Abstract

In this paper we analyse Spanish verbal constructions that accept both the clitic se and the prefix auto- in order to determine whether these formations are or are not more agentive than the corresponding non-prefixed constructions (autocriticarse vs. criticarse). The proposal arises from the discussion about the different semantic values observed in formations with auto- and explores the distinctive features of such formations in contrast to those without auto-. We carried out a twofold analysis: first, we applied a set of tests of agentivity and control to a sample of 130 verbs with auto- extracted from the Modern Spanish Reference Corpus (CREA) and compared the sample with its non-prefixed pronominal pairs (i.e. verbs with clitic se). Second, we carried out a series of surveys using similar tests with Spanish speakers to guarantee the acceptability of the corpus interpretations. We argue that prefixed constructions show a higher degree of agentivity and control by external arguments, which results in the impossibility of bidirectionally replacing these constructions with those that only have the clitic se.

1 Introduction

Spanish offers a complex scenario, where a verb can occur with the clitic se by itself, as well as in constructions both with se and the prefix auto-, as examples (1a) and (1b) show:[1]

| a. | El | polvo | se | disuelve | en | el | agua |

| the | powder | se | dissolve.prs.3sg | in | the | water | |

| ‘The powder dissolves in water’ | |||||||

| b. | El | polvo | se | auto-disuelve | en | el | agua |

| the | powder | se | self-dissolve.prs.3sg | in | the | water | |

| ‘The powder dissolves in water’ | |||||||

In addition, there are constructions where se combines with sí solo/a and with sí mismo/a(s) apparently with no difference in meaning from those only with se:

| a. | Ana | se | critica | |||||

| Ana | se | criticize.prs.3sg | ||||||

| ‘Ana criticizes herself’ | ||||||||

| b. | Ana | se | critica | a | sí misma | |||

| Ana | se | criticize.prs.3sg | to | herself | ||||

| ‘Ana criticizes herself’ | ||||||||

| c. | Se | disuelve | por | sí mismo | ||||

| se | dissolve.prs.3sg | by | itself | |||||

| ‘(It) dissolves by itself’ | ||||||||

Furthermore, we find heavily marked constructions with auto- + se + sí mismo/a(s), that coexist with some of the previous constructions:

| a. | Capacidad | para | auto-gobernar=se | |||||

| ability | for | self-govern.inf=se | ||||||

| ‘Ability to self-govern’ | ||||||||

| b. | Capacidad | para | gobernar=se | a | sí mismo | |||

| ability | for | govern.inf=se | to | himself | ||||

| ‘Ability to govern oneself’ | ||||||||

| c. | Capacidad | para | auto-gobernar=se | a | sí mismo | |||

| ability | for | self-govern.inf=se | to | himself | ||||

| ‘Ability to govern oneself’ | ||||||||

Notice that while these are different strategies in Spanish, it is not an easy task to find an exact parallel in the English translation. Lastly, there are also constructions with auto- but without se, as in (4):

| Auto-controla | tu | miedo |

| self-control.imp.2sg | your | fear |

| ‘Self-control your fear’[2] | ||

As is evident, Spanish makes use of a wide range of possible combinations that are not necessarily easy to translate into other languages, and which have not been addressed in a truly comprehensive approach so far.

Traditionally, constructions with auto- have been considered redundant or cases of overlapping. García-Medall Villanueva (1988), for instance, is of the opinion that verbal formations with auto- and the clitic se are a kind of double reflexive marking phenomenon so he rejects constructions with both the prepositional phrase a sí mismo/a(s) and the prefix, as in autocriticarse a sí mismo ‘to criticise oneself’. However, the coexistence of different constructions suggests that we still need a better understanding of their semantics and the exact relation between each of these constructions and reflexivity.

In this paper, therefore, and contrary to the explanation based on notions of redundancy or overlapping, we try to determine the exclusive and differential semantic contribution of auto- to verbal constructions with se (and all the corresponding person/number forms within the flexive paradigm: me, te, se, nos, os), and try to explain the difference between se constructions with and without the prefix. Our starting hypotheses are that, first, these strategies (pronominalization and prefixation) are not always interchangeable and do not result in necessarily identical values;[3] and second, constructions with auto- must be higher on the agentivity scale than those without it, as already pointed out by Felíu (2005). In this sense, agentivity would be a necessary semantic condition for the syntactic restrictions of reflexivity in Spanish.

2 Theoretical background and referential framework

2.1 An overview of formations with auto- and with se

Traditionally, the (neo)classical origin of auto- has led to its morphological classification as a ‘prefixoid’ (Lang 1990), as it occurs in terms like autonomía ‘autonomy’. At the same time, it is a highly productive derivative prefix (Felíu 2003a, 2003b) that can be applied to lexical items belonging to all major word classes: verbal constructions, such as autoprogramarse ‘to program oneself’; nominal constructions, such as autopercepción ‘self-perception’ and autogol ‘own goal’; adjectival constructions, such as autolimitado ‘self-limited’ and autoadhesivo ‘self-adhesive’; and even adverbial constructions, such as autorreflexivamente ‘self-reflexively’, which stem from adjectival formations in -do/a (Felíu 2003a, 2003b; Orqueda and Squadrito 2017). These must be differentiated from the lexeme (Varela Ortega 2005) that occurs in, e.g. autismo ‘autism’ and the cases of composition that arise through shortening from automóvil ‘automobile’, such as autovía ‘highway’.

From a syntactic point of view, scholars do not always agree on whether this morphological process is capable of modifying the argumental structure. Thus, according to RAE and ASALE (2010: 176), auto- as well as entre- and co- are prefixes of argumental incidence and allow the emergence of new constructions with syntactic and valence constraints that may be different from those in the base. In turn, studies such as Felíu (2003a, 2003b) argue that these prefixes do not alter the valency of the base but instead establish a coreference relation between two arguments (semantic level).

From a functional point of view, the divergent characterization of these new formations – as a consequence of the values of the prefix mentioned above – has been extensively discussed in the literature, not only in Spanish (Felíu 2003a, 2005; Mendikoetxea 1999, among others; RAE and ASALE 2010) but also in other Romance languages such as Italian and French (Mutz 2003, 2011). However, scholars do not agree about the precise number and functionality of these formations. Thus, for example, some authors acknowledge only the reflexive formations (Varela Ortega 2005), as in (5), with certain syntactic constraints such as coreference and the information provided regarding the valency and the argumental structure:

| Ana | se | auto-critica |

| Ana | se | self-criticize.prs.3sg |

| ‘Ana criticizes herself’ | ||

Following Van Valin’s proposal (2001) on macroroles, a reflexive verb construction with both auto- and the clitic se (for example, autocriticarse ‘to criticize oneself’ or autorretratarse ‘to portray oneself’) is a case of coreference between the Actor and the Undergoer.[4] In other words, these are cases of coreference between the external (Xi) and internal (Yi) arguments [Xi, Yi], where X and Y are two different but coreferential arguments. The reflexive use of auto- may indeed be reformulated with the verb + se + a sí mismo/a(s), as was seen in (2b). However, claiming that the reflexive is the only meaning expressed by [auto- + V + se] constructions would lead us to discard forms such as autoemocionarse ‘to get emotional oneself’, in which a distinction between Actor and Undergoer cannot be made. The problem is that even though constructions like autoemocionarse ‘to get emotional oneself’ or autodisolverse ‘self-dissolve’ are not as frequent as emocionarse or disolverse, they are still in use and widespread in the different Spanish dialects.

Within the range of non-reflexive constructions, auto- may also indicate reciprocity with a plural subject, as in (6a) below, which is confirmed by the possibility of rephrasing it with mutuamente ‘mutually’, as in (6b):

| a. | Los | compañeros | se | auto-estimulan | entre | ellos | ||

| the | classmates | se | self-stimulate.prs.3pl | between | them | |||

| ‘The classmates stimulate each other’[5] | ||||||||

| b. | Se | estimulan | mutuamente | |||||

| se | stimulate.prs.3pl | mutually | ||||||

| ‘(They) stimulate each other’ | ||||||||

Yet other proposals point to the polyfunctional character of the prefix (e.g. Felíu 2005; Mendikoetxea 1999) and underline, in particular, the ability of the prefix to indicate the absence of a cause or external force, as was seen in (1b), and also as in (7) below:

| a. | El | papel mural | se | auto-adhiere |

| the | wallpaper | se | self-adhere.prs.3sg | |

| ‘The wallpaper is self-adhesive’ | ||||

| b. | Este | metal | se | auto-degrada |

| this | metal | se | self-degrade.prs.3sg | |

| ‘This metal degrades itself’ | ||||

These examples show that [auto- + V + se] constructions can express an anticausative meaning. It is true, however, that these constructions are more restricted because not all verbal classes may belong to this construction type.

