Abstract

Revolving door dynamics are pervasive in the United States. There are vast literatures on the revolving door and on Donald Trump, but so far, no attempts to bring these literatures together. This paper represents a first attempt to do so and answer the following questions: Can Trump’s rise be understood as a culmination of revolving door dynamics, under which managers become politicians and politicians become lobbyists? What motivated Trump to revolve, and how has Trump’s presidency affected the revolving door? The paper places Trump into the context of the revolving door and compares him with previous presidents and presidential candidates. In recent decades, revolving door activity has increased. While this suggests that the revolving door paved the way for Trump, a close examination of the evidence reveals a more complex picture. Many American businesspeople have unsuccessfully run for president. Like the businessmen-turned-presidents who preceded him, Trump is a family businessman, not a manager or a CEO of a listed company. A multitude of additional factors contributed to Trump’s 2016 win including his status as a reality TV celebrity, his charisma, and his right-wing populism: Trump is from business but not from the business establishment. In addition, Trump revolved from business into politics, rather than from Capitol Hill to K Street. Candidate Trump railed against the revolving door and pledged to drain the swamp. President Trump swamped the drain and precipitated one of the most serious crises and threats to American democracy in the country’s history.

Introduction

What is the relationship between Donald J. Trump, who rose to become the 45th president of the United States of America, and the revolving door between business and politics in the US? Did the revolving door facilitate Trump’s rise and his switch from business into politics? How did Trump’s presidency affect the revolving door? This paper attempts to advance our understanding of these issues by providing an overview of different aspects relevant to Trump and the revolving door, drawing on the vast literatures on Trump and on the revolving door between business and politics in the United States. Bringing these literatures together to view Trump through the lenses of the revolving door is fruitful and worthwhile for several reasons.

While Trump’s presidency has without a doubt «been unlike anything else American democracy had experienced in recent decades, if ever,»[1] an examination of the businessman-turned-president Trump can sharpen our understanding of both Trump and the revolving door, which are linked in many ways: at his rallies across the country, Trump railed against the revolving door, and his anti-establishment rhetoric tapped into widespread anger and real systemic problems. It is possible that this rhetoric helped propel Trump—the first billionaire president and the only person without political or military experience before taking office—into the White House in 2016.

In addition, this inquiry may help us to better understand the revolving door’s implications for American capitalism[2] and democratic politics. There is widespread agreement that the phenomena described by the revolving door metaphor are problematic: politicians who revolve from public office into the private sector cash in on the knowledge and networks they have acquired, while businesspeople who revolve into politics use state regulation to further private interests rather than the public interest. While the revolving door benefits both the people who revolve and the companies who pay them, the revolving door thus has many negative effects.[3]

In addition, the role that the revolving door can play in facilitating threats to democracy is unexplored to date. Many observers agree that Trump represents a threat to democracy.[4] As one scholar writes, «[c]rises never have a single cause, but in this instance a good deal of blame can be attributed to the political campaigns and presidency of Donald Trump.»[5] Trump’s role in the 2016 election helped build an «Identity Crisis» in the United States[6] and the «fallout from the 2020 presidential election shook the nation’s confidence in the stability and viability of democracy.»[7] At the time of writing, Trump faced criminal charges for his activities in the 2016 presidential election, and it is possible that he will also face charges for his attempts to overturn his defeat in the 2020 election.

Without a doubt, «it is tremendously difficult to write about presidents in real time.»[8] There «are unique challenges that any historian faces when trying to write about the recent past,»[9] and these challenges are particularly serious for a controversial and divisive figure such as Trump. Historians are often confronted with the challenge of a dearth of sources. In Trump’s case, we face the opposite problem—he has spawned a literature so vast that it would require an army of researchers to sort through all of it. This paper attempts to provide an overview of many aspects that are relevant to a full understanding of the revolving door and Trump. It draws on insights from many disciplines in addition to history including economics, political science, psychology, and journalism, to bring these disciplines back «together again» and facilitate mutual learning.[10]

My arguments and findings are as follows. First, the revolving door is pervasive in the United States. Indeed, the revolving door seems to be the normal modus operandi in Washington, D.C. While we see an increase of revolving door activity over time, there are relatively few American businessmen turned presidents. Like the businessmen-turned-presidents who preceded him, Trump is a family businessman, not a CEO or a manager of a listed company. Most of the American presidents with backgrounds in business have been in office during the past 50 years. The parallel increase of revolving door activity and businessmen-turned presidents suggests that the revolving door paved the way for Trump. However, a closer examination of the evidence shows that Trump is an exceptional case. Many businesspeople have unsuccessfully run for president during the past decades. Why did they fail, and why did Trump—a man with deeper roots in business than any other businessman-turned-president, and the first billionaire president to date—succeed?

To answer these questions, I examine a multitude of factors that contributed to Trump’s remarkable path to the White House in 2016. These include his status as a celebrity on reality TV, his charisma, his status as a right-wing populist and even his use of Twitter. The fact that Trump is from business but not from the business establishment gave him a significant edge in 2016’s anti-establishment climate. In addition, we must examine the direction in which the revolving door swings. Trump’s charismatic anti-establishment populism and his movement from business into politics, rather than the other way around, is important for understanding his path to the White House. Candidate Trump portrayed himself as someone who would fight against or even negate the revolving door, and this portrayal likely amplified his success in 2016. Paradoxically, while money plays a huge role in American politics and a much larger role in the United States than in most other countries, anti-establishment populism rather than money is what got the billionaire Trump into the White House in 2016.

The paper is organized as follows. I begin by providing an overview of the revolving door between business and politics in the United States and examining the direction in which the revolving door swings, which is important for understanding Trump’s rise. Next, I discuss businessmen as presidents of the US and the business backgrounds of selected American presidents, including Trump himself. Trump has very deep roots in business, yet I suggest that he is an exceptional case. I develop this argument by discussing Trump’s status as an anti-establishment populist rather than a business establishment candidate. Trump’s populist credentials are essential and indispensable for understanding this rise and path to the White House in 2016. Finally, before concluding the paper, I speculate about the effects the Trump presidency has had on the revolving door dynamics in the US.

The revolving door between business and politics in the United States

Money and the revolving door have long been powerful forces in American politics. Thomas G. Corcoran revolved into the private sector after advising President Roosevelt and «exerted extraordinary influence in Washington, D.C. for nearly half a century.»[11] In «The Power Elite,» a classic of mid-20th Century American sociology, C. Wright Mills saw a perpetual revolving door between economic, political, and military elites.[12] By the mid-1980s, over 3,000 companies had representation in Washington, D.C., and more than 500 had their own offices.[13] Less than three decades later, «lobbying and campaign finance both represent[ed] billions of dollars spent annually to influence federal policymaking, primarily on behalf of business and wealthy individuals.»[14]

Due to space constraints, this paper cannot provide a comprehensive review of academic literature on the revolving door. According to the studies surveyed here, the revolving door is pervasive, indeed constitutive of American capitalism and of the relationship between business and politics in the United States. The question is not whether there is a revolving door, there clearly is:

«Although not every former public official capitalizes on his or her senior position upon retiring from civil service, the ‹revolving door› phenomenon is ubiquitous. It is not uncommon for senior officials with average salaries to resign their jobs and immediately receive a lucrative position in the private sector. In many instances, private corporations tempt incumbent public officers with rewarding jobs and induce them to resign, not necessarily because of their talent but because of their valuable connection to the public office. Those former public servants leap into the private market and suddenly receive a lucrative salary.»[15]

Economists find that «ex-government officials generate monetary rents in terms of generating lobbying revenue from their personal connections to elected representatives»[16] and managers find that «government service can serve as a conduit for joining the ranks of the corporate elite.»[17] The crucial point here is that as a result of the revolving door, US politicians benefit financially from their position after they leave office.[18] Various studies show that lobbyists with government experience earn more than lobbyists without government experience—there is a «striking difference» between conventional and revolving door lobbyists: the latter earn at least twice as much as the former.[19] The revolving door is very lucrative.

