Abstract

Background

Research has emphasised the essential role of psychosocial risk factors in chronic pain. In practice, pain is usually verified by identifying its physical cause. In patients without any distinct pathology, pain is easily defined as imaginary pain. The aim of this qualitative study was to explore the invisibility of chronic pain, from the patients’ perspective.

Methods

Thirty-four participants with chronic pain were interviewed. The mean age of the participants was 48 years, and 19 of them were women. For 21 of the participants, the duration of pain was more than five years, and most of the participants had degenerative spinal pain. The transcribed interviews were analysed using Giorgi’s four-phase phenomenological method.

Results

The participants’ chronic pain was not necessarily believed by health care providers because of no identified pathology. The usual statements made by health care providers and family members indicated speculation, underrating, and denial of pain. The participants reported experience of feeling that they had been rejected by the health care and social security system, and this feeling had contributed to additional unnecessary mental health problems for the participants.

As a result from the interviews, subthemes such as “Being disbelieved”, “Adolescents’ pain is also disbelieved”, “Denying pain”, “Underrating symptoms”, “The pain is in your head”, “Second-class citizen”, “Lazy pain patient”, and “False beliefs demand passivity” were identified.

Conclusions

In health care, pain without any obvious pathology may be considered to be imaginary pain. Despite the recommendations, to see chronic pain as a biopsychosocial experience, chronic pain is still regarded as a symptom of an underlying disease. Although the holistic approach is well known and recommended, it is applied too sparsely in clinical practice.

Implications

The Cartesian legacy, keeping the mind and body apart, lives strong in treatment of chronic pain despite recommendations. The biopsychosocial approach seems to be rhetoric.

1 Introduction

Pain is defined by the IASP, International Association for the Study of Pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage”. Chronic pain is defined as pain lasting for more than three months, and its cause is rarely identified [1]. One of every five person experiences some type of chronic pain, and chronic pain accounts for more than two-thirds of all visits to physicians [2]. The consequences of pain can be divided to physical implications such as disabilities and restrictions in movements, and psychological implications, such as distress, anxiety, and depression [3]. Persons with chronic pain also suffer from loss of identity [4] and social isolation [5,6]. At present, there is increasing evidence regarding the effects of chronic pain, but the phenomenon of chronic pain is still poorly understood [7], possibly, also reflecting poor management of chronic pain. In a European pain survey, one third of chronic pain patients had received no treatment at all, 40% of them received inadequate treatment that affected their social and working lives, and only 2% of them underwent treatment managed by a pain specialist [8]. In a recent review, Sessle [9] calls for more pain education and management of chronic pain, away from the traditional medicine.

The biopsychosocial paradigm, originated in the study of Engel (1977), has proven to be the most heuristic understanding of chronic pain [2]. However, it does not explain the phenomenon of chronic pain and the individual meanings of it which, from the phenomenological point of view, define individual affects and its management [10]. As the chronic pain patient views the personal life through pain, the experience of pain needs to be understood individually, in order to perform individually tailored managements [5].

Pain does not have any diagnosis of its own. The ICD (International Classification for Diseases) is used to describe identified pathological abnormalities that might implicitly mislead the care providers to treat false-positive physiological findings. If patho-physiology cannot be empirically verified, pain is defined as psychosomatic rather than real [11,12,13]. One of the primary features of chronic pain is its invisibility [6,14], being real to the patient, but due to lack of physical findings it seems unreal to the others [6,13]. The aim of this study was to explore the invisibility of chronic pain, from the patient’s perspective.

2 Phenomenological method

Generally, phenomenological method is a method to study experiences that are difficult to study with any other method. Giorgi’s method is a descriptive method, following Husserl’s tradition to describe the phenomenon as it presents itself to the participants. Giorgi’s method was initially developed and used in psychology, but as he has stated, it is applicable to any social science that works with human beings, e.g., in qualitative health research. Despite the flexibility of the method to be modified and used in a range of fields, the researcher has to assume the attitude of the specific discipline and show sensitivity to detect the phenomena of interest [15].

Giorgi’s four-phase method was chosen and applied to determine the essential meanings of chronic pain for the following reasons: (a) Giorgi’s method has a descriptive tradition, (b) phenomenology is a science of experiences, (c) experience consists of meanings, and (d) the aim in phenomenology is to analyse the meanings of the experience and describe the structure of the experience and in analysis using an epoche’, bracketing previous knowledge of pain aside [15].

2.1 Study methods

2.1.1 Participants

Eligible patients were informed about the study and asked if they would be willing to participate. Fifteen outpatients were recruited from the Department of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, and six outpatients from the Pain Clinic at the same University Hospital. Four participants were obtained from the local back peer-support group and nine from the local pain peer-support group by the first author.

The inclusion criterion were: (a) chronic pain of at least 3 months as defined by the patient’s own physician, (b) willingness to talk about the individual experience of chronic pain, (c) ability to read and write in Finnish, and (d) a minimum age of 18 years. All enrolled 34 volunteers met the inclusion criteria representing a heterogeneous sample of chronic pain patients.