Alternatively, studies such as Lang (1990) make special mention of the intensification nuance and call into question whether the prefix necessarily expresses reflexivity or whether the reflexive meaning already pre-existed in the base to which auto- is added,[6] i.e. whether the semantic condition for the prefix is the reflexive character of the base to which it is attached (RAE and ASALE 2010). As a response to that, Felíu (2003a) argues that it is not entirely correct to suppose that there is a previous reflexive value, especially if nominal constructions that are not necessarily deverbal such as autobiografía ‘autobiography’ are considered. In fact, there are also cases with se that cannot be considered reflexive, neither in the prefixed construction nor in the non-prefixed base, as in (8):

| Cristóbal López | se | auto-controla | los | casinos |

| Cristóbal López | se | self-control.prs.3sg | the | casinos |

| ‘Cristóbal López controls his casinos by himself’ | ||||

In example (8), both a reflexive and an anticausative meaning must be ruled out. Instead, it is a transitive clause where auto- must be an intensifier and se something different.

The fact that the same prefix appears in such different constructions (reflexive, reciprocal, anticausative, and emphatic) is not unusual if we take into account functional typological proposals such as those of Haspelmath (2003), and König et al. (2013), who recognize the varied semantics and functions of reflexive markers.

The apparent overlapping of auto- with other strategies is seen in the fact that both the intensifying and the reflexive functions can also be expressed without the prefix and with the sí mismo strategy. This had led scholars to consider it a possible case of functional overlap, due to the shared anaphoric character, which occurs particularly in nominal formations. As the examples in (9) show, if these clauses are isolated, the construction with auto- must necessarily have a retrievable antecedent – the possessive in the case of (9b) – unless we take autobiografía as a text genre. There is a recoverable referent for auto- in (9b). In contrast, it is unknown whose biography it is in (9a).

| a. | *La | auto-biografía | se | vende | bien | |

| the | auto-biography | se | sell.prs.3sg | well | ||

| *‘The autobiography sells well’ | ||||||

| b. | Sui | auto-biografíai | se | vende | bien | |

| his/her | auto-biography | se | sell.prs.3sg | well | ||

| ‘His/heri autobiographyi sells well’ | ||||||

However, the anaphoric character is not enough to determine the presence of auto-, as was seen in (8). Furthermore, although these are nominal formations, it is worth noting that examples as in (10a) are possible and documented while those as in (10c) are not, especially considering that both destrucción ‘destruction’ and infección ‘infection’ accept the reinforcement with sí mismo, as in (10b) and (10d) respectively:[7]

| a. | Auto-destrucción | de | sí mismo |

| self-desruction | of | himself | |

| ‘Self-detruction of himself’ | |||

| b. | Destrucción | de | sí mismo |

| destruction | of | himself | |

| ‘Destruction of himself’ | |||

| c. | *Auto-infección | de | sí mismo |

| self-infection | of | himself | |

| *‘Self-infection of himself’ | |||

| d. | Infección | de | sí mismo |

| infection | of | himself | |

| ‘Infection of himself’ | |||

This comparison shows that the non-agentive nature of the event’s first argument in autoinfección ‘self-infection’ (and not the possible paraphrasis by sí mismo) could explain the non-existence of examples like (10c).

Concerning the pronoun se (Gómez Torrego 1992; González Vergara 2006; Maldonado 1999; Montes Giraldo 2003),[8] the literature agrees on its multifunctionality. Apart from its use as a reflexive strategy, this complex clitic is also found in a wide range of constructions. Some of them are: reciprocals (ellos se aman ‘they love each other’), impersonals (aquí se vive bien ‘one lives well here’), anticausatives (se abrió la puerta ‘the door opened itself’), and passives (se venden casas ‘houses are sold’). Besides, it is inherent to diverse intransitive and transitive pronominal verbs, like irse ‘to leave’, olvidarse ‘to forget’. Although the range of uses of the Spanish clitic se has expanded throughout the history of this language (e.g. Bogard 2006), its multifunctional nature was inherited from the Latin full pronoun se, which was used in reciprocal, reflexive and anticausative (Cennamo et al. 2015: 684) constructions already in Early and Classical Latin.

Regarding the comparison between [auto + V + se] constructions and [V + se] constructions, several authors propose, as already mentioned, a certain amount of functional similarity (Lang 1990; Mendikoetxea 1999; Varela Ortega 2005). The explanation given is that both processes (prefixing and the use of the se clitic) are used both in the formation of verbs with reflexive interpretation (sacrificarse/autosacrificarse ‘to sacrifice oneself’) and in the formation of anticausatives with absence of external agent (abrirse/autoadherirse ‘to open by itself/to adhere by itself’).

However, in contrast to [auto- + V (+ se)] constructions, which may be cases of intensification, non-prefixed constructions with se (e.g. sacrificarse) cannot be considered intensifiers. This distribution is coherent with the implicative generalization proposed by König and Siemund (2000: 59): “If a language uses the same expression both as an intensifier and as reflexive anaphor, this expression is not used as a marker of derived intransitivity or aspectual marker”. This would suggest that the intensifier marker should be auto-, while se is responsible for the intransitivity derivation. In other words, if the construction López se autocontrola los casinos ‘López controls his own casinos’ has an intensifying nuance, this value is provided by auto-, and not by se, because auto- can be used elsewhere as a reflexive marker but not as an intransitivizer, while se can be an intransitivizer but not an intensifier elsewhere. Following this generalization, it seems natural that in cases in which the subject is an Undergoer, as in (11), the intransitive derivation (anticausativity) is due to se and, consequently, the auto- prefix indicates something different:

| Este | mensaje | se | auto-destruirá | en | cinco | segundos |

| this | message | se | self-destruct.fut.3sg | in | five | seconds |

| ‘This message will self-destruct in five seconds’ | ||||||

Note that, within a narrow definition, it is impossible to assign a reflexive interpretation to (11), because it is a case of external argument reduction. These formations are very complex, so ambiguous readings or specific interferences may arise that make the classifications and analysis less clear. Other examples, such as (12), are interpreted as non-reflexive attributives or self-benefactives and indicate that the Actor performs the process by his or her own means or for himself/herself, being a beneficiary of the verbal basis:

| Una | querella | por | auto-adjudicar=se | un | aparcamiento |

| a | lawsuit | for | self-reward.inf=se | a | parking.lot |

| ‘A lawsuit for self-rewarding a parking lot’ | |||||

2.2 A Construction Grammar approach to [auto- + V + se] structures

For this investigation, we used the model of Construction Grammar, based on the existence of constructions as basic units of analysis, i.e. form-meaning pairs (Traugott 2015), which are “pairings of form with semantic or discourse function, including morphemes or words, idioms, partially lexically filled and fully general phrasal patterns” (Goldberg 2006: 5). Concerning the new meanings associated with auto-, research has addressed how adding specific prefixes can affect the agentivity degree in the resulting constructions, either by increasing the agentivity of the arguments of the process or by decreasing it (Rooryck and Vanden Wyngaerd 2011). Synchronically, this framework allows us to analyse different languages from the notion of construction, and not from the notion of word, which can vary from one language to the other and whose limits are still diffuse.

Understanding a construction as “a form-meaning pairing in which the meaning of the whole is not derivable from the parts or a string whose meaning is predictable from its parts, but which occurs with sufficient frequency for it to be stored as a pattern” (Trousdale 2010: 52), let us consider the prefixed formations to be a new construction. Such a new construction has semantic and syntactic values not necessarily shared by the non-prefixed base. In this sense, verbal formations with auto- and the clitic se emerge as a specialization of non-prefixed constructions without the clitic se, with new values and semantic interpretations.

Furthermore, this model favours the connection between a synchronic and a diachronic perspective as the emergence of new constructions is due to the evolutionary process by which its schematicity, its productivity, and its non-compositionality are increased (Traugott 2015). Within this model, the emergence of a new pair is considered a “constructionalization”, that is, the rise of a new type of construction from others, with a “new syntax or morphology and new coded meaning, in the linguistic network of a population of speakers” (Traugott and Trousdale 2013: 22). In this sense, and following other proposals (Givón 2001; Haspelmath 2008), the new semantic features associated with the constructions with auto- arise in conjunction with new syntactic constraints.

Finally, we have also chosen this approach because it acknowledges the particular context of constructions for the analysis. We believe that considering the whole context of the new constructions is crucial for understanding the rise of new form-meaning pairs. This approach has a significant effect on the diachronic development because from a historical point of view grammaticization is not restricted only to the grammaticized element. “Instead, it is the grammaticizing element in its syntagmatic context, which is grammaticized. That is, the unit to which grammaticization properly applies to constructions, not isolated lexical items” (Himmelmann 2004: 31). Considering the context and a usage-based approach are fundamental for our research because the analysed units can be ambiguous in isolation and grant more than one interpretation depending on the context. In short, to thoroughly analyse the functioning and behaviour of these constructions, it is necessary to observe how they behave in their contexts of appearance, in order to show possible relations or decisive aspects.

