Abstract

Based on the “vegetal turn” in film studies and posthuman philosophy, the article explores how experimental cinema can be a cultural mediator of vegetal forms of life. Posthumanist philosophy draws inspiration from cinema’s portrayal of both imaginary and real non-human entities as subjects and cohabitants on Earth. As subjects, these non-human entities are challenging generally accepted ideas about the principles of cognition, as well as our understanding of the causes and consequences of problems such as climate warming, Holocene extinction, and depletion of natural resources. The experimental film reveals connections between human and non-human agents through its unique film language and cinema ontology. The study examines how the film Enys Men (2022), directed by M. Jenkin, employs critical anthropomorphism to depict closely intertwined symbiotic relationships between all human and non-human agents, where memory as an embodied property connects various types of experience. In the film, access to awareness of the boundaries of life and death is challenged by non-human subjects such as lichens and Earth.

1 Introduction

Modern understanding of the boundaries between humans and non-human beings expands under the influence of scientific, philosophical, and artistic ideas. Boundaries become more flexible; relationships are described as a network of associations rather than fixed terms. Non-human agents, which can include both technology and nature, contribute to the development of a post-anthropocentric onto-epistemological perspective (Ferrando, 2019).

The research question centers on how experimental cinema functions as a cultural mediator between plant life forms, altering our understanding of the boundaries of consciousness. The perspective of onto-epistemology is considered from the standpoint of posthuman philosophy and film studies, specifically focusing on the interaction between human and non-human agents: a language of experimental cinema draws our attention to other forms of life that can contribute to expanding our understanding of the principles of knowledge.

The study of the relationship between cinema and plants as mediators of a certain type of knowledge has its history in scientific research and is actualized in the field of posthumanism, known as the “vegetal turn” (Castro et al., 2020). The examination of plants in cinema inherits the philosophical question of the connection between consciousness, matter, and motion. Aristotle puts forth the idea of the inseparability of the soul and the living body and argues for the existence of the soul in matter as an internal source of motion. According to this philosophy, the soul, as the organizing principle of living matter, is inherent not only in humans but also in plants and animals. However, the apparent immobility of plants becomes an argument against their value as lower and vegetative forms of soul, unlike humans who possess a rational soul (Aristotle, 2000). Nevertheless, Michael Marder makes a valuable observation that for Aristotle, it is precisely the plant world, or more specifically the “tree,” that becomes the primary source of the concept of pure “materiality” (hylē), this preconceptual crucial philosophical term denoting not physical material tension, but the material cause of the things (Marder, 2014). The plant form of life becomes a source of understanding the fundamental principle of material organization.

Fundamentally, the question of the presence of intelligence in plants was revised by Ch. Darwin and his son at the end of the nineteenth century, technology played an important role in this process. Inspired by the chronophotographic gun, invented by E.J. Marey, the forerunner of the cinematographic apparatus, they conducted a series of experiments and recorded the motor reactions of plants. The research results were published in the work “The Power of Movement in Plants,” which became influential and contributed to the discussion of plant intelligence and effectively was inspired by the criticism of mechanicism in the scientific circles of that time (Castro, 2019). Around the same time, under the influence of evolutionary ideas, a debate began among philosophers Théodule Ribot and Henri Bergson about the nature of human memory. Ribot argued that memory, located in a specific part of the nervous system, has a material nature (Ribot, 1881). For Bergson, memory is determined by its spiritual nature, since real perception is replaced by images of the past (Bergson, 1911). In the latter case, the difference between spirit and body changes the Cartesian spatial orientation and is determined by the temporal dimension, where the spirit is tied to the past but inhabits the body in the present time. In this perspective, consciousness is defined by the ability to see the present in light of the past. Accordingly, from Bergson’s point of view, cinema can transfer nature per se (Bergson, 2007). From this perspective, consciousness is defined by the ability to see the present in light of the past. From Bergson’s point of view, unlike humans, cinema can transmit pure duration and therefore can convey nature itself (Bergson, 2007).

Early film theorists were inspired by Bergson’s ideas in the field of the philosophy of nature and thought in the same direction. Delluc, for example, believed that the miracle of cinema is its ability to stylize without altering the truth (Delluc, 1920). For his contemporary Epstein, paradoxically, cinema discovers in the specific immobility of plants the essence of movement: a documentary on the yearly life cycle of plants reveals continuous motion imperceptible to the human eye, thus exploring reality through the lens of film and highlighting life’s movements previously unnoticed (Castro, 2019).

The idea of plant consciousness historically becomes associated with questions of memory, matter, and motion, entering into the nerve of contemporary posthumanist discussions on the pressing issues of culture.