The ages of the participants ranged from 26 to 73 years. Of the participants, 19 were women and 21 were married. Half of the participants were retired, and a fifth worked full-time. Each of the participants could walk without any assistance but many needed help in tasks including household work. Most of the participants used a combination of medications. The individual and pain-related characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

| Participant | Gender f/m | Age | Marital status | Work status | Pain duration | VAS | Medication | Diagnosis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| f/m | yrs | Single | Married | Other | At work | Retired | Unemployed | Other | <1 year | 1-3 yrs | 3-5 yrs | >5 yrs. | mm | Pain killers | Antidepressants | Combination | ||

| 1 | f | 26 | x | x | x | 0 | x | Sciatic syndrome | ||||||||||

| 2 | f | 26 | x | x | x | 18 | x | Causalgia | ||||||||||

| 3 | f | 56 | x | x | x | 48 | x | Cervical spinal stenosis | ||||||||||

| 4 | f | 54 | x | x | x | 86 | x | Fibromyalgia | ||||||||||

| 5 | f | 50 | x | x | x | 71 | x | Spondyarthrosis cervicalis | ||||||||||

| 6 | f | 64 | x | x | x | 47 | x | Sciatic syndrome | ||||||||||

| 7 | f | 31 | x | x | x | 90 | x | Chronic LBP | ||||||||||

| 8 | f | 29 | x | x | x | 62 | x | Chronic LBP | ||||||||||

| 9 | f | 58 | x | x | x | 6 | x | Chronic LBP | ||||||||||

| 10 | f | 53 | x | x | x | 64 | x | Chronic LBP | ||||||||||

| 11 | f | 31 | x | x | x | 18 | x | Thoracic pain | ||||||||||

| 12 | f | 60 | x | x | x | 80 | x | Causalgia | ||||||||||

| 13 | f | 60 | x | x | x | 23 | x | Back pain | ||||||||||

| 14 | f | 53 | x | x | x | 45 | x | Chronic LBP | ||||||||||

| 15 | f | 59 | x | x | x | 76 | x | Sciatic syndrome | ||||||||||

| 16 | f | 60 | x | x | x | 73 | x | Lumbar spondylarthrosis | ||||||||||

| 17 | f | 45 | x | x | x | 56 | x | Pelvic pain | ||||||||||

| 18 | f | 45 | x | x | x | 47 | x | Fibromyalgia | ||||||||||

| 19 | f | 26 | x | x | x | 20 | x | CRPS | ||||||||||

| 20 | m | 55 | x | x | x | 83 | x | Sciatic syndrome | ||||||||||

| 21 | m | 51 | x | x | x | 43 | x | Sciatic syndrome | ||||||||||

| 22 | m | 36 | x | x | x | 55 | x | Cervical disc herniation | ||||||||||

| 23 | m | 30 | x | x | x | 77 | x | Chronic LBP | ||||||||||

| 24 | m | 53 | x | x | x | 66 | x | CRPS | ||||||||||

| 25 | m | 50 | x | x | x | 76 | x | Cervical spondylarthrosis | ||||||||||

| 26 | m | 73 | x | x | x | 83 | x | Polyneuropathy | ||||||||||

| 27 | m | 47 | x | x | x | 64 | x | Chronic neck pain | ||||||||||

| 28 | m | 58 | x | x | x | 68 | x | Sciatic syndrome | ||||||||||

| 29 | m | 37 | x | x | x | 89 | x | Spondylarthritis | ||||||||||

| 30 | m | 33 | x | x | x | 1 | x | Sciatic syndrome | ||||||||||

| 31 | m | 60 | x | x | x | 77 | x | Sciatic syndrome | ||||||||||

| 32 | m | 58 | x | x | x | 40 | x | Sciatic syndrome | ||||||||||

| 33 | m | 56 | x | x | x | 23 | x | Spondylarthritis | ||||||||||

| 34 | m | 45 | x | x | x | 55 | x | Sciatic syndrome | ||||||||||

2.1.2 Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District Ethics Committee. During the recruitment session the nature of the study and an informed consent was obtained from each participant.

2.1.3 Data collection

The first author (TO) collected the data by using open interviews at library café, at coffee shop, at participant’s home, in a treatment room of the hospital, or in a meeting room of a peer-support group from May to November 2011 after contacting each participant by telephone to ensure his/her willingness to participate. A copy of the signed informed consent was also given to the participant. Every interview started with a short conversation before recording the interview. Field notes were not made during the interview.

