Abstract

Plasmonic radial breathing mode (RBM), featured with radially oscillating charge density, arises from the surface plasmon waves confined in the flat nanoparticles. The zero net dipole moment endows the RBM with an extremely low radiation yet a remarkable intense local field. On the other hand, owing to the dark mode nature, the RBMs routinely escape from the optical measurements, severely preventing their applications in optoelectronics and nanophotonics. Here, we experimentally demonstrate the existence of RBM in a hexagonal Au nanoplate-on-mirror nanocavity using a far-field linear-polarized light source. The polarization-resolved scattering measurements cooperated with the full-wave simulations elucidate that the RBM originates from the standing plasmon waves residing in the Au nanoplate. Further numerical analysis shows the RBM possesses the remarkable capability of local field enhancement over the other dark modes in the same nanocavity. Moreover, the RBM is sensitive to the gap and nanoplate size of the nanocavity, providing a straightforward way to tailor the wavelength of RBM from the visible to near-infrared region. Our approach provides a facile optical path to access to the plasmonic RBMs and may open up a new route to explore the intriguing applications of RBM, including surface-enhanced Raman scattering, enhanced nonlinear effects, nanolasers, biological and chemical sensing.

1 Introduction

Metallic nanoparticles with localized plasmons modes [1, 2] could provide a unique way to squeeze light into nanoscale volume and profoundly enhance the light field near the particles. Generally, these plasmonic modes fall into two categories, i.e., the bright and the dark modes. The bright mode, such as the electric dipole, has a nonzero dipole moment. Therefore, it can be easily excited through optical means and reradiate considerable electromagnetic energy to the far-field. On the contrary, the dark mode [3] exemplified by the electric quadrupole, has a vanishing dipole moment. Consequently, it hardly couples with light, but can store electromagnetic energy more efficiently than the bright mode [4]. The resulting virtues of high local field enhancement and narrow spectral linewidth make the dark mode attractive for a plethora of applications, including surface-enhanced spectroscopy [5, 6], enhanced optical nonlinearity [7], nanolaser [8], biological and chemical sensing [9, 10].

Among the dark modes, the plasmonic radial breathing mode (RBM) is receiving a growing interest [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. The RBM was first discovered in nuclear physics as a giant monopole resonance associated with the periodic compression and decompression of nuclei [16]. Now, the RBM is a ubiquitous phenomenon in the field of molecular [17], [18], [19], solid-state [20, 21] and acoustic physics [22]. In plasmonics, the RBM, featured with radially symmetric surface charge density oscillation, has been demonstrated in a variety of metallic structures such as nanodisks [11, 12, 14], nanosquares [23], nanotriangles [13], nanoapertures [15] and nanoclusters [24]. Due to the dark mode nature, the plasmonic breathing mode is mainly characterized using the electron beam, for instance, the cathodoluminescence [14, 25] and the scanning transmission electron microscopes equipped with the electron energy loss spectroscopy [3, 11, 14, 26]. These approaches provide unambiguous spectral analysis of the RBM with the ability to image the mode profile with unprecedented spatial resolution. However, for practical applications, such as optical sensing and surface-enhanced Raman scattering, it is indispensable to access to the RBM by non-invasive optical means with the ambient operating conditions. Unfortunately, optical probing of the RBM remains scarce, except for one uses a configuration combing the oblique illumination and the retardation effect [12].

Notably, the recently emerging nanoparticle-on-mirror structures [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34] serve as an ideal platform to explore the plasmonic dark modes including the anapole mode [34], the bonding dipole [35] and quadruple modes [32]. These plasmonic structures much resemble the metal–insulator–metal (MIM) waveguides [36], [37], [38], [39]. In this sense, the surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) residing in the waveguide possess a much larger wave-vector than that of a photon in free space, therefore, greatly facilitate the excitation of plasmonic dark modes. Moreover, the MIM configuration affords great flexibility to tailor the optical responses through the structural parameter designing [38, 39]. Here, we report for the first time on the excitation of plasmonic RBM in hexagonal Au nanoplate-on-mirror (NPoM) structure using a linear polarized far-field light source. The combination of experimental data with simulation results and theoretical models reveals that the RBM holds intriguing characters of strong electric field enhancement and highly tunable dispersion. Our results shed light on the physics of plasmonic RBM and pave the way for its applications in optical sensing, surface-enhanced Raman scattering and enhanced optical nonlinearity.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Sample preparation

The hexagonal Au NPoM samples were fabricated using the bottom-up following with the self-assembly techniques [40]. First, a 50 nm Au film was deposited onto a silicon substrate using thermal evaporation at a rate of 2 Å/s. This Au film was transferred onto a SiO2/Si substrate via a template-stripping method [41], yielding an ultrasmooth Au surface with the root-mean-square surface roughness of 0.26 nm. Then, an Al2O3 spacer layer with thickness varying from 1–15 nm was deposited on the Au film using the atomic layer deposition at 90 °C with 1.13 Å/cycle. The thickness of the deposited Al2O3 spacer is linear with the number of reaction cycle, therefore, was well controlled through the cycle numbers. Finally, a diluted Au hexagonal nanoplates solution (Nanoseedz, Inc.) was drop-coated on the Al2O3 spacer layer to form the NPoM geometries.

2.2 Optical measurements

The dark-field scattering spectroscopy was performed using a home-built dark-field confocal microscope [42]. A polarization-controlled white light from a halogen lamp illuminated the sample through a 50× objective (Mitutoyo, NA 0.55) at an incident angle of 70°. The scattering light was collected with an upright 50× objective (Nikon NA 0.4), then was recorded as the dark image by a CCD camera. Meanwhile, after passing through a spatial filter, the scattering signal from the individual hexagonal Au NPoM was delivered to an imaging spectrometer (Andor Shamrock SR-303i) for spectral analysis.

