Abstract

Reductive alkylation of the carbonyl group of carbohydrates with fluorescence or ionizing labels is a prerequisite for the sensitive analysis of carbohydrates by chromatographic and mass spectrometric techniques. Herein, 1-(2-aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium tetrafluoroborate ([MIEA][BF4]) was successfully synthesized using tert-butyl N-(2-bromoethyl)carbamate and N-methylimidazole as starting materials. MIEA+ was then investigated as a multifunctional oligosaccharide label for glycan profiling and identification using LC-ESI-ToF and by MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry. The reductive amination of this diazole with carbohydrates was exemplified by labeling N-glycans from the model glycoproteins horseradish peroxidase, RNase B, and bovine lactoferrin. The produced MIEA+ glycan profiles were comparable to the corresponding 2AB labeled glycan derivatives and showed improved ESI-MS ionization efficiency over the respective 2AB derivatives, with detection sensitivity in the low picomol to the high femtomol range.

Introduction

N-glycans decorating the surface of glycoproteins participate in protein-protein interactions or in interactions between glycoproteins and other large biological molecules, therefore delicately regulate different cellular processes [1], [2]. The full comprehension of the structure of these carbohydrates is the basis of fully understanding the functions of glycoproteins, the detection and analysis of these N-glycans from minute amounts of samples is challenging. Mass spectrometry (MS) coupled with liquid chromatography (LC) is currently the first choice for the analysis of N-glycan structure and composition. Although the latest generation of electrospray ionization-time of flight (ESI-ToF) MS allows the profiling of N-glycosylation directly on the native, intact protein. However, this technique is still limited by its relatively low sensitivity, especially when screening for N-glycans with a low abundance [3]. The routine procedure of N-glycan profiling is still based on analysis of derivatized N-glycans by chromatographic and/or mass spectrometric techniques.

In general, N-glycan analysis starts with an enzymatic release of the N-glycan portion from glycoproteins [4], [5]. The reducing end of the released N-glycans can be then functionalized to enhance the detection sensitivity by using reductive amination [6], hydrazine-mediated release [7] or oxime formation [8]. 2-Aminobenzamide (2AB) is an example of a commonly used compound for functionalizing N-glycans by reductive amination and subsequent chromatographic glycan analysis using fluorescence detection [9], [10]. However, due to its poor ionization capability, 2AB-derivatized oligosaccharides show relatively low signal intensities in electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). Recently, a series of other amines have been described to have higher ionization capabilities than 2AB, namely 4-amino-N-[(2-diethylamino)ethyl]benzamide (procainamide) [10], 2-hydrazino-4,6-bis-(dipropylamino)-s-triazine (n-Pr2N) [11], and aminoquinoline-based derivatives (RapiFluor) [12]. Although these derivatization compounds demonstrated a significant improvement in the ionization of N-glycans, there is still space for improvement. For example, the separation of procainamide-labeled N-glycans was described to be more challenging when compared to 2AB-labeled N-glycans using normal-phase chromatography (NP-HPLC) [13]. For RapiFluor-labeled N-glycans, an additional purification step was needed to remove sodium 3-[(2-methyl-2-undecyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)methoxy]-1-propanesulfonate from the reaction mixture [12]. The development of novel derivatization agents for N-glycan analysis, which is suitable for both chromatographic separation and sensitive mass spectrometric detection is therefore highly desirable.

Ionic liquids (ILs) are salts which exist in liquid form at room temperature, and usually consist of organic cations (i.e. 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium or N-alkyl pyridinium ions) and inorganic anions (i.e. tetrafluoroborate or hexafluorophosphate) [14]. ILs have attracted great interests in organic chemistry due to their properties since first reported in 1914 [15]. The high polarity and solubilizing properties of ILs can accelerate reactions involving cationic intermediates, which was applied in acetylation- [16], esterification- [17], benzylidenation- [18] and glycosylation reactions [15], [19]. Moreover, ILs are also widely applied in analytical chemistry, taking advantage of their low vapor pressure, good thermal stability, and their miscibility with both water and organic solvents. ILs were also successfully applied as carrier matrices for detection of polymers, peptides, sugars in matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF MS) [20], [21], [22], [23].

Recently, ILs containing glycosides have been synthesized and proved to be very versatile probes for the sensitive detection of biochemical glycosylation reactions [24]. The Galan research group which developed these 1-methylimidazole/BF4-based glycan probes (I-tags) allowed the sensitive monitoring of enzymatic glycosylation by recombinant β-1,4-galactosyltransferase [25], or the detection of enzymatic fucosylation reactions in human milk samples [26]. Motivated by these results, we decided to design a novel tag based on N-methylimidazolium, containing an amino group which can also functionalize native N-glycans via reductive amination.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

tert-Butyl N-(2-bromoethyl)carbamate was purchased from J&K (Shanghai, China). N-methylimidazolium, 2-aminobenzoic acid (2AA), dextran (Pharmacy grade, 1500 Da), maltotriose, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, and RNase B were supplied by Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Acetonitrile used for HPLC analysis was purchased from Merck (Nanjing, China). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was obtained from BioDuly (Nanjing, China). N,N-Diacetylchitobiose was obtained from Carbosynth Ltd (Compton, UK). Lactoferrin from bovine milk was purchased from Wako Chemicals (Osaka, Japan). Anhydrous maltose was obtained from Ryon (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals used in this study were bought at the highest grade from commercial suppliers without further purification or modification. Recombinant PNGase H+ and PNGase F were expressed and purified as reported previously [27].

