Abstract

The monoclinic lithium platinum selenide Li2Pt3Se4 was obtained via a multianvil high-pressure/high-temperature route at 8 GPa and 1200°C starting from a stoichiometric mixture of lithium nitride, selenium, and platinum. The structure of the ternary alkali metal-transition metal-selenide was refined from single-crystal X-ray diffractometer data: P21/c (no. 14), a=525.9(2), b=1040.6(2), c=636.5(2) pm, β=111.91(1)°, R1=0.0269, wR2=0.0569 (all data) for Li2Pt3Se4. Furthermore, the isostructural mineral phases jaguéite (Cu2Pd3Se4) and chrisstanleyite (Ag2Pd3Se4) were reinvestigated in their ideal stoichiometric ratio. The syntheses of the mineral phases were also carried out under multianvil conditions. Single-crystal data revealed a hitherto not described structural disorder of the transition metal atoms.

1 Introduction

In 2004, Paar [1] reported the discovery of a new mineral with the simplified formula Cu2Pd3Se4 (jaguéite) in a telethermal selenide vein-type deposit at the El Chire prospect. This mineral is a copper analog of Ag2Pd3Se4 (chrisstanleyite) [2], and in general, the two minerals occur associated and partially intergrown. Electron microprobe analyses of natural jaguéite (Cu1.9Ag0.1Pd3Se4), and chrisstanleyite (Ag1.6Cu0.4Pd3Se4) revealed a substitution of about 5% of copper atoms by silver, and of 20% silver atoms by copper, respectively. Their crystal structures were determined by Topa [3], exhibiting a new monoclinic structure type with palladium in a square planar selenium coordination. Systematic investigations of phase relations with the prospect of new compounds in the system Ag– Pd–Se were performed by Vymazalová [4]. Besides Ag2Pd3Se4, three other phases (AgPd3Se [5], (Ag,Pd)22Se6 [6], and Ag6Pd74Se20 [4]) were reported in the temperature range from 350 to 530°C. In the system Cu–Pd–Se, jaguéite (Cu2Pd3Se4) is the hitherto only representative.

In addition to these studies, we have investigated the A2M3X4 chalcogenides under high-pressure/high-temperature conditions, and have synthesized isostructural sulfide compounds containing lithium as A, Pd/Pt as M, and sulfur as X atoms for the first time [7]. Because of their variety of crystal structures and physical properties like magnetism, metal-insulator transitions [8], superconductivity [9], or magnetoresistance [10], [11], metal-rich chalcogenides [12], [13], [14] have attracted considerable interest in solid state chemistry, physics, and material science during the last decades. Ternary lithium-transition metal-chalcogenides are mainly known for the early d-block elements. Generally, they form layered structure types with intercalated lithium atoms, potentially attractive for application as lithium ion-conducting materials [15], [16], [17]. In contrast, the jaguéite structure type of the title compound is an open framework structure and solid state 7Li NMR experiments on the compounds Li2(Pd,Pt)3S4 showed no mobility of the lithium atoms inside the channels [7].

In this contribution, we focused on the corresponding lithium platinum selenide, Li2Pt3Se4. Furthermore, we reinvestigated the isostructural mineral phases jaguéite (Cu2Pd3Se4) and chrisstanleyite (Ag2Pd3Se4) in their ideal stoichiometric ratio. Here, we present the syntheses and the crystal structures of Li2Pt3Se4, Ag2Pd3Se4, and Cu2Pd3Se4.

2 Experimental

2.1 High-pressure/high-temperature syntheses

Starting materials for the multianvil high-pressure/high-temperature synthesis of Li2Pt3Se4, according to Eq. 1, was a stoichiometric mixture of Li3N (purity >99.4%, Alfa Aesar), platinum sponge (purity >99.8%, Strem Chemicals, Inc.), and selenium powder (purity >99.9%, Fluka). Similarly, for syntheses of the isostructural compounds A2Pd3Se4 (A=Ag, Cu), according to Eq. 2, stoichiometric mixtures of silver powder (purity >99.9%, Strem Chemicals, Inc.) or copper powder (purity >99%, Sigma Aldrich) in combination with palladium powder (purity >99.95%, Strem Chemicals, Inc.) and selenium powder (purity >99.9%, Fluka) were used.

The mixtures of the starting materials were milled and loaded into 18/11-assembly crucibles made of hexagonal boron nitride (HeBoSint® P100, Henze BNP GmbH, Kempten, Germany). Because of the air and moisture sensitivity of lithium nitride required for the synthesis of Li2Pt3Se4, it was essential to prepare the assembly under inert gas atmosphere. To compress the walker module of the press up to the desired pressure of 8 GPa, 210 min were necessary. After reaching the synthesis pressure the samples were heated to 1200°C within 15 min, kept constant for 10 min and were gently cooled down for the next 2 h to 500°C, followed by quenching the samples to room temperature. This annealing process under pressure can improve the crystallinity of the samples. After finishing the decompression process of the press, the samples could be easily separated from the surrounding assembly materials and no reaction with the crucible material was observed. Further information about the technique and the construction of the different assemblies can be found in numerous references [18], [19], [20], [21]. The polycrystalline samples were stable in air and appeared silvery with metallic lustre. By milling, they turned into dark gray powders.

2.2 X-ray diffraction and data collections

Characterization of the polycrystalline high-pressure samples was performed by powder diffraction on a stoe Stadi P diffractometer with (111)-curved Ge-monochromatized MoKα1 radiation (λ=70.93 pm) in transmission geometry. The powdered samples were mounted between acetate films and fixed with high-vacuum grease. The diffraction intensities were collected by a Dectris Mythen2 1K microstrip detector with 1280 strips.

Based on the parameters derived from the single-crystal structure model, Rietveld refinement of Li2Pt3Se4 was done with the Diffracplus-Topas® 4.2 software package (Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany). Instrument contributions were taken into account by using a measured instrument function for reflection profiles. Peak shapes were modeled using modified Thompson–Cox–Hastings pseudo-Voigt profiles [22], [23]. The background was fitted with Chebychev polynomials up to the 12th order. The lattice parameters derived from the Rietveld refinement agree well with those obtained from the single-crystal data (see Table 1). Figure 1 shows the result of the Rietveld refinement of Li2Pt3Se4. Elemental platinum [26], PtSe2 [27], and Pt5Se4 [28] were always present in different amounts as by-products. The bulk samples of Ag2Pd3Se4 and Cu2Pd3Se4 from high-pressure experiments indicated a low degree of crystallinity, and powder refinements resulted in no precise lattice parameters. Nevertheless, some single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were identified inside the bulk samples.