Available evidence suggests that revolving door activity has increased and intensified over time. Half a century ago, in 1970, only approximately three per cent of the members of Congress moved into lobbying; by 2017, well over half did so.[20] By 2016, lobbying was a three-billion-dollar industry. The infamous Jack Abramoff, who went to jail after being convicted on charges of fraud, corruption, and conspiracy, stated that «almost 90 per cent» of congressional staff want to work on K Street.[21] One commentator even goes so far as to say that «[t]he likely career path of a congressperson is to become a lobbyist.»[22] By 2007, there were approximately 15,000 registered lobbyists in Washington, D.C., with the actual number almost certainly significantly higher. When it comes to former members of Congress who served in the 115th Congress (which ended 2 January 2019), 26 out of 44 who left for jobs in the private sector became lobbyists in lobbying firms.[23] The laws the Supreme Court struck down during the past decade, especially «Citizens United,» opened the floodgates to money in politics in the United States.[24]

According to Offer, the revolving doors are «even more accommodating» in the United States than they are in the United Kingdom:

«Every incoming President appoints thousands of officials. Notionally non-partisan think tanks (including the august Brookings Institution) are funded by corporations, and look after donors’ interests. Secretaries of the Treasury come out of Wall Street. Financial firms pay large secret bonuses to senior staff who make a temporary sacrifice to go into government. At the Securities and Exchange Commission officials moved in and out of the firms they scrutinised, and the Chair, Mary Jo White, was accused by Elizabeth Warren, the Democratic Senator, of ‹extremely disappointing› leadership, with page after page listing cozy understandings with finance.»[25]

The American public recognize the problem: in a 2015 poll, 84 per cent of respondents said that money had too much influence; two thirds of respondents were convinced that wealthy people had more influence over elections than other Americans; and 55 per cent of respondents thought that most of the time, politicians promote the interests of those who donated to their campaign. In 2010, candidates for the House of Representatives spent one bn dollars on their election campaigns. By 2020, that had risen to almost two bn dollars.[26] Independent election related expenditures at the federal level were 143.7 mn dollars in 2008. Four years later, they were over one bn dollars. And in 2016, the total was 1.38 bn dollars.[27]

The monetary payoffs for lobbyists are substantial: Democrat Dick Gephardt, who served in the House of Representatives, billed his clients, which included Boeing, Goldman Sachs, and Visa, 6.5 mn dollars in 2010. The same year, former Republican Representative Billy Tauzin earned more than 11.5 mn dollars from his clients.[28] It should be noted, however, that the revolving door does not necessarily imply that businessmen or women are particularly successful against non-business candidates in the political arena. Adams, Lascher, and Martin find that businesspeople are not especially successful in American politics. Candidates with a background in education, for example, tend to fare better.[29]

The problematic influence of revolving-door lobbyists has been recognized for some time. Following the 2008 financial crisis, a former Wall Street insider wrote that «[w]e need to expose the corrosive if not corruptible partnership that is the revolving door between Wall Street and Washington so that the public interest is truly protected.»[30] After he was released from prison, the businessman, lobbyist, and convicted felon Jack Abramoff published a book entitled «Capitol Punishment: The Hard Truth About Washington Corruption From America’s Most Notorious Lobbyist»[31] in which he emphasized the need to totally shut the revolving door. Both Democratic as well as Republican lawmakers have undertaken at least symbolic action in response to the widely perceived need for reform.

The Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 2007 sought to address this problem, as did Executive Order 13770 under the Trump administration. To evaluate the success of these initiatives goes beyond the scope of this paper. Obama’s attempts to address this problem have been deemed a failure.[32] It may have been true, according to White House spokesman Eric Schultz, that Obama «has done more […] to close the revolving door of special interest influence than any president before him»; but as Thurber observed, Obama has found «changing the lobbying industry difficult because of its size, adaptability, and integral part [sic!] of pluralist democracy.»[33] Other analysts concur that there is little evidence that executive branch lobbying declined under Obama.[34]

This section is important for several reasons. As we will see below, Trump railed against the revolving door in the lead up to the 2016 election. At least rhetorically, Trump was responsive to the widespread public sentiment that the revolving door is a serious problem in the United States. In addition, for a full understanding of Trump and the revolving door, it is important to consider the direction in which the revolving door swings: does it revolve out of government—from politics to business? Or does it revolve from Capitol Hill to K Street or from business to politics? The door in the United States typically swings or revolves out of government, from politics to business. As we will see, the Trump presidency was different. It saw many prominent businessmen without any prior political experience—most notably Trump himself—revolve from business into government. It is possible that people viewed the prospect of people revolving from business into government more positively than politicians revolving from Capitol Hill to K Street, and that this sentiment helped Trump to win the 2016 presidential election. The next section puts Trump into context of other businessmen who have served as US presidents.

Businessmen as presidents of the United States

Despite the revolving door’s pervasiveness in the US, there is no clear, straightforward, or linear path from American business into the American presidency. To date, there have been 46 American presidents. Of these, between four and seven can be considered businessmen. According to Marchant-Shapiro,

«six presidents can be considered business executives. Harding who owned a newspaper; Hoover who owned silver mines; Truman who owned a mine, an oil company, and a haberdashery; Jimmy Carter who owned a seed-and-supply store; George H.W. Bush who owned an oil development company and was president of a drilling equipment company; and George W. Bush who owned an oil company and the Texas Rangers.»[35]

Marchant-Shapiro’s book was published before Trump was elected. Adding Trump increases the number to seven. According to Nelson’s more restrictive definition, only three American presidents are businessmen: Carter (1977–1981), G.H.W. Bush (1989–1993), and G.W. Bush (2001–2009).[36] Adding Trump (2017–2021) increases the number to four. Concerning the party affiliations of the aforementioned presidents, Truman and Carter are Democrats and all of the others are Republicans. Depending on the classification, 71 to 75 per cent of the presidents with a background in business are Republicans. But irrespective of party affiliation, they are all family businessmen.

Businessmen turned presidents are relatively rare: depending on the coding, only an estimated eight to 15 per cent of American presidents are businessmen. Furthermore, despite President Coolidge’s observation that «[t]he business of America is business,» no major corporate CEO has ever ascended to the presidency.[37] Looking at developments over time, the number of businessmen turned presidents has increased significantly in recent decades. What happened? As Geismer points out,

«[t]hroughout much of American history, business figures largely avoided national elected office, relying instead on their wealth to influence elections and governance from the outside. Although many figures appreciated their close access to politicians, it took a particular type of business mogul to run as a candidate. Beginning with the independent candidacy of Ross Perot in 1992, many CEOs have done just that.»[38]

George W. Bush (2000–2008) is the first American president to hold a master’s degree in business administration (an MBA), and Bush has been described as «the very model of a modern MBA president»[39] as well as «the biggest signal of the rise of the so-called CEO President.»[40] The question arises whether this dynamic paved the way for Trump’s rise.

