Association of Modic changes with health-related quality of life among patients referred to spine surgery

-

Juhani Määttä

, Hannu Kautiainen

Abstract

Background and purpose

Modic changes (MC) are bone marrow and vertebral endplate lesions seen in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which have been found to be associated with low back pain (LBP), but the association between MC and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is poorly understood. The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between MC and HRQoL among patients referred to spine surgery.

Methods

The study population consisted of 181 patients referred to lumbar spine surgery in Northern and Eastern Finland between June 2007 and January 2011. HRQoL was assessed using RAND-36 health survey. Lumbar MC were evaluated and classified into ‘No MC’, ‘Type I’ (Type I or I/II), and ‘Type II’ (Type II, II/III or III).

Results

In total, 84 patients (46%) had MC. Of these, 37% had ‘Type I’ and 63% ‘Type II’. Patients with MC were older, more likely females, had longer duration of LBP and a higher degree of disc degeneration than patients without MC. The total physical component or physical dimensions did not differ significantly between the groups. The total mental component of RAND-36 (P = 0.010), and dimensions of energy (P = 0.023), emotional well-being (P = 0.012) and emotional role functioning (P = 0.016) differed significantly between the groups after adjustments for age and gender. In the mental dimension scores, a statistically significant difference was found between ‘No MC’ and ‘Type II’.

Conclusions

Among patients referred to spine surgery, MC were not associated with physical dimensions of HRQoL including dimension of pain. However, ‘Type II’ MC were associated with lower mental status of HRQoL.

Implications

Our study would suggest that Type II MC were associated with a worse mental status. This may affect the outcome of surgery as it is well recognized that patients with depression, for instance, have smaller improvements in HRQoL and disability. Thus the value of operative treatment for these patients should be recognized and taken into consideration in treatment. Our study shows that MC may affect outcome and thus clinicians and researchers should be cognizant of this and take this into account when comparing outcomes of surgical treatment in the future. A longitudinal study would be needed to properly address the relationship of MC with surgical outcome.

1 Introduction

In Health 2000 Survey, a Finnish national survey, every tenth Finn aged 30 or over had a chronic physician-diagnosed low back syndrome [1]. In a population-based European study, 19% of subjects had chronic pain and the low back was the source of pain among nearly half of these patients [2]. Chronic low back pain (LBP) causes enormous costs to society [3,45], both indirect and direct, and chronic pain increases mortality as well [6].

Quality of life (QoL) is defined by the World Health Organization as “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” [7]. Health- related quality of life (HRQoL) takes into account an individual’s physical health, and mental and social domains of life [7,8]. Several questionnaires can be used to measure HRQoL, of which the SF-36 is used worldwide today because it produces scores on multiple aspects of HRQoL [8].

Modic changes (MC) are bone marrow and vertebral endplate lesions which are seen in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [9]. They can be divided into three different types: Type I represents an active ongoing inflammatory process; Type II is thought to reflect fatty degeneration of the bone marrow; while Type III is a late osteosclerotic regenerative process [10,11]. Several studies have shown that MC, especially type I, are associated with LBP [12,13,14,15].

The assessment of HRQoL among patients with LBP has been widely recommended [16]. The aim of this study was to examine the association of LBP related to MC with HRQoL among patients referred to lumbar spine surgery.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study population

Subjects consisted of consecutive patients referred to spine surgery at the Departments of Orthopedic Surgery and Neurosurgery at the Oulu and Kuopio University Hospitals between June 2007 and January 2011. The patients’ place of residence was mainly either the city of Oulu (population c. 140 000), the city of Kuopio (population c. 95 000) or the neighbouring municipalities of these cities, but the enrolment area comprised the three northernmost provinces of Finland: Oulu, Lapland, and Northern Savo. All participants took part voluntarily in the study and signed an informed consent form. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District and is in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Assessment of pain, disability and health-related quality of life