Synthesis of 1-(2-aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazole-3-ium bromide [MIEA][Br]

tert-Butyl N-(2-bromoethyl)carbamate (1.232 g, 5.5 mmol) was reacted with N-methylimidazolium (0.410 g, 5 mmol) in anhydrous CH3CN and t-BuOH [25 mL (4/1, v/v)] in a round bottom flask with reflux at 80°C for 2 days under a nitrogen atmosphere. Any unreacted starting materials were removed by washing with ethyl acetate (two times), and the product was dried under reduced pressure resulting in a light yellow viscous liquid.

Synthesis of 1-(2-aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium tetrafluoroborate ([MIEA][BF4])

The [MIEA][Br] salt (0.865 g, 4.2 mmol) was stirred with KBF4 (1.1 eq.) in water for 24 h at room temperature. After 24 h, the reaction mixture was filtered and dried under vacuum. Then the compound was washed with dichloromethane and ethyl acetate, respectively. After drying for 6 h under vacuum at 80°C, the expected ionic liquid [MIEA][BF4] was obtained.

Enzymatic release and purification of N-glycans

Ten milligrams of either RNase B or bovine lactoferrin glycoprotein was suspended in 500 μL water. Twenty-five microliter of sodium phosphate buffer (500 mM, pH 7.5), 25 μL sodium dodecyl sulfate (2% w/v) and 2-mercaptoethanol (3% v/v) were added in the solution. The mixture was first heated at 95°C for 10 min. After cooling the reaction mixture down to room temperature, 40 μL of a Triton-X100 solution (10% w/v) and recombinant PNGase F (1 mU) were added in the reaction mixture. Then the reaction mixtures were incubated for 16 h at 37°C, respectively.

N-glycans from horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were releases as described previously [28], [29]. In brief, HRP glycoprotein (10 mg) was dissolved in 500 μL water, and 25 μL of sodium citrate buffer (500 mM, pH 2.5) was added to the solution. The glycoprotein solution was denatured by heating for 10 min at 95°C. After cooling the reaction mixture back to room temperature, 1 mU of recombinant PNGase H+ was added. Then, the reaction mixture was incubated for 16 h at 37°C, and the supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 14 000 g for 15 min and purified with a ready-made solid-phase extraction carbon column (Supelco Supelclean ENVI Carb, 500 mg cartridge). The SPE column was equilibrated with the 3 mL of deionized water, and the enzymatic reaction mixtures loaded to the SPE column. After washing the column with 3 mL of deionized water, the N-glycans were eluted in 1 mL of aqueous acetonitrile (40% v/v) containing 0.1% TFA (v/v) and dried using centrifugal evaporation.

Derivatization of oligosaccharides and N-glycans with MIEA+

An aliquot (10 μL) of MIEA+ derivatization solution [70 mM (MIEA)(BF4) and 0.1 M sodium cyanoborohydride in dimethyl sulfoxide/acetic acid solution (7:3, v/v)] was added to each sample and vortexed until completely dissolved. This mixture was heated at 70°C for 4 h.

UPLC-MS profiling of oligosaccharides and N-glycans

Chromatographic analyses were performed on a Shimadzu LCMS 8040 system (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) consisting of an LC-30AD pump equipped with a low-pressure gradient mixing unit and a SIL-30AC autosampler coupled to the ESI mass spectrometer. Analyte separation was achieved by HILIC separation (Hydrophobic interaction liquid chromatography) using an ethylene-bridged hybrid (BEH) UPLC column (Waters Acquity glycan column, 1.7 μm, 2.1×150 mm). Samples were analyzed at a column temperature of 60°C. The flow rate was adjusted to 0.4 mL/min, and aqueous NH4COOH (pH 4.5, 50 mM, solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B) were used as mobile phases. The separation of the MIEA+-derivatized oligosaccharides was achieved using the following gradient elution: A linear gradient of 88–53% of solvent B was applied from 1.5 to 35 min, then decreased to 0% and held for 0.5 min. Solvent B was then increased to 88% and the column was equilibrated with the initial conditions for 3.5 min. For the separation of MIEA+-derivatized N-glycans, a slightly different elution gradient was used: A linear gradient of 78–60% of solvent B was applied from 0 to 6 min and decreased to 45% over 44.5 min followed by a further decrease to 30% over 2 min, then held at 30% for 2 min. The relative amount of solvent B was then increased to 78% and the column was equilibrated with the initial conditions for 6.5 min.

MALDI-ToF mass spectrometric analysis

Derivatized samples were diluted 20-fold with deionized water, then analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF-MS). A Bruker Autoflex Speed mass spectrometer (equipped with a 1000 Hz Smartbeam-II laser) was used for analyzing the samples using 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid as matrix. Mass Spectra were processed using Bruker Flexanalysis software version 3.3 and were annotated manually.

NMR analysis of MIEA+

1H and 13C spectra were obtained on a 400 MHz Bruker BioSpin NMR spectrometer fitted with a 5 mm PABBO BB-1H/D Z-GRD probe at 296 K. The data were processed using MestReNova version 8.1.

