Abstract

In this study, thermally modified Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) was impregnated with DMDHEU (1,3-dimethylol-4,5-dihydroxyethyleneurea) monomers combined with a flame retardant (FR) based on monoguanidine phosphate salt. Fire performance was assessed using ignitability tests (ISO 11925-2, 2020), mass loss calorimetry test (ISO 13927, 2015), and single burning item (SBI) tests (EN 13823, 2020). Results showed enhanced flame retardancy, reaching Class B in the SBI test. Small-scale ignitability tests revealed minor differences in flame spread across samples, unlike the SBI results. Fire growth rate and ignition time from mass loss calorimetry strongly correlated with burning suppression in the SBI test.

1 Introduction

Thermal treatment is among the most widely employed methods to enhance the fungal resistance, reduce hygroscopicity, and improve the dimensional stability of wood (Gérardin 2016). Recently, the impregnation of wood with thermosetting monomers, which polymerize within the wood structure, has gained significant attention as an effective means to enhance both its dimensional stability and durability (Jones et al. 2020). Combining thermal modification with impregnation of thermosetting monomers has been shown to provide superior improvements in these properties compared to individual treatments (Acosta et al. 2024; Mubarok et al. 2019).

Despite these advantages, neither thermal treatment (Rabe et al. 2020) nor thermosetting monomer treatment (Xie et al. 2014, 2016) can effectively enhance the flame retardancy of wood. A promising approach to address this limitation is to combine flame retardants and thermosetting monomers for wood impregnation (Hao et al. 2022; Kurkowiak et al. 2023; Lin et al. 2021; Wu et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2022). Previous studies have shown that the combination of 1,3-dimethylol-4,5-dihydroxyethyleneurea (DMDHEU) and flame retardants can enhance flame retardancy in small-scale tests (Wu et al. 2024, 2025). However, there is a lack of research investigating fire performance of such treatments in larger-scale fire tests, which are critical for meeting fire safety regulations in building applications. Moreover, the correlation between small-scale and medium-scale fire performance for wood treated with this combined approach remains unclear.

In this study, phosphorus-nitrogen flame retardants were combined with DMDHEU to treat thermally modified Scots pine (thermopine) via aqueous impregnation. The fire performance of the treated wood was assessed using ignitability tests, mass loss calorimetry, and the single burning item (SBI) test. Additionally, this work aims to establish a relationship between small-scale test results and burning behaviors observed in the SBI test, providing insights into the scalability and effectiveness of the combined treatment.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Commercially available thermally modified Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) tongue and groove boards with the dimension of 18 × 100 × 2,000 mm (rad × tang × long) were impregnated with a combination of DMDHEU (Fixapret CP liq) and a flame retardant (FR) based on monoguanidine phosphate salt (Pekoflame OP liq); both supplied by Archroma (Switzerland). Both DMDHEU and the flame retardant exhibit low viscosity, making them suitable for wood impregnation.

2.2 Treatment process

To determine the initial dry density, all specimens were dried in an oven at 103 °C until a constant mass was achieved. Aqueous solutions of DMDHEU and FR were prepared with the following concentrations: 9.0 % DMDHEU combined with 7.7 % FR (Treatment A), 13.0 % DMDHEU combined with 11.2 % FR (Treatment B), and 18.0 % DMDHEU combined with 15.5 % FR (Treatment C). Sample preparation involved impregnation under vacuum conditions for 2 h, followed by a pressure phase at 10 bar for 4 h. After treatment, the specimens were first air-dried and then further dried in a pilot dryer at a maximum temperature of 120 °C.

The weight percent gain (WPG) was calculated based on the oven-dry weight before and after treatment (muntreated and mtreated, respectively), as defined by Equation (1).

2.3 Ignitability test

A burner box (KBK 917, Netzsch, Germany) was used to evaluate the flame spread according to ISO 11925-2 (British Standards Institution 2020b). The test time was extended to 90 s to better compare the differences between different wood specimens. Four replicates (18 × 100 × 200 mm, rad × tang × long) were tested for each group.

