The Fabrication of Cassava Silk Fibroin-Based Composite Film with Graphene Oxide and Chitosan Quaternary Ammonium Salt as a Biodegradable Membrane Material

-

Shuqiang Zhao

, Xuhong Miao

and Xinxia Yue

Abstract

A novel and excellent composite film was fabricated by simply casting cassava silk fibroin (CSF), chitosan quaternary ammonium salt (HACC), and graphene oxide (GO) in an aqueous solution. Scanning electron microscope images showed that when GO was dispersed in the composite films, the surface of CSF-based composite film became rough, and a wrinkled GO structure could be found. When the content of GO was 0.8%, the film displayed a higher change with respect to the breaking strength and elongation, respectively, up to 97.69 ± 3.69 and 79.11 ± 1.48 MPa, keeping good thermal properties because of the incorporation of GO and HACC. Furthermore, the novel CSF/HACC/GO composite film demonstrates a lower degradation rate, implying the improvement of the resistance to the enzyme solution. Especially in the film with 0.8 wt% GO, the residual mass arrived at 64.35 ± 1.1% of the primary mass after 21 days compared with the CSF/HACC film. This would reclaim the application of silk-based composite films in the biomaterial field.

1 Introduction

In recent years, some flexible composite films have allured sufficient attention due to their inherent properties comprising exceptional mechanical properties, remarkable incorruptibility [1], minimal flammability response, sufficient machinability, and suitable biodegradability [2] in the desirable biomaterial field. Silk fibroin (SF) is a naturally occurring fibrous protein synthesized from the posterior part of the silk gland. To date, SF obtained by degumming and dissolving has been devised and fabricated as films [3], scaffolds [4], hydrogels [5], microspheres, nanofibers, or non-woven mats [6] and has seen many distinctive applications. Especially SF-based composite films have been recognized as promising suitable biomaterials [7, 8], used in the skin [9], bone [10], blood vessel [11], nerve tissue, ligaments [12,13,14], and so on.

As we know, silk is divided into the domesticated bombyx mori silk [15], including mulberry silk and wild silkworm containing cassava silk [16], Antheraea pernyi silk [17], chestnut silk, and so on. Although bombyx mori silk fibroin (BSF) has been certified to be a popular replacement for conventional biomedical applications, the same cannot be said for cassava silk fibroin (CSF)-based composites, due to the limitations and lack of clarity with their morphology, thermal stability, and mechanical properties.

Earlier, the CSF membrane has been successfully fabricated by the layer-by-layer technique [18]. However, in practical applications, there are some defects about the mechanical property of SF membranes rendering them not suitable enough; also, the biodegradation rate compared with other biodegradable materials needs to be further ameliorated. Hence, the blending of CSF with other reinforcing polymeric materials to enhance the mechanical property of CSF-based composite materials [9] remains a challenge in the biomaterial field.

Recently, graphene oxide (GO) [19], one of the most excellent derivatives of graphene, has triggered remarkable attention owing to its specific structure, sufficient mechanical properties, and high exceptional surface area in several distinct applications [20, 21], including biomaterials. The two-dimensional carbon atom network of GO is composed of sp2 and sp3 connected to the oxygen-containing functional group's hybrid carbon atoms [22]. The surface of GO contains a large number of functional groups [23], such as hydroxyl and epoxy groups on the GO surface, and carboxyl groups at the edge of GO sheets. These functional groups actually endow GO with characteristic properties such as excellent hydrophilicity, suitable dispersion, and impressive biocompatibility. GO has considerable applications in electronic devices, reinforcing materials, biomaterials, and other fields, including drug delivery [22], cell affinity [24, 25], and enhancement of polymer nanomaterials due to its high specific surface area and abundant functional groups.

Moreover, some SF-based composite films [26] are prepared by the blending of the GO and BSF solution and have been studied previously [27]. Wang et al. [28] successfully prepared a flexible BSF/GO composite film using the solvent casting technique. When low concentrations of GO are incorporated into the SF solution, the characteristic properties of BSF/GO composite film including mechanical properties, thermal stability, morphology, the resistance to enzymatic degradation are obviously improved. Meanwhile, the incorporation of GO contributes to the formation of a higher content of the silk II structure in the BSF/GO composite film. When low concentrations of GO are incorporated into the CSF/chitosan quaternary ammonium salt (HACC) solution, the properties (e.g., mechanical properties, thermal stability, and morphology) of the composite film are rarely reported, especially on the induction of the molecular conformation of CSF. This, therefore, has restricted their practical utilization as composite films in the biomaterial field.

In this work, a novel CSF/GO/HACC composite membrane with low content of GO is fabricated by a simple and green solvent casting method. It should be noted that the utilization of glutaraldehyde as a cross-linking agent of CSF and a certain concentration of GO in the CSF matrix are both essential to improve the molecular conformation of CSF. In contrast to previous researches, a comprehensive evaluation of the properties of the film including the morphology, thermal stability, and mechanical properties of CSF-based composite films has been carried out, thus extending the potential applications of SF-based composite films in the biomaterials used for skin.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Raw cassava silk fibers were purchased from the Dandong border economic zone cooperation Baoli Industrial Co., Ltd. (Dandong, China). GO was purchased from Xfnano Materials Tech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Protease-XIV and glycerol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich trading Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). HACC was purchased from Nantong Lushen Bioengineering Co., Ltd. (Nantong, China).

2.2 The preparation of CSF solution

A solution of SF was fabricated as previously described [29, 30]. Briefly, raw cassava silk fibers were degummed thrice in boiling water with 0.05 wt% Na2CO3 at a bath ratio of 1:50 for 30 min, rinsed thoroughly, and dried at 60°C overnight. The extracted CSF fibers were dissolved in 9.3 mol × L−1 LiBr solution by stirring at 60°C for 1.5 h. The regenerated CSF solution was then dialyzed in a cellulose tube against deionized water for 4 days to cut off the salt debris. The resulting solutions were centrifuged at 9,000 rpm for 20 min to remove the undissolved aggregates. The final concentrations of CSF solutions were adjusted to 3.5% (w/v) with distilled water.

2.3 Preparation of the CSF/HACC/GO composite films

A suitable amount of HACC was dissolved in 2% (v/v) acetic acid solution and magnetically stirred at room temperature overnight to prepare an HACC solution at 4 wt% with acetic acid. The diluted SF solution (2 wt%), glycerol (0.3 wt%), and glutaraldehyde (0.02 wt%) were incorporated into the HACC acetic acid solution (4 wt%) with acetic acid, respectively, dropwise. An amount of 100 mg GO powder was dispersed in 50 mL of distilled water by ultrasonication for 30 min, resulting in the fabrication of a suitable GO solution (2 mg × mL−1). Then sodium hydroxide solution (1 mol × L−1) was added to the GO solution to adjust its pH value to 10. This GO solution was introduced into the CSF/HACC solution dropwise, to form a symmetrical and transparent blend solution by stirring magnetically for 40 min. The final GO contents in the composite films were 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 wt% against the weight of CSF, respectively. The composite films were poured into a glass Petri dish and kept in an oven at 40°C for 48 h. Finally, they were rinsed with distilled water for 24 h to remove the residual glycerol and dried at room temperature.

2.4 Thermal properties of CSF/HACC/GO composite films

The thermal properties of the CSF/GO/HACC films were investigated by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA). TGA curves were obtained on a TA Q600 instrument at a heating rate of 10°C × min−1under a dry nitrogen gas flow of 50 mL × min−1. DSC was performed by a thermal analysis instrument (USA). The samples were heated from 0 to 600°C at 10°C×min−1 under a nitrogen atmosphere.