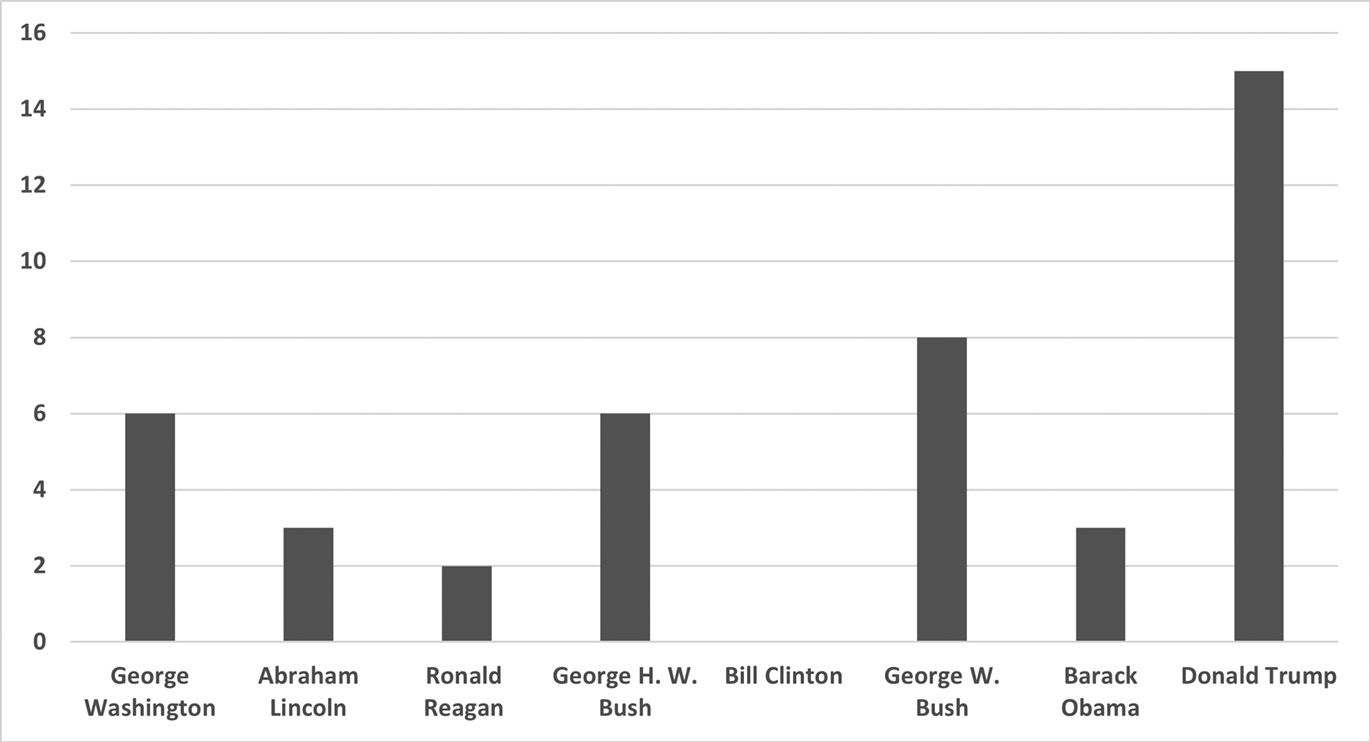

In addition, it would be helpful to know more about the backgrounds of American businessmen turned presidents. How do they vary? Can we detect different gradations—do some American presidents have a deeper grounding in the world of business than others? Figure 1 is based on George and Rodger’s attempt to quantify the qualifications of selected American presidents, including their backgrounds in business.[41] They assign points for people’s qualifications in the realm of business, which include their status as an entrepreneur, manager, private sector CEO, etc. A score of zero indicates that the candidate has no business-related experience or qualifications. The higher the score, the greater their grounding in the world of business.[42]

Business backgrounds of selected American presidents

Source: coding based on James A. George/James A. Rodger, How to Select an American President: Improving the Process by Promoting Higher Standards, Bloomington 2017.

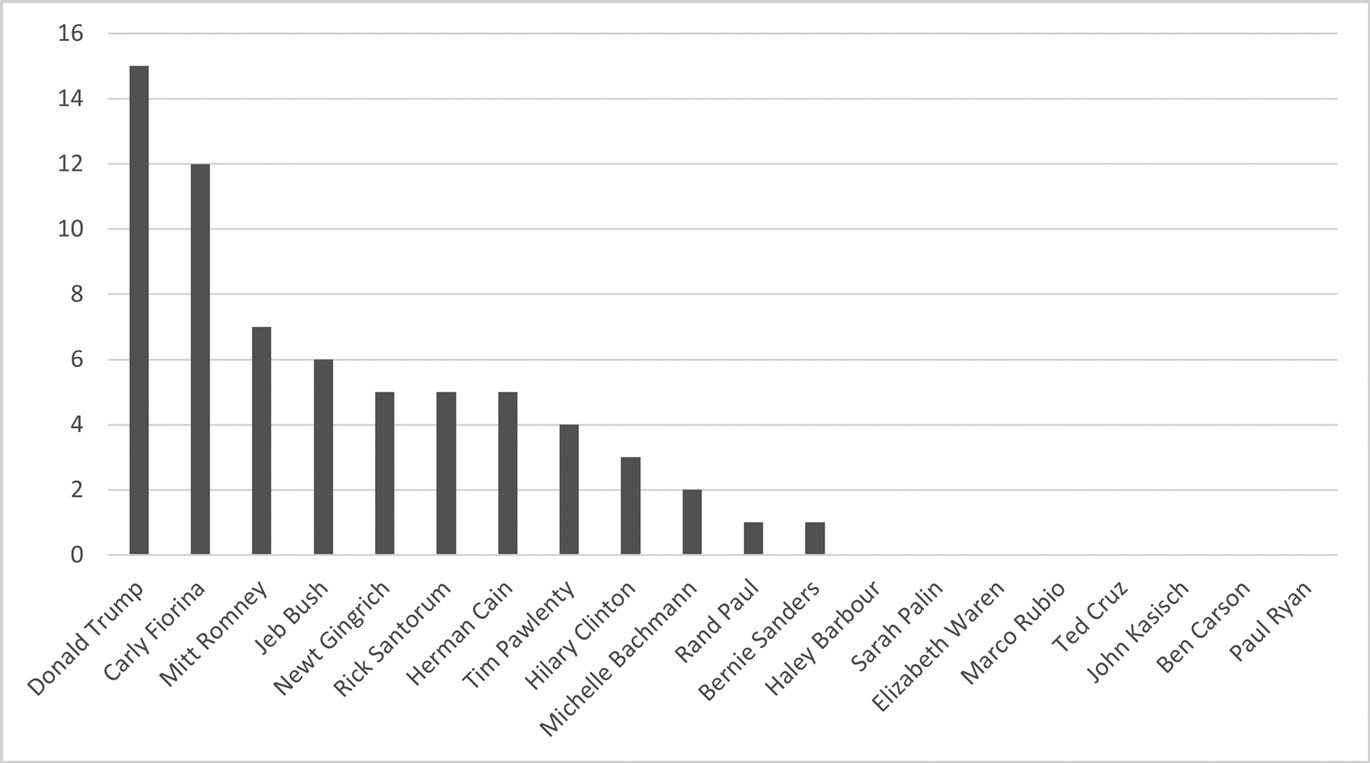

Figure 1 does not include all the aforementioned American businessmen-turned-presidents. However, the fact that Trump’s score is almost twice as high as George W. Bush’s suggests that Trump has deeper roots in business than any other American president to date. Figure 2 compares the business backgrounds of Trump with other people who ran for president in 2016. Here, we see that Trump has a higher score than former Hewlett-Packard CEO Carly Fiorina and Bain Capital co-founder and CEO Mitt Romney. Why did Trump revolve successfully into the presidency in 2016 while businessman Mitt Romney lost against Barack Obama in 2012? In the 2012 election, Mitt Romney was valorized for his business background:[43]

