Valorisation the bark of forest species as a source of natural products within the framework of a sustainable bioeconomy in the Amazon

-

Elesandra da Silva Araujo

, Graciene da Silva Mota

, Jéfyne Campos Carréra

, Mário Sérgio Lorenço

, Carlos Alberto de Souza

Abstract

The aim was to evaluate the potential of the stem bark of Byrsonima spicata, Croton matourensis, Myrcia splendens, Tapirira guianensis and Vismia guianensis as a source of value-added macromolecules to contribute to the bioeconomy in the Amazon. The barks were collected from secondary forests in the state of Pará, Brazil, and analysed for the first time for anatomical and chemical composition. High-performance microscopic images showed the presence of a rhytidome composed of one to seven layers of periderms. The bark had a significant presence of extractives soluble in ethanol and water (from 29.3 to 46.1 %). Lignin content ranged from 19.0 to 33.4 %. The optical emission spectrometer showed a rich mineral composition, particularly in calcium (2.9–20.6 g kg−1 of bark). High tannin content was quantified, especially in B. spicata (19.1 %) and M. splendens (29.9 %). The composition of the bark suggests that it can be used to obtain potentially valuable phenolic compounds with chemical functionalities and bioactivities. After this extraction, the lignin-rich solid residue is suitable for a thermochemical valorisation, while the high nutrient levels make soil amendment an interesting application. A sustainable bark removal may therefore generate local income and contribute to the conservation of these Amazonian species.

1 Introduction

The Amazon is the largest Brazilian biome, covering more than 40 % of the territory, with an area of approximately 4.2 million km2 consisting of different ecosystems, such as dense upland forests, seasonal forests, igapó forests, flooded fields, floodplains, savannahs, mountain refuges and pioneer formations (Brazilian Institute of Forestry 2022).

Despite its immeasurable importance, this region has been under constant threat from the advance of deforestation, which could cause the extinction of several typical species and trigger numerous environmental problems. According to the Brazilian Institute of Forestry (2022), approximately 16 % of the Brazilian Amazon has already been devastated. The expansion of soybean plantations and pastures for cattle ranching, together with illegal logging and mining, are currently the main threats to the Amazonian forests (Fearnside 2022). Searching for ways to reconcile productive activities with forest conservation and maintenance of their immeasurable environmental services, as well as provision of livelihood for the many people who live in them are at the forefront of research and political debate and decision making. The solutions point to the adoption of economic models based on technology, innovation and sustainability under a framework of a conscientious and strategic use of the forest assets and of their biodiversity (Silva et al. 2022).

The non-timber forest products have a determining role in this ecologically sustainable forest management. Tree barks have great economic potential due to their availability, either as a residue from wood industry as well as the possibility of a bark-only directed exploitation along the tree’s life therefore allowing continuous and sustainable management of the species. Barks have a complex and richly diverse structure and chemical composition. The extractives of barks i.e. non-structural components that are soluble, include many chemical classes and compounds, with numerous bioactive molecules, of potential or already current application in pharmacology, nutraceutics, cosmetics or in chemical processes (Ajao et al. 2021). Tannins are an example of a well-established commercial use of barks (Borrega et al. 2022).

After removal of the extractives, the residual bark is suitable for use in the production of new products e.g. in composites, or may undergo a deconstruction process of cell wall components targeted to lignin or polysaccharides derived chemicals, allowing a full biomass resource use and maximizing the economic benefits associated with its sustainable management. Bark-based refineries have therefore been proposed, with different approaches to the valorisation of the structural components lignin, cellulose and hemicelluloses, including the biochemical and thermochemical platforms, although it has been stressed that the diversity of tree barks requires a species’ targeted characterization at structural and chemical levels allowing to design the specific conversion pathways (Mota et al. 2021a; Neiva et al. 2018; Şen and Pereira 2021; Vangeel et al. 2023). There are several recent examples of bark characterization of different species including some from the Amazon (Araujo et al. 2020; Carmo et al. 2016a,b,c; Mota et al. 2021a,b).

The Amazon rainforest tree species Byrsonima spicata (Cav.) DC., Croton matourensis Aubl., Myrcia splendens (Sw.) DC., Tapirira guianensis Aubl., and Vismia guianensis (Aubl.) Choisy are amongst those whose bark phytochemical potential has not been fully characterised and explored.

The species B. spicata is popularly known as “Murici da mata” and belongs to the family Malpighiaceae. It is a native tree that can reach heights of up to 25 m, often found in the Brazilian biomes of the Amazon and Cerrado, predominantly in upland forests, igapó, ciliary, or gallery forests (Francener 2020).

The species C. matourensis, known as “muravuvuia”, “orelha de burro”, or “sangrad’água”, belongs to the Euphorbiaceae family, and is widely distributed in the Amazon rainforest and in some regions of Central America (Lima et al. 2018). It is used to produce firewood and beams, in addition to applications in traditional medicine (Batista 2005).

Myrcia splendens, of the Myrtaceae family, is an arboreal species known as “guamirim” or “cumatê” that is distributed across all Brazilian states and frequently found in areas of secondary vegetation and terra firme forests (Santos et al. 2020). Cumatê trees can reach more than 3 m in height and are one of the native species recommended for recovering degraded areas, as they grow quickly and have food, craft, timber, honey, ornamental and tannic value (Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation 2025).

The species T. guianensis, known as “tatapiririca, tapiririca or tatapirica” in the state of Pará, belongs to the Anacardiaceae family. It has a wide distribution, with occurrences recorded in all the states of the Brazilian Amazon, especially in secondary formations, riparian forests and dryland forests (Silva-Luz et al. 2023). It is a tree that can reach adult dimensions of around 30 m in height and 80 cm in diameter. It is of considerable economic importance due to its various timber and non-timber uses, and is suitable for cover plantations in degraded areas, as it tolerates mainly humid environments, has a high seed germination rate (>80 %) and rapid seedling growth in the field (between 30 and 100 cm year−1) (Carvalho 2006).

Vismia guianensis, commonly known as “lacre”, belongs to the Hypericaceae family and is prevalently found in the Brazilian biomes of the Amazon, Caatinga, Cerrado, and Atlantic Forest (Vogel Ely et al. 2023). In the Brazilian Amazon, its occurrence is particularly notable in secondary forests and in agricultural areas that have been left abandoned (Silvestre et al. 2012).

These species are commonly found in secondary forests in northern Brazil, and their barks can be valued as a sustainable economic asset in community forest management, thereby reconciling income generation with species conservation. Thus, in this study, the bark of these five species was subjected to detailed anatomical description of phloem and periderm, including histochemical tests, and chemical composition characterization including determination of ash composition, lignin, and tannins content. The main objective of the study was to deepen the knowledge about these species and to evaluate the potential of their barks in the context of valorisation and multiple uses of macromolecules and bioproducts from the Amazon Forest.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bark collection

The bark was collected from standing trees by carefully removing two small opposing strips with dimensions of approximately 10 cm wide and 40 cm length, at about breast height. Care was taken to avoid damage to the plants, such as lesions to the vascular cambium and wood. Botanical materials for species identification were obtained from the IAN Herbarium of Embrapa Eastern Amazonia in Belém, Pará, Brazil. The bark samples were dried in the open air. The sequence of bark collection procedures can be observed in Figure 1.

Collection procedures. (a) Measurement of the circumference and plating (arrow) of the trees for botanical identification; (b) removal of bark; (c) drying of the bark in open air. The persons shown have agreed to have their photos published in Holzforschung.

The barks of B. spicata (Cav.) DC. and T. guianensis Aubl. were collected from 10 trees of each species, with a mean diameter of 1.30 m from the ground of 29.5 ± 7.9 and 39.6 ± 9.3 cm and mean total height of 10.6 ± 1.5 and 25.6 ± 3.2 m, respectively, both in a forest fragment of approximately 25 years of age, located at the Federal Rural University of Amazonia, in Belém do Pará, Brazil.

Croton matourensis Aubl., M. splendens (Sw.) DC. and V. guianensis (Aubl.) Choisy trees were found in a fragment of secondary forest of approximately 40 years of age in the municipality of São João da Ponta, northeast of the state of Pará, Brazil. The bark was removed from six trees of each of the species C. matourensis and V. guianensis, with mean diameter of 16.0 ± 4.1 and 7.2 ± 1.2 cm and height of 13.2 ± 3.1 m and 8.0 ± 0.8 m, respectively. For M. splendens, the bark was removed from 10 trees with mean diameter of 10.9 ± 2.6 cm and height of 9.6 ± 3.1 m.

