Abstract

Having long been largely ignored in political science, emotions have become increasingly acknowledged as integral to human life, making them the subject of academic interest for political and social psychologists, political scientists and policy scholars alike. Challenging an understanding of reason and affect as one of opposition, empirical as well as theoretical work analysing the effects of emotions in political communication, voting behaviour, populism and public policymaking is continuously growing. There is therefore an increased need to take stock of these recent scientific advances on the role of emotions in the political sphere, and more importantly, with regards to public policymaking. This two-fold literature review provides such a state-of-the-art in a systematic and critical manner, showing that whereas knowledge on emotions in the broader realm of politics is already extensive, there is far less on public policies. In fact, from a policy studies perspective, it is policy preferences and policy-related communication which have enjoyed most of scholarly attention, thereby neglecting the concrete role of emotion in the process of public policymaking. Future studies should focus more on the effects of emotions on the actual making of policies.

1 Introduction

In Ancient Greek philosophy, human behaviour was understood to flow from three main sources: desire, emotion, and knowledge. Today, emotions[1] continue to be viewed as providers of crucial information about changes in an individual’s environment, hence assigning them an essential function of how humans understand the world (Pierce 2021, 599). Despite this long-lasting tradition of acknowledging the central role that emotions play, they have traditionally been neglected in political science research, which focussed instead on human reasoning and rationality as driving the phenomena of study. Especially during the last 50 years and more recently, the study of emotions has however increased and diversified, going beyond the field of psychology and neuroscience.[2] This ‘affective turn’ addresses the previous disregard of emotion in a cross-disciplinary endeavour. In political science research, emotions have indeed been shown to influence politically relevant behaviour, e.g. political decision-making including citizens’ voting tendencies (Dinas et al. 2014; Ward 2019) as well as policy and candidate preferences (Gadarian 2010; Albertson and Gadarian 2015, 101; Kupatadze and Zeitzoff 2019; Merrolla et al. 2023). A bulk of research focuses on how emotions are strategically appealed to in communication of policymakers, electoral candidates or members of parliament (Crabtree et al. 2022; Fink et al. 2023; Valentim and Widmann 2023; Verhoeven and Duyvendak 2016; Vogeler et al., 2021) as well as of interest groups in policy debates (Fullerton and Weible 2024; Gabehart et al. 2023; Pierce et al. 2024). Stressing the dual role of emotions in discourse, of being constructed though language as well as constructing language, interpretivist approaches have brought attention to how emotions shape our values, how criticism of being emotional can delegitimise policy endeavours (Durnová 2022; Durnová and Hejzlarová 2023) and how emotional appeals can fuel protest and mobilisation (Verhoeven and Duyvendak 2016). A further topic where emotions have extensively been studied is populism (Hopkins in Huddy et al., 2023; Marx 2020; Wirz 2018), which may serve as an explanation for the overrepresentation of studies on negative emotions, especially fear and anger (cf. Wagner and Morisi 2019, 1).

Given that the first prominent and still influential studies in political psychology date back to the late 1980s (cf., e.g. Frijda 1988; George E. Marcus 1988), it comes as no surprise that scholars can already hark back on some literature reviews about the significance of emotion in the political sphere. Older reviews focus more broadly on the role of affect in explaining events, phenomena or behavioural patterns at the level of the individual (Marcus 2000; Winkielman and Berridge 2003), often relying first and foremost on the work of psychology and neuroscience scholars. Some more recent reviews follow a similar inquiry geared towards the political realm more generally (Maor and Capelos 2023;[3] Webster and Albertson 2022), while others explore the linkages between affect and democratic citizenship, polarisation and populism (Verbalyte et al. 2022;[4] Webster and Albertson 2022). Some of these reviews tend to single out specific discrete emotions (Webster and Albertson 2022), namely anger, fear and enthusiasm, which are considered more straightforward emotional experiences than others and are hence often subject to analysis. Reviewing these emotions is an obvious choice given the extensive knowledge about them and, relatedly, the predominance of Affective Intelligence Theory which centres these three.[5] Literature reviews specifically on the role of emotions in the process of public policymaking are however rare (a notable exception is Pierce 2021).

Considering this shortage and the overall expanding body of research that points to the crucial significance of emotion for public policy studies (Maor 2024; Maor and Capelos 2023), a stocktaking of the current state-of-the-art on the role of emotions in public policymaking becomes more and more expedient to advance an in-depth theoretical foundation for future research. What exactly do we know about the various ways in which emotions impact politics in general and public policymaking in particular? By answering this guiding question, the present review critically assesses central insights from studies in the field of political science and policy studies. It thereby addresses the aforementioned need for a comprehensive review with an explicit focus on policymaking.

As this review shows, policy scholars have indeed started to analyse emotions in recent years, and increasingly so, but the accumulated knowledge has added up in an unsystematic way shedding light on various aspects that indirectly affect public policymaking. Empirical studies with explicit links to policymaking for the most part analyse the effect of emotions on individual policy preferences and, to a significantly lesser extent, investigate emotive rhetoric during policy debates. Research into broader political attitudes, emotional appeals in media and political communication in general as well as populism and affective polarisation is considerably more extensive, yet bears only limited relevance for policy analysis. Recent literature on the COVID-19 pandemic indeed mirrors these patterns. With regards to conceptual work, many policy scholars remark that, albeit often implicitly, affect is considered at the very foundational level of extant policy frameworks (Knaggård et al. 2019, 30; Pierce 2021, 60). Consequently, emotions have to some extent been incorporated into these frameworks (especially into the Multiple Streams Framework; cf. Maor 2024; Zahariadis 2015).

In order to systematise and analyse the reviewed studies, the structure of this article is as follows: first, I will briefly summarise the most prominent approaches and theories for the study of emotion as put forth by political psychologists regarding their applicability in political science research. Section 2 presents the two-fold methodology with which I selected, categorised and examined the studies included in my analysis, namely a systematic review complemented by a narrative review. The main part of this literature review first introduces the findings from the systematic review. Based on major research topics outlined in this overview, I then present and critically assess findings from the narrative review beginning with the current state-of-the-art on emotions in the broader political science literature that only has indirect links to policy research. In a second step, I analyse existing knowledge specifically on emotions in policy studies. Before concluding, I use the COVID-19 pandemic as an illustration to show how the patterns (and imbalances) that characterise the general literature also become apparent when analysing studies on a recent empirical case. Finally, this literature review concludes with a summary of key arguments and an outlook on potential future avenues for policy research.

2 Theoretical Background: Studying Affect and Emotions in Politics

Human experience comprises multiple affective states of which emotion is but one (Gadarian & Brader in Huddy et al., 2023; Ortony 2022; Renström and Bäck 2021; Scherer 2005). It is however the one that has recently gained most of the scholarly attention in the discipline of psychology and beyond. Three emotion theories are most prominent and insightful in their facilitation of analysing emotions from a political science perspective: (Cognitive) Appraisal Theory, a Constructivist Approach to the study of emotion and Affective Intelligence Theory (AIT).

As suggested by its very name, Cognitive Appraisal Theory, or simply Appraisal Theory, understands emotions as “multi-componential” experiences (Sacharin et al. 2012) whose distinctive feature is the element of the individual’s cognitive appraisal of their environment. Cognitive appraisal essentially describes one’s detection and evaluation of external stimuli in regard to whether and how these are significant for personal well-being (Moors et al. 2013, 120; Scherer 2005, 700f.; Smith et al. 1993, 237). Cognition is therefore not seen as opposed to but rather as an integral part of emotion. Emotions are conscious processes (Ortony 2022) that entail specific action tendencies (Frijda 1988, 351; Scherer 2005, 698) or behavioural responses of the individual to the perceived changes in the individual’s environment (Lerner and Keltner 2000, 476; Schmidt-Atzert et al. 2014, 210). This quintessential assumption is highly conducive for empirical research in the field of political science (and related disciplines) that study patterns of acting in a specific manner in politically relevant contexts, such as voting, party or policy support. In her analysis of insecurity narratives in populist rhetoric, Bonansinga (2022) has very faithfully approached emotions based on Appraisal Theory. Her methodological usage of the concept of core relational themes by Richard Lazarus demonstrates how this emotion theory can help identifying emotional appeals in political communication data (p. 91).

