Abstract

Background and aims

The present randomized open label parallel group study was conducted to evaluate if an oral oxycodone (OXY) regimen can be at least equally effective and as safe for postoperative analgesia after caesarean section (CS) as a standard of care program using nurse-administered intravenous morphine (IVM), followed by oral codeine.

Methods

Eighty women (40 + 40) were scheduled for elective CS under spinal anaesthesia. All patients received postoperative multimodal analgesic therapy, including ibuprofen and paracetamol. The OXY group got standardized extended release and short acting oral treatment (and in a few cases intravenous OXY) as needed and the other group received current standard of care, IVM as needed for 24 h, followed by codeine. Opioid treatment lasted maximum five days. Outcome measures were pain intensity (numerical rating scale, NRS), opioid requirements, duration of administering opioids and safety for mother and newborn. All opioids in the study were expressed in OXY equivalents, using a conversion table. As the bioavailability of each opioid has a certain extent of interindividual bioavailability this conversion represents an approximation. The possible influence of opioids on the newborns was evaluated by the Neurological Adaptive Capacity Score at birth and at 24 and 48 h.

Results

During the first 24 h, there were no differences between treatments in opioid requirements or mean pain intensity at rest but pain intensity when asking for rescue medication was lower in the OXY than in the IVM group (mean ± SD; 5.41 ± 6.42 vs. 6.42 ± 1.61; p = 0.027). Provoked pain (uterus palpation) during the first 6h was also less in the OXY group (3.26 ± 2.13 vs. 4.60 ± 2.10; p = 0.007). During the 25–48 h period postoperatively, patients on OXY reported significantly lower pain intensity at rest (2.9 ± 1.9 vs. 3.8 ± 1.8; p = 0.039) and consumed less opioids (OXY equivalents; mg) (31.5 ± 9.6 vs. 38.2 ± 38.2; p = 0.001) than those on IVM/codeine. The total amount of opioids 0–5 days postoperatively was significantly lower in the OXY than in the IVM/codeine group (108.7 ± 37.6 vs. 138.2 ± 45.1; p = 0.002). Duration of administering opioids was significantly shorter in the OXY group. Time to first spontaneous bowel movement was shorter in the OXY group compared with the IVM/codeine group. No serious adverse events were recorded in the mothers but the total number of common opioid adverse effects was higher among women on IVM/codeine than among those receiving OXY (15 vs. 3; p = 0.007). No adverse outcomes in the newborns related to treatment were observed in either group.

Conclusions

In a multimodal protocol for postoperative analgesia after CS better pain control and lower opioid intake was observed in patients receiving oral OXY as compared to those on IVM/codeine. No safety risks for mother and child were identified with either protocol.

Implications

Our findings support the view that use of oral OXY is a simple, effective and time saving treatment for postoperative pain after CS.

1 Introduction

Postoperative pain treatment in women undergoing caesarean section (CS) needs to be effective to enable fast and smooth recovery without adverse outcomes and to improve breastfeeding and bonding between mother and child. It is also important that pain treatment should have minimal impact on the newborn [1].

In spite of this, ineffective postoperative pain treatment regimens are common [2,3]. There is a lack of guidelines for post caesarean pain management, not only in Sweden but also in many other countries, even though neuraxial blockade in combination with non-opioids has been suggested as golden standard [3,4]. Patient controlled analgesia (PCA) with morphine has also been used for postoperative pain control [5]. However, i.v. administration of morphine to women after CS is mostly used for a short period of time and the PCA-device itself might cause some practical inconvenience for the mother. Also weak opioids are still commonplace in the prolonged postoperative period, codeine + paracetamol often being the standard of care after surgeries [6]. Multimodal postoperative pain treatment has been shown to be more effective than monotherapy [7,8]. Many advantages can be identified with oral medication, including simplicity, time saving vs. i.v. medication and makes the patient more independent [9].

Overall, oral low-tech treatment regimens are preferred, both by patients and ward staff, but they need to be efficient with a good safety profile and allow for patients to ambulate freely.

The precursor drug codeine may be problematic to rely on for efficacy. The analgesic effect of codeine is attributed to the individuals’ ability to convert codeine to morphine via CYP2D6. The CYP2D6 genotype has three important phenotypes: rapid (normal), slow and ultrarapid metabolizers. The latter will have a markedly higher exposure to morphine [10,11]. The genetic predisposition for either phenotype has considerable variability due to ethnicity, which makes standardization of treatment regimens challenging in a mixed ethnic population.

Recent case reports address neonatal safety concerns, including death, when the mother has been taking codeine for a prolonged period of time [12,13]. Using oral morphine instead of codeine would reduce inter-individual variation in exposure. Another option is to use oral oxycodone, which has a higher and more predictable oral bioavailability (67–80%) than morphine (19–47%) [14,15]. Substituting codeine with oral OXY can therefore be expected to further reduce the variation in bioavailability and analgesic effect [15,16]. Seaton et al. studied to what extent OXY passes into breast milk, but only a few variables concerning the child were reported [17]. The standard multimodal treatment following CS in our department has included intravenous (i.v.) morphine (IVM), which after 24 h was substituted by oral codeine. The ethnic composition of patients in our department includes groups with high prevalence of slow metabolizers as well as groups with high prevalence of ultra-rapid metabolizers, which puts high demands on a standard of care that is safe and efficient for all. We hypothesized that a standardized multimodal postoperative analgesic regimen for the first five postoperative days including a potent opioid, OXY, would be at least as effective with regard to pain and total opioid requirement as IVM/oral codeine when given as adjunct to paracetamol + ibuprofen. Further, we hypothesized that this regimen would improve patient overall satisfaction without jeopardizing maternal or neonatal safety in terms of recognized opioid related adverse effects.