2.3 A proposal for the distribution of constructions

As has been shown in the previous sections, pronominal constructions with or without auto- may fall into a range of different syntactic patterns: passive, impersonal, reflexive, reciprocal, anticausative, and transitive. Each type of construction can be identified according to not only the number of arguments but also the semantic macrorole associated with each one, which enables us to take into account both levels of analysis in an intrinsic relationship. Thus, while reflexive structures imply a higher degree of agentivity in the subject, by having an Actor, both passive and anticausative structures are expected to have a subject (Undergoer) with a low degree of agentivity.

From our point of view, Table 1 schematizes the distribution of functions among the three possible strategies (a. [V + se], b. [auto- + V + se], c. [auto- + V]):

Functions of [V + se], [auto- + V + se], and [auto- + V] constructions.[9]

| [V + se] | [auto- + V + se] | [auto- + V] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passive | Yes | No | No |

| Anticausative | Yes | Yes | No |

| Reciprocal | Yes | Yes | No |

| Reflexive | Yes | Yes | No |

Table 1 shows that [auto- + V + se] constructions are compatible with the reciprocal and reflexive functions because these have highly agentive Actors. In contrast, such constructions are not compatible with passives due to the non-agentive nature of Undergoers. In turn, anticausatives can be found in [auto- + V + se] constructions, but their subjects could be characterized as having more control over the event. As we will argue in the next pages, although the different strategies seem to overlap with each other in some functions of this schema, there is a clear continuum that relates these strategies with the semantic features of the the functions studied.

3 Methods

3.1 Sample

We applied a series of tests on two types of samples to evaluate differences between the constructions with and without the auto- prefix: (a) sample 1: 130 verbs extracted from a written corpus; (b) sample 2: linguistic assessments of Spanish speakers taken from their answers to a semi-directed interview.

In sample 1, we analysed 130 verbs extracted from the Modern Spanish Reference Corpus (CREA). CREA is composed of a wide range of oral and written texts from all Spanish-speaking countries and produced between 1975 and 2003.[10] Given that the constructions studied were found in texts from practically all countries, we consider this a pan-dialectal phenomenon. Although some of the verbs obtained from the corpus were clearly coinages, others can be easily checked to be existing forms in simple searches on web pages from different geographical areas.

For the elaboration of the sample, we first collected the complete data of constructions prefixed with auto- from CREA, after the elimination of the cases in which auto- does not correspond to the prefix but to the neoclassical lexeme (autismo) or to the standard lexeme in compound words (autovía). From this first filter, we obtained 13,214 cases in total, distributed into adjectives (2494), verbs (1755), nouns (8953), and adverbs (12). As the object of the study was the analysis of verbal constructions, we created a random sample from those 1755 verbs, with a confidence level of 95% and a maximum margin of error of 4%. This filter resulted in 447 tokens in total, corresponding to 170 types, from which the non-pronominal forms had to be subtracted. The application of a new filter of erroneous cases or cases causing problems of interpretation helped us to reduce the sample to 130 instances of pronominalized verbs.

Regarding the semantic categorization of verbs, these were not studied independently but from the context in which the verbs appeared, following the proposal of Construction Grammar (Traugott 2015; Hoffmann and Trousdale 2013), in order to understand most of these new formations and their possible semantic and syntactic restrictions. Then, for the contrastive work, we selected the same verbs without auto-, also from CREA, with contexts as similar as possible, to be able to compare them and explore the semantic peculiarity of the prefixed formations.

Next, 41 semi-directed interviews conducted with adult speakers of the city of Santiago, Chile, constitute sample 2. The aim of using surveys was not to obtain a sociolinguistic characterization but rather to corroborate the data obtained from the written corpus because we started from the supposition that the phenomenon has spread in the different speech communities. In other words, we believe that this survey, although restricted to one specific variety, should confirm the results from sample 1, as long as this is a pan-dialectal phenomenon. It would be interesting, however, to corroborate this information in later studies.

Among other tests in the interviews, we asked the respondents to choose the more natural expression in cases of contrast between prefixed and non-prefixed constructions. In addition, we asked for respondents’ grammatical judgements (e.g. Do (a) and (b) mean the same?) and reformulation (e.g. What does this mean to you?).

3.2 Diagnostic tests

The selected sample of pronominal and prefixed forms was subjected to a series of tests of agentivity and quantification of certain features, such as the number of arguments, mainly extracted and adapted from the work of Lakoff (1966) and Dowty (1991). The aim of our agentivity tests was to analyse the behaviour of such formations in different semantic and syntactic contexts and to assess whether the constructions with auto- were interpreted as possessing a higher degree of agentivity, presenting, in particular, a higher degree of volition or control over the action. The tests that were applied and compared between constructions with and without the prefix, were the following (See Table 2):

Agentivity tests applied to the corpus.

| 1. | Imperatives | The imperative mood (autoprográmate ‘program yourself’) should be acceptable for constructions with a high degree of agentivity. |

| 2. | Number of arguments | We looked for evidence of the prefix affecting the valency and argument structure from the base: autocontrolarse ‘control oneself’ < controlar ‘control’ (trans.) |

| 3. | Animacy | We used a scale for the arguments’ animacy ([0] = inanimate; [1] = ‘animized’, and [2] = animate), based on the premise that with a higher degree of animacy, there is a higher degree of agentivity. |

| 4. | Nominalizations | Nominalizations that refer to action processes (autogobernarse ‘self-governing’ > autogobierno ‘self-government’) should be acceptable for constructions with a high degree of agentivity. |

| 5. | Nominal formations in -dor | We analysed the hypothesis that -dor formations are connected to highly agentive bases (autoadministrarse > autoadministrador ‘to self-administer > self-administrator’). |

| 6. | Control verbs | We analysed the acceptability of infinitival clauses controlled by an event verb (Grimshaw 1990) under the hypothesis that this implies a higher degree of agentivity as long as the existence of an agent that does something volitionally is assumed (Tsunoda 1981). |

| 7. | “Compel” verbs | These constructions as a complement to verbs such as as forzar ‘force’ and obligar ‘compel’ (lo obligaron a autoprogramarse ‘he was compelled to program himself’) should be acceptable if there is a high degree of agentivity. |

| 8. | (Non-)intentional adverbs | A higher degree of agentivity should be compatible with adverbs such as deliberadamente ‘deliberately’, cuidadosamente ‘carefully’, or a propósito ‘on purpose’ (se autoprogramó a propósito ‘(s)he programmed him/herself’), and not with accidentalmente ‘accidentally’ or espontáneamente ‘spontaneously’. |

| 9. | Cleft sentences | Cleft sentences (lo que hizo x fue ‘what he/she did was’ + non-finite verb clause) and negated cleft sentences (lo que hizo fue autoprogramarse ‘what (s)he did was to program him/herself’) should be acceptable if there is a high degree of agentivity. |

In addition, we considered a series of semantic features that could be related to the existence of an Actor in the clauses in which the constructions appeared. Some of them show the existence of an Actor that makes a change from an Undergoer to a new state, put emphasis on the Actor’s responsibility in the performance of an action that is considered volitional (Dowty 1991), or indicate the existence of an agent as an energy source that produces changes by its action (Cruse 1973; Tsunoda 1999; Hundt 2004; Verhoeven 2010).

Although the initial aim of the tests was to detect stativity, they are useful for evaluating the agentivity scale of analysed constructions and thus distinguishing between agentive and non-agentive constructions. As Levin (2009: 8) points out, “several purported stativity tests are agentivity tests”. Therefore, if we think not in discrete or binary terms but instead in terms of a continuum of agentivity, we see that the higher the acceptance of tests is for the constructions concerned, the greater is the degree of agentivity, taking into account, of course, the contextual restraints on these constructions.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Results of the corpus analysis

As a first general result, we can state that not all tests are equally conclusive. They do, however, show a tendency to connect prefixed constructions with a higher degree of agentivity or control. In this section, we describe some of the tests applied to the sample individually, followed by the overall results.

4.1.1 Compatibility with intentional adverbs

As shown in Table 3, one of the most useful tests was the compatibility of formations with auto- and volitional adverbs, which emphasizes the agentive and volitional nature of the verbal event and its incompatibility with adverbs of spontaneity or accidentality or with inanimate subjects. Almost all prefixed cases admitted a volitional adverb, while in the cases without auto- this alternative was neither the only nor the most dominant one.

