Abstract

In this paper, we investigate a type of non-canonical question that is not information-seeking, but rather expresses the speaker’s surprise and/or disapproval with respect to the event denoted by the propositional part of the question. Our work is empirically based on claims that have been put forward in the syntactic literature, and our study aims at empirically assessing those theoretical claims about the illocutionary status of surprise-disapproval questions by exploring their pragmatics.

1 Introduction

In this paper, we investigate a type of non-canonical question that is not information-seeking, but rather expresses the speaker’s surprise and/or disapproval with respect to the event denoted by the propositional part of the question. In the theoretical literature, this question type has first been investigated in more detail and from a cross-linguistic perspective by Munaro and Obenauer (1999), who illustrate the general characteristics of structures that both feature interrogative syntax and express a surprise-disapproval interpretation by examples like the following:

| Cossa | zìghe-tu?! | [Pagotto; a sub-dialect of Bellunese] |

| what | shout-CL | |

| ‘Why are you shouting?!’ | ||

| (Munaro and Obenauer 1999: 191) | ||

| Was | lacht | der | denn | so | blöd?! | [German] |

| what | laughs | he | PART | so | stupidly | |

| ‘Why is he laughing so stupidly?!’ | ||||||

| (Munaro and Obenauer 1999: 238) | ||||||

The main point of these examples is that in both examples, the wh-element ‘what’ is not used to refer to a syntactic argument (like in What is he reading? [He is reading a book ]), but rather expresses a meaning close to ‘why’. This is particularly clear in examples like (1b). Here, only a non-argumental reading of ‘what’ is possible because of the intransitive verb ‘to laugh’—an argumental interpretation of the wh-element (like in What is he reading? [He is reading a book ] would result in ungrammaticality (*He is laughing x).

Crucially, as soon as interrogatives feature this ‘why-like-what’ reading of the wh-element, Munaro and Obenauer (1999: 237–238) point out that this obligatory conveys “an attitude of the speaker ranging from mild surprise to strong disapproval.” In other words, these configurations express a violation of the speaker’s expectation(s), and, at the level of illocutionary force, one could thus categorize them as exclamations (i.e., expressive speech acts that convey that a particular state-of-affairs has violated the speaker’s expectations). As is well known from the literature on exclamations, they can be conveyed by a wide range of syntactic forms, including interrogative syntax. Consider the following English examples, which are taken from Rett (2011: 412):

| a. | (Wow,) John bakes delicious desserts! |

| b. | (My,) What delicious desserts John bakes! |

| c. | (Boy,) Does John bake delicious desserts! |

| d. | (My,) The delicious desserts John bakes! |

Looking at the data in (3), we can see that exclamation is a speech act that does not correspond to a particular sentence type, and that the notion of exclamation instead might just refer to specific uses of several sentence types. According to this view, the interrogative examples in (1) could merely instantiate another option to realize an exclamation, and according to this claim we could thus say that the cases in (1) do not function as proper (read: information-seeking) questions anymore.

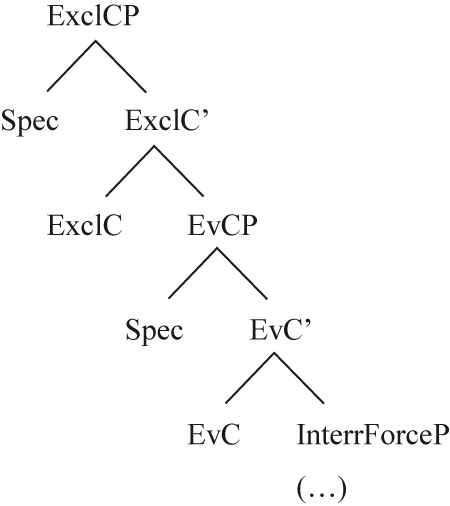

However, Munaro and Obenauer (1999) in their original proposal have taken a different path (and the syntactic literature adopting their proposal has as well; see Obenauer 2004, 2006; Giorgi 2016, 2018; and many others): In their account, Munaro and Obenauer’s (1999) claim that surprise-disapproval questions must be distinguished at the speech-act level from both information-seeking questions on the one hand and exclamations on the other hand. They formulate this claim by means of the so-called ‘cartographic’ framework, which represents discourse-related meaning components as left-peripheral syntactic projections (Rizzi 1997, 2014). One of the main ideas of this approach is to also encode illocutionary components of utterance meaning within the boundaries of sentence grammar (see also Krifka 2014, 2019). Adopting such a view on the relation between syntax and pragmatics, Munaro and Obenauer (1999) propose that the surprise-disapproval effect of cases like (1) above is encoded in a functional projection other than Interrogative Force. (3) represents the ordering of functional projections in Munaro and Obenauer’s (1999: 217–218) decomposed left periphery; see also Obenauer (2006: 266):

|

As (3) represents, there are two more functional projections above the projection encoding the interrogative force of the clause. Specifically, while SpecExcl(amation)CP is the landing site for wh-phrases in wh-exclamatives (e.g., How beautiful he is!), SpecEv(aluation)CP serves as a position for wh-phrases in non-canonical questions like (1) above. Accordingly, Munaro and Obenauer argue that special questions such as surprise questions (but also rhetorical questions etc.) are derived by adding functional structure on top of the structure encoding the question force of a clause (see also Nye 2009: chapter 2 on relevant pseudo-questions in English and a similar proposal).