2.5 Morphology and structure of CSF/HACC/GO composite films

The surface morphologies of the samples were studied with a field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM; JEOL, Japan). X-ray diffraction (XRD) curves of the CSF/GO films were studied using a Mini flex II (Rigaku, Japan) diffractometer with Cu Ka radiation.

All the samples were slit into microparticles before analysis and assessed with 2q ranging from 5° to 50°. The formation of Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra (KBr pellet) on the films was studied on a Nicolet Magna-IR 750 spectrometer in the range of 4,000–500 cm−1.

2.6 Behavior of CSF/HACC/GO composite films subjected to an enzyme reaction

The blend films were incubated at 37°C in 50 mL of PBS (the common laboratory buffer) solution with 1 U × mL−1 protease-XIV for 5, 7, and 21 days. The enzyme solution was replenished with a fresh solution daily. The degradation rate was expressed as the percentage of weight loss relative to the initial dry weight. The residual samples were rinsed in distilled water and dried at 105° at constant weight for further characterization [31]. The degradation rate was presented as the percentage of weight loss relative to the initial dry weight.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Morphology

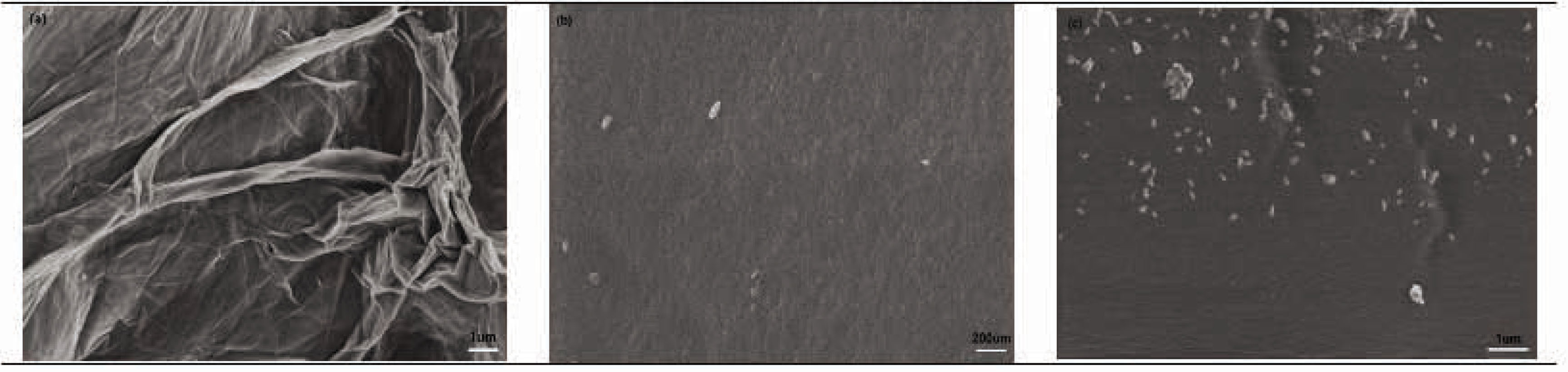

Figure 1 shows the surface and cross-sectional morphologies of three samples by SEM. Figure 1(A) exhibits a typical thin crumpled silk veil wavy morphology, while an interesting relatively smooth and flat white nanoglobular morphology is observed for the CSF/HACC film, as shown in Figure 1(B). With the incorporation of GO nanosheets, the surface of the CSF/HACC/GO composite film became rough, and a wrinkled structure of GO could be observed, as shown in Figure 1(C), indicating the optimum dispersion without aggregation and the excellent interactions between the three components in the films [28].

SEM images of the three samples: (A) surface of the GO, (B) surface of the CSF/HACC film, and (C) CSF/HACC/GO 0.8 wt% composite film.