Sample quantification

MIEA+-maltose was quantified using the quantitative monosaccharide analysis protocol developed by Stepan et al. [30], with optimized conditions [31], [32]. MIEA+-maltose was first isolated using HILIC-UPLC, dried by vacuum concentration, and then resuspended in 100 μL deionized water. Ten microliter was taken out and hydrolyzed with 1 mL of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, 4 M) at 110°C for 6 h. The hydrolyzed sample was dried by vacuum concentration, and residual TFA was removed by three cycles of adding/drying of methanol (0.5 mL) using vacuum centrifugation. The dried sample was then resuspended in 5 μL of aqueous NaAc solution (48.2 mg/mL). Ten microliter of 2AA solution (3 mg of 2AA and 30 mg of sodium cyanoborohydride in 1 mL of 2% (w/v) boric acid in methanol) was added, mixed thoroughly and incubated at 80°C for 60 min. The derivatized sample was diluted 10-fold with deionized water and analyzed with a Shimadzu Nexera HPLC system equipped with an RF-20Axs fluorescence detector and a reverse-phase column (Phenomenex Hyperclone, 5 μm ODS, 120 Å, 250×4.60 mm). The separation on HPLC was achieved as follows: Solvent A consisted of 1% (v/v) tetrahydrofuran (THF), 0.5% (v/v) phosphoric acid, and 0.2% (v/v) n-butylamine in water; solvent B was acetonitrile. The flow rate was adjusted to 1 mL/min and the excitation/emission wavelengths were set at 360/425 nm. Solvent B was started at a relative concentration of 2.5% and held for 7 min, and a linear gradient of 2.5−18% of solvent B was applied from 7 to 25 min. Then solvent B was increased to 95% in 2 min and held for 5 min. Solvent B was then decreased to 2.5% in 1 min and the column was equilibrated with the same conditions for 7 min.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of 1-(2-aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazole-3-ium tetrafluoroborate [MIEA][BF4]

A novel amino-functionalized ionic liquid [1-(2-aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazole-3-ium][BF4], abbreviated [MIEA][BF4], was synthesized from commercially available N-methylimidazolium and tert-butyl N-(2-bromoethyl)carbamate, followed by recrystallization and using KBF4 for exchanging bromide with tetrafluorobromide. The overall total yield of this two-step synthesis was calculated to be 49%. The structure and purity of [MIEA][BF4] was verified by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. NMR signals were annotated as following:

1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ (ppm) 8.61 (s, 1H, H-2), 7.38 (s, 2H, H-4, H-5), 4.44–4.40 (t, J=8 Hz, 2H, H-6), 3.86 (s, 3H, H-9), 3.60–3.55 (t, J=12, 8 Hz 2H, H-7). 13C NMR (101 MHz, D2O): δ (ppm) 135.02 (C-2), 123.02 (C-4), 119.48 (C-5), 66.14 (C-6), 40.52 (C-7), 35.61 (C-9) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Detection of MIEA+-labeled standard sugars with LC-MS and MALDI-ToF MS

