Abstract

Mental, neurological, and substance use (MNS) disorders pose a significant global health challenge, requiring urgent integration of care into pre-service education (PSE) for medical and nursing students. The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a competency-based framework, supported by the “Enhancing mental health pre-service training with the mhGAP Intervention Guide”, to equip future healthcare providers with essential skills to address MNS conditions effectively. This manuscript outlines the PSE-MNS approach, focusing on defining competencies, developing tailored curricula, and training educators to implement these initiatives. The 2024 Shanghai Workshop convened stakeholders to refine strategies for global dissemination and implementation. Key priorities include stakeholder engagement, leveraging resources such as digital learning tools, and addressing challenges like stigma and limited educational capacity. Facilitators include supportive policies, interdisciplinary collaborations, and existing WHO initiatives. WHO Collaborating Centres (WHOCCs) are instrumental in driving these efforts by promoting partnerships and knowledge exchange. Scaling PSE-MNS programs worldwide is critical for enhancing healthcare quality, fostering equity, and empowering providers to meet the diverse needs of communities. Strategic advocacy, continuous evaluation, and local adaptability will ensure the sustainable integration of MNS care into global health systems.

MNS pre-service education

Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders (MNS) account for one-quarter of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally [1]. The treatment gap for persons with MNS disorders exceeds 50 % in all countries of the world and approaches astoundingly high rates of 90 % in the least resourced countries [2]. The gap widely exists even in the management of severe disorders associated with significant functional impairments and risk of death [2]. This gap needs to be urgently addressed [3]. However, there is a significant shortage of mental health professionals globally, with only 1 % of the global health workforce providing mental health care [3]. The disparity is even more prominent in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) [4], where the number of mental health care workers per 100,000 population is substantially lower compared to higher-income counterparts [2], 5], 6].

Mental health services at the primary care service level are essential in ensuring accessible, affordable, and acceptable services to people with mental health conditions and their families. Despite the accumulated evidence around the need and mechanisms for appropriate inclusion of mental health care as a core element of primary care, it remains a largely unrealized goal in many countries. In addition, the quality and satisfaction with primary mental health care were lower compared to those who received specialized care [7], underpinning the need for countries to diversify care options for comprehensive mental healthcare and scale up capacity building for unspecialized healthcare workers. Bridging this gap necessitates the integration of MNS condition prevention and care into the general responsibilities of healthcare providers, such as general doctors and nurses. The fundamental action for such integration is education and training in mental health among unspecialized healthcare providers. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP), launched in 2010, has adopted in-service training and task-shifting to enhance healthcare professionals’ competencies, building capacities towards and facilitating access to MNS care in over 100 countries [8].

However, a potentially more sustainable and promising approach involves enhancing competency-based education for medical and nursing students before they enter the workforce. Pre-service education (PSE) equips medical and nursing students with the essential capacities to prevent and manage MNS conditions: professional attitudes, knowledge, and skills. This approach is less costly per trainee than in-service training and helps reduce the stigma associated with MNS conditions among healthcare providers [9].

Implementation of PSE-MNS

Recognizing the critical role of PSE for MNS conditions, WHO engaged global stakeholders at its Geneva headquarters in 2018 and published the Enhancing mental health pre-service training with the mhGAP Intervention Guide in 2022 [8], 10]. This guide was developed through a systematic, multi-step process incorporating expert consultations and literature reviews to ensure its relevance and applicability worldwide.

In March 2024, the WHO co-hosted a two-day workshop with the Shanghai Mental Health Center (SMHC), a WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health, to engage stakeholders to review the WHO’s progress in developing the PSE-MNS guide and consider strategies for its worldwide dissemination and implementation. The workshop aimed to yield several objectives, including: a) to update stakeholders on the WHO’s initiative to develop a practical guide to strengthen pre-service competency-based education for doctors and nurses to provide MNS services; b) to share high-level feedback on the latest draft of the PSE-MNS guide, ensuring that it incorporates diverse perspectives and expertise; c) to discuss critical approaches and needs for bolstering PSE-MNS globally, highlighting strategies for effective implementation; d) to devise initial plans for the dissemination and implementation of the PSE-MNS guide, identifying potential partners and locations for field testing and outlining methods and approaches to ensure the guide’s practical applicability and effectiveness across various contexts.

