The dynamics of the pain system is intact in patients with knee osteoarthritis: An exploratory experimental study

-

Tanja Schjødt Jørgensen

Abstract

Background and aims

Despite the high prevalence of knee osteoarthritis (OA) it remains one of the most frequent knee disorders without a cure. Pain and disability are prominent clinical features of knee OA. Knee OA pain is typically localized but can also be referred to the thigh or lower leg. Widespread hyperalgesia has been found in knee OA patients. In addition, patients with hyperalgesia in the OA knee joint show increased pain summation scores upon repetitive stimulation of the OA knee suggesting the involvement of facilitated central mechanisms in knee OA. The dynamics of the pain system (i.e., the adaptive responses to pain) has been widely studied, but mainly from experiments on healthy subjects, whereas less is known about the dynamics of the pain system in chronic pain patients, where the pain system has been activated for a long time. The aim of this study was to assess the dynamics of the nociceptive system quantitatively in knee osteoarthritis (OA) patients before and after induction of experimental knee pain.

Methods

Ten knee osteoarthritis (OA) patients participated in this randomized crossover trial. Each subject was tested on two days separated by 1 week. The most affected knee was exposed to experimental pain or control, in a randomized sequence, by injection of hypertonic saline into the infrapatellar fat pad and a control injection of isotonic saline. Pain areas were assessed by drawings on anatomical maps. Pressure pain thresholds (PPT) at the knee, thigh, lower leg, and arm were assessed before, during, and after the experimental pain and control conditions. Likewise, temporal summation of pressure pain on the knee, thigh and lower leg muscles was assessed.

Results

Experimental knee pain decreased the PPTs at the knee (P <0.01) and facilitated the temporal summation on the knee and adjacent muscles (P < 0.05). No significant difference was found at the control site (the contralateral arm) (P =0.77). Further, the experimental knee pain revealed overall higher VAS scores (facilitated temporal summation of pain) at the knee (P < 0.003) and adjacent muscles (P < 0.0001) compared with the control condition. The experimental knee pain areas were larger compared with the OA knee pain areas before the injection.

Conclusions

Acute experimental knee pain induced in patients with knee OA caused hyperalgesia and facilitated temporal summation of pain at the knee and surrounding muscles, illustrating that the pain system in individuals with knee OA can be affected even after many years of nociceptive input. This study indicates that the adaptability in the pain system is intact in patients with knee OA, which opens for opportunities to prevent development of centralized pain syndromes.

1 Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a common chronic disease, with pain, disability, and structural degeneration as clinical hallmarks [1,2]. Knee OA pain is typically localized but can also be referred to the thigh or lower leg. Localized pain sensitivity is associated with alterations in the peripheral pain processing, whereas widespread pain sensitivity is associated with dysfunction in the central pain processing [3]. Widespread hyperalgesia has been found in knee OA patients [3,4,5,6]. Suggested mechanisms for widespread hyperalgesia include hyperexcitability of dorsal horn neurons due to extensive noxious input from the joint resulting in enhanced responses and lower excitation threshold in high-threshold neurons [2,7,8]. Furthermore, the neurons begin to show increased responses to stimuli applied to regions adjacent to and remote from the joint, and the total receptive field can be enlarged [2,7,8]. Other features of facilitated central mechanisms (widespread hyperalgesia), where the central integrative mechanisms is up-regulated [8], include increased temporal and spatial summation of pain [9]. Patients with hyperalgesia in the OA knee joint show increased pain summation scores upon repetitive stimulation of the OA knee [10] and tibialis anterior muscle compared with controls [4] suggesting the involvement of facilitated central mechanisms in knee OA [11].

Interestingly, experimental knee pain in healthy subjects leads to similar widespread hyperalgesia and facilitated temporal summation [12]. In knee OA patients, total knee replacement reduces the knee hyperalgesia and sensitization phenomena [13], which indicate that pain elicited from intra-articular structures is involved in generation and maintenance of both local and widespread hyperalgesia.

The dynamics of the pain system (i.e., the adaptive responses to pain) has been widely studied, but mainly from experiments on healthy subjects, whereas less is known about the dynamics of the pain system in chronic pain patients, where the pain system has been activated for a long time. Knee OA is associated with increased pain sensitivity, but it is unknown whether the pain system in a chronic pain population behaves similarly to experimentally induced knee pain as healthy subjects. In healthy subjects experimental knee pain demonstrated hyperalgesia and facilitated temporal summation in the knee and in muscles located distant to the injection site [12]. The purpose of this study was to assess the dynamics of the nociceptive system in a chronic pain population. Peripheral and central pain sensitizations mechanisms in knee OA patients were assessed after induction of experimental knee pain. It was hypothesized that localized and widespread hyperalgesia together with the degree of temporal summation of pressure pain will be facilitated when inducing experimental knee pain in patients with knee OA.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

This study included participants with knee OA diagnosed according with the ACR criteria [14], average daily knee pain over the last week (peak pain > 3 rated on a verbal rating scale 0-10), and radiographic evidence of knee OA on a standard anterior-posterior weight-bearing radiogram. Exclusion criteria included polyneuropathy, total hip and knee replacements, low back pain, corticosteroid injections in the previous 3 months, and nerve root compression syndromes. Furthermore, the patients were requested to withhold any analgesics 24 h before the test days. A total of 64 knee OA patients were screened for the study, of which 10 consecutive patients agreed to participate. Of the 64 screened patients, 25 were eligible for study participation, yet only 10 patients accepted the invitation to participate. The main reason for declining participation was concerns about the experimental pain. There were no statistical difference between those who participated and those who declined with respect to person characteristics.

All participants were given oral and written information and written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to inclusion in the study. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (HC-2007-0053) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) questionnaire was applied at the initial visit. KOOS is a disease-specific, self-administered health-status measure, which assesses five indicators: Pain, Symptoms, Function, Sport and recreation function, and Knee-related quality of life. Standardized answer options are given (5 Likert boxes) and each question was scored from 0 to 4. A normalized score (100 indicating best condition and 0 indicating worst condition) was calculated for each subscale [15].