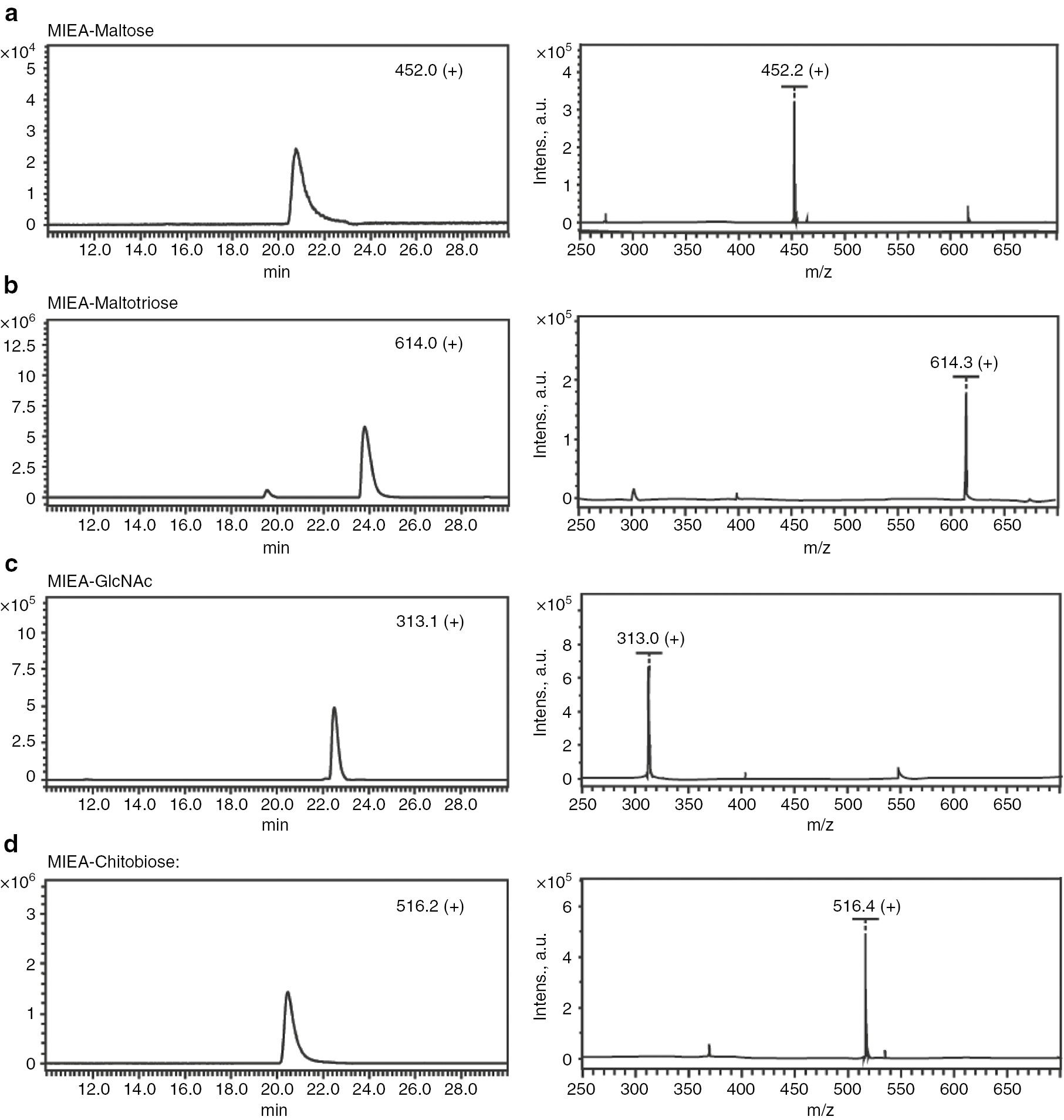

To explore the application of [MIEA][BF4] in the derivatization of saccharides, maltose was chosen as a test substrate. The labeling reaction was taken in dimethyl sulfoxide/acetic acid solution with sodium cyanoborohydride and monitored with MALDI-ToF MS. After incubation of the mixture at 70°C for 4 h, almost no underivatized maltose could be detected, and a new mass peak with an m/z value of 452.2 was observed, which matches the calculated molecular mass of MIEA+-maltose (452.2 Da for [M]+, Fig. 1a). The product was further verified by detection of a hexose fragment (162.2 Da) by MALDI-ToF MS/MS (Supplementary Fig. S2). Given these obtained mass values, we presume that the derivatization of maltose by MIEA+ follows the expected reaction mechanism referred as reductive amination [33]: the free aldehyde at the reducing end of maltose is converted to an imine by the reaction with the amine group of MIEA+ (Scheme 1b). The same amination reaction was also observed in the derivation of maltotriose as judged by MALDI-ToF MS and LC-ESI-MS analysis. An m/z value about 614.0 was detected fitting the calculated mass value of MIEA+-maltotriose (in [M]+-form).

MALDI-ToF-MS and LC-ESI-MS spectra of MIEA+ labeled standards maltose (a), maltotriose (b), GlcNAc (c), and chitibiose (d).

![Scheme 1: The synthetic route of [MIEA][BF4] and derivation of glycoses and aminoglycosides.](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-0117/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-0117_scheme_001.jpg)

The synthetic route of [MIEA][BF4] and derivation of glycoses and aminoglycosides.

To determine the detection limit of the MIEA+ labeled sugars, MIEA+-maltose was purified with HILIC chromatography and the concentration determined using quantitative monosaccharide analysis. Various concentrations of MIEA+-maltose (1–150 μM) were then prepared and subsequently analyzed by LC-ESI-MS. The obtained peak areas correlated in a linear manner with the expected concentrations in the range of 10 pmol to 150 pmol. The limit of detection (LOD, S/N=3) for MIEA+ labeled maltose was determined to be 6.8 pmol, and the limit of quantification (LOQ, S/N=10) was determined to be 28.0 pmol.

N-Acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and chitobiose (GlcNAc2), which share the same configuration of the hemiacetal moiety with N-glycans, were further selected to confirm the versatility of the MIEA+ derivatization agent, and mass spectrometric analyses showed the corresponding masses for GlcNAc (313.0 [M]+) and chitobiose (516.4 [M]+) of the reaction products (Fig. 1c and d). According to the MS spectra, the MIEA+ labeled sugars could be detected by both MALDI-ToF-MS and LC-ESI-MS analyses.