Scope of implementing PSE-MNS

The successful implementation of PSE-MNS necessitates a multifaceted process.

At stakeholder and institutional levels, a competency-based MNS care programme should be integrated into the PSE of medical and nursing students, and key learning objectives for MNS care should be explicitly defined and incorporated with existing curricula, or new curricula could be developed if necessary. The PSE-MNS targets general medical and nursing students, who comprise the bulk of the healthcare workforce in most countries and are often the first points of contact for individuals seeking mental health care [5], [6], [7]. It focuses on a subset of MNS conditions commonly encountered in general healthcare settings, has significant public health importance, and is associated with substantial economic costs and human rights issues.

Four key phases are identified in this collaboration center meeting to promote competencies for MNS care in preservice education. Start with preparation and planning for change, the first phase lays the groundwork for curricular modification by emphasizing the importance of a thorough preparatory process. Initially, a multidisciplinary Curriculum Review Committee (CRC) comprising representing educators, policymakers, students, and individuals with lived experiences of MNS conditions was established. The CRC’s role is to facilitate stakeholder participation, build support, and scrutinize the curriculum change process. A comprehensive situation analysis follows, gathering data on existing curricula, resources, institutional contexts, and external factors such as national health needs and existing MNS services. This analysis identifies gaps and opportunities for integrating MNS care into PSE. Advocacy and stakeholder engagement are critical in this phase, aiming to build awareness, secure support, and mobilize resources. Finally, a detailed work and budget plan outlines specific goals, timelines, roles, responsibilities, and necessary resources for implementing the curriculum changes.

The second phase is defining competencies for MNS care, where the focus shifts to identifying and detailing the competencies required for effective MNS care. This phase begins by determining the specific MNS care tasks that doctors and nurses need to perform, such as assessment, management, and referral of MNS cases. Core competencies are then defined, encompassing the necessary attitudes, knowledge, and skills. The PSE-MNS guide identifies 12 core competencies, including foundational helping skills, rights-based care, emergency response, assessment, management, psychosocial support, and self-care. Additionally, the curriculum content is tailored to local contexts, considering local healthcare needs, cultural factors, and available resources. This ensures the competencies and associated training are relevant and applicable in various settings, facilitating the development of a curriculum that is both context-sensitive and comprehensive.

Developing the curriculum takes place on the third phase and involves the formulation of the enhanced curriculum. This process starts with setting clear and measurable learning objectives aligned with the identified competencies, guiding the structure and content of the curriculum. The curriculum content is then organized in a logical sequence to facilitate progressive learning, integrating MNS-related topics across various courses and modules. Planning learning experiences and teaching methods follow with interactive and practical experiences such as simulations, role-plays, and clinical placements. These methods are designed to help students develop the necessary skills through hands-on practice. Finally, diverse assessment methods are selected to evaluate students’ competencies, varying from written exams, practical demonstrations, and reflective assignments, to ensure a holistic assessment of students’ abilities to provide MNS care.

Finally, the enhanced curriculum is deployed, and continuous improvement is warranted. This begins with training educators to ensure they are well-prepared to deliver the enhanced curriculum, providing them with the necessary training and resources on MNS care and effective teaching methods. The enhanced curriculum is then piloted to test its effectiveness and feasibility, with feedback from the pilot phase used to make necessary adjustments before full-scale implementation. Continuous monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are established to collect data on student performance, educator feedback, and health outcomes. This ongoing evaluation assesses the impact of the curriculum and identifies areas for improvement, allowing for regular updates to address the most evolving needs of students and the health system.

Facilitators and barriers to implementation

Implementing curricular change to integrate competencies for preventing and managing MNS conditions into medical and nursing education involves navigating various barriers [11] and leveraging enabling factors. Common obstacles include time and resource constraints, resistance to change, bureaucracy, and lack of learning resources and technologies. Conversely, supportive policies, increasing political will, and the availability of learning resources are crucial facilitators. Table 1 lists the key facilitators and barriers to implementing PSE for MNS, which were identified at the workshop.