2.2 Protocol

The study was designed as a randomized crossover trial, with each subject tested on two days separated by 1 week. The study was designed to assess differences in the changes in pain sensitivity after an injection with hypertonic saline as compared to an injection of isotonic saline. Pain was induced in the infrapatellar fat pad by injection of hypertonic saline on one test day, with isotonic saline as control on the other test day (sequence randomized). Pain intensity, pressure pain thresholds (PPTs), temporal summation of pressure pain, and pain distributions were assessed on three occasions: before, during experimental pain/control injections (after approx. 30–60 s including a period with moderate pain), and when pain had vanished (after; approximately 20 min after latest measurement).

PPTs were assessed on the knee, thigh, lower leg, and arm. Furthermore, temporal summation of pressure pain was assessed on the same sites except for the arm. Manual and computer controlled pressure algometry were used [12,16].

2.3 Experimental knee pain

Experimental pain was induced by bolus injections of 1 ml hypertonic saline (5.8%) into the infrapatellar fat pad and isotonic saline (1 ml, 0.9%) was used in the control session [12,17,18]. The injections were ultrasound guided. The participants rated the pain intensity verbally every 30 s on an NRS with 0 representing ‘no pain’, and 10 representing ‘maximal pain’. The maximal NRS score were extracted. After the experimental pain had vanished the participants were asked to mark the experimentally evoked pain areas on an anatomical map.

2.4 Manual pressure algometry

A hand-held pressure algometer (Algometer Type II, Somedic AB, Sweden) was used to assess manual pressure pain thresholds (PPT). The pressure was applied with a 1 cm2 probe and at a rate of approximately 30 kPa/s ensured by visual feedback from the algometer to the assessor. Participants were instructed to push a button when they felt that the pressure was just barely painful. PPT was measured twice at each visit and each trial. Both measurements were used in the statistical analysis. An interval of minimum 20 s was kept between each PPT assessment.

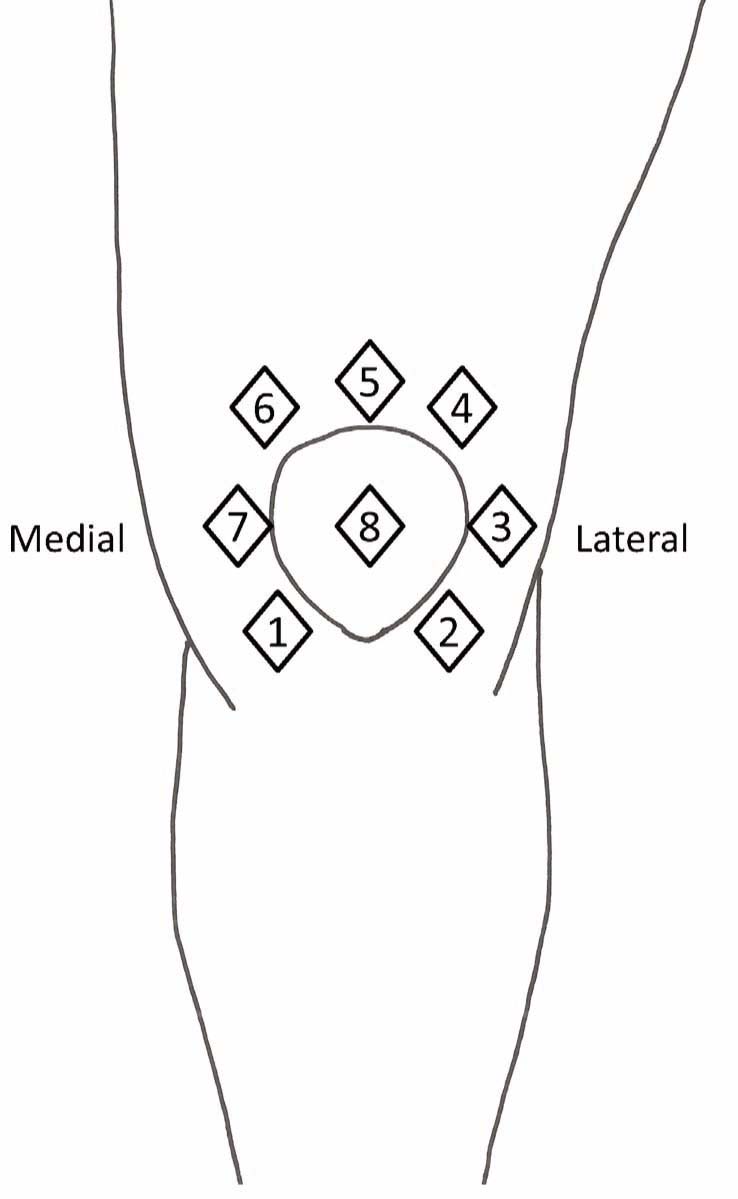

PPT was recorded from 8 sites around the injected knee (Fig. 1 ), two sites outside the knee and one contralateral control site. The eight sites on the knee were located in relation to bony landmarks. Site 1: 2 cm distal to the inferior medial edge of patella (saline injection site). Site 2: 2 cm distal to the inferior lateral edge of patella.

The eight assessment sites around the injected knee.

Site 3: 3 cm lateral to the midpoint on the lateral edge of patella; site 4: 2 cm proximal to the superior lateral edge of patella. Site 5: 2 cm proximal to the superior edge of patella. Site 6: 2 cm proximal to the superior medial edge of patella. Site 7: 3 cm medial to the midpoint on the medial edge of patella; site 8: at centre of patella. Two additional sites were located outside the knee on the vastus lateralis muscle (7 cm from the lateral upper rim of patella) and on the tibialis anterior muscle (10 cm below tibial tuberosity). The contralateral m. extensor carpi radialis longus, 5 cm distal to lateral epicondyle of the humerus, was used as a control site.