«Romney chose to revive Calvin Coolidge’s (1925) old aphorism, ‹The chief business of America is business.› It wasn’t a good fit. As Theodore H. White […] observed about Mitt Romneys businessman father, George, in 1968: ‹Romney, like most businessmen who come to politics, has been trained to think in product, sales, and measurement. Politics, however, is a business of no executive substance whatsoever, for its ingredients are dreams and images, words and fears, insubstantial products difficult of measurement.› White’s decades-old observation had a special resonance in 2012.»[44]

Business backgrounds of 20 presidential candidates in 2016

Source: coding based on James A. George/James A. Rodger, How to Select an American President: Improving the Process by Promoting Higher Standards, Bloomington 2017.

Romney was lacking in popular appeal and charisma; he was perceived as part of the hated big business and financial establishment, which was a particular liability following the 2008 financial crisis. Romney’s defeat in 2012 was «a crushing blow to the establishment,»[45] which contributed to Trump’s win in 2016.

A glance at some of the other candidates in Figure 2 hints at Trump’s appeal: Carly Fiorina served as the first female CEO of one of the largest listed companies, but she was criticized for laying off tens of thousands of employees and offshoring jobs. In a somewhat similar vein, Jeb Bush was criticized for his connections to Wall Street banks. Romney, Fiorina, and Bush were criticized for their connections with the business establishment and elite at a time when the political winds had shifted sharply in an anti-establishment direction. At any rate, structural factors including the level of revolving door activity in the United States are insufficient for explaining Trump’s success. Put differently, Trump’s win in 2016 should not be understood as the culmination or the logical conclusion of increasing revolving door activity up until that point. In the remainder of this paper, we will explore what gave Trump his edge.

The extraordinary Donald Trump: not your typical businessman or politician

It is impossible to say with any certainty what circumstances and personal characteristics enabled Trump to win the presidency in 2016.[46] But it seems clear that Trump’s charisma, his skills as a showman, and his status as a celebrity turned reality TV star turned right-wing populist rather than his business reputation among leading experts helped put him over the top.[47] Concerning Trump’s business acumen, it has been said, «[t]he people who know the least about business admire him the most, and those who know the most about business admire him the least.»[48] Be that as it may, Trump is unquestionably famous, as D’Antonio pointed out in 2015:

«In one way or another, Donald Trump has been a topic of conversation in America for almost forty years. No one in the world of business—not Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, or Warren Buffett—has been as famous as Trump for so long. First associated with high-profile real estate development in 1970s Manhattan, his name soon became synonymous with success defined by wealth and luxury […]. Trump’s views and bully persona made him exceedingly popular with people who believed he represented important ideals, especially the American promise of success represented by great wealth.»[49]

Trump has an unusual personality. One psychologist claims that «Donald Trump is one of the most extroverted human beings to ever walk the earth.»[50] While a full investigation of the origins of Trump’s persona would take us too far astray, it is important to at least briefly mention his family background and their business activities. Donald Trump’s father Fred Trump was a well-known, wealthy, and authoritarian real estate developer who was «known for the harsh treatment of his children.»[51] Donald Trump’s niece Mary Trump characterizes Donald Trump’s father Fred Trump as an «iron-fisted autocrat» who laid out the following rules at home: «be tough at all costs, lying is okay, admitting you’re wrong or apologizing is weakness.»[52] Fred Trump was a «very tough» guy who was «ruthless in his business dealings,» «discouraged emotional expression,» and «urged his children to be fiercely competitive.»[53] Fred Trump reportedly told his son Donald that he had to «be a ‹killer› in everything he did.»[54]

Donald Trump’s aggressive, adversarial style contributed to his anti-establishment populist image, and as I discuss in greater detail below, this probably helped him to win the presidency in 2016. Trump had already used these tactics to cultivate a very particular reputation and brand in real estate. Public subsidies and connections and relationships with city and state planners and zoning officials are generally important in real estate, and they were or are central to the Trump family’s real estate business.[55] But hard bargaining and aggressive tactics also helped build Trump’s reputation. In 1973, the Justice Department sued the Trumps, alleging that they had engaged in racial discrimination in their housing projects. Donald Trump hired the lawyer Roy Cohn, who «advised Trump to fight the claim by filing a $100 million countersuit against the government,» which led to a more favorable outcome for the Trumps.

This taught Trump an essential lesson that he would use throughout his business and political career—«when attacked, counterattack with overwhelming force»[56]—and it helped build Trump’s band and his mythical anti-establishment populist reputation. As we will see below, it is easy to see how Trump’s relational philosophy, «[w]hen a person screws you, screw them back fifteen times harder»[57] could resonate with people who feel left behind or unfairly taken advantage of. While many of Trump’s business endeavors such as «Trump Airlines» and «Trump University» ended in failure, scandal, and bankruptcy,[58] this hardly dented Trump’s image and brand reputation as a fighter in the eyes of his supporters.

It is common for presidential candidates in the United States to publish a book or even two during election season. Trump is listed as the author or co-author of at least two dozen books. These titles include: «Trump: Think Like a Billionaire: Everything You Need to Know About Success, Real Estate, and Life,» «Time to Get Tough: Make America #1 Again!,» «Think Like a Champion: An Informal Education in Business and Life,» «The America we deserve,» «Midas Touch: Why Some Entrepreneurs Get Rich--and why Most Don’t,» «Why We Want You to Be Rich,» «Trump: The Art of the Comeback,» and «The Trump Doctrine: Inside the Complex Mind of a Business Genius.»