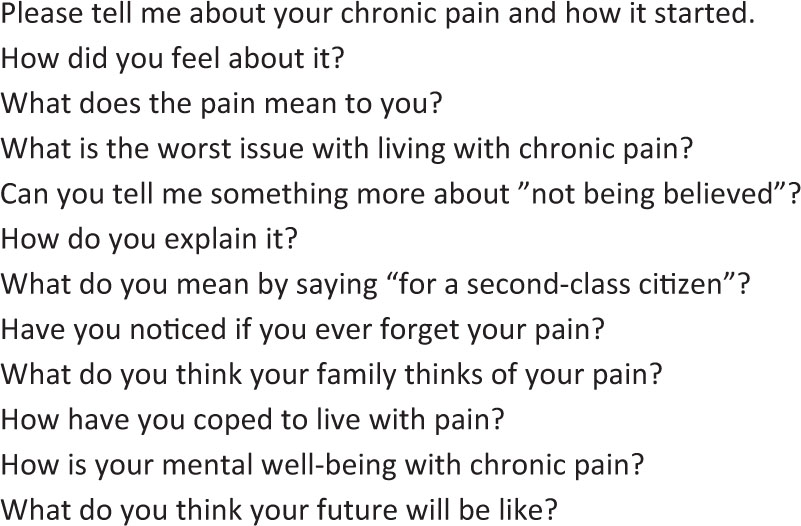

The interviews were as open as possible by using open-ended questions [16] to allow the participant to tell about the experience of chronic pain as much as possible. The key statement was as followed: “Please, tell me about your chronic pain and how it started”. Additional questions were used, depending on how much he/she revealed. Fig. 1 presents questions, which were used in one interview.

An example of questions which were used in one interview.

The individual interviews lasted from 45 to 90 min, and they were transcribed by a professional transcriptionist. The complete collection of the interviews consisted of 631 transcribed pages, ranging from 11 to 31 pages per participant. The transcriptions were not returned to the participants for comments.

2.1.4 Meaning analysis

The data was analysed using a phenomenological method according to Giorgi (Fig. 2).

In the second phase, the first author discriminated the meaning units of chronic pain from each participant’s transcription using his/her own words or expressions in order to find out the individual meaning units for pain [15,17]. Meaning units consisted of a few words up to a whole sentence and were noted every time the participant referred to pain.

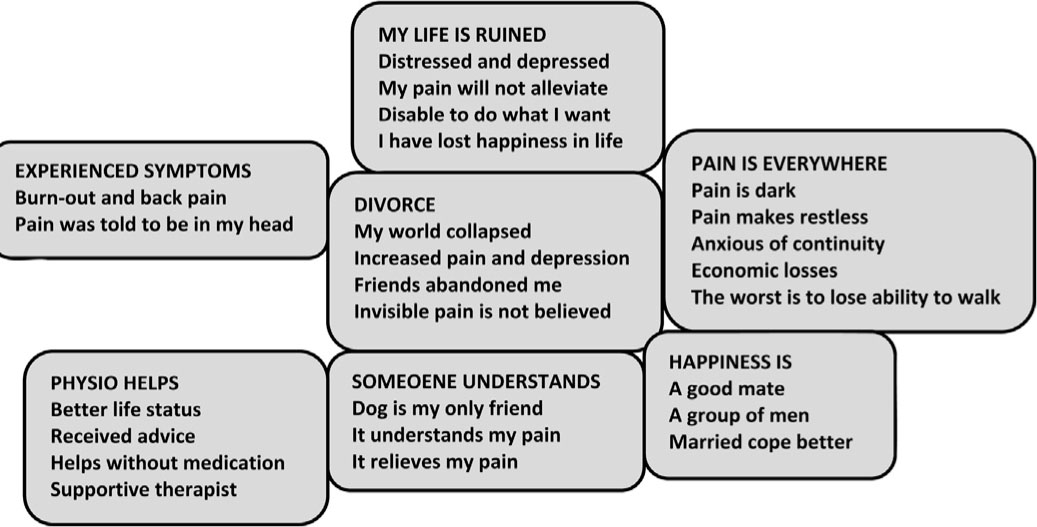

Each participant’s meaning units, based on his/her description (for example, personal mood during pain) were collected, and a meaning structure, as we entitled it, was formed. The meaning structures were arranged so that the most valuable one, from the participant’s perspective was placed on top, and the others were placed below it and/or in parallel in an order that reflected how they were related to each other. The value of each of the meaning structure was defined by how the participant described the experience of it, and how he/she referred it to the other meaning structures. This organised collection of the meaning structures constituted a personal meaning network. In addition, a meaning perspective, which represented the entire experience of chronic pain for the participant, was written. In this phase, the language was changed to reflect a third-person perspective [15,17]. Fig. 3 presents the analysis of chronic pain of one participant (P28).

In the synthesis, definition of the essential theme of chronic pain was extracted from the meaning structures of all the participants [15,17]. Some meaning structures were combined and/or retitled to achieve precision and complexity following the phenomenological tradition. Fig. 4 presents the reduction of the data from the meaning units to the subthemes and to the essential theme.

The meaning analysis using Giorgi’s four-phase phenomenological method.

