Abstract

The PARSEME GRC guidelines distinguish between Light-Verb Constructions, such as to make a suggestion, and Verbal Idioms, such as to kick the bucket. Light-Verb Constructions need to contain a nominal element that is abstract and predicative. Verbal Idioms are lexically, morphologically, morphosyntactically, and syntactically inflexible. Syntactic nominalisations as the nominal element are usually disregarded especially in Light-Verb Constructions due to their structural and functional ambiguity. (Post)classical Greek has productive morpho-syntactic means for the nominalisation of any part of speech which are not restricted e.g. diatopically or distratically, whereas lexical nominalisation by means of derivational morphology is more restricted. This makes the exclusion of syntactic nominalisations seem artificial. When considering the eventiveness of the nominal component the crucial characteristic it emerges that non-deverbal and underived event nouns, including syntactic nominalisations, can in fact be predicative nouns in verbal multi-word expressions. Syntactic nominalisations can appear as predicative nouns in Light-Verb Constructions along with forming part of Verbal Idioms. Synchronically, verbal multi-word expressions containing a syntactic nominalisation can be gap fillers, indexical alternatives, or semantico-pragmatic alternatives to structures with a lexical nominalisation. The study is primarily based on the PARSEME GRC and ECF Leverhulme Sketch Engine corpora of literary classical Attic philosophical prose, historiography, and oratory.

1 Introduction

Structures such as kick the bucket, spill the beans, take a picture, and pay attention are verbal multi-word expressions, lexically speaking. Multiple lexemes form the verb phrase (Nagy et al. 2013; Savary et al. 2018). However, the three examples provided differ as regards their structural analysability, i.e. to what extent each component can be modified separately from the rest of the phrase, and semantic compositionality, i.e. to what extent the meaning of the parts can be deduced from the meaning of the whole (Ledgeway and Vincent 2022, 51).

Kick the bucket is non-analytic and non-compositional (Evert 2009). Spill the beans is non-analytic and non-compositional but the meaning of the expression is transparent, i.e. the meaning of the expression can be recovered from its parts (Sheinfux et al. 2019, 42). Take a picture is analytic and compositional if reconceptualisation of the noun is accepted as compositional, i.e. picture does not refer to the concrete object but to the process resulting in the object (Radimský 2011). Pay attention is analytic and compositional if abstraction of the verb is accepted as compositional, i.e. pay has the meaning of direct rather than hand over (Heine 2020).

Verbal multi-word expressions are ubiquitous in all text types of Greek, both classical (5th/4th c. BC) and postclassical (ca. 3rd c. BC to 7th c. AD). However, unlike in many spoken languages (and Latin!)[1] in which dictionaries and grammar books cover verbal multi-word expressions, for (post)classical Greek they are often thought of as idioms, as collocations, or as prose phrases (see the standard dictionary Liddell-Scott-Jones). None of these conceptualisations captures all the relevant examples. Their misunderstanding can have a far reaching impact on the interpretation of the narratological context, the creation process of the work, or the Sitz im Leben of the text (Fendel 2024b, 331–336 for three worked examples across periods of time). Three desiderata for (post)classical Greek are suitably large corpora annotated for verbal multi-word expression, their representation as such in dictionaries, and their coverage in grammar books (see Fendel 2024b, 328–331 in detail). PARSEME offers a framework to achieve this.

In frameworks where compositionality is conceptualised as categorical and transparency is dismissed, only take a picture and pay attention would qualify as compositional (Mel’čuk 2023, 29 and 32). In frameworks in which additionally constraints are placed on the noun, i.e. it must be abstract and predicative, only pay attention would qualify. The PARSEME 1.3 guidelines used to annotate the PARSEME Ancient Greek corpus are such a framework.[2]

PARSEME is a Natural-Language-Processing initiative, which is currently part of the UniDive Working group 1 Corpus annotation.[3] Its core aim is the consistent annotation of large corpora for verbal multi-word expressions in order to train language models. Subsequent corpus releases have increased the coverage for singular languages and the number of languages and varieties represented. The latest release (PARSEME 1.3) is accessible here: https://lindat.mff.cuni.cz/repository/xmlui/handle/11372/LRT-5124. The corpus can be searched by means of GrewMATCH (https://parseme.grew.fr/?corpus=PARSEME-PL@1.3).

The universal annotation guidelines are accessible here (GRC for Ancient Greek): https://parsemefr.lis-lab.fr/parseme-st-guidelines/1.3/index.php?page=home. These are synchronically focussed, fundamentally categorical, i.e. a structure is one or the other type of verbal multi-word expression, and lexically focussed, i.e. morphosyntactic, semantic, or pragmatic aspects are not annotated.

The PARSEME 1.3 guidelines exclude two types of structures that are closely related to those annotated and may synchronically and diachronically even qualify in certain cases, i.e. cognate-object constructions, e.g. to run a race (cf. Roesch 2018 on Latin), and constructions with a syntactic nominalisation rather than a lexical noun, e.g. to do good (Meinschaefer 2016; Marini 2018). They are annotated as NotMWE (not a multi-word expression) in the PARSEME Ancient Greek corpus, i.e. they were collected but fall outside of the scope of the guidelines. Yet what is their relationship with structures that fall into the annotation scope, primarily Light-Verb Constructions (LVCs) and Verbal Idioms (VIDs)?

Light-verb constructions (LVCs) are combinations of a verb and a noun in which the noun is abstract and predicative and the verb contributes either tense, aspect, and mood marking only (LVC.full) or causative semantics additionally (LVC.cause), e.g. διάβασιν ποιέομαι diabasin poieomai ‘to make the crossing/to cross’ versus διάβασιν παρέχω diabasin parekhō ‘to grant the crossing/to let (somebody) cross’. Light-verb constructions are fully analysable, formally, and compositional, functionally.

Verbal Idioms (VIDs) are lexically, morphologically, morphosyntactically, and syntactically inflexible. This inflexibility goes hand in hand with semantic non-compositionality. This includes structures that are transparent, i.e. the meaning of the whole can be recovered from the meaning of its parts e.g. when considering reconceptualisation (Radimský 2011), metaphorical extension (Sheinfux et al. 2019), or metonymy (Kraska-Szlenk 2014) for the noun. Thus, to beat about the bush (non-transparent, non-compositional), to spill the beans (transparent, non-compositional), to take heart (transparent, compositional with metaphorical extension), and to take a picture (transparent, compositional with reconceptualisation) all fall into this category. A Greek example is δεξιὰν δίδωμι dexian didōmi ‘to give a pledge/to pledge’. From the PARSEME perspective, the metaphorically extended or reconceptualised noun would qualify as a cranberry item, i.e. an item that is limited to a specific expression or context. The form-function pairing for picture = event of taking a picture and heart = courage is unique to the VID context.[4]

The article focusses on constructions with a syntactic nominalisation in the noun slot, e.g. πιστὰ δίδωμι pista didōmi ‘to give the trusted (i.e. pledges)’, yet provides some parallels to cognate-object constructions, e.g. ἁμάρτημα ἁρμαρτάνω hamartēma hamartanō ‘to make a mistake’, answering three research questions:

What is the difference between abstract, predicative, and eventive and what diagnostics can we use when annotating?

How do structures with a syntactic nominalisation differ from yet border onto verbal multi-word expressions (as per the PARSEME 1.3 guidelines), especially Light-Verb Constructions and Verbal Idioms?

Why did we integrate structures with a syntactic nominalisation (and cognate-object constructions) into the annotation scope for the PARSEME GRC corpus?

The data come primarily from the PARSEME Ancient Greek corpus (release 2024). Table 1 provides an overview.

Token counts in the PARSEME GRC corpus.

| Author, work | Total of verbal multi-word expressions (VMWEs) | Number of structures with a syntactic nominalisation in the predicative-noun slot (SynNom) (% of total) | Number of cognate-object constructions (COC) (% of total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysias, Speeches, 1, 3, 7, and 12 | 372 | 37 (10 %) | 36 (10 %) |

| Xenophon, Anabasis, 1–4 | 443 | 32 (7 %) | 46 (10 %) |

| Plato, Republic, 1–2 | 511 | 43 (8 %) | 44 (9 %) |

Table 1 shows that the structures of interest account for ca. 10 % of all verbal multi-word expressions annotated in each subsample. Additionally comparative samples are drawn using the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae and the ECF Leverhulme Sketch Engine corpus of literary classical Attic historiography, oratory, and philosophical prose (Fendel and Ireland 2023). Datasets are available here: DOI 10.5287/ora-4jvx7p56m.

The texts selected for analysis were selected for three reasons. Firstly, the selection was meant to align with the text type selection of other corpora of the PARSEME family, especially the modern Greek one, in order to allow for comparison. Lysias’ speeches are courtroom speeches, which due to the Athenian democracy being a direct democracy are not specifically formalised or technical in their language because they had to be comprehensible to the average person (Willi 2003, chap. 3; Fendel 2024a). Xenophon’s report is the report of a Greek mercenary army returning from a campaign in Persia to Greece. The journey is complicated by the fact that the person who had hired them (Cyrus) was killed in battle. Plato’s dialogue is an educated exchange between Socrates and his interlocutors about the issue of a constitution and political organisation. Its dialogic character makes it possible to observe the language of turn-taking and backchannelling, i.e. the dialogic asking for clarification or confirming comprehension at points such as English got it? (van Emde Boas 2022).[5] The data sample is not random partially due to the alignment with other PARSEME languages and partially because (post)classical Greek is a corpus language. For corpus languages, limited amounts of data are available and cannot be expanded (except by chance discoveries). The available data has undergone a preservation process that is not re-constructible in all cases and relies to a certain extent on chance (see also Hoffmann 2005, chap. 8). The last native speakers of such languages are the texts themselves (Fleischman 2000). While the present corpus selection thus provides a suitably large sample vis-à-vis available data with regard to classical Attic oratory, historiography, and philosophical prose (the traditional genre labels for the three texts selected), findings cannot be generalised to texts of different time periods, types, or from different places.

After this introductory section, Section 2 addresses research question one, Section 3 research question two, and Section 4 research question three. Section 5 summarises the results, draws conclusions, and provides an outlook for future work.

2 Abstract, Predicative, and Eventive

The PARSEME 1.3 decision tree for Light-Verb Constructions is headed by the questions: Is the noun abstract? Is the noun predicative? Abstractness is a lexical concept, predicativeness a syntactic one. The below reviews each concept but proposes eventiveness as the way forward for syntactic nominalisations in the predicative-noun slot (and cognate objects).

Whether or not a noun has an abstract meaning is often determined negatively, i.e. by ruling out that it has a concrete meaning. A concrete meaning is a meaning that has a tangible reference point in the real world, e.g. a reference to people (father),[6] animals (horse), places (market square), physical objects (chair), buildings (palace), and the like. This still leaves many meanings in the grey area.