There are many empirical aspects and conceptual assumptions underlying syntactic analyses like (3), which we cannot discuss in this paper; note that structural representations like (3) are controversial also within generative linguistics (Trotzke and Zwart 2014). But even if one shares the general theoretical framework behind structural claims like (3), one can still question some of its most basic assumptions (see Trotzke 2020). In particular, (3) is in line with prominent theories about exclamatives that posit a dedicated illocutionary force operator for exclamations. For instance, Rett’s (2011) ‘E-FORCE’ and Grosz’s (2012) EX operators instantiate it. Yet, unlike with questions—where a speech act operator returns a different semantic type (a question)—the alleged E-FORCE and EX return the original proposition (‘the at-issue content’) and a ‘not-at-issue’ proposition (in this case: surprise/amazement about p). One can thus wonder on conceptual grounds what exactly is achieved by postulating a distinct speech act operator for exclamations.

Note that it is a common theoretical claim in linguistic theory that so-called ‘major’ sentence types (König and Siemund 2007, 2013) like declaratives (4a), interrogatives (4b), and imperatives (4c) should be represented by distinct illocutionary operators:

| a. | That building is tall. |

| b. | Has that building been extended? |

| c. | Go to the top of that building! |

Proposing an operator for exclamations (and thus assuming that ‘exclamatives’ as a distinct sentence type exist) already adds a lot of controversial assumptions to the basic inventory in (4). As we have seen above, cartographic approaches that have investigated the phenomenon of surprise-disapproval questions in more detail even go one step further and propose an operator for ‘non-canonical’ speech acts like surprise-disapproval questions (e.g., an Evaluation Phrase in [3]).

We are merely indicating our doubts here about an analysis like (3) above because our goal in this paper is not in the first place a theoretical one. Rather, although our paper starts with and is empirically based on observations that have been pointed out in the cartographic literature, our study aims at empirically assessing theoretical claims about the illocutionary status of surprise-disapproval questions by exploring their pragmatics. In particular, we investigate the illocutionary status of questions like (1) by asking how speakers can react to surprise-disapproval questions in a discourse: Do they perceive them as requests for information in the first place? Or do they mainly interpret them as exclamation speech acts expressing the surprise of the speaker? By carrying out an acceptability study on how speakers react to surprise-disapproval questions, and by comparing those reactions to the ones we observe for both information-seeking questions and wh-exclamatives, we hope to contribute to answering questions about the illocutionary status of such non-canonical questions and about which pragmatic components of these non-canonical uses are predominantly perceived by speakers. In what follows, we will first present our empirical study in Section 2, and we will then turn back to the theoretical implications of our empirical investigation.

2 An empirical study on the pragmatics of surprise questions

The more recent literature on surprise-disapproval questions has identified many more syntactic phenomena that might fall into the category of surprise (or ‘counter-expectational’) questions, and the cases featuring ‘why-like-what’ readings were thus only the starting point of a still growing literature. For instance, configurations like English How come? or What the hell is he doing? are now characterized as surprise questions too (e.g., Celle 2018; Celle et al. 2019).

However, we hypothesize that ‘why-like-what’ is still the clearest example instantiating the category of surprise questions because we agree with the cartographic literature that as soon as ‘what’ receives the non-argumental reading of ‘why’ in interrogatives, the surprise-disapproval interpretation obligatorily follows. Note that this is different in most of the other cases cited in the literature. For instance, it has been pointed out that intensifiers like the hell are not only compatible with surprise interpretations (see Pesetsky 1987: 111), but also with other types of non-canonical questions that might lack a surprise interpretation. As Obenauer (2004: 376) illustrates, the hell is also compatible with the rhetorical-question interpretation (Who the hell cares?) or with the ‘Can’t-find-the-value’ interpretation (Where the hell did I leave my keys?). Given these considerations, our study only tested surprise-disapproval questions instantiated by ‘why-like-what’ readings, as illustrated in (1) above. The language investigated by our study was German since parallel cases to the Romance ‘why-like-what’ readings have many times been pointed out in the original literature on this topic (see Munaro and Obenauer’s 1999 example above [1]).