In contrast and deducible from its name, the Constructivist Approach emphasises how the experience of an emotion is heavily influenced by the memories, cultural and social roles and values of an individual (Frijda & Mesquita in Kitayama & Markus, 1995; Pierce 2021, 597f.). Concentrating on the way in which we understand others’ (expressions of) emotions, constructivists contend that emotional states “are constructed via the process of categorization” (Barrett 2006, 27), which explains how such heterogenous and subjective experiences like emotions can be rendered comprehensible for certain others with similar cultural backgrounds while they may be misconceived by others (ibid., 26f.). Jasper (1998) provides a very well-developed theoretical integration of a constructivist approach of emotions to the study of social movements and protest. The boundaries of Appraisal Theory and the Constructivist Approach are not clear-cut, in the sense that a constructivist paradigm can work well with an appraisal account of emotion so that scientific research is sometimes informed by more than one approach.[6] Most political science scholars however rely on Appraisal Theory as a conceptual basis for their research, while simultaneously acknowledging the impact of cultural factors on the expression of emotionality.[7]

The “dominant affective theoretical model in political science” (Ridou and Searls 2011, 441) is however Affective Intelligence Theory developed by George E. Marcus, Michael MacKuen and W. Russell Neuman. Enjoying particular popularity in US political psychology, it maintains that emotions help individuals “manage their attention to the political world” (Marcus et al. 2011, 324) given that such attention is limited. Depending on whether an external stimulus is familiar or unfamiliar, one of the two systems in the human brain, the disposition system (familiar stimuli) or the surveillance system (unfamiliar stimuli), gives rise to specific emotions entailing certain behavioural responses (Marcus 2003, 202f.). The scholars thus view affect and cognition as intertwined in the experience and effect of emotion. Whilst they focussed on distributing three emotions on to the two systems, those of anger, fear and enthusiasm, Pierce (2021, 602) has added further emotions according to shared cognitive appraisal and responsive action. However, such grouping remains theory-driven and based on assumptions which points to a more general criticism of AIT’s lack of empirical evidence (cf. Funck and Lau 2023; Ladd and Lenz 2008; 2011). It needs to be stressed though that, while AIT is the most mentioned emotion theory, political science scholars mainly use it in an eclectic manner whereby specific aspects selectively inform the respective studies’ theoretical framework and at times also their research expectations (Banks 2014; Tolbert et al. 2018; Valentino et al. 2011; Vasilopoulos et al. 2023; Wamsler et al. 2021; Widmann 2021).[8] An exception to this is a study by Erhardt et al. (2023), who faithfully and consistently rely on AIT. The authors follow the theory’s main premises well and formulate their hypotheses accordingly.

The predominance of AIT might also correlate with the fact that anger and fear are the most studied emotions in political research (cf. Wagner and Morisi 2019, 1). Anxiety is found to be causally linked to increased policy-learning, even for those with strong, prior opinions (Lablih et al. 2024). In a similar manner, anger is connected to specific voting preferences, namely to the increased support for radical parties even though a causal relationship between emotion and radical vote cannot clearly and consistently be established (Jacobs et al. 2024, 23). In a study on racial attitudes on health care in the US, Banks (2014) finds that strong prior beliefs related to the subject are uniquely bolstered and, as he argues, further polarized by anger, while opinions on other “race-neutral” topics are unaffected by a heightened experience of anger. These exemplary studies demonstrate that emotion is only one of multiple factors that influence politically relevant behaviour, which also makes it more complicated to identify the specific type of relationship, i.e. bidirectional, causal, etc., between an emotion and a certain type of behaviour.

Rooted in emotion theories from psychology, behavioural and neuroscience, political scientists have furthermore developed a variety of concepts which allow for conclusions and expectations to be made in regard to how individuals act as well as think when they experience certain emotions in politically relevant contexts. The affect heuristic (Maor and Capelos 2023, 440; cf. also Fink et al. 2023, 472; Kahan 2013), for example, describes affectively charged shortcuts with the help of which individuals judge objects, people or events, especially when knowledge is little and/or complexity is high. The affective priming hypothesis works in a comparable way as an individual’s accessibility of political arguments is increased by similarly valenced emotions (Kühne et al. 2011). More concretely, feeling positive emotions makes arguments in favour of a policy proposal more readily accessible for the individual and vice versa. How one feels about something may thus be just as or even more important in forming an opinion than more traditional rational-choice-models. A further example is the Hot Cognition Hypothesis according to which every socio-political phenomenon itself has an affective dimension that influences an individual’s evaluation of it (Bakker et al. 2021, 151).

In summary, it is safe to say that the affective turn in political science has given rise to a variety of theoretical concepts and approaches. The intertwinement of cognition and emotion in Appraisal Theory and Affective Intelligence Theory make them particularly popular in this discipline, while most political science scholars appear to shift away from the constructivist critique of an existence of distinct emotions. This is apparent in the fact that studies by and large investigate the role of different discrete emotions, such as anger, fear or hope. This section also indicates that, apart from advances in political science in general, there is less conceptual development in policy studies, which again stresses the need to pay closer attention to this field.

3 Methodology

After having set the theoretical background, the following literature review aims at providing a critical overview of relevant conceptual contributions and empirical studies which investigate the impact of emotions and concern the field of political science and public policy studies. The categorisation of the reviewed literature is based on the content; its contribution to the study of emotions in policy-related research. It is neither based on the journal, in which the articles appeared, nor the disciplinary background of the respective researcher. I followed a two-fold strategy of conducting a systematic review complemented with a more in-depth narrative literature review (Baumeister and Levy 1997). This procedure was chosen given the diverse nature of research topics within the field of political science and policy studies. There is a huge body of literature on emotions in the field of political science and a considerable amount regarding policy analysis, which required the selection to provide an understanding of the manifold concepts and subtopics of interest while simultaneously keeping the review feasible. Conducting a systematic review seems conducive of this purpose. It also laid the foundation for the narrative review as a more detailed deep-dive into specific research areas which crystallised during the systematic review. The narrative approach furthermore allowed for being attentive to other potentially important concepts and terms which might have been missed before.

3.1 The Systematic Review

For the systematic review, a keyword search was conducted using a search string on the Web-of-Science database. To keep it as wide-ranging as possible, the tested string comprises only two key elements: (i) emotion, affect and (ii) policy. The string is as follows: (“emot*” OR “affective”) AND “policy*”. Both, the bracketed and the policy element, constitute crucial components of the string to narrow down the results to the area of policymaking. In order to keep it manageable and applicable, results were limited to the Web of Science Category of ‘political science’. Given these parameters, checking for duplicates (0) and deleting book reviews (9) and corrections (1), a total of 753 results were extracted. In order to be able to perform a hand-coded qualitative analysis of the literature, this sample was again reduced to the most relevant studies by selecting those articles that appeared in policy journals as well as political science journals with an impact factor of at least 2.0[9] (cf. Appendix A). This reduced results to a total of 198 articles. For hand-coding, additional sources from the narrative review were also included to provide a full picture which resulted in a total of 264 pieces of academic literature (cf. Appendix B). Based on the title and abstract, all articles[10] were qualitatively coded[11] for content and method using the following categories:

Content:[12]

Affective Polarisation

Attitude: attitudinal change or systematic linkages triggered or mediated by emotion

Behaviour: behavioural changes or patterns triggered or mediated by emotion

N/A (superficial treatment of emotion(s) and/or affect: only a few mentions; not integrated in the research design; not a substantial part of the theoretical background)

Other (as a residual category)

Policy Preference: certain emotions impacting support of and opposition to a specific policy

Political Communication: emotional appeals and emotive rhetoric in communication by pollical actors as well as politically relevant, often media actors

Theoretical: conceptual contributions; building or refining of theories and concepts

Voting: specific type of behavioural change or pattern triggered or mediated by emotion

Method:[13]

Conceptual Paper

Discourse Analysis

Experiment

Interview

Meta-Analysis (e.g. literature review)

Other (as a residual category and for unspecified methods)

Qualitative Content Analysis (including dictionary-based text analysis)

Quantitative Text Analysis

Survey

3.2 Narrative Literature Review

While emotions have been part of political science research for some time now, policy studies slightly lag behind. Although the systematic coding process has generated literature on both areas, a second step – a narrative review – is necessary to shift the emphasis more clearly on public policymaking as central to this state-of-the-art. For the narrative review, I conducted a qualitative literature search with the help of a library catalogue and well-known search tools, e.g. Google Scholar or Web of Science, using keywords and related expressions that included “emotion”, “affect” and discrete emotions. Considering only peer-reviewed journal articles, chapters in edited volumes and monographies, the corpus comprised conceptual and empirical literature, at times overlapping with the discipline of political psychology. Through the process of snowballing, both backwards and forwards, I identified further relevant studies and incorporated these into the review by paying attention to literature on emotions in politics overall and public policymaking in particular. The selected approach of a narrative literature review allowed for an open-ended and wide search strategy which is well-suited for the purpose of collecting and critically comparing a diverse set of studies in order to show interconnections, overrepresented themes and blind-spots (Baumeister and Levy 1997, 312).