Compatibility with intentional adverbs.

| + accidentally (non-volitive) | + on purpose (volitive) | Both | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formations with auto- | 3.6% | 80.6% | 15.5% |

| Formations without auto- | 9.4% | 54.3% | 36.2% |

(13) and (14) illustrate the compatibility and incompatibility of formations with the adverbs mentioned above:[11]

| a. | Una | querella | por | auto-adjudicar=se | ||||||||||

| a | lawsuit | for | self-reward.inf=se | |||||||||||

| (a propósito/accidentalmente) | un | aparcamiento | ||||||||||||

| (on.purpose/accidentally) | a | parking.lot | ||||||||||||

| ‘A lawsuit for self-rewarding a parking lot (on purpose/accidentally)’ | ||||||||||||||

| b. | Julie | pudo | adjudicar=se | (a propósito/accidentalmente) | ||||||||||

| Julie | can.pst.3sg | adjudicate.inf=se | (on.purpose/accidentally) | |||||||||||

| seis | puntos | en | el | segundo | set | |||||||||

| six | points | in | the | second | set | |||||||||

| ‘Julie (…) could adjudicate (on purpose/accidentally) six points in the second set’ | ||||||||||||||

| a. | Las | líneas | editoriales | se | negocian, | ||||||||||

| the | lines | editorial | se | negotiate.prs.3pl | |||||||||||

| se | auto-aniquilan | (a propósito/accidentalmente) | |||||||||||||

| se | self-destroy.prs.3pl | (on.purpose/accidentally) | |||||||||||||

| cuando | termina | un | gobierno | ||||||||||||

| when | end.prs.3sg | a | government | ||||||||||||

| ‘The editorial lines are negotiated, they self-destruct (on purpose/accidentally) when a government ends’ | |||||||||||||||

| b. | Cuando | materia | y | antimateria | colisionan, | |||||||||||

| when | matter | and | antimatter | collide.prs.3pl | ||||||||||||

| se | aniquilan | (*a propósito/accidentalmente) | ||||||||||||||

| se | destroy.prs.3pl | (*on.purpose/accidentally) | ||||||||||||||

| y | la | masa | se | convierte | en | energía | ||||||||||

| and | the | mass | se | convert.prs.3sg | into | energy | ||||||||||

| ‘When matter and antimatter collide, they self-destruct (*on purpose/accidentally) and the mass is converted into energy’ | ||||||||||||||||

If we now consider the analysis only on the base of the acceptability of the a propósito ‘on purpose’ reinforcement, the closer connection to prefixed constructions is also evident, as seen in Table 4.

Acceptability of a propósito as the only possible interpretation.

| + auto- | − auto- | |

|---|---|---|

| + a propósito | 104 | 70 |

| − a propósito | 26 | 59 |

This test is interesting when applied to anticausatives. Although the demotion of the Actor/Force is the most salient feature that defines anticausatives (which should, therefore, be non-volitional), examples with auto- show a more volitional interpretation than is the case with non-prefixed verbs/constructions:

| a. | Estos | sistemas (…) | se | auto-organizan | |||||||||

| these | systems | se | self-organize.prs.3pl | ||||||||||

| en | niveles | (a propósito/*accidentalmente) | |||||||||||

| in | levels | (on.purpose/*accidentally) | |||||||||||

| ‘These systems organize themselves (on purpose/ *accidentally) in levels’ | |||||||||||||

| b. | Las | bacterias | devoran | al | insecto | ||||||||

| the | bacteria | devour.prs.3pl | to.the | insect | |||||||||

| y | se | reproducen | (? a propósito/accidentalmente) | ||||||||||

| and | se | reproduce.prs.3pl | (? on.purpose/accidentally) | ||||||||||

| ‘Bacteria devour the insect and reproduce themselves (? on purpose/accidentally)’ | |||||||||||||

| a. | Este | mensaje | se | auto-destruirá | (a propósito/accidentalmente) | |||

| this | message | se | self-destroy.fut.3sg | (on.purpose/accidentally) | ||||

| en | cinco | segundos | ||||||

| in | five | seconds | ||||||

| ‘This message will destroy itself (on purpose/accidentally) in five seconds’ | ||||||||

| b. | Este | mensaje | se | destruirá | (? a propósito/accidentalmente) | ||||

| this | message | se | destroy.fut.3sg | (? on.purpose/accidentally) | |||||

| en | cinco | segundos | |||||||

| in | five | seconds | |||||||

| ‘This message will destroy itself (? on purpose/accidentally) in five seconds’ | |||||||||

Note that (15a) accepts a volitional adverb because the subject is animized. This means that although it is inanimate, higher degrees of control and agentivity over the event are granted in this context. With regard to the examples in (16), an interesting difference between (a) and (b) arises. As stated above, the se strategy is polysemic, which is due to a long process of grammaticalization. Se destruirá is an anticausative alternation in cases such as (16b), and it blocks the Actor or external cause as an Actor-backgrounding passive and as an impersonal. Unlike non-prefixed constructions, the impersonal and the passive interpretations are automatically ruled out in cases with auto- as in (16a). This is made evident by the impossibility of adding an external cause in clauses with prefixed formations:[12] *este mensaje se autodestruirá por la explosión *‘this message will be self-destroyed by the explosion/this message will be destroyed by the explosion’, an operation that is possible for passives: este mensaje se destruirá por la explosion ‘this message will be destroyed by the explosion’ (the addition of an external cause necessarily to the passive interpretation of se). As for the impersonal interpretation, this is usually a less controlled event because of the lack of an Actor, and this is not consistent with the tests that accept formations with auto-, which tend to show a higher degree of control.

4.1.2 Animacy of the main argument

As shown in Table 5, another feature associated with the higher agentive nature of cases with auto- is the significant number of animate or animized subjects, the latter understood as nominal elements not animate initially, but which act as such. This ‘animization’ can be checked by means of the type of adjectives with which they combine or through other forms of qualification.

Animacy scale for arguments in formations with and without auto-.

| − animate | +/− animized | + animate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefixed constructions | 16.4% | 22.6% | 60.9% |

| Non-prefixed constructions | 34.4% | 12.2% | 53.2% |

As Table 5 shows, there is a substantial difference between prefixed constructions with an animate referent (60.9%) and prefixed constructions with a non-animate referent (16.4%), as well as the non-prefixed constructions with a non-animate referent (34.4%). In (17a), for example, an inanimate element, science, turns into an animate noun as it is equated to a monster; in (17b) and (17c), in turn, the choice of a mental process and action, respectively, points to a higher degree of animacy or agentivity of the initially inanimate subject, the company and the Constitution.

| a. | La | ciencia | es | un | monstruo | que | se | auto-perfecciona | |||||||||||||

| the | science | is | a | monster | that | se | self-improve.prs.3sg | ||||||||||||||

| ‘Science is a self-improving monster’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Desde | sus | orígenes | la | empresa | |||||||||||||||||

| from | its | origins | the | company | ||||||||||||||||||

| se | ha | auto-concebido | como | interdisciplinar | ||||||||||||||||||

| se | have.prs.3sg | self-conceive.pp | as | interdisciplinary | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘From its origin, the company has conceived itself as interdisciplinary’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Ante | una | posible | amenaza | a | la | democracia | |||||||||||||||

| facing | a | possible | threat | to | the | democracy | ||||||||||||||||

| la | Constitución | se | auto-defiende | |||||||||||||||||||

| the | Constitution | se | self-defend.prs.3sg | |||||||||||||||||||

| ‘When faced with a possible threat to democracy, the Constitution has self-defense mechanisms’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

4.1.3 Imperatives

Prefixed constructions also tend to accept imperatives, as is the case in (18b):

| a. | (…) | para | que | cada | usuario | se | auto-programe | los | contenidos | ||

| for | that | each | user | se | self-program.sbjv.3sg | the | contents | ||||

| ‘(…) So that each user programs the contents himself’ | |||||||||||

| b. | → ¡Auto-prográma=te | los | contenidos! | |||||||

| self-program.imp.2sg=se | the | contents | ||||||||

| → ‘Program the contents yourself!’ | ||||||||||

Note, however, that this test is not as conclusive as the previous ones and that it does not mean that non-prefixed constructions are impossible with imperative mood, rather that they express a different semantic value:

| a. | El | teléfono (…) | se | programa | y | se | ||||

| the | telephone (…) | se | program.prs.3sg | and | se | |||||

| le | asigna | un | número | |||||||

| it.dat.3sg | assign.prs.3sg | a | number | |||||||

| ‘The telephone is programmed and assigned a number’ | ||||||||||

| b. | → * ¡Prográma=te! | |||||||

| program.imp.2sg=se | ||||||||

| → * ‘Self-program!’ | ||||||||

4.1.4 Other tests

We also applied other tests with useful results although with some limitations due to the nature of these constructions. One of them is the acceptability of cleft sentences, closely connected to the animacy test. While almost all of the prefixed cases admit cleft sentences (20b) and negated cleft sentences (22b), their compatibility with pronominal formations without a prefix is questionable (21b, 23b) as the following examples show:

