Abstract

This essay explores how artifice and queer form in Bertrand Mandico’s film The Wild Boys (2017. Dir. Bertrand Mandico. Ecce Films) interrogate more-than-human entanglements to orient viewers toward a trans ecology. In Mandico’s botanical imaginary, he crafts a world of excessive artifice where both the characters and the land in which they inhabit are entirely mutable. By creating a polymorphously perverse world where there is no such thing as a hermetically sealed body, Mandico uses plants to explore the possibilities of transness and how it may provide a focus for epistemological positions, knowledge, and orientations toward a post-anthropocentric future.

1 Introduction

The feature films of experimental filmmaker Bertrand Mandico are characterized by their eroticism, lavish landscapes, and dreamlike style. Mandico’s surrealist techniques cross boundaries of material substance and gender, often utilizing fantasy as a means by which to imagine worlds of pre- or post-anthropocene. In After Blue (2021), Mandico chronicles a tale of a mother and daughter who live on a virgin planet where only women and plants can survive. In She is Conann (2023), Mandico retells the story of Conan the Barbarian through a lesbian love affair. These films are marked by their ability to subvert reality, aesthetic, and hegemonic order.

In The Wild Boys (2017), Bertrand Mandico creates a world of artifice where both the characters and the world in which they interact are entirely mutable. Boys become girls, girls become boys, fruits become erotic objects, and hallucination becomes reality. By creating a polymorphously perverse world where there is no such thing as a hermetically sealed body, Mandico uses plants to explore the possibilities of transness and how it may provide a focus for epistemological positions, knowledge, and orientations toward a post-anthropocentric future. Mandico presents these more-than-human entanglements not only on a narrative level, but also on an aesthetic one. As articulated by Kandice Chuh in The Difference Aesthetics Makes,

The aesthetic is perhaps most familiar as a term used to describe a set of characteristics (as in “the aesthetics of”) and judgments thereof, or precisely in contradistinction to politics (or, in other words, as without immediate material consequences and distant from the poles of power). … Embraced or disavowed, its persistent presence in the intellectual traditions that ground the epistemologies organizing our received knowledge practices is indicative of the ways in which the aesthetic is deeply embedded in the history and structures of modern thought (Chuh, 2019, pp. 17–18).

The nature of aesthetics itself is oblique to hegemonic order and as such implores the viewer to investigate by what legitimating authority the sensus communis of reasonability is formed. Additionally, as Galt and Schoonover describe in Queer Cinema and the World, cinema itself is a queerly inflected medium, and as such is ripe for aesthetic inquiry:

The queer worlds we explore are made available through cinema’s technologies, institutional practices, and aesthetic forms, which together animate spaces, affective registers, temporalities, pleasures, and instabilities unique to the cinematic sensorium. It is crucial to affirm that cinema is not simply a neutral host for LGBT representations but is, rather, a queerly inflected medium (Galt & Schoonover, 2016, p. 6).

Therefore, simply by virtue of being a film itself, the “queerness” of The Wild Boys is polyvalent as it is present not only in the subject matter but in the aesthetic choices that Mandico makes. These multiple registers of queerness suggest that the viewer is being oriented, at least in some way, against a reification of meaning. As such, special attention must be paid not only to the events that take place within the film, but to how Mandico chooses to present them to the spectator visually, sonically, and temporally.

2 Aesthetic Crudeness and Queer Form

After a phantasmagorical evening where a group of boys assault their English teacher under the instruction of a bejeweled mask known as Trevor, they are placed under the care of a Dutch sea captain in order to rectify their crimes. The Captain is responsible for taming wild youth and does so by taking them to what is later revealed as Dress Island, an island that is named for its ability to transform men into women. The boys, Jean-Louis, Romuald, Tanguy, Hubert, and Sloane are not aware of this fact and submit to The Captain’s commands.

From the moment the boys begin their journey with The Captain, the film is unapologetically crude and overtly sexual. While aboard the ship, The Captain flashes his tattooed penis to the boys, telling them “If you want something to read, come and see me.” From the unruly boys to the disposition of The Captain, the beginning of the film feels undeniably masculine. It is, after all, a crime against the feminine that lands the boys in such a position. After a harrowing journey across the ocean, “They happily regained the comfort of dry land, but not without alarm. The island resembled nothing they knew. An ungracious mountain covered with luxurious and malodorous vegetation” (42:50).[1] When the boys ask where they have arrived, The Captain replies “Nowhere” and insists the boys cover their eyes with cloth blindfolds.

At first, the island is intentionally hidden and obstructed from their view; The Captain is acutely aware of its effects and initially implores the boys to resist its temptations. “Something licked me!” the boys exclaim. The Captain tells them to move forward in silence until he warns “We’re going to cross a field of groping grass” (45:22). Here, the island is explicitly described as having sexual characteristics and tendencies. The grass extends its tentacles upward, grasping for the boys as they attempt to evade its tendrils. The narrator continues “This island was most strange. The vegetation seemed alive, the field striking, sucking, biting, and this pungent smell of oysters. They were like dwarves on a giant dirty girl” (46:00). One boy, Hubert, who is instructed to go without a blindfold so that he may lead the boys, comments on mushrooms that look like asses.