Crystal data and structure refinements of Li2Pt3Se4 and the isostructural compounds Ag2Pd3Se4 and Cu2Pd3Se4.

| Li2Pt3Se4 | Ag2Pd3Se4 | Cu2Pd3Se4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molar mass, g·mol−1 | 914.99 | 850.78 | 762.12 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/c (no. 14) | P21/c (no. 14) | P21/c (no. 14) |

| Cell formula units | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Powder diffractometer | STOE Stadi P | ||

| Radiation | MoKα1 (λ=70.93 pm) | ||

| Powder data | |||

| a, pm | 525.60(2) | ||

| b, pm | 1039.94(3) | ||

| c, pm | 636.12(2) | ||

| β, deg | 111.92(3) | ||

| V, Å3 | 322.55(2) | ||

| Single-crystal diffractometer | Nonius Kappa CCD | Bruker D8 Quest | Nonius Kappa CCD |

| Radiation | MoKα (λ=71.073 pm) | MoKα (λ=71.073 pm) | MoKα (λ=71.073 pm) |

| Single-crystal data: | |||

| a, pm | 525.9(2) | 563.46(3) | 563.8(2) |

| b, pm | 1040.6(2) | 1039.89(6) | 986.6(2) |

| c, pm | 636.5(2) | 637.72(4) | 624.3(2) |

| β, deg | 111.91(3) | 115.103(2) | 115.40(3) |

| V, Å3 | 323.1(2) | 338.37(3) | 313.7(2) |

| Calculated density, g·cm−3 | 9.40 | 8.35 | 8.07 |

| Crystal size, mm3 | 0.04×0.02×0.01 | 0.015×0.024×0.063 | 0.04×0.03×0.03 |

| Absorption coefficient, mm−1 | 87.2 | 34.9 | 38.2 |

| F(000), e | 752 | 736 | 664 |

| Detector distance, mm | 36 | 40 | 36 |

| θ range, deg | 3.9–32.47 | 3.92–32.43 | 4.00–32.50 |

| Range in hkl | ±7, ±5, ±9 | ±8, ±15, ±9 | ±8, ±14, ±9 |

| Total no. reflections | 4481 | 12 566 | 4330 |

| Data/ref. parameters | 1168/44 | 1221/54 | 1142/54 |

| Reflections with I>2 σ(I) | 1118 | 1161 | 1104 |

| Rint/Rσ | 0.0602/0.0386 | 0.0332/0.0159 | 0.0435/0.0314 |

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan [24] | Multi-scan [25] | Multi-scan [24] |

| Goodness-of-Fit on F2 | 1.156 | 1.120 | 1.296 |

| R1/wR2 for I>2 σ(I) | 0.0246/0.0562 | 0.0325/0.0712 | 0.0460/0.1000 |

| R1/wR2 for all data | 0.0269/0.0569 | 0.0350/0.0721 | 0.0482/0.0994 |

| Extinction coefficient | 0.0022(2) | 0.0037(3) | 0.0037(5) |

| Largest diff. peak/hole, e·Å−3 | 3.77/–2.10 | 3.53/–2.14 | 2.51/–2.17 |

Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

By mechanical fragmentation, several irregularly shaped silvery crystals were isolated from the crushed samples treated under high-pressure/high-temperature conditions. For better handling, the crystal fragments were embedded in perfluoropolyalkylether (viscosity 1800 cSt) and fixed on thin glass fibers with high-vacuum grease. The intensity data collections of the Cu2Pd3Se4 and Li2Pt3Se4 crystals were carried out on a Nonius Kappa-CCD diffractometer with graphite-monochromatized MoKα radiation (λ=71.07 pm) at room temperature. The program Scalepack [24] was used to correct the intensity data for absorption based on equivalent and redundant intensities. For the Ag2Pd3Se4 single-crystal data collection, a Bruker D8 Quest diffractometer with a Photon 100 detector system and an Incoatec Microfocus source generator (multi layered optics-monochromatized MoKα radiation, λ=71.07 pm) was used. Collection strategies, concerning ω and ϕ scans, were optimized with the Apex-2 program package [25], resulting in data sets of complete reciprocal spheres up to high angles with high completeness. Reflection intensities were integrated with the program Saint [25] using a narrow-frame algorithm and corrected for absorption effects with the program Sadabs [25], based on the semi-empirical multi-scan approach. Table 1 summarizes the experimental details.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structure refinements

For all three compounds the systematic extinctions h0l with l≠2n, 0k0 with k≠2n, and 00l with l≠2n were evident and led to the space group P21/c (no. 14). The initial positional parameters were deduced from an automatic interpretation of Direct Methods with Shelxs-2013 [29], and the following full-matrix least-squares refinements on F2 were performed with Shelxl-2013 [30], [31]. In the case of Li2Pt3Se4, the positional parameters of the isostructural compound Li2Pt3S4 [7] were used as starting values for the structure refinement. To verify the correct compositions of Li2Pt3Se4, Cu2Pd3Se4, and Ag2Pd3Se4, all occupancy parameters were refined in separate series of least-squares cycles. All sites were fully occupied within two standard deviations. Furthermore, all sites were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters, but only for Li2Pt3Se4 the final Fourier synthesis did not reveal any significant residual peaks (see Table 1). The positional parameters as starting values for the refinement of Ag2Pd3Se4 were derived from Cu2Pd3Se3 with the Cu+ position taken for Ag+. A refinement of a possible mixed occupation of Pd sites with Cu or Ag resulted in higher R values even if, in the case of Ag2Pd3Se4, there are only slight differences in the scattering factors of Ag+ and Pd2+. Moreover, geometrical aspects, which will be discussed later, are in favor of a clear distinction between Pd2+ sites on the one hand and Cu+ or Ag+ sites on the other.

The refinements of the synthetic mineral phases Cu2Pd3Se4 and Ag2Pd3Se4 exhibited considerable residual peaks in distances of 0.65(5) Å from the Cu1, Ag1, and Pd1 sites. As a consequence, a split-atom model of the Cu1 and Pd1 sites in Cu2Pd3Se4 as well as of the Ag1 and Pd1 sites in Ag2Pd3Se4, was evident in separate difference-Fourier syntheses. The additional split sites were refined with isotropic displacement parameters. Due to high correlation factors, refinements with anisotropic displacement parameters were not reasonable. The splitting of the sites in Ag2Pd3Se4 was about twice as pronounced as in Cu2Pd3Se4. About 10% of the Ag1 and Pd1 atoms of Ag2Pd3Se4 occupy additional split sites, whereas in Cu2Pd3Se4 about 5% of Cu1 and Pd1 are distributed over two positions. Without refinement of the split positions, the R values of Ag2Pd3Se4 and Cu2Pd3Se4 are R1=0.0685/wR2=0.1704 and R1=0.0654/wR2=0.1441, respectively. A refinement including the split positions resulted in considerably better R values of R1=0.0325/wR2=0.0721 for Ag2Pd3Se4 and R1=0.0460/wR2=0.1000 for Cu2Pd3Se4. Final Fourier syntheses revealed negligible residual peaks in distances of 0.70(2) Å next to Se1 and Se2. A refinement of other split positions was neglected. Non-merohedral twinning as a possible reason for the structural disorder was checked carefully but no evidence could be found. Small epitaxially grown crystals, which could be indexed with Cell_Now [25], are in our opinion not the reason for the observed structural disorder as their scattering intensity contributed only about 1% to the total scattering of the main component. Details of the single-crystal structure measurements are shown in Table 1, and the positional parameters (Table 2), anisotropic displacement parameters (Table 3), interatomic distances, and angles (Tables 4 and 5) are listed additionally.