3.2 Structural characteristics

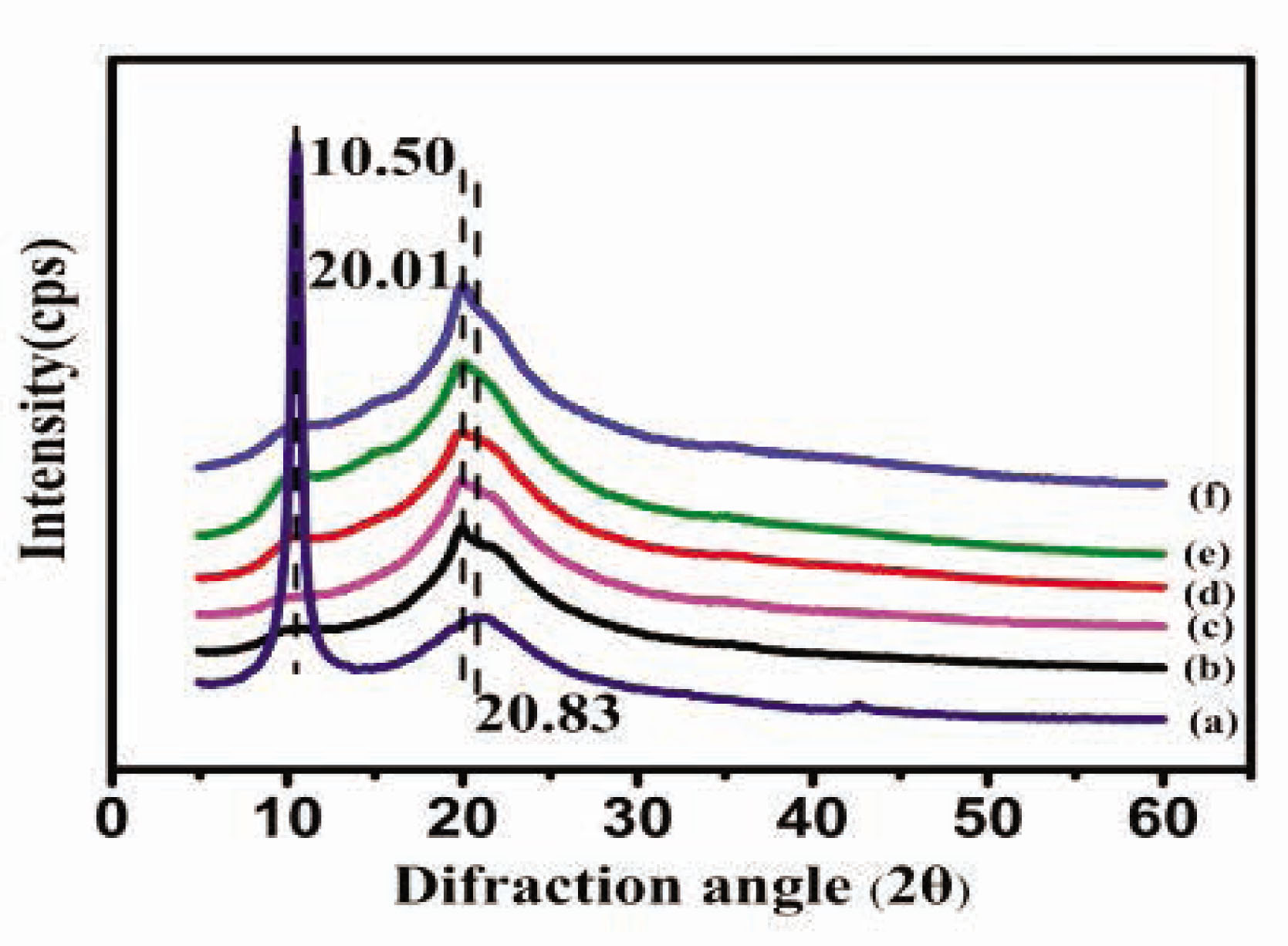

The secondary structure of the CSF/HACC/GO composite films was determined by XRD and FT-IR. Figure 2(b–f) illustrates the XRD curves of the membranes. The characteristic XRD diffraction peak of CSF appeared at 11.8° and 22.0° which could be evidence of the a-helical structure; 16.5°, 20.2°, 24. 9°, 30.90°, 34.59° were attributed to the b-sheet structure. As shown in Figure 2(a), the characteristic XRD peak of GO appeared at 2q = 10.6°, corresponding to a layer-to-layer distance (d-spacing) of 0.83 nm [32]. Both the CSF/HACC sample and the composite samples displayed prominent peaks at 20.01° (Figure 2(b–f)), indicating a typical b-sheet structure. After GO was dispersed into the blend of CSF/HACC, the diffraction peak at 20.01° [33] was gradually enhanced as the GO content increased to 0.2 and 0.8 wt% (Figure 2(c–f)). Moreover, the diffraction peak of GO at 10.50° and 20.83° [33] was discovered in the CSF/HACC/GO composite films.

XRD curves of the CSF/HACC/GO films with different GO contents: (a) GO, (b) CSF/HACC, (c) CSF/HACC/GO 0.2 wt%, (d) CSF/HACC/GO 0.4 wt%, (e) CSF/HACC/GO 0.6 wt%, and (f) CSF/HACC/GO0.8 wt%.

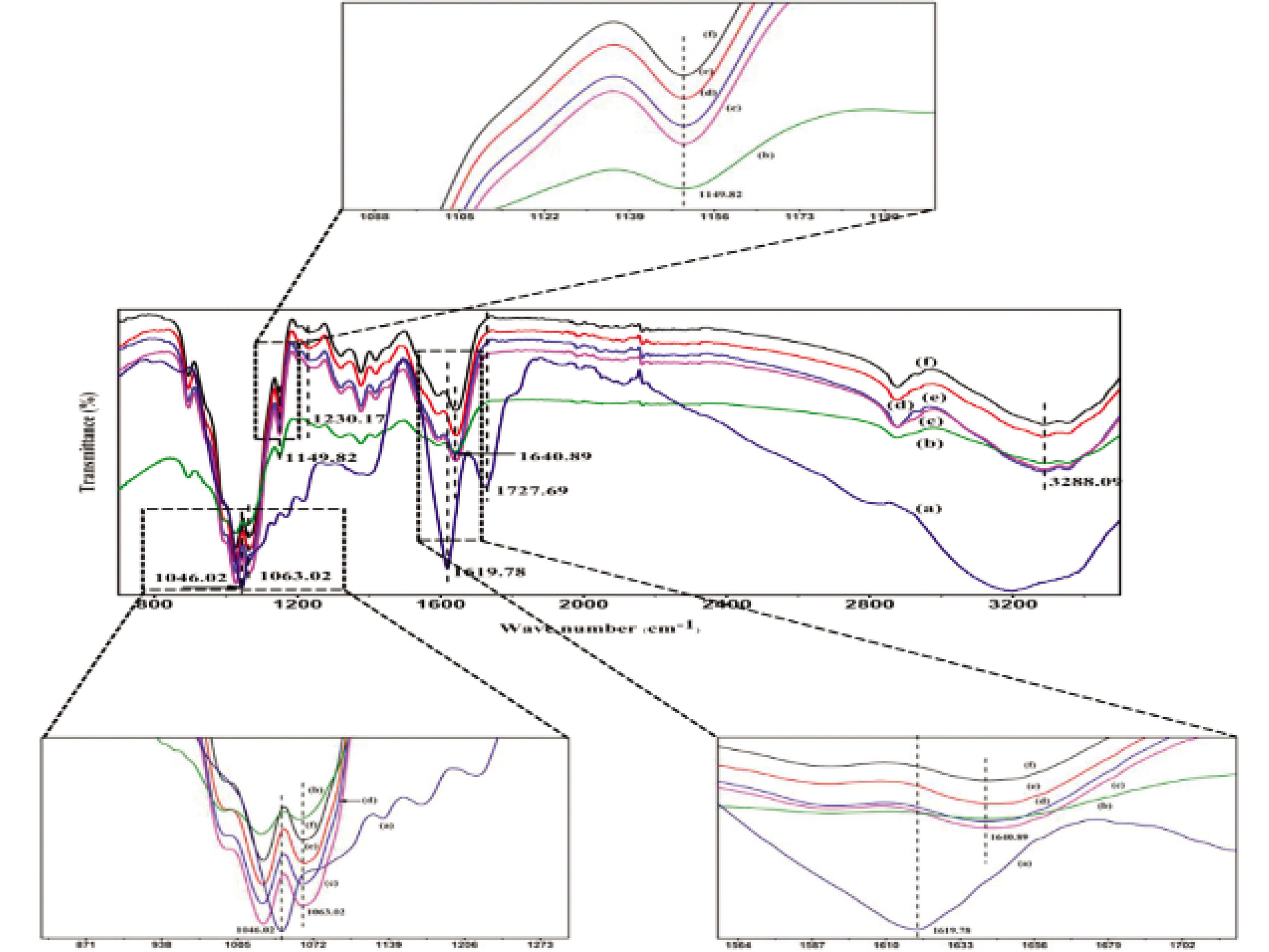

Furthermore, Figure 3 illustrates the FT-IR spectra of the membranes. The infrared spectrum of CSF exhibited absorption band values of 1,640–1,615 cm−1(amide I) attributable to the β-sheet structure, 3,291 cm−1 assigned to the random coil conformation, and N–H stretching vibration of the protein molecule. Figure 3(a) illustrates the FT-IR spectra of GO, exceptional absorption bands at 1,727.69, 1,619.78, and 1,046.02 cm−1, which were indicative of the C=O stretching vibration of the carboxylic group, C=C stretching vibration assigned to the sp2 network of the unoxidized graphite domains, and C–O–C stretching vibration of the epoxy group. Figure 3(b) shows the characteristic spectrum of the CSF/HACC composite film and excellent absorption bands at 1,640.89 cm−1was observed, demonstrating a typical β-sheet structure. Furthermore, the CSF/HACC composite film exhibited absorption bands at 1,063.02 and 1,149.82 cm−1, which could be indicative of the characteristic vibration absorption peak of–OH in HACC and the stretching vibration of C–O–C bridge. Figure 3(c–f) shows the FT-IR spectra of the CSF/HACC/GO blend film. After GO was dispersed into the blend of CSF/HACC, the peaks recorded 1,230.17 cm−1 (amide III β-sheet) a slight enhancement, implying that the molecular conformation of CSF transited from random coil/α-helix to β-sheet under the influence of GO. Meanwhile 1,063.02 cm−1 (–OH absorption vibration) and 1,149.82 cm−1 (C–O–C stretching vibration) also slightly increased. Furthermore, the typical characteristic peaks at 1,727.69 cm−1 (C=O stretching vibration), 1,619.78 cm−1 (C=C stretching vibration), and 1,046.02 cm−1 (C–O–C stretching vibration of the epoxy group) did not appear in the FT-IR spectra of CSF/HACC/GO composite films. It was likely that HACC modified the surface of GO, and the latter was evenly dispersed in the composite film.