2 Materials and methods

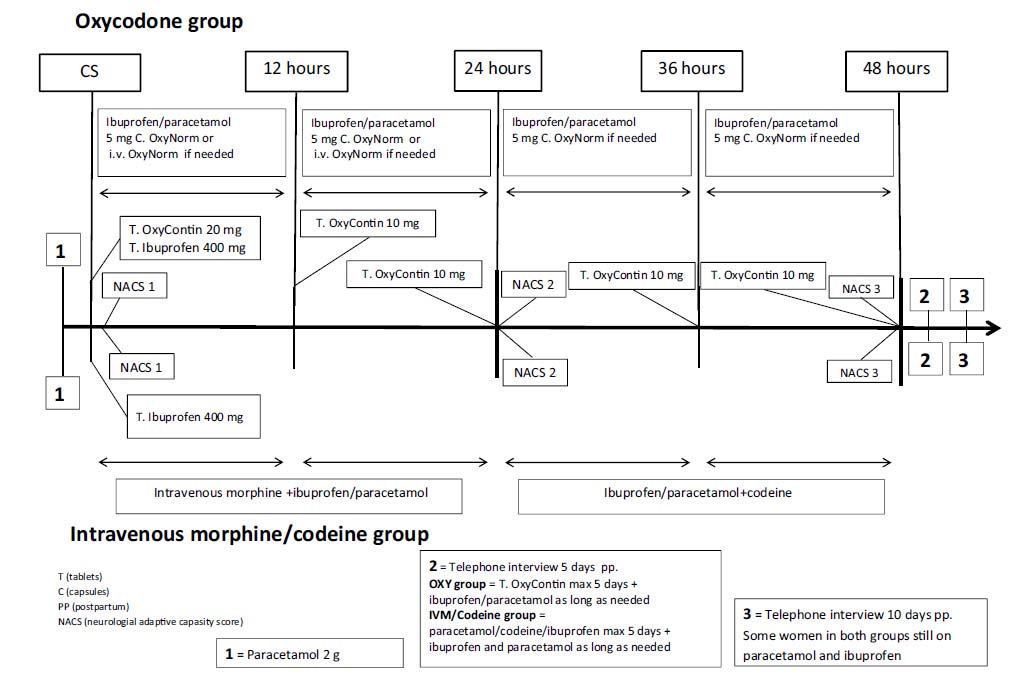

The present randomized open parallel group study in women undergoing planned CS was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm, Sweden (2010/1062-31/1) Swedish Medical Products Agency (151:2010/42559) and Eudra-CT (2010-018450). Healthy women, 18–50 years old, planned for CS from 38 full weeks of gestation, having the intention to breastfeed and who had sufficient understanding of the Swedish language, were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria included: ongoing participation in another clinical trial, treatment for chronic pain, drug abuse, mental illness, patients treated with antidepressants, known intolerance or allergy towards any of the study drugs, maternal disease that could affect pregnancy and foetal complications e.g. large for gestational age or intrauterine growth retardation. Eighty healthy women who met the inclusion criteria were recruited from November 2010 to August 2012 at Karolinska University Hospital, Sweden. After obtaining verbal and written informed consent patients were randomized using a computer-based program, in blocks of twenty. Each randomization number had a corresponding sealed-opaque envelope, containing study treatment information. Envelopes for each patient were drawn sequentially from a sealed box. The designated envelope was opened the day before CS by one of the investigators. The correct medication was prepared and ordained in the patient’s records. An open label design was chosen for ethical reasons, since we also collected samples for analyses of OXY exposure but chose not to do so for morphine/codeine. A timeline describes the study design (Fig. 1).

Timeline.

2.1 Study treatment

2.1.1 Treatment common for both groups

One hour preoperatively patients received 2 g oral paracetamol (Alvedon®, AstraZeneca, Sweden) as a bolus dose according to local routines. Spinal anaesthesia was administered using 1.8-2.6 ml (body height depending) bupivacaine (Marcain Tung® 5 mg/ml, AstraZeneca, Sweden) plus 15 μg (0.3 ml) fentanyl (Fentanyl® 50 μg/ml, Meda AB, Sweden) through a 27 G Sproutte spinal needle at L2–L3 or L3–L4 with the woman in sitting position. Immediately after surgery, before leaving the operating room, all patients received oral ibuprofen 400 mg (Brufen®, Abbott Laboratories, Sweden). During the rest of the hospital stay, and longer if needed, all patients continuously received 200 mg ibuprofen every 6 h. Oral paraffin emulsion (30 ml) was given twice daily to diminish constipation.

