Abstract

In the context of sociolinguistic approaches to migration and multilingualism, language biographies have gained increasing prominence, particularly over the past fifteen years. Their significance in the field of migration linguistics lies, among other aspects, in their openness – both as a research method and as a research subject. This article addresses the question of how to appropriately evaluate language biographical data, a topic that has received relatively little scholarly attention to date. The proposed evaluation criteria focus on both content-related units of analysis (language biographical schemas) and linguistic units of analysis (L2 strategies, response modalities). In this context, language biographical interviews with young refugees from Afghanistan, Iran, and Syria serve as the empirical data source.

1 Introduction

With the discursive turn of the 1970s, narratives increasingly came to be recognized as legitimate objects of scholarly inquiry within the humanities and social sciences (Pavlenko 2007). In applied linguistics and second language acquisition research, this development marked a paradigmatic shift – from structuralist and error-focused approaches to speaker-centered perspectives. Autobiographical narratives, particularly those elicited through interviews, gained prominence as a means of accessing subjective language learning experiences within specific social contexts. This shift entailed a move away from understanding language acquisition as a linear, decontextualized process, emphasizing instead the social, ethnic, gendered, and emotional dimensions that shape linguistic development (Pavlenko 2007).

This theoretical reorientation was also reflected in German-speaking research, particularly in linguistic studies on labor migration to Germany. According to Dittmar (2021: 97), the period between 1965 and 1975 marked a “dynamischer Aufbruch” (‘dynamic awakening’) at German universities and within sociolinguistic approaches to language learning. One early example is Keim’s (1978) study on “Gastarbeiterdeutsch” (‘guest worker’s German’), which – although grounded in contrastive linguistics – drew on narrative data to analyze multilingual acquisition processes among migrant workers from Turkey, Italy, and other countries.

In the decades that followed, language biographies became a key instrument in migration linguistics in Germany. Two research perspectives emerged: one focusing on German-speaking minority groups abroad – such as Betten’s (1995, 2010) studies on Jewish Shoah survivors or Wolf-Farré’s (2017) work on German Chileans – and another centered on migrants living within Germany. The latter includes studies on adult learners in integration courses (Graßmann 2011) as well as younger migrants or second-generation youth (Thoma 2018; Ingrosso 2021). In both strands, language biographies serve to reconstruct individual language trajectories, identity processes, and dimensions of social participation. These studies highlight the methodological and epistemological potential of language biographies: they capture language development as embedded in biographical experience and allow insights into language use, dominance, affective meaning, and language ideologies (Riehl 2014: 23–24). Language biographical research thus extends traditional linguistic models by incorporating qualitative, context-sensitive dimensions. A detailed account of the field’s development is provided by Franceschini (2022) in the launch issue of Sociolinguistica.

This article builds on these developments and discusses how language biographies – especially in the context of migration and multilingualism – function both as empirical tools and as independent objects of inquiry. Section 2 introduces a methodological approach to the analysis of oral language biographical data by presenting a four-level analytical model. Section 3 applies this model to selected excerpts from interviews with two migrants from Afghanistan, followed by a cross-speaker analysis based on the quantification of the four analytical levels. The concluding section summarizes the key findings and outlines future directions in language biographical research. In this way, the article introduces a practical analysis framework for the systematic examination of language biographies, incorporating thematic and linguistic-communicative aspects.

2 The model of language biographical analysis

Language biography is a communicative performance negotiated in the context of biographical interviews. It represents a dynamic, context-sensitive structure that condenses individual language experiences and can be reconstructed through qualitative methods. These linguistic autobiographies are shaped by key life stages and language-related experiences – for example, in refugee narratives, by early socialization before flight and linguistic reorientation after migration.

The proposed model builds on the central principle of language biographical research: reconstructing the “innere Logik” (‘inner logic’) of the narrative (Franceschini and Miecznikowski 2004), meaning the interplay between content and linguistic form. While earlier studies emphasized the dialogical and situated nature of language biographical narration, my model advances this perspective by systematically integrating thematic and stylistic dimensions. Language biographies are thus not merely retrospective accounts, but performative expressions shaped by interaction and embedded in specific social contexts.

This approach combines two complementary perspectives. The first, which is interactional-stylistic in nature, draws on Interpretative Sociolinguistics (Selting and Hinnenkamp 1989) and focuses on discursive styles, pragmatic routines, and communicative positioning – especially in multilingual and migration-related contexts. The second extends Franceschini’s (2002: 27) concept of “Figuren sprachbiografischen Erzählens” (‘figures of language biographical narration’) into what I term language biographical schemas: recurring patterns through which speakers structure experiences such as language acquisition, loss, or adaptation. These schemas are dynamic, context-dependent, and provide insights into individual narrative strategies – particularly in situations of displacement and linguistic resocialization.

By linking interactional and structural analysis, the model offers a methodological framework for examining language biographies not only as data, but as acts of performative identity work. The following section outlines how this framework is applied to narrative interview data and what patterns emerge in multilingual biographical storytelling.

The analytical model presented below is based on methodological developments in the field of language biographical studies as well as on my own research (see Holzer 2025). It builds upon key prior work – particularly contributions by Franceschini (2002) and Roll (2003) – but advances these by offering a systematic, four-level framework that integrates linguistic and discourse-analytic perspectives. The model is especially informed by Roll’s typology of narrative response modalities among adolescents with migration backgrounds, while placing greater emphasis on the interaction between language biographical content and its communicative negotiation within the interview setting.

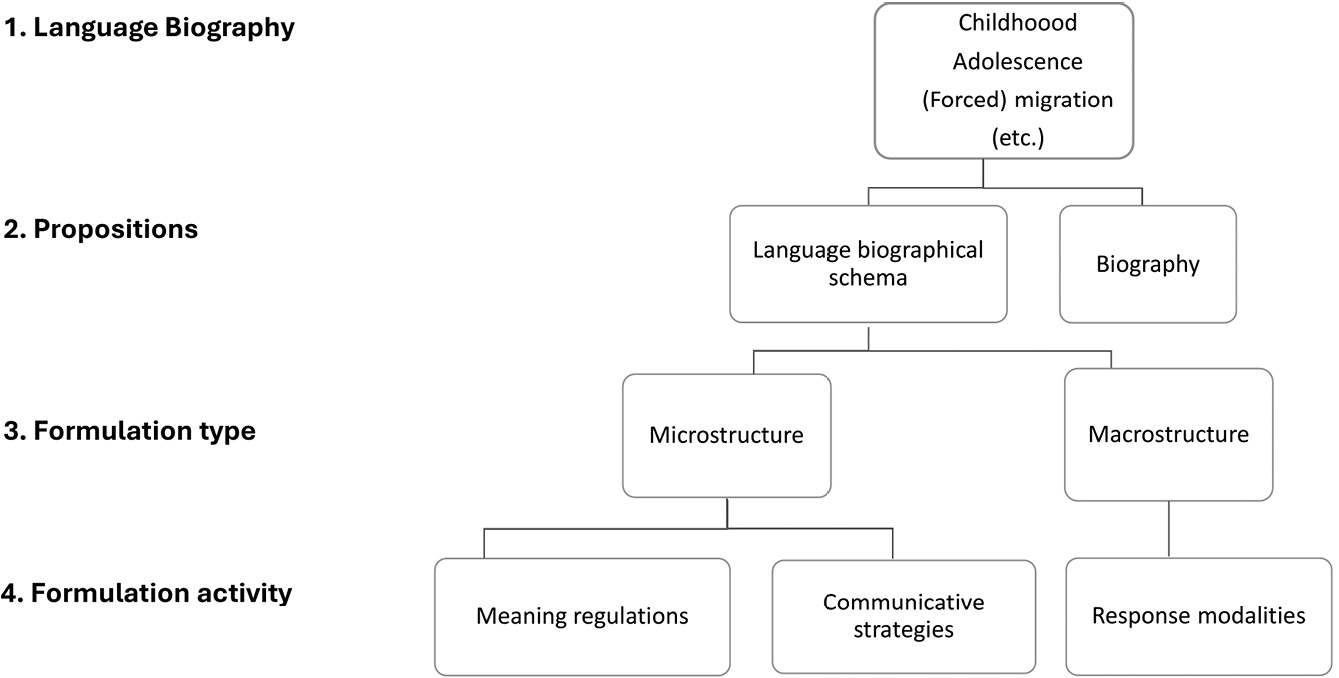

Structured into four interrelated levels, the model of language biographical analysis captures the relationship between the language biography as an object of study and the language biographical interview as a place where meaning is created (see Figure 1 for a visual overview).

The topics addressed in language biographical interviews range from childhood and adolescence to formative experiences in the context of (forced) migration. The analytical focus lies on language-related aspects such as bilingual upbringing, the acquisition of second and foreign languages, and other linguistic constellations that emerge during the course of the interview (Level 1: Thematic Settings of Language Biography).