FT-IR curves of the CSF/HACC/GO films with different GO contents: (a) GO, (b) CSF/HACC, (c) CSF/HACC/GO 0.2 wt%, (d) CSF/HACC/GO 0.4 wt%, (e) CSF/HACC/GO 0.6 wt%, and (f) CSF/HACC/GO0.8 wt%.

3.3 Thermal properties

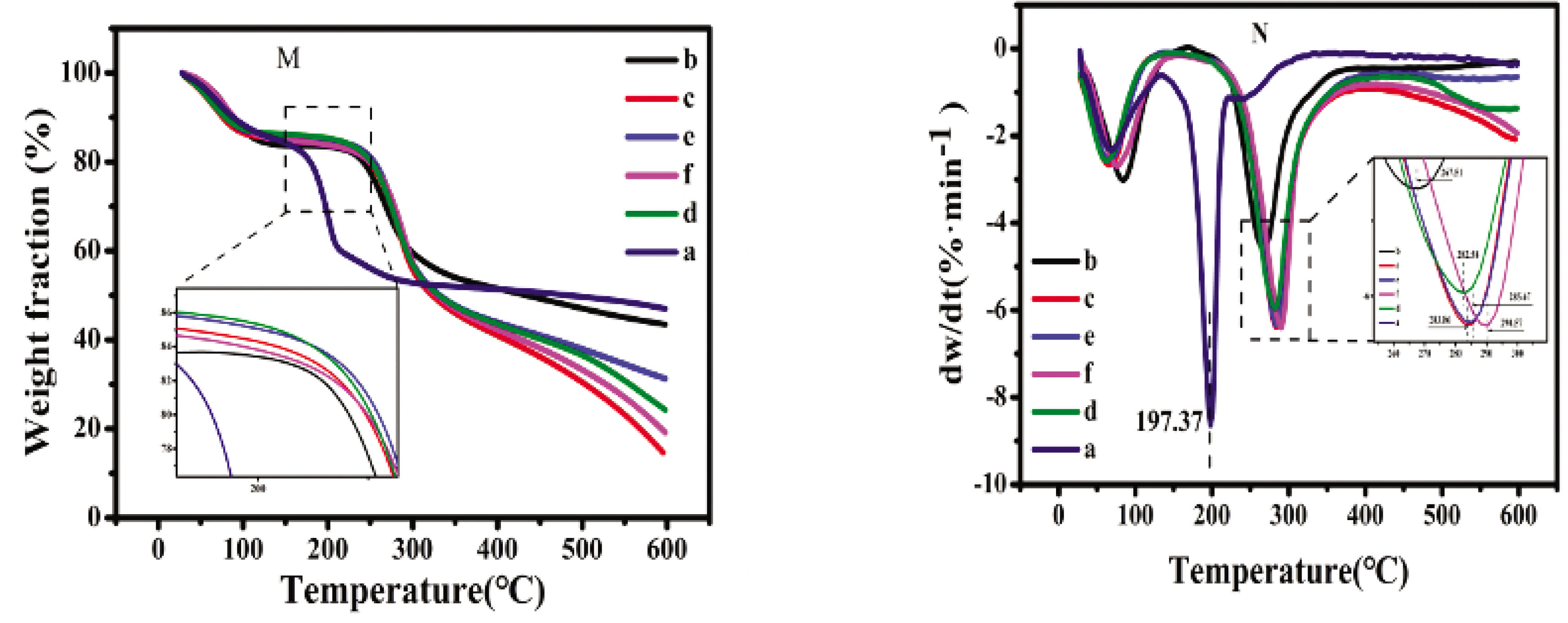

The thermal properties of the CSF/HACC/GO composite films were estimated by DSC and TGA. Figure 4 illustrates the TGA and DTG of the CSF/HACC sample and the composite samples. The TGA and DTG curves of the materials yielded three different features: the first was a weight loss which occurred at 60–100°C due to the evaporation of the bound water in the samples. Subsequently, the primary weight loss was from 190–300°C due to the thermal degradation of the volatile oxygen groups or the decomposition and melting of the amorphous zone of the internal structure of CSF with increase of temperature. The third weight loss was recorded above 300°C and this occurred due to the decomposition of more stable oxygen groups or the degradation of the crystallization portion with increasing temperature. When GO was dispersed in the composite films, both the CSF/HACC (Figure 4(b)) and the CSF/HACC/GO composite films (Figure 4(c–f)) exhibited homologous TGA and DTG curves. Figure 4(c–f) shows that the decomposition temperature improved with the increase of GO content. Especially when the content of GO was 0.8%, the degradation temperature ran up to 287.86°C, illustrating the higher thermal stability because of the strong intermolecular forces between the CSF or HACC molecular chains and the GO nanosheets compared with the CSF/HACC composite film.

(M) TG and (N) DTG curves of the SF/HACC/GO films with different GO contents: (a) GO, (b) CSF/HACC, (c) CSF/HACC/GO 0.2 wt%, (d) CSF/HACC/GO 0.4 wt%, (e) CSF/HACC/GO 0.6 wt%, and (f) CSF/HACC/GO0.8 wt%.

Furthermore, Figure 5 shows the DSC curves of the CSF/HACC sample and the composite samples. All the samples yielded an endothermic peak at around 128°C due to the evaporation of the adsorbed water molecules in the samples. The primary degradation peaks were produced in the region of 290–320°C between the CSF/HACC film (Figure 5(b)) and CSF/HACC/GO composite films (Figure 5(c–f)). With the incorporation of GO, Figure 5(c–f) shows that the decomposition temperature improved due to increase in the GO content compared with CSF/HACC composite film. When the content of GO was 0.8%, the degradation temperature reached 305.27°, implying the increase in content of the β-sheet crystal structure [34] because of the incorporation of GO.

DSC curves of the CSF/HACC/GO films with different GO contents: (a) GO, (b) CSF/HACC, (c) CSF/HACC/GO 0.2 wt%, (d) CSF/HACC/GO 0.4 wt%, (e) CSF/HACC/GO 0.6 wt%, and (f) CSF/HACC/GO0.8 wt%.