Atomic coordinates and isotropic equivalent displacement parameters Ueq (Å2) for Li2Pt3Se4, Ag2Pd3Se4, and Cu2Pd3Se4 (space group: P21/c, Z=2).

| Atom | Wyckoff-Position | sof | x | y | z | Ueq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li2Pt3Se4 | ||||||

| Pt1 | 4e | 1 | 0.26919(5) | 0.37126(2) | 0.02280(4) | 0.00643(9) |

| Pt2 | 2a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00642(9) |

| Se1 | 4e | 1 | 0.0310(2) | 0.31004(6) | 0.2767(1) | 0.0066(2) |

| Se2 | 4e | 1 | 0.4728(2) | 0.05395(6) | 0.2560(2) | 0.0070(2) |

| Li | 4e | 1 | 0.615(3) | 0.301(2) | 0.461(2) | 0.020(3) |

| Ag2Pd3Se4 | ||||||

| Pd1a | 4e | 0.916(6) | 0.2615(2) | 0.12506(7) | 0.5063(2) | 0.0103(2) |

| Pd1b | 4e | 0.084(6) | 0.167(3) | 0.103(1) | 0.471(2) | 0.017(2) |

| Ag1a | 4e | 0.902(5) | 0.6299(2) | 0.19673(8) | 0.9827(2) | 0.0183(2) |

| Ag1b | 4e | 0.098(5) | 0.547(2) | 0.2248(8) | 0.992(2) | 0.018(2) |

| Pd2 | 2a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0111(2) |

| Se1 | 4e | 1 | 0.0467(2) | 0.31729(6) | 0.2637(2) | 0.0127(2) |

| Se2 | 4e | 1 | 0.4665(2) | 0.05206(6) | 0.2549(2) | 0.0126(2) |

| Cu2Pd3Se4 | ||||||

| Pd1a | 4e | 0.953(6) | 0.2561(2) | 0.12684(9) | 0.4986(2) | 0.0112(3) |

| Pd1b | 4e | 0.047(3) | 0.154(6) | 0.089(3) | 0.472(4) | 0.028(6) |

| Cu1a | 4e | 0.95(2) | 0.6148(8) | 0.1928(4) | 0.9799(3) | 0.0225(7) |

| Cu1b | 4e | 0.05(2) | 0.54(1) | 0.227(5) | 0.972(4) | 0.012(8) |

| Pd2 | 2a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0115(2) |

| Se1 | 4e | 1 | 0.0134(2) | 0.3137(2) | 0.2359(2) | 0.0123(2) |

| Se2 | 4e | 1 | 0.4706(2) | 0.0552(2) | 0.2420(2) | 0.0126(2) |

Ueq is defined as one third of the trace of the orthogonalized Uij tensor. Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Anisotropic displacement parameters (Å2) for Li2Pt3Se4, Ag2Pd3Se4, and Cu2Pd3Se4 (space group: P21/c, Z=2).

| Atom | U11 | U22 | U33 | U23 | U13 | U12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li2Pt3Se4 | ||||||

| Pt1 | 0.0073(2) | 0.0060(2) | 0.0071(2) | –0.00011(7) | 0.00390(9) | –0.00081(7) |

| Pt2 | 0.0067(2) | 0.0059(2) | 0.0075(2) | 0.0004(2) | 0.0037(2) | –0.00023(9) |

| Se1 | 0.0075(3) | 0.0060(2) | 0.0074(3) | –0.0003(2) | 0.0042(2) | 0.0003(2) |

| Se2 | 0.0074(3) | 0.0066(2) | 0.0079(3) | 0.0005(2) | 0.0040(2) | 0.0005(2) |

| Li | 0.017(6) | 0.030(7) | 0.014(6) | 0.004(5) | 0.005(5) | 0.013(5) |

| Ag2Pd3Se4 | ||||||

| Pd1a | 0.0144(5) | 0.0100(3) | 0.0079(3) | 0.0012(2) | 0.0060(3) | 0.0028(3) |

| Ag1a | 0.0169(4) | 0.0149(3) | 0.0223(3) | –0.0031(2) | 0.0079(2) | –0.0029(3) |

| Pd2 | 0.0162(3) | 0.0085(3) | 0.0100(3) | –0.0004(2) | 0.0073(2) | –0.0022(2) |

| Se1 | 0.0203(3) | 0.0096(3) | 0.0114(3) | 0.0013(2) | 0.0100(2) | 0.0032(2) |

| Se2 | 0.0176(3) | 0.0120(3) | 0.0098(2) | 0.0020(2) | 0.0072(2) | 0.0026(2) |

| Cu2Pd3Se4 | ||||||

| Pd1a | 0.0132(4) | 0.0137(4) | 0.0076(3) | 0.0010(2) | 0.0054(3) | 0.0027(3) |

| Cu1a | 0.019(2) | 0.022(2) | 0.0271(8) | –0.0035(6) | 0.0112(6) | –0.004(2) |

| Pd2 | 0.0125(4) | 0.0143(4) | 0.0081(4) | 0.0007(3) | 0.0049(3) | –0.0013(3) |

| Se1 | 0.0144(4) | 0.0147(4) | 0.0090(4) | 0.0001(3) | 0.0060(3) | 0.0012(3) |

| Se2 | 0.0134(4) | 0.0164(4) | 0.0088(4) | 0.0017(3) | 0.0055(3) | 0.0019(3) |

Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Interatomic distances (pm) of Li2Pt3Se4, Ag2Pd3Se4, and Cu2Pd3Se4.

| Li2Pt3Se4 | Ag2Pd3Se4 | Cu2Pd3Se4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt1: | Se2 | 244.8(1) | Pd1a: | Pd1b | 53.5(1) | Pd1a: | Pd1b | 64.4(1) | |||

