Abstract

Crude tall oil contains many valuable chemicals such as fatty acids and terpenes which can be used for the production of bio-based plastics, adhesives and paints. In addition to the widely used vacuum distillation process, crude tall oil can also be upgraded using supercritical CO2 (scCO2) extraction. However, research on the extraction of crude tall oil with scCO2 is still very limited. The main factors influencing scCO2 extraction are temperature, scCO2 density and the contact time between scCO2 and the feedstock. The influence of temperature and contact time was therefore investigated in this study. Extraction vessels with different volumes and different scCO2 flows were used for this purpose. Increasing the temperature at the same scCO2 density is decisive for increasing the yield. The yield decreases if the contact time is too low, as the scCO2 cannot be fully saturated. GC-MS/FID analysis of the extracts and the residue shows a change in the extract composition over time and an enrichment of fatty acids in the extract and of diterpenoids in the residue.

1 Introduction

Crude tall oil is an important by-product of pulping, however, it is not produced directly during the pulping of softwood. The tall oil soap must be separated from the black liquor obtained through kraft pulping and acidified to produce the crude tall oil fraction. The fraction can be further cleaned and refined for final utilization (Aryan and Kraft 2021; Mäki et al. 2021). In the separation and refining processes, the yield of crude tall oil, made from softwood trees like pine and spruce and sometimes birch, varies greatly in some cases. This can be influenced by the geographical origin as well as the tree type, the freshness as well as the harvesting time of the wood (Aryan and Kraft 2021; Sandermann 1960). Crude tall oil generally consists to a large extent of resin acids, fatty acids as well as neutral and therefore unsaponifiable substances (Kirk and Othmer 1969). Crude tall oil is mainly produced on site at pulp mills. Here it can contribute to the provision of process energy and, with additional refining, to the generation of additional income. However, the global potential for the use of crude tall oil is limited and is estimated at around 2.6 million tons according to a 2017 study. Around 67 % of this potential is currently produced (1.75 million tons), 80 % of which is refined by distillation (1.4 million tons). This means that there is an excess potential of 850.000 tons, which is reduced to 250.000 tons when all existing distillation capacities are utilized (Peters and Stojcheva 2017). The availability of crude tall oil is strongly linked to the development of the market for chemical softwood pulping (Mäki et al. 2021). Another study concludes that a four times higher added value can be achieved for crude tall oil available in the EU, if it is used for the production of chemicals instead of biodiesel. The competition between the use for chemicals and for fuels leads to an increase in the price of the feedstock (Rajendran et al. 2016).

There are four main uses for crude tall oil. Firstly, it is used as a process energy carrier during pulping. It can also be used as a raw material for biodiesel production or as an additive for fossil oil and phosphate extraction. For all material uses, crude tall oil is generally fractionated by means of vacuum distillation (approx. 80 % of crude tall oil) (Peters and Stojcheva 2017). Vacuum distillation typically yields five fractions (Nogueira 1996). In these fractions, the compositions of fatty acids, resin acids, and neutral components vary (Nogueira 1996). An alternative to vacuum distillation could be the extraction of crude tall oil with supercritical CO2 (scCO2). Above the critical point (304.15 K, 7.38 MPa), CO2 enters the supercritical state (Gupta and Shim 2007). In the supercritical state, on the one hand the fluid cannot be separated into a liquid and a gas phase either by an increase in pressure or an increase in temperature (Andrews 1869) and on the other hand, the fluid has a viscosity similar to a gas and the density can reach that of a liquid. The density can be increased by an isothermal increase in pressure or an isobaric reduction in temperature. In addition to temperature, density is a decisive factor for the solvation power (Gupta and Shim 2007). In general, the solvation power of scCO2 is between that of a weakly polar and non-polar solvent (Clifford 1999). Contrary to a liquid solvent, the dependence of solvation power on density is an important property to control the extraction process. Furthermore, after extraction the CO2 passes into the gas phase during depressurisation, can thus be recycled and no solvent needs to be distilled from the extract. Due to these special properties and the low critical temperature, scCO2 is particularly suitable for the extraction of thermolabile and non-polar substances. In comparison to vacuum distillation, the main advantage of scCO2 extraction is the gentle extraction at low temperatures. However, scCO2 extraction requires expensive high-pressure systems, and together with the energy costs for generating the pressure, scCO2 extraction is often only economically viable for high-value applications (Attard et al. 2015; Wang and Weller 2006). Crude tall oil contains many thermolabile substances with high boiling points, and therefore a high vacuum must be used during distillation to prevent polymerization, which also leads to high energy costs (Nogueira 1996). Resin acids and fatty acids have already been successfully extracted from pine bark by using scCO2 (Barbini et al. 2021). This makes scCO2 a promising solvent for the extraction of crude tall oil, as has been shown in previous works (Harvala et al. 1987; Min and Tao 2004). Harvala et al. (1987) observed an increase in the solubility of crude tall oil in scCO2 with an increase in temperature and density. In addition to density and temperature, the design of the extraction plant plays an important role in scCO2 extraction. During scCO2 extraction, the solute is dissolved and then flushed out of the extraction vessel (Verres 1994). The unfilled volume above the feed (headspace volume) has a particular influence on the flushing out of the extract, as the dissolved extract must flow through this volume (Verres 1994). During the extraction of pyrolysis oil, for example, a faster flushing out of the extract was observed with reduction in vessel volume (Möck et al. 2023). The extraction temperature, the scCO2 density, and the accessibility of the feed have an influence on the dissolution (Clifford 1999). For example, the yield was increased when the accessibility was enlarged by grinding grape seeds (Sovová et al. 1994) and during the extraction of pyrolysis oil, the yield was higher when SiO2 was used as carrier instead of activated carbon (Feng and Meier 2017). If the scCO2 flow is too high, full saturation cannot be achieved because the contact time is too short to reach equilibrium. This phenomenon is especially observed in the determination of solubility using the dynamic method (Gupta and Shim 2007). Furthermore, during the extraction of pyrolysis oils, a changing extract composition was observed over the extraction time, depending on the solubility and molecular weight of the substances (Feng and Meier 2017; Montesantos et al. 2020).

This study investigates the influence of various parameters on the scCO2 extraction of crude tall oil. To examine the effect of temperature, the crude tall oil was extracted at 313.15 K and 333.15 K under nearly identical scCO2 densities (724 and 731 kg/m3). To explore the impact of the contact time between tall oil and scCO2, extraction vessels with different volumes and scCO2 flows were used. Furthermore, the extracts were characterized throughout the extraction process with GC-MS/FID.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Crude tall oil was provided by the pulp and paper producer Kemira Oyj (Figure 1) The crude tall oil had a highly viscous and crumbly consistency. It was dark brown in colour and had an unpleasant odour. The water content was determined by Karl Fischer titration to 2.0 wt.% and the density was 1,001 kg/m3 at 293.15 K. CO2 (99.5 %) was obtained from Linde AG in 50 L dip-tube bottles and the CO2 density was taken from literature data (Anwar and Carrol 2016) based on the pressure and temperature.

Crude tall oil produced by Kemira Oyi.