P28’s meaning network of chronic pain. P28’s meaning perspective “There is no sense in my life” P28 had to retire from his job due to burn out and low back pain. His symptoms were vague and he was never examined well. He thinks that his burn out was associated with his continuing back pain. Ever since his retirement, P28 has experienced depression and distress and he has felt himself to be a disabled man. P28 does not believe that his pain will ever be alleviated permanently and therefore he has lost his exuberance. If he had to choose between living and dying, he would choose the latter. P28 lives in his own house and due to his disability he has also had financial problems. His wife divorced him due to his pain by explaining that he was too ill for her. This point represented the ultimate collapse of his world. His depression, distress, and pain intensified and he felt he was all alone own because his friends had also abandoned him. They did not believe P28’s pain to be real due to the lack of any visible trauma or injury and because P28 was active and maintained a good level of physical fitness, which he still does to the best of his ability. For this reason, a complete loss of ability to move is the worst scenario for him. P28’s pain is dark and agonising presence and he thinks that those who are married cope better with pain. His only friend is his dog, which understands him and helps alleviate his pain. P28 longs for the companionship of other men and a good friend to talk with and to engage in men’s hobbies with. Physiotherapy has improved P28’s quality of life. He prefers physiotherapy because it does not involve medication. For him good physiotherapy requires a supportive therapist.

The reduction of the data. The figure presents how the essential theme and the subthemes were constructed from the meaning units. The size of the font represents the value of the theme; the biggerthe font the more valuable the theme.

Phases one and two of the meaning analysis were performed by the first author. Phases three and four were performed by the entire team under the direction of an experienced author (AP).

3 Results

The analysis was focused on the definition of chronic pain, such as “Unseen chronic pain”, linked with the subthemes “Being disbelieved”, “Adolescents’ pain is also disbelieved”, “Denying pain”, “Underrating symptoms”, “The pain is in your head”, “Second-class citizen”, “Lazy pain patient”, and “False beliefs demand passivity”. Fig. 5 presents “The eidetic structure of the experience of unseen chronic pain” and shows how its subthemes are related to each other. The most valuable subtheme, “Being disbelieved”, as stated on the top, is the perspective from which the figure opens and should be read. The value of the subthemes was determined from the individual network and the synthesis of all the participants’ networks. The results were not checked by the participants.

The eidetic structure of “Unseen chronic pain”. This figure illustrates how the subthemes are related to each other and how they function in a chain. In reality, the related subthemes partly overlap, but they are presented separate for clarity.

3.1 Being disbelieved

The participants claimed that, in order to be believed, their invisible pain had to be somehow visualised for the others. Without any broken leg or distinct physical trauma, pain remains unreal to the others. It also became very clear that there is a great difference between believing and understanding the effects of pain. For the non-experiencer, it is much easier to believe than to understand what pain does to a person.

P15 (in Table 1 ): It’s the invisibility of pain. It would be much easier if you had a cast on your hand. With pain, you just try to hide it, and nobody knows what a hell you have in your body when nothing is seen outside.

Disbelief of the experience of pain was realised in the participants’ disappointments with their Health care provider, (HCP). The participants consistently reported that the invisibility of pain was beyond the doctors’ understanding. Many participants experienced frustration and sadness when the doctors referred them to another doctor. This resulted to delays in treatment, and the participants’ impression was that the doctors did not take responsibility for treatment.

P3: Some believe some don’t. A year ago, I had terrible neck pain and migraine. I went to the health center and couldn’t believe when the doctor told me to go home, take a rest and have a Burana. I drove straight to the psychiatric clinic and said, “I can’t take anymore”. I wonder if the poor doctor will do something fatal from not listening to the patient.

(Burana is the trade name of ibuprofen that can be purchased without a prescription)

According to some the participants, their spouses disbelieved the pain of their partner, stating that the participant was too ill due to the pain, and divorced him/her. The participants argued that, at best, genuine support and the presence of the spouse can save the chronic pain patient’s life, while at worst a lack of support can ruin his/her life permanently. Those who were left alone wished to find a companion in the belief that coping together would be easier. They stated that “shared joy doubles the joy, and shared pain halves the pain”.

P28: Because of the pain, I could n’t sleep for many months. My wife was at work and due to my restless sleep she moved to another address and since that I had nobody to talk to. My depression worsened, and I did n’t find any sense in my life. My world collapsed.

3.2 Adolescents’ pain is also disbelieved

Some of the participants were teenagers when they for the first time contacted a doctor for back pain, headache or due to an accident. Simple medications, usually analgesics, were easy to obtain, and the doctors convinced the participants that the drugs could cure them. The participants’ interpretation was that they were not believed, because the doctor’s opinion was that a teenager cannot have such pain. Hasty and inadequate examinations as well as poor treatment guidance prompted a pain-medication circle that could not be later controlled properly. As adults, these participants emphasised that young persons cannot understand how the pain may affect their future and they may find it difficult to act the best suitable way. All that the participants wanted were to be taken seriously and examined more carefully by the doctor, because it is expected that if a young person complains about pain, there is something wrong.

P1: I am very angry because the doctor did not take me seriously. Afterwards I realised that mental guidance is very important, and without education the patient leaves an open question, “What If I don’t have a pain at all?”

