Syntheses and crystal structures of two new silver–organic frameworks based on N-pyrazinesulfonyl-glycine: weak Ag···O/N interaction affecting the coordination geometry

Abstract

Two new metal–organic frameworks, namely, [Ag2(L)]n (1) and {[Ag2.5(L)(bpy)2]·(NO3)0.5·(H2O)4.5}n (2), where H2L=N-pyrazinesulfonyl-glycine and bpy=4,4′-bipyridine, have been synthesized and characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction, IR spectroscopy, and elemental analysis. X-ray diffraction crystallographic analyses indicate that 1 displays a silver carboxylate-sulfonamide layer structure containing an uncommon heptanuclear [Ag7] cluster wherein four silver(I) atoms form an Ag4 plane with in a three-connected (6, 3) net. The molecular structure of 2 has three crystallographically independent two-coordinate Ag centers with an intersecting Ag-bpy chain structure in a six-connected (3, 6) or a four-connected (4, 4) topology. The L2− ligand serves as a μ7-(η2-O,N), (η2-O′,N′), O,O″,O″′,N,N″ ligand in 1 and as a μ3-(η2-O,N), N,O′ ligand in 2. In the crystal, a 3D supramolecular architecture is formed by coordinative bonding in 1, but through O–H···O bonding as well as π···π stacking in 2. The two compounds show a combination of coordinative bonds, ligand-supported Ag···Ag interactions and weak Ag···O/N coordinative interactions in the solid state.

1 Introduction

Silver–organic frameworks as an important class of crystalline materials have been attracting considerable attention due to their extensive applications in luminescence, gas adsorption, magnetic switching devices, catalysis, and so on [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. Ag metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) not only show more structural diversity, but also exhibit synergistic effects between organic and inorganic components compared with other MOFs. The assemblies of these MOFs are heavily influenced by many factors such as the pH value, the molar ratio of the molecular components, solvent, steric requirement of the counterions, and reaction temperature, together with the coordination nature of metal ions and organic ligands [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. MOFs derived from the “softer” Ag+ ions demonstrate a unique behavior in comparison to other transition metals [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. As is well known, the Ag(I) ion commonly has a coordination number varying from 2 to 4 and is accompanied by a variety of coordination geometries such as linear, trigonal, and tetrahedral, which give rise to novel coordination networks [16], [17], [18], [19]. An interesting aspect of the silver(I) complexes is the common observation of short Ag···Ag contacts (termed argentophilicity, Ag(I)···Ag(I)<3.4 Å), which have been proved to be one of the most important factors contributing to the formation of such complexes and their special properties [20]. In recent years, the studies of Ag-MOFs based on functional organic polycarboxylate ligands have made great progress [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. However, the rational design and synthesis of Ag-MOFs with unique structure and function is a very intricate process, and still remains a big challenge.