2.1 Materials and methods

2.1.1 Participants

Participants were 60 native speakers with German as their only native language. Their mean age was 38.7 years (sd = 11.8, max = 65, min = 19). 26 participants were male. Participants were recruited through Clickworker’s crowd-sourcing service.[1]

2.1.2 Language material

The language material consisted of a short context followed by a dialogue. In the dialogue, the first speaker uttered a sentence of one of three types: (a) an information-seeking question, (b) an exclamative, or (c) a surprise-disapproval question. The second speaker then responded with a reaction of one of two types: (a) an answer, or (b) an affirmation (see below for more details). The participants’ task was to rate the appropriateness of the second speaker’s reaction, given the preceding context and utterances. Crucially, all three utterance types of the first speaker were constructed with the German version of ‘what’ (was). That is, in information-seeking questions, was occurred with transitive verbs and hence an empty argument slot. In exclamatives, was always featured the degree reading that is typical for that particular wh-element in exclamation speech acts (similar to English What a in What a beautiful city!). In surprise-disapproval questions (closely following the original literature introduced in Section 1), was always occurred with intransitive verbs, and so the ‘why-like-what’ reading was the only way to interpret the respective utterances. Speaker B’s reaction was either an answer or an affirmation. We take an ‘answer’ to be a reaction that provides the missing information referred to by the wh-element (the syntactic object in an argumental ‘what’ reading and the reason in the ‘why-like-what’ reading). An affirmation in turn represents a reaction that we expected to be felicitous in the case of exclamatives: Although Speaker B cannot provide an ‘answer’ to an exclamation (see Grimshaw 1979; Zanuttini and Portner 2003; and many others), he can of course affirm the expression of surprise on the part of the speaker. The following pattern is adopted from Zanuttini and Portner (2003: 47):

| A: | How very tall he is! | |

| B:* | Seven feet. | [answer] |

| B′: | He really is! Indeed! | [affirmation] |

All in all, we constructed four sets of critical items and four sets of filler items. An illustration of a full critical item set is given in Example 1:

|

INFORMATION-SEEKING

Fabian ist aufgefallen, dass sich Uli öfters Bücher in der Bibliothek ausleiht. |

||

| Fabian: | „Was hast du denn zuletzt gelesen?“ | |

| [answer] | Uli: | „Ich verrate es dir: Das letzte Buch war ein Roman von Thomas Mann.“ |

| [affirmation] | Uli: | „Da hast du recht: Ich wollte in der letzten Woche eigentlich gar nichts lesen.“ |

| Fabian noticed that Uli often borrows books from the library. | ||

| Fabian: | “What is the last thing you read?” | |

| [answer] | Uli: | “I will tell you: The last book was a novel by Thomas Mann.” |

| [affirmation] | Uli: | “You are right: I was not planning to read anything at all last week.” |

|

EXCLAMATIVE

Eva trifft Laura und weiß, dass Lauras Mann Markus wieder gebacken hat. |

||

| Eva: | „Was der aber auch für leckere Kuchen gebacken hat!“ | |

| [answer] | Laura: | „Oh, das weißt du nicht? Er hat einen Schoko- und einen Nusskuchen gebacken.“ |

| [affirmation] | Laura: | „Ja, das stimmt, er ist wirklich ein sehr guter Bäcker.“ |

| Eva meets Laura and knows that Laura’s husband Markus has been baking again. | ||

| Eva: | “What delicious pies he made!” | |

| [answer] | Laura: | “Oh, you don’t know? He made a chocolate and a nut pie.” |

| [affirmation] | Laura: | “Yes, that’s true, he really is very good at baking.” |

|

SURPRISE

Julia sieht, dass Marc sich mitten am Tag hinlegen möchte. Dabei dachte sie, dass sie den Nachmittag miteinander verbringen. |

||

| Julia: | „Was schläfst du denn jetzt?!“ | |

| [answer] | Marc: | „Oh, das weißt du nicht? Ich bin gestern Abend spät ins Bett gegangen, |

| darum lege ich mich noch mal hin.“ | ||

| [affirmation] | Marc: | „Du hast recht: Eigentlich hatte ich dir versprochen, |

| dass wir den Nachmittag zusammen verbringen.“ | ||

| Julia sees that Marc is going to lie down in the middle of the day. However, she thought that they were going to spend the afternoon together. | ||

| Julia: | “What are you doing sleeping now?” | |

| [answer] | Marc: | “Oh, you don’t know? I went to bed late yesterday, that is why I am lying down again.” |

| [affirmation] | Marc: | “You are right, I promised you we would spend the afternoon together.” |

Example 1:

Example of one set of critical stimuli. Dialogues are grouped by utterance type. All utterance types were presented either with reaction [answer] or reaction [affirmation]. English translations are provided below the German original.

With information-seeking questions, we expected an answer to be rated as appropriate, and an affirmation to be rated as inappropriate. With exclamatives, we expected an answer to be rated as inappropriate, and an affirmation as appropriate. For surprise questions, the rating pattern should be informative about their preferred interpretation and thus about their illocutionary status; see our discussion above.

