Abstract

Drawing on the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), this study explored how writing a learner diary impacts students’ ability to learn autonomously in an intermediate Korean language class. Researchers conducted a qualitative analysis involving nine participants who used weekly learner diaries, questionnaires, and exit interviews. The findings revealed that through a learner diary, students carried out a series of self-regulated acts, such as setting a goal, searching for learning resources, assessing their performances, and expressing a sense of accomplishments, which boosted their overall confidence. While writing a weekly learner diary, students’ learning behaviors have undergone to satisfy the three key elements of SDT, autonomy, competence, and relatedness, resulting in students’ increased motivation to learn Korean. More importantly, the result was confirmed consistently regardless of individual students’ level of proficiency. Initially thought of as a difficult task, all participants began to enjoy writing a learner diary, and the writing a diary in the target language was more enjoyable and rewarding as they continued into the middle of the semester and thereafter. Positive feedback and encouragement from the teacher also played a crucial role in enhancing the students’ self-efficacy. The participants reported that the diary was accountable for improving their autonomous learning.

1 Introduction

During the Covid-19 pandemic, many students experienced increased anxiety and depression due to isolation, which negatively affected their motivation to learn. Researchers discovered that students’ motivation during online learning in the pandemic was decreased (Avila and Genio 2020). The important task entrusted to educators is to increase students’ motivation and to bring out students’ potential to its full capacity and find ways for students to reflect on their own learning.

Learner autonomy, a key concept derived from Social Cognitive theory, has played an important role when discussing motivation. Research revealed that students are motivated when they are voluntarily involved in learning and engaged in self-relevant activities (Noels et al. 2019). Students also become more self-determined and self-regulated when they have increased autonomy, competence, and relatedness to others in learning (Ryan and Deci 2017). This study explores students’ autonomous learning in relation to the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) through a learner diary writing activity in an intermediate Korean language class.

2 Literature review

2.1 Learner autonomy

The concept of learner autonomy has been widely explored in literature. Holec (1981: 3) introduced learner autonomy and defined it as “the ability to take charge of one’s own learning.” This concept involves a variety of skills, such as setting learning goals, selecting learning strategies, and assessing learning progress. He believed that the main role of teachers was to facilitate learners’ independency by helping them in building their self-managing skills. The learner autonomy has been further discussed by many scholars (e.g. Benson 2001; Little 1999; Morrison 2002; Riley 1987) and implemented in foreign language teaching to help students be more responsible in their own learning. Riley (1987) discusses autonomy as the learner’s ability and willingness to identify learning needs, to plan their learning (selection of materials and study strategies), to monitor learning progress, and to evaluate progress.

Little (1991) emphasized learner autonomy in relation to critical reflection and social interaction. According to Little (1991: 4), learner autonomy is “a capacity – for detachment, critical reflection, decision-making, and independent action.” In other words, students have the flexibility to plan and manage their own learning based on their needs, interests, and abilities. Little (1996) further emphasizes that critical reflection relies on the individuals’ capacity to fully engage and critically reflect during social interactions.

Benson (2001) described autonomy as an individual’s ability to manage one’s important aspects of learning, driven by a learner’s desire, capability, and freedom to exercise control. He argued that autonomy is fostered by the social constructivism and that learners build knowledge not by working independently but by actively engaging with others. Through these interactions, learners are able to reflect, identify weaknesses and integrate information and become proactive in their own learning.

2.2 Self-determination theory

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) proposes that people have an innate curiosity to explore and master new situations with their own autonomy and that all humans have inherent psychological needs that must be satisfied in order to develop and flourish (Noels et al. 2019). This theory states that extrinsic rewards, such as monetary compensation, or prizes do not necessarily enhance students’ intrinsic motivation. Such tangible extrinsic rewards in fact undermine the students’ intrinsic motivation (Deci et al. 1999). Extrinsic rewards are not successful, especially when attempting to increase students’ autonomous learning because it pressures students to act in a desired behavior, and in this way, students are no longer learning with intrinsic motivation.

SDT identifies three innate psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These are crucial for fostering intrinsic motivation and well-being. Autonomy involves self-directed actions and freedom of choice; competence entails feeling effective and meeting challenges; and relatedness encompasses feeling connected within a group. These needs are inherent, and students’ motivation and performance are significantly impacted by the fulfillment of these needs. SDT highlights the importance of creating supportive classroom environments that nurture autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

2.3 Learner diary

The impact of the use of diaries on promoting students’ autonomy has been widely explored (Dam 2018; Ma and Oxford 2014; Porto 2007). Bailey and Ochsner (1983: 189) state that diaries are narratives to record the learner’s experience of a target language learning including “affective factors, language learning strategies, and his own perceptions.” Little (1991) characterizes learner diaries as a hard medium for students to record their reflections on the learning process so that their thoughts are not lost. Dam (2000: 32) states learner diaries as a “tool for awareness raising and genuine, authentic language use.”

In language learning diaries, learners document information and reflections on various aspects of their learning experience. This includes their reactions to a class in general or its methodology (Ruso 2007) and the activities they have undertaken to learn the language outside the classroom (Halbach 2000). Litzler and Bakieva (2017) explored the use of learning logs in a university EFL class to see how students reacted to this writing activity. The results showed that most students had a positive response, benefiting their learning strategies and learner autonomy. However, a few students also found that writing the logs demotivated them or was time-consuming.

According to Oxford et al. (1996), learning diaries are valuable tools for self-reflection. They help learners build confidence, understand challenging materials, and come up with new ideas. Additionally, these diaries are great for self-assessment because they allow learners to explore their emotions, social interactions, and thinking processes. According to Nedzinskaitė et al. (2006), language learners’ self-assessment facilitates an independent learning skill which ultimately promotes learners’ autonomy.