An integral aspect of this discourse involves ecological studies and an orientation toward comprehending the entire world as a complex, self-regulating system. For researchers such as James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis, any knowledge is inseparable from the idea that it belongs to the Earth as a complex system. Lovelock proposes an original understanding of modern life on Earth in the post-anthropocentric era of “novacene”: since most life processes are mediated by technologies, and the production of machines is an integral and vitally important part of culture, humans and technologies are compelled to unite for the sake of the Earth and society as a whole (Lovelock, 2019). Margulis has made a revolution in evolutionary biology, in 1967 she changed the understanding of the relationship between living and non-living organisms. Her empirically proven concept of symbiogenesis as a driving force of evolution became widely accepted, relegating non-Darwinists and their ideas of natural selection to the past (Margulis, 1998).

In the context of highlighted topics on the limits of consciousness and the boundaries of being, the philosophy of existentialism becomes relevant for my research, specifically the exploration of fear as something deeper than just a sensitive experience in Kierkegaard and the idea of ‘being-toward-death’ in Heidegger’s thought. (Heidegger, 2001; Kierkegaard, 1980)

To analyze the film, I’ll employ a methodology combining formal analysis with Karen Barad’s concept of “agential realism.” This approach, rooted in the idea of performative interaction among agents, allows me to examine how elements within the film, the depicted plants, and human actors interact from the perspective of new materialism. Traditionally, matter is viewed in scientific discourse as a passive form, but Barad’s framework, drawing on Niels Bohr’s physics, defines matter as an active, performative force (Barad, 2003). The phenomenon of reality is the result of interaction among agents as equal but different participants in relationships. Together they create a material-discursive experience that does not arise in a world, but becomes this world (Barad, 2007). In this regard, cinema as a technological medium and plants as a life form, human experiences are intertwined by matter, expressing themselves through mutual interactions.

Teresa Castro draws attention to the fact that throughout the history of plant studies, they become closer to humans thanks to technology. She proposes the concept of the “mediated plant” and emphasizes the constancy of these relations between technology and nature, using the example of the plant world (Castro, 2019). Thus, cinema finds itself in the context of the “vegetal turn,” representing the very technology that unites us for the sake of a common prosperous future against challenges in the form of climate problems and epidemics, and becoming a mediator for plants that can function in films as non-human subjects challenging our anthropocentric ideas about life.

2 From Ecosophy to Geophilosophy

In my research, I will analyze the experimental film Stone Island (2022) (original title in the Cornish language: “Enys Men”), which is relevant for investigation in many aspects. Mark Jenkin, a film director from Cornwall and a winner of many prestigious film awards, is known for his work in cinema with an emphasis on “ecosophy” – ecological harmony. As the founder of the fundamentally eco-philosophical “Bosena” film company, Jenkin positions himself as an activist advocating for the preservation of local nature and Cornish culture, particularly the local Cornish language. His previous works shed light on the local problems of the Cornish region from the perspective of the relationship between locals and tourists, as seen in his previous film “Bait” (2019), which explores the misunderstanding between local fishermen and visitors to the island.

Local elements are also strong from a cultural–historical perspective. The plot of Stone Island finds itself in the tradition of Irish–British literature, inspired by the mixting of Catholicism as otherness in the British world and Celtic epic folklore, often filled with the motif of two touching worlds.

He strongly supports traditional filmmaking methods and uses a 16 mm Bolex camera from 1978, manually operated. He shoots on Kodak film and develops it using eco-friendly materials like baking soda, instant coffee, and vitamin C powder (Bogutskaya, 2023). This plunges him into a kind of pre-digital prison, eliminating the temptation to consume more resources (such as digital duplicates) than necessary. Additionally, this approach allows the director to consistently reduce the carbon footprint at all stages of the film production process. The director’s ideological position serves as the foundation for the content of his works and requires a corresponding revision of some consumer principles regarding the interaction between culture and nature. These characteristic features of his work align him with the geophilosophy of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, as they deterritorialize geographical and economic determinism through cinema within the geographical and material contexts of culture (Deleuze & Guattari, 1994). The experimental language of the film Enys Men creates mobile semantic structures and translates eco-oriented ideas through interaction with familiar images of nature.

In the plot, on a desolate coast near abandoned tin mines – the World Heritage Site of the Cornwall mining Industry – a female volunteer observes a rare flower enduring harsh conditions: buffeted by the cold winds of the North Sea, it struggles to cling to life on a rocky surface among mosses. Each day, her routine unfolds like a ritual, with a sequence of identical actions. She tests the temperature of the earth near the flower, then throws a stone into an abandoned mine and listens to the echo. Returning home, she records her observations, walks around the island, checks the petrol level in the generator, drinks tea, has dinner, and reads for the night the ecological manifesto A Blueprint for Survival by Edward Goldsmith and Robert Allen.