Trump’s most famous book, «The Art of the Deal,» written by Tony Schwartz, reportedly sold over one mn copies, and contributed significantly to Trump’s fame. In this book, Trump asserts: «[T]he final key to the way I promote is bravado. I play to people’s fantasies. People may not always think big themselves, but they can still get very excited by those who do. That’s why a little hyperbole never hurts. People want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular.»[59] Trump’s showman and media personality on television, especially in the reality TV series «The Apprentice» made him appear larger than life:

«Through The Apprentice, Trump built a personal brand any outsider politician would envy: decisive, averse to bullshit, impossible to swindle, and guided in all decisions by brash, plainspoken common sense […]. Although most politicians fiercely compete for precious media time and work with diligence to form a likable yet authoritative impression on the American voters—often with discouraging outcomes—Donald Trump had 14 seasons of carefully edited prime time exposure to imprint a presidential impression on American minds. Our data suggest that he was successful in doing so and that it played an important role in his election. The more participants in our study were exposed to Trump, both through his TV shows and other media, the more likely they were to have a parasocial bond with Trump […]. Trump’s election was seriously influenced by his appearance on reality TV. Indeed, given that this was such a close election, it is possible that Trump would not have won without the benefit of his years on The Apprentice.»[60]

Other sources confirm that «The Apprentice» helped Trump to learn «methods of holding an audience’s attention and playing up his own persona that would serve him well when he turned his full attention to politics.»[61] Conrad Riggs, who helped develop «The Apprentice» together with TV producer Mark Burnett, recalls: «We thought, who is super charismatic, and you either love him or hate him but you’re going to watch him either way?—and that’s Donald Trump.»[62] According to another scholar, «The Apprentice» featured «a familiar mix of competition and ruthlessness» and prefigured key aspects of Trump’s campaign and presidency including «politics as theater, the power of humiliation, the appeal of plain speaking and directness, the ascendency of individualism in the face of supposedly failed government social programs, and the often-brutal and always-dramatic triumph of winners over losers.»[63]

In the context of the revolving door, Trump «didn’t want to just be a businessman. He wanted to be a star, and television was a way to be a star. He created a brand that was more based on hype than anything else.»[64] Both as a candidate and as a president, Trump approximated Weber’s ideal-typical picture of how charisma works «remarkably closely.»[65] As Trump’s former campaign manager and right-wing populist strategist Steve Bannon points out, «He’s got an ability to viscerally connect into people’s guts and hearts.»[66] Many of Trump’s five central principles, «Principle #1: Fill a need; Principle #2: Bend the rules; Principle #3: Put on a show; Principle #4: Exert maximal pressure; Principle #5: Always win,»[67] are widespread in the world of business. «Put on a show» is more unusual in business, but crucial for understanding Trump.

It is essential to understand that Trump won in 2016 not because he represented the American business establishment, but precisely because he portrayed himself as an anti-establishment populist who challenges political and cultural elites. What Trump achieved is remarkable: «never before had a candidate been so successful in the race to the White House with as little support from elites as Trump had.»[68] To some extent, this antiestablishment orientation continued when Trump was in office, as Conley points out:

«Trump is doing exactly the job they asked him to undertake: upsetting the apple cart of the entrenched elite, lambasting a putatively dishonest media, and taking aim at a supposedly self-interested permanent political class that manipulates institutional rules to the detriment of the forgotten voter.»[69]

As we can see in the survey results below, Trump benefitted from the perception that he was a successful businessman who was populist and nonconformist.

Survey respondents’ positive comments about Donald Trump

|

Successful businessman |

24.2 |

|

Protects and preserves United States |

24.2 |

|

Great personal energy |

16.0 |

|

Nonconformist politician |

10.4 |

|

Populist platform |

8.8 |

|

Refreshingly candid |

8.7 |

|

Not Hillary Clinton |

5.1 |

|

Traditional Republican values |

2.5 |

Source: Roderick P. Hart, Trump and Us: What He Says and Why People Listen, New York 2020, 184.

In the next section, I explore key elements of «The Trump Brand of Right-Wing Populism,»[70] which is essential for understanding Trump’s distinctive allure, appeal, and success.

The Trump brand of right-wing populism

Populism is grounded in the antagonism between the true, virtuous people on one hand and the corrupt elite, traitorous enemies, unpatriotic minorities etc. on the other hand. Although many of Trump’s economic policies were conventional Republican, he was nevertheless a cultural populist[71] and an economic nationalist[72] who gave his audience villains to hate. In addition to immigrants and racial minorities[73] as well as China and other nations cheating American workers with unfair trade practices, the scapegoats were political and business elites «who rigged the system in [sic!] their benefit» and «are supporting Hillary Clinton because they know as long as she is in charge nothing will ever change.»[74] Trump claimed that «[h]edge fund managers, the financial lobbyists, the Wall Street investors were throwing their money at Hillary Clinton» as a means of the «powerful protecting the powerful.»[75] Trump’s claim at the Republican national convention in 2016 that his proposals will be «opposed by some of our nation’s most powerful special interests»[76] is straight out of the populist playbook.

While «the reverence for corporate wealth and power […] fueled the success of the television program ‹The Apprentice›,»[77] Trump’s anti-system and anti-establishment orientation and his embrace of America first, anti-globalist themes[78] gave him an important edge over Hillary Clinton. Trump’s message found wide appeal, not only on the right of the political spectrum but elsewhere too, based on the widespread sentiment and reality that the American social compromise is broken. I am suggesting that accounts of Trump and the revolving door must consider his status as an anti-establishment populist who rose to power (at least in part) by railing against the revolving door. Put differently, Trump’s expressed opposition to the revolving door in the run up to the 2016 election may well have helped him to revolve into the American presidency.