To test whether participants understood the task of judging the mini-dialogues, we constructed four fillers we expected to get good judgments (‘good’ fillers), four fillers we expected to get bad judgments (‘bad’ fillers), and four fillers we expected to receive mixed judgments (‘medium’ fillers); ‘good’, ‘bad’, and ‘medium’ describing the appropriateness of the reactions. This methodology has already been proven to be useful in a previous study on the use of exclamatives in discourse (Trotzke 2019). Fillers were also short dialogues preceded by a context. However, the first utterances were declaratives or information-seeking questions only. An example of a full filler set is given in Example 2:

|

GOOD

Irene sieht, dass es draußen sehr windig ist und macht sich Sorgen um ihren Mann Klaus. |

|

| Irene: | „Nimm lieber die warme Jacke mit!“ |

| Klaus: | „Okay, mache ich.“ |

| Irene sees that it is very windy outside and is worried about her husband Klaus. | |

| Irene: | “Better take the warm jacket!” |

| Klaus: | “Ok, I will do that.” |

|

MEDIUM

Manfred und Inge verabreden, dass Manfred heute Abend einkaufen geht. |

|

| Inge: | „Bring auch noch ein Pfund Tomaten mit!“ |

| Manfred: | „Ja, das stimmt.“ |

| Manfred and Inge agree that Manfred will go shopping tonight. | |

| Inge: | “Please bring a pound of tomatoes as well.” |

| Manfred: | “Yes, that is right.” |

|

BAD

Carmen ist mit ihrer besten Freundin zusammen einkaufen. |

|

| Carmen: | „Welches Kleid soll ich nehmen?“ |

| Freundin: | „Ja, das stimmt.“ |

| Carmen is shopping with her best friend. | |

| Carmen: | “Which dress should I pick?” |

| Friend: | “Yes, that is right.” |

Example 2:

Example of one set of fillers. Dialogues are grouped by the expected felicity of the reaction. English translations are provided below the German original.

Each participant saw 36 items, with four dialogues per condition.

2.1.3 Procedure

The experiment was performed as an online rating study in SoSciSurvey.[2] Before the start of the experiment, participants were instructed in written form, and performed three practice ratings. Each item was presented in a screen of its own. Ratings were collected on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 the worst and 7 the best rating. Scale points were marked with numbers from 1 to 7. In addition, the lowest scale point was marked as “unangemessen” (‘inappropriate’) and the highest scale point was marked as “angemessen” (‘appropriate’). The experiment lasted approximately 10 min.

2.2 Results

2.2.1 Critical conditions

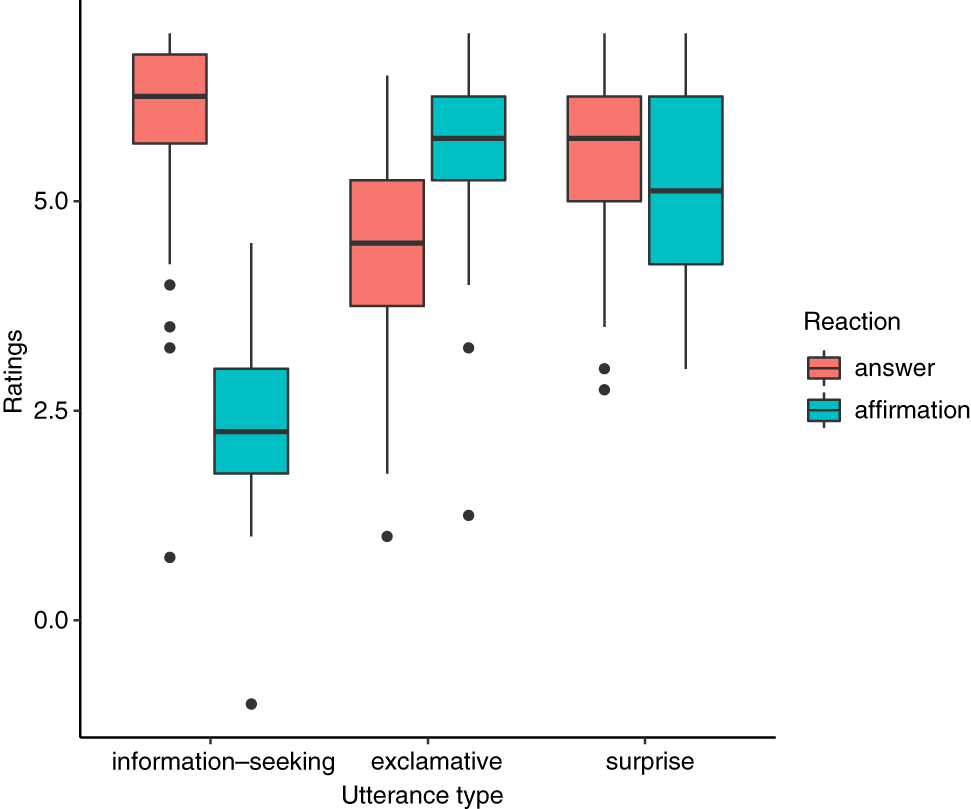

Descriptively, the ratings for information-seeking questions were higher with answers (5.94) than affirmations (2.38). For exclamatives, ratings were lower with answers (4.38) than with affirmations (5.65), although both were still in the acceptable range. For surprise questions, ratings were slightly higher with answers (5.54) than with affirmations (5.22), although the difference was less marked than for the other question types. Mean ratings for the critical conditions are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Mean ratings per condition across participants for critical items. Standard deviations and standard errors of the mean are given in parentheses.