Facilitators and barriers for the implementation of PSE-MNS.

| Title | Facilitators | Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| Policy |

|

|

| Human resources |

|

|

| Technology |

|

|

| Learning resources |

|

|

| Other |

|

|

-

This table was adopted from the “Pre-service education in mental, brain and behavioural health: scaling up implementation and dissemination workshop–WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health (Shanghai), 2024.”

To address the barriers to implementing the enhanced PSE-MNS curriculum, participants at the Shanghai workshop shared their insights and experiences. Firstly, changing attitudes towards individuals with MNS conditions is a challenging yet critical premise of implementing the PSE-MNS curriculum. Effective strategies include engaging students in social contact methods where they interact with individuals with lived experiences of MNS conditions through research, teaching, and community involvement. This direct interaction can deconstruct stereotypes and reduce stigma.

Research is a crucial frontline for destigmatizing MNS and advocating curricular changes [8], 10]. Conducting situation analyses and feasibility studies can provide concrete data on gaps in care, making a compelling case for policymakers. These practical tips, rooted in real-world experiences, offer a robust framework for integrating MNS capacities into medical and nursing curricula, ultimately aiming to improve the quality of care provided by future healthcare professionals.

Simultaneously, curricular changes should align with transitions in pedagogy. Implementing participatory learning approaches, peer-to-peer learning, and digital technologies can enrich the learning experience. Seizing opportunities for change, such as policy shifts or natural disasters, can open doors for advocating curriculum enhancements. Demonstrating proof of concept through small-scale pilots can provide tangible evidence of the impact of the enhanced curricula, serving as a model for broader implementation [12]. Additionally, educators are encouraged to model positive attitudes, fostering an environment of respect and empathy [9]. For example, participation in WHO’s QualityRights training [13], [14], [15] can promote respectful attitudes towards individuals with MNS conditions. Working with traditional healers to address cultural perspectives on mental health can further enhance the cultural sensitivity of the curriculum. Implementing these strategies can significantly influence the attitudes of future healthcare providers, ensuring they are equipped to offer compassionate and effective care.

Secondly, a changing mindset alone does not suffice for implementation, and the critical components lie in mobilizing influencers by identifying key decision-makers and advocating for their support, such as the medical education committee and national health services. Aligning key messages with national priorities can provide motivation and secure the necessary backing for curriculum changes.

Engaging a broad spectrum of stakeholders also lays the foundations for successful curriculum implementation [16]. Key stakeholders include students, academic associations, accrediting organizations, and individuals with lived experience. Meanwhile, an interdisciplinary teams of collaborators from various professional backgrounds [17], including specialists in medicine, public health, policy and social work ensures comprehensive curriculum delivery and balances the teaching load on individual educators. Moreover, utilizing regional bodies such as professional unions to advocate for curricular changes can further strengthen these efforts. Creating demand among students and faculty is another vital approach. To encourage participation, educators can be incentivized through training opportunities and continuing professional education (CPE) credits [16], 18]. Besides, raising awareness of MNS conditions through university events and student associations and employing both top-down and bottom-up strategies can foster a supportive environment for curriculum enhancement. For example, influencing exam boards to include more MNS content in assessments can drive students to seek more knowledge in this area.

Leveraging existing initiatives such as mhGAP for the current workforce can reduce the resistance and create demand for enhanced curricula among educators and healthcare professionals through in-service training. Integrating MNS content into existing courses through case studies, simulations, and short modules can significantly impact the entire curricula without overhauling them. Shifting internships from psychiatric hospitals to general hospitals and incorporating relevant case examples can also enhance practical training. Additionally, harnessing community resources [19] by involving individuals with lived experience [20] as co-educators and mentors can also provide students with valuable perspectives and practical learning experiences.