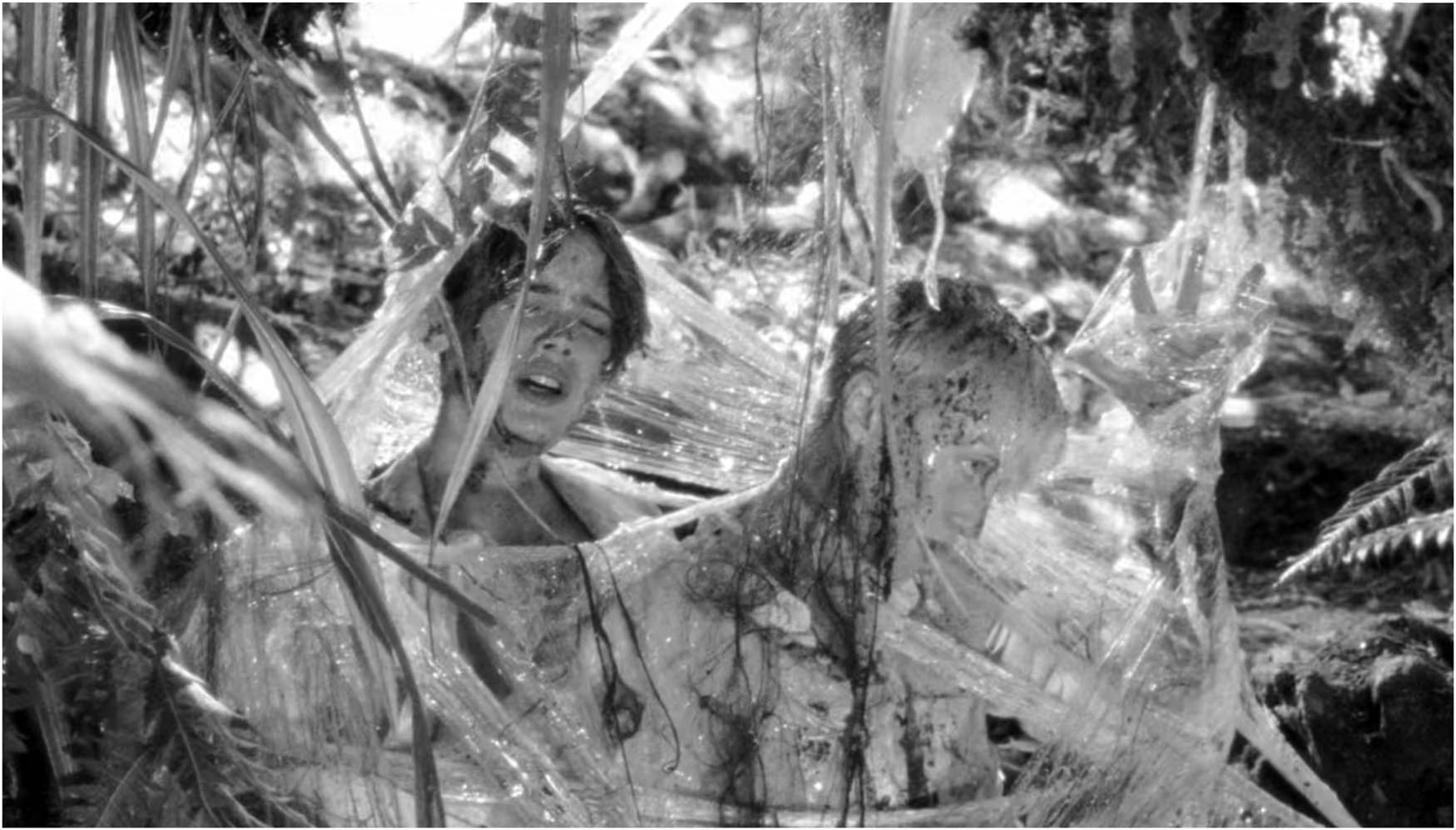

After finally arriving at the heart of the island, The Captain instructs the boys to take off their blindfolds. The first vegetation they witness is an ejaculating plant, a cactus-like object with phallic appendages from which The Captain says to drink if they are thirsty. A furry plant shaped like a woman’s legs sits open and waiting to receive them. Some of the boys become entrapped in a sticky substance, only able to escape by urinating on themselves to dissolve the web (Figure 1).

The Wild Boys (2017).

Though initially repulsed by the island, calling it disgusting, filthy, and wet, the boys eventually yield to its offerings. Thirst is not the only compulsion the island can quench; various plants offer solutions for other desires and discomforts. If you are hungry, if you are tense, The Captain says “Take advantage of the pleasures” (47:54). When The Captain leaves, the boys heed his word and begin drinking from the plant, calling its ejaculate divine (Figure 2). “Pleasures were unlimited on the island,” the narrator says, “They tried not to understand why The Captain brought them to such a place. Was it their feverish delirium or reality?” Another boy has what appears to be intercourse with a plant (Figure 3). This is filmed in slow motion with a distended soundtrack, showcasing the pleasure on the boys’ faces.

The Wild Boys (2017).

The Wild Boys (2017).

This event is the first of many where the boys facilitate more-than-human entanglements with the island. This relationship between the boys and the plants is deviant on multiple levels: first, these encounters are materially crude, and second, they are a crossing of plant and human boundaries.