3.3 Underrating symptoms

The participants described how the doctors attempted to find traumas or abnormalities in their bodies that would explain their pain. The participants were dissatisfied with the doctors’ statements, their guidelines for treatment to use medication, which primarily was ibuprofen. One participant (P34) commented that his treatment was something between “carelessness and total vanity”.

P13: The underrating. Ten years ago I went to a doctor for my back pain, and he prescribed me the famous Burana. The pain got worse, and I realised that the treatment was not right at all, and I wasn’t informed of rehabilitation or other strategies.

The participants claimed that the occurrence of a physical trauma or an injury was not always an adequate indication for treatment. Although having bruises and pieces of glass in their bodies as a consequence of an accident some participants experienced that the doctors’ examinations were hasty and they supposed that the reason for this was constant hurry and lack of money and argued that the attitude of HCPs’ is to get rid of him/her as soon as possible. The participants felt that they were left stranded on their own by the public health care system. In the private sector, they said, they could have had adequate treatment, but for many of them the costs of private treatment was out of reach.

P2: Because of the collision, we went to the hospital. After five hours of waiting, a very tired doctor called me in and said “It seems that you have a bruise on your leg and on your head.” I expected some information or something to be done for me. The doctor just said, “You may have a concussion. Go home, you will be all right”.

3.4 Denying pain

Without finding any abnormality or injury, the doctors denied the participants’ experienced pain. For the doctors, invisible pain is non-existent pain.

P14: In the health centres I was n’t believed. I was only told that degenerations can’t be painful with a reply “There’s nothing wrong with you. If you feel bad, you can take those pills”.

Many of the participants reported that they deliberately tried to deny the pain to themselves and tried to function as normally as possible because of responsibilities due to their children, for example. Additionally, they did not want to differentiate themselves from the normal population. The idea of the personal denial was to control the pain, which was an illusion.

P34: I tried to deny and hide the pain, and I was very good at it. I did n’t want my children to see dad’s pain. However, in the end, by denying the truth the whole house of cards fell down.

3.5 Second-class citizen

In searching for help, the chronic pain patient becomes a rambler, a “difficult patient” who - from the HCP’s perspective - wants something that the HCP is not capable to provide. This is why a chronic pain patient may feel like a “second-class citizen”.

P33: No matter if you go to a GP or to a welfare office, you’ll get the same rejection. You’ll see a stiff upper lip and the impression that you came to whine. The service is like for a second-class citizen.

3.6 The pain is in your head

The participants were very sad because they had experienced being disbelieved and regarded as not having any pathology, and also because their pain was addressed as being imaginary in origin by the HCPs. One orthopedist had said to one of the participants, “You can get rid of the pain if you throw it out of your mind”; to another, the choice was to contact a psychiatrist. The participants also experienced that even many of their friends were not convinced of the reality of their pain and suspected that their friends thought they were avoiding their company or making excuses for not seeing them. When the doctors and friends underrated and suspected the reality of their pain and the employers questioned the justification for their sick leaves due to the pain, they felt suspicions and insinuations from others caused them to think about their own mental health.

P16: I was 16 when I had the first pain in my back. Iwas told that I was young so it can’t be so painful, and I was escaping something. I asked myself “How can I cope when I have a life ahead and a family to build? Do I have something wrong in my head when nobody takes me seriously?”

3.7 Lazy pain patient

Other individuals whose underrating was hurtful were the spouses, who were expected to support and understand to the very end. Some of the spouses believed that the pain existed, but they could not understand how it affected on the participants’ lives, thus called them lazy or mischievous. The negative attitude of the spouse lowered the participant’s self-esteem resulting to additional increase in isolation, distress, and despair in marriage, because the spouse did not understand all the effects of chronic pain. The participant with the impairments and disabilities was not the same person as before pain, but he/she was not a worse person which he/she was implied to be by the spouse.

P18: My husband expected that I should always dress the children and take them to the day care. In the end, I was so exhausted that I was lying on the floor, and my husband said, “You lazy woman, just lie on the floor”.

3.8 False beliefs demand passivity

The participants claimed that in order to be believed one should behave and act like a patient in pain is supposed to behave. They reported that the general opinion is that pain, immobility and passivity are connected to each other. Others may not believe you if you are active and still having pain. The false beliefs, misconceptions and false expectations of pain behaviour from the others inflicted additional distress on the participants.

P31:I should be lying in bed and totally knocked out to be believed. I am active, and I like to do everything, even crawling if required. That is why I am not believed by the others.

4 Discussion

The most important finding of the study was that pain without any pathology was disbelieved by the others. This indicates that the Cartesian legacy dominates in the understanding and treatment of chronic pain. Despite the recommendations, the biopsychosocial paradigm seems to be rhetoric in clinical practice and chronic pain patients are not taken seriously with their unseen pain.

The results indicate that discovering the pathology would allow the others to visualise and verify the participants’ pain. The participants’ impressions were that even the HCPs did not understand their pain experiences without any visible evidence. Generally, it was considered that it was the participant’s task to justify the existence of his/her pain. Disbelief was manifested in the underrating of symptoms, in the complete denial of pain, and in arguing that the pain was imaginary.