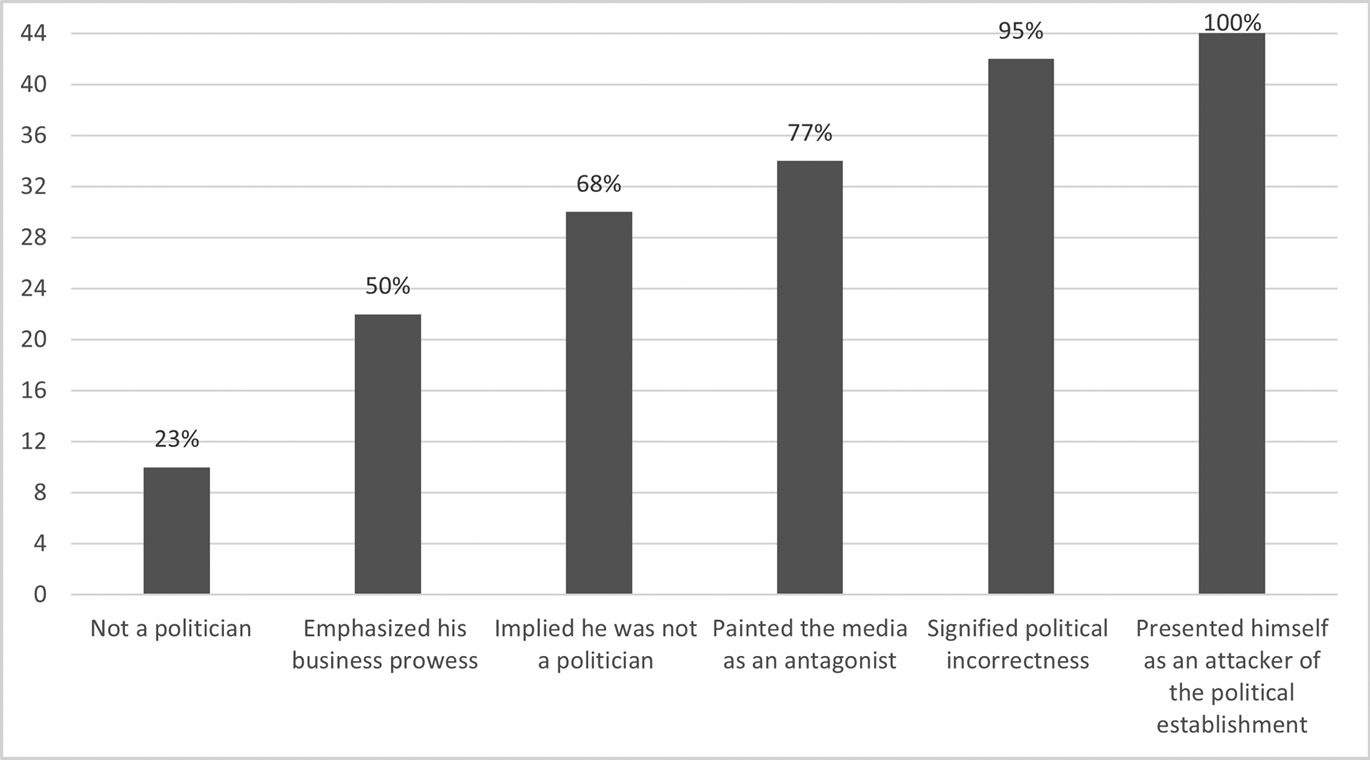

In Trump’s announcement speech, he said: «[p]oliticians are all talk, no action.» Trump «depicted himself as a tough guy who would tell corporate leaders they could not move factories abroad.»[79] He stated: «the American dream was dead and presented himself as the solution because he was an ultra-rich tough guy beholden to no one […].» The celebrity outsider aspect of Trump’s persona provided supporters a hero they perceived to be like them and not of the system. Trump is an «entrepreneur of identity,» and many of his supporters saw him as a «regular guy» and «one of their own.»[80] Figure 3, based on an analysis of 44 of Trump’s rallies in 2016, shows how prominent Trump’s anti-establishment orientation was on the campaign trail.

Major themes in 44 of Donald Trump’s campaign rallies

Source: figure based on Douglas Schrock et al., Trumping the Establishment: Anti-Establishment Theatrics and Resonance in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election, in: Race, Gender & Class 3/4 (2018), 7–26.

The Trump brand of right-wing populism flourished at a time when CEO pay had soared, worker wages and living standards had stagnated, and the life expectancy of working-class whites had declined. There was and is widespread agreement that the political-economic status quo is broken. Trump and Sanders were the only two candidates who made this their central focus in 2016, and it is easy to see how Trump’s message «Make America Great Again,» a slogan which Ronald Reagan had also used in 1980,[81] resonated in this environment. Sanders’ candidacy was opposed by the Democratic establishment, which meant that Trump:

«was the only insurgent candidate, with only weak ties to the Republican Party, while the other candidates were firmly within the establishment. For Republican voters who had tired of the Republican establishment and no longer trusted it, Trump was the only candidate […]. Trump was a populist: he was a critic of the established order, and an outsider who attacked the established party leadership.»[82]

«Trump argued that he was the only candidate to clean up government because his opponents were controlled by lobbyists, controlled by their donors, controlled by special interests. Lobbyists, he often said or implied, were part of Washington’s ‹culture of corruption.›»[83] Trump pledged to take decisive action by stating: «it’s time to drain the swamp of corruption in Washington, DC, and we’re going to do it […], we will drain the swamp in Washington, DC and replace it with a new government of, by, and for the people.»[84] It is important to note that «drain the swamp» is not a narrow partisan message of the populist right. In 2006, Democratic senator Nancy Pelosi promised that if she took power, she would «drain the swamp» and put in new rules «to break the link between lobbying and legislation.»[85]

By opposing free trade and pledging to «drain the swamp,» and by making statements such as that «[h]edge fund guys are getting away with murder», Trump appealed to the widespread anti-globalization sentiment and resentment against coastal elites: «Many believe that globalisation has empowered states and their elites, through the rise of global finance, for instance, with the ‹revolving door› between financial centres such as Wall Street in New York and the nearby seat of power on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. providing an important case in point.»[86] In so doing, Trump appealed to Americans who felt that the system was stacked against them, and managed to gain the support of some Democrats: «Even some of the staunchest local Democrats—those who disliked Trump most—appreciate Trump’s national economic protectionism precisely because they are already local protectionists.»[87] Trump was a marked contrast to previous American businessmen who tried to revolve from business into the White House: not only Mitt Romney, even Ross Perot was more technocratic, in other words less populist than Trump.[88]

Trump’s political style is that of a radical right-wing populist, not a typical businessman. One scholar describes it as an «adversarial style» which is characterized by «unrelenting aggression.» Trump has learned «never to apologize, back down, or admit wrongdoing, always be on the offensive, to bluster and smear opponents, and be as brutal and dishonest as necessary. Win at all costs.»[89] He can «level a personal attack with savageness.»[90] He claimed that Obama was not born in the United States, that Mexico was sending rapists to the US. Trump has not only «spent a lifetime hawking a manufactured reality to the American public,»[91] as Shannon Bow argues, Donald Trump’s rhetorical style has been heavily influenced by professional wrestling.

His close association with wrestling since the 80s means this media form is where he «cut his teeth» as a public persona. Wrestling has many aspects that Donald Trump trades on within the public sphere. Verbal aggression, name-calling, refusing to admit fault, never apologizing, and always doubling down are all stock and trade of wrestling. Trump «has turned the public forum into a pseudo wrestling stage. Donald Trump describes news he personally does not like, regardless of accuracy, as ‹fake news›.»[92] Trump said: «the Establishment is trying to take it all away from us, folks. They’re trying so hard.»[93] He has repetitively referred to the media as the enemy of the people. «By launching such radical moves against his political foes, Trump stylizes himself into a representative of ‹an insurgency movement on behalf of ordinary Americans disgusted with the corrupt establishment, incompetent politicians, […] and politically correct liberals›.»[94]

Trump was and is strongly pro-business. Kevin Plank, CEO of the sportswear company Under Armour, opined about Donald Trump that «to have such a pro-business President is something that is a real asset for the country […], he wants to build things. He wants to make bold decisions and be really decisive.»[95] But Trump is also anti-business establishment in orientation. A book published in 2000 entitled «Memos to the President: Management Advice from the Nation’s Top CEOs»[96] epitomizes the neo-liberal view which Trump at least to some extent negated: America should be run by a business, and politicians should get their advice from experts in business. «Trump’s reputation as a passionate, hard-boiled businessman first benefited his campaign,»[97] but his positions regarding immigration, free trade, etc. deviated strongly from the ones the business establishment has advocated for some time. Trump was not a neo-liberal CEO president in any narrow straightforward sense.

As is typical of right-wing populists, Trump’s base of business support has been especially strong with small businesses. This should not be surprising, given that Trump is not «‹corporate›—in the sense of having experience of layers of accountability. His personal history, business experience and the strategies he has consistently employed are those of an entrepreneur and a family-business CEO.»[98] Trump was not Wall Street’s favored candidate—Clinton was, and Clinton received far more campaign donations than Trump did, which strengthened the latter’s populist credentials. In early 2016, when the Republican field was still crowded, nearly 60 per cent of owners of small business supported Trump, and most of his campaign contributions have come from small business owners, not the Wall Street elite that supported Clinton. «Trump’s message and platform is the expression of the interests of small businesses […]. Many small business owners see Trump as one of their own.»[99]

President Trump’s tax policies were highly regressive, benefitting the rich much more than working class people; but in trade policy, Trump held true to his anti-establishment populist rhetoric. As a candidate, Trump made his opposition to free trade very clear, which led him to clash with the US Chamber of Commerce. As Creswell points out, it is «highly unusual» for a Republican presidential candidate to fight with the country’s most powerful business lobby organization:

«For the chamber, the bastion of free enterprise and free trade whose roots date back more than 100 years, Mr. Trump’s willingness to upend trade agreements, to tax goods from important countries and even invite a trade war is tantamount to rolling tanks up to its doors. The acrimonious relationship between the chamber and the presumptive Republican nominee is highly unusual: Historically, the two have been as close as peanut butter and jelly.»[100]

President Trump pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, and he threatened to scrap the North American Free Trade Agreement—in the end, it was renegotiated as the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement.