The island is a clear display of artifice, as though it is a tropical landscape that would be assumed to be “natural”; it is obvious that every bit of amphibious vegetation that inhabits it is a meticulously picked and stylized mise-en-scène. Drawing inspiration from Joris-Karl Huysman’s (2003) novel À rebours (Against Nature), the film is almost decadent in its fakeness (Huysman, 2003). The island is a simulacrum of plants, the set more closely resembling lush textiles and jewels than the natural world. Though filmed on the island of La Réunion in the Indian Ocean, Mandico manufactures the appearance such that the film could have been set entirely in a studio. An erotic paradise, the island acts as a terrarium, encasing the boys and thereby creating a physical space where anything is possible. The island does not attempt to disguise itself. It is overtly sexual, excessively so, an artifice that is as self-aware as it is designed, and as unapologetic in its crudeness as it is in its fakeness.

In “Crude Matter, Queer Form,” Kyla Tompkins suggests that crudeness in the film points us toward an “immanent labor of aesthetics,” one in which something may come into social coherence by being an aestheticized object (Tompkins, 2017, p. 266). In this way, an aesthetic object, in this case the island, might direct us “toward the productive possibilities of thinking with the discarded and the deviant. Spit; the sticky. Kinaesthetic and synaesthesic re-orderings. Movements between and below frames of legibility” (Tompkins, 2017, p. 267). This scene formally embodies these qualities described by Tompkins as the boys literally ingest the “spit” of the plant and become entrapped in a sticky web. It is only through these veritable acts of crudeness, swallowing the ejaculate and urinating on themselves, that they might assuage their discomforts.

Tompkins argues that art comprised of inorganic material like plastic often loses the ability to capture the movement of crudeness:

I wonder whether this is because, in its commitment to the object-ness of materiality, even the most plastic of art practices tends to abandon the critical engagement with sensation, movement, and mutation … the onomatopoeic ejaculation of spit (crachat) or the crushing (écraser) of a spider (Tompkins, 2017, p. 266).

Unlike the pieces of art that Tompkins criticizes, Mandico uses plastic to achieve this aesthetic crudeness. Though meant to represent the earth, the island is carefully curated and aestheticized, bordering on the hyperreal. The most organic elements of plant, earth, and soil are represented by the most inorganic materials of plastic and synthetic compounds. In this way, through this paradoxical alignment with its materials, the island is a queering of form wherein inorganic materials represent the most organic of acts: sex, orgasm, and pleasure. This, too, is a queering of material relationships, as in filming the scenes Mandico requires an enmeshment of organic and inorganic material. The actors must physically engage with the set, putting the plastic phallic appendages in their mouths. The flesh of the boys is in direct contact with the artificial materials that make up the set of the island. One can imagine the sensation of placing plastic in their mouth, hard, cold, and unyielding. Tompkins suggests that this crude aesthetic can orient us toward alternative paradigms of order:

What I have referred to here as “deformation” both represents and acts out how the deviance of crude matter aligns with a project of a déclassement—a queer, perverse, or non-normative aesthetic through which scholars and artists might access alternative organizations of the sensus communis (Tompkins, 2017, p. 267).

In this way, the crudeness of the plants is itself a queer form, one which suggests that we might use aesthetics to reject dominant epistemologies for social legibility.

This deformation is witnessed too, on a haptic level. Immediately after this encounter, the film that was previously in black and white is now in vibrant color. The ferns can be seen in a shade of lush green, invigorating the senses of the viewer in a similar way to that of the boys.

Here, is it clear that both the boys and the film have experienced a significant change. In shifting the color, Mandico creates a haptic experience for both the boys and the viewer. The change from black and white to color:

[…] is to disrupt representational form via a process of deformation in which “insubordinate colors and traits” interfere with the original: “There is indeed a change of form, but the change of form is a deformation; that is, a creation of original relations which are substituted for the form.” This process, [.] produces an aesthetic that allows for “haptic” encounters with form in the process of formation and deformation (Tompkins, 2017, p. 267; Deleuze, 2003, p. 158).

This change in color allows the viewer to be acutely aware of the events that are taking place; they are distinct from those that occurred prior to the boys’ arrival upon the island. The events that took place prior to the film’s colorization are subordinate to those that will succeed it. The boys are leaving behind the world that they knew before entering the island: one that was rigid, masculine, and binary, in favor of another. While they may not yet be aware of what has taken place, this event signifies their first deconstruction of the hegemonic gender order. This dichotomy, male and female, is further articulated by the oscillation between grayscale and color, as the film, too, exists in and between these binaries.

The second valence of deviance is the sexual relations between the boys and the plants. In this scene, the narrator explicitly describes the island as having human, and specifically female, characteristics. Asymmetrically, in order to engage with the island and relieve themselves of their discomforts, the boys must behave in a way that distorts traditional masculinity. This continues a trope frequently explored in imperial romance novels wherein European travelers “crossed the dangerous thresholds of their known worlds” in order to sexually engage with plants: “the plants in these lost world novels are not analogically or dramatically linked to attractive female characters but come to replace such characters altogether, troubling the gender dynamics often identified in imperial romance” (McCausland, 2021, p. 498). While the phallic nature of the plants does not necessarily replace the physical body of a woman, it replaces female characters as becoming the object of pleasure. Though the island is a physical manifestation of human anatomy, because it is entirely comprised of plants, it creates a space for a cross-species ontology. The boys are engaging in human sex acts but with non-human entities.

[…] most sexuality is inherently about intercorporeality, about a potential merging of bodies, wills and intentions, about a transmission of matter, and about an intrinsic vulnerability in which the embodied subject is not only open to the other in an abstract way, but is likely to be in a physical contact that is neither wholly predictable nor decidable (Shildrick, 2009, p. 118).