2.4 Mass loss calorimeter test

Mass loss calorimeter (Fire Testing Technology Ltd, UK) was used to evaluate the heat release of wood specimens. The test was performed according to ISO 13927 (European Committee for Standardization 2015) under an external heat flux of 50 kW/m2. Eight replicates (18 × 100 × 100 mm, rad × tang × long) were tested for each group. The fire growth rate (FIGRA) was calculated based on the heat release rate peak (HRRp) and time to HRR peak (t1), as defined by Equation (2) (Schartel and Hull 2007).

2.5 Single burning item test

SBI test (Fire Testing Technology Ltd, UK) was used to evaluate the heat release of wood specimens. The test was performed according to EN 13823 (British Standards Institution 2020a), with the specimens assembled in the standard horizontal configuration and then fixed to a support. The test was conducted in MEKA (Latvia) and the fire classification was carried out in accordance with EN 13501-1 (British Standards Institution 2002).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Ignitability test

Treatment A resulted in a WPG of 10.5 % (±4.2 %), Treatment B achieved a WPG of 16.2 % (±4.0 %), and Treatment C produced a WPG of 23.4 % (±7.5 %). The variation in WPG values is attributed to the mix of sapwood and heartwood in thermopine, as heartwood is more difficult to impregnate compared to sapwood. Ignitability tests with single flame source were carried out to assess the flame spread on the wood surface. As illustrated in Figure 1, the reference thermopine exhibited a flame height exceeding 150 mm after 30 s of burning, highlighting its high flammability. In contrast, specimens impregnated with DMDHEU and the FR insubstantially reduced both flame height and flame spread area, even when the burning duration was extended to 90 s.

Flame height (left) and flame spread images (right) of the reference thermopine (R) after 30 s of flame exposure, and thermopine treated with A, B, and C after 90 s of flame exposure, respectively.

Higher concentrations of treatment chemicals could further suppress the flame spread. However, due to the high efficacy of the combined treatment, even low chemical concentrations were sufficient to effectively inhibit flame propagation. Consequently, no significant differences in flame spread behavior were observed among specimens treated with varying retention levels of DMDHEU and FR.

In summary, the combined treatment demonstrated outstanding performance in mitigating flame spread under exposure to a small single-flame source, even at low chemical uptake levels.