2.2 Supercritical CO2 extraction plant

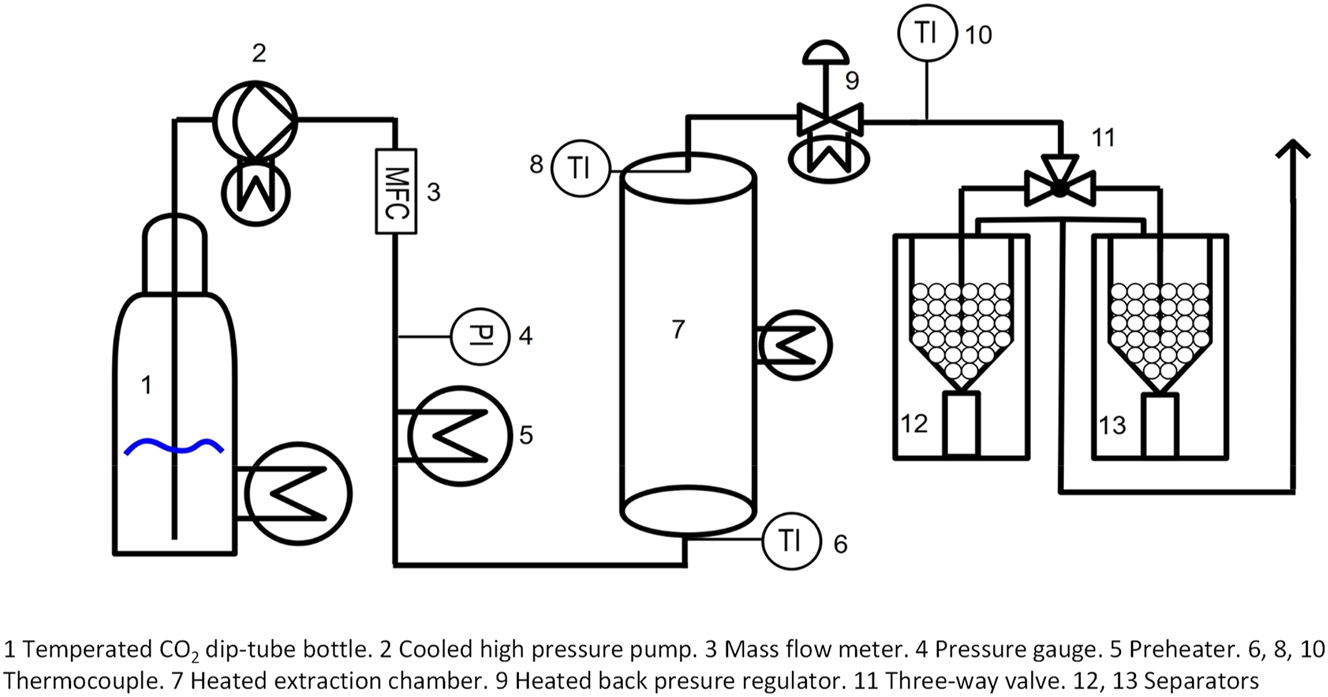

An extraction plant from HDT Sigmar Mothes GmbH was used for the supercritical CO2 extraction of the crude tall oil. The plant has already been used in modified ways for the extraction of pyrolysis liquids (Feng and Meier 2015, 2016, 2017; Möck et al. 2023). A simplified schematic structure is shown in Figure 2 and a more detailed structure is published in another study (Möck et al. 2023).

Flow scheme of scCO2 extraction plant (simplified).

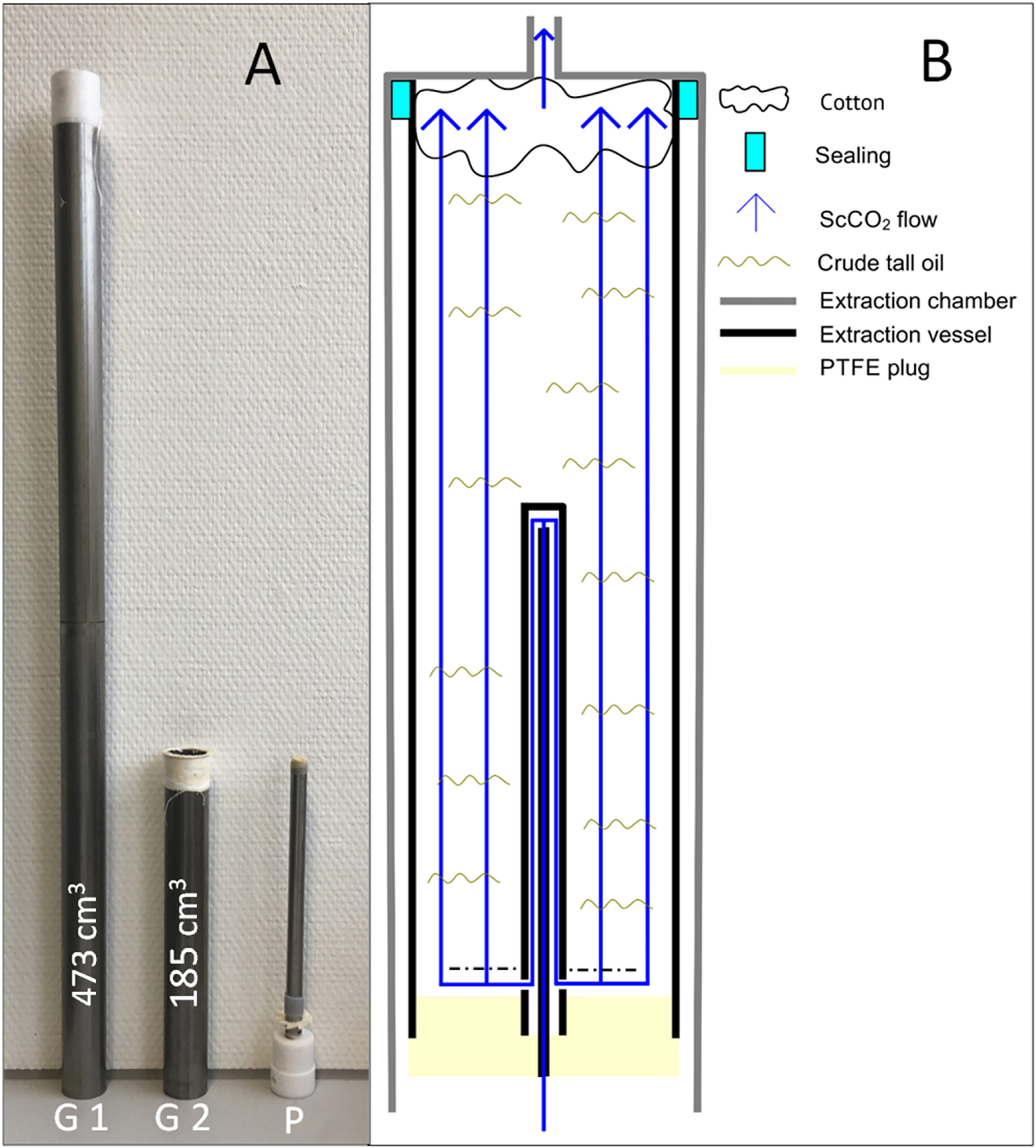

The liquid CO2 was compressed using a high-pressure pump (Figure 2; 2) and supercritical state was reached by heating (Figure 2; 5). The scCO2 flow was measured using a Coriolis mass flow meter (Figure 2; 3) and adjusted via the pump stroke. The scCO2 flowed through the extraction vessels (Figure 3), which were inserted into the heated extraction chamber. Two different extraction vessels (G1 and G2, Figure 3) with different volumes were used. The extraction vessels were inserted so that they were flush with the top of the extraction chamber. The vessels consist of stainless-steel tubes with an inner diameter of 30 mm. The vessels were sealed with a special plug. The plug was made out of PTFE and a stainless-steel tube that redirected the scCO2 into the crude tall oil. The vessels, the plug and the assumed flow of scCO2 through the vessels are shown in Figure 3. Vessel G1 has a volume of 473 cm3 and a length of 710 mm. Vessel G2 has a smaller volume of 185 cm3 and a length of 252 mm.