It is this intercorporeality, the combining and transgressing of plant and human body, that begins the transformation of the boys. The plants are responsible for their pleasure, engaging and stimulating their bodies in such a way that they ought not to resist their urges. The boys collectively “give in” to what the island has to offer, submitting their corporeal desires to non-human entities.

In a moment of “sobering up,” the boys wipe their mouths, straighten their clothes, and the film resumes at a regular speed. The film is now in color, and Hubert decides to search for The Captain. As Hubert watches from afar, a voyeur, we see The Captain resting in a stream, appearing in a state of hypnosis as he speaks to another figure who emerges from the foliage.

It is at this point in the film when both the viewer and the boys are introduced to Doctor Severin(e), a man who has become a woman but uses the pronouns he/him. Notably, Severin is played by Elina Löwensohn, who also plays gender-bending roles in Mandico’s other films. The Captain delivers an offering, a bag full of dresses, wigs, and jewels, but Severin tells him that it is not enough. “Put the dress over your black breast, and the wig up your ass,” Severin tells him. Despite this disappointment, Severin insists that his method will be emulated. At this point in the film, it is unclear what method or desire of Severin’s is to be realized.

The following morning, as the boys search for Hubert, Severin finds Hubert immobilized by a plant, again bound by a sticky substance and caught like a fly in a trap. When Severin asks Hubert what he sees when he looks at him, Hubert says that he looks like a woman, and Severin replies “You are taken by appearances” (01:02:11).

Abandoning Hubert, The Captain gathers the rest of the boys, insisting that they leave the island immediately. Hesitant, the boys leave with The Captain but eventually kill him while at sea so that they may return. “We had one idea in mind […]” they say, “to return to the island of pleasure.” When the boys return to the island after “conquering” The Captain, they celebrate by “getting drunk like lords” (1:14:46–1:18:15). This scene, like the boys’ first encounter with pleasure on the island, is again in vibrant color, suggesting another pivotal shift in form.

As the boys are shown stumbling and drinking on the beach, the narrator says “It was like a premonitory hallucination. Salty and sweet, hard and yielding. The most beautiful of hallucinations.” The descriptions of the hallucination are undeniably phallic, the juxtapositions explicit in their description. This description is also prophetic as this celebration is in fact the last event where the boys will revel in their masculinity. A premonitory hallucination indeed, but in a ritual antithetical to that of the Maypole, the boys’ celebration predicts the onset of the loss of their phallic members.

Throughout the scene, there are various sounds that are played, though the boys’ mouths are agape in such a way that it is unclear as to whether the sound is extradiegetic or coming from their mouths. What begins as the howling of dogs crescendos into a kind of opera singing, increasing in octave as the boys’ mouths open in a way that suggests orgasm. The boys collapse to the ground in something between a fight and an orgy, hitting and groping each other in a way that is both overtly sexual and violent. Tanguy chokes Sloane in such a way that it is unclear as to whether or not he intends to choke or eroticize him.

It is in these blurred moments of violence and eroticism, crudeness and intimacy, that Mandico changes form. The boys are no longer the one-dimensional, violent school boys they were prior, but are beginning some kind of transformation that is not yet complete.

This scene, much like the rest of the film, is highly tactile. The boys are rolling around in the sand and into waves while being engulfed in a flurry of feathers. These elements, along with the way in which the boys are groping at one another, make this scene haptic on both the level of touch and content. The viewer can imagine themselves interacting with the organic materials in the scene, the sand, the water, the feathers, and the skin. The scene is crude physically, filled with raw materials, but also in its display of the orgy.

The scene is shot as if it were pornography, the camera shifting every few seconds to capture every erotic touch and reaction from the boys. This is a stark change from the majority of the rest of the film where the camera is stabilized and filming the boys from afar. It is this combination of crudeness and movement that allows Mandico to create a haptic experience for the viewer:

Movement is the modality through which both form and formlessness can perhaps most productively be understood. Taking up movement and phenomenality as optics through which to put formalism more intensely into conversation with formlessness and, in turn, with crude materiality might bring us to the more creative senses of crude materiality obscured by formalism’s traditional investment in consistency, pattern, recurrence, and legibility (Tompkins, 2017, p. 266).

Through this scene, the boys begin engaging with their own bodies in a way that is phenomenologically distinct from how they were previously involved. They have exchanged aggression for attraction and repression for catharsis. Though the boys do not know it, this moment of hallucinogenic euphoria signals the beginning of their transformations upon their return to the island.