Maybe the most relevant study to the present one is the study by Clarke and Iphofen [6] where four women and four men with different types of chronic pain were examined by a multi-method approach. The essential theme which was found was “unseen pain” with subthemes, such as “isolation”, “needing to prove the existence of chronic pain”, “in their head”, and “depression”. The essence of both studies was that the unseen nature of chronic pain caused disbelief, distress, and other psychosocial problems to the participants.

Some studies are in agreement with our findings. Pain without any pathology can be regarded as a secret disorder [5], and a person suffering from it may be stigmatised as mentally ill [18] or, as the participants put, it “it is in your head” as has also been found in other studies [14,19]. These reactions increased the pain experience and inflicted mental distress as well as unnecessary human suffering. The participants felt that they were stranded and rejected not only by the health care system, but also by the social security system, their employers, as well as their family members. To feel like a “second-class citizen” indicated a desire to be taken seriously with pain, being believed, treated properly, and to be respected as a person, which are ethically essential issues in health care. The feeling to be a “second-class citizen” referred also to a stigma of being mentally ill or a person who complains pain without any evidence. Studies [6,18] have concluded that first of all, a chronic pain patient needs to be taken seriously being believed, and secondly, properly examined, diagnosed as well as treated, using pain education and guidance for self-management.

Although technology has provided numerous improved methods for the diagnoses of serious pathological conditions, it cannot visualise or explain the experience of pain [20]. Moreover, despite remarkable increase in treatments and examinations in recent years (i.e., 629% increase in epidural injections, 423% increase in opioids use, 307% increase in MRI, magnetic resonance imaging scans, and 220% increase in surgery from 1988 to 2004), the rate of disability due to chronic back pain and other chronic health conditions has still increased [21,22]. Due to the fact that all pain is invisible [6,20,23] and immeasurable [14,23], it is very difficult to understand the disbelief of it. In fact, if someone were able to successfully visualise pain, he/she would make it something that it is not. Most importantly, experienced pain is real, the reality is in the experience itself, whereas an imaginary pain is not a real experience due to its transient duration, insignificance and non-responsiveness to critical appraisal [24,25].

The primary method of treatment in this study was medication, which represents the traditional symptomatic pain treatment, although even the most potent medication produces only a 35% reduction of pain for half of users [26]. The participants were not sure that the drugs they used had the desired positive effect. Instead they were convinced of their adverse effects, including addiction, nausea, dizziness, and memory deficits, as has also been reported in several systematic reviews concerning antidepressants [27], relax-ants [28], NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) [29] and opioids [30]. In general, the results of the present study showed that the management of chronic pain was unsatisfactory by the HCPs and ineffective in supporting the participants. The level of distrust on the treatment of chronic pain by the HCPs was shown by the fact that only two out of five participants indicated that they received enough support from their HCPs. This further increased the importance of family members’ compassion and support.

The results highlight the need for pain education of HCPs. Pain mechanisms are well known but the practical skills, how to educate patients to cope with the psychosocial effects of chronic pain is required. Moreover, according to the results, the comprehension of pain being an experience is still incomplete. This has also been found in other studies [31,32,33], for example considering the underestimation of pain [34] and pain prejudices by the HCPs [35]. Further, biomedically educated HCPs have noted to use their own attitudes as guidelines in pain treatment [36]. Health care is generally assumed to be the setting where the best management and knowledge of pain are obtained; at the moment its ability to meet this goal seems to be poor.

Besides sensory dimension, chronic pain has also affective, cognitive and evaluative dimensions, which should be kept in mind in the assessment and treatment of chronic pain [37]. Several studies have also shown that psychosocial factors are crucial in the chronification process and in the experience of pain [7,30]. The current paradigm is that the experience of chronic pain is a qualitative process [38] with interpretations and opinions [23] as well as a social, moral and cultural experience [14]. Therefore, explaining and treating chronic pain solely from a traditional medical perspective is insufficient. The biopsychosocial paradigm, based on the work by Engel (1977), has proven to be the most widely accepted perspective for understanding and treating chronic pain [1,2,3,8,23,39].

The findings of our study raise a question, what are the reasons for making chronic pain so hard to believe. According to the results, the strongest argument is related to the Cartesian legacy that chronic pain is not understood as an experience, but instead only a symptom of an underlying disease. Further studies are needed about the reluctance of using the official recommendations and guidelines in treating chronic pain patients, in order to change these attitudes and misconceptions. In addition, the reverse perspective needs to be also examined; how the HCPs apply the suggested guidelines and the biopsychosocial paradigm in clinical practice.

5 Strengths and limitations

The present study provides a deeper understanding of chronic pain, which is the strength of the study. Secondly, the study had adequate number of participants as no new meaning units were found in the 34th participant’s interview, which indicates a saturated data. Thirdly, a multidisciplinary team-work formed the meaning structures and performed the final synthesis.