Extraction vessels and theoretical flow of the scCO2 through the vessels (G1 = vessel G1, G2 = vessel G2, P = plug for redirecting the scCO2).

After filling in the crude tall oil, the upper 2–3 cm of the extraction vessels were stuffed with filter cotton to prevent undissolved tall oil from being discharged and thereby blocking the valve. It is assumed that mixing between scCO2 and tall oil occurs in the entire volume of the extraction vessel due to the scCO2 flow. Thereby, the headspace volume, i.e. the unfilled volume above the tall oil, has an influence on the contact time between scCO2 and crude tall oil. The contact time is also dependent on the density of the scCO2 and the scCO2 flow. The initial contact time at the start of extraction can be calculated using Equation (1). During extraction, the headspace volume increases due to the discharge of extract, which slowly increases the contact time between scCO2 and tall oil.

The scCO2 and dissolved extract were depressurised to atmospheric pressure via a heated backpressure valve (Figure 2; 9). The CO2 was separated from the extract in a separator system consisting of two bottles with an insert filled with 2 mm glass beads and a 22 ml vial. The use of a three-way valve made it possible to switch between the two separators and thus enable a simple sampling during extraction. A more detailed description of the separator system has been described by Möck et al. (2023).

2.3 Supercritical CO2 extraction parameters

Before extraction, the tall oil was homogenised for about 30 min by a rolling board mixer. The extraction of 50 g crude tall oil in the preheated extraction plant was carried out using the two vessels G1 and G2 at two different pressure-temperature combinations. After filling the crude tall oil, the headspace volume, i.e. the unfilled vessel volume above the crude tall oil, was 423 cm3 for vessel G1 and 135 cm3 for vessel G2. The temperatures were 313.15 K and 333.15 K and the pressures (12.5 MPa and 20 MPa) were chosen so that similar scCO2 densities were achieved (724 and 731 kg/m3). The extractions were carried out over 4 h with a CO2 flow of 5 g/min at a solvent to feed ratio of 24 g/g. The resulting contact times between tall oil and scCO2 are 61.3 min at 333.15 K and 61.8 min at 313.15 K for vessel G1. For vessel G2, the contact times were 19.5 min at 333.15 K and 19.8 min at 313.15 K.

In addition, 13.4 g tall oil were extracted with vessel G2 at scCO2 density of 724 kg/m3 (20 MPa, 333.15 K) with a significantly lower contact time of 8.3 min and a much higher solvent to feed ratio of 269 g/g. The CO2 flow was 15 g/min and the extraction time was 4 h. The headspace volume was 172 cm3. In total five extractions were carried out in duplicate and the parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Parameters of crude tall oil scCO2 extraction.

| Extraction | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel | G1 | G1 | G2 | G2 | G2 |

| Vessel volume (cm3) | 473 | 473 | 185 | 185 | 185 |

| Headspace volume (cm3) | 423 | 423 | 135 | 135 | 172 |

| Contact time (min) | 61.3 | 61.8 | 19.5 | 19.8 | 8.3 |

| Pressure (MPa) | 20 | 12.5 | 20 | 12.5 | 20 |

| Temperature (K) | 333.15 | 313.15 | 333.15 | 313.15 | 333.15 |

| ScCO2 density (kg/m3) | 724 | 731 | 724 | 731 | 724 |

| Amount of feed (g) | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 13.4 |

| Amount of CO2 (g) | 1,200 | 1,200 | 1,200 | 1,200 | 3,600 |

| CO2 flow (g/min) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 15 |

| Solvent to feed ratio (g/g) | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 269 |

| Extraction time (h) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

2.4 Calculation of the yield, losses and vapor phase loading

A VWR LPW-2103i scale was used for weighing. The residue was determined by weighing the extraction vessel before and after extraction. The amount of extracts collected was determined by weighing the bottle in the separator system, including the insert filled with glass beads. The yield was calculated according to Equation (2).

The vapour phase loading (VPL) indicates how much extract was extracted from the feed with one kg of CO2. The VPL was calculated according to Equation (3).

2.5 GC-MS/FID

The crude tall oil, the extracts and the residues were characterised by GC-MS/FID. In order to measure the fatty acid content, the samples were methylated online with trimethylsulfonium hydroxide (TMSH). Approximately 15 μl of sample was mixed with dichloromethane to obtain a concentration of 2.5 mg/ml. To 1 ml of this solution 100 μl of a mixture of acetone and fluoranthene (2,000 mg/ml) and 100 μl of TMSH was added. The samples were analysed using an Agilent 6890 GC equipped with an MS 7959 C detector (MSD), FID, and a VF 5-ms column. The exact parameters are given in Table 2.

GC-MS/FID parameters.

| GC system | Agilent 6890 with MS (5975 C)/FID |

|---|---|

| Column | VF 5-ms, 60 m, 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm |

| Injection temperature | 573.15 K |

| Start temperature | 328.15 K for 4 min |

| Heating rate 1 | 3 K/min till 478.15 K |

| Isothermal heating | 13 min at 478.15 K |

| Heating rate 2 | 3 K/min till 598.15 K |

| Split | 15:1 |

| FID | |

| H2 flow | 40 ml/min |

| Synthetic air flow | 450 ml/min |

| N2 flow | 45 ml/min |

| Temperature | 553.15 K |

| Sampling rate | 20 Hz |

| MSD | |

| Ionisation | EI, 70 eV |

| m/z range | 19–550 |

| Transfer line | 553.15 K |

The evaluation was carried out using Massfinder 4 and NIST. The FID signal was used for quantification. The response factors of α-pinene, camphene, δ-3-carene, palmitic acid, linoleic acid, oleic acid and stearic acid were calibrated against standards. The response factor of the remaining substances was estimated based on the substance group. The amounts of methylated substances were back calculated to the unmethylated state. A chromatogram of the tall oil with the identified peaks is included in the Supplementary material.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 GC-MS/FID characterisation of the crude tall oil

The crude tall oil consists mainly of diterpenoids (70.5 wt.%) and fatty acids (25.0 wt.%). The fatty acids consist of oleic acid (8.9 wt.%), linoleic acid (8.2 wt.%) palmitic acid (2.1 wt.%), stearic acid (0.5 wt.%), behenic acid (0.5 wt.%) and small amounts of lignoceric acid (0.3 wt.%). In addition, five fatty acids (4.6 wt.%) are detected, but they could not be clearly identified. The diterpenoids consist mainly of abietic acid (30.6 wt.%), dehydroabietic acid (11.4 wt.%), palustric acid (8.6 wt.%), neoabietic acid (7.9 wt.%) and sandaracopimaric acid (6.5 wt.%). Furthermore, small amounts of monoterpenes (2.6 wt.%) and benzenes (<0.5 wt.%) are detected in the tall oil. The GC-MS/FID detectable composition of the substances in the crude tall oil is compared with the composition of the residue after extraction in Table 3.