2.1.2 Postoperative treatment – oxycodone group

Before leaving the operating room, women received 20 mg long acting OXY (OxyContin®, Mundipharma, Sweden). Thereafter, 10 mg OxyContin® was given every 12 h for minimum 48 h. Rescue medication was given as an oral dose of 5 mg immediate release OXY (OxyNorm®, Mundipharma, Sweden). In the case of severe breakthrough pain, 1–5 mg of i.v. OXY (OxyNorm®, Mundipharma, Sweden); 10 mg/ml, 1 ml diluted with 9 ml saline solution (Natriumklorid 9 mg/ml, Fresenius, Sweden) were given. Occasionally, short acting OXY was given before mobilization. All patients in this group received 1 g oral paracetamol every 6 h until discharged, longer if needed.

2.1.3 Postoperative treatment – intravenous morphine/codeine group

For 24 h, morphine (Morfin MEDA® 10 mg/ml, MEDA, Sweden), diluted in saline (Natriumklorid 9 mg/ml, Fresenius, Sweden) was nurse-administered by slow i.v. injection until an adequate response, NRS<4/10, was obtained (if more than 10 mg the responsible physician was contacted). After 24 h, morphine and paracetamol were substituted by a combination treatment of paracetamol 500 mg plus codeine 30 mg (Citodon®, BioPhausia, Sweden), two tablets every 6 h for up to at least 48 h.

2.1.4 Postoperative days three to five

Upon discharge, approximately 48 h postoperatively, women received oral analgesics for up to five days postoperatively. Women in the OXY group received 10 mg OxyContin®, six tablets, to take as needed, twice daily. Women in the IVM/codeine group received Citodon®, maximum dose eight tablets per day. All patients were recommended to continue with paracetamol/ibuprofen when opioids were no longer required. In the IVM/codeine group, Citodon® was replaced by paracetamol.

2.2 Pain assessments

Patients reported their present pain intensity on a Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) (0–10, where 0 depicts “no pain” and 10 “worst pain imaginable”). Pain at rest was assessed every hour for 6 h and thereafter once every working shift (morning, afternoon and night) during the hospital stay. Provoked pain (during uterus palpation performed by the responsible midwife) was evaluated 6 times during 0–24 h postoperatively. Further, pain was assessed at request for rescue medication (maximum pain).

2.3 Mobilization

Three steps of postoperative mobilization were recorded: the woman standing next to the bed, walking in the room for the first time and being fully mobilized, i.e. back to circumstantially normal activities. Women received additional medication before mobilization if needed. Early mobilization was encouraged.

2.4 Opioid requirements

Opioid consumption was recorded and accumulated for 0–24 and 25–48 h as well as for the whole 5-day postoperative period.

All opioids were converted to oral OXY equivalents according to Table 1 [18].

Conversion rates for opioids used in the present clinical trial.

| Drug | Parenteral (mg) | Oral (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Codeine | NA | 200 |

| Morphine | 10 | 30 |

| Oxycodone | 10 | 20 |

-

Adapted according to McPherson [18]

2.5 Safety variables

Side effects of opioid exposure in the mothers were recorded based on spontaneous reporting and open questions. Signs of surgical site infections (SSI) were recorded and treated according to clinical routines. In the newborns, birth weight and weight development were recorded. At delivery, Apgar scores at 1, 5 and 10 min were recorded and umbilical cord blood was collected for acid-base analyses. All newborns were evaluated by one of the two authors (BN or CA) familiar with the Neurological and Adaptive Capacity Score (NACS) method [19]. The first evaluation, 30 min after delivery, was used as baseline. NACS was then assessed 24 and 48 h postpartum, to detect possible neurological symptoms due to opioid exposure. NACS is based on 20 criteria in five general areas: adaptive capacity, active and passive tone, primary reflexes and general observations (motor activity, alertness and crying). Each item is scored as 0, 1 or 2, adding up to a maximal total score of 40. Scores ≥35 indicates a healthy newborn. Other variables, e.g. increased bilirubin outside the normal range, need for additional feeding and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) were also recorded.

Maternal serum and breast milk samples for analysis of OXY and its metabolites were collected at 24 ( ± 4) and 48 ( ± 4) h postoperatively. Serum samples from the newborns were taken only at 48 ( ± 4) h, when samples for routine neonatal screening were also secured. These data will be published elsewhere.

2.6 Follow-up

On the day of discharge, all women completed a questionnaire concerning their pain experience. Questions related to satisfaction with pain relief, staffs acceptance of analgesic requirement, understanding of instructions regarding pain treatment and, if applicable, their postoperative pain compared to previous CS.

On postoperative day five, one of the investigators (BN or CA) contacted the women via telephone to determine opioid consumption since discharge. Ten days postoperatively a structured follow-up telephone interview was performed. Women were asked if they still experienced pain and in this case the location and type of pain. They were asked when they ended intake or if they still required analgesics. Questions also included pain interference with daily life, general postoperative recovery, perception of undergoing a CS and of the general care received.