Propositional content encompasses all statements made by the interviewee, including those not directly related to language (Level 2: Propositions). To filter the material, the model distinguishes between general biographical and explicitly language biographical schemas. Only those schemas with a clear reference to language – such as personal experiences with second language acquisition – are included in the analysis. General memories without a linguistic dimension (e.g., everyday family life) are excluded. The extracted schemas are analyzed for their thematic relevance and discursive structure, the latter of which is further differentiated in the subsequent levels. The formulations are segmented into micro- and macrostructural types (Level 3) and further refined through specific formulation activities (Level 4).

Microstructural meaning regulations capture salient linguistic patterns, such as complex sentence structures (e.g., complement clauses), connectors, discourse particles, or the use of direct speech (Roll 2003: 73).

Microstructural communicative strategies refer to characteristic features of language use observed in the interview, e.g., instances of language mixing. These vary depending on the interview language and the speakers’ linguistic repertoire. At the core of the model is the analysis of lexical and grammatical strategies used to manage formulation difficulties in the second language. The theoretical basis is the concept of L2 Problem-Solving Mechanisms (Dörnyei and Kormos 1998), referred to here as L2-strategies. Such strategies are especially relevant in language acquisition contexts, as they shape verbal expression and provide valuable insights into how speakers navigate multilingual settings.

Macrostructural response modalities, based on the work of Roll (2003), include narration (with narrative establishments, marking the beginning of narration, e.g., in German with the conjunctions als ‘as’ or damals ‘at that time’), description, report, providing information, illustration, chronological representations and justifications. These modalities are derived from microstructural meaning regulations and fulfill different communicative functions – such as affective markers in narrative sequences or argumentative structures in justificatory responses (Roll 2003: 74).

The language biographical analysis model

By combining these four levels, the analysis model enables the systematic segmentation of language biographical schemas, the identification of their linguistic realizations, and the derivation of discursive patterns. In the first step, relevant topics are identified within the interview (Level 1) and transformed into language biographical schemas (Level 2). These are then analyzed with regard to microstructural formulation types (Level 3), such as meaning regulations and communicative strategies, which in turn serve as the basis for determining macrostructural response modalities (Level 4). The model allows for a nuanced narrative and argumentative reconstruction of language experiences – from early childhood to the time of the interview. Its aim is to render the complexity of language biographies methodologically accessible and applicable to both qualitative and corpus-based research.

3 Application of the analytical model

In the following, the proposed model will be exemplified using language biographical data from a study of young refugees from Afghanistan, Iran and Syria (Holzer 2025). First, the background of the study will be presented, followed by a detailed explanation of the analytical procedure. Subsequently, the language biographies of the entire sample will be compared, offering insights for future research in comparative language biography studies.

3.1 Study design

Between April and December 2018, a total of 22 adolescents (15 male, 7 female) were interviewed about their language biographies using a semi-structured format. One year later, follow-up interviews were conducted with ten participants from the initial cohort.

Twelve of the respondents were from Afghanistan, three from Iran, and seven from Syria. At the time of the first survey (2018), they had been living in Germany for an average of two to three years. In the first round of data collection, six interviews were conducted in German with the support of lay interpreters, while the remaining sixteen were conducted in German without such assistance.

During the second round of data collection (2019/2020), ten interviewees who had already participated in the first round were re-interviewed in German. In total, 32 interviews were fully transcribed following the conversation analytic conventions proposed by Selting et al. (2009) and analyzed using the qualitative data analysis software MAXQDA.[1]

Based on the participants’ language biographical schemas, response modalities, and formulation activities, the following research questions are addressed in this article:

To what extent is the proposed language biographical analysis model suitable for mapping multilingual biographies across language groups, particularly with respect to narrative schemas and linguistic formulations?

Which response modalities do late L2-learners employ in the discursive reconstruction of language biographical schemas?

What grammatical and lexical strategies are used by young migrants learning German as a second or additional language – both consciously and unconsciously – during “exolingual” interview situations (cf. Lüdi 1996: 241), in which the interviewer is a native speaker of German and the interviewee is not?

Can the analysis of L2-PSM provide insights into the participants’ language development?

The following analysis of the language biography of an Afghan participant (P9 = participant 9) serves to illustrate how the proposed analysis model can be applied to the verbal reconstruction of language biographical episodes.[2]

3.2 Qualitative analysis

The case of P9 is particularly interesting: although his education in Afghanistan was interrupted during early childhood, he successfully acquired German language skills and secured an apprenticeship in a pharmacy. His migration background illustrates that not only educational experiences play a crucial role in social repositioning within the destination country, but also individual circumstances – such as support from members of the majority society.

At the time of the first interview in 2018, P9 was 22 years old and had lived in Germany as an unaccompanied emerging adult for three years. He attended elementary school up to third grade in Herat, Afghanistan, and speaks standard Dari as well as the Dari dialect Herati. P9 is literate in Persian and Standard Arabic and developed oral skills in Arabic during Quranic schooling. Other languages he has been exposed to include Pashto and English. In public contexts in Afghanistan, he used Dari, while Herati was spoken in private settings.

At the age of 19, he fled to Germany. During the one-and-a-half-month journey, he met an Afghan family whose son spoke English, and they supported him along the escape route using that language.

In Germany, after completing a German integration course, he obtained his qualifying secondary school leaving certificate within a parallel school model (Integrationsklasse ‘integration class’) and continued his education at the Städtische Berufsschule (‘Public Vocational School’). At the same time, he began vocational training as a pharmaceutical commercial employee.

(1) P9_first data collection

|

332 P9: |

äh (--) äh ich hab auch be eins[3] (-) |

|

|

eh (--) eh i have also be one |

|

333 |

alle haben gsagt dass (.)°h wir schaffen nicht |

|

|

everyone said we could (.)°h not do it |

|

334 |

damals als wir diese test geschrieben aber [ab] |

|

|

back then when we took that test but [bu] |

|

335 I: |

[e:cht] |

|

|

[really] |

|

336 |

wer hat das gesagt (.) |

|

|

who said that (.) |

|

337 P9: |

ja viele leute haben da/(.) das war schwierig |

|

|

yes many people have/ (.) that was difficult |

|

338 |

wir haben/wir schaffen das nicht und so und blabla |

|

|

we have/we do not manage it and stuff like that and blah blah |

|

339 |

(lacht) ja °h ja (.) aber ich hab (-) gsagt nein |

|

|

(laughs) yes °h yes (.) but I (-) said no |

|

340 |

wir schaffen es (.)ja (.) und (lacht) ja (-) |

|

|

we manage it (.) yes (.) and (laughs) yes (-) |

|

341 |

die leute haben/(.) die haben gsagt wir schaffen |

|

|

the people have/ (.) they said we do not |

|

342 |

nicht haben nicht geschafft |

|

|

manage have not managed |

|

343 |

aber ich hab gsagt ja wi/ich schaffe es ich hab |

|

|

but I said yes we/ i manage it i have |

|

344 |

geschafft |

|

|

managed |

An important aspect concerning P9’s language learning situation is his self-motivation (language biographical schema 1) to pass level B1 of the German test (referring to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, CEFRL), along with the self-positioning associated with it (339–344, language biographical schema 2). He describes, through other-positioning (337, language biographical schema 3), that everyone – as indeterminate actors – believed he would not pass the test. In response to the interviewer’s questions, P9 attempts to specify these actors by referring vaguely to many people and offering an explanatory yet temporally unstructured description (337). Only later in the excerpt (341) can it be inferred that the actors are classmates or other test takers. The contextualization remains unclear, as P9 positions himself in opposition to the (indeterminate) actors on the one hand, while simultaneously aligning himself with the learner group through the deictic reference we.

As a distancing strategy from this other-positioning, P9 mimics the actors’ perspective by indirectly reproducing their judgment – marked by the use of the general extender and stuff like that (microstructural meaning regulation 1) and the polyphonic phrase blabla (338, microstructural meaning regulation 2). The general extenders have been categorized as a substitutive L2-strategy and are characterized as follows, equally in German and English:

In English, general extenders are typically phrase- or clause-final expressions with the basic syntactic structure, conjunction + noun phrase, which extend otherwise complete utterances (hence ‘extenders’). They are also non-specific in their reference (hence ‘general’) (Overstreet 2005: 1847)

With regard to the frequency in the language biographical data of our participants, the possibility of a continuation that remains unspecified through a general extender is not only used to mark vagueness (cf. König 2014: 209–210), but is also understood as an L2-specific strategy within an ‘economically’ organized learner variety. The high frequency of general extenders has also been observed in learners’ monological sequences. The often-used construction “conjunction + (premodifier) vague expression (postmodifier)” (Tarone 2007: 145) fulfills a similar function to passe-partout expressions in learner language contexts: “Since a vague utterance conveys the implication that more could be said, its use seems to suggest that the speaker treats the hearer as someone who understands the implication” (Terraschke 2007: 143).