4 Literature Review

4.1 Insights from the Systematic Review

The systematic review gives a quantifying overview presenting notable trends and patterns in the relevant literature. Following the two categories of content and method according to which the literature was coded, this section first introduces complementary insights regarding the content of relevant literature in political science and policy studies. Then, key observations concerning the choice of method are presented.[14]

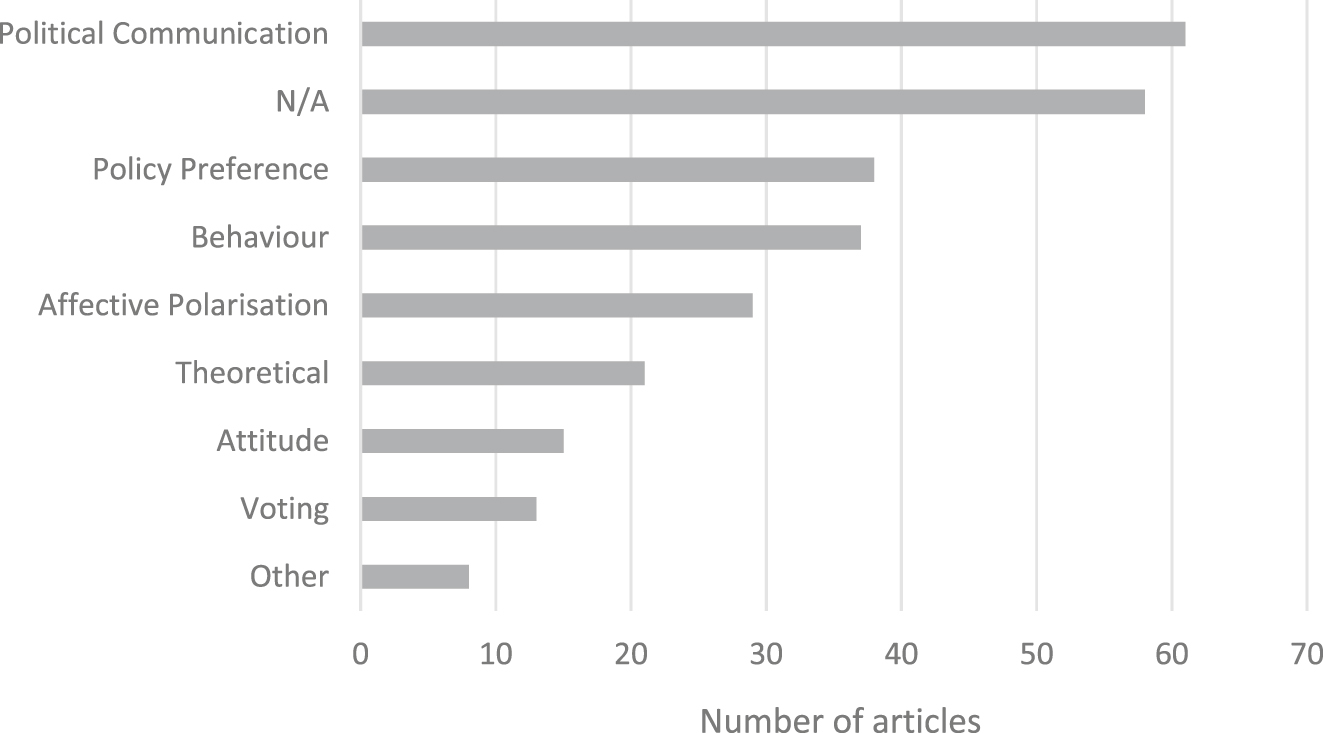

From the coded literature, two findings are striking. First, it becomes evident that political communication, policy preferences and behavioural changes constitute the three main areas among studies analysing the effects of emotions (Figure 1). Secondly, the code N/A scored the second highest number (58) of articles. Literature in this category merely mentions emotion or affect as relevant, yet without methodologically or conceptually integrating them in their analysis. This stresses the growing recognition of emotion among scholars as well as the fact that it is perhaps not as consistently and deeply integrated in the research designs. In the review that follows, I thus focus on the literature that indeed studies emotions. In addition, affective polarisation remains a moderately popular subject of research in which the role of emotion tends to be represented merely through the affective component of this concept. In fact, most reviewed research with a clear reference to policymaking is about explaining how emotions matter when individuals form their preferences about certain policy ideas.

Frequency of codes for ‘content’.

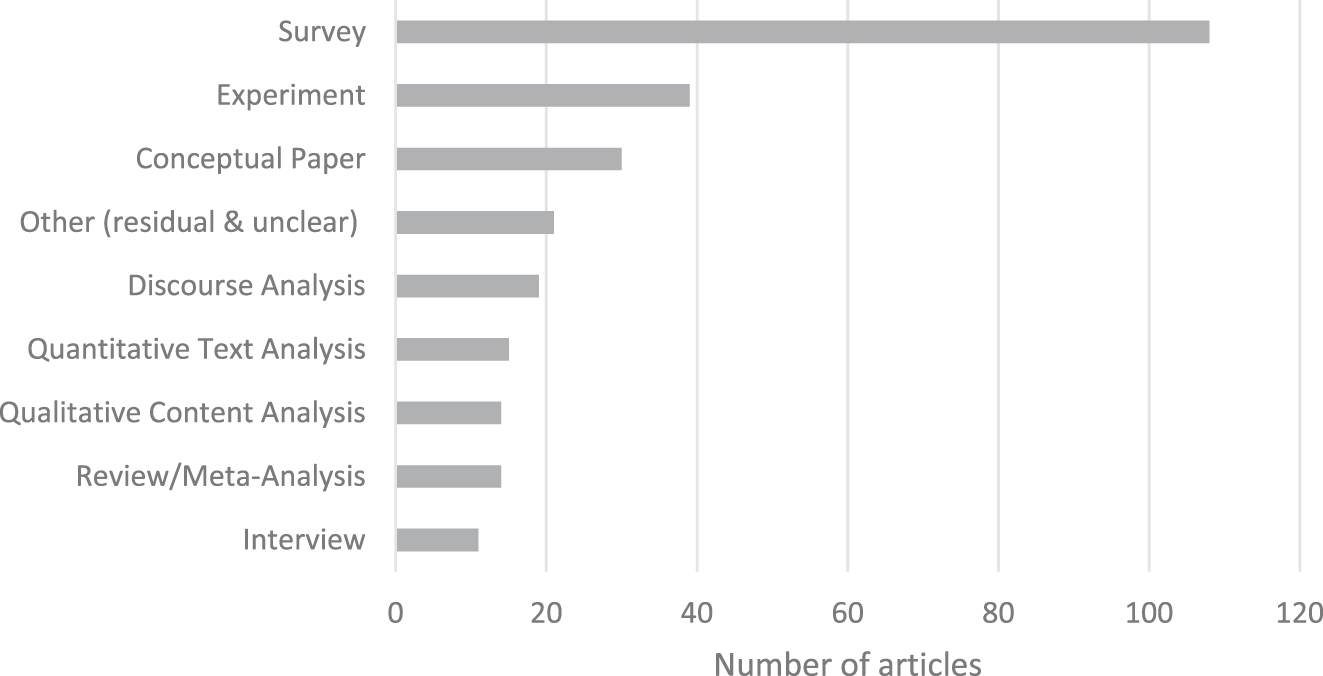

The second graph (Figure 2) is particularly useful in demonstrating the clear overrepresentation of a survey research design in studies on emotions in politics and policy analysis. Whereas a total of 76 articles uses this method, field or laboratory experiments come in second with a significantly less frequent application of 29 times. Bearing in mind the predominance of political communication as a topic of research, discourse analysis, qualitative and quantitative content analysis lead to a combined total of 30 articles.