2.5 Temporal summation of pressure pain measured

A computer-controlled pressure algometer (Aalborg University, Denmark) was used for measuring computer-controlled PPT and temporal summation of pressure pain at three sites (site 1 on the knee, m. vastus lateralis, and m. tibialis anterior). The computer-controlled pressure algometer applied the mechanical stimuli perpendicular to the skin surface [19]. A circular aluminium probe with a padded contact surface of 1 cm2 was fixed to the tip of a piston. The pressure stimulation was feedback controlled via recordings of the actual force. The computer controlled pressure stimulus, with an ascending pressure gradient of 60 kPa/s, was applied continuously until the subject reported pain by pressing a button. This pressure intensity was defined as the computer-controlled PPT which was recorded three times for each assessment site.

Temporal summation of pain was assessed based on a methodology frequently used for temporal summation of pressure-induced pain [4,8,9,19,20, 21,22, 23, 24,25]. It allows for the measurement of stimulus -response functions that relate the pressure intensity with the pain response [19,21]. In response to a sequence of somatosen-sory stimuli with the same intensity, the progressive increase in pain perception is defined as the temporal summation of pain, which mimics the initial phase of the wind-up process [8,22]. The appropriate conditions for the assessment of temporal summation are sufficiently short intervals between repeated stimuli of constant strength (such as 10 stimuli at 1 s inter-stimulus intervals) [4,20,22,23].

In the present study temporal summation of pain was assessed by sequential stimulation consisting of 10 pressure stimuli (1s duration and 1 s interval) at the PPT level. The intensity of sequential stimulation was the average of the three computer-controlled PPT as described above.

For each site the model was repeated twice. The sequential stimulation was applied randomly to the three assessment sites with a 1-min interval in-between. Skin contact between the repeated pressure stimuli was ensured by keeping a constant force of 10 kPa, which does not evoke pain. The participants rated the pain intensity continuously during the sequential stimulation on an electronic visual analogue scale (VAS) where 0 cm and 10 cm were anchored to ‘no pain’ and ‘maximal pain’, respectively. The VAS signal was sampled by a computer at 200 Hz. VAS scores were extracted immediately after the individual stimulations (i.e. 10 VAS scores were analyzed after sequential stimulation). The VAS scores were normalized to the first stimulus VAS score by subtraction.

2.6 Statistics

This study was designed to assess differences in pain sensitivity in patients with knee OA after an injection of hypertonic saline as compared to an injection of isotonic saline. The data are presented as mean, standard deviation (SD), standard error of the mean (SEM) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). For each variable a longitudinal data model was applied to assess multiple repeated-measures on the same subject using the MIXED procedure of the SAS® system with random effect for subject (random intercept model). The analyses focused on the fixed effects analyses, analysing whether there were Sequence × Saline interactions (Sequence: Before, During, After injection; Saline: Hypertonic, Isotonic) and the corresponding main effects. In case of significant interactions post hoc tests were used to explore the pair-wise differences comparing saline solutions before, during and after injection. The analysis of temporal summation used the same repeated measures mixed model and focused on the sequence × saline × stimulation number interaction with corresponding main effects. To assess for carry-over effects the analyses were done with the randomization order added as a covariate. Statistical significance accepted at P< 0.05.

Despite multiple tests, no statistical adjustments were applied, as this study is exploratory and we had no a priori assumptions on which or how many of the sites that would react to the experimental pain, wherefore unadjusted P-values are reported.

3 Results

Characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline.

| Mean (SD) | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.4±5.9 | 51.0 | 71.0 |

| Height, cm | 171.4 ±8.6 | 158.9 | 185.6 |

| Weight, kg | 87.6 ± 18.1 | 59.6 | 116.7 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2 ) | 29.5 ± 4.6 | 20.2 | 35.0 |

| Disease duration, years | 11.9 ±7.2 | 1 | 27 |

| Female/males | 9/1 | ||

| KL scores, 1–4 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| KOOS scores | |||

| Pain, 0–100 | 55.6 ± 13.8 | 33.3 | 75.0 |

| Symptoms, 0–100 | 44.0 ± 15.5 | 8.3 | 58.3 |

| Activity of daily living, 0–100 | 62.6 ± 12.1 | 38.2 | 83.8 |

| Quality of life, 0–100 | 35.6 ± 14.5 | 12.5 | 56.2 |

| Sport and recreation, 0–100 | 15.0 ± 12.2 | 0 | 35 |

Mean (±SEM, N = 10) values unless otherwise indicated. Kelgren-Lawrence (KL) grading of radiographic osteoarthritis severity (0–4; 0 defining “no osteoarthritis” and 4 defining “severe osteoarthritis”)