Regarding the limitations, we do not claim that this is the only eidetic structure of “Unseen chronic pain”. However, the systematic analysis by the team provided credibility to the results. Many of the participants were interviewed and listened to for the first time, which might have influenced some meaning units in exaggerating their significance. Although the results agree with other studies, they should not be generalised to cover all chronic pain patients or extrapolated to other cultures.

6 Conclusions

From the patient’s perspective, life with “Unseen chronic pain” is balancing with different realities. The individual reality is that the experienced pain is real. The second reality is that without any demonstration of pathology, the personal reality is speculative. The third reality is the scientific reality, in which all pain is invisible, immeasurable, and individual. The fourth reality is that from the patient’s perspective, the HCPs often forget these realities in practice. The HPCs should be more sensitive to patients’ expectations and needs and treat the whole person - not only fixing an identified “broken” or “dysfunctional” body part. The results also indicate that “Unseen chronic pain” is not only a medical issue. To assist in developing a better multidisciplinary clinical practice and education for chronic pain, additional studies integrating expertise from various fields are required.

7 Implications

There is gap between the recommendations and practice in treatment of chronic pain. In practice, the Cartesian legacy seems to dominate, although the recommendations and guidelines support the holistic approach. The patient in pain is the one who needs treatment, not only the pain itself.

Highlights

The Cartesian legacy lives strong in treatment of chronic pain despite recommendations.

The usual statements by health care providers indicated disbelief and denial of pain.

The biopsychosocial approach is only rhetoric.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2014.09.004.

-

Funding sources Oulu University Hospital Clinic of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine.

-

Conflict of interest

Conflicts of interest statement The authors have no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the participants and the staff of the Rehabilitation and Pain Clinics of Oulu University Hospital.

References

[1] IASP. International Association for the Study of Pain. Classification of chronic pain. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Gatchel R, Peng Y, Fuchs P, Peters M, Turk D. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull 2007;4:581–624.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Linton S. Understanding pain for better clinical practice. A psyhcological perspective. Printed in China: Elsevier Limited; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Bullington J. Embodiment and chronic pain: implications for rehabilitation practice. Health Care Anal 2009;17:100–9.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Thomas S. A phenomenologic study of chronic pain. Western J Nurs Res 2000;22:683–705.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Clarke K, Iphofen R. A phenomenological hermeneutic study into unseen chronic pain. Brit J Nurs 2008;17:658–63.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Apkarian A, Baliki M, Geha P. Review-towards a theory of chronic pain. Prog Neurobiol 2009;87:81–7.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Breivik H, Collet B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287–333.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Sessle B. The pain crisis: what it is and what can be done. Review article. Pain Res Treat 2012;2012:1–6. Article ID 703947.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Gallagher S, Zahavi D. The phenomenological mind. An introduction to philosophy of mind and cognitive science. London: Routledge Publications; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Scarry E. The body in pain. The making and unmaking of the world. New York: Oxford University Press; 1985.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Osborn M, Smith J. Living with a body separated from the self. The experience of the body in chronic benign low back pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Scand J Caring Sci 2006;20:216–22.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Pesut B, McDonald H. Connecting philosophy and practice: implications of two philosophical approaches to pain for nurses’ expert clinical decision making. Nurs Philos 2007;8:256–63.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Honkasalo ML. Chronic pain as a posture towards the world. Scand J Psychol 2000;41:197–208.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Giorgi A. The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology. A modified Husserian approach. 3rd printing Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Smith J, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. Theory, method and research. Chippenham: Sage publication; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Giorgi A. Phenomenology and psychological research. 15th printing Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Lillrank A. Back pain and the resolution of diagnostic uncertainty in illness narratives. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1045–54.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Kenny D. Constructions of chronic pain in doctor-patient relationships: bridging the communication chasm. Patient Educ Couns 2004;52:297–305.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Derbyshire S. Can neural imaging explain pain? Psychiatr Clin N Am 2011;34:595–604.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Deyo R, Mirza S, Turner J, Martin B. Over treating chronic back pain: time to back off? J Am Board Fam Med 2009;22:62–8.Search in Google Scholar