| a. | Él | se | asume | y | auto-rrotula | coreógrafo | |

| he | se | assume.prs.3sg | and | self-label.prs.3sg | choreographer | ||

| ‘He assumes the role and calls himself as a choreographer’ | |||||||

| b. | → Lo que | hizo | él | fue | ||||

| what | do.pst.3sg | he | be.pst.3sg | |||||

| auto-rrotular=se | coreógrafo | |||||||

| self-label.inf=se | choreographer | |||||||

| → ‘What he did was to call himself as a choreographer’ | ||||||||

| a. | Nunca | supimos | (…) | por qué... | ||||||

| …el | mercado | (…) | se | rotula | Mercado de Guzmán el Bueno | |||||

| the | market | se | label.prs.3sg | Mercado de Guzmán el Bueno | ||||||

| ‘We never knew why the market is called Guzmán el Bueno Market’ | ||||||||||

| b. | → *Lo que | hizo | el | mercado | fue | |||

| what | do.pst.3sg | the | market | be.pst.3sg | ||||

| rotular=se | Mercado de Guzmán el Bueno | |||||||

| label.inf=se | Mercado de Guzmán el Bueno | |||||||

| → *‘What the market did was to be called Guzmán el Bueno Market’ | ||||||||

| a. | ETA | es | una | organización | mucho | más | compleja | que | ||||||

| ETA | be.prs.3sg | a | organization | much | more | complex | that | |||||||

| se | auto-rregenera (…) | como | cualquier | organismo | vivo | |||||||||

| se | self-regenerate.prs.3sg | as | any | organism | living | |||||||||

| ‘ETA is a much more complex organization, which regenerates itself like any other living organism’ | ||||||||||||||

| b. | → Lo que | hizo | ETA | fue | no | auto-rregenerar=se | ||||||||

| what | do.pst.3sg | ETA | be.pst.3sg | neg | self-regenerate.inf=se | |||||||||

| → ‘What ETA did was not to self-regenerate’ | ||||||||||||||

| a. | La | economía | española | no | se | regenera | ||||||

| the | economy | Spanish | neg | se | regenerate.prs.3sg | |||||||

| ‘The Spanish economy does not regenerate’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | → ? Lo que | hizo | la | economía | española | |||||||

| what | do.pst.3sg | the | economy | spanish | ||||||||

| fue | no | regenerar=se | ||||||||||

| be.pst.3sg | neg | regenerate.inf=se | ||||||||||

| → ? ‘What the Spanish economy did was not to regenerate’ | ||||||||||||

As these examples show, (20b) is acceptable as a derivation from the prefixed construction in (20a) while (21b) is not. The same contrast is evident in negated constructions: (22b) versus (23b). Note that the examples in (21) are barely comparable to those in (20) given the inanimate nature of the subject. However, a consequence of this difference is the impossibility of accepting a cleft sentence in (21). Interestingly enough, even when autorrotularse ‘to call oneself’ seems not to be comparable to rotularse ‘to be called’, it is evident that only autorrotularse admits an agentive interpretation. In order to obtain a similar reading without the prefix, we need an intensifying marker instead, as in (24):

| Si me fue mal en una prueba de matemáticas… | |||||||||

| me | rotulo | a | mí mismo | como | malo | para | las | matemáticas | |

| se | label.prs.1sg | to | myself | as | bad | for | the | math | |

| ‘If I fail the math test … I label myself as “bad at math’”[13] | |||||||||

Another test was the paraphrasability with constructions of the type prefirió ‘preferred’, hacerse cargo de ‘take charge of’, su propio/a ‘his/her own’ + nominalization, which introduce a behavioural process (preferir) that denotes a volitional choice:

| a. | Gil y Gil | se | postula | como | candidato | ||||||||||||||||

| Gil y Gil | se | stand.prs.3sg | as | candidate | |||||||||||||||||

| a | presidente | de | la | asociación | |||||||||||||||||

| for | president | of | the | association | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘Gil y Gil stands as a candidate for president of the association’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | → Gil y Gil | prefirió | hacer=se | cargo | de | ||||||||||||||||

| Gil y Gil | prefer.pst.3sg | take.inf=se | charge | of | |||||||||||||||||

| su | propia | postulación | |||||||||||||||||||

| his/her | own | nomination | |||||||||||||||||||

| → ‘Gil y Gil preferred to take charge of his own nomination’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Serpa | se | auto-postula | como | |||||||||||||||||

| Serpa | se | self-nominate.prs.3sg | as | ||||||||||||||||||

| interlocutor | del | presidente | |||||||||||||||||||

| spokesperson | of.the | president | |||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Serpa nominates himself as the president’s spokesperson’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | → ? Serpa | prefirió | hacer=se | cargo | de | ||||||||||||||||

| Serpa | prefer.pst.3sg | take.inf=se | charge | of | |||||||||||||||||

| su | propia | auto-postulación | |||||||||||||||||||

| his/her | own | self-nomination | |||||||||||||||||||

| → ? ‘Serpa preferred to take charge of his own self-nomination’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

As is evident in these examples, the presence of behavioural and volitional verbs makes these constructions redundant since a high degree of control and agentivity is already present. Although it is possible to think that the paraphrase su propio/a ‘his/her own’ is sufficient, this may still be ambiguous, so we have opted for a more redundant structure that ensures the maximum reduction of possible ambiguities. Note, however, that this is a complex test because these nominalizations are neological units, which makes the acceptability criteria highly problematic.

There is a similar problem, though with significant results, in the analysis of the derivation with -dor for the prefixed formations:

| a. | Me | auto-rreprochaba | de | mi | cobardía | ||||||||||||||

| se | self-reproach.pst.1sg | of | my | cowardice | |||||||||||||||

| por | no | haber=le | contestado | ||||||||||||||||

| for | neg | have.inf=3sg.dat | reply.pp | ||||||||||||||||

| ‘(I) reproached myself for my cowardice for not having replied (to her/him)’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| b. | → ? Soy | un | auto-rreprochador | ||||||||||||||||

| be.prs.1sg | a | self-reproacher | |||||||||||||||||

| → ? ‘I am a self-reproacher’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Aldo | ya | no | se | reprochaba | el | sadismo | ||||||||||||

| Aldo | already | neg | se | reproach.pst.1sg | the | sadism | |||||||||||||

| de | jugar | con | su | presa | |||||||||||||||

| of | play.inf | with | his | prey | |||||||||||||||

| ‘Aldo no longer reproached himself for the sadism of playing with his prey’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| d. | → Es | un | reprochador | ||||||||||||||||

| is | a | reproacher | |||||||||||||||||

| → ‘(He) is a reproacher’ | |||||||||||||||||||

Overall, there is an interesting tendency for prefixed constructions to show a higher degree of agentivity and control. As Table 6 shows, there is no dichotomous but rather a gradual difference between these constructions when we apply the tests.

Results of the application of tests to the CREA corpus.

| + auto- | − auto- | |

|---|---|---|

| Incompatibility with the type ‘prefer to + nominalization’ | 68.9% | 16.2% |

| Derivation with -dor suffix | 68.9% | 82.2% |

| Embedding with control verbs | 83.8% | 70.8% |

| Complement to ‘to compel’ verbs | 80.0% | 69.2% |

| Imperatives | 74.6% | 66.9% |

| Cleft sentences | 95.4% | 78.5% |

| Negated cleft sentences | 86.9% | 68.5% |

Summing up the results from the CREA corpus, we can claim that there is a higher tendency in pronominal constructions with auto- to accept features related to control and agentivity. These features are typical of reflexive constructions but not limited to them.

4.2 Results from interviews

As stated above, this instrument aimed to verify results from the analysed corpus data by making use of Spanish native speakers. The primary outcome is that the interviews reveal a general tendency for cases with auto- to be considered more agentive, while non-prefixed constructions are more underspecified regarding control and agentivity as Tables 7 and 8 show.