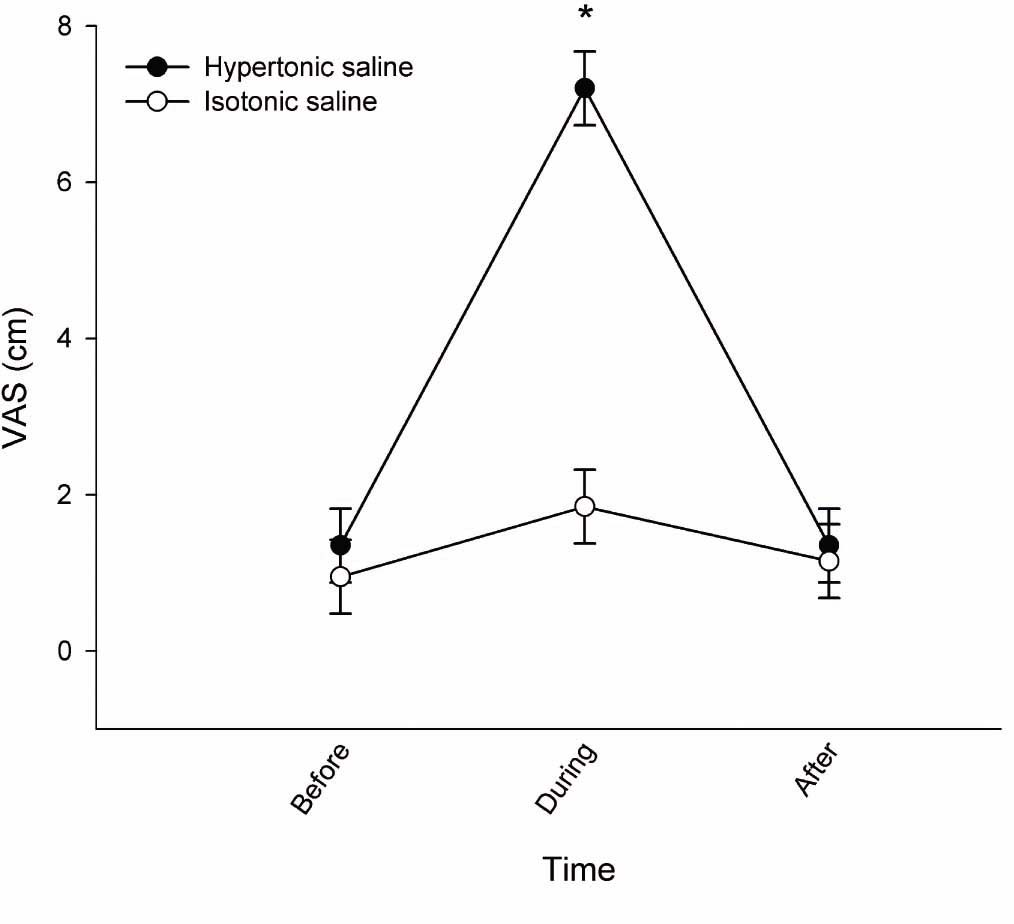

3.1 Saline-induced infrapatellar fat pad pain

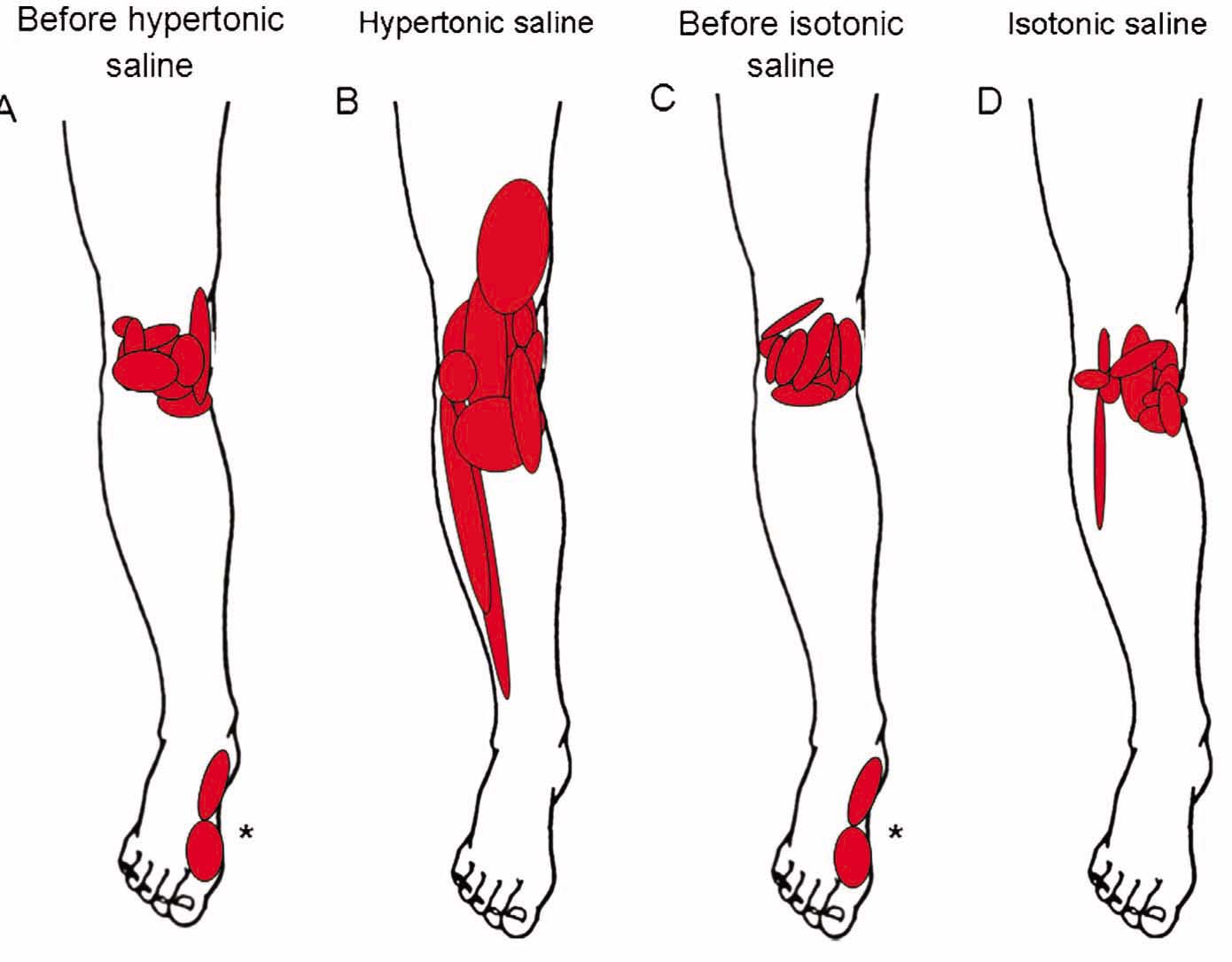

Of the ten participants included, data from trials during experimental pain (hypertonic saline) from one participant was not collected due to a vasovagal reaction to the experimental pain. The mean peak NRS following hypertonic saline was 7.2 ± 0.7 and significantly higher than the 1.9 ±0.7 after isotonic saline (mean difference: 5.4 95% CI 4.3–6.4; P< 0.0001) (Fig. 2). The experimental pain peaked during the initial 1–2 min and then gradually declined. All participants did not recognize the experimental pain after 15–20 min. The saline-induced pain was distributed around the knee with dominance in both the medial and lateral area of the knee (Fig. 3B). In addition, the participants perceived expanded areas of referred pain during the experimental pain (Fig. 3B), as compared to distribution of OA pain before injection (Fig. 3A) and during isotonic saline (Fig. 3C). One participant experienced referred pain to the foot before injection of both hypertonic and isotonic saline (Fig. 3A and C). This referred experience disappeared after both injections (Fig. 3B and D), but the particular participant also experienced expanded referred pain to the calf and thigh areas. When injected with isotonic saline, the pain distribution was similar when comparing before and after the injection (Fig. 3C and D).