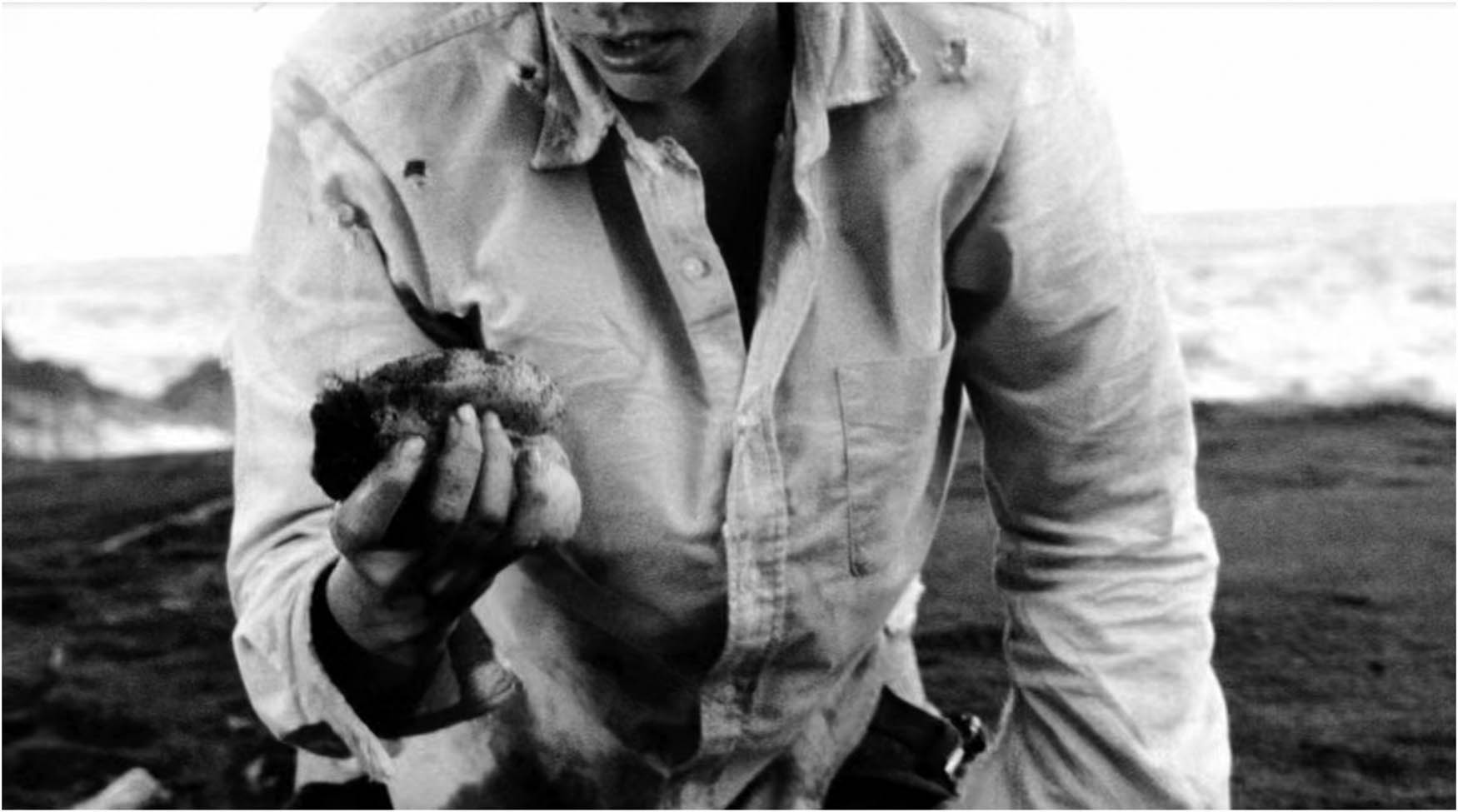

3 Trans Speciated Selves

Following this “climax,” the boys begin experiencing a number of physical transformations. “Tanguy,” the boy Sloane says, “I’ve grown breasts. What’s happening to us?” (1:24:32). “My dick!” exclaims Jean-Louis, holding his disembodied member in his hand (Figure 4). “A new perspective opens to you,” responds Romuald, signaling yet another change in the form of the boys. Both their bodies and their psyches are changing as they submit to the power of the island. As a celestial sound plays and light streams from the sky, the boys’ faces are struck with seraphic smiles.

Jean-Louis holding his disembodied member: The Wild Boys (2017).

It is in this transformation that Mandico’s choice to use female actors as males becomes prominent. The Wild Boys is a film of artifice, and Mandico wants the viewer to be acutely aware of that. Though the viewer may be aware that the boys are being played by female actresses, their appearances look perfectly boyish until this transformation begins. By using female actors, Mandico is able to produce a prosthetic that can literally fall off, producing both a physical and phenomenological change of form. According to Allison Hobgood, “Prosthetic matter functions […] as the basic material of intersubjective exchange and emotional encounter between bodies in the world” (Hobgood, 2016, p. 1292). The boys are forced to confront their relationship with their bodies, which is not only a physical but an emotional one. The penises that previously functioned as amulets of their masculinity no longer serve their purpose. They are transitioning, transmogrifying, physically and phenomenologically, and they cannot stop this change.

This kind of transformation is described in Eva Hayward’s “More Lessons From A Starfish, Prefixial Flesh and Transspeciated Selves,” which describes a critical enmeshment of trans becoming. Hayward states that “to be trans- is to be transcending or surpassing particular impositions, whether empirical, rhetorical or aesthetic”; it is to start in one place and end in another (Hayward, 2008, p. 68). The Wild Boys starts and ends in different places across all three of the realms Hayward describes as their transness disturbs “boundaries of sexual and species differences, artificial and authentic orderings” (Hayward, 2008, p. 68). Not only do the boys transgress boundaries of species, but they aesthetically change form as they lose their members and become “feminized.” As their bodies experience these changes, the boys are transcending their previous corporeal forms. Both consciously and subconsciously, consensually and non-consensually, they are leaving behind the binaries and bodies to which they previously adhered.

At this point in the film, the boys’ bodies are shown to be entirely mutable, both in form and function. First engaging in an intercorporeal relationship with the plants, they now begin engaging in an intercorporeal relationship with themselves, witnessing the change in their bodies and being forced to confront it: “Indeed, species are relationships between species–rationality is worldhood. We are not human alone – we are human with many. Matter is not immutable […] it is discursive, allowing sexes and species to practice transmaterialization” (Hayward, 2008, p. 69). The boys first experience this “human with many” as they engage with the plants and subsequently when their bodies transform.