This research project explored how the learner autonomy is changed through learner diary writing practices through the lens of SDT in the post pandemic era. Researchers previously have investigated the impact of using a learner diary on students’ autonomous learning, but little research has been conducted in the context of Korean language learning. To fill this gap, two research questions were posed in this study:

What kinds of autonomous learning behaviors were promoted through the practice of writing a learner diary?

How did the activity of writing a learner diary affect students’ motivation for learning Korean?

3 Methodology

3.1 Research site and background

The research was conducted using a qualitative method at The Ohio State University in the U.S. The data was collected from one of the third-year Korean courses, 5th semester Korean. This class is a sequenced course in a 4-year curriculum for students who are mostly majoring or minoring in Korean. The 5th semester Korean was designed for students to reach the solid intermediate level proficiency defined by ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines (2012) by the end of the semester. The 5th semester of Korean language course was selected for the research because learners at this level need to invest substantial time both in and out of class to obtain the intermediate level proficiency. They were chosen also because students at this level typically feel slow progression compared to the beginning level. Therefore, many students tend to lose interests and deeper motivation for learning. Motivating oneself at the intermediate level to advance the linguistic proficiency into the advanced level is difficult because the process takes a long time, and perceiving continuous self-improvement seems to be almost impossible. This is especially true for the Korean language learners in the U.S. According to the Foreign Service Institute (FSI), the Korean language is classified as Category IV (2017), and this category is declared as exceptionally difficult for native English speakers, which also is the most difficult language to master.

The research period occurred during the first semester when in-person classes were fully resumed after the students previously experienced three semesters of primarily isolated online classes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. To accommodate students’ rising emotional needs within this context, a learner diary was adopted as a tool in hopes to reboot students’ motivation and ultimately foster autonomous learning.

3.2 Participants

All enrolled students were invited for research upon the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Nine out of 18 students voluntarily agreed to participate in this research. The participants’ background survey was collected in the first week of the semester. The participants varied in their proficiency and linguistic skills within the intermediate level. All participants previously had at least 4 semesters of Korean learning experience in the university, and two participants had more exposure to Korean language and culture by growing up in a Korean speaking family. The participants’ motivation and goal for learning Korean varied as summarized in Table 1. Pseudonyms are used for all participant names.

Participants’ background information.

| First language | Major | Minor | Length of studying Korean | Motivation of learning Korean | Goal of learning Korean the current semester | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allison | English | 1. Korean 2. Biochemistry |

None | 2nd semester at college, (grew up in Korean family) | To communicate without help from parents or Korean friends when traveling to Korea | Be more proficient in speaking and writing |

| Amy | English | Korean | None | 4 semesters | Want to teach English in Korea. Want to communicate with people. | Be able to create long sentences and wanted to improve listening |

| Caroline | English | Strategic communications | 1. Korean 2. Business |

4 semesters | Enjoy learning foreign languages and wanted to challenge herself/likes Korean culture | Be proficient in all aspects of the language, to improve speaking speed |

| Hannah | English | Psychology | Korean | 4 semesters (grew up in Korean family) | Want to communicate better with family | To be able to speak longer sentences with more natural sounding |

| Kelly | English | 1. Korean 2. Security & intelligence |

1. History 2. Studio art |

4 semesters | Loves learning a language and culture Interest in Korean music |

To improve speaking and writing. |

| Morgan | English | International studies | 1. Korean 2. Economics |

4 semesters | Learn Korean to understand songs/dramas | Want to improve conversation skills |

| Molly | Luganda | International studies | Korean | 4 semesters | Loves K-pop | Improve listening and speaking |

| Sophia | English | Biology | Korean | 4 semesters | Interest in pop culture | Be better at listening comprehension |

| Sabrina | English | Computer and information science | 1. Korean 2.Neuroscience |

4 semesters | Interest in K-pop | To improve listening comprehension/speaking |

The students’ learner diary entries were collected once a week for 14 weeks on every Monday. At the beginning of the course, instructions on a learner diary were provided. The instruction encouraged the participants to think, describe, or reflect on their learning actions and contained specific questions for the participants to respond to and write about, and what they learned each week (see Appendix). Through the diary writing activities, students were primarily asked to reflect on their Korean learning performance and identify their strengths and weaknesses to set their own learning goals that they want to accomplish. The students were encouraged to write what they did to accomplish their goals.

To achieve their goals, students were advised to use available online resources to practice the target language outside the classroom during the semester. A wealth of studies has shown the positive impact of the Internet use on a foreign language learning (e.g. Bozorgian and Shamsi 2022; Godwin-Jones 2019; Lee 2019). For example, podcasts have been identified as useful resources supplementing the insufficient authentic language practices in traditional classroom settings (Bozorgian and Shamsi 2022). In addition, according to Godwin-Jones (2019), the use of mobile apps and computer software increased learners’ interest in language learning and can therefore effectively enhance learner autonomy.

Upon the beginning of the project, a small size (“5.5 × 8.5”) paper diary notebook was given to each participant for a data recording purpose. Most diary entries were a half to one page long. The teacher returned students’ diaries with the feedback on the next day. The feedback included answers to questions if there were questions asked, suggestions for study methods, occasional compliments, quick error corrections in the use of the target language, encouragement if the teacher sees that students have difficulties, and recommendations and suggestions for further learning tools in response to what was written in the students’ diary.

Initially, students were allowed to choose between English and Korean for writing the learner diary to help them feel more comfortable with the new task as they had relatively limited experience writing in Korean to express their feelings in this format. However, if the diary was originally written in English, the teacher suggested the students gradually write in Korean as the semester progressed. This instruction was given as a part of the teacher’s feedback to encourage students to develop their writing skills in the target language.