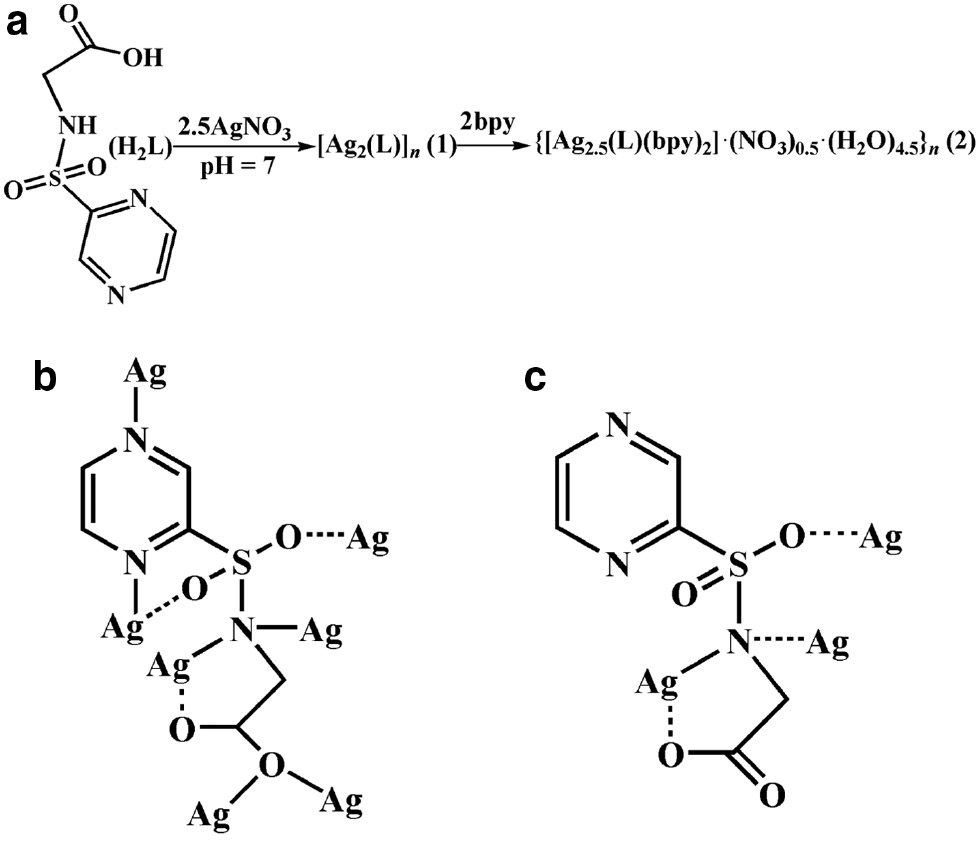

In our continuous efforts to study the coordination chemistry of N-pyrazinesulfonyl-glycine (H2L) ligand with its versatile functional groups, we have shown that H2L can also be self-assembled with the coordinatively flexible silver(I) cation. We report here two novel silver(I) polymers, [Ag2(L)]n (1) and {[Ag2.5(L)(4,4′-bipy)2]·(NO3)0.5·(H2O)4.5}n (2), with regard to syntheses, crystal structures, and IR spectra. Compound 1 is a 3D supramolecular framework having a silver(I)-carboxylate-sulfonamide layer constructed from heptanuclear [Ag7] clusters and L2− ligands, whereas 2 is a 2D supramolecular network formed by silver(I)-bpy intersecting chains and L2− ligands through coordinative bonds, ligand-supported Ag···Ag interactions, and weak Ag···O/N coordinative interactions (Scheme 1).

(a) The synthesis for 1 and 2; (b) view of the coordination mode of the L2− ligand in 1; (c) view of the coordination mode of the L2− ligand in 2.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Description of the crystal and molecular structure of [Ag2(L)]n (1)