Patients reported duration of LBP and leg pain. Back-related disability was assessed using the Finnish version of Oswestry Disability Questionnaire [17,18]. The diagnoses for surgical referral were obtained from hospital records. We measured HRQoL using the Finnish version of RAND-36 health survey, which is also known as the SF-36 health survey [8,19,20]. RAND-36 and SF-36 health surveys are almost identical; they only differ in the wording of two health concepts, and the correlation of the two health concepts between the health surveys is 0.99 [19,21]. RAND-36 consists of eight health concepts: physical functioning, role limitations caused by physical health problems, pain, general health perceptions, role limitations caused by emotional problems, social functioning, emotional wellbeing and energy/fatigue. Each concept is rated on a 0-100 range. The higher the score, the better the HRQoL. The eight scales of RAND-36 were aggregated into two summary measures: the physical and the mental health components. The physical com-ponent consists of physical functioning, role limitations caused by physical health problems, pain and general health perceptions, while the mental component consists of role limitations caused by emotional problems, social functioning, emotional well-being and energy/fatigue [8]. The summary scores were calculated by multiplying standardized scores by 10 and adding 50 to the product. This yields a distribution of scores with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 [21].

2.3 Magnetic resonance imaging and evaluation of imaging findings

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine was performed with 1.5-T equipment (Signa, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI and Magnetom Avanto, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) on the patients referred to lumbar spine surgery. Routine spine MRI protocol was used, including sagittal T1- and T2-weighted images of the entire lumbar spine. The image matrix for T1-weighted images was 256 × 224 and 448 × 336 and for T2-weighted Images 448 × 224 and 448 × 377 depending on the scanner used (in respective order). The field of view for the images was 28 cm × 28 cm and 30 cm × 30 cm. Slice thickness was 4 mm and 3 mm, and the interslice gap was 1 mm and 0.3 mm.

The scans were analysed in random order by three observers (J.K., J.N., J.M.) with no knowledge of the clinical status. The MC of both upper and lower endplates were classified on a workstation based on the five midsagittal planes, at each lumbar level, into Type

I, Type II or Type III as earlier defined, and mixed Types I/II or II/III [10,11,13,22]. Types I and I/II were grouped together in the analyses (‘Type I’), as all lesions containing Type I change are thought to indicate a more active inflammatory process [15]. Similarly, Types II, II/III and III changes were grouped together (‘Type II’), as they were assumed to manifest a more chronic and stable degenerative process [9]. The height and width of each MC was evaluated and an index for the size of MC was calculated by multiplying the height and width of each MC. In case of MC at multiple levels, the size index of the largest lesion only was included. Signal intensity changes associated with Schmorl’s nodes or tiny spots of signal intensity change in the bone marrow adjacent to the vertebral corners were not recorded.

The degree of intervertebral disc degeneration (DD) was graded using the modified Pfirrmann classification [23]: normal height and clear distinction of the nucleus and annulus (grade 1 or grade 2), normal to slightly decreased height of the intervertebral disc and unclear distinction of the nucleus and annulus (grade 3), normal to moderately decreased height of the intervertebral disc and lost distinction of nucleus and annulus (grade 4) or collapsed disc space and lost distinction of nucleus and annulus (grade 5). The degree of disc herniation (HNP) was defined as a disc displacement less than 50% of the disc circumference, and categorized as either protrusion or extrusion. The disc was defined as protrusion if the greatest distance between the edges of the disc material beyond the disc place was less than the distance between the edges of the base in any of the same planes [24].

2.4 Statistical analysis

The results are given as mean with standard deviation (SD), median with interquartile range (IQR) or calculated as percentage. The most important outcomes are expressed as 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). We compared differences between groups using the chi-square test, Kruskal-Wallis test, analysis of variance (ANOVA) or analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with appropriate contrasts. The ‘No MC’ group was used as the reference group. The localization of statistical significant differences between groups (pairwise comparisons) was made by an appropriate contrast without any adjustment for multiple comparisons.