Promotion and scale-up of PSE-MNS

The success of the PSE-MNS programme in supporting curricular change hinges on its widespread dissemination and uptake. Effective publicizing strategies are essential to ensure the guide reaches a broad audience. Still, the real challenge lies in fostering adoption across diverse educational institutions with varying readiness levels for change. Even if one university successfully enhances its curriculum for MNS conditions, scaling this success to entire countries or regions requires a strategic approach. The participants of the Shanghai Workshop pinpointed various priorities for dissemination and scale-up. By strategically advocating for stakeholder engagement and systematically collecting and presenting evidence, the PSE-MNS guide can be effectively disseminated and scaled up, fostering curricular changes that enhance the competencies of medical and nursing students in providing MNS care.

Advocating for stakeholder engagement

On the one hand, engaging stakeholders is crucial for securing buy-in for curricular change. Identifying stakeholders, understanding their interests and influence, and involving them in the process are essential steps. Key decision-makers, such as accrediting, licensing, and regulating bodies, play a pivotal role in mandating the inclusion of MNS care in first-degree curricula, thus facilitating the process of curricular change. A few effective advocacy and engagement strategies were also proposed, including lobbying and briefings, workshops and seminars, surveys (gathering feedback from educators and students to understand their priorities and needs), and student engagement (creating student clubs, forums, and awareness-raising events to build the atmosphere for change in the student body) [21].

Advocacy efforts should prioritize government stakeholders in countries with centralized curricula. For instance, in response to the growing burden of MNS conditions over the past decade [22], China has implemented initiatives to integrate mental health support within its education system. A notable example is the Three-Tiered Psychological Support System (TTPSS) developed in Shanghai, which adopts a comprehensive approach based on the Biopsychosocial Model and the Tertiary Disease Prevention Model to address mental health needs at multiple levels. This system played a crucial role during the COVID-19 pandemic, supporting MNS care alongside the Education System Epidemic Prevention Alliance – a collaborative effort between educators and mental health professionals. The Alliance provided timely mental health resources for students across elementary, junior and senior high school [23], exemplifying China’s strategic approach to ensuring mental health support in educational settings. Conversely, engaging university administrators and organizations that unite educational institutions and medical associations is more critical in countries where universities have autonomy over curricula. Change can be driven from the bottom up by students and faculty or from the top down by ministries and accreditation bodies. Local and national organizations, including community organizations and WHO Collaborating Centres (WHOCCs), can also play a significant role in stakeholder engagement. In countries utilizing mhGAP for in-service training, this program can be leveraged to disseminate information about the PSE-MNS guide among working doctors and nurses, thereby building buy-in.

Evidence collection and presentation

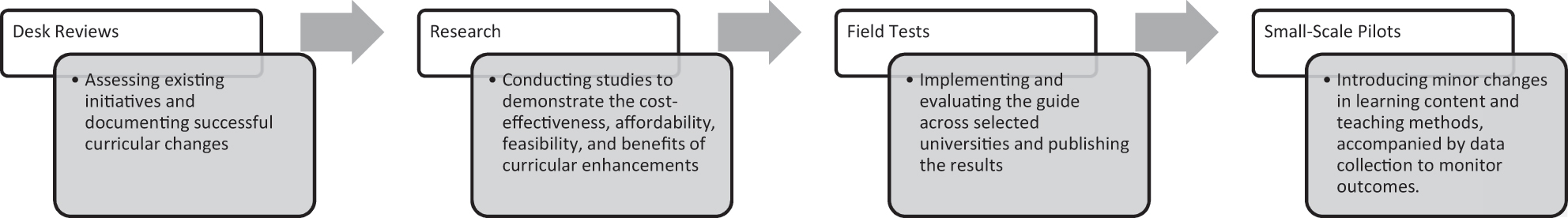

Evidence collection and presentation convince national decision-makers and university staff of the value of investing in curricular change with robust evidence. This evidence can be gathered through the four-stage process (Figure 1) [24]. Documenting actions, monitoring and evaluating results, and sharing experiences through journals and symposiums are critical for knowledge exchange and building a case for curricular change. This evidence-based approach helps illustrate what works, where, and how, thus facilitating broader adoption and implementation of the PSE-MNS guide.

Steps for evidence collection of implementation of pre-service education-mental, neurological, and substance use (PSE-MNS).