| Se2 | 245.2(1) | Se2 | 246.0(1) | Se1 | 245.7(2) | ||||||

| Se1 | 246.9(1) | Se2 | 246.6(1) | Se2 | 246.6(2) | ||||||

| Se1 | 247.3(1) | Se1 | 249.1(1) | Se1 | 248.0(2) | ||||||

| Li | 268.8(17) | Se1 | 250.3(1) | Se2 | 248.8(2) | ||||||

| Li | 279.8(13) | Ag1b | 227.1(1) | Cu1b | 222.5(1) | ||||||

| Pt2: | Se1 | 247.5(1) | 2× | Ag1a | 283.4(2) | Cu1a | 273.4(5) | ||||

| Se2 | 247.6(1) | 2× | Ag1a | 295.7(2) | Cu1b | 286.9(1) | |||||

| Li | 283.9(17) | 2× | Ag1b | 300.5(1) | Cu1a | 288.6(2) | |||||

| Li: | Se1 | 262.3(13) | Ag1a: | Ag1b | 57.6(1) | Cu1a: | Cu1b | 51.4(1) | |||

| Pt1 | 268.8(17) | Se1 | 259.4(1) | Se1 | 243.8(2) | ||||||

| Se2 | 272.2(14) | Se2 | 273.5(1) | Se2 | 251.4(2) | ||||||

| Pt2 | 283.9(17) | Se2 | 293.0(2) | Se2 | 275.1(4) | ||||||

| Se1 | 284.2(15) | Se2 | 294.1(2) | Se2 | 283.0(4) | ||||||

| Se2 | 292.5(15) | Se1 | 297.9(2) | Se1 | 306.4(2) | ||||||

| Li | 335.6(10) | 2× | Se1 | 320.5(2) | Se1 | 321.1(1) | |||||

| Pd1b | 331.4(1) | Pd1b | 328.4(2) | ||||||||

| Pd1b | 334.5(1) | Pd1b | 335.7(1) | ||||||||

| Pd1b: | Se1 | 238.9(8) | Pd1b: | Se1 | 232(2) | ||||||

| Se1 | 253.2(8) | Se2 | 254(2) | ||||||||

| Se2 | 261.9(10) | Se1 | 259(2) | ||||||||

| Se2 | 264.6(10) | Se2 | 275(3) | ||||||||

| Ag1b | 275.1(9) | Cu1b | 285(8) | ||||||||

| Ag1b | 334.7(9) | Cu1b | 324(6) | ||||||||

| Ag1b: | Se1 | 260.2(9) | Cu1b: | Se2 | 252(4) | ||||||

| Se2 | 262.4(6) | Se2 | 255(3) | ||||||||

| Se2 | 270.1(7) | Se1 | 259(4) | ||||||||

| Se1 | 277.9(8) | Se1 | 273(4) | ||||||||

| Se2 | 326.7(7) | Se2 | 307(6) | ||||||||

| Se1 | 370.5(8) | Se1 | 356(6) | ||||||||

| Pd2: | Se2 | 249.4(1) | 2× | Pd2: | Se2 | 248.6(2) | 2× | ||||

| Se1 | 250.7(1) | 2× | Se1 | 249.2(1) | 2× | ||||||

| Ag1a | 289.0(1) | 2× | Cu1a | 284.9(5) | 2× | ||||||

| Pd1b | 294.1(1) | Pd1b | 283(2) | ||||||||

| Pd1a | 320.2(1) | Pd1a | 308.0(2) | ||||||||

| Ag1b | 344.6(1) | Cu1b | 336.2(1) | ||||||||

Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Selected interatomic angles (deg) of Li2Pt3Se4, Ag2Pd3Se4, and Cu2Pd3Se4.

| Li2Pt3Se4 | ||

| Se2–Pt1–Se2 | 81.97(3) | |

| Se1–Pt1–Se1 | 87.53(2) | |

| Se2–Pt1–Se1 | 93.00(3) | |

| Se2–Pt1–Se1 | 97.55(2) | |

| Se2–Pt1–Se1 | 174.88(2) | |

| Se2–Pt1–Se1 | 174.90(2) | |

| Se1–Pt2–Se2 | 86.08(3) | 2× |

| Se1–Pt2–Se2 | 93.92(3) | 2× |

| Se1–Pt2–Se1 | 180.0 | |

| Se2–Pt2–Se2 | 180.0 | |

| Ag2Pd3Se4 | ||

| Se2–Pd1a–Se2 | 80.19(6) | |

| Se1–Pd1a–Se1 | 88.53(7) | |

| Se2–Pd1a–Se1 | 94.89(8) | |

| Se2–Pd1a–Se1 | 96.74(8) | |

| Se2–Pd1a–Se1 | 172.1(1) | |

| Se2–Pd1a–Se1 | 175.3(2) | |

| Se2–Pd2–Se1 | 82.93(2) | 2× |

| Se2–Pd2–Se1 | 97.07(2) | 2× |

| Se1–Pd2–Se1 | 180.0 | |

| Se2–Pd2–Se2 | 180.0 | |

| Cu2Pd3Se4 | ||

| Se2–Pd1a–Se2 | 82.95(6) | |

| Se1–Pd1a–Se1 | 85.90(5) | |

| Se1–Pd1a–Se2 | 94.01(7) | |

| Se2–Pd1a–Se1 | 97.36(7) | |

| Se1–Pd1a–Se2 | 175.4(2) | |

| Se1–Pd1a–Se2 | 175.8(2) | |

| Se2–Pd2–Se1 | 85.02(4) | 2× |

| Se2–Pd2–Se1 | 94.98(4) | 2× |

| Se1–Pd2–Se1 | 180.0 | |

| Se2–Pd2–Se2 | 180.0 | |

Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Further details of the crystal structure investigations may be obtained from Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe, 76344 Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany (fax: +49-7247-808-666; e-mail: crysdata@fiz-karlsruhe.de, http://www.fiz-karlsruhe.de/request_for_deposited_data.html) on quoting the deposition numbers CSD-431596 (Li2Pt3Se4), CSD-431597 (Ag2Pd3Se4), and CSD-431598 (Cu2Pd3Se4).

3.2 Crystal chemistry

As already mentioned, the lithium platinum selenide, Li2Pt3Se4 presented here, which was synthesized under high-pressure/high-temperature conditions of 8 GPa and 1200°C, crystallizes isostructurally to the corresponding sulfides Li2M3S4 (M=Pd, Pt) [7], and to the minerals chrisstanleyite (Ag2Pd3Se4) and jaguéite (Cu2Pd3Se4) [3]. Synthesis attempts for the missing compound Li2Pd3Se4 have failed so far, resulting in binary lithium selenide and various palladium selenides. Normal-pressure experiments in sealed silica ampoules were also performed without success. According to Vymazalová [4], the mineral chrisstanleyite is only stable at temperatures below 430°C. Our experiments to synthesize Li2M3X4 (M=Pd, Pt, X=S, Se) compounds exceeded this temperature significantly. Repetitions of the experiments at low temperatures are still pending. In Table 6 the lattice parameters of the known isostructural compounds are summarized.

Comparison of lattice parameters (pm) of the isostructural compounds Li2Pt3S4, Li2Pd3S4, and the minerals chrisstanleyite and jaguéite.

| Compound | a | b | c | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li2Pt3Se4 (this work) | 525.9(2) | 1040.6(2) | 636.5(2) | 111.91(3)° |