Comparison of the substances contained in the residue with those contained in crude tall oil; extraction with solvent to feed ratio of 269 g/g crude tall oil [333.15 K; vessel G2 (V = 185 cm3, L = 252 mm); qmscCO2 = 15 g/min; 13.4 g crude tall oil], bold values = proportion of a substance group.

| RT (min) | Compounds | Crude tall oil | Residue |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% (range) | wt.% (range) | ||

| Fatty acids | 20.4 (0.63) | 14.3 (0.36) | |

| 59.91 | Palmitic acid | 2.1 (0.03) | 1.7 (0.03) |

| 68.25 | Linoleic acid | 8.2 (0.29) | 5.4 (0.19) |

| 68.86 | Oleic acid | 8.9 (0.29) | 6.3 (0.20) |

| 70.37 | Stearic acid | 0.5 (0.02) | <0.1 (<0.01) |

| 88.31 | Behenic acid | 0.5 (0.00) | 0.5 (0.04) |

| 94.243 | Lignoceric acid | 0.3 (0.01) | 0.3 (0.02) |

|

|

|||

| Unknown fatty acids | 4.6 (0.13) | 2.9 (0.07) | |

| 62.99 | Unknown fatty acid 1 | 0.3 (0.02) | <0.1 (<0.01) |

| 67.13 | Unknown unsaturated fatty acid 1 | 1.6 (0.05) | 0.9 (0.03) |

| 69.03 | Unknown unsaturated fatty acid 2 | 0.4 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.01) |

| 74.29 | Unknown unsaturated fatty acid 3 | 1.3 (0.039) | 0.2 (0.02) |

| 78.47 | Unknown unsaturated fatty acid 4 | 1.1 (0.03) | 1.0 (0.03) |

|

|

|||

| Diterpenoids | 70.5 (0.32) | 82.6 (2.99) | |

| 77.01 | Sandaracopimaric acid | 6.5 (0.34) | 7.2 (0.36) |

| 77.87 | Pimara-8 (14),15-dien-18-oic acid | 1.5 (0.04) | 1.6 (0.03) |

| 80 | Isopimaric acid | 3.9 (0.01) | 4.5 (0.27) |

| 80.61 | Palustric acid | 8.6 (0.19) | 9.9 (0.16) |

| 81.61 | Dehydroabietic acid | 11.4 (0.29) | 13.2 (0.32) |

| 83.65 | Abietic acid | 30.6 (0.44) | 36.4 (1.53) |

| 85.45 | Neoabietic acid | 7.9 (0.21) | 9.8 (0.64) |

|

|

|||

| Triterpenes | 0.2 (0.01) | Not detectable | |

| 96.28 | Squalene | 0.2 (0.01) | Not detectable |

|

|

|||

| Sesquiterpenes | <0.1 (0.01) | Not detectable | |

| 44.529 | α-Muurolene | <0.1 (0.01) | Not detectable |

|

|

|||

| Monoterpenes | 2.6 (0.04) | Not detectable | |

| 17.1 | α-Pinene | 1.8 (0.01) | Not detectable |

| 18.03 | Camphene | <0.1 (<0.01) | Not detectable |

| 19.52 | β-Pinene | < 0.1 (<0.01) | Not detectable |

| 21.14 | δ-3-Carene | 0.6 (<0.01) | Not detectable |

| 22.25 | d-Limonene | 0.1 (0.02) | Not detectable |

| 25.21 | Terpinolene | <0.1 (<0.01) | Not detectable |

|

|

|||

| Benzenes | <0.5 | Not detectable | |

| 28.24 | Benzene, 1,2-dihydroxy-(Catechol) | <0.1 (<0.01) | Not detectable |

| 77.11 | trans-3,5-Dihydroxystilbene | 0.2 (0.02) | Not detectable |

|

|

|||

| Total | 98.4 (0.46) | 101.1 (5.32) | |

Nogueira and Pereira (1995) were able to detect 37.5 wt.% fatty acids and 49.4 wt.% resin acids, which mainly consist of diterpenoids, in tall oil. In comparison, in the tall oil used herein, the content of resin acids is lower and the content of fatty acids is higher. Since tall oil is based on a natural product, changes in the composition are normal. The types of trees used, origin, storage and the pulping process all have an influence on the composition (Panda 2013; Sandermann 1960).

3.2 Influence of the temperature and extraction vessel on the yield

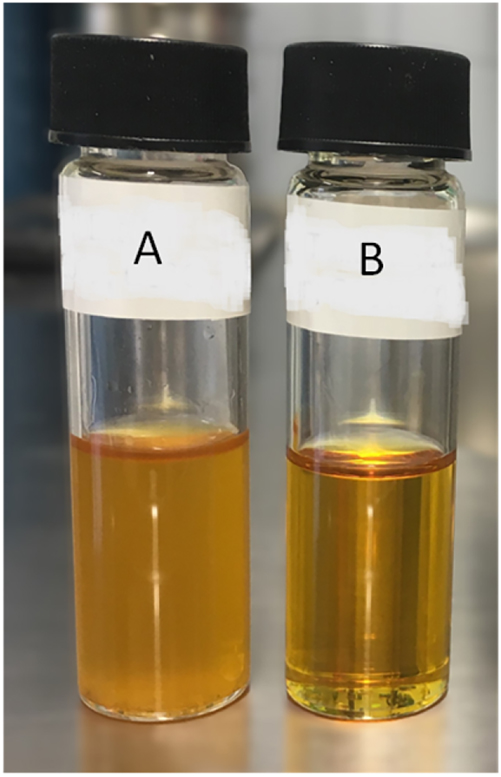

In contrast to the crude tall oil, the extract has a pleasant odour of pine and is cloudy yellow to transparent yellow and has a much lower viscosity, similar to that of rapeseed oil. The cloudy colouration of the extract did not occur in all samples and disappeared towards the end of the extraction time. Figure 4 shows two tall oil scCO2 extracts.

Tall oil scCO2 extracts obtained with vessel G1 at 333.15 K (ρscCO2 = 724 kg/m3; qmscCO2 = 5 g/min; 50 g crude tall oil; 4 h extraction time; A = cloudy yellow extract after 3 h, B = transparent yellow extract after 4 h).