Pain intensity of saline-induced pain demonstrated as mean NRS scores (±SEM; N = 10, during pain after hypertonic saline N = 9). VAS scores are presented as baseline (before), during and after injection of hypertonic (filled circles) and isotonic saline (open circles). *NRS was significantly increased after hypertonic saline compared with isotonic saline (P × 0.0001).

The individual pain distribution superimposed on anatomical drawings at baseline (A, N = 10), before hypertonic saline (B, N = 10), after experimental pain induced by hypertonic saline (C, N = 9), before the control condition with injection of isotonic saline (D, N = 10), and after injection of isotonic saline (E, N = 10). *The referred pain areas in the foot are from one individual.

3.2 Pressure pain threshold after experimental pain

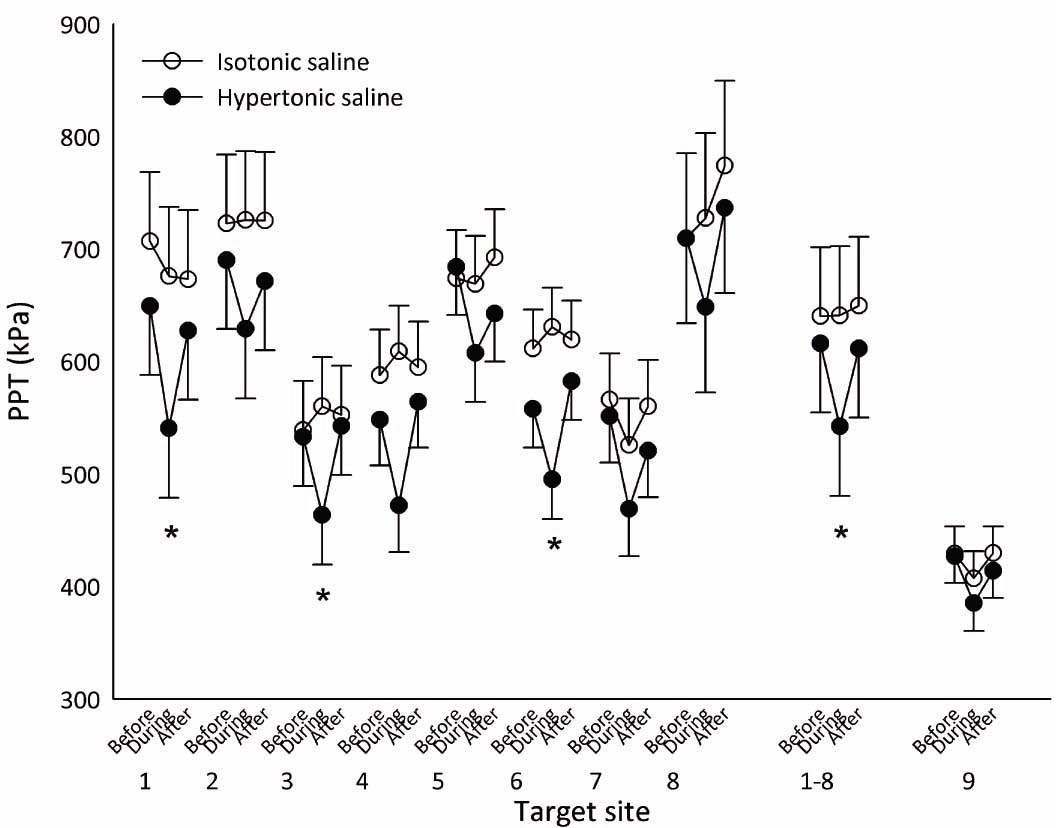

There was a significant interaction between sequence and saline (F2,86 = 3.2; P = 0.047) for the PPT at sites 1, 3, and 6 (Fig. 4). From Fig. 4 a general tendency towards reduced PPT at all sites was observed during the experimental pain (hypertonic saline injection), the post hoc analyses only revealed significantly lower PPT at site 1 (2 cm distal to the inferior medial edge of patella; mean difference: 135.2 kPa [95% CI 80.4–190.1], P×0.0001), site 3 (3 cm lateral to the midpoint on the lateral edge of patella; mean difference: 96.4 kPa [95% CI 52.4–140.2], P×0.0001), and site 6 (2 cm proximal to the superior medial edge of patella; mean difference: 135.5 kPa [95% CI 89.9–181.1], P× 0.0001) during pain after hypertonic saline injections compared with isotonic saline injections. At sites 4, 5, and 8 (Fig. 4) there were statistical tendencies (P×0.10). At sites 2, 7, and 9 (control site) there were no indices of statistical differences (P>0.35). To assess if the overall PPTs were changed by the experimental pain, the analysis were repeated in the pooled PPTs across sites 1–8. The results showed a significant sequence × saline interaction (F2,916 = 6.7; P = 0.0013 with a significantly lower pooled PPT during pain after hypertonic saline injections compared with isotonic saline injections (mean difference: 98.8 kPa [95% CI 68.3–129.3], P×0.0001). The pooled PPTs are shown in Fig. 4.