3.2 Mass loss calorimeter test

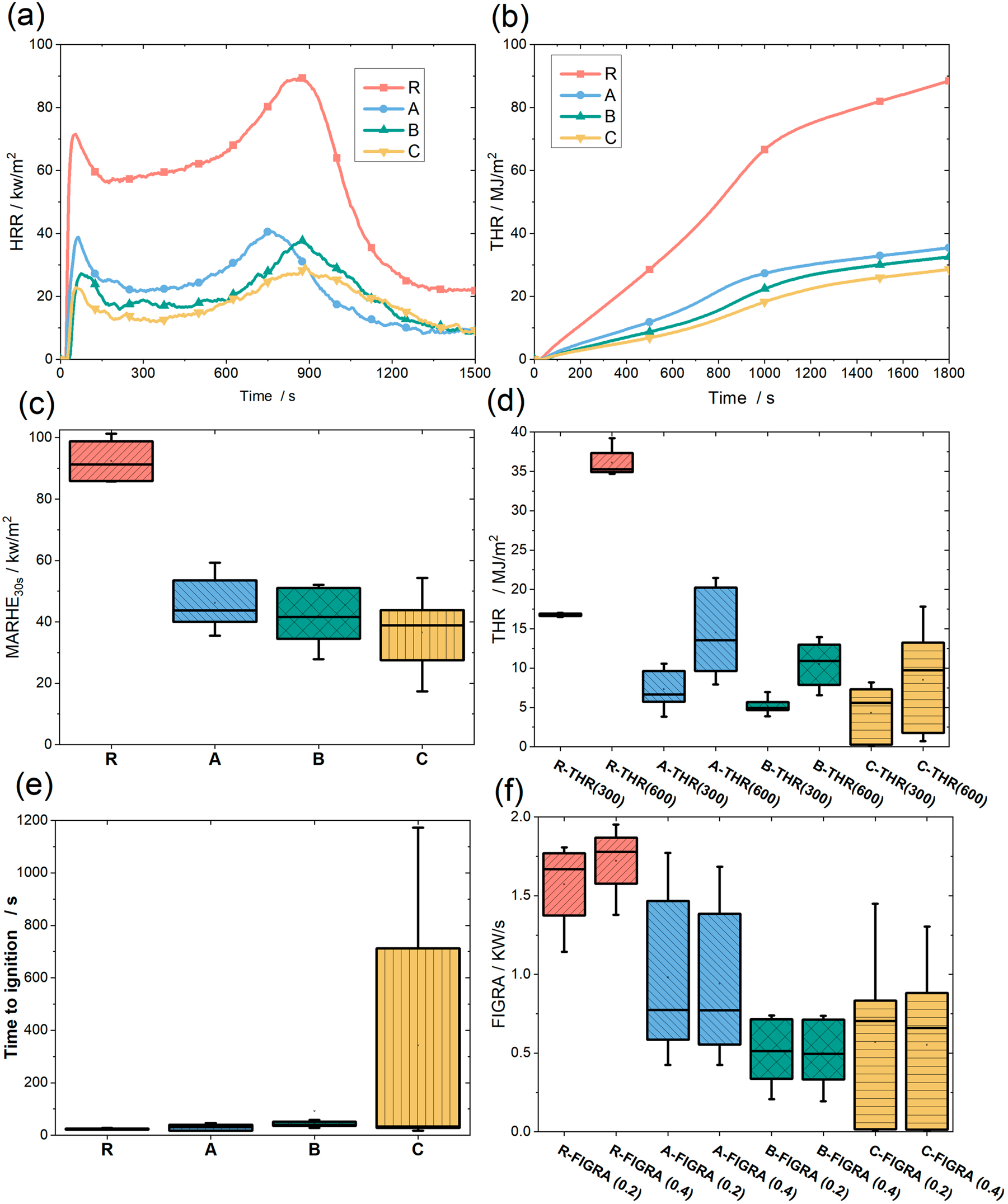

The key parameters used to assess fire performance are the HRR and the total heat release (THR). Figure 2a and b present the average HRR and THR curves for each group. Additionally, Figure 2c and d display the MARHE and the THR within 300 and 600 s, respectively. Thermopine exhibited a similar combustion pattern to untreated wood, characterized by two distinct HRR peaks (Wu et al. 2023). Compared to untreated thermopine, the combined DMDHEU and FR treatment significantly reduced the THR within 600 s, achieving reductions of up to 76 %.

Mass loss calorimeter data of (a) heat release rate (HRR), (b) total heat release (THR), (c) maximum average rate of heat emission (MAHRE) within a 30-s time window, (d) THR within 300 s and 600 s, (e) time to ignition and (f) fire growth rate index (FIGRA) based on THR at 0.2 MJ/m2 and 0.4 MJ/m2 of the reference thermopine (R) and thermopine treatment with A, B and C, respectively.

Moreover, increasing the concentration of the treatment chemicals further decreased the HRR. As shown in Figure 2e, the ignition time was delayed by the combined treatment. At higher concentrations, some specimens in treatment group C did not ignite within 600 s, demonstrating superior flame retardancy.

The FIGRA indicates the rate of fire development, with higher values corresponding to more rapid burning. Compared to the reference samples, the combined treatment significantly reduced the FIGRA. Notably, treatment group B performed significantly better than group A, as some specimens in group A exhibited FIGRA values comparable to those of reference thermopine. Group C showed variability in FIGRA values: while some specimens achieved very low FIGRA due to their prolonged ignition time, others ignited more quickly, resulting in higher FIGRA values. This variability may be attributed to the natural heterogeneity of wood, where specimens containing predominantly heartwood may have limited FR penetration, resulting in inconsistent performance.