Next steps: recommendation for dissemination and scaling up

The Shanghai workshop agreed that successfully implementing the guide requires strategic advocacy, stakeholder engagement, and evidence-based approaches to overcome barriers and facilitate widespread adoption (Table 2 and Supplemental material). By strengthening the MNS knowledge and skills of future healthcare providers, this initiative aims to improve the quality of mental health care globally. Meanwhile, the consensus from the Shanghai workshop underscores the necessity of strategic advocacy, stakeholder engagement, and evidence-based methodologies to overcome implementation barriers and facilitate widespread adoption. Additionally, the workshop pinpointed the follow-up strategies and next steps for various stakeholders, from policymakers to individual educators, providing an action plan for further collaboration with the WHO and stronger synergy among all stakeholders on PSE-MNS.

Examples of next steps planned by participants to kick-start the implementation of the pre-service education-mental, neurological, and substance use (PSE-MNS) guide.

| Country | Next steps |

|---|---|

| Norway | Share the PSE-MNS guide with university faculty who are currently revising the nursing curriculum |

| India | Start working towards developing educational resources around the guide, for example by convening a small focus group to consider what works to change attitudes and how learning resources to support that can be developed |

| Thailand | Set up a group of interested stakeholders and agree on small but immediate changes to the curriculum with a view to trialling these with the next intake of medical students |

| Zambia | Try new methods of teaching, including flipped classrooms, and gather data to build evidence for engaging with stakeholders |

| Fiji | Share the PSE-MNS guide with programme owners of nursing curricula to discuss how it can be used to inform the 2025 curriculum review |

-

This table was adopted from the “Pre-service education in mental, brain and behavioural health: scaling up implementation and dissemination workshop–WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health (Shanghai), 2024.”

Decision and policy makers

For policy and decision-makers, the next steps involve advocacy and resource mobilization. On the one hand, policy briefs, slide decks, and other communication materials should be created to raise awareness and understanding of the MNS care in public discourse [17], 25]. Such efforts may further facilitate a more targeted advocacy and rationalize meetings and briefings with high-level decision-makers in universities and ministries of health and education, emphasizing the importance of including MNS competencies in PSE. On the other hand, relevant resources and funding should be mobilized. Funding opportunities to support the development and implementation of the enhanced curriculum should be identified. This includes leveraging existing resources and seeking new funding avenues where possible [19]. Meanwhile, foster consensus among key stakeholders, including accrediting, licensing, and regulatory bodies, to mandate the inclusion of MNS care in medical and nursing curricula [12], 18], 19], 25]. Engaging community organizations, universities, and professional associations in these efforts will accelerate the process.

Additionally, policy and decision-making requires the establishment of monitoring systems where continuous feedback and improvement will be provided during curricular change. It is also necessary to develop robust monitoring and evaluation frameworks to assess the impact of curriculum changes, track implementation indicators, and gather feedback to drive continuous improvement. Concurrently, encouraging institutions to document their experiences and share best practices through publications and symposiums can facilitate knowledge exchange and promote broader adoption [12], 19]. Such an appropriate monitoring mechanism will boost the confidence among the key stakeholders and the public.

Health professional and educators

The following steps for health professionals and educators in disseminating and implementing the PSE-MNS guidelines involve several strategic actions. First, educators should integrate the guidelines into existing curricula by adapting learning objectives, content, teaching methods, and assessment strategies to incorporate competencies relevant to MNS care. This process may include developing and utilizing competency-based frameworks that outline essential attitudes, knowledge, and skills required for MNS care [8], 24]. Additionally, professionals and educators should engage in continuous professional development to enhance their own understanding and teaching capabilities in the domain, which may involve participating in specialized training sessions and workshops.

Collaboration with stakeholders, including academic institutions, healthcare organizations, and community groups, is critical to foster a supportive environment for curriculum enhancement. Educators should also actively participate in advocacy efforts by presenting the importance of MNS education at academic and professional forums, thereby influencing policy and decision-making processes as aforementioned.