Mean PPTs (±SEM; N = 10, during pain after hypertonic saline N = 9) from assessment sites 1–8 (see Fig. 1), assessment sites 1–8 pooled, and the contralateral control site 9 before, during and after injection of hypertonic (filled circles) and isotonic saline (open circles). A general tendency towards reduced PPT at all sites was observed during the experimental pain (hypertonic saline injection), which was confirmed in the analysis of the pooled PPTs. *PPT significantly reduced during hypertonic saline compared with isotonic saline (P×0.001).

3.3 Temporal summation of pressure pain

For both hypertonic and isotonic saline injections, VAS scores progressively increased in response to the sequential pressure stimuli for the three assessment sites before, during and after saline injections (stimulation number main effect, F9,1137 = 234.9, P = 0.0001, Fig. 5).

Temporal summation of pain demonstrated as mean VAS scores (±SEM; N = 10, during pain after hypertonic saline N = 9) in response to sequential pressure stimulation on the infrapatellar fat pad (A and B), vastus lateralis muscle (C and D), and tibialis anterior muscle (E and F). VAS scores are presented as baseline (triangles), during (circles), and after injection (squares) of hypertonic (left column, filled symbols) and isotonic saline (right column, open symbols). The VAS scores are normalized by subtraction to the VAS score from the first stimulus (i.e. VAS scores always zero for the first stimulus in all conditions). Significant difference in VAS scores between hypertonic and isotonic saline immediately after (during) the injection (*, P× 0.05).

At none of the three sites were there significant sequence × saline × stimulation number interactions. Thus, the models were reduced focusing on the sequence × saline interactions. At the infrapatellar fat pad, there was a significant sequence × saline interaction (F2,1143 = 8.0; P = 0.0004). Post hoc analyses showed that before and during pain after injection of hypertonic saline in the infrapatellar fat pad pressure stimuli on the infrapatellar fat pad evoked overall higher VAS scores compared with before and immediately after injections of isotonic saline (mean difference before: 0.17 cm [95% CI 0.02–0.33], P< 0.03; mean difference during: 0.25 cm [95% CI 0.09–0.42], P< 0.003) (Fig. 5A and B).

At the vastus lateralis muscle, there was a significant sequence × saline interaction (F2,1135 = 7.6, P = 0.0006). Post hoc analyses showed that before and during pain after injection of hypertonic saline in the infrapatellar fat pad pressure stimuli on the vastus lateralis muscle evoked overall higher VAS scores compared with before and immediately after injections of isotonic saline (mean difference before: 0.34cm [95% CI 0.23–0.45], P< 0.0001; mean difference during: 0.35 cm [95% CI 0.23–0.47], P< 0.0001) (Fig. 5C and D).

At the tibialis anterior muscle sequential pressure stimulation resulted in VAS scores with a significant interaction between sequence and saline in the mixed linear model (F2,1145 = 14.0, P=0.0001). Post hoc analyses showed that during and after pain injection of hypertonic saline in the infrapatellar fat pad, pressure stimuli on the tibialis anterior muscle evoked overall higher VAS scores compared with injections of isotonic saline (mean difference during: 0.29 cm [95% CI 0.16–0.42], P<0.0001; mean difference after: 0.19 cm [95% CI 0.07–0.32], P<0.003) (Fig. 5E and F).

4 Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the effect of experimental knee pain on the dynamics of the pain system in patients with knee OA. The novel contribution of this study is the finding that experimental knee pain in patients with knee OA cause knee hyperalgesia and facilitated temporal summation of pain, illustrating that the pain system in individuals with knee OA can be affected even after many years of nociceptive input.

4.1 Experimental knee pain and hyperalgesia

Hypertonic saline caused a significantly higher pain intensity compared with isotonic saline in individuals with knee OA, which is in line with similar experimental knee pain models in healthy young subjects [12,17,18,26].

For the first time, this study directly compared the pain distribution of OA pain and experimental knee pain in the same subject (Fig. 3A-D). The individuals described the experimental pain areas as being larger compared with their habitual OA knee pain and with the control injection (isotonic saline), as well as having referred pain to the thigh and lower leg (Fig. 3B). This is in contrast to studies using the experimental pain model in healthy young subjects where the experimental pain areas are smaller [4,8,12,26]. The larger areas indicate that the patients with knee OA have facilitated referred pain mechanisms, as suggested previously [3,8,27]. Interestingly, one individual experienced decreased referred pain to the ankle-medial foot after both hypertonic and isotonic saline injections, but experienced referred pain to the thigh and calf region. This reaction in the foot area remains unexplained.

The hyperalgesia to pressure stimulation during experimental knee pain observed in the present study (as compared with the control injection) is in line with those observed in healthy subjects [5,12] and in knee OA patients [3] suggesting facilitated pain mechanisms. Importantly, the mechanically induced changes found in the present study were confined to the knee indicating that the experimental pain only facilitated regional hyperalgesia. This corroborates findings from a study by Rakel et al. [5], where hyperalgesia to pressure stimulation was observed at the affected knee but not at distant sites. These findings is in contrast to studies measuring PPTs in participants with advanced knee OA pain showing significantly lower PPTs at the effected knee and also at distant sites compared to controls [4,28]. The reason for this discrepancy could be related to the severity of the pain which was mild in the present study (Fig. 2).

4.2 Facilitated temporal summation of pressure induced pain

The experimental knee pain facilitated the temporal summation of pressure pain at the knee and adjacent muscles (as compared to the control injection), which was also observed previously in healthy young subjects [12]. This indicates an enhanced sensitivity of the central mechanisms responsible for temporal summation of pain. Plastic changes or central sensitization within the neural organization of the spinal cord occur during development of joint inflammation [7,29], which leads to facilitation of the spinal neu-ronal processing of the afferent inputs from group III and IV afferent fibres. This leads to increased sensitivity or reduced thresholds to non-noxious pressure on the inflamed joint and, with some delay, to the adjacent and non-inflamed tissue, the latter indicating that spinal neurons expand their receptive fields [7,29]. Similar to the changes in hyperalgesia, the experimental pain intensities and distribution, the changes in temporal summation during experimental pain were enhanced when compared to those previously reported in healthy young subjects [12]. The enhanced temporal summation found in the present study is in line with a study by Arendt-Nielsen showing enhanced temporal summation at the affected knee in OA patients [4], but in contrast to a study by Rakel et al. [5] showing lack of significant findings in mechanical induced temporal summation.

