Introduction

Mental illness is a substantial public health and economic issue. In 2004, for example, 25% of adults in the United States reported having a mental illness in the previous year [1]. People with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are at a significantly higher risk of mental illness, with the prevalence of co-occurring IDD and mental illness conservatively estimated at 33%, and some sources reporting much higher rates [2]. These prevalence data may not offer a true picture of mental health disease in the population, and we are confident that mental illness is not reliably diagnosed among people with IDD, frequently attributed to the IDD than contemplated as a legitimate mental health concern.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses population-based surveys and surveillance systems to provide information for planning effective mental health promotion, mental illness prevention and treatment programs. CDC surveillance systems provide several types of mental health information from different sources: estimates of the prevalence of diagnosed mental illness from self-report or recorded diagnosis; estimates of the prevalence of symptoms associated with mental illness; and estimates of the impact of mental illness on health and well-being [1]. CDC surveys are concerned with the general population and do not specifically examine the population of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and mental health issues.

Intellectual and developmental disabilities

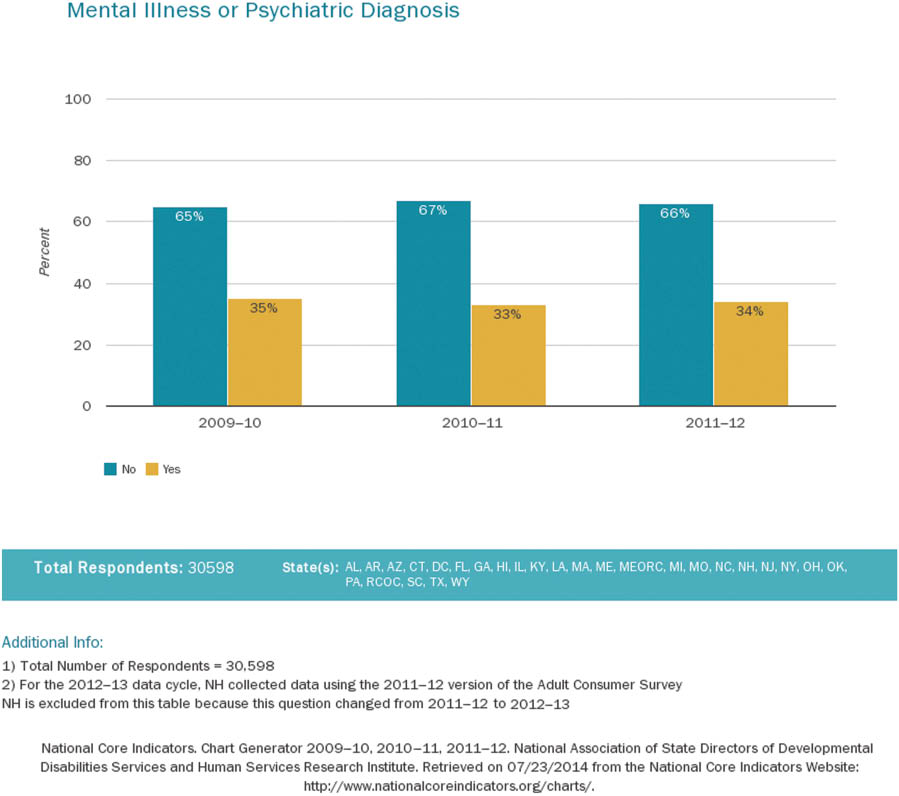

Over the 3-year period ending in 2012, the US-based National Core Indicators project surveyed more than 30,000 adults with IDD across 27 states and regions in the United States for the presence of co-occuring mental illness. Between 33% and 35% of all respondents were diagnosed with a mental illness (see Figure 1).

National core indicators, co-occurring IDD and mental illness.

NADD, an association for persons with developmental disabilities and mental health needs, holds that coexisting IDD and a psychiatric disorder interferes with a person’s education and job readiness and disrupts family and peer relationships. A recent study found over 40% of a cohort of 1318 adults with IDD were diagnosed with four or more comorbidities, including 18% diagnosed with anxiety disorder and 17.8% with depression [3].