Frequency of codes for ‘method’.15

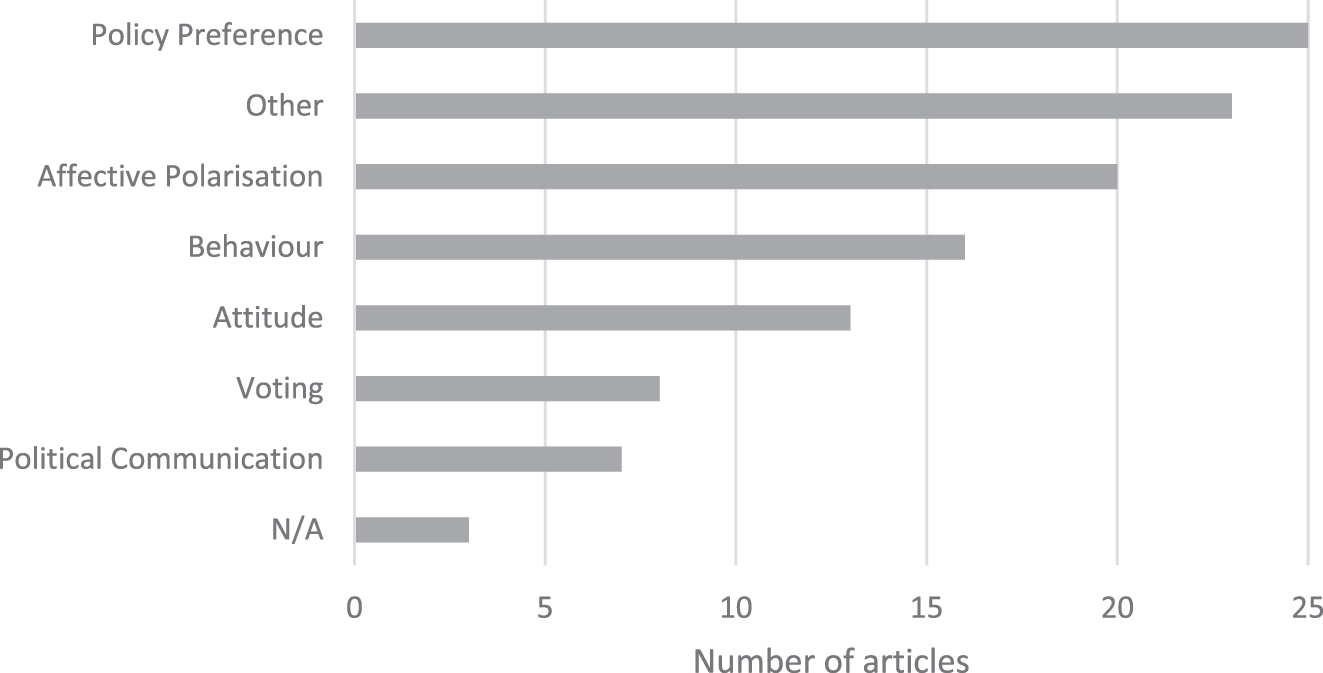

The figure below (Figure 3) illustrates why a survey design might be so widely used as a method by showing to which topic of research it has been applied. These topics are in fact quite diverse and cover three prominent areas within the overall literature, i.e. policy preferences, affective polarisation and behavioural changes. To a lesser extent, political communication was also researched with the help of a survey design.

Frequency of ‘content’ codes for all articles coded with ‘survey’.

All in all, this systematic review presents a useful overview by visualising that even within academic literature on public policies oftentimes published in policy journals, a clear and explicit reference to policymaking, including theoretical frameworks, models or specific concepts from the field of policy studies, is missing. Instead, there is an abundance of research on behavioural patterns, affective polarisation and political communication with only implicit linkages to policymaking. The main exception is policy preferences which displays the perhaps[15] most evident and explicit reference to policy analysis. The following narrative review will allow us to see more clearly, how the studies in the respective categories have analysed emotions and what they have found.

4.2 Insights from the Narrative Review

The following narrative review is roughly structured based on the content categories from the systematic review. First, I introduce key insights from the wider political science literature, including voting behaviour, political communication and, often in connection to these, populism. Although populism was not only a recurring focus in many studies, it is a cross-cutting concept that touches on several topics, e.g. affective polarisation, the role of emotion in populist communication and attitude-formation, which is why it makes sense to explicitly discuss the concept and its relation to emotions here. Secondly, I present work on emotions in policy research, comprising policy theories and preferences as well as the bit of literature that exists on emotion in the process of public policymaking.

4.2.1 Emotions in Political Science Research

Research analysed in this section is certainly relevant for policy analysis, insofar as it furthers the understanding of how policymakers can gain electoral support from certain groups in society and which topics are most beneficial for them to concentrate on. However, it must be stressed that findings on the role of emotions in electoral behaviour, populist success and political communication constitute research with merely an implicit link to policy analysis.

4.2.1.1 Emotions in Voting and Support for (Far-Right) Populists

Existing research on the effect of emotions on voting behaviour is concentrated on the question of turnout. Most studies investigate whether feeling emotional about candidates, parties, voting or politics in general (de Kadt 2017; Dinas et al. 2014; Wang 2019) as well as feeling specific emotions such as anger, fear and enthusiasm (Phillips and Plutzer 2023) lead to higher electoral participation. This strand of literature has indeed found affect as well as discrete emotions to have a positive effect on people’s motivation to vote. Looking at electoral support for specific parties, happiness proves to be a strong predictor for voting for incumbent parties (Ward 2019). Having before been considered to be empirically untestable, scientific results like these verify tacit assumptions about the strong influence that emotions exert on voting behaviour. Studies about the role of emotions in predicting voting behaviour are however often conflated with other concepts, such as populism, partisan identity and polarisation (Arceneaux and Vander Wielen 2013; Diermeier and Li 2019).

In addition to studies that explore the effect of emotions on electoral turnout, there is much research that identifies positive associations between feeling a variety of discrete emotions and voting for far-right populists. Populism in fact constitutes a major area in emotion research, in which especially negative emotions take centre-stage. Looking at fear and anger, Vasilopoulos and colleagues (2019) demonstrate that different emotions may have the opposite effect on the same group of voters. While anger motivates authoritarian and far-right voters to cast their vote for the populist Rassemblement National in France, fear reduced such inclination. Jacobs et al. (2024) confirm the effect of anger on voting for radical parties, but contrary to Vasilopoulos et al. (2019), they find fear (and positive emotions) to have no effect on voting for said party family. Differentiating between different targets of anger, Marx (2020) shows that individuals convert their self-directed anger about their own socio-economic situation into a more enjoyable form of collective anger, which allows them to identify an external actor who becomes the target of negative sentiment and blame. Complementary to purely negative emotions, Versteegen (2024) studies group-based nostalgia which proves a potent predictor for voting for the populist far-right party in the Netherlands. Various discrete emotions have thus been identified as having a positive effect on populist voting even though this is not unequivocally corroborated across different studies.

Other research identifies voters’ perceived proximity to a party to significantly grow in case of an affective shock, i.e. the death of an electoral candidate (Dinas et al. 2014). This underlines the complexity of human attitude formation and behavioural tendencies, as an emotional experience, entirely unrelated to the profile of a certain party, may result in an increase in their public support. There are also more stable patterns of emotional disposition which can be observed in voting behaviour. Generally anxious people prefer politicians who promise them protection and push for policies aimed at eliminating threat and providing safety (Albertson and Gadarian 2015, 101f., 136; cf. Wagner and Morisi 2019). Anxiety can even override partisanship as citizens more strongly support protective policies when afraid, regardless of the party advocating for them (Albertson and Gadarian 2015, 136). At the same time, Albertson and Gadarian (2015) present empirical evidence that specific parties are regarded as more competent in certain areas, which endows them with increased credibility if it is in their field of expertise where a threat is identified (p. 99). These findings indicate that individuals’ overall voting behaviour, their political attitudes and preferences for politicians are all influenced by emotional dispositions as well as incidental emotional states. In this regard, policymakers can successfully propose policy solutions by recognising, addressing and even manipulating emotional reactions to threats, societal groups or problems.

4.2.1.2 Emotions in Political Communication

We do not only feel emotions, we also frequently express them through mimics and gestures as well as by communicating them verbally or in written form. Our individual experience of emotion is thus unarguably shaped by language (Durnová 2022; Schmidt-Atzert et al. 2014, 218). That is why scholars increasingly analyse the use of emotive rhetoric as a useful strategic tool for politicians (cf. systematic review, Section 4.1). We can identify a considerable number of studies that again deal with populism, especially in Europe and the US. These frequently explain populist success through the usage of a type of language that is more emotional than that of their non-populist counterparts (Hopkins in Huddy et al., 2023; Wirz 2018; Verbalyte et al. 2022). Populist far-right parties, thereby make use of social media platforms to increase mobilisation usually in terms of user engagement (Klein 2024). Besides resentment (Abts and Baute 2022) and fear (Flinders and Hinterleitner 2022 [16]), anger is the recurring emotional ingredient in populist communication and considered a key factor for its success (Erhardt et al. 2023; Vasilopoulos et al. 2019). This is not to claim though that positive emotions are absent from populist rhetoric (Tolbert et al. 2018; Wirz 2018, 1128f.). Widmann (2021) thereby stresses that emotions of different valence are appealed to by far-right populists for different purposes, such as the construction of the in-group making appeals to positive emotions and the out-group using negative emotions (p. 176). Especially with regards to policy-related communication, populist rhetoric certainly has an impact on other parties’ communication and on the overall culture of political debate (e.g. Valentim and Widmann 2023). When populist members of parliament make increased use of negative sentiment, their non-populist counterparts resort to oppose this by focussing on positive emotions (ibid.). In general, they appeal to emotions of the opposite valence (Widmann 2022). Mechanisms of emotional adaptation to populists in the context of policies might lead to a mismatch between the emotional quality of a policy proposal and the mood of the target population, which can impede a policy from being implemented (see Cox and Béland 2018; Section 4.2.2.1). Emotions in populist communication indeed appear to be more readily available for analysis and thus comparatively easy to study. However, it must be noted that populist rhetoric is generally more researched than non-populist communication which might lead to a bias in characterising it as naturally more emotional.