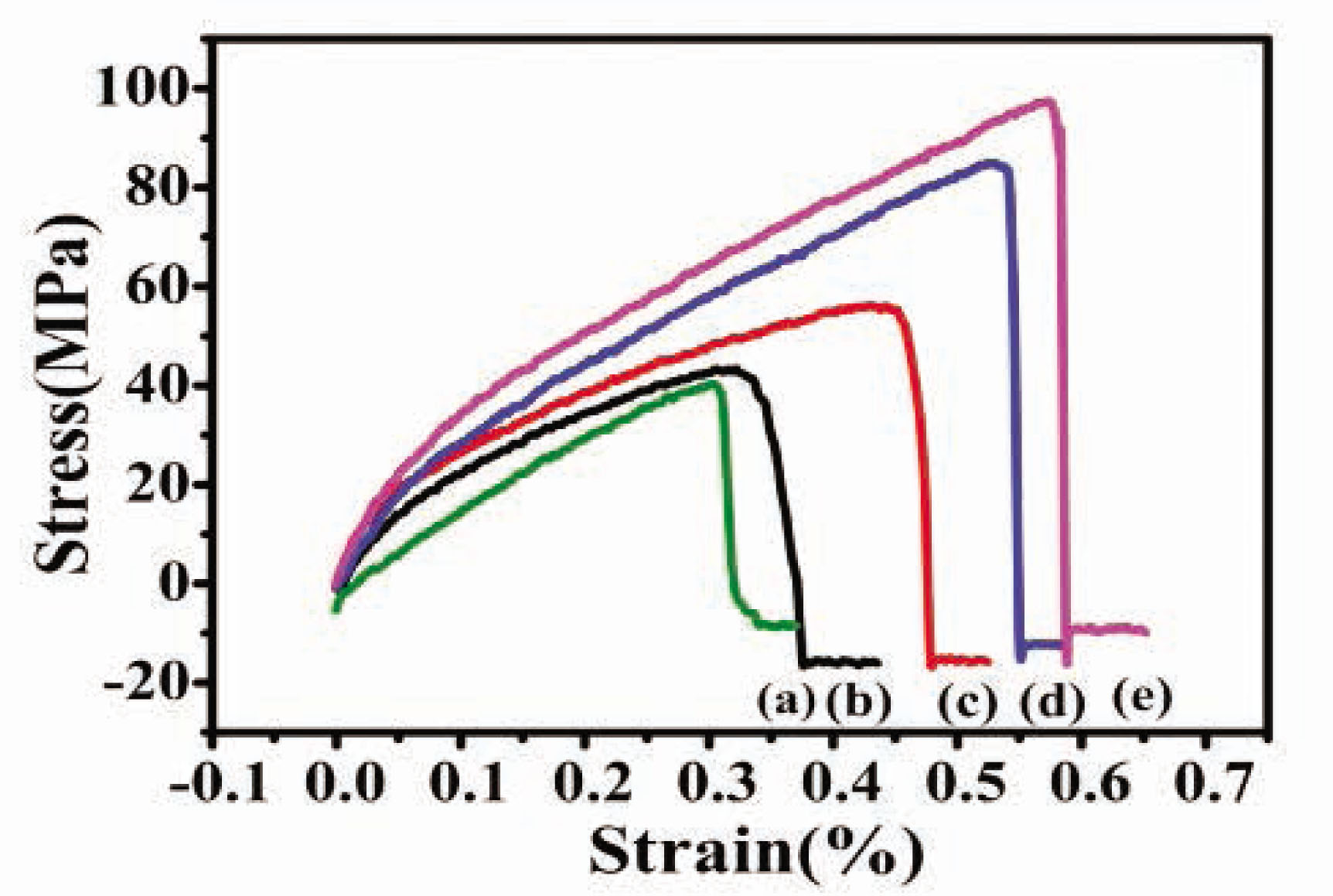

3.4 Mechanical properties

The mechanical properties of the SF-based composite film solutions were studied as previously described. GO was integrated into the CSF/HACC matrix to recompense for the mechanical properties [35], and to ensure that the fabricated CSF/HACC/GO-based biomaterial has sufficient mechanical properties as well as impressive toughness. The stress–strain curves of the SF films are shown in Figure 6, and the breaking strength and elongation at break are shown in Table 1. It could be observed that the breaking strength and elongation of the CSF/HACC film calculated were 40.24 ± 2.96 and 15.63 ± 3.27 MPa, respectively. With the increase of the amount of GO into the composite films, the breaking strength and elongation gradually improved, the value arrived at 97.69 ± 3.69 and 79.11 ± 1.48 MPa, respectively, at 0.8 wt% GO concentration. It was likely that some hydrogen bonds resulted between the CSF or HACC and GO.

Stress–strain curves of the CSF/HACC/GO films with different GO contents: (a) CSF/HACC, (b) CSF/HACC/GO 0.2 wt%, (c) CSF/HACC/GO 0.4 wt%, (d) CSF/HACC/GO 0.6 wt%, and (e) CSF/HACC/GO0.8 wt%.

The mechanical property of SF/HACC/GO composite films

| Sample | Breaking strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SF/HACC | 40.24 ± 2.96 | 15.63 ± 3.27 |