During this transformation, Mandico’s choice to cast female actresses as the boys becomes evident. Laura Mulvey explains that for male characters, the phallus is often the object of fear, as there is an omnipresent possibility of castration:

The function of a woman in forming the patriarchal unconscious is two-fold, the first symbolizes the castration threat by her real absence of a penis and second thereby raises her child into the symbolic. … Woman’s desire is subjected to her image as bearer of the bleeding wound, she can exist only in relation to castration and cannot transcend it (Mulvey, 1999, pp. 833–834).

By possessing the ability to change the bodies of the boys, the plants retain the ability to castrate them. The plants reinforce their bodies, as well as their masculinity, being entirely mutable. However, this “cut” is the antithesis of loss. In The Wild Boys, the cut is not a taking off or an absence, but rather a generative act.

Mandico uses female actresses, individuals who never had appendages to begin with, to “recast the self through the cut body” (Hayward, 2008, p. 72). The boys’ genitalia are, like the island, entirely artificial. This prosthetic choice allows for not only a more stark physical transformation to be witnessed by the viewer but also for both the actor and viewer to experience the loss of a physical part, one that they could imagine holding in their hands: “The cut is not just an action; the cut is part of the ongoing materialization by which a transsexual tentatively and mutably becomes. The cut cuts the meat (not primarily a visual operation for the embodied subject, but rather a proprioceptive one)” (Hayward, 2008, p. 72). The “cut” of losing their genitalia produces possibility, and then this possibility is able to be fulfilled.

In order to execute this scene on actors with male genitalia, it would have required a level of tucking, binding, or at the very least visual editing. But this scene is not intended to be a scene of cutting or one of loss. By choosing actors with female genitalia, Mandico is able to materially represent the abundant change the boys have undergone. As Hayward states “To cut off the penis/finger is not to be an amputee, but to produce the conditions of physical and psychical regrowth. The cut is possibility” (Hayward, 2008, p. 72). In their bending of genders, the boys experience expansion, not contraction. Just like the material reality in which they live, the boys’ genders and genitals are not fixed. They are no longer bound by the constraints of toxic masculinity and boyhood that they were previously, but have accepted their newfound femininity. Though initially shocked by their physical transformations, the boys ultimately revel in their bodies, embracing one another and showing off their breasts. In this way, the viewer sees the polyvalent nature of their transformations. Once belligerent boys, they now reveal themselves as women. It is this subsequent growth following the “cutting” of their penises that the boys experience.

In addition to Mandico’s choice of casting female actors, he also refers to the characters as “boys” rather than men. As Jack Halberstam articulates, children are considered to be more susceptible to the wildness of nature than adults:

The potential of the wild child, … exceeds its enclosure within such systems of signification. And in the implicit ties between the unscripted nature of the infant/wild child’s desires, we can begin to understand the wildness of the child and the queerness of the animal. The wildness of the child, as for the animal, lies in its lack of susceptibility to adult human inscription — its tendency, in other words, to follow other rules and commit to other forms of life. … What I am calling wild here, then, is the part of the child/animal that resists incorporation into white and heterosexual norms (enacted through language) and that, in this resistance, calls the conventions of so- called civilized worlds into question (Halberstam, 2020, p. 145).

The wildness of nature is a site of potentiality, one in which bodies take up roles in relation to one another. It is, after all, an intentional choice to center the film on “boys” and not men. Mandico could have pursued the same plot while portraying adults, but rather he makes the distinct choice of casting boys; not only boys, but boys played by girls. Unlike men, the boys still have the potential to change and resist hegemonic order. The child, or the boy, allows the viewer to consider what queerness might be after nature as, like the wildness of the island, their transformations resist societal regulation and categorization.

Aware that this transformation is occurring, Severin is shown blissfully smoking a cigarette. Encouraging their embrace of these changes, Severin utters a quote directly from Hamlet: “There is nothing good or bad, but thinking makes it so” (1:33:30). This statement suggests that the binaries to which the boys had previously clung are no better or worse than their new forms. “You don’t want to become a woman?” Severin asks, and Tanguay replies “Do I have a choice?”

Finally, Severin reveals to the boys that the island is called Dress Island, known for its ability to transform men into women. He stumbled upon it during his research on hormonal plants, discovered the island’s powers, and convinced The Captain that the island was the “perfect method” to tame wild boys. In retelling the story, the boys say that “He [Severin] believed a feminized world would stop war and conflict” (1:35:01). Severin and the island’s work complete, the boys are finally allowed to leave, sailing back toward that from which they came.

4 More-than-human Entanglements

Though Severin was responsible for luring the boys into this realm, their transformations are due entirely to the powers of the island. The trope of men entering a wild, ripe for-colonizing island can be traced back to a long line of literary genealogy. Much like the events described in William Golding’s The Lord of the Flies, Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, or even Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the fictive interactions between plants and the human body reinforce the hegemonic masculine (Golding, 1954, Verne and McKowen, 2007, Conrad, 2007). Unlike the boys, the island and its plants exist through and beyond binaries. This ecological rejection of binaries is one that can be traced back to early modern English culture wherein the human body was understood to be affected by its environment:

Per Galenic humoralism, bodies were malleable vessels easily impacted by external stimuli and highly susceptible to the particular circumstances in which they found themselves. PreCartesian pneumatic theories, somewhat estranging to our ‘modern’ sensibilities, imagined people as participating in ecological transactions between self and world that could influence their bodies both somatically and emotionally. The possibility of ecological transaction precedes a post-Cartesian sense, one we now often take for granted, that our embodied selves are internal, individual, and nearly hermetically sealed from the world outside (Hobgood, 2016, p. 1295).