What motivated Trump to revolve into politics? He has expressed his desire to run for the presidency for several decades, and key elements of his personality (described above) probably explain much of this motivation. However, finances may also have played a role. Trump reportedly received over 200 mn dollars for his role in «The Apprentice,»[101] which shows that «[h]e has succeeded, like no one else, in converting celebrity into profit.»[102] However, viewership was trending downward over time, and the six bankruptcies during his career suggest that he may have also had financial motivations. Recently released information from Trump’s tax returns shows that he lost money and paid very little in tax in the run up to the 2016 election,[103] so this possibility cannot be ruled out. Sam Nunberg, who advised Trump in 2016, suggests that the actions taken by media companies following Trump’s derogatory remarks in 2015 may have motivated Trump to go all the way:

«He announces. The next week he is dropped by everyone. It helped us politically, but it was killing his business. He lost a lot of money. Part of it too was he didn’t know where this was going to go. He got pushed into wanting to go the whole distance after they fucked him after his announcement speech, especially when he got The Apprentice taken away […]. The irony was, whenever they hurt his business it was going to help him politically to become a martyr.»[104]

If Trump did subsequently «Turn the Presidency into a Business» while in office, as one book has suggested,[105] this is entirely consistent with the underlying logic and the normal dynamics of the revolving door.

The impact and effects of the Trump presidency on the revolving door in the US

How has Donald Trump’s presidency affected the dynamics of the revolving door in the United States? At the time of writing, it may be too early to answer this question since the process of revolving from government into the private sector takes time. This section nevertheless tries to answer this question by drawing on interviews as well as secondary literature. In short, the available evidence does not suggest that revolving door activity declined under the Trump administration. While this can be seen as a betrayal of Trump’s promise to drain the swamp, the door revolved in a different direction, and the Trump administration did disrupt some business as usual.

This section begins with Max Moran and Timi Iwayemi, who both work for the Revolving Door project—an organization that scrutinizes the revolving door and seeks to advance the public interest. Moran and Iwayemi confirm that the revolving door has been a feature of American politics «for a very long time.» They state that under Reagan, you start to see more revolving door dynamics. The revolving door was important under administrations of George W. Bush as well as Obama.

However, they state that there are «orders of magnitude. It was more open and brazen under Trump. At the cabinet level, we had Rex Tillerson, Wilbur Ross, Andrew Wheeler, Elaine Chow, Alex Azar, and Betsy DeVos.» And «[t]hose are just at the highest cabinet level.» Also, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. And the head of the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) was a coal industry lobbyist. There was also a difference in that unlike in the past, «under Trump, there was a total lack of pretense that this is about serving the public interest or improving the lives of people» as the expertise of these people was «in weakening their entire agencies.» Wheeler, for example, «rolled back many environmental rules.» «When it comes to revolving in,» Moran and Iwayemi maintain that «there is no comparison. This is the most revolving in we’ve seen so far, it’s a level of its own in comparison to previous administrations.»[106]

«Trump is a good salesman,» Iwayemi notes: «[y]ou avoid mentioning certain things. You mention draining the swamp, but you don’t say how. The substance of this proposal was very meager.» Moran agrees that this was a slogan rather than a concrete policy. «What is being done to drain the swamp? The swamp are those liberals.» It is too early to know whether the unprecedented polarization of the United States and the bad reputation of each tribe or camp (of Republicans with Democrats, of Democrats with Republicans) will make it harder for ex-cabinet and ex-government officials from the Trump administration to revolve out into lucrative jobs in the private sector. Moran and Iwayemi suggest that there is a «fascist to opportunity spectrum» and that the «opportunists have landed on their feet» on K Street. It may be more difficult for the white nationalist Stephen Miller to land a lucrative lobbying job in Washington, D.C., but at the time of writing, Miller was serving as President of America First Legal, which suggests that he may not have landed too badly. In conclusion, Moran and Iwayemi maintain that «sunlight is the best disinfectant.»[107]

One recent study suggests that we observe a continuation of ongoing revolving door trends or a linear increase under Trump.[108] Another scholar writes: «if there was a ‹swamp› when he entered office, there is no indication that it has been drained at all […], the advocacy community has prospered in the Trump years. And rather than draining the swamp, the inside influence of many interests has swamped the drain within the executive branch.»[109] Supporting Moran and Iwayemi’s pronouncements, another describes the Trump’s administration as a «classic corporatocracy» in which «about 70 % of its senior personnel have corporate ties, and roughly 350 lobbyists or former lobbyists work for the administration.»[110] As many have pointed out, this is problematic. Indeed, Rex Tillerson, who served as CEO of ExxonMobil and had assets exceeding 300 mn dollars before he served as secretary of state under Trump, offered the following reflections after he had left the administration: «[a]s I reflect upon the state of our American democracy […] I observe a growing crisis in ethics and integrity.»[111] It should be noted that while the Trump administration was business friendly and deficient in the realm of ethics and integrity, it did administer a populist shock to the system, a shift from business-as-usual: «no contemporary administration has produced as much uncertainty as Trump’s. Lobbyists and organized interests dislike great uncertainty, even though on occasion it can provide them with real opportunities.»[112]

Conclusions

This paper helps advance our understanding of Trump and the revolving door in several ways. Its key findings are as follows. First, there is a consensus that the revolving door is pervasive and revolving door activity is at a very high level in the United States. Second, revolving door activity has increased in recent decades. Third, businessmen turned presidents are relatively rare, but all of them including Trump are family businessmen. Future research should differentiate between family businessmen and -women and managers of listed companies in revolving door politics.

Given the failure of many businessmen and women to revolve into the presidency in recent years, I argue that structural factors including the level of revolving door activity in the United States are insufficient for explaining Trump’s remarkable 2016 election upset. Fourth, to understand the extraordinary case of how Trump managed to revolve into the White House, I argue that we must consider idiosyncratic factors including Trump’s fame, his skills as a showman, and his status as a celebrity turned reality TV star. In addition, I have stressed the importance of his status as a right-wing populist, who is strongly pro-business, but anti-business establishment in orientation, and who aggressively opposes liberal, cultural, and political elites. Trump was able to do these things because he revolved from business into politics, rather than the usual way, which is revolving from Capitol Hill to K Street. As a candidate, Trump railed against the revolving door and pledged to drain the swamp. Indeed, it is quite possible that Trump’s opposition to the revolving door helped him to get elected as president. This underlines the importance of examining the direction in which the revolving door swings in revolving door politics. Fifth, although Trump did cause considerable disruption, it does not appear that his administration led to a reduction of revolving door activity in Washington, D.C.