Linguistic judgements and choices of verbal formations with auto- in two examples.

| Passive, non-intentional and inanimate contexts | Agentive, volitive and animate/animized contexts | |

|---|---|---|

| Autoconsiderarse | 2.4% | 70.7% |

| Autoprescribirse | 17.1% | 90.2% |

| Total verbal forms with auto- | 10.8% | 89.1% |

Judgements on the event’s volition, spontaneity, or intentionality.

| Prefixed constructions | Non-prefixed constructions | |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of a more intentional action | 78.8% | 21.9% |

| Perception of spontaneous action (regenerarse/autorregenerarse set) | 51.2% | 48.7% |

| Perception of a more agentive action of which the subject is responsible | 70.7% | 29.2% |

As Tables 7 and 8 show speakers tend to prefer verb forms with auto- in unambiguous agentive, volitional, and animate/animized contexts. Furthermore, there is a tendency to perceive prefixed constructions as more intentional and involving more engaged Actor subjects. This became particularly clear when we asked speakers to explain or paraphrase the given sample. In most prefixed constructions, speakers opted for expressions highly marked for volition or responsible engagement, such as “the subject wanted to do x”, “he had the intention of performing x”, or “he was responsible for performing x”. In contexts that lacked these features or were ambiguous regarding them, speakers tended to choose the option without auto- as in (27):

| En el siglo XVI la división urbana de la ciudad se conformaba por la villa y sus barrios. (…) | |||

| El | centro de la ciudad | ____ (se consideraba/se auto-consideraba) … | |

| the | downtown | ____ (seconsidered/se self-considered) … | |

| … como la villa, mientras que las zonas periféricas se designaban barrios | |||

| ‘In the XVIth century the urban division of the town was made up of the village and its neighbourhoods. The downtown _____ (was considered/was self-considered) the village, while the peripheral areas were designated as neighbourhoods’ | |||

4.3 Discussion

As has been shown extensively in this paper, pronominal constructions with auto- seem to relate to control and agentivity features more than those without the prefix. Although one may relate these features to the reflexive nature of (some of) these constructions, this is an oversimplification as agentivity and control features are similarly found in non-reflexive pronominal constructions with auto-:

| Prendas | que | se | auto-lavan |

| clothes | that | se | self-wash.prs.3pl |

| ‘Self-cleaning clothes’[14] | |||

The inanimate nature of the subject in (28) makes it impossible to consider it a reflexive construction, although the use of the prefix points to the absence of an external agent and the capacity of self-control by the clothes. Therefore, agentivity and control are not restricted to reflexive constructions.

Another piece of evidence that connects the agentivity feature to the presence of the prefix, and not merely to the reflexive nature of the construction, is that non-pronominal constructions such as those in (29a) and (29b) are also highly agentive:

| a. | Auto-controle | su | glucemia | |||||

| self-control.imp.2sg | your | blood.sugar.level | ||||||

| ‘Check your blood-sugar level yourself’ | ||||||||

| b. | Estos | auto-estimulan | la | liberación | de | histamina | ||

| these | self-stimulate.prs.3pl | the | release | of | histamine | |||

| ‘They self-stimulate histamine release’ | ||||||||

(29a) and (29b) are transitive and display highly agentive subjects, which can only be due to the use of the prefix. It seems evident, therefore, that even when auto- is not necessarily by itself an agentivity or control prefix, verbal constructions with it are prone to acquire such values.

A third argument in favour of this interpretation comes from the comparison between autosuicidarse, literally ‘to self-commit suicide’, and automatarse ‘to self-kill’. Although we did not use these verbs in the interviews (as they did not come up in the sample), the widespread use of autosuicidarse on Internet websites in diverse Spanish varieties reveals the large spread of this phenomenon:

| a. | Jou | se | auto-suicidó | a | sí mismo | ||||||||||||

| Jou | se | self-suicide.pst.3sg | to | himself | |||||||||||||

| el | solo | sin | ayuda | de | nadie | ||||||||||||

| he | alone | without | help | from | nobody | ||||||||||||

| ‘Jou committed suicide, he did it alone without anyone’s help’ | |||||||||||||||||

| b. | Resulta curioso que vayan a por … | ||||||||||||||||

| una | página | que | se | auto-suicidó …. | |||||||||||||

| a | web.page | that | se | self-suicide.pst.3sg | |||||||||||||

| …cuando cambió la ley. No se si sus creadores habrán participado en la creación de otras ¿pero acaso aún hay alguien que visite ‘Series.ly’? | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘It is curious that they go for a web page that committed suicide when the law changed. I wonder whether their creators might have participated in the creation of other pages. Is there still anyone who visits ‘Series.ly’?’ | |||||||||||||||||

| c. | Un | ruquito | se | auto-suicidó | en | Indaparapeo | |||||||||||

| a | ruquito | se | self-suicide.pst.3sg | in | Indaparapeo | ||||||||||||

| ‘A ruquito committed suicide in Indaparapeo’ | |||||||||||||||||

| d. | Juan Carlos Vélez, | ¿se | auto-suicidó | ||||||||||||||

| Juan Carlos Vélez | se | self-suicide.pst.3sg | |||||||||||||||

| marcándo=se | con | el | GEA? | ||||||||||||||

| identify.ger=se | with | the | GEA | ||||||||||||||

| ‘Did Juan Carlos Vélez commit suicide by identifying himself with the GEA?’ | |||||||||||||||||

From a strictly normative point of view, it could be claimed that these are redundant formations because of the reflexive lexical nature of the verb suicidarse (confirmed by the incompatibility with a sí mismo/a). Still, Spanish speakers often prefer that option, thus granting the subject more control over the event. These constructions are primarily in contexts of online games as seen in (30a), suggesting a degree of greater control by the Actor because, in this way, participants may choose to leave the game. Something similar happens in (30c): the body of the text of this note further explains the possible causes that may have caused that person to take such a decision. In some cases, moreover, the expression acquires an ironic or ludic value indicating a character mocking the event. Finally, as seen in (30d), this construction appears frequently in political discourse, possibly disseminated in Latin America through a public commentary by former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Compared to constructions with suicidarse ‘to commit suicide’, the prefix in constructions with automatarse is used to add an agentive and control feature and thus to disambiguate it from the accidental reading that is typically rendered by the verb matarse in Spanish:

| a. | Un | soldado | se | mató | accidentalmente | ||||

| a | soldier | se | kill.pst.3sg | accidentally | |||||

| ‘A soldier got killed accidentally’ | |||||||||

| b. | *Un | soldado | se | auto-mató | accidentalmente | ||||

| a | soldier | se | self-kill.pst.3sg | accidentally | |||||

| *‘A soldier ‘self-killed’ accidentally’ | |||||||||

The fourth and last argument comes from our review of proscriptions found in prescriptive texts. As the example below shows, the use of auto- in most of these constructions is usually blocked; this shows that there is a “need” to battle against the widespread “faulty” use of this prefix:

| ¿Qué ejemplos deben rechazarse por incorrectos? | |

| a. | Ese grupo se autodestruyó. / Ese grupo se destruyó. |

| b. | Ese cantante se suicidó. / Ese cantante se autosuicidó. |

| ‘Which examples must be rejected as incorrect? | |

| a. | That band self-destroyed. / That band destroyed itself. |

| b. | That singer commited suicide. / That singer committed self-suicide.’[15] |

Another similar judgement can be found in “Cuando los autos chocan” (‘When autos crash’),[16] where the journalist steadily complains about the “abuse” of this prefix in the press. These examples indicate that the normative idea is usually that auto- is incorrect or superfluous.

4.4 A possible explanation for agentive constructions with auto-

Although we find the use of auto- in verbs early in the history of Spanish, the vitality of these particular pronominal agentive constructions is recent and relates to another ongoing change that affects non-prefixed constructions only with se. As was stated earlier in this paper, constructions with se are highly polysemous because they allow many diverse interpretations (reciprocal, reflexive, anticausative, and so forth). It is plausible, therefore, that the use of the prefix arose as a way to disambiguate, in parallel with the already existing reinforcement by the prepositional phrase a sí mismo/a(s). This hypothesis is in line with the claim that constructions with se show a decrease of the Actor’s relevance and the subsequent privileging of the Undergoer on the semantic level of the clause. Thus, as González Vergara (2014: 156) concludes from a Role and Reference Grammar approach, “constructions with se display the non-specification of the highest-ranking role in the logical structure”. If this is the case, we can expect that the prefix seeks the opposite effect.

It is also interesting to compare verbal and nominal constructions, with and without auto-. The noun reproche ‘reproach’, for instance, is not as ambiguous regarding the valency as is the verb reprocharse because the verbal construction can be both reflexive and transitive. The prefix in the noun autorreproche probably does not function necessarily as a disambiguating device as it does in autorreprocharse. The reflexive reading is less controversial, therefore, in nominal formations than it is in verbal formations.

The tremendous ambiguity of se and the possible solutions in Spanish have different parallels in other Romance languages. An ongoing tendency is the one found in Brazilian Portuguese, where the se clitic is dropped as a disambiguating device: “the null se construction is more associated with cognition middles, change of posture, anticausatives, passive-impersonal and impersonal domains […] Those event types that imply a high degree of control tend to occur with overt se constructions” (Afonso and Soares da Silva 2019: 22). Interestingly enough, se began to be dropped in some recent instances in Spanish too, as in the new unergative entrenar (‘to train oneself’), as a recent development from a previous transitive counterpart (‘to train someone’) to entrenarse (‘to train oneself’): “The intransitive non-pronominal construction is also admitted, which prevails in current usage” (RAE and ASALE 2005, s.v. entrenar(se), translation ours).