| Li2Pt3S4 [7] | 498.2(1) | 1005.5(2) | 613.0(2) | 110.76(3)° |

| Li2Pd3S4 [7] | 492.9(1) | 1005.9(2) | 614.9(2) | 110.91(3)° |

| Ag2Pd3Se4 (this work) | 563.46(3) | 1039.89(6) | 637.72(4) | 115.103(2)° |

| Chrisstanleyite [3] | 567.6(2) | 1034.2(4) | 634.1(2) | 114.996(4)° |

| Cu2Pd3Se4 (this work) | 563.8(2) | 986.6(2) | 624.3(2) | 115.40(3)° |

| Jaguéite [3] | 567.2(5) | 990.9(9) | 626.4(6) | 115.40(2)° |

Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

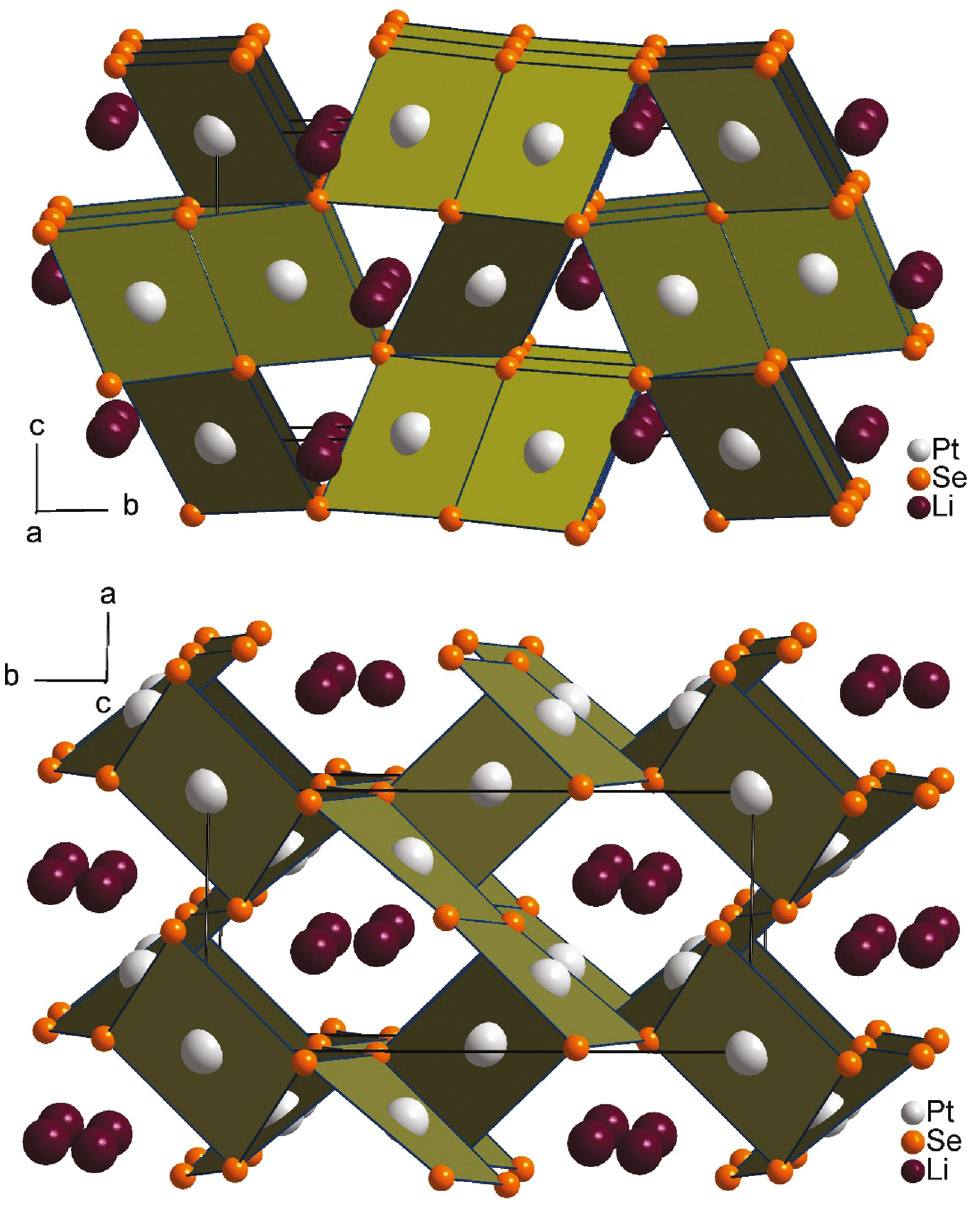

The crystal structure of Li2Pt3Se4 is built up from two distinct Pt sites (Pt1 on a general position; Pt2 on the special position at 0, 0, 0), two general selenium sites, and one general lithium site (see Table 2). Both Pt atoms are in a nearly square planar Se coordination with Pt–Se distances ranging from 244.8 to 247.5 pm. There are distinct differences between the two Pt sites, however. The atoms Pt2 occur in single PtSe4 units, whereas the atoms Pt1 form pairs of square planar PtSe4 units paired via a common Se2–Se2 edge and resulting in Pt1–Pt1 distances of 406.1(1) pm (see Fig. 2). These two units (single and paired PtSe4 units) build up a three-dimensional open network structure by linking the units through common corners. As a result of the arrangement of the PtSe4 units, channels are created, in which the lithium atoms are located. Figure 2 shows the crystal structure of Li2Pt3Se4 viewed along the crystallographic a and c axes, respectively. For a more detailed description of the crystal structure, the reader is referred to the references [3], [7]. A comparison of Li2Pt3Se4 and the synthetic mineral phases chrisstanleyite (Ag2Pd3Se4) and jaguéite (Cu2Pd3Se4) is given below.

Crystal structures of Li2Pt3Se4 as viewed along the crystallographic a (top) and c axes (down). Lithium, platinum and selenium are drawn as dark purple, light gray and orange circles, respectively. Relevant PtSe4 polyhedra are emphasized.

As already mentioned in the introduction, Paar [1], [2] described chrisstanleyite and jaguéite as commonly occurring, partially intergrown minerals, with a mixed (Ag, Cu) occupancy. Twenty percent of the silver atoms in chrisstanleyite are substituted by copper and 5% of the copper atoms in jaguéite are replaced by silver resulting in the corresponding compounds Ag1.6Cu0.4Pd3Se4 (chrisstanleyite) and Cu1.9Ag0.1Pd3Se4 (jaguéite). In the case of chrisstanleyite, Topa refined the mixed occupancy with equal isotropic displacement factors, but with free positional parameters [3] creating additional sites. For natural jaguéite no mixed occupancies were refined by Topa. The appearance of additional sites in this structure type is rather a stabilizing effect of an optimized network of metal-metal bonds than an effect of differences in the ionic radii of silver (Ag+ C.N. 6: 1.29 Å [32]) and copper (Cu+ C.N. 6: 0.91 Å [32]). This can be concluded from the refinements of the pure synthetic minerals presented here which show a comparable splitting of the copper and silver sites, without an occupation of the split sites with different atom types. Furthermore, for the Pd1 sites of the synthetic minerals a refinement of hitherto not described split positions at distances of 0.53 Å (Ag2Pd3Se4) and 0.64 Å (Cu2Pd3Se4) resulted in significantly better R values. Overall, the effect of layer splitting is more pronounced in Ag2Pd3Se4 (Ag1a/Ag1b: 0.90(1)/0.10(1); Pd1a/Pd1b: 0.92(1)/0.08(1)) than in Cu2Pd3Se4 (Cu1a/Cu1b: 0.94(2)/0.06(2); Pd1a/Pd1b: 0.95(1)/0.05(1)). Most likely, copper and silver occur strictly in the oxidation state +1 in these compounds. The occurrence of Cu2+ (or Ag2+) ions in a mixed occupation of the Pd1a/Pd1b sites as reason for the structural disorder is rather unlikely, but cannot be completely excluded. As already mentioned above, the R values worsen when the disorder is taken into accont. Moreover, the d8 Pd2+ ions gain a significantly better stabilization in the square planar ligand field than d9-configured Cu2+ (or Ag2+) ions would get. Magnetic measurements to confirm the exclusive +1 oxidation state of copper and silver have not been attempted as yet. Unfortunately, up to now we were not able to optimize the synthesis of Cu2Pd3Se4 in such a way as to obtain pure products without side phases, which is a premise for meaningful magnetic measurements.