2.7 Collection of data

Demographics and medical data, except pharmaceutical records, were collected from the computer based patient record system ObstetrixTM (Siemens, Sweden). Data concerning administration of drugs were secured from the computer based patient chart system Take CareTM (CompuGroup Medical, Sweden). The primary data collected were: woman’s age, weight and body mass index (BMI) at the time of surgery, indication for CS, parity and any previous CS. All data were codified and made anonymous before data entry.

2.8 Nursing aspects

All midwives in the maternity ward recorded the time spent administering analgesics (from time of request, preparing and administering the drug and evaluating the effect). The number of occasions when patients required supplementary pain relief and total time spent were recorded.

2.9 Statistical analysis

The primary outcome variable was pain at rest during the 48 h postoperative period. Main secondary variable was total opioid requirements during days 0–5. Other secondary variables were number of requests for rescue medication, pain upon request for rescue medication, time to mobilization, patient satisfaction and time to first defecation. Exploratory variables included time to administer analgesics and midwife global impression. Neonate safety variables included NACS, weight development and any aberrant observations regarding the newborns. Maternal safety variables included SSI and spontaneous report and open questions regarding any adverse effects.

The statistics software IBM PASW Statistics, version 18.0, was used to analyse differences between groups. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used when comparing NRS, opioid consumption and safety variables. For demographic data, interviews and questionnaires the Pearson’s Chi-Square test was used. A level of p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3 Results

Eighty patients were randomized and three patients were withdrawn before study treatment due to failed spinal block, two in the OXY group and one in the IVM/codeine group (Fig. 2). There were no significant differences between groups in demographic parameters (Table 2).

Demographics.

| Demographic | OXY group n - 38 | IVM/codeine group n - 39 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 33.5 (23–42) | 34.0 (21–44) |

| Gravida median (range) | 2.5 (1–6) | 3 (1–6) |

| Parity median (range) | 1 (0–4) | 1 (0–3) |

| Primiparas | n - 11 | n - 8 |

| Multiparas | n - 27 | n - 31 |

| Previous caesarean section | 0.5 (1–4) | 0.5 (1–3) |

| median (range) | n - 19 | n - 22 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 1 (1–4) | 1 (1–4) |

| (including CS), median (range) | n - 19 | n - 25 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 29.5 | 29.0 |

| median (range) | (22.3–43.7) | (24.2–52.5) |

| Education[a] | ||

| Compulsory school | n - 1 | n - 1 |

| Senior high school | n - 11 | n - 17 |

| University | n - 23 | n - 20 |

| Postgraduate | n - 2 | n - 1 |

| Missing | n - 1 | n - 0 |

Flowchart.

3.1 Pain intensity

Mean pain at rest was significantly lower in the OXY group at 0–6 h, 25–48 h and when asking for rescue medication 0–24 h. When evaluating the whole 0–24 h period no significant difference between groups was observed. Provoked pain (uterus palpation) was significantly less in the OXY group during the first 6 h (Table 3).

Pain (NRS) at rest, maximum pain, provoked painand numberofrescue medications.

| Variable | OXY group n - 38 | IVM/codeine group n - 39 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain at rest | |||

| 0–6h | 3.80 ± 1.52 | 4.96 ± 1.49 | 0.002 |

| 0–24h | 3.43 ± 1.74 | 3.93 ± 1.30 | n.s |

| 25–48 h | 2.89 ± 1.88 | 3.80 ± 1.83 | 0.039 |

| Provoked pain (uterus palpation) | |||

| 0–6h | 3.26 ± 2.13 | 4.60 ± 2.10 | 0.007 |

| 0–24h | 5.98 ± 2.13 | 6.62 ± 2.02 | n.s |

| Maximum pain intensity (when asking for rescue medication) | |||

| 0–24h | 5.41 ± 2.17 | 6.42 ± 1.61 | 0.027 |

| Number of rescue medications | |||

| 0–24h | 4.3 ± 3.6 | 8.4 ± 11.7 | 0.047 |

-

All data are shown as mean ± SD (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant)

3.2 Opioid requirements

There were no significant differences in opioid consumption during the first 24 h postoperatively. However, during the 25–48 h period and from 49 h until 5 days postoperatively there was significantly less opioid consumption in the OXY group than in the IVM/codeine group (Table 4). The need for rescue medication during the first 24 h was less frequent in the OXY than in the IVM/codeine group (Table 3). As a standardized conversion table was used for opioid calculations these data to some extent represent an approximation.

Amount ofopioids in oxycodone equivalents (mg).

| OXY groupn - 38 | IVM/codeine groupn - 39 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–24h | 49.5 ± 20.1 | 45.4 ± 24.2 | n.s |

| 25–48 h | 31.5 ± 9.6 | 38.2 ± 11.6 | 0.001 |

| 49 h–5 days | 27.7 ± 15.5 | 54.7 ± 26.1 | 0.001 |

| 0–5 days | 108.7 ± 37.6 | 138.2 ± 45.1 | 0.002 |

-

All data are shown as mean ± SD (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant)

3.3 Postoperative recovery

There was no difference in mobilization between groups. Women in the OXY group had a significantly shorter time period until first bowel movement (Table 5).