| Utterance type | Reaction | Mean rating |

|---|---|---|

| Information-seeking | Answer | 5.94 (sd 1.11, sem 0.14) |

| Affirmation | 2.38 (sd 1.01, sem 0.13) | |

| Exclamative | Answer | 4.38 (sd 1.22, sem 0.16) |

| Affirmation | 5.65 (sd 1.06, sem 0.14) | |

| Surprise–disapproval | Answer | 5.54 (sd 1.00, sem 0.13) |

| Affirmation | 5.22 (sd 1.14, sem 0.15) |

Boxplots of mean ratings per condition for critical items.

Ratings were analyzed in R (R Core Team 2017) with a series of linear mixed models, using the packages lme4 (Bates et al. 2015, lme4 function), and LMERConvenienceFunctions (Tremblay and Ransijn 2015, summary function). Plots were prepared using the ggplot2 package (Wickham 2016). For the first model, we specified the main effects and interactions of factors UTTERANCE TYPE (three levels: information-seeking, exclamative, surprise-disapproval) and REACTION (two levels: answer and affirmation) as fixed effects, and PARTICIPANT and ITEM as random effects. In addition, REACTION was specified as random slope for each participant. In addition to significant main effects, there was a statistically significant interaction of UTTERANCE TYPE and REACTION (information-seeking vs. exclamative: t = −22.98, p < 0.001; information-seeking vs. surprise-disapproval: t = −15.45, p < 0.001; exclamative vs. surprise-disapproval: t = 7.53, p < 0.001). This interaction was pursued by monitoring the main effect of REACTION separately for each level of UTTERANCE TYPE. For the second model, we specified the main effect of REACTION as fixed effect, PARTICIPANT and ITEM as random effects, and REACTION as random slope for each participant. The main effect of REACTION was statistically significant for information-seeking questions (t = 17.11, p < 0.001) and exclamatives (t = −6.88, p < 0.001). For surprise-disapproval questions, the main effect of REACTION was only marginally significant (t = 1.85, p < 0.07).

2.2.2 Fillers

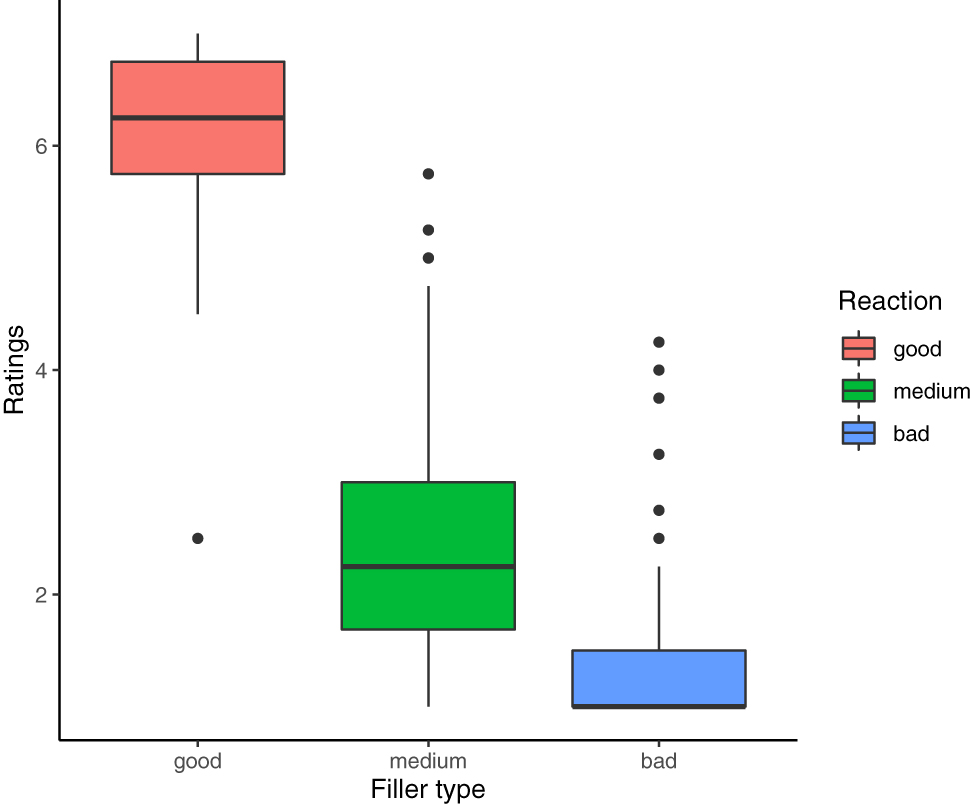

Descriptively, fillers were rated as expected, with high ratings for good fillers, low ratings for bad fillers, and medium ratings for medium fillers. Mean ratings for the fillers are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Mean ratings per condition across participants for fillers. Standard deviations (sd) and standard errors of the mean (sem) are given in parentheses.