| SF/HACC/GO (0.2 wt%) | 43.74 ± 4.54 | 44.56 ± 5.73 |

| SF/HACC/GO (0.4 wt%) | 55.46 ± 7.32 | 54.35 ± 6.37 |

| SF/HACC/GO (0.6 wt%) | 85.11 ± 5.75 | 68.92 ± 2.45 |

| SF/HACC/GO (0.8 wt%) | 97.69 ± 3.69 | 79.11 ± 1.48 |

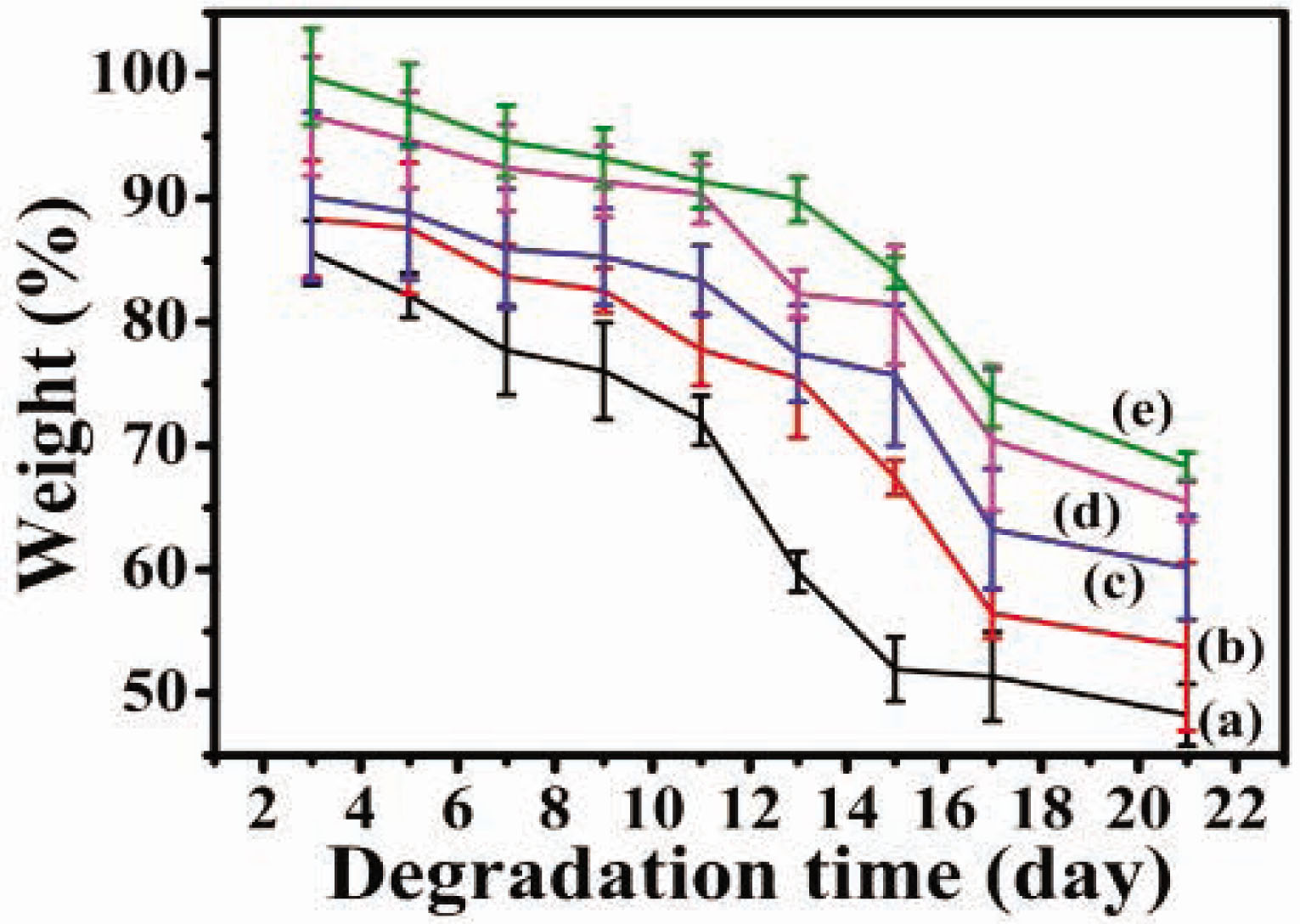

3.5 Enzymatic degradation behavior of the SF/HACC/GO blend films

The degradation behavior [36,37,38] was very significant in the biomaterial field. The degradation behavior of SF membrane was related to its secondary structure. In the degradation atmosphere of protease, the degradation rate decreased gradually with the increased content of the b-sheet structure. In this study, CSF/HACC/GO blend films were fabricated to examine the effect of the blending ratio on the degradation behavior. Figure 7 shows the weight loss of the CSF/HACC/GO blend films during a degradation trend over 21 days by protease-XIV. It was found that the CSF/HACC film rapidly degraded, and the residual mass was only 51.79 ± 2.5% of the primary mass after 21 days. When GO was added to the composite films, the weight loss of the composite films decreased gradually with time and the degradation rate was decreased with the increase of the amount of GO. Especially when the content of GO was 0.8%, the residual mass was only 64.35 ± 1.1% of the primary mass after 21 days (Figure 7(e)). The incorporation of GO probably played an important role in enhancing the increase in the amount of the b-sheet crystal structure.

Enzymatic degradation behavior of the CSF/HACC/GO films with different GO contents: (a) CSF/HACC, (b) CSF/HACC/GO 0.2 wt%, (c) CSF/HACC/GO 0.4 wt%, (d) CSF/HACC/GO 0.6 wt%, and (e) CSF/HACC/GO0.8 wt%.

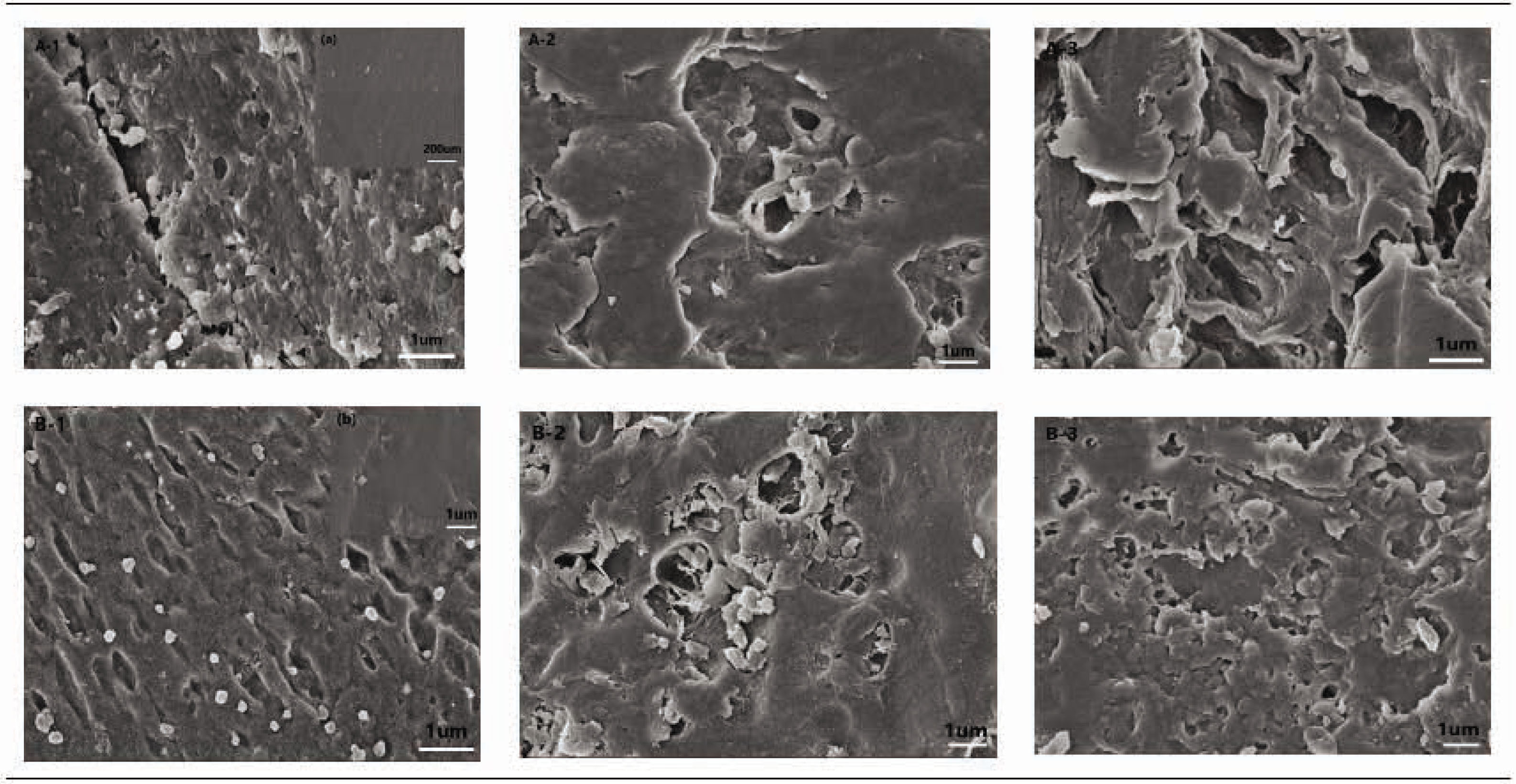

Furthermore, to exhibit the biodegradation behavior of the CSF/HACC)/GO blend films, Figure 8 illustrates the SEM images of CSF/HACC/GO films after incubation for 5, 7, and 21 days in protease-XIV solution. It was observed that the surface of the CSF/HACC film was relatively smooth except for some white particles with uniform sizes (Figure 8(a)). With incubation in enzyme solution, prominent surface erosion was found on the surface of the CSF/HACC film after 5 days of degradation (Figure 8(A-1)), and the degree of surface corrosion continued to be severe with increase in the incubation time (Figure 8(A-2 and A-3)). Also, numerous debris were found within 21 days of incubation with enzyme solution (Figure 8(A-3)) compared with the degradation time of 7 days (Figure 8(A-2)). With the incorporation of GO, the degree of surface erosion decreased with increase in the incubation time (Figure 8(B-1–B-3)), indicating the formation of more b-sheet crystal structures. It might also be that chemical crosslinking of regenerated CSF-based composite films played an important role in the biodegradability, including the degradation rate and degradation time of silk biomaterials. The CSF/HACC/GO composite membrane with 0.8 wt% GO concentration presented hole-shaped residuals both within 5 days of degradation (Figure 8(B-1)). And within 7 days (Figure 8(B-2)) or 21 days (Figure 8(B-3)) of incubation with enzyme solution (Figure 8(B-2)), the films were still able to maintain the integrity of the membrane structure. All these implied that the molecular conformation of CSF changed from random coil/a-helix to b-sheet, suggestive of the GO component importantly improving with an impressive degradability of the blend films.

SEM images of CSF/HACC/GO films after incubation for 5, 7, and 21 days in protease-XIV solution. (A-1–A-3) the CSF/HACC films were degraded for 5, 7, and 21 days in protease-XIV solution, (B-1–B-3) the CSF/HACC/GO films were degraded for 5, 7, and 21 days in protease-XIV solution. (A) SEM images of the CSF/HACC films before degradation and (B) SEM images of the CSF/HACC/GO films before degradation.

4 Conclusions

In sum, some flexible and exceptional CSF/HACC/GO composite films were fabricated by a simple and friendly technique without any harmful reagent. A higher content of β-sheet crystal structure in the blend of films was produced due to the noncovalent electrostatic interaction between groups with negative charges of GO and the groups with positive charges, and also owing to the intermolecular forces between the functional groups of GO and the polar groups on the SF molecular chains. The thermal stability and mechanical properties of the composite films gradually increased with the incorporation of certain concentrations of GO, which improved the biodegradability of silk biomaterials. This was the first time that CSF/HACC/GO-based composite films were developed. The resultant novel composite material was characterized by excellent biodegradability and has the potential for application in the field of biomaterials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science of China (11972172), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51963002), and the Open Project Program of State Key Laboratory of Bio-Fibers and Eco-Textiles, Qingdao University (2017KFKT07).

References

[1] Oun, A. A., Rhim, J. W. (2015). Preparation and characterization of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose/cotton linter cellulose nanofibril composite films. Carbohydrate Polymers, 127, 101–109.10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.03.073Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Hu, X., Cebe, P., Weiss, A. S. Omenetto, F., Kaplan, D. L. (2012). Protein-based composite materials. Materials Today, 15(5), 208–215.10.1016/S1369-7021(12)70091-3Search in Google Scholar

[3] Lu, Q., Hu, X., Wang, X. Q., Kluge, J. A., Lu, S. Z., et al. (2009). Water-insoluble silk films with silk I structure. Acta Biomaterialia, 6(4), 1380–1387.10.1016/j.actbio.2009.10.041Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Nazarov, R., Jin, H. J., Kaplan, D. L. (2004). Porous 3-d scaffolds from regenerated silk fibroin. Biomacromolecules, 5(3), 718–726.10.1021/bm034327eSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Hopkins, A. M., Laporte, L. D., Tortelli, F., Spedden, E., Saii, C., et al. (2013). Silk hydrogels as soft substrates for neural tissue engineering. Advanced Functional Materials, 23(41), 5140–5149.10.1002/adfm.201300435Search in Google Scholar

[6] Schneider, A., Wang, X. Y., Kaplan, D. L. (2009). Biofunctionalized electrospun silk mats as a topical bioactive dressing for accelerated wound healing. Acta Biomaterialia, 5(7), 2570–2578.10.1016/j.actbio.2008.12.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Meinel, L., Fajardod, R., Hofmann, S., Langer, R., Chen, J., et al. (2005). Silk implants for the healing of critical size bone defects. Bone (New York), 37(5), 688–698.10.1016/j.bone.2005.06.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Altman, G. H., Diaz, F., Jakuba, C., Calabro, T., Horan, R. L., et al. (2003). Silk-based biomaterials. Biomaterials, 24(3), 401–416.10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00353-8Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zhang, Q., Zhao, Y. H., Yan, S. Q., Yang, Y. M., Zhao, H. J., et al. (2012). Preparation of uniaxial multichannel silk fibroin scaffolds for guiding primary neurons. Acta Biomaterialia, 8(7), 2628–2638.10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Miyamoto, S., Koyanagi, R., Nakazawa, Y., Nagano, A., Abiko, Y., et al. (2013). Bombyx mori silk fibroin scaffolds for bone regeneration studied by bone differentiation experiment. Journal of Bioscience & Bioengineering, 115(5), 575–578.10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.11.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Lovett, M., Cannizzaro, C., Daheron, L., Messmer, B., Kaplan, D. L., et al. (2007). Silk fibroin microtubes for blood vessel engineering. Biomaterials, 28(35), 5271–5279.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Thurber, A. E., Omenetto, F. G., Kaplan, D. L. (2015). In vivo bioresponses to silk proteins. Biomaterials, 71, 145–157.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.08.039Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Kundu, B., Rajkhowa, R., Kundu, S. C., Wang, X. (2007). Silk fibroin biomaterials for tissue regenerations. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 65(4), 457–470.10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.043Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Li, X. F., Luo, R. C., Chen, Z. W., Li, G., Zhang, M. Z., et al. (2016). Silk fibroin scaffolds with a micro-/nano-fibrous architecture for dermal regeneration. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 4(17), 2903–2912.10.1039/C6TB00213GSearch in Google Scholar

[15] Wang, L., Lu, C. X., Li, Y. H., Wu, F., Zhao, B., et al. (2015). Green fabrication of porous silk fibroin/graphene oxide hybrid scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. RSC Advance, 5(96), doi: 10.1039.78660-78668.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Cebe, P., Partlow, B. P., Kaplan, D. L., Wurm, A., Zhuravlev, E., et al. (2015). Using flash DSC for determining the liquid state heat capacity of silk fibroin. Thermochimica Acta, 615, 8–14.10.1016/j.tca.2015.07.009Search in Google Scholar

[17] Qian, S. W., Tang, Y., Li, X., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y. Y., et al. (2013). BMP4-mediated brown fat-like changes in white adipose tissue alter glucose and energy homeostasis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(9), 798–807.10.1073/pnas.1215236110Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Hu, K., Gupta, M. K., Kulkarni, D. D., Tsukruk, V. V. (2013). Ultra-robust graphene oxide-silk fibroin nanocomposite membranes. Advanced Materials, 25(16), 2301–2307.10.1002/adma.201300179Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Ramanathan, T., Abdala, A. A., Stankocich, S., Dikin, D. A., Piner, R. D. et al. (2008). Functionalized graphene sheets for polymer nanocomposites. Nature Nanotechnology, 3(6), 327–331.10.1038/nnano.2008.96Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Yun, H., Kim, M. K., Kwak, H. W., Lee, J. K., Kim, M. H., et al. (2013). Preparation and characterization of silk sericin/glycerol/graphene oxide nanocomposite film. Fibers and Polymers, 14(12), 2111–2116.10.1007/s12221-013-2111-2Search in Google Scholar

[21] Xiao, L. Q., Liao, L. Q., Guo, X., Liu, L. J. (2013). One-pot synthesis of polyester-polyolefin copolymers by combining ring-opening polymerization and carbene polymerization. Macromolecular Chemistry & Physics, 214(21), 2500–2506.10.1002/macp.201300412Search in Google Scholar

[22] Shan, C. S., Yang, H. F., Han, D. X., Zhang, Q. X., Lvaska, A., et al. (2010). Graphene/AuNPs/chitosan nanocomposites film for glucose biosensing. Biosensors & Bioelectronics, 25(5), 1070–1074.10.1016/j.bios.2009.09.024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Abdelsayed, V., Moussa, S., Hassan, H. M. A., Aluri, H., Collinson, M. M., et al. (2010). Photothermal deoxygenation of graphite oxide with laser excitation in solution and graphene-aided increase in water temperature. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 1(19), 2804–2809.10.1021/jz1011143Search in Google Scholar