Variables related to postoperative mobilization.

| Variable | OXY group n - 38 | IVM/codeine group n - 39 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stand next to the bed (h) | 9.6 ± 4.9 (4–25) | 11.9 ± 6.2 (5–26.5) | n.s |

| Walking around with help (h) | 16.8 ± 9.1 (5–47) | 20.1 ± 8.4 (5–44) | n.s |

| Fully mobilized (h) | 24.3 ± 11.4 (5–53) | 30.6 ± 17.7 (5–67) | n.s |

| First bowel movement (postop day) | 2.9 ± 1.4 (1–7) | 3.6 ± 1.2 (1–6) | 0.038 |

| Discharge from hospital (postopday) | 2.4 ± 0.6 (2–3) | 2.4 ± 0.6 (2–5) | n.s |

-

All data are shown as mean ± SD (range) (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant)

3.4 Telephone interview at ten days

Women in the OXY group reported pain to be less of an obstacle than women in the IVM/codeine group (79% vs. 51%). On postoperative day 10, analgesics requirements were low and similar between groups (Table 6).

Telephone interview 10 days postoperatively.

| Variable | OXY group (n - 38) | IVM/codeine group (n - 39) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wellbeing | |||

| Very good/good | 38 (100%) | 35 (87%) | n.s |

| Less good/bad | 0 | 4 (13%) | |

| Scar pain | |||

| Yes | 3 (8%) | 7 (18%) | n.s |

| No | 23 (60%) | 19 (49%) | |

| Only when moving | 12 (32%) | 13 (33%) | |

| Still on pain medication | |||

| Yes | 13 (34%) | 14 (36%) | n.s |

| No | 18 (48%) | 15 (38%) | |

| Only occasionally | 7 (18%) | 10 (26%) | |

| Has pain been an obstacle in your everyday life | |||

| Yes | 8 (21%) | 19 (49%) | 0.011 |

| No | 30 (79%) | 20 (51%) | |

| Has pain eased in expected time | |||

| Yes/much faster | 36 (95%) | 35 (90%) | n.s |

| No | 2 (5%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Rate your perception of the hospital stay | |||

| Very positive/positive | 37 (97%) | 36 (92%) | n.s |

| Negative/very negative | 0 | 1 (3%) | |

| Neither positive or negative | 1 (3%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Rate your perception undergoing a caesarean section | |||

| Very positive | 29 (76%) | 26 (67%) | n.s |

| Positive | 9 (24%) | 13 (33%) | |

-

Numbers and (%) (Chi2 test, p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant)

3.5 Safety variables

Maternal: There were two SSIs reported in each group. Three women in the OXY group reported adverse effects (0–24 h) vs. 15 women in the IVM/codeine group (p = 0.007). In the OXY group three women felt dizziness when receiving i.v. injections of OXY. In the IVM/codeine group the following symptoms were reported: dizziness (n = 9), nausea (n = 4), being tired (n = 1) and itching (n = 4).

Neonates: Apgar scores and umbilical cord pH were normal in all but three newborns.

These three newborns (two in the OXY and one in the IVM group) had acidosis (pH <7.20) and were admitted to the NICU already at the NACS baseline assessment. All three developed pulmonary adaptation syndrome (PAS). One newborn from the IVM group was admitted to the neonatal ward when 24 h old, also due to PAS. For all mothers, treatment continued according to plan. No newborns with signs of opioid exposure were identified. No significant difference in weight loss was recorded (Table 7).

Neonatal variables.

| Baseline values (before intervention) | Neonatal outcome with mothers in the OXY group (n - 38) | Neonatal outcome with mothers in the IVM/codeine group n - 39) |

|---|---|---|

| Apgar score (median and range) | ||

| 1 min | 9 (6–10) | 9 (7–10) |

| 5 min | 10 (8–10) | 10 (8–10) |

| 10 min | 10 (8–10) | 10 (8–10) |

| Umbilical cord blood pH (mean ± SD) | 7.32 ± 0.62[a] | 7.32 ± 0.06[b] |

| Birth weight (mean ± SD) | 3561 ± 387 | 3559 ± 370 |

| NACS[c] (mean ± SD) <60 min, OXY n - 38, IVM n - 39 | 35.8 ± 2.6 | 35.7 ± 3.2 |

| Neonatal care admission (n) | 2 | 2 |

| NACS[c] (mean ± SD) 24 h, OXY n - 36, IVM n - 38 | 37.2 ± 1.7 | 37.2 ± 1.8 |

| 48 h, OXY n - 35, IVM/codeine n - 38 Missing OXY n- 1 | 37.5 ± 1.7 | 37.8 ± 1.6 |

| Number of neonates decreasing >10% in weight (n) | 5 | 10 |

| Additional feeding (n and %) | ||

| No | 28 (74%) | 23 (59%) |

| Yes | 10 (26%) | 16 (41%) |

3.6 Patient global impression (PCI)

In the OXY group, 16/19 women with previous CS experience, judged the present occasion to be less painful, while three judged it as similar. In the IVM/codeine group, 11/20 women with previous CS judged pain as less, eight judged it as similar and one as worse this time. Ten women (four in the OXY group and six in the IVM/codeine group) reported unsatisfactory pain relief. Despite this all women told that they gained support for their reported need for pain relief.