4.3 Facilitation of central mechanisms

Overall, the findings in the present study suggest that experimentally induced pain elicit and facilitate central pain mechanisms in similar patterns as those observed in healthy young subjects [12]. There is growing consensus that knee OA involves low-grade inflammation contributing to generation and maintenance of pain [30, 31,32]. It is well known that inflammatory joint disease leads to both peripheral and central sensitization of the nociceptive system [30,32] and this study supports this.

There are limitations to this study that need to be considered when evaluating these results. First, the small sample size may preclude detection of statistically significant associations. However, the general OA population is heterogeneous and primarily affects women. We believe that the heterogeneity is representative, and despite this heterogeneity we were able to detect significant changes. Another limitation is the lack of an age-matched control group, which forces us to compare to other studies that use same methods – which unfortunately only exists on healthy subjects. However, these data are the first of their kind and provide important stepping stones for future investigations.

5 Conclusion

This study showed that acute experimental knee pain induced in patients with knee OA leads to hyperalgesia and facilitated temporal summation in the knee and surrounding muscles thus confirming previous studies on healthy subjects. Furthermore, the present study indicates that the dynamics (i.e., the adaptive responses to pain) of the nociceptive system were intact in individuals with chronic knee OA pain as the responses to experimental pain are similar to those previously observed from healthy subjects, showing that the pain system in individuals with knee OA can be affected even after many years of nociceptive input.

6 Implications

These observations are relevant for a better understanding of pain mechanisms in chronic knee OA pain. Although knee OA is a chronic pain condition associated with increased pain sensitivity, this study indicate that the adaptability in the pain system is intact, which opens for opportunities to prevent development of centralized pain syndromes.

Highlights

Experimental knee pain leads to hyperalgesia in the knee and surrounding muscles.

Facilitated temporal summation was observed in the knee and surrounding muscles.

Experimental pain in OA patients are similar to responses seen in healthy subjects.

The dynamics of the nociceptive system in individuals with knee OA pain is intact.

Findings relevant for understanding pain mechanisms in chronic knee OA pain.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2014.11.001.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. No other staff has been involved in this study.

-

Author contribution: Study conception and design: Jørgensen, Henriksen, Danneskiold-Samsøe, Bliddal, Graven-Nielsen. Acquisition of data: Jørgensen, Rosager, Klokker, Ellegaard, Henriksen. Analysis and interpretation of data: Jørgensen, Henriksen, Bliddal, Graven-Nielsen. Drafting the manuscript: Jørgensen, Henriksen, Graven-Nielsen. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approval for submission: Jørgensen, Henriksen, Rosager, Klokker, Ellegaard, Danneskiold-Samsøe, Bliddal, Graven-Nielsen. Responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to finished article: Graven-Nielsen.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Oak Foundation, Centre for Sensory Motor Interaction (SMI) at Aalborg University, and The Danish Agency for Science Technology and Innovation (FI).

References

[1] Felson DT. The sources of pain in knee osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2005;17:624–8.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Schaible HG. Mechanisms of chronic pain in osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2012;14:549–56.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Lee YC, Lu B, Bathon JM, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT, Page GG, Edwards RR. Pain sensitivity and pain reactivity in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hobo-ken) 2011;63:320–7.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB, Laursen BS, Madeleine P, Simonsen OH, Graven-Nielsen T. Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain 2010;149:573–81.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Rakel B, Vance C, Zimmerman MB, Petsas-Blodgett N, Amendola A, Sluka KA. Mechanical hyperalgesia and reduced quality of life occur in people with mild knee osteoarthritis pain. Clin J Pain 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Suokas AK, Walsh DA, McWilliams DF, Condon L, Moreton B, Wylde V, Rendt-Nielsen L, Zhang W. Quantitative sensory testing in painful osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil 2012;20:1075–85.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Schaible HG, Richter F, Ebersberger A, Boettger MK, Vanegas H, Natura G, Vazquez E, Segond von BG. Joint pain. Exp Brain Res 2009;196:153–62.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L. Assessment of mechanisms in localized and widespread musculoskeletal pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Nie H, Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Neilsen L. Spatial and temporal summation of pain evoked by mechanical pressure stimulation. Eur J Pain 2009;13:592–9.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Neogi T, Frey-Law L, Scholz J, Niu J, Arendt-Nielsen L, Woolf C, Nevitt M, Bradley L, Felson DT. Sensitivity and sensitisation in relation to pain severity in knee osteoarthritis: trait or state? Ann Rheum Dis 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bradley LA, Kersh BC, DeBerry JJ, Deutsch G, Alarcon GA, McLain DA. Lessons from fibromyalgia: abnormal pain sensitivity in knee osteoarthritis. Novartis Found Symp 2004;260:258–70.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Joergensen TS, Henriksen M, Danneskiold-Samsoee B, Bliddal H, Graven-Nielsen T. Experimental knee pain evoke spreading hyperalgesia and facilitated temporal summation of pain. Pain Med 2013;14:874–83.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Graven-Nielsen T, Wodehouse T, Langford RM, Arendt-Nielsen L, Kidd BL. Normalization of widespread hyperesthesia and facilitated spatial summation of deep-tissue pain in knee osteoarthritis patients after knee replacement. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2907–16.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke TD, Greenwald R, Hochberg M. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1039–49.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Roos EM, Lohmander LS. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:64.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Jespersen A, Dreyer L, Kendall S, Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Neilsen L, Bliddal H, Danneskiold-Samsoe B. Computerized cuff pressure algometry: a new method to assess deep-tissue hypersensitivity in fibromyalgia. Pain 2007;131:57–62.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Henriksen M, Graven-Nielsen T, Aaboe J, Andriacchi TP, Bliddal H. Gait changes in patients with knee osteoarthritis are replicated by experimental knee pain. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:501–9.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Henriksen M, Rosager S, Aaboe J, Graven-Nielsen T, Bliddal H. Experimental knee pain reduces muscle strength. J Pain 2011;12:460–7.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Graven-Nielsen T, Mense S, Arendt-Nielsen L. Painful and non-painful pressure sensations from human skeletal muscle. Exp Brain Res 2004;159:273–83.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Wright A, Graven-Nielsen T, Davies II, Arendt-Nielsen L. Temporal summation of pain from skin, muscle and joint following nociceptive ultrasonic stimulation in humans. Exp Brain Res 2002;144:475–82.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Arendt-Nielsen L, Graven-Nielsen T. Translational musculoskeletal pain research. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011;25:209–26.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Nie H, Arendt-Neilsen L, Andersen H, Graven-Nielsen T. Temporal summation of pain evoked by mechanical stimulation in deep and superficial tissue. J Pain 2005;6:348–55.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L, Svensson P, Jensen TS. Quantification of local and referred muscle pain in humans after sequentialim. injections of hypertonic saline. Pain 1997;69:111–7.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Nie H, Arendt-Neilsen L, Madeleine P, Graven-Nielsen T. Enhanced temporal summation of pressure pain in the trapezius muscle after delayed onset muscle soreness. Exp Brain Res 2006;170:182–90.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Nie H, Madeleine P, Arendt-Neilsen L, Graven-Nielsen T. Temporal summation of pressure pain during muscle hyperalgesia evoked by nerve growth factor and eccentric contractions. Eur J Pain 2009;13:704–10.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Bennell K, Hodges P, Mellor R, Bexander C, Souvlis T. The nature of anterior knee pain following injection of hypertonic saline into the infrapatellarfat pad. J Orthop Res 2004;22:116–21.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Bajaj P, Bajaj P, Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Neilsen L. Osteoarthritis and its association with muscle hyperalgesia: an experimental controlled study. Pain 2001;93:107–14.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Imamura M, Imamura ST, Kaziyama HH, Targino RA, Hsing WT, de Souza LP, Cutait MM, Fregni F, Camanho GL. Impact of nervous system hyperalgesia on pain, disability, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a controlled analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1424–31.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Schaible HG, Grubb BD. Afferent and spinal mechanisms of joint pain. Pain 1993;55:5–54.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Schaible HG, Von Banchet GS, Boettger MK, Brauer R, Gajda M, Richter F, Hensellek S, Brenn D, Natura G. The role of proinflammatory cytokines in the generation and maintenance of joint pain. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1193:60–9.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Goldring MB, Otero M. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2011;23:471–8.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Sommer C, Kress M. Recent findings on how proinflammatory cytokines cause pain: peripheral mechanisms in inflammatory and neuropathic hyperalgesia. Neurosci Lett 2004;361:184–7.Search in Google Scholar