This influential work was initially published in the first issue of The Ecologist magazine in January 1972, preceding the world’s first environmental Summit at the UN Environment Conference in Stockholm. With over 750,000 copies sold, the book coincided with the time when the global community first recognized the widespread and irreversible negative human impact on the environment. The main message of the survival movement proposes building communities closer to nature, decentralized and minimally industrialized, based on the principles of tribal societies. Such communities not only promote a more careful attitude toward the environment but also positively impact the psychological well-being and physical health of their participants (Goldsmith & Allen, 1972). Thus, the film’s overt eco-oriented message unfolds within a historical context.

3 The Symbiotic Principle

The connections between the agents in the film are intentionally complicated due to the mixing of present and past in the narrative. I examine the relationships among the most frequently appearing agents: a female volunteer, a flower, lichen, other people, and elements of nature that form subplots in the narrative organization of the story.

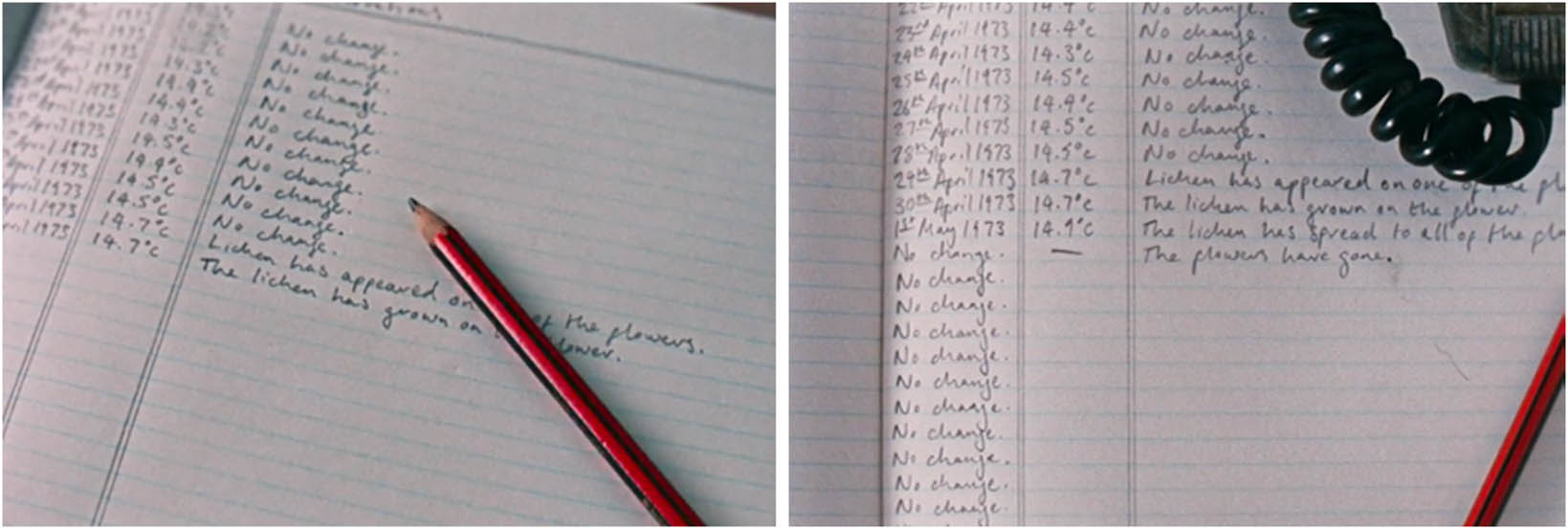

At the beginning of the film, time develops linearly: it moves without significant changes, as indicated by the entries in the diary (Figure 1a) and the monotonous cyclical events described above. A long series of actions by the heroine traces a schematic drawing of human life with access to the benefits of civilization: observing the temperature of the earth near the flower, refueling a generator with petrol, heating a stove, drinking a cup of hot tea, and listening to the radio.

(a) and (b). Entries about the time and changes.

Soon, changes occur: lichen begins to grow on the flower. Diary entries indicate that after the lichen completely catches the flower, the concept of time becomes irrelevant: the date is no longer recorded, and the words “no change” appear instead (Figure 1b). These entries illustrate two coexisting principles of temporal organization in the film: if there is a passage of time, there are no changes; if there are changes, time stops. The interaction of these principles creates a play of temporal spaces and leads to the deterritorialization of cultural patterns of perception. The absence of changes, as a persistently recurring principle, establishes the logic of repeated and ominous events in the film, which lead to the demise (“the flowers have gone”).