We are, at the same time, aware that people with IDD are living much longer than at any time in history. There are an estimated 850,600 people with IDD aged 60 years and older [4, 5] in the United States, and their numbers will likely double over the next 2 decades as members of the “baby boom” generation reach retirement age. This is an unprecedented development inasmuch as the average life expectancy of people with developmental disabilities was just 22 years in 1931, compared to 59 years in 1976 and 66 years in 1993. Two studies found the average age of death for persons with IDD is now 63.3 years for males and 69.9 years for females [6, 7]. These and other demographic trends indicate that our healthcare delivery systems and approaches must meaningfully coordinate primary, mental and behavioral and other specialty care to address a variety of complex healthcare needs, health status and outcomes for people with IDD [8].

The convergence of these data also suggests a substantial and potentially growing number of people with IDD who will need formal mental health supports. Surveillance systems dedicated to early indentification of this specific set of needs are historically inadequate and need to be improved. Beyond identification, treatment modalities must be developed that are responsive to the relationship between individuals’ IDD and mental health needs, should be integrated with general health in such a way to consider the person holistically, and must be developed in ways to maximize existing healthcare financing structures, if not developing new funding systems altogether.

Treatment integration

We believe there are a host of benefits of integrating mental, behavioral and primary healthcare, including reduced costs, increased identification of mental health issues, increased accessibility to mental health services and improved patient outcomes [9–14]. Traditionally, healthcare for individuals with IDD has been parsed out to multiple providers and/or agencies along disparate funding lines. Health, mental health and behavioral providers are often housed separately and regulated and funded by different governmental entities. Bringing together those disciplines who have traditionally served individuals with IDD, although ideal, poses challenges to the status quo and is made more difficult by regulations and systems of financing that are based on diagnoses over actual need for or perceived benefits of particular services and interventions. Throughout the US, certain mental and behavioral health services tend to be available to people because they have a psychiatric or mental health diagnosis, whereas other services are available to people in explicit relationship to their IDD. This approach misses the potential to make treatment services available based on the particular symptoms, needs and desires of a person as primary drivers of service availability and delivery. Although diagnoses are important, their presence or absence should not be the most important factor in whether or not services are available and accessed. People who are diagnosed with both an IDD and a mental health concern are far-too-frequently caught between two systems.

There are few models of care that offer fully integrated mental and behavioral health treatment. Two of note in the United States are the Developmental Disabilities Health Center (DDHC) [15] in Colorado and New Jersey’s DD Health Home model [16]. The efficacy of these models, as measured by a range of factors–from patient satisfaction to emergency room visits and hospitalizations–is compelling.

Conclusions

There is a substantial and rapidly growing cohort of people with IDD and mental illness. However, the availability of intregrated treatment models continues to lag far behind the need. On the basis of sheer numbers alone, there is a compelling need to develop integrated treatment options and capacity. We are aware of the benefits of care integration found in the delivery of multidisciplinary, integrated health care to individuals with IDD. Practitioners and others interested in enhancing the wellbeing and health outcomes of individuals with IDD must therefore continue to seek collaboration, not only among themselves, but across disciplines to include all members of interdisciplinary teams [8].

The development of models that integrate mental and behavioral healthcare with primary healthcare will require work in public policy, financing and reimbursement systems and establishing new healthcare cultural norms through training of healthcare providers on the benefits of integrated care. However, the benefits of integrated care make for compelling reasons to address these challenges.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Reeves WC, Strine TW, Pratt LA, Thompson W, Ahluwalia I, Dhingra SS, et al. Mental illness surveillance among adults in the United States. MMWR Suppl 2011;60:1–32.Search in Google Scholar

2. Quintero M, Flick S. Co-occurring mental illness and developmental disabilities. Soc Work Today 2010;10;5–6.Search in Google Scholar

3. Rimmer JH, Hsieh K. Longitudinal Health and Intellectual Disability Study (LHIDS) on obesity and health risk behaviors. Proceedings of the Lifespan Health and Function of Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: Translating Research into Practice, State of the Science Conference, Bethesda, MD, 2011.Search in Google Scholar

4. Larson SA, Lakin KC, Anderson L, Nohoon K, Lee JH, Anderson D. Prevalence of mental retardation and developmental disabilities: Estimates from the 1994/1995 National Health Interview Survey Disability Supplements. Am J Ment Retard 2001;6:231–52.10.1352/0895-8017(2001)106<0231:POMRAD>2.0.CO;2Search in Google Scholar

5. US Census Bureau. DP-1 – United States: Profile of general population and housing characteristics: 2010, 2010 Demographic Profile Data. Availble at: http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/Aging_Statistics/Census_Population/census2010/Index.aspx.Search in Google Scholar