5 Conclusions

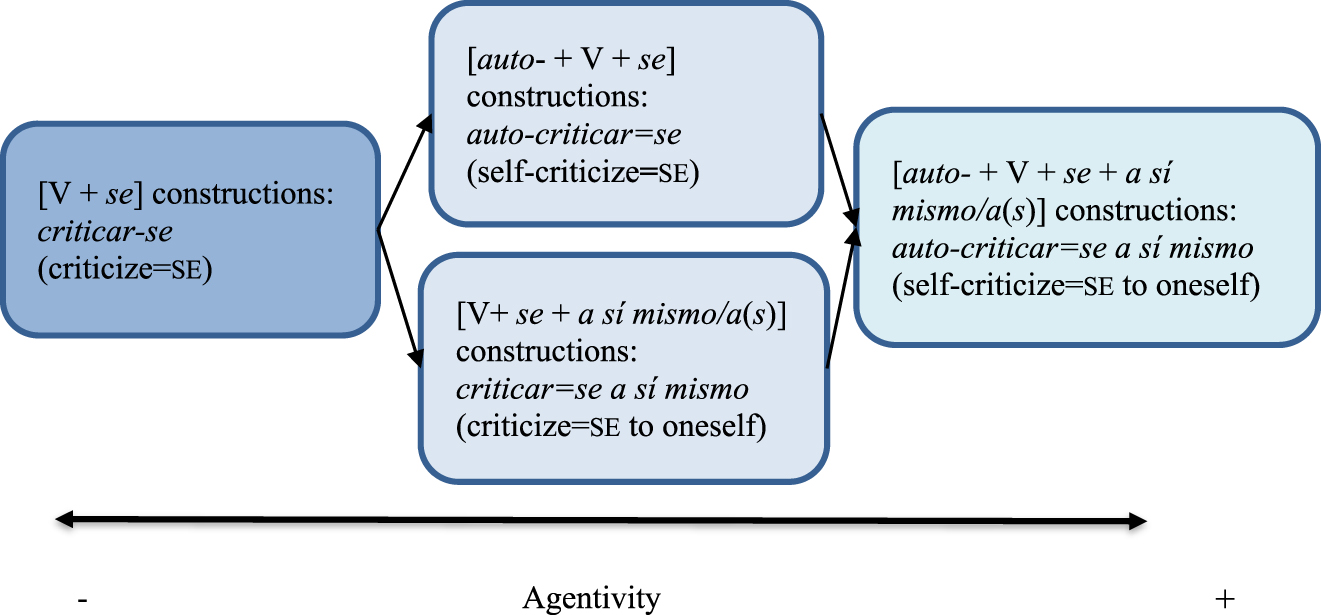

The data presented here allow us to confirm that, overall, [auto- + V + se] constructions are not limited exclusively to the reflexive interpretation. Although they are polysemous constructions, we may conclude that there is a tendency to associate them with a higher degree of control and volition (and consequently, a macro-feature of agentivity) by the Actor, compared to the non-prefixed constructions, which are underspecified regarding those features. Thus, these two types of constructions are not synonymous, nor is the prefix strategy merely pleonastic. As our analysis suggests, the diverse strategies might be located at different points in a hypothetical continuum of agentivity, as shown in Figure 1.

Continuum of agentivity in pronominal verbal constructions.

Thus, the pronominal verbal formations underspecified for agentivity and those that are non-agentive (passive, impersonal, anticausative) concentrate on the less agentive pole. The addition of the prefix increases the degree of agentivity progressively through the sub-features of control, volition, and active engagement of the external argument. Finally, heavily marked constructions making use of all the strategies are found on the extreme right pole. This last type demonstrates the possible dissimilar values provided by each strategy and the need for disambiguation by speakers.

Thus, our study strongly suggests that the prefix auto- contributes a unique semantic nuance to the pronominal constructions because there is a regular tendency to increase the degree of agentivity. In this sense, agentivity would be a necessary semantic condition for the syntactic constraints on reflexivity. In other words, while reflexive constructions need to be highly agentive, not all highly agentive constructions are reflexive. From a Construction Grammar approach, the formations prefixed with auto- correspond to new constructions and provide an example of ‘constructionalization’: a new pair of form (prefixed pronominal construction) and meaning (heavily marked as agentive) emerges from the simple and semantically ambiguous pronominal construction.

Finally, as a possible explanation, we have suggested that the emergence of these cases might relate to the ongoing change experienced by the polysemous constructions with se, which are generally characterized by a less prototypical Actor (or even by the Undergoer macrorole). Again, we think that a Construction Grammar approach provides a solid model for this, as we need to consider the construction as a whole in its synchronic and diachronic context to explain how a specific semantic feature emerges.

Appendix: List of 130 verbs from CREA

| 1. autoabastecerse | 2. autoadjudicarse | 3. autoadmitirse | 4. autoafeitarse |

| 5. autoacusarse | 6. autoadministrarse | 7. autoafirmarse | 8. autoalabarse |

| 9. autoalimentarse | 10. autocandidatearse | 11. autoconfesarse | 12. autoconvocarse |

| 13. autoanalizarse | 14. autocastigarse | 15. autoconocerse | 16. autocorregirse |

| 17. autoaniquilarse | 18. autocensurarse | 19. autoconscientizarse | 20. autoconvertirse |

| 21. autoasegurarse | 22. autocertificarse | 23. autoconstituirse | 24. autocriticarse |

| 25. autoasignarse | 26. autoconcebirse | 27. autoconstruirse | 28. autoconvencerse |

| 29. autocalificarse | 30. autocondecorarse | 31. autocontrolarse | 32. autodiagnosticarse |

| 33. autocatalizarse | 34. autoconferirse | 35. autocomprenderse | 36. autocompensarse |

| 37. autocrearse | 38. autodepreciarse | 39. autodestaparse | 40. autodisolverse |

| 41. autocrisparse | 42. autodeprimirse | 43. autodestruirse | 44. autodramatizarse |

| 45. autodebilitarse | 46. autodepurarse | 47. autodetenerse | 48. autoformularse |

| 49. autodeclararse | 50. autodescalificarse | 51. autodeterminarse | 52. autogenerarse |

| 53. autodefenderse | 54. autodescartarse | 55. autodiferenciarse | 56. autoformarse |

| 57. autodefinirse | 58. autodescomponerse | 59. autodigerirse | 60. autoflagelarse |

| 61. autodenigrarse | 62. autodesignarse | 63. autodirigirse | 64. autoexpulsarse |

| 65. autodenominarse | 66. autodespedir | 67. autodisciplinarse | 68. autofertilizarse |

| 69. autoduplicarse | 70. autoelogiarse | 71. autoexcluirse | 72. autofianciarse |

| 73. autoelegirse | 74. autoemocionarse | 75. autoexcusarse | 76. autoexpatriarse |

| 77. autoeliminarse | 78. autoengañarse | 79. autoexigirse | 80. autoexonerarse |

| 81. autogestionarse | 82. autoinfectarse | 83. autolesionarse | 84. autonombrarse |

| 85. autogobernarse | 86. autoinhabilitarse | 87. autolimitarse | 88. autoobservarse |

| 89. autogolearse | 90. autoinmolarse | 91. autojubilarse | 92. autopercibirse |

| 93. autogolpearse | 94. autoinscribirse | 95. autollamarse | 96. autoperfeccionarse |

| 97. autoidentificarse | 98. autoinstaurarse | 99. automatricularse | 100. autopostularse |

| 101. autoincriminarse | 102. autoimponerse | 103. autoinventarse | 104. autopreciarse |

| 105. autoinculparse | 106. autointoxicarse | 107. automedicarse | 108. autopremiarse |

| 109. autopresentarse | 110. autoproclamarse | 111. autoprogramarse | 112. autoprescribirse |

| 113. autoprivarse | 114. autorreforzarse | 115. autorresponsabilizarse | 116. autosecuestrarse |

| 117. autoprotegerse | 118. autorregenerarse | 119. autorretratarse | 120. autosuperarse |

| 121. autorganizarse | 122. autorregularse | 123. autorrotularse | 124. autovalorarse |

| 125. autorrealizarse | 126. autorreprocharse | 127. autotitularse | 128. autoxidarse |

| 129. autorrecetarse | 130. autorreproducirse | ||

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of the research projects FONDECYT 11170045 and FONDECYT 3150246, funded by the FONDECYT program of CONICYT (National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research), Chile. We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers and the two editors for their constructive comments. We also thank the participants at the Coloquio Permanente de Lingüística, as well as Carlos Muñoz Perez, for their comments on previous versions.