2.3 Numerical simulations

The plasmonic responses of Au hexagonal NPoMs were calculated using the finite element method. The geometrical configurations of the hexagonal Au NPoMs were modeled as their experimental counterparts. Moreover, to match with the experimental samples, the corners and edges of the nanoplates were rounded by an 8 nm curvature. The permittivity of Au was taken from the experimental data of Johnson and Christy [43]. The refractive indices of the Al2O3 layer and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) surfactant polymer were taken as a constant of 1.55. The scattering fields of NPoMs were obtained through a two-step method, where the background field, derived from the plane wave incident on the substrate without the hexagonal Au nanoplate, was used as the excitation with the nanoplate present. To calculate the scattering spectra, the scattered field at each wavelength were collected within a cone of half-angle 23.6°, corresponding to the numerical aperture of the objective. The charge density of the plasmonic mode was derived by calculating the difference of the normal component of the electric field above and below the metal surface according to Gauss’s law.

3 Results and discussion

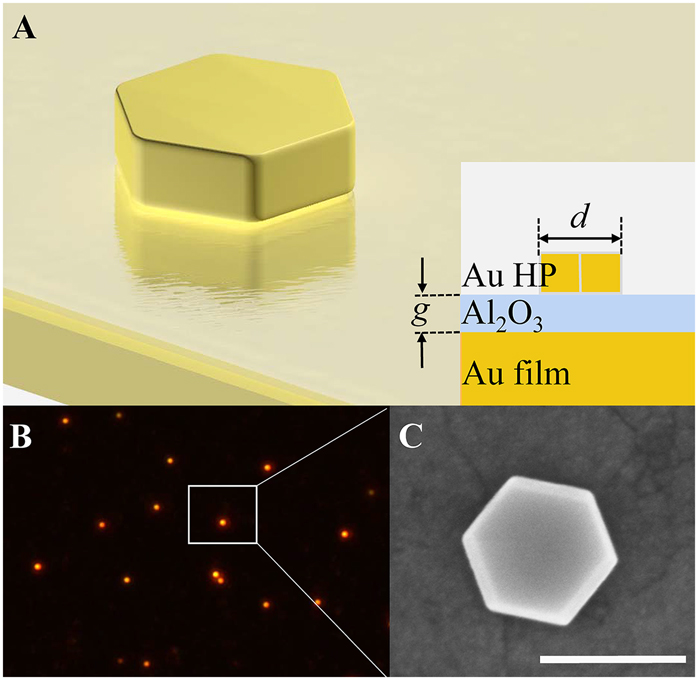

Figure 1A schematically shows the hexagonal Au NPoM sample under consideration, which is composed of a single hexagonal Au nanoplate and an ultrasmooth Au film spaced by an Al2O3 layer with the thickness of g. The hexagonal Au nanoplate is coated with a 2 nm CTAB and has an average thickness of 50 nm (see Supplementary Material, Figure S1). The size of the nanoplate is defined by the distance between two parallel edges d. Figure 1B displays the dark-field image of a representative hexagonal Au NPoM. As can be seen, the separations between hexagonal Au nanoplates are deliberately controlled over 8 μm to ensure the single-particle level scattering measurement. Figure 1C shows the scanning electronic microscope (SEM) image of the hexagonal Au NPoM, which exhibits a nearly perfect hexagonal shape with the particle size determined to be 180 nm.

(A) Schematic of hexagonal Au nanoplate-on-mirror (NPoM) consisting a hexagonal Au nanoplate, an ultrasmooth Au film and an Al2O3 spacer. Inset shows the cross-section diagram of hexagonal Au NPoM. (B) Dark-field image of the hexagonal Au NPoM. The white box indicates a typical hexagonal Au nanoplate measured in our experiment. (C) SEM image of the hexagonal Au NPoM. The scale bar is 200 nm.