3 Results

3.1 Study population characteristics

A total of 232 patients were referred to spine surgery but RAND- 36 data and MRI was available for only 181 patients (78%). Of these, 84 (46%) had MC’s: 31 (37%) had ‘Type I’ (17 Type I and 14 Type I/II) and 53 (63%) had ‘Type II’ (48 Type II, 4 Type II/III and 1 Type III). Thirteen patients (7%) had MC at two levels, and five patients (3%) at three levels. Sciatica (ICD-10: M51.1, G55.1*) was the main diagnosis for 130 (72%) patients. In all, 130 (72%) patients were operated and discectomy was performed on 97 (60%) patients (Table 1). Patients with MC were older, more likely females, had longer duration of LBP and had a higher degree of DD than those without MC (Table 1). The groups did not differ with respect to BMI, leisure time physical activity (LTPA), smoking, duration of leg pain or back-related disability (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study population in relation to the type of Modic changes on magnetic resonance imaging.

| Variable | Type of Modic changes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None N = 97 | I or l/II N=31 | II or II/III or III N = 53 | P-value | |

| Number of females (%) | 38 (39) | 21 (68) | 25 (47) | 0.021 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 39 (12) | 46 (9) | 48 (11) | <0.001 |

| BMI[a], mean (SD) | 27 (4) | 26 (5) | 28 (5) | 0.11 |

| Smoking (%) | 37 (39) | 13 (42) | 18 (34) | 0.74 |

| LTPA[b] (%) | 0.90 | |||

| Low | 16 (17) | 4 (13) | 10 (19) | |

| Moderate | 52 (57) | 18 (58) | 26 (50) | |

| High | 24 (26) | 9 (29) | 16 (31) | |

| Oswestry, mean (SD) | 36 (15) | 37 (16) | 40 (16) | 0.24 |

| Pain duration, weeks, median (IQR[c]) | ||||

| Back pain | 52 (21,152) | 104 (32,520) | 208 (36,520) | <0.001 |

| Leg pain | 28 (16,78) | 64 (16,156) | 44 (20,104) | 0.30 |

| Degeneration sum score, median (IQR) | 13 (12,14) | 14 (13,16) | 15 (14,17) | <0.001 |

