Abstract

This article investigates the list of items of dress worn by the daughters Zion in Isa 3:18–23, as they are simultaneously stripped of them. It considers the poetic aspects of this list before turning to specific items, both jewelry and clothing, worn by the daughters in verses 18 and 22. These objects contribute to the complex characterization of the daughters Zion, as it poetically brings together a thick array of aesthetic, religious and traumatic meanings, and experiences.

[clothing] articles held closest to the skin, like vowel sounds, are usually not seen or heard alone [1].

In his 2008 piece proposing an intertextual reading of Isa 3:16–4:1 and Alexander Pope’s satire The Rape of the Lock, Miles rightly insists on the “piling up”[2] of rare items of dress in the poem of verses 18–23, as part of its poetics.[3] While many interpreters have assumed this list to be a token of the daughters’ vanity and frivolity,[4] we think this overload of textiles and adornments deserves serious exegetical scrutiny. In the midst of the growing scholarship on dress in the Hebrew Bible,[5] we propose to investigate the long list of textualized items of jewelry and dress in Isa 3:18–23, luxuries worn by the daughters Zion[6] before they are violently stripped by YHWH. We contend that the showcasing of such an abundance of adornments by the collective female character can be critically enlightened from both a religious and a gender studies perspective.

First, building on the study of ancient Levantine iconography, dress, as well as material culture theory,[7] we offer a translation of the multiple sets of jewelry, garments, and accessories mentioned in verses 18–23. The list involves an impressive array of hapax legomena and rare words, which makes the identification of some of the women’s attire particularly hard. Following Couey,[8] we take into consideration the literary nature of the poetic list in the above-mentioned verses to explore what kind of aesthetic evocations can be drawn from this catalogue of heavily clad women.

Second, taking the items of jewelry from verse 18 as well as the garments of verse 22 as our case studies, we examine the literary function of the adornments and how they contribute to the characterization of the daughters Zion, as well as their very specific type of embodiment. While concealing the daughters, this overload of fancy fabrics and trinkets also emphasizes the vulnerable bodies of its wearers. The beautifully ornate women, heavy with materiality, are stripped of everything (v. 17–18), in a clear case of divine sexual assault reducing them to a state of shame, distress, and defilement (v. 24). The proud “parading” of the women through the city alludes simultaneously to dire poverty and wealth. They are dressed both as war captives and elite priestly Judean – or Samarian – women, exhibiting their foreign and eccentric fashions.[9] The daughters disappear behind what is no more than a parade of precious spoils, in motion toward judgment and punishment, and rapidly becoming a vision of horror: women en route to deportation or exile. We contend that these amuletic and textile objects shape the metaphorical body of Daughters Zion to produce a very gendered and damaged representation of personified Jerusalem,[10] a dystopian vision in the shape of wounded, unsightly, and mourning women.

Translation of the list of items of dress found in Isaiah 3:18–23:

18. On this day, Adonai will remove their glory:

the anklets, the sun, and the moon pendants,

19. the drop pendants, the bracelets, and the veils,

20. the headdresses, the armlets, the ribbons,

the boxes of nèfèš [11] , the amulets,

21. the signet rings and the nose rings,

22. the cultic garments and the wraps,

the shawls, and the scarves.

23. the mirrors, the precious [linen] fabrics,

the turbans, and the stoles.

The constraints of this article make it impossible to explore every object listed.[12] Our focus on verses 18 and 22 gives us the opportunity to consider items of both jewelry and clothing. All adornments play a part in the “assembling” of the bodies of the daughters Zion, as well as their punitive and simultaneous “disassembling.”[13] The characters of the daughters can be understood as both noble Jerusalemite women and a collective personification of the city,[14] also being pillaged. Before turning to the two specific verses under study, we wish to offer a brief literary reassessment of the list found in verses 18–23. We contend that the literary device of “totalizing description,”[15] adapted to the peculiar case of this group of wealthy women in motion, can shed light on the poetic list, which confirms Liebermann’s idea of “dressed bodies as assemblages of inter-related things.”[16]

1 Making bodies with objects: A poetic list

Many scholars are quick to exclude verses 18–23 from any serious investigation for a few main reasons: the prose list is interpreted as a late interpolation interrupting the flow of the poetic passage and presenting no logical structure or order;[17] the numerous hapax legomena make the identification and translation process close to impossible; the list of dress items is far from the exegetical concerns of “established [male] scholars” of the prophetic books. Consequently, in main commentaries, the list is often dealt with rapidly and some translations testify to an unfortunate feminizing tendency of some of the items. For example, ḥărîtîm are often translated with the word “handbags” or “purses,”[18] and gilyonîm, is sometimes understood as “lingerie.”[19] These objects are overtly gendered and rejected as not worth the exegetical enquiry. To reverse this tendency, we would like to follow the lead of Kersken, Quick, and others and pay attention to this list.

While the Massoretic text (MT) does not offer as clear a coherence as the LXX version with its Alexandrine “dowry list,” clearly separating jewelry and clothes,[20] a similar – but more approximate – division of items is also discernible in the MT, the switch from jewelry to clothes happening in verse 22.[21] However, we should probably not separate the textile from the metal adornments too strictly. For example, the leḥāšîm of verse 20, most often understood as amulets, could have been made of any number of materials, including cloth.[22] We suggest reading this list as a series of “material peels” building the women from the inside out: from the direct touch of the jewelry in verses 18–21, with the anklets, pendants, bracelets, armlets, amulets, and so on, directly on the skin, to the thick layering of coats, wraps, and shawls in verses 22–23. We will come back to the meanings of these layers of objects worn as much as constituting the daughters Zion. As readers, we are invited to simultaneously imagine the women walking through/out of the city, weighed down by a princess’ entire wardrobe, as well as stripped and humiliated (v. 17, 24). In her work on cultural trauma and the book of Lamentations, Boase insists on the “somatic language” used to signify collective suffering.[23] In Isa 3:16–4:1, this idea also applies through the poetic (un)making of sartorial and bejeweled bodies.