3.7 Nursing aspects

Total time (min) required for rescue treatment during the first 24 h was significantly (p = 0.001) shorter in the OXY group (20.7 ± 19.4) than in the IVM/codeine group (66.4 ± 38.7). Also the number of rescue medications was significantly lower (p = 0.047) in the OXY group (4.3 ± 3.6) than in the IVM/codeine group (8.4 ± 11.7).

4 Discussion

The present study results demonstrate that a postoperative treatment regimen using an oral formulation of a potent opioid (OXY) was more effective in reducing both pain and as opioid requirement during the postoperative period after CS, when compared with our standard of care, IVM and oral codeine, both as adjunct to paracetamol + ibuprofen. Although pain at rest was lower in the OXY group during the first 6 h no significant difference was seen over the whole 0–24 h period and neither did opioid consumption differ between groups. It is reasonable to expect that these observations are due to the fact that a higher dose of opioid was administered to the OXY patients than to the IVM patients immediately after surgery, but that all patients got an adequate dose when asking for medication, which is consistent with the fact that total opioid consumption was almost identical. However, during the following days, lower pain intensity as well as lower opioid requirement was demonstrated in the OXY group.

Incisional pain is shown to be most intense during the first 24 h after surgery, while deep visceral pain is of longer duration. Further Lenz and coworkers suggest OXY as more potent in visceral pain than morphine, which may contribute to the differences observed [20].

Both frequency and intensity of breakthrough pain (0–24 h) were lower in the OXY than in the IVM/codeine group. The pharmacokinetic profile of slow release OXY (OxyContin) ensures that there are no sudden dips in drug exposure and thereby reduces the risk of break-through pain. The lower total need for opioids, less frequent need for rescue medication, shorter total time for drug administration and less opioid related adverse effects in the mothers of the OXY group further demonstrate the advantages of this protocol. There is conflicting data regarding the comparison of adverse effects between OXY and morphine [14,20] but several studies suggest a better tolerability of OXY at equipotent doses [21, 22, 23, 24].

In the present study the median duration of OXY or codeine intake was the same across groups. OXY was given up to five days after surgery, with doses days four and five of maximum 20 mg, limiting the risk for significant influence on the neonate. Due to the interindividual differences in bioactivation of codeine the total opioid exposure of the neonate in the group receiving IVM/codeine can be expected to vary even more than what has been suggested for OXY [17].

There are some limitations with the present study. First, it can be considered a weakness that PCA morphine was not used as comparator. However, the objective of the study was not to assess the analgesic efficacy of oxycodone, but to compare two alternative low tech treatment analgesic regimens in order to optimize the effectiveness of postoperative care after CS. PCA has never been introduced as routine treatment in our hospital as quick mobilization is central and we made the assessment that transportation of a PCA devise would make the mothers less ambulatory when taking care of their newborns. The intention with the study was to evaluate if change of opioid could optimize pain management. Second, the study design is not double-blind. One major reason for this is the ethical aspect of obtaining samples of blood from the newborn as well as breast milk during the very first days of lactation. We wanted to do this in as few patients as possible, limiting sampling to the OXY group, since there is less data available for this opioid. It is important to emphasize that mothers’ had no opportunity to influence treatment allocation and no-one withdrew because of this sampling. Third, pain intensity assessments reported at regular intervals were only obtained for 48 h postoperatively, which is when mothers and babies were discharged, according to clinical routine. Thus, pain intensity data and analgesic requirement data for days 3–5 are not as robust. Fourth, we did not do any CYP2D6 pharmacogenomics analyses, and therefore some women in the IVM/codeine group might have been slow metabolizers, not responding to codeine, affecting their response to treatment. Using a standardized conversion table for opioid calculations also contributes to some uncertainty in the final evaluation.

No adverse effects of treatment on the newborns were observed in either group. Based on NACS assessments no child showed any sign of influence of the mother’s intake of opioid analgesics.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first time OXY as pain relief after CS has been compared to another regime with regard not only to efficiency and safety of postoperative analgesia of the mothers but also by a quantified evaluation of postnatal adaptation in connection to breastfeeding. The NACS has been questioned as a reliable tool, with a low test-retest reliability in detecting differences between neonatal outcomes after different types of obstetric anaesthesia for CS [25]. However, there is a general lack of better tools. We considered that supervised training of only two study raters by an expert neonatologist has optimized this tool for the present use.

The strength of our study is that it is prospective and that there was a high compliance among the women participating in the study. A previous retrospective cohort study by Lam et al. reported a higher incidence of central nervous system symptoms in breast fed newborns by mothers treated with OXY than mothers treated with paracetamol or codeine [26]. As pointed out in a reply to the study by Lam, the long recall time was a pronounced weakness of that study [27]. Studies prospectively examining how OXY affects the breastfed infant have been requested [28].