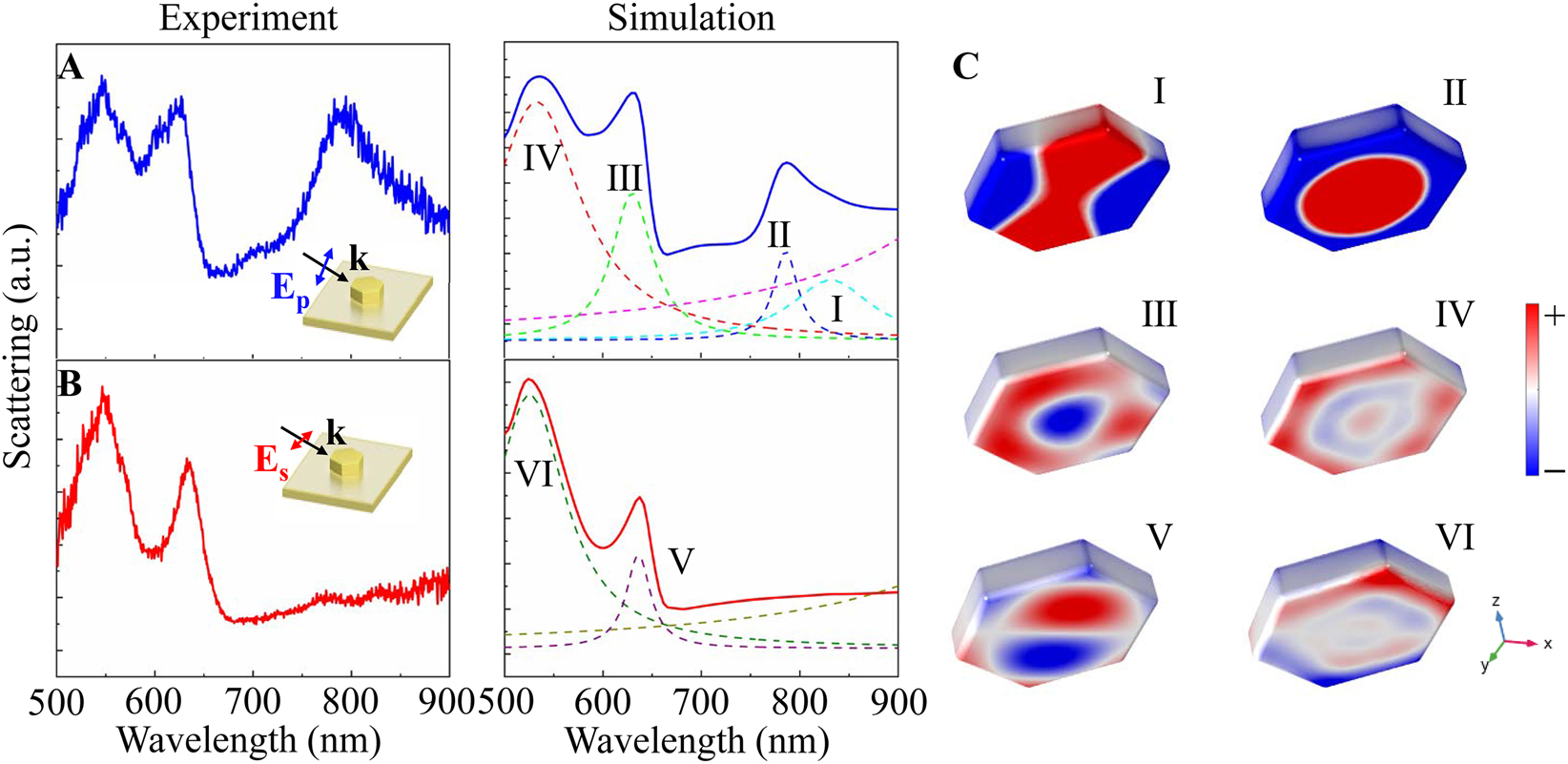

The scattering measurements were carried out on the single hexagonal Au NPoM using a polarization-resolved micro-spectroscopy system. The left panels of Figure 2A and B shows the experimental scattering spectra of a hexagonal Au NPoM (d = 185 nm, g = 5 nm) under the excitation of p- and s-polarized beams, respectively. Due to the strong interaction between the Au nanoplate and the underlying metal film, a wealth of spectral peaks appears compared with the scenario of the bare nanoplate sitting on a silica substrate (see Supplementary Material, Figure S2A). To uncover the origins of these spectral peaks, we calculate the scattering spectra of the hexagonal Au NPoM with a full-wave simulation based on the finite element method (FEM) as shown in the right panels of Figure 2A and B. The excellent agreement between our measured and simulated spectra allows us to decompose the spectra with multiple Lorentzian functions according to the charge density maps of the NPoM. In the following, for briefness, we constraint the analyses on the mode types of the Au nanoplate, though their imaged modes are produced in the Au film at meanwhile. Under the p-polarized illumination, the broad spectral peak at the longer wavelength can be interpreted as the superposition of a quadruple mode (mode I, λ = 832 nm) and a fundamental RBM (mode II, λ = 787 nm), as confirmed by the charge density maps in Figure 2C. As seen, the RBM features a circular charge nodal line and holds considerable charge around the center of the nanoplate. This unique charge distribution is distinguished from conventional plasmonic modes, such as electric dipole mode, for which the charge is localized at the periphery of the structure. Of note is that the Au nanoplate, the Al2O3 spacer together with the ultrasmooth Au film equivalently forms a metal–insulator–metal (MIM) waveguide. In this sense, the SPPs mode of this MIM waveguide can be readily excited by the p-polarized (TM) beam in the present of the subwavelength nanoplate. The in-plane propagating SPPs carry a large wave-vector and considerable phase retardation, making the RBM attainable.

Experimental (left column) and simulated (right column) scattering spectra of hexagonal Au NPoM (d = 185 nm, g = 5 nm) illuminated by (A) p-polarized and (B) s-polarized beams. (C) Charge density distributions of modes I–VI with spectral positions labeled in (A) and (B).

As truncated by the bottom edges of nanoplate, the SPPs are reflected back and forth within the MIM waveguide and eventually escape to free space, rendering the breathing mode visible. In addition, two peaks in the shorter wavelength region are identified as the second- (mode III, λ = 630 nm) and third-order RBMs (mode IV, λ = 533 nm), as the evidence from the number of circular nodal lines in Figure 2C. Obvious distortions are also found in these charge maps due to the more complex phase retardation at the short wavelength. For the s-polarized illumination, two profound peaks are observed and are denoted as the modes V and VI. These two modes can be assigned with mode indices of (1, 1) and (1, 3), according to their charge pattern shown in Figure 2C. Since these two modes are odd parity, they can be excited directly by the s-polarized beam even at normal incidence (see Supplementary Material, Figure S2B). In particular, the absence of a spectral peak at the longer wavelength further confirms the RBM arises from the SPPs of the MIM waveguide.