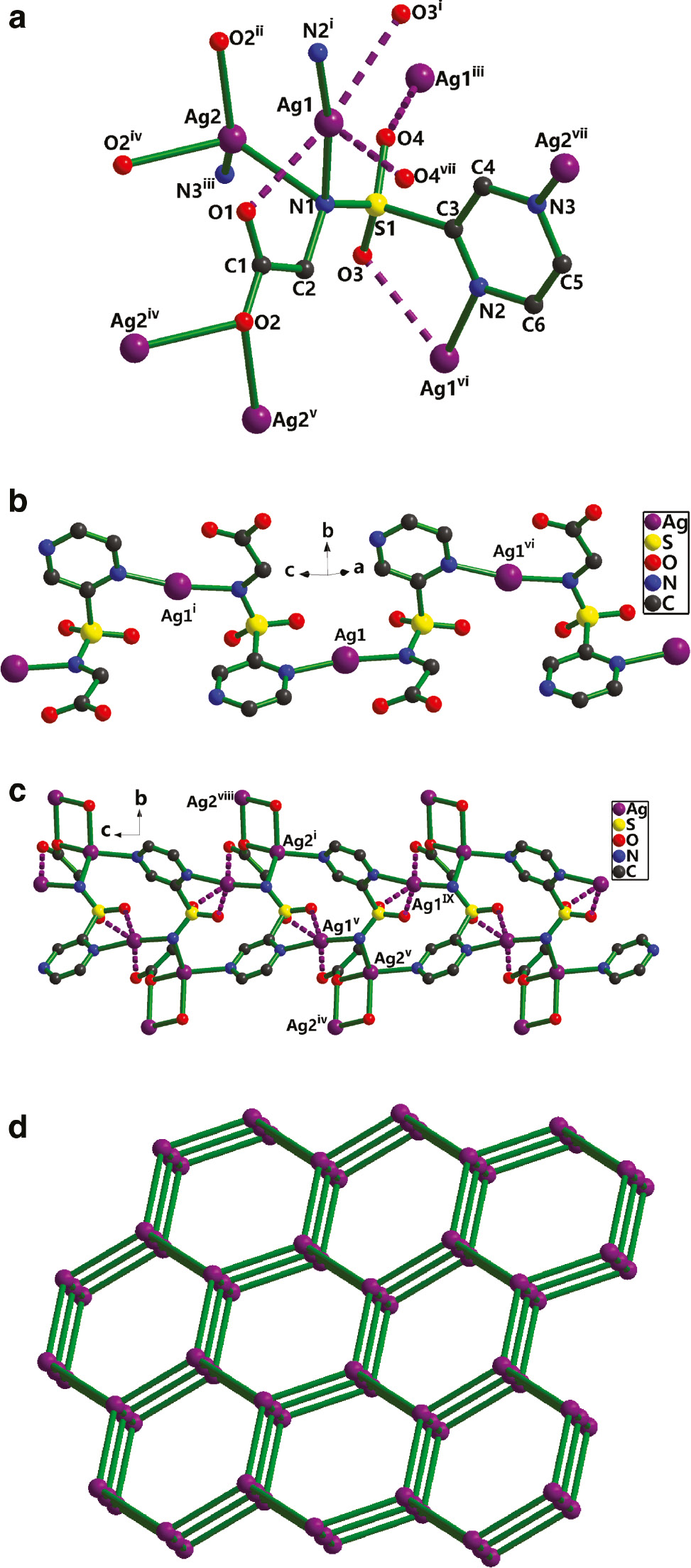

The single-crystal X-ray diffraction structural analysis has revealed that 1 is a 3D coordination polymer, whose asymmetric unit comprises two crystallographically nonequivalent Ag(I) cations and a doubly deprotonated chelating L2− ligand. As is shown in Fig. 1a, two unique Ag(I) ions display two types of coordination modes (neglecting the weak Ag···O and Ag···Ag interactions). Ag1 is coordinated by two nitrogen atoms (Ag1–N1=2.222(5) Å, Ag1–N2i=2.249(5) Å, symmetry code: i: x–1/2, –y+1/2, z+1/2) from two different L2− anions with an N1–Ag1–N2i bond angle of 168.67(19)°, whereas Ag2 is ligated by two oxygen donors (Ag2–O2ii=2.310(5) Å, Ag2–O2iv=2.363(4) Å) and two nitrogen atoms (Ag2–N1=2.399(5) Å, Ag2–N3iii=2.327(6) Å) (symmetry codes: ii: x–1, y, z; iii: x–1/2, –y+1/2, z–1/2; iv: –x+2, –y, –z) from four discrete L2− ligands (Table 1). Ag2 adopts distorted tetrahedral coordination geometry with the bond angles spanning the range from 87.08(16)° to 137.9(2)°, with τ4=0.4 for Ag2. The distortion of the tetrahedron can be indicated by the calculated value of the τ4 parameter introduced by Houser [26] to describe the geometry of a four-coordinated transition metal system (for perfect tetrahedral geometry, τ4=1). The Ag–O/N bond lengths are comparable to those observed in related silver(I) compounds [22], [23], [24], [25]. However, the distances Ag1–O1 (2.570(5) Å), Ag1–O3i (2.660(7) Å), and Ag1–O4vii (2.741(5) Å) (symmetry code: vii: x+1/2, –y+1/2, z+1/2) are beyond the range of 2.32–2.52 Å for silver(I) carboxylates but still shorter than the sum of van der Waals radii (3.24 Å) of the Ag and oxygen atoms, suggesting the existence of significant Ag···O interactions and explaining the deviation of the Ag(I) center from perfect linear-shaped geometry. Within this unit, the Ag1···Ag2 distance is 2.964(8) Å, implying the existence of ligand-supported argentophilic interactions. Taking weak Ag–O interactions into account, the coordination mode of L2− can be described as μ7-(η2-O,N), (η2-O′,N′), O,O″,O″′,N,N″ in 1, which has never been reported in Ag-containing compounds. A better insight into the nature of this intricate heptanuclear silver cluster can be achieved by removing the organic L2− ligand. Four Ag ions (Ag1iii/Ag1vi/Ag2/Ag2v) are co-planar and form an Ag4 plane with the Ag1iii/Ag2=Ag1vi/Ag2v and Ag1iii/Ag1vi=Ag2/Ag2v (for symmetry codes see Fig. 1a) separations of 5.19(7) and 5.92(1) Å, respectively. The adjacent Ag1 ions are connected by one L2− to give an [Ag(L)] covalent chain along the c axis (Fig. 1b), which is further extended by the bonds Ag2–N1 and Ag2–N3 leading to a layer. As shown in Fig. 1c, an overall 3D supramolecular framework results from the linkage of neighboring layers through Ag2–O2 bonds. From the topological point of view, each Ag7 cluster links three L2− units as a three-connected node, and each L2− ligand bridges two Ag7 clusters acting as a linker. The 3D MOF topology of 1 can be classified as a three-connected (6, 3) net (Fig. 1d). There are no remarkable hydrogen bonds or π stacking interactions in 1, but a weak non-classical C–H···O contact (Table 2).

(a) The coordination environment for Ag+ in 1 (symmetry codes: i: x–1/2, –y+1/2, z+1/2; ii: x–1, y, z; iii: x–1/2, –y+1/2, z–1/2; iv: –x+2, –y, –z; v: x+1, y, z; vi: x+1/2, –y+1/2, z–1/2; vii: x+1/2, –y+1/2, z+1/2). (b) The 1D coordination framework of Ag1 in 1. (c) View of the 3D coordination grid framework along the a axis (symmetry codes: i: x–1/2, –y+1/2, z+1/2; iv: –x+2, –y, –z; v: x+1, y, z; viii: –x+5/2, y+1/2, –z+1/2; ix: x+3/2, –y+1/2, z–1/2). (d) The simplified topology (6, 3) considering the Ag7 cluster as a node and the linkers representing L2−.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) for 1 and 2 with estimated standard deviations in parentheses.