According to Tarone (1980: 221), the frequent use of general extenders such as and stuff like that can serve both to economize on speaking time and to avoid potentially delicate subject matter. It should be added that general extenders may also function to circumvent explanatory details in the context of communicative problem-solving mechanisms, especially when they occur within the boundaries of a turn construction unit (TCU) rather than at the end of an utterance.

The use of the onomatopoeic expression blabla is common in colloquial German to mark indirect speech and typically carries pejorative connotations (Finkbeiner 2016: 313). Through this non-autosemantic expression (Finkbeiner 2016: 313), one may infer that the participant has been exposed to informal German input. The causal connections and stepwise structure, particularly in the final section, indicate a descriptive mode of presentation.

(2) P9_first data collection

|

776 P9: |

ja äh äh ungefähr fast die halbes jahr von |

|

|

yes eh eh about almost half the year of |

|

777 |

erstes als ich hier in deutschland war (.) ja |

|

|

first when i was here in germany (.) yes |

|

778 |

°h ich hatte viele probleme und ich konnte nicht/ |

|

|

°h i had many problems and I could not/ |

|

779 |

(.) °hh was soll ich machen und so |

|

|

(.) °hh what should i do and stuff like that |

|

780 |

aber später dann habe ich eine pfarrer im/in eine |

|

|

but later then i have a priest in/in a |

|

781 |

kirche gekennt ja |

|

|

church known yes |

|

782 |

und dann er hat mir dann (-) jemand anders nachhilfe gegeben ja |

|

|

and then he then gave me (-) someone else to tutor me yes |

|

783 |

und dann war ich auch zu xx ja und (.) dann |

|

|

and then i was to xx yes and (.) then |

|

784 |

hab ich so viele leute gekannt später (--) |

|

|

then i knew so many people later (--) |

|

785 I: |

(.) wie hast du den pfarrer kennengelernt (-) |

|

|

(.) how did you meet the priest (-) |

|

786 P9: |

ja ein andrer afghaner haben äh die pfarrer im ubahn getroffen |

|

|

yes another afghan met the priest in the subway |

|

787 |

und die haben uber mich erzählt und dann die pfarrer |

|

|

and they talked about me and then the priest |

|

788 |

hat gesagt (.) ja du kannst ihn mitnehmen und |

|

|

said (.) yes you can take him with you and |

|

789 |

in meine büro einmal kommen und dann war ich dort ja |

|

|

come to my office one and i was there |

|

790 |

(-) ich war letzte woch auch so bei diesem pfarrer |

|

|

(-) i was last week also with this priest |

|

791 |

ja beim pfarrer und äh wir machen jetzt ein projekt |

|

|

yes with the priest and eh we do now a project |

Subsequently, P9 reconstructs an important turning point in his language biography. As König (2018: 15) states for narrative reconstructions of language biographies, language biographical turning points are either implicitly reproduced through direct thought enactments or explicitly evaluated through comments. In the present excerpt, the turning point is implicitly marked by the presentation of thoughts (779) and the general extender and stuff like that (meaning regulation). The preceding restructuring (L2-strategy) and the substitution of information (778–779, L2-strategy), respectively, emphasize the affective character of this reconstructed event, through which P9 positions himself in relation to the rupture caused by his forced migration and arrival in Germany (language biographical schema 1).

The narrative beginning (776) deals with his first half-year in Germany, which was psychologically stressful. P9 elaborates on this aspect only vaguely, using expressions such as and stuff like that and many problems (cf. König 2018: 183), and then transitions into a descriptive, partially chronologically arranged way of speaking. His initially overwhelming demands, which he hints at the beginning, develop into a self-determined approach to learning German (language biographical schema 2) through support from a tutor (782) and the psychological counseling of his forced migration by a specialized institution (783, anonymized with xx).

(3) P9_second data colletion

|

477 P9: |

aber äh (--) wo wir waren in die/in die berufsschule |

|

|

but eh (--) where we went to the/to the vocational school |

|

478 |

a/al/als wir waren wir hatten |

|

|

w/wh/when we were we had |

|

479 |

immer so mit grammatik und (.) schreiben für be zwei |

|

|

always like that with grammar and (.) writing for be two |

|

480 |

oder be eins dort (.) deswegen haben wir auch viel |

|

|

or be one there (.) that is why we have a lot |

|

481 |

gemacht und °hh das ist glaub ich wir haben in die |

|

|

done and °hh that is I think I we do not have in the |

|

482 |

schule kein grammatik jetzt |

|

|

school any grammar now |

|

483 |

oder wir/wir haben eine stunde deutsch |

|

|

or we/we have one hour german |

|

484 |

aber in der woche eine stunde fünfundvierzig minuten |

|

|

but in the week one hour fourty five minutes |

|

485 |

das ist nicht/(-) |

|

|

that is not/ (-) |

|

486 |

und (.) jetzt ist glaub ich schon besser geworde/ |

|

|

and (.) now is i think it has already gotte/ better |

|

487 |

geworden (.) und (.) ich/ich merke auch nicht dass |

|

|

gotten (.) and (.) i/i do not notice either |

|

488 |

äh dass ich schwierigkeit(.)/keite haben weil wir |

|

|

eh that i have difficult (.)/difficulties because we |

|

489 |

schreiben nicht so viel test über (.) |

|

|

do not write that many test about |

This interview excerpt is taken from the conversation with P9 that took place one year later. He now attends vocational school while training to become a pharmaceutical commercial employee. P9 continues the first, biographical interview with a short narrative statement. He describes the change in teaching method (477), meaning his lessons are now less focused on grammar (language biographical schema 1). His use of German as a migration language becomes more natural (481–482). The positive self-assessment of his language skills (486–487) is also evident in the implicit comparison with previous experiences with German in the classroom. Less teaching time is devoted to the German language (483–484), which he explicitly evaluates as a turning point. However, he breaks off this evaluation with that is not/ (-) (485).

P9 has developed linguistically, despite the reduced amount of teaching time. The subsequent relativization of his self-assessment (language biographical schema 2) is based on the fact that his language skills are no longer tested in school exams (488–489). The illustrative comparisons between the earlier and later language learning situations in German, characterized by restructuring (L2-strategy), make it evident that the German language has become a more integrative part of his language biography at the time of the survey. This is also evident at the microstructural level: when reconstructing his memories of German lessons in the vocational integration class, P9 uses a paratactic argument structure (479–481, response modality: giving information). He describes the former, guided lessons using a so-called dense construction (478–479), that is, a construction of everyday narrative that typically forms a fragment of an utterance or an elliptical structure (Günthner 2006: 97).

The various steps of qualitative analysis illustrated in this case study were applied to the language biographical interviews of the entire sample and summarized in a group comparison. The results of this analysis will be presented in the following.

3.3 Quantitative analysis

The following quantitative analysis of the individual language biographical schemas, the response modalities and the L2-strategies demonstrates in what way a group-specific overview of language biographies can be used for Comparative Language Biography Research. This analysis focuses exclusively on the longitudinal subcorpus – that is, the ten individuals who participated in both the first and second round of data collection – as only these cases allow for reliable comparative linguistic analysis over time. The quantitative presentation of linguistic biographical schemas will concentrate on the above-mentioned categories, while other subcategories formed for each individual schema (coded in MAXQDA) cannot be discussed within the scope of this paper (see Holzer 2025 for more details).