Although this paper is focused on the extraordinary if not unique American case of Donald Trump, future research could compare this case to other prominent examples of businessmen revolving into politics at the highest level, such as with Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi in Italy. Existing literature suggests that there are far-reaching similarities between Berlusconi and Trump.[113] There are also some differences: although Berlusconi was Italy’s richest entrepreneur when he revolved into politics and became Prime Minister of Italy, his populist rule was less disruptive than Trump’s. Historians could deepen and extend our understanding of the conditions and circumstances which allow anti-establishment populists to rise to power. Here, it might be helpful to draw on cutting-edge literature which identifies political discontent and elite disarray as critical antecedent conditions for populists’ rise.[114]

Trump may be one of the most remarkable cases of a businessman revolving into politics in recent world history. Trump is also a demagogue[115]—«a demagogue of the spectacle—part entertainer, part authoritarian»[116] who openly attempted to destroy the system of the administrative state while in office. «More than any president in American history, Donald Trump displays leadership by dominance, through distinctively human manifestations of brute force, bluffing, and intimidation.»[117] As the attempted coup, the storming of the US Capitol building on 6 January 2021, has shown, Trump threatens American democracy itself. At the time of writing, the Republican party was unwilling or unable to stand up to and make a decisive break with Trump, and perhaps this should not surprise us, since «[t]he radicalization of the Republican Party had been taking place over decades […].»[118]

While Republicans and business organizations were not pleased with all aspects of Trump, their opposition was muted by Trump’s strongly pro-business orientation: «[t]he interests of business are central and defining» for American conservatism «while every other aspect or strategy of the movement is mutable and disposable.»[119] Trump has been discounted many times in the past. At the time of writing, it cannot be ruled out that Trump will become the Republican nominee before being re-elected as President of the United States in 2024. Even if his political career is now finally at an end and his family business is in decline, the consequences of his presidency will be with us for some time. Further research is needed about Donald Trump and the underlying problems of regulatory capture and establishment corruption,[120] the revolving door will be with us for the foreseeable future, for better or for worse.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Carsten Burhop and Jan-Otmar Hesse and Andrea Schneider-Braunberger for their interest and support of my work. I would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments.

© 2023 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Aufsätze (Articles)

- «Seitenwechsel» – Unternehmer in der Politik und Politiker in der Wirtschaft. Eine Einleitung

- Kaufleute als Konsuln – Zu den Anfängen deutscher Handelsdiplomatie in Ostasien im 19. Jahrhundert

- Januskopf der deutschen Geldwirtschaft: Karl Helfferich (1872 bis 1924)

- Universalitätsansprüche – Verbandsvertreter in der deutsch-französischen Wirtschaftsdiplomatie der 20er und frühen 30er Jahre

- Vom Röhren-Manager zum Verteidigungs-Staatssekretär und zurück: Der mehrfache Seitenwechsel von Ernst Wolf Mommsen

- Seitenwechsler im Zentralbankwesen – Karrieren im Beziehungsdreieck von Finanzwelt, Wissenschaft und Politik (1948 bis 1970)

- Donald Trump, anti-establishment populism and the revolving door between business and politics in the United States

- Rezensionen (Reviews)

- Joachim Scholtyseck, Die National-Bank. Von der Bank der christlichen Gewerkschaften zur Mittelstandsbank, 1921–2021, C.H. Beck, München 2021, 464 S., € 39,95.

- Patrick Bormann/Friederike Sattler, Die DZ HYP. Eine genossenschaftliche Hypothekenbank zwischen Tradition und Wandel (1921–2021), C.H. Beck, München 2021, 523 S., € 44,00.

- Martin Schmitt, Digitalisierung der Kreditwirtschaft. Computereinsatz in den Sparkassen der Bundesrepublik und der DDR 1957 bis 1991, Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2021, 656 S., € 58,00.

- Sebastian Justke, Ein ehrbarer Kaufmann? Albert Schäfer, sein Unternehmen und die Stadt Hamburg 1933–1956, Metropol, Berlin 2022, 264 S., € 24,00.

- Angela Bhend, Triumph der Moderne. Jüdische Gründer von Warenhäusern in der Schweiz, 1890–1945, Chronos Verlag, Zürich 2021, 351 S., € 58,00.

- Philipp Julius Meyer, Kartographie und Weltanschauung. Visuelle Wissensproduktion im Verlag Justus Perthes 1890–1945, Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2021, 480 S., € 56,00.

- Michael A. Kanther, Thyssengas. Die Geschichte des ersten deutschen Unternehmens der Ferngasversorgung von 1892 bis 2020, Aschendorff Verlag, Münster 2021, 434 S., € 29,80.

- Zur Rezension in der Geschäftsstelle eingegangene Bücher

- Mitteilung (information)

- Preis für Unternehmensgeschichte Ausschreibung 2024

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Aufsätze (Articles)

- «Seitenwechsel» – Unternehmer in der Politik und Politiker in der Wirtschaft. Eine Einleitung

- Kaufleute als Konsuln – Zu den Anfängen deutscher Handelsdiplomatie in Ostasien im 19. Jahrhundert

- Januskopf der deutschen Geldwirtschaft: Karl Helfferich (1872 bis 1924)

- Universalitätsansprüche – Verbandsvertreter in der deutsch-französischen Wirtschaftsdiplomatie der 20er und frühen 30er Jahre

- Vom Röhren-Manager zum Verteidigungs-Staatssekretär und zurück: Der mehrfache Seitenwechsel von Ernst Wolf Mommsen

- Seitenwechsler im Zentralbankwesen – Karrieren im Beziehungsdreieck von Finanzwelt, Wissenschaft und Politik (1948 bis 1970)

- Donald Trump, anti-establishment populism and the revolving door between business and politics in the United States

- Rezensionen (Reviews)

- Joachim Scholtyseck, Die National-Bank. Von der Bank der christlichen Gewerkschaften zur Mittelstandsbank, 1921–2021, C.H. Beck, München 2021, 464 S., € 39,95.

- Patrick Bormann/Friederike Sattler, Die DZ HYP. Eine genossenschaftliche Hypothekenbank zwischen Tradition und Wandel (1921–2021), C.H. Beck, München 2021, 523 S., € 44,00.

- Martin Schmitt, Digitalisierung der Kreditwirtschaft. Computereinsatz in den Sparkassen der Bundesrepublik und der DDR 1957 bis 1991, Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2021, 656 S., € 58,00.

- Sebastian Justke, Ein ehrbarer Kaufmann? Albert Schäfer, sein Unternehmen und die Stadt Hamburg 1933–1956, Metropol, Berlin 2022, 264 S., € 24,00.

- Angela Bhend, Triumph der Moderne. Jüdische Gründer von Warenhäusern in der Schweiz, 1890–1945, Chronos Verlag, Zürich 2021, 351 S., € 58,00.

- Philipp Julius Meyer, Kartographie und Weltanschauung. Visuelle Wissensproduktion im Verlag Justus Perthes 1890–1945, Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2021, 480 S., € 56,00.

- Michael A. Kanther, Thyssengas. Die Geschichte des ersten deutschen Unternehmens der Ferngasversorgung von 1892 bis 2020, Aschendorff Verlag, Münster 2021, 434 S., € 29,80.

- Zur Rezension in der Geschäftsstelle eingegangene Bücher

- Mitteilung (information)

- Preis für Unternehmensgeschichte Ausschreibung 2024