| Operation (%) | 72 (74) | 19 (63) | 39 (74) | 0.49 |

| Discectomy (%) | 56 (64) | 12 (48) | 29 (60) | 0.37 |

| Herniated nucleus pulposus (%) | 54 (56) | 17 (55) | 34 (64) | 0.56 |

| Sciatica (%) | 77 (82) | 19 (68) | 34 (65) | 0.059 |

3.2 Association of Modic changes with HRQoL

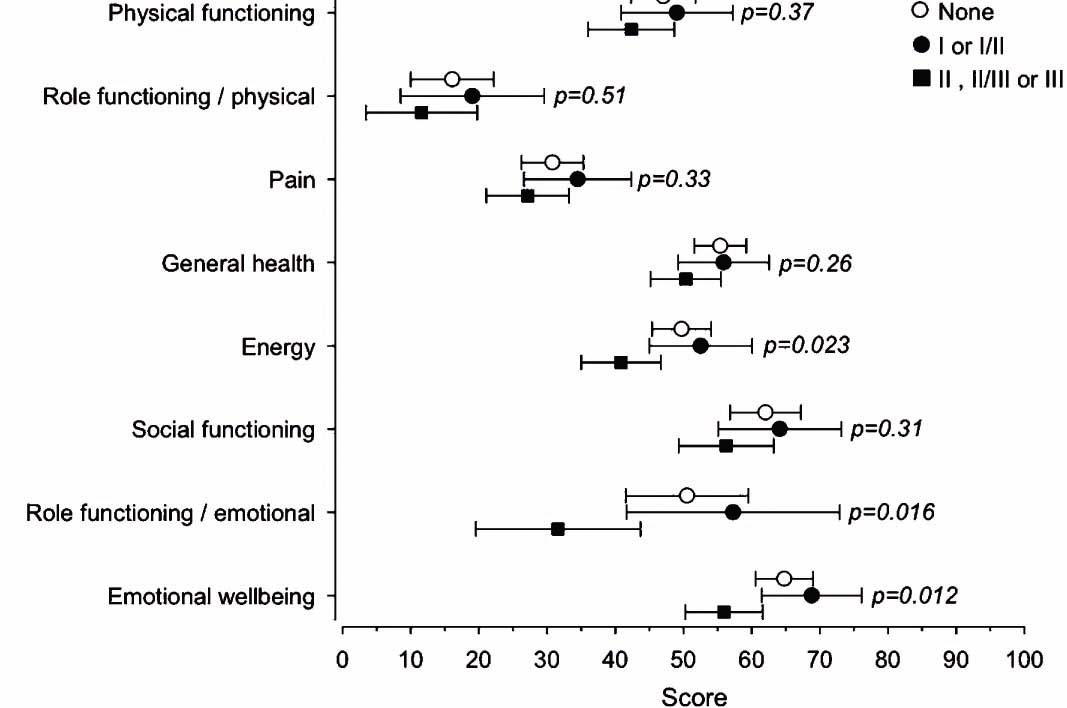

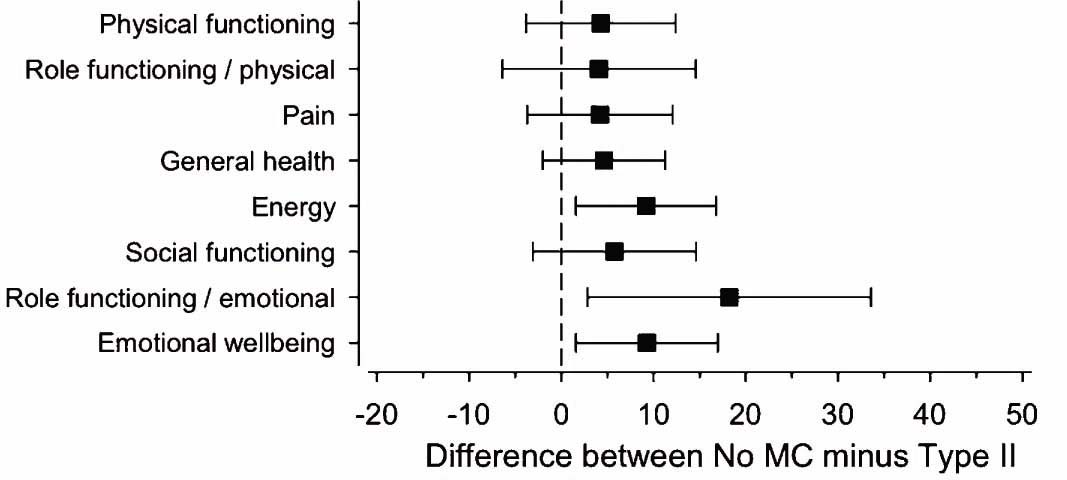

The scores of the total physical component or physical dimensions did not differ statistically significantly between the MC groups, whereas significant differences were observed in the total mental component and mental dimensions. The mean score (SD) of the total physical component was 51 (7) in the ‘No MC’ group, 51 (7) in the ‘Type I’ group and 48 (7) in ‘Type II’ (age and sex adjusted p-value = 0.15). The corresponding figures for the mental component were 51 (8), 52 (8) and 47 (8) (p = 0.010). Fig. 1 shows the age- and sex-adjusted RAND-36 dimension scales by MC groups. After adjustments for age and sex statistically significant differences were found between the groups in the dimensions of energy, emotional well-being and emotional role functioning (p- values 0.023, 0012 and 0.016, respectively; Fig. 1). When using the ‘No MC’ group as reference the statistically significant differences in all of these three mental dimensions were found between the ‘No MC’ and ‘Type II’ groups (Fig. 2). After further adjustments for the degeneration sum score and the duration of low back pain, the difference remained significant in emotional role functioning. There was no difference between the groups in the tertiles of MC size index (total physical component p = 0.33, total mental component p = 0.86).