Seaton et al. studied maternal serum and breast milk levels after OXY intake and transport through breast milk to the neonate was investigated. OXY was only detected in the plasma of one neonate (out of 41) but it was considered possible that the levels in breast- milk could expose the nursing neonate to more than 10% of the therapeutic infant dose [17,29]. The need for opioids is highest during the first postoperative day, and decreases over time. During the first 24 h the normal range of breast milk transfer is only 4–6 ml/kg infant body weight [30]. An optimized dosing of analgesics, including opioids, during the first 24 h after delivery, when breast milk production is still sparse, resulting in a lower maternal requirement of opioid during day 2–5 post CS, may clearly reduce the risk of untoward exposure of the newborn, whilst the mother is optimally pain relieved. The longer period to established lactation after CS than after vaginal delivery, contributes to low child exposures, with only small amounts of opioids being transferred to the baby.

In summary, the present prospective study demonstrates that a standardized postoperative treatment with oral OXY after CS provided a better pain control, with overall lower pain intensity and lower opioid intake than a protocol using IVM/codeine, both as components of a multimodal analgesic regime. Neither did the low tech approach, supporting early ambulation, demonstrate any safety concerns for mother and child. Further, an effective and reliable oral standardized dosing of postoperative analgesics can contribute to the self-sufficiency of the mother in self-care and care of the newborn.

Highlights

Oral OXY - better post-caesarean section pain control vs. nurse-administered i.v. morphine/oral codeine.

Oral OXY - less opioid consumption with oxycodone vs. i.v. morphine/oral codeine.

Oral OXY - less time consuming than giving i.v. morphine during the first 24h.

Both treatment protocols are safe for both the mother and the newborn.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2015.01.007.

-

Conflict of interest

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the women contributing to this study and to the staff at the maternity ward K77 at the Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, Sweden for all valuable help. We are also thankful for the expert instructions regarding the NASC evaluation that we received from Professor Mikael Norman, at the NICU, Department of Pediatrics, Karolinska University Hospital. The study was supported by a grant from the Stockholm County Council (grant no. 2006023) and funding from Sophiahemmet University, Stockholm. Mundipharma provided financial support for the OXY analyses at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge.

References

[1] Karlstrom A, Engstrom-Olofsson R, Norbergh KG, Sjoling M, Hildingsson I. Postoperative pain after cesarean birth affects breastfeeding and infant care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2007;36:430–40.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS, Gan TJ. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg 2003;97:534–40 [table of contents].Search in Google Scholar

[3] Kuczkowski KM. Postoperative pain control in the parturient: new challenges in the new millennium. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;24: 301–4.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Aiono-Le Tagaloa L, Butwick AJ, Carvalho B. A survey of perioperative and postoperative anesthetic practices for cesarean delivery. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2009;2009:510642.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Lavoie A, Toledo P. Multimodal postcesarean delivery analgesia. Clin Perinatol 2013;40:443–55.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Toms L, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) with codeine for postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009:CD001547.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002;183:630–41.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Buvanendran A, Kroin JS. Multimodal analgesia for controlling acute postoperative pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009;22:588–93.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Snell P, Hicks C. An exploratory study in the UK of the effectiveness of three different pain management regimens for post-caesarean section women. Midwifery 2006;22:249–61.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kirchheiner J, Schmidt H, Tzvetkov M, Keulen JT, Lotsch J, Roots I, Brockmoller J. Pharmacokinetics of codeine and its metabolite morphine in ultra-rapid metabolizers due to CYP2D6 duplication. Pharmacogenomics J 2007;7: 257–65.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Ingelman-Sundberg M. Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6): clinical consequences, evolutionary aspects and functional diversity. Pharmacogenomics J 2005;5:6–13.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Madadi PRC, Hayden MR, Carleton BC, Gaedigk A, Leeder JS, Koren G. Pharmacogenetics of neonatal opioid toxicity following maternal use of codeine during breastfeeding: a case-control study. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;85:31–5.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Koren G, Cairns J, Chitayat D, Gaedigk A, Leeder SJ. Pharmacogenetics of morphine poisoning in a breastfed neonate of a codeine-prescribed mother. Lancet 2006;368:704.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Kalso E, Vainio A. Morphine and oxycodone hydrochloride in the management ofcancer pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1990;47:639–46.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Lauretti GR, Oliveira GM, Pereira NL. Comparison of sustained-release morphine with sustained-release oxycodone in advanced cancer patients. Br J Cancer2003;89:2027–30.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Kalso EVA. Morphine and oxycodone hydrochloride in the management of cancer pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1990;47:639–46.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Seaton S, Reeves M, McLean S. Oxycodone as a component of multimodal analgesia for lactating mothers after caesarean section: relationships between maternal plasma, breast milk and neonatal plasma levels. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2007;47:181–5.Search in Google Scholar

[18] McPherson M. Demystifying opoid conversion calculations:aguide for effective dosing. USA: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Amiel-Tison C, Barrier G, Shnider SM, Levinson G, Hughes SC, Stefani SJ. A new neurologi and adaptive capacity scoring system for evaluating obstetric medications in full-term newborns. Anesthesiology 1982;56:340–50.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Lenz H, Sandvik L, Qvigstad E, Bjerkelund CE, Raeder J. A comparison of intravenous oxycodone and intravenous morphine in patient-controlled postoperative analgesia after laparoscopic hysterectomy. Anesth Analg 2009;109:1279–83.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Gaskell H, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral oxycodone and oxycodone plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009:CD002763.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Heiskanen T, Kalso E. Controlled-release oxycodone and morphine in cancer related pain. Pain 1997;73:37–45.Search in Google Scholar