| Filler type | Mean rating |

|---|---|

| Good | 6.19 (sd 0.82, sem 0.11) |

| Medium | 2.48 (sd 1.16, sem 0.15) |

| Bad | 1.43 (sd 0.83, sem 0.11) |

Boxplots of mean ratings per condition for fillers.

Ratings for fillers were analyzed with a third model (parallel to the second model outlined above). We specified the main effect of FILLER TYPE as fixed effect, PARTICIPANT and ITEM as random effects, and FILLER TYPE as random slope for each participant. There was a main effect of FILLER TYPE (good vs. bad: t = −26.27, p < 0.001; good vs. medium: t = −17.94, p < 0.001; medium vs. bad: t = −7.96, p < 0.001).

3 Discussion and conclusion

In this final section, we would like to briefly discuss the results of our empirical study on the pragmatics of surprise-disapproval questions. First, we conclude that participants overall understood the rating task they were presented with. In particular, we found that ratings for all three filler conditions are different from one another, and participants’ preferences for the appropriate reaction for each condition fit our expectations. This shows that our task is sensitive enough to distinguish reactions of varying felicity, and does so in more detail than providing simple quasi-binary distinctions.

The main findings of our empirical study concern the critical items. Specifically, we found—rather unsurprisingly—that the preferred reaction to an information-seeking question is an answer; affirmations are clearly dispreferred. The preferred reaction to exclamatives is affirmation; this is in line with the theoretical literature on exclamatives showing that although an exclamative cannot be answered (6B), the descriptive content of the exclamative (which is presupposed) can be affirmed by the hearer ([6B′]; see Castroviejo Miró 2006; Chernilovskaya et al. 2012; Grimshaw 1979; Zanuttini and Portner 2003). Consider the following pattern again (Zanuttini and Portner 2003: 47), repeated from (5):

| A: | How very tall he is! | |

| B:* | Seven feet. | [answer] |

| B′: | He really is! Indeed! | [affirmation] |

Interestingly, our data suggest that although ratings for exclamatives with affirmation were significantly higher than those for exclamatives with answers, the latter still showed higher ratings than expected. In particular, the exclamative–answer pattern suggests that this reaction is perceived as more felicitous than the information-seeking–affirmative condition. This might reflect a bias of our paradigm towards an interrogative interpretation. Another explanation is that participants perceive the descriptive content of an exclamative as still being ‘at-issue’ and not presupposed. In other words, participants might have thought that the speaker has no settled belief about the proposition conveyed by an exclamative (e.g., ‘He bakes delicious pies’ in an exclamative like What delicious pies he bakes!), and that the proposition is thus still ‘at-issue’ (see Villalba 2017 for such an account) and not so far in the conversational background than usually assumed in the theoretical literature (e.g., Zanuttini and Portner 2003 and their analysis of the relevant proposition in terms of a factivity presupposition).

Turning now to the main point of our paper, namely the results we obtained for the pragmatics of surprise-disapproval questions, we observed that both types of reactions (i.e., answer and affirmation) are rated as felicitous. While there is a small descriptive preference for answers over affirmations, the difference between both reactions is only marginally significant. We interpret this as showing that in the case of surprise-disapproval questions there is actually no preference for one of the two reaction types—neither for answer nor for affirmation.

This finding suggests that surprise-disapproval questions are indeed perceived as both question and exclamation speech acts and thus contrast with both information-seeking questions (where we found a significant preference for answer) and exclamatives (this utterance type is preferred with affirmations). The question is now how to interpret this result theoretically (and in the light of the cartographic literature sketched in Section 1) because it is rather uncontroversial that surprise-disapproval questions belong to a ‘mixed’ clause and speech act category, featuring formal and functional properties of different illocutionary forces. Our experiment thus seems to confirm this general characterization.

However, we would like to point out that our results are particularly compatible with a broad theory that assumes that pragmatic phenomena like surprise-disapproval questions are truly ‘mixed types’ in the sense that we do not have to postulate a distinct illocutionary status (or, in syntactic terms, a distinct projection) in order to explain them theoretically. By contrast, we suggest that surprise-disapproval questions might be felicitous with answers (and noticeably more felicitous than wh-exclamatives) because they share the basic word order with information-seeking questions (V2 order), and differ from our cases of wh-exclamatives in this regard (they were all verb-final). We could explain this by a broad illocutionary theory like Truckenbrodt’s (2006) account, which suggests for German that the V-to-C movement property in wh-questions results in a special pragmatics that verb-final exclamatives (like the items in our experiment) lack. Since surprise-disapproval questions in our items feature V-to-C movement (Was lacht der?!), and exclamatives lack it (Was der lacht!), surprise-disapproval question still fall into one grammatical category with their information-seeking counterparts (Was liest er?).