Following Couey, we suggest that the list of verses 18–23 should also be appraised as poetry, just like the first verses of Isaiah 3.[24] As Couey contends in his dissertation on the book of Isaiah, “the use of lists in other Isaianic poems at least raises the possibility that these verses should be taken as poetry, and other considerations provide positive evidence of their poetic character.”[25] In a 1982 article, Jonathan Magonet also insists on the poetry of this list, which he identifies as a “sound poem.”[26] He mentions the rhymes created through the varying feminine and masculine plural endings of all objects,[27] as well as the chiasm of verses 20b–21, which includes two construct chains: boxes of nèfèš and nose rings.[28] He also brings to our attention the alphabetical order of the first letter of each of the three items of verse 20 (Peh, Tsaddeh, Qof). According to Magonet, these different patterns create “[…] an ornament in itself, a ‘necklace’ of sound […].”[29] While we agree with this author on the poetic character of these verses, we do not think that this poetic “shape” reflects the women’s sartorial foolishness in Isa 3:16–4:1. Rather, the poetic structure emphasizes even more the material expansiveness of the list, adding another noisy trinket – the poem itself – to the aesthetic display of the women.

When analyzing these verses, we also need to keep in mind that the poetic list is a well-known literary genre in the ancient Near East.[30] Isaiah 3:18–23 should be examined as a serious contender for this genre. Similarly, the literary device of “totalizing description” often used to showcase a beautiful and whole body (e.g., Song 4, 1–5) is worth considering when studying the list of Isa 3:18–23, especially since the word tif’èrèt “beauty, glory,” introduces the catalog in verse 18, and the word yōfî “beauty,” in verse 24, expands the list into the dire sartorial consequences. These “beauty words” actually frame a list that characterizes the daughters Zion as a beautiful “assemblage.” Following Deleuze and Guattari, by “assemblage” we mean “[…] precisely this increase in the dimensions of a multiplicity that necessarily changes in nature as it expands its connections.”[31] The collective “daughters” character can then be understood as a network made of body (and city?) parts, a lot of textiles and metals, an abusive YHWH, and so on. Beauty is far from being the only thing circulating through this multiplicity as it also entails flows of trauma, mourning, and much pain.

If we stay with the beauty aspect of the list/assemblage, we notice that it offers a peculiar take on the totalizing description and its usual “head-to-toe” orientation. First, while body parts are mentioned in verses 16 (throat, eyes, and feet) and 17 (crown and pudenda[32]), the beautiful bodies of the daughters Zion in verses 18–23 materialize and appear to the readers solely with the help of the adornments. Until verse 22, a lot of the items of dress seem to contribute to the framing of the face with the headdresses and veils in verses 19–20 on one hand, and the many pendants and amulets in verses 18 and 20 on the other. This corresponds well with the suggestion of art historian Amy Rebecca Gansell that “[wi]th regard to feminine beauty, biblical descriptions tend to focus on the head[33] […].” For example, the many necklaces, pendants, and amulets decorating the women possibly give shape to their throats. However, in the case of our list, other parts of the body are also implied. The mention of rings allows the readers to visualize fingers and noses (v. 21), while anklets and armlets bring feet and arms to mind (v. 18, 20). The women’s silhouettes are, in a way, made of metal and cloth. Second, while the totalizing description is usually expected to be the survey of one body,[34] the description of the daughters, a collective, implies multiple bodies and a certain material thickness. For example, the mostly textile list of verses 22 and 23 can be imagined as the apparel of several women as well as a very thick layering of clothing on one body, implying a rather horizontal appraisal of embodiment. Following the lead of Vayntrub in her study of Tyre in Ezek 27, the soon-to-be sunken ship,[35] with totalizing description, we favor a more expansive understanding of this literary device, beyond the “head-to-toe” verticality,[36] to include a “beauty through material objects” mode of depiction, which is immediately coming undone through divine violence with the use of the Hiphil of the verb sûr in v. 18: to take away, to strip. We will come back to this thickness of beauty, which paradoxically encodes the vulnerability of women’s bodies, in the last part of this article.

2 Anklets, suns, and moons: Fancy religious mnemonic trinkets (v. 18)

We now turn to the three items of jewelry found in Isa 3:18, to explore what is at stake in the undoing of beauty announced in that verse. The first objects mentioned are ‘ăkāsîm, the plural of ‘èkès, most probably “anklets.” This item is only found twice in the Hebrew Bible: Isa 3:18 and Prov 7:22.[37] This last occurrence is part of a simile that is most often judged as incomprehensible and is corrected in different ways with the idea of bonds and being bound and involves an animal-like young man.[38] The root-verb ‘ks is also used in verse 16 of the very same chapter of the book of Isaiah in the Piel, yiqtol, third feminine plural, suggesting that the daughters Zion are making a tinkling sound with their feet while walking. According to Kersken, this other verse (16) confirms the specific location of the ‘ăkāsîm on the bodies of the women: their feet.[39] In her book Töchter Zions, wie seid ihr gewandet?, Kersken also speculates that this type of anklets is made of ribbons (German: Band) and rows of beads, a type of jewelry found in ancient Egypt. Moreover, she argues that the two other items of verse 18, ševîsîm and sahărōnîm, are hanging from the anklets.[40] However, the archeological and iconographical evidence for southern Levant would rather favor imagining the daughters Zion wearing thick metal anklets on their heels, made of iron, bronze, or steel.[41] This type of adornment seemed to have been a “fashion staple” of Iron Age southern Levant, as indicated by the many anklets found in burials, most notably at Tell es-Sa’idiyeh (Jordan), including in women’s tombs[42] (see Annex 1 A). Some of these anklets, because of their thickness, could function as “[…] permanent or semi-permanent fixture,[43]” a new and lasting part of the body. Green and Golani both insist on interpreting these objects as heavy with meanings relating to pregnancy and motherhood.[44] In her study of children wearing metal bangles in the cemeteries of Tell el-Fa’rah, Braunstein also insists on the possible amuletic function of this jewelry to protect the well-being of children, as well as young women, especially during or after a pregnancy.[45] The protective function of these bangles is an intrinsic part of the religious experience of the “daughters” and should not be divorced from it. Contrary to some, we do not think it necessary to postulate an association with foreign cults and gods,[46] and we prefer to emphasize instead the “religious diversities”[47] of ancient Judah and Israel in which the anklets found their plural meanings. These worn objects could be understood as apotropaic[48] and participating in “[…] the memorialisation of religious traditions [that] would have been enacted in daily life,”[49] including in association with YHWH. They might signal personal beliefs and rituals, but also beauty, and gender status, as well as the lasting constrains imposed on the wearers’ bodies and motion.[50] Indeed, the intertext of Prov 7:22 reminds us that the heavy bangles of the daughters can easily become the fetters of captives.[51]