3.3 Data collection

During the first week of the semester, a questionnaire on the participants’ linguistic and demographic background information was offered to the students and their responses were collected. Additionally, responses to two more questionnaires asking about the participants’ experience of writing a learner diary were collected, once in the middle of the semester and once at the end of the semester. For further exploration on the diary writing practice and free-flow thought exchanges, a semi-structured, in-person, 30-minute exit interview was conducted individually. The interviews were audio recorded and later transcribed for analysis.

3.4 Data analysis

In this research, thematic analysis within the framework of SDT was performed. Emerging themes were found to identify which kind of aspects of students’ autonomous learning appeared from the students’ responses from the questionnaires, contents of the learner diary, and the exit interviews. The initial emerging themes were quickly identified as setting a goal, identifying strength/weakness, searching for a study method, etc. The emerging themes were coded based on three elements of SDT- Autonomy, Competence and Relatedness – and each theme was counted to identify how frequently it occurred. A student’s account was coded twice if they belonged in two categories. The questionnaires and interview transcription data were also thematically analyzed in the same method under the SDT’s framework.

4 Findings

A series of self-regulated learning behaviors aligned with Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness in the framework of SDT were found in the diary and the interviews. The findings section is organized by reporting more pronounced and frequently observed themes to lesser frequently appearing themes to illustrate various aspects of participants’ autonomous learning. The themes include (1) Increased sense of autonomy, (2) Enhanced competence, (3) Increased motivation, (4) Building a learning supportive community, and (5) Growing into an active learner. These themes explained how the learner diary activities resulted in positive outcomes for the students’ learning and how such self-reflective writing activity brought fundamental changes in how students view their own language learning processes.

4.1 Increased sense of autonomy

The participants continuously exhibited autonomous behaviors and monitored their learning progress while writing the learner diary. From analyzing the diary entries, varying descriptions of students’ autonomous actions appeared at the highest rate among the three SDT elements. While consciously reflecting their learning, the students evaluated their own language skills and class performances and identified strengths and the areas to improve. This identification process often led to the stage of a goal setting. After setting a goal, the participants diligently searched for a study method or a learning tool that would enable them to achieve their goals. Table 2 shows the summary of frequency counts of the codes displaying autonomous learning behaviors in the diary data.

Codes related to autonomy of SDT in the diary entries.

| Codes | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Assessing performances Identifying weakness Identifying strength |

64 57 7 |

| Setting a learning goal | 141 |

| Searching for a study method | 16 |

| Searching for a learning tool | 4 |

| Practicing outside of class | 88 |

It was also found that monitoring their learning progress by illustrating their actions in the learner diary motivated participants to change their behaviors which, in turn, enhanced students’ sense of autonomy. The following two quotes from students’ questionnaires demonstrate how they felt the heightened sense of autonomy. Kelly, one of the participants, reported “It makes me look at what I did and if I didn’t do well when I did those things I can try something else to do better. That way as I learn more complex things, I can try new strategies and see what works best for me” (Questionnaire 1). Another participant, Hannah, explained “I think the most helpful aspect of the Korean proficiency is the space for reflection and goal creating that it leads to. Without the learner diary I wouldn’t have taken the time to really check-in on my progress and think about what I could be doing to get better” (Questionnaire 1).

The participants not only monitored their learning progress but also realized that they are able to manage their learning by choosing learning materials that would support them to achieve their goals. The following is the exit interview excerpt representing how participants took initiative in their own learning after writing a learner diary.

Hannah: I think doing the diary, made me realize like how much control, I had, I have over like what I can do to learn, because I think beforehand I was just like, focused on oh I will just do my homework and just go to class and that’s good enough. But I think doing the diary and making goals, it made me think about, Oh, I can do a lot more outside of class, I think the one thing I took away is like there are a lot of resources out there and I, I can use them because I think I didn’t really use them before the diary. (Exit Interview)

The activity of the learner diary prompted Hannah to explore materials outside of class and repositioned her as the owner of her learning who created her own goals and worked towards achieving them. She took ownership of this whole process and went out to look for the learning materials outside of class that are effective and more enjoyable for her. Also, a similar comment was found in Caroline’s data about practicing Korean outside of class. She commented “It is interesting for me to track my progress, and it forces me to find new ways to study and learn material when previously I would just do what we learned in class. Because of the learner diary, I have found new resources outside of class that are interesting to listen to and watch to help me study” (Questionnaire 1).

When participants took the initiative to learn outside of class, their self-learning activities included writing a summary about Korean story books, listening to K-podcasts, watching K-dramas, writing a paragraph about a day in Korean, talking to a Korean friend or family, watching Korean lessons on YouTube, etc. Most participants had strong interests in the Korean pop culture, which appears to enhance their motivation for continued self-learning outside of class. The use of self-selected fun materials outside of the standard course textbooks seems to play a key role in sustaining their interest and fostering autonomous learning behaviors.

4.2 Enhanced competence

Regardless of whether weekly goals were fully accomplished or not, the learner diary activity was found to be beneficial in helping participants build confidence. This was achieved through the process of documenting their achievements and tracking the progress of their Korean skills. These learning aspects presented in the diary entries were coded into seven categories as shown in Table 3.

Codes related to competence of SDT in the diary entries.

| Codes | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Satisfaction with class performance Satisfied Unsatisfied |

91 72 19 |

| Accomplishment of weekly goals Accomplished Unaccomplished |

55 42 13 |

| Confidence | 30 |

| Challenging | 14 |

| Positive feelings toward Korean learning | 14 |

As shown in the table, positive feelings toward their learning including enjoyment, satisfaction, accomplishment and confidence led them to challenge themselves. The students were confident to go beyond their capabilities. Sabrina reported “It made me want to try other things to see if I could be even more successful, and it led me to challenge myself a bit more in regard to what I thought I was capable of” (Questionnaire 2). Caroline also mentioned “It was nice to challenge myself to do things I normally wouldn’t study outside of class. Like look up podcasts and videos and make flashcards stuff like that” (Exit Interview).