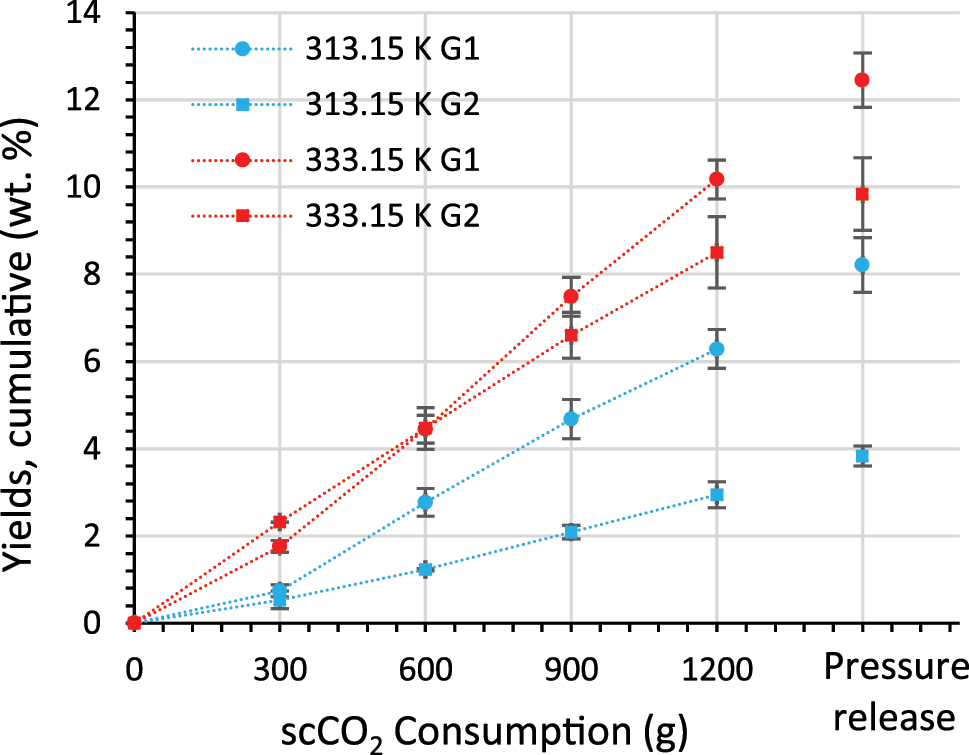

The extraction curves of the extraction of 50 g crude tall oil with vessel G1 and G2 at 313.15 K and 333.15 K are shown in Figure 5.

Extraction curves of the extraction of 50 g crude tall oil with vessel G1 and G2 at 313.15 K and 333.15 K over 4 h at a scCO2 flow of 5 g/min.

Temperature is an important factor in increasing the yield at the same scCO2 density. The highest yield (12.4 wt.%) is achieved at 333.15 K with vessel G1. At 313.15 K, the yield with vessel G1 is 8.2 wt.% and therefore is 4.2 % points lower than at 333.15 K. In addition to the temperature, the extraction vessel used and thus the contact time between scCO2 and crude tall oil also have an influence. This can be seen particularly at the lower temperature of 313.15 K. The yield for vessel G2 (contact time = 19.5 min) at 313.15 K is only 3.8 wt.% and so 4.4 % points lower than for vessel G1 (contact time = 61.3 min). The VPLs of the collected extract are between 5.2 and 1.6 g extract/kg scCO2, with the highest VPL achieved with vessel G1 at 333.15 K and the lowest with vessel G2 at 313.15 K. The VPLs are as follows.

G1, 333.15 K, 20 MPa, 724 kg/m3: 5.2 g extract/kg scCO2

G2, 333.15 K, 20 MPa, 724 kg/m3: 4.1 g extract/kg scCO2

G1, 313.15 K, 12.5 MPa, 731 kg/m3: 3.4 g extract/kg scCO2

G2, 313.15 K, 12.5 MPa, 731 kg/m3: 1.6 g extract/kg scCO2

Harvala et al. (1987) determined the solubility of crude tall oil in scCO2 at 313.15 K and 323.15 K at different densities. The solubility at 313.15 K and 10 MPa (ρscCO2 = 629 kg/m3) was about 0.6 g extract/kg scCO2 and increased to about 3.4 g extract/kg scCO2 at 150 MPa and 313.15 K (ρscCO2 = 780 kg/m3). At 323.15 K the solubility was about 4.8 g extract/kg scCO2 at a pressure of 20 MPa (ρscCO2 = 784 kg/m3). The VPLs determined in this study with vessel G1 are in a similar range to the given values.

Extraction with scCO2 is a combination of dissolving and flushing out the extract (Verres 1994) and if the flow rates are too high, the contact time of the scCO2 is too short to create an equilibrium (Gupta and Shim 2007). Consequently, it is assumed that the contact time between scCO2 and crude tall oil in vessel G2 is not sufficient to create an equilibrium and therefore the VPL/yield is lower than with vessel G1.

The cumulative extraction curves obtained with vessel G1 are almost linear after a scCO2 consumption of 300 g, respectively an extraction time of 60 min, is reached. The extraction curves of vessel G2, on the other hand, are almost linear from the beginning. After the consumption of 300 g scCO2, the yield obtained with vessel G2 at 333.15 K (2.3 wt.%) is even higher than that of vessel G1 at 333.15 K (1.8 wt.%). It is assumed that the lower headspace volume of vessel G2 (135 cm3) leads to faster flushing out of the dissolved extract at the beginning compared to vessel G1. Furthermore, it is assumed that as soon as the scCO2 and crude tall oil are mixed in the higher headspace volume of vessel G1 (423 cm3), the longer contact time provides the higher yields.

During scCO2 extraction of natural substances, there is generally a decrease in yield after an almost linear extraction curve and from that the less accessible or soluble substances are extracted (Sovová 1994). From an economic point of view, it is advisable to continue extraction as long as the yield increases linearly with extraction time (del Valle 2015). Since the extraction curves obtained herein are almost linear, it can be assumed that even higher yields can be achieved if the extraction is continued.

After depressurisation, it was noticed that in the residue a high amount of CO2 is dissolved. This resulted in a negative loss and the formation of bubbles in the residue. A decrease in the weight of the residue over several days was observed.