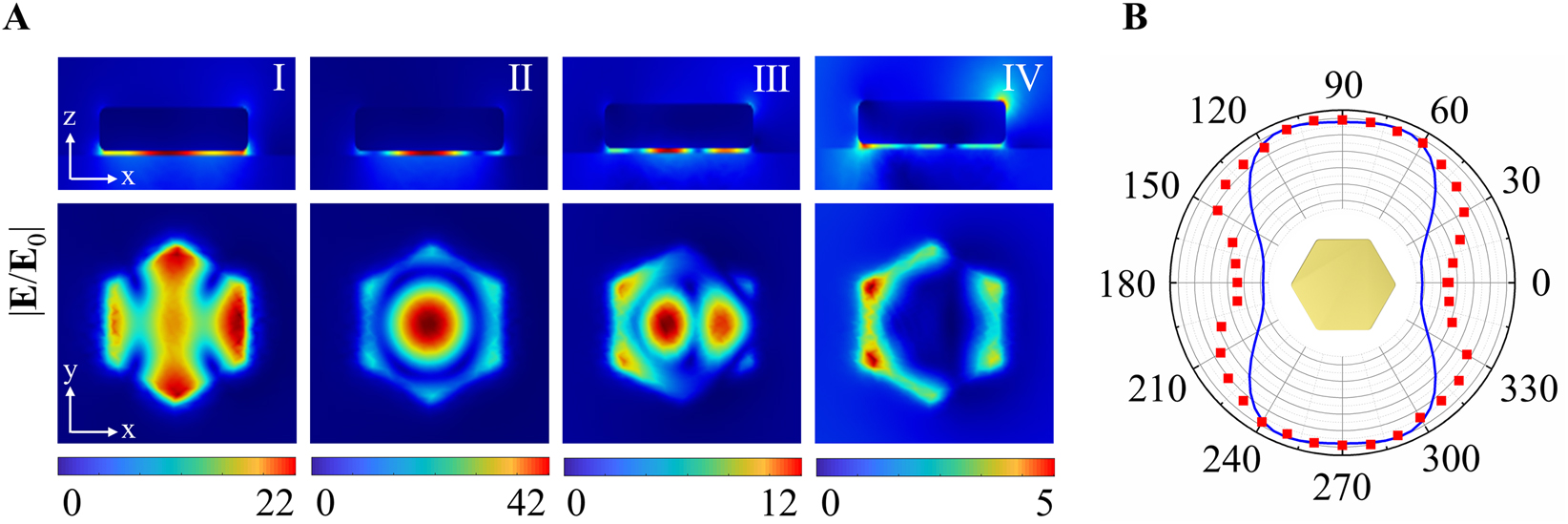

We then turn to examine the near- and far-field properties of the RBM. Figure 3A shows the electric field enhancement (defined as |E|/|E 0|) maps of NPoM when illuminated by the p-polarized beam. It is noted that the electric field distributions of modes I–IV are in concordance with their charge patterns. Particularly, the fundamental RBM concentrates most of the electric field at the center of the nanoplate. More surprisingly, this RBM shows a maximum electric field enhancement over 40, almost 2 times larger than the typical dark mode, i.e., quadruple mode. In Figure 3B, we display the polar plot of scattering intensity for the RBM as a function of the polarization direction. As seen, the polar plot of the polarization distribution displays an anisotropic pattern in contrast to that of bare nanodisk [14]. It is because the charge in the nanoplate bottom induces another RBM but with the opposite distribution in the Au film as shown in Figure S3. Thus, the far field radiation can only be attributed to the charge oscillation on the top surface of the nanoplate as a consequence of the radiation canceling between two out-of-phase RBMs in the gap region. Additionally, the retardation effect of the excitation makes the charge distribution on the top surface of nanoplate distorted to be more like an electric dipole (see Figure S3), rendering a dumbbell-shaped polar diagram. The simulation also verifies this measured polar diagram.

(A) Electric field enhancements of modes I–IV for a hexagonal Au NPoM with d = 185 nm and g = 5 nm. (B) Polar plot of the polarization-dependent scattering intensity of the fundamental radial breathing mode (RBM, mode II). The blue solid line and red dots are derived from the simulation and experiment, respectively.

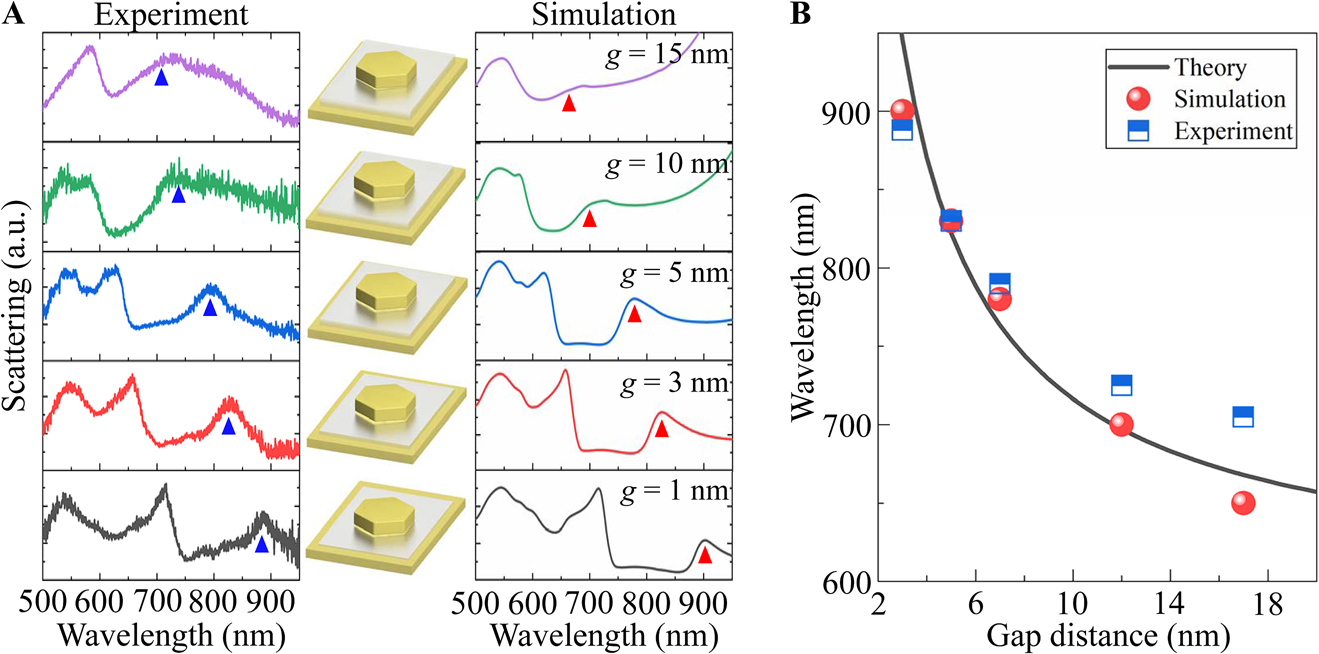

To further understand the nature of the RBM, we fabricate hexagonal Au NPoMs with different gap and nanoplate sizes, and focus our discussion on the variation of the resonance position for the fundamental RBM. From the measured scattering spectra shown in Figure 4A, we observe a blue shift of the RBM when the gap size of the hexagonal Au NPoM (d = 180 nm) is increased from 1 to 15 nm. This variation in experimental spectra is further confirmed by the simulation results in the right column of Figure 4A. Physically, for the RBM, charges with the opposite polarity accumulate at the bottom of Au nanoplate and the top of Au film, as a whole, form a bonding mode (see Supplementary Material, Figure S3). The frequency of this bonding mode can be generally described by