© 2014 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Neuroinflammation and glial cell activation in pathogenesis of chronic pain

- Topical review

- Perspectives in Pain Research 2014: Neuroinflammation and glial cell activation: The cause of transition from acute to chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Outcome of spine surgery: In a clinical field with few randomized controlled studies, a national spine surgery register creates evidence for practice guidelines

- Observational study

- Results of lumbar spine surgery: A postal survey

- Editorial comment

- Partner validation in chronic pain couples

- Original experimental

- I see you’re in pain – The effects of partner validation on emotions in people with chronic pain

- Editorial comment

- Pain management with buprenorphine patches in elderly patients: Quality of life—As good as it gets?

- Clinical pain research

- Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of buprenorphine in treatment of chronic pain using competing EQ-5D weights

- Editorial comment

- Invisible pain – Complications from too little or too much empathy among helpers of chronic pain patients

- Observational study

- Although unseen, chronic pain is real–A phenomenological study

- Editorial comment

- Knee osteoarthritis patients with intact pain modulating systems may have low risk of persistent pain after knee joint replacement

- Clinical pain research

- The dynamics of the pain system is intact in patients with knee osteoarthritis: An exploratory experimental study

- Editorial comment

- Ultrasound-guided high concentration tetracaine peripheral nerve block: Effective and safe relief while awaiting more permanent intervention for tic douloureux

- Educational case report

- Real-time ultrasound-guided infraorbital nerve block to treat trigeminal neuralgia using a high concentration of tetracaine dissolved in bupivacaine

- Original experimental

- Modulation of the muscle and nerve compound muscle action potential by evoked pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Neuroinflammation and glial cell activation in pathogenesis of chronic pain

- Topical review

- Perspectives in Pain Research 2014: Neuroinflammation and glial cell activation: The cause of transition from acute to chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Outcome of spine surgery: In a clinical field with few randomized controlled studies, a national spine surgery register creates evidence for practice guidelines

- Observational study

- Results of lumbar spine surgery: A postal survey

- Editorial comment

- Partner validation in chronic pain couples

- Original experimental

- I see you’re in pain – The effects of partner validation on emotions in people with chronic pain

- Editorial comment

- Pain management with buprenorphine patches in elderly patients: Quality of life—As good as it gets?

- Clinical pain research

- Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of buprenorphine in treatment of chronic pain using competing EQ-5D weights

- Editorial comment

- Invisible pain – Complications from too little or too much empathy among helpers of chronic pain patients

- Observational study

- Although unseen, chronic pain is real–A phenomenological study

- Editorial comment

- Knee osteoarthritis patients with intact pain modulating systems may have low risk of persistent pain after knee joint replacement

- Clinical pain research

- The dynamics of the pain system is intact in patients with knee osteoarthritis: An exploratory experimental study

- Editorial comment

- Ultrasound-guided high concentration tetracaine peripheral nerve block: Effective and safe relief while awaiting more permanent intervention for tic douloureux

- Educational case report

- Real-time ultrasound-guided infraorbital nerve block to treat trigeminal neuralgia using a high concentration of tetracaine dissolved in bupivacaine

- Original experimental

- Modulation of the muscle and nerve compound muscle action potential by evoked pain