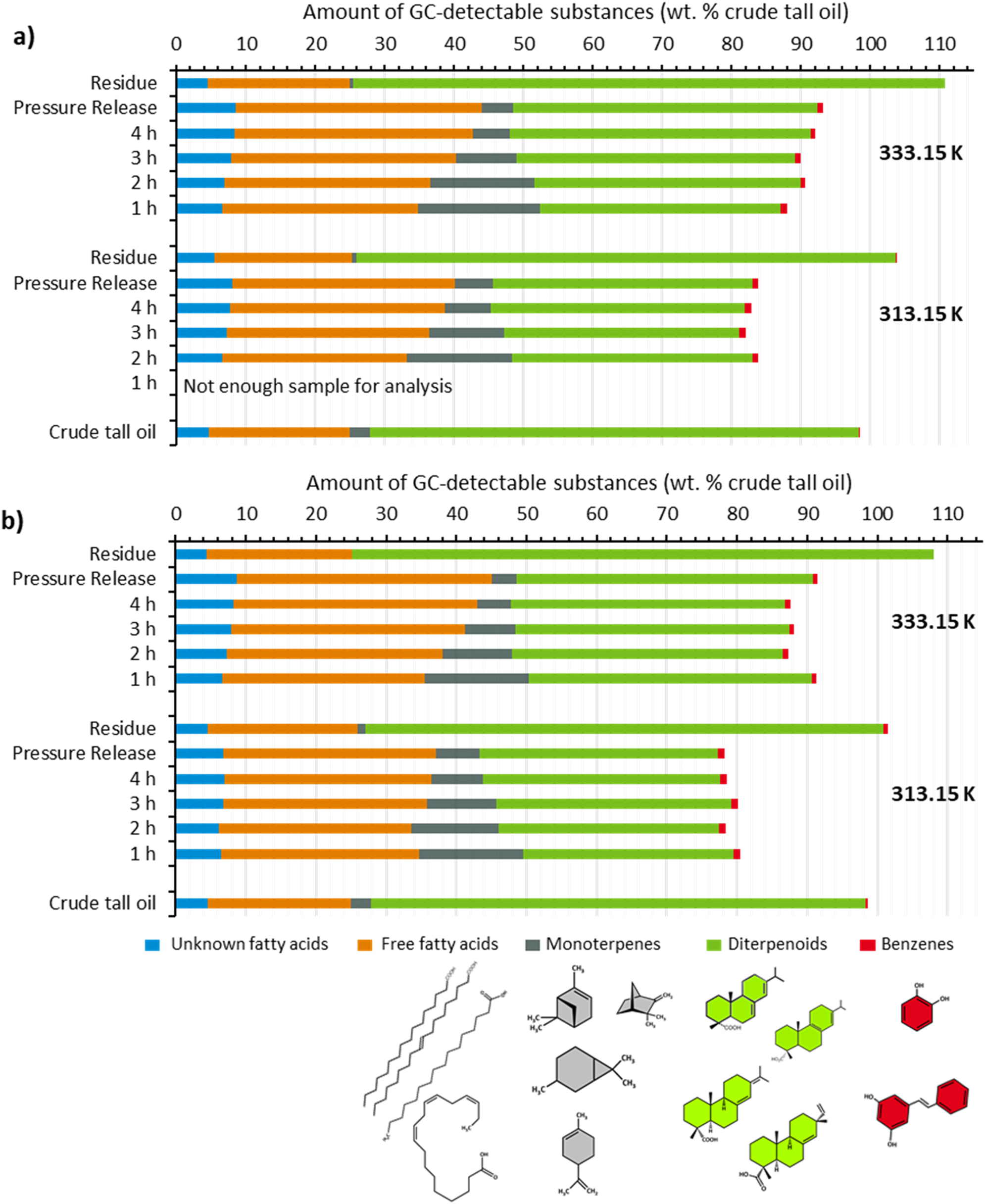

3.3 GC-MS/FID characterization of the extracts

The produced extracts are analysed by GC/MS-FID after an online methylation to evaluate the distribution of different substance classes due scCO2-extraction. Five different substance groups are found in the crude tall oil and the extracts as well: free fatty acids (linoleic acid, oleic acid), high volatile monoterpenes (α-pinen, δ-3-caren), diterpenoids (abietic acid, palustric acid), benzenes and unknown fatty acids (see Figure 6). As shown before, the total yield of different substance groups varies with the influence of temperature and the volume of extraction vessel. In general, the total yield of extractives increases with extraction temperature. The influence of time during extraction is not as pronounced as the influence of extraction temperature. At higher extraction temperature (333.15 K), independent on vessel volume, higher amounts of GC-detectable extractives, especially free fatty acids and diterpenoids are found. At the first sampling after 1 h (333.15 K, vessel G1) an extractive composition showing mainly free fatty acids (28.1 wt.%), diterpenoids (34.7 wt.%) and monoterpenes (17.5 wt.%) is found. Compared to crude tall oil, the proportion of monoterpenes and free fatty acids increases, while the proportion of diterpenoids decrease. These amount decreases from 70.5 wt.% to 34.7 wt.% (333.15 K, vessel G1, 1 h). The composition shifts with increasing extraction time towards a relative increase in the proportion of free fatty acids and diterpenoids. The amount of free fatty acids increases from 28.1 wt.% (1 h) to 34.4 wt.% (4 h) and the amount of diterpenoids from 34.7 wt.% (1 h) to 43.3 wt.% (4 h), respectively (333.15 K, vessel G1). In contrast, the proportions of volatile monoterpenes decrease successively as the extraction time increases. The amounts decrease from 17.5 wt.% after 1 h to 5.3 wt.% after 4 h extraction time (333.15 K, vessel G1). The extracts after the pressure release differ only slightly in composition from the extracts obtained during extraction. The residue found after extraction is again very similar to the crude tall oil with a high proportion of diterpenoids (85.3 wt.%) and lower proportions of free fatty acids (20.4 wt.%) and monoterpenes (0.4 wt.%) (333.15 K, vessel G1). The extraction temperature has only a minor influence on this distribution of the named fractions. Although a reduction in temperature causes a slight decrease in the overall yield of the extracts, the composition does not change essentially.

Depiction of the GC-detectable compounds of crude tall oil fractions after scCO2 extraction at certain sampling times, pressure release and residue in dependence of extraction temperature and extraction vessel: (a) extraction with vessel G1 (V = 473 cm3, L = 710 mm), (b) extraction with vessel G2 (V = 185 cm3, L = 252 mm).

This behaviour can also be observed when using the extraction vessel G2 (see Figure 6b). The composition of the extracts is shifted in favour of free fatty acids and monoterpenes. The proportion of diterpenoids decreases. Furthermore, the behaviour during the extraction time is approximately the same, whereby the proportion of free fatty acids and high volatile monoterpenes also increases in vessel G2 compared to the crude tall oil. The amount of diterpenoids decreases in the same manner. With increasing extraction time, the amount of diterpenoids decreases as well. In contrast to vessel G1, the proportion of diterpenoids does not increase during the extraction time at 333.15 K but remains the same.

In principle, the distribution of extractable substances over the extraction time shows a similar pattern to the extraction of comparable intermediate products from technical wood processing. In comparison, the scCO2 extraction of beech wood slow pyrolysis liquids also produces a characteristic composition of the extracts obtained at different densities or temperatures and extraction times. This also revealed the substance-specific dependence of solubility on scCO2 density. When extracting crude tall oil and pyrolysis oil, it can be seen that the low molecular weight components are extracted first and the proportion of higher molecular weight substances increases as the extraction time increases. In addition, high molecular weight substances or components with a low solubility in scCO2 remain in the residue (Möck et al. 2023). In the case of crude tall oil, the high molecular weight compounds have already been separated off due to further processing during the kraft process and are therefore no longer found during extraction. The occasional overestimation of the substance amounts, which is particularly noticeable in the quantification of residues, may be caused by assumed response factors in the quantification of the individual substances. Small individual deviations can quickly add up to larger deviations and ultimately lead to a content of over 100 wt.%. As no standards are available for many tall oil-specific substances, it is still only possible to work with similar substances with similar retention behaviour.