Another important finding associated with competence was the students’ realization of their capabilities. The diary assignment was initially given with the freedom of language choices between English and Korean. However, the teacher nudged students to consider switching the language from English to Korean in her feedback. Some students at first felt uncomfortable with writing the diary in Korean because the course curriculum had been heavily focused on speaking and listening, so students had less chance to practice writing. For example, Morgan felt writing self-reflective diary in Korean was an intimidating task to do because she didn’t have a such writing experience previously although she was one of the most proficient participants. The interview data revealed the realization of one’s such capability boosted confidence.

Morgan: I would say the biggest one was the second week I started writing in Korean. It was like a Oh, I can write in Korean I never really did it that much it’s always been like prompt based or like use this vocab use this grammar in the workbooks. But this time, like writing those reflections. The first week I struggled a lot. The second week was like, oh, I can do this. I think I can continue doing it and it was a big like motivation for me. (Exit Interview)

Caroline gained her confidence by discovering her capability of being able to perform this difficult task well, which she never thought it would be possible for her to do. Below is her account.

Caroline: I think when I first switch from writing to English to Korean. Yeah, for me, when I finished writing it in then specifically when I got my journal back that weekend, I read the feedback I was like, wow, this actually was not that bad. I think I was very scared at first, but once I got it back, I was like oh I’m actually like, I thought I was worse at Korean than I actually am. I second guessed myself. (Exit Interview)

The students’ confidence increased as the writing progressed with teacher’s continued feedback which often contained comments with encouragement and support. The following interview data shows how the positive feedback from the teacher enhanced student’s competence. For example, Sophia said “For the first time when I got 완벽해 [wanbyeokhae, ‘perfect’], I felt good. I was always really excited to get back, I was very excited to like read 선생님’s [sonsangnim, ‘teacher’] feedback. My immediate feedback from it, I was like, Yay. This is fun” (Exit Interview).

Based on the frequency of the codes and interview data, it was evident that participants were able to observe their capabilities through a learner diary writing that they could not have noticed otherwise. Knowing that they have the ability to perform beyond the assumed performance level increased their confidence.

4.3 Increased motivation

Not only were the students taking the ownership of their own learning and therefore enhanced their competences but students also clearly increased motivation to learn while engaging in writing a learner diary. Caroline and Morgan’s statements below directly indicate how writing a learner diary increased their motivation. They perceived the diary as a good learning companion to report their achievements to and felt a great sense of reward after achieving small goals. Caroline mentioned “It also made me set goals for myself and if I didn’t complete them, I would feel a sense of disappointment, so I think it was a good motivator” (Questionnaire 1). Morgan reported that “Reflecting on my learning did motivate me to study Korean more because if I did not do something new, I would have nothing to talk about in the diary. Writing down my accomplishments was rewarding” (Questionnaire 2).

Many students reported that they did not regularly reflect on their learning nor consider utilizing additional resources outside of class to improve and refine their Korean language skills before writing the learner diary. With the introduction of the learner diary, students increased opportunities to immerse themselves in a Korean-language environment more frequently. Hannah was a very goal-oriented student who found keeping the learner diary was a motivator to achieve her goals.

Hannah: I didn’t really think anything about learning more beyond what I learned in class and so I liked how I could be flexible with the journal because I was the one reflecting over my progress and what, and I was making my own goals for the week, and I’m someone, where like if I set a goal is important for me to reach the goal so it’s very motivating for me to like make weekly goals. (Exit Interview)

Although writing a learner diary was a part of their course assignments that could require more conscientious time investment than before, participants found it to be more fun and meaningful to themselves as they continue to be engaged in this activity. Allison and Hanna reported the following.

Allison: I think it motivated me to study more because it really forced me to reflect upon my shortcomings and highlight my biggest challenges as a learner. I think upon realizing how easy it is to simply try a new method of learning to improve on concepts that I struggled with, I was more encouraged to try a new method until I found one that fits best. Because when I found the correct one, it made learning so much easier. (Questionnaire 2)

Hannah: I think the learner diary has been a great supplementary resource that has given me motivation to invest more time in my studies that I’m sure helped my Korean retention and consumption. The learner diary has prompted a lot of reflection on my end that has given me the extra motivation to take the time to find an additional study resource online when studying or reading or watching more Korean materials outside of class that has helped me go more in depth in my studies. (Questionnaire 1)

Regular reflection through the diary writing on their successes and challenges increased students’ awareness of their skill development. This sense of accomplishment and progress played an important role in strengthening their motivation to continue learning. In this sense, the learner diary served as a catalyst for enhancing motivation.

4.4 Building a supportive learning community

Data revealed that learning behaviors regarding relatedness, such as studying with their classmates, obtaining learning resources from classmates, practicing Korean with their Korean friends and family, and asking questions to the teacher, all played an important role for achieving their goals. The participants reported different emotional connections such as comfortableness, trust, enjoyment in relation with their classmates, friends, family, and the teacher were formed through this project. This relatedness fostered their emotional strength in the learning journey.

While working on this diary project, students reported that they studied with their classmates and friends they felt comfortable with. See Table 4.

Codes related to relatedness of SDT in the diary entries.

| Codes | Total |

|---|---|

| Studying with classmates/friends | 24 |

| Talking to teacher (question/comments) | 11 |

| Talking to family (heritage) | 2 |

To accomplish their weekly goals, participants searched for materials available on the Internet. They ranged widely from simply watching K-dramas on occasion, listening to Korean podcasts, searching for interesting Korean webtoons to studying Korean with a book called Talk to me in Korean (a book and the associated popular YouTube learning contents), reviewing various educational and non-educational YouTube episodes in Korean, and reading available Korean blogs and vlogs, etc. The additional materials went beyond class materials depending on what the students found interesting or worthy of exploring. An expansion of fun and exciting language samples and varying learning materials that the participants ran into were often enthusiastically shared with classmates. The following interview shows how the shared information with classmates influenced the student’s learning. During the exit interview, Caroline specified “Sabrina, she told me about it like a couple weeks into the semester. So, I just started this semester, but then when I actually started listening to it, I was like oh this is helpful and so I listened to, like, a bunch of episodes so it was like a lot of content but a short amount of time” (Exit Interview).

As Caroline specifies in her explanation above, the learner diary activity encouraged students to talk about and share interesting learning resources that they have found. Sometimes this kind of accidental learning expanded the students’ view on what possibly they could do in Korean. Also, this kind of connection truly bonded the students and made the learning special, and the students felt like they belong to each other in a bigger and more meaningful learning community. Additionally, students reported that the diary was a special space where they can discreetly converse with the teacher without necessarily let other students in class notice about them. Some students used it as a communicating tool with the teacher, and in turn, this practice helped them to be closely connected to the teacher. The teacher also benefited by getting to know about the student issues that they had in that week in a relatively calm environment through the written communication. Therefore, writing and reading the diary helped communication in both ways. See Caroline’s interview below.

Caroline: I can talk to the teacher in private, instead of face to face or even email, kind of a secret that we can have. So, if I need something or if I’m struggling, then I can just write in private [in my learner diary writing] and then the teacher knows. I think that was helpful because I feel like I did I have to outwardly say, but then the teacher would just understand that maybe I needed help that week or maybe I was doing really good or something like that, that was really helpful. (Exit Interview)

Because the diary was a channel for such regular, weekly communication, it was more personable, helping everyone to be more open to each other by talking through diaries. With this kind of internal support system, students seem to feel safe and more at ease to take risks in trying out a newly learned expression or venture into using a more complex grammar. Fostering and maintaining an open communication system with such less pressure was an indirect but much more efficient way to create a happier and more comfortable environment.

4.5 Growing into an active learner

The data indicated that the students have grown into a more active learner with the learner diary practice. Regular and periodic reflective thinking practice involved in the diary writing has positively impacted on the participants’ learning behaviors. According to the students’ account, they are now more prone to think and act consciously about their own learning compared to more passive style of learning in the past that they seemed to recall. The participating students’ attitude toward the task also changed. Many participants initially perceived this assignment as rather “tedious” and generally regarded it as a difficult task. However, as they have developed a habit of writing more regularly in a weekly cycle, the initial negative feeling has changed into more “happy” expectations about what they ought to write in the next week. Sophia’s comment illustrates this change. She reported “I was a little apprehensive at first, but I have really enjoyed writing the learner diary throughout the semester and would like to continue doing so in the future!” (Questionnaire 2).

The data collected from the students illustrate the changes that this diary writing process had brought to them. Through the correspondence on the questionnaire, Sabrina commented “I was choosing to actively study other materials outside of class to improve different aspects of my Korean and would often come into class with comments and questions to help further what I had learned on my own. I don’t think I ever did that before the learner diary” (Questionnaire 2). Hannah also mentioned “Before the learner diaries, I did not give much thought to what resources were available and what else I could do outside of class and assigned materials. By doing these journals, I was able to explore a lot of outside resources through this process and made me be more engaged and active in my studies” (Questionnaire 2).

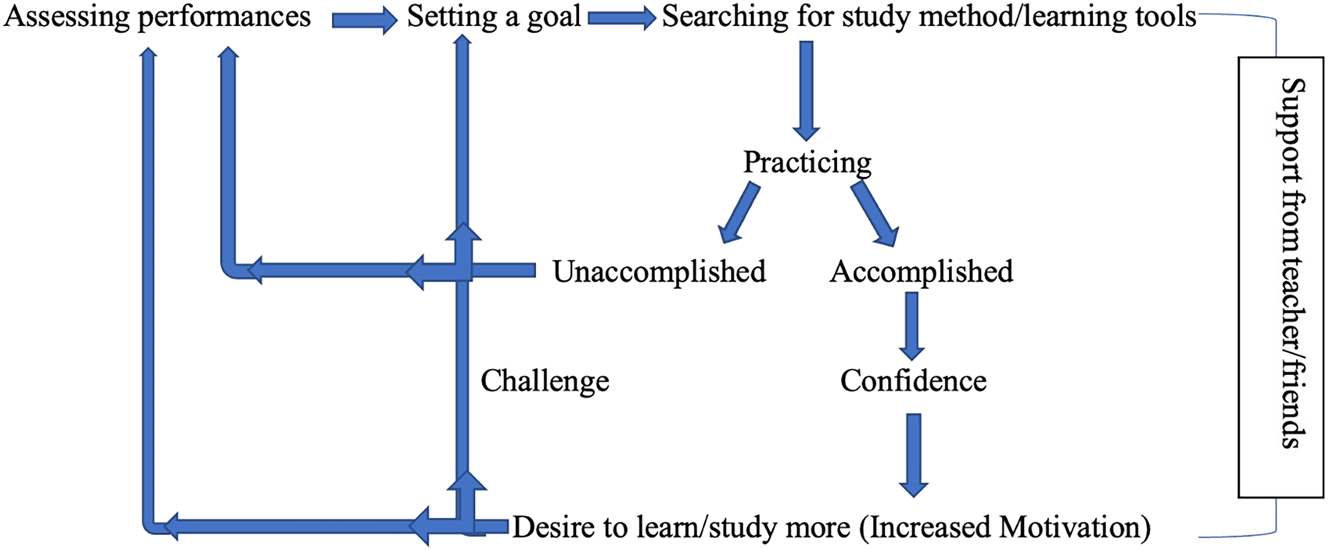

It was found that the participants started forming active learning habits by the act of writing diary. Both Sabrina and Hannah above mentioned that they had broken into a new passage of learning habits thanks to the reflective writing practice. In that sense, the action of writing a diary truly resulted in increasing students’ confidence and motivation. Additionally, there was a significant change in the growth of the affective support from a learning community. The support that they shared with one another created an unexpected synergy among the participants and they could individually and collectively grow into more self-determined learners. Overall, the findings indicated that participants became more self-determined and autonomous learners through writing the learner diary. It was identified that the development of autonomous learning was characterized as cyclic. The nature of this cyclic learning is illustrated in Figure 1.

Flow of cyclic autonomous learning.

5 Discussion

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a motivational theory suggesting that individuals can become self-determined when their needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness are satisfied (Deci and Ryan 2000). Within this theoretical framework, the findings of this study indicated that a learner diary activity increased learners’ self-regulated behaviors. The participants of this study were either Korean majors or minors who were committed and invested in studying Korean. Due to this background, all of them possessed a great deal of motivation and a degree of desire to ultimately acquire advanced proficiency in Korean when they entered the intermediate Korean class. Even though they all have such an instrumental motivational orientation driven by external rewards (Gardner and Lambert 1972), participants had not actively reflected on the strength or weaknesses of their Korean language skills nor monitored their learning progress on a regular basis until they were asked to write a learner diary. By participating in the weekly reflective writing process, the students found themselves gradually becoming more motivated to learn and genuinely wanting to improve in the language with goals, which eventually led them to engage in a number of autonomous learning behaviors.

The findings of this study revealed that the process of writing a learner diary is an effective tool enhancing a range of metacognitive skills. As many researchers in second language learning claimed, not only that learning can be enhanced by adopting metacognitive skills, but also that fostering metacognitive skills is required for learners to achieve a long-term success in their learning (Anderson 2012; Graham 2006). When the opportunity to reflect on their learning was provided to participants, their ability to take control of learning, namely autonomy (Ryan and Deci 2000), was developed as a consequence of the previously developed metacognitive skills. Engaging in the cycle of self-regulated behaviors as shown in Figure 1 raised the awareness of the students’ own learning and enabled them to be more proactive toward their learning. In addition, self-regulated behaviors were gradually internalized as the participants’ motivation. This process facilitated a change from external-driven motivation (to complete a learner diary assignment) to intrinsic motivation (to volitionally engage in their learning) which, according to Deci et al. (1991), is the most self-determined kind of motivation. Deci et al. (1991: 328) argued the intrinsic motivation is fundamental and is “the prototype of self-determination.” Students who are intrinsically motivated are more likely to engage in high-quality learning.

In this study, the participants felt increased confidence from accomplishing their goals and evaluating their skills every week. In SDT’s framework, competence is described as an ability to sufficiently accomplish a given task. Sequenced actions of setting their own learning goals, using the materials that they selected for their own needs, and accomplishing set goals were spiraled to build up their confidence to succeed. In the area of competence, participants’ self-efficacy was enhanced through the learner diary. At the beginning of the project, the majority of students were hesitant to write the diary in Korean. Only three out of nine participants chose to write in Korean. Six participants showed low-self efficacy by viewing writing a learner diary in Korean as a difficult task and initially avoided the challenge. By the middle of the semester, however, more students started to feel at ease as they practiced the action of writing more entries and gradually started switching their choice of writing in the first language to the target language when the teacher encouraged them. As such, the participants’ competence was supported by introducing a fundamentally challenging task, “thereby allowing students to test and to expand their academic capabilities” (Niemiec and Ryan 2009: 139). The teacher’s role in this process was crucial as the teacher’s positive feedback aided learners to increase their motivation. Therefore, this finding confirms Dörnyei’s (2005) statement that teachers who support autonomy promote intrinsic and self-determined motivational orientations for language learners.

Another finding that was highlighted by our research was the absence of direct relationship between autonomous learning and students’ level of proficiency. In other words, both participants of high proficiency and low proficiency became more self-determined learners as a result of writing a learner diary. Higher proficiency students seem to challenge themselves more often and use more diverse resources, but autonomous learning occurred regardless of the proficiency level.

In sum, participants in this study grew into more self-determined learners as their autonomy, competence, and relatedness were increased. Initially, writing a learner diary was not favorable for participants and was perceived as an ordeal, but at the end of the semester the participants grew to love it and later found the diary writing to be exciting, helpful, and rewarding. Therefore, as the autonomy grew, competence and self-efficacy were enhanced in the learning community where they mutually felt more meaningfully related to others.

6 Pedagogical implication and conclusion

Successful foreign language learning cannot be achieved only by the classroom instruction sharing the content knowledge. Learners’ motivation is another important factor that drives students to keep them up throughout the semester so that they mindfully invest their time and effort for the intended learning to be successful. In order to increase learners’ motivation, it is important to elevate the level of learners’ autonomy as more autonomous learners take more responsibility for their own learning and are able to stay motivated to learn. However, autonomous learning does not occur in a void. Some form of explicit instruction is required to facilitate restructuring their approaches to the learning processes. At the Language Centers or Department level, an orientation can be given to faculty and students alike earlier in the semester, outlining the importance of creating an end goal or a vision for the semester. Students should be encouraged to envision the end of the semester outcome achieved by their effort in the semester. They should be reminded that the reflective process is more than a mere thinking exercise but a great start to promote a growth mindset in language studies. We, as authors, should emphasize the importance of drawing the students’ attention to the reflective process, especially from the beginning of the language course. Indeed, this is a key to building strong learner autonomy, which ultimately results in long-term success as a learner. In addition, the Language Centers or Departments can provide occasional workshops that include teacher reflection sessions on specific activities that encourage students to reflect on their own learning practices. These workshop sessions will help teachers share their experiences and improved methodologies that could hopefully be implemented in their teaching practices.

In the classrooms, we suggest that teachers dedicate part of course credits to reflective activities such as a paper diary, a digital blog, a voice or video diary in order to help the students cultivate metacognitive skills as it is worth devoting time to nurture these skills. The suggested activities will eventually help students develop autonomy as language learners. Based on this study, the teachers’ comments on the diaries were not only helpful but also crucial because students felt that they received individualized attention to their progress. In addition, we suggest that learner diary assignments should be a low-stake assignment. In fact, learners’ autonomy can be developed by “teachers’ minimizing the salience of evaluative pressure and any sense of coercion in the classroom” (Niemiec and Ryan 2009: 139) as it was reaffirmed by the participants of this study. Finally, journaling as a low stake assignment will potentially pave the way to a safe space for communication between a teacher and a student and such genuine communication will serve to build students’ confidence and help their integral growth as a life-long learner.

Funding source: The Michael V. Drake Institute for Teaching and Learning, The Ohio State University

Award Identifier / Grant number: Research and Implication Level 1

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Michael V. Drake Institute for Teaching and Learning, The Ohio State University under Grant [Research and Implication Level 1].

Learner diary instruction

It is known to be beneficial for learners to think about what they are learning while learning. Reflecting on our own learning process makes us a conscientious learner. Let’s practice writing a weekly learner diary and document our thoughts this semester.

I want you to think about what you’ve learned over the past week and write about it. In your writing, try to also identify your overall strengths and weaknesses of Korean, and think about what you did to make the results as they were. Also, write about what you can do to improve your weaknesses.

Here are some of the questions you can ask yourself when you write a diary entry.

“Did I understand everything that I was taught in class? If not, what do I need to work on/how will I improve my understanding?”

“How was my performance (speaking/reading/writing/listening) in class? Did I do well? What did I struggle on? What can I do to do better next time?”

If you tried to work on areas that you wanted to improve, write about what you did. For example, you used Quizlet to memorize vocab. “How did it work? Did it help?” Or you did not understand the grammar point you learned last week. So, you watched a YouTube video explaining more details of the grammar. “How was the viewing experience? Did I understand the grammar better?”

“What are my strengths of Korean? What have I done to make them strong?”

What are my weakness of Korean? “What will I do to improve it?” “Has the previous study method been working well?”

You are welcome to use any learning resources on the internet. Just write what you used and how you used them to learn Korean. You can write either in English or Korean. (If you write in Korean, I will provide corrections.).

References

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. 2012. ACTFL proficiency guidelines 2012. ACTFL. https://www.actfl.org/resources/actfl-proficiency-guidelines-2012 (accessed 1 September 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, Neil J. 2012. Metacognition: Awareness of language learning. In Sarah Mercer, Stephen Ryan & Marion Williams (eds.), Psychology for language learning: Insights from research, theory and practice, 169–187. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137032829_12Suche in Google Scholar

Avila, Ernie C. & Ana Maria Gracia J. Genio. 2020. Motivation and learning strategies of education students in online learning during pandemic. Psychology and Education Journal 57(9). 1608–1614.Suche in Google Scholar

Bailey, Kathleen M. & Robert Ochsner. 1983. A methodological review of the diary studies: Windmill tilting or social science? In Kathleen M. Bailey, Michael H. Long & Sabrina Peck (eds.), Second language acquisition studies, 188–198. Boston: Heinle & Heinle/Newbury House.Suche in Google Scholar

Benson, Phil. 2001. Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Harlow: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Bozorgian, Hossein & Esmat Shamsi. 2022. Autonomous use of podcasts with metacognitive intervention: Foreign language listening development. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 32(3). 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12439.Suche in Google Scholar

Dam, Leni. 2000. Why focus on learning rather than teaching? From theory to practice. In David Little Leni Dam & Jenny Timmer (eds.), Focus on learning rather than teaching: Why and how? 38–55. Dublin: Trinity College, Centre for Language and Communication Studies.Suche in Google Scholar

Dam, Leni. 2018. Developing learner autonomy while using a textbook. In Klaus Schwienhorst (ed.), Autonomy in language learning: Learner autonomy in second language pedagogy and research – challenges and issues, 51–71. Hong Kong: Candlin & Mynard.Suche in Google Scholar

Deci, Edward L. & Richard M. Ryan. 2000. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 11. 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1104-01.Suche in Google Scholar

Deci, Edward. L., Robert J. Vallerand, Luc G. Pelletier & Richard M. Ryan. 1991. Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist 26. 325–346. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2603-4-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Deci, Edward L., Richard Koestner & Richard M. Ryan. 1999. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin 125. 627–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627.Suche in Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Zoltan. 2005. The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Suche in Google Scholar

Gardner, Robert C. & Wallace E. Lambert. 1972. Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.Suche in Google Scholar

Godwin-Jones, Robert. 2019. Riding the digital wilds: Learner autonomy and informal language learning. Language, Learning and Technology 23(1). 8–25. https://doi.org/10.64152/10125/44667.Suche in Google Scholar

Graham, Suzanne. 2006. Listening comprehension: The learners’ perspective. System 34. 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2005.11.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Halbach, Ana. 2000. Finding out about students’ learning strategies by looking at their diaries: A case study. System 28(1). 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0346-251x-99-00062-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Holec, Henri. 1981. Autonomy and foreign language learning. Oxford: Pergamon (First published 1979, Strasbourg: Council of Europe).Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Ju Seong. 2019. Quantity and diversity of informal digital learning of English. Language, Learning and Technology 23(1). 114–126. https://doi.org/10.64152/10125/44675.Suche in Google Scholar

Little, David. 1991. Learner autonomy 1: Definitions, issues and problems. Dublin: Authentik.Suche in Google Scholar

Little, David. 1996. Freedom to learn and compulsion to interact: Promoting learner autonomy through the use of information systems and information technologies. In Richard Pemberton, Edward S. L. Li, Winnie W. F. Or & Herbert D. Pierson (eds.), Taking control: Autonomy in language learning, 203–218. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.10.1515/9789882202856-016Suche in Google Scholar

Little, David. 1999. Developing learner autonomy in the foreign language classroom: A social- interactive view of learning and three fundamental pedagogical principles. Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses 38. 77–88.Suche in Google Scholar

Litzler, Mary F. & Margarita Bakieva. 2017. Learning logs in foreign language study: Student views on their usefulness for learner autonomy. Didáctica 29. 65–80.Suche in Google Scholar

Ma, Rui & Rebecca L. Oxford. 2014. A diary study focusing on listening and speaking: The evolving interaction of learning styles and learning strategies in a motivated, advanced ESL learner. System 43. 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.12.010.Suche in Google Scholar

Morrison, Bruce J. 2002. The troubling process of mapping and evaluating a self-access language learning centre. In Phil Benson & Sarah Toogood (eds.), Learner autonomy 7: Challenges to research and practice, 55–64. Dublin, Ireland: Authentik.Suche in Google Scholar

Nedzinskaite, Inga, Dana Švenčionienė & Daiva Zavistanavičienė. 2006. Achievements in language learning through students’ self-assessment. Studies about Languages 8(1). 84–87.Suche in Google Scholar

Niemiec, Christopher P. & Richard M. Ryan. 2009. Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education 7. 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318.Suche in Google Scholar

Noels, Kimberly A., Dayuma I. Vargas Lascano & Kristie Saumure. 2019. The development of self-determination across the language course: Trajectories of motivational change and the dynamic interplay of psychological needs, orientations, and engagement. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41. 821–851. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263118000189.Suche in Google Scholar

Oxford, Rebecca L., Roberta Z. Lavine, Gregory M. E. Hollaway & Amany Saleh. 1996. Telling their stories: Language learners use diaries and recollective studies. In Rebecca L. Oxford (ed.), Language learning strategies around the world: Cross-cultural perspectives, 19–34. Manoa: University of Hawaii Press.10.1515/9780824897376-003Suche in Google Scholar

Porto, Melina. 2007. Learning diaries in the English as a foreign language classroom: A tool for accessing learners’ perceptions of lessons and developing learner autonomy and reflection. Foreign Language Annals 40(4). 672–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2007.tb02887.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Riley, Phillip. 1987. From self-access to self-direction. In James A. Coleman & Richard Towell (eds.), The advanced language learner, 75–88. London: CILT.Suche in Google Scholar

Ruso, Nazenin. 2007. The influence of task based learning on EFL classrooms. Asian EFL Journal 18. 1–23.Suche in Google Scholar

Ryan, Richard M. & Edward L. Deci. 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 55. 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68.Suche in Google Scholar

Ryan, Richard M. & Edward L. Deci. 2017. Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford.10.1521/978.14625/28806Suche in Google Scholar

U.S. Department of State, Foreign Service Institute. 2017. Language learning difficulty for English speakers. https://2009-2017.state.gov/m/fsi/sls/orgoverview/languages (accessed 1 September 2025)Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- 10.1515/cercles-2025-frontmatter2

- Introduction

- Language learning across cultures and continents: exploring best practices of dialogue, collaboration and innovation

- Research Articles

- Students’ perceptions of a sense of belonging in Language Centre courses – What role do teachers play?

- Use of ePortfolios in EAP classes to facilitate self-efficacy through the improvement of creative, organizational, reflective, revision and technological skills

- Boosting learner autonomy through a learner diary: a case study in an intermediate Korean language class

- Examining the (in)accuracies and challenges when rating students’ L2 listening notes

- The relationship between English Medium Instruction and motivation: a systematised review

- Generative AI in teaching academic writing: guiding students to make informed and ethical choices

- Developing writing skills and feedback in foreign language education with chatGPT: a multilingual perspective

- Activity Reports

- Fostering sustainability literacy and action through language education: perspectives and practices across regions

- Receptive communication skills to support inclusive learning in the multilingual classroom: a workshop for university teaching staff

- The challenge of LSP in languages other than English: adapting a language-neutral framework for Japanese

- Promoting autonomous learning amongst Chinese learners of Japanese – introducing flipped learning and learner portfolios

Artikel in diesem Heft

- 10.1515/cercles-2025-frontmatter2

- Introduction

- Language learning across cultures and continents: exploring best practices of dialogue, collaboration and innovation

- Research Articles

- Students’ perceptions of a sense of belonging in Language Centre courses – What role do teachers play?

- Use of ePortfolios in EAP classes to facilitate self-efficacy through the improvement of creative, organizational, reflective, revision and technological skills

- Boosting learner autonomy through a learner diary: a case study in an intermediate Korean language class

- Examining the (in)accuracies and challenges when rating students’ L2 listening notes

- The relationship between English Medium Instruction and motivation: a systematised review

- Generative AI in teaching academic writing: guiding students to make informed and ethical choices

- Developing writing skills and feedback in foreign language education with chatGPT: a multilingual perspective

- Activity Reports

- Fostering sustainability literacy and action through language education: perspectives and practices across regions

- Receptive communication skills to support inclusive learning in the multilingual classroom: a workshop for university teaching staff

- The challenge of LSP in languages other than English: adapting a language-neutral framework for Japanese

- Promoting autonomous learning amongst Chinese learners of Japanese – introducing flipped learning and learner portfolios