As Hobgood articulates, ecological transactions among humans and the world occurred for centuries until the anthropocene viewed itself as hermetically sealed. By breaching the boundaries of human and plant life and acknowledging the powerful effects the earth has on its inhabitants, the island’s existence disrupts not only the gender order but also the anthropocentric one. It exerts power over the boys in such a way that it changes their bodies, both physically and phenomenologically. Not only does it reject the masculinity that they clung to prior to their move to the island, but it forces them to confront the hegemonic order that they are upholding. It cannot be tamed nor rejected, and the boys ought not dare fight back.

From the moment they step foot on the island, The Wild Boys establishes the cross-species attraction between the boys and the plants. However, this attraction is monodirectional in nature; the boys extract pleasure from the island, unable to resist its advances. The island, however, does not extract anything from the boys. Acting as an Eden, it does not force this transformation upon the boys. Rather, it bides its time, passively waiting for the boys to take a bite of the apple. It is only at this point, when they succumb to their temptations, that it begins to cast its spell. Though initially unassuming, it is ultimately victorious, slyly smiling back at the boys who thought they would withstand its allure. While the anthropocene may fight back, the earth will not only fight back, but will win. This suggests not only an inevitable consequence of colonialism, but also the inevitability of a trans ecology. There is no way in which the boys may come to see the error of their ways without these bodily, and subsequently psychological and phenomenological, changes.

In this way, The Wild Boys continues a long tradition of plants subverting hegemonic order, one in which “botanical monstrosities of one sort or another invert the accustomed EuroWestern hierarchies of life to wreak havoc on the human beings who are supposed to be safely at the top of the cosmic pile” (Sandilands, 2017, p. 421). Upon their arrival on the island, the boys extract its value without concern for consequences. As The Captain instructs, they quench their thirsts and fulfill their desires. They do not imagine that the island will behave in any such way toward them. This trope is often seen in Gothic fiction wherein male characters are confronted with their own vulnerability through their interactions with plants:

The monstrous vegetation of these novels figures all of the ambiguities of threatened masculinity in ways that cannot simply be ascribed to “male dread of women’s sexual, creative, and reproductive power.” Its grasping tentacles and stupefying powers manifest the unnerving vulnerability more generally of the male body in alien locales: penetrable, futile, and impotent (McCausland, 2021, p. 500).

This grasping can literally be seen in The Wild Boys as the plants wrap their legs around the boys and catch them in a sticky trap (Figures 1 and 3). This blurring of boundaries between human and plant bodies, erection, and ejaculation, suggests that the plants might return the boys to the earth in a sort of “rebirth.” The plants are a reminder not only of the boys’ own fragile masculinity, but of the earth’s ability to overcome that which attempts to colonize it. The boys’ adventurous, masculine bodies are ultimately disposable, and eventually ought to be replaced by other forms, those that are gender fluid and mutable, like the bodies of plants.

This articulation of plants is twofold. First, it serves to demonstrate this intercorporeality, this merging of bodies that Severin encourages. Not only do the boys engage in a trans species relationship, but their bodies become trans themselves. Second, the use of plants for pleasure articulates the human extraction of the environment. While the plants do engage with the boys, it is not without motive. Their pleasuring only contributes to the greater change for which they and the island are plotting.

While the boys may extract pleasure from the island, The Captain and Severin ultimately respect the island for its powers. The Captain takes the boys to the island with the intention of taming them and does not attempt to lasso or subvert its power. He simply leads the boys to the island and lets nature, quite literally, take its course.

5 Trans Ecologies and Epistemologies

The obvious duplication of form in the plants as sex organs is not simply an aesthetic or even functional choice by Mandico. There is a substantial history in the botany of plants being characterized and defined in the same terms as human bodies, as Linnaeus brought traditional notions of gender into the realm of science and more specifically into botany:

In endowing plants with human sex, Linnaeus developed an elaborate sexual vocabulary by blurring the differences between plants and humans. He characterized plants by their reproductive parts—literal and elaborate analogies of convergence: the filaments of stamens were the vas deferens, the anthers were the testes, and pollen was the seminal fluid. In the female, the stigma was the vulva, the style the vagina, the pollen tube the fallopian tube, the pericarp the impregnated ovary, and the seeds the eggs. Others even argued that the nectar in plants was equivalent to mothers’ milk in humans (Subramaniam & Bartlett, 2023, p. 949).

Notably, in the realm of botanical taxonomical classifications, class (male) is ranked higher than order (female), “And so, the plant sciences came to inherit a sexual system modeled on “gentlemen and ladies” and their attendant botanical vocabularies of marriage: male, female, sex, gender, reproductive anatomies of male and female, sexual systems, breeding systems” (Subramaniam & Bartlett, 2023, p. 949). In this way, plants become subject to the same kind of compulsory heterosexuality enforced among humans, as if plants and humans are both subject to the same taxonomical distinctions, then they are subject to gender binaries as well. By considering the terms of normatic anthropogenic meaning, “following plants into much queerer territories of living and relating – has the potential to open life to new, “anthro-decentric” possibilities” (Sandilands, 2017, p. 426).