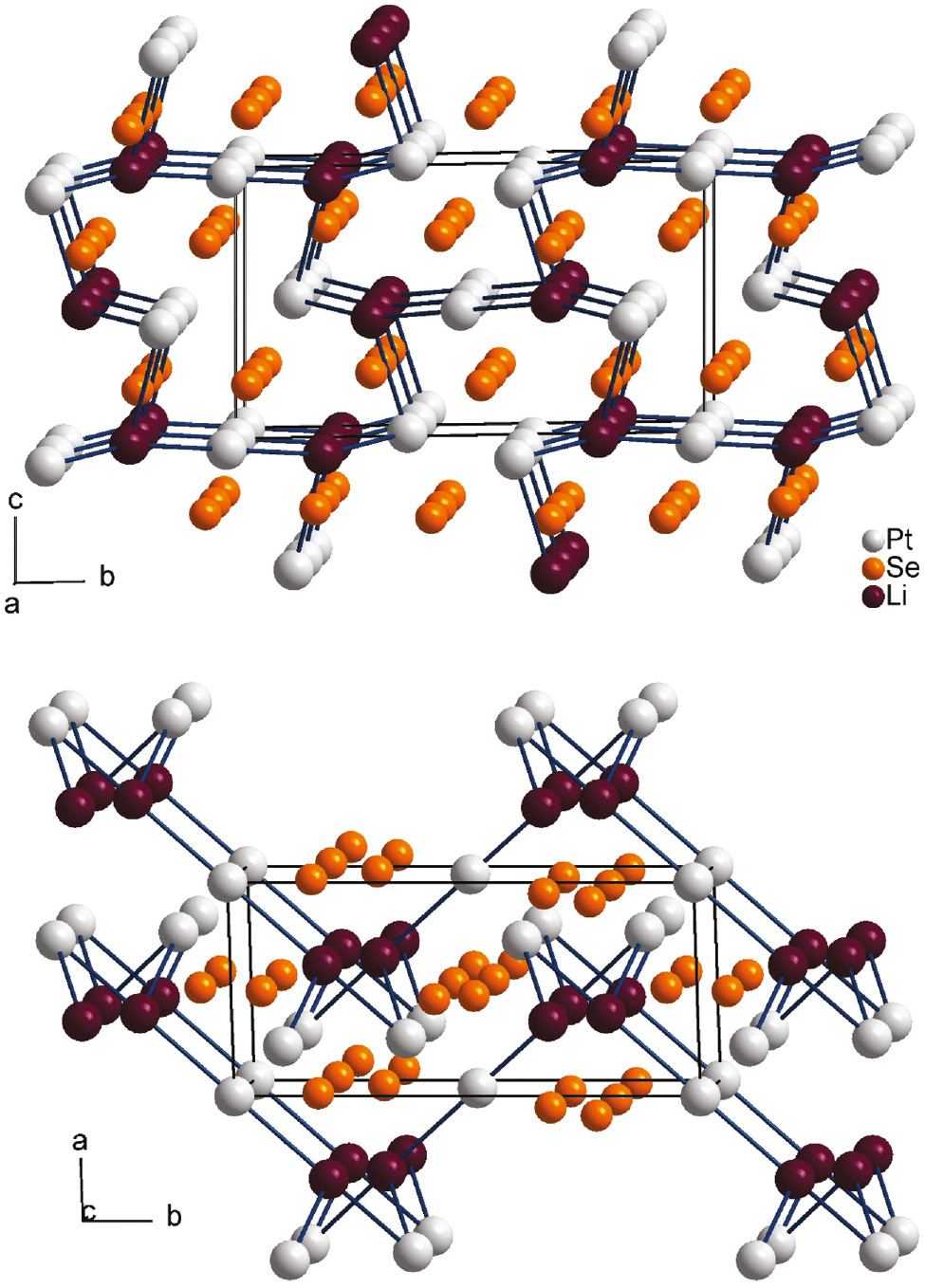

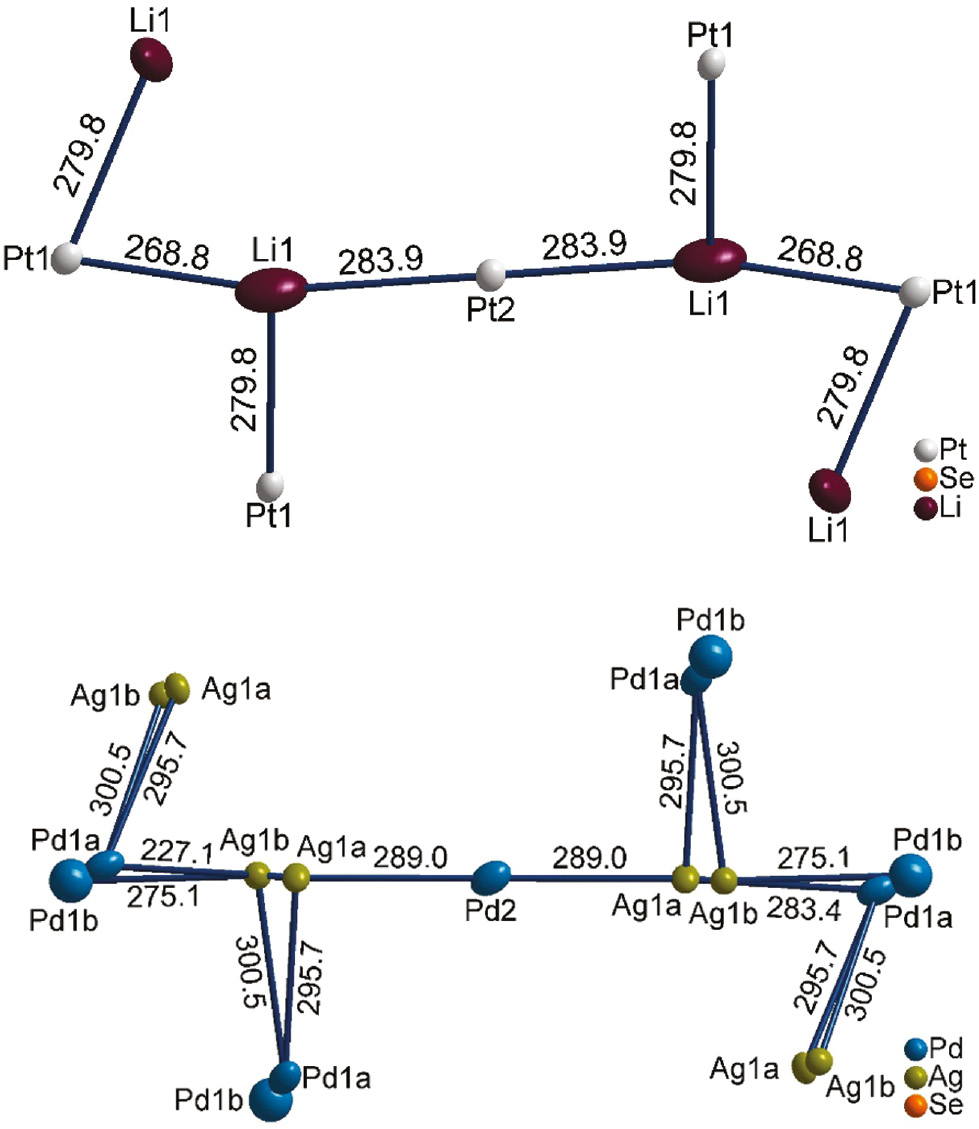

The replacement of Cu+/Ag+ by lithium (Li+ C.N.6: 0.90 Å [32]) in Li2Pt3Se4 and the isostructural compounds Li2Pt3S4 and Li2Pd3S4 [7] leads to the absence of split positions. Figure 3 shows the stabilizing metal–metal bond system of this structure type mentioned above, consisting of a nearly collinear sequence of four metal–metal bonds with distances of 268.8–283.9 pm (Li2Pt3Se4). The Pt1–Li1–Pt2–Li1–Pt1 sequences are interconnected via Pt1–Li1 bonds to zig-zag layers parallel to the bc plane. A comparable situation can be found for the isostructural compounds Li2Pd3S4 and Li2Pt3S4 with Li–Pd and Li–Pt contacts varying from 260.5–283.1 pm and 259.7–285.0 pm, respectively [7]. In Fig. 4, a cutout of the collinear metal–metal sequence demonstrates the different bonding situations in Li2Pt3Se4 and Ag2Pd3Se4. All contacts shorter than 301 pm are drawn as bonds. The metal–metal distances in Li2Pt3Se4 are less different and the contacts interconnecting the collinear sequences are much shorter than in Ag2Pd3Se4. With implementation of the additional split sites (split atoms are labeled with appendix a and b in Fig. 4) in Ag2Pd3Se4, two shorter Ag1b–Pd1a and Ag1b–Pd1b contacts of 227 pm and 275 pm become prominent, whereas the Ag1b–Pd2 contact is elongated up to 344 pm. Therefore, the Pd2 atoms remain isolated and the collinear metal-metal sequence changes into an alternating Ag1–Pd1 zig-zag sequence in the direction along the c axis. For Cu2Pd3Se4 (not shown) the situation is comparable.

