. ‘Happy despite pain: A pilot study of a positive psychology intervention for patients with chronic pain’

- Clinical pain research

- Happy despite pain: Pilot study of a positive psychology intervention for patients with chronic pain