6. Walker L, Rinck C, Horn V, McVeigh T. Aging with developmental disabilities: Trends and best practices. Kansas City, MO: University of Missouri Kansas City Institute for Human Development and the Missouri Division of MR/DD, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

7. Long T, Kavarian S. Aging with developmental disabilities: An overview. Topics Geriatr Rehabil 2008;24:2–11.10.1097/01.TGR.0000311402.16802.b1Search in Google Scholar

8. Ervin DA, Williams A, Merrick J. Primary care: Mental and behavioral health and persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Front Public Health 2014;2:76.10.3389/fpubh.2014.00076Search in Google Scholar

9. Funk M, Saraceno B, Drew N, Faydi E. Integrating mental health into primary healthcare. Ment Health Fam Med 2008;5:5–8.Search in Google Scholar

10. Katon WJ, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, Cowley D. Cost-effectiveness and cost offset of a collaborative care intervention for primary care patients with panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:1098–104.10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1098Search in Google Scholar

11. Kates N, McPherson-Doe C, George L. Integrating mental health services within primary care settings: the Hamilton Family Health Team. J Ambul Care Manage 2011;34:174–82.10.1097/JAC.0b013e31820f6435Search in Google Scholar

12. Bryan CJ, Morrow C, Appolonio KK. Impact of behavioral health consultant interventions on patient symptoms and functioning in an integrated family medicine clinic. J Clin Psychol 2009;65:281–93.10.1002/jclp.20539Search in Google Scholar

13. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, Walker E, Unützer J, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:1109–15.10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109Search in Google Scholar

14. Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, Simon G, Ludman E, Russo J, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care inpatients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:1042–9.10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042Search in Google Scholar

15. Ervin DA, Hennen B, Merrick J, Morad M. Healthcare for persons with intellectual and developmental disability in the community. Front Public Health 2014;2:83.10.3389/fpubh.2014.00083Search in Google Scholar

16. Kastner TA,Walsh KK. Healthcare for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Int Rev Res Dev Disabil 2012;43:1–45.10.1016/B978-0-12-398261-2.00001-5Search in Google Scholar

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- Adults, mental illness and disability

- Chronic illness, disease and impairment: living longer, living well

- Review

- Navigational audio games: an effective approach toward improving spatial contextual learning for blind people

- Mini Review

- Conscious capitalism to help people with hearing disability in developing countries

- Original Articles

- The influence of vibration on the quality of gait in women with cerebral palsy

- Attitudes of medical students toward disabilities in Nigeria

- A novel speech synthesizer using 3D facial model with gestures

- Comparison of kangaroo mother care and tactile kinesthetic stimulation in low birth weight babies – an experimental study

- Control of hypertension and diabetes among adults aged over 40 years with or without physical disabilities

- Association between quality of life and team achievement among wheelchair basketball players – a survey study

- A case of savant syndrome in a child with autism spectrum disorder

- Community physiotherapy in India: short review on research

- Prevalence of victimization, and associated risk factors, impacting youth with disabilities in Vietnam: a population-based study

- Challenge and promotion: influence of religion on Tibetan special education

- Case Reports

- Right thalamic lacunar infarction presenting with anomic aphasia

- G20210A mutation and cerebral venous infarct: a rare presentation in a child

- Letter to the Editor

- Zaro Agha, The legendary Kurdish supercentenarian

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- Adults, mental illness and disability

- Chronic illness, disease and impairment: living longer, living well

- Review

- Navigational audio games: an effective approach toward improving spatial contextual learning for blind people

- Mini Review

- Conscious capitalism to help people with hearing disability in developing countries

- Original Articles

- The influence of vibration on the quality of gait in women with cerebral palsy

- Attitudes of medical students toward disabilities in Nigeria

- A novel speech synthesizer using 3D facial model with gestures

- Comparison of kangaroo mother care and tactile kinesthetic stimulation in low birth weight babies – an experimental study

- Control of hypertension and diabetes among adults aged over 40 years with or without physical disabilities

- Association between quality of life and team achievement among wheelchair basketball players – a survey study

- A case of savant syndrome in a child with autism spectrum disorder

- Community physiotherapy in India: short review on research

- Prevalence of victimization, and associated risk factors, impacting youth with disabilities in Vietnam: a population-based study

- Challenge and promotion: influence of religion on Tibetan special education

- Case Reports

- Right thalamic lacunar infarction presenting with anomic aphasia

- G20210A mutation and cerebral venous infarct: a rare presentation in a child

- Letter to the Editor

- Zaro Agha, The legendary Kurdish supercentenarian