Another parameter recorded in the entries is the temperature, which is slowly increasing. Following Lev Kuleshov’s description of the basic effect of editing in cinema, the sequence of frames creates a story, thereby establishing a causal relationship (Kuleshov, 1929). The film narrative suggests that the reasons for the slight increase in earth’s temperature and the appearance of lichen on the flower are the usual everyday elements of civilized life associated with the operation of the generator, heating the stove, and drinking hot tea – actions that the heroine repeats from day to day between observing the flower. The leitmotif of the rising temperature is supported by the inscription “oven” above the fireplace (Figure 2a), a burning brand in a close-up shot of the fireplace (Figure 2b), and the hand of the heroine being hurt on the stove (Figure 2c). The elements are arranged to create a dual critical image of energy sources: they provide the warmth necessary for life, but heat can also be lethal. Isn’t this what frightens us in the current climate situation? The film offers a fundamental explanation for this transition from warming heat to dangerous heat, using the example of lichen’s life organization, making lichen a “mediated plant”:.

(a)–(c). The leitmotif of the high temperature.

According to the plot, the lichen spreads rapidly through the flower. This takeover is uncontrollable, and elements of horror suggest that this terrifies the female volunteer. In one scene, she examines the petals of a lichen-covered flower, then lifts her jacket and looks at the lichen that has grown on the scar on her stomach (Figure 3a and b). The woman’s body and the flower are correlated and equated with each other, as both are covered with sprouting lichen. The given idea relates to a single corporeality or a common material foundation, of which another form of life, a parasitic organism, is a part.

(a) and (b). Lichen appears on the flower and the woman’s body.

Marder writes that the plant’s immobility not only does not limit its behavioral flexibility but means that it has to carry out complex information processing to respond to the environment and thrive in it (Marder, 2023). Lichen, as an agent of frightening expanding chaos, plays a special role. It is a significant symbol of the existential experience, the key image exposing the symbiotic life as a tragic principle. A close-up of the lichen is shown from the very first frames of the film and is repeated many times long before it captures the flower. Also in the film, there is a brief frame showing the K.A. Kershaw encyclopedia on the physiology of lichens.

The vegetative mode of existence of lichen links it with a plant, it often lives among mosses, but strictly speaking, it is not a plant. It is difficult to study symbiotic organism that exists due to the fungus (mycobiont) and algae (phycobiont) components of its body. The fungus and algae mutually parasitize each other for nutrients, with the fungus exhibiting more pronounced parasitism. However, parasitism can also increase on the part of the algae when environmental conditions change. The viability of lichen as a species is determined by the balance in the coexistence of its two parts, which are of different natures. Species involved in symbiosis cannot exist in those conditions where lichen exists. Therefore, even a slight increase in the voracity of one of the species will paradoxically lead to death rather than development.

In the preface to the work “Lichen Physiology and Cell Biology” in 1985, D. Brown, the co-author of K. A. Kershaw, identifies such biological features of lichen as slow growth (0.2–0.3 mm per year) and the impossibility of controlled breeding in vitro. Lichen obtains moisture and minerals mainly from the air. It has a rapid reaction to changes in air composition and specific development in extreme habitat conditions, making them accurate indicator of negative environmental changes (Brown, 1985). These qualities of lichen allow us to reveal several important aspects of the theme of symbiosis in the context of the film. The parasitization of one agent on another turns out to be not a specific, but rather a universal life principle for the Earth.

The apparent immobility of the real lichen, which Marder writes about, is illusory. This is exposed in the film, the lichen is represented in accelerated growth, but in fact, it grows much slower. Therefore, the time in the film figuratively conveys a longer period, probably about decades. The permeability of the boundaries of the flower and the woman’s body (Figure 3a and b) eliminates the opposition of life and death. It raises the question of the symbiotic influence of some agents on others in particularly prolonged and seemingly invisible processes. The authentic existence that is possible according to Heidegger only in the borderline situation (Heidegger) is the symbiotic one in this context.

The local (a small slow-growing lichen) indicates the global (global climate change). At the same time, although the symbiosis is represented with horror techniques, the heroine does not try to somehow deal with the new life on her body, she comes to terms with it and the lichen turns out to be an image of a stable, adaptable species in the face of negative irreversible environmental changes.

Thus, the above-analyzed law of the film on the linear time linked to the immutability of connections and irreversible changes as a constant in time (Figure 1a and b) corresponds to the principle of symbiosis illustrated by lichen, where the excess life of one agent can threaten to the life of another participant in the relationship. In the logic of the new materialism, a new form arises in the interaction of various agent forms. For my research, the symbiotic principle of lichen life must be recreated through cinematic means.

The permeability of boundaries creates a prerequisite for a change in morphology: the flower dies, and the woman looks at her scars and aging body.

Lovelock mentions that the restoration of ecological balance on Earth is also difficult due to its age; form- and species-forming processes slow down like regeneration processes (Lovelock, 2019). At the same time, life alongside death appears as a kind of irreversible process of environmental cognition by living organisms.

Nevertheless, from the heroine’s perspective, it is a knowledge that is frightening. At first glance, it concerns the fear of plants, the concern that Jacobs writes about, reflecting anxiety about the relationship of man with the natural world, oneself, and others in the past, present, and future (Jacobs, 2019). Additionally, the fear awakened by horror elements (sudden power outages, images of death and blood, screams, and unexplained noises) is determined by a lack of understanding of the reasons for the lichen’s takeover of the flower and the inability to control events.