3.3 Single burning item test

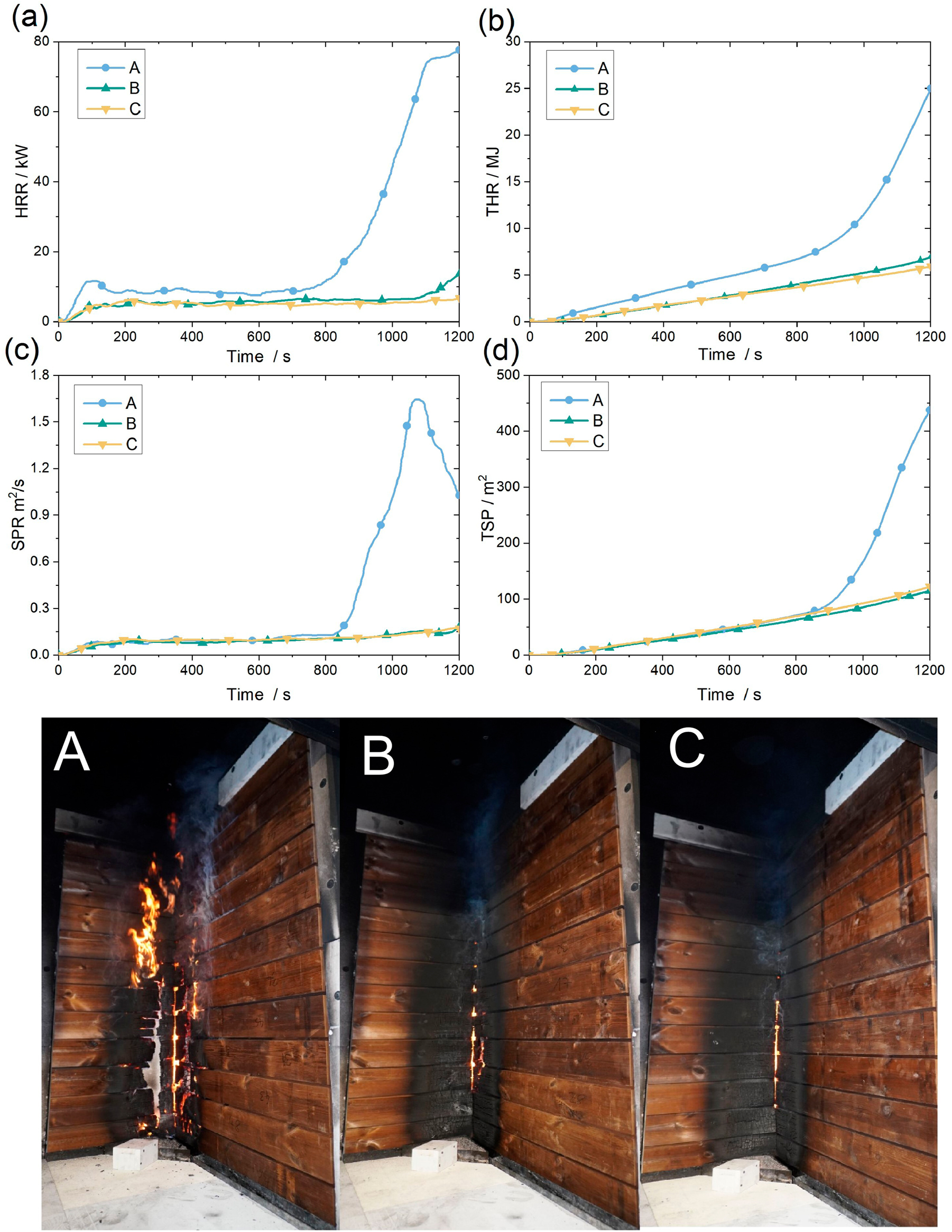

The SBI test is used to evaluate the fire reaction behavior of wood building products (Laranjeira et al. 2015). Group A demonstrated a higher FIGRA (0.2 MJ) of 134.9 W/s and FIGRA (0.4 MJ) of 129.2 W/s, which do not meet the Class B criteria specified in EN 13501, where FIGRA (0.2 MJ) must not exceed 120 W/s. However, the THR (600 s) of Group A was only 4.7 MJ, well below the Class B threshold of 7.5 MJ. These results conform the mass loss calorimeter results that some specimens showed higher FIGRA values similar to the reference but generally exhibited significantly lower HRR peaks and THR. This suggests that inadequate impregnation at a low concentration of chemicals may reduce the fire classification in SBI test, preventing them from achieving Class B.

In contrast, both treatment B (FIGRA (0.2 MJ) of 37.8 W/s and THR (600 s) of 2.8 MJ) and treatment C (FIGRA (0.2 MJ) of 43.0 W/s and THR (600 s) of 2.7 MJ) successfully met the Class B criteria. No significant differences were observed between treatments B and C in the SBI test. Although treatment C exhibited variability in FIGRA results during the mass loss calorimeter test, this did not impact its SBI performance.