Moving on to political science literature which precisely looks at emotional appeals and their strategic use in political communication more broadly, scholars argue that political actors are generally aware of the strategic benefits emotional appeals can have for them in certain contexts and with regards to certain issues (cf. Widmann 2022). That is why they use them in deliberate variation (ibid., 25). More concretely, politicians generally communicate more emotionally in front of an audience of potential voters compared to situations in which they interact with colleagues or experts (Osnabrügge et al. 2021, 897). Emotions thereby function to make a statement or a policy solution more compelling. Besides the type of audience, a politician’s positioning (Yildirim 2024), voter uncertainty and party programme similarities constitute further determinants that make party elites more likely to use emotive rhetoric, especially when addressing the public (Kosmidis et al. 2019). They can furthermore establish what Stapleton and Dawkins (2022) refer to as “affective linkages”. If a member of the preferred party expresses anger or disgust, the electorate as well gets angrier or more disgusted (p. 760, 762). These affective bonds strengthen voters’ support. Research moreover shows that party identification increases when politicians use emotional language (Osnabrügge et al. 2021, 887), a factor that is linked to a growing body of literature on affective polarisation. This development of growing affective partisanship, makes compromise and thus policy compromise less likely. We can therefore note multiple contextual factors that contribute to a political actor’s likeliness of using emotive rhetoric in front of different audiences.

In light of the recent crises and ongoing war and conflict, political crisis communication, as a qualitatively distinct form of communication, has enjoyed increasing scholarly interest. In terms of style, political leaders use more simple and less complex language during crisis (Eisele et al. 2022, 966f.). While presenting scientific evidence remained a powerful strategy to gain authority and trust in times of COVID-19, leaders like German Chancellor Angela Merkel also opted for more emotionally driven frames which predominantly appealed to empathy and solidarity (Kneuer and Wallaschek 2023). In a cross-country comparison, studies however show that there is considerable variation in how political actors make use of emotions as well as in their overall rhetorical style (Boussaguet et al. 2021; Wodak 2021). Political executives do not always attempt to allay fears in threatening times (Eisele et al. 2022, 965). Instead, using anxious rhetoric, they might aid maintaining a momentum of crisis, perhaps due to the uncertainty of the overall situation or possible strategic benefits. Fear appeals in fact represent a double-edged sword that can either let policymakers to be conceived as overwhelmed with crisis management or exactly the opposite, as leaders who are competent to address a given threat (Dingler et al. 2024, 1). In regard to political communication on the issue of terrorism, emotional content including fear, anger, hate, pride and patriotism frequently appeared in political speeches in the US context of post 9/11 (Loseke 2009; De Castella and McGarty 2011). They were rarely contested and, when used in combination with respective symbols, proved to be powerful tools to convey the speaker’s message (Loseke 2009, 517). While political leaders might resort more extensively to emotive rhetoric during crisis, they do not do so at the expense of evidence-based framings or by exclusively appealing to negative emotions. Emotional appeals are thereby considered a strategic tool to be utilised with caution.

Related to this, emotional narratives are also part of communication surrounding conflicts. Terrorist attacks stimulate political speeches containing a multitude of references to fear and anger (Loseke 2009; De Castella and McGarty 2011). Verhoeven and Metze (2022) identify a general pattern according to which discourses around conflict temporally develop from eliciting anxiety to more concrete fear to anger and finally to contempt connected with growing political distrust (p. 233). Given the heightened potential of rising distrust in times of crisis, political figures must be very careful in their choice of alarming as opposed to appeasing rhetoric. Deliberately evoking threat through public communication can indeed successfully mobilize individuals to compliance as well as foster social cohesion (Dingler et al. 2024, 1). Besides a perhaps natural emphasis on negative emotions during times of conflict and insecurity, appeals to positive emotions, such as pride, hope or empathy, are also part and parcel of political leaders’ rhetorical repertoire (Gross 2008). These can promote patriotism and resilience and hence be conducive for political goals. Especially in situations of conflict, politicians therefore strategically communicate emotions though language in a way that makes them appear as most competent to take the needed actions to address a perceived threat.

A heightened use of emotional language cannot however be exclusively observed in the rhetoric of policymakers. Instead, issues of societal relevance are communicated emotionally by a variety of different actors. With regards to debates on late-term abortion, Andsager (2000) demonstrates how a deliberate emotional messaging by activists can set the tone in media discussions. Particularly pro-life activists’ framing of the issue dominated the narratives adopted by journalists, thus determining the terminologies constitutive to the overall debate. When specific negative emotions get associated with the target group of a policy this can indeed complicate policy adoption (cf. Maor 2016, 197). According to another study, climate activists are found to use hope to send a positive message and attract attention and support for their cause (Kleres and Wettergren 2017). Anger, on the other hand, was not universally appealed to but rather dependent on the region, in this case, being used by activists from the Global South (ibid.). In addition to activists lobbying for a specific cause, the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that emotional language is part of the repertoire of politicians and scientists alike (Dingler et al. 2024, 15). This is particularly interesting in challenging the assumption that emotions are only appealed to in order to manipulate the audience. Rather, it appears inherent to all kinds of human interaction, especially those with the purpose of convincing others of a certain goal. Although persuasion and manipulation might be considered quite close in meaning, there is a clear difference in power when it comes to the various actors that strategically attempt to elicit emotions.

In regard to emotion and framing, studies generally investigate which emotions are elicited by which frames.[17] This strand of research concludes that the way in which a political topic is framed impacts which emotions are triggered among its recipients (Gross 2008). However, emotions evoked by certain frames need to ideally be congruent with the receiver’s prior beliefs and attitudes on the respective topic in order to lead to a change in (policy) opinion (Brewer 2001, 60; Gross 2008, 181). Drawing conclusions regarding disruptions in politically relevant behaviour can thus not exclusively be inferred from eliciting emotion. Other studies (Aarøe 2011; Brewer 2001; Clifford 2018; Druckman and McDermott 2008) investigate the effect of certain emotions on the strength, that is the persuasiveness, of different frames. These findings however remain highly context-bound depending on the topic, the distinction between different frame types and between emotions. The selected parameters thereby impact the study which can thus generate inconsistent results about the same emotion.[18] The increase of polarisation has also been positively linked to emotional responses to frames. Clifford (2018) claims that persuasive frames cannot only elicit emotions among its recipients, most importantly anger and disgust, but these can in fact lead to moralization of the recipients’ political attitudes which makes fruitful grounds for polarisation. The strand of literature that deals with emotions in framing bears insightful implications for the process of public policymaking, yet, there is a lack of studies that explicitly study emotional frames, for example, in the communication aimed at defining a problem or setting the agenda for a specific policy solution.

In the context of electoral campaigning, much research has been conducted to examine emotive rhetoric in public communication by electoral candidates. Scholars have identified temporal patterns in the way in which different candidates use emotional rhetoric that appeals to anger, fear, pride and enthusiasm during distinct times of a campaign (Ridou and Searls 2011). While positive emotions, predominantly hope, have a reinforcing effect of support for a person’s preferred candidate, negative sentiment in campaign rhetoric at the same time increases a negative appraisal of the opponent (Just et al. in Marcus, 2007, 252). Eliciting differently valanced emotions can therefore have a double benefit for an electoral candidate of promoting oneself while degrading the opposite candidate. Emotions analysed in campaign rhetoric are often conceptualised and measured in connection to other concepts. While emotional appeals are found to work through candidates’ heightened and strategic usage of moral language (Lipsitz 2018), they also play part in the phenomenon of campaign negativity (Maier and Nai 2020). Maier and Nai (2020), for example, find that campaign rhetoric is most successful, measured in terms of media coverage and reception, when it is “tonally consistent”, that is combining positive messages with enthusiasm and negativity with fear (p. 600). Interestingly, they also show that, by itself, emotional content has a strikingly more pronounced positive effect on media coverage than campaign negativity (ibid.). Even though increased media coverage is not congruent with electoral success, these findings at any rate sit well with the fact that emotions are potent drivers of human action.