Here, λ

p = 148 nm denotes plasmon wavelength of Au, ε

m = 1 and ε

∞ = 14 represent the permittivity of the dielectric medium and the corresponding background permittivity, respectively. η = C

g/C

np is the capacitance of MIM waveguide

(A) Scattering spectra of hexagonal Au NPoMs (d = 180 nm) of various gap sizes. The left and right columns are the measured and simulated scattering spectra with triangles indicating the dispersion of RBM. The middle column depicts the NPoMs with different gap sizes. (B) Resonance wavelength of RBM as a function of gap size.

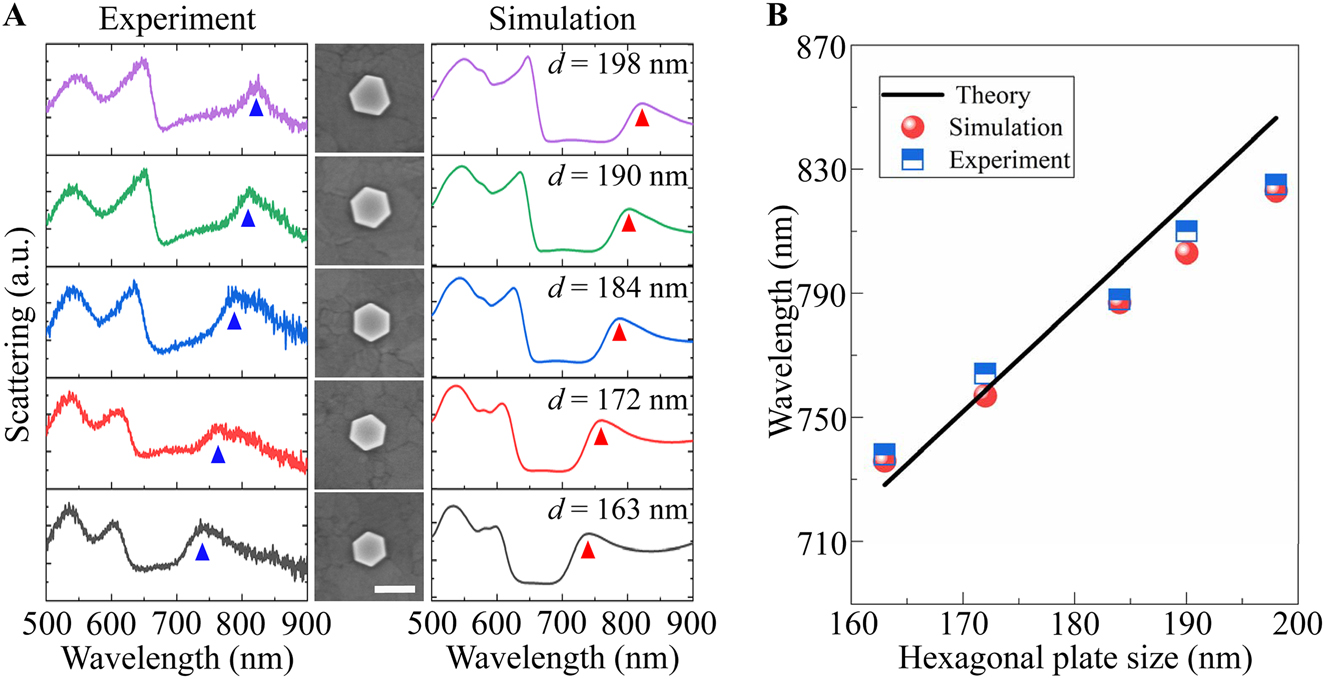

In Figure 5, we inspect the scattering spectra of hexagonal Au NPoM (g = 5 nm) as a dependence of the nanoplate size. Here, the sizes of nanoplates are measured from SEM images shown in the middle column of Figure 5A, which vary from 163 to 198 nm. It is found that the measured spectral peak of the RBM redshifts with increasing the nanoplate size (the left column of Figure 5A), which is also verified by the simulation results (the right column of Figure 5A). As mentioned, the RBM can be viewed as the standing plasmon waves in the nanoplate. Accordingly, we describe the dispersion of the RBM by the Fabry–Pérot condition [49, 50].

where λ, n eff and β are, respectively, the resonant wavelength, the effective index and the phase acquired by the reflection at the nanoplate boundary. For the RBM, a mn is set to be a 01 = 2.4, denoting the 1st root of the zeroth order Bessel function J 0. The effective indices of the RBM for different nanoplate sizes are solved by the dispersion relation in Ref. [40, 49]. Figure 5B summarizes the wavelength of RBM as a function of the nanoplate size. The blue square and red circle dots depict the data retrieved from experimental and simulated spectra, respectively. As seen, the experiment agrees well with the simulation and both can be well described by a linear dispersion relation govern by Eq. (2) (black line in Figure 5B).