3.3.1 Language biographical schemas

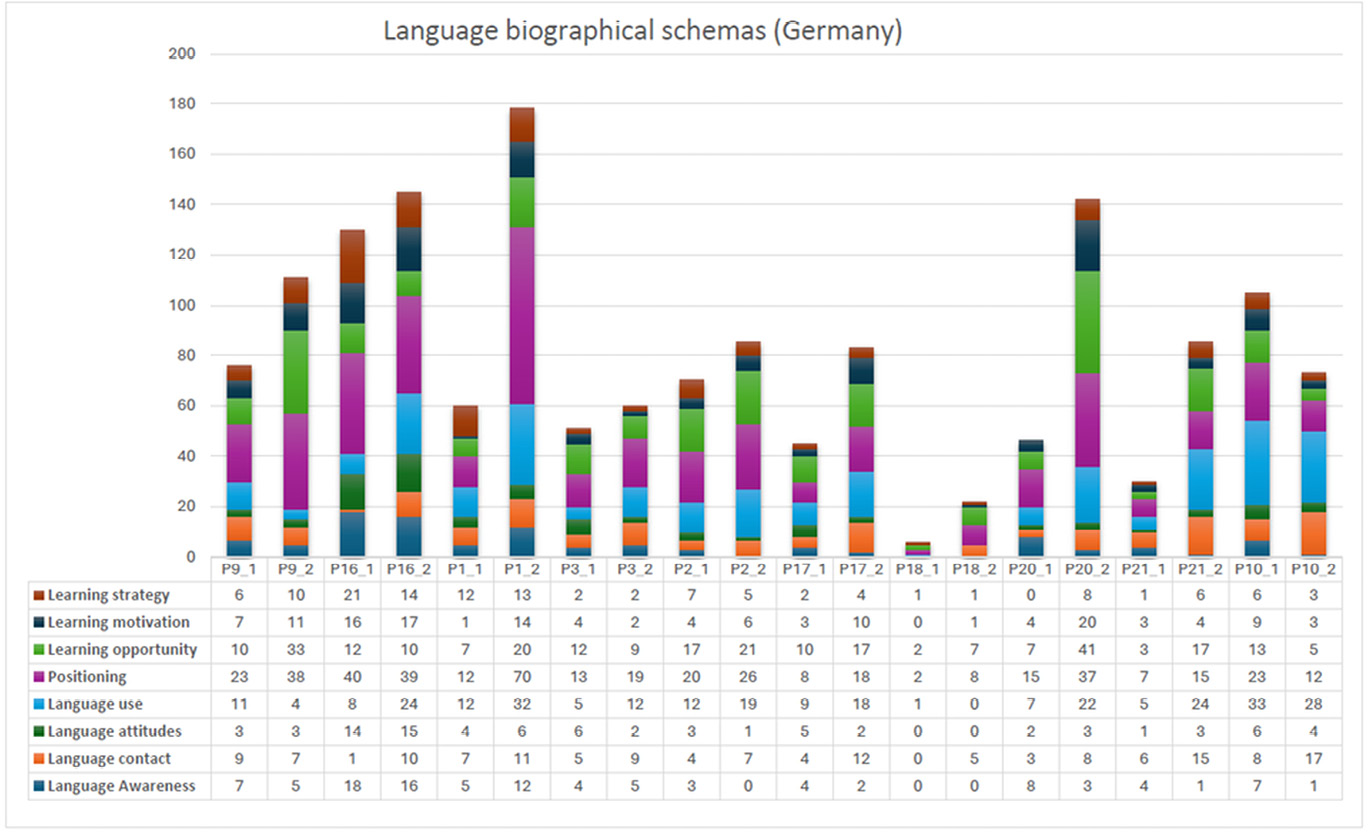

Referring to language biographical motifs related to their lives in Germany, young refugees primarily mentioned schemas that are related to positioning processes (see Figure 2). In addition, learning opportunities in Germany and the associated schemas of language learning motivation and language learning strategies were also addressed. The latter narrative schemas in particular illustrate how the language biographies are shaped by forced migration, since the prospects of staying are also dependent on language competence. The external conditions of migration and language policy that are at work also have an effect on language learning motivation and corresponding language learning strategies. In varying degrees, the answers refer to language use, language attitudes, language contact and language awareness.

This language specific reference and its linguistic realization have so far received only limited attention in language biography research (Graßmann 2011). Language attitudes, which are mentioned in many language biographical studies, play a less prominent role in the present sample (Riehl 2014; König 2014). Common to all language biographies is the reference to language use and language contact situations in Germany. With the exception of P18, whose prospects of staying in Germany were uncertain and who had hardly any contact with the German language, the participants predominantly focused on German language use and language contact situations in Germany. It is notable that language acquisition contexts and language contact situations, which have previously been a central focus of language biography research from the perspective of the speakers, are rather marginal – particularly concerning experiences in the country of origin. This suggests that the speakers in the study avoid naming the related, personal environment. In addition, the educational biographies of the young refugees were often interrupted by the warlike and oppressive circumstances prevailing in their countries of origin. Language attitudes regarding the respective L1 and L1 varieties in the context of a new multilingual situation in Germany only played a marginal role. Unanimously, the respondents included their respective dialects in their multilingual repertoires (e.g., Hazaragi or Herati).

The following graph (Figure 2) gives an overview of the frequencies of the respective schemas across speakers at the two data collection points.

Language biographical schemas (code frequencies in segments)

When comparing the first (e.g. P9_1) and second (e.g. P9_2) interviews, there is a notable increase in the density and differentiation of language biographical schemas for several participants (e.g., P9, P10, P20). For instance, P9 shows a marked rise in positioning statements (from 23 to 38) and learning opportunities (from 10 to 33), indicating a growing reflexivity regarding their own language learning process and their positioning in the new environment. Similarly, P10 exhibits consistent attention to language use (from 23 to 28) and contact (from 8 to 17), suggesting a more active engagement with their German-speaking surroundings.

The data of participant P20 are particularly salient: while P20_1 reflects a rather limited range of schema references, the second interview (P20_2) shows the most pronounced increase across all categories, particularly in positioning (37), learning opportunity (41), and language motivation (20). This shift likely reflects not only increased linguistic competence, but also a growing recognition of the sociolinguistic requirements in the new social context.

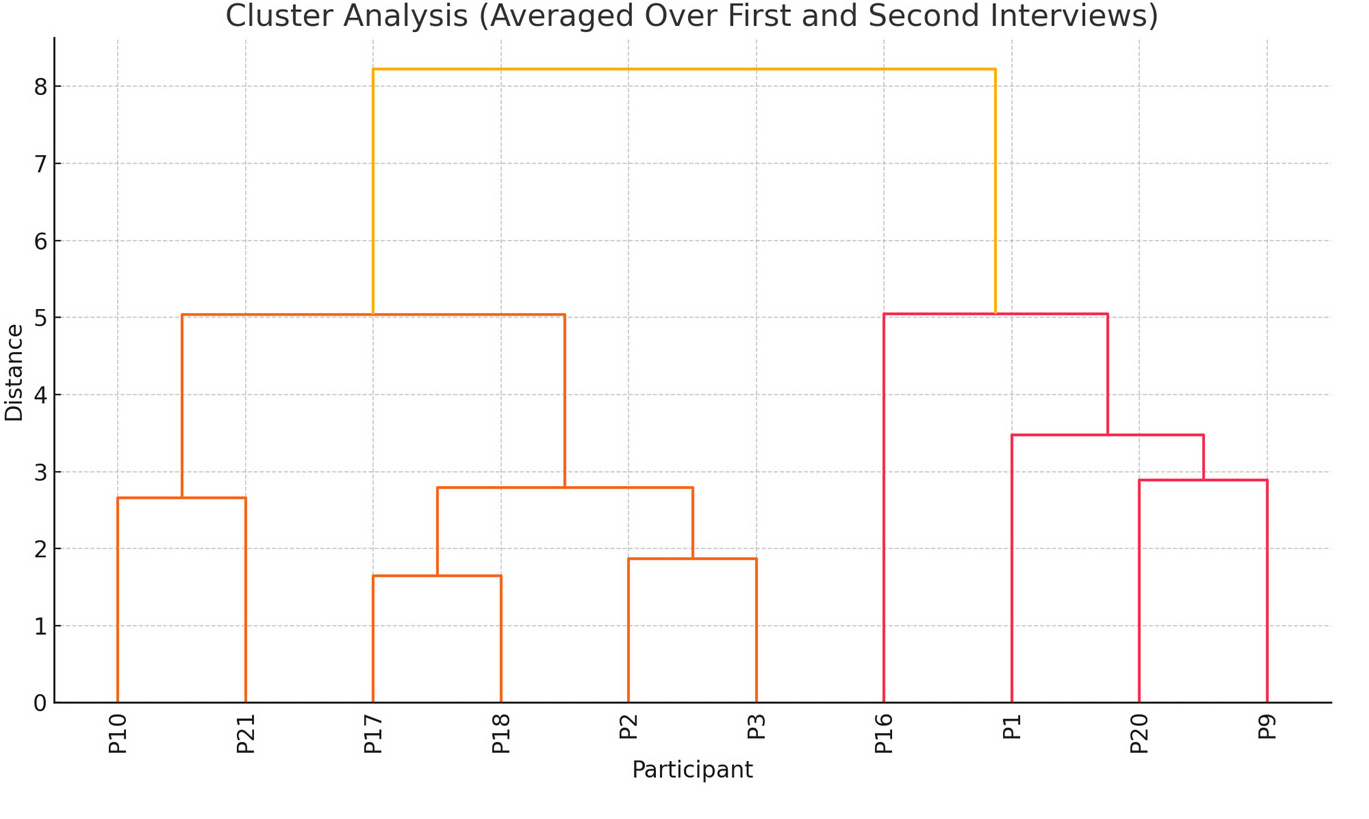

In order to further substantiate these findings and identify broader patterns across participants, a hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted based on the aggregated distribution of language biographical schemas at both data collection points (Figure 3).

Three main participant clusters can be identified, each characterized by distinctive language biographical profiles.