| Compound 1a | |||

| Ag1–N1 | 2.222(5) | Ag1–N2i | 2.249(5) |

| Ag1–O1 | 2.570(5) | Ag1–Ag2 | 2.9636(8) |

| Ag2–O2ii | 2.310(5) | Ag2–N3iii | 2.327(6) |

| Ag2–O2iv | 2.363(4) | Ag2–N1 | 2.399(5) |

| N1–Ag1–N2i | 168.67(19) | N1–Ag1–O1 | 70.13(17) |

| Ag1–N1–Ag2 | 79.68(17) | N1–Ag1–Ag2 | 52.79(13) |

| N2i–Ag1–O1 | 98.54(18) | O1–Ag1–Ag2 | 72.99(15) |

| N2i–Ag1–Ag2 | 125.20(14) | O2ii–Ag2–N3iii | 137.9(2) |

| O2ii–Ag2–O2iv | 87.08(16) | O2ii–Ag2–N1 | 113.79(18) |

| N3iii–Ag2–O2iv | 96.99(18) | O2iv–Ag2–N1 | 122.70(17) |

| N3iii–Ag2–N1 | 99.10(19) | N3iii–Ag2–Ag1 | 141.20(14) |

| O2ii–Ag2–Ag1 | 66.38(13) | N1–Ag2–Ag1 | 47.53(13) |

| O2iv–Ag2–Ag1 | 116.92(12) | Ag2v–O2–Ag2iv | 92.92(16) |

| Compound 2b | |||

| Ag1–N4 | 2.224(4) | Ag1–N1 | 2.281(4) |

| Ag1–O1 | 2.566(5) | Ag1–N1i | 2.626(4) |

| Ag1–Ag1i | 2.8777(9) | Ag2–N6 | 2.164(4) |

| Ag2–N5 | 2.170(4) | Ag3–N7 | 2.147(4) |

| S1–O3 | 1.437(4) | ||

| N4–Ag1–N1 | 154.35(16) | O1–Ag1–N1i | 143.72(16) |

| N4–Ag1–O1 | 98.14(16) | N4–Ag1–Ag1i | 141.01(12) |

| N1–Ag1–O1 | 70.99(14) | N1–Ag1–Ag1i | 59.88(10) |

| N4–Ag1–N1i | 93.94(15) | O1–Ag1–Ag1i | 118.52(11) |

| N1–Ag1–N1i | 108.59(12) | N1i–Ag1–Ag1i | 48.71(9) |

| N6–Ag2–N5 | 177.53(18) | N7–Ag3–N7ii | 180 |

aSymmetry codes: i: x–1/2, –y+1/2, z+1/2; ii: x–1, y, z; iii: x–1/2, –y+1/2, z–1/2; iv: –x+2, –y, –z; v: x+1, y, z.

bSymmetry code: i: –x+1, –y, –z+1; ii: –x+2, –y+4, –z+2.

Hydrogen bond geometry (Å, deg) in crystalline 1 and 2 with estimated standard deviations in parentheses.

| D–H···A | d(D–H) | d(H···A) | d(D···A) | ∠(DHA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound 1a | ||||

| C5–H5···O1viii | 0.93 | 2.51 | 3.407(9) | 163 |

| Compound 2b | ||||

| O8–H8B···O7iii | 0.85 | 2.49 | 3.26(2) | 150 |

| O9–H9A···O10iv | 0.85(6) | 1.97(7) | 2.685(9) | 141(10) |

| O9–H9B···O5 | 0.85(7) | 2.04(10) | 2.744(11) | 139(8) |

| O10–H10A···O11v | 0.84(7) | 2.18(9) | 2.761(9) | 125(8) |

| O10–H10B···O1iv | 0.84(7) | 2.00(8) | 2.808(8) | 162(8) |

| O11–H11A···O2vi | 0.85(6) | 1.89(6) | 2.737(9) | 173(19) |

| O11–H11B···O5 | 0.85(7) | 2.13(7) | 2.832(10) | 140(7) |

| O11–H11B···O7 | 0.85(8) | 2.48(8) | 3.204(18) | 144(7) |

| O12–H12B···O2vi | 0.85(6) | 2.16(10) | 2.911(11) | 147(11) |

| C4–H4···O4 | 0.93 | 2.55 | 2.911(8) | 104 |

| C6–H6···O6 | 0.93 | 2.60 | 3.405(13) | 146 |

| C8–H8···O9 | 0.93 | 2.50 | 3.286(9) | 142 |

| C10–H10···O6iv | 0.93 | 2.51 | 3.407(15) | 162 |

| C12–H12···O3iv | 0.93 | 2.46 | 3.187(7) | 135 |

| C12–H12···N2iv | 0.93 | 2.62 | 3.424(8) | 146 |

| C16–H16···O12 | 0.93 | 2.52 | 3.341(9) | 148 |

| C25–H25···O9vii | 0.93 | 2.57 | 3.375(9) | 144 |

aSymmetry codes: viii: –x+5/2, y+1/2, –z+1/2.

bSymmetry codes: iii: x+1, y, z; iv: –x+1, –y+1, –z+1; v: x, y, z–1; vi: x, y+1, z; vii: –x+1, –y+2, –z+2.