Age- and sex-adjusted mean scores of RAND-36 dimensions with 95% confidence intervals.

The mean difference with 95% confidence intervals between ‘No MC’ and ‘Type II’ (includes Types II, II/III or III) groups in each dimension of RAND-36 HRQoL.

4 Discussion

4.1 Main findings

Our results indicate that among patients referred to spine surgery, MC were not associated with physical dimensions of HRQoL including dimension of pain. However, ‘Type II’ (including Type II, II/III and III MC) were associated with a worse mental status of HRQoL. This may be because patients with MC had a significantly higher degree of disc degeneration and longer duration of LBP than patients without MC. Thus, it is possible that the association of MC and poor mental health status is mediated through these factors. We may presume that Type II changes present a more persistent subtype than Type I MC.

4.2 Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Generic health status measures, such as RAND-36, are good for comparing the relative impact of different conditions or treatments, and are widely used in the evaluation of LBP [25]. The SF-36 has been found to give the best results of selected general health indicators because of its ability to measure health (i.e. validity) and changes in health (responsiveness) [25]. Aalto et al. [19] have validated the RAND-36 in the Finnish population. They found that it has good reliability, validity and applicability to evaluate HRQoL among Finns.

A major limitation is the cross-sectional design of our study; because of this we cannot draw causal longitudinal inferences. In theory, MC may have existed for longer periods, as they often tend to be quite stable [26]. Over half of the patients were referred to spine surgery because of herniated nucleus pulposus in the lumbar spine, and it has been previously observed that MC develop after disc herniation [26,27,28].

Because quality of life is a subjective definition, and as its aspects have different meanings and values among individuals, the assessment of HRQoL has inherited weaknesses. We did not estimate psychosocial factors in this study, although pain experience and pain catastrophizing also affect strongly HRQoL [29], as we have no reason to believe that patients with MC would have a different psychosocial profile to those without MC.

4.3 Some differences compared to previous studies

The association of MC with quality of life is poorly understood. The relationship between MC and HRQoL has only been evaluated in one previous study with 22 patients with MC and 55 without MC at L5-S1 [30], in which the researchers found no relationship between MC and SF-36 mental or physical component scores. Our study has a larger sample size and we evaluated MC in the whole lumbar spine. We found a relationship between MC and the mental component score. However, earlier findings suggest that MC at L5-S1 are especially associated with low back symptoms [13]. Unfortunately, the sample size of our study did not allow us to analyse the association of MC at L5-S1 with HRQoL.

The relationship between radiographic degeneration in the lumbar spine and HRQoL has recently been evaluated [31]. The researchers found no significant difference in the SF-36 mental or physical component among unexposed subjects and patients with discectomy for lumbar disc herniation. In our study, the degree of DD differed significantly among the groups, being highest in the ‘Type II’ group. When we adjusted for the degree of DD, only the association between MC and emotional role functioning remained significant. This infers that we cannot exclude the possibility that poorer mental health status in the ‘Type II’ group is related merely to a higher degree of DD and not MC per se. Nevertheless, the presence of ‘Type II’ MC is a useful radiological marker for the phenomenon.

Previously, it has been reported that the duration of sciatica symptoms is not related to HRQoL [32] whereas one study [33] observed a significant difference in the physical component of the SF-36 between severe and non-severe disc disease among sciatica patients. In our study, over half of the patients had sciatica due to HNP but the prevalence of HNP or duration of sciatica did not differ significantly between the groups. Moreover, severity of symptoms (pain intensity or disability) or the interaction of severity and duration did not explain the difference in mental scores (data not shown). However, it may well be that patients with degenerative disc disease have a worse HRQoL because they are told that no immediate relief of LBP can be expected. Unfortunately, our sample is too small to evaluate the mechanisms of worse mental status in ‘Type II’ MC.