Compared to vacuum distillation, the scCO2 extraction used in this study does not achieve as distinct a separation into different substance fractions. According to Nogueira (1996), vacuum distillation results in a tall oil fatty acids fraction containing at least 90 wt.% fatty acids. In contrast, the maximum fatty acid content in the scCO2 extracts reaches only 45.0 wt.% (333.15 K, vessel G1, pressure release). In vacuum distillation, different temperatures are used for separation. In the experiments conducted in this study, extraction was performed in a very low scCO2 density range (724–731 kg/m3). To achieve better fractionation, future work will involve the use of separators with varying scCO2 densities, as proposed by Harvala et al. (1987) and applied by Möck et al. (2024) for the fractionation of pyrolysis liquids. Another option for improved fractionation could be multistage extraction using different densities and cosolvents, as demonstrated by Barbini et al. (2021) for the extraction of pine bark.

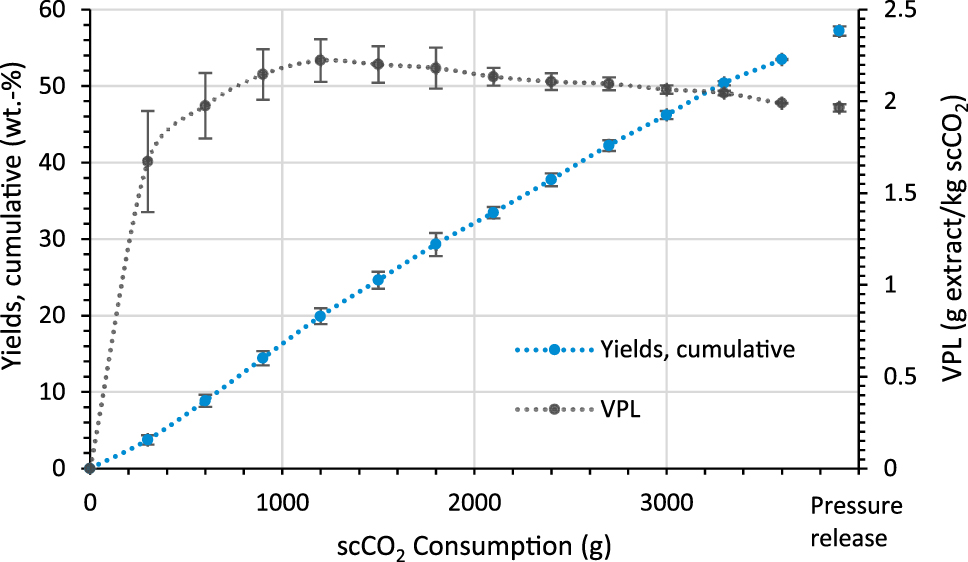

3.4 Maximising the yield by increasing the solvent to feed ratio

In order to find out the maximum amount that can be extracted from the tall oil and at what point the amount of dissolved extract decreases, an extraction with a significantly higher solvent to feed ratio of 269 (g/g) was carried out with vessel G2 at 333.15 K. For this purpose, the amount of tall oil used (13.4 g) was reduced compared to the previous experiments and the CO2 flow was increased to 15 g/min. Figure 7 shows the yields and VPLs of the extraction.

Yield and VPL of an extraction with a solvent to feed ratio of 269 g/g crude tall oil (333.15 K; vessel G2 (V = 185 cm3, L = 252 mm); qmscCO2 = 15 g/min; 13.4 g crude tall oil).

By increasing the solvent to feed ratio, the yield increases up to 57 wt.%. However, the VPLs are between 1.7 g extract/kg scCO2 and 2.2 g extract/kg scCO2 and are thus only about half as high as in the previous experiments using a lower solvent to feed ratio. The VPL increases to 2.2 g extract/kg scCO2 up to a scCO2 consumption of 1.2 kg and then decreases to 2.0 g extract/kg scCO2. The slight decrease in the VPLs suggests that far more extract can be extracted from the crude tall oil before a significant decrease in the extraction curve occurs. By increasing the scCO2 flow to 15 g/min, the contact time is only 8.3 min. In the previous experiment with the same vessel, the contact time was 19.5 min and was thus more than twice as high. Based on the results, it is assumed that the contact time between crude tall oil and scCO2 is crucial for an effective extraction. The residue was analysed by GC-MS/FID to find out which substances are preferentially extracted and which accumulate in the residue. Table 3 compares the substances contained in the residue with those in the crude tall oil.

In comparison, the content of fatty acids (including unknown fatty acids) decreases from 25.0 wt.% in crude tall oil to 17.2 wt.% in the residue. Monoterpenes and benzenes are no longer detectable in the residue. The proportion of diterpenoids in the residue is 82.6 wt.% compared to 70.5 wt.% in crude tall oil. The substance with the highest proportion in the residue is abietic acid, at 36.4 wt.%. In crude tall oil, abietic acid accounts for 30.6 wt.%. Consequently, there is a slight enrichment of diterpenoids in the residue. In the residue, no monoterpenes are present, as these have significantly higher solubility compared to fatty acids. For instance, α-pinene already has a solubility of 53.5 g/kg scCO2 at a scCO2 density of 358 kg/m3 at 333.15 K (Maheshwari et al. 1992). In contrast, the solubility of oleic acid at 333.15 K and a density of 730 kg/m3 is only 7.6 g/kg scCO2 (Akgün et al. 1999). The higher solubility of monoterpenes thus results in their preferential extraction. For diterpenoids no solubility data could be found. However, as an enrichment occurs in the residue, it can be assumed that their solubility is lower than that of the fatty acids and monoterpenes.

4 Conclusions

Crude tall oil can be successfully separated with scCO2 into different fractions consisting of fatty acids, monoterpenes and diterpenoids. The resulted scCO2 extract had a yellowish colour and a much lower viscosity compared to the dark brown high viscous crude tall oil. In the extractions carried out in this study, the extraction time is, in addition to the extraction temperature, crucial for increasing the yield. For the same scCO2 density, the yield increases both when the extraction temperature is increased and when the extraction time is extended. With a larger headspace volume or a lower scCO2 flow, the contact time can be extended. The dissolved amount of extract per kg scCO2 was roughly doubled in this study by extending the time from 19.8 min to 61.8 min (vessel G2, 313.15 K, 12.5 MPa). Depending on the extraction time, there is a focus on higher volatile components such as free fatty acids and monoterpenes at the beginning of the extractions. As the extraction time increases, the composition of the extracts shifts towards diterpenoids. The majority of the diterpenoids remain in the residue, while the proportions of monoterpenes and free fatty acids are in some cases greatly reduced. Compared to vacuum distillation, the scCO2 extraction used in this study results in a less pronounced separation into different fractions. However, scCO2 extraction is very gentle and can be performed at low temperatures. Moreover, there is great potential for further research and optimizations.

Funding source: Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe e. V. (Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture)

Award Identifier / Grant number: Grant number: 2220HV017C, “BioPlas4Paper”

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe e. V. for the financial support of the research project “BioPlas4Paper”, Kemira Oyj for providing the crude tall oil and Silke Radtke for the technical support.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: ChatGPT 3.5 and DeepL were used to improve language.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This research was funded by the Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe e. V. (Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, grant number: 2220HV017C). The presented data were acquired in the research project “BioPlas4Paper”.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

Akgün, M., Akgün, N.A., and Dinçer, S. (1999). Phase behaviour of essential oil components in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids 15: 117–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-8446(99)00006-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Andrews, T. (1869). On the continuity of the gaseous and liquid states of matter. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 159: 575–590, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1869.0021.Suche in Google Scholar

Anwar, S. and Carrol, J.J. (2016). Carbon dioxide thermodynamic properties handbook, 2nd ed. Scrivener Publishing, Beverly.Suche in Google Scholar

Aryan, V. and Kraft, A. (2021). The crude tall oil value chain: global availability and the influence of regional energy policies. J. Clean. Prod. 280: 124616, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124616.Suche in Google Scholar

Attard, T.M., McElroy, C.R., and Hunt, A.J. (2015). Economic assessment of supercritical CO2 extraction of waxes as part of a maize stover biorefinery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16: 17546–17564, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160817546.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Barbini, S., Jaxel, J., Karlström, K., Rosenau, T., and Potthast, A. (2021). Multistage fractionation of pine bark by liquid and supercritical carbon dioxide. Bioresour. Technol. 341: 125862, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125862.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Clifford, T. (1999). Fundamentals of supercritical fluids. Oxford University Press, Oxford.10.1093/oso/9780198501374.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

del Valle, J.M. (2015). Extraction of natural compounds using supercritical CO2: going from the laboratory to the industrial application. J. Supercrit. Fluids 96: 180–199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2014.10.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Feng, Y. and Meier, D. (2015). Extraction of value-added chemicals from pyrolysis liquids with supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 113: 174–185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2014.12.009.Suche in Google Scholar

Feng, Y. and Meier, D. (2016). Comparison of supercritical CO2, liquid CO2, and solvent extraction of chemicals from a commercial slow pyrolysis liquid of beech wood. Biomass Bioenergy 85: 346–354, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2015.12.027.Suche in Google Scholar

Feng, Y. and Meier, D. (2017). Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of fast pyrolysis oil from softwood. J. Supercrit. Fluids 128: 6–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2017.04.010.Suche in Google Scholar

Gupta, R.B. and Shim, J.-J. (2007). Solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide. CRC Press, Boca Raton.10.1201/9781420005998Suche in Google Scholar

Harvala, T., Alkio, M., and Komppa, V. (1987). Extraction of tall oil with supercritical carbon dioxide. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 65: 386–389.Suche in Google Scholar

Kirk, R.E., and Othmer, D.R. (Eds.) (1969). Encyclopedia of chemical technology, 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.Suche in Google Scholar

Maheshwari, P., Nikolov, Z.L., White, T.M., and Hartel, R. (1992). Solubility of fatty acids in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 69: 1069–1076, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02541039.Suche in Google Scholar

Mäki, E., Saastamoinen, H., Melin, K., Matschegg, D., and Pihkola, H. (2021). Drivers and barriers in retrofitting pulp and paper industry with bioenergy for more efficient production of liquid, solid and gaseous biofuels: a review. Biomass Bioenergy 148: 106036, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2021.106036.Suche in Google Scholar

Min, Z. and Tao, Z. (2004). A study on extraction of tall oil by using supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Nanjing Univ. Nat. Sci. 28: 65–67.Suche in Google Scholar

Möck, D.M.J., Riegert, C., Radtke, S., and Appelt, J. (2023). Process optimization and extraction of acids, syringols, guaiacols, phenols and ketones from beech wood slow pyrolysis liquids with supercritical carbon dioxide at different densities. J. Supercrit. Fluids 199: 105937, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2023.105937.Suche in Google Scholar

Möck, D.M.J., Riegert, C., Radtke, S., and Appelt, J. (2024). Production of phenolic-rich slow pyrolysis liquid extracts by supercritical carbon dioxide fractionation. Holzforschung 78: 657–672, https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2024-0039.Suche in Google Scholar

Montesantos, N., Nielsen, R.P., and Maschietti, M. (2020). Upgrading of nondewatered nondemetallized lignocellulosic biocrude from hydrothermal liquefaction using supercritical carbon dioxide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59: 6141–6153, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.9b06889.Suche in Google Scholar

Nogueira, J.M.F., Pereira, J.L.C., and Sandra, P. (1995). Chromatographic methods for the analysis of crude tall-oil. J.High Resol. Chromatogr 18: 425–432, https://doi.org/10.1002/jhrc.1240180707.Suche in Google Scholar

Nogueira, J.M.F. (1996). Refining and separation of crude tall-oil components. Sep. Sci. Technol. 31: 2307–2316, https://doi.org/10.1080/01496399608001049.Suche in Google Scholar

Panda, H. (2013). Handbook on tall oil rosin production, processing and utilization. Asia Pacific Business Press Inc., Dehli.Suche in Google Scholar

Peters, D. and Stojcheva, V. (2017). Crude tall oil low ILUC risk assessment: comparing global supply and demand. Report. ECOFYS, Available at: https://www.upmbiofuels.com/siteassets/documents/other-publications/ecofys-crude-tall-oil-low-iluc-risk-assessment-report.pdf (Accessed 24 February 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Rajendran, V.K., Breitkreuz, K., Kraft, A., Maga, D., and Font-Brucart, M. (2016). Analysis of the European crude tall oil industry: environmental impact, socio-economic value & downstream potential. Final report, Fraunhofer Institute for Environmental, Safety and Energy Technology UMSICHT, Available at: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/eu_cto_added_value_study_fin_0.pdf (Accessed 24 February 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Sandermann, W. (1960). Naturharze, Terpentinöl, Tallöl: Chemie und Technologie. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.10.1007/978-3-662-30448-8Suche in Google Scholar

Sovová, H., Kučera, J., and Jež, J. (1994). Rate of the vegetable oil extraction with supercritical CO2 – II. Extraction of grape oil. Chem. Eng. Sci. 49: 415–420, https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2509(94)87013-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Sovová, H. (1994). Rate of the vegetable oil extraction with supercritical CO2 – I. Modelling of extraction curves. Chem. Eng. Sci. 49: 409–414, https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2509(94)87012-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Verres, T. (1994). Sample preparation by supercritical fluid extraction for quantification. A model based on the diffusion-layer theory for determination of extraction time. J. Chromatogr. A 668: 285–291, https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9673(94)80117-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Wang, L. and Weller, C.L. (2006). Recent advances in extraction of nutraceuticals from plants. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 17: 300–312, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2005.12.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2024-0126).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The 17th European Workshop on Lignocellulosics and Pulp (EWLP) in Turku/Åbo, Finland (August 26–30, 2024)

- Wood Chemistry

- Exploring the potential of ammoxidation of lignins to enhance amide-nitrogen for wood-based peat alternatives and its impact on plant development

- Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of crude tall oil: an alternative upgrading approach

- Wood Technology/Products

- Swelling of cellulose stimulates etherification

- Machine learning-assisted spectrometric method for pulp extractive analysis based on model pulps

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The 17th European Workshop on Lignocellulosics and Pulp (EWLP) in Turku/Åbo, Finland (August 26–30, 2024)

- Wood Chemistry

- Exploring the potential of ammoxidation of lignins to enhance amide-nitrogen for wood-based peat alternatives and its impact on plant development

- Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of crude tall oil: an alternative upgrading approach

- Wood Technology/Products

- Swelling of cellulose stimulates etherification

- Machine learning-assisted spectrometric method for pulp extractive analysis based on model pulps