Cluster 1: Participants with highly positioning- and opportunity-oriented language biographies (P1, P9, P20): This cluster is characterized by particularly high values in the categories of positioning, learning opportunity, and language use. Participants in this group narrate their language biographies in close relation to biographical transitions such as forced migration, educational integration, and the linguistic negotiation of their role within the host society. A central feature of these narratives is a strong emphasis on language as a means of accessing education, participation, and future prospects. The prominent positioning schema indicates a reflective stance toward their own migration biographies.

Cluster 2: Participants with balanced schema distributions and moderate differentiation (P10, P21, P16): The second cluster comprises participants whose language biographies display a more balanced and distributed pattern across multiple categories. Although learning strategy and language contact are prominent in this group, no single schema clearly dominates. These participants present intermediate profiles, combining motivational and usage-related elements without explicitly highlighting them through strong narrative or evaluative language. P16 in particular shows higher awareness-related content while engaging less in explicit positioning, suggesting a more cognitively or introspectively oriented profile.

Cluster 3: Participants with reduced thematic elaboration and fragmentary profiles (P2, P3, P17, P18): Participants in the third cluster exhibit overall lower schema frequencies, especially in reflexive categories such as language awareness and language attitudes. Their language biographies appear less elaborate or developed, often characterized by descriptive or fragmented statements. It is plausible that biographical discontinuities, emotional distance, or linguistic insecurities result in language-related experiences being less narratively structured or contextualized. Lower values in learning motivation and learning opportunity may also point to limited access to formal education or weaker institutional support structures.

Language biographical profiles

The cluster analysis reveals that, despite individual variation, typical patterns in the structuring of language biographical narratives can be identified. These patterns correlate with factors such as narrative reflexivity, positioning strategies, and institutional access to education.

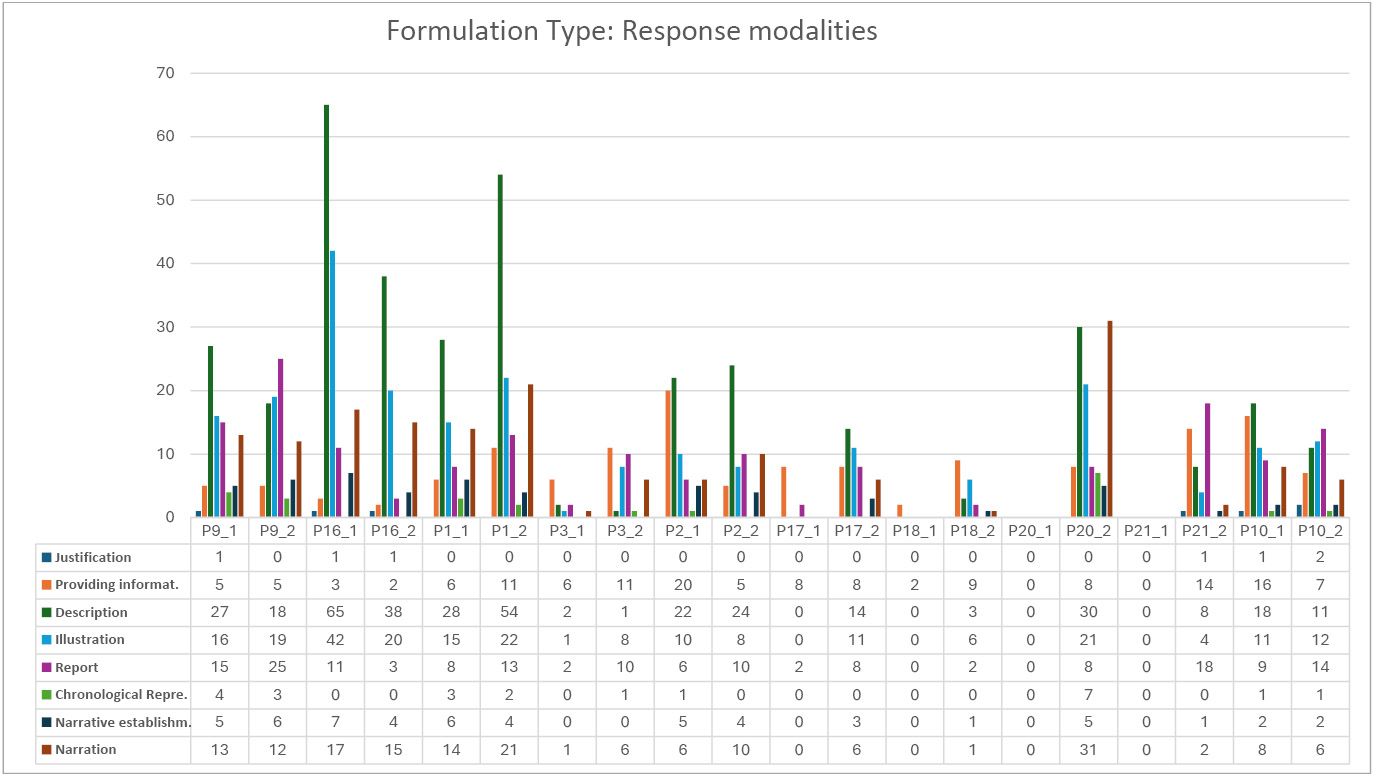

3.3.2 Macrostructural response modalities

The overview of the response modalities used in the linguistic reconstruction of the narrative schemas illustrates that primarily the non-narrative response modalities of depicting and illustrating were employed (see Figure 4). This finding implies that the microstructural regulation of meaning follows a topical structure (Roll 2003: 73), which tends to be temporally unstructured. This result is further supported by the respondents’ tendency to refrain from providing a temporal, chronological account of their language biographical self-image. The descriptive responses regarding the content-related, language biographical categories often include contrasting comparisons between the period before and after migration, as well as between the respective country of origin and Germany as the recipient country. The microstructural regulation of meaning is characterized by generalizing expressions and the use of the present and past tenses in a generalizing mode (Roll 2003: 73). The qualitative examination of the data showed that in this context general extenders such as und so (‘and stuff like that’) or focus particles (so, ‘such’) were frequently used and the semantically induced vagueness contributed to the generalization of the language biographical proposition.

Sub-patterns of the language biographical reconstructions include reporting and informing answers. Here, sentences with the expletive it and passive constructions play a lesser role; instead, sequences of actions, coordinated through universal connectors, are employed (Breindl 2016: 53).

Although one would typically expect a chronological structure in language biographical autobiographies, such accounts occurred only infrequently. Justificatory response modalities also appeared less frequently. Narrative elements influenced the respondents’ response modalities in varying ways, while the narrative mode was employed only rarely. The language biographies of P9, P1, P16, and P20, in particular, are characterized by narrative response elements.

The following figure (Figure 4) illustrates the frequencies of macrostructural response modalities at the two points of data collection.

Macrostructural response modalities (code frequencies in segments)

This becomes particularly evident when comparing the two interviews conducted with these participants. While P16_1 already exhibited high frequencies of descriptive (65) and illustrative (42) responses, in P16_2, the use of descriptive formulations significantly decreased (38), whereas narration (14) and justification (1) remained low. Similarly, P9_1 employed 27 descriptive and 16 illustrative responses, while P9_2 showed a slightly more balanced usage (18/19), along with an increase in reporting responses (from 15 to 25).

Particularly striking is the case of participant P1, who produced a markedly higher number of descriptive responses in the second interview (54 in P1_2 compared to 28 in P1_1), accompanied by a notable increase in illustrative (22) and reporting utterances (13). In contrast, P20, who had minimal verbal elaboration in the first, interpreter-supported interview phase (Description: 0, Narration: 1), showed a marked increase in the second interview phase, conducted without interpreter support (Description: 30, Narration: 31, Illustration: 21). This makes this case the most pronounced example of development in narrative response modalities between the two data collection phases.

A possible explanation is that the response modalities tend to be generalizing and are temporally unstructured. Speakers largely avoid chronologically presented accounts of language biographical experiences in the country of origin. This is also related to sensitive topics of forced migration, the causes of forced migration and the psychosocial situation of the respondents. Direct informative reconstructions are observed less frequently, and the same applies to the resolution of an evaluation conflict – both towards oneself and towards the interlocutor.

The following microstructural meaning regulations are crucial for the construction of language biographical narratives influenced by forced migration: then–today oppositions, as well as earlier–now oppositions, generalizations, and fragmentary summaries (Roll 2003: 80). The facts described are organized according to their relevance. Linked to the structuring and sequential coordination of speech acts are characteristic knowledge structures, such as evaluating (describing) and substantiating or refuting claims (illustrating).

Despite variations in microstructural forms related to the coordination of speech acts, such as different sentence-linking procedures, the most frequent macrostructural response modalities are evenly distributed across all ten language biographies. For instance, as the sociodemographic data indicate, interviewees P1, P9, and P16 each have different educational backgrounds. P9 completed school in Afghanistan up to the third grade, while P16 attended secondary school up to the 9th grade in Syria. P1 also attended school in Afghanistan and was later tutored privately. Thus, it can be assumed that the educational background the respondents brought with them has less influence on their verbal response modalities. Based on the described language biographical experiences, we may presume that factors such as learning opportunities, language learning motivation, and external or family support also impact language acquisition processes. Meister (1997) arrives at similar conclusions in her study on the biographical transitions of adolescent migrants from Poland, highlighting that the ‘acculturation career’ of young people is shaped by a variety of factors: The family background, the age of the interviewees and the specific biographical situation associated with it, the integration into peer groups, the school and educational situation, future prospects and self-identification.

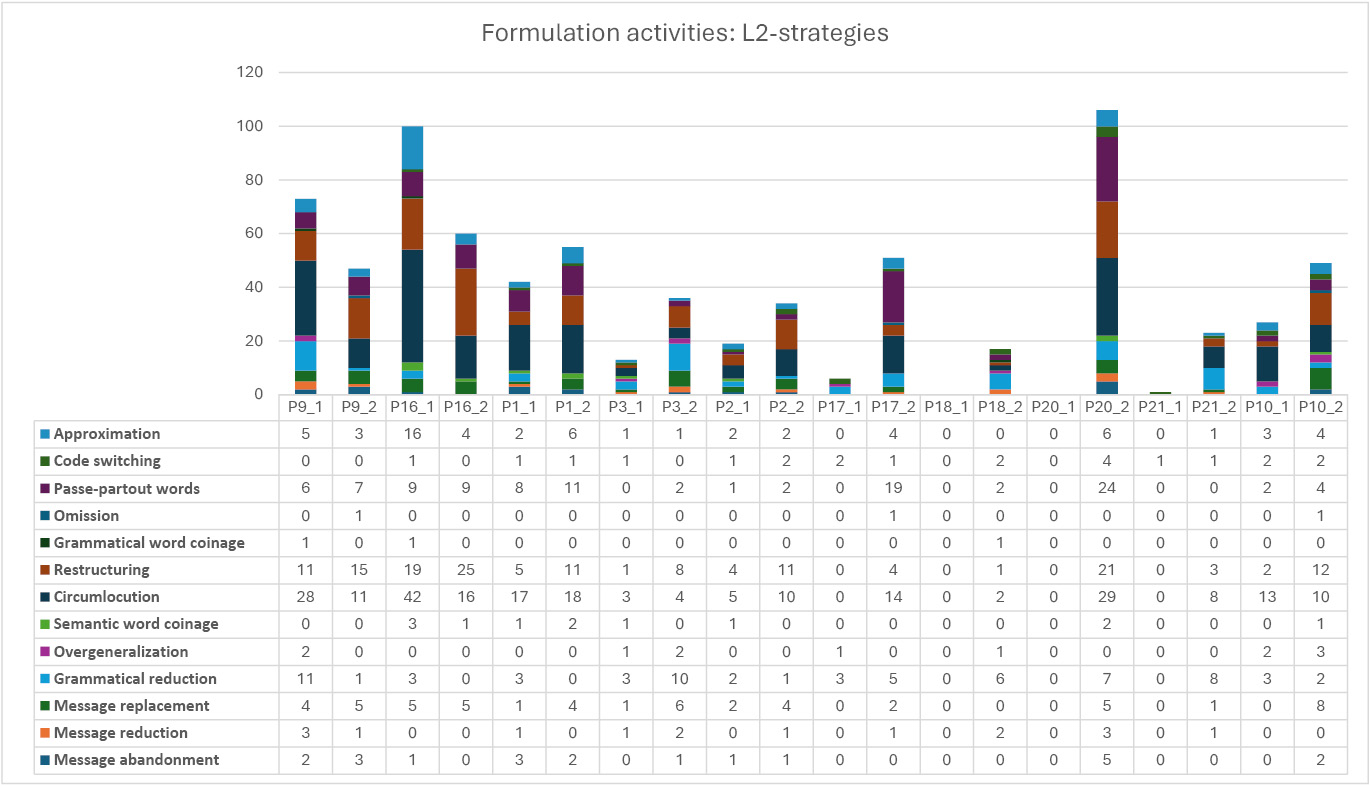

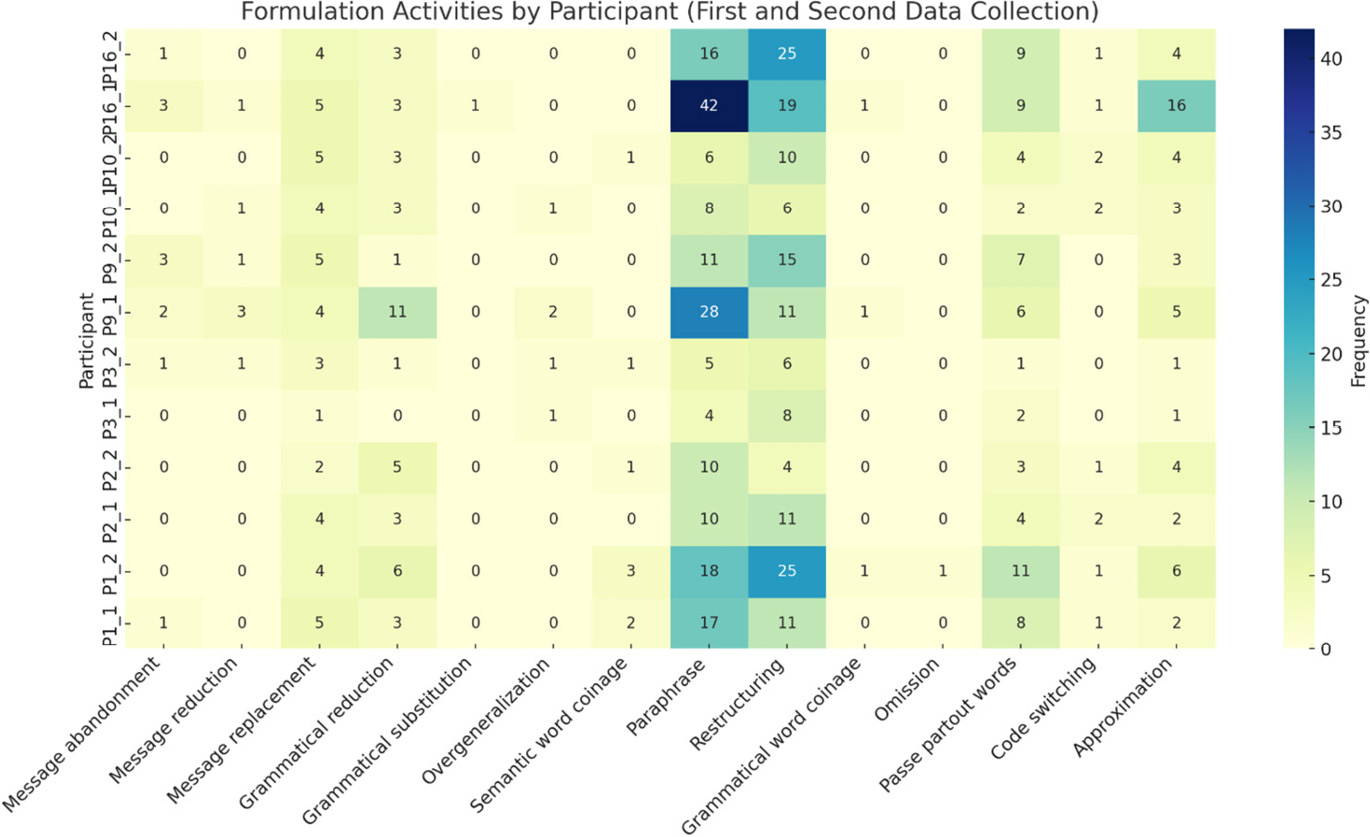

3.3.3.1 L2-strategies of first data collection

Following Poulisse and Schils (1989), the lexical strategies are divided into two domains: superordinating strategies, which replace missing words directly, and subordinating strategies, which involve further problem-solving for unresolved lexical gaps. Poulisse and Schils (1989) showed that the use of L2-strategies depended more on the type of verbal interaction (e.g., picture description, retelling, or free interview) than on linguistic competence. More proficient L2 speakers tended to use holistic strategies like approximation and relied less on transfer strategies during free interviews. It was found that regardless of language proficiency, L2 speakers used holistic (e.g., lexical approximations) and linguistic (morphological creativity, transfer strategies) strategies especially in retelling and free interviews, and analytical strategies (paraphrasing) in picture descriptions. As shown in Figure 5, our data confirm these findings: the study group predominantly relies on macro-reconceptualizations such as approximations, passe-partout words, and restructurings. However, micro-reconceptualizations are also employed, including analytical strategies like paraphrasing, semantic or grammatical coinages, and grammatical reductions. A more detailed picture of linguistic-communicative learning strategies emerges from the analysis of the longitudinal data.

L2-strategies

For instance, participant P16, who exhibits the highest number of formulation activities overall, used a wide range of L2-strategies already in the first interview (P16_1), including paraphrasing (42), restructuring (19), and approximation (16). In the follow-up interview (P16_2), there is a notable decrease in all three strategies (paraphrasing: 16, restructuring: 25, approximation: 4), possibly indicating a shift toward more fluent or economical verbal planning. In contrast, participant P9 showed a relatively stable but slightly reduced use of L2-strategies from P9_1 to P9_2, including paraphrasing (from 28 to 11) and restructuring (11 to 15).

Participant P1 presents a different development: the first interview (P1_1) already includes a wide use of paraphrasing (17) and passe-partout words (9). In the second interview (P1_2), these values increase (paraphrasing: 18, passe-partout words: 11) alongside a rise in restructuring (from 11 to 25). This suggests not only greater fluency but also an increased effort to reframe and clarify utterances linguistically– possibly reflecting enhanced metalinguistic awareness or strategic planning.

By comparison, participants such as P2 and P3 demonstrate a narrower range of strategies across both interviews, often relying on a few stable mechanisms like grammatical reduction, message replacement, and paraphrasing. These patterns may be linked to less confident language use or to limited access to complex formulation activities.

Overall, the interindividual variation and longitudinal developments confirm that L2-strategies in biographical interviews are not only indicators of linguistic competence, but also reflect familiarity with the interview format, topic sensitivity, and individual coping mechanisms. The dominance of paraphrasing and restructuring across nearly all cases – regardless of proficiency – aligns with Poulisse and Schils’ findings, while approximations and grammatical reductions remain essential tools in contexts of lexical uncertainty. The data suggest that learners draw on both analytical and holistic strategies in order to ensure narrative continuity under conditions of linguistic limitation.

3.3.3.2 Longitudinal perspective: L2-strategies

To analyze the interdependence between language competence and the use of different types of L2 strategies, the strategies employed by the six participants who spoke German in both surveys (P9, P1, P16, P3, P2, P10) will now be examined in more detail. We assume that due to the length of stay, schooling, and appropriate input, the language skills of all six speakers had improved at the time of the second survey. As the comparison shows, the speakers predominantly apply mechanisms at the level of macro- and micro-reconceptualization and substitution. The L2-learners speaking in German in their interviews used more paraphrasing at the first data collection point than at the second. This overall decline is clearly visible in Figure 6, which illustrates the frequencies of L2 strategies at the two points of data collection.

For instance, P16 shows a marked decrease in paraphrasing (from 42 to 16), P9 drops from 28 to 11, and P10 slightly decreases from 8 to 6. P1, by contrast, maintains a nearly stable level (17 to 18), while P2 and P3 show consistently low values across both data points.

An exception to the general pattern is observed in P1 and P3, as both participants used fewer L2-strategies in both interviews. This may be due to regular language contact with L1 speakers of German in the private sphere, as both speakers indicated in their interviews. Following Poulisse and Schils (1989), an increase in paraphrasing as a specific L2-strategy is often related to lower lexical proficiency. Hence, the reduced use of paraphrasing may be interpreted as an indicator of increasing lexical and pragmatic competence.

A similar tendency is visible in the reduction of grammatical problem-solving strategies. Grammatical reduction decreases for P9 (from 11 to 1), P16 (3 to 0), and P2 (4 to 2). In P1, however, an increase is observed (from 3 to 6), which may reflect a more conscious strategy to reduce utterances in complex syntactic structures. Grammatical substitutions, on the other hand, are almost entirely absent in the second round across all six speakers, suggesting increasing confidence in morphosyntactic accuracy.

L2-strategies

While these declines indicate a reduced need for analytic strategies, the use of restructuring increased substantially in the second round of data collection for most speakers. As demonstrated in Figure 6, restructuring frequencies rise from 11 to 15 for P9, from 19 to 25 for P16, and from 11 to 25 for P1. This suggests that more proficient speakers increasingly rely on discourse-level planning strategies rather than lexical repair alone. P2 and P10 also show moderate increases, whereas P3 remains relatively stable at a low level.

Regarding approximations, the trend is heterogeneous. While some participants such as P1 and P2 increase their use of this strategy (P1: 2 to 6; P2: 2 to 4), others like P9 and P16 reduce it (P9: 5 to 3; P16: 16 to 4). This may suggest improved lexical precision, reducing the necessity of approximation as a communicative tool. Notably, P9 reports reaching B2 level competence by the time of the second interview, which supports this interpretation.

A more consistent pattern is found in the increased use of passe-partout words. In Figure 6, it becomes evident that all six speakers either maintain or increase their use of general extenders. For example, P1 increases from 8 to 11, P2 from 4 to 6, and P10 from 2 to 4. These elements may be interpreted as markers of increased colloquial fluency and genre awareness, indicating that these speakers adopt discourse strategies common among native speakers.

In summary, Figure 6 illustrates that the competent L2-speakers rely less on lexical and grammatical repair strategies over time, while at the same time employing more discourse-oriented strategies such as restructuring and passe-partout expressions. This supports the hypothesis that more advanced speakers use fewer compensatory strategies, and rely instead on holistic and macro-structural repair mechanisms.

Thus, the respondents can be considered competent speakers for two reasons: First, the total number of lexical and especially grammatical L2-strategies in the language biographical interview is relatively low: “It appeared that ‘proficiency level’ is inversely related to the number of compensatory strategies used by the subjects: the most advanced subjects used fewer compensatory strategies than did the least proficient” (Poulisse and Schils 1989: 15, emphasis in original).

Second, due to the exolingual conversational setting, transfer-based strategies such as code-switching are used rarely. In isolated cases, some speakers resorted to English as their first foreign language (e.g., P2 and P10) by using insertions (cf. Muysken 2000: 679), but these remained marginal.

The decrease in lexical approximations across most participants suggests an increase in lexical knowledge between the two survey waves. The longitudinal comparison also reveals that not only the quantity, but the quality of L2-strategies employed serves as an indicator of language development. Further research with a broader sample and repeated longitudinal interviews would help to clarify how different types of L2-strategies correlate with stages of language acquisition.

Linearity in the use of L2-strategies cannot be assumed, as both this data and the study by Poulisse and Schils (1989) demonstrate. Instead, the variation in individual profiles and strategy preferences points to the need for a more nuanced taxonomy that incorporates both learner type and situational variables.

4 Conclusion

The aim of the qualitative and quantitative analysis was to evaluate the Language Biographical Analysis Model by systematically describing the migration-related language biographies of young refugees from Syria, Iran, and Afghanistan. The findings demonstrate that the model is well-suited to capturing these experiences both on the level of individual speakers and in terms of group-based patterns. The qualitative analysis of participant P9 and the comparative application of the model to ten selected cases confirm that the proposed analytical levels effectively bridge thematic narrative schemas and linguistic formulation processes, thus enabling the integration of individual trajectories into broader comparative insights.

The interview data reveal that language biographical schemas frequently revolve around language experiences in relation to learning opportunities, positioning processes, and domain-specific language use. These dimensions are strongly shaped by migration-specific conditions and should be further integrated into future models of language acquisition to provide more nuanced explanatory approaches.

The analysis of macrostructural response patterns shows that late L2 learners predominantly rely on non-narrative response modalities, such as descriptive and illustrative formulations, in reconstructing their language biographies. These response types appear to require lower cognitive processing demands and point to a thematic, rather than chronological, structure of meaning-making. This is supported by the observed tendency among participants to avoid linear-temporal reconstructions of their linguistic biographies. Instead, contrastive references – between the time before and after migration, and between the country of origin and Germany – predominate. This aligns with findings by Meister (1997) and Roll (2003), who observed that descriptive and argumentative modes often dominate when narrating in a second language.

However, in the present study, those participants who already used German during the first interview displayed a clear shift toward narrative reconstruction in the follow-up interview. This suggests that narrative practices are not solely linked to language proficiency, but may be strongly influenced by thematic salience and emotional accessibility (cf. Holzer 2025).

On the level of formulation strategies, the participants’ utterances are primarily shaped by communicative L2 problem-solving mechanisms (L2-strategies) that aim at preserving communicative flow. These include paraphrasing and lexical approximation, which – according to Poulisse and Schils (1989) – are indicative of more proficient speakers. The results thus confirm their hypothesis that greater lexical control correlates with the use of targeted lexical strategies, whereas less proficient speakers tend to rely on holistic or non-verbal mechanisms. Analytical and holistic strategies predominate, while linguistic transfer strategies (e.g., code-switching or insertions) are used far less frequently (cf. Poulisse and Schils 1989: 15).

Overall, the findings underscore the potential of language biographical interviews as a methodologically rich format for identifying and analyzing L2-strategies in exolingual interaction. Contrary to the marginal attention linguistic-communicative strategies have received in discourse and interactional linguistics, the present data show that these mechanisms are crucial for understanding language learning trajectories in migration contexts.

By analytically distinguishing between language biographical schemas and linguistic formulation activities, the model enables a meaningful integration of qualitative and quantitative insights and allows for the examination of individual and collective dimensions of language biographical meaning-making.

5 Future perspectives

As outlined at the beginning of this article, scholarly interest in language biographies has grown in recent years, particularly in relation to migration and displacement. On the one hand, language biographical research is becoming increasingly thematically focused, as demonstrated in this study through the lens of forced migration. On the other hand, the field is faced with the growing need for theoretical and methodological frameworks capable of capturing both individual biographical narratives and sociolinguistic processes of change at the group level – especially within the broader context of language acquisition and multilingual development.

A central challenge for the continued advancement of language biography research lies in developing analytical models that provide comparability across speakers and contexts without undermining the openness, narrative orientation, and contextual sensitivity that characterize the field. This includes reconciling individual meaning-making with patterns that can be generalized or made analytically productive across cases.

Moreover, language biography research holds considerable potential for illuminating processes of both social and linguistic transformation – particularly in migration contexts, which continue to define the sociopolitical landscape of the present. The dynamics of mobility, displacement, and reorientation necessitate analytical approaches that are both empathic and structurally robust, able to capture subjective perspectives while also reflecting institutional, societal, and discursive constraints.

Future research will therefore need to engage more systematically with questions of data generation, methodological triangulation, and analytical comparability. This includes a critical reflection on how language biographical data are produced, interpreted, and contextualized. The model proposed in this article represents an initial attempt to systematically link language biographical schemas with processes of linguistic formulation work, thereby enabling analyses on both individual and collective levels.

It is hoped that this approach contributes to the methodological advancement of language biography research and opens up new perspectives for studying multilingualism in contexts of migration and mobility – contexts in which language plays a central role as a site of memory, negotiation, and transformation.

References

Betten, Anne & Miryam Du-Nour. 1995. Wir sind die Letzten. Fragt uns aus. Gespräche mit den Emigranten der dreißiger Jahre in Israel. Gerlingen: Bleicher.Suche in Google Scholar

Betten, Anne. 2010. Sprachbiographien der 2. Generation deutschsprachiger Emigranten in Israel. Zur Auswirkung individueller Erfahrungen und Emotionen auf die Sprachkompetenz. In Rita Franceschini (ed.), Sprache und Biographie, 29–57. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler.10.1007/BF03379843Suche in Google Scholar

Breindl, Eva. 2016. Konnexion in argumentativen Texten. Gebrauchsunterschiede in Deutsch als L2 vs. Deutsch als L1. In Franz d’Avis & Horst Lohnstein (eds.), Normalität in der Sprache. (Linguistische Berichte – Sonderhefte 22), 37–64. Hamburg: Buske.Suche in Google Scholar

Dittmar, Norbert. 2021. Die Anfänge der Zweitspracherwerbsforschung in der BRD. Die Gemengelage des gesellschaftlichen Umbruchs (1960er und 1970er Jahre) in ihren Auswirkungen auf einen soziolinguistischen Aufbruch am Beispiel der Projekte HPD und P-Moll. In Bernt Ahrenholz & Martina Rost-Roth (eds.), Ein Blick zurück nach vorn. Frühe deutsche Forschung zu Zweitspracherwerb, Migration, Mehrsprachigkeit und zweitsprachbezogener Sprachdidaktik sowie ihre Bedeutung heute, 97–120. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110715538-004Suche in Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Zoltán & Judit Kormos. 1998. Problem solving mechanisms in L2 communication: A psycholinguistic perspective. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 20(3). 349–385. https://doi.org/10.1017/S027226319800303910.1017/S0272263198003039Suche in Google Scholar

Franceschini, Rita & Johanna Miecznikowski (eds.). 2004. Leben mit mehreren Sprachen / Vivre avec plusieurs langues. Sprachbiographien / Biographies langagières. Bern: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Franceschini, Rita. 2002. Sprachbiographien: Erzählungen über Mehrsprachigkeit und deren Erkenntnisinteresse für die Spracherwerbsforschung und die Neurobiologie der Mehrsprachigkeit. Bulletin VALS-ASLA 76. 19–33.Suche in Google Scholar

Franceschini, Rita. 2022. Language biographies. Sociolinguistica 36(1–2). 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1515/soci-2022-001510.1515/soci-2022-0015Suche in Google Scholar

Graßmann, Regina. 2011. Zwei- und Mehrsprachigkeit bei Integrationskursteilnehmern. Eine sprachbiografische Analyse. Frankfurt a. M.: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Günthner, Susanne. 2006. Grammatische Analysen der kommunikativen Praxis – ‚Dichte Konstruktionen‛ in der Interaktion. In Arnulf Deppermann, Reinhard Fiehler & Tomas Spranz-Fogasy (eds.), Grammatik und Interaktion, 95–121. Mannheim: Verlag für Gesprächsforschung. http://www.verlag-gespraechsforschung.de/2006/pdf/grammatik.pdf (accessed 8 August 2025)Suche in Google Scholar

Holzer, Johanna. 2025. Sprachbiographien. Junge Geflüchtete aus Afghanistan, Iran und Syrien. Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-70576-6.10.1007/978-3-662-70576-6Suche in Google Scholar

Ingrosso, Sara. 2021. Sprachbiographische Erzählungen junger Italiener in München: postmoderne Migrationsformen aus linguistischer Perspektive. München: Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. https://doi.org/10.5282/edoc.27156Suche in Google Scholar

Keim, Inken. 1978. Gastarbeiterdeutsch: Untersuchungen zum sprachlichen Verhalten türkischer Gastarbeiter. Pilotstudie. Tübingen: Narr.Suche in Google Scholar

König, Katharina. 2014. Spracheinstellungen und Identitätskonstruktion. Eine gesprächsanalytische Untersuchung sprachbiographischer Interviews mit Deutsch-Vietnamesen. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1524/978311035224510.1524/9783110352245Suche in Google Scholar

König, Katharina. 2018. Ereignisse, Vorfälle und Wendepunkte – Erzählmuster bei der narrativen Rekonstruktion der Sprachbiographie migrationsbedingt mehrsprachiger SprecherInnen in Deutschland. In Brigitte Kreß, Vera da Silva & Irina Grigorieva (eds.), Mehrsprachigkeit, Sprachkontakt und Bildungsbiografie, 15–42. Frankfurt a. M.: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Landeshauptstadt München (eds.). 2020. Münchner Gesamtplan zur Integration von Flüchtlingen. https://www.muenchen.info/soz/pub/pdf/603_Gesamtplan_Integration.pdf (accessed 11 June 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Lüdi, Georges. 1996. Mehrsprachigkeit. In Hans Goebl, Peter H. Nelde, Zdeněk Starý & Wolfgang Wölck (eds.), Kontaktlinguistik/Contact Linguistics/Linguistique de contact. Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft, 233–256. Berlin: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Muysken, Pieter. 2000. Bilingual speech. A typology of code-mixing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Overstreet, Maryann. 2005. And stuff und so: Investigating pragmatic expressions in English and German. Journal of Pragmatics 37(11). 1845–1864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2005.02.01510.1016/j.pragma.2005.02.015Suche in Google Scholar

Pavlenko, Aneta. 2007. Autobiographic narratives as data in Applied Linguistics. Applied Linguistics 28. 163–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm00810.1093/applin/amm008Suche in Google Scholar

Poulisse, Nanda & Erik Schils. 1989. The influence of task- and proficiency-related factors on the use of compensatory strategies: A quantitative analysis. Language Learning 39(1). 15–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1989.tb00590.x10.1111/j.1467-1770.1989.tb00590.xSuche in Google Scholar

Riehl, Claudia. 2014. Mehrsprachigkeit. Eine Einführung. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.Suche in Google Scholar

Roll, Heike. 2003. Jugendliche Aussiedler sprechen über ihren Alltag: Rekonstruktion sprachlichen und kulturellen Wissens. München: Iudicum.Suche in Google Scholar

Thoma, Nadja. 2018. Sprachbiographien in der Migrationsgesellschaft. Eine rekonstruktive Studie zu Bildungsverläufen von Germanistikstudent*innen. Bielefeld: Transcript. https://doi.org/10.14361/978383944301910.1515/9783839443019Suche in Google Scholar

Wolf-Farré, Patrick. 2017. Sprache und Selbstverständnis der Deutschchilenen: Eine sprachbiographische Analyse. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter.10.33675/978-3-8253-7726-7Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.