Crystal structure of Li2Pt3Se4 as viewed along the a (top) and c axes (down) with Li–Pt metal–metal bonds drawn in a collinear sequence Pd2–Li–Pd1–Li–Pd2. Lithium, platinum and selenium are drawn as dark purple, light gray and orange circles, respectively.

Collinear sequence of Pt1-Li1-Pt2-Li1-Pt1 in Li2Pt3Se4 (top) and corresponding sequence in Ag2Pd3Se4 (down) with Pd1 and Ag1 split positions. Atom distances shorter than 301 pm are drawn as bonds. All distances are given in pm.

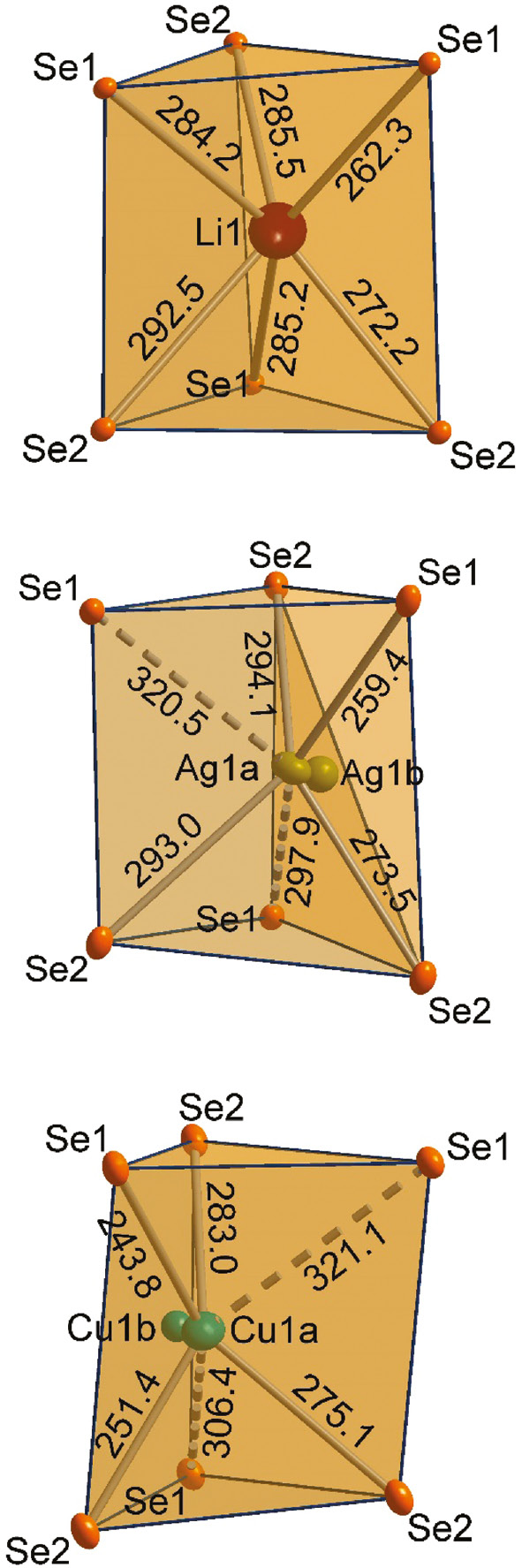

Differences between the lithium-containing compounds and the mineral phases regarding the coordination of lithium, silver and copper are evident. Topa [3] described the coordination polyhedra of copper and silver as strongly elongated tetrahedra with Cu–Se distances of 244.4–285.7 pm for jaguéite, and Ag–Se distances of 259.0–294.8 pm for chrisstanleyite. The lithium atoms in Li2M3X4 (M=Pd, Pt, X=S, Se) are coordinated by six chalcogenide atoms in a distorted trigonal prismatic coordination geometry. The distances range from 249.8–288.5 pm for Li2Pd3S4, 247.9–288.6 pm for Li2Pt3S4, and 262.3–292.5 pm for Li2Pt3Se4 (see Table 4). In Fig. 5 the lithium, silver and copper coordination polyhedra are shown with relevant distances. Li2Pt3Se4 exhibits two short Li–Se contacts (262.3 pm, 272.2 pm) and four longer (284.2–292.5 pm) ones (see Table 4). Nevertheless, the distances are more uniform than in Ag2Pd3Se4 and Cu2Pd3Se4. Between the shortest and the longest contacts in Li2Pt3Se4, a difference of 30 pm occurs. Considering the same distance criterion for the compounds Ag2Pd3Se4 and Cu2Pd3Se4, only two Se atoms appear inside the coordination sphere. For a tetrahedral coordination of Ag1a and Cu1a, the minimum spread of the four Ag–Se and Cu–Se distances are 35 pm and 39 pm, respectively. Significantly more pronounced is the difference between the shortest and longest contacts, assuming a trigonal prismatic coordination of Ag (61 pm) and Cu (77 pm) as shown for Li2M3X4 (M=Pd, Pt, X=S, Se). As a result of the split positions, the effect increases even more, and the coordination of Ag and Cu moves towards a square planar coordination sphere.

The distorted trigonal prismatic selenium coordination polyhedra of the Li, Ag, and Cu atoms in Li2Pt3Se4 (top), Ag2Pd3Se4 (middle), and Cu2Pd3Se4 (down) are shown, respectively. All distances are given in pm.

4 Conclusion

Li2Pt3Se4, showing a structure analogous to Li2M3S4 (M=Pd, Pt), was synthesized under high-pressure/high-temperature conditions of 8 GPa and 1200°C. Under the same conditions the isostructural minerals jaguéite (Cu2Pd3Se4) and chrisstanleyite (Ag2Pd3Se4) were reproduced in their ideal stoichiometric ratio and investigated by single-crystal X-ray analysis. In contrast to the structure refinements of Topa [3], a disorder phenomenon was observed for the synthetic mineral phases. Structural differences, especially with regard to the coordination environments, were identified and analyzed in this work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. H. Huppertz for continuous support and access to all the facilities of the Institute of General, Inorganic and Theoretical Chemistry, University of Innsbruck. For discussion and support regarding the single-crystal refinements we thank Dr. Klaus Wurst, University of Innsbruck. Dr. G. Heymann is supported by the program Nachwuchsförderung of the University of Innsbruck.