Emotional content in political communication has unarguably been studied most extensively, concentrating on populist rhetoric and electoral campaigns, and to a lesser extent, particularities of crisis communication and specific debates. A diverse set of emotions is thereby detected in different forms of language and by different politically relevant actors. Notwithstanding such variety, fear and anger dominate the reviewed literature which naturally leads to identifying a higher salience of these emotions. This, in turn, runs risk of painting a biased picture of reality and perpetuates the overrepresentation of studies on negative affect and emotions (for exception: van Zomeren 2021). A connection to policy studies can here be drawn especially with regards to the strategic use of emotive rhetoric by political actors, the influence of populism on political and policy debate as well as the role of activists in associating specific emotions to certain societal groups.

4.2.2 Emotions in Policy Research

While the previous section illustrates the emphasis of general political science research on emotions with only indirect relevance to policy studies, the following part examines literature with an explicit focus on policy analysis.

4.2.2.1 Emotions in Policy Theories

Public policy theories have indeed a lot to say about rationality in policymaking as well as its limitations. While the approach to decision-making in policy analysis is largely knowledge-centric (Knaggård et al. 2019; Paul and Haddad, 2019, 310), and emotion continues to be an understudied concept, this has been subject of notable criticism from within the discipline. Addressing the limitation of human attention, Baumgartner and Jones (2005, 45ff.) argue that policy change can be hampered by the emotional attachment of a person to existing policy solutions, even though they do not benefit them and policy change would actually improve their situation. Looking at human behaviour driven by emotion thus bears considerable analytical power for policy failure that cannot be explained by models based on rationality. As a response to such critique, emotions have begun to be conceptualized in certain policy frameworks, mainly in the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF), the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) and the Multiple Streams Framework (MSF). Public policy scholars have most extensively attended to the integration of emotion into the MSF. According to Zahariadis (2015), the MSF is in fact the only framework “that pays explicit attention to emotion via the concept of national mood” (p. 467). Introduced by John Kingdon, this framework finds at its foundational level two notions that pave the conceptual way for the integration of emotion, hence making the MSF so popular in this regard. First, as argued by several scholars (Knaggård et al. 2019; Kuhlmann in Zohlnhöfer and Rüb, 2016; Zahariadis 2015), the notion of ambiguity does not only allow for something beyond certainty but already considers the aspect of affect. Secondly, the concept of bounded rationality, which is also present in many decision-making models, describes a characteristic of actors involved in the policy process referring to their imperfect cognition of decision-making as well as imperfect understanding of context and time constraints (Cairney and Weible 2017, 620; Cairney and Jones 2016, 42). This means that policymakers may have a goal in mind without exactly knowing how to achieve it. Even more so, from the very beginning of policy research, comprehensive rationality was rejected as practically impossible which underscores the necessity to better understand emotional reactions to information in general, and policies in particular, and to develop more viable strategies that cast aside “the myth of comprehensively rational action” (Cairney and Weible 2017, 625). Both underlying concepts of ambiguity and bounded rationality render possible a profound integration of emotion into the MSF.

In the context of the MSF, Maor and Gross (2015) have concentrated on conceptualising the “emotional entrepreneur” as a central actor involved in emotion regulation, in determining the dominant feelings of a culture or nation at a specific time (p. 3). The core argument is that policymakers who are aware and willing to strategically use emotion regulation are more successful in their impact on the policy process than those reluctant to do so. Zahariadis (2015) presents empirical support for his argument that, under certain circumstances, fear strongly and consistently impacts the phase of the policymaking process in which, according to the MSF, specific problems are coupled with respective policy solutions (p. 466, 477). Knaggård (2015), on the other hand, concentrates on the stage in which a problem is framed as such. According to her, specific actors may prioritise the emotional aspect of a problem frame whenever knowledge is limited (p. 457). Similar to the framing of a certain problem, Cox and Béland (2018) have focussed on the emotional quality, what they term valence, of a specific policy idea. They argue that policy change is more likely when there is congruence between the valence of a policy idea and the public mood, which can both be manipulated by policymakers. Methodologically, the authors underline the benefit of borrowing from other disciplines, such as social psychology, in enriching the research designs in policy analysis (p. 324).

Another policy framework which has been used to study the role of emotion in policymaking is the Advocacy Coalition Framework. The concept of the devil shift and its antonym angel shift refer to the distorted, affective perception of political opponents as well as coalition members during the process of policymaking (Vogeler and Bandelow, 2018, 718). Albeit not being explicitly about emotions, they are indeed at the conceptual basis of these ideas (cf. Fullerton and Weible 2024, 372). Based on the ACF, Fullerton and Weible (2024), for example, examine the communication by activities during legislative hearings about a specific bill. They find that activists are more successful in convincing policymakers when using negative emotional appeals contrary to positive ones and as long as they were congruent with core beliefs. Another study (Gabehart et al. 2023), also looking at US state-level legislative hearings, finds both anti and pro advocacy groups to successfully tap into emotions, with negative emotional appeals being more potent in persuasion.

There is furthermore literature using the Narrative Policy Framework in their analysis of the role of emotions in policy change. Some however treat emotions in the analysed communication rather superficially (McBeth and Lybecker 2018) or investigate policy cases like agri-food legislation which is characterised by less emotional rhetoric (Vogeler et al., 2021). Whilst the latter constitutes an interesting finding in itself, showing that certain topics appear to stir less affective reactions than others, these studies tend to focus on other aspects of the selected frameworks, in this case elements of policy narratives, at the cost of researching emotions. Addressing this shortcoming, certain scholars advocate for a more thorough integration of affect into policy models like the NPF (Pierce et al. 2024). What can be derived from these contributions is that emotions are no longer seen as alien to the process of public policymaking. While the MSF enjoys particular focus by policy scholars and has been more thoroughly refined at the conceptual level, the ACF and the NPF more often form the theoretical basis in empirical studies. We thus have a flexible framework open for conceptual adjustments on the one hand and two frameworks with specific elements that are particularly helpful in empirical appliance on the other.

4.2.2.2 Emotions in the Process of Public Policymaking

As demonstrated in the previous section, the process of adopting a policy bears multiple opportunities to study emotions. Especially in light of the various steps that include deliberation and communication of problems and possible solutions, policymakers and other actors have a chance to push for their policy idea by, amongst other strategies, using and appealing to emotions (Maor 2024, 930f.; see also Emotional Policy Discourse, Paterson 2019). With regards to policy conflict, Verhoeven and Metze (2022) have analysed emotional storylines in Dutch newspapers to demonstrate how discrete emotions are elicited at different times during the policy process, which can potentially lead to an escalation when nurturing especially anger storylines. Besides literature on how emotions affect human behaviour, earlier literature related to policy conflicts presents similar findings (Verhoeven and Duyvendak 2016). In the broader context of climate change and energy policies, Widmann (2024) shows that different policymakers appeal to discrete moral emotions depending on whether they oppose or support the local construction of wind turbines.

Besides political actors, communication by citizen initiatives and other interest groups has certainly been researched and shown to make use of emotions in public policy consultations aimed at convincing policymakers of their stance on a certain issue (Fink et al. 2023; Fullerton and Weible 2024; Gabehart et al. 2023; Pierce et al. 2024). A comparative analysis of different policy areas indicates that the choice of emotions in interest groups’ communication during legislative hearings is dependent on various factors (Gabehart et al. 2023). For example, advocacy groups seeking policy change rather than continuation use a wider range of different emotions regardless of their stance and the policy area (p. 16). Comparing public consultations to a policy proposal for a power line construction, Fink et al. (2023) find that the communication included more emotive appeals when referring to concrete power lines, with a dominance of negative emotions. Looking more closely at the different speakers involved, citizens’ consultations comprised higher levels of affective language than those of organisations, which could also be seen in the greater variety of emotions to which citizens appealed (p. 489). Yet, in both types of public consultations, emotive rhetoric was present. In the special case of Swiss public policymaking, Kühne and colleagues (2011) find that political communication prior to a popular vote on a supposedly dry and complex topic, such as corporate taxation, successfully incorporated emotionally appealing language. In contrast, Vogeler and colleagues (2021) found that emotive rhetoric was less popular among members of the EU-parliament in debates on agri-food policies. A comparison between these two studies is however complicated given the lack of empirical findings showing causality as well as evident differences in policymaking level.

Moving away from policy communication to policy reactions, Maor (2016) introduces the concept of emotion-driven negative policy bubbles to underline the role that emotions play in the systematic underinvestment in a policy instrument. When negative emotions get attached to a policy’s target group, this can lead to policymakers insufficiently investing in policy solution to address an important societal risk, as visible in the AIDS legislation during the 1980s in the US (p. 194). Regarding policy design, Durnová and Hejzlarová (2018) make another interesting contribution to emotions and target groups. Using an interpretivist survey, they work out specific emotional tensions of Czech single mothers that result from public policies affecting them. The authors therefore argue that emotions of target groups need to be recognised in the policy design in order to avoid poor policy outcomes.