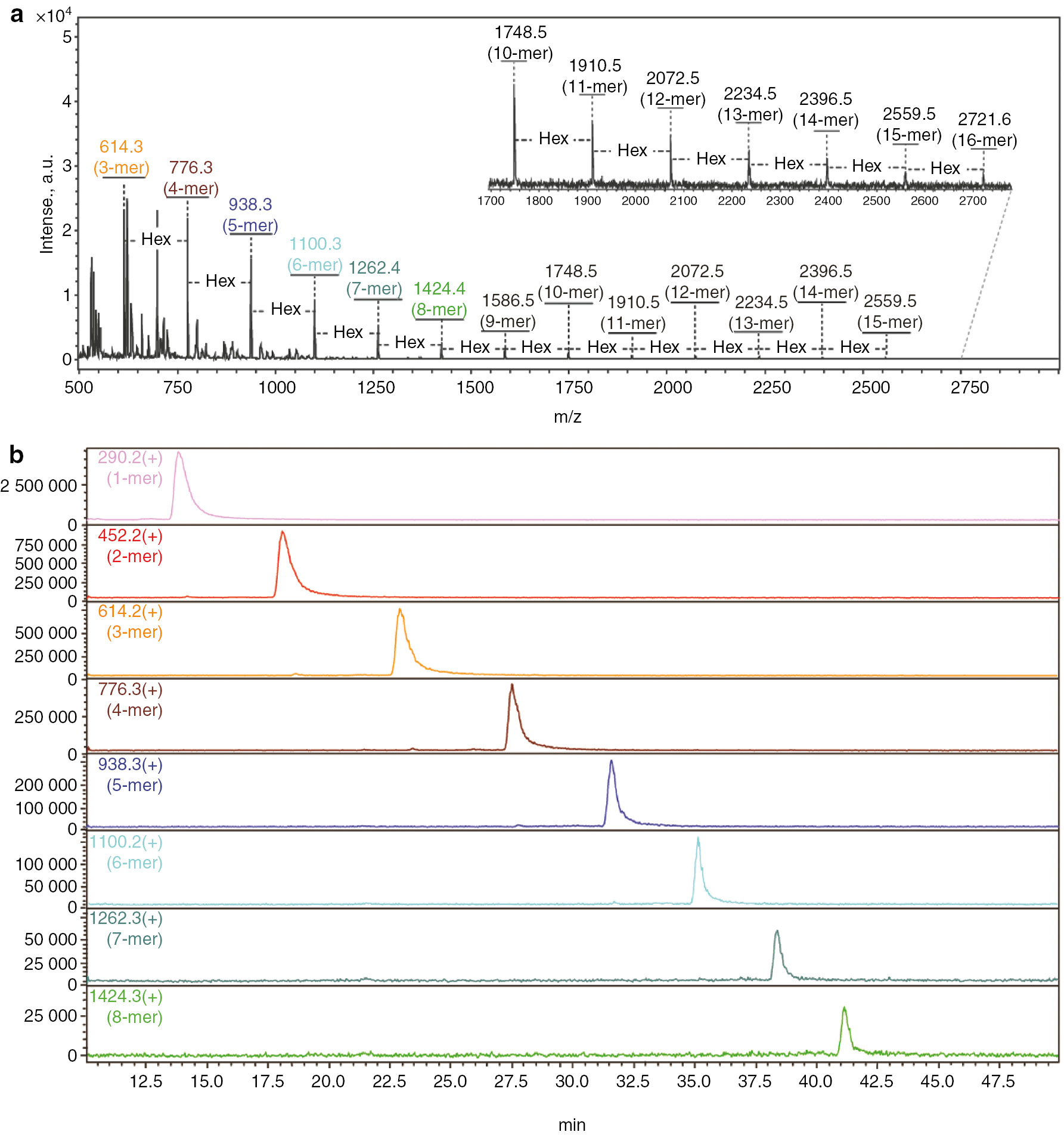

Detection of MIEA+-labeled dextran with LC-MS and MALDI-ToF MS

Dextran oligomers (α1,6-linked D-glucopyranosides consisting of 2-20 monomer units) are routinely applied as a standard for deduction of N-glycan structure based on the calculated standard glucose value (GU value) [34], [35], [36]. After derivatization of dextran oligomers with MIEA+, the reaction mixture was analyzed by both MALDI-ToF-MS and LC-ESI-MS. The observed m/z values of [M]+ ions (614.3, 776.3, 938.3, 1100.3, 1262.4, 1424.4, 1586.5, 1748.5, 1910.5, 2072.5, 2234.5, 2396.5, 2559.5, 2721.6) correlated well with the theoretical mass values for MIEA+-labeled dextran oligomers (Fig. 2a). A total of 14 different MIEA+-labeled oligomers ranging from 3 to 16 glucose units were detected. As expected, the sequential addition of a hexose residue (ΔHEX=162.0 Da) was observed between each observed mass peak. The same sample was also analyzed by LC-ESI-MS. After separation of the analytes by HILIC chromatography, the MIEA+-dextran analytes with a degree of polymerization between 1 and 8 were detected in the elution time range between 12.5 and 42.5 min (Fig. 2b).

MALDI-ToF-MS and LC-ESI-MS spectra of MIEA+-labeled dextran oligomers. (a) MALDI-ToF-MS spectrum; (b) LC-ESI-MS spectrum.