References

Afonso, Susana & Augusto Soares da Silva. 2019. The null reflexive construction in Brazilian Portuguese. Paper presented at the 52nd annual meeting of the Societas Linguistica Europaea (SLE), Leipzig University, 21–24 August.Suche in Google Scholar

Bogard, Sergio. 2006. El clítico se: valores y evolución. In Concepción Company Company (ed.), Sintaxis histórica de la lengua española, vol. 2(1), 755–874. México: UNAM/FCE.Suche in Google Scholar

Cennamo, Michela, Thórhallur Eythórsson & Johánna Barðdal. 2015. Semantic and (morpho)-syntactic constraints on anticausativization: Evidence from Latin and Old Norse-Icelandic. Linguistics 53(4). 677–729. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2015-0015.Suche in Google Scholar

CREA= Real Academia Española. Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual. https://corpus.rae.es/creanet.html (accessed 17 June 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Cruse, D. Alan. 1973. Some thoughts on agentivity. Journal of Linguistics 9(1). 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226700003509.Suche in Google Scholar

Dowty, David. 1991. Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language 67. 547–619. https://doi.org/10.2307/415037.Suche in Google Scholar

Felíu, Elena. 2003a. Morfología derivativa y semántica léxica: la prefijación de auto-, co- e inter-. Madrid: Ediciones de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.Suche in Google Scholar

Felíu, Elena. 2003b. Morphology, argument structure, and lexical semantics: The case of Spanish auto- and co- prefixation to verbal bases. Linguistics 41(3). 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.2003.017.Suche in Google Scholar

Felíu, Elena. 2005. Los sustantivos formados con el prefijo auto- en español: descripción y análisis. Verba 32. 331–350.Suche in Google Scholar

García-Medall Villanueva, Joaquín. 1988. Diversificación y desarrollo del prefijo auto- en español actual. In Emili Casanova & José Luis Espinosa Carbonell (eds.), Homenatge a José Belloch Zimmermann, 119–134. Valencia: Universitat de València.Suche in Google Scholar

Gast, Volker. 2007. The grammar of identity: Intensifiers and reflexives in Germanic languages. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203966181Suche in Google Scholar

Givón, Talmy. 2001. Syntax: An introduction, vol. 1. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/z.syn2Suche in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 2006. Constructions at work: The nature of generalization in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268511.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Gómez Torrego, Leonardo. 1992. Valores gramaticales de “se”. Madrid: Arco libros.Suche in Google Scholar

González Vergara, Carlos. 2006. Las construcciones no reflexivas con “se”: una propuesta desde la Gramática del Papel y la Referencia. Madrid: Complutense University of Madrid dissertation.10.7764/onomazein.14.03Suche in Google Scholar

González Vergara, Carlos. 2014. Las oraciones reflexivas con se del español. Una propuesta desde la Gramática del Papel y la Referencia. Signo y Seña 25. 133–158.Suche in Google Scholar

Grimshaw, Jane. 1990. Argument structure. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Haspelmath, Martin. 2003. The geometry of grammatical meaning: Semantic maps and cross-linguistic comparison. In Michael Tomasello (ed.), The new psychology of language, vol. 2, 211–243. New York: Erlbaum.Suche in Google Scholar

Haspelmath, Martin. 2008. Parametric versus functional explanations of syntactic universals. In Theresa Biberauer (ed.), The limits of syntactic variation, 75–107. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/la.132.04hasSuche in Google Scholar

Hoffmann, Thomas & Graeme Trousdale (eds.). 2013. The Oxford handbook of construction grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195396683.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Hundt, Marianne. 2004. Animacy, agentivity, and the spread of the progressive in Modern English. English Language and Linguistics 8(1). 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1360674304001248.Suche in Google Scholar

König, Ekkehard & Volker Gast (eds.). 2008. Reciprocals and reflexives: Theoretical and typological explorations. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110199147Suche in Google Scholar

König, Ekkehard & Peter Siemund. 2000. Intensifiers and reflexives: A typological perspective. In Zygmunt Frajzyngier & Traci Curl (eds.), Reflexives: Forms and functions, 41–74. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.40.03konSuche in Google Scholar

König, Ekkehard, Peter Siemund & Stephan Töpper. 2013. Intensifiers and reflexive pronouns. In Matthew Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), The World Atlas of Language Structures online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. https://wals.info/chapter/47 (accessed 17 June 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George. 1966. Stative adjectives and verbs in English. In Anthony G. Oettinger (ed.), Mathematical linguistics and automatic translation. Report NSF-17, vol. I, 1–16. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.Suche in Google Scholar

Lang, Mervyn. 1990. Formación de palabras en español. Madrid: Cátedra.Suche in Google Scholar

Levin, Beth. 2009. The lexical semantics of verbs II: Aspectual approaches to lexical semantic representation. Handout, Stanford University. https://web.stanford.edu/%7Ebclevin/courses.html (accessed 8 April 2019).Suche in Google Scholar

Lidz, Jeffrey L. 1996. Dimensions of reflexivity. Newark, DE: University of Delaware dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Maldonado, Ricardo. 1999. A media voz. Problemas conceptuales del clítico se. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.Suche in Google Scholar

Mendikoetxea, Amaya. 1999. Construcciones con se: Medias, pasivas e impersonales. In Ingacio Bosque & Violeta Demonte (eds.), Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española, 1575–1630. Madrid: Espasa.Suche in Google Scholar

Montes Giraldo, José. 2003. El “se” del español y sus problemas. Estudios Filológicos 38. 121–137.10.4067/S0071-17132003003800008Suche in Google Scholar

Mutz, Katrin. 2003. Le parole complesse in ‘auto’ nell’italiano di oggi. In Nicoletta Maraschio & Teresa Poggi Salani (eds.), Italia linguistica anno Mille. Italia linguistica anno Duemila. Atti del XXXIV Congresso internazionale di studi della Società di linguistica italiana (SLI), 649–664. Rome: Bulzoni.Suche in Google Scholar

Mutz, Katrin. 2011. AUTO- and INTER- versus (?) SE: Remarks on interaction and competition between word formation and syntax. In Andreas Nolda & Oliver Teuber (eds.), Syntax and morphology multidimensional, 239–258. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110238754.239Suche in Google Scholar

Orqueda, Verónica & Karem Squadrito. 2017. Reflexivos e intensificadores en las formaciones con auto-: perspectiva histórica. Boletín de Filología 52(2). 147–162. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-93032017000200147.Suche in Google Scholar

Orqueda, Verónica, Francisca Toro, & Silvana Arriagada. Forthcoming. Análisis diacrónico de la categoría morfológica de auto-. In Ramón Zacarías Ponce de León & Anselmo Hernández Quiroz (eds.), Ámbitos morfológicos. Descripciones y métodos. México: Instituto de investigaciones filológicas.Suche in Google Scholar

RAE [Real Academia Española] & ASALE [Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española]. 2005. Entrenar(se). Diccionario panhispánico de dudas. https://www.rae.es/recursos/diccionarios/dpd (accessed 17 June 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

RAE [Real Academia Española] & ASALE [Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española]. 2010. Nueva gramática de la lengua española. Manual. Madrid: Espasa.Suche in Google Scholar

Rooryck, Johan & Guido Vanden Wyngaerd. 2011. Dissolving binding theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199691326.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs & Graeme Trousdale. 2013. Constructionalization and constructional changes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199679898.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2015. Toward a coherent account of grammatical constructionalization. In Jóhanna Barðdal, Elena Smirnova, Lotte Sommerer & Spike Gildea (eds.), Diachronic Construction Grammar, 51–79. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/cal.18.02traSuche in Google Scholar

Trousdale, Graeme. 2010. Issues in constructional approaches to grammaticalization in English. In Katerina Stathi, Elke Gehweiler & Ekkehard König (eds.), Grammaticalization: Current views and issues, 51–72. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.119.05troSuche in Google Scholar

Tsunoda, Tasaku. 1981. Split case-marking patterns in verb-types and tense/aspect/mood. Linguistics 19(5–6). 389–438. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1981.19.5-6.389.Suche in Google Scholar

Tsunoda, Tasaku. 1999. Transitivity and intransitivity. Journal of Asian and African Studies 57. 1–9.Suche in Google Scholar

Van Valin, Robert. 2001. An introduction to syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139164320Suche in Google Scholar

Varela Ortega, Soledad. 2005. Morfología léxica: la formación de palabras. Madrid: Gredos.Suche in Google Scholar

Verhoeven, Elisabeth. 2010. Agentivity and stativity in experiencer verbs: Implications for a typology of verb classes. Linguistic Typology 14(2–3). 213–251. https://doi.org/10.1515/lity.2010.009.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2020 Verónica Orqueda et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Predicative possession across Western Iranian languages

- Nasality in Dagbani prosody

- Variable D-marking on proper naming expressions: A typological study

- Dogon reported discourse markers: The Ben Tey quotative topicalizer

- Spanish [auto + V + se] constructions

- Datives with psych nouns and adjectives in Basque

- Folklore as an evidential category

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Predicative possession across Western Iranian languages

- Nasality in Dagbani prosody

- Variable D-marking on proper naming expressions: A typological study

- Dogon reported discourse markers: The Ben Tey quotative topicalizer

- Spanish [auto + V + se] constructions

- Datives with psych nouns and adjectives in Basque

- Folklore as an evidential category