We now turn to the ševîsîm and sahărōnîm also mentioned in verse 18. While Roberts rightly states that the “Hebrew text does not make clear on which part of the body these ornaments [ševîsîm] were worn,”[52] the idea of pendants is presented convincingly by many scholars. We propose imagining these objects dangling from the women’s throats and/or clothes. Ševîsîm and sahărōnîm are mostly translated today by little suns and moons (see Annexes 1B and C). Indeed, as has been highlighted in recent scholarship regarding the hapax ševîsîm, the old hypothesis of the headbands has largely been abandoned in favor of “little suns.” This understanding of the word stems from its close relationship to the Ugaritic šepeš, which is cognate with the Hebrew šemeš [53] (sun). It is also worth noting that Šabisa/Sabis was the name of an Arabic deity.[54] The identification of the sahărōnîm is much easier since Sahar is the name of the moon god.[55] Moreover, both the Septuagint and the Vulgate seem to agree we are dealing with μηνίσκους or lunulas.[56] Little moons can also be found in Judg 8:21.26, as Gideon takes the crescents adorning the camels of the vanquished Midianite kings as spoils.[57] Williamson considers both to be foreign loan words.[58] According to Quick, “[…] sun or star pendants were used in Egyptian representations of Syro-Canaanites as an identifying cultural symbol.”[59] Many scholars contend that this jewelry involves foreign connotations. This includes Wildberger who argues that the collective character of the daughters Zion has no idea that their pendants are symbols of [other] divinities.[60] However, Limmer makes an excellent point in her dissertation, reminding us that “[…] a solar cult of YHWH appears to have been part of an indigenous tradition that was shared by national gods throughout the ancient Near East (Smith, Lipinski).”[61] Keel and Uehlinger, as well as Smith, have insisted on the association of solar and lunar iconographies with the God of Israel.[62] What could be at stake here is not so much idolatrous [non-Yahwistic] practices, but rather a case, as suggested by Quick, of “personal [amuletic] religion”[63] involving suns and moons as well as many other jewelry items from the list, like the boxes of nèfèš, the leḥāšîm,[64] and also, possibly, the anklets. With Smoak, we could suggest that the plethora of amulets worn by the daughters Zion are “presencing the Divine,”[65] but in an inappropriate manner. If we understand the moons and suns as decorating the “outstretched throats” of the women in verse 16, what we are dealing with here is not simply arrogance, pride, or frivolity,[66] but religious impropriety of upper-class Jerusalemite women from a prophetic point of view. Jeremiah 44 presents an interesting parallel. In Egypt, at the great displeasure of the prophet, the Judean women make offerings (cakes) and libations to the Queen of the skies (verses 16–19), possibly Asherah, YHWH’s consort. In Isa 3:16–24, as the women are violently divested from their items of jewelry, as well as sexually humiliated, reduced to a war captive-like state,[67] the objects seem to fail to fulfill their apotropaic function.[68] Moreover, in addition to their religious meaning, the discs and crescents can also function as archives of trauma. [69] These objects continually touch the body of the wearers and constitute haptic reminders of the daughters’ daily lives, including very disruptive and violent events such as military invasion, destruction of a city, captivity. While they disappear from the women’s bodies, their textual presence in Isaiah 3 encodes the memory of the violent (divinely approved) dispossession of the women and the city of Jerusalem both guilty, both assaulted.[70] The bits and pieces of the list participate in the making of “[…] a trauma narrative [which] is an act of meaning-making.”[71]

The imagined tinkling of jewelry bouncing on the bodies – necks, ankles, and wrists – already mentioned in verse 16, brings the focus on the motion of the women. They are walking and are apparently flaunting something visually unacceptable to YHWH and/or his prophet. While beauty words frame the poetic list in verses 18 and 23, a different kind of frame appears in verses 17 and 24: words of violence against the daughters Zion, including hurt and infection, sexual violence, baldness, minimal clothing associated with humiliation, and mourning. Such a “double framing” of beauty with violence engenders tensions in the interpretation of the passage. What can be read as the parading of beautifully adorned women, the material excess potentially hinting at parody, can also be understood as a procession of war captives as Assyria takes over Samaria or Babylonia, Jerusalem.[72] Multiple experiences could be at stake here. As Cynthia Chapman has suggested in her 2004 book: “[…] the biblical texts that are more historically removed from the Neo-Assyrian Period, we shall see that they tend to collapse the Assyrian experience into the Babylonian experience[73] […].” Again, Jeremiah (41:16; 43:6; 44:20) provides an interesting intertext: women take part in the fleeing operation to Egypt when Jerusalem falls. The Babylonian exile of royalty, including the king’s mother and wives in 2 Kings 24:15, also resonates quite well with Is 3,16–4,1, especially the list under study (v. 18–23). Destruction and exile may constitute the background of the women’s constricted movements, the strange parade being one way “trauma is imagined”[74] in the book of Isaiah. Following Markl, we could also understand the divine violence framing the list and falling upon the women as “an externalised act of self-blame,”[75] a way to work through one of the many traumatic experiences of ancient Israel/Judah, and the accompanying feelings of guilt and shame.[76]

To better investigate the war and exile-related experiences of “disaster”[77] we suspect are founding the list, we now explore verse 22 and its multiple garments or clothes.