All specimens achieved an S1 rating in smoke production, indicating limited smoke release. The rapid smoke release observed after 800 s in treatment A was due to the progression of flame spread, as shown in the bottom of Figure 3. By comparison, both treatments B and C significantly reduced flame spread. Interestingly, these results are in contrast with those from the ignitability test, where no significant differences in flame spread were observed among treatments A, B, and C. This discrepancy could be attributed to the longer flame exposure (1,200 s) and the high-intensity flame of the auxiliary burner in the SBI test, which likely promoted combustion more rapidly than the small single-flame source.

Single burning item data of (a) heat release rate (HRR), (b) total heat release (THR), (c) smoke production rate (SPR), (d) total smoke production (TSP) of the reference thermopine (R) and thermopine treatment with A, B and C, respectively. The image at the bottom shows the specimens at the end of the SBI test.

4 Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the fire performance of thermopine treated with DMDHEU and flame retardants. The key findings are summarized as follows:

Low chemical uptake could significantly suppress flame spread in the small single-flame ignition test.

As chemical concentration increased, specimens exhibited improved flame retardancy in the mass loss calorimeter test, though some variations were observed due to inadequate impregnation of wood.

The SBI test results demonstrated that even at low chemical concentrations, the THR could meet the requirements for Class B. However, the FIGRA exceeded the threshold, consistent with findings from the mass loss calorimeter test. Medium- and high-concentration treatments successfully achieved Class B ratings.

In conclusion, the combined treatment of DMDHEU and flame retardants significantly enhanced the flame retardancy of thermally modified wood. A relationship between small-scale and medium-scale fire tests was identified, where a lower FIGRA and longer ignition times in mass loss calorimeter test played a crucial role in achieving favorable SBI test performance.

Acknowledgments

Muting Wu acknowledges the support of the China Scholarship Council (202003270024).

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Muting Wu: writing – original draft, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing – review & editing. Christoph Hötte: writing – review & editing, investigation, methodology. Johannes Karthäuser: writing – review & editing, methodology. Holger Militz: project administration, review & editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Some sentences in this manuscript were polished with the help of ChatGPT during revision to improve readability

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Acosta, A.P., Beltrame, R., Missio, A.L., Amico, S., De Avila Delucis, R., and Gatto, D.A. (2024). Furfurylation as a post-treatment for thermally-treated wood. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14: 4313–4323, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-022-02821-6.Search in Google Scholar

British Standards Institution (2002). Fire classification of construction products and building elements. Part 1: classification using test data from reaction to fire tests (BS EN 13501-1, 2002).Search in Google Scholar

British Standards Institution (2020a). Reaction to fire tests for building products. Building products excluding floorings exposed to the thermal attack by a single burning item (BS EN 13823, 2002).Search in Google Scholar

British Standards Institution (2020b). Reaction to fire tests. Ignitability of products subjected to direct impingement of flame: single-flame source test (BS EN ISO 11925-2, 2020).Search in Google Scholar

European Committee for Standardization (2015). Plastic: simple heat release test using a conical radiant heater and a thermopile detector (EN ISO 13927, 2015).Search in Google Scholar

Gérardin, P. (2016). New alternatives for wood preservation based on thermal and chemical modification of wood: a review. Ann. For. Sci. 73: 559–570, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-015-0531-4.Search in Google Scholar

Hao, X., Li, M., Huang, Y., Sun, Y., Zhang, K., and Guo, C. (2022). High-strength, dimensionally stable, and flame-retardant fast-growing poplar prepared by ammonium polyphosphate–waterborne epoxy impregnation. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 4: 1305–1313, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.1c01712.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, D., Sandberg, D., Goli, G., and Todaro, L. (2020). Wood modification in Europe: a state-of-the-art about processes, products and applications, 1st ed. Firenze University Press, Florence.10.36253/978-88-6453-970-6Search in Google Scholar

Kurkowiak, K., Wu, M., Emmerich, L., and Militz, H. (2023). Fire-retardant properties of wood modified with sorbitol, citric acid and a phosphorous-based system. Holzforschung 77: 38–44, https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2022-0114.Search in Google Scholar

Laranjeira, J.P., dos, S., Cruz, H., Pinto, A.P.F., Pina dos Santos, C., and Pereira, J.F. (2015). Reaction to fire of existing timber elements protected with fire retardant treatments: experimental assessment. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 9: 866–882, https://doi.org/10.1080/15583058.2013.878415.Search in Google Scholar