2.2 Description of the crystal and molecular structure of {[Ag2.5(L)(4,4′-bipy)2]· (NO3)0.5·(H2O)4.5}n (2)

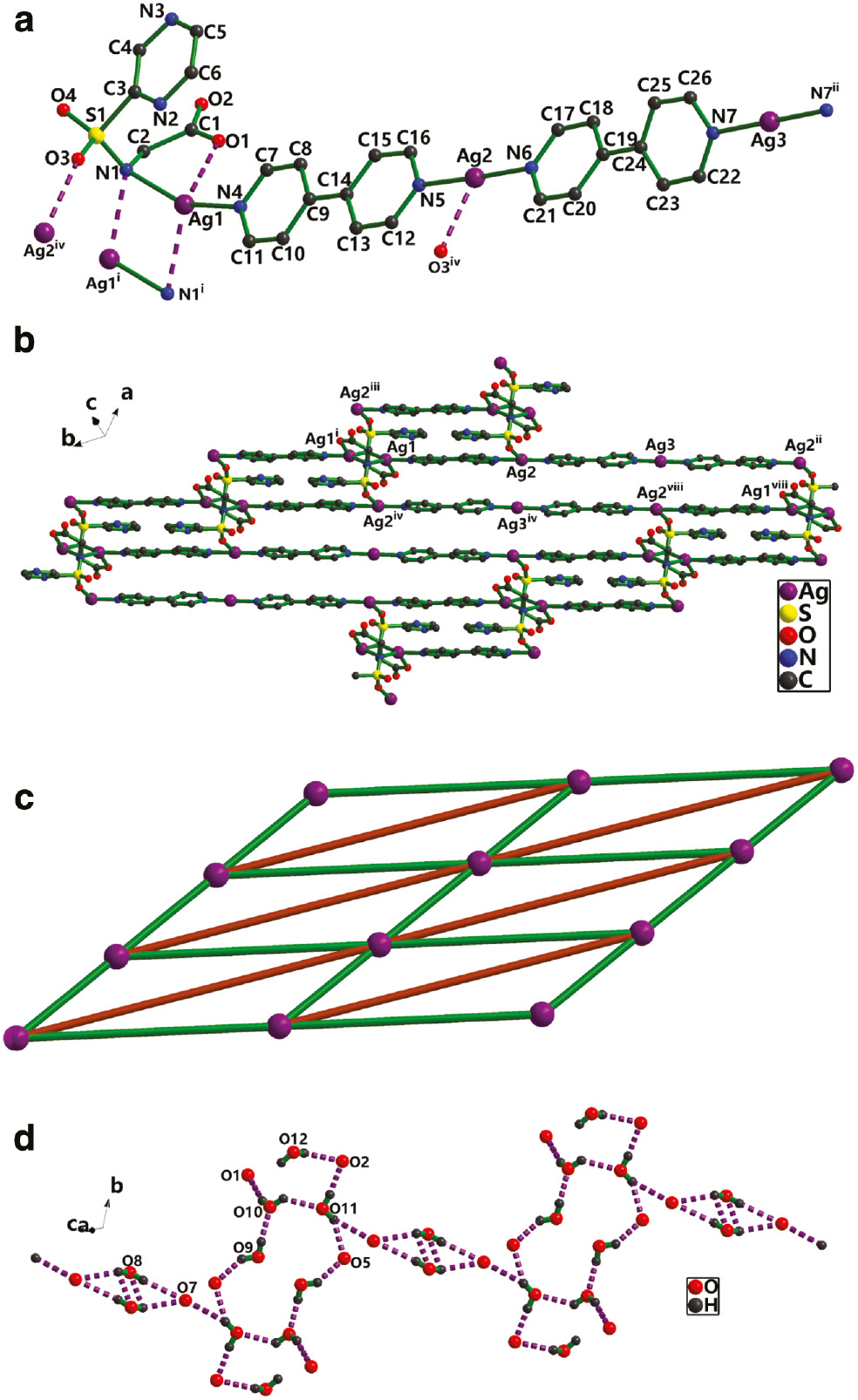

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis has revealed that 2 crystallizes in the triclinic space group P1̅ as a 2D supramolecular network generated from a combination of coordinative bonds, ligand-supported Ag···Ag interactions, and weak Ag···O/N coordinative interactions. The asymmetric unit of 2 consists of two and a half crystallographically unique Ag(I) ions, one L2− dianion, a half of an NO3− ion, two 4,4′-bipy ligands, as well as four and a half solvent water molecules. As shown in Fig. 2a, the Ag1 and Ag2 atoms (neglecting the weak Ag···O, Ag···N, and Ag···Ag interactions) adopt a distorted linear geometry with two nitrogen atoms from one L2− and one bpy for Ag1, and two different bpy for Ag2, whereas Ag3 is located at a center of symmetry, connecting two symmetry-related bpy with a bond N7–Ag3–N7ii angle of 180° (symmetry code: ii: –x+2, –y+4, –z+2). The preferred coordination of the silver ions to the pyridyl sites is manifested by the relatively short Ag–N bond distances. In 2, these are Ag1–N 2.224(4) and 2.281(4) Å, Ag2–N 2.164(4) and 2.170(4) Å, and Ag3–N 2.147(4) Å, with additional binding of Ag1 and Ag2 to the carboxylate, sulfonyl, and imine function of the bridging ligand L2− (Fig. 1a). The inversion-related Ag1 pair is coordinated from both sides in a μ2-η1:η1 bridging mode by carboxylate and imine groups at relatively long Ag–O and Ag–N distances of 2.566(5) and 2.626(4) Å, with an Ag···Ag separation of 2.8777(9) Å, implying the existence of ligand-supported argentophilic interactions. Ag2 is coordinated in a monodentate fashion to one of the sulfonyl O atoms at Ag2–O=2.66(8) Å, forming [Ag4L2] secondary building units (SBUs between adjacent [Ag-bpy] polymeric chains). Ag3 lies at an inversion center, coordinated by two symmetry-related bpy in a μ2-η1:η1 bridging mode. Taking weak Ag–O/N interactions into account, the coordination mode of L2− can be denoted as μ3-(η2-O,N),N,O′ in 2. There are open voids within the 2D array (Fig. 2b), as there is an alternating connection with bpy between the Ag1, Ag2, and Ag3 metal nodes of neighboring chains in the layer. These voids contain solvent molecules and NO3− anions. From the topological point of view, each [Ag4L2] SBU links four bpy and two Ag(bpy)2 as a six-connected node, and each bpy or Ag(bpy)2 bridges two [Ag4L2] acting as a linker. The 2D MOF structure of 2 can be simplified as a six-connected (3, 6) grid layer topology (Fig. 1c). On the other hand, each [(Ag4L2)(bpy)]2 unit serves as a four-connected node, and each [Ag(bpy)2]+ acts as a linker. The 2D MOF structure of 2 can be simplified as a four-connected (4, 4) grid layer topology.

(a) The coordination environment for Ag+ in 2 (symmetry codes: i: –x+1, –y, –z+1; ii: –x+2, –y+4, –z+2; iv: –x+1, –y+1, –z+1). (b) The Ag-pby chain in 2 (symmetry codes: i: –x+1, –y, –z+1; ii: –x+2, –y+4, –z+2; iv: –x+1, –y+1, –z+1; viii: x, y–1, z). (c) The simplified representation of the 2D (3, 6) grid network (green lines represent bpy ligand, brown lines represent Ag(bpy)2) chains. (d) View of O–H···O hydrogen bonded rings in 2.