The heroine awakens with an existential experience; she experiences the type of fear described by Kierkegaard. The object that provokes fear is absent; it is hidden behind the flower. This idea of misunderstanding leads the heroine to later cut off the flower, essentially taking its life. Furthermore, we will see that the heroine is constantly asking herself a question – a question to which there is no answer, as it is directed towards the unknown, and thus, the possible answer is unknown and becomes the source of her fear. Kierkegaard’s psychological sketch The Concept of Anxiety is entirely devoted to the problem of original sin which lies at the root of fear (Angst) (Kierkegaard, 1980). Christian motifs such as the appearance of a priest and angels in the film fit into the film’s narrative in an existentialist key, where fear of original sin and sacrifice, which is essentially murder, are shown to be inevitable consequences of existence.

Fear is also determined by the frightening nature of the parasitic symbiotic process of one form of life spreading to another. Margulis writes that we humans are the result of evolution and the many complex biochemical processes of the planet; in this sense, our knowledge is the result of Earth’s thinking (Margulis, 1998). The possibility of representing the symbiotic nature of life as a frightening irreversible process of absorption (death) of one for the sake of the life of another is determined not only by the image of lichen but also by a juxtaposing montage, which becomes a conductor of the vital principle.

4 The Principle of Equality

The theme of fear remains predominant concerning the characters who emerge as ghosts of the past living in the present. According to Bergson’s view, consciousness and materiality appear as radically different and even antagonistic forms of existence that create a modus vivendi, where matter is necessity and consciousness is freedom, but life finds a way to reconcile them (Bergson, 1911). The heroine’s consciousness simultaneously inhabits the present and the past; she is limited by the body but can observe and be aware. In this context, the topic of memory tied to the body arises; it involves not only a person but also the consciousness of plants. In the film, they appear as a kind of equal agents, jointly creating a single reality in the duration of time.

The equality between the agents arises due to the nature of the film. As previously noted, the body of a woman and the body of a flower are correlated and equated with each other. This similarity is enhanced by the film’s matter, namely the identity of the sizes of all frames. Jenkin also develops the principle of comparison in color and editing. The color analogies in the film create the following connections: the heroine is almost always presented in a red jacket, and other constant red objects are a generator and red cans of petrol (Figure 4). The contents of the canister and the generator, on which it runs, are gasoline and petroleum products. In modern philosophy, oil is sometimes called the blood of the earth (Timofeeva, 2018).

The association of images with the heroine by color.