While they may be subject to the same taxonomical classifications, the reproductive capabilities of plants are far broader than those of humans. Many plants have the ability to self-pollinate, possessing both what would be considered “male” and “female” reproductive structures (Bondestam, 2016). Aside from pollination, there is the notion of propagation, the ability to multiply through asexual reproduction. This ability is shared by the starfish which can regenerate a lost limb by itself. In this way, plants share the same characteristics of transness that Hayward describes in her article. This ability is of course not shared by humans, and is therefore a kind of deviance from human sexuality; the ability to reproduce from within oneself is infinitely more generative than requiring a partner. Therefore, while plants may be subject to the same kind of taxonomical distinctions as humans, their generative capabilities extend far beyond the anthropocene.

In its ability to turn men into women, Dress Island itself is queer, and as such is queering the boys, their bodies, and the greater anthropocene. In understanding the island and its plants as an omnipresent force, The Wild Boys allows us to engage in a world of post-anthropocene, one that may provide a focus for epistemological positions that resist hegemonic order across plant and human bodies. Additionally, the powers of the island suggest that the earth refuses binaries of gender despite the way society does not. In this resistance, the island is victorious. Despite the attempts of the boys to retain the “masculinity” that they have conformed to, they eventually, and inevitably, submit to their metamorphoses.

In this way, plants queer standard processes of reproduction as they possess the ability to change from within themselves. The Wild Boys uses the island as a trans operation by which to stitch together bodies and environments, thereby suggesting a poetics of trans ecology from which we may focus epistemological positions. These positions contribute to the greater project of decentering the humans in our environment and additionally call the viewer to consider the way in which humans engage with other species (Cardenas, 2022). The Wild Boys calls us to consider a world of the post-anthropocene, one that resists hegemonic order across plant and human boundaries. It calls us to sit with the sticky, the deviant. We are already the fly in the trap; perhaps, we might learn something from it.

-

Author contribution: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

References

After Blue. (2021). Dir. Bertrand Mandico. Ecce Films.Search in Google Scholar

Bondestam, M. (2016). When the plant kingdom became queer: On hermaphrodites and the linnaean language of nonnormative sex. In J. Bull & M. Fahlgren (Eds.), Illdisciplined gender. Crossroads of knowledge. Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-15272-1_7.Search in Google Scholar

Cárdenas, M. (2022). Poetics of trans ecologies. JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, 61(2), 206–212. doi: 10.1353/cj.2022.0007.Search in Google Scholar

Chuh, K. (2019). The difference aesthetics makes: On the humanities “After Man”. Duke University Press.10.1215/9781478002383Search in Google Scholar

Conrad, J. (2007). Heart of darkness (R. Hampson & O. Knowles, Eds.). Penguin Classics.Search in Google Scholar

Deleuze, G. (2003). Francis Bacon: The logic of sensation (D. W. Smith, Trans.) (p. 158). Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Galt, R., & Schoonover, K. (2016). Queer cinema in the world. Duke University Press.10.1515/9780822373674Search in Google Scholar

Golding, W. (1954). Lord of the flies. Perigee.Search in Google Scholar

Halberstam, J. (2020). Wild things: The disorder of desire. Duke University Press.10.1215/9781478012627Search in Google Scholar

Hayward, E. (2008). More lessons from a starfish: Prefixial flesh and transspeciated selves. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 36(3), 64–85. Project MUSE. doi: 10.1353/wsq.0.0099.Search in Google Scholar

Hobgood, A. (2016). Prosthetic encounter and queer intersubjectivity in The Merchant of Venice. Textual Practice, 30(7), 1291–1308. doi: 10.1080/0950236X.2016.1229911.Search in Google Scholar

Huysmans, J. (2003). Against nature, (R. Baldick, Trans.). Penguin.Search in Google Scholar

McCausland, E. (2021). From the Plant of Life to the Throat of Death: Freakish flora and masculine forms in fin de siècle lost world novels. Victorian Literature and Culture, 49(3), 481–509. doi: 10.1017/S1060150319000615.Search in Google Scholar

Mulvey, L. (1999). “Visual pleasure and narrative cinema.” Film theory and criticism: Introductory readings (L. Braudy & M. Cohen Eds.), (Vol. 1999, pp. 833–844). Oxford UP.Search in Google Scholar

Sandilands, C. (2017). Fear of a queer plant? GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 23(3), 419–429. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/659881.10.1215/10642684-3818477Search in Google Scholar

She is Conann. (2023). Dir. Bertrand Mandico. Les Films Fauves and Ecce Films.Search in Google Scholar

Shildrick, M. (2009). Prosthetic performativity: Deleuzian connections and queer corporealities. In C. Nigianni & M. Storr (Eds.), Deleuze and queer theory (pp. 115–133). Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9780748634064-008Search in Google Scholar

Subramaniam, B., & Bartlett, M. (2023). Re-imagining reproduction: The queer possibilities of plants. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 63(4), 946–959. doi: 10.1093/icb/icad012.Search in Google Scholar

The Wild Boys. (2017). Dir. Bertrand Mandico. Ecce Films.Search in Google Scholar

Tompkins, K. (2017). Crude Matter, Queer Form. ASAP/Journal, 2(2), 264–268. Project MUSE. doi: 10.1353/asa.2017.0042.Search in Google Scholar

Verne, J., & McKowen, S. (2007). Journey to the center of the earth. Sterling Pub.10.1093/owc/9780199538072.003.0003Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective