Abstract

The growing presence of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) tools in academic writing has raised questions about their role in supporting students’ development as writers. While existing research has explored the capabilities and limitations of GAI, there is a notable gap in understanding students’ perspectives on its use. This study investigates whether students want to engage with GAI in their academic writing, their reasons for doing so, and how they perceive its benefits and challenges. Additionally, it touches on the role of educator transparency in using AI tools, exploring whether openly sharing such practices fosters trust and enhances the learning experience. The study highlights the importance of educators modelling ethical AI use to build a collaborative and trusting classroom environment. It also shows the shift in student strategies towards leveraging GAI tools as learning aids rather than convenience tools.

1 Introduction

The integration of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) tools in academic writing has sparked widespread debate in educational contexts, with both educators and students discussing the benefits and challenges of these technologies. While much research has focused on the capabilities of GAI – such as overcoming writer’s block, enhancing vocabulary and assisting in content brainstorming (Gilburt 2023; Werdiningsih et al. 2024) – there remains a significant gap in understanding students’ perspectives on its use. Do students view GAI as a valuable tool in their academic journey or do they see it as a potential problem? What motivates their decision to use or avoid such tools? Addressing these questions is significant for educators aiming to guide effective and ethical engagement with GAI in academic settings.

This study seeks to contribute to the growing body of literature by exploring students’ attitudes toward generative GAI in academic writing. It focuses on understanding whether they want to use these tools, how they perceive their benefits and the extent to which they believe GAI supports their development as writers. Equally important is the consideration of challenges associated with GAI use, such as its potential to undermine creativity, authenticity and the unique voice of the author (Lingard 2023; Rebolledo Font de la Vall and Gonzalez Araya 2023).

Another dimension of this action research is the role of the educator’s own engagement with GAI in the learning environment. Transparency in teaching practices, including openly sharing the use of GAI tools, may have an impact on building trust between students and instructors. This study suggests that such openness may help foster a supportive learning environment and encourage students to engage critically with GAI technology.

By addressing these intertwined themes, this action research aims to shed light on understanding of the relationship between students, GAI and educators in academic writing. This study, through student feedback and reflections on teaching practices, seeks to begin bridging the current research gap identified in the literature review below. Specifically, it addresses the gap in research regarding students’ perspectives on the use of GAI in academic writing – particularly whether they wish to use it and why. Additionally, the study aims to offer practical insights for educators striving to balance the potential of GAI with the development of authentic and creative student voices.

2 Literature review

Recent literature highlights the emerging role of GAI in education, particularly in language learning and writing pedagogy. Research on the ethical and pedagogical implications of GAI tools, such as AI-generated feedback and chatbots, has grown, with notable contributions offering varied perspectives.

Foltynek et al. (2023) emphasize the importance of ethical frameworks for GAI usage in educational settings, particularly regarding transparency and the decision-making process. They stress the challenges of proving whether student-generated content is GAI-assisted, raising questions about acceptable use. Similarly, Pack and Maloney (2024) and Weber-Wulff et al. (2023) delve into the ethical and pedagogical challenges for educators and students. Pack and Maloney (2024) moreover underline the potential of GAI to act as a “linguistic crutch” for less proficient learners and call for reflective practices on the integration of GAI in teaching.

The utility of GAI in language learning has been explored through tools like Grammarly and GAI-enabled automated writing evaluation (AWE) programs. Escalante et al. (2023) posit that GAI can serve as a “more knowledgeable other,” providing comprehensible input during various stages of writing. Ingley and Pack (2023) highlights creative uses of GAI, such as role-playing as reviewers or teachers to enhance critical thinking and engagement. Moreover, GAI feedback can not only reduce teacher workload and prevent burnout, but its linguistic benefits also remain comparable to human-provided feedback, as shown in studies on English as a new language (ENL) students by Escalante et al. (2023).

Chatbots are another GAI application with mixed impacts on critical thinking, engagement and motivation. Labadze et al. (2023) outline their strengths in personalized learning, homework assistance and skill development. Despite these advantages, concerns persist about over-reliance hindering critical thinking. For optimal outcomes, effective prompt engineering is necessary, as it guides chatbots to perform tasks aligned with educational objectives (Zhou et al. 2023).

Research has explored students’ experiences using generative GAI in academic writing, highlighting both its benefits and challenges. On the positive side, GAI has been found to help students overcome writer’s block (Gilburt 2023), assist with text production uncertainties, build vocabulary and support content brainstorming (Werdiningsih et al. 2024). However, studies have also emphasized its limitations, particularly regarding preserving the author’s unique voice and fostering creativity (Lingard 2023; Rebolledo Font de la Vall and Gonzalez Araya 2023) – concerns that were also expressed by the students in the present study.

A consistent theme across studies is the tension between the benefits and potential drawbacks of GAI tools. While they enhance accessibility and efficiency, they also raise questions about student independence, teacher roles and disclosure of GAI use in materials. The ethical and pedagogical implications, particularly for language educators, remain central to ongoing debates. The literature demonstrates that GAI has the potential to transform education but underscores the need for thoughtful integration to balance innovation with ethical and pedagogical integrity.

There is a notable gap in research regarding students’ perspectives on the use of GAI in academic writing. While several authors have engaged with the concept of students using GAI tools for academic writing (Meniado et al. 2024; Werdiningsih et al. 2024), their focus has primarily been on describing the nature of this engagement. However, there has been a significant call for deeper exploration into the ethical and pedagogical implications of incorporating GAI tools in language education (Pack and Maloney 2024). In particular, Pack and Maloney have expressed hopes about students’ inclinations to use these tools not necessarily for improving their writing but rather for enhancing their own abilities as writers. This distinction between the tool’s application for self-improvement versus writing enhancement has not been sufficiently addressed in the existing literature, particularly with respect to students’ motivations and their reasons for adopting or avoiding the use of such tools.

3 Self-help via action research and defining the action research questions

For many practicing academics, action research became a useful tool used to deal with immediate problems in their everyday teaching contexts. The term, coined in the 1940s by Kurt Lewin (1946), refers to a practice of solving problems by circles of observing, reflecting and acting (McIntosh 2010). This practice was embraced enthusiastically among others by ESP practitioners because theirs is an area in which readymade solutions are rarely available and often lacks the opportunity to form large, balanced student cohorts for research. The method is especially relevant in situations where teachers are not looking for an instant fix but for the development of a solution that can be adapted as the need arises. This aligns with both the goals and constraints of my own context.

The action research was conducted with Czech and Slovak law students during their Legal English course, a specialized ESP program. The student groups were small, consisting solely of Czech and Slovak law students, and were formed independently of the instructor’s control or choice. Students’ language proficiency ranged between B2 and C1 on the CEFR scale. All students were in their second year of studies, aged 20–22, making the groups highly homogeneous.

The small-scale action research project, presented here, seeks to contribute to the discussion by investigating students’ attitudes toward GAI in academic contexts. Specifically, the project aims to assess whether students perceive GAI as beneficial, how they believe it aids their academic development and factors influencing their decision to use or refrain from using it. Beyond these points, the project aims to understand the broader impact of transparency in teaching. Indeed, in my role of instructor of this specific group of students, I raise a question whether openly sharing my own use of GAI tools in teaching fosters trust between me and the students and whether it enhances the overall learning experience. As a consequence, by exploring both students’ perspectives on GAI and the influence of the instructor’s transparency (the author, in this case), the action research hopes to provide insights into how GAI can be effectively integrated into academic writing instruction. The action research inquiry was motivated by curiosity about the degree to which students are aware of the services GAI offers, the extent of their inclination to use these tools, the specific purposes for which they utilize them and their general attitudes toward GAI in academic writing.

Action research seeks to address problems through cycles of observation and reflection. In line with this approach, the same experiment, focused on students’ reflections on their own writing task completion, was conducted three times with three different groups over an eighteen-month period. Minor adjustments were made to the methodology during the final experiment, specifically regarding the instructor’s intentional disclosure of her own teaching practices in the sessions leading up to the task. These adjustments aimed to enhance the reflective process, critical use and the overall learning experience.

In each cycle, the students first engaged in discussions and hands-on experimentation with available GAI tools during their seminar sessions. These activities, conducted in small teams, were designed to foster collaboration and critical engagement with GAI technology. As part of this process, students were introduced to the university’s guidelines and recommendations regarding GAI usage, such as those outlined in Masaryk University’s official statement on GAI use (Masaryk University n.d.). To model ethical GAI practices, the teacher shared personal examples of how GAI was used to prepare lessons, highlighting both the benefits and challenges of incorporating GAI into educational settings. Building on this foundation, students collaboratively developed their own set of rules for GAI use, which they agreed to follow. The main emphasis in these discussions was on promoting transparency and establishing trust in the use of GAI tools.

Following this, the action research phase transitioned to data collection. Students had the opportunity to practice in groups, working together in shared documents before engaging in a peer review process of the texts they produced. After this collaborative phase, the writing task was set for individual completion, carried out asynchronously in students’ own time and submitted through the university’s system.

The writing tasks themselves were contextually relevant, drawn from a needs analysis of the skills that future lawyers are expected to develop. These tasks included professional communication exercises, such as drafting responses to client issues or consultations, as well as the creation of academic abstracts. Such tasks are integral to students’ coursework and academic writing in English, particularly at Czech universities, where law students are often required to navigate both legal and academic language.

Since our focus is on ESP, any task assigned to students should be tailored to reflect the specific communicative situations relevant to their field (Hutchinson and Waters 1987). High-stakes professional and academic writing in the real world often relies on external assistance to refine the final product. GAI is one such tool that can support this process, and it is likely that these students, as future lawyers, will utilize such tools in real-life scenarios. Escalante et al. (2023) suggest that the prevailing sentiment on GenAI is that educational practices should be reformed to accommodate the technology rather than resist it. The historical lesson of pocket calculators demonstrates that prohibiting or ignoring technological advancements is neither practical nor beneficial. Instead, working collaboratively with GAI in a creative and iterative process allows learners to take an active role in writing, rather than relying on GAI to do all the thinking for them (Escalante et al. 2023). As a result, the integration of GAI into these assignments was openly acknowledged as acceptable.

Data collection was facilitated through structured reflections, which were paired with each writing assignment. These reflections were specifically designed to encourage students to critically evaluate their use of GAI tools throughout the writing process. To guide this self-assessment, students were provided with a set of reflective questions that prompted them to analyse their writing processes and consider the role of GAI in enhancing the quality of their work.

As mentioned earlier, with the intention to build trust, the instructor created a collaborative environment where both students and the teacher shared best practices and examples of using GAI tools. This approach was particularly emphasized during the final action research cycle, where the instructor intentionally and consistently highlighted every instance of using GAI for class administration, as well as for developing materials and tests. Whenever possible, the instructor highlighted that specific resources -such as pictures, mind maps, quizzes, exercises, scripts for listening tasks, reports, and audio materials-were created with the assistance of GAI, explaining the extent and reasons for its use. Students were then invited to reflect on and provide feedback regarding the quality and appropriateness of these materials and suggested possible improvements.

These open and transparent discussions as well as the invitation to contribute to material improvement helped increase the probability that students could feel comfortable sharing honest reflections on their own experiences. Crucially, it was emphasized that students’ texts would be evaluated based on content, structure and the use of functional language rather than the method of creation. This assurance, along with the trust established within the group, served as avenues to mitigate potential biases and encouraged authenticity in task completion as well as the reflections, although some bias may still have been present due to the non-anonymous nature of the feedback.

Ethical considerations were carefully addressed in this action research study, particularly regarding the use of student data. Students were informed at the outset that the reflections they submitted on their writing would be used for research purposes. Importantly, the data would be anonymised, ensuring that individual identities would not be disclosed. The teacher made it clear that the reflections would be analysed to generate basic statistics and that the results of the research would be shared with students at the end of the semester. In order to respect students’ autonomy and privacy, those who did not feel comfortable participating were given the option to exclude their reflections from the writing task. A few students chose this option, opting not to have their reflections included in the study. By offering this choice, the research maintained ethical integrity, balancing the need for data collection with respect for student consent and confidentiality. The process ensured that participation was voluntary and informed, fostering a respectful and transparent research environment. Ultimately, students were fully aware of the use of their data and their agreement to participate was obtained with clear understanding of how their reflections would contribute to the research.

The methodology for gathering structured reflective feedback from students was designed to encourage critical self-reflection on their use of GAI tools during the writing process. Students were asked a series of guided questions aimed at exploring both the timing and rationale behind their use of GAI tools. Specifically, they were asked to identify at what stage of their writing process they engaged with GAI and to explain why they chose to use it at that particular stage. This helped to uncover how students integrated GAI into different phases of their writing, such as brainstorming, drafting or revising. In contrast, students who did not use GAI were prompted to reflect on the reasons for their decision, allowing for a deeper understanding of factors such as reluctance or preference for traditional writing methods. Furthermore, students who utilized GAI were asked to describe the strategies they employed when prompting the tool, providing insight into their approach and level of interaction with GAI. Finally, students were asked to express their opinions on the use of GAI in academic writing, fostering a broader discussion on its perceived benefits, challenges and ethical considerations. This reflective feedback methodology enabled a comprehensive analysis of students’ attitudes and behaviours toward GAI in writing, while promoting critical thinking about its role in academic contexts (Tables 1 and 2).

Students’ reflections.

| Please, think about the following questions | Please, give your answers where applicable |

|---|---|

| At what stage of writing did you use AI tools? | |

| a. Why did you use it at that particular stage? b. Why didn’t you use it at all? |

|

| If you used AI, describe the strategy you used for prompting AI. | |

| What is your opinion on the use of AI in (academic) writing? |

Action research cycles.

| Cohorts by semester | Number of students per cohort |

|---|---|

| Autumn 2023 | 19 |

| Spring 2024 | 19 |

| Autumn 2024 | 40 |

| Total number of students | 78 |

The reflections had the following form:

The action research was conducted in three cycles, during the autumn semester of 2023, spring semester of 2024 and autumn semester of 2024. During the first two cycles, the cohorts consisted of 19 students during each of the periods. The last cycle was carried out on a larger group of 40 students.

The first two cycles explored how students utilize GAI tools in writing tasks with focus on their awareness, usage patterns and reflections regarding GAI tools in academic writing. As mentioned earlier, minor adjustments were made to the methodology during the third, final cycle, specifically in the instructor’s intentional disclosure of their own teaching practices in the sessions leading up to the task. These changes were intended to enhance the reflective process, encourage critical use of the tools, and improve the overall learning experience. However, they may have also influenced students’ decision to use GAI in their writing, particularly those who might not have considered it had they not been aware of the instructor’s positive attitude toward the tool.

4 Findings from action research: student use of GAI in writing

In the autumn semester of 2023, 12 out of 19 students refrained from using GAI tools, citing reasons such as confidence in their own writing abilities (11 students) and a general dislike for GAI (1 student). Among the seven students who used GAI tools, their purposes varied: two used them to begin the process of writing (brainstorming), three during the process of writing for structuring their writing and vocabulary improvement, and two for final edits.

By the spring semester of 2024, GAI usage among students had increased. Eight students began their writing with GAI assistance, three used it for final revisions and eight did not use it at all. Students reported various strategies for using GAI tools, including comparing AI-generated text with their own, seeking research assistance while critically revising the output, brainstorming ideas, creating initial drafts for inspiration and improving text structure. Those who avoided GAI tools primarily felt confident in their independent abilities.

When reflecting on prompting strategies, students highlighted the importance of specificity and interactivity in their prompts. Their strategies included requesting detailed outputs, asking for corrections or additions and refining prompts iteratively to improve the results. Suggestions such as simplifying sentences, incorporating collocations and rewriting unsatisfactory outputs were frequently mentioned.

Students’ reflections revealed a nuanced understanding of GAI’s benefits and limitations. Commonly mentioned advantages included improving vocabulary range, aiding with grammar, polishing texts and offering inspiration when creativity faltered. However, some expressed reservations, such as distrust of GAI reliability, a preference for their own work or an aversion to reliance on such tools. Several students emphasized responsible use, noting that excessive reliance could lead to inefficiencies or hinder the development of independent writing skills.

In the autumn semester of 2024, when the action research was extended to a larger group of 40 students to observe potential developments in attitudes and practices, the results showed a noticeable decrease in students who avoided GAI tools entirely, with only 12 out of 40 reporting no usage. Twenty students used GAI tools after drafting, seven relied on GAI to begin writing and one utilized GAI throughout the entire writing process.

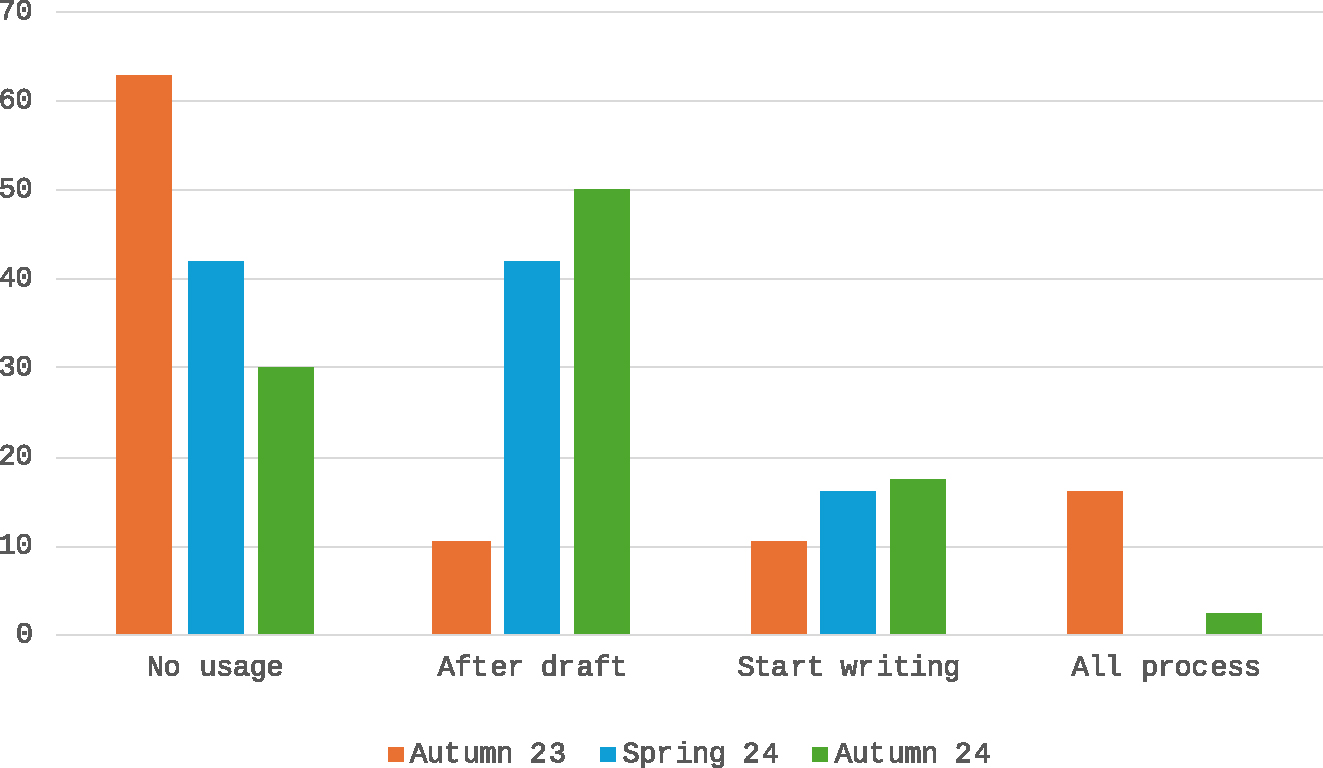

Figure 1 below shows the percentage increase in students’ choice to use GAI, with a noticeable shift in time toward using the tools after drafting to refine their final written product. The instructor wonders whether this trend reflects students’ growing inclination to use GAI as it becomes more accessible over time or if it is a result of the pedagogical approach behind the action research experiment, as explained earlier in the text.

Percentages of students using GAI tools for various strategies.

In Figure 1, the chart illustrates percentages of students using GAI tools for various strategies across the three terms. The reasons for not using the GAI in writing do not undergo significant change, with students citing reasons like lack of trust, lack of experience, confidence in their ability to work without help, joy in their own writing or ideological opposition to these tools. Accordingly, students prompted for grammar and structure improvements, synonyms, clarity, spelling, coherency, formatting, linking words, translate, make this more formal, brainstorming a name of a law firm.

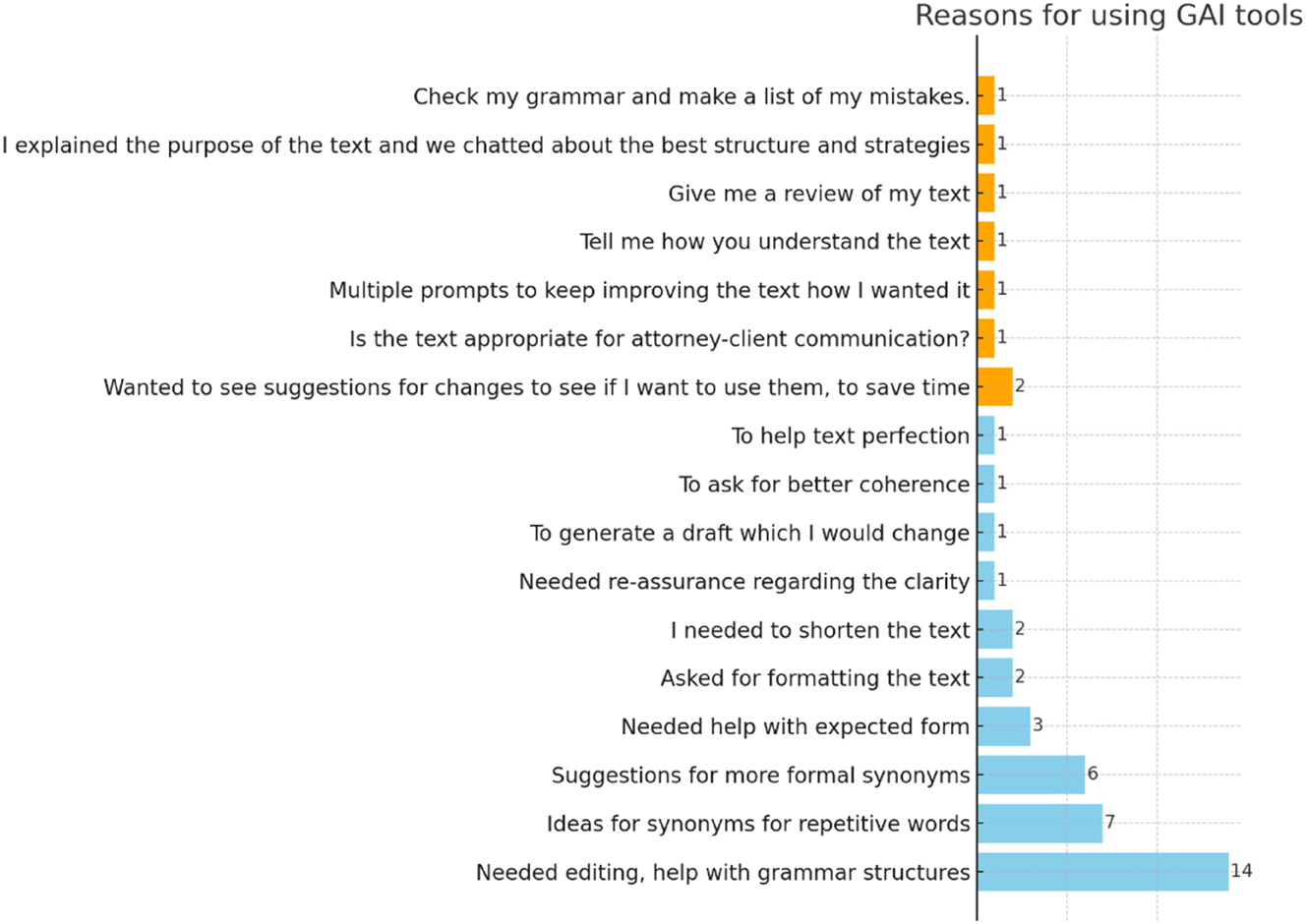

However, students are beginning to use the tool not only as another instrument to make life easier but also as a learning resource. A new element emerging from student feedback on their prompting is the adoption of strategies that reflect a shift toward active learning. Students’ reflective responses highlighted evolving strategies, moving beyond practical assistance to include learning-oriented uses. For example, students used GAI tools to identify and list personal grammar mistakes, evaluate the clarity and understanding, requesting text reviews, discussing structure and purpose, ensuring appropriateness for specific contexts (e.g., attorney-client communication), evaluating suggested changes for efficiency, and iterating with multiple prompts for continuous improvement.

These strategies may indicate a shift toward leveraging GAI tools as active learning aids rather than mere convenience tools. This raises the question of whether this shift is linked to improved teacher instruction, particularly through the detailed discussion of effective use of GAI in class, aided by the instructor’s own examples of GAI use and the discussions of the rationale behind its application. The explicit sharing, discussions with students and reflections of these practices may have helped students see GAI as a tool for active learning, enhancing their understanding and encouraging more reflective use of the technology. However, they may have also entered the course as advanced users of the tools.

In Figure 2, the horizontal bar graph illustrates the distribution of students’ reflections on specific prompting strategies used with GAI tools in Autumn 2024. The blue bars indicate prompts that help to improve the writing while the orange bars indicate the prompts that help to improve the writer.

The distribution of students’ reflections on specific prompting strategies used with GAI tools in Autumn 2024.

When asked to reflect on the broader implications of GAI use, students expressed a wide range of perspectives. Negative feedback included concerns about ethical transparency, reliability of AI-generated content and overreliance on GAI for simpler tasks. Conversely, students also acknowledged GAI’s value for enhancing vocabulary, improving grammar, streamlining the writing process and providing feedback. Positive opinions emphasized the role of GAI as a helpful “study buddy” or a tool to gain new perspectives on writing. The distribution of student answers is the following:

Wouldn’t use it for writing something instead of me (8)

Great for the final touch and assurance (7)

Dangerous and tricky (5)

A great tool to expand your vocabulary and grammar (5)

Mentioning ethical issues like transparency (4)

Fast inspiration (3)

Not good for content reliability (2)

Prompting takes longer than writing (2)

Good only for the boring, simple tasks (2)

Improves the flow of your text (2)

Good for summaries when you have no time to read a long text (2)

Only for lazy people (1)

AI tone can be felt in writing (1)

Exciting yet terrifying (1)

A good servant but a bad master (1)

A tool for real life but not for university studies (1)

Hard to resist the temptation (1)

Let’s stay critical (1)

Can give you another perspective on your text (1)

A good partner for feedback (1)

The results suggest that students are cautious yet curious about GAI’s capabilities. While some students acknowledge their reservations and emphasize its pitfalls, such as ethical concerns and reliability issues, others highlight its practicality in refining their writing. The varied distribution of responses reflects a nuanced understanding of GAI’s strengths and limitations, underscoring its potential as both a supportive tool and a source of debate in academic and personal contexts.

5 Implications for learning and conclusions

The findings tentatively indicate that many students are capable of integrating GAI tools into their learning strategies effectively and are increasingly using them. They use GAI not only to enhance the quality of their writing but also to improve their skills, such as expanding their vocabulary, refining grammar, understanding text structure and polishing their formal style. By prompting for detailed feedback, seeking explanations and iteratively improving their outputs, students demonstrate the ability to engage with GAI, as Escalante et al. (2023) suggest, as a “more knowledgeable other”, aligning with Vygotsky’s concept of guided learning.

This action research explores how students’ engagement with GAI evolves from mere convenience to an integral learning companion. Initially, if students used GAI at all, they may have seen it merely as a tool to simplify writing tasks but with more experience with the technology, they began to see its potential as a study buddy, learning companion or the more knowledgeable other. This shift reflects a more active engagement with GAI, where students are not just relying on GAI for quick fixes but are reportedly using it to improve their writing skills, analyse and refine content and even deepen their understanding of language and structure.

The evolving use of GAI tools in this context suggests a shift from passive to active learning, in which students assume a more reflective and strategic role in their development as writers. Rather than simply serving as a tool for polishing final drafts, GAI is becoming embedded in the writing process offering structured suggestions and feedback. This trend signals a transition toward using GAI as a learning aid – something that facilitates students’ cognitive processes and provides them with immediate feedback, which can ultimately enhance their learning experience.

Beyond the growing tendency to engage with technology reflectively in support of academic writing and language learning, the data collected across the period of eighteen months reveal another notable shift. Students seem to increasingly use GAI tools after drafting to refine their final written product rather than at the beginning of the writing process. This trend aligns with tentative findings suggesting that students are not using GAI to replace their own writing but rather as a tool for responsible and ethical enhancement. The instructor questions whether this trend stems from increased accessibility of GAI tools over time or is influenced by the pedagogical approach of the action research experiment.

The findings of this study suggest a growing role that GAI tools play in the academic writing process, offering both opportunities and challenges for students. While many students recognize the value of these tools in overcoming common hurdles like writer’s block, enhancing vocabulary and supporting the brainstorming process, the study also shows their concerns about the potential impact on their own creativity, individuality and the authenticity of their academic voice. These concerns are consistent with broader discussions within the literature on the use of GAI in educational contexts, highlighting the tension between innovation and preservation of academic integrity (Gilburt 2023; Lingard 2023; Rebolledo Font de la Vall and Gonzalez Araya 2023).

Thus, one key takeaway from the study is the need to balance GAI use with fostering students’ authentic voices and creativity. While these tools offer significant potential to enhance writing, educators must remain cautious of the risks associated with over-reliance on technology. GAI should serve as a complement to students’ intellectual and creative processes rather than a replacement. To achieve this, clear guidelines on responsible use are essential, addressing academic integrity, transparency, and ethical considerations. Ongoing exploration into the pedagogical implications of GAI integration is important, ensuring that its use enhances learning without diminishing students’ engagement, critical thinking, and writing development.

Furthermore, the action research suggests that transparency in the instructor’s use of GAI may play a role. In the final cycle of the action research, the instructor’s open sharing of their own experiences with GAI tools – whether for lesson planning, content creation or class administration – helped to create a collaborative environment in which students could feel more comfortable using and discussing GAI themselves. This transparency seems to have built trust and reinforced the idea that GAI, when used ethically and responsibly, can be a powerful tool for enhancing both teaching and learning. It also opened the door for deeper discussions on the ethical implications of GAI use in education, encouraging students to critically reflect on their own use of these technologies.

In the last cycle of the experiment, the instructor intentionally reinforced this aspect of the action research, mainly for pedagogical reasons. From this study’s perspective, this may have influenced students’ choices to use GAI in their writing, as well as their reflections through metacognition on what is desirable. However, students openly expressed reservations about GAI when considering its broader implications. Further cycles following the same pattern would be beneficial to observe future developments in students in this respect.

This action research also aims to contribute, in a small way, to closing the gap in current literature regarding the specific role of GAI in academic writing, offering actionable insights for educators who wish to incorporate GAI tools into their teaching practices. It provides a framework for understanding students’ evolving relationship with these technologies, shifting from text-focused to learner-oriented usage, while sharing practical pedagogical strategies for fostering responsible and effective use.

The small scope of this study, nevertheless, limits the generalizability of its findings. The action research was conducted with Czech and Slovak law students during their Legal English course, a specialized ESP program. Due to the current position of the practitioner, creating balanced, large cohorts was not possible. The student groups were small, consisting solely of Czech and Slovak law students of roughly the same age and level of proficiency in English, making the cohort homogeneous. The author is aware that although these factors simplify some issues for the instructor, they also limit the generalizability of the present action research. Similar experiments would need to be conducted with larger student cohorts, including participants from diverse cultural backgrounds and various ESP fields. However, despite these limitations, the tentative findings can offer insights and contribute to the ongoing discussion on the use of GAI in ESP teaching.

Moving forward, it would be interesting to explore whether similar developments can be observed across other areas of ESP, in different cultural contexts, and potentially more broadly in university-level academic writing courses. Such investigations could provide valuable insights into the generalizability of the findings and how GAI tools might influence writing practices in various educational settings.

Future small-scale research connected to the current action research should expand the sample size, examine the long-term effects of GAI integration in writing, and explore ways to better align these tools with learning objectives specific to the given ESP field to maximize their educational value. In response, the author of this action research, despite being limited by the specific ESP context, plans to increase the cohort size and incorporate additional reflective questions regarding students’ use of GAI tools prior to the course. This will help assess whether teacher instructions meaningfully influence students’ use of GAI and whether students enter with stronger skills over time, leading to positive shifts in their engagement with these tools.

References

Escalante, Juan, Austin Pack & Alex Barrett. 2023. AI-generated feedback on writing: Insights into efficacy and ENL student preference. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00425-2 (accessed 8 September 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Foltynek, Tomáš, Sonja Bjelobaba, Irene Glendinning, Zeenath Reza Khan, Rita Santos, Pegi Pavletic & Július Kravjar. 2023. ENAI recommendations on the ethical use of artificial intelligence in education. International Journal of Educational Integrity 19. 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40940-023-00123-1 (accessed 9 August 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Gilburt, Iona. 2023. A machine in the loop: The peculiar intervention of artificial intelligence in writer’s block. New Writing 21(1). 26–37.10.1080/14790726.2023.2223176Suche in Google Scholar

Hutchinson, Tom & Alan Waters. 1987. English for specific purposes: A learning centred approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511733031Suche in Google Scholar

Ingley, Spencer J. & Austin Pack. 2023. Leveraging AI tools to develop the writer rather than the writing. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 38(9). 785–787.10.1016/j.tree.2023.05.007Suche in Google Scholar

Labadze, Lasha, Maya Grigolia & Machaidze Lela. 2023. Role of AI chatbots in education: Systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 20. 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00425-2 (accessed 9 August 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Lewin, Kurt. 1946. Action research and minority problems. In Gertrud Weiss Lewin (ed.), Resolving social conflicts, 34–46. New York: Harper & Row.10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.xSuche in Google Scholar

Lingard, Lorelei. 2023. Writing with ChatGPT: An illustration of its capacity, limitations, and implications for academic writers. Perspectives on Medical Education 12(1). 261–270.10.5334/pme.1072Suche in Google Scholar

Masaryk University. n.d. Statement on the application of artificial intelligence in teaching at Masaryk University. Available at: https://www.muni.cz/en/about-us/official-notice-board/statement-on-the-application-of-ai (accessed 12 September 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

McIntosh, Paul. 2010. Action research and reflective practice. Abingdon: Routledge.10.4324/9780203860113Suche in Google Scholar

Meniado, Joel, Duong Thi Thu Huyen, Nopparat Panyadilokpong & Pannaphatt Lertkomolwit. 2024. Using ChatGPT for second language writing: Experiences and perceptions of EFL learners in Thailand and Vietnam. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 7.10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100313Suche in Google Scholar

Pack, Austin & Jeffrey Maloney. 2024. Using artificial intelligence in TESOL: Some ethical and pedagogical considerations. TESOL Quarterly 58(2). 1007–1018.10.1002/tesq.3320Suche in Google Scholar

Rebolledo Font de la Vall, Roxana & Fabian Gonzalez Araya. 2023. Exploring the benefits and challenges of AI-language learning tools. International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention 10.10.18535/ijsshi/v10i01.02Suche in Google Scholar

Weber-Wulff, Debora, Alla Anohina-Naumeca, Sonja Bjelobaba, Tomáš Foltýnek, Jean Guerrero-Dib, Olumide Popoola, Petr Šigut & Lorna Waddington. 2023. Testing of detection tools for AI-generated text. International Journal of Educational Integrity 19. 26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40940-023-00145-x.Suche in Google Scholar

Werdiningsih, Indah, Marzuki & Diyenti Rusdin. 2024. Balancing AI and authenticity: EFL students’ experiences with ChatGPT in academic writing. Cogent Arts & Humanities 11(1).10.1080/23311983.2024.2392388Suche in Google Scholar

Zhou, Yongchao, Andrei Ioan Muresanu, Ziwen Han, Keiran Paster, Silviu Pitis, Harris Chan & Ba Jimmy. 2023. Large language models are human-level prompt engineers. In International conference on learning representations 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40940-023-00145-x (accessed 9 August 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- 10.1515/cercles-2025-frontmatter2

- Introduction

- Language learning across cultures and continents: exploring best practices of dialogue, collaboration and innovation

- Research Articles

- Students’ perceptions of a sense of belonging in Language Centre courses – What role do teachers play?

- Use of ePortfolios in EAP classes to facilitate self-efficacy through the improvement of creative, organizational, reflective, revision and technological skills

- Boosting learner autonomy through a learner diary: a case study in an intermediate Korean language class

- Examining the (in)accuracies and challenges when rating students’ L2 listening notes

- The relationship between English Medium Instruction and motivation: a systematised review

- Generative AI in teaching academic writing: guiding students to make informed and ethical choices

- Developing writing skills and feedback in foreign language education with chatGPT: a multilingual perspective

- Activity Reports

- Fostering sustainability literacy and action through language education: perspectives and practices across regions

- Receptive communication skills to support inclusive learning in the multilingual classroom: a workshop for university teaching staff

- The challenge of LSP in languages other than English: adapting a language-neutral framework for Japanese

- Promoting autonomous learning amongst Chinese learners of Japanese – introducing flipped learning and learner portfolios

Artikel in diesem Heft

- 10.1515/cercles-2025-frontmatter2

- Introduction

- Language learning across cultures and continents: exploring best practices of dialogue, collaboration and innovation

- Research Articles

- Students’ perceptions of a sense of belonging in Language Centre courses – What role do teachers play?

- Use of ePortfolios in EAP classes to facilitate self-efficacy through the improvement of creative, organizational, reflective, revision and technological skills

- Boosting learner autonomy through a learner diary: a case study in an intermediate Korean language class

- Examining the (in)accuracies and challenges when rating students’ L2 listening notes

- The relationship between English Medium Instruction and motivation: a systematised review

- Generative AI in teaching academic writing: guiding students to make informed and ethical choices

- Developing writing skills and feedback in foreign language education with chatGPT: a multilingual perspective

- Activity Reports

- Fostering sustainability literacy and action through language education: perspectives and practices across regions

- Receptive communication skills to support inclusive learning in the multilingual classroom: a workshop for university teaching staff

- The challenge of LSP in languages other than English: adapting a language-neutral framework for Japanese

- Promoting autonomous learning amongst Chinese learners of Japanese – introducing flipped learning and learner portfolios