[22] http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs352/en/index.html; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Melzack R. Evolution of the Neuromatrix Theory of Pain. The Prithvi Raj Lecture: Presented at the Third World Congress of World Institute of Pain. Pain Pract 2004;2:85–94.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Merleau-Ponty M. Phenomenology of perception. Padstow: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Steinhaug S. Women’s strategies for handling chronic muscle pain. A qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health 2007;25:44–8.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Turk D, Winter F. The pain survival guide. How to reclaim your life. Fourth printing Baltimore: Port City Press; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Urquhart D, Hoving J, Assendelft W, Roland M, van Tulder M. Antidepressants for non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;23:1.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Richards B, Whittle S, Buchbinder R. Muscle relaxants for pain management in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;18:1.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Roelofs P, Deyo R, Koes B, Scholten R, van Tulder M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 23:1.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Noble M, Treadwell J, Tregear S, Coates V, Wiffen P, Akafomo C, Schoelles K. Long-term opiomanagement for chronic non-cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;20:1.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Sloman R, Ahern M, Wrigh A. Nurses’ knowledge of pain in the elderly. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;21:317–22.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Visentin M, Trentin L, de la Marco R, Zanolin E. Knowledge and attitudes of Italian medical staff towards the approach and treatment of patients in pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;22:925–30.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Simmonds M, Derghazarian T, Vlaeyen J. Physiotherapists’ knowledge, attitudes, and intolerance of uncertainty influence decision making in low back pain. Clin J Pain 2012;6:467–74.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Solomon P. Congruence between health professionals’ and patients’ pain ratings: a review of the literature. Scand J Caring Sci 2001;15: 174–80.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Messeri A, Scollo A, Guidi G, Simonetti M. Pain knowledge among doctors and nurses: asurvey of 4912 healthcare providers in Tuscany. Minerva Anesthesiol 2008;74:113–8.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Darlow B, Fullen B, Dean S, Hurley D, Baxter G, Dowell A. The association between health care professional attitudes and beliefs and the attitudes and beliefs, clinical management, and outcomes of patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Eur J Pain 2012;16:3–17.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Sim J, Smith M. The sociology of pain. In: French S, Sim J, editors. Physiotherapy a psychosocial approach. 3rd edition Printed in China: Butter worth Heineman; 2004. p. 117–39.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Lame I, Peters M, Vlaeyen J, Kleef M, Patijn J. Quality of life in chronic pain is more associated with beliefs about pain, than with pain intensity. Eur J Pain 2005;9:15–24.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Breen A, Austin H, Campion-Smith C, Carr E, Mann E. You feel so hopeless: a qualitative study of GP management of acute low back pain. Eur J Pain 2007;11:21–9.Search in Google Scholar

© 2014 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Neuroinflammation and glial cell activation in pathogenesis of chronic pain

- Topical review

- Perspectives in Pain Research 2014: Neuroinflammation and glial cell activation: The cause of transition from acute to chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Outcome of spine surgery: In a clinical field with few randomized controlled studies, a national spine surgery register creates evidence for practice guidelines

- Observational study

- Results of lumbar spine surgery: A postal survey

- Editorial comment

- Partner validation in chronic pain couples

- Original experimental

- I see you’re in pain – The effects of partner validation on emotions in people with chronic pain

- Editorial comment

- Pain management with buprenorphine patches in elderly patients: Quality of life—As good as it gets?

- Clinical pain research

- Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of buprenorphine in treatment of chronic pain using competing EQ-5D weights

- Editorial comment

- Invisible pain – Complications from too little or too much empathy among helpers of chronic pain patients

- Observational study

- Although unseen, chronic pain is real–A phenomenological study

- Editorial comment

- Knee osteoarthritis patients with intact pain modulating systems may have low risk of persistent pain after knee joint replacement

- Clinical pain research

- The dynamics of the pain system is intact in patients with knee osteoarthritis: An exploratory experimental study

- Editorial comment

- Ultrasound-guided high concentration tetracaine peripheral nerve block: Effective and safe relief while awaiting more permanent intervention for tic douloureux

- Educational case report

- Real-time ultrasound-guided infraorbital nerve block to treat trigeminal neuralgia using a high concentration of tetracaine dissolved in bupivacaine

- Original experimental

- Modulation of the muscle and nerve compound muscle action potential by evoked pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Neuroinflammation and glial cell activation in pathogenesis of chronic pain

- Topical review

- Perspectives in Pain Research 2014: Neuroinflammation and glial cell activation: The cause of transition from acute to chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Outcome of spine surgery: In a clinical field with few randomized controlled studies, a national spine surgery register creates evidence for practice guidelines

- Observational study

- Results of lumbar spine surgery: A postal survey

- Editorial comment

- Partner validation in chronic pain couples

- Original experimental

- I see you’re in pain – The effects of partner validation on emotions in people with chronic pain

- Editorial comment

- Pain management with buprenorphine patches in elderly patients: Quality of life—As good as it gets?

- Clinical pain research

- Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of buprenorphine in treatment of chronic pain using competing EQ-5D weights

- Editorial comment

- Invisible pain – Complications from too little or too much empathy among helpers of chronic pain patients

- Observational study

- Although unseen, chronic pain is real–A phenomenological study

- Editorial comment

- Knee osteoarthritis patients with intact pain modulating systems may have low risk of persistent pain after knee joint replacement

- Clinical pain research

- The dynamics of the pain system is intact in patients with knee osteoarthritis: An exploratory experimental study

- Editorial comment

- Ultrasound-guided high concentration tetracaine peripheral nerve block: Effective and safe relief while awaiting more permanent intervention for tic douloureux

- Educational case report

- Real-time ultrasound-guided infraorbital nerve block to treat trigeminal neuralgia using a high concentration of tetracaine dissolved in bupivacaine

- Original experimental

- Modulation of the muscle and nerve compound muscle action potential by evoked pain