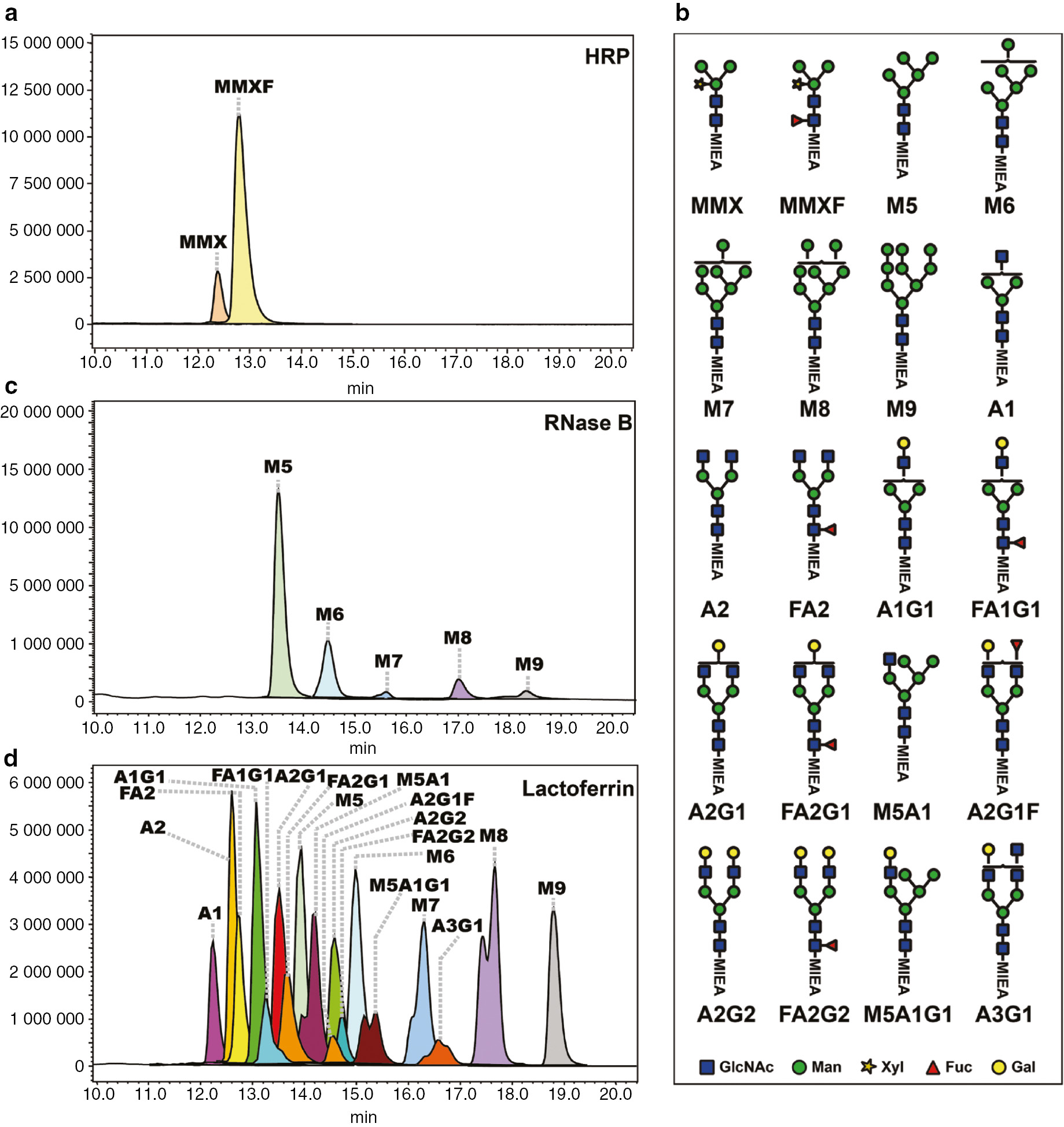

Detection of MIEA+-labeled N-glycans from glycoprotein standards

Three different standard glycoproteins including horseradish peroxidase (HRP), RNase B and bovine lactoferrin were chosen as starting material for N-glycan preparation. These glycoproteins bear a range of glycoforms, including high-mannose-, complex- and hybrid-type N-glycans. The high proportion of glycosylation of HRP (>20% of the glycoprotein mass are N-glycans) makes it an ideal source to verify the methodology of MIEA+ labeling of N-glycans. According to previous reports [37], [38], HRP contains mainly two different N-glycan structures, the biantennary complex-type bearing both core α1,3-fucosylation and β1,2-xylosylation (MMXF, ~80%), and a glycoform without core fucosylation (MMX, ~13%). The LC-ESI-MS analysis of the MIEA+-labeled HRP N-glycans showed that MMXF was eluted at 12.9 min as the main peak with an observed m/z value of 1280.4 ([M]+, Fig. 3a). Higher charged ions of MIEA+-MMXF (640.7 [M+H]2+, 651.7 [M+Na]2+ and 659.7 [M+K]2+) were also detected at the same retention time. The MIEA+-MMX derivative was detected at a retention time of 12.4 min with the expected m/z values of 1134.3 [M]+, 567.5 [M+H]2+, 578.5 [M+Na]2+ and 586.5 [M+K]2+.

Extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) profile for MIEA+-labeled N-glycans from HRP, RNase B and lactoferrin. (a) EIC profile of MIEA+-labeled N-glycans from HRP; (b) a summary of all annotated MIEA+-labeled N-glycan structures; (c) EIC profile of MIEA+-labeled N-glycans from RNase B; (d) EIC profile of MIEA+-labeled N-glycans from lactoferrin.

RNase B is a glycoprotein bearing only high-mannose type N-glycans and consists mainly of M5, M6, M7, M8 and M9 glycoforms (Fig. 3b) [39], [40]. The N-glycans from RNase B were labeled with MIEA+, separated on HILIC-UPLC and detected with ESI-MS using the same procedures as HRP. As shown in Fig. 3c, all of the five glycoforms of RNase B of both mono-charged ions and di-charged ions were observed, including MIEA+-M5 (1326.3 [M]+, 663.7 [M+H]2+ and 674.7 [M+Na]2+), MIEA+-M6 (1488.3 [M]+, 744.8 [M+H]2+, 755.7 [M+Na]2+ and 763.8 [M+K]2+), MIEA+-M7 (1650.4 [M]+ and 825.8 [M+H]2+), MIEA+-M8 (1812.4 [M]+ and 906.9 [M+H]2+), and MIEA+-M9 (1975.5 [M]+ and 988.1 [M+H]2+).

Bovine lactoferrin was described to bear up to 42 different glycoforms at five potential N-glycosylation sites [41]. After labeling by MIEA+, 18 distinct MIEA+ labeled glycoforms were detected and separated by LC-ESI-MS (Fig. 3b and d, Supplementary Table 1). It is notable that also the isomeric separation of MIEA+ labeled N-glycans was observed. For example, two peaks exhibited the same m/z value of 1716.5, which can be assigned as an MIEA+-labeled, monofucosylated, monogalactosylated, biantennary complex N-glycan (theoretical m/z=1716.7 [M]+). Other examples for isomeric separations were observed for M5A1, M5A1G1, M7, A3G1 and M8 N-glycans.

Conclusion

In this report, we describe the synthesis and application of a new ionizing label for the derivatization of carbohydrates. The synthesis can be performed in only two steps, and the simple purification procedure by recrystallization and filtration allows the isolation of the pure compound in gram scale. The derivatization of carbohydrates by MIEA+ was demonstrated using various monosaccharides, disaccharides, and oligosaccharide standards. The analysis of the reaction products by MALDI-ToF-MS or LC-ESI-MS does not require prior purification of the analytes and showed high sensitivity. MIEA+ was furthermore successfully applied for the derivatization and subsequent analysis of N-glycans from various glycoproteins. The separation of MIEA+-dextran oligomers and MIEA+ derivatized N-glycans with HILIC-UPLC was comparable to that described for other N-glycan derivatization agents such as 2-aminobenzamide or 2-aminopyridine. It is worth noting that some isobaric N-glycans were also separated by this method, which could not easily be achieved by other standard N-glycan analysis procedure using 2-aminobenzamide labeled N-glycans.

Article note

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at the 29th International Carbohydrate Symposium (ICS-29), held in the University of Lisbon, Portugal, 14–19 July 2018.

Funding source: Central Universities

Award Identifier / Grant number: KYZ201824

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 31401648

Award Identifier / Grant number: 31471703

Award Identifier / Grant number: 31671854

Award Identifier / Grant number: 31871793

Award Identifier / Grant number: 31871754

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: BK20140719

Funding source: 100 Foreign Talents Plan

Award Identifier / Grant number: JSB2014012

Funding statement: This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant numbers KYZ201824 to T. W.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 31401648 to T. W. and L.L., and 31471703, 31671854, 31871793 and 31871754 to J.V. and L.L.), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (grant number BK20140719 to T. W.), and the 100 Foreign Talents Plan (grant number JSB2014012 to J.V.).