The stacking between the 2D polymeric arrays in structure 2 is further stabilized by numerous hydrogen bonding interactions, involving the water molecules, the NO3− anions, and the carboxylate groups. Intermolecular O–H···O hydrogen bonds constitute

2.3 Infrared spectra of 1 and 2

Complexes 1 and 2 exhibit infrared bands in the range 4000–450 cm−1, which are different from those of the free ligand. The band ν(NH)=3278 cm−1 of the H2L molecule is absent in the spectra of 1 and 2 indicating the deprotonation of the imine N atom upon coordination to the metal ion. Bands assigned to νas(COO−) and νs(COO−), which are observed for the free ligand at 1730 and 1406 cm−1, respectively, are shifted to 1586 for 1, 1598 for 2 and 1398 for 1, 1404 cm−1 for 2, indicating that deprotonation of the carboxylate groups occurred upon coordination. The νas(–SO2–) (1330 cm−1 for H2L, 1223 cm−1 for 1, and 1218 cm−1 for 2) and νs(–SO2–) (1128 cm−1 for H2L, 1045 cm−1 for 1, and 1086 cm−1 for 2) bands show differences from that of H2L, suggesting that this group does also interact with the metal ion. Bands centered at 3406, 1384, and 853 cm−1 ascribed to H2O and νas(NO3−), νs(NO3−) for 2, are absent in the spectra of 1. All these spectroscopic features of H2L and 1, 2 are consistent with the crystal structure determinations.

3 Conclusions

In summary, two Ag-MOFs based on the L2− ligand with different structural motifs have been synthesized and characterized. They show distinct topologies of 3D supramolecular structures in the solid state supported by the combination of coordinative bonds, ligand-supported Ag···Ag interactions, and weak Ag···O/N coordinative interactions or intermolecular hydrogen bonding and aromatic π–π interactions.

4 Experimental

4.1 Materials and physical methods

H2L was synthesized by the literature methods [28], [29]. All other chemicals were commercially available and used as received without further purification. The elemental analyses (C, H, N, and S) were performed on a Perkin-Elmer 240C apparatus. FT-IR spectra were recorded from KBr pellets in the range of 4000–450 cm−1 on a Varian FT-IR 640 spectrometer.

4.2 Synthesis of [Ag2(L)]n (1)

H2L (0.043 g, 0.2 mmol) dissolved in distilled water (5 mL) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of excessive AgNO3 (0.085 g, 0.5 mmol) in ethanol (10 mL). The pH value was adjusted to about 7.0 with 0.1 mol L−1 NaOH solution, and the resulting mixture was stirred at 333 K for 2 h, cooled to room temperature, and filtered. The filtrate was allowed to slowly concentrate by evaporation at room temperature. Two weeks later, colorless block-shaped crystals suitable for X-ray structure analysis were obtained in a yield of 30% (based on Ag). – C6H5Ag2N3O4S (430.93): calcd. C 16.71, H 1.16, N 9.75, S 7.43; found C 17.69, H 1.18, N 9.76, S 7.45. – IR (KBr): ν=1586 (s), 1456 (w), 1398 (s), 1336 (w), 1305 (m), 1223 (m), 1178 (m), 1090 (m), 1045 (w), 1017 (w), 921 (m), 605 (m) cm−1.

4.3 Synthesis of {[Ag2.5(L)(4,4′-bipy)2]· (NO3)0.5·(H2O)4.5}n (2)

H2L (0.043 g, 0.2 mmol) dissolved in distilled water (5 mL) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of AgNO3 (0.085 g, 0.5 mmol) in ethanol (10 mL). The pH value was adjusted to about 7.0 with 0.1 mol L−1 NaOH solution, and the resulting mixture was stirred at 333 K for 2 h. Then 2 mL of an ethanol solution of 4,4′-bipyridine (0.064 g, 0.4 mmol) was added slowly, and the stirring continued for 2 h. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, and filtered. The filtrate was allowed to slowly concentrate by evaporation at room temperature. Two weeks later, colorless block-shaped crystals suitable for X-ray structure analysis were obtained in a yield of 25% (based on Ag). – C26H30Ag2.5N7.5O10S (909.31): calcd. C 34.31, H 3.30, N 11.55, S 3.52; found C 34.32, H 3.28, N 11.57, S 3.50. – IR (KBr): ν=3406 (m), 1598 (s), 1530 (w), 1484 (w), 1404 (s), 1384 (s), 1218 (m), 1174 (m), 1086 (m), 1042 (w), 853 (m), 620 (m) cm−1.

4.4 Crystal structure determinations

Single-crystal data collections were performed on a Bruker Smart Apex II CCD diffractometer with graphite-monochromatized MoKα radiation (λ=0.71073 Å) at 296(2) K. The structures were solved with Direct Methods using Shelxs-97 [30], [31], and structure refinements were performed against F2 using Shelxl-97 [32], [33]. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. Carbon-bound H atoms were placed in calculated positions (dC–H=0.93–0.97 Å) and were included in the refinement in the riding model approximation, with Uiso(H) set to 1.2Ueq(C). The H atoms of coordinating water in 2 were located in difference Fourier maps, and were refined with distance restraints of dO–H=0.85±0.01 Å and H···H 1.387±0.02 Å. Their displacement parameters were tied to those of the parent atoms by a factor of 1.5. The maximum residual electron density peaks of 1.61 e Å−3 for 1 and 1.29 e Å−3 for 2 were located 1.31 Å from the Ag1 atom for 1 and 0.60 Å from the N8 atom for 2. DFIX, SADI, and DANG instructions from Shelxl have been applied to constrain some O–H, N–O and H···H distances in 2. Further details of the structure determinations are summarized in Table 3.