On the other hand, our experiment has shown that surprise-disapproval questions are also felicitously followed by affirmations, which is the reaction type that has also been preferred by our participants for exclamations. We submit that this cannot (and therefore should not) be explained by syntax because many factors at different linguistic levels add up and cumulate to yield the exclamation component of surprise-disapproval questions (certainly lexical items like the special and non-canonical reading of was, but also exclamative intonation, which we did not test in our experiment).

To be sure, factors at different linguistic levels are involved in yielding an interrogative reading in regular (read: information-seeking) wh-questions too—most notably intonation. Our claim here merely is that only the interrogative reading (of both information-seeking and surprise-disapproval questions) requires a dedicated word order and thus must involve syntax proper. This explains the pattern that surprise-disapproval questions cannot only be felicitously followed by affirmations (= signaling their exclamation component), but also by answers (= signaling their interrogative component): The V2 word order has an effect on the interpretation of surprise-disapproval questions because this is the feature that they have in common with information-seeking questions and that distinguishes them from the exclamatives we tested in our experiment.

To conclude, we submit that the only thing that is really due to word order and thus part of the syntax of mixed speech act types such as surprise-disapproval questions is the interrogative component (yielded by wh- + V-to-C movement), but the exclamation component should maybe not be part of and represented in the grammar, in contrast to previous syntactic claims along the lines of cartography. Such a ‘mixed’ theory (combining grammar/word order and non-syntactic means to yield the respective interpretations) is needed for many other mixed clause and speech act types like the more recent English How cool is that?! and its counterparts in further Germanic languages (Auer 2016; Trotzke 2020).

Funding source: German Research Foundation, FOR 2111 German Academic Exchange Service/DAAD, 57444809 EU Horizon

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2017-BP00031

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the German Research Foundation (DFG research unit “Questions at the Interfaces,” FOR 2111) and the German Academic Exchange Service/DAAD (PPP project “Surprise Questions from a Comparative Perspective,” grant no. 57444809) for financial support. Andreas Trotzke additionally acknowledges financial support from the EU Horizon 2020 COFUND scheme for the project “Functional categories and expressive meaning” (grant no. 2017-BP00031).

References

Auer, Peter. 2016. “Wie geil ist das denn?” Eine Konstruktion im Netzwerk ihrer Nachbarn. Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik 44. 69–92. https://doi.org/10.1515/zgl-2016-0003.Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67. 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Search in Google Scholar

Castroviejo Miró, Elena. 2006. Wh-exclamatives in Catalan. Universitat de Barcelona PhD Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Celle, Agnès. 2018. Questions as indirect speech acts in surprise contexts. In Dalila Ayoun, Agnès Celle & Laure Lansari (eds.), Tense, aspect, modality, evidentiality: Crosslinguistic perspectives, 213–238. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/slcs.197.10cel.Search in Google Scholar

Celle, Agnès, Anne Jugnet, Laure Lansari & Tyler Peterson. 2019. Interrogatives in surprise contexts in English. In Natalie Depraz & Agnès Celle (eds.), Surprise at the intersection of phenomenology and linguistics, 117–137. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/ceb.11.07celSearch in Google Scholar

Chernilovskaya, Anna, Cleo Condoravdi & Sven Lauer. 2012. On the discourse effects of wh-exclamatives. In Nathan Arnett & Ryan Bennett (eds.), Proceedings of the 30th west coast conference on formal linguistics, 109–119. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla.Search in Google Scholar

Giorgi, Alessandra. 2016. On the temporal interpretation of certain surprise questions. SpringerPlus 5. 1390. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2951-5.Search in Google Scholar

Giorgi, Alessandra. 2018. Ma non era rosso? (But wasn’t it red?): On counter-expectational questions in Italian. In Lori Repetti & Francisco Ordóñez (eds.), Selected papers from the 46th linguistic symposium on Romance languages (LSRL), 69–84. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/rllt.14.05gio.Search in Google Scholar

Grimshaw, Jane. 1979. Complement selection and the lexicon. Linguistic Inquiry 10. 279–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/chin.197923065.Search in Google Scholar

Grosz, Patrick. 2012. On the grammar of optative constructions. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.193.Search in Google Scholar

König, Ekkehard & Peter Siemund. 2007. Speech act distinctions in grammar. In Timothy Shopen (ed.), Language typology and syntactic description, 276–324. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511619427.005Search in Google Scholar