(A) Scattering spectra of hexagonal Au NPoM for the nanoplate size changing from 163–198 nm. The left and right columns show the experiment and simulation results. The triangle dots follow the spectral position of the RBM. The middle column displays the SEM images of the hexagonal Au nanoplate, where the scale bar is 200 nm. (B) Resonance wavelength of RBM versus nanoplate size. The blue square dots and red circle dots are for the results extracted from experiment and simulation spectra in (A). The black line represents the dispersion predicted by the Fabry–Pérot condition.

It is worth mentioning that the dark mode nature ensures the plasmonic RBM stores a large quantity of electromagnetic energy near the nanoplate, especially at the center. This is highly favorable to embed the active materials such as quantum dots, molecular dyes and two-dimensional semiconductors in the gap of the nanocavity to boost the absorption, emission and vibrational processes. Besides, the ease of tuning the wavelength of plasmonic RBM makes it facile to resonantly enhance these optical processes, facilitating the implement of high efficient optoelectronics devices including the photovoltaics cell, light emitting diode and nanolaser. On the other hand, as seen from Figure 3A, the RBM possesses a large surface-to-volume ratio of the local field enhancement, leading to a considerable electric field to penetrate in the surrounding media. As a result, the resonance peak of RBM is quite sensitive to the change of surrounding refractive index [51]. This merit working with the narrow spectral linewidth (see Figure 2A) could empower RBM with an excellent sensing performance.

4 Conclusions

In summary, plasmonic RBMs having a vanishing dipole moment are almost unattainable in the optical measurements. We have demonstrated an optical way to probe this dark mode in a plasmonic nanocavity composed of the closely spaced hexagonal Au nanoplate and ultrasmooth Au film. The polarization-resolved scattering measurements corroborated by the full-wave simulations allow us to uncover that the RBM arises from the standing plasmon waves confined by the nanoplate and becomes visible in the far-field due to the scattering by the nanoplate edges. Further, near field analysis shows that the RBM has a surprising ability of the electric field enhancement even beyond the typical dark modes such as quadrupole mode. Moreover, this RBM has a strong dispersion against the gap and nanoplate sizes, providing a readily way to tune its resonance wavelength across from visible to near-infrared region. Our findings provide an elegant way to excite the plasmonic RBM that could remove the obstacles for its applications in the field of nanophotonics.

Funding source: National key R&D Program of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2017YFA0303800

Funding source: Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities

Award Identifier / Grant number: 3102019JC008, D5000210936

Funding source: Shaanxi Provincial Key R&D Program

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021KW-19

Funding source: the Key R&D Program of Guangdong Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2020B010189001, 2019B010931001,2018B030327001

Funding source: the Pearl River Talent Recruitment Program of Guangdong Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2019ZT08C321

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC)

Award Identifier / Grant number: 11634010, 11874050, 91950119

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the SEM measurements by the Analytical and Testing Center of Northwestern Polytechnical University.

-

Author contribution: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by National key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0303800), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (11634010, 11874050, 91950119), Shaanxi Provincial Key R&D Program (2021KW-19), the Key R&D Program of Guangdong Province (2020B010189001, 2019B010931001 and 2018B030327001), the Pearl River Talent Recruitment Program of Guangdong Province (2019ZT08C321), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3102019JC008, D5000210936).

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

[1] J. N. Anker, W. P. Hall, O. Lyandres, N. C. Shah, J. Zhao, and R. P. Van Duyne, “Biosensing with plasmonic nanosensors,” Nat. Mater., vol. 7, pp. 442–453, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2162.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] M. Premaratne and M. I. Stockman, “Theory and technology of SPASERs,” Adv. Opt Photon, vol. 9, pp. 79–128, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1364/aop.9.000079.Search in Google Scholar

[3] M. Chu, V. Myroshnychenko, C. H. Chen, J. Deng, C. Mou, and F. Javier Garcia de Abajo, “Probing bright and dark surface-plasmon modes in Individual and coupled noble metal nanoparticles using an electron beam,” Nano Lett., vol. 9, pp. 399–404, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl803270x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] M. Liu, T. W. Lee, S. K. Gray, P. Guyot-Sionnest, and M. Pelton, “Excitation of dark plasmons in metal nanoparticles by a localized emitter,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 102, p. 107401, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.102.107401.Search in Google Scholar

[5] J. Ye, F. Wen, H. Sobhani, et al.., “Plasmonic nanoclusters: near field properties of the Fano resonance Interrogated with SERS,” Nano Lett., vol. 12, pp. 1660–1667, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl3000453.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] R. P. Zaccaria, F. De Angelis, A. Toma, et al.., “Surface plasmon polariton compression through radially and linearly polarized source,” Opt. Lett., vol. 37, pp. 545–547, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.37.000545.Search in Google Scholar

[7] S. Liu, E. S. P. Leong, G. Li, et al.., “Polarization-Independent multiple Fano resonances in plasmonic nanomers for multimode-matching enhanced multiband second-harmonic generation,” ACS Nano, vol. 10, pp. 1442–1453, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.5b06956.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] T. K. Hakala, H. T. Rekola, A. I. Vakevainen, et al.., “Lasing in dark and bright modes of a finite-sized plasmonic lattice,” Nat. Commun., vol. 8, p. 13687, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13687.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] A. E. Cetin and H. Altug, “Fano resonant ring/disk plasmonic nanocavities on conducting substrates for advanced biosensing,” ACS Nano, vol. 6, pp. 9989–9995, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn303643w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] W. Yang, C. Zhang, S. Sun, J. Jing, Q. Song, and S. Xiao, “Dark plasmonic mode based perfect absorption and refractive index sensing,” Nanoscale, vol. 9, pp. 8907–8912, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7nr02768k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] F. P. Schmidt, H. Ditlbacher, U. Hohenester, A. Hohenau, F. Hofer, and J. R. Krenn, “Dark plasmonic breathing modes in silver nanodisks,” Nano Lett., vol. 12, pp. 5780–5783, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl3030938.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] M. K. Krug, M. Reisecker, A. Hohenau, et al.., “Probing plasmonic breathing modes optically,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 105, p. 171103, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4900615.Search in Google Scholar