3 Textile peels of exiled/captive women (v. 22)

With verse 22, the poetic list takes a textile turn filled with alliteration and assonance: hammaḥălāṣôt wehamma‘ătāfôt wehammitpāḥôt wehāḥărîtîm. While the exact nature of each item of dress might escape us, it will become clear that the four objects are usually worn in a “public” fashion and are visible to external observers as outer garments. This conclusion also applies to most items in verse 23. There is however a type of ambiguity at stake in Isa 3:22 as to the way these clothes are worn. As mentioned earlier, there is continual use of the plural (in the feminine and the masculine) for all objects listed. The literary device of “totalizing description” needs to be adapted horizontally to this troop of Jerusalemites who represent the city. Are we to imagine some daughters wearing maḥălāṣôt, others ma‘ătāfôt, mitpāḥôt, and ḥărîtîm? Or are we rather to understand the collective personification of Jerusalem as layering the items of clothing on their bodies? Could the literary totalizing be accomplished through the thickness in Isaiah 3:22? Before coming back to this idea, we consider each item of clothing.

Maḥălāṣôt seem to correspond to the fanciest item in the list. The only other occurrence in the Hebrew Bible, also in the plural, is found in Zechariah 3:4, where it designates the “clean” (possibly white) clothes that the high priest Joshua, dressed in dirty garments, is ordered to change into by the angel.[78] The idea of cleanliness – and possibly purity – is hinted at using the same root in cognate languages (Akkadian, Arabic). Since the first verb-root ḥālaṣ is thought to mean “to withdraw, to remove[79],” one of the main threads of interpretation has been to understand these as special garments to be removed for daily activities. The association of these clothes with the high priest[80] would suggest quality frocks. Kersken has opted for a “delicate” kind of clothing, made of flax or wool. However, the sole two occurrences in the Hebrew Bible make it difficult to formulate any assumption about the material used for these items.[81] Nevertheless, the pairing of the maḥălāṣôt in verse 4 with a turban (ṣānif) in verse 5,[82] also found in Isa 3:23, does confirm the luxury status of the garments. While Hallaschka rejects the idea of these clothes as priestly and Rees insists on the fact that kings wear them,[83] we would like to bring into focus that the root-verb ṣānaf [84] (to wrap) is also clearly associated with the priestly turban (miṣnèfèt) in Ex 28:4.37.39; 29:6; 39:28.31, etc. The idea of a cultic dimension to the garments would fit nicely with the amuletic frenzy of the daughters Zion, and the fact that another type of headdress, the pe’ērîm (v. 20), is found in both the daughters’ and the priestly wardrobe.[85] While most translate maḥălāṣôt as “festive/festal garments or robes,”[86] we would suggest translating it as “cultic robes or garments,” another opportunity to highlight the religious involvement of the daughters Zion, possibly severely frowned upon by the prophet and his God.

The following word, ma‘ătāfôt, is an hapax legomenon. The root-verb ‘ātaf, “to envelop, wrap oneself[87],” as well as the existence of the words ‘itaf as well as mitaf in Arabic or Middle Hebrew,[88] has brought most commentators to translate it as an outer-garment style of clothing, such as a mantle or coat.[89] While there is no way to evaluate the value of this textile item, we suggest that its wrapping function is the main thing at stake here, as it covers entirely the previous garment, as well as most of the jewelry mentioned in the previous verses. For this reason, we insist on translating it as “wraps.” While Williamson differentiates ma’atāfôt from mitpāḥôt, we contend that they could almost function as synonyms in verse 22.[90] The word mitpāḥôt is actually not found in the Isaiah scroll (1QIsa) of this text.[91] The only other occurrence also involves a woman, Ruth, in chapter 3, verse 15. This intertext gives us the opportunity to mention the multifunctional aspect of items of dress in the ancient Near East. Ruth uses this garment as a makeshift bag to carry the barley gifted to her by Bo’az after their intimate night. Once again, it is clearly an item of outerwear and the idea of a shawl, a translation offered by many scholars,[92] is very adequate. In the case of Isaiah 3:22, the “blanketing” function seems to be at stake again, especially if we visualize the garments as layers, superimposed on one another: cultic garments are covered by the wraps, and then the shawls.

The last items of verse 22, the ḥărîtîm, have been translated as bags, but also very often as “purses” and “handbags,” or even “wallets.”[93] As we mentioned earlier, this interpretative choice is clearly rooted in modern feminine stereotypes of women’s supposedly “futile” relationship to clothing[94] and – dare we say – shopping. In Second Kings 5:23, the only other occurrence of this word (also in the plural), the ḥărîtîm are “bound” to hold talents of silver and are part of a gift from Naaman, the general for the king of Aram, to Geḥazi, servant of the prophet Elisha. No one would ever contend that “handbags” are at the center of the two men’s exchange. Moreover, while Naaman’s wealthy[95] (royal) context could shed light on the well-to-do situation of the Jerusalemite women, the makeshift bag/shawl of Ruth carrying cereal, as well as Kersken’s hypothesis, points us in a different direction. Indeed, the practical use of the ḥărîtîm in 2 Kings 5:23 (among other reasons) leads Kersken to suggest that scarves, tied in different ways to carry items, could be at stake in Isa 3:22, highlighting the versatility of pieces of cloth in the ancient world.[96] This scarf/bag could then be imagined on top of all the previous layers of clothes (see Annex 1D). How are we, then, to understand the emphasis on this heap of clothes, a mix of utilitarian and fancy textiles?

Most recent scholarship on dress in the Hebrew Bible has insisted on clothing and jewelry as extensions or even double of the body. As suggested by Neville McFerrin in her work on the Apadana reliefs, “worn things become visual doubles for the people depicted wearing them.”[97] In the case of Isa 3:22, the list sculpts[98] a group of women out of their belongings, the very belongings that will be ripped from them to be replaced by stench, baldness, and sackcloth (v. 24). The Jerusalemite women’s bodies are radically transformed by experiences of war, captivity, and exile. We suggest that verse 22 already signals the pain and suffering about to be inflicted on the women/city through the thickness and weight of excessive outfits, which restrict their movements.[99] While she does not insist on items of dress as much as we do, Boase does highlight how Lam 1:1, with the lonely sitting of personified Jerusalem, brings the reader’s focus “[…] to the materiality of the body as a means of naming and expressing suffering.”[100] Isa 3:22 seems to affect our reading in the same way as we become hypnotized by the sartorial doubles of the women, reduced to the state of captives. The fashion parade reveals itself to be a slow and clumsy procession of prisoners or fugitives, heavy with materials that “[…] store former cultural inscriptions like palimpsests,”[101] religious as well as traumatic violent experiences.

4 Conclusion

Returning to the disc and crescent pendants, now wrapped in many layers of garments in verses 22 as well as 23 (for the most part), we must consider how the main three components of the collective body metaphor of Zion/Jerusalem, jewelry, fancy garments, and women, are also the very “objects” of plunder in the Hebrew Bible. The plundering of defeated (often young) women and their enslavement as part of the victors’ spoils is found in many passages of the Hebrew Bible.[102] For example, in Zech 14:1, the rape of women is mentioned in the context of the looting of Jerusalem. Rich fabrics and clothes are also often part of the war spoils besides precious metals like gold and silver, livestock, and sacred objects for worship.[103] In her work on classical Greek epics, Gaca observes that “[…] garments and ornaments are torn from captives, elegant dress and jewelry first.”[104] In the poetic list of Isa 3:18–23, everything is represented at once. The daughters Zion are now part of a walking plunder. Through their sartorial and adorned procession, they embody both the cause – religious impropriety – and the consequence – violent stripping and assault – of the divine judgment. Guilt and divine rage are fused in the same imagery, contributing to the cultural work of survival in the face of trauma.[105] However, other effects circulate throughout the list. The very assemblage of jewelry, garments, and bodies of the poetic list shapes the multiplicity that are the daughters Zion/Jerusalem, women and city, through disorienting flows of feelings: the enjoyment of beautification and religious agency, as well as the pain and suffering of assault and exile. Everything is happening all at once. And while the effects of this poetic segment on the readers are manifold, we would like to suggest, with Boase, that “[e]voking bodies connects us to other bodies,”[106] belonging to both ancient communities and contemporary readers, bringing embodiment to the forefront of interpretation.

While an investigation of all items of dress in Isa 3:18–23 is still necessary, we hope this article constitutes a first step in revealing how the poetic list functions as a prism for the many experiences of the collective character of the daughters and the city of Jerusalem in the book of Isaiah, as the grandeur, beauty, and popular religiosity of the women are conflated with mementos of imperial and exilic traumas.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a larger SSHRC-funded investigation on dress, violence, and gender in the Hebrew Bible. We thank Laura Kassar and Brandon Haskel-Martinez for their precious input in this piece, Fien De Doncker for her illustrations, Dr. Tim Lorndale for his thorough proofing, as well as the participants of the session “Israelite Prophetic Literature/Children in the Biblical World” at the 2021 SBL Annual Meeting for their comments and feedbacks. We also take this opportunity to thank the anonymous reviewers for their excellent suggestions and constructive criticism. Needless to say, any errors that remain are entirely our own.

-

Funding information: This research was financially supported by a SSHRC Insight Development Grant (430-2019-00304).

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

Appendix

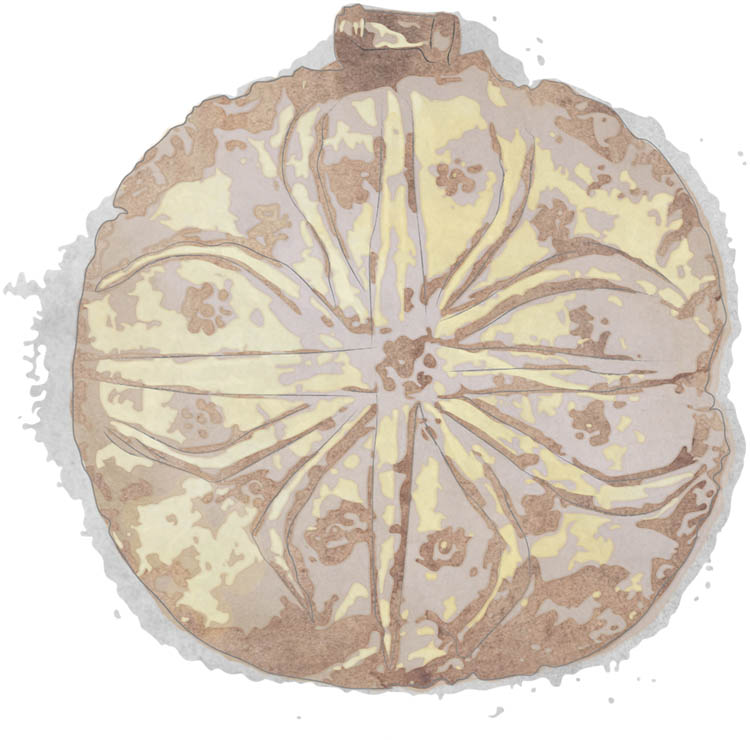

Annex 1

Drawings of ancient items of dress and adornment by artist Fien De Doncker

A. Anklets

Drawing done after the picture of Grave 411, Tell es-Sa’idiyeh.

Source: Josephine Verduci. “Adornment Practices in the ancient Near East and the Question of Embodied Boundary Maintenance.” In The Routledge Handbook of the Senses in the Ancient Near East, edited by Kiersten Neumann and Allison Thomason, 131. Abingdon: Routledge, 2022.

B. Sun Pendants

Drawing done after the picture of jewelry from the Uluburun Shipwreck, XIVth century BCE, Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology, Turkey.

Source: Cemal Pulak, “217a, b Pendants with Rayed Stars.” In Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade and Diplomacy in the Second Millenium B.C., edited by Joah Aruz, Kim Benzel and Jean Evans, 350–2. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

C. Dilbat necklace, suns and moons.

Drawing done after Old Babylonian Jewelry, ca. XVIIIth–XVIIth BCE.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Source: Kim Benzel, “Pendants and Beads.” In Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade and Diplomacy in the Second Millenium B.C., edited by Joah Aruz, Kim Benzel and Jean Evans, 24–5. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

D. Imagining Daughters Zion’s layers of clothing (Isa 3:22)

References

Bartelt, Andrew Hugh. The Book Around Immanuel: Style and Structure in Isaiah 2–12. Winona Lake IN: Eisenbrauns, 1996.Suche in Google Scholar

Benzel, Kim. “Pendants and Beads.” In Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade and Diplomacy in the Second Millenium B.C., edited by Joah Aruz, Kim Benzel and Jean Evans, 24–5. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

Berner, Christophe et al. (Eds.) Clothing and Nudity in the Hebrew Bible. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2019.10.5040/9780567678508Suche in Google Scholar

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. Isaiah 1–39: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, Anchor Bible 19. New York, NY: Doubleday, 2000.10.5040/9780300261301Suche in Google Scholar

Boase, Elizabeth. “The Traumatized Body: Communal Trauma and Somatization in Lamentation.” In Trauma and Traumatization in Individual and Collective Dimensions: Insights from Biblical Studies and Beyond, edited by Eve-Marie Becker, Jan Dochhorn, and Else Kragelund Holt, 193–209. Studia Aarhusiana Neotestamentica 2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2014.10.13109/9783666536168.193Suche in Google Scholar

Braunstein, Susan. “Children and Bangles in the Late Second-Millennium BCE Southern Levant.” In Assyromania and More: In Memory of Samuel M. Paley, edited by Friedhelm Pedde and Nathanael Shelley, 49–67. Münster: Zaphon, 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

Brown, Francis, Samuel R. Driver and Charles A. Briggs. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon: With an Appendix Containing the Biblical Aramaic. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

Chapman, Cynthia R. The Gendered Language of Warfare in the Israelite-Assyrian Encounter. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2004.10.1163/9789004370005Suche in Google Scholar

Couey, J. Blake. Reading the Poetry of First Isaiah: The Most Perfect Model of the Prophetic Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198743552.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Couey, J. Blake. “‘The Most Perfect Model of the Prophetic Poetry’: Studies in the Poetry of First Isaiah.” Ph.D. dissertation. Princeton Theological Seminary, 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Vol. 2. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

Finitsis, Antonios (Ed.). Dress and Clothing in the Hebrew Bible: For All Her Household Are Clothed in Crimson. London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2019.10.5040/9780567686428.ch-001Suche in Google Scholar

Finitsis, Antonios (Ed.). Dress Hermeneutics and the Hebrew Bible: « Let Your Garments Always Be Bright ». London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2022.10.5040/9780567702708Suche in Google Scholar

Fohrer, Georg. Das Buch Jesaja. Zürich-Stuttgart: Zwingli Verlag, 1966.Suche in Google Scholar

Frechette, Christopher G. and Elizabeth Boase. “Defining ‘Trauma’ as a Useful Lens for Biblical Interpretation.” In Bible Through the Lens of Trauma, edited by Elizabeth Boase and Christopher G. Frechette, 1–23. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2016.10.2307/j.ctt1h1htfd.4Suche in Google Scholar

Frenk, Joachim. Textualised Objects: Material Culture in Early Modern English Literature. Anglistische Forschungen, Band 429. Heidelberg: Universitätsverl. Winter, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

Gaca, Kathy L. “Reinterpreting the Homeric Simile of ‘Iliad’ 16.7–11: The Girl and Her Mother in Ancient Greek Warfare.” The American Journal of Philology 129, no. 2 (2008), 145–71.10.1353/ajp.0.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Gansell, Amy Rebecca. “The Iconography of Ideal Feminine Beauty Represented in the Hebrew Bible and Iron Age Levantine Ivory Sculpture.” In Image, Text, Exegesis: Iconographic Interpretation and the Hebrew Bible, edited by Isaak J. de Hulster and Joel M. Lemon, 46–70. London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

Golani, Amir. “Jewelry from the Iron Age II Levant.” PhD dissertation, University of Zurich, 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

Green, Jack. “Anklets and the Social Construction of Gender and Age in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Southern Levant.” In Archaeology and Women: Ancient and Modern Issues, edited by Sue Hamilton, Ruth D. Whitehouse & Katherine I, 283–311. Wright, Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

Hallaschka, Martin. “Clean Garments for Joshua. The Purification of the High Priest in Zech. 3.” In Clothing and Nudity in the Hebrew Bible, edited by Christopher Berner et al., 525–40. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2019.10.5040/9780567678508.ch-030Suche in Google Scholar

Hamilton, Ann. “Everyone” in Habitus. Philadelphia, PA: The Fabric Workshop and Museum (17 September 2016–8 January 2017).Suche in Google Scholar

Hays, Christopher. “Re-Excavating Shebna’s Tomb: A New Reading of Isa 22,15–19 in its Ancient Near Eastern Context.” Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 122 (2010), 558–75.10.1515/zaw.2010.039Suche in Google Scholar

Holt, Else K. “Daughter Zion: Trauma, Cultural Memory and Gender in OT Poetics.” In Trauma and Traumatization in Individual and Collective Dimensions: Insights from Biblical Studies and Beyond, edited by Eve-Marie Becker, Jan Dochhorn, and Else K. Holt, 16273. Studia Aarhusiana Neotestamentica 2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2014.10.13109/9783666536168.162Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, Ann Rosalind and Peter Stallybrass. Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.Suche in Google Scholar

Kersken, Sabine Aletta. Töchter Zions, Wie Seid Ihr Gewandet?: Untersuchungen zu Kleidung und Schmuck alttestamentlicher Frauen. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

Kotrosits, Maia. The Lives of Objects: Material Culture, Experience, and the Real in the History of Early Christianity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2020.10.7208/chicago/9780226707617.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Létourneau, Anne. “Tisser Pour Ashérah. La Participation Textile des Femmes au Culte en 2 R 23,7.” Mélanges de Sciences Religieuses, 78, no. 5 (2022), 60–71.Suche in Google Scholar

Létourneau, Anne. “From Wild Beast to Huntress: Animal Imagery, Beauty, and Seduction in the Song of Songs and Proverbs.” Biblical Interpretation (published online ahead of print, 2021).10.1163/15685152-20211613Suche in Google Scholar

Levitt, Laura. The Objects that Remain. State College, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020.10.1515/9780271088792Suche in Google Scholar

Liebermann, Rosanne. “Clothing and Body Modification in the Hebrew Bible.” Religion Compass 15, no. 3 (2021).10.1111/rec3.12389Suche in Google Scholar

Limmer, Abigail Susan. “The Social Functions and Ritual Significance of Jewelry in the Iron Age II Southern Levant.” PhD dissertation. The University of Arizona, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

Luckenbill, Daniel David. “The Oriental Institute Prism Inscription.” In The Annals of Sennacherib, 23–47. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1924.Suche in Google Scholar

Magonet, Jonathan. “Isaiah 2:1–4:6, Some Poetic Structures and Tactics.” Amsterdamse Cahiers 3 (1982), 71–85.Suche in Google Scholar

Markl, Dominik. “Cultural Trauma and the Song of Moses (Deut 32).” Old Testament Essays 33, no. 3 (2020), 674–89.10.17159/2312-3621/2020/v33n3a18Suche in Google Scholar

McFerrin, Neville. “Fabrics of Inclusion: deep wearing and the potentials of materiality on the Apadana reliefs.” In What Shall I Say of Clothes? Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to the Study of Dress in Antiquity, edited by Megan Cifarelli et Laura Gawlinski, 143–59. Boston, MA: Archaeological Institute of America. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

Miles, J. “Re-reading the Power of Satire: Isaiah’s ̔ Daughters of Zion’, Pope’s ̔ Belinda’, and the Rhetoric of Rape.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 31, no. 2 (2006), 193–219.10.1177/0309089206073099Suche in Google Scholar

Platt, Elizabeth E. “Jewelry of Bible Times and the Catalog of Isa 3:18–23. Part 1.” Andrews University Seminary Studies, 17 no. 1 (1979), 71–84.Suche in Google Scholar

Pulak, Cemal. “217a, b Pendants with Rayed Stars.” In Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade and Diplomacy in the Second Millenium B.C., edited by Joah Aruz, Kim Benzel and Jean Evans, 350–2. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

Quick, Laura Elizabeth. Dress, Adornment and the Body in the Hebrew Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.10.1093/oso/9780198856818.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Rees, Susannah. “‘Women Rule over Them’: Dressing for an Inverted World in Isaiah 3.” In Dress Hermeneutics and the Hebrew Bible: ‘Let Your Garments Always Be Bright’, edited by Antonios Finitsis, 165–86. London: T & T Clark/Bloomsbury, 2022.10.5040/9780567702708.ch-008Suche in Google Scholar

Roberts, J. J. M. “First Isaiah: A Commentary.” Hermeneia – A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible, edited by Peter Machinist. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2015.10.2307/j.ctvgs0919Suche in Google Scholar

Sauvage, Caroline. “Senses and Textiles in the Eastern Mediterranean. Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages (1550–1100 BCE).” In The Routledge Handbook of the Senses in the Ancient Near East, edited by K. Neumann and A. Thomason, 35–61. New York, NY: Routledge, 2021.10.4324/9780429280207-4Suche in Google Scholar

Smoak, Jeremy D. “Wearing dIvine Words: In Life and Death.” Material Religion 15, no. 4 (2019), 433–55.10.1080/17432200.2019.1631695Suche in Google Scholar

Stavrakopoulou, Francesca. “‘Popular’ Religion and ‘Official’ Religion: Practice, Perception, Portrayal.” In Religious Diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah, edited by Francesca Stavrakopoulou & John Barton, 37–56. London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

Sweeney, Marvin. Isaiah 1–4 and the Post-Exilic Understanding of the Isaianic Tradition. New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter, 1988.10.1515/9783110854565Suche in Google Scholar

Van der Meer, Michaël N. “Trendy Translations in the Septuagint of Isaiah. A Study of the Vocabulary of the Greek Isaiah 3,18–23 in the Light of Contemporary Sources.” In Die Septuaginta – Texte, Kontexte, Lebenswelten. Internationale Fachtagung veranstaltet von Septuagint Deutsch (LXX.D) Wuppertal 20–23. Juli 2006, edited by Martin Karrer and Wolfgang Kraus, 581–96. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.Suche in Google Scholar

Vayntrub, Jacqueline. “Beauty, Wisdom, and Handiwork in Proverbs 31: 10–31.” Harvard Theological Review 113, no 1 (2020), 45–62.10.1017/S0017816019000348Suche in Google Scholar

Vayntrub, Jacqueline. “Tyre’s Glory and Demise: Totalizing Description in Ezekiel 27.” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 82, no 2 (2020), 214–36.10.1353/cbq.2020.0083Suche in Google Scholar

Verduci, Josephine. “Adornment Practices in the Ancient Near East and the Question of Embodied Boundary Maintenance.” In The Routledge Handbook of the Senses in the Ancient Near East, edited by Kiersten Neumann and Allison Thomason, 127–140. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2022.10.4324/9780429280207-9Suche in Google Scholar

Watson, Wilfred G. E. Classical Hebrew Poetry: A Guide to Its Techniques. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series, 26. Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1986.Suche in Google Scholar

Watts, John D. W. Isaiah. 1–33. Waco: Word Books Publisher, 1985.Suche in Google Scholar

Wildberger, Hans. Isaiah 1–12: A Commentary. A Continental Commentaries. Minneapolis (Minn.): Fortress Press, 1991.Suche in Google Scholar

Williamson, H. G. M. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Isaiah 1–27. The International Critical Commentary. London: T & T Clark, 2006.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Anne Létourneau et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Topical issue: After the Theological Turn: Essays in (New) Continental Philosophical Theology, edited by Martin Koci

- After the Theological Turn? Editorial Introduction

- It Takes Two to Make a Thing Go Right: Phenomenology, Theology, and Janicaud

- Ending Christian Hegemony: Jean-Luc Nancy and the Ends of Eurocentric Thought

- God Who Comes to Mind: Emmanuel Levinas as Inspiration and Challenge for Theological Thinking

- Confessional Discourses, Radicalizing Traditions: On John Caputo and the Theological Turn

- After the Theological Turn: Towards a Credible Theological Grammar

- Towards a Phenomenology of Kenosis: Thinking after the Theological Turn

- Revelation and Philosophy in the Thought of Eric Voegelin

- Is Finitude Original? A Rereading of “Violence and Metaphysics”

- Thinking with Faith, Thinking as Faith: What Comes After Onto-theo-logy?

- Outside Phenomenology?

- Topical issue: Cultural Trauma and the Hebrew Bible, edited by Danilo Verde and Dominik Markl

- Triumph and Trauma: Justifications of Mass Violence in Deuteronomistic Historiography

- The Fall of Jerusalem: Cultural Trauma as a Process

- From Healing to Wounding: The Psalms of Communal Lament and the Shaping of Yehud’s Cultural Trauma

- Trauma in the Apocryphon of Jeremiah C: Cultural Trauma as Forgetful Remembrance of Divine-Human Relations in Qumran Jeremianic Traditions

- Ezekiel and the Construction of Cultural Trauma

- Micah 1–3 and Cultural Trauma Theory: An Exploration

- Topical issue: Death and Religion, edited by Khyati Tripathi and Peter G.A. Versteeg

- Rethinking Death’s Sacredness: From Heraclitus’s frag. DK B62 to Robert Gardner’s Dead Birds

- God and the Goodness of Death: A Theological Minority Report

- Death from the Perspective of Luhmann’s System Theory

- The Dragon on the Path and the Emerald of Love: A Nietzschean reading of Rūmī’s concept of love

- Remember Death: An Examination of Death, Mourning, and Death Anxiety Within Islam

- Exploring the “Liminal” and “Sacred” Associated with Death in Hinduism through the Hindu Brahminic Death Rituals

- Contesting Deaths’ Despair: Local Public Religion, Radical Welcome and Community Health in the Overdose Crisis, Massachusetts, USA

- Regular Articles

- Beyond Metaphor: The Trinitarian Perichōrēsis and Dance

- Fetish Again? Southern Perspectives on the Material Approach to the Study of Religion

- From Persuasion to Acceptance of Closeness: La Projimidad as an Essential Attribute of God in Luke 10:25–37

- The Christological Perichōrēsis and Dance

- Process-Panentheism and the “Only Way” Argument

- A Pragmatic Piety: Experience, Uncertainty, and Action in Charles G. Finney’s Evangelical Revivalism

- Good Life, Brave Death, and Earned Immortality: Features of a Neglected Ancient Virtue Discourse

- A Historical-Contextualist Approach to the Joseph Chapter of the Qur’an

- Contemporary Visions of Heaven and Hell by a Transylvanian Folk Prophet, Founder of the Charismatic Christian Movement The Lights

- Evangelical Historiography in the Colonial and Postcolonial Eras

- A Parade of Adornments (Isa 3:18–23): Daughters Zion in the Light of Gender and Material Culture Studies

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Topical issue: After the Theological Turn: Essays in (New) Continental Philosophical Theology, edited by Martin Koci

- After the Theological Turn? Editorial Introduction

- It Takes Two to Make a Thing Go Right: Phenomenology, Theology, and Janicaud

- Ending Christian Hegemony: Jean-Luc Nancy and the Ends of Eurocentric Thought

- God Who Comes to Mind: Emmanuel Levinas as Inspiration and Challenge for Theological Thinking

- Confessional Discourses, Radicalizing Traditions: On John Caputo and the Theological Turn

- After the Theological Turn: Towards a Credible Theological Grammar

- Towards a Phenomenology of Kenosis: Thinking after the Theological Turn

- Revelation and Philosophy in the Thought of Eric Voegelin

- Is Finitude Original? A Rereading of “Violence and Metaphysics”

- Thinking with Faith, Thinking as Faith: What Comes After Onto-theo-logy?

- Outside Phenomenology?

- Topical issue: Cultural Trauma and the Hebrew Bible, edited by Danilo Verde and Dominik Markl

- Triumph and Trauma: Justifications of Mass Violence in Deuteronomistic Historiography

- The Fall of Jerusalem: Cultural Trauma as a Process

- From Healing to Wounding: The Psalms of Communal Lament and the Shaping of Yehud’s Cultural Trauma

- Trauma in the Apocryphon of Jeremiah C: Cultural Trauma as Forgetful Remembrance of Divine-Human Relations in Qumran Jeremianic Traditions

- Ezekiel and the Construction of Cultural Trauma

- Micah 1–3 and Cultural Trauma Theory: An Exploration

- Topical issue: Death and Religion, edited by Khyati Tripathi and Peter G.A. Versteeg

- Rethinking Death’s Sacredness: From Heraclitus’s frag. DK B62 to Robert Gardner’s Dead Birds

- God and the Goodness of Death: A Theological Minority Report

- Death from the Perspective of Luhmann’s System Theory

- The Dragon on the Path and the Emerald of Love: A Nietzschean reading of Rūmī’s concept of love

- Remember Death: An Examination of Death, Mourning, and Death Anxiety Within Islam

- Exploring the “Liminal” and “Sacred” Associated with Death in Hinduism through the Hindu Brahminic Death Rituals

- Contesting Deaths’ Despair: Local Public Religion, Radical Welcome and Community Health in the Overdose Crisis, Massachusetts, USA

- Regular Articles

- Beyond Metaphor: The Trinitarian Perichōrēsis and Dance

- Fetish Again? Southern Perspectives on the Material Approach to the Study of Religion

- From Persuasion to Acceptance of Closeness: La Projimidad as an Essential Attribute of God in Luke 10:25–37

- The Christological Perichōrēsis and Dance

- Process-Panentheism and the “Only Way” Argument

- A Pragmatic Piety: Experience, Uncertainty, and Action in Charles G. Finney’s Evangelical Revivalism

- Good Life, Brave Death, and Earned Immortality: Features of a Neglected Ancient Virtue Discourse

- A Historical-Contextualist Approach to the Joseph Chapter of the Qur’an

- Contemporary Visions of Heaven and Hell by a Transylvanian Folk Prophet, Founder of the Charismatic Christian Movement The Lights

- Evangelical Historiography in the Colonial and Postcolonial Eras

- A Parade of Adornments (Isa 3:18–23): Daughters Zion in the Light of Gender and Material Culture Studies