HRQoL has been associated with age, pain, back-related disability, and depression [34]. Keeley et al. [35] also found a relationship between anxiety, depression or back-related stress, and poorer physical component of HRQoL in their study. We found an association between the presence of MC and mental HRQoL even after adjustments for age and gender. Unfortunately, the presence of MC has not been evaluated in previous studies.

Chronic pain can lead to central sensitization by altering pain sensibility. This occurs peripherally in the somatosensory nervous system by enhancing the nociceptive pathways, and centrally in the central nervous system by lowering the sensory response threshold, thus leading to pain hypersensitivity [36]. Chronic pain has been found to cause symptoms of anxiety or depression even if the patient has no history of mental health problems [37]. Our patients had a long history of LBP, which can provoke mental symptoms and thus diminish mental HRQoL, especially if central sensitization has occurred among these patients.

4.4 Clinical significance

The proportion of MC was high (46%) among patients referred to spine surgery. Our study would suggest that Type II MC were associated with a worse mental status. This may affect the outcome of surgery as it is well recognized that patients with depression, for instance, have smaller improvements in HRQoL and disability [38], and thus the value of operative treatment for these patients should be recognized and taken into consideration in treatment.

To properly address its relationship to surgical outcome a longitudinal study will be needed. Our study serves as a reminder that MC may affect outcome, thus clinicians and researchers should be cognizant of this and take this into account when comparing outcomes of surgical treatment in the future.

5 Conclusions

Among patients referred to spine surgery, MC were not associated with physical dimensions of HRQoL including dimension of pain, while Type II changes tended to be associated with lower mental scores of HRQoL even after adjustments for confounders. In the future studies, the predictive value of MC on back surgery results should be evaluated.

Highlights

Modic changes (MC) are vertebral endplate lesions in magnetic resonance imaging.

46% of 181 patients referred to spine surgery had MC (37% Type I and 63% Type II).

MC were associated with duration of low back pain and degree of disc degeneration.

Type II MC were associated with worse mental status of quality of life.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2013.11.003.

-

Conflicts of interest None.

References

[1] Heistaro S, Arokoski J, Kröger H, Leino-Arjas P, Riihimäki H, Nykyri E, Heliövaara M. Back pain and chronic low-back syndrome. In: Kaila-Kangas L, editor. Musculoskeletal disorders and diseases in Finland. Results of the Health 2000 Survey, B25/2007. Publications of the National Public Health Institute; 2007. p. 14–8 http://www.terveys2000.fi/julkaisut/2007b25.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

[2] Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287–333.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP, Jackman AM, Darter JD, Wallace AS, Castel LD, Kalsbeek WD, Carey TS. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:251–8.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint SurgAm 2006;88(Suppl. 2):21–4.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Costa Lda C, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Hancock MJ, Herbert RD, Refshauge KM, Henschke N. Prognosis for patients with chronic low back pain: inception cohort study. BMJ 2009;339:b3829.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Torrance N, Elliott AM, Lee AJ, Smith BH. Severe chronic pain is associated with increased 10 year mortality. A cohort record linkage study. Eur J Pain 2010;14:380–6.Search in Google Scholar