Lin, C., Karlsson, O., Martinka, J., Rantuch, P., Garskaite, E., Mantanis, G.I., Jones, D., and Sandberg, D. (2021). Approaching highly leaching-resistant fire-retardant wood by in situ polymerization with melamine formaldehyde resin. ACS Omega 6: 12733–12745, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c01044.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mubarok, M., Dumarcay, S., Militz, H., Candelier, K., Thevenon, M.F., and Gérardin, P. (2019). Comparison of different treatments based on glycerol or polyglycerol additives to improve properties of thermally modified wood. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 77: 799–810, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-019-01429-4.Search in Google Scholar

Rabe, S., Klack, P., Bahr, H., and Schartel, B. (2020). Assessing the fire behavior of woods modified by N-methylol crosslinking, thermal treatment, and acetylation. Fire Mater. 44: 530–539, https://doi.org/10.1002/fam.2809.Search in Google Scholar

Schartel, B. and Hull, T.R. (2007). Development of fire-retarded materials: interpretation of cone calorimeter data. Fire Mater. 31: 327–354, https://doi.org/10.1002/fam.949.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, M., Emmerich, L., Kurkowiak, K., and Militz, H. (2023). Fire resistance of pine wood treated with phenol-formaldehyde resin and phosphate-based flame retardant. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 18: 1933–1939, https://doi.org/10.1080/17480272.2023.2205379.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, M., Emmerich, L., Kurkowiak, K., and Militz, H. (2024). Combined treatment of wood with thermosetting resins and phosphorous flame retardants. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 82: 167–174, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-023-02012-8.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, M., Emmerich, L., and Militz, H. (2025). Enhancing fire resistance in pine wood through DMDHEU resin and phosphate-nitrogen flame retardant synergies. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 83: 56, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-025-02207-1.Search in Google Scholar

Xie, Y., Liu, N., Wang, Q., Xiao, Z., Wang, F., Zhang, Y., and Militz, H. (2014). Combustion behavior of oak wood (Quercus mongolica L.) modified by 1,3-dimethylol-4,5-dihydroxyethyleneurea (DMDHEU). Holzforschung 68: 881–887, https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2013-0224.Search in Google Scholar

Xie, Y., Xu, J., Militz, H., Wang, F., Wang, Q., Mai, C., and Xiao, Z. (2016). Thermo-oxidative decomposition and combustion behavior of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) sapwood modified with phenol- and melamine-formaldehyde resins. Wood Sci. Technol. 50: 1125–1143, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-016-0857-6.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, L., Ran, Y., Peng, Y., Wang, W., and Cao, J. (2022). Combustion behavior of furfurylated wood in the presence of montmorillonite and its char characteristics. Wood Sci. Technol. 56: 623–648, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-022-01369-y.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Wood Chemistry

- Variability in the chemical composition and antioxidant properties of sapwood and heartwood extracts of some tropical woods from Côte d’Ivoire

- Valorisation the bark of forest species as a source of natural products within the framework of a sustainable bioeconomy in the Amazon

- Wood Physics/Mechanical Properties

- Mechanism of changes in the mechanical properties of wood due to water adsorption and desorption described by rheological considerations

- Investigating sapwood and heartwood density changes of short rotation teak wood after chemical and thermal modification using X-ray computed tomography

- Wood Technology/Products

- Fire behavior of thermally modified pine (Pinus sylvestris) treated with DMDHEU and flame retardants: from small scale to SBI tests

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Wood Chemistry

- Variability in the chemical composition and antioxidant properties of sapwood and heartwood extracts of some tropical woods from Côte d’Ivoire

- Valorisation the bark of forest species as a source of natural products within the framework of a sustainable bioeconomy in the Amazon

- Wood Physics/Mechanical Properties

- Mechanism of changes in the mechanical properties of wood due to water adsorption and desorption described by rheological considerations

- Investigating sapwood and heartwood density changes of short rotation teak wood after chemical and thermal modification using X-ray computed tomography

- Wood Technology/Products

- Fire behavior of thermally modified pine (Pinus sylvestris) treated with DMDHEU and flame retardants: from small scale to SBI tests