[13] A. Campos, A. Arbouet, J. Martin, et al.., “Plasmonic breathing and edge modes in aluminum nanotriangles,” ACS Photonics, vol. 4, pp. 1257–1263, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.7b00204.Search in Google Scholar

[14] F. P. Schmidt, A. Losquin, F. Hofer, A. Hohenau, J. R. Krenn, and M. Kociak, “How dark are radial breathing modes in plasmonic nanodisks?” ACS Photonics, vol. 5, pp. 861–866, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.7b01060.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] F. Xiao, Y. Ren, W. Shang, et al.., “Sub-10 nm particle trapping enabled by a plasmonic dark mode,” Opt. Lett., vol. 43, pp. 3413–3416, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.43.003413.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] J. D. Walecka, “Electron scattering from a quantized liquid drop,” Phys. Rev., vol. 126, pp. 653–662, 1962. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrev.126.653.Search in Google Scholar

[17] F. Xiao, W. Shang, W. Zhu, et al.., “Cylindrical vector beam-excited frequency-tunable second harmonic generation in a plasmonic octamer,” Photon. Res., vol. 6, pp. 157–161, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/prj.6.000157.Search in Google Scholar

[18] S. Jaeger, A. M. Kern, M. Hentschel, et al.., “Au nanotip as luminescent near-field probe,” Nano Lett., vol. 13, pp. 3566–3570, 2013.10.1021/nl401173gSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] F. Xiao, G. Wang, W. Shang, et al.., “Radial breathing modes coupling in plasmonic molecules,” Opt. Express, vol. 27, pp. 5116–5124, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.27.005116.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] M. S. Dresselhaus, G. Dresselhaus, R. Saito, and A. Jorio, “Raman spectroscopy of carbon nanotubes,” Phys. Rep., vol. 409, pp. 47–99, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2004.10.006.Search in Google Scholar

[21] H. Lesnard, N. Lorente, and M. L. Bocquet, “Theoretical study of benzene and pyridine STM-induced reactions on copper surfaces,” J. Phys. Condens. Matter, vol. 20, p. 224012, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/20/22/224012.Search in Google Scholar

[22] D. G. Offin, P. R. Birkin, and T. G. Leighton, “Electrodeposition of copper in the presence of an acoustically excited gas bubble,” Electrochem. Commun., vol. 9, pp. 1062–1068, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2006.12.025.Search in Google Scholar

[23] E. P. Bellido, A. Manjavacas, Y. Zhang, Y. Cao, P. Nordlander, and G. A. Botton, “Electron energy-loss spectroscopy of multipolar edge and cavity modes in silver nanosquares,” ACS Photonics, vol. 3, pp. 428–433, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.5b00594.Search in Google Scholar

[24] B. Lan and D. Sun, “Breathing mode of nanoclusters: definition and comparison to a continuous medium model,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 103, p. 134108, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.103.134108.Search in Google Scholar

[25] F. P. Schmidt, A. Losquin, M. Horak, U. Hohenester, M. Stoger-Pollach, and J. R. Krenn, “Fundamental limit of plasmonic cathodoluminescence,” Nano Lett., vol. 21, pp. 590–596, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c04084.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] J. Nelayah, M. Kociak, O. Stephan, et al.., “Two-dimensional quasistatic stationary short range surface plasmons in flat nanoprisms,” Nano Lett., vol. 10, pp. 902–907, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl903653x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] C. Ciraci, R. T. Hill, J. J. Mock, et al.., “Probing the ultimate limits of plasmonic enhancement,” Science, vol. 337, pp. 1072–1074, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1224823.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] G. M. Akselrod, C. Argyropoulos, T. B. Hoang, et al.., “Probing the mechanisms of large Purcell enhancement in plasmonic nanoantennas,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 8, pp. 835–840, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2014.228.Search in Google Scholar

[29] H. Harutyunyan, A. B. Martinson, D. Rosenmann, et al.., “Anomalous ultrafast dynamics of hot plasmonic electrons in nanostructures with hot spots,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 10, pp. 770–774, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.165.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] G. Li, Y. Zhang, J. Jiang, Y. Luo, and D. Lei, “Metal-substrate-mediated plasmon hybridization in a nanoparticle dimer for photoluminescence line-width shrinking and Intensity enhancement,” ACS Nano, vol. 11, pp. 3067–3080, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b00048.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] J. Shi, Y. Li, M. Kang, et al.., “Efficient second harmonic generation in a hybrid plasmonic waveguide by mode interactions,” Nano Lett., vol. 19, pp. 3838–3845, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] S. Cao, L. Hou, Q. Wang, et al.., “Augmenting photoluminescence of monolayer MoS2 using high order modes in a metal dimer-on-film nanocavity,” Photon. Res., vol. 9, pp. 501–506, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1364/prj.414613.Search in Google Scholar

[33] M. E. Kleemann, R. Chikkaraddy, E. M. Alexeev, et al.., “Strong-coupling of WSe2 in ultra-compact plasmonic nanocavities at room temperature,” Nat. Commun., vol. 8, p. 1296, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01398-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] X. Cui, Y. Lai, R. Ai, et al.., “Anapole states and toroidal resonances realized in simple gold nanoplate-on-mirror structures,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 8, p. 2001173, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202001173.Search in Google Scholar