The key point made in this subsection is that research with an explicit focus on the policymaking process is highly limited and by and large analyses institutionalised deliberative procedures in which problems and respective policy solutions are debated. Scholars thereby concentrate more on interest groups’ contribution than policymakers’ rhetoric or media communication.[19]

4.2.2.3 Emotions and Policy Preferences

As also illustrated in the systematic review (see 4.1), studying the relationship between emotions and policy preferences can be identified as the most prominent object of research in regard to public policy. Assessing a central argument of Affective Intelligence Theory, a few studies focus on a topic indirectly related to policy preferences. The idea of ‘policy learning’, which describes an individual’s motivation and action to acquire new information about an issue, is understood to be promoted by anxiety given that this emotion is triggered by the surveillance system (cf. Marcus in Sears et al., 2003, 203). Policy learning allows for conclusions about which topics appear salient and significant for a person as one can argue that the more important an issue is, the more likely is the formation of an attitude about it. In literature on policy learning, anxiety is indeed found to be a driver of policy learning (Lablih et al. 2024), whereas disgust has the opposite effect (Clifford and Jerit 2018). In addition to analyses on these indirect linkages, there is a considerable number of studies published on the relationship between experiencing certain emotions and having certain policy preferences. Already touched upon in the previous section on political communication, an emotional framing of a problem has the potential to lead to policy change. Investigating discrete emotions, anger is frequently found to be associated with a preference for stricter, more punitive policies (Pierce et al. 2024; Renström and Bäck 2021). With regards to foreign policy, Gadarian (2010) shows how emotionally charged messages prime individuals to be more supportive of hawkish foreign policies. This is corroborated by research on increased anger which is positively linked to a hardline foreign policy attitude (Kupatadze and Zeitzoff 2019). Both studies also see emotions working through and mediating the threat perception of individuals, which is a very important predictor for attitudes on protective policies. This mediating role of emotion does however tend to complicate singling out the effect of, for example, anger. Certain studies therefore specify that emotions only indirectly impact distinct policy opinions and behaviour by mediating the effect of other factors (Brader et al. 2008; cf. Jacobs et al. 2024, 22f. on voting). Other research stresses that findings are conditional on belief congruence (cf. Brewer 2001, 60; Gross 2008, 181). Similar to voting for candidates perceived as protectors, anxiety makes people more supportive of policies that they deem protects them from imminent threat (Albertson and Gadarian 2015, 101; cf. Wagner and Morisi 2019). When it comes to inter-group threat, often framed or perceived regarding migrant groups, anger can as well predict stronger support for policies limiting immigration (Cottrel et al. 2010). Comparing anger and sadness, Small and Lerner (2008) find that incidental emotions, the personal experience of feeling something at the time of opinion formation, indeed spill over to one’s policy preference, in this case social welfare preference. While anger decreases favouring such policy measures, sadness makes people more supportive of it.

Small and Lerner’s article (2008) in fact shares a methodological measurement with the majority of studies in the sense that emotions are examined by priming these through images or short bodies of text that stimulate participants’ imagination. There are some exceptions in the reviewed literature in which not incidental emotions are studied but emotional disposition, in other words, a person’s general sensitivity towards feeling specific emotions. For example, Aarøe and colleagues (2017) find that people with dispositional disgust more often oppose immigration, hence favour stricter migration policies. In fact, disgust is found to be linked to a variety of different policy attitudes ranging from health issues (Clifford and Jerit 2018; Georgarakis 2023) and various other issues of state protection (Kam and Estes 2016) to issues of morality, i.e. gay marriage or abortion (Cottrel et al. 2010; Inbar et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2011). These analyses highlight that dispositional as well as incidental emotions unrelated to a specific political topic might nonetheless impact the opinion an individual forms about said topic. In addition to this, Jefferson (2023) investigates the effect of shame, an emotion rarely studied, on social policies. He shows that black US citizens, who are generally more ashamed of their race, are more supportive of punitive policies targeting their own racial group. Shame and other emotions that are deemed more complex have a huge unused potential in generating novel knowledge in the multifaceted dimension of affect in public policymaking. Such emergent studies mark an interesting avenue for further investigation into this direction.

4.3 Emotions in Political Science Research on COVID-19

Before concluding this review, I seek to illustrate the main areas of focus within policy-related research on emotions by using the pandemic as a heuristic, exemplifying public policymaking during crisis. I use COVID-19 as a case for illustrative purposes to corroborate the findings from the critical work of the systematic and narrative review, namely the thematic emphases as well as the neglected areas in the literature on the role of emotions in public policymaking. Three key attributes make COVID-19 a useful case: comparable, recent and topical. Firstly, political responses to Covid, e.g. introducing curfews, limiting contacts, implementing vaccination plans, are to some extent comparable across state borders and cultural contexts due to its very nature of being a global health threat (World Health Organization – WHO 2020). Secondly, it will be hard to find a more recent event[20] that has furthermore spurred extensive political communication as well as resulted in a considerable number of different policies. Thirdly, in an age of multiple insecurities and crises, policies aimed at eliminating or mitigating an identified threat are becoming increasingly important. In this world, intellectual interest in security is growing across disciplinary boundaries (Bourbeau in Bourbeau 2015). While there is a great variety of different issues that can potentially be framed as related to threat and protection (cf. Bonansinga 2022), a global pandemic constitutes a natural contender for such protective policymaking with a great potential to generate crucial insights for policymaking.

Covid has had profound impacts not only on health but also a range of other aspects of our lives. Despite the comparable recency, scholars from various disciplines have extensively studied the pandemic regarding communication (e.g.: Lilleker et al. 2021a,2021b; Montiel et al. 2021; Wodak 2021), risk perception (Plohl and Musli 2021; Wise et al. 2020) and institutional trust (Jørgensen et al. 2021; Plohl and Musli 2021). There is also a sufficient number of studies that concentrate on the role of emotions during the crisis (e.g.: Mehlhaff et al. 2024; Nguyen et al. 2022; Vasilopoulos et al. 2023). When it comes to political science and policy-related research, we can observe a similar pattern in the literature investigating the role of emotion during the pandemic to that of the overall research on emotions in this field. Empirical studies on this topic follow four main foci: (i) policy preferences, (ii) behavioural change, (iii) attitudinal change, (iv) political communication.

In regard to policy preferences, fear stands out as the most salient discrete emotion which has been studied in terms of its relationship to individual support for protective, more restrictive Covid-related policies. Besides fear, which is consistently shown to be linked to a higher support for protective policymaking (Merrolla et al. 2023; Renström and Bäck 2021; Vasilopoulos et al. 2023), two studies also examine the same effect for sadness (Merrolla et al. 2023) and disgust (Georgarakis 2023). By distinguishing between different protective policies related to the pandemic, Renström and Bäck (2021) find that whereas fear is linked to approving policies aimed at reducing the spread of the Coronavirus, anger is positively associated with favouring policies on justice violations. As visible in the overall literature, a variety of discrete emotions is linked to specific policy preferences during the pandemic without making any claims about causality.

Extant research also shows how emotions, mainly fear, relate to engaging in protective behaviour aimed at diminishing the risks posed by the virus. This differs indeed from studies in the overall discipline of political science which predominantly illuminate the relationship between emotions and voting behaviour. Certain studies overlap with policy preferences (Georgarakis 2023; Merrolla et al. 2023) given that both, policy proposals and individual behavioural measures, share the central aspect of protection. Scholars evidently agree on the positive effect of being afraid of the virus on compliance with suggested health-related measures (Brouard et al. 2020; Harper et al. 2021). Heightened levels of fear therefore do not only increase support for protective, more restrictive policies but are also positively associated with engagement in protective behaviour. Other scholars investigate the effect of fear on governmental trust (Hrbková and Kudrnáč 2024) or additionally analyse the relationship between values and compliance with protective measures (Nerini et al. 2021). Here again, we can observe a simultaneous treatise of emotions and further concepts leaving emotion to have only an indirect influence on behavioural patterns.

The third aspect that academic research has looked at concerns attitudes and how these change under the influence of specific emotions linked to the Covid-19 pandemic. Attitudes are hereby used as an umbrella term for different attitudinal changes which comprise attitudes towards democracy and, contrarily, authoritarian alternatives (Erhardt et al. 2023), to EU identity (Nicoli et al. 2024) and to notions of nationhood (Wamsler et al. 2021). According to Filsinger et al. (2023), anger triggered by Covid is positively linked to support for populist parties in several EU countries while fear has the opposite effect. In agreement with this, fear is also shown to be associated with support and positive evaluations of incumbent governments, with studies often referencing the rally-around-the-flag effect (Dietz et al. 2023). Contrary to such strengthening of the political centre, Nguyen and colleagues (2022) find anger caused by the pandemic to have the opposite impact of moving the public to the fringes and increasing affective polarisation. This set of studies evidently mirrors the emphasis in overall political science research on the relationship between emotions and populist support. It moreover speaks to public discussions about (possible) effects of the pandemic on democracy.