Moreover, pilot programs and rigorous evaluations will help identify best practices and areas for improvement [18]. Documenting and sharing successful implementation strategies through publications and conferences will further aid in the broader dissemination and adoption of the guidelines. These concerted efforts will ensure that medical and nursing students are well-equipped to provide competent MNS care, thereby improving healthcare outcomes on a global scale.

WHOCCs and other partners

WHOCCs, including but not limited to the Chinese centre, play a crucial role in advancing PSE for MNS conditions. These centres, working alongside a network of global and regional partners, reinforce educational efforts through shared resources and collaborative strategies. WHOCCs facilitate knowledge exchange, advocate for curriculum integration, and collaborate with both international and domestic stakeholders to support PSE initiatives.

Key contributions by WHOCCs include guiding the adaptation and enhancement of educational content and methodologies to strengthen MNS-focused PSE across different educational systems. This includes stakeholder engagement by collaborating with government entities, including ministries of health and education, and other educational institutions. This strategic involvement aids in developing tailored, competency-based curricula that cater to the unique needs of countries and regions. To sustain these efforts, WHOCCs actively pursue research funding opportunities and facilitate ongoing collaboration through digital platforms, periodic meetings, and publications, fostering a robust network for shared learning and policy development Partnerships may also extend to international organizations like the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations (IFMSA) and the International Council of Nurses (ICN), promoting unified approaches in MNS education. These collaborations ensure that PSE initiatives are aligned with global health standards and incorporate the perspectives of diverse educational, policy-making, and clinical groups [8], 24].

These initiatives are bolstered by WHO’s advocacy efforts, which support stakeholder engagement, funding pursuits, and the maintenance of dynamic networks. The goal is to enhance PSE programs that ensure medical and nursing students acquire the necessary skills and knowledge to address MNS conditions effectively, contributing to better healthcare outcomes globally.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the WHO’s PSE-MNS approach, as outlined in the Enhancing mental health pre-service training with the mhGAP Intervention Guide, provides a comprehensive framework for integrating MNS disorder prevention and care into PSE for medical and nursing students. Successful implementation requires a multifaceted strategy, including defining competencies, developing tailored curricula, training educators, and engaging stakeholders at all levels. The 2024 Shanghai Workshop convened key stakeholders to refine strategies for worldwide dissemination and implementation, with priorities including strategic advocacy, leveraging digital learning resources, and addressing barriers such as stigma and limited educational capacity.

Scaling up PSE-MNS programs globally is crucial for improving the quality of care, promoting equity, and empowering healthcare providers to meet the diverse needs of communities. WHOCCs play a pivotal role in advancing these efforts by fostering partnerships and knowledge exchange. Through collaborative efforts, strategic advocacy, and evidence-based implementation, the PSE-MNS approach represents a transformative initiative to bridge the global treatment gap for MNS disorders and equip future generations of healthcare professionals with the skills needed to provide compassionate and effective care.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global burden of disease study 2019 (GBD 2019) results. Seattle; 2020. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019 [Accessed 19 Aug 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

2. Chaulagain, A, Pacione, L, Abdulmalik, J, Hughes, P, Oksana, K, Chumak, S, et al.. WHO mental health gap action programme intervention guide (mhGAP-IG): the first pre-service training study. Int J Ment Health Syst 2020;14:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00379-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. World Health Organization. Mental health atlas 2020. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345946 [Accessed 19 Aug 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

4. Petersen, I, Van Rensburg, A, Kigozi, F, Semrau, M, Hanlon, C, Abdulmalik, J, et al.. Scaling up integrated primary mental health in six low- and middle-income countries: obstacles, synergies and implications for systems reform. BJPsych open 2019;5:e69. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Davies, T, Lund, C. Integrating mental health care into primary care systems in low- and middle-income countries: lessons from PRIME and AFFIRM. Glob Ment Health 2017;4:e7. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2017.3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Lund, C, Tomlinson, M, Patel, V. Integration of mental health into primary care in low- and middle-income countries: the PRIME mental healthcare plans. Br J Psychiatry 2016;208:s1–3. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153668.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. World Health Organization. Mental health in primary care: illusion or inclusion? Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.38 [Accessed 19 Aug 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