[35] G. Li, Y. Zhang, and D. Lei, “Hybrid plasmonic gap modes in metal film-coupled dimers and their physical origins revealed by polarization resolved dark field spectroscopy,” Nanoscale, vol. 8, pp. 7119–7126, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5nr09260d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] J. B. Lassiter, F. McGuire, J. J. Mock, et al.., “Plasmonic waveguide modes of film-coupled metallic nanocubes,” Nano Lett., vol. 13, pp. 5866–5872, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl402660s.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] J. J. Baumberg, J. Aizpurua, M. H. Mikkelsen, and D. R. Smith, “Extreme nanophotonics from ultrathin metallic gaps,” Nat. Mater., vol. 18, pp. 668–678, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-019-0290-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] A. Dmitriev, T. Pakizeh, M. Kall, and D. S. Sutherland, “Gold-silica-gold nanosandwiches: tunable bimodal plasmonic resonators,” Small, vol. 3, pp. 294–299, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.200600409.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] R. Ogier, L. Shao, M. Svedendahl, and M. Kall, “Continuous-gradient plasmonic nanostructures fabricated by evaporation on a partially exposed rotating substrate,” Adv. Mater., vol. 28, pp. 4658–4664, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201600112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] A. Moreau, C. Ciraci, J. J. Mock, et al.., “Controlled-reflectance surfaces with film-coupled colloidal nanoantennas,” Nature, vol. 492, pp. 86–89, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11615.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] P. Nagpal, N. C. Lindquist, S. Oh, and D. J. Norris, “Ultrasmooth patterned metals for plasmonics and metamaterials,” Science, vol. 325, pp. 594–597, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1174655.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] F. Xiao, G. Wang, X. Gan, et al.., “Selective excitation of a three-dimensionally oriented single plasmonic dipole,” Photon. Res., vol. 7, pp. 693–698, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1364/prj.7.000693.Search in Google Scholar

[43] P. B. Johnson and R. W. Christy, “Optical constants of the noble metals,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 6, pp. 4370–4379, 1972. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.6.4370.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Y. S. Joe, A. M. Satanin, and C. S. Kim, “Classical analogy of Fano resonances,” Phys. Scripta, vol. 74, pp. 259–266, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-8949/74/2/020.Search in Google Scholar

[45] N. Engheta, A. Salandrino, and A. Alu, “Circuit elements at optical frequencies: nanoinductors, nanocapacitors, and nanoresistors,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 95, 2005, Art no. 095504. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.095504.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] F. Benz, B. de Nijs, C. Tserkezis, et al.., “Generalized circuit model for coupled plasmonic systems,” Opt. Express, vol. 23, pp. 33255–33269, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.23.033255.Search in Google Scholar

[47] C. Huang, X. Yin, H. Huang, and Y. Zhu, “Study of plasmon resonance in a gold nanorod with an LC circuit model,” Opt. Express, vol. 17, pp. 6407–6413, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.17.006407.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] M. Premaratne and G. P. Agrawal, Theoretical Foundations of Nanoscale Quantum Devices, Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 2021.10.1017/9781108634472Search in Google Scholar

[49] S. I. Bozhevolnyi and T. Sondergaard, “General properties of slow-plasmon resonant nanostructures: nano-antennas and resonators,” Opt. Express, vol. 15, pp. 10869–10877, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.15.010869.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] C. Tserkezis, R. Esteban, D. O. Sigle, et al.., “Hybridization of plasmonic antenna and cavity modes: extreme optics of nanoparticle-on-mirror nanogaps,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 92, 2015, Art no. 053811. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.92.053811.Search in Google Scholar

[51] N. Verellen, P. Van Dorpe, C. Huang, et al.., “Plasmon line shaping using nanocrosses for high sensitivity localized surface plasmon resonance sensing,” Nano Lett., vol. 11, pp. 391–397, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl102991v.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0506).

© 2021 Qifa Wang et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- A review of terahertz phase modulation from free space to guided wave integrated devices

- Intelligent on-demand design of phononic metamaterials

- Light activation of 3D-printed structures: from millimeter to sub-micrometer scale

- Research Articles

- Unveiling radial breathing mode in a particle-on-mirror plasmonic nanocavity

- Controlling asymmetric transmission phase in planar chiral metasurfaces

- Rayleigh anomaly-enabled mode hybridization in gold nanohole arrays by scalable colloidal lithography for highly-sensitive biosensing

- Enhanced terahertz detection of multigate graphene nanostructures

- The anisotropic broadband surface plasmon polariton and hot carrier properties of borophene monolayer

- Probing higher order optical modes in all-dielectric nanodisk, -square, and -triangle by aperture type scanning near-field optical microscopy

- Cascaded microsphere-coupled surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (CMS-SERS) for ultrasensitive trace-detection

- Morphology adjustable microlens array fabricated by single spatially modulated femtosecond pulse

- Design framework for polarization-insensitive multifunctional achromatic metalenses

- Electro-optically modulated lossy-mode resonance

- Double Rabi splitting in methylene blue dye-Ag nanocavity

- Broadband high-efficiency near-infrared graphene phase modulators enabled by metal–nanoribbon integrated hybrid plasmonic waveguides

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- A review of terahertz phase modulation from free space to guided wave integrated devices

- Intelligent on-demand design of phononic metamaterials

- Light activation of 3D-printed structures: from millimeter to sub-micrometer scale

- Research Articles

- Unveiling radial breathing mode in a particle-on-mirror plasmonic nanocavity

- Controlling asymmetric transmission phase in planar chiral metasurfaces

- Rayleigh anomaly-enabled mode hybridization in gold nanohole arrays by scalable colloidal lithography for highly-sensitive biosensing

- Enhanced terahertz detection of multigate graphene nanostructures

- The anisotropic broadband surface plasmon polariton and hot carrier properties of borophene monolayer

- Probing higher order optical modes in all-dielectric nanodisk, -square, and -triangle by aperture type scanning near-field optical microscopy

- Cascaded microsphere-coupled surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (CMS-SERS) for ultrasensitive trace-detection

- Morphology adjustable microlens array fabricated by single spatially modulated femtosecond pulse

- Design framework for polarization-insensitive multifunctional achromatic metalenses

- Electro-optically modulated lossy-mode resonance

- Double Rabi splitting in methylene blue dye-Ag nanocavity

- Broadband high-efficiency near-infrared graphene phase modulators enabled by metal–nanoribbon integrated hybrid plasmonic waveguides