[23] KantorTG, Hopper M, Laska E. Adverse effects of commonly ordered oral nar- cotics.J Clin Pharmacol 1981;21:1–8.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Davis KM, Esposito MA, Meyer BA. Oral analgesia compared with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia for pain after cesarean delivery: a randomized controlledtrial. AmJ Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:967–71.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Halpern SH, Littleford JA, Brockhurst NJ, Youngs PJ, Malik N, Owen HC. The neurologic and adaptive capacity score is not a reliable method of newborn evaluation. Anesthesiology 2001;94:958–62.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Lam J, Kelly L, Ciszkowski C, Landsmeer ML, Nauta M, Carleton BC, Hayden MR, Madadi P, Koren G. Central nervous system depression of neonates breastfed by mothers receiving oxycodone for postpartum analgesia. J Pediatr 2012;160, 33–7.e2.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Rivers CM, Olsen D, Nelson LS. Breastfeeding and oxycodone. J Pediatr 2012;161:174 [author reply 174].Search in Google Scholar

[28] van den Anker JN. Is it safe to use opioids for obstetric pain while breastfeeding? J Pediatr 2012;160:4–5.Search in Google Scholar

[29] ItoS. Drug therapy for breast-feeding women. N Engl J Med 2000;343:118–26.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Evans KC, Evans RG, Royal R, Esterman AJ, James SL. Effect of caesarean section on breast milk transfer to the normal term newborn over the first week of life. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2003;88:F380–2.Search in Google Scholar

© 2015

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- The importance of studying personality traits and pain in the oldest adults

- Clinical pain research

- The influence of personality traits on perception of pain in older adults – Findings from the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care – Blekinge study

- Editorial comment

- Sinomenine is a promising analgesic and antihyperalgesic for pain and hypersensitivity in rheumatoid arthritis

- Original experimental

- Sinomenine alleviates mechanical hypersensitivity in mice with experimentally induced rheumatoid arthritis

- Editorial comment

- Oral immediate and prolonged release oxycodone for safe and effective patient controlled analgesia after surgery Can opioid for acute postoperative pain be improved by adding a peripheral opioid antagonist?

- Clinical pain research

- Oral oxycodone for pain after caesarean section: A randomized comparison with nurse-administered IV morphine in a pragmatic study

- Editorial comment

- Nitrous oxide in oxygen (50:50) is analgesic that requires optimal inhalation procedure

- Clinical pain research

- Nitrous oxide analgesia for bone marrow aspiration and biopsy – A randomized, controlled and patient blinded study

- Editorial comment

- Ketamine has anti-hyperalgesic effects and relieves acute pain, but does not prevent persistent postoperative pain (PPP)

- Systematic review

- Intra- and postoperative intravenous ketamine does not prevent chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Editorial comment

- Raising the standards of preclinical pain studies

- Topical review

- Experimental design and reporting standards for improving the internal validity of pre-clinical studies in the field of pain: Consensus of the IMI-Europain consortium

- Editorial Comment

- Single cases are complex Illustrated by Flink et al. ‘Happy despite pain: A pilot study of a positive psychology intervention for patients with chronic pain’

- Clinical pain research

- Happy despite pain: Pilot study of a positive psychology intervention for patients with chronic pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- The importance of studying personality traits and pain in the oldest adults

- Clinical pain research

- The influence of personality traits on perception of pain in older adults – Findings from the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care – Blekinge study

- Editorial comment

- Sinomenine is a promising analgesic and antihyperalgesic for pain and hypersensitivity in rheumatoid arthritis

- Original experimental

- Sinomenine alleviates mechanical hypersensitivity in mice with experimentally induced rheumatoid arthritis

- Editorial comment

- Oral immediate and prolonged release oxycodone for safe and effective patient controlled analgesia after surgery Can opioid for acute postoperative pain be improved by adding a peripheral opioid antagonist?

- Clinical pain research

- Oral oxycodone for pain after caesarean section: A randomized comparison with nurse-administered IV morphine in a pragmatic study

- Editorial comment

- Nitrous oxide in oxygen (50:50) is analgesic that requires optimal inhalation procedure

- Clinical pain research

- Nitrous oxide analgesia for bone marrow aspiration and biopsy – A randomized, controlled and patient blinded study

- Editorial comment

- Ketamine has anti-hyperalgesic effects and relieves acute pain, but does not prevent persistent postoperative pain (PPP)

- Systematic review

- Intra- and postoperative intravenous ketamine does not prevent chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Editorial comment

- Raising the standards of preclinical pain studies

- Topical review

- Experimental design and reporting standards for improving the internal validity of pre-clinical studies in the field of pain: Consensus of the IMI-Europain consortium

- Editorial Comment

- Single cases are complex Illustrated by Flink et al. ‘Happy despite pain: A pilot study of a positive psychology intervention for patients with chronic pain’

- Clinical pain research

- Happy despite pain: Pilot study of a positive psychology intervention for patients with chronic pain