Crystal structure data for 1 and 2.

| Compound | 1 | 2 |

| Formula | C6H5Ag2N3O4S | C26H30Ag2.5N7.5O10S |

| Mr | 430.93 | 1818.62 |

| Crystal size, mm3 | 0.40×0.20×0.12 | 0.30×0.20×0.12 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Triclinic |

| Space group | P21/n | P1̅ |

| a, Å | 5.9211(5) | 10.3159(6) |

| b, Å | 17.2762(14) | 12.7795(6) |

| c, Å | 9.3789(9) | 13.4463(7) |

| α, deg | 90 | 98.729(4) |

| β, deg | 98.457(9) | 97.994(4) |

| γ, deg | 90 | 108.171(5) |

| V, Å3 | 948.97(14) | 945.39(9) |

| Z | 4 | 2 |

| Dcalcd., g cm−3 | 3.02 | 1.85 |

| μ(MoKα), mm−1 | 4.3 | 1.6 |

| F(000), e | 816 | 452 |

| hkl range | –6→7, ±20, ±11 | ±12, –15→14, –16→15 |

| ((sinθ)/λ)max, Å−1 | 0.597 | 0.625 |

| Refl. measured | 7142 | 11 999 |

| Refl. unique/Rint | 1676/0.0599 | 6662/0.022 |

| Param. refined | 145 | 467 |

| R1a/wR2b [I>2σ(I)] | 0.0441/0.1005 | 0.0523/0.1418 |

| R1a/wR2b (all data) | 0.0489/0.1043 | 0.0636/0.1498 |

| GoF (F2)c | 1.07 | 1.098 |

| Δρfin (max/min), e Å−3 | 1.61/–0.94 | 1.29/–0.85 |

aR1=Σ||Fo|–|Fc||/Σ|Fo|.

bwR2=[Σw(Fo2–Fc2)2/Σw(Fo2)2]1/2, w=[σ2(Fo2)+(AP)2+BP]−1, where P=(Max(Fo2, 0)+2Fc2)/3.

cGoF=S=[Σw(Fo2–Fc2)2/(nobs–nparam)]1/2.

CCDC 1481728 (1) and CCDC 1481729 (2) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2014GXNSFAA118035

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2014GXNSFBA118040

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 51402158

Funding statement: This work was supported by the Guangxi Provincial Department of Education (Nos. KY2015ZD130, YB2014414) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (Nos. 2014GXNSFAA118035, 2014GXNSFBA118040). The support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51402158) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also acknowledge the financial support by the Opening Project of Guangxi Colleges and Universities Key Laboratory of Beibu Gulf Oil and Natural Gas Resource Effective Utilization (Nos. 2015KLOG09, 2014PY-GJ05).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Guangxi Provincial Department of Education (Nos. KY2015ZD130, YB2014414) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (Nos. 2014GXNSFAA118035, 2014GXNSFBA118040). The support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51402158) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also acknowledge the financial support by the Opening Project of Guangxi Colleges and Universities Key Laboratory of Beibu Gulf Oil and Natural Gas Resource Effective Utilization (Nos. 2015KLOG09, 2014PY-GJ05).

References

[1] M. P. Komal, E. D. Michelle, T. Thomas, C. M. Stephen, R. H. Lyall, Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 1038.10.1021/acs.cgd.5b01601Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Y. Zhao, N. Kornienko, Z. Liu, C. Zhu, S. Asahina, T. R. Kuo, W. Bao, C. Xie, A. Hexemer, O. Terasaki, P. Yang, O. M. Yaghi, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2199.10.1021/ja512951eSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] G. Zhan, H. C. Zeng, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 3268.10.1002/adfm.201505380Suche in Google Scholar

[4] S. Choi, H. J. Lee, M. Oh, Small2016, 12, 2425.10.1002/smll.201600356Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Z. Wang, X. Y. Li, L. W. Liu, S. Q. Yu, Z. Y. Feng, C. H. Tung, D. Sun, Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 6830.10.1002/chem.201504728Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Y. Zhang, L. Huang, H. Miao, H. X. Wan, H. Mei, Y. Liu, Y. Xu, Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 3234.10.1002/chem.201405178Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] K. Shiva, K. Jayaramulu, H. B. Rajendra, M. Kumar, B. Tapas, J. Aninda, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2014, 640, 1115.10.1002/zaac.201300621Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Q. L. Zhu, Q. Xu, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5468.10.1039/C3CS60472ASuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] J. Wang, Y. Wei, G. Jason, G. Yi, Y. Zhang, Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 15708.10.1039/C5CC06295KSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] S. Xiong, Q. Liu, Q. Wang, W. Li, Y. Tang, X. Wang, S. Hu, B. Chen, J. Mater. Chem. A2015, 3, 10747.10.1039/C5TA00460HSuche in Google Scholar

[11] Z. Zeng, Y. Zhong, H. Yang, R. Fei, R. Zhou, R. Luque, Y. Hu, Green Chem. 2016, 18, 186.10.1039/C5GC00630ASuche in Google Scholar

[12] H. Yang, R. L. Sang, X. Xu, L. Xu, Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2909.10.1039/c3cc40516hSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Y. L. Wang, Q. Y. Liu, X. Li, CrystEngComm2008, 10, 1667.10.1039/b808571dSuche in Google Scholar

[14] H. M. Titi, I. Goldberg, CrystEngComm2010, 12, 3914.10.1039/c0ce00134aSuche in Google Scholar