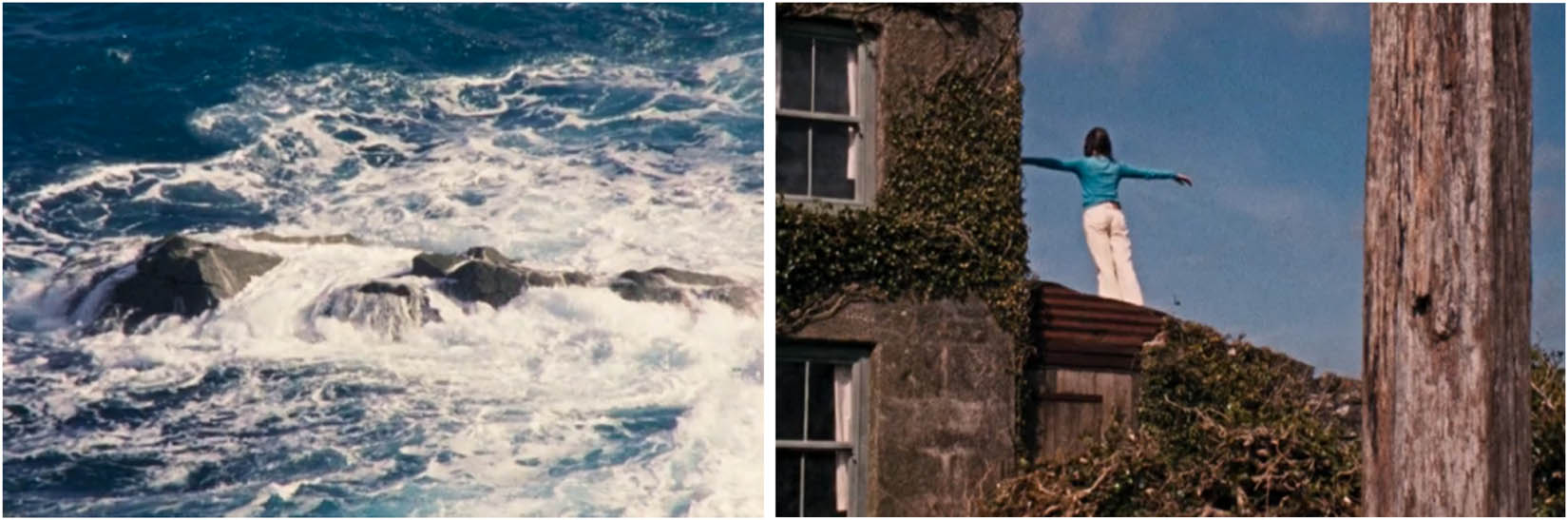

The opposite of red is sky blue, which is also associated with the woman. Almost from the very beginning of the film, a ghost coexists next to the heroine – a young girl who resembles her daughter; sometimes, they repeat the same phrases to each other, indirectly indicating that they are the same person. She is dressed in a blue sweatshirt and white pants and is associated with nature: blue sky and white clouds, blue waves, and white foam (Figure 5a and b).

(a) and (b) Images associated with the heroine in her youth by color.

In one of the last scenes, a young girl falls from a roof through glass (Figure 5b), and a cut appears on her stomach; on the body of an adult woman, it is already shown as a scar. The fall appears as a trauma that irreversibly disfigures the body and creates a symbolic boundary, after which, probably, the woman no longer feels young. Two oppositely colored (red and blue) images are connected. A young girl is portrayed as a victim of an accident or carelessness. The image of a focused middle-aged woman in red is also associated with nature, but this is exploited nature, as oil turned into a resource, the fuel for civilization in a red canister and generator. An old scar overgrown with lichen also indicates the decomposition process. Nevertheless, both women remain connected, as they represent the same consciousness but at different ages.

The editing illustrates that all objects in the film are interconnected and can peer into each other. The heroine can look at the mine (Figure 6a), and the abandoned mine, into which she throws a stone, also looks at her – the reverse point of shooting from the side of the mine is given to the volunteer’s face (Figure 6b). The question “Who are you?”, which sounds several times in the film, is an existential question, turned to the boundary as if everything in the world of the film is a single consciousness trying to understand its nature.

(a) and (b) The reverse angle from the volunteer and the mine.

One of the central images of the film, a memorial of the deceased people near the island, is also compared with the heroine. The image of a woman is saturated with multiple comparisons and encompasses all the objects of the film’s world. Thus, she is portrayed as Gaia the Earth and a simple person, an integral part of the Earth, observing what is happening on the island. Combining the image of the Earth and the image of a woman’s daily life with personal memories correlates the pain of a person from loss with the damage from the loss of living species on a global scale. The memories of seven miners who died in the mine (a reference to Cornish myth about mystical underground creatures known as “knockers”), seven rescuers who died in the storm, and seven maids are compared with the threat to the lives of seven flowers watched by a volunteer (Figure 7). The “mediated plant,” a rare flower, acquires a semantic connotation of a victim, a source and resource, a servant, and an angelic creature.

(a)–(e) Numerical comparison.

The repetitive motif of the number seven closes with the image of angels (Figure 7d), perfect creatures. In addition to the important role that seven plays in fairy tales and Christianity, seven refers to the ideal number (Liabenow, 2014), probably partly due to the seven days during which the Earth was created. In the context of the film, the recurring figures forming the number seven are always inaccessible and ghostly, indicating the loss of an ideal state, and the inaccessibility and fragility of perfection.

One of the detailed subplots of the film is the death of a boatman who brings petrol. He drowns, and the woman sees herself taking out his drowned body. The lamentation of the drowned man resonates with a similar motif in J.M. Synge’s play Riders to the Sea, which also references elements of Celtic paganism with its characters’ fear of the supernatural forces of nature, despite considering themselves part of the Catholic faith. In Enys men, the complex relationship between humans and nature is revealed through a comparison: a cut flower and a drowned one are compared with each other (Figure 8). These are equivalent losses in the film.

The plot parallel of the flower – man.

Margulis writes that our knowledge is the knowledge of the Earth about ourselves, just as we are a continuation of integral consciousness and thinking about the Earth (Margulis, 1998). The paradox of the climate problem and anthropogenic extinction, illustrated by the film, is that, in reality, the Earth, as a planet and nature as a whole, did not pluck a flower, but it did so by human hands. The frightening trauma portrayed in the film is the memory of loss. An indication of the equal mutual influence between man and the Earth through several artistic fields at once (the nature of the film, editing, color, and compositional numerical repetition of figures) indicates entanglements and interdependence and returns to the theme of symbiosis, the principle of which can be translated through technologies such as cinematography. The material medium, 16-mm film, on which the director shoots, emphasizes an embodied nature for different forms of knowledge. The woman in the film depends on the availability of electricity, as well as the availability of natural resources in the mine. The earth depends on how a person will handle it, which is indicated by the elements of abandoned traces of civilization immersed in the matter: a rusty mine, abandoned rails, parts of a trolley and wheels, wreckage of a boat, the same as a lichen in the wound of the heroine. Just as a woman is left without electricity and hot water in her ruined house, the Earth is crippled by people exploiting it.