2.2 Anatomical characterization of the bark

Samples of the bark of six individuals of each species were treated with polyethylene glycol (PEG) 1,500 (Quilhó et al. 2000), and Sections 16–20 μm thick in the transverse and longitudinal planes were obtained using a Leica SM 2000 sliding microtome (Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). The sections were washed with sodium hypochlorite (10 %) and deionized water. Double staining was performed with chrysoidine (1 %) and Astra blue (1 %), followed by dehydration in an increasing series of 20, 30, 50, 80 and 100 % ethanol and passage in a gradual solution of ethanol/sodium acetate butyl (3:1, 1:1, 1:3 and 100 % butyl acetate) (Araujo et al. 2020). Entellan resin was used to assemble the slides. For each individual, 30 measurements of the diameter of the tube elements (transversal plane) and quantification of the number of cells and row of rays (tangential plane) were obtained.

Small bark chips were removed near the conducting phloem and were macerated in a 1:1 (v/v) solution of acetic acid and hydrogen peroxide at 60 °C for approximately 48 h (Franklin 1945) and then washed and stained. Measurements were taken of the length of the tube elements and the thickness and length of the fibres. A total of 180 measurements were taken for the anatomical parameters for each species using WinCELL-PRO software, and mean values and standard deviations were reported. The fibres of C. matourensis and V. guianensis are very long, so the images were captured with a 1.25× objective, and when they were curved, the measurements were taken in parts and then added together.

The anatomical preparations were observed under an optical microscope Olympus BX41TF (Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan) with a Pixelink PL-A662 (Rochester, NY, USA) digital camera. Images of the transverse and longitudinal sections were acquired under a microscope Nikon Eclipse E100 (Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan) with an Olympus CX31 camera (Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan). The description was performed according to the International Association of Wood Anatomists (IAWA) list of microscopic characteristics (Angyalossy et al. 2016).

2.3 Histochemistry

Sixteen-micrometre-thick sections of the transverse plane of the bark pieces were cut with a Leica SM 2000 slide microtome (Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). The sections were subjected to histochemical staining to verify the presence of phenolic compounds, alkaloids, starch and lipids. A solution of ferric chloride (10 %) was used to detect the presence of phenolic compounds that react in black or brown colour (Johansen 1940). Wagner’s reagents (Svendsen and Verpoorte 1983) and Lugol (Johansen 1940) were used to observe the possible presence of alkaloids and starch, respectively. Sudan IV was used to detect the presence of lipids (Pearse and Anthony 1980).

2.4 Chemical characterization of the bark

The bark pieces were broken using a hammer mill and sieved, using for analysis the particle size fractions that passed the 40 mesh but were retained in the 60 mesh sieve. Composite samples were prepared by mixing the ground bark of all individuals of each species. The chemical analyses included determination of total extractives, suberin, lignin and ash, and was made in triplicate replications.

The extractive content was determined in bark samples of approximately 2 g (dry basis) according to TAPPI standard T 204 om-07 (2007). Successive extractions were performed using dichloromethane (6 h), ethanol (16 h) and water (16 h) as solvents in a Soxhlet reflux system. Extractive-free bark was used in duplicate to determine the suberin content, according to the method by (Pereira 1988), in which 1.5 g samples (dry basis) were reacted in 100 mL of 50 mM sodium methoxide solution for 3 h under reflux on a heating mantle and then reheated in a new solution for another 15 min after boiling.

Insoluble lignin in acid was quantified in the samples resulting from the suberin analysis, following TAPPI standard T 222 om-21 (2021), with some modifications. Samples of 0.35 g (dry basis) were added to 3 mL of 72 % sulphuric acid solution at 30 °C for 1 h. The protocol modifications included heating in a water bath placed on a heated plate with constant magnetic stirring. The acid-soluble lignin (TAPPI UM-250 1991) was determined from the resulting filtered material by reading the absorbance at 205 nm in a Shimadzu UV-1601 spectrophotometer (Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan). To determine the ash content, 2 g of bark (dry basis) were incinerated in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 4 h (TAPPI T 211 om-22 2022).

The structural polysaccharides were estimated by the difference in the total values of the summative chemistry.

2.5 Quantification of tannins

Tannic extracts were obtained in triplicate using 100 g of ground bark (dry basis) and 1,500 mL of water, liquid/solid ratio 15:1 (v/w), with the addition of 3 % sodium sulphite (Na2SO3) in relation to the dry mass, for 3 h at 70 °C in a water bath (Mori et al. 2003). After extraction, the solutions were filtered through a 1 mm2 colander, 200 mesh sieve, and a sintered glass funnel with porosity one that was coupled to a vacuum pump, respectively. The filtrate was concentrated by evaporation on hot plates at 70 °C until it reached a volume of 150 mL, the mass was determined, and then stored in glass containers in a refrigerated environment.

Solids content (SC) were determined by oven drying of 20 mL aliquots of the extract at 103 ± 2 °C until constant mass, and calculated in percent by dividing the dry mass by the wet mass of the extract. The total solids yield (TSY) was calculated in percent by multiplying the mean value of SC by the mass of the concentrated extract.

The yield of tannins was determined using the Stiasny index (SI), which quantifies the tannic precipitate formed by the reaction of polyphenols with formaldehyde in an acid medium. The analysis was performed in duplicate for each extraction using 20 g of concentrated extract, which was mixed with 10 mL of deionized water, 2 mL of 10 N HCl and 4 mL of formaldehyde (37 %, w/w) in a 250 mL flat-bottomed flask and then heated to reflux for 35 min from boiling point, as detailed in da Silva Araujo et al. (2021). The precipitate formed was filtered through a glass crucible with porosity two and dried at 103 ± 3 °C in a circulating air oven until reaching a constant mass. The SI (%) was calculated in percent by dividing the dry mass of the tannin-formaldehyde precipitate by the dry mass of solids of the extract. The tannin yield was calculated by multiplying the total solid yield (TSY) of the extract by the Stiasny index (SI), and then dividing by 100 (da Silva Araujo et al. 2021).

2.6 Analysis of bark minerals

A sample of approximately 40 g of bark, with a particle size of 40–60 mesh, was used for analysis of the mineral constituents. The macronutrients N, P, K, Ca, Mg, and S and micronutrients Mn, Zn, B, Cu and Fe were quantified with an optical emission spectrometer with inductively coupled plasma (ICP-OES, Spectro Analytical Instruments, Kleve, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany).

2.7 Statistical analyses

The data for anatomical (fibres and tube elements dimensions) and chemical (extractives, suberin, lignin, ash, and tannins) features are presented as mean values followed by standard deviation. The tannin yield data were analysed using analysis of variance and, when statistically significant differences were identified, the means were compared using the Scott–Knott test at a significance level of 5 %. Statistical analyses were performed utilizing Sisvar software, version (5.6).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Anatomical structure of the bark

The external anatomical structure of the barks is depicted in Figure 2 showing the rhytidome and periderm development for the five species, and the features of rhytidome, phellem and phelloderm are summarized in Table 1.

![Figure 2:

Periderms of Amazonian species seen in cross-section. (A1–2) Byrsonima spicata, (B1–2) Croton matourensis, (C1–2) Myrcia splendens, (D1–2) Tapirira guianensis and (E1–2) Vismia guianensis. Phellem [Pl], phelloids [Fe], phelloderm [Pd], phellogen [Fg, yellow arrow], periderms [Pe, star], cortex [Cx], rhytidome [Rh], sclereides [S], dead phloem [Dp], cells with content [standard and red arrow], lenticels [*asterisk] and secretory cells [red triangle].](/document/doi/10.1515/hf-2024-0097/asset/graphic/j_hf-2024-0097_fig_002.jpg)

Periderms of Amazonian species seen in cross-section. (A1–2) Byrsonima spicata, (B1–2) Croton matourensis, (C1–2) Myrcia splendens, (D1–2) Tapirira guianensis and (E1–2) Vismia guianensis. Phellem [Pl], phelloids [Fe], phelloderm [Pd], phellogen [Fg, yellow arrow], periderms [Pe, star], cortex [Cx], rhytidome [Rh], sclereides [S], dead phloem [Dp], cells with content [standard and red arrow], lenticels [*asterisk] and secretory cells [red triangle].

Microscopic characteristics of the bark of five Amazonian species.

| Anatomical description | Byrsonima spicata | Croton matourensis | Myrcia splendens | Tapirira guianensis | Vismia guianensis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhytidome | Present | Present | Present | Present | Present |

| Periderm | 1–2 periderms | 2–7 periderms | 2–3 periderms | 3–4 periderms | 2–3 periderms |

| Dead phloem | Absent | Present | Absent | Present | Absent |

| Disposition/arrangement of the periderms | (−) | Concentric | (−) | Concentric | (−) |

| (Figure 2A1 and 2) | (Figure 2B1 and 2) | (Figure 2C1 and 2) | (Figure 2D1 and 2) | (Figure 2E1 and 2) | |

| Phellem (Pl): types of cells | Square to rectangular shaped cells; cells with U-shaped wall thickenings (Figure 2A2) | Rectangular to oval-shaped cells; uniformly thickened cell walls (Figure 2B1) | Rectangular to oval-shaped cells; uniformly thickened cell walls (Figure 2C2) | Cells oval in shape; cell walls uniformly thin (Figure 2D1) | Square to rectangular shaped cells; thin cell walls, sometimes thick and lignified (Figure 2E1) |

| Phelloderm (Pd): types of cells and thickness | Square to rectangular shaped cells (Figure 2A2); thick (3–4 cell layers) | Rectangular to oval-shaped cells (Figure 2B1); thin (2–3 cell layers) | Oval to round-shaped cells (Figure 2C2); thin (2–3 cell layers) | Rectangular to oval-shaped cells (Figure 2D1); thick (3–5 cell layers) | Square to rectangular shaped cells (Figure 2E1); thin (1–2 cell layers) |

| Sieve-tube elements: grouping and distribution in the conducting phloem; length (L) and diameter (D) in μm | In small groups (Figure 5D); L = 640.0 ± 0.04, D = 24.4 ± 1.0 | Solitary (Figure 3G); L = 644.9 ± 0.05, D = 23.0 ± 1.4 | Multiple in radial rows (Figure 6A and B); L = 526.7 ± 25, D = 19.1 ± 1.7 | In tangential bands (Figure 4B and C); L = 605.3 ± 0.02, D = 20.2 ± 0.8 | Multiple in radial rows (Figure 7D); L = 576.2 ± 0.04, D = 20.0 ± 2.9 |

| Companion cells: quantity | Two companion cells on opposite sides of the sieve-tube element (Figure 5D) | One companion cell per sieve-tube element (Figure 3G) | One companion cell per sieve-tube element (Figure 6B) | Two companion cells on opposite sides of the sieve-tube element (Figure 4C) | Two companion cells on opposite sides of the sieve-tube element (Figure 7D) |

| Axial parenchyma: distribution on the phloem | Diffuse and diffuse-in-aggregates discontinuous (Figure 5A–D) | Predominantly diffuse and solitary in the phloem (Figure 3G) | Continuous radial bands, sometimes expanded, in lateral alternance with sieve-tube elements (Figure 6B) | Constitutes the ground tissue (Figure 4B and C) | Continuous radial bands, in lateral alternance with sieve-tube elements (Figure 7D) |

| Fibres: length (L) and thickness (T) in μm | L = 1,877.4 ± 0.2; T = 21.4 ± 3.5 | L = 5,644.6 ± 0.3; T = 9.9 ± 2.1 | L = 1,126.8 ± 4; T = 7.1 ± 0.8 | L = 1,437.8 ± 0.1; T = 14.7 ± 1.5 | L = 1,208.1 ± 0.04; T = 14.3 ± 1.2 |

| Rays: ray width in cell number | Rays 2–4 cells wide (Figure 5C) | Rays 1–3 cells wide (Figure 3H) | Rays 1–3 cells wide (Figure 6D) | Rays 2–4 cells wide (Figure 4E) | Rays 1–3 cells wide (Figure 7F) |

-

(−), absent.

The rhytidome is in all the species characterized by semicontinuous layers of phellem and phelloderm originating from the phellogen, which appeared as a thin layer of radially flattened rectangular cells (Figure 2A–E). C. matourensis and T. guianensis were found to have a substantial rhytidome with several well developed sequential periderms separated by dead phloem layers forming a concentric rhytidome pattern (Figure 2B1 and 2, D1 and 2).

The phellem showed the typical radial arrangement of the cells originating from the phellogen and a compact arrangement without intercellular voids. The phellem cells were often thick-walled, with contents in the lumen (Figure 2A–E), sometimes in the process of sclerification or with alternating clusters of sclereids (Figure 2 A2, C1 and E2). The phellem was partially composed of phelloid cells; that is, cells that are not suberized and that may have thick walls that can differentiate into sclereids as common in some species (Esau 1974). The phelloderms were predominantly thin, with 1–3 layers of thin-walled cells, with a shape that varied among the species. The overall characteristics of the periderms are in line with descriptions made for other species e.g. Quercus suber (Graça and Pereira 2004), Quercus cerris (Sen et al. 2011).

Lenticels lacking setation (homogeneous) were observed in B. spicata (Figure 2A) and stratified (heterogeneous) lenticels were observed in M. splendens (Figure 2C). Lenticels are regions that have filling lenticular tissues that, in contrast to the phellem, have a loose arrangement of cells with intercellular spaces, allowing air to enter the tissue and chemically are no suberized (Apezzato-da-Glória and Carmello-Guerreiro 2006).

Dead phloem was observed between the sequential periderms of C. matourensis and T. guianensis (Figures 2 B2 and D2). Below the innermost periderm of B. spicata, M. splendens and T. guianensis, clusters of scattered sclereids were observed to alternate with cortical cells, which made for the transition to the phloem (Figure 2A–C and D).

Figures 3–7 show microscopic sections of phloem in transverse, radial and tangential sections as well as dissociated elements for each of the five species, and Table 1 includes their qualitative and quantitative features of sieve tube elements, companion cells, axial parenchyma, fibres, and rays.

![Figure 3:

Bark sections of Croton matourensis. (A) Extension of the transverse plane, showing periderms [Pe], cortex [Cx], ray [R], fibres [F], conductive and nonconductive phloem [in yellow delimited zone], ray dilation towards the periderm and secretory cells [red triangle] and laticifer tubes [*, zone delimited in orange]; (B, C) delimited zone in the cortex, showing laticifer tubes with and without excretory contents [*] and crystalline sand [arrow]; (D) tube element [st]; (E) fibres [F], demarcated zone showing the cell wall; (F) radial plane, white arrow pointing to drusen crystals in the radius, crystalline sand [green arrow] and axial aspect of the laticiferous tubes [*]; (G) tube element [st], fibres [F], axial parenchyma [P], conductive [cp] and nonconductive [np] phloem, arrow showing companion cells and secretory cells [red triangle]; (H) tangential plane showing the radius [R].](/document/doi/10.1515/hf-2024-0097/asset/graphic/j_hf-2024-0097_fig_003.jpg)

Bark sections of Croton matourensis. (A) Extension of the transverse plane, showing periderms [Pe], cortex [Cx], ray [R], fibres [F], conductive and nonconductive phloem [in yellow delimited zone], ray dilation towards the periderm and secretory cells [red triangle] and laticifer tubes [*, zone delimited in orange]; (B, C) delimited zone in the cortex, showing laticifer tubes with and without excretory contents [*] and crystalline sand [arrow]; (D) tube element [st]; (E) fibres [F], demarcated zone showing the cell wall; (F) radial plane, white arrow pointing to drusen crystals in the radius, crystalline sand [green arrow] and axial aspect of the laticiferous tubes [*]; (G) tube element [st], fibres [F], axial parenchyma [P], conductive [cp] and nonconductive [np] phloem, arrow showing companion cells and secretory cells [red triangle]; (H) tangential plane showing the radius [R].

![Figure 4:

Anatomical aspects of Tapirira guianensis bark. (A) Extension of the transverse plane, showing fibre bands [Fb], conductive phloem [cp], wavy and dilated rays in the shape of a wedge due to anticlinal divisions and cell expansion [R], resin channels [red star] and delimited zones; (B) nonconductive phloem, showing fully collapsed tube element [st], alternating with noncollapsed axial parenchyma cells, crystals [arrow] in bands adjacent to fibres [Fb] and resin channels [red star]; (C) conductive phloem with tube element [st] together with companion cells [orange arrow]; (D) radial plane, arrow pointing to the prismatic crystals and axial aspect of the tannery tube [triangle]; (E) tangential plane showing the radius [R] and crystals [arrow]; (F) tangential plane with radial channels [orange star]; (G) fibres [F]; (H) tube element [st].](/document/doi/10.1515/hf-2024-0097/asset/graphic/j_hf-2024-0097_fig_004.jpg)

Anatomical aspects of Tapirira guianensis bark. (A) Extension of the transverse plane, showing fibre bands [Fb], conductive phloem [cp], wavy and dilated rays in the shape of a wedge due to anticlinal divisions and cell expansion [R], resin channels [red star] and delimited zones; (B) nonconductive phloem, showing fully collapsed tube element [st], alternating with noncollapsed axial parenchyma cells, crystals [arrow] in bands adjacent to fibres [Fb] and resin channels [red star]; (C) conductive phloem with tube element [st] together with companion cells [orange arrow]; (D) radial plane, arrow pointing to the prismatic crystals and axial aspect of the tannery tube [triangle]; (E) tangential plane showing the radius [R] and crystals [arrow]; (F) tangential plane with radial channels [orange star]; (G) fibres [F]; (H) tube element [st].

![Figure 5:

Anatomical aspects of the Byrsonima spicata bark. (A) Conductive phloem with prismatic crystals [white arrow] and contents [red arrow] adhered in sclereid-fibre clusters, and demarcated zone enlarged in detail; (B) tube element [st] with companion cells [orange arrow], crystals [white arrow] and axial parenchyma [P] and radius [R]; (C) radial longitudinal section showing ray cells [R] and occurrence of crystalline sand [arrow]; (D) ray cells in tangential section and crystals lined in fibrous zone [arrow]; (E) tube element [st]; (F) fibres [F] with enlarged zone showing the cell wall and sclereid fibres [Ft].](/document/doi/10.1515/hf-2024-0097/asset/graphic/j_hf-2024-0097_fig_005.jpg)

Anatomical aspects of the Byrsonima spicata bark. (A) Conductive phloem with prismatic crystals [white arrow] and contents [red arrow] adhered in sclereid-fibre clusters, and demarcated zone enlarged in detail; (B) tube element [st] with companion cells [orange arrow], crystals [white arrow] and axial parenchyma [P] and radius [R]; (C) radial longitudinal section showing ray cells [R] and occurrence of crystalline sand [arrow]; (D) ray cells in tangential section and crystals lined in fibrous zone [arrow]; (E) tube element [st]; (F) fibres [F] with enlarged zone showing the cell wall and sclereid fibres [Ft].

![Figure 6:

Anatomical appearance of the bark of Myrcia splendens. (A) Wedge-shaped ray dilatation tissue [*], ray [R] and sclereids [S]; (B) conductive phloem, with expanded parenchyma cells [*] and arrow pointing to the companion cells of the tube element; (C) longitudinal radial section showing axial parenchyma cells [*], fibres [F], radius [R] and cells with contents [arrow]; (D, E) longitudinal tangential section showing radius [R] and crystals in the cells axial parenchyma [arrow]; (F) tube element [st] with scalariform sieve plates [arrow]; (G) fibres [F] and sclereid fibres [arrow]; (H) fibres [F] and astrosclereids [arrow].](/document/doi/10.1515/hf-2024-0097/asset/graphic/j_hf-2024-0097_fig_006.jpg)

Anatomical appearance of the bark of Myrcia splendens. (A) Wedge-shaped ray dilatation tissue [*], ray [R] and sclereids [S]; (B) conductive phloem, with expanded parenchyma cells [*] and arrow pointing to the companion cells of the tube element; (C) longitudinal radial section showing axial parenchyma cells [*], fibres [F], radius [R] and cells with contents [arrow]; (D, E) longitudinal tangential section showing radius [R] and crystals in the cells axial parenchyma [arrow]; (F) tube element [st] with scalariform sieve plates [arrow]; (G) fibres [F] and sclereid fibres [arrow]; (H) fibres [F] and astrosclereids [arrow].

![Figure 7:

Anatomical aspect of the bark of Vismia guianensis. (A) Extension of the transverse plane, showing wedge-shaped ray dilatation tissue [R] and tangential cord formed by secretory channels in demarcated areas; (B) secretory cells [red triangle] and (C) secretory channels containing exudates; (D) conductive phloem, with expanded parenchyma cells [*], arrow pointing to companion cells of the tube element [st] and secretory cells [red triangle]; (E) radial longitudinal section showing cells of radius [R], with the occurrence of crystalline sand [green arrow] and prismatic crystals in rows [white arrow]; (F) tangential longitudinal section, showing radius [R] and crystals in the axial parenchyma cells [arrow]; (G) fibres [F]; (H) tube element [st, arrow].](/document/doi/10.1515/hf-2024-0097/asset/graphic/j_hf-2024-0097_fig_007.jpg)

Anatomical aspect of the bark of Vismia guianensis. (A) Extension of the transverse plane, showing wedge-shaped ray dilatation tissue [R] and tangential cord formed by secretory channels in demarcated areas; (B) secretory cells [red triangle] and (C) secretory channels containing exudates; (D) conductive phloem, with expanded parenchyma cells [*], arrow pointing to companion cells of the tube element [st] and secretory cells [red triangle]; (E) radial longitudinal section showing cells of radius [R], with the occurrence of crystalline sand [green arrow] and prismatic crystals in rows [white arrow]; (F) tangential longitudinal section, showing radius [R] and crystals in the axial parenchyma cells [arrow]; (G) fibres [F]; (H) tube element [st, arrow].

The phloem includes the inner portion adjacent to the vascular cambium, called conductive phloem, and the outer nonconductive phloem. The transition between the two phloem types was abrupt in C. matourensis (Figure 3A) and T. guianensis (Figure 4A) and gradual in the other species (Figures 6A and 7A). In the conducting phloem, the sieve tube elements were turgid and were accompanied by small companion cells. Among the species, the average values of the tangential diameter of the sieve tube elements ranged from 19.1 to 24.4 μm, and the average length from 526.7 to 644.9 μm (Table 1).

The rays in the cross section were wide and dilated in a wedge shape towards the periderm. In T. guianensis, the rays were intensely dilated and wavy (Figure 4A–C). The tree species had predominantly heterogeneous rays, were multiseriate and were not storied when observed in longitudinal planes (Table 1).

The fibres had an average length in the range of 1,172.6 to 5,644.6 μm among the species, with an average wall thickness of 7.1–21.4 μm (Table 1). The bark of B. spicata and T. guianensis were very fibrous, and agglomerates and broad bands of fibres were observed along the phloem (Figures 4A and 5A).

Sclereids were observed in all the species, and especially in M. splendens, where the astrosclereid type was found (Figure 6H). Mineral inclusions were observed in all the species. In M. splendens and V. guianensis, prismatic calcium oxalate crystals occurred in series in the axial parenchyma cells (Figures 6E and 7E–F), while in T. guianensis and B. spicata the same crystals occurred mainly in rows adjacent to the fibres (Figures 4D–E and 5C–D). Crystals of the crystalline sand druse-type were observed in the parenchyma cells (Figure 3B–F), and also in B. spicata and V. guianensis (Figures 5C and 7E).

Secretory structures were observed in C. matourensis, T. guianensis and V. guianensis. In C. matourensis, in the conducting and nonconductive phloem there were secretory cells, while in the cortex laticiferous tubes with visible content were observed (Figure 3A–C). In T. guianensis, secretory cells occurred throughout the phloem and cortex, and the resin canals had axial and radial development, and were surrounded by epithelial cells and tanniferous tubes (Figure 4A–F). In V. guianensis, secretory cells were observed throughout the entire tissue, and secretory channels containing exudates were arranged to form a uniseriate tangential cord in the cortex region and a biseriate cord in the phloem (Figure 7A–C). The bark of recently handled C. matourensis and V. guianensis exuded a pleasant odour and a sticky reddish and orangish substance, respectively.

3.2 Histochemistry

The histochemical analysis indicated the presence of phenolic compounds and lipids in the periderms and phloem of the bark of all the species (Table 2). Alkaloids were detected only in the periderm of M. splendens and V. guianensis, and starch was detected especially in parenchyma cells of the phloem and cortex of C. matourensis and V. guianensis.

Histochemical tests on the bark of Byrsonima spicata (Bs), Croton matourensis (Cm), Myrcia splendens (Ms), Tapirira guianensis (Tg) and Vismia guianensis (Vg).

| Test | Tissues | Species | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bs | Cm | Ms | Tg | Vg | ||

| Phenolic compounds | R | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Ph | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Alkaloids | R | Nc | Nc | + | − | + |

| Ph | Nc | Nc | − | − | − | |

| Starch | R | − | − | Nc | – | − |

| Ph | − | ++ | − | − | ++ | |

| Lipids | R | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ph | + | + | + | + | + | |

-

R, rhytidome; Ph, phloem. Reaction intensity: (+) present; (++) intensely present; (Nc) inconclusive and (−) absent.

Phenolic compounds stood out in their expressive presence in these barks. The class of phenolic compounds includes flavonoids, phenolic acids and tannins, which are synthesized in plant secondary metabolism, mainly to protect against biotic and abiotic factors that may hinder plant development (Sharma et al. 2019). Phenolics are present in most barks as well as in other biomass e.g. in nut shells or seeds, and have been often researched for their antioxidant, bioactive and chemical functional properties that suggest applications as natural additives in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic and food industries or for production of adhesives (Castro et al. 2018; Sillero et al. 2019).

The results obtained by the anatomical and histochemical observations showed that the phenolic compounds were predominantly concentrated in the cells of the periderm, as illustrated in Figure 8. This has interesting practical implications when the goal is a contribution to the sustainable utilization and management of trees because the periderm or periderms are the outermost tissue of the bark and have rapid tissue recovery there by facilitating material collection and extraction of potential high-value chemicals.

![Figure 8:

Histochemical tests for the detection of phenolic compounds in the barks. (A1 and A2) Byrsonima spicata; (B1 and B2) Croton matourensis; (C1 and C2) Myrcia splendens; (D1 and D2) Tapirira guianensis; (E1 and E2) Vismia guianensis. A1–E1 [control], A2–E2 [ferric chloride test], stars [examples of sites with positive reaction]. Scales: 800 µm (A1 and A2), 400 µm (B1–E2). Magnification: 4× (A1 and A2), 10× (B1–E2).](/document/doi/10.1515/hf-2024-0097/asset/graphic/j_hf-2024-0097_fig_008.jpg)

Histochemical tests for the detection of phenolic compounds in the barks. (A1 and A2) Byrsonima spicata; (B1 and B2) Croton matourensis; (C1 and C2) Myrcia splendens; (D1 and D2) Tapirira guianensis; (E1 and E2) Vismia guianensis. A1–E1 [control], A2–E2 [ferric chloride test], stars [examples of sites with positive reaction]. Scales: 800 µm (A1 and A2), 400 µm (B1–E2). Magnification: 4× (A1 and A2), 10× (B1–E2).

3.3 Chemical composition of the bark

The summative chemical composition of the barks is presented in Table 3. These five barks stand out by their high content in extractives that ranged from 29.4 to 46.2 % in C. matourensis and M. splendens respectively. The chemical composition of extractives showed a small amount of lipophilic compounds from minute contents in the barks of B. spicata and M. splendens to moderate contents in C. matourensis and V. guianensis (8.5 and 8.2 % respectively). For all the species, the largest fraction of the bark extractives was of polar compounds soluble in ethanol and water, which together corresponded to 46.1 % in M. splendens, 38.1 % in B. spicata, 30.0 % in V. guianensis, 28.0 % in T. guianensis and 20.9 % in C. matourensis. The high phenolic content was also shown by the histochemical analysis where the ferric chloride staining revealed conspicuous dark colouring (Figure 8).

Summary chemical composition (% of bark dry mass) of Amazonian species.

| Compounds (%) | Byrsonima spicata | Croton matourensis | Myrcia splendens | Tapirira guianensis | Vismia guianensis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total extractives | 38.6 ± 0.7 | 29.3 ± 2.9 | 46.2 ± 1.1 | 30.2 ± 4.1 | 38.2 ± 0.5 |

| Dichloromethane | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 8.2 ± 0.6 |

| Ethanol | 23.6 ± 0.1 | 10.5 ± 1.3 | 41.7 ± 1.3 | 19.6 ± 1.3 | 18.3 ± 3.6 |

| Water | 14.5 ± 0.3 | 10.4 ± 1.5 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 8.4 ± 2.6 | 11.7 ± 2.6 |

| Suberin | 0.4 ± 0.01 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.01 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

| Total lignin | 33.4 ± 0.4 | 29.0 ± 2.6 | 23.6 ± 0.8 | 32.5 ± 0.6 | 19.0 ± 0.2 |

| Klason lignin | 31.5 ± 0.4 | 26.5 ± 2.1 | 21.1 ± 0.8 | 29.8 ± 0.5 | 15.4 ± 0.8 |

| Soluble lignin | 1.9 ± 0.01 | 2.5 ± 0.02 | 2.5 ± 0.01 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.5 |

| Ash | 2.2 ± 0.04 | 3.8 ± 0.002 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.02 |

| Polysaccharidesa | 25.4 | 36.2 | 26.7 | 29.0 | 33.6 |

-

aDetermined by difference. Values are presented as the population mean ± standard deviation.

Polar extractives generally prevail in barks and are represented mainly by phenolic compounds, including polyphenols such as tannins. In this study, the barks of all the species had higher or similar polar extractives content compared to that of other Amazonian species, such as Goupia glabra (21.2 % (Carmo et al. 2016c)), Copaifera langsdorffii (19.2 % (Carmo et al. 2016a)), Albizia niopoides (22.2 % (Carmo et al. 2016b)), Astronium lecointei (16.1 % (Mota et al. 2021a)), Tachigali guianensis (16.5 % and Tachigali glauca 14.2 % (Mota et al. 2021b)).

Suberin content was overall low (Table 3), with lower content in B. spicata (0.4 %) and higher content in T. guianensis (3.4 %) and V. guianensis (3.2 %). These findings clearly accord with the anatomical observations showing thin periderms and phellem (Figure 2) often with the presence of phelloid cells (Figure 2A2) and with lignified walls (Table 1). In fact suberin is a cell wall structural component that is specific to the phellem (cork) cells and appears with high content in cork-rich barks (Leite and Pereira 2017). The paradigm of a cork species is Q. suber, from which the commercial cork is obtained and processed into world known cork products (Pereira 2007) but a few species from the Brazilian cerrado were shown to have thick cork layers e.g. Plathymenia reticulata (Mota et al. 2016) and Agonandra brasiliensis (Silva et al. 2021).

The total lignin content ranged from 19.0 to 33.4 % (Table 3). This chemical component confers rigidity to the cellular elements, being present in bark mainly in the walls of fibres and sclereids. This explains the greater presence of lignin in the bark of B. spicata (33.4 %) which presented a structural arrangement formed by several clusters of sclerenchyma cells (Figure 5A) and phelloid cells in the periderm (Figure 2A2). With the second highest lignin content, T. guianensis (32.5 %) has broad fibre bands along the phloem (Figure 4A).

Polysaccharide content, estimated by difference from the total summative composition, ranged from 25.4 % in B. spicata to the highest value in C. matourensis (36.2 %), as shown in Table 3. Polysaccharides are present in barks in much lower content than in wood, with the highest values usually associated to fibre-rich barks, such as in Eucalyptus globulus (Neiva et al. 2018) to Eucalyptus urophylla hybrids (Sartori et al. 2022).

3.4 Bark tannin yield

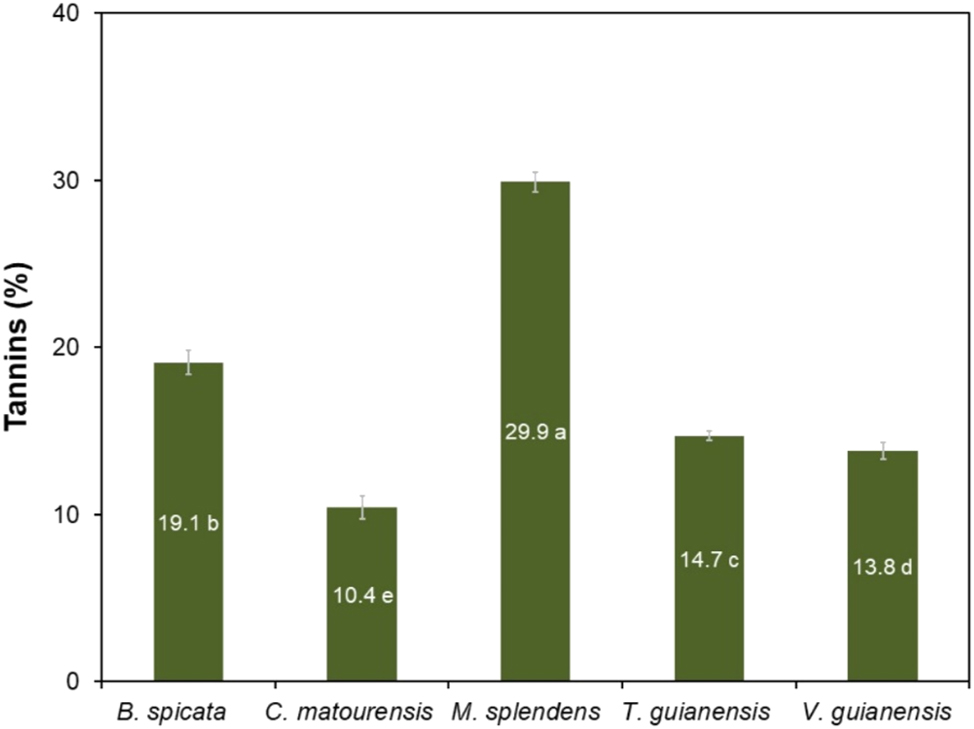

The yields obtained for the extraction of tannins from the bark of these five Amazonian species are shown in Figure 9. The tannin yield ranged from 10.4 to 29.9 %, with the highest values obtained from the bark of M. splendens (29.9 %), B. spicata (19.1 %) and T. guianensis (14.2 %). According to their chemical structure, tannins are divided in hydrolysable and condensed tannins, the former being oligomers composed of carbohydrate-polyphenol units, while condensed tannins are made up of oligomers of flavonoid units (Pizzi 2021). Condensed tannins and their flavonoid precursors are widely distributed in nature but are particularly present in high concentrations in the wood and bark of several tree species (Pizzi 2008, 2021).

Yield of tannins in the bark of Amazonian species. Means followed by the same letter do not differ from each other by the Scott–Knott test at 5 % significance.

Myrcia splendens stood out as a potential source for tannin extraction, and its yields were higher than those extracted by a sodium sulfite solution from the bark of, Anadenanthera colubrina (19.2 %), a species abundant in the northeast region of Brazil, and that is traditionally used in leather tanning (Paes et al. 2013). The content of condensed tannins in M. splendens was also close to that of the bark of red cumate, Myrcia eximia (32.6 %) (da Silva Araujo et al. 2021), a species from Amazonia that was recognized as potential source of tannins. M. splendens had the same tannin content as black wattle, Acacia mearnsii (30.0 %), a species of Australian origin cultivated in southern Brazil for commercial extraction of tannins for various industrial purposes (Mangrich et al. 2014).

3.5 Inorganic components of the bark

The average ash fractions in the barks ranged from 1.8 to 6.0 %, corresponding respectively to M. splendens and T. guianensis (Table 3). Among the major mineral constituents, calcium occurred in the highest concentration in the bark of T. guianensis (20.6 g kg−1 of bark), representing 61.9 % of the total amount of minerals quantified in the bark, followed by V. guianensis (60 %), B. spicata (45 %) and C. matourensis (40 %), as shown in Table 4. The high calcium content in most of the species was observed in the form of crystals adjacent to the fibres (Figure 4D and E) and cells of parenchyma (Figure 7E). In the bark of M. splendens, nitrogen (5.6 g kg−1 of bark) prevailed, accounting for 46.9 % of the total quantified minerals, followed by calcium (24.3 %) and potassium (15.1 %).

Inorganic components (mg kg−1 of bark) in the bark of Amazonian species.

| Minerals (%) | Byrsonima spicata | Croton matourensis | Myrcia splendens | Tapirira guianensis | Vismia guianensis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (N) | 3,600.0 | 4,200.0 | 5,600.0 | 5,700.0 | 5,700.0 |

| Calcium (Ca) | 8,100.0 | 13,300.0 | 2,900.0 | 20,600.0 | 19,700.0 |

| Potassium (K) | 4,100.0 | 4,200.0 | 1,800.0 | 4,100.0 | 3,900.0 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 1,400.0 | 5,600.0 | 800.0 | 1,200.0 | 1,000.0 |

| Sulphur (S) | 400.0 | 5,200.0 | 600.0 | 1,100.0 | 2,000.0 |

| Phosphor (P) | 300.0 | 300.0 | 100.0 | 400.0 | 200.0 |

| Iron (Fe) | 80.4 | 269.6 | 89.0 | 104.0 | 242.9 |

| Manganese (Mn) | 17.2 | 161.2 | 46.5 | 86.0 | 57.2 |

| Boron (B) | 3.0 | 8.8 | 5.9 | 6.9 | 13.7 |

| Copper (Cu) | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 6.7 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 4.8 | 12.5 | 3.1 | 4.2 | 34.2 |

| Total | 18,008.6 | 33,255.5 | 11,948.4 | 33,306.3 | 32,853.8 |

The micronutrients with the highest contents were iron (80.4–269.6 mg kg−1 of bark) and manganese 17.2–161.2 mg kg−1 of bark) (Table 4). Calcium is usually a major inorganic component of barks including in Amazonian species. For instance, Araujo et al. (2020) reported high contents of Ca (2.9 g kg−1 of bark), N (2.7 g kg−1 of bark), Fe (111.5 mg kg−1 of bark) and Mn (43.5 mg kg−1 of bark) for the bark of the Amazonian M. eximia. The bark of the Myracrodruon urundeuva, occuring in the Brazilian cerrado and caatinga biome, also contains mostly calcium, potassium, nitrogen, iron and manganese (Sousa et al. 2022).

The bark samples of the studied species were found to be an important source of minerals, especially calcium, nitrogen, potassium, and magnesium, which belong to the class of macronutrients with structural functions in living organisms, and also a source of the micronutrients iron and manganese, which are essential in smaller amounts because they have a regulatory function. The high levels of mineral elements suggest that the bark of these species may be a good source of nutrients and useful as plant substrates (Mota et al. 2021a).

3.6 Potential uses of barks

The characterization of the barks of these five Amazonian tree species in terms of chemical composition and anatomical features is the starting point to delineate their valorisation pathways. One first point is the high content in polar extractives (Table 3) that therefore suggests a preliminary extraction step to obtain potentially valuable phenolic and polyphenolic compounds with chemical functionalities and bioactivities. One chemical class with already firmly established and commercial applications are tannins. These phenolic compounds are considered green raw materials and have a wide range of applications including leather tanning, prevention of oxidation reactions in beverages, food and feed for ruminant animals, nutraceuticals, flocculants for water treatment, adsorbents for proteins and antibiotics, mud conditioners for drilling oil wells, suspension of agrochemicals, adhesives for wood bonding, wood preservative treatment and in pharmaceuticals due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and antiviral properties (Ozogul et al. 2025; Shirmohammadli et al. 2018). For instance, the condensed tannins of black wattle (A. mearnsii) are commercially extracted in southern Brazil and subjected to chemically modified for specific uses, mainly in leather tanning, water and industrial effluent treatment, animal nutrition and wood adhesives segments (Mangrich et al. 2014).

Although the content in lipophilic compounds was in general low, for the two species C. matourensis and V. guianensis it amounted to over 6 % which allows to be further considered for extraction if valuable compounds are present e.g. with pharmacological or nutraceutical properties. Certainly, further studies are needed to characterise the composition of theses extracts.

After extraction, the studied residual barks are characterized by low suberin, high lignin and moderate polysaccharides contents (Table 3) and the options for their valorisation may consider either a deconstruction of the cell wall matrix or its full use. A notable alternative to full use is the development of cement-bark composites where the barks provide greater thermal resistance, elasticity and ductility to the composite, and demonstrate potential in civil construction for insulation materials and in non-load bearing building applications (Giannotas et al. 2022). Considering the cell wall chemical components, suberin will not be the target given its low content in spite of its interesting chemical and potential bioactive properties (Correia et al. 2020). A similar reasoning can be made for cellulose and hemicelluloses, knowing that other biomass resources are much richer in polysaccharides. Lignin is quantitatively more interesting, and its depolymerization has potential for high value-added monomers recovery, such as guaiacol, ferulic acid, vanillin, vanillic acid, coumaric acid and syringic acid (Nguyen et al. 2021).

However, a thermochemical pathway for the extracted barks seems more suitable by considering either pyrolysis or biochar production pathways. A recent report on the valorisation of barks within a biorefinery framework proposes extraction and pyrolysis, as well as biochar conversions (Şen and Pereira 2021; Şen et al. 2023).

In a biorefinery context, after the extraction of chemical compounds with higher added value, the residual biomass may also serve as a fertilizer due to its high mineral content (Table 4), therefore making the use of natural resources more efficient and sustainable. Another alternative would be to use the mineral fraction as a reinforcement to improve the quality of tannic adhesives as proposed by Zidanes et al. (2024), who incorporated 5 % rice husk ash into the tannin-based adhesive derived from Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart.) Coville, and noted improvements in the properties of viscosity, pH, gel time and solids content of the reinforced adhesives.

4 Conclusions

This study presents the anatomical and chemical characterization of the bark of five species occurring in the Brazilian Amazon Forest as the starting point to delineate their valorisation pathways: B. spicata, C. matourensis, M. splendens, T. guianensis and V. guianensis. The anatomical structure showed the formation of a rhytidome with successive layers of periderms with small phellem development, thereby leading to reduced contents in suberin.

The barks of the five species showed a significant presence of polar extractives, with particular expression in M. splendens and B. spicata. Tannins could be obtained in high yields, particularly from M. splendens and B. spicata where they are located in the outer portion of the bark. The bark of these species showed high levels of mineral elements with the barks of T. guianensis, V. guianensis and C. matourensis standing out as rich sources of calcium.

The bark composition suggests a valorisation of their high content in polar solubles by extraction to obtain potentially valuable phenolic and polyphenolic compounds with chemical functionalities and bioactivities, including tannins, namely from B. spicata and M. splendens. After extraction, the lignin-rich solid residue is suitable for a thermochemical valorisation, namely by biochar production, while the high nutrient levels make soil amendment an interesting application. The stem bark of these trees is a potential source of by-products with multiple uses, so sustainable management and valorization of the bark can generate local income and contribute to the conservation of these Amazonian species.

Funding source: Brazilian Fund for Biodiversity (FUNBIO)

Award Identifier / Grant number: edition 02/2019

Funding source: Foundation for Research Support of the State of Minas Gerais - FAPEMIG

Acknowledgments

We thank the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Minas Gerais – FAPEMIG, for the support and granting of a doctoral scholarship. To the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq, and to the Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Studies (CAPES; Financing code 001), we are grateful for the supply of equipment. To the postgraduate Program in Biomaterials Engineering (PPGBIOMAT/UFLA). To the postdoctoral Program of the State University of Amapá (Edital 030/2024 - PROPESP/UEAP). We thank Mr. Zacarias Monteiro, a resident of the community of São João da Ponta, PA, for the knowledge shared. We also thank the employees of the IAN Herbarium of Embrapa Amazonia Oriental for the species identification.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. ESA: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation and writing – original draft. GSM: methodology, validation, writing – review and editing. RMA, ULZ, JCC, MSL and CAS: methodology. MGS: resources. HP: validation, writing – review and editing. FAM: resources, supervision, funding acquisition, validation.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This study was funded by the Brazilian Fund for Biodiversity (FUNBIO) in partnership with the Institute of Humanity (HUMANIZE) through the so-called FUNBIO – Conserving the Future grants, edition 02/2019. The Foundation for Research Support of the State of Minas Gerais – FAPEMIG, funded the first author’s doctoral scholarship.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Ajao, O., Benali, M., Faye, A., Li, H., Maillard, D., and Ton-That, M.T. (2021). Multi-product biorefinery system for wood-barks valorization into tannins extracts, lignin-based polyurethane foam and cellulose-based composites: techno-economic evaluation. Ind. Crops Prod. 167: 113435, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113435.Search in Google Scholar

Angyalossy, V., Pace, M.R., Evert, R.F., Marcati, C.R., Oskolski, A.A., Terrazas, T., Kotina, E., Lens, F., Mazzoni-Viveiros, S.C., Angeles, G., et al.. (2016). IAWA list of microscopic bark features. IAWA J. 37: 517–615, https://doi.org/10.1163/22941932-20160151.Search in Google Scholar

Apezzato-da-Glória, B. and Carmello-Guerreiro, S.M. (2006). Anatomia vegetal, 2nd ed. UFV, Viçosa, Brasil.Search in Google Scholar

Araujo, E.S., Mota, G.S., Lorenço, M.S., Zidanes, U.L., Silva, L.R., Silva, E.P., Ferreira, V.R.F., Cardoso, M.G., and Mori, F.A. (2020). Characterisation and valorisation of the bark of Myrcia eximia DC. trees from the Amazon rainforest as a source of phenolic compounds. Holzforschung 74: 989–998, https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2019-0294.Search in Google Scholar

Batista, F.J. (2005). Fenologia de Croton matourensis Aubl. (Euphorbiaceae) em vegetação secundária no Município de Bragança, Estado do Pará. Boletim Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, série Ciências Naturais. Belém 1: 69–74.10.5123/S1981-81142006000100013Search in Google Scholar

Borrega, M., Kalliola, A., Määttänen, M., Borisova, A.S., Mikkelson, A., and Tamminen, T. (2022). Alkaline extraction of polyphenols for valorization of industrial spruce bark. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 19: 101129, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biteb.2022.101129.Search in Google Scholar

Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (2025). Plant species for recuperation, https://www.embrapa.br/codigo-florestal/especies-nativas-para-recuperacao (Accessed 18 April 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Brazilian Forestry Institute (2022). Amazon biome, https://www.ibflorestas.org.br/bioma-amazonico (Accessed 3 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Carmo, J.F., Miranda, I., Quilhó, T., Sousa, V.B., Cardoso, S., Carvalho, A.M., Carmo, F.H.D.J., Latorraca, J.V.F., and Pereira, H. (2016a). Copaifera langsdorffii bark as a source of chemicals: structural and chemical characterization. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 36: 305–317.10.1080/02773813.2016.1140208Search in Google Scholar

Carmo, J.F., Miranda, I., Quilhó, T., Sousa, V.B., Carmo, F.H.D.J., Latorraca, J.V.F., and Pereira, H. (2016b). Chemical and structural characterization of the bark of Albizia niopoides trees from the Amazon. Wood Sci. Technol. 50: 677–692, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-016-0807-3.Search in Google Scholar

Carmo, J.F., Miranda, I., Quilhó, T., Carvalho, A.M., Carmo, F.H.D.J., Latorraca, J.V.D.F., and Pereira, H. (2016c). Bark characterisation of the Brazilian hardwood Goupia glabra in terms of its valorisation. BioResources 11: 4794–4807, https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.11.2.4794-4807.Search in Google Scholar

Carvalho, P.E.R. (2006). Brazilian tree species. Collection of Brazilian tree species. Embrapa 2: 191–198.Search in Google Scholar

Castro, A.C.C.M., Oda, F.B., Almeida-Cincotto, M.G.J., Davanço, M.G., Chiari-Andréo, B.G., Cicarelli, R.M.B., Peccinini, R.G., Zocolo, G.J., Ribeiro, P.R.V., Corrêa, M.A., et al.. (2018). Green coffee seed residue: a sustainable source of antioxidant compounds. Food Chem. 246: 48–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.10.153.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Correia, V.G., Bento, A., Pais, J., Rodrigues, R., Haliński, Ł.P., Frydrych, M., Greenhalgh, A., Stepnowski, P., Vollrath, F., King, A.W.T., et al.. (2020). The molecular structure and multifunctionality of the cryptic plant polymer suberin. Mater. Today Bio 5: 100039, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2019.100039.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

da Silva Araujo, E., Lorenço, M.S., Zidanes, U.L., Sousa, T.B., da Silva Mota, G., de Nazaré de Oliveira Reis, V., Gomes da Silva, M., and Mori, F.A. (2021). Quantification of the bark Myrcia eximia DC tannins from the Amazon rainforest and its application in the formulation of natural adhesives for wood. J. Clean. Prod. 280: 124324, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124324.Search in Google Scholar

Esau, K. (1974). Anatomia das plantas com sementes. Blucher, Brasil, São Paulo.Search in Google Scholar

Fearnside, P. (2022). Destruição e conservação da floresta Amazônica, 1st ed. Manaus, Brasil: INPA.Search in Google Scholar

Francener, A. (2020). Byrsonima. In: Flora do Brasil 2020. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. https://floradobrasil2020.jbrj.gov.br/FB8833 (Accessed 04 January 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Franklin, G.L. (1945). Preparation of thin sections of synthetic resins and wood-resin composites, and a new macerating method for wood. Nature 155: 51, https://doi.org/10.1038/155051a0.Search in Google Scholar

Giannotas, G., Kamperidou, V., Stefanidou, M., Kampragkou, P., Liapis, A., and Barboutis, I. (2022). Utilization of tree-bark in cement pastes. J. Build. Eng. 57: 104913, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104913.Search in Google Scholar

Graça, J. and Pereira, H. (2004). The periderm development in Quercus suber. IAWA J. 25: 325–335, https://doi.org/10.1163/22941932-90000369.Search in Google Scholar

Johansen, D.A. (1940). Plant microtechnique. McGraw-Hill, London.Search in Google Scholar

Leite, C. and Pereira, H. (2017). Cork-containing barks. A review. Front. Mater. 3: 63, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2016.00063.Search in Google Scholar

Lima, E.J.S.P.D., Alves, R.G., D′Elia, G.M.A., Anunciação, T.A.D., Silva, V.R., Santos, L.D.S., Soares, M.B.P., Cardozo, N.M.D., Costa, E.V., Silva, F.M.A.D., et al.. (2018). Antitumor effect of the essential oil from the leaves of Croton matourensis Aubl. (Euphorbiaceae). Molecules 23: 2974, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23112974.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mangrich, A.S., Doumer, M.E., Mallmannn, A.S., and Wolf, C.R. (2014). Green chemistry in water treatment: use of coagulant derived from Acacia mearnsii tannin extracts. Revista Virtual de Química 6: 2–15, https://doi.org/10.5935/1984-6835.20140002.Search in Google Scholar

Mori, F.A., Mori, C.L.S.O., Mendes, L.M., Silva, J.R.M., and Melo, V.M. (2003). Influence of sulfite and sodium hydroxide on the quantification in tannins of the bark of barbatimão (Stryphnodendron adstringens). Floresta e Ambiente 10: 86–92.Search in Google Scholar

Mota, G.S., Sartori, C.J., Ferreira, J., Miranda, I., Quilhó, T., Mori, F.A., and Pereira, H. (2016). Cellular structure and chemical composition of cork from Plathymenia reticulata occurring in the Brazilian Cerrado. Ind. Crops Prod. 90: 65–75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.06.014.Search in Google Scholar

Mota, G.S., Araujo, E.S., Lorenço, M., De Abreu, J.L.L., De, O., Mori, C.L.S., Ferreira, C.A., Silva, M.G., Mori, F.A., and Ferreira, G.C. (2021a). Bark of Astronium lecointei Ducke trees from the Amazon: chemical and structural characterization. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 79: 1087–1096.10.1007/s00107-021-01670-wSearch in Google Scholar

Mota, G.S., Sartori, C.J., Ribeiro, A.O., Quilhó, T., Miranda, I., Ferreira, G.C., Mori, F.A., and Pereira, H. (2021b). Bark characterization of Tachigali guianensis and Tachigali glauca from the Amazon under a valorization perspective. BioRes 16: 2953–2970, https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.16.2.2953-2970.Search in Google Scholar

Neiva, D.M., Araújo, S., Gominho, J., Carneiro, A.de C., and Pereira, H. (2018). Potential of Eucalyptus globulus industrial bark as a biorefinery feedstock: chemical and fuel characterization. Ind. Crops Prod. 123: 262–270, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.06.070.Search in Google Scholar

Nguyen, L.T., Phan, D.-P., Sarwar, A., Tran, M.H., Lee, O.K., and Lee, E.Y. (2021). Valorization of industrial lignin to value-added chemicals by chemical depolymerization and biological conversion. Ind. Crops Prod. 161: 113219, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.113219.Search in Google Scholar

Ozogul, Y., Ucar, Y., Tadesse, E.E., Rathod, N., Kulawik, P., Trif, M., Esatbeyoglu, T., and Ozogul, F. (2025). Tannins for food preservation and human health: a review of current knowledge. Appl. Food Res. 5: 100738, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afres.2025.100738.Search in Google Scholar

Paes, J.B., Diniz, C.E.F., Lima, C.R.D., De, P., and Bastos, M. (2013). Taninos condensados da casca de angico-vermelho (Anadenanthera colubrina var. cebil) extraídos com soluções de hidróxido e sulfito. Revista Caatinga 26: 22–27.Search in Google Scholar

Pearse, A.G.E. and Anthony, G.E. (1980). Histochemistry, theoretical and applied. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, New York.Search in Google Scholar

Pereira, H. (1988). Chemical composition and variability of cork from Quercus suber L. Wood Sci. Technol. 22: 211–218, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00386015.Search in Google Scholar

Pereira, H. (2007). Cork: Biology Production and Uses. Elsevier, pp. 329–336.10.1016/B978-044452967-1/50013-3Search in Google Scholar

Pizzi, A. (2008) Tannins: major sources, properties and applications. In: Monomers, polymers and composites from renewable resources. Elsevier, pp. 179–199.10.1016/B978-0-08-045316-3.00008-9Search in Google Scholar

Pizzi, A. (2021). Tannins medical/pharmacological and related applications: a critical review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 22: 100481, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2021.100481.Search in Google Scholar

Quilhó, T., Pereira, H., and Richter, H.G. (2000). Within–tree variation in phloem cell dimensions and proportions in Eucalyptus globulus. IAWA J. 21: 31–40, https://doi.org/10.1163/22941932-90000234.Search in Google Scholar

Santos, M.F., Amorim, B.S., Burton, G.P., Fernandes, T., Gaem, P.H., Lourenço, A.R.L., Lima, D.F., Rosa, P.O., Santos, L.L.D., Staggemeier, V.G., et al.. (2020) Myrcia. In: Flora e funga do Brasil. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, https://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/FB10759 (Accessed 29 May 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Sartori, C.J., Mota, G.S., Mori, F.A., Miranda, I., Quilhó, T., and Pereira, H. (2022). Bark characterization of a commercial Eucalyptus urophylla hybrid clone in view of its potential use as a biorefinery raw material. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 12: 1541–1553, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-01199-7.Search in Google Scholar

Şen, A.U. and Pereira, H. (2021). State-of-the-art char production with a focus on bark feedstocks: processes, design, and applications. Processes 9: 87, https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9010087.Search in Google Scholar

Sen, A., Quilhó, T., and Pereira, H. (2011). Bark anatomy of Quercus cerris L. var. cerris from Turkey. Turk. J. Bot. 35: 1–11.10.3906/bot-1002-33Search in Google Scholar

Şen, A.U., Esteves, B., Lemos, F., and Pereira, H. (2023). Insights into the combustion behavior of cork and phloem: effect of chemical components and biomass morphology. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 81: 999–1010, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-023-01945-4.Search in Google Scholar

Sharma, A., Shahzad, B., Rehman, A., Bhardwaj, R., Landi, M., and Zheng, B. (2019). Response of phenylpropanoid pathway and the role of polyphenols in plants under abiotic stress. Molecules 24: 2452, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24132452.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shirmohammadli, Y., Efhamisisi, D., and Pizzi, A. (2018). Tannins as a sustainable raw material for green chemistry: a review. Ind. Crops Prod. 126: 316–332, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.10.034.Search in Google Scholar

Sillero, L., Prado, R., Andrés, M.A., and Labidi, J. (2019). Characterisation of bark of six species from mixed Atlantic forest. Ind. Crops Prod. 137: 276–284, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.05.033.Search in Google Scholar

Silva, E., Mota, G.D., Araujo, E., Sousa, T., Ferreira, C., Pereira, H., and Mori, F. (2021). Chemical composition and cellular structure of cork from Agonandra brasiliensis from the Brazilian Cerrado. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 79: 1469–1478.10.1007/s00107-021-01721-2Search in Google Scholar

Silva, M.L.A., Lucas, M.M.B.L., and Pinto, L.M.R.B. (2022). Forest startups, impact businesses and sustainability in the Amazon. Informe GEPEC 26: 30–49, https://doi.org/10.48075/igepec.v26i2.28223.Search in Google Scholar

Silva-Luz, C.L., Pirani, J.R., Pell, S.K., and Mitchell, J.D. (2023) Anacardiaceae. In: Flora e funga do Brasil, https://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/FB4408 (Accessed 04 January 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Silvestre, R.G. (2012). Chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of the essential oil from Vismia guianensis fruits. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 11: 9888–9893, https://doi.org/10.5897/ajb11.3834.Search in Google Scholar

Sousa, T.B., Mota, G.da S., Araujo, E.da S., Carréra, J.C., Silva, E.P., Souza, S.G., Lorenço, M.S., and Mori, F.A. (2022). Chemical and structural characterization of Myracrodruon urundeuva barks aiming at their potential use and elaboration of a sustainable management plan. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 12: 1583–1593, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-01093-2.Search in Google Scholar

Svendsen, A.B. and Verpoorte, R. (1983). Chromatography of alkaloids. Elsevier, New York.Search in Google Scholar

TAPPI (1991). Standard test methods for acid-soluble lignin in wood and pulp (TAPPI UM 250). In: Technical association of the pulp and paper industry. TAPPI Press, Atlanta.Search in Google Scholar

TAPPI (2007). Standard test methods for solvent extractives of wood and pulp (TAPPI T 204 om-07). In: Technical association of the pulp and paper industry. TAPPI Press, Atlanta.Search in Google Scholar

TAPPI (2021). Standard test methods for acid-insoluble lignin in wood and pulp (TAPPI T 222 om-21). In: Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper industry. TAPPI Press, Atlanta.Search in Google Scholar

TAPPI (2022). Standard test methods for ash in wood, pulp, paper, and paperboard: combustion 525°C (TAPPI T 211 om-22). In: Technical association of the pulp and paper industry. TAPPI Press, Atlanta.Search in Google Scholar

Vangeel, T., Neiva, D.M., Quilhó, T., Costa, R.A., Sousa, V., Sels, B.F., and Pereira, H. (2023). Tree bark characterization envisioning an integrated use in a biorefinery. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 13: 2029–2043, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-021-01362-8.Search in Google Scholar

Vogel Ely, C., Shimizu, G.H., Martins, M.V., and Marinho, L.C. (2023). Hypericaceae. In: Flora e funga do Brasil. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, https://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/FB25586 (Accessed 23 April 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Zidanes, U.L., Das Chagas, C.M., Lorenço, M.S., Da Silva Araujo, E., Dias, M.C., Setter, C., Braz, R.L., and Mori, F.A. (2024). Utilization of rice production residues as a reinforcing agent in bioadhesives based on polyphenols extracted from the bark of trees from the Brazilian Cerrado biome. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 254: 127813, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127813.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Wood Chemistry

- Variability in the chemical composition and antioxidant properties of sapwood and heartwood extracts of some tropical woods from Côte d’Ivoire

- Valorisation the bark of forest species as a source of natural products within the framework of a sustainable bioeconomy in the Amazon

- Wood Physics/Mechanical Properties

- Mechanism of changes in the mechanical properties of wood due to water adsorption and desorption described by rheological considerations

- Investigating sapwood and heartwood density changes of short rotation teak wood after chemical and thermal modification using X-ray computed tomography

- Wood Technology/Products

- Fire behavior of thermally modified pine (Pinus sylvestris) treated with DMDHEU and flame retardants: from small scale to SBI tests

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Wood Chemistry

- Variability in the chemical composition and antioxidant properties of sapwood and heartwood extracts of some tropical woods from Côte d’Ivoire

- Valorisation the bark of forest species as a source of natural products within the framework of a sustainable bioeconomy in the Amazon

- Wood Physics/Mechanical Properties

- Mechanism of changes in the mechanical properties of wood due to water adsorption and desorption described by rheological considerations

- Investigating sapwood and heartwood density changes of short rotation teak wood after chemical and thermal modification using X-ray computed tomography

- Wood Technology/Products

- Fire behavior of thermally modified pine (Pinus sylvestris) treated with DMDHEU and flame retardants: from small scale to SBI tests