Abbreviations

- 2AA

2-aminobenzoic acid

- 2AB

2-aminobenzamide

- LC-ESI-TOF

Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry

- GlcNAc

N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide

- GU

Glucose units

- HILIC

Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- LOD

Limit of detection

- LOQ

Limit of quantification

- MALDI-ToF-MS

Matrix assisted laser ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry

- MIEA+

1-(2-Aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazole-3-ium

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- PNGase

Peptide-N4-(N-acetyl-β-gluccosaminyl)asparagine amidase

- RNase B

Ribonuclease B

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- TFA

Trifluoroacetic acid

- UPLC

Ultra high-performance liquid chromatography

References

[1] T. Mari, O. Kazuaki, F. K. Hagen, D. David, Z. Alexander, S. Patrick, U. H. Andrian, Von, L. Klaus, L. Dzung, L. A. Tabak. Mol. Cell. Biol.27, 8783 (2007).10.1128/MCB.01204-07Search in Google Scholar

[2] J. W. Dennis, M. Granovsky, C. E. Warren. BioEssays21, 412 (1999).10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199905)21:5<412::AID-BIES8>3.0.CO;2-5Search in Google Scholar

[3] R. Pierluigi, Z. Andrea, R. Barbara, C. Leonardo, P. Daniela, R. Aldo, D. P. Fabrizio, M. Myeong Hee, M. Byung Ryul. Anal. Chem.77, 47 (2005).10.1021/ac048898oSearch in Google Scholar

[4] A. Harazono, N. Kawasaki, S. Itoh, N. Hashii, Y. Matsuishi-Nakajima, T. Kawanishi, T. Yamaguchi. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci.869, 20 (2008).10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.05.006Search in Google Scholar

[5] M. J. Huddleston, M. F. Bean, S. A. Carr. Anal. Chem.65, 877 (1993).10.1021/ac00055a009Search in Google Scholar

[6] K. Dominik, L. Iván, C. Dorina, G. M. Guebitz, R. David, K. Wolfgang. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.47, 9337 (2010).Search in Google Scholar

[7] C. J. Wang, J. B. Yuan, X. H. Li, Z. F. Wang, L. J. Huang. Analyst138, 5344 (2013).10.1039/c3an00931aSearch in Google Scholar

[8] H. Hahne, P. Neubert, K. Kuhn, C. Etienne, R. Bomgarden, J. C. Rogers, B. Kuster. Anal. Chem.84, 3716 (2012).10.1021/ac300197cSearch in Google Scholar

[9] M. Pabst, D. Kolarich, G. Pöltl, T. Dalik, G. Lubec, A. Hofinger, F. Altmann. Anal. Biochem.384, 263 (2009).10.1016/j.ab.2008.09.041Search in Google Scholar

[10] R. P. Kozak, C. B. Tortosa, D. L. Fernandes, D. I. R. Spencer. Anal. Biochem.486, 38 (2015).10.1016/j.ab.2015.06.006Search in Google Scholar

[11] M.-Z. Zhao, Y.-W. Zhang, F. Yuan, Y. Deng, J.-X. Liu, Y.-L. Zhou, X.-X. Zhang. Talanta144, 992 (2015).10.1016/j.talanta.2015.07.045Search in Google Scholar

[12] M. A. Lauber, Y. Ying-Qing, D. W. Brousmiche, H. Zhengmao, S. M. Koza, M. Paula, G. Ellen, C. H. Taron, K. J. Fountain. Anal. Chem.87, 5401 (2015).10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00758Search in Google Scholar

[13] S. Zhou, L. Veillon, X. Dong, Y. Huang, Y. Mechref. Analyst142, 4446 (2017).10.1039/C7AN01262DSearch in Google Scholar

[14] M. J. Earle, K. R. Seddon. Pure Appl. Chem.72, 1391 (2009).10.1351/pac200072071391Search in Google Scholar

[15] A.-T. Tran, R. Burden, D. T. Racys, M. Carmen Galan. Chem. Commun.47, 4526 (2011).10.1039/c0cc05580hSearch in Google Scholar

[16] S. G. Lee, J. H. Park. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem.194, 49 (2003).10.1016/S1381-1169(02)00532-0Search in Google Scholar

[17] P. Karthikeyan, P. N. Muskawar, S. A. Aswar, P. R. Bhagat, S. S. Kumar, P. S. Satvat, A. N. B. Nair. Arab. J. Chem.9, S1679 (2012).10.1016/j.arabjc.2012.04.032Search in Google Scholar

[18] J. Gao, J. Q. Wang, Q. W. Song, L. N. He. Green Chem.13, 1182 (2011).10.1039/c1gc15056aSearch in Google Scholar

[19] Y. Kuroiwa, M. Sekine, S. Tomono, D. Takahashi, K. Toshima. Tetrahedron Lett.51, 6294 (2010).10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.09.108Search in Google Scholar

[20] A. Tholey, E. Heinzle. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.386, 24 (2006).10.1007/s00216-006-0600-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] J. J. Dertinger, A. V. Walker. Surf. Interface Anal.46, 15 (2015).10.1002/sia.5622Search in Google Scholar