Furthermore, many nouns in classical Greek do not move from nomen actionis (action noun) to nomen agentis (agent noun), along the path shown in (1), irreversibly but are polysemous.

| Nominal semantics (Panagl 2020, 394) |

| a. Nomen actionis → b. Nomen acti → c. Nomen rei → d. Nomen instrumenti → e. Nomen loci → f. Nomen agentis |

An example of such an item with concrete and abstract meanings is πρᾶγμα pragma. πρᾶγμα pragma additionally seems to have a meaning nuance that is limited to verbal multi-word-expression contexts, i.e. a cranberry form-function pairing. (2) provides an overview:

| πρᾶγμα pragma in Liddell-Scott-Jones (LSJ) |

| Concrete: ‘thing, creature’ (LSJ II.2) |

| Abstract: ‘occurrence, matter, affair; (plural) circumstances, affairs’ (LSJ II.[1] and 4–8, III.1–4) |

| Verbal multi-word expression: ‘trouble, annoyance’ (LSJ III.5) |

| – ἁπάντων αἰτίους τῶν π. [apantōn aitious tōn p.] Ar.Ach.310 [‘responsible for all trouble’]; |

| – πρήγματα ἔχειν [prēgmata ekhein], c. part., to have trouble about a thing, Hdt.7.147, cf. Pl.Tht.174b, etc.; |

| – π. λαμβάνειν [p. lambanein] [X.].Lac.2.9 [‘to get trouble’]; |

| – π. παρέχειν τινί [p. parekhein tini] to cause one trouble, Hdt.1.155, Ar.Pl.20, al.: c. inf., cause one the trouble of doing, Pl.Phd.115a, X.Cyr.4.5.46, Ar.V.313; |

| – πραγμάτων … ἀπαλλαγείς [pragmatōn … apallageis] [Ar.].Ach.269 (lyr.), cf. Pl.Ap.41d, R.406e [‘free(d) from trouble’]; |

| – ἄνευ πραγμάτων, σὺν πράγμασι [aneu pragmatōn, sun pragmasi], D.1.20, X.An.6.3.6 [‘without trouble, with trouble’]; |

| – less freq.in sg., μηδὲν πρῆγμα παρέχειν [mēden prēgma parekhein] Hdt.7.239 [‘to cause no trouble’]. |

πρᾶγμα pragma is derived by means of the suffix -μα -ma from the verbal root of πράσσω prassō ‘to do’. The suffix -μα -ma ‘forms neuter effect/result nouns’ (van Emde Boas et al. 2019, 265). However, as shown, the concrete effect/result meaning ‘thing’ is not the only meaning of πρᾶγμα pragma.[7] Only the meaning nuances ‘occurrence, matter, affair; (plural) circumstances, affairs’ and ‘trouble, annoyance’ pass the abstractness test. The cranberry form-function pairing is πράγματα pragmata (plural, often indefinite) ‘trouble, annoyrance’ in verbal multi-word expressions.

Whether or not a noun is predicative is determined in the PARSEME 1.3 guidelines by testing whether the noun has any arguments. These might be syntactic arguments, e.g. a subject, but also functional arguments that are syntactically attributes or adjuncts, e.g. an objective genitive (Croft 1991; Markantonatou and Samaridi 2017; Dalrymple et al. 2019). Thus, e.g. χάρις kharis ‘gratitude’ and ἐξέτασις exetasis ‘inspection’ are predicative as they can take a subject (in the form of a subjective genitive) and in the case of ἐξέτασις exetasis ‘inspection’ also an objective genitive, yet e.g. χειμών kheimōn ‘wintry, stormy weather’ would not qualify nor would κακά kaka ‘evil’ (a syntactic nominalisation) or ὁδός hodos ‘path’. PARSEME’s use of the term ‘predicative’ seems to conflate predicative in the syntactic sense and the semantic concept of eventiveness.

Predicative in the syntactic sense refers to elements that complement another element such that the elements form a complex predicate together. Complex predicates are monoclausal, i.e. they project into a single clause (Butt 2010). Classical Greek requires such predicative elements, i.e. nouns, adjectives, or participles, with copular verbs (εἶναι einai, γίγνομαι gignomai), as shown in (3):

| Predicative structures8 |

| κακόν ἐστί(ν) kakon esti(n) ‘it is bad’ |

| σπονδαί γίγνονται spondai gignontai ‘treaties happen/are made’ |

- 8

A related structure seems to be intransitive ‘to have’ + adverb, e.g. καλῶς ἔχει kalōs ekhei ‘it is good’. Jiménez López (2021) considers structures with γίγνομαι gignomai the lexical passive of ποιέομαι poieomai structures in parallel with the situation in modern Greek (conversely Fendel 2024a).

The predicative element agrees in case, number, and gender with the subject of the copular verb thus showing that the copular verb and the predicative element form a complex predicate. In possessive structures consisting of a copular verb + noun in the genitive/dative ‘to have (something)’ (Benvenuto and Pompeo 2015), the possessive genitive or dative functions as the predicative element.

The nominal element in a Light-Verb Construction completes the light verb in order to form a complex predicate (see Markantonatou and Samaridi 2017; Butt 2010). It can appear in the subject or object slot of the verb or the complement slot of a preposition, e.g. Xenophon, Anabasis, 2.2.19 τοῖς Ἕλλησι φόβος ἐμπίπτει tois hellenēsi phobos empiptei ‘fear befell the Greeks’, Xenophon, Anabasis, 6.5.29 φόβον παρεῖχε phobon pareikhe ‘it caused fear’, and Plato, Leges, 635c1 ὁπόταν εἰς ἀναγκαίους ἔλθῃ πόνους καὶ φόβους καὶ λύπας hopotan eis anagkaious elthē ponous kai phobous kai lupas ‘whenever he got into the necessary labour, fear, and grief’ (Mel’čuk 1996, 59–64; Tronci 2017 on Greek).

The nominal element is the main event reference as anaphora shows. Anaphora of a Light-Verb Construction can either be by resuming the noun (Xenophon, Anabasis, 1.7.1–2 ἐξέτασιν ποιεῖται exetasin poieitai ‘he is making an inspection’ resumed by ἐξέτασιν exetasin ‘inspection’) or by resuming the Light-Verb Construction as a whole (Xenophon, Anabasis, 4.6.20 σύνθημα ἐποιήσαντο sunthēma epoiēsanto ‘to make an agreement’ resumed by συνθέμενοι sunthemenoi ‘to agree’) but never by resuming the light verb only.[9] This shows that the predicative noun is the semantic pivot. Thus, the nominal component in a Light-Verb Construction needs to be eventive.

Eventive is a semantic concept. Grimshaw’s seminal categories of eventive nouns are shown in (4).

| Grimshaw’s event nouns (Meinschaefer 2016, 393): |

| Complex event noun |

| L’examination des dossiers par le conseil a eu lieu hier. |

| ‘The examination of the files by the board took place yesterday.’ |

| Simple event noun |

| Plusieurs examens ont eu lieu hier. |

| ‘Various exams took place yesterday.’ |

| Object/result noun |

| *Tous ces examens sur la table ont eu lieu hier. |

| ‘All these exams on the table took place yesterday.’ |

Complex event nouns describe an ongoing process, simple event nouns a completed event, and result nouns the outcome of an event without reference to the event.

Complex event nouns have an internal subject and object and simple event nouns an internal subject, like χάρις kharis ‘gratitude’ and ἐξέτασις exetasis ‘inspection’. When these appear in the noun slot of Light-Verb Constructions, they share the light verb’s subject component, which can take on any functional role, e.g. Volitional Undergoer or Agent (cf. Næss 2007). Thus, we test while annotating whether the semantic subject of the noun and the grammatical subject of the verb are co-referential.[10]

All of Grimshaw’s event nouns are lexical nominalisations (Meinschaefer 2016, 395) and deverbal. However, recent work by Bel et al. (2010, 46–47) suggests that there are non-deverbal event nouns in Spanish, e.g. accidente ‘accident’ and guerra ‘war’, which differ from Grimshaw’s categories in that they do not have an internal argument. κακά ‘evil’ may resemble these. Huyghe et al. (2017, 118) suggest that there are underived event nouns in French, e.g. crime ‘crime’, grève ‘strike’, repas ‘meal’, and orage ‘storm’, the eventive meaning of which ‘can be derived from a non-eventive meaning’ (similarly Radimský 2011).[11] χειμών ‘wintry, stormy weather’ and ὁδός ‘path’ may resemble these.

If event nouns can be non-deverbal and underived, this changes things for syntactic nominalisations (and cognate-object constructions) in the predicative-noun slot. In these, we often find non-deverbal, e.g. syntactic nominalisations of adjectives, and/or underived, e.g. nouns like meal and race, nominals. Both types of structures align with other verbal multi-word expressions in that the nominal component is (reconceptualised as) eventive (within the specific context of the structure).

According to the PARSEME 1.3 guidelines, structures with underived or non-deverbal event nouns that are lexically, morphologically, morphosyntactically, and syntactically inflexible would be classified as Verbal Idioms. Only those structures in which the nominal component passes the abstractness and predicativeness tests would qualify as Light-Verb Constructions.[12]

Structures with a syntactic nominalisation in the predicative-noun slot, e.g. πιστὰ δίδωμι pista didōmi ‘to give pledges’, (and cognate-object constructions, e.g. ἁμάρτημα ἁρμαρτάνω hamartēma hamartanō ‘to make a mistake’), may pass the abstractness and predicativeness tests. However, syntactic nominalisations in the predicative noun slot when inflected as neuter accusatives (singular and plural) come with the issue of ambiguity in that neuter accusatives can serve an adverbial function. Thus, one could read them as modifiers of the verb, e.g. κακὰ ποιέω kaka poieō ‘to treat badly’ rather than ‘to do evil’.

Regarding research question one (What is the difference between abstract, predicative, and eventive and what are the diagnostics when annotating?), we have seen that abstract is a lexical, predicative a syntactic, and eventive a semantic concept. Abstractness is often tested negatively, i.e. by ruling out references to people, places, and the like. Predicativeness can be tested by observing co-referentiality of the internal subject argument of the noun and the syntactic subject of the verb. The above suggests including underived and non-deverbal event nominals. If these pass the abstractness and predicativeness tests, the structure that they are part of may be a Light-Verb Construction, unless lexical, morphological, morphosyntactic, and syntactic flexibility can be tested to assess whether the structure is a Verbal Idiom.

3 LVC, VID, or NotMWE

Classical Greek has a productive, in the sense of generality (Barðdal 2008, 21), set of derivational morphology in order to derive nouns from adjectives, as shown in (5) and exemplified in (6):

| Deadjectival word-formation patterns (van Emde Boas et al. 2019, 263–268) |

| -εία -eia ‘feminine abstract nouns from third-declension adjectives in -ης [-ēs] are formed originally in -εια [-eia] (long α [a])’ |

| -ία -ia ‘forms abstract nouns denoting qualities or properties, from other nouns or from adjectives’ |

| -σύνη -sunē ‘forms a small number of abstract nouns, mostly from adjectives in -ως [-ōs], -ονος [-onos], especially -φρων [-phrōn] and -μων [-mōn]’ |

| -της, -τητος -tēs, tētos ‘forms feminine abstract nouns denoting qualities or properties, from adjectives in -ος [-os] or -υς [-us]; the general meaning is ‘the quality/property of being …’’ (my emphasis) |

| De-adjectival word formations |

| ἀληθής alēthēs – ἀλήθεια alētheia ‘true – truth’ |

| κακός kakos – κακία kakia ‘bad – badness’ & ἄπορος aporos – ἀπορία aporia ‘clueless – cluelessness’ |

| δίκαιος dikaios – διακαιοσύνη dikaiosunē ‘just – justice’ |

| κακός kakos – κακότης kakotēs ‘bad – badness’ |

Additionally, nouns can be derived from adjectives by means of syntactic nominalisation, which is equally productive. Syntactic nominalisation can be applied to the positive, comparative, and superlative of an adjective unlike derivational morphology.

Syntactic nominalisation of an adjective can be morpho-syntactically marked, by the addition of a determiner phrase, (7), but does not have to be, (8).

| τὸ κακόν to kakon ‘the evil, bad deed’ |

| κακόν kakon ‘(the) evil, bad deed’ |

Furthermore, vehicular contexts exist, e.g. the addition of an indefinite, (9), which can act as a pronoun or determiner, or the noun πρᾶγμα pragma ‘thing’, (10).[13]

| κακόν τι kakon ti ‘something bad, evil’ |

| πρᾶγμα κακόν pragma kakon ‘the bad, evil thing; something bad, evil’ |

The optional morpho-syntactic marking of nominalisations introduces ambiguity. Furthermore, the nominalised phrase in the neuter accusative can be interpreted as an adverb, compounding this ambiguity, e.g. μέγα mega ‘greatly’ instead of morphologically derived μεγάλως megalōs ‘greatly’ (van Emde Boas et al. 2019, 366). Finally, syntactic nominalisations, especially when inflected in the neuter, can refer to physical items or to circumstances and behaviours, which creates further ambiguity. Therefore, we need ambiguity-reducing contexts.

The three subsections below discuss (i) parallels between lexical and syntactic nominalisations in verbal multi-word expressions, (ii) the stative ἐν en [noun in the dative] ἔχω ekhō ‘to have in X’ frame in which the nominalisation appears in a case other than the accusative, and (iii) instances in which the light verb par excellence, ποιέομαι poieomai ‘to do’ in the middle voice, appears with a syntactic nominalisation.

3.1 πιστά pista versus δεξιά dexia versus πίστις pistis with δίδωμι didōmi in Xenophon’s Anabasis (VID, transparent vs. VID, non-transparent vs. LVC)

In Xenophon’s Anabasis, the army leaders repeatedly broker deals with the people whose area they cross. Thus, pledges are given and received and oaths are made. The giving and receiving of pledges can be expressed by means of the Verbal Idiom δεξιὰν/δεξιὰς δίδωμι/λαμβάνω dexian/dexias didōmi/lambanō ‘to give/receive pledge(s)’ (see in detail Fendel 2025a).[14] The phrase is lexically, morphosyntactically, and syntactically inflexible. There is limited morphological flexibility in that both the singular and plural forms of the noun appear in classical literary Attic historiography, oratory, and philosophical prose (ECF Leverhulme corpus).

The Verbal idiom co-occurs with the simplex verbs ἐπιορκέω epiorkeō and ὄμνυμι omnumi ‘to swear an oath’, which refer to the subsequent event, i.e. the oaths. The Verbal Idiom parallels in the discourse three times, (11)–(13), the phrase (τὰ) πιστὰ δίδωμι/λαμβάνω (ta) pista didōmi/lambanō ‘to give/receive pledges’. All three passages come from the PARSEME Ancient Greek corpus.[15]

| Xenophon, Anabasis, 3.2.4–5 |

| ἀλλ᾽ ὁρᾶτε μέν, ὦ ἄνδρες, τὴν βασιλέως ἐπιορκίαν καὶ ἀσέβειαν, ὁρᾶτε δὲ τὴν Τισσαφέρνους ἀπιστίαν, ὅστις λέγων ὡς γείτων τε εἴη τῆς Ἑλλάδος καὶ περὶ πλείστου ἂν ποιήσαιτο σῶσαι ἡμᾶς, καὶ ἐπὶ τούτοις αὐτὸς ὀμόσας ἡμῖν, αὐτὸς δεξιὰς δούς, αὐτὸς ἐξαπατήσας συνέλαβε τοὺς στρατηγούς, καὶ οὐδὲ Δία ξένιον ᾐδέσθη, ἀλλὰ Κλεάρχῳ καὶ ὁμοτράπεζος γενόμενος αὐτοῖς τούτοις ἐξαπατήσας τοὺς ἄνδρας ἀπολώλεκεν. Ἀριαῖος δέ, ὃν ἡμεῖς ἠθέλομεν βασιλέα καθιστάναι, καὶ ἐδώκαμεν καὶ ἐλάβομεν πιστὰ μὴ προδώσειν ἀλλήλους, καὶ οὗτος οὔτε τοὺς θεοὺς δείσας οὔτε Κῦρον τεθνηκότα αἰδεσθείς, τιμώμενος μάλιστα ὑπὸ Κύρου ζῶντος (…) |

| all᾽ horate men, ō andres, tēn basileōs epiorkian kaì asebeian, horate de tēn Tissaphernous apistian, hostis legōn hōs geitōn te eiē tēs Hellados kai peri pleistou an poiēsaito sōsai hēmas, kai epi toutois autos omosas hēmin, autos dexias dous , autos exapatēsas sunelabe tous stratēgous, kai oude Dia xenion ēdesthē, alla Klearkhō kai homotrapezos genomenos autois toutois exapatēsas tous andras apolōleken. Ariaios de, hon hēmeis ēthelomen basilea kathistanai, kai edōkamen kai elabomen pista mē prodōsein allēlous, kai houtos oute tous theous deisas oute Kuron tethnēkota aidestheis, timōmenos malista hupo Kurou zōntos (…) |

| ‘However, look at, men, the perjury and impiety of the King and look at the disloyalty of Tissaphernes, who said that he was a neighbour of Greece and was most keen to save us, and he himself swore on these things to us, and having given pledges, he deceived (us) and took the generals and was not even fear Zeus Xenios, but he sat at the table with Clearchus, and through this he deceived and killed the men. Ariaius, whom we wanted to make king, gave and received pledges not to betray each other, and this man feared neither the gods nor paid tribute to Cyrus, who was dead, although he was most honoured by Cyrus while he was alive (…).’ |

| Xenophon, Anabasis, 1.6.6 |

| τοῦτον γὰρ πρῶτον μὲν ὁ ἐμὸς πατὴρ ἔδωκεν ὑπήκοον εἶναι ἐμοί: ἐπεὶ δὲ ταχθείς, ὡς ἔφη αὐτός, ὑπὸ τοῦ ἐμοῦ ἀδελφοῦ οὗτος ἐπολέμησεν ἐμοὶ ἔχων τὴν ἐν Σάρδεσιν ἀκρόπολιν, καὶ ἐγὼ αὐτὸν προσπολεμῶν ἐποίησα ὥστε δόξαι τούτῳ τοῦ πρὸς ἐμὲ πολέμου παύσασθαι, καὶ δεξιὰν ἔλαβον καὶ ἔδωκα, μετὰ ταῦτα, ἔφη, Ὀρόντα, ἔστιν ὅ τι σε ἠδίκησα; ἀπεκρίνατο ὅτι οὔ. πάλιν δὲ ὁ Κῦρος ἠρώτα: οὐκοῦν ὕστερον, ὡς αὐτὸς σὺ ὁμολογεῖς, οὐδὲν ὑπ᾽ ἐμοῦ ἀδικούμενος ἀποστὰς εἰς Μυσοὺς κακῶς ἐποίεις τὴν ἐμὴν χώραν ὅ τι ἐδύνω; ἔφη Ὀρόντας. οὐκοῦν, ἔφη ὁ Κῦρος, ὁπότ᾽ αὖ ἔγνως τὴν σαυτοῦ δύναμιν, ἐλθὼν ἐπὶ τὸν τῆς Ἀρτέμιδος βωμὸν μεταμέλειν τέ σοι ἔφησθα καὶ πείσας ἐμὲ πιστὰ πάλιν ἔδωκα μοι καὶ ἔλαβες παρ᾽ ἐμοῦ; |

| touton gar prōton men ho emos patēr edōken hupēkoon einai emoi: epei de takhtheis, hōs ephē autos, hupo tou emou adelphou houtos epolemēsen emoi ekhōn tēn en Sardesin akropolin, kai egō auton prospolemōn epoiēsa hōste doxai toutō tou pros eme polemou pausasthai, kai dexian elabon kai edōka , meta tauta, ephē, Oronta, estin ho ti se ēdikēsa? apekrinato hoti ou. palin de ho Kuros ērōta: oukoun husteron, hōs autos su homologeis, ouden hup᾽ emou adikoumenos apostas eis Musous kakōs epoieis tēn emēn khōran ho ti edunō? ephē Orontas. oukoun, ephē ho Kuros, hopot᾽ au egnōs tēn sautou dunamin, elthōn epi ton tēs Artemidos bōmon metamelein te soi ephēstha kai peisas eme pista palin edōkas moi kai elabes par᾽ emou? |

| ‘For my father first gave me this man to be my subordinate. When he had been ordered by my brother, as he said himself and was waging war against me occupying the citadel of Sardis, and I attacked him and achieved that it seemed best to him to stop the war against me, and I gave and received assurance. After this, Orontas, he said, is there anything that I have done wrong against you? He answered no. Cyrus asked again: Did you not later after suffering no wrong under me, as you agree yourself, desert (me) for the Mysians and treat my country as badly as you could? Orontas said yes. Did you now, said Cyrus, when you realised again your own power, go to Artemis’ altar and said that you felt repentance and convinced me and gave to me and received from me assurance again?’ |

| Xenophon, Anabasis, 2.3.26–28 |

| Καὶ νῦν ἔξεστιν ὑμῖν πιστὰ λαβεῖν παρ’ ἡμῶν ἦ μὴν φιλίαν παρέξειν ὑμῖν τὴν χώραν καὶ ἀδόλως ἀπάξειν εἰς τὴν Ἑλλάδα ἀγορὰν παρέχοντας· ὅπου δ’ ἂν μὴ ᾖ πρίασθαι, λαμβάνειν ὑμᾶς ἐκ τῆς χώρας ἐάσομεν τὰ ἐπιτήδεια. ὑμᾶς δὲ αὖ ἡμῖν δεήσει ὀμόσαι ἦ μὴν πορεύσεσθαι ὡς διὰ φιλίας ἀσινῶς σῖτα καὶ ποτὰ λαμβάνοντας ὁπόταν μὴ ἀγορὰν παρέχωμεν, ἐὰν δὲ παρέχωμεν ἀγοράν, ὠνουμένους ἔξειν τὰ ἐπιτήδεια. Ταῦτα ἔδοξε, καὶ ὤμοσαν καὶ δεξιὰς ἔδοσαν Τισσαφέρνης καὶ ὁ τῆς βασιλέως γυναικὸς ἀδελφὸς τοῖς τῶν Ἑλλήνων στρατηγοῖς καὶ λοχαγοῖς καὶ ἔλαβον παρὰ τῶν Ἑλλήνων. |

| Kai nun exestin humin pista labein par’ hēmōn ē mēn philian parekhein humin tēn khōran kai adolōs apakhein eis tēn hellada agoran parekhontas: hopou d’ an mē ē priasthai lambanein humas ek tēs khōras easomen ta epitēdeia. Humas de au hēmin deēsei omosai ē mēn poreusesthai hōs dia philias asinōs sita kai pota lambanontas hopotan mē agoran parekhōmen ean de parekhōmen agora ōnoumenous ekhein ta epitēdeia. Tauto edoxe, kai ōmosan kai dexias edosan Tissaphernēs kai ho tēs basileōs gunaikos adelphos tois tōn hellēnōn stratēgois kai lokhagois kai elabon para tōn hellēnōn. |

| ‘And now it is possible for you to receive pledges from us to provide a friendly country to you and lead (you) to Greece unharmed while giving (you) a market. Wherever it is not possible to buy (provisions), we will let you take provisions from the country. Yet you in turn must swear to us to proceed like through a friendly (country) without harm while taking food and drink only when we do not provide a market, but if we provide a market, to get provisions by buying (them). This seemed good, and they swore (oaths) and gave pledges, Tissaphernes and the king’s wife’s brother to the generals of the Greeks and the captains, and they received (pledges) from the Greeks.’ |

The lexical noun δεξιά dexia ‘right hand, (in multi-word expressions:) pledge, assurance’ is replaced by the syntactic nominalisation (τὰ) πιστὰ (ta) pista ‘trustworthy, loyal things’. This makes the structure transparent.

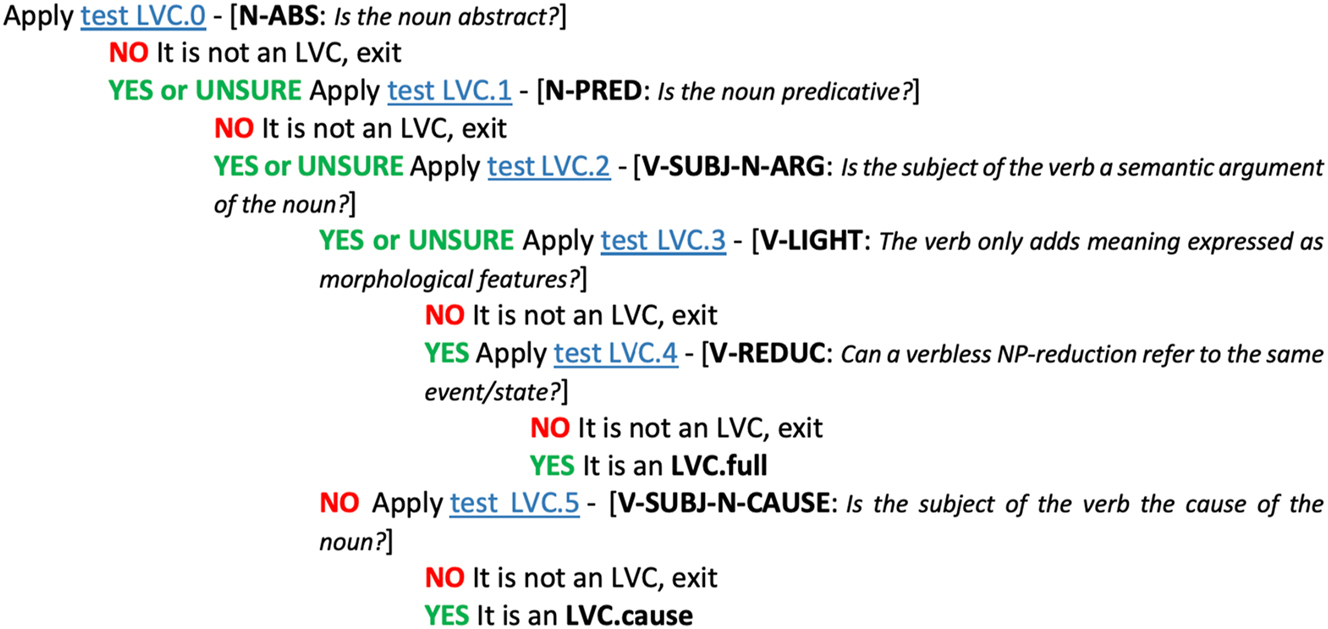

(τὰ) πιστὰ (ta) pista ‘trustworthy, loyal things’ passes the abstractness and predicativeness tests (N-ABS and N-PRED) in the PARSEME Light-Verb-Construction decision tree shown in Figure 1 if we assume that it does not refer to ‘things’ but ‘circumstances, behaviour’. This is within the semantic scope of the nominalisation.

Light-verb construction decision tree in PARSEME 1.3 (source: https://parsemefr.lis-lab.fr/parseme-st-guidelines/1.3/index.php?page=050_Cross-lingual_tests/020_Light-verb_constructions__LB_LVC_RB_).

However, contexts such as (14) show the remaining ambiguity. In (14), βαρβαρικὴν λόγχην barbarikēn logkhēn and Ἑλληνικήν (λόγχην) hellēnikēn (logkhēn) could be read as a concrete specification of the abstract event of assurance or as specifications of the concrete object ‘trustworthy/trust-inducing things’.

| Xenophon, Anabasis, 4.8.6–7 |

| οἱ δ’ ἀπεκρίναντο Ὅτι καὶ ὑμεῖς ἐπὶ τὴν ἡμετέραν χώραν ἔρχεσθε. λέγειν ἐκέλευον οἱ στρατηγοὶ ὅτι οὐ κακῶς γε ποιήσοντες, ἀλλὰ βασιλεῖ πολεμήσαντες ἀπερχόμεθα εἰς τὴν Ἑλλάδα, καὶ ἐπὶ θάλατταν βουλόμεθα ἀφικέσθαι. ἠρώτων ἐκεῖνοι εἰ δοῖεν ἂν τούτων τὰ πιστά. οἱ δ’ ἔφασαν καὶ δοῦναι καὶ λαβεῖν ἐθέλειν. Ἐντεῦθεν διδόασιν οἱ Μάκρωνες βαρβαρικὴν λόγχην τοῖς Ἕλλησιν, οἱ δὲ Ἕλληνες ἐκείνοις Ἑλληνικήν· ταῦτα γὰρ ἔφασαν πιστὰ εἶναι· θεοὺς δ’ ἐπεμαρτύραντο ἀμφότεροι. |

| hoi d’ apekrinanto Hoti kai humeis epi tēn hēmeteran khōran erkhesthe. legein ekeleuon hoi stratēgoi hoti ou kakōs ge poiēsontes, alla basilei polemēsantes aperkhometha eis tēn Hellada, kai epi thalattan boulometha aphikesthai. ērōtōn ekeinoi ei doien an toutōn ta pista . hoi d’ ephasan kai dounai kai labein ethelein. Enteuthen didoasin hoi Makrōnes barbarikēn logkhēn toĩs Hellēsin, hoi de Hellēnes ekeinois Hellēnikēn; tauta gar ephasan pista einai ; theous d’ epemarturanto amphoteroi. |

| ‘They answered: Because you are coming against our country. The generals told (him) to say that: Not in order to do any harm but having been at war with the king we are returning to Greece, and we want to reach the sea. Those asked whether they would give pledges with regard to this. They said they wanted to give and receive (pledges). Then, the Macronians gave the Greeks a barbarian lance and the Greeks gave them a Greek one. They said that these are pledges. Both called the gods as witnesses.’ |

If the event reading applies, the syntactic nominalisation has an internal argument that is co-referential with the syntactic subject of the verb.[16] Only active ‘to receive pledges’ passes V-LIGHT.[17] Due to the ambiguity inherent in the syntactic nominalisation, V-REDUC is unlikely to be passed by the structure.[18] This would mean that we would have to qualify (τὰ) πιστὰ δίδωμι (ta) pista didōmi as a Verbal Idiom. It is indeed lexically and morphologically (the plural of the adjective is compulsory) inflexible.

While a de-adjectival noun from the root πείθ- peith- (full grade)[19] does not exist in classical times (apart from negative ἀπιστία apistia ‘disloyalty’), a deverbal event noun exists, i.e. πίστις pistis ‘assurance’, and appears in Light-Verb Constructions. Table 2 shows the support-verb-construction family around πίστις pistis ‘assurance’ in the ECF Leverhulme corpus (see Kamber 2008; Gross 1998).

πίστις pistis in the ECF Leverhulme Sketch Engine corpus.a

| Support verb | Singular (sg)/plural (pl) | Determiner phrase | Attributive phrase | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ἔχω ekhō ‘to have’ | sg | – | ADJ (1) | 2 |

| ἔχω ekhō ‘to have’ | pl | – | ADJ (2) | 2 |

| δίδωμι didōmi ‘to give’ | sg | – | ADJ, REL | 4 |

| δίδωμι didōmi ‘to give’ | pl | 2 | ADJ (3) | 6 |

| λαμβάνω lambanō ‘to receive’ | sg | – | – | 4 |

| λαμβάνω lambanō ‘to receive’ | pl | 4 | PP | 5 |

| ποιέομαι poieomai ‘to do’ | pl | 2 | – | 5 |

| φέρω pherō ‘to bring’ | pl | 2 | – | 2 |

| γίγνομαι gignomai ‘to become’ | pl | 2 | – | 2 |

| παρέχω parekhō ‘to provide’ | sg | – | – | 2 |

| VRel | sg | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| VRelb | pl | 2 | ADJ (1) | 2 |

| COC | pl | – | – | 2 |

-

aVRel = verb of realisation, COC = cognate-object construction, ADJ = adjective, REL = relative clause, PP = prepositional phrase. bAristotle, Rhetoric, 3.1417b21 (ἀποδεικνύναι apodeiknunai ‘to show’) object continuity; Demosthenes, Speech, 18.164 (παραβαίνων parabainōn ‘breaching’) terminative.

Table 2 shows that the candidates with ‘to give’ and ‘to take/receive’ which parallel the Verbal Idiom and the structure with a syntactic nominalisation are indeed Light-Verb Constructions and allow for morphological and morphosyntactic variation.

It thus appears that a Verbal Idiom, a Light-Verb Construction with a deverbal event noun, and a construction with a syntactically nominalised adjective co-exist. They seem to differ semantico-pragmatically. The Verbal Idiom does not allow for resumption of the nominal part only in subsequent discourse nor does it allow for lexical, morphosyntactic, or syntactic variation which limits its usefulness in building discourse coherence (cf. Fendel and Ireland 2023), e.g. by means of pronominalisation and anaphora. The Light-Verb Construction with a deverbal event noun allows for resumption of the nominal component only as well as for morphological, morphosyntactic, and syntactic variation and thus for building discourse coherence (see also Wittenberg and Trotzke 2021).

The construction with a syntactic nominalisation is compositional and transparent. It seems to stress the stative nature of the event due to the nominalised adjective in the predicative-noun slot. Thus, the construction with the syntactic nominalisation is by no means filling a lexical gap but by drawing on a productive syntactic process allows for further nuancing of meaning while preserving discursive advantages.[20] Under the PARSEME guidelines, it is a Verbal Idiom.[21]

3.2 ἐν en + [noun in the dative (ἄπορος aporos/ἀπορία aporia)] + ἔχω ekhō in the ECF Leverhulme Sketch Engine corpus (VID, transparent vs. LVC)

The Light-Verb Construction and the Verbal Idiom shown in Section 3.1 consist of a verb and a noun that is morpho-syntactically marked as the verb’s object. Yet Light-Verb Constructions and Verbal Idioms can also consist of a verb and a prepositional phrase with the (eventive) noun as the complement of the preposition, e.g. to hold X in high esteem.

A well-known Verbal Idiom of this type in classical literary Attic is περὶ πολλοῦ/πλείονος/πλείστου ποιέομαι peri pollou/pleionos/pleistou poieomai ‘to appreciate’. The combination of a preposition (περί peri), a nominalised adjective (πολλοῦ/πλείονος/πλείστου pollou/pleionos/pleistou), and the light verb par excellence (ποιέομαι poieomai in the middle voice) is morphologically (no pluralisation permissible), morphosyntactically (no determiner phrase permissible), and syntactically (only function words such as modal particles can intervene between the constituent parts, e.g. Lysias, Speech, 1.1) invariable (Fendel submitted).[22] The nominalised adjective appears in the genitive case such that we witness its role in the verbal multi-word expression without the ambiguity induced by nominalisations inflected as the accusative neuter.[23]

A frequently appearing multi-word-expression frame in classical Greek is the ἐν en + [noun in the dative] + ἔχω ekhō ‘to have (…) in X’ frame (see Tronci 2017; Fendel submitted). It can be transitive, e.g. ἐν νῷ ἔχω en nō ekhō + accusative ‘to have X in mind’, or intransitive, ἐν ὀργῇ ἔχω en orgē ekhō ‘to be angry’. As the nominal component must appear in the dative case, we witness its role in the verbal multi-word expression without the ambiguity induced by nominalisations inflected as the accusative neuter. Two relevant structures with a syntactic rather than a lexical nominalisation appear in the ECF Leverhulme Sketch Engine corpus (Fendel submitted),[24] see (15) and (16):

| Thucydides, Histories, 1.80.4 |

| ἀλλὰ πολλῷ πλέον ἔτι τούτου ἐλλείπομεν καὶ οὔτε ἐν κοινῷ ἔχομεν οὔτε ἑτοίμως ἐκ τῶν ἰδίων φέρομεν. |

| alla pollō pleon eti toutou elleipomen kai oute en koinō ekhomen oute hetoimōs ek tōn idiōn pheromen. |

| ‘However, we still lack much more than this and neither do we communally own (it) nor do we bring it readily from private funds.’ |

| Thucydides, Histories, 1.25.1 |

| Γνόντες δὲ οἱ Ἐπιδάμνιοι οὐδεμίαν σφίσιν ἀπὸ Κερκύρας τιμωρίαν οὖσαν ἐν ἀπόρῳ εἴχοντο θέσθαι τὸ παρόν, καὶ πέμψαντες ἐς Δελφοὺς τὸν θεὸν ἐπήροντο εἰ παραδοῖεν Κορινθίοις τὴν πόλιν ὡς οἰκισταῖς καὶ τιμωρίαν τινὰ πειρῷντ᾽ ἀπ᾽ αὐτῶν ποιεῖσθαι. |

| gnontes de hoi Epidamnioi oudemian sphisin apo Kerkuras timōrian ousan en aporō eikhonto thesthai to paron, kai pempsantes es Delphous ton theon epēronto ei paradoien Korinthiois tēn polin hōs oikistais kai timōrían tina peirōnt᾽ ap᾽ autōn poieisthai. |

| The Epidaimonians, when they realised that there was no retribution for them from Corcyra, were clueless what to do now, and having sent (messengers) to Dephi they asked the god whether they should give the city to the Corinthians in order that they try to take some revenge on the founders. |

(15) is ambiguous as the prepositional phrase could be read as adverbial and the verb ἔχω ekhō can express possession when lexical. Conversely, in (16), ἔχω ekhō is a light verb, inflected in the middle voice, and the Light-Verb Construction has an infinitival complement.

Parallel formations with a deadjectival noun exist for (16), e.g. Plato, Gorgias, 522a9 Οὐκοῦν οἴει ἐν πάσῃ ἀπορίᾳ ἂν αὐτὸν ἔχεσθαι ὅτι χρὴ εἰπεῖν; oukoun oiei en pasē aporia an auton ekhesthai hoti khrē eipein ‘Do you not think that he would be completely clueless as to what he needs to say?’. Lemma-based proximity searches in the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae show a distributional difference between structures with derivationally derived ἀπορία aporia ‘cluelessness’, Table 4, and syntactically nominalised ἄπορος aporos ‘clueless’, Table 3.

ἐν en – ἄπορος aporos – ἔχω ekhō (Thesaurus Linguae Graecae lemma-based proximity search, distance of 5 words).a

| Prose | Verse | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AG (pre 5th c. BC) | – | – | – |

| CG (5th/4th c. BC) | 1 | – | 1 |

| PG (3rd – 1st c. BC) | – | – | – |

| RG (1st – 3rd. c. AD) | 2 | – | 2 |

| EBG (4th – 7th c. AD | 5 (Procopius quotes Thucydides but with active verb; Asterius quotes Thucydides) | – | 5 |

| MG (post 7th c. AD) | 7 (Constantius quotes Thucydides; Joannes quotes Lucian; Lexicon quotes Thucydides; Laonicus seemingly quotes Cassius Dio) | – | 7 |

-

aAG = Archaic Greek; CG = Classical Greek; HG = Hellenistic Greek; RG = Roman Greek; EBG = Early Byzantine Greek; MG = Medieval Greek.

The phrase with the syntactic nominalisation appears first in Thucydides’ Histories (CG), (16) above, and subsequently in Lucian’s Verae historiae (2.42.6) (RG) and Cassius Dio’s Historiae Romanae (50.31.5) (RG). All three seemingly independent instances appear in historiography such that we may observe a genre-specific form. After the Roman period, the phrase is limited to quotes of the aforementioned, such that instances are not independent and formed in the living language. However, note that e.g. Procopius seems to still be able to analyse the phrase as is obvious from his updating the voice of the verb from the middle to the active in his quote of Thucydides (on the decline of the middle, see Lavidas 2009; Vives Cuesta and Acero 2022).

Conversely, the Light-Verb Construction with the lexical nominalisation appears throughout classical Ionic historiography and Attic oratory and philosophical prose, Table 4.

ἐν en – ἀπορία aporia – ἔχω ekhō (Thesaurus Linguae Graecae lemma-based proximity search, distance of 5 words).a

| Prose | Verse | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AG (pre 5th c. BC) | – | – | – |

| CG (5th/4th c. BC) | 8 | – | 8 |

| PG (3rd – 1st c. BC) | – | – | – |

| RG (1st – 3rd. c. AD) | 2 | – | 2 |

| EBG (4th – 7th c. AD | 1 | – | 1 |

| MG (post 7th c. AD) | 5 | – | 5 |

-

aAG = Archaic Greek; CG = Classical Greek; HG = Hellenistic Greek; RG = Roman Greek; EBG = Early Byzantine Greek; MG = Medieval Greek.

The two Roman-period instances come from Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae and the early Byzantine instance from Stobaeus’ Anthologium. It seems that the phrase, while widespread in classical times, fell out of use and was preserved in encyclopaedic contexts.

By the PARSEME guidelines, the structure with a lexical nominalisation qualifies as a Light-Verb Construction passing all the tests. The structure with a syntactic nominalisation only passes the abstractness and predicativeness tests if we assume that the nominalisation refers to ‘circumstances, behaviour’ rather than ‘things’. Thus, ambiguity remains. Furthermore, the structure with the syntactic nominalisation seems invariable lexically, morphologically (always singular), morphosyntactically (no determiner phrase), syntactically (continuous except for enclitic τε te in Cassius Dio (RG) and Laconicus (MG) and μέν men in Asterius (EBG)). Thus, we qualify the structure with a lexical noun as a Light-Verb Construction but the structure with a syntactic nominalisation as a Verbal Idiom. Noticeably, the latter seems to be genre- and register-specific (Fendel 2024a, 2025b, 2025c).

3.3 Syntactic nominalisation + ποιέομαι/ἐργάζομαι poieomai/ergazomai in the ECF Leverhulme corpus (Test Sample)

The ECF Leverhulme corpus was constructed primarily to examine lexical nominalisations within verb-object type verbal multi-word expressions. In the 100,000-word Test Sample,[25] syntactic nominalisations of this type were manually annotated. These are the focus of the present study.

In the corpus, the following verbs were classified as support verbs (note the wider definition rather in line with Gross (1998) than with PARSEME): ἄγω agō ‘to pass/spend’, δέχομαι dekhomai ‘to receive’, δίδωμι didōmi ‘to give’, ἔχω ekhō ‘to have’, κομίζω komizō ‘to give/receive’, κτάομαι ktaomai ‘to gain’, λαμβάνω lambanō ‘to take/receive’, παρέχω parekhō ‘to give’, πάσχω paskhō ‘to suffer’, ποιέομαι poieomai ‘to do’, τίθημι tithēmi ‘to put’, τυγχάνω tugkhanō ‘to (happen to) get’, φέρω pherō ‘to bring’, and χράομαι khraomai ‘to use’ (Fendel 2025a). Due to frequency, the doing verbs ἐργάζομαι ergazomai, πράσσω prassō, and πλάσσω plassō ‘to do, achieve, accomplish’ did not qualify. All other verbs were considered verbs of realisation, i.e. ‘des verbes collocationnels qui ont le comportement syntaxique des Vsupp, mais qui, à la différence de ceux-ci, sont sémantiquement pleins’ (Mel’čuk 2004, 208).[26]

Table 5 shows instances with a determiner phrase, those with a determiner and an attributive phrase, and those with a direct object, split by support verb and verbs of realisation.

ECF Leverhulme corpus, test sample, syntactic nominalisations in the predicative-noun slot.a

| Type | Verbal lemma | Nominal lemma | DP | DP + ATT | Direct object |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SV | ἔχω ekhō (36) ‘to have’ | 11.5 | 17 | 2 | n/a |

| SV | ποιέω poieō (40.5) ‘to do’ | 14.66 | 22 | 3 | 9 |

| SV | ποιέομαι poieomai (3) ‘to do’ | 3 | 3 | 2 | n/a |

| SV | δίδωμι didōmi (2) ‘to give’ | 1 | 1 | 1 | n/a |

| SV | κομίζομαι komizomai (1) ‘to bring’ | 1 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| SV | κτάομαι ktaomai (1) ‘to gain’ | 1 | 1 | 0 | n/a |

| SV | λαμβάνω lambanō (3) ‘to take, to receive’ | 2 | 1 | 1 | n/a |

| SV | παρέχω parekhō (1) ‘to give’ | 1 | 1 | 0 | n/a |

| SV | πάσχω paskhō (26.5) ‘to suffer’ | 8 | 10 | 1 | n/a |

| SV | τυγχάνω tugkhanō (1) ‘to get’ | 1 | 1 | 0 | n/a |

| VRel | πράσσω prassō (20) ‘to do’ | 9.5 | 11 | 0 | n/a |

| VRel | δράω draō (1) ‘to do, accomplish’ | 1 | 1 | 0 | n/a |

| VRel | ἐργάζομαι ergazomai (10) ‘to do, achieve’ | 5 | 8 | 4 | 5 |

| VRel | εὑρίσκομαι heuriskomai (1) ‘to find’ | 1 | 1 | 0 | n/a |

| VRel | συνέχομαι sunekhomai (1) ‘to have (with)’ | 1 | 1 | 0 | n/a |

| VRel | Other (53) | 16 | 19 | 3 | n/a |

| Total | 202 | n/a | 98 | 17 | 14 |

-

aInstances in which multiple nouns or multiple verbs appear are counted as fractions (e.g. 0.5 when two verbs appear, and 0.33 when three verbs appear). This is why fractions appear in the table.

In Sections 3.1 and 3.2, we qualified the structures with syntactic nominalisations as Verbal Idioms. Yet can structures with syntactic nominalisations also be Light-Verb Constructions? We are interested in ambiguity-reducing contexts, i.e. instances with a determiner phrase and with a prototypical light verb (verbs meaning ‘to do, to make’). This leaves three relevant pairings, with relevant instances shown in (17) to (19):

| Lysias, Speech, 12.69 |

| ὑμεῖς δέ, ὦ ἄνδρες Ἀθηναῖοι, πραττούσης μὲν τῆς ἐν Ἀρειoπάγῳ βουλῆς σωτήρια,ἀντιλεγόντων δὲ πολλῶν Θηραμένει, εἰδότες δὲ ὅτι οἱ μὲν ἄλλοι ἄνθρωποι τῶν πολεμίων ἕνεκα τἀπόρρητα ποιοῦνται, ἐκεῖνος δ᾽ ἐν τοῖς αὑτοῦ πολίταις οὐκ ἠθέλησεν εἰπεῖν ταῦθ᾽ ἃ πρὸς τοὺς πολεμίους ἔμελλεν ἐρεῖν, ὅμως ἐπετρέψατε αὐτῷ πατρίδα καὶ παῖδας καὶ γυναῖκας καὶ ὑμᾶς αὐτούς. |

| humeis de, ō andres Athēnaioi, prattousēs men tēs en Areiopagō boulēs sōtēria,antilegontōn de pollōn Thēramenei, eidotes de hoti hoi men alloi anthrōpoi tōn polemiōn heneka taporrhēta poiountai , ekeinos d᾽ en tois hautou politais ouk ēthelēsen eipein tauth᾽ ha pros tous polemious emellen erein, homōs epetrepsate autō patrida kai paidas kaì gunaikas kai humas autous. |

| ‘And you, men of Athens, while the council of the Areopagus were arranging safety, and while many spoke against Theramenes, knew that others keep secrets because of the enemy, he did not want to say this which he was about to say to the enemy amongst his own citizens, nonetheless you turned over to him fatherland, children, wives, and yourselves.’ |

In (17), ποιέω poieō inflected in the middle voice combines with τὰ ἀπόρρητα ta aporrēta (in crasis in (17)) ‘the secrets’ (LSJ A.II). Lexical nominalisations from the same root exist, namely ἀπόρρησις aporrēsis ‘forbidding’ and ἀπόρρημα aporrēma ‘prohibition’, yet noticeably with different meanings. Lemma-based proximity searches in the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae reveal that ἀπόρρησις aporrēsis appears in combination with ποιέομαι poieomai only sporadically from postclassical times onwards (Aelius Aristides, Peri tou pempein boētheian tois en Sikelia, 374.30 and Scholia in Homerum) and ἀπόρρημα aporrēma not at all.[27] Conversely, the structure with a syntactic nominalisation shown in (17) appears throughout classical literature in Attic and Ionic (Herodotus, Histories, 9.45.3, Herodotus, Histories, 9.94.2, Aristophanes, Equites, l. 648, Plato, Leges, 932c8 (with negative), Lysias, In Eratosthenem, 69) and continues into postclassical times (Quintus Fabius Pictor, Fragments, 1.118). The structure is lexically, morphologically (always plural), and syntactically (always continuous) inflexible and thus qualifies as a Verbal Idiom under the PARSEME guidelines.[28]

To move on to the second candidate pairing, in (18), the middle form of ποιέω poieō and a determiner phrase combine with syntactically thus nominalised δίκαιος dikaios ‘just’.

| Isocrates, Speech, 4.177 |

| ἐχρῆν γὰρ αὐτούς, εἴτ᾽ ἐδόκει τὴν αὑτῶν ἔχειν ἑκάστους, εἴτε καὶ τῶν δοριαλώτων ἐπάρχειν, εἴτε τούτων κρατεῖν ὧν ὑπὸ τὴν εἰρήνην ἐτυγχάνομεν ἔχοντες, ἕν τι τούτων ὁρισαμένους καὶ κοινὸν τὸ δίκαιον ποιησαμένους, οὕτω συγγράφεσθαι περὶ αὐτῶν. |

| ekhrēn gar autous, eit᾽ edokei tēn hautōn ekhein hekastous, eite kai tōn dorialōtōn eparkhein, eite toutōn kratein hōn hupo tēn eirēnēn etunkhanomen ekhontes, hen ti toutōn horisamenous kaì koinon to dikaion poiēsamenous , houtō sungraphesthai peri autōn. |

| ‘For it would have been necessary – whether it seemed good that each have their own (territory), or rule what had been conquered, or rule what we happened to have in times of peace – that they consider one of these and do justice overall and in this way draft the contract about them.’ |

The singular form of the nominalisation and the middle form of the verb seem to be comparatively rare. The plural form of the nominalisation and the active form of the verb seem to be preferred in classical literary Attic historiography, oratory, and philosophical prose (ECF Leverhulme corpus). Isocrates seems to have availed himself of the option of syntactic nominalisation and fit it into the frame of the Light-Verb Construction par excellence. He may have done so as the combination of the lexical noun, δικαιοσύνη dikaiosunē, with the light verb is only current from the Septuagint (ca. 3rd c. BC) onwards according to lemma-based proximity searches in the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae.[29] While Isocrates’ creation appears to be a one-off, he seems to utilise a Light-Verb-Construction frame that otherwise allows for lexical, morphological, morpho-syntactic, and syntactic flexibility (see Fendel 2025c).

τὸ δίκαιον to dikaion passes the abstractness and predicativeness tests without the ambiguity observed above between thing and circumstance/behaviour. Justice is contextually determined (by reference to the legislative and executive structures in charge of it, of whatever kind) and must be administered, such that we have an agent at least implied. This makes it likely that the structure passes V-REDUC. The verb passes V-LIGHT. The structure as a whole qualifies thus as LVC.full.

To move on to the third candidate pairing, (19) is ambiguous in that the determiner phrase is a negative determiner phrase which is form-identical with a negative pronoun, such that the structure could be analysed as a negative pronoun plus modifying adjective:

| Lysias, Speech, 3.42 |

| ἀλλ᾽ ὅσοι ἐπιβουλεύσαντες ἀποκτεῖναί τινας ἔτρωσαν, ἀποκτεῖναι δὲ οὐκ ἐδυνήθησαν, περὶ τῶν τοιούτων τὰς τιμωρίας οὕτω μεγάλας κατεστήσαντο, ἡγούμενοι, ὑπὲρ ὧν ἐβούλευσαν καὶ προὐνοήθησαν, ὑπὲρ τούτων προσήκειν αὐτοῖς δίκην δοῦναι: εἰ δὲ μὴ κατέσχον, οὐδὲν ἧττον τό γ᾽ ἐκείνων πεποιῆσθαι. |

| all᾽ hosoi epibouleusantes apokteinai tinas etrōsan, apokteinai de ouk edunēthēsan, peri tōn toioutōn tas timōrias houtō megalas katestēsanto, hēgoumenoi, huper hōn ebouleusan kai prounoēthēsan, huper toutōn prosēkein autois dikēn dounai: ei de mē kateskhon, ouden hētton to g᾽ ekeinōn pepoiēsthai . |

| ‘However, all those who after plotting to kill someone wounded them, but could not kill (them), with regard to those they established such great punishments thinking that it would be right for them to pay the price for those actions which they planned and premeditated and even if they did not achieve (it), (that) they made no less effort than those.’ |

However, even if we are thus dealing with a bridging context, the adjective noticeably appears in the comparative. While syntactically nominalised adjectives can appear in the comparative and superlative forms, this is impossible with lexical nominalisations. We find the same reliance on a syntactic nominalisation for this reason in well-known περὶ πολλοῦ/πλείονος/πλείστου ποιέομαι peri pollou/pleionos/pleistou poieomai ‘to appreciate’.[30] Thus, out of the three candidates for Light-Verb Constructions, one seems to qualify, albeit a one-off, one is ambiguous, and one seems to be a Verbal Idiom.

Table 5 shows a further curiosity in structures with syntactic nominalisations, i.e. direct objects. The below considers only structures with a determiner phrase accompanying the adjective. It leaves out those in which a negative or indefinite determiner phrase appears as these are form-identical with their pronoun counterparts such that the structures in question could be analysed as pronoun plus modifying adjective. This leaves the instances shown in (20)–(22). They consist of a doing verb (ἐργάζομαι ergazomai, ποιέω poieō) and nominalised κακά kaka ‘evil’.

Κακά kaka ‘evil, badness’, like τὸ δίκαιον to dikaion, passes the abstractness and predicativeness tests without ambiguity between thing and circumstance/behaviour. Badness/evil is contextually determined (by reference to the prevailing societal norms and their concept of good and acceptable, of whatever kind) and must be committed, such that we have an agent at least implied. Thus, we have good candidates for Light-Verb Constructions.

Taking verb lability (Lavidas 2009, 68 and 92–93) into account, ποιέω poieō with an active inflectional ending can be a lexical verb in a three-, two-, and one-argument frame (‘to make, to do, to act’), a semi-lexical light verb in a three- and two-argument frame (LVC.full vs. LVC.cause), and a grammatical auxiliary (causative) (cf. Anderson 2006; Boye 2023). In (20), ποιέω poieō seems to be a semi-lexical light verb in a two-argument frame:

| Lysias, Speech, 14.10 |

| καὶ ἕτεροι μὲν οὐδεπώποτε ὁπλιτεύσαντες, ἱππεύσαντες δὲ καὶ τὸν ἄλλον χρόνον καὶ πολλὰ κακὰ τοὺς πολεμίους πεποιηκότες, οὐκ ἐτόλμησαν ἐπὶ τοὺς ἵππους ἀναβῆναι, δεδιότες ὑμᾶς καὶ τὸν νόμον· |

| Kai heteroi men oudepōpote hopliteusantes hippeusantes de kai ton allon khronon kai polla kaka tous polemious pepoiēkotes ouk etolmēsan epi tous hippos anabēnai dediotes humas kai ton nomon |

| ‘And the others, who have never served as hoplites but had served in the cavalry for some time and done much evil to the enemy, did not dare to mount the horses fearing you and the law.’ |

In (20), analysis of πολλὰ κακὰ τοὺς πολεμίους πεποιηκότες polla kaka tous polemious pepoiēkotes as causative (i.e. ποιέω poieō as an auxiliary), i.e. ‘made the enemy evil things/made evil things the enemy’ does not make sense contextually. Analysis as verb–object–adverbial (i.e. ποιέω poieō as a lexical verb), i.e. ‘treated the enemy badly’, is contextually possible but seems to take the force out of the expression. Analysis as a Light-Verb Construction is possible but comes with the otherwise rare feature in Attic oratory of a direct object in the accusative case referring to a Patient in Naess’ (2007) terms (Fendel 2023).[31]

(20) is isolated in that the other two instances with a direct object referring to a patient show the verb ἐργάζομαι ergazomai, (21) and (22).

| Lysias, Speech, 12.33 οὐ γὰρ μόνον ἡμῖν παρεῖναι οὐκ ἐξῆν, ἀλλ’ οὐδὲ παρ’ αὑτοῖς εἶναι, ὥστ’ ἐπὶ τούτοις ἐστὶ πάντα τὰ κακὰ εἰργασμένοις τὴν πόλιν πάντα τἀγαθὰ περὶ αὑτῶν λέγειν. |

| ou gar monon hēmin pareinai ouk exēn all’ oude par’ autois einai hōst’ epi toutois esti panta ta kaka eirgasmenois tēn polin panta tagatha peri autōn legein. |

| ‘For not only was it not possible for us to be present (sc. in public) but also not to be at home such that it is up to these people, who have done so much evil to the city, to say all the good things about themselves.’ |

(22) could be read either with an object-continuity structure (Luraghi 2003) or as intransitive.

| Lysias, Speech, 12.41 Πολλάκις οὖν ἐθαύμασα τῆς τόλμης τῶν λεγόντων ὑπὲρ αὐτοῦ, πλὴν ὅταν ἐνθυμηθῶ ὅτι τῶν αὐτῶν ἐστιν αὐτούς τε πάντα τὰ κακὰ ἐργάζεσθαι καὶ τοὺς τοιούτους ἐπαινεῖν. |

| pollakis oun ethaumasa tēs tolmēs tōn legontōn huper autou plēn hotan enthumēthō hoti autōn estin autous te panta ta kaka ergazesthai kai tous toioutous epainein |

| ‘Thus, I have often wondered at the audacity of those speaking for him, except when I consider that it is up to these people to do much evil and to praise such people.’ |

Ἐργάζομαι ergazomai can be a lexical verb in a two- (‘to work, to do’) and one-argument (‘to work (at/in)’) frame, a semi-lexical support verb in an LVC.cause structure (‘to cause’, LSJ II.7) and the structure shown in (21) (‘to do (evil)’ II.2) (see also Baños and Jiménez López forthcoming). The verb appears frequently in cognate-object constructions (LSJ II.2).[32]

(21) and (22) come from the same speech by Lysias and show the same modification of the nominalisation by means of a quantifier and a continuous structure. A lemma-based proximity search in the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (πᾶς pas, κακός kakos, ἐργάζομαι ergazomai within 5 words) shows that the same structure appears once more in the same speech (Lysias, Speech, 12.57, there without an object), twice in Demosthenes yet without a determiner phrase (Demosthenes, Speech, 9.57 without an object; Demosthenes, Speech, 19.314 with the accusative object τὴν πόλιν tēn polin ‘the city’), and once in Aristophanes (Archanians, l. 981 without an object). The additional instances reveal an extent of morphosyntactic (determiner phrase) and syntactic (word order) flexibility and that the phrase is not idiolectal. Thus, for (20) to (22), an analysis as Light-Verb Construction seems likely.

However, direct objects in the accusative case are rare with Light-Verb Constructions of the to make a suggestion type, i.e. light verb + noun in the verb’s object slot. While the object slot is vacant in the functional structure, it is filled in the constituent structure (in the terms of Lexical-Functional Grammar). However, there are two scenarios that could explain why a direct object is permissible.

Scenario one is that the Light-Verb Construction has become a Verbal Idiom which is completely invariable, e.g. take heart in English, such that the noun in the verb’s object slot is no longer perceived as a separate unit (i.e. loss of analyticity and compositionality). This scenario can be ruled out based on flexibility observations for (21) (and (22)) and seems unlikely in (20) where the accusative object intervenes between the components of the multi-word-expression candidate.

Scenario two is that the light verb is moving from a (semi-)lexical item to a grammatical item in Boye’s (2023) sense, i.e. it cannot be (i) focussed, (ii) addressed in subsequent discourse, (iii) modified, or (iv) stand alone in an utterance. (ii) and (iv) are true of light verbs in general. (i) and (iii) might be true in structures with a direct object.[33] There is evidence for such a development in parallel with the highly productive, in the sense of generality (Barðdal 2008, 21), light verb ‘to do’ in postclassical Greek (Fendel 2025c).[34] However, in classical times, direct objects in structures with ‘to do’ and ‘to put’ seem to be limited primarily to the Ionic dialect and Attic verse literature (Fendel 2023).

A third scenario relates to the location of the valency centre. The valency centre can be the Light-Verb Construction as a whole – this is what scenarios one and two are based on – but it can also be the predicative noun, e.g. to have hope for (…) versus to have hope that (…) (cf. Hoffmann 2018, 80). If the noun is the valency centre, we find what Lowe (2017) calls transitive nouns, i.e. nouns that take internal arguments and specifically objects. There are also transitive adjectives, e.g. desirous of (…). If we nominalise these syntactically, we obtain a transitive nominal. Thus, the valency centre of a Light-Verb Construction consisting of a light verb and a syntactically nominalised transitive adjective could be the nominalisation. Candidates for transitive adjectives are ἔμπειρος empeiros ‘experienced in’ and ἐπιστήμων epistēmōn ‘knowledgeable about’ (van Emde Boas et al. 2019, 369–370). Both these are subject-oriented (Lowe 2017, 35) rather than situation-oriented (like hope for). While κακά kaka ‘evil, badness’ does not seem to be a transitive adjective (or nominal), we noted above that it passes the abstractness and predicativeness tests and has an implied agent. Thus, we seem to come out with scenario two as the most likely analysis.

Lexical nominalisations (κακία kakia and κακότης kakotēs) co-exist with the syntactic nominalisation κακά kaka and appear in Light-Verb Constructions and Verbal Idioms in the ECF Leverhulme corpus: (LVC) κακίαν ἔχω kakian ekhō ‘to be bad’ (Demosthenes, Speech, 18.280; Plato, Gorgias, 478d8; Aristotle, Rhetoric, 1388b34 (plural)) and (VID) εἰς τοσοῦτον κακίας ἔρχομαι/ἀφικνέομαι eis tosouton kakias erkhomai/aphikneomai ‘to go to such badness (that)’. Κακότης kakotēs does not appear in verbal multi-word expressions in the ECF Leverhulme corpus.

The combination of κακία kakia with ποιέω poieō does not appear before the Septuagint (ca. 3rd c. BC) as lemma-based proximity searches in the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae reveal.[35] The exception is Hippocrates, De locis in homine, 43.11 ἐπὴν δὲ κρατέωσιν, ὑπεκχωρήσεις τε ποιέουσιν καὶ ἀλλοίας κακίας epēn krateōsin, hupekkhōrēseis te poieousin kai alloias kakias ‘as soon as they are strong (enough), they excrete by stool and are otherwise bad’ in a highly technical context (see also Squeri 2024). Other doing verbs do not appear either in verbal multi-word expressions with κακία kakia in classical times. A lemma-based proximity search for κακία kakia and ἐργάζομαι ergazomai (maximum distance of 5 words) in the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae reveals that the first instance appears in Philo Judaeus, Legum allegoriarum (1st c. BC to 1st c. AD), 3.122.2 ἀλλὰ ταύτῃ κακίαν ἐργάσεται τὴν ἐν λόγῳ ‘but he will do the evil that is in the word to this one’. A lemma-based proximity search for κακία kakia and πράσσω prassō (maximum distance of 5 words) in the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae reveals that the earliest unambiguous instance is Didymus Caecus, Fragmenta in Psalmos (e commentario altero), Frg. 147.11 καὶ τὴν ἄλλην ἅπασαν ἔπραττεν κακίαν kai tēn allēn hapasan epratten kakian ‘and he did all the other evil’ (4th c. AD). A lemma-based proximity search for κακία kakia and πλάσσω plassō (maximum distance of 5 words) in the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae reveals that the earliest instance is Plutarch, Fragments, Frg. 161.3 Κακίας αὑτῶν πλάσσονταί τινες ῥημάτων εὐπρεπείᾳ ‘some of the words do their evil by means of good appearance’ (1st/2nd c. AD). In Titus Bostrensis’ Contra Manichaeos (4th c. AD), the combination appears twice (2.39.8 and 2.49.8).

κακότης kakotēs appears in verbal multi-word expressions in archaic and classical Attic verse and classical Ionic prose as manual inspection of a lemma-based search in the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae reveals.[36] However, lemma-based proximity searches with κακότης kakotēs and ἐργάζομαι ergazomai, πλάσσω plassō, and πράσσω prassō return no relevant hits of verbal multi-word expressions. The only instance with ποιέω poieō appears in Oracula Sibyllina, 5.202 (2nd c. BC to 4th c. AD) καὐτοὶ γὰρ κακότητα θεοῦ τέκνοις ἐποίησαν kautoi gar kakotēta theou teknois epoiēsan ‘for they did evil to the god’s children’. The oracles are a highly specialised communication situation (Mel’čuk 2023, 162; Fendel 2025d). Thus, it seems that the syntactic nominalisation κακά kaka is the default option to express ‘to do evil (to somebody)’ in classical Greek.

Unlike with the structures reviewed in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, the structures in the present section do not co-exist, synchronically, with a structure with a lexical nominalisation. They seem to be selected in order to fill a gap in the range of lexical expressions. Relevant structures can be Verbal Idioms such that ambiguity of meaning is reduced but they can also be Light-Verb Constructions for which in contexts that do not have ambiguity-reducing factors, a certain amount of ambiguity remains in place.

4 Discourse, Register, and Lexical Gaps

Section 3 has shown that syntactic nominalisations can appear in verbal multi-word expressions, both in Verbal Idioms and in Light-Verb Constructions in the PARSEME terms. Furthermore, structures with comparable lexical and syntactic nominalisations can co-exist yet are not equivalent from a variationist point of view. Finally, structures with syntactic nominalisation can fill gaps in the range of expression. The below revisits the structures discussed and categorised in Section 3 from the perspective of their fit into the system synchronically speaking.

When referring to the giving and receiving of pledges, Xenophon had three options to choose from: (i) the non-transparent Verbal Idiom δεξιὰν/δεξιὰς δίδωμι/λαμβάνω dexian/dexias didōmi/lambanō ‘to give/receive pledge(s)’, (ii) the transparent Verbal Idiom (τὰ) πιστὰ δίδωμι/λαμβάνω (ta) pista didōmi/lambanō ‘to give/receive pledge(s)’, and (iii) the Light-Verb Construction πίστιν/πίστεις δίδωμι/λαμβάνω pistin/pisteis didōmi/lambanō ‘to give/receive pledge(s)/assurance(s)’ (although note that PARSEME would qualify the recipient passive as NotMWE). The difference between the three is their discursive value. The non-transparent Verbal Idiom is derived from the act of shaking hands on a deal and handing over items as leverage. It can be resumed in subsequent discourse only as a whole. Conversely, the transparent Verbal Idiom with a syntactic nominalisation introduces ambiguity between physical pieces of leverage and the abstract behaviour surrounding the deal. It can be resumed in subsequent discourse by referring to the πιστά pista ‘loyal things/behaviours’ and exploiting its ambiguity (between physical item and abstract situation). Finally, the Light-Verb Construction allows for pronominalisation (e.g. by means of a relative pronoun) and lexical resumption of the noun. The noun is fully accessible and refers by itself to the event of giving pledges. It can be modified by means of attributive and determiner phrases in order to add nuancing to the picture (e.g. ἱκανάς hikanas ‘suitable’, Isaeus, Speech, 8.45) (Wittenberg and Trotzke 2021; Fendel and Ireland 2023). Thus, Xenophon’s choice of one or the other expression was likely conditioned on a context-by-context basis by subtle semantico-pragmatic nuances.

When referring to the state of being clueless and somewhat in despair as a result, Thucydides and in postclassical (Roman) times his fellow historians Lucian and Cassius Dio use the Verbal Idiom ἐν ἀπόρῳ ἔχομαι en aporō ekhomai ‘to be clueless’. The Verbal Idiom seems to be domain-specific and is not used outside of the historiographical context (except in later quotes of the former historians). The Verbal Idiom co-exists with the Light-Verb Construction ἐν ἀπορίᾳ ἔχομαι en aporia ekhomai ‘to be clueless’ which, unlike the idiom, is built around a lexical nominalisation. The Light-Verb Construction is domain-unspecific in classical times albeit limited to prose writings. The historians’ alternative seems to differ not only semantico-pragmatically as outlined above for Verbal Idioms versus Light-Verb Constructions but also in its indexical value. According to Bentein (2019, 123) ‘[l]inguistic indexes are “structures” (lexemes, affixes, diminutives, syntactic constructions, emphatic stress, etc.) that have become conventionally associated with a particular situational dimension, and that invoke that situational dimension whenever they are used’ (cf. Fendel 2024a with further references). While the Light-Verb Construction is domain-unspecific, the Verbal Idiom indexes historiographical writings and possibly something of a technical register. Conversely, in the case of the Verbal Idiom τὰ ἀπόρρητα ποιέομαι ta aporrēta poieomai ‘to keep secrets, to be secretive’ an alternative with a lexical nominalisation (i.e. ἀπόρρησις aporrēsis ‘forbidding’ and ἀπόρρημα aporrēma ‘prohibition’) does not exist before the postclassical period. Thus, the Verbal Idiom with the syntactic nominalisation seems to fill a lexical gap.

Structures with syntactic nominalisation can be Light-Verb Constructions, yet seemingly with a limitation to those syntactic nominalisations that pass the abstractness and predicativeness tests without creating obvious ambiguity between the readings of ‘things’ versus ‘circumstances/behaviours’, unlike e.g. πιστά pista which could refer to the physical items handed over as pledges or the behaviour in the situation. (τὰ) κακὰ ποιέω/ἐργάζομαι (ta) kaka poieō/ergazomai seems to be the standard phrase to express ‘to do evil (to)’. While Light-Verb Constructions referring to ‘to be evil’ (e.g. κακίαν ἔχω kakian ekhō and κακότητα ἔχω kakotēta ekhō) and ‘to become evil’ (e.g. εἰς κακότητα πίπτω eis kakotēta piptō) exist with lexical nominalisations instead of syntactic nominalisations in classical times, structures meaning ‘to do evil’ with a lexical nominalisation do not appear in classical times. The ‘do evil’ structures noticeably appear with direct objects inflected in the accusative case and functionally referring to a Patient. This is otherwise rare in verb-object-type Light-Verb Constructions in Attic non-verse texts. It seems that the doing verb has moved further towards the grammatical sphere in Boye’s (2023) terms and thus the option of a direct object becomes available. The doing verb as a productive light verb is also reflected in Isocrates’ creation of τὸ δίκαιον ποιέομαι to dikaion poieomai (vs. δικαιοσύνη dikaiosunē) ‘to do justice (to)’ instead of the more common plural of the syntactic nominalisation and active voice of the doing verb. Isocrates seems to have drawn upon a frame that was available (see also Fendel 2025c).

Overall, we notice that structures with syntactic nominalisations can fit into the system synchronically as gap fillers, indexical alternatives, or semantico-pragmatic alternatives. Not all structures are Verbal Idioms, but Light-Verb Constructions exist.

5 Summary, Conclusion, and Outlook

The PARSEME GRC guidelines distinguish between Light-Verb Constructions, such as to make a suggestion, and Verbal Idioms, such as to kick the bucket. Light-Verb Constructions need to contain a nominal element that is abstract and predicative. Verbal Idioms are lexically, morphologically, morphosyntactically, and syntactically inflexible. Syntactic nominalisations as the nominal element in Light-Verb Constructions are usually disregarded due to their structural and functional ambiguity. However, this article has considered the eventiveness of the nominal component the crucial characteristic (see research question one) and thus allowed for non-deverbal and underived event nouns, including syntactic nominalisations, as predicative nouns. It has shown that syntactic nominalisations can appear as predicative nouns in Light-Verb Constructions along with forming part of Verbal Idioms (see research question two). Synchronically, verbal multi-word expressions containing a syntactic nominalisation can be gap fillers, indexical alternatives, or semantico-pragmatic alternatives to structures with a lexical nominalisation (see research question three).

(τὰ) κακὰ ποιέω/ἐργάζομαι (ta) kaka poieō/ergazomai seems to be the standard phrase to express ‘to do evil (to)’. While Light-Verb Constructions referring to ‘to be evil’ (e.g. κακίαν ἔχω kakian ekhō and κακότητα ἔχω kakotēta ekhō) and ‘to become evil’ (e.g. εἰς κακότητα πίπτω eis kakotēta piptō) exist with lexical nominalisations in classical times, structures meaning ‘to do evil’ with a lexical nominalisation do not appear in classical times. The classical historian Thucydides and in postclassical (Roman) times his fellow historians Lucian and Cassius Dio use the Verbal Idiom ἐν ἀπόρῳ ἔχομαι en aporō ekhomai ‘to be clueless’, which seems domain-specific and thus seems to carry indexical properties. The historian Xenophon chose between (i) the non-transparent Verbal Idiom δεξιὰν/δεξιὰς δίδωμι/λαμβάνω dexian/dexias didōmi/lambanō ‘to give/receive pledge(s)’, (ii) the transparent Verbal Idiom (τὰ) πιστὰ δίδωμι/λαμβάνω (ta) pista didōmi/lambanō ‘to give/receive pledge(s)’, and (iii) the Light-Verb Construction πίστιν/πίστεις δίδωμι/λαμβάνω pistin/pisteis didōmi/lambanō ‘to give/receive pledge(s)/assurance(s)’ for semantico-pragmatic reasons. Syntactic nominalisation is fully productive, in the sense of generality, in classical and postclassical Greek and offers the option of nuancing the degree (by means of comparatives and superlatives) unlike the derivational morphology.

This study is based on the PARSEME Ancient Greek and ECF Leverhulme Sketch Engine corpora of literary classical Attic philosophical prose, historiography, and oratory with comparative (diachronic) data added where necessary. These are the only two corpora that are suitably annotated for verbal multi-word expressions in classical Greek. The sample sizes are relatively small and samples are non-random such that results do not currently allow for statistical significance testing. Noticeably, direct objects are permissible with those structures consisting of a syntactic nominalisation in the predicative-noun slot and a doing verb in the verb slot, a phenomenon otherwise only observed regularly in Ionic prose and Attic verse. Furthermore, it would be desirable to assess more widely the relationship between lexical and syntactic nominalisations. Structures with lexical nominalisations (and cognate-object constructions) are currently annotated as NotMWE in the PARSEME Ancient Greek corpus, except if they qualify as Verbal Idioms. In future, this will make possible further study on a larger sample and eventually randomisation of sampling for statistical testing.

Funding source: European Cooperation in Science and Technology

Award Identifier / Grant number: CA21167

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Not applicable.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Research funding: This work received support from the CA21167 COST action UniDive, funded by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

-

Data availability: ORA (Oxford’s institutional repository) with DOI assigned.

References

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 2023. “Zero-Derived Nouns in Greek.” Languages 8 (1): 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010013.Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, Gregory. 2006. Auxiliary Verb Constructions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199280315.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Baños, José Miguel, and María Dolores Jiménez López. Forthcoming. “Translation as a Mechanism for the Creation of Collocations (I): The Alternation ἐργάζομαι/ποιέω in the Bible”.Suche in Google Scholar