[7] The World Health Organization Quality ofLife Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 1998;46:1569–85.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Hays RD, Morales LS. The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann Med 2001;33:350–7.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Kuisma M, Karppinen J, Haapea M, Niinimaki J, Ojala R, Heliovaara M, Korpelainen R, Kaikkonen K, Taimela S, Natri A, Tervonen O. Are the determinants ofvertebral endplate changes and severe disc degeneration in the lumbar spine the same? A magnetic resonance imaging study in middle-aged male workers. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008;9:51.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Modic MT, Steinberg PM, Ross JS, Masaryk TJ, Carter JR. Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology 1988;166:193–9.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, Ross JS, Carter JR. Imaging of degenerative disk disease. Radiology 1988;168:177–86.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Albert HB, Kjaer P, Jensen TS, Sorensen JS, Bendix T, Manniche C. Modicchanges, possible causesand relation to low back pain. Med Hypotheses 2008;70:361–8.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Kuisma M, Karppinen J, Niinimaki J, Ojala R, Haapea M, Heliovaara M, Korpelainen R, Taimela S, Natri A, Tervonen O. Modic changes in end- plates of lumbar vertebral bodies: prevalence and association with low back and sciatic pain among middle-aged male workers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1116–22.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Kjaer P, Leboeuf-Yde C, Korsholm L, Sorensen JS, Bendix T. Magnetic resonance imaging and low back pain in adults: a diagnostic imaging study of 40-year-old men and women. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1173–80.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Jensen TS, Karppinen J, Sorensen JS, Niinimaki J, Leboeuf-Yde C. Vertebral endplate signal changes (Modic change): a systematic literature review of prevalence and association with non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J 2008;17:1407–22Search in Google Scholar

[16] Mason VL, Mathias B, Skevington SM. Accepting low back pain: is it related to a good quality of life? Clin J Pain 2008;24:22–9.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Pekkanen L, Kautiainen H, Ylinen J, Salo P, Hakkinen A. Reliability and validity study of the Finnish version 2. 0 of the oswestry disability index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:332–8.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:294052.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Aalto A-M, Aro AR, Teperi J. RAND-36 terveyteen liittyvan elamanlaadun mittarina - Mittarin luotettavuus ja suomalaiset vaestoarvot, vol. 101. Helsinki: Stakes, Tutkimuksia; 1999.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Ware Jr JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36-item health survey 1. 0. Health Econ 1993;2:217–27.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Braithwaite I, White J, Saifuddin A, Renton P, Taylor BA. Vertebral end-plate (Modic) changes on lumbar spine MRI: correlation with pain reproduction at lumbar discography. Eur Spine J 1998;7:363–8.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1873–8.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Fardon DF, Milette PC. Combined Task Forces of the North American Spine Society, American Society of Spine Radiology, and American Society of Neuroradiology. Nomenclature and classification of lumbar disc pathology, Recommendations of the Combined task Forces of the North American Spine Society, American Society of Spine Radiology, and American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:E93–113.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Lurie J. A review of generic health status measures in patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3125–9.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Jensen TS, Kjaer P, Korsholm L, Bendix T, Sorensen JS, Manniche C, Leboeuf-Yde C. Predictors of new vertebral endplate signal (Modic) changes in the general population. Eur Spine J 2010;19:129–35.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Kuisma M, Karppinen J, Niinimaki J, Kurunlahti M, Haapea M, Vanharanta H, Tervonen O. A three-year follow-up of lumbar spine endplate (Modic) changes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:1714–8.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Albert HB, Manniche C. Modic changes following lumbar disc herniation. Eur Spine J 2007;16:977–82.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Lame IE, Peters ML, Vlaeyen JW, Kleef M, Patijn J. Quality of life in chronic pain is more associated with beliefs about pain, than with pain intensity. Eur J Pain 2005;9:15–24.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Shen M, Razi A, Lurie JD, Hanscom B, Weinstein J. Retrolisthesis and lumbar disc herniation: a preoperative assessment of patient function. Spine J 2007;7:406–13.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Mariconda M, Galasso O, Attingenti P, Federico G, Milano C. Frequency and clinical meaning of long-term degenerative changes after lumbar discectomy visualized on imaging tests. Eur Spine J 2010;19:136–43.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Atlas SJ, Deyo RA, Patrick DL, Convery K, Keller RB, Singer DE. The Quebec Task Force classification for Spinal Disorders and the severity, treatment, and outcomes of sciatica and lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:2885–92.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Porchet F, Wietlisbach V, Burnand B, Daeppen K, Villemure JG, Vader JP. Relationship between severity of lumbar disc disease and disability scores in sciatica patients. Neurosurgery 2002;50:12539.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Hakkinen A, Kautiainen H, Sintonen H, Ylinen J. Health related quality of life after lumbar disc surgery: a prospective study of 145 patients. Disabil Rehabil 2005;27:94–100.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Keeley P, Creed F, Tomenson B, Todd C, Borglin G, Dickens C. Psychosocial predictors ofhealth-related quality of life and health service utilisation in people with chronic low back pain. Pain 2008;135:142–50.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain 2009;10:895–926.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Tuzun EH. Quality of life in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007;21:567–79.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Slover J, Abdu WA, Hanscom B, Weinstein JN. The impact of comorbidities on the change in short-form 36 and oswestry scores following lumbar spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:1974–80.Search in Google Scholar