Finally, political science scholars place emphasis on the ways in which emotions are appealed to in political and media communication about the pandemic. Belonging to a special type of rhetoric, namely crisis communication (Lilleker et al. in Lilleker et al. 2021a,2021b), political leaders have opted for different strategies when speaking about the threat posed by Covid. They may use empathy appeals (Elsheikh in Lilleker et al., 2021) and apply more emotional frames, while also centring a rather neutral approach that concentrates on presenting evidence (Wodak 2021). Although emotions are useful tools for politicians, they are neither used across the board nor without reservation. In an interesting complementation to literature on populism, Widmann (2022) identifies a switch in populist and incumbent parties’ communication regarding the Covid-crisis. He shows that whereas, during Covid, the former changed the emphasis on negative sentiment in regular times for positive emotions, such as hope, the latter does the opposite of switching to more negative affective language (p. 844). Making use of emotive rhetoric is however not a question of which formal role a speaker performs. Scientist equally as politicians are found to make use of emotional appeals to convince their target audience of an argument (Dingler et al. 2024). A clear majority of studies examines the emotional elements in elite communication, with only very few that investigate how these are perceived by the targeted audience (cf. also Widmann 2022, 843f.). Mertens and colleagues’ article (2020) constitutes an exception as they show that increased exposure to news related to the pandemic leads to higher levels of fear among the recipients. In general, research on emotions in Covid-related communication focuses on different strategies employed by various, mainly political, actors in order to address the threat posed by the virus. As noted, there is very little on the demand side.

This short excursion on political science and particularly policy-related research on the role of emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the focus of certain themes which can also be observed in the broader literature on emotions, as demonstrated in the previous parts of this review. Topics of policy preferences, behavioural patterns and emotional rhetoric are predominant with an evident overrepresentation of studies on emotions’ effect on policy preferences directly and indirectly through compliance with protective measures. Analysed studies on the pandemic moreover mirror a pattern of US-centrism and correlational empirical findings. Fear is thereby the, perhaps naturally, predominantly studied emotion. To my knowledge, there have not yet been any studies on when and how emotions feature in the process of (protective) policymaking during the pandemic, as research overall is scarce on policymaking.

5 Conclusions

Emotions are integral to human life and thus to political life. An increasing body of literature in political science research dealing with the role of emotions in political phenomena points to this understanding. This growing and diversified interest requires a systematic and comprehensive state-of-the-art on specific areas within the broader discipline. This review sets out to provide such a critical exploration of existing scientific knowledge in regard to policy analysis. More precisely, it aims at answering the question of what exactly do we know about the various ways in which emotions impact political phenomena, and more specifically, public policymaking. Following a two-fold strategy, I conducted a systematic and a narrative literature review in order to complement the valuable overview with more detailed findings. This approach proves beneficial in terms of allowing for a structured and critical synthesis of an area (policy studies) in which research interest might be growing, but knowledge acquisition overall is still in its early stages. The final corpus consists of 264 reviewed and hand-coded pieces of literature, mainly peer-reviewed journal articles, among which 66 pieces of literature were also qualitatively analysed in depth.

This review shows that even though studies on the role of emotions in politics per se are continuously rising as well as diversifying, emotions with regards to public policymaking have been studied significantly less. Even with ‘policy’ included in the search string and in several journal names, many results from the systematic review concern polarisation and partisanship and, to some extent, conceptualisations of emotion and emotional practices which have comparatively little to do with concrete public policymaking. Although we can frequently detect a certain sense of relevance for policy analysis, those studies with a clear focus on the topic concentrate on a few specific aspects. The literature on emotion in political communication perfectly exemplifies this tendency. While scholars have analysed the usage of emotive rhetoric focussing predominantly on populist communication (Erhardt et al. 2023; Schumacher et al. 2022; Widmann 2022) and electoral campaign speech (Lipsitz 2018; Maier and Nai 2020), they have only occasionally explored emotional communication as part of (the process of) public policymaking (Fink et al. 2023; Fullerton and Weible 2024; Pierce et al. 2024). An exception to this is the work of interpretivist scholars and critical policy studies, which concentrated earlier and more extensively on the analytical merit of integrating emotions in studying policy-related communication (Durnová 2022; Paterson 2019; Verhoeven and Duyvendak 2016). The two main areas in studies, that are explicitly anchored in policy research, are policy preferences and policy debates in legislative hearings. Another issue that has been explored thoroughly and beyond political science is emotions in decision-making. However, this has been done mainly at the individual level regarding voting or engagement in protective behaviour, thereby missing a profound understanding of decision-making at the level of policymaking.

Based on the findings of this review, I argue that studies on emotions in policymaking are still loosely distributed and not systematised, often without embedding the results into extant theory, hence lacking an adequate conceptual contribution to policy analysis. Considering this, policy scholars should prioritise research that clearly, concretely and explicitly deals with public policymaking, including references to theories, models and frameworks as well as investigating the effects of emotions at different stages of the process of policymaking. With the exception of emotional appeals in legislative hearings on specific policy proposals, the process of policymaking is a clearly identifiable blind-spot in existing empirical studies.

The arguments made here are rooted in the design of the review which evidently bears some limitations. First, the systematic review comes with certain caveats. Given the nature of Web of Science, only articles from peer-reviewed journals could be reviewed while research published in different forms of output is neglected. This seems permittable considering that the narrative review includes all kinds of literature types, and given that Web of Science grants access to an extensive database of recent empirical studies which is most essential for the purpose of providing a current state-of-the-art. This search platform moreover provides useful additional information on the literature and allows for an easy extraction of sources. Regarding my selection of data, limiting the review to articles from journals of a specific impact factor naturally missed certain scientific work. However, time restrains made a more comprehensive review unfeasible. Most importantly, for the purpose of identifying trends, overrepresented areas and blind-spots, such reduction seems appropriate as we can expect similarities in disregarded lower-ranked journals. Finally, coding the literature largely only according to the title and abstract might lead to miscomprehension of some thematic foci or methods used. Besides considerations rooted in feasibility, the information provided in the abstract should introduce the reader to the study and enable them to draw correct conclusions about research topic and method. Thus, the selected scope of input should generally suffice for coding. Additional information was however also considered for some of the unclear coding for method (see footnote 15). When it comes to conducting a narrative review, one always requires to be cautious of a biased selection of literature. By deliberately considering studies from very different times of publication and based on different underlying theoretical assumptions, I aimed at mitigating such bias. Through snowballing as well, I tailored my search to important aspects of politics and policymaking and looked at recurring, often-cited literature that proved influential in the research area of interest. This procedure enabled me to avoid neglecting relevant topics while alleviating potential biases as well as possible.

From my perspective, the crucial take-away from this literature review is the fact that political scientists and increasingly policy scholars as well are working on generating a more complete picture of the world of public policymaking. Even though scholars need to address areas that have largely been neglected so far, there is a vibrant interest in the expansion and deepening of existing knowledge on the demand-side of policymaking, on how policymakers discuss, design, adopt and evaluate policies, as well as on the supply side, on how members of society perceive, understand and evaluate policy measures and their effects. Such efforts can only be commended as they foster hopes for more comprehensive and critical policy research.

Funding source: European Union

-

Research funding: This work was supported by European Union under grant 10.3030/101132433. Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or Research and Executive Agency (REA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

References

Aarøe, L. 2011. “Investigating Frame Strength: The Case of Episodic and Thematic Frames.” Political Communication 28 (2): 207–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2011.568041.Search in Google Scholar

Aarøe, L., M. B. Petersen, and K. Arceneaux. 2017. “The Behavioral Immune System Shapes Political Intuitions: Why and How Individual Differences in Disgust Sensitivity Underlie Opposition to Immigration.” American Political Science Review 111 (2): 277–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000770.Search in Google Scholar

Abts, K., and S. Baute. 2022. “Social Resentment, Blame Attribution and Euroscepticism: The Role of Status Insecurity, Relative Deprivation and Powerlessness.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 35 (1): 39–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2021.1964350.Search in Google Scholar

Albertson, B., and S. K. Gadarian. 2015. Anxious Politics Democratic Citizenship in a Threatening World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139963107Search in Google Scholar

Andsager, J. L. 2000. “How Interest Groups Attempt to Shape Public Opinion with Competing News Frames.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 77 (3): 577–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900007700308.Search in Google Scholar