5 Communication Aspect

The described objects in the film coexist in an inseparable connection, where the parasite and the victim cyclically change places. Margulis writes that the Earth communicates by itself (Margulis, 1998). The first shots of the film contrast the intense noise of a transmitter in the house and the relaxed sounds of nature outside. The sounds of culture and nature are in dissonance and reflect the main problem of the film – broken communication in an inseparable connection, which becomes destructive (Figure 9).

The problem of communication in the images of the film.

The woman periodically communicates functionally on the radio: “Everything is fine,” “I’m here to observe,” and “Everything is fine, but the petrol is out.” Meanwhile, the radio in the house broadcasts news about the collective grief of the rescuers who died in the storm. Irreversible loss becomes the norm, a part of everyday life.

In the scene where the boatman, who brought the gasoline, asks about the plucked flower, the radio transmitter repeats the international distress signal “Mayday” during their short dialogue. Despite numerous warnings, the disaster signal remains unheard. Seven rescuers appear in the frame, whose deaths were reported by the radio in previous scenes. After this scene, night falls, and seven flowers, which were watched by a volunteer, disappear into it.

The motif of the unheard message is repeated over and over again, always leading to the theme of loss and hope embodied in the form of a memorial monument to the victims of the tragedy. The stone memorial in its special form of existence returns to the theme of corporeality.

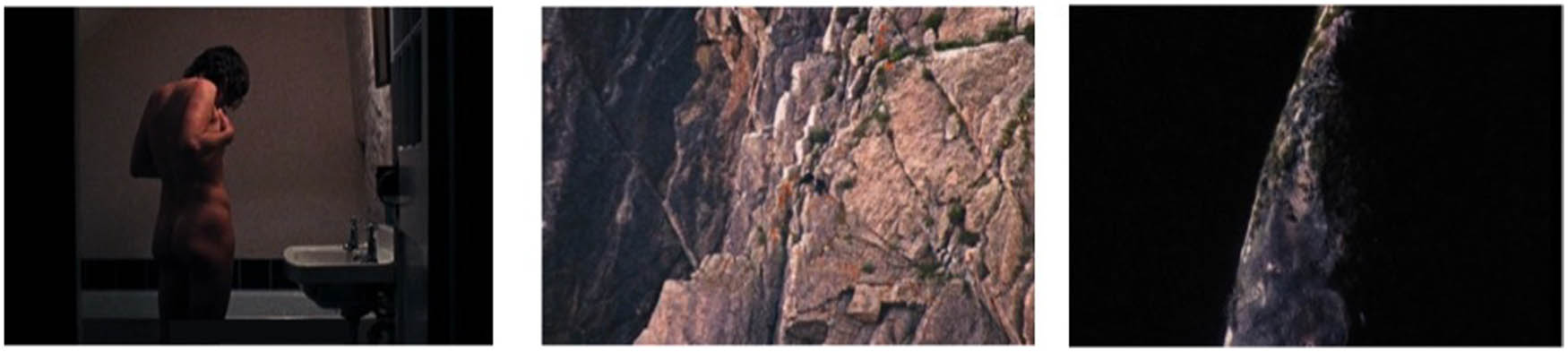

Subjectivity is embodied, thus consciousness also ages, and memory, as embodied memory, hardens. The scarred female body and the memorial are also correlated and equated with each other (Figure 10). Therefore, the stone becomes an image of embodied trauma, reflecting the inability to change the past. In this scene in the dim light bathroom, where the naked heroine contemplates her scar, on which lichen is growing, an intimately close existential dimension emerges, accessible, according to Heidegger, only through intuitive cognition (Heidegger, 2001).

The female body and the stone comparison in the film editing.

The motif of the unheard message and mourning culminates in the summaries of the broadcasts about the memorial and the storm, which the volunteer listens to inattentively. It is the message about the losses that should be the signal to prevent them, but unfortunately, it does not work. It is a vicious circle that frightens the heroine. The compressed time of the film illustrates how the past always accompanies us in the present, and the actions and events remain with us.

The way lichen exists, seemingly immobile, as Michael Marder would point out, brings us back to discussing what the plant can tell us about ourselves. Like lichen, we live as parasites in a symbiosis with all living beings on the planet; we give much less than we take. Lichen reminds us that by disrupting the balance, we most likely will not survive for long or will be forced to adapt to changes like lichens, and the Earth will no longer be as beautiful as we draw it in idealized images.