[24] Yang, H. P., Wang, L. Q., Zhao, J., Chen, Y. B., Lei, Z., et al. (2015). TGF-β-activated SMAD3/4 complex transcriptionally upregulates N-cadherin expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer, 87(3), 249–257.10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.12.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Cui, R. L., Li, J., Huang, H., Zhang, M. Y., Guo, X. H., et al. (2015). Novel carbon nanohybrids as highly efficient magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Nano Research, 8(4), 1259–1268.10.1007/s12274-014-0613-xSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Zhang, C., Zhang, Y., Shao, H., Hu, X. (2016). Hybrid silk fibers dry-spun from regenerated silk fibroin/graphene oxide aqueous solutions. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 8(5), 3349–3358.10.1021/acsami.5b11245Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Wang, Y., Ma, R., Hu, K., Kim, S., Fang, G., et al. (2016). Dramatic enhancement of graphene oxide/silk nanocomposite membranes: Increasing toughness and strength via annealing of interfacial structures. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 8(37), 24962–24973.10.1021/acsami.6b08610Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Wang, L., Lu, C. X., Zhang, B. P., Zhao, B., Wu, F., et al. (2014). Fabrication and characterization of flexible silk fibroin films reinforced with graphene oxide for biomedical applications. Royal Society of Chemistry Advances, 4(76), 40312–40320.10.1039/C4RA04529GSearch in Google Scholar

[29] You, R. C., Xu, Y. M., Liu, Y., Li, X. F., Li, M. Z., et al. (2014). Comparison of the in vitro and in vivo degradations of silk fibroin scaffolds from mulberry and nonmulberry silkworms. Biomedical Materials, 10(1), 015003–015003.10.1088/1748-6041/10/1/015003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Huang, L., Li, C., Yuan, W. J., Shi, G. Q. (2013). Strong composite films with layered structures prepared by casting silk fibroin-graphene oxide hydrogels. Nanoscale, 5(9), 3780–3786.10.1039/c3nr00196bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Li, X. F., Zhang, J., Feng, Y. F., Yan, S. Q., Zhang, Q., et al. (2018). Tuning the structure and performance of silk biomaterials by combining mulberry and non-mulberry silk fibroin. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 147, 57–63.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2017.11.013Search in Google Scholar

[32] Wang, S. D., Ma, Q., Wang, K., Ma, P. B. (2018). Strong and biocompatible three-dimensional porous silk fibroin/graphene oxide scaffold prepared by phase separation. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 111(5), 237–246.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Abdulkhani, A., Sousefi, M. D., Ashori, A., Ebrahimi, G. (2016). Preparation and characterization of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose/silk fibroin/graphene oxide nanocomposite films. Polymer Testing, 52(7), 218–224.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2016.03.020Search in Google Scholar

[34] Panda, N., Biswas, A., Sukla, L. B., Pramanik, K. (2014). Degradation mechanism and control of blended eri and tasar silk nanofiber. Applied Biochemistry & Biotechnology, 174(7), 2403–2412.10.1007/s12010-014-1151-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Lu, S. Z., Wang, X. Q., Lu, Q., Zhang, X. H., Kluge, J. A., et al. (2010). Insoluble and flexible silk films containing glycerol. Biomacromolecules, 11(1), 143–150.10.1021/bm900993nSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] You, R. C., Xu, Y. M., Liu, G. Y., Liu, Y., Li, X. F., et al. (2014). Regulating the degradation rate of silk fibroin films through changing the genipin crosslinking degree. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 109(3), 226–232.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.07.029Search in Google Scholar

[37] Zhang, W., Ahluwalia, I. P., Literman, R., Literman, D. L., Yelick, P. C., et al. (2011). Human dental pulp progenitor cell behavior on aqueous and hexafluoroisopropanol based silk scaffolds. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 97(4), 414–422.10.1002/jbm.a.33062Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Loh, Q. L., Choong, B. C., Meng, D. M., Mimmm, C. (2013). Three-dimensional scaffolds for tissue engineering applications: Role of porosity and pore size. Tissue Engineering. Part B, Reviews, 19(6), 485–502.10.1089/ten.teb.2012.0437Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Shuqiang Zhao et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- AUTEX 2022 – 21st World Textile Conference Announcement

- Design and Development of a Novel Mechanism for the Removal of False Selvedge and Minimization of its Associated Yarn Wastage in Shuttleless Looms

- Empirical Analysis of the Impact Strength of Textile Knitted Barrier Meshes

- Characteristics of Laminates for Car Seats

- Methodology of Optimum Selection of Material and Semi-Folded Products for Rotors of Open-End Spinning Machine

- Fabrication of Multifunctional Nano Gelatin/Zinc Oxide Composite Fibers

- 3D Design of Clothing in Medical Applications

- Development of Subcontractor Selection Models Using Fuzzy and AHP Methods in the Apparel Industry Supply Chain

- Evaluation of Thermal Properties of Certain Flame-Retardant Fabrics Modified with a Magnetron Sputtering Method

- Comparative Study of Long- and Short-Stretch Woven Compression Bandages

- Natural Polymers on the Global and European Market - Presentation of Research Results in the Łukasiewicz Research Network – Institute of Biopolymers and Chemical Fibers-Case Studies on the Cellulose and Chitosan Fibers

- The Fabrication of Cassava Silk Fibroin-Based Composite Film with Graphene Oxide and Chitosan Quaternary Ammonium Salt as a Biodegradable Membrane Material

- Eco-Fashion Designing to Ensure Corporate Social Responsibility within the Supply Chain in Fashion Industry

- Phototherapy in the Treatment of Diabetic Foot — A Preliminary Study

- Comparison of the Vibration Response of a Rotary Dobby with Cam-Link and Cam-Slider Modulators

- Numerical Simulation of Solar Radiation and Conjugate Heat Transfer through Cabin Seat Textile

Articles in the same Issue

- AUTEX 2022 – 21st World Textile Conference Announcement

- Design and Development of a Novel Mechanism for the Removal of False Selvedge and Minimization of its Associated Yarn Wastage in Shuttleless Looms

- Empirical Analysis of the Impact Strength of Textile Knitted Barrier Meshes

- Characteristics of Laminates for Car Seats

- Methodology of Optimum Selection of Material and Semi-Folded Products for Rotors of Open-End Spinning Machine

- Fabrication of Multifunctional Nano Gelatin/Zinc Oxide Composite Fibers

- 3D Design of Clothing in Medical Applications

- Development of Subcontractor Selection Models Using Fuzzy and AHP Methods in the Apparel Industry Supply Chain

- Evaluation of Thermal Properties of Certain Flame-Retardant Fabrics Modified with a Magnetron Sputtering Method

- Comparative Study of Long- and Short-Stretch Woven Compression Bandages

- Natural Polymers on the Global and European Market - Presentation of Research Results in the Łukasiewicz Research Network – Institute of Biopolymers and Chemical Fibers-Case Studies on the Cellulose and Chitosan Fibers

- The Fabrication of Cassava Silk Fibroin-Based Composite Film with Graphene Oxide and Chitosan Quaternary Ammonium Salt as a Biodegradable Membrane Material

- Eco-Fashion Designing to Ensure Corporate Social Responsibility within the Supply Chain in Fashion Industry

- Phototherapy in the Treatment of Diabetic Foot — A Preliminary Study

- Comparison of the Vibration Response of a Rotary Dobby with Cam-Link and Cam-Slider Modulators

- Numerical Simulation of Solar Radiation and Conjugate Heat Transfer through Cabin Seat Textile