König, Ekkehard & Peter Siemund. 2013. Satztyp und Typologie. In Jörg Meibauer, Markus Steinbach & Hans Altmann (eds.), Satztypen des Deutschen, 846–873. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110224832.846Search in Google Scholar

Krifka, Manfred. 2014. Embedding illocutionary act. In Tom Roeper & Margaret Speas (eds.), Recursion: Complexity in cognition, 125–155. Dordrecht: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-05086-7_4Search in Google Scholar

Krifka, Manfred. 2019. Layers of assertive clauses: Propositions, judgements, commitments, acts. To appear in. In Jutta Hartmann & Angelika Wöllstein (eds.), Propositionale Argumente im Sprachvergleich: Theorie und Empirie. Tübingen: Narr.Search in Google Scholar

Munaro, Nicola & Hans-Georg Obenauer. 1999. On underspecified wh-elements in pseudo-interrogatives. University of Venice Working Papers in Linguistics 9. 181–253.Search in Google Scholar

Nye, Rachel. 2009. How pseudo-questions and the interpretation of wh-clauses in English. University of Essex MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Obenauer, Hans-Georg. 2004. Non-standard wh-questions and alternative checkers in Pagotto. In Horst Lohnstein & Susanne Trissler (eds.), The syntax and semantics of the left periphery. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110912111.343Search in Google Scholar

Obenauer, Hans-Georg. 2006. Special interrogatives: Left periphery, wh-doubling, and (apparently) optional elements. In Jenny Doetjes & Paz González (eds.), Romance languages and linguistic theory, Vol. 2004, 247–273. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.278.12obe.Search in Google Scholar

Pesetsky, David. 1987. Wh-in-situ: Movement and unselective binding. In Eric Reuland & Alice Ter Meulen (eds.), The representation of (in)definiteness, 98–129. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2017. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna: Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.Search in Google Scholar

Rett, Jessica. 2011. Exclamatives, degrees and speech acts. Linguistics and Philosophy 34. 411–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-011-9103-8.Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Liliane Haegeman (ed.), Elements of grammar: Handbook in generative syntax, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-5420-8_7.Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 2014. Syntactic cartography and the syntacticisation of scope-discourse semantics. In Anne Reboul (ed.), Mind, values, and metaphysics, 517–533. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05146-8_30.Search in Google Scholar

Tremblay, Antoine & Johannes Ransijn. 2015. LMERConvenienceFunctions: Model selection and post-hoc analysis for (g)lmer models. R package version 2.10. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315703497. https://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=LMERConvenienceFunctions.Search in Google Scholar

Trotzke, Andreas. 2019. Approaching the pragmatics of exclamations experimentally. In Eszter Ronai, Laura, Stigliano & Yenan, Sun (eds.), Proceedings of the 54th annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS 54), Chicago, 527–540. Chicago Linguistic Society.Search in Google Scholar

Trotzke, Andreas. 2020. How cool is that! A new ‘construction’ and its theoretical challenges. The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 23. 327–365.10.1007/s10828-020-09120-2Search in Google Scholar

Trotzke, Andreas & Jan-Wouter Zwart. 2014. The complexity of narrow syntax. In Frederick Newmeyer & Laurel Preston (eds.), Measuring grammatical complexity, 128–147. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199685301.003.0007.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199685301.003.0007Search in Google Scholar

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 2006. On the semantic motivation of syntactic verb movement to C in German. Theoretical Linguistics 32. 257–306. https://doi.org/10.1515/tl.2006.018.Search in Google Scholar

Villalba, Xavier. 2017. Non-asserted material in Spanish degree exclamatives: An experimental study on extreme degree. In Ignacio Bosque (ed.), Advances in the analysis of Spanish exclamatives, 139–158. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Wickham, H. 2016. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4Search in Google Scholar

Zanuttini, Raffaella & Paul Portner. 2003. Exclamative clauses: At the syntax-semantics interface. Language 79. 39–81. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2003.0105.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Andreas Trotzke and Anna Czypionka, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Non-canonical questions from a comparative perspective: Introduction to the special collection

- A comparative corpus study on a case of non-canonical question

- Interpreting high negation in Negative Interrogatives: the role of the Other

- French questions alternating between a reason and a manner interpretation

- The pragmatics of surprise-disapproval questions: An empirical study

- Non-standard questions in English, German, and Japanese

- Timing of belief as a key to cross-linguistic variation in common ground management

- The prosody of French rhetorical questions

- Surprise questions in spoken French

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Non-canonical questions from a comparative perspective: Introduction to the special collection

- A comparative corpus study on a case of non-canonical question

- Interpreting high negation in Negative Interrogatives: the role of the Other

- French questions alternating between a reason and a manner interpretation

- The pragmatics of surprise-disapproval questions: An empirical study

- Non-standard questions in English, German, and Japanese

- Timing of belief as a key to cross-linguistic variation in common ground management

- The prosody of French rhetorical questions

- Surprise questions in spoken French