© 2013 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- High risk of depression and suicide attempt among chronic pain patients: Always explore catastrophizing and suicide thoughts when evaluating chronic pain patients

- Clinical pain research

- Suicide attempts in chronic pain patients. A register-based study

- Editorial comment

- Polymorphism in the μ-opioid receptor gene OPRM1 A118G —An example of the enigma of genetic variability behind chronic pain syndromes

- Original experimental

- A118G polymorphism in the μ-opioid receptor gene and levels of β-endorphin are associated with provoked vestibulodynia and pressure pain sensitivity

- Editorial comment

- Genital pain related to sexual activity in young women: A large group who suffer in silence

- Original experimental

- Living with genital pain: Sexual function, satisfaction, and help-seeking among women living in Sweden

- Editorial comment

- The Norwegian version of the Neck Disability Index (NDI) is reliable and sensitive to changes in pain-intensity and consequences of pain-in-the-neck

- Clinical pain research

- Reliability and responsiveness of the Norwegian version of the Neck Disability Index

- Editorial comment

- Quality of life in low back pain patients with MRI-lesions in spinal bone marrow and vertebral endplates (Modic-changes): Clinical significance for outcome of spinal surgery?

- Clinical pain research

- Association of Modic changes with health-related quality of life among patients referred to spine surgery

- Editorial comment

- Warming and alkalinisation of lidocaine with epinephrine mixture: Some useful aspects at first glance, but not so simple?

- Clinical pain research

- Warmed and buffered lidocaine for pain relief during bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. A randomized and controlled trial

- Acknowledgement of Reviewers

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- High risk of depression and suicide attempt among chronic pain patients: Always explore catastrophizing and suicide thoughts when evaluating chronic pain patients

- Clinical pain research

- Suicide attempts in chronic pain patients. A register-based study

- Editorial comment

- Polymorphism in the μ-opioid receptor gene OPRM1 A118G —An example of the enigma of genetic variability behind chronic pain syndromes

- Original experimental

- A118G polymorphism in the μ-opioid receptor gene and levels of β-endorphin are associated with provoked vestibulodynia and pressure pain sensitivity

- Editorial comment

- Genital pain related to sexual activity in young women: A large group who suffer in silence

- Original experimental

- Living with genital pain: Sexual function, satisfaction, and help-seeking among women living in Sweden

- Editorial comment

- The Norwegian version of the Neck Disability Index (NDI) is reliable and sensitive to changes in pain-intensity and consequences of pain-in-the-neck

- Clinical pain research

- Reliability and responsiveness of the Norwegian version of the Neck Disability Index

- Editorial comment

- Quality of life in low back pain patients with MRI-lesions in spinal bone marrow and vertebral endplates (Modic-changes): Clinical significance for outcome of spinal surgery?

- Clinical pain research

- Association of Modic changes with health-related quality of life among patients referred to spine surgery

- Editorial comment

- Warming and alkalinisation of lidocaine with epinephrine mixture: Some useful aspects at first glance, but not so simple?

- Clinical pain research

- Warmed and buffered lidocaine for pain relief during bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. A randomized and controlled trial

- Acknowledgement of Reviewers