6 Conclusion

In my analysis, I consider how “mediated plants” lichens, and flowers in the film offer a unique perspective on the relationship between humans and the environment. Through the cinema ontology, the symbiotic life principle of lichens takes on an artistic form in spatial-narrative and visual expression and reveals it both in relations with humans and in the interaction of all agents on Earth as a whole. The film’s conscious ecocriticism, rooted in the historical and cultural context of the Cornish Peninsula, performs geophilosophy in action, where local and global perspectives intersect, forming a single knowledge.

The analysis of the film materials also demonstrates that the local tradition of blending Christian and Cornish folklore motifs adapts to the logic of posthumanism. The authenticity of existence is conveyed through non-human subjects which are interconnected in the film as various images of Gaia being (from lichens to stones). While the film evokes an alarmist sentiment regarding climate change, it also prompts viewers to consider their responsibility in addressing it.

The relationships depicted among characters, flora, and symbolic images are made through editing and color connections. The interwoven of the participants with each other indicates the kinship of the dramatic principle to the vital relations from the point of view of the modern theory of posthumanism and expands the idea of the material-discursive role of cinema as a mediator of modern culture. In this context, the phenomenology of cinema approaches the theory of posthumanism, and the preference for such a material medium for a film as the 16-mm film returns to the pre-digital era and concerns about ignoring the material dimension.

On-screen posthuman subjectivity goes beyond mere depiction, delving into embodiment where matter and memory intertwine. Through mediated lichens, the film illustrates the inevitability of aging and mortality, from small symbiotic species to humanity and beyond, reflecting on the broader concept of Gaia.

-

Author contribution: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

References

Aristotle. (2000). On the soul. Parva Naturalia. On breath. Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(3), 801-831. doi: 10.1086/34532.Search in Google Scholar

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bergson, H. (1911, October). Life and consciousness. Hibbert Journal, 10, 1–23.Search in Google Scholar

Bergson, H. (2007). Creative evolution. Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Bogutskaya, A. (2023). Mark Jenkin — The analog filmmaker takes us through his most-treasured tools// We present by we transfer. Retrieved April 28, 2024, from https://wepresent.wetransfer.com/stories/mark-jenkin-analog-film-essentials.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, D. H. (1985). Introduction. In D. H. Brown (Ed.), Lichen physiology and cell biology (pp. v–vii). Plenum Press.Search in Google Scholar

Castro, T. (2019, September). The mediated plant. E-flux Journal. 102, 1–10. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.e-flux.com/journal/102/283819/the-mediated-plant/.Search in Google Scholar

Castro, T., Pitrou, P., & Rebecchi, M. (2020). Puissance du Végétal et Cinéma Animiste: La Vitalité Révélée par la Technique. France Les Presses du Réel.Search in Google Scholar

Deleuze, J., & Guattari, F. (1994). What is philosophy? Columbia University Press. Retrieved March 10, 2024, from https://transversalinflections.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/deleuze-3207-what_is_philosophy-fenomenologie-van-schilderkunst.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Delluc L. (1920). Photogenie. M. de Brunoff.Search in Google Scholar

Ferrando F. (2019). Philosophical posthumanism. Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Goldsmith, E., & Allen, R. (1972). A blueprint for survival. Ecologist Journal, 1, 8–17. Retrieved March 15, 2024, from https://web.archive.org/web/20090831193545/http://www.theecologist.info/key27.html.Search in Google Scholar

Heidegger, M. (2001). Being and time. MPG Books. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from https://altair.pw/pub/lib/Martin%20Heidegger%20-%20Being%20and%20Time%20(translated%20by%20Macquarrie%20&%20Robinson).pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, J. (2019). Phytopoetics: Upending the passive paradigm with vegetal violence and eroticism. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 5(2), 1–18.Search in Google Scholar

Kierkegaard, S. (1980). The concept of anxiety: A simple psychologically orienting deliberation on the dogmatic issue of hereditary sin. Princeton University Press. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from https://archive.org/details/conceptofanxiety0000kier.Search in Google Scholar

Kuleshov, L.V. (1929). Iskusstvo Kino. Tea-Kino-Pechat’.Search in Google Scholar

Liabenow, A. (2014). The Significance of the numbers three, four, and seven in fairy tales, folklore, and mythology. Honors Projects, 418, 1–28. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects/418.Search in Google Scholar

Lovelock, J. (2019). Novacene. The coming age of hyperintelligence. Penguin Books.Search in Google Scholar

Marder, M. (2014).The philosopher’s plant: An intellectual herbarium. Aristotle wheat (chapter 2), Avicenna’s celery (chapter 5). Columbia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Marder, M. (2023).Vegetal entwinements in philosophy and art. MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Margulis, L. (1998). The symbiotic planet: A new look at evolution. Phoenix.Search in Google Scholar

Ribot, Th. (1881). Les maladies de la mémoire. Baillière.Search in Google Scholar

Timofeeva, O. (2018). Black matter. In M. Kramar, & K. Sarkisov (Eds.), Experiences in inhuman hospitality: An anthology. M.: V-A-C Press.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective