Abstract

Phototherapy attracts increasing interest for broad bio-applications due to its noninvasive and highly selective nature. Owing to their good biocompatibility, unique optoelectronic properties and size/surface effects, carbon nanomaterials show great promise for phototherapy. Various carbon nanomaterials have been demonstrated as efficient phototherapy agents for a large variety of phototherapeutic applications, including cancer treatment, anti-bacteria, and Alzheimer’s disease. This review summarizes the recent progress of carbon nanomaterials for phototherapy. Current challenges and future perspectives are also discussed.

1 Introduction

Phototherapy, as minimally invasive therapy, is widely applied for cancer therapy, anti-bacterial/inflammation, and other biomedical applications [1–3]. Compared to chemotherapy or radiotherapy, phototherapy exhibits an extra level of selectivity by focusing light beams on the targeted region to minimize side effects [4–6]. A typical phototherapeutic process involves light sources and phototherapeutic agents (PAs) that can convert light into thermal energy (photothermal therapy, PTT) or chemical energy (photodynamic therapy, PDT). Among the light sources typically used for phototherapy, UV–vis light (200–700 nm) has relatively high energy but limited penetration depth while near-infrared (NIR) light (800–1200 nm) with an approximate penetration depth of 20–30 mm has relatively low energy. NIR light is generally considered a promising excitation source for deep-tissue applications (e.g., deep-seated tumours) [4].

Photothermal therapy (PTT) converts the light into heat to induce localized hyperthermia (>39 °C) for ablating the targeted area (e.g., tumour [5–7], bacteria [8–10] through the destruction of cells (e.g., protein denature at 39 °C). However, light-induced hyperthermia often requires a high-power intensity, leading to potential damage to non-target cells [11]. In the process of photodynamic therapy (PDT), the photodynamical agents or photosensitizers [12] (PS) absorb the light of a particular wavelength and transfer the photo energy to surrounding molecules to produce highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) [13], as schematically shown in Figure 1 [14]. Therefore, based on the specific energy transfer process involved, PDT can be further divided into type I, electron or hydrogen transfer to produce radicals (e.g., ·OH, O2 ·−) [15]; and type II, energy transfer to produce singlet oxygen [12, 16]. For tumour therapy, type I attracts more and more attention because of its low oxygen dependency and the hypoxia characteristic in the tumour microenvironment (TME) [12].

![Figure 1:

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) mechanism [14]. Copyright 2022 Elsevier publishing group.](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0574/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0574_fig_001.jpg)

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) mechanism [14]. Copyright 2022 Elsevier publishing group.

Although considerable progress in phototherapy has been made recently [17], current phototherapeutic treatments suffer several drawbacks, including high laser intensity, potential skin damage, limited penetration depth, and poor targeting [18–20]. PDT for cancer treatment is further limited by the fact that the hypoxia characteristic in the TME [13] promotes tumour growth, abnormal tumour vasculature, and metastasis with resistance to O2 dependence treatments [4, 21, 22] and that PDT agents generally respond to UV-visible lights, which has the poor tissue penetration and a high potential for normal tissue damage due to the relatively high light energy.

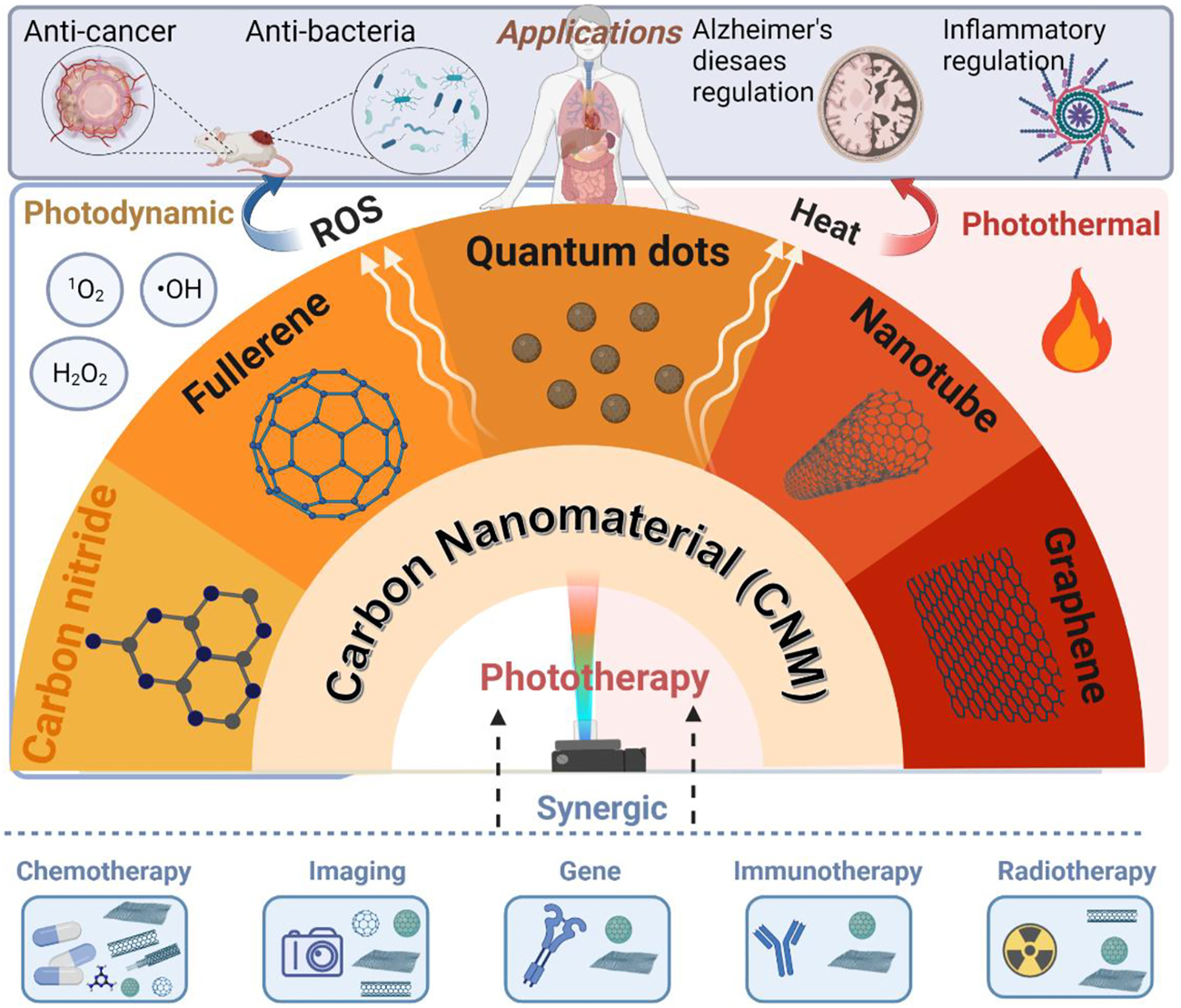

Currently-used phototherapeutic agents (PAs) include organic molecules, noble metal oxides, and semiconducting nanoparticles [23, 24]. Organic PAs, such as chlorin e6 (Ce6) and methylene blue (MB), have limited water solubility and photostability, while metal or semiconductor oxides suffer from poor biocompatibility and are hard to be cleared through the renal system, leading to the risk for visceral deposition of heavy metal elements [25]. To overcome these obstacles [26], carbon nanomaterials (CNMs) with their good biocompatibility [27], deep tissue diffusibility [28] and strong optical absorption characteristics [29] have been demonstrated to be desirable for various phototherapeutic applications. Figure 2 summarizes the use of CNMs as PAs for phototherapy.

Summary of carbon nanomaterials (CNMs) for phototherapy, created with BioRender.

2 Carbon-based materials for phototherapy

Carbon is the fourth most abundant element in the Universe and Earth-abundant [30]. Carbon can also be found in all types of life. Historically, carbon materials were known to exist only in three forms: amorphous carbon, graphite, and diamond. In the last several decades, carbon research attracted two Nobel Prizes to recognize the discoveries of C60 and graphene, along with a Kavli Prize for the discovery of carbon nanotube [30, 31]. It was demonstrated that carbon materials can have remarkably different properties depending on how the carbon atoms are arranged and what are their molecular dimensions/shapes [32]. Therefore, carbon can provide enormous opportunities for developing new materials with novel properties for various applications. Owing to their unique physicochemical properties, good biocompatibility, large surface area, easy surface modification, earth-abundant and low-cost, carbon materials have attracted a great deal of interest for a wide range of potential applications [33, 34] including biomedical applications for drug delivery [35], tissue engineering [36], cancer diagnosis and therapy [37, 38], bio-sensors [36, 39, 40], Alzheimer’s disease [19, 41], biomedical imaging [42] and anti-bacteria [43].

Although a majority of pure carbon materials are inactive as phototherapy agents, several surface functionalization strategies have been developed to assist CNM PAs to show good performance in phototherapy [44]. The design of carbon-based materials as phototherapy agents can be divided into the following three categories:

Targeting: e.g., improving tumour specificity and recognizing any remaining tumour cells at the site of distant metastases through modification with:

In addition, some more specific modification methods have also been reported, for instance, to enhance the half-life of blood circulation [44] or anti-hypoxia for cancer treatment [52]. Furthermore, more than one modification methods are often applied simultaneously for optimal phototherapy effects [53].

2.1 Carbon nanotubes (CNTs)

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are one or more graphite sheets that are rolled up into tube forms to form single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) or multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs) [54]. SWCNTs are the first CNMs used in phototherapy [55]. Owing to their excellent absorption characteristics and photothermal conversion efficiencies in NIR-I (700–950 nm) and NIR-II (1000–1700 nm) regions [56], CNTs are often used for PTT.

Panchapakesan et al. [55] employed SWCNT as photothermal therapeutic agents and reported their inhibition capacity for breast cancer BT474 cell line in response to 800 nm laser (approx. 50–200 mW/cm2) [55]. In 2012, the intrinsic fluorescence of SWCNTs over the NIR-II region was utilized for in vivo imaging [57]. Later, SWCNTs were employed as in vitro PDT agents in 2014 [58]. Apart from SWCNTs, MWCNTs have also been used as in vitro PTT agents since 2009 [59]. However, the poor solubility, polydispersity and non-selective performance of CNTs in addition to biosafety concerns limited their practical applications [45, 60]. Therefore, several modification methods have been developed for CNTs. At the early stage, cancer-targeting molecules such as antibodies or specific receptors were combined with CNTs for in vitro cancer cell inhibition. For example, in 2007, Shao et al. [61] modified SWCNT with an IGF1 receptor and HER2 to achieve the selective attachment of the modified SWCNT to breast cancer cells. After 3 min exposure to 808 nm light (∼800 mW/cm2), the modified SWCNT demonstrated complete inhibition of cancer cells in vitro whereas the non-modified SWCNT showed only 20% inhabitation on MCF-7. In 2008, Chakravarty et al. [62] coupled SWCNTs with anti-CD25 mAb for phototherapy of PTT tumour cells in vitro with NIR light (808 nm, 5 W/cm2, 7 min). Wang et al. [59] reported in 2009 that MWCNTs conjugated with anti-GD2 were selectively internalized by neuroblastoma cells via GD2-mediated endocytosis but not PC12 cells with a poor GD2 expression. For neuroblastoma cells, cell death was only found within the NIR espoused region (808 nm, 0.6–6 W/cm2 10 min + 6 W/cm2 5 min) [59].

Hydrophobic compounds tend to have low bioavailability and have a tendency to be eliminated from the gastrointestinal tract [63]. The hydrophobic nucleobases of DNA could bind to CNT through hydrophobic-hydrophobic interaction and/or π–π stacking while the phosphodiester backbone of DNA can enhance the hydrophilicity of the DNA-attached CNTs (Figure 3a) [45, 64, 65]. Ghosh et al. reported the first intratumoural injection of DNA-attached MWCNTs as PTT agents to completely eliminate tumours in the PC3 tumour xenograft mouse model in response to NIR-II light (1064 nm, 2.5 W/cm2) (Figure 3b) [64]. Compared to the pristine MWCNTs, the DNA attachment increased the PTT heat production up to 2–3 times. MWCNTs have also been reported for chem-phototherapy by loading DOX, ICG and CD44 receptors for targeting hyaluronic acid (HA) [66]. However, it is still challenging for CNTs to reach the target area after intravenous injection. As demonstrated by intravenous and intratumoural injection mimicked models, intratumoural injection of PAs could achieve better results (100% inhibition of cancer cells) compared to intravenous injection of PAs (60% inhibition of cancer cells) [67]. However, intratumoural injection is facing the challenge of locating the tumour at the early stage and reaching the tumour site in the deep region. Nevertheless, several CNMs have been reported to be able to accumulate in the tumour tissues with/without targeting modification [25, 68], [69], [70].

![Figure 3:

CNT as phototherapy agents: (a) DNA-assisted dispersion of CNTs [45], Copyright 2022 Nature Publishing Group. (b) DNA-attached MWCNTs for PTT [64], Copyright 2022 ACS AuthorChoice. (c) PEG-SWCNTs for NIR PTT [44], Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. (d) immune responses triggered by anti-CTLA-4 SWCNT [71], Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons. (e) image guide-SWCNTs for PTT [72], Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons. (f) RIT&PTT by SWCNTs [73], Copyright 2022 Ivyspring International Publisher.](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0574/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0574_fig_003.jpg)

CNT as phototherapy agents: (a) DNA-assisted dispersion of CNTs [45], Copyright 2022 Nature Publishing Group. (b) DNA-attached MWCNTs for PTT [64], Copyright 2022 ACS AuthorChoice. (c) PEG-SWCNTs for NIR PTT [44], Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. (d) immune responses triggered by anti-CTLA-4 SWCNT [71], Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons. (e) image guide-SWCNTs for PTT [72], Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons. (f) RIT&PTT by SWCNTs [73], Copyright 2022 Ivyspring International Publisher.

PEGylation is commonly used to improve the solubility of nanoparticles and extend their half-life circulation times in bloodstream. In 2009, Moon et al. [44] reported PEGylated-SWCNTs for NIR PTT (808 nm, 76 W/cm2, 3 min) (Figure 3c). They found that PEGylated-SWCNTs could destroy tumour cells through partial skin damage in a noninvasive manner. It was revealed that there was no harmful side effect or tumour recurrence even after prolonged photothermal treatment for over 6 months [44]. Subsequently, Dai and coworkers [74] demonstrated the PEGylated SWCNTs for NIR light-induced (808 nm) PTT at a very low injection dose (70 μg of SWNT/mouse, 3.6 mg/kg, equivalent to 3.6 mg/kg) with a low laser irradiation power (0.6 W/cm2). After intravenous injection, PEG-SWCNTs showed a high elimination effect on tumours and their uptake could be imaged via the intrinsic NIR-photoluminescence (PL) from SWCNTs [74]. Liu and coworkers [71] reported that the combination of SWCNT with PEG and anti-CTLA-4 antibody for triggering an immunological response (Figure 3d) can not only photothermally ablate primary tumours but also significantly reduce the development of tumour metastasis in comparison to surgery (Figure 3d, the average number of metastasis sites of surgery: ∼30 per mouse, SWNT-based PTT plus anti-CTLA4 therapy: ∼1 per mouse). Apart from the excellent photothermal performance, CNTs can also act as PDT agents. In 2014, Zhou et al. [75] reported SWCNTs for photodynamic therapy by functionalizing SWCNTs with PL-PEG, which could be found in mitochondria in both normal and cancer cells or lysosomes macrophages depending on internalized methods, mitochondrial transmembrane and/or endocytosed. By further modifying SWCNT-PL-PEG with folate acid (FA), FA-SWCNTs could selectively enter the FR-positive cells to produce significant ROS under 980 nm laser(0.75 W/cm2, 2 min), inducing mitochondrial damage and consequent apoptosis [75]. The first SWCNT-based in vivo PDT study was reported by Wang et al. in 2014 using visible light (300 W lamp at 20 cm distance for 1 or 2 h). In this case, SWCNTs were covalently functionalized with PEI to demonstrate a promising anti-cancer effect via PDT in vitro and in vivo [58].

SWCNTs have also been applied to synergistic therapies, including PTT-CT (DOX [76], SNX-2122 [77]), imaging-guided PTT [72], PTT enhanced PDT [78] and PTT-RIT [73]. It has been reported that many aromatic drugs (e.g., DOX) could be loaded on CNTs via hydrophobic interaction and/or π–π stacking [76] to improve cellular uptake of the nano-carriers and for a more controllable drug release. In this context, Liu and coworkers synthesized PEG-modified mesoporous silica (MS) coated SWCNTs for cancer therapy with a synergistic effect by photothermally releasing anti-cancer drug DOX with NIR stimulation, leading to an outstanding synergistic tumour suppression at a low SWNT@MS-PEG dose (10 mg/kg and 4.3 mg/kg) and low laser power density (808 nm, 0.7 W/cm2, 5 min) [79]. In 2014, Liang et al. further reported the image-guided PTT for the effective destruction of primary tumours and cancer cells in sentinel lymph nodes, leading to a significant improvement in survival rate and metastasis inhibition (Figure 3e) [72]. In another study, Liu and coworkers combined PEG-SWNTs with a self-polymerized PDA shell, which could chelate Mn2+ for MRI imaging and enable efficient radioisotope labeling with 131I to allow for radioisotope therapy (RIT) to be combined with PTT (Figure 3f) [73].

To make multifunctional CNTs, they have been conjugated with multiple surface modifiers as imaging-guided triple-modal therapeutic (PTT/PDT/CT) agents for cancer treatments under 808 nm irradiation [80]. In this regard, Liang et al. modified CNTs with PDA and dopamine coating to achieve good solubility in water and low cytotoxicity. Certain CNT composites also showed excellent potential for bacteria-infected skin wound healing [81]. In summary, CNTs with strong NIR absorbance and high surface modification potential have been widely used in photothermal therapy and are exploited for photodynamic and other treatments recently. Furthermore, CNT-based multifunctional nanocomposites have been used for improved anticancer treatments with multiple synergistic therapeutic effects. Although research progresses achieved to date have demonstrated no in vivo adverse effects even over 6 months after PTT [44], the potential long-term cytotoxicity still requires further study [60].

2.2 Graphene and related materials

Graphene oxides (GO) have been used for photothermal therapy [43, 82–84]. The poor water solubility of graphene-based materials has limited their applications for phototherapy, though they have excellent NIR absorption. Nevertheless, good water solubility and stability have been achieved by conjugating with hydrophilic polymers, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), via the surface carboxyl groups of GO [85, 86]. Having the graphitic sp2 arrangement, GO can also be functionalized through π–π stacking. Using both covalent and noncovalent bonding strategies [28] various aromatic drugs, including DOX [67, 87], SN38 [82] and camptothecin (CPT) [83], have been successfully attached to GO.

In 2010, Liu and coworkers used PEGylated nanographene oxides (nGO) as an in vivo PTT reagent for 4T1 tumour-bearing mice in response to 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2, 5 min) [84]. It was found that PEG-nGO (GO dose: 200 μL, 2 mg/mL) showed high passive accumulation due to the enhanced permeability and retention in tumours and that the surface temperature could reach up to 50 °C upon irradiation versus only around 2 °C increase for mice without the injection of PEG-nGO. All tumours of the mice treated with PEG-nGO disappeared within 1 day after irradiation with no tumour regrowth over 40 days (Figure 4a).

![Figure 4:

Graphene-based material for phototherapy: (a) PEG-nGO for PTT [84], Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society (b) rGO for PTT at low laser power [88], Copyright 2022 Elsevier publishing group. (c) PTT and CT ynergistic GO [67], Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons. (d) PTT&PDT GO for anti-bacterial [86], Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0574/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0574_fig_004.jpg)

Graphene-based material for phototherapy: (a) PEG-nGO for PTT [84], Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society (b) rGO for PTT at low laser power [88], Copyright 2022 Elsevier publishing group. (c) PTT and CT ynergistic GO [67], Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons. (d) PTT&PDT GO for anti-bacterial [86], Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

GO, in a highly oxidized form, may have insufficient NIR absorption, leading to a low PTT conversion efficiency [89]. In 2011, Dai and coworkers proposed that reduced graphene oxides (rGO) could be a better candidate for PTT at a low dose and power intensity [89]. They proved that PEG-nano-rGO further modified with the peptide RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) has a highly selective cellular uptake for effective photothermal inhabitation of U87MG cancer cells in vitro [89]. In 2012, Liu and coworkers reported that PEG-functionalized rGO could achieve excellent tumour elimination through intravenous injection upon exposure to ultra-low power intensity (0.15 W/cm2) 808 nm laser for only 5 min [88]. The long-term post-treatment effects were tracked for 100 days with no obvious side effects or death (Figure 4b). These results demonstrate a promising future for graphene-based PTT therapeutic approaches against cancer even at power intensity lower than that required by clinic regulation to avoid skin damage (0.38 W/cm2). While PEG-GO was mainly found in the liver, kidney and lung, PEG-rGO was found in the liver and spleen. Moreover, PEG-rGO had a longer phase blood circulation half-life of 17.5 h compared to 5.8 ± 2.8 h for PEG-GO [88]. In 2016, Chen and coworkers coated PEG-rGO with gold superparticles (PEG-rGO-GSPs) for enhanced PTT. It was found that tumours in mice intravenously injected with PEG-rGO-GSPs (200 μL, 1 mg/mL) were successfully eliminated without reoccurrence after irradiation with 808 nm NIR laser (0.8 W/cm2, the surface temperature reached 58 °C within 5 min) while rGo or laser alone showed a rapid tumour regrowth rate similar to the control group [90].

Graphene-based materials incorporated with other particles can be combined with other therapeutic approaches, including chemotherapy (DOX [67, 87]), RT [91], immunotherapy [92], gene therapy [93], PTT enhanced PDT [7], and in vivo imaging-guided PTT/CT [94]. For example, Zhang et al. [87] developed PEGylated-GO loaded with DOX to achieve combined chemo-thermal cancer therapy. PEG-GO-DOX with a pH-dependent drug release showed a favorable drug delivery to acidic TME. Compared with CT or PTT alone, a higher efficacy was obtained for PEG-GO-DOX under NIR light (808 nm, 2 W/cm2) with a lower side effect over DOX alone both in vitro and in vivo [87]. In 2015, Chen and coworkers combined rGO with DOX and gold nanorods to achieve the combined chemo-thermal tumour inhibition and controlled DOX release (808 nm, 0.5 W/cm2, 5 min). In this case, the in vitro half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of rGO-Au-DOX was reported to be 0.63 μg/mL; approximately 2 times lower than that of free DOX (∼1.34 μg/mL) in U87MG cells. For mice treated with the rGO composite by 808 nm laser at 0.5 W/cm2, tumour growth was completely inhibited with no reoccurrence for 14 days and survived over 40 days after the irradiation; showing a similar tumour growth rate and survival period to control mice [95]. Targeting molecules could also be conjugated onto GO to achieve selective chemo-PTT therapeutic effects. In 2019, Huang et al. reported in vivo chemo-PTT effects with LA-DOX-GO in response to a 660 nm laser [96]. By further combining DOX-GO and Au@GO-supported BCL2 for tumour specifically targeting via π–π stacking, accurate diagnosis and efficient therapeutics could be achieved simultaneously. After the intratumoural injection of GO composites, tumour cells showed a higher expression of BCL2 in vivo and suppression of the prosurvival gene, leading to a synergistic PTT and CT effect compared with the control groups (Figure 4c) [67].

Apart from being combined with CT, several PDT photosensitizers, including FDA-approved drugs like Ce6 [7, 97], indocyanine green (ICG) [98, 99], methylene blue [100, 101] and AIE [102], have also been conjugated to GO to achieve optimal phototherapeutic effects. In 2011, Liu et al. functionalized GO with PEG and Ce6 to demonstrate PTT-enhanced PDT against cancer cells in response to a 660 nm laser at low power (50 mW/cm2, 5 min). Gulzar et al. reported that synergic PTT and PDT therapeutic effects could be achieved in vivo under 808 nm light by combining UCNP with Ce6 co-conjugated GO [103]. They pre-irradiated PEG-Ce6-GO with 808 nm laser (0.33 W/cm2, 20 min), with which Ce6 has no absorption, but the absorption of GO can generate heat to induce a 5–6 °C mild temperature increase, increasing the cellular uptake of PEG-Ce6-GO composite to enhance the in vitro photodynamic therapy of cancer cells [7]. In 2019, Zhang et al. loaded wedelolactone (WED) and indocyanine green (ICG) on the GO through π–π stacking interactions, and found that the resultant GO-ICG-WED reached a high heating rate of 79 °C in 10 min with a high singlet oxygen generation rate under 808 nm irradiation [98]. It has been argued that GO acts as a highly efficient fluorescence quencher to dramatically reduce ROS generation even conjugated with PDT agents [104]; however, only slight singlet oxygen generation quenching was observed for the GO-C60 hybrid [105]. In 2018, Sun, et al. [102] incorporated AIE (aggregation-induced emission) molecules (i.e., TPE-red) into PEG-GO and achieved bioimaging in targeted cells and mouse ear blood vessels. They demonstrated that the TPE-PEG-GO hybrid increased the significance of ROS production under 450 nm laser in PBS solution with significantly increased in vivo therapeutic effects on tumour inhibition over control groups [102].

Graphene-based materials were also applied for photoactive antimicrobial effects [9] and Alzheimer’s disease regulation [19]. Since 2010, graphene-based materials have been reported to show in vitro bacteria toxicity through membrane damage [8] caused by its sharp edges and phospholipids extraction between graphene and lipid molecules [106]. Thus, graphene-PTT conjugation has also been developed for anti-bacterial therapy. In 2017, tobramycin (Tob, a wide spectrum antibiotic molecule) and Cu doped GO hybrids were reported for in vitro and in vivo NIR (980 nm, 1.5 W/cm2, 5 min) PTT&PDT for antibacterial infection therapy with up to 70% biofilm eradication and nearly 100% bacteria inhibition [9]. Although CNMs doped with heavy metal ions could enhance PTT and PDT against bacterial infection, the release of Cu or other heavy metals in the human body often causes toxicity [86]. In 2021, Mei et al. [86] combined PEGylated GO with ZnPc for triple antibacterial therapy through dual irradiation (450 nm PTT and 680 nm PDT) for 10 min to generate hyperthermia of nearly 100 °C at the surface and singlet oxygen to oxide the bacterial membrane, achieving a synergistic antibacterial efficiency (for both gram-positive and gram-negative) in vitro and in vivo. For the groups treated with the GO hybrid, no bacteria residues on the surfaces of the rat wounds were observed 12 days after irradiation (Figure 4d) [86]. Furthermore, Liang et al. encapsulated GO with hydrogel for drug-resistant bacteria-infected wound healing [107]. Phototherapy is a promising strategy for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) via −β protein (Aβ) regulation, which is a major pathological hallmark of AD. Both PDT and PTT from CNMs can be applied to mitigate abnormal self-assembly Aβ-induced neurotoxicity [19]. In 2012, Li et al. modified GO with thioflavin-S to generate heat to dissociate the Aβ fibrils under NIR laser irradiation (1 W/cm2, 8 min) in a mice cerebrospinal fluid [41].

2.3 Fullerene (C60)

Just like CNTs and graphene-based materials discussed above, fullerene C60 has also been widely used for PTT/PDT. Having a soccer-ball-like fully-conjugated carbon structure consisting of 12 pentagons and 20 hexagons facing symmetrically, fullerene (C60) can strongly absorb visible light with interesting photoexcitation properties upon light exposure [108]. Upon irradiation, C60 is excited to a triplet state, which can transfer its energy to surrounding oxygen to form singlet oxygen (1O2) [105]. However, the poor NIR absorption and insolubility in the biological solution of unmodified C60 have strongly limited C60 for PDT [109].

UV–vis excitation of C60 has been applied for anti-bacteria under visible light and fullerenes could also be used in PTT, particularly modified C60 is already used for photodynamic cancer therapy [110]. Since 1997, C60 has been reported as the PDT agent for 1O2 formation under visible light for virus inactivation in biological fluids (Semliki Forest virus (SFV, Togaviridae) and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV, Rhabdoviridae)) [111]. In 2003, Yamakoshi et al. reported C60 for ROS generation in aqueous media under visible light and demonstrated a DNA cleavage capacity in DNA extracts [112]. To overcome the insolubility limitation of C60 mentioned above, serval modification strategies by introducing hydrophilic moieties, including water-soluble trimalonic acid functional groups like N-methylpyrrolidinium (BB4) [113], PEG [114], and block copolymers micelles, have been reported to acquire hydrophilic properties [115]. For instance, Hamblin and coworkers [115] reported cationic fullerenes as antimicrobial phototherapy agents; they modified C60 with pyrrolidinium groups, such as BF1–3 (three polar diserinol groups) and BF4–6 (a second series with one, two, or three quarternary pyrrolidinium groups), for anti-bacteria PDT under visible light irradiation (400–700 nm, 200 mW/cm2, 5 min). It was found that cationic C60 showed rapid and broad killing effects on more than 99.99% of bacterial and fungal cells and showed better selectivity than that widely used antimicrobial PDT agents (e.g., TBO, toluidine blue O) toward mouse fibroblast cells (L929) [115]. Later in 2011, Hamblin and coworkers used the same cationic fullerenes for intraperitoneal (IP) carcinomatosis PDT in the mice model (colon adenocarcinoma cell line (CT26) bearing BALB/c mice, IP injection) under visible light (400–700 nm) [113]. Krishna et al. [110] reported that up to 72% tumour size reduction under 785 nm laser irradiation of a water-soluble polyhydroxy fullerene (HPF) for 10 min (500 mW/cm2). Besides, HPF could also be used to image tumours with photoacoustic tomography (PAT) in BT474-bearing mice after intratumoural injection.

Although water solubility was improved, the phototherapy of modified fullerene was still limited to intratumoural injection. To achieve in vivo targeted area delivery of C60, PEG conjugated C60 has been studied for PDT of cancer in vivo under visible light [116]. PEG-modified C60 could be cooperated with other particles to achieve multifunctional systems. For example, in 2007, Liu et al. chelated Gd3+ to C60-PEG to enhance PDT efficacy with MRI under visible light (400–700 nm, 89.2 mW/cm2, 10 min), devising a therapeutic and diagnostic hybrid system in tumour-bearing mice (AR1/CDF1 mice) [114]. After intravenously injecting C60-PEG-Gd into mice, a sufficiently strong MRI signal from the tumour tissue was obtained for clinical MRI diagnosis.

Since C60-based PDT shows no specificity to tumour cells, tumour targeting agents, including peptides [47], aptamers [46], antibodies, and specific receptor-related molecules, were applied to further improve selectivity for selective inhibition of the tumour growth. In conjugation with tumour-targeting ligands (e.g., NGR that could cognize the CD13 isoform and tumour vascular), C60 showed a specific PDT inhibition of MCF-7 cells [47]. In 2010, Liu & Tabata functionalized C60 with pullulan (a polysaccharide with high affinity for asialoglycoprotein receptors; highly expressed at hepatocytes surface) for PDT of a HepG2 hepatoma cell line with high selectivity, leading to a 60% death of HepG2 cancer cells 6 h [117].

C60 could also be doped with other anti-cancer drugs (DOX [118]), metals [119], other CNMs or PAs (e.g., Ce6) [53] for CT-PDT and PTT-PDT synergic therapies. Indeed, Shi et al. [119] conjugated C60 with PEG, iron oxides (IONPs), and PDT anti-cancer drug HMME for PDT. By combining with C60, HOMME showed a 23-fold higher uptake of the tumour over HMME with significantly stronger killing effects. The resultant C60 hybrid was found in the liver, spleen, kidney, and tumour 3 h post-injection and showed excellent in vitro and in vivo PDT efficacies under 532 nm laser irradiation (300 mW/cm2, 5 min) [119].

Another form of fullerenes family C70 has also been applied for phototherapy. In 2016, Guan et al. decorated Amphiphilic TF-C70 with OEG2-modified Ce6 via a coupling reaction between amine groups on OMG2-Ce6 and carboxylic groups on TF-C70 to produce a water-soluble TFC70-OEG2-Ce6 (FCNVs) with 57 wt% Ce6. FCNVs demonstrated an imaging-guided PDT under NIR light at low laser intensity (660 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 10 min) [53]. Tumours (4T1 bearing Balb/c) treated with FCNVs with irradiation became scabby and ablated after 7 days and 15 days, respectively, while saline groups treated with the light or FCNVs alone showed continuous tumour growth for 15 days. FCNVs were found to accumulate in the liver, kidney, and tumour within 1–4 h post-injection while a negligible amount was detected in the spleen, lung muscle and heart. The half-life time was reported to be 73.6 h in the tumour. Overall, FCNVs showed no obvious damage to major organs and could be excreted by the liver and kidney with long-time blood circulation [53].

PEG crosslinked C60 was reported to be able to photoactively ablate various malignant cells after multimeric modification. In this context, Lee et al. reported [120] that Ce6 and folate conjugated PEG-C60 (multimeric C60) showed promising PTT and PDT therapeutic effects toward KB cancer, but with arthritis, after in intravenous injection. The surface temperature was found to reach 44 °C with tremendous singlet oxygen generation under 670 nm laser (300 mW/cm2, 10 min), resulting in arthritic progress inhibition in the arthritis-induced DBA/1 J mice mode and significant tumour volume regression in KB tumour-bearing mice (10 mg/kg).

2.4 Carbon quantum dots (CQDs)

Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) refer to CNMs sizes less than 10 nm [121]. Because different synthesis methods and precursors are used, CQDs are also called carbon dots (CDs) or graphene quantum dots (GQDs) for the dots synthesized from graphene. To avoid unnecessary confusion, we refer to all of them as CQDs in this review. Owing to their small size, tunable fluorescence, excellent water solubility and biocompatibility, high thermostability and photostability, CQDs are widely used for bio-applications [122], including biosensing [123, 124], bioimaging [125], and drug delivery [126]. Due to their size-dependent optical and other properties, CQDs could be used in both PDT and PTT within different wavelength ranges. CQDs show excellent renal clearance within (24–72 h) and cause no significant organ damage or inflammation, though CQDs predominantly accumulated in kidneys and liver, then spleen and lung [25, 127], [128], [129], [130].

Unlike other hydrophobic CNMs, hydrophilic CQDs could be directly applied for phototherapy. In 2015, Wang et al. reported sulfur-coated carbon quantum dots (S-CQDs) for PTT with a 38.5% photothermal conversion efficiency under a 671 nm laser at 2 W/cm2 (Figure 5a). S-CQDs accumulated in the tumour area after 2–5 h intravenous injection (2 mg/mL, 100 μL) and maintained photoacoustic imaging and fluorescence (λ ex = 540 nm) signals for image-guided photothermal therapy toward Hela tumour-bearing mice. S-CQDs treated groups showed a significant temperature increase (>60 °C) at the tumour area, along with tumour size suppression for 18 days after 671 nm laser exposure for 10 min, while mice in the laser alone or S-CQDs in dark groups showed continuous tumour growth [130]. In 2017, Wang and coworkers doped CQD with Se to further improve the PTT efficiency up to 58.2% at 635 nm laser (2 W/cm2) [131]. In 2018, Bao et al. [25] reported a 59% photothermal efficiency for NIR-PTT (at a low laser intensity; 655 nm, 1 W cm2, 5 min) with photoacoustic imaging capacity for CQDs from the classical route involving citric acid and urea [132] without any further modification. CQDs were found to accumulate in the tumour site after intravenous injection (1 mg/mL, 200 µL) and the maximum accumulation was reached at 3 h post-injection. Upon irradiation, the temperature in the tumour area reached 59–71 °C for the CQDs-treated groups, leading to 100% tumour reduction in H22 tumour-bearing ICR mice after 14 days [25].

CQD can be used as a PDT reagent itself or doped with other PAs via covalent binding [135, 136] or supramolecular self-assembling (π–π stacking) [137]. In 2012, Markovic et al. reported the use of CQDs as photocatalysts for in vitro PDT cancer treatment under blue visible light (470 nm). After irradiation (470 nm, 1 W) for 10 min, the cell viability of human glioma cells U251 was decreased by singlet oxygen generated from CQDs in the treated groups. It was found that the CQD-induced cell death pathways include both apoptosis and autophagy-induced PDT [138]. In 2014, Wang and coworkers synthesized CQDs, which showed a broad absorption in the visible light region with an emission peak at 680 nm. These CQDs exhibited a high 1O2 generation yield for efficient tumour inhibition under white light (400–800 nm, 80 mW/cm2, 10 min) in the MDA-MB-231 bearing mice model (Figure 5b). Tumours in irradiated groups treated with the CQDs showed a tumour size decrease after 9 days while tumours treated with CQDs or light alone continued to grow for 25 days (>1 cm3) (Figure 5c) [133]. Due to the poor tissue penetration of visible light, however, this application is limited to skin cancer. To overcome the drawback of tissue penetration and potential damage under visible light, several efforts have been made to push CQDs toward the NIR region. Zhao et al. prepared N, P co-doped red-emission CQDs (NPR-CDs) with a 1O2-generation capacity in response to visible light (532 nm). NPR-CQDs showed PDT efficiency toward A549 cancer cells and tumours bearing mice (2 mg/kg, irradiation 2 h post-intratumourally injection) under 532 nm laser (100 mW/cm2) for 4 min [139]. In 2017, Li et al. [140] synthesized near-NIR responsive N-CQDs from hydroxylphenyl triphenyl porphyrin (TPP) and chitosan via a hydrothermal method. N-CQDs thus produced showed phototherapeutic effects (1 h after intratumoural injection, 625 nm 16 m W/cm2, 1 h) to reduce tumour volume from 100 to 56 mm3 in mice while the control group reached ∼800 mm3. Although TPP itself showed a 52.74% in vivo tumour inhibition, the N-CQDs generated from TPP exhibited a much higher inhibition rate of 82.84% [140]. On the other hand, intravenous injection of near-NIR-responsive self-assembly of PEG-coated CQDs demonstrated an efficient singlet oxygen generation with a quantum yield of 45.4% in water or 34% in PBS under the 671 nm irradiation. However, the NIR-light-responsive PDT cytotoxicity reached up to ∼99% at 200 μg/mL of 4T1 cells (671 nm, 60 mW/cm2, 10 min). CQDs were accumulated in the tumour within 8 h post-i.v.-injection with excellent PDT effects after irradiation, leading to a significant reduction in tumour volume [70].

Most PAs require additional modification to obtain nucleolus-targeting ability, while some CQDs demonstrate the intrinsic nucleolus-targeting capability that could selectively label subcellular organelles [141–143]. For example, Pang et al. [143] developed nucleolus-targeting CQDs with enhanced light-induced photocytotoxicity (400–700 nm, 0.1 W/cm2, 20 min). The synergy between targeting and photodynamic therapy has been exploited in both in vitro and in vivo for more effective treatment.

Due to their excellent water solubility, modified CQDs could also act as a carrier for water-insoluble PAs (e.g., Ce6) [144]. As early as 2012, Chen and coworkers [144] decorated CQDs with Ce6 and PEG via covalent binding and demonstrated a promising anti-cancer PDT effect induced by CQDs-Ce6 at low laser intensity (671 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 10 min). Specifically, they found that CQDs-Ce6 accumulated in the tumour region after 2–4 h injection with an excellent tumour inhibition ability under irradiation whereas dark groups or Ce6 alone under irradiation showed no significant tumour volume growth compared to the saline control groups [144]. In 2016, Du et al. [69] reported that Ce6 could also be loaded onto CQDs via a disulfide bond, stabilized with PF-12 (CQD–SS–Ce6), and released through cleavage of the disulfide linker under the tumour intracellular GSH condition. CQDs injected via the vein (Ce6: 2.5 mg/kg) were found to accumulate in the tumour and liver after 30 min irradiation (650 nm, 200 mW/cm2, 30 min), leading to over 80% tumour reduction in Hela-bearing mice after 14 days.

The application of CQDs for phototherapy, however, is still limited by the potential tissue damage under high PTT power intensity (2 W/cm2) and the limited penetration depth for visible light. Several efforts have been reported to push CQDs toward the NIR region with a deeper tissue penetration. In 2016, Zheng et al. [145] synthesized NIR-emitting CQDs (from cyOH and PEG800) with a maximum absorption at 370 nm and photothermal conversion efficiency of 38.7% under an 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2). These CQDs demonstrated a high in vitro viability inhibition to HepG2 and CT26 cells (less than 13% and 25%, respectively) upon irradiation (2 W/cm2) for 5 min. The surface of CQDs-treated mice (CT26 tumour-bearing BALB/c) reached 45 °C after 5 min light exposure (808 nm, 1–1.5 W/cm2) and reached 91% tumour inhibitory rate on day 11 while the saline group and CQDs alone only showed 0% and 7.2% tumour inhibitory rate, respectively [145]. In 2018, Geng et al. [146] prepared N-CQDs from TNP and BPEI, and found a PTT efficiency of 38.3% in response to 808 nm laser at low power intensity (0.8 W/cm2, 5 min). At a low intratumoural injection dose (100 μg/mL, 100 μL), Hela-bearing balb/c nude mice showed 100% tumour destruction [146].

UCNPs that can convert NIR light into visible light have also been doped into CQDs for responding to NIR. In this context, CQDs that can efficiently produce 1O2 production under UV–vis light were doped with UCNP and TRITC for mitochondrial in-situ 1O2 PDT under 980 nm laser (0.5 W/cm2, 20 min) (Figure 5d) [134]. Zhang et al. reported that 4T1-bearing mice treated with UCNP-CQD and UCNP-CQD/TRITC with irradiation showed tumour inhibition rates of 70.2% and 75.3%, respectively, while tumour volume in control groups increased by about 11 folds after 20 days [134].

In addition to the CQDs responsive to the NIR-I discussed above, Liu et al. [68] reported the NIR-II responsive CQDs in 2020 (1064 nm, 0.4 W/cm2 for 24 min). The reported CQDs have a strong absorbance in the NIR-II region (∼1070 nm) and a photothermal efficiency of 33.45% under a 1064 nm laser (1 W/cm2). Both in vitro and in vivo PTT therapeutic effects were confirmed; CQDs-treated groups under irradiation showed significant tumour growth inhibition while the tumour sizes in control groups reached ∼6.2 times compared to their initial size after 14 days. The circulation half-life of CQDs in blood was reported to be 1.59 h. CQDs were found in the kidney, spleen, lung, tumour and heart 24 h after intravenous injection with no obvious toxicity to these organs, as evidenced by histological Analysis and gene expression analysis [68].

Photo-responsive CQDs could also be cooperated with other strategies, such as chemotherapy [147] and NO delivery [148], to achieve synergic cancer therapeutic effects. Moreover, apart from anticancer applications, CQDs can also be implied for photo-induced anti-bacteria and AD regulations [19]. For example, Ristic et al. reported CQDs synthesized via electrochemical methods showed PDT anti-bacterial effects against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli under visible light (470 nm, 1 W) [149]. Zhang et al. developed HA-conjugated CQDs that could generate singlet oxygen under 650 nm laser irradiation, showing a selective inhibition of CD44-overexpressing cancer cells [150].

2.5 Carbon nitride (C3N4)

Carbon nitride is a promising photocatalyst, but pure C3N4 absorb visible light only. This restricts its phototherapy applications due to the low penetration depth associated with and potential skin damage caused by visible light [151–153]. Nevertheless, metal-doped carbon nitride has been reported for NIR-PDT [154]. In 2019, Li, et al. [154] loaded Ru and Fe on HOP-conjugated C3N4 (FCRH) for O2 self-supplement PDT under two-photon light (800 nm, 2.7 W, 5 min). After accumulation in the tumour tissue, FCRH can overcome hypoxia via O2 generation from water splitting under irradiation and enhanced PDT 1O2 generation, leading to significant tumour inhibition for 14 days [154]. Also, Taheri et al. [155] reported the use of mesoporous g-C3N4 (mgp-C3N4) without any modification for both in vitro and in vivo for PDT under 490 nm light (50 W, 1 h) in 2020. C3N4 was found to accumulate in the liver, lung, spleen, and tumour site, after intravenous injection, with no obvious organ damage. Both intratumoural and intravenous administration of the C3N4 resulted in a significant decrease in tumour volume after light exposure [155].

C3N4 could also be doped with other anti-cancer drugs for synergic therapies. For example, C3N4 nanosphere (HCNS) could load DOX for PDT-enhanced CT under visible light [156]. In 2020, Sun et al. reported a sono-photodynamical therapy strategy based on C3N4 self-assembled with Ce6-incorporated polycaprolactone/gelatin (PG). The resultant C3N4 hybrids significantly boosted ROS generation through a synergistic 808 nm laser (1 W/cm2, 5 min) and 1 MHz ultrasound (1 W/cm2, 50% duty cycle, 5 min) excitation, achieving a 95.8% inactivation rate for breast cancer cells [157].

2.6 Other CNMs

In addition to carbon nanotubes, graphene, fullerene, and carbon quantum dots discussed above, many other carbon materials have also been studied for PTT applications. For instance, carbon shell combined with metal was reported for PTT-enhanced CT under 808 nm lasers for in vitro cancer therapy in 2021 [158]. Dai et al. reported that the intravenously administrated FeCo-coated graphitic carbon shell loaded with DOX (FeCo/GC-DOX) showed a 45% tumour regression in mice with 20 min light exposure (NIR, surface reached 43–45 °C) [159]. In 2019, Lin et al. reported carbon nanohorns (CNHs) doped with PC (PC-SWNH) for PTT and PDT combined cancer therapy under 650 nm laser (1 W/cm2, 10 min). SWCH was found to act as a promising PTT agent. Combined with PDT, PC-SWNH showed tumour inhibition both in vitro and vivo [160]. More recently, Chen et al., synthesized C5N2 for PDT in response to a 655 nm laser for O2 generation via water splitting, demonstrating a promising inhibition for hypoxic tumours [161]. In a somewhat related but independent study, Hu et al. designed a PDA conjunction with C60 and rGO, which caused significant apoptosis toward Hela cells under light irradiation (Xe light 400–1100 nm, 2 W/cm2, 9 min) through singlet oxygen generation from C60 in NIR region [109] without decreasing the PTT effect of GO. GO-C60 was further modified with hydrophilic PEG to enhance its solubility, and the resultant PEG-GO-C60 was used for combined PTT and PDT in an aqueous solution for cancer therapy and antibacterial therapy [109]. Apart from anti-cancer and anti-bacterial phototherapy, C3N4 and CQDs hybrids were reported for in vitro photoactive inhibition of Aβ aggregation by ROS generated under white light illumination [19].

Finally, nanodiamond (ND) as a new class of diamond-structured carbon nanomaterial at nanoscale (<10 nm) exhibits strong photo-responsive properties and easy surface modification potential, making NDs a competitive candidate for various bio-applications like drug delivery and anti-cancer phototherapy [162–164]. For example, Choi and coworkers [165] proposed the folic acid (FA) conjugated NDs for selective folate receptor positive cancer cells (KB) photothermal therapy. They reported a significant tumour volume reduction in KB-bearing mice after 14 days post intravenous injection and NIR irradiation (808 nm, 2 W/cm2, 5 min). Later in 2018, Choi and coworkers designed a PDT and PTT synergistic phototherapy based on NDs [166], by decorating the phase-change material (PCM) and Ce6 to the NDs.

In summary, Table 1 summarizes the CNMs for PTT/PDT cancer therapy. Similarly, CNMs can have a photo-active antimicrobial effect from both PTT and PDT effects. For example, Lu et al., functionalized fullerenes with cation photodynamic therapy for potentially deadly skin wounds with ProteusMirabilis infection. After white light exposure (400–700 nm, 180 J/cm2) fullerenes treated group showed 82% survival compared to 8% in the control groups [167]. In 2010 [8] Akhavan and Ghaderi reported PTT graphene-based materials for anti-bacterial therapy, which could also be doped with metal for PTT/PDT antibacterial infection [9]. Although heavy metal ions doped CNM could enhance PTT and PDT against bacterial infection, the release of Cu or other heavy metals could cause toxicity in the human body [86].

Summary of CNMs for cancer treatments.

| CNM | Application | NP components | Phototherapy | Year | Ref | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | PTT | PDT | Other | Wavelength | Power | Time | Therapeutic effects | ||||

| (nm) | (W/cm2) | (min) | |||||||||

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT | – | SWCNT | – | – | 800 | ∼50–200 | In vitro breast cancer BT474 inhibition | 2007 | [55] | |

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT | – | SWCNT | – | – | 808 | 1.4 | 2 | In vitro cancer cells inhibition | 2005 | [168] |

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT | IGF1 HER2 | SWCNT | – | – | 808 | ∼800 | 3 | In vitro breast cancer cells MCF-7 inhibition | 2007 | [61] |

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT | CD25 mAb | SWCNT | – | – | 808 | 5 | 7 | In vitro cancer cells inhibition | 2008 | [62] |

| MWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT | anti-GD2 | MWCNT | – | – | 808 | 0.6–6 + 6 | 10 + 5 | In vitro cancer cells inhibition | 2009 | [59] |

| MWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT | – | MWCNT | – | DNA | 1064 | 2.5 | 1.17 | In vivo tumour disappeared irradiation 1.5 h after intertumoural injection | 2009 | [64] |

| MWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT + CT | CD44 HA | MWCNT | – | PEG DOX | 808 | 1 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition reduced cytotoxicity of DOX | 2021 | [66] |

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT | – | SWCNT | – | PEG | 808 | 76 | 3 | In vivo intravenous injection tumour disappeared no recurrence over 6 months | 2009 | [44] |

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT | – | SWCNT | – | PEG | 808 | 0.6 | 5 | In vivo low injection dose, 3.6 mg/kg intravenous injection tumour disappeared no recurrence ∼6 months | 2010 | [74] |

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT | anti-CTLA-4 | SWCNT | – | PEG | 808 | 1 | 10 | In vivo intravenous injection immune response tumour disappeared inhibited pulmonary metastasis | 2014 | [71] |

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PDT | FA | – | SWCNT | PEG | 980 | 0.75 | 2 | In vitro FR-positive cells | 2014 | [75] |

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | SWCNT | PEI | 300–2600 | 200 W at 20 cm | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2014 | [58] | |

| distance for 1 or 2 h | |||||||||||

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT image | – | SWCNT | – | PEG DOX MS | 808 | 0.7 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2015 | [79] |

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT + RIT | – | – | – | PEG Mn2+ | In vivo tumour inhibition MRI imaging | 2016 | [73] | |||

| SWCNT | Anti-cancer PTT | – | SWCNT | – | PEG | 808 | 0.5 & 0.8 | 12 | Imaging destruction of primary tumours inhibited metastasis in sentinel lymph nodes | 2014 | [72]. |

| CNT | Anti-bacterial wound healing PTT | – | CNT | – | QCS GMA | 808 | 1.4 | 10 | In vivo tumour inhibition noncompressible hemorrhage and wound healing | 2018 | [169] |

| SWCNT | Vascular inflammation PTT | – | SWCNT | – | Cy5.5 PEG | 808 | 5 | 2 | In vivo tumour inhibition tail injection | 2012 | [170] |

| SWCNT | In vivo tumour image | – | SWCNT | – | – | – | – | – | In vivo tumour inhibition imaging | 2012 | [57] |

| SWCNT-Fe3O4 | PTT PDT CT | – | SWCNT | Fe3O4 | DOX PEG | 808 | 2 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2018 | [80] |

| GO | Anti-cancer PTT | – | GO | – | PEG | 808 | 2 | 5 | In vivo the tumour disappeared after 1 day, no recurrence | 2010 | [84] |

| rGO | Anti-cancer PTT | RGD | rGO | – | – | 808 | 15.3 | 8 | In vitro cancer cells U87MG inhibition | 2011 | [89] |

| rGO | Anti-cancer PTT | – | rGO | – | PEG | 808 | 0.15 | 5 | In vivo tumour elimination no obvious side effect after 100 days | 2012 | [88] |

| rGO | Anti-cancer PTT | – | rGO | – | PEG | 808 | 0.8 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition tumour elimination without reoccurrence | 2016 | [90] |

| GO | Anti-cancer PTT + CT | – | GO | – | DOX PEG | 808 | 2 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition PH-dependent drug release tumour elimination without reoccurrence | 2011 | [87] |

| rGO | Anti-cancer PTT + CT | – | rGO | – | PEG Au DOX | 808 | 0.25 | 3 | In vivo acid-triggered DOX release tumour growth inhibition | 2015 | [95] |

| GO | Anti-cancer PTT + CT | LA | GO ICG(IR820) | – | DOX | 660 | 1 | 5 | In vivo pH-sensitive drug release tumour inhibition after 3 weeks | 2019 | [96] |

| GO | Anti-cancer PTT + CT | BCL2 | GO | – | DOX Au | 808 | 1.2 | 10 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2021 | [67] |

| GO Ce6 PEG | Anti-cancer PTT + PDT | – | GO | Ce6 | PEG | 808 + 660 | 0.33 + 0.05 | 20 + 5 | In vitro cancer cells inhibition | 2011 | [7] |

| GO Ce6 UCNP | Anti-cancer PTT + PDT | – | GO | Ce6 | PEG | 808 | 0.72 | 10 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2018 | [103] |

| GO | Anti-cancer PTT + PDT | – | GO | ICG WED | – | 808 | 2 | 1 | In vivo cancer cells inhibition tumour elimination after 14days | 2019 | [98] |

| GO | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | AIE | – | 450 | 0.2 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2018 | [102] |

| GO | Anti-cancer PTT-CT anti-cancer | – | GO | Fe | DOX PEG | 808 | 1 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2012 | [94] |

| GO | PTT PDT | – | GO | MB | – | 808 | 2 | 3 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2013 | [49] |

| GO | Anti-cancer PTT + PDT | Folic acid | GO | ICG | PEG | 808 | 1.8 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2021 | [171] |

| C60 | Anti-virus PDT | – | – | C60 | – | – | – | – | In vitro virus inhibition | 1997 | [111] |

| C60 cationic | Anti-bacteria PDT | – | – | C60 | BF1-6 | 400–700 | 120 J/cm2 | 5 | In vitro more than 99.99% of bacterial and fungal cells | 2005 | [115] |

| C60 cationic | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | C60 | BB4 | 400–700 | 0.2 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition intraperitoneal(IP) carcinomatosis | 2011 | [113] |

| C60 HPF | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | C60 | – | 785 | 0.5 | 10 | In vivo up to 72% tumour size reduction intratumourally injection | 2010 | [110] |

| C60 | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | C60 | PEG Gd3+ | 400–700 | 0.089 | 10 | In vivo tumour inhibition MRI imaging | 2007 | [114] |

| C60 | Anti-cancer PDT | Pullulan | – | C60 | – | 400–700 | 8 W 2 cm | 5 | In vitro 60% death of HepG2 cancer cells | 2010 | [117] |

| C60 | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | C60 | – | 532 | 0.3 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2013 | [119] |

| C60 | Anti-cancer and arthritis PDT | – | – | C60 | – | 670 | 0.3 | 10 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2012 | [120] |

| C60 | Anti-bacteria PDT | – | – | C60 | – | 400–700 | 120 J/cm2 | – | In vitro bacteria inhibition | 2005 | [115] |

| C60 | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | C60 | – | 400–700 | 8 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2016 | [53] |

| C70 OEG2 Ce6 | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | C70 Ce6 | OMG2 | 660 | 0.1 | 10 | In vivo tumour disappeared | 2016 | [53] |

| C60 IONPs HMME PEG | Anti-cancer PDT CT | – | – | C60 IONP | HMME PEG | 532 | 0.3 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2013 | [119] |

| C60-GO | Anti-cancer PTT PDT | – | GO | C60 | PDA | 400–1100 | 2 | 9 | In vitro cancer cell inhibition | 2014 | [105] |

| CQDs | Anti-cancer PDT | CQDs | – | CQDs | – | 400–700 | 0.1 | 20 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2020 | [143] |

| CQDs Ce6 PEG | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | Ce6 | PEG | 671 | 0.1 | 10 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2012 | [144] |

| CQDs | Anti-cancer PTT | – | – | CQDs | – | 671 | 2 | 10 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2015 | [130] |

| CQDs | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | CQDs | – | 625 | 0.016 | 60 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2016 | [140] |

| CQDs | Anti-cancer PTT + PDT | – | CQDs | CQDs | – | 800 | 0.5 | 10 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2018 | [172] |

| CQDs N, P co CQDs | Anti-cancer PDT | – | – | CQDs | – | 532 | 0.1 | 4 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2019 | [139] |

| CQDs | Anti-cancer PDT imaging | – | – | CQDs | PEG | 671 | 0.1 | 10 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2019 | [173] |

| CQDs | Anti-cancer PTT | – | – | CQDs | – | 808 | 0.05 | 10 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2019 | [174] |

| C3N4 N-CQDs | Anti-cancer PTT + PDT | RGD | – | C3N4 | PEG | 980 | 1 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2020 | [52] |

| 630 | 0.155 | 5 | |||||||||

| CQDs | Anti-cancer PTT | – | CQDs | – | – | 1064 | 0.4 | 24 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2020 | [68] |

| C3N4 GO Ce6 | Anti-cancer PDT + Sono | – | GO | C3N4 Ce6 | – | 808 | 1 | 5 | In vivo tumour inhibition | 2020 | [157] |

| ND | Anti-cancer PTT | FA | ND | – | – | 808 | 2 | 5 | In vivo tumour volume reduction | 2016 | [165] |

| ND | Anti-cancer PTT + PDT | – | ND | Ce6 | PCM | 670 | 2 | 4 | In vivo tumour volume reduction | 2018 | [166] |

3 Conclusion and outlook

As can be seen above, carbon nanomaterials exhibit good photo-responsive activities and stabilities to show great potential for phototherapy. Various functionalization strategies have been developed to enhance the low water-solubility, weak NIR absorption, and poor targeting capability intrinsically associated with certain specific CNMs for optimal PTT/PTD performance. Although significant progress has been achieved, the following issues still need to be addressed towards clinical translation.

Firstly, further study on long-term biosafety in the clinical use of CNMs is needed since carbon nanomaterials are very stable in biological environment. Although research progresses achieved to date have demonstrated no adverse effects in mice even over 6 months for some CNMs, their detailed metabolic behavior impacts, and long-term evaluations remain uncertain.

Secondly, to maximize the treatment effects on deep tumours/other diseases, CNMs needed to be combined with NIR-responsive PAs and/or other therapeutic strategies. However, most CNMs currently reported for PTT/PDT applications are responsive mainly to the NIR-I region, which still has some limitations on tissue penetration compared to the NIR-II region. So, more advanced PAs are needed to push the light absorption toward the NIR-II region, maximize the blood circulation time, and improve the conversion efficiency of light energy to chemical/thermal energy.

Lastly, more mechanistic studies are necessary to guide the design and synthesis advanced NIR-responsive CNMs with controlled PTT/PDT properties. This is the foundation for clinical translation and future personalized phototherapeutic treatment.

We believe that these issues and others will be resolved with the rapid development in carbon materials science and engineering, surface modification, catalytic medicine, and phototherapeutic technology. CNMs will revolutionarize the field of phototherapy and affect every aspect of our lives.

List of Acronyms

- AD

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- AIE

-

aggregation-induced emission

- BB4

-

N-methylpyrrolidinium

- BF1–3

-

three polar diserinol groups

- BF4–6

-

a second series with one, two, or three quarternary pyrrolidinium groups

- C60

-

fullerene

- Ce6

-

chlorin e6

- CNM

-

carbon nanomaterial

- CNT

-

carbon nanotubes

- C3N4

-

carbon nitride

- CPT

-

camptothecin

- CQDs

-

carbon quantum dots

- CT

-

chemotherapy

- DOX

-

Doxorubicin

- FA

-

folate acid

- FCNVs

-

OMG2-Ce6 and carboxylic groups coupled on TFC70

- GO

-

graphene oxides

- GQDs

-

graphene quantum dots

- HA

-

Hyaluronic acid

- HOP

-

Poly (ethylene glycol) arms

- HPF

-

water-soluble polyhydroxy fullerene

- ICG

-

indocyanine green

- IP

-

intraperitoneal

- LA

-

lactobionic acid

- MB

-

methylene blue

- MWCNTs

-

multi-walled carbon nanotubes

- MR

-

magnetic resonance

- MS

-

mesoporous silica

- NIR

-

near-infrared

- NGR

-

Asn-Gly-Arg peptides

- PA

-

phototherapeutic agents

- PAT

-

photoacoustic tomography

- PDA

-

polydopamine

- PDT

-

photodynamical therapy

- PEG

-

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PEI

-

polyethylenimine

- PL

-

photoluminescence

- PTT

-

photothermal therapy

- PT

-

phototherapy

- PAs

-

phototherapeutic agents

- RES

-

reticuloendothelial system

- rGO

-

reduced graphene oxides

- RIT

-

radioisotope therapy

- ROS

-

reactive oxygen species

- S-CDs

-

sulfur coated carbon quantum dots

- SWCNT

-

single-walled carbon nanotubes

- SFV

-

Semliki Forest virus

- TBO

-

toluidine blue O

- TME

-

tumour microenvironment

- TPP

-

triphenyl porphyrin

- UCNP

-

upconversion nanoparticles

- VSV

-

vesicular stomatitis virus

- WED

-

wedelolactone

Funding source: Australian Research Council

Award Identifier / Grant number: DP200103587

Award Identifier / Grant number: FL190100126

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

[1] J. Liu, J. Shi, W. Nie, S. Wang, G. Liu, and K. Cai, “Recent progress in the development of multifunctional nanoplatform for precise tumour phototherapy,” Adv. Healthcare Mater., vol. 10, pp. 1–23, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202001207.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] B. Zhou, Z. Guo, Z. Lin, L. Zhang, B. P. Jiang, and X. C. Shen, “Recent insights into near-infrared light-responsive carbon dots for bioimaging and cancer phototherapy,” Inorg. Chem. Front., vol. 6, pp. 1116–1128, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9qi00201d.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] W. Zhu, M. Kang, Q. Wu, et al.., “Zwitterionic AIEgens: rational molecular design for NIR-II fluorescence imaging-guided synergistic phototherapy,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 2007026, pp. 1–11, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202007026.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] D. An, J. Fu, B. Zhang, et al.., “NIR-II responsive inorganic 2D nanomaterials for cancer photothermal therapy: recent advances and future challenges,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 31, p. 2101625, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ADFM.202101625.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Y. Chang, Q. Bai, M. Wang, et al.., “Plasmonic Bi nanoparticles encapsulated by N-Carbon for dual-imaging and photothermal/photodynamic/chemo-therapy,” Biomater. Adv., vol. 134, p. 112546, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MSEC.2021.112546.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] G. Wu, B. Jiang, L. Zhou, A. Wang, and S. Wei, “Coconut-shell-derived activated carbon for NIR photo-activated synergistic photothermal-chemodynamic cancer therapy,” J. Mater. Chem. B, vol. 9, pp. 2447–2456, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0tb02782k.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] B. Tian, C. Wang, S. Zhang, L. Feng, and Z. Liu, “Photothermally enhanced photodynamic therapy delivered by nano-graphene oxide,” ACS Nano, vol. 5, pp. 7000–7009, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn201560b.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] O. Akhavan and E. Ghaderi, “Toxicity of graphene and graphene oxide nanowalls against bacteria,” ACS Nano, vol. 4, pp. 5731–5736, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1021/NN101390X/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/NN-2010-01390X_0005.JPEG.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] X. Dai, Y. Zhao, Y. Yu, et al.., “All-in-one NIR-activated nanoplatforms for enhanced bacterial biofilm eradication,” Nanoscale, vol. 10, pp. 18520–18530, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8NR04748K.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Y. Li, W. Zhu, J. Li, and H. Chu, “Research progress in nanozyme-based composite materials for fighting against bacteria and biofilms,” Colloids Surf., B, vol. 198, p. 111465, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111465.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Z. Xie, T. Fan, J. An, et al.., “Emerging combination strategies with phototherapy in cancer nanomedicine,” Chem. Soc. Rev., vol. 49, pp. 8065–8087, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0CS00215A.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] K. Chen, P. He, Z. Wang, and B. Z. Tang, “A feasible strategy of fabricating type i photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy in cancer cells and pathogens,” ACS Nano, vol. 15, pp. 7735–7743, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACSNANO.1C01577/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/NN1C01577_0006.JPEG.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Y. Wan, L. H. Fu, C. Li, et al.., “Conquering the hypoxia limitation for photodynamic therapy,” Adv. Mater., vol. 33, p. 2103978, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ADMA.202103978.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Y. N. Konan, R. Gurny, and E. Allémann, “State of the art in the delivery of photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy,” J. Photochem. Photobiol., B, vol. 66, pp. 89–106, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1011-1344(01)00267-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] S. S. Lucky, K. C. Soo, and Y. Zhang, “Nanoparticles in photodynamic therapy,” Chem. Rev., vol. 115, pp. 1990–2042, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1021/CR5004198/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/CR-2014-004198_0033.JPEG.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Z. Xiang, L. Zhu, L. Qi, et al.., “Two-dimensional fully conjugated polymeric photosensitizers for advanced photodynamic therapy,” Chem. Mater., vol. 28, pp. 8651–8658, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b03619.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] L. Ma, Y. Zhou, Z. Zhang, et al.., “Multifunctional bioactive Nd-Ca-Si glasses for fluorescence thermometry, photothermal therapy, and burn tissue repair,” Sci. Adv., vol. 6, no. 32, p. 1311, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIADV.ABB1311/SUPPL_FILE/ABB1311_SM.PDF.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] L. Cîrcioban, I. Pinzaru, C. Trandafirescu, et al.., “Cyclodextrin-based nanoplatforms for tumour phototherapy: an update,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 14, p. 1375, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/PHARMACEUTICS14071375.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] W. Liu, X. Dong, Y. Liu, and Y. Sun, “Photoresponsive materials for intensified modulation of Alzheimer’s amyloid-β protein aggregation: a review,” Acta Biomater., vol. 123, pp. 93–109, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ACTBIO.2021.01.018.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] H. Kang, S. Hu, M. H. Cho, S. H. Hong, Y. Choi, and H. S. Choi, “Theranostic nanosystems for targeted cancer therapy,” Nano Today, vol. 23, pp. 59–72, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NANTOD.2018.11.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] X. Song, L. Feng, C. Liang, K. Yang, and Z. Liu, “Ultrasound triggered tumour oxygenation with oxygen-shuttle nanoperfluorocarbon to overcome hypoxia-associated resistance in cancer therapies,” Nano Lett., vol. 16, pp. 6145–6153, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.NANOLETT.6B02365/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/NL-2016-023658_0006.JPEG.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] T. Luo, K. Ni, A. Culbert, et al.., “Nanoscale metal-organic frameworks stabilize bacteriochlorins for type i and type II photodynamic therapy,” J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 142, pp. 7334–7339, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/JACS.0C02129/SUPPL_FILE/JA0C02129_SI_002.CIF.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Z. Bao, K. Li, P. Hou, R. Xiao, Y. Yuan, and Z. Sun, “Nanoscale metal-organic framework composites for phototherapy and synergistic therapy of cancer,” Mater. Chem. Front., vol. 5, pp. 1632–1654, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0qm00786b.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] J. Zhao, K. Yan, G. Xu, et al.., “An iridium (III) complex bearing a donor–acceptor–donor type ligand for NIR-triggered dual phototherapy,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 31, no. 11, p. 2008325, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202008325.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] X. Bao, Y. Yuan, J. Chen, et al.., “In vivo theranostics with near-infrared-emitting carbon dots—highly efficient photothermal therapy based on passive targeting after intravenous administration,” Light: Sci. Appl., vol. 7, pp. 1–11, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-018-0090-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] B. del Rosal, B. Jia, and D. Jaque, “Beyond phototherapy: recent advances in multifunctional fluorescent nanoparticles for light-triggered tumour theranostics,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 28, pp. 1–25, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201803733.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] K. Yang, J. Wan, S. Zhang, Y. Zhang, S.-T. Lee, and Z. Liu, “In vivo pharmacokinetics, long-term biodistribution, and toxicology of PEGylated graphene in mice,” ACS Nano, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 516–522, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn1024303.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] J. Saleem, L. Wang, and C. Chen, “Carbon-based nanomaterials for cancer therapy via targeting tumour microenvironment,” Adv. Healthcare Mater., vol. 7, pp. 1–30, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201800525.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] L. Dai, Carbon-Based Metal-free Catalysts: Design and Applications, Weinheim, Germany, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2018.10.1002/9783527811458Suche in Google Scholar

[30] M. S. Dresselhaus and P. T. Araujo, “Perspectives on the 2010 nobel prize in physics for graphene,” ACS Nano, vol. 4, pp. 6297–6302, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1021/NN1029789/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/NN-2010-029789_0003.JPEG.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] A. Javey, “The 2008 Kavli prize in nanoscience: carbon nanotubes,” ACS Nano, vol. 2, pp. 1329–1335, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1021/NN8003982/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/NN-2008-003982_0006.JPEG.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] C. Hu, Q. Dai, and L. Dai, “Multifunctional carbon-based metal-free catalysts for advanced energy conversion and storage,” Cell Rep. Phys. Sci., vol. 2, p. 100328, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.XCRP.2021.100328.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Z. Cheng, M. Li, R. Dey, and Y. Chen, “Nanomaterials for cancer therapy: current progress and perspectives,” J. Hematol. Oncol., vol. 14, pp. 1–27, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01096-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] M. Sajjadi, M. Nasrollahzadeh, B. Jaleh, G. J. Soufi, and S. Iravani, “Carbon-based nanomaterials for targeted cancer nanotherapy: recent trends and future prospects,” J. Drug Targeting, vol. 29, pp. 716–741, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/1061186X.2021.1886301.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] N. A. Saeed, I. H. Hamzah, and S. I. Mahmood, “The applications of nano-medicine in the breast cancer therapy,” J. Phys.: Conf. Ser., vol. 1853, no. 12, pp. 5879–5892, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1853/1/012061.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Y. Yang, X. Yang, Y. Yang, and Q. Yuan, “Aptamer-functionalized carbon nanomaterials electrochemical sensors for detecting cancer relevant biomolecules,” Carbon, vol. 129, pp. 380–395, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2017.12.013.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] G. Nocito, G. Calabrese, S. Forte, et al.., “Carbon dots as promising tools for cancer diagnosis and therapy,” Cancers, vol. 13, pp. 1–14, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13091991.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] C. Martín, A. Ruiz, S. Keshavan, et al.., “A biodegradable multifunctional graphene oxide platform for targeted cancer therapy,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 1901761, pp. 1–11, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201901761.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] M. Shamsipur, A. Safavi, and Z. Mohammadpour, “Indirect colorimetric detection of glutathione based on its radical restoration ability using carbon nanodots as nanozymes,” Sens. Actuators, B, vol. 199, pp. 463–469, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2014.04.006.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] P. Das, S. Ganguly, S. Mondal, et al.., “Heteroatom doped photoluminescent carbon dots for sensitive detection of acetone in human fluids,” Sens. Actuators, B, vol. 266, pp. 583–593, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2018.03.183.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] M. Li, X. Yang, J. Ren, et al.., “Using graphene oxide high near-infrared absorbance for photothermal treatment of Alzheimer’s disease,” Adv. Mater., vol. 24, pp. 1722–1728, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/ADMA.201104864.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] S. Wen, Q. Zhao, X. An, et al.., “Multifunctional PEGylated multiwalled carbon nanotubes for enhanced blood pool and tumour MR imaging,” Adv. Healthcare Mater., vol. 3, pp. 1568–1577, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/ADHM.201300631.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] G. H. Tondro, N. Behzadpour, Z. Keykhaee, N. Akbari, and N. Sattarahmady, “Carbon@polypyrrole nanotubes as a photosensitizer in laser phototherapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa,” Colloids Surf., B, vol. 180, pp. 481–486, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.05.020.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] H. K. Moon, S. H. Lee, and H. C. Choi, “In vivo near-infrared mediated tumour destruction by photothermal effect of carbon nanotubes,” ACS Nano, vol. 3, pp. 3707–3713, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1021/NN900904H/SUPPL_FILE/NN900904H_SI_002.PDF.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] M. Zheng, A. Jagota, E. D. Semke, et al.., “DNA-assisted dispersion and separation of carbon nanotubes,” Nat. Mater., vol. 2, pp. 338–342, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat877.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Q. Liu, L. Xu, X. Zhang, et al.., “Enhanced photodynamic efficiency of an aptamer-guided fullerene photosensitizer toward tumour cells,” Chem. Asian J., vol. 8, pp. 2370–2376, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/ASIA.201300039.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] J. Shi, Z. Wang, L. Wang, et al.., “Photodynamic therapy of a 2-methoxyestradiol tumour-targeting drug delivery system mediated by Asn-Gly-Arg in breast cancer,” Int. J. Nanomed., vol. 8, p. 1551, 2013. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S40011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] X. Li, J. F. Lovell, J. Yoon, and X. Chen, “Clinical development and potential of photothermal and photodynamic therapies for cancer,” Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol., vol. 17, pp. 657–674, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-0410-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] A. Sahu, W. il Choi, J. H. Lee, and G. Tae, “Graphene oxide mediated delivery of methylene blue for combined photodynamic and photothermal therapy,” Biomaterials, vol. 34, pp. 6239–6248, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOMATERIALS.2013.04.066.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] D. Wang, L. Zhu, J. Chen, and L. Dai, “Liquid marbles based on magnetic upconversion nanoparticles as magnetically and optically responsive miniature reactors for photocatalysis and photodynamic therapy,” Angew. Chem., vol. 128, pp. 10953–10957, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.201604781.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] D. Wang, L. Zhu, Y. Pu, J. X. Wang, J. F. Chen, and L. Dai, “Transferrin-coated magnetic upconversion nanoparticles for efficient photodynamic therapy with near-infrared irradiation and luminescence bioimaging,” Nanoscale, vol. 9, pp. 11214–11221, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7nr03019c.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] X. Zhang, J. Ong’achwa Machuki, W. Pan, et al.., “Carbon nitride hollow theranostic nanoregulators executing laser-activatable water splitting for enhanced ultrasound/fluorescence imaging and cooperative phototherapy,” ACS Nano, vol. 14, pp. 4045–4060, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b08737.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] M. Guan, J. Ge, J. Wu, et al.., “Fullerene/photosensitizer nanovesicles as highly efficient and clearable phototheranostics with enhanced tumour accumulation for cancer therapy,” Biomaterials, vol. 103, pp. 75–85, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOMATERIALS.2016.06.023.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] C. Hu and L. Dai, “Doping of carbon materials for metal-free electrocatalysis,” Adv. Mater., vol. 31, p. 1804672, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201804672.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] B. Panchapakesan, S. Lu, K. Sivakumar, K. Teker, G. Cesarone, and E. Wickstrom, “Single-wall carbon nanotube nanobomb agents for killing breast cancer cells,” NanoBiotechnology, vol. 1, pp. 133–139, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1385/NBT:1:2:133.10.1385/NBT:1:2:133Suche in Google Scholar

[56] J. Zhao, D. Zhong, and S. Zhou, “NIR-I-to-NIR-II fluorescent nanomaterials for biomedical imaging and cancer therapy,” J. Mater. Chem. B, vol. 6, pp. 349–365, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7TB02573D.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] J. T. Robinson, G. Hong, Y. Liang, B. Zhang, O. K. Yaghi, and H. Dai, “In vivo fluorescence imaging in the second near-infrared window with long circulating carbon nanotubes capable of ultrahigh tumor uptake,” J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 134, pp. 10664–10669, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja303737a.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] L. Wang, J. Shi, R. Liu, et al.., “Photodynamic effect of functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes: a potential sensitizer for photodynamic therapy,” Nanoscale, vol. 6, pp. 4642–4651, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3nr06835h.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] C. H. Wang, Y. J. Huang, C. W. Chang, W. M. Hsu, and C. A. Peng, “In vitro photothermal destruction of neuroblastoma cells using carbon nanotubes conjugated with GD2 monoclonal antibody,” Nanotechnology, vol. 20, p. 315101, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/20/31/315101.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] X. Lu, Y. Zhu, R. Bai, et al.., “Long-term pulmonary exposure to multi-walled carbon nanotubes promotes breast cancer metastatic cascades,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 14, pp. 719–727, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0472-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] N. Shao, S. Lu, E. Wickstrom, and B. Panchapakesan, “Integrated molecular targeting of IGF1R and HER2 surface receptors and destruction of breast cancer cells using single wall carbon nanotubes,” Nanotechnology, vol. 18, p. 315101, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/18/31/315101.Suche in Google Scholar

[62] P. Chakravarty, R. Marches, N. S. Zimmerman, et al.., “Thermal ablation of tumour cells with antibody-functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 105, pp. 8697–8702, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.0803557105.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] M. Kakran, L. Li, and R. H. Müller, “Overcoming the challenge of poor drug solubility,” Pharm. Eng., vol. 32, pp. 82–89, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

[64] S. Ghosh, S. Dutta, E. Gomes, et al.., “Increased heating efficiency and selective thermal ablation of malignant tissue with DNA-encased multiwalled carbon nanotubes,” ACS Nano, vol. 3, pp. 2667–2673, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1021/NN900368B/SUPPL_FILE/NN900368B_SI_001.PDF.Suche in Google Scholar

[65] L. Zhu, D. W. Chang, L. Dai, and Y. Hong, “DNA damage induced by multiwalled carbon nanotubes in mouse embryonic stem cells,” Nano Lett., vol. 7, pp. 3592–3597, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl071303v.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] L. Tang, A. Zhang, Y. Mei, Q. Xiao, X. Xu, and W. Wang, “NIR light-triggered chemo-phototherapy by ICG functionalized MWNTs for synergistic tumour-targeted delivery,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 13, p. 2145, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/PHARMACEUTICS13122145.Suche in Google Scholar

[67] L. Yang, T. H. Kim, H. Y. Cho, et al.., “Hybrid graphene-gold nanoparticle-based nucleic acid conjugates for cancer-specific multimodal imaging and combined therapeutics,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 31, p. 2006918, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ADFM.202006918.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] H. Liu, C. Li, Y. Qian, et al.., “Magnetic-induced graphene quantum dots for imaging-guided photothermal therapy in the second near-infrared window,” Biomaterials, vol. 232, p. 119700, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOMATERIALS.2019.119700.Suche in Google Scholar

[69] D. Du, K. Wang, Y. Wen, Y. Li, and Y. Y. Li, “Photodynamic graphene quantum dot: reduction condition regulated photoactivity and size dependent efficacy,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 8, pp. 3287–3294, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACSAMI.5B11154/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/AM-2015-11154Y_0010.JPEG.Suche in Google Scholar

[70] Q. Jia, J. Ge, W. Liu, et al.., “Self-assembled carbon dot nanosphere: a robust, near-infrared light-responsive, and vein injectable photosensitizer,” Adv. Healthcare Mater., vol. 6, p. 1601419, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/ADHM.201601419.Suche in Google Scholar