[15] A. Karmakar, I. Goldberg, CrystEngComm2011, 13, 350.10.1039/C0CE00268BSuche in Google Scholar

[16] G. P. Yang, J. H. Zhou, Y. Y. Wang, P. Liu, C. C. Shi, A. Y. Fu, Q. Z. Shi, Q. Y. Liu, X. Li, CrystEngComm2011, 13, 33.10.1039/C0CE00601GSuche in Google Scholar

[17] S. M. Fang, M. Hu, Q. Zhang, M. Du, C. S. Liu, Dalton Trans.2011, 40, 4527.10.1039/c0dt00903bSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] B. Li, S. Q. Zang, C. Ji, C. X. Du, H. W. Hou, T. C. W. Ma, Dalton Trans.2011, 40, 788.10.1039/C0DT00949KSuche in Google Scholar

[19] Y. L. Wei, X. Y. Li, T. T. Kang, S. N. Wang, S. Q. Zang, CrystEngComm2014, 16, 223.10.1039/C3CE41714JSuche in Google Scholar

[20] H. Schmidbaur, A. Schier, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.2015, 54, 746.10.1002/anie.201405936Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] F. Zhao, H. Dong, B. Liu, G. Zhang, H. Huang, H. Hu, Y. Liu, Z. Kang, CrystEngComm2014, 16, 4422.10.1039/c3ce42566eSuche in Google Scholar

[22] A. Karmakar, H. M. Titi, I. Goldberg, Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 2621.10.1021/cg200350jSuche in Google Scholar

[23] G. P. Yang, Y. Y. Wang, P. Liu, A. Y. Fu, Y. N. Zhang, J. C. Jin, Q. Z. Shi, Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 1443.10.1021/cg901545kSuche in Google Scholar

[24] B. Li, S. Q. Zang, C. Ji, H. W. Hou, T. C. W. Mak, Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 1443.10.1021/cg2015447Suche in Google Scholar

[25] P. X. Yin, J. Zhang, Z. J. Li, Y. Y. Qin, J. K. Cheng, L. Zhang, Q. P. Lin, Y. G. Yao, Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 4884.10.1021/cg9006839Suche in Google Scholar

[26] L. Yang, D. R. Powell, R. P. Houser, Dalton Trans.2007, 36, 955.10.1039/B617136BSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] J. Bernstein, R. E. Davis, L. Shimoni, N. L. Chang, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1555.10.1002/anie.199515551Suche in Google Scholar

[28] S. W. Wright, K. N. Hallstrom, J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 1080.10.1021/jo052164+Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] L. F. Ma, L. Y. Wang, J. G. Wang, Y. F. Wang, X. Feng, Inorg. Chim. Acta2006, 7, 2241.10.1016/j.ica.2005.12.076Suche in Google Scholar

[30] G. M. Sheldrick, Shelxs-97, Program for the Solution of Crystal Structures, University of Göttingen, Göttingen (Germany) 1997.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] G. M. Sheldrick, ActaCrystallogr. 1990, A46, 467.10.1107/S0108767390000277Suche in Google Scholar

[32] G. M. Sheldrick, Shelxl-97, Program for the Refinement of Crystal Structures, University of Göttingen, Göttingen (Germany) 1997.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] G. M. Sheldrick, ActaCrystallogr. 2008, A64, 112.10.1107/S0108767307043930Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

©2016 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Li2Pt3Se4: a new lithium platinum selenide with jaguéite-type crystal structure by multianvil high-pressure/high-temperature synthesis

- RE4B4O11F2 (RE = Sm, Tb, Ho, Er): four new rare earth fluoride borates isotypic to Gd4B4O11F2

- Regioselective C-3 arylation of coumarins with arylhydrazines via radical oxidation by potassium permanganate

- Two new POM-based compounds containing a linear tri-nuclear copper(II) cluster and an infinite copper(II) chain, respectively

- Environmentally benign synthesis of methyl 6-amino-5-cyano-4-aryl-2,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole-3-carboxylates using CeO2 nanoparticles as a reusable and robust catalyst

- Synthesis and structural characterization of Ca12Ge17B8O58

- Synthesis of some new hydrazide-hydrazones related to isatin and its Mannich and Schiff bases

- Purpureone, an antileishmanial ergochrome from the endophytic fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum

- Syntheses and crystal structures of two new silver–organic frameworks based on N-pyrazinesulfonyl-glycine: weak Ag···O/N interaction affecting the coordination geometry

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Li2Pt3Se4: a new lithium platinum selenide with jaguéite-type crystal structure by multianvil high-pressure/high-temperature synthesis

- RE4B4O11F2 (RE = Sm, Tb, Ho, Er): four new rare earth fluoride borates isotypic to Gd4B4O11F2

- Regioselective C-3 arylation of coumarins with arylhydrazines via radical oxidation by potassium permanganate

- Two new POM-based compounds containing a linear tri-nuclear copper(II) cluster and an infinite copper(II) chain, respectively

- Environmentally benign synthesis of methyl 6-amino-5-cyano-4-aryl-2,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole-3-carboxylates using CeO2 nanoparticles as a reusable and robust catalyst

- Synthesis and structural characterization of Ca12Ge17B8O58

- Synthesis of some new hydrazide-hydrazones related to isatin and its Mannich and Schiff bases

- Purpureone, an antileishmanial ergochrome from the endophytic fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum

- Syntheses and crystal structures of two new silver–organic frameworks based on N-pyrazinesulfonyl-glycine: weak Ag···O/N interaction affecting the coordination geometry