References

[1] W. H. Paar, D. Topa, E. Makovicky, R. J. Sureda, M. K. de Brodtkorb, E. H. Nickel, H. Putz, Can. Mineral.2004, 42, 1745.10.2113/gscanmin.42.6.1745Suche in Google Scholar

[2] W. H. Paar, A. C. Roberts, A. J. Criddle, D. Topa, Mineral. Mag.1998, 62, 257.10.1180/002646198547611Suche in Google Scholar

[3] D. Topa, E. Makovicky, T. Balić-Žunić, Can. Mineral.2006, 44, 497.10.2113/gscanmin.44.2.497Suche in Google Scholar

[4] A. Vymazalová, D. A. Chareev, A. V. Kristavchuk, F. Laufek, M. Drábek, Can. Mineral.2014, 52, 77.10.3749/canmin.52.1.77Suche in Google Scholar

[5] F. Laufek, A. Vymazalová, D. A. Chareev, A. V. Kristavchuk, Q. Lin, J. Drahokoupil, T. M. Vasilchikova, J. Solid State Chem.2011, 184, 2794.10.1016/j.jssc.2011.08.019Suche in Google Scholar

[6] F. Laufek, A. Vymazalová, D. A. Chareev, A. V. Kristavchuk, J. Drahokoupil, M. V. Voronin, Powder Diffr.2013, 28, 13.10.1017/S0885715612000929Suche in Google Scholar

[7] G. Heymann, O. Niehaus, H. Krüger, P. Selter, G. Brunklaus, R. Pöttgen, J. Solid State Chem.2016, 242, 87.10.1016/j.jssc.2015.12.031Suche in Google Scholar

[8] R. Ang, Y. Miyata, E. Ieki, K. Nakayama, T. Sato, Y. Liu, W. J. Lu, Y. P. Sun, T. Takahashi, Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter2013, 88, 115145.10.1103/PhysRevB.88.115145Suche in Google Scholar

[9] S. Nagata, T. Atake, J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.1999, 57, 807.10.1023/A:1010142225299Suche in Google Scholar

[10] A. P. Ramirez, R. J. Cava, J. Krajewski, Nature1997, 386, 156.10.1038/386156a0Suche in Google Scholar

[11] O. Lang, C. Felser, R. Seshadri, F. Renz, J. M. Kiat, J. Ensling, P. Gütlich, W. Tremel, Adv. Mater.2000, 12, 65.10.1002/(SICI)1521-4095(200001)12:1<65::AID-ADMA65>3.0.CO;2-USuche in Google Scholar

[12] R. Pocha, C. Löhnert, D. Johrendt, J. Solid State Chem.2007, 180, 191.10.1016/j.jssc.2006.09.028Suche in Google Scholar

[13] W. Tremel, H. Kleinke, V. Derstroff, C. Reisner, J. Alloys Compd.1995, 219, 73.10.1016/0925-8388(94)05064-3Suche in Google Scholar

[14] T. Hughbanks, J. Alloys Compd.1995, 229, 40.10.1016/0925-8388(95)01688-0Suche in Google Scholar

[15] J. Cabana, L. Monconduit, D. Larcher, M. R. Palacín, Adv. Mater.2010, 22, E170.10.1002/adma.201000717Suche in Google Scholar

[16] D. Chen, G. Ji, B. Ding, Y. Ma, B. Qu, W. Chen, J. Y. Lee, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.2014, 53, 17901.10.1021/ie503759vSuche in Google Scholar

[17] X. Xu, W. Liu, Y. Kim, J. Cho, Nano Today2014, 9, 604.10.1016/j.nantod.2014.09.005Suche in Google Scholar

[18] H. Huppertz, Z. Kristallogr.2004, 219, 330.10.1524/zkri.219.6.330.34633Suche in Google Scholar

[19] D. Walker, M. A. Carpenter, C. M. Hitch, Am. Mineral.1990, 75, 1020.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] D. Walker, Am. Mineral.1991, 76, 1092.10.1007/978-1-4615-3968-1_10Suche in Google Scholar

[21] D. C. Rubie, Phase Transit.1999, 68, 431.10.1080/01411599908224526Suche in Google Scholar

[22] P. Thompson, D. E. Cox, J. B. Hastings, J. Appl. Crystallogr.1987, 20, 79.10.1107/S0021889887087090Suche in Google Scholar

[23] R. A. Young, P. Desai, Arch. Nauki. Mater.1989, 10, 71.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Z. Otwinowski, W. Minor in Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 276, (Eds.: C. W. Charles, J. Carter and M. Sweet), Academic Press, USA, 1997, p. 307.10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-XSuche in Google Scholar

[25] Apex2 (version 2014.11-0), Saint (version 8.34A), Sadabs (version 2014/5), and Cell_Now (version 2008/4), Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe (Germany).Suche in Google Scholar

[26] A. Gibaud, M. Topić, G. Corbel, C. I. Lang, J. Alloys Compd.2009, 484, 168.10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.05.050Suche in Google Scholar

[27] F. Grønvold, H. Haraldsen, A. Kjekshus, Acta Chem. Scand.1960, 14, 1879.10.3891/acta.chem.scand.14-1879Suche in Google Scholar

[28] P. Matković, K. Schubert, J. Less-Common Met.1977, 55, 185.10.1016/0022-5088(77)90191-6Suche in Google Scholar

[29] G. M. Sheldrick, Shelxs-2013, Program for the Solution of Crystal Structures, University of Göttingen, Göttingen (Germany) 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] G. M. Sheldrick, Shelxl-2013, Program for the Refinement of Crystal Structures – Multi-CPU Version, University of Göttingen, Göttingen (Germany) 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] G. Sheldrick, Acta Crystallogr.2015, C71, 3–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] N. Wiberg, Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie, de Gruyter, Berlin, 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

©2016 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Li2Pt3Se4: a new lithium platinum selenide with jaguéite-type crystal structure by multianvil high-pressure/high-temperature synthesis

- RE4B4O11F2 (RE = Sm, Tb, Ho, Er): four new rare earth fluoride borates isotypic to Gd4B4O11F2

- Regioselective C-3 arylation of coumarins with arylhydrazines via radical oxidation by potassium permanganate

- Two new POM-based compounds containing a linear tri-nuclear copper(II) cluster and an infinite copper(II) chain, respectively

- Environmentally benign synthesis of methyl 6-amino-5-cyano-4-aryl-2,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole-3-carboxylates using CeO2 nanoparticles as a reusable and robust catalyst

- Synthesis and structural characterization of Ca12Ge17B8O58

- Synthesis of some new hydrazide-hydrazones related to isatin and its Mannich and Schiff bases

- Purpureone, an antileishmanial ergochrome from the endophytic fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum

- Syntheses and crystal structures of two new silver–organic frameworks based on N-pyrazinesulfonyl-glycine: weak Ag···O/N interaction affecting the coordination geometry

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Li2Pt3Se4: a new lithium platinum selenide with jaguéite-type crystal structure by multianvil high-pressure/high-temperature synthesis

- RE4B4O11F2 (RE = Sm, Tb, Ho, Er): four new rare earth fluoride borates isotypic to Gd4B4O11F2

- Regioselective C-3 arylation of coumarins with arylhydrazines via radical oxidation by potassium permanganate

- Two new POM-based compounds containing a linear tri-nuclear copper(II) cluster and an infinite copper(II) chain, respectively

- Environmentally benign synthesis of methyl 6-amino-5-cyano-4-aryl-2,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole-3-carboxylates using CeO2 nanoparticles as a reusable and robust catalyst

- Synthesis and structural characterization of Ca12Ge17B8O58

- Synthesis of some new hydrazide-hydrazones related to isatin and its Mannich and Schiff bases

- Purpureone, an antileishmanial ergochrome from the endophytic fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum

- Syntheses and crystal structures of two new silver–organic frameworks based on N-pyrazinesulfonyl-glycine: weak Ag···O/N interaction affecting the coordination geometry

![Fig. 1: XRD pattern (MoKα1 radiation) of Li2Pt3Se4, simultaneously refined with Pt [26], PtSe2 [27], and Pt5Se4 [28] (Rexp=1.65, Rwp=2.57, Rp=1.85, and GOF=1.56).](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2016-0165/asset/graphic/j_znb-2016-0165_fig_001.jpg)