[22] J. J. Dertinger, A. V. Walker. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom.24, 348 (2013).10.1007/s13361-012-0568-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] D. W. Armstrong, L. K. Zhang, L. He, M. L. Gross. Anal. Chem.73, 3679 (2001).10.1021/ac010259fSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] C. K. Yerneni, V. Pathak, A. K. Pathak. J. Org. Chem.74, 6307 (2009).10.1021/jo901169uSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] M. C. Galan, A. T. Tran, C. Bernard. Chem. Commun.46, 8968 (2010).10.1039/c0cc04224bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] M. L. A. De Leoz, S. C. Gaerlan, J. S. Strum, L. M. Dimapasoc, M. Mirmiran, D. J. Tancredi, J. T. Smilowitz, K. M. Kalanetra, D. A. Mills, J. B. German, C. B. Lebrilla, M. A. Underwood. J. Proteome Res.11, 4662 (2012).10.1021/pr3004979Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] T. Wang, Z. P. Cai, X. Q. Gu, H. Y. Ma, Y. M. Du, K. Huang, J. Voglmeir, L. Liu. Biosci. Rep.34, e00149 (2014).10.1042/BSR20140148Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Y.-M. Du, S.-L. Zheng, L. Liu, J. Voglmeir, G. Yedid. J. Vis. Exp.136, e57979 (2018).Search in Google Scholar

[29] Y. M. Du, T. Xia, X. Q. Gu, T. Wang, H. Y. Ma, J. Voglmeir, L. Liu. J. Agr. Food Chem.63, 10550 (2015).10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03633Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] H. Stepan, E. Staudacher. Anal. Biochem.418, 24 (2011).10.1016/j.ab.2011.07.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Z. P. Cai, A. K. Hagan, M. M. Wang, S. L. Flitsch, L. Liu, J. Voglmeir. Anal. Chem.86, 5179 (2014).10.1021/ac501393aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] T. Wang, X.-C. Hu, Z.-P. Cai, J. Voglmeir, L. Liu. J. Agric. Food Chem.65, 7669 (2017).10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01690Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] R. F. Borch, M. D. Bernstein, H. D. Durst. J. Am. Chem. Soc.93, 2897 (1971).10.1021/ja00741a013Search in Google Scholar

[34] W.-L. Wang, W. Wang, Y.-M. Du, H. Wu, X.-B. Yu, K.-P. Ye, C.-B. Li, Y.-S. Jung, Y.-J. Qian, J. Voglmeir, L. Liu. Food Chem.235, 167 (2017).10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.05.026Search in Google Scholar

[35] Z. P. Cai, W. L. Wang, L. Conway, K. Huang, N. A. Faisal, L. Liu, J. Voglmeir. Pure Appl. Chem.89, 921 (2017).10.1515/pac-2016-0914Search in Google Scholar

[36] L. Esther, G. Ricardo Gutiérrez, B. Viviana, G. J. Gerwig, J. P. Kamerling, S. Jordi, J. A. Pascual. Proteomics7, 4278 (2010).Search in Google Scholar

[37] B. Y. Yang, J. S. S. Gray, R. Montgomery. Carbohydr. Res.287, 203 (1996).10.1016/0008-6215(96)00073-0Search in Google Scholar

[38] E. Staudacher, F. Altmann, I. B. H. Wilson, L. März. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1473, 216 (1999).10.1016/S0304-4165(99)00181-6Search in Google Scholar

[39] S. Hua, C. C. Nwosu, J. S. Strum, R. R. Seipert, H. J. An, A. M. Zivkovic, J. B. German, C. B. Lebrilla. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.403, 1291 (2012).10.1007/s00216-011-5109-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] J. Ahn, J. Bones, Y. Q. Yu, P. M. Rudd, M. Gilar. J. Chromatogr. B878, 403 (2010).10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.12.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] S. S. van Leeuwen, R. J. W. Schoemaker, C. J. A. M. Timmer, J. P. Kamerling, L. Dijkhuizen. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1820, 1444 (2012).10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.12.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2019-0117).

© 2019 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- ICS-29: The 29th International Carbohydrate Symposium

- Conference papers

- 1-(2-Aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium tetrafluoroborate: synthesis and application in carbohydrate analysis

- One-pot oligosaccharide synthesis: latent-active method of glycosylations and radical halogenation activation of allyl glycosides

- Nanoparticles for the multivalent presentation of a TnThr mimetic and as tool for solid state NMR coating investigation

- Preface

- Papers from the 1st International Conference on Chemistry for Beauty and Health (Beauty-Torun’2018)

- Conference papers

- In vivo electrical impedance measurement in human skin assessment

- Formulation and characterization of some oil in water cosmetic emulsions based on collagen hydrolysate and vegetable oils mixtures

- Preparation of polylactide scaffolds for cancellous bone regeneration – preliminary investigation and optimization of the process

- Effect of molecular weight of polyvinylpyrrolidone on the skin irritation potential and properties of body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form

- Ortho-substituted azobenzene: shedding light on new benefits

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Efforts to improve Japanese women’s status in STEM fields

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- ICS-29: The 29th International Carbohydrate Symposium

- Conference papers

- 1-(2-Aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium tetrafluoroborate: synthesis and application in carbohydrate analysis

- One-pot oligosaccharide synthesis: latent-active method of glycosylations and radical halogenation activation of allyl glycosides

- Nanoparticles for the multivalent presentation of a TnThr mimetic and as tool for solid state NMR coating investigation

- Preface

- Papers from the 1st International Conference on Chemistry for Beauty and Health (Beauty-Torun’2018)

- Conference papers

- In vivo electrical impedance measurement in human skin assessment

- Formulation and characterization of some oil in water cosmetic emulsions based on collagen hydrolysate and vegetable oils mixtures

- Preparation of polylactide scaffolds for cancellous bone regeneration – preliminary investigation and optimization of the process

- Effect of molecular weight of polyvinylpyrrolidone on the skin irritation potential and properties of body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form

- Ortho-substituted azobenzene: shedding light on new benefits

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Efforts to improve Japanese women’s status in STEM fields