8. World Health Organization. Enhancing mental health pre-service training with the mhGAP Intervention Guide: experiences and lessons learned. World Health Organization; 2020.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Carleton, RN, Afifi, TO, Turner, S, Taillieu, T, Vaughan, AD, Anderson, GS, et al.. Mental health training, attitudes toward support, and screening positive for mental disorders. Cognit Behav Ther 2020;49:55–73. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/16506073.2019.1575900 [Accessed 21 Jul 2024].10.1080/16506073.2019.1575900Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Iversen, SA, Ogallo, B, Belfer, M, Fung, D, Hoven, CW, Carswell, K, et al.. Enhancing mental health pre-service training with the WHO mhGAP Intervention Guide: experiences learned and the way forward. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health 2021;15:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00354-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Murphy, J, Qureshi, O, Endale, T, Esponda, GM, Pathare, S, Eaton, J, et al.. Barriers and drivers to stakeholder engagement in global mental health projects. Int J Ment Health Syst 2021;15:30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-021-00458-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Wotring, J, Hodges, K, Xue, Y, Forgatch, M. Critical ingredients for improving mental health services: use of outcome data, stakeholder involvement, and evidence-based practices. Behav Ther 2005;28:150–8.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Mion, ABZ, Ventura, CAA. The WHO QualityRights Initiative and its use worldwide: a literature review. Int J Soc Psychiatr 2023;70:424–36. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/00207640231207580 [Accessed 21 Jul 2024].10.1177/00207640231207580Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Moro, MF, Pathare, S, Zinkler, M, Osei, A, Puras, D, Paccial, RC, et al.. The WHO QualityRights initiative: building partnerships among psychiatrists, people with lived experience and other key stakeholders to improve the quality of mental healthcare. Br J Psychiatr 2022;220:49–51. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.147.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. World Health Organization. QualityRights materials for training, guidance and transformation 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-qualityrights-guidance-and-training-tools [Accessed 21 Jul 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

16. Hann, K, Pearson, H, Campbell, D, Sesay, D, Eaton, J. Factors for success in mental health advocacy. Glob Health Action 2015;8:28791. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3402/gha.v8.28791 [Accessed 21 Jul 2024].10.3402/gha.v8.28791Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Lyon, AR, Stirman, SW, Kerns, SEU, Bruns, EJ. Developing the mental health workforce: review and application of training approaches from multiple disciplines. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:238–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0331-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Walker, ER, Zahn, R, Druss, BG. Applying a model of stakeholder engagement to a pragmatic trial for people with mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv 2018;69:1127–30. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ps.201800057 [Accessed 21 Jul 2024].10.1176/appi.ps.201800057Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Duncan, A, Stergiopoulos, V, Dainty, KN, Wodchis, WP, Kirst, M. Community mental health funding, stakeholder engagement and outcomes: a realist synthesis. BMJ Open 2023;13:e063994. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063994.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Booth, A, Scantlebury, A, Hughes-Morley, A, Mitchell, N, Wright, K, Scott, W, et al.. Mental health training programmes for non-mental health trained professionals coming into contact with people with mental ill health: a systematic review of effectiveness. BMC Psychiatr 2017;17:196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1356-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Ressler, MB, Apantenco, C, Wexler, L, King, K. Preservice teachers’ mental health: using student voice to inform pedagogical, programmatic, and curricular change. Action Teach Educ 2022;44:252–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2021.1997832.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Ma, Y, Huang, L, Wang, C, et al.. Burden of mental and substance use disorders – China, 1990−2019. CCDCW 2020;2:804–9.10.46234/ccdcw2020.219Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Ren, D, Wang, L, Pan, X, Bai, Y, Xu, Z. Building a strategic educator–psychiatrist alliance to support the mental health of students during the outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Global Mental Health 2020;7:e32. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2020.27.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health (Shanghai). Pre-service education in mental, brain and behavioural health: scaling up implementation and dissemination. Shanghai, China; 2024.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Murphy, JK. Considerations for supporting meaningful stakeholder engagement in global mental health research. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2022;31:e54. https://doi.org/10.